Abstract

Objective:

Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) is caused by haploinsufficiency of SHANK3 on terminal chromosome 22. Knowledge about altered neuroanatomical circuitry in PMS comes from mouse models showing striatal hypertrophy in the basal ganglia, and from humans with evidence of cerebellar atrophy. To date, no studies have performed volumetric analysis on PMS patients.

Methods:

We performed volumetric analysis on baseline brain MRIs of PMS patients (ages 3–21 years) enrolled in a prospective natural history study (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02461420). Using MRI segmentations carried out with PSTAPLE algorithm, we measured relative volumes (volume of the structure divided by the volume of the brain parenchyma) of basal ganglia and cerebellar structures. We compared these measurements to those of age- and sex-matched healthy controls part of another study. Among the patients, we performed linear regression of each relative volume using Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) total score and Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) stereotypy score. Eleven patients with PMS (6 females, 5 males) and 11 healthy controls were in this analysis.

Results:

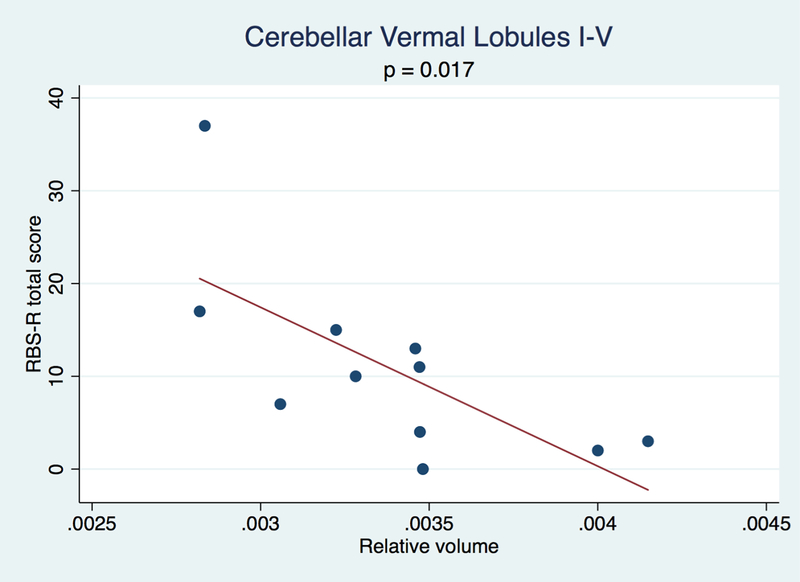

At time of MRI, the mean age of the patients and controls was 9.24 (5.29) years and 9.00 (4.49) years, respectively (p=0.66). Compared to controls, patients had decreased caudate (p≤0.013), putamen (p≤0.026), and left pallidum (p=0.033) relative volumes. Relative volume of cerebellar vermal lobules I-V (beta coefficient=−17119, p=0.017) decreased with increasing RBS-R total score.

Conclusions:

The volumes of the striatum and left pallidum are decreased in individuals with PMS. Cerebellar vermis volume may predict repetitive behavior severity in PMS. These findings warrant further investigation in larger samples.

Keywords: 22q13.3 deletion, SHANK3, repetitive behaviors, MRI, autism

Introduction

Phelan-McDermid syndrome (PMS) is a disorder of synaptic transmission caused by loss of function of SHANK3 protein, occurring through deletion of terminal chromosome 22 encompassing the SHANK3 gene, or through intragenic mutations [Phelan et al., 2001; Bonaglia et al., 2001; Soorya et al., 2013]. SHANK3 is a postsynaptic density scaffolding protein that plays several important roles in the central nervous system (CNS), including dendritic spine maturation and synapse formation [Monteiro and Feng, 2017]. Affected patients present variably with somatic and neurobehavioral features, including minor facial and systemic anomalies, normal to advanced growth, global developmental delay/intellectual disability, absent or delayed speech, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and generalized hypotonia [Phelan et al., 2001; Soorya et al., 2013; Oberman et al., 2015].

Animal models of PMS have recapitulated some of these clinical features and revealed neuropathological and circuitry changes in the basal ganglia. Mice with Shank3 deletions have striatal (caudate/putamen) hypertrophy and abnormally shaped striatal neurons. In addition, their striatal postsynaptic densities show reduced expression of scaffolding proteins and glutamate receptor subunits [Peça et al., 2011; Jaramillo et al., 2017, 2016]. There is also evidence of abnormalities in the basal ganglia circuitry in Shank3-deficient mice [Jaramillo et al., 2017, 2016]. Shank3-deficient mice have defects in the synaptic properties of striatopallidal medium spiny neurons (MSNs) [Wang et al., 2017; Jaramillo et al., 2016]. Input to the striatum of the basal ganglia comes from the cortex and thalamus, while output from the striatum takes the form of either the direct projection pathway, comprising striatonigral neurons, or the indirect pathway, comprising striatopallidal neurons. A balance in the activity of the two pathways facilitates motor behaviors. In Wang et al., administration of an agent designed to upregulate striatopallidal MSN activity ameliorated repetitive grooming, suggesting that preferential involvement of the indirect striatal pathway may be implicated in the development of repetitive behaviors in Shank3-deficient mice [Wang et al., 2017].

Neuroimaging studies and case reports/case series of individuals with PMS have highlighted abnormalities in CNS structures other than the basal ganglia. In affected patients, radiographic findings have included corpus callosum thinning, ventriculomegaly, and cerebellar vermis hypoplasia [Aldinger et al., 2013; Bonaglia et al., 2011; Philippe et al., 2008; Doheny et al., 1997; Lindquist et al., 2005]. To date, no studies have performed volumetric analysis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data in humans with PMS, in order to evaluate the basal ganglia or cerebellum for evidence of pathology.

In this study, we performed volumetric analysis in 11 subjects, ages 3–21 years, with PMS as well as 11 age- and sex-matched controls. We focused on the basal ganglia and cerebellum. We hypothesized that, compared to controls, patients with PMS have larger striatal volumes, concordant with animal model data. We also hypothesized that decreased cerebellar volumes is predictive of more severe repetitive behaviors, given that cerebellar vermal hypoplasia is a common finding in PMS and that defects in cerebellar circuitry are associated with ASD symptoms [Rogers et al., 2013].

Methods

Study Participants

We performed volumetric analysis on baseline brain MRIs of patients (ages 3–21 years) with PMS enrolled in a multi-site, prospective, observational cohort study evaluating the genotype, phenotype, and natural history of PMS (ClinicalTrial NCT02461420). English speaking males or females, ages 3–21 years, with pathogenic deletions or mutations affecting the SHANK3 gene were eligible for inclusion in the natural history study; brain MRIs were part of the evaluation if clinically indicated. Clinical indications for MRI included (but were not limited to): a. No previous MRI (given that current practice recommendations for PMS suggest a baseline brain MRI to assess for cysts and other structural abnormalities) [Kolevzon et al., 2014]; b. Change in developmental progress (e.g., regression); c. New neurological sign (e.g., motor finding, asymmetry); d. New onset of seizures or worsening of previous seizure pattern.

Behavioral Assessments

Individuals received a diagnosis of ASD based on clinical consensus using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5) [American Psychiatric Association et al., 2013], and informed by evaluation with the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule [Lord et al., 2012] and Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised [Rutter et al., 2003].

In addition, individuals underwent evaluation with a battery of assessments, including the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) [Lam and Aman, 2007], Vineland Adaptive Behaviors Scales II (VABS-II) [Sparrow et al., 2005], and Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) [Aman et al., 1986]. The RBS-R is a questionnaire containing 43 items pertaining to restricted and repetitive behaviors across six categories: stereotyped behavior, self-injurious behavior, compulsive behavior, ritualistic behavior, sameness behavior, and restricted behavior. Each item is coded with an integer score from 0–3 corresponding to the severity of the behavior. Each of the six subscales has two corresponding scores: one for the sum of all the scores within the subscale, and one for the total number of subscale items endorsed. For the entire instrument, there are overall scores for the sum of all the item scores (overall total score) and the total number of items endorsed.

The VABS-II assesses adaptive behavior with respect to communication, socialization, daily living skills, and motor skills [Sparrow et al., 2005]. Each domain has an associated standard score, and domain scores generate an overall adaptive behavior composite standard score.

The ABC is a 58-item caregiver checklist evaluating problem behaviors in the following five domains: (a) irritability (mood lability, self-injury, aggression); (b) lethargy/social withdrawal (isolation from others, little interaction); (c) stereotypies; (d) hyperactivity; and (e) abnormal speech (odd use of speech). Each item is scored from 0–3 corresponding to the severity of the behavior. For this analysis, we included the ABC stereotypy domain.

MRI Processing

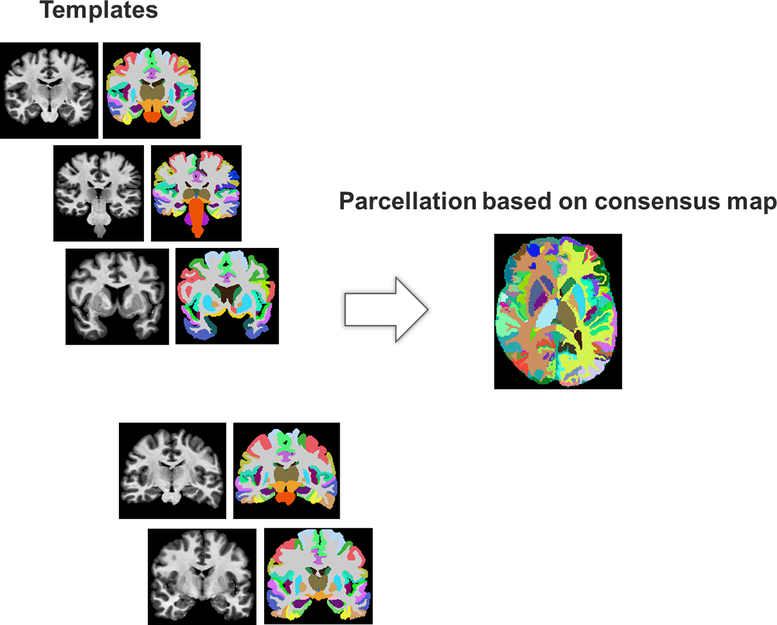

We performed MRI processing and analysis with the Computational Radiology Kit (http://crl.med.harvard.edu/). This toolkit aligns the T2w image to the T1w image using rigid registration with mutual information metric; creates an intracranial cavity (ICC) segmentation using a previously validated multispectral ICC segmentation method [Grau et al., 2004]; and parcellates each MRI into regions of interest (ROIs) using a previously validated multi-template fusion segmentation algorithm [Akhondi-Asl and Warfield, 2013]. The template library consisted of 15 T1w, T2w, and FLAIR healthy control MRIs [nine male; mean age 9.1 (3.3) years; age range 5–15 years], which were hand labeled by expert neuroanatomists using well-established MRI brain labeling protocols [Strudwick Caviness et al., 1999; Klein and Tourville, 2012] to create anatomical boundary definitions, with test-retest reproducibility quantified. Each T1w template was non-rigidly aligned to the patient T1w image and multi-template fusion was carried out using the local MAP PSTAPLE (PSTAPLE) algorithm [Akhondi-Asl and Warfield, 2013]. PSTAPLE uses both the label images and intensity profiles of the T1w templates to compute probability maps for each target structure, ultimately leading to an automatic consensus labeling of each patient brain. See Figure 1. The automatic parcellations were carefully reviewed to ensure accuracy with respect to basal ganglia and thalamus ROIs, performing editing as needed.

Figure 1.

Illustration of multi-template parcellation. All the templates are first non-linearly aligned to a target patient. A consensus map is then computed for each patient, providing a fully-automatic, robust to inter-individual variability parcellation of each patient’s brain.

Using these segmentations of the MRI, we computed left and right relative volumes pertaining to four anatomical structures: left/right caudate, left/right putamen, left/right globus pallidus, left/right thalamus, left/right cerebellar white matter, left/right cerebellar exterior, cerebellar vermal lobules I-V, cerebellar vermal lobules VI-VII, and cerebellar vermal lobules VIII-X. In this study, we did not analyze other brain regions. Each relative volume was computed as the volume of the structure divided by the volume of the brain parenchyma (intracranial cavity subtracted by ventricular volume and extracerebral CSF volume) given reports of ventriculomegaly in PMS. We compared relative volumes to those of age- and sex-matched healthy controls.

Statistical Analysis

We used Pearson’s chi-squared test to compare gender between subject categories. We used Wilcoxon signed-rank test to compare age and relative volumes between patients and controls. We used Wilcoxon rank-sum test to compare relative volumes between patients with ASD versus patients without ASD. We employed Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) procedure to control for multiple comparisons, setting acceptable value of FDR to 0.20 for our current sample size.

Results

Eleven patients with PMS (6 females, 5 males) and 11 healthy, age- and sex-matched controls were analyzed. At the time of brain MRI, the mean age of the patients and controls was 9.24 years [range 3.43–20.87 years] and 9.00 years [range 3.11–16.70 years], respectively (p = 0.66). Among the 11 patients, enlarged ventricles were present in 3, a thin corpus callosum was present in 2, and arachnoid cysts were present in 2. In terms of genotype, 11/11 (100%) had a pathogenic 22q13 deletion, ranging in size from 78kb to 8230kb, that included SHANK3. One participant also had a 206.3kb de novo pathogenic 16p11 deletion in addition to 22q13 deletion. 6/11 (54.55%) had a diagnosis of ASD. For the patients, the mean VABS-II adaptive behavior composite was 54.72, the mean RBS-R overall score was 10.82, and the mean ABC stereotypy score was 2.91 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of the patients and controls. N/A = not applicable.

| Patients (n = 11) | Controls (n = 11) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% male) | 45.45% (n = 5) | 45.45% (n = 5) | p = 1.00 |

| Age at brain MRI [years (SD)] | 9.24 (5.29) | 9.00 (4.49) | p = 0.66 |

| Autism diagnosis (%) | 54.54% (n = 6) | N/A | N/A |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-II (VABS-II) adaptive behavior composite standard score [score (SD)] | 54.72(18.97) | N/A | N/A |

| Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) overall score [score (SD)] | 10.82 (10.31) | N/A | N/A |

| Aberrant Behavior Checklist (ABC) stereotypy score [score (SD)] | 2.91 (4.83) | N/A | N/A |

There was no difference in ICC volume (p = 0.33) or total volume of the brain parenchyma (p = 0.66) between patients and controls. Relative volumes of the right caudate (p = 0.0076), left caudate (p = 0.013), right putamen (p = 0.026), left putamen (p = 0.016), and left pallidum (p = 0.033) were decreased in patients versus controls, and these were statistically significant after accounting for multiple comparisons. There was no statistically significant difference in relative volume of any of the cerebellar structures between patients and controls (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative volumes of basal ganglia and cerebellar structures for the patients and controls.

| Patients (n = 11) | Controls (n = 11) | p-value | Significant after false discovery rate procedure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Pallidum [mean (SD)] | .00113 (.00014) | .00119 (.00017) | 0.15 | No |

| Left Pallidum [mean (SD)] | .00112 (.000097) | .00122 (.00017) | 0.033 | Yes |

| Right Putamen [mean (SD)] | .00412 (.00062) | .00468 (.00044) | 0.026 | Yes |

| Left Putamen [mean (SD)] | .00410 (.00063) | .00472 (.00045) | 0.016 | Yes |

| Right Caudate [mean (SD)] | .00307 (.00022) | .00358 (.00041) | 0.0076 | Yes |

| Left Caudate [mean (SD)] | .00309 (.00023) | .00345 (.00038) | 0.013 | Yes |

| Right Cerebellum White Matter [mean (SD)] | .0106 (.0015) | .0106 (.0020) | 0.86 | No |

| Left Cerebellum White Matter [mean (SD)] | .0109(.0015) | .0108(.0019) | 0.79 | No |

| Cerebellar Vermal Lobules I-V | .00339 | .00365 | 0.13 | No |

| [mean (SD)] | (.00042) | (.00045) | ||

| Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VI-VII [mean (SD)] | .00128(.00023) | .00144 (.00025) | 0.21 | No |

| Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VIII-X [mean (SD)] | .00203 (.00032) | .00212 (.00021) | 0.53 | No |

| Right Cerebellum Exterior [mean (SD)] | .0392 (.0044) | .0401 (.0031) | 0.66 | No |

| Left Cerebellum Exterior [mean (SD)] | .0392 (.0043) | .0398 (.0029) | 0.66 | No |

When comparing relative volumes of each of the structures in patients with ASD (PMS+ASD) versus patients without ASD (PMS-ASD), no structures showed a statistically significant difference between groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Relative volumes of basal ganglia and cerebellar structures for the patients stratified by diagnosis of autism.

| Patients + ASD (n = 6) | Patients no ASD (n = 5) | p-value | Significant after false discovery rate procedure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right Pallidum [mean (SD)] | .00113 (.00013) | .00112 (.00017) | .855 | No |

| Left Pallidum [mean (SD)] | .00115 (.00011) | .00109 (.000070) | .273 | No |

| Right Putamen [mean (SD)] | .00403 (.00084) | .00422 (.00026) | 1.00 | No |

| Left Putamen [mean (SD)] | .00395 (.00084) | .00428 (.00023) | .715 | No |

| Right Caudate [mean (SD)] | .00305 (.00030) | .00309 (.00011) | 1.00 | No |

| Left Caudate [mean (SD)] | .00316 (.00025) | .00300 (.00019) | .361 | No |

| Right Cerebellum White Matter [mean (SD)] | .0108(.0016) | .0104 (.0014) | .715 | No |

| Left Cerebellum White Matter [mean (SD)] | .0112 (.0016) | .01050 (.0015) | .465 | No |

| Cerebellar Vermal Lobules I-V [mean (SD)] | .00334 (.00040) | .00344 (.00048) | .715 | No |

| Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VIVII [mean (SD)] | .00122 (.00030) | .00134 (.00010) | .361 | No |

| Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VIII-X [mean (SD)] | .00190 (.00033) | .00219 (.00027) | .144 | No |

| Right Cerebellum Exterior [mean (SD)] | .0391 (.0055) | .0392 (.0032) | .584 | No |

| Left Cerebellum Exterior [mean (SD)] | .0388 (.0052) | .0396 (.0035) | .584 | No |

For the patients, linear regressions of each relative volume with RBS-R overall total score showed that with increasing RBS-R total score, there was decreased relative volume of the cerebellar vermal lobules I-V (beta coefficient = −17119, p = 0.017), though separate regressions for individuals with and without ASD were not statistically significant. See Figure 2. The regressions of relative volumes of striatal structures with RBS-R overall total scores were not statistically significant. There was not a statistically significant regression between RBS-R total score and 22q13 deletion size. There was no statistically significant regression between ABC stereotypy score and relative volume of any of the structures.

Figure 2.

Scatter plots and fitted lines of RBS-R total score versus relative volumes of cerebellar vermal lobules I-V showing an inverse relationship between the relative volume and RBS-R total score.

The statistical significance of these aforementioned findings (including Table 2, Table 3, and linear regressions of each relative volume with RBS-R overall total score) remained true even when the participant with dual diagnoses was excluded from analysis.

Discussion

The main finding in this report is that the volumes of the striatum and left pallidum were decreased in our cohort of 11 patients with PMS compared to healthy controls. However, the volumes of the cerebellar structures were not significantly different in patients versus controls. Finally, cerebellar vermal lobules I-V relative volume increased with decreasing RBS-R total score.

Our study is first to examine volumetric differences in the basal ganglia and cerebellum in human subjects with PMS. Prior reports have implicated a variety of gross structural abnormalities in this syndrome. In one study examining brain MRIs of 10 patients with 22q13 deletions, the following radiographic features were present: thin corpus callosum (90%), thin white matter (70%), ventriculomegaly (80%), definite or subtle cerebellar vermis hypoplasia (60%), and definite or subtle mega cisterna magna (50%, including two patients who also had definite cerebellar vermis hypoplasia) [Aldinger et al., 2013]. Similarly, in a separate cohort of eight patients with 22q13 deletions who underwent brain imaging with MRI and positron emission tomography (PET) scans, the two most common imaging abnormalities were a thin/morphologically atypical corpus callosum and ventricular dilatation. Collectively, these patients also demonstrated hypoperfusion in the left temporal-polar lobe and amygdala [Philippe et al., 2008]. Multiple other reports have corroborated the presence of features such as corpus callosum thinning [Doheny et al., 1997; Lindquist et al., 2005], delayed myelination [Doheny et al., 1997] or other white matter abnormalities [Bonaglia et al., 2011], and ventricular enlargement [Bonaglia et al., 2011] in PMS.

Our findings suggest dysfunction in basal ganglia circuitry as one of the possible mechanisms underlying disease in PMS. In support of this notion, expression of Shank3 is particularly high in the striatum and thalamus compared to other regions in the central nervous system (CNS) [Böckers et al., 2004; Peça et al., 2011]. Moreover, Shank3 deficient mice exhibit obsessive, self-injurious grooming in conjunction with evidence of impaired neurotransmission at striatal and cortico-striatal synapses [Peça et al., 2011; Jaramillo et al., 2017, 2016]. The basal ganglia have a number of important functions in the brain, including sensory control, motor programming, and reward-driven behaviors. Striatal dysfunction is an example of the final common pathways that may lead to the emergence of autism symptoms, in particular repetitive behaviors [Fuccillo, 2016] – features which are prominent in PMS [Soorya et al., 2013; Oberman et al., 2015]. Interestingly, RBS scores did not correlate with striatal volumes in the patient group, perhaps reflecting that this cohort had relatively mild repetitive behaviors (mean RBS overall total score 10.82), and/or that this cohort had relatively small numbers.

Surprisingly, among our patients, the finding of comparatively decreased caudate and putamen size was contrary to our hypothesis regarding striatal volume. We had speculated that striatal volume would be greater in patients, based on the fact that Shank3B−/− mice have evidence of caudate hypertrophy [Peça et al., 2011]. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the PMS mouse model may not completely recapitulate the phenotype seen in humans. This notion of face validity [Katz et al., 2012] poses a challenge for animal models across multiple genetic disorders. Of note, in light of this conflict with animal model data, our findings may not be generalizable as of yet and warrant confirmation with a larger number of patients. The lack of a correlation between basal ganglia volume and stereotypy score in our cohort also seems surprising, though this may be consistent with the mixed nature of data about whether increased or decreased basal ganglia volumes are associated with repetitive behavior severity [Wilkes and Lewis, 2018]. For example, in one study, in young children with ASD, decreased basal ganglia and thalamus volumes were associated with increased levels of repetitive and stereotyped behavior [Estes et al., 2011]. However, in another study, increased right caudate and total putamen volume was associated with greater repetitive behaviors [Hollander et al., 2005]. In Fragile X syndrome, a monogenic disorder associated with a high prevalence of ASD, researchers have shown that left and right caudate volumes are positively correlated with severity of self-injurious behaviors and number of self-injurious behavior topographies [Wolff et al., 2013].

Underdevelopment of the cerebellar vermis is a known finding in humans with PMS [Aldinger et al., 2013], but in our cohort relative volumes of cerebellar structures were not significantly different compared to controls. The factors that influence development of cerebellar vermis hypoplasia in PMS are unclear. For example, in the aforementioned study, there was not a clear-cut relationship between 22q13 deletion size and degree of cerebellar vermis hypoplasia, suggesting that there could be genetic modifiers influencing this phenotype. It could also be that our sample may be disproportionately skewed in terms of patients not being affected by cerebellar hypoplasia. Given that MRI studies on PMS, including this one, have involved small numbers of participants, a large scale study may be necessary to fully understand the prevalence of cerebellar hypoplasia within the disorder.

Though relative volumes of cerebellar structures were not significantly different compared to controls, patients with larger relative volume of cerebellar vermal lobules I-V had lower (i.e., less impaired) RBS-R total scores. Cerebellar vermis malformations have been implicated in ASD symptoms [Tavano et al., 2007]. Therefore, one possible mechanism for our findings is that reduced cerebellar vermal volumes, perhaps reflecting degree of Purkinje cell loss, could mediate some aspects of the behavioral phenotype of PMS.

The major caveat to our study is that the overall sample size of our study was small with only n = 11 subjects. This small number may explain why there was not a statistically significant difference in relative volumes of any of the studied structures between PMS+ASD and PMS-ASD. Moreover, due to the varying cognitive abilities within this group, we were not able to obtain a full scale IQ score for all participants; nonetheless we included VABS data, and adaptive functioning as a proxy for overall cognitive ability. Given the relative paucity of detailed MRI studies on this patient population, our results are noteworthy and point to further avenues of investigation. Specifically, it will be important to demonstrate replicability of our findings with larger numbers of patients. Nonetheless, this study highlights the basal ganglia and cerebellum as intriguing targets for further investigation in PMS.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the Developmental Synaptopathies Consortium (U54NS092090), which is a part of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network. The Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network is an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and Developmental Synaptopathies Consortium is funded through collaboration between the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

We are sincerely indebted to the generosity of the families and patients in PMS clinics across the United States who contributed their time and effort to this study. We would also like to thank the Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Foundation for their continued support in PMS research.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Members of the Developmental Synaptopathies Consortium (DSC) – Phelan-McDermid Syndrome Group include:

Mustafa Sahin, MD, PhD a, b

Alexander Kolevzon, MD c, d

Joseph Buxbaum, PhD c, d, e, f

Elizabeth Berry Kravis, MD, PhD g, h, i

Latha Soorya, PhD j

Audrey Thurm, PhD k

Craig Powell, MD, PhD l, m

Jonathan A Bernstein, MD, PhD n

Simon Warfield, PhD o

Benoit Scherrer, PhD o

Rajna Filip-Dhima, MS a

Kira Dies, ScM, CGC a

Paige Siper, PhD c

Ellen Hanson, PhD p

Jennifer M. Phillips, PhD q

Stormi P. White, Psy D r

Affiliations for above:

a Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

b F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

c Seaver Autism Center for Research and Treatment, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY

d Department of Psychiatry, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY

e Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY

f Department of Neuroscience, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, NY

g Department of Pediatrics, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

h Department of Neurological Sciences, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

i Department of Biochemistry, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

j Department of Psychiatry, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL

k Pediatrics and Developmental Neuroscience Branch, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

l Department of Neurology and Neurotherapeutics, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center,Dallas, TX

m Department of Psychiatry and Neuroscience Graduate Program, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX

n Department of Pediatrics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA o Department of Radiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA p Department of Developmental Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

q Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA

r Center for Autism and Developmental Disabilities,, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX

REFERENCES

- Akhondi-Asl A, Warfield SK. 2013. Simultaneous truth and performance level estimation through fusion of probabilistic segmentations. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 32: 1840–1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldinger KA, Kogan J, Kimonis V, Fernandez B, Horn D, Klopocki E, Chung B, Toutain A, Weksberg R, Millen KJ, Barkovich AJ, Dobyns WB. 2013. Cerebellar and posterior fossa malformations in patients with autism-associated chromosome 22q13 terminal deletion. Am J Med Genet A 0: 131–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aman M, Singh N, Stewart A, Field C. 1986. The Aberrant Behavior Checklist: Manual. East Aurora, NY: Slosson Educational Publications. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5 Task Force. 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Arlington, Va.: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Böckers TM, Segger-Junius M, Iglauer P, Bockmann J, Gundelfinger ED, Kreutz MR, Richter D, Kindler S, Kreienkamp H-J. 2004. Differential expression and dendritic transcript localization of Shank family members: identification of a dendritic targeting element in the 3′ untranslated region of Shank1 mRNA. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 26: 182–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Beri S, De Agostini C, Novara F, Fichera M, Grillo L, Galesi O, Vetro A, Ciccone R, Bonati MT, Giglio S, Guerrini R, Osimani S, Marelli S, Zucca C, Grasso R, Borgatti R, Mani E, Motta C, Molteni M, Romano C, Greco D, Reitano S, Baroncini A, Lapi E, Cecconi A, Arrigo G, Patricelli MG, Pantaleoni C, D’Arrigo S, Riva D, Sciacca F, Dalla Bernardina B, Zoccante L, Darra F, Termine C, Maserati E, Bigoni S, Priolo E, Bottani A, Gimelli S, Bena F, Brusco A, di Gregorio E, Bagnasco I, Giussani U, Nitsch L, Politi P, Martinez-Frias ML, Martínez-Fernández ML, Martínez Guardia N, Bremer A, Anderlid B-M, Zuffardi O. 2011. Molecular Mechanisms Generating and Stabilizing Terminal 22q13 Deletions in 44 Subjects with Phelan/McDermid Syndrome. PLoS Genet 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Borgatti R, Felisari G, Gagliardi C, Selicorni A, Zuffardi O. 2001. Disruption of the ProSAP2 gene in a t(12;22)(q24.1;q13.3) is associated with the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69: 261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doheny KF, McDermid HE, Harum K, Thomas GH, Raymond GV. 1997. Cryptic terminal rearrangement of chromosome 22q13.32 detected by FISH in two unrelated patients. J. Med. Genet 34: 640–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes A, Shaw DWW, Sparks BF, Friedman S, Giedd JN, Dawson G, Bryan M, Dager SR. 2011. Basal ganglia morphometry and repetitive behavior in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res 4: 212–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuccillo MV. 2016. Striatal Circuits as a Common Node for Autism Pathophysiology. Front. Neurosci 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grau V, Mewes AUJ, Alcañiz M, Kikinis R, Warfield SK. 2004. Improved watershed transform for medical image segmentation using prior information. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 23: 447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Anagnostou E, Chaplin W, Esposito K, Haznedar MM, Licalzi E, Wasserman S, Soorya L, Buchsbaum M. 2005. Striatal volume on magnetic resonance imaging and repetitive behaviors in autism. Biol. Psychiatry 58: 226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo TC, Speed HE, Xuan Z, Reimers JM, Escamilla CO, Weaver TP, Liu S, Filonova I, Powell CM. 2017. Novel Shank3 mutant exhibits behaviors with face validity for autism and altered striatal and hippocampal function. Autism Res 10: 42–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo TC, Speed HE, Xuan Z, Reimers JM, Liu S, Powell CM. 2016. Altered Striatal Synaptic Function and Abnormal Behaviour in Shank3 Exon4–9 Deletion Mouse Model of Autism. Autism Res 9: 350–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DM, Berger-Sweeney JE, Eubanks JH, Justice MJ, Neul JL, Pozzo-Miller L, Blue ME, Christian D, Crawley JN, Giustetto M, Guy J, Howell CJ, Kron M, Nelson SB, Samaco RC, Schaevitz LR, Hillaire-Clarke CS, Young JL, Zoghbi HY, Mamounas LA. 2012. Preclinical research in Rett syndrome: setting the foundation for translational success. Disease Models & Mechanisms 5: 733–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, Tourville J. 2012. 101 Labeled Brain Images and a Consistent Human Cortical Labeling Protocol. Front. Neurosci 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolevzon A, Angarita B, Bush L, Wang AT, Frank Y, Yang A, Rapaport R, Saland J, Srivastava S, Farrell C, Edelmann LJ, Buxbaum JD. 2014. Phelan-McDermid syndrome: a review of the literature and practice parameters for medical assessment and monitoring. J Neurodev Disord 6: 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam KSL, Aman MG. 2007. The Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised: independent validation in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 37: 855–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist SG, Kirchhoff M, Lundsteen C, Pedersen W, Erichsen G, Kristensen K, Lillquist K, Smedegaard HH, Skov L, Tommerup N, Brøndum-Nielsen K. 2005. Further delineation of the 22q13 deletion syndrome. Clin. Dysmorphol 14: 55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore P, Risi S, Gotham K, Bishop S. 2012. Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule2nd edition (ADOS-2). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro P, Feng G. 2017. SHANK proteins: roles at the synapse and in autism spectrum disorder. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 18: 147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberman LM, Boccuto L, Cascio L, Sarasua S, Kaufmann WE. 2015. Autism spectrum disorder in PhelanMcDermid syndrome: initial characterization and genotype-phenotype correlations. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 10: 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peça J, Feliciano C, Ting JT, Wang W, Wells MF, Venkatraman TN, Lascola CD, Fu Z, Feng G. 2011. Shank3 mutant mice display autistic-like behaviours and striatal dysfunction. Nature 472: 437–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan MC, Rogers RC, Saul RA, Stapleton GA, Sweet K, McDermid H, Shaw SR, Claytor J, Willis J, Kelly DP. 2001. 22q13 deletion syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet 101: 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippe A, Boddaert N, Vaivre-Douret L, Robel L, Danon-Boileau L, Malan V, de Blois M-C, Heron D, Colleaux L, Golse B, Zilbovicius M, Munnich A. 2008. Neurobehavioral profile and brain imaging study of the 22q13.3 deletion syndrome in childhood. Pediatrics 122: e376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers TD, McKimm E, Dickson PE, Goldowitz D, Blaha CD, Mittleman G. 2013. Is autism a disease of the cerebellum? An integration of clinical and pre-clinical research. Front. Syst. Neurosci 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, LeCouteur A, Lord C. 2003. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Soorya L, Kolevzon A, Zweifach J, Lim T, Dobry Y, Schwartz L, Frank Y, Wang AT, Cai G, Parkhomenko E, Halpern D, Grodberg D, Angarita B, Willner JP, Yang A, Canitano R, Chaplin W, Betancur C, Buxbaum JD. 2013. Prospective investigation of autism and genotype-phenotype correlations in 22q13 deletion syndrome and SHANK3 deficiency. Mol Autism 4: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow S, Cicchetti V, Balla A. 2005. Vineland adaptive behavior scales 2nd edition. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Strudwick Caviness V, Theodore Lange N, Makris N, Reed Herbert M, Nelson Kennedy D. 1999. MRIbased brain volumetrics: emergence of a developmental brain science. Brain and Development 21: 289–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavano A, Grasso R, Gagliardi C, Triulzi F, Bresolin N, Fabbro F, Borgatti R. 2007. Disorders of cognitive and affective development in cerebellar malformations. Brain 130: 2646–2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Li C, Chen Q, van der Goes M-S, Hawrot J, Yao AY, Gao X, Lu C, Zang Y, Zhang Q, Lyman K, Wang D, Guo B, Wu S, Gerfen CR, Fu Z, Feng G. 2017. Striatopallidal dysfunction underlies repetitive behavior in Shank3-deficient model of autism J. Clin. Invest. 127: 1978–1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkes BJ, Lewis MH. 2018. The neural circuitry of restricted repetitive behavior: Magnetic resonance imaging in neurodevelopmental disorders and animal models. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 92: 152–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JJ, Hazlett HC, Lightbody AA, Reiss AL, Piven J. 2013. Repetitive and self-injurious behaviors: associations with caudate volume in autism and fragile X syndrome. J Neurodev Disord 5: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]