Abstract

Context:

Emerging data warrant the integration of biomedical and behavioral recommendations for HIV prevention in clinical care settings.

Objective(s):

To provide current recommendations for the prevention of HIV infection in adults and adolescents for integration in clinical care settings.

Data Sources and Study Selection:

Data published or presented as abstracts at scientific conferences (past 17 years) were systematically searched and reviewed by the International Antiviral Society–USA HIV Prevention Recommendations Panel. Panel members supplied additional relevant publications, reviewed available data, and formed recommendations by full-panel consensus.

Results:

HIV testing is recommended at least once for all adults and adolescents, with repeated testing for those at increased risk of acquiring HIV. Clinicians should be alert to the possibility of acute HIV infection and promptly pursue diagnostic testing if suspected. Upon diagnosis of HIV, all individuals should be linked to care for timely initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART). Support for adherence and retention in care, individualized risk assessment and counseling, assistance with partner notification, and periodic screening for common sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is recommended for HIV-infected individuals as part of care. In HIV-uninfected patients, those persons at high risk of HIV infection should be prioritized for delivery of interventions such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and individualized counseling on risk reduction. Daily emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF) is recommended as PrEP for persons at high risk for HIV based on background incidence or recent diagnosis of incident STIs, use of injection drugs or shared needles, or recent use of non-occupational postexposure prophylaxis; ongoing use of PrEP should be guided by regular risk assessment. For persons who inject drugs, harm reduction services should be provided (needle and syringe exchange programs, supervised injection, and available medically-assisted therapies, including opioid agonists and antagonists). Low-threshold detoxification and drug cessation programs should be made available. PEP is recommended for all persons who have sustained a mucosal or parenteral exposure to HIV from a known infected source and should be initiated as soon as possible.

Conclusion:

New data support the integration of biomedical and behavioral approaches to prevention of HIV infection in clinical care settings. A concerted effort to implement combination strategies for HIV prevention is urgently needed to realize the goal of an AIDS-free generation.

INTRODUCTION

The availability of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) has changed the lives of millions of individuals living with HIV, transforming HIV from a fatal infection to a manageable chronic disease. Incidence of new HIV-1 infections worldwide has decreased by an estimated 33% since 2001, but remains high at approximately 2.3 million new infections in 2012. In the United States, approximately 50,000 new infections occur each year—a number that has remained largely unchanged since the 1990s.1

The integration of biomedical and behavioral approaches to HIV prevention, coupled with ART for those infected, represents the cornerstone of efforts to curb the spread of HIV infection.2 In an effort to provide practicing clinicians, public health experts, and policy makers with a framework to implement the best HIV prevention interventions, the International Antiviral Society–USA (IAS–USA) Panel has developed recommendations that integrate biomedical and behavioral prevention in the care of people living with or at risk for HIV infection. These recommendations are intended as best practice based on available evidence. Implementing these recommendations may present structural, economic, or political challenges. However, benefits to be derived from their implementation should be substantial in preventing disease progression, promoting healthy life years gained, and preventing new HIV infections.

In formulating these recommendations, the Panel intentionally avoided distinguishing between behavioral and biomedical interventions, choosing to emphasize that providing prevention in care —for people living with or at risk for HIV infection—requires a combination of activities.

METHODS

A systematic literature review using Medline and EMBASE was conducted to identify relevant published data. Results presented at scientific conferences in abstract form were considered. Specific search terms and limits are detailed in the supplemental section on the process of recommendation development (eMethods). Approximately 250 related manuscripts were selected based on scientific evidence or other consensus guidance. Panel members also conducted hand searches for newly published reports and abstracts from scientific conferences throughout the process. Data not published or presented in a peer-reviewed setting were not considered.

Recommendations (Box 1) were developed by the IAS-USA HIV Prevention Recommendations Panel, an international panel of experts in HIV biomedical and behavioral science and practice.The Panel convened in person in March 2013 and met regularly by teleconference thereafter. Panel members served in a volunteer (no financial compensation) capacity and do not participate in industry promotional activities such as speaker bureaus, lectures, or other marketing activities during Panel membership. Teams evaluated evidence and summarized Panel discussions for each section. Prior to convening, members declared and discussed potential conflicts of interest and recused themselves from serving as section leaders or team members accordingly. A description of the Panel process is included in the supplemental section on the process of recommendation development.

Box 1. Recommendations for Combination HIV Prevention.

A. HIV TESTING AND KNOWLEDGE OF SEROSTATUS

Recommendations

- All adults and adolescents should be offered HIV testing at least once. Rating: AIII

-

∘To direct the need for additional testing, clinicians should periodically assess HIV-related risks, including sexual and drug-use activities, in all adults and adolescents.

-

∘Persons at higher risk (those engaging in risk behaviors or residing in areas of or testing at venues with high seroprevalence) should be tested more frequently, at intervals appropriate to the individual’s situation.

-

∘

All persons should be informed prior to undergoing HIV testing; however, pretest counseling should be sufficient only to meet the individual’s needs and to comply with local regulations. The right to refuse testing must be honored, but clinicians should ensure that refusals are informed decisions. Rating: AIII

As the circumstances warrant and depending on the test used, at risk persons who test HIV-seronegative should receive information about the possibility of a false-negative test during the window period and should be encouraged to obtain repeat testing at an appropriate time. Rating: AIIa

- Approach to testing:

-

∘Tests with the best performance (sensitivity/specificity) should be used. Rating: AIIa

-

∘Rapid testing should be prioritized for persons less likely to return for their results. Rating: AIIa

-

∘Couples testing should be accommodated and encouraged. Rating: AIa

-

∘Self-testing and home testing should be considered for those who have recurrent risk and/or have difficulties with testing in clinical settings; further research is needed to evaluate their safety and effectiveness and options for follow-up, especially linkage to care. Rating: BIII

-

∘

B. Prevention Measures Specific to HIV-Infected Individuals Antiretroviral Therapy

Recommendations

Clinicians should provide education about the personal health benefits of ART and the public benefits of prevention of transmission, and assess patients’ readiness to initiate and adhere to long-term ART. Rating: AIII

ART should be offered upon detection of HIV infection. Rating: A1a

Strategies for adherence support should be implemented and tailored to individual patient needs or the setting. Rating: AIa

Clinicians should be alert to the non-specific presentation of acute HIV infection and urgently pursue specific diagnostic testing (plasma HIV viral load) if this is suspected. Rating: AIIa

Counseling on Risk Reduction, Disclosure of HIV Serostatus, and Partner Notification

Recommendations

Regular assessment of sexual and substance use practices should be performed in HIV-infected persons to direct individualized risk-reduction counseling, which should be delivered in combination with STI screening, condom provision, and harm reduction services (discussed below) for PWID, and integrated with strategies to maintain adherence. Rating: AIII

Assistance should be provided for patient- or clinician-based notification of sex and injection drug use partners to facilitate the patient’s testing and linkage to care as well as efforts to disclose HIV infection to relevant partners and other key persons. Rating: AIII

Needle Exchange and Other Harm Reduction Interventions Among People Who Inject Drugs

Recommendations

Simultaneous access to ART, needle and syringe exchange programs, supervised injection sites, medicalized heroin and medically- assisted therapy (which includes opioid-substitution therapy) should be provided to HIV-infected PWID. Rating: AIa for each element; AIII for the combination

For individuals who use substances in ways other than injection, ART with adherence support and behavioral counseling should be provided. Rating: AIIa

C. INDIVIDUAL-AND STRUCTURAL-LEVEL INTERVENTIONS TO PROMOTE MOVEMENT OF HIV-INFECTED PERSONS THROUGH THE CONTINUUM OF HIV CARE: ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

Recommendations

Linkage to HIV care for HIV-infected individuals is an essential component of expanded HIV testing and should be actively facilitated as soon as possible following a new diagnosis of HIV. Rating: AIa

Strengths-based case management interventions should be used to facilitate linkage to and retention in HIV care. Rating: AIa

Additional patient support services, including patient health navigation, community and peer outreach, provision of culturally appropriate print media, verbal messages promoting health care utilization and retention from clinic staff, and youth-focused case management and support, are recommended. Rating: AIIa

SECTION D. PREVENTION MEASURES AIMED AT HIV-UNINFECTED INDIVIDUALS

Risk Assessment and Risk Reduction for HIV Infection

Recommendations:

A specific risk assessment covering recent months should be conducted to determine the sexual and substance use practices that should be the focus of risk reduction counseling and appropriate risk reduction services should be offered. Rating: AIa

For people at high risk for HIV infection who test HIV-seronegative, risk-reduction interventions or services are warranted, especially for individuals and couples who seek repeat HIV testing to monitor seroconversion. Rating AIa

Preexposure Prophylaxis

Recommendations

- Daily FTC/TDF as PrEP should be offered to the following persons:

-

∘Persons at high risk for HIV based on background incidence (> 2%) or recent diagnosis of incident STIs, especially syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia. Rating: AIa

-

∘Individuals who have used postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) more than twice in the past year. Rating: AIIa

-

∘PWIDs who share injection equipment, inject 1 or more times a day, or inject cocaine or methamphetamines. Rating: AIa

-

∘

PrEP should be part of an integrated risk-reduction strategy, so its use may become unnecessary if a person’s behavior changed. Thus, clinicians should regularly assess their patients’ risk and consider discontinuing PrEP if the sexual and partnering practices or injection drug use behaviors that involved exposure to HIV change. Rating: AIII

HIV-infected persons should be asked about the HIV serostatus of their sexual partners, and PrEP should be discussed if they have regular contact with HIV-uninfected partners. Partners whose HIV serostatus is unknown should undergo counseling and testing. Considerations should include whether the infected partner’s viral load is suppressed on ART, access to care for the uninfected partner, and coverage of associated costs. Rating: AIIb

HIV testing should be performed before starting PrEP, ideally with a sensitive, combination antigen-antibody assay capable of detecting acute or early infection (a fourth-generation assay), and regularly (monthly to quarterly depending on individual risk) thereafter. Screening for clinical symptoms that may signal acute infection should be performed. In suspected cases of acute HIV infection, plasma HIV viral load should be determined immediately and PrEP should be deferred until acute infection is ruled out. Rating: AIa

Persons to be given TDF-based PrEP should have a creatinine clearance rate of at least 60 mL/min. Data are not available to inform a recommendation for PrEP for persons with a creatinine clearance rate of less than 60 mL/min. Rating: AIa

Immunity to HBV should be ensured for all persons initiating TDF-based PrEP. Rating AIIa

Postexposure Prophylaxis

Recommendations

PEP should be offered to all persons who have sustained a mucosal or parenteral exposure to HIV from a known infected source as urgently as possible and, at most, within 72 hours after exposure. Rating: AIIb

The PEP regimen should consist of the USPHS preferred regimen, which is currently FTC/TDF and raltegravir. Rating: BIIb

Women who receive PEP should be offered emergency contraception to prevent pregnancy. Rating: BIIb

Persons who receive PEP should be rescreened with a fourth-generation HIV antigen and antibody test 3 months after completion of the regimen. Rating: BIIb

Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision

Recommendations

Voluntary medical male circumcision should be recommended to sexually active heterosexual males for the purpose of HIV prevention, especially in areas with high background HIV prevalence. Rating: AIa

Voluntary medical male circumcision should be discussed with MSM who engage in primarily insertive anal sex, particularly in settings of high HIV prevalence. Rating: BIIb

Parents and guardians should be informed of the preventive benefits of male infant circumcision.250 Rating: BIIb

E. PREVENTION ISSUES RELEVANT TO ALL PERSONS WITH OR AT RISK FOR HIV-1 INFECTION

Screening and Treatment for Sexually Transmitted Infections

Recommendations

Routine, periodic screening for common STIs at anatomic sites based on sexual history should be performed (Box 3). Rating: BIIa

HIV-infected persons should be tested for HCV at entry to care and assessed at regular intervals for related risks, including higher-risk sexual practices. Rating: BIIa

Quadrivalent HPV vaccination should be offered to all HIV-infected persons who fulfill the Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices (ACIP) criteria for its administration. Rating: AIIa

Immunity to HBV should be ensured for all HIV-infected persons in care who have not already been infected with HBV. Rating AIIa

Routine screening for HSV-2 infection should be considered for HIV-infected persons who do not know their HSV-2 serostatus and wish to consider suppressive antiviral therapy to prevent transmission of HSV-2. Rating: CIa

Reproductive Health Care: Hormonal Contraception

Recommendations

Current data are not sufficiently conclusive to restrict use of any HC method, and women using progestin-only injectable contraception should be advised to also always use condoms and other HIV preventive measures as feasible. In the interim, HIV-infected women should be counseled with regard to the availability of a range of options for family planning, including HC. Rating: BIIa

Panel recommendations were limited to HIV prevention for clinical care settings for non-pregnant adults and adolescents. Recommendations for prevention included ART that was available (approved by regulatory bodies or in expanded access) or in late-stage development (new drug application filed). Recommendations were made by full-panel consensus and rated according to strength of the recommendation and quality of supporting data (Box 2).3 Ratings were provided only for recommendations supported by clinical or observational study data. The Panel developed these recommendations to comprise a compendium of best practice regardless of clinical setting; thus, they are relevant to the global community. However, most of the cost-effectiveness literature cited is specific to the United States and other well-resourced settings, such as Canada, Western Europe, and Australia. To the extent that resource utilization, care structures, and ART costs vary widely across different settings, the economic discussions should be interpreted accordingly.

SECTION A. HIV TESTING AND KNOWLEDGE OF SEROSTATUS

Self-knowledge of HIV serostatus is the pivotal step in directing interventions to prevent HIV infection, enabling linkage of newly diagnosed persons to care and provision of prevention interventions to those found to be HIV-seronegative but at risk of infection. Despite this, approximately 50% of people living with HIV worldwide—and 16% of those in the United States—do not know their serostatus.4 Moreover, HIV-infected persons who are unaware of their serostatus may account for as much as 45% of new HIV infections in the United States.5 In addition, persons who receive a positive HIV test result often reduce their HIV-related risk behaviors.5–7

In 2006, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued guidelines recommending routine opt-out HIV testing in health care settings;8 despite this, many missed opportunities for testing in clinical care continue to occur. In 2013, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommended routine HIV screening for all persons aged 15 to 65 years.9 Both of these guidelines note that where prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection is 0.1% or less, routine screening may be supplanted by screening on the basis of risk assessment.

New developments such as HIV rapid tests, fourth-generation antibody and antigen assays (eTable),10 fewer legal barriers to testing, and integration of screening in diverse settings should facilitate increases in HIV testing and early diagnosis, timely receipt of results, and better linkage to care.11 Home- and community-based testing strategies, including self-testing, are especially important for populations with unmet health care needs.12 Fourth-generation assays allow clinicians to detect some acute and recent HIV infection, narrowing the window between infection and diagnosis to approximately 15 to 20 days, thus allowing diagnosis of persons who are often highly infectious.13 New diagnostic algorithms also omit the need for routine confirmatory Western blot testing.14 The CDC Sexually Transmitted Disease Treatment Guidelines recommend that men who have sex with men (MSM) who have multiple or anonymous partners, have sex in conjunction with illicit drug use, use methamphetamine, or who have sex partners who participate in these activities be screened for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV more frequently (every 3 to 6 months) than MSM without such risk factors.15

For couples who are or plan to be sexually active, HIV testing is an effective intervention for both heterosexual and same-sex couples.16,17 With couples HIV testing, participants receive all elements of testing and counseling together; individuals learn not only of their own HIV serostatus but also that of their partner(s), which facilitates the delivery of tailored prevention messages and care plans.

Counseling associated with HIV testing is a complex topic. In the United States, State laws vary as to what is required.18 At a minimum, individuals should know that they are being tested. Some studies have found that counseling conducted at the time of HIV testing serves to reduce HIV-related risk behaviors and subsequent STIs; some studies did not demonstrate these effects.19–30 Counseling should not be an impediment to HIV testing. Indeed, the CDC’s current guidance states that prevention counseling should not be required with HIV diagnostic testing or as part of HIV screening programs in health-care settings.8 Finally, the economic value of HIV screening is well-substantiated and is enhanced when transmission prevention benefits associated with screening are included.31–33

Brief risk assessment and brief clinically feasible risk reduction services may be considered for persons at high risk of HIV infection, including those with an incident STI, evidence of injection drug use, or who report sexual or drug using risk. In the sections below, we discuss these services both for persons living with HIV and for persons at increased risk for HIV infection (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Centers for Disease Control Best and Good Levels of Evidence for Prevention Interventions for Persons Living With HIV/AIDS

| Intervention Name |

Design | Sample | Duration and Study Period |

Major Outcomes | Level of Evidence per CDC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLEAR (adapted from Teens Linked to Care)96,106 | Community-based, individual-level intervention RCT(telephone vs in-person vs delayed delivery) with 15-month follow-up | 175 Young PLWH at risk of substance abuse | 18 weekly 2-hour sessions 1999–2002 | 20 percentage point increase in protected sex acts with seronegative parners and 13 percentage point increase in overall protected sex acts (in-person delivery) | Best |

| Eban107 | Couple-based intervention RCT with group and single-couple sessions with 12-month follow-up | 535 African American serodiscordant couples (1070 individuals) | 8 weekly 2-hour sessions 2003–2007 | 63% consistent condom use in intervention group compared with 48% in control group | Best |

| Healthy Living Project97 | Community-based, individual-level intervention RCT with 5-, 10-, 15-, 20-, and 25-month follow-up | 936 PLWH considered at risk of transmitting | 15 90-minute sessions 2000–2002 | 36% reduction in risk acts between intervention and control groups at 20-month follow-up | Best |

| Healthy Relationships98 | Skill-based, small-group intervention RCT with 3- and 6-month follow-up | 332 PLWH | 5 2-hour, twice-weekly sessions 1997–1998 | 17 percentage points higher in condom use for vaginal and anal sex acts in intervention group than in control group at 6-month follow-up | Best |

| In the Mix70 | Individual and group-level intervention RCT with 3-, 6-, and 9-month follow-up | 436 PLWH | 1 45-minute individual session, 5 2-hour group sessions, 1 60-minute individual session over 5 weeks 2005–2009 | 66% fewer unprotected sex acts in intervention group than in control group at 6-month follow-up** | Best |

| LIFT99 | Group-level intervention RCT (coping group vs support group) with 4-, 8-, and 12-month follow-up | 247 PLWH with history of childhood sexual abuse | 15 weekly 90-minute sessions 2002–2004 | Coping group reduced unprotected sex acts by an average of 54% at 12-month follow-up compared with support group | Best |

| Positive Choice: Interactive Video Doctor100 | Computerized individual-level intervention RCT with 3- and 6-month follow-up | 476 PLWH | 1 computer-based session 2003–2006 | 15% fewer unprotected sex acts in intervention group than in control group at 6-month follow-up | Best |

| Seropositive Urban Men’s Intervention Trial (SUMIT)101 | Group-level intervention (standard intervention vs enhanced intervention) RCT with 3- and 6-month follow-up | 811 HIV-seropositive MSM | 6 3-hour, weekly sessions (enhanced), 1 1.5- to 2-hour session (standard) 2000–2002 | 5% fewer participants reported unprotected acts of receptive anal sex in enhanced group than in standard group at 3-month follow-up | Best |

| Treatment Advocacy Program (TAP)108 | Individual-level primary care–based intervention RCT with 6- and 12-month follow-up | 313 HIV-seropositive MSM | 4 60- to 90-minute sessions over 8 weeks, 3-month check-in call, 2 15- to 90-minute follow-up sessions at 6 and 12 months 2004–2006 | 20% transmission risk in intervention group at 6- and 12-month follow-up compared with 23%−25% in control group | Best |

| WiLLOW102 | Group-level intervention RCT with 6- and 12-month follow-up | 366 sexually active HIV-seropositive adult women | 4 4-hour, weekly sessions 1997–2000 | 44.3% reduction in mean number of unprotected vaginal sex acts (past 30 days) in intervention group compared with control group at 12-month follow-up | Best |

| Options/Opciones Project103 | Individual-level intervention randomized to study arms (intervention vs standard of care) with 18-month follow-up period | 497 PLWH | 5- to 10-minute session repeated at each clinic visit for 18 months 2000–2003 | 79% decrease in average number of unprotected sex acts in intervention group over the 18-month period** | Good |

| Partnership for Health95 | Individual-level intervention randomized to study arms (gain-frame vs loss-frame vs attention-control) with 7-month follow-up period | 585 sexually active PLWH | 3- to 5-minute session repeated at each clinic visit 1999–2000 | 38% decrease in unprotected sex acts among PLWH with 2 or more partners in loss-frame arm at follow-up | Good |

| SafeTalk109 | Individual-level intervention RCT with 4-, 8-, and 12-month follow-up | 490 PLWH | 4 40- to 60-minute monthly sessions 2006–2009 | 66% reduction in unprotected sex acts in intervention group at 12-month follow-up, compared with 30% reduction in control group** | Good |

| Together Learning Choices (TLC)104 | Group-level intervention controlled trial with 9- and 15-month follow-up | 310 HIV-seropositive adolescent and young adult clinic patients | 23 2-hour sessions delivered over 2 3-month period 1994–1996 | 82% fewer unprotected sex acts in intervention group than in control group | Good |

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CLEAR, Choosing Life: Empowerment, Actions, Results!; LIFT, Livelihoods & Food Security Technical Assistance; MSM, men who have sex with men; PLWH, people living with HIV/AIDS; RCT, randomized controlled trial; WiLLOW, Women Involved in Life Learning from Other Women.

Adapted from CDC, 2013105

The CDC evaluation of these interventions is dynamic process; current information is available at:

Percentage reduction calculated from data presented in reference.

Note: A recently published systematic review of risk reduction interventions for PLWH provides additional detailed information on evidence-based and promising studies in the United States.94

Table 2.

Brief Behavioral Interventions for HIV-Uninfected Persons

| Intervention Name |

Design | Sample | Duration and Study Period | Major Outcomes | Level of Evidence per CDC* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus on the Future176 | Individual-level intervention RCT (motivational interviewing, skill-building, condom information) with 3- and 6-month follow-up | 266 young adult, African American, heterosexual men | 1 45- to 50-minute session2004–2006 | Intervention group less likely to experience reinfection than control group (31.9% vs 50.4%), more likely to have used condoms in most recent intercourse than control group (72.4% vs 53.9%), and reported fewer sexual partners than control group (2.06 vs 4.15) | Best |

| Personalized Cognitive Risk-Reduction Counseling28 | Individual-level counseling intervention RCT with 6- and 12-month follow-up | 248 MSM | 1 1-hour session (with optional diary)1997–2000 | Reduction in participants reporting unprotected sex with nonprimary partners (66% baseline, 21% at 6-month follow-up, 26% at 12-month follow-up) | Best |

| Sister-to-Sister: One-on-One Skills Building179 | Individual-level skill-building intervention RCT with 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up | 564 African American women | 1 20-minute session1993–1996 | 70% of intervention group reported practicing protected sex at 12-month follow-up vs 62% of control group | Best |

| N/A177 | Individual-level counseling (skills training) intervention 3-arm RCT with 4- and 18-month follow-up | 492 adults attending an STI clinic in the United Kingdom | 1 20-minute session1991 | Intervention group more likely than control groups to carry condoms if they thought sex with a new partner was likely (71% vs 63% and 49%) | N/A |

| Mujer Segura178 | Individual-level counseling intervention RCT with didactic control group with 6-month follow-up | 924 HIV-negative female sex workers in Mexico | 1 35-minute session | 40% decline in STI incidence in intervention group, 27.4 percentage point increase in condom use in intervention group compared with 17.5 percentage point increase in control group | N/A |

| Safe in the City181 | Individual-level video intervention controlled trial randomized by location/time with 14.8-month average follow-up | 38,635 adults attending 1 of 3 STI clinics | 1 23-minute session2003–2005 | 4.9% incidence of STIs in intervention group vs 5.7% in control group at 14.8-month follow-up | Best |

| Safer Sex180 | Individual-level intervention RCT with 1-, 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up | 123 adolescent girls with an STI | 1 30-minute or longer session (including a 7-minute video) with booster sessions at follow-up appointments1996–1999 | 60% of intervention group reported protected sex at last sexual encounter at 12-month follow-up vs 53% of control group | Good |

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control; RCT, randomized controlled trial; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

The CDC evaluation of these interventions is dynamic process; current information is available at:

For recommendations regarding HIV testing and knowledge of HIV status, see Box 1.

SECTION B. PREVENTION MEASURES SPECIFIC TO HIV-INFECTED INDIVIDUALS

Antiretroviral Therapy

Suppression of infectious HIV-1 in blood and genital secretions through provision of ART is highly effective in reducing—indeed, largely eliminating—the risk of ongoing HIV transmission. Observational studies of heterosexual couples confirmed that successful ART reduces probability of HIV transmission.34,35 In 11 of 13 such studies, almost no HIV transmission was observed when the infected partner was receiving ART.36,37 In studies in which transmission events occurred despite ART, the HIV-infected participants were likely not reliably adherent to ART.38 A prospective observational study of 767 serodiscordant couples (the PARTNER Study), 40% of which were same-sex male couples, recently reported no HIV transmission occurring over an estimated 894 couple-years of observation during which the majority of penetrative anal or vaginal sex was condomless, and where the HIV-infected partner was on ART.39

The HPTN052 (HIV Prevention Trials Network 052) study40 was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) undertaken to prospectively determine the prevention benefit of ART. Among 1763 HIV serodiscordant couples in 9 countries, HIV transmission was reduced by more than 96% during a period of 18 months by adding ART to standard prevention strategies. The results also demonstrated a clinical benefit (reduction in incident tuberculosis) to individuals offered ART at CD4 cell counts > 350/mL compared with ART initiation at CD4 cell counts < 250/mL.41 An ecological study among people who inject drugs (PWID) in Vancouver, British Columbia, suggested that ART significantly reduces spread of HIV infection.42 In Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa, for every 1% increase in ART use, a 1.4% decrease in HIV incidence was observed.43 An association of similar magnitude was established in a population-based analysis in British Columbia.42,44

The President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR)45 and the World Health Organization (WHO)46 now recommend that HIV-infected persons whose sex partners are HIV-uninfected be offered immediate initiation of ART, irrespective of CD4 cell count. The IAS–USA47 and US Department of Health and Human Services48 recommend that ART initiation be offered to persons with HIV infection, regardless of CD4 cell count, for both individual health and transmission prevention benefits. Most recently, the WHO has recommended that ART be offered at CD4 cell counts ≤ 500/mL regardless of symptoms, and at CD4 cell counts > 500/mL in a number of specific clinical settings.46 Extrapolating from observed individual and population benefits, studies have demonstrated that in the United States, expanded screening (one time in low-risk and annually in high-risk persons, such as those in serodiscordant partnerships or with multiple sex partners) with immediate ART initiation for individuals who test HIV-seropositive is a cost-effective method of transmission prevention.49 Early ART targeted to HIV serodiscordant couples has also been projected to be cost effective in resource-limited settings.50

Recent ecological analyses from areas where MSM are most affected by HIV infection have not reported declines in HIV incidence or prevalence as ART use has expanded, despite the encouraging data from the PARTNER Study.39,51 Sustained HIV transmission from untreated (or inconsistently treated) MSM with high levels of plasma and genital HIV RNA is likely driving these epidemics.51–53

Acute and early HIV infection may limit the effect of ART on the prevention of HIV transmission. During this period, plasma and genital viral loads reach high concentrations and may remain elevated for several months. Very few people learn their serostatus during this period.54 Newer HIV tests11 and testing algorithms that incorporate HIV-1 RNA testing may enhance the likelihood of detection during this time, but the overall effect is likely to be small because the clinical diagnosis of acute HIV infection is frequently not suspected.55 Because people with acute and early HIV infection contribute disproportionately to the spread of HIV,56,57 correct diagnosis and prompt intervention are needed.6 Small studies of the sexual behavior of people with early HIV infection do not suggest that behavior change alone will suffice, thus immediate, lifelong ART is recommended.58 Early treatment preserves CD4 cell counts59 and reduces ongoing viral diversification and the size of the viral reservoir.60, 61 Moreover, failure to provide ART during a clinical encounter that occurs early in the disease can result in loss to follow-up with the patient who may re-engage with care only when they have developed an HIV-related complication. 62

Adherence to ART is crucial for sustained HIV-1 suppression. Consistent with the current International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care guidelines, once-daily, fixed-dose combination ART is preferred whenever possible.47,48,63 Even with such regimens, full adherence can be challenging. Behavioral interventions64 that have shown promise include brief psychosocial counseling, such as cognitive behavioral therapy,65–69 risk-reduction behavioral interventions,70 motivational interviewing,69,71,72 managed problem-solving counseling,73 adverse effects coping interventions,74 peer-led social support groups,75,76 and counseling interventions for specific populations, including recently released inmates,77 youth,78 urban-dwelling HIV-seropositive individuals with depression,79 and persons with low health literacy skills.80,81 Personalized phone calls are effective, and computer-administered adherence promotion has shown promise.82–84 Among PWID, medication-assisted therapy and directly administered ART have improved adherence.85,86 For recommendations regarding the preventive benefits of ART, see Box 1.

Risk Reduction, Disclosure of HIV Serostatus, and Partner Notification

Behavioral interventions have been shown to reduce sexual risk behaviors, increase condom use, and reduce subsequent STIs among persons living with HIV (Table 2).70,87–109 CDC has identified effective, evidence-based behavioral risk-reduction interventions developed for people living with HIV (Table 1).105 As seen in Table 2, some of the “best” and “good” evidence (as labeled by CDC) were developed before ART was widely available, and some are very recent. A subset of these interventions has been subjected to economic evaluation and shown to be cost effective.92,93 Further, some of the interventions described in Table 1 are brief and could be provided in a clinical setting, whereas others are more intensive and would likely be referred to other providers.

In the current era, although implementation of universal ART for HIV-infected persons remains incomplete, expanded use of ART at all stages of HIV infection has changed the dynamic between related risk behaviors and their attributable effects. The impact of ART on sexual behavior is likely complex and depends on numerous factors at the individual level.94 Ongoing behavioral risk assessment is a critical component of care for persons with HIV, and should inform a discussion of risk reduction. However, data indicate that despite evidence of benefit, only 61% of people living with HIV who engage in risk behavior with serodiscordant partners receive risk-reduction prevention services.110 Effective behavioral risk-reduction strategies are typically delivered using individualized counseling techniques, including motivational interviewing111,112 and skills-based counseling.113,114 In settings where such counseling cannot be delivered, clinicians should at minimum conduct a brief risk assessment115,116 and refer patients to available relevant health services. Risk screening protocols117 may be useful to identify individuals in need of more intensive counseling in busy clinical settings118 or to monitor for incident STIs119 or clinical indications of injection drug use. Importantly, risks identified during these conversations should facilitate discussion about potential effects of ongoing risk behavior, even in the setting of successfully suppressed plasma HIV viral load. For example, inflammation caused by genital STIs or other inflammatory processes can increase HIV-1 RNA levels in genital secretions even when plasma HIV is suppressed by ART, thus rendering the “fully suppressed” person potentially infectious.120 In addition, superinfection (acquisition of a second HIV strain after an immune response to the initial strain has been established) may be relatively frequent in some populations, and may be associated with poor clinical outcomes.121 Finally, treatment for HIV does not affect the risk for acquisition of other STDs.122

Persons with HIV should receive guidance and support in disclosing infection to sex and drug injection partners. In some jurisdictions, legislation that criminalizes HIV exposure may discourage HIV-infected persons from disclosure; thus, it is important to know the relevant legal context and to be aware of resources that may facilitate this process.123 Some care settings have formalized HIV partner management programs and demonstrated enhanced effectiveness of partner elicitation and notification.124,125 If self-disclosure is used, crucial factors to discuss are how to prepare for disclosure, to whom it will be made, when and how it will take place, how it can affect the client and persons to whom disclosure is made, and the stressful nature of the process.126

For recommendations regarding risk reduction counseling, status disclosure, and partner notification, see Box 1.

Needle Exchange and Other Harm Reduction Interventions Among People Who Inject Drugs

Simultaneous scale-up of combining access to ART, opioid substitution therapy, and harm reduction services can greatly reduce the incidence of HIV infection among PWID, and is supported by technical guidelines from the WHO, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).127–129 In an ecological study in Vancouver, British Columbia, increased ART coverage corresponded with reduction in “community median plasma viral” load and an approximately 50% reduction in new HIV diagnoses, including those among PWID.42 More recently, a population-based analysis in British Columbia demonstrated a province-wide decline in new diagnoses of HIV infection of greater than 90% that was largely attributed to the expansion of harm reduction programs coupled with enhanced ART coverage among PWID.44 Unfortunately, people who use drugs face widespread barriers to accessing ART in many settings.130

Treatment for opiate addiction with opioid substitution therapies, especially methadone, increases the likelihood that PWID will initiate ART.131 Once initiated, methadone maintenance increases ART adherence, including among homeless persons.132 Opioid substitution therapies likely reduce HIV transmission by reducing illicit opioid use, sharing of injection equipment, numbers of sex partners, and exchange of sex for drugs or money.133 In addition, there is no evidence of increased sexual risk behavior after initiating ART among PWIDs.134,135 Of note, use of opioid substitution therapies should be voluntary; coercive treatment does not prevent HIV transmission and does not treat addiction.136

Needle and syringe exchange programs link individuals to health care services and provide sterile injection equipment and supplies, reducing associated transmission risks. No RCTs document efficacy for these programs, although observational reports support their use. Health outcomes among PWID living in New York City when syringe exchange was legal were compared with those among PWID living in Newark, New Jersey, when exchange was illegal. PWID living in Newark had substantially higher prevalence rates of HIV, hepatitis C virus (HCV), and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections and more frequent self-reported needle reuse and sharing.137 Access to a supervised injection facility favorably impacts individual health outcomes,138–140 risk behaviors,141,142 and societal outcomes.143 Moreover, the use of medicalized heroin in a supervised injection facility has clinical benefit144 and is cost effective.145

In contrast, although most persons who use drugs take them by mouth, insufflation, smoking, or anal or vaginal insertion rather than injection, data that might inform HIV prevention strategies targeted at such non-injection drug use is limited. Approaches to HIV prevention for substance users are consistent with those used among non–substance users and should emphasize prevention of sexual transmission. Emerging data support novel strategies, including medications to treat stimulant dependence in MSM146 and reduce risk behaviors in active stimulant users.147 For recommendations regarding prevention in people who inject drugs, see Box 1.

SECTION C. INDIVIDUAL-AND STRUCTURAL-LEVEL INTERVENTIONS TO PROMOTE MOVEMENT OF HIV-INFECTED PERSONS THROUGH THE CONTINUUM OF HIV CARE: ADDITIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

The HIV care continuum provides a representation of the steps necessary to take HIV-infected persons from diagnosis to suppression of plasma HIV-1 viral load. The value of investing in linkage to care after a new HIV diagnosis has been demonstrated.148,149 A model-based study demonstrated that investments along the most distal part of the care continuum (ensuring adherence, linkage, and retention) were more economically efficient than those devoted to increase HIV screening.150

Moving individuals across the HIV care continuum can be arduous for those on the margins of the health care delivery system.151,152 Interventions that consider the individual’s social environment and attendant structural factors produce more positive and sustainable outcomes compared with those that do not.153 Commonly cited community or structural barriers include fear of being stigmatized because of an HIV diagnosis; joblessness resulting from disclosure; inability to afford health care; homelessness or unstable housing; incarceration; lack of a supportive social network; food insecurity; and legal, legislative, and policy factors that pose obstacles to addressing these concerns.154,155

For these reasons, structural and community-level interventions (broadly defined as those that build on the awareness that environmental, social, political, and economic factors are potential sources of HIV risk and vulnerability) are increasingly important.155

Linkage to Care

The period after a person is initially diagnosed with HIV represents a critical opportunity to establish linkage to care. Failure to do so at this juncture reduces the opportunity to address current health issues, access preventive services, and initiate timely ART. However, data to inform interventions to ensure that this linkage is made are sparse. One RCT evaluated a brief (up to 5 sessions) case management intervention focused on identifying individual strengths, reducing barriers to obtaining care, and accompanying persons to appointments. Compared with passive referral, the intervention was more effective.156 Use of outreach efforts, financial incentives, navigation assistance, partner services, and social marketing have successfully engaged individuals from underserved and marginalized populations, including persons of color and MSM.157–159 Further research is needed to identify barriers to care and optimal strategies for increasing linkage to care. New approaches to program science should inform this process and are especially important in resource-limited settings.

Retention in Care

Consistent retention in care has been associated with shorter time to viral load suppression, lower cumulative viral load burden, improved immune function, decreased mortality, and decreased engagement in HIV transmission behaviors.160,161 A large observational study found that retention increased substantially after the implementation of clinic-wide interventions, including print reminders and brief verbal messages used by all clinic staff.162 Patient navigation interventions, community and peer outreach, print media, verbal messages from clinic staff, financial incentives, and youth-focused case management and support have been associated with increased retention in care.84,163–166 For HIV-infected, opioid-dependent individuals, one RCT demonstrated that medication-assisted drug treatment (buprenorphine and naloxone) was associated with increased retention in care.167 For recommendations regarding clinic-wide interventions, see Box 1.

SECTION D. PREVENTION MEASURES AIMED AT HIV-UNINFECTED INDIVIDUALS

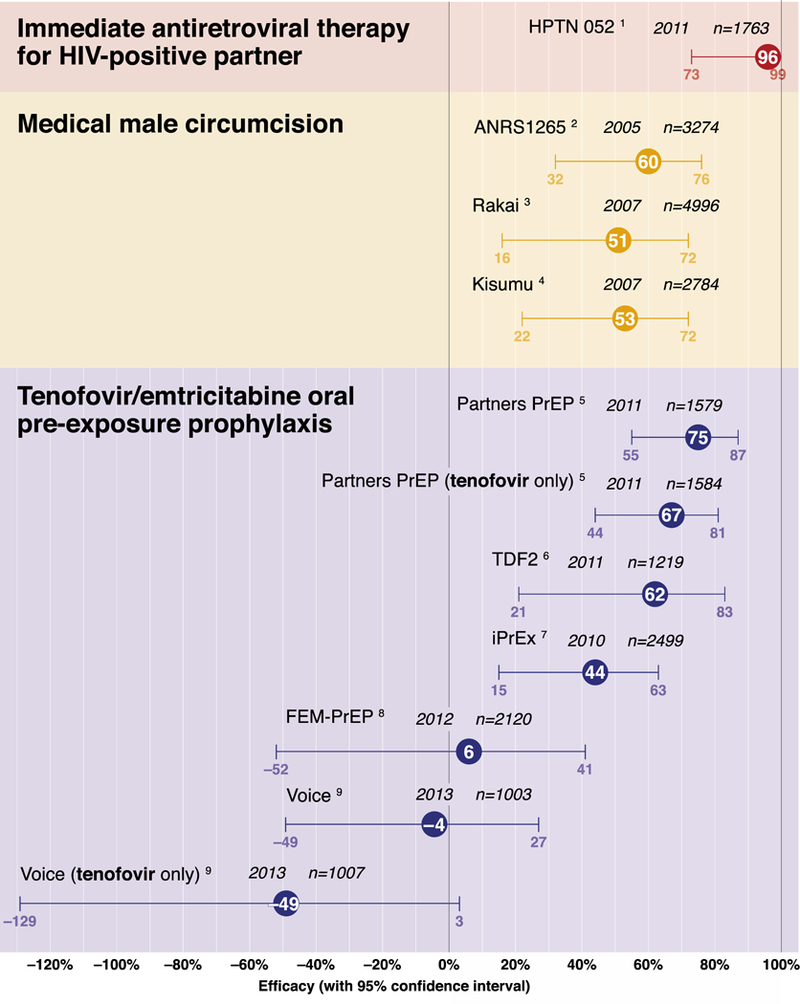

Until recently, the prevention of HIV infection for uninfected individuals was focused only on behavioral interventions. Although these continue to be important, effective biomedical approaches are now available (Figure 1). Importantly, all biomedical prevention trials have also included state-of-the-art behavioral counseling as part of the approach. Thus, HIV prevention should not be considered as either behavioral or biomedical but rather as a combination intervention.

Figure 1.

Efficacy of Biomedical Interventions to Prevent HIV Acquisition: Summary of the Evidence from Randomized Clinical Trials

Risk Assessment and Risk Reduction for HIV Infection

There is strong evidence that brief behavioral counseling delivered to persons at risk for HIV infection reduces sexual risk behaviors, increases condom use, and reduces subsequent STIs including HIV.87–91,105,168–172 The Explore Study, a multicity, randomized trial of a 10-session counseling intervention among MSM, demonstrated a 39% reduction in HIV incidence over a 12- to 18-month period after counseling and an 18% reduction in incidence over a 48-month period.173,174These findings are bolstered by a meta-analysis of randomized trials that tested much briefer, single-session sexual risk reduction counseling interventions that embodied similar principles of behavior change.175 Reductions in incident STIs have been demonstrated to result from brief interventions of skills-based individualized counseling in trials with high-risk men and women, and a number have been labeled as “best” or “good” evidence-based interventions by CDC (Table 2).28,105,176–181 Not surprisingly, interventions that involved a longer duration of a single counseling session were more effective than those of briefer duration. Face-to-face counseling interventions also had greater effects than media-delivered messages. Risk reduction counseling can be delivered alone or ideally in combination with biomedical prevention strategies targeting HIV-uninfected persons.5,105,182,183

The most effective individualized counseling provides patients with self-management skills and condoms.87,184,185 In addition, content analyses of effective counseling have identified common principles that promote preventive behaviors: fostering a sense of self-belief and self-worth, distinguishing fact from myth, evaluating options and consequences, formulating commitment to change, planning skills, promoting self-control, establishing pleasurable alternatives to high-risk sexual activity, negotiating safer behaviors, setting limits, and acting to help others protect themselves.186 Although various counseling approaches have nuances tailored to particular populations and service settings, most are well suited for use in combination with biomedical prevention technologies. For recommendations regarding risk reduction counseling for HIV-uninfected persons, see Box 1.

Preexposure Prophylaxis

PrEP with daily oral emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF) as a fixed-dose combination decreases HIV-1 acquisition among MSM,187 serodiscordant heterosexual couples,188 and heterosexual adults189 (Table 3). Daily oral TDF alone was effective for PrEP in heterosexual couples188 and PWID190. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved daily oral FTC/TDF for HIV prevention in 2013, and the CDC has issued guidance for its use.191

Table 3.

Completed Clinical Trials on Preexposure Prophylaxis with Antiretroviral Drugs

| Study (Location) |

Popula tion |

Design | Relative Reduction in HIV Incidence in Intention- to-Treat Analysis |

PrEP Detection in Blood Samples From Nonseroconverter s |

HIV Protection Estimate as Related to Adherence |

Safety |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partners PrEP Study 188(Kenya,Uganda) | 4747 heterosexual men and women with known HIV-infected partners,serodiscordant couples | 1:1:1 randomization to dailyoral TDF, FTC/TDF, orplacebo | TDF: 67% (95% CI, 44%−81%)FTC/TDF: 75% (95%CI, 55%−87%) | 81% | 86% (TDF), 90% (FTC/TDF) in subjects with detectable tenofovir levels | • No significant differences in the frequency of death, serious adverse events, or serum creatinine or phosphorus level abnormalities between study groups • Increased creatinine levels and decreased phosphorus levels in less than 1% of all patients |

| TDF2 Study189 (Botswana) | 1219 heterosexual men and women | 1:1 randomization to daily oralFTC/TDF or placebo | FTC/TDF: 63% (95% CI, 22%−83%) | 79% | 78% excluding follow-up periods when subjects had no PrEP refills for 30 days | • FTC/TDF group had higher rates than the placebo group of nausea (18.5% vs 7.1%; P < .001), vomiting (11.3% vs 7.1%; P = .08), and dizziness (15.1% vs 11.0%; P = .03); all events were grade 1 and lessened after the first month • Serious adverse event and laboratory adverse event rates were similar between the study groups • Significant decline in bone mineral density in the FTC/TDF group vs the placebo group |

| Bangkok Tenofovir Study190 (Thailand) | 2413 injection drug users | 1:1 randomization to TDF or placebo | TDF: 48.9% (95% CI, 9.6%−72.2%) | Not available | Not available | • Nausea more common in the tenofovir group vs the placebo group (8% vs 5%; P = .02). • Similar frequency of death, serious adverse events, and grade 3 or 4 laboratory results between the study groups |

| iPrEx187 (Brazil, Ecuador, Peru,South Africa, Thailand,United States) | 2499 MSM and transgender women | 1:1 randomization to daily oralFTC/TDF or placebo | FTC/TDF: 44% (95% CI, 15%−63%) | 51% | 92% in subjects with detectable tenofovir or emtricitabine levels;99% if tenofovir concentrations were commensurate with daily dosing | • Similar rates of serious adverse events between the study groups • Nausea more frequent during the first 4 weeks in the FTC/TDF group vs the placebo group (2% vs <1%; P < .004) • Creatinine elevations (any grade) 2% in the FTC/TDF group vs 1% in the placebo group (P = .08); majority of the events grade 1 |

| FEM-PrEP193 (Kenya, South Africa,Tanzania) | 2120 women | 1:1 randomization to dailyoral FTC/TDF orplacebo | FTC/TDF: 6% (NS); No statisticallysignificant reduction in HIVincidence | 35%−38% at a single visit, 26% at 2consecutive visits surrounding the infection period | PrEP use too low to evaluate efficacy | • TDF/FTC group had significantly higher rates than the placebo group of nausea (4.9% vs 3.1%; P = .04), vomiting (3,6% vs 1,2%; P < 0,01), or elevated alanine aminotransferase levels (11.4% vs 8.6%; P = .03) |

| VOICE194 (South Africa, Uganda,Zimbabwe) | 3019 women (plus 2010 womenreceiving tenofovir or placebo gel) | 1:1:1 randomization to daily oralFTC/TDF, oral TDF, or placebo | TDF: HR = 1.49 (P = .07)FTC/TDF: HR = 1.04 (NS) | ≤30% of samples; ≥50% of womennever had detectable tenofovir in any sample | PrEP use too low to evaluate efficacy | • Similar frequencies of serious and laboratory adverse events compared with placebo • No differences in confirmed phosphorus, transaminase, or urine protein/glucose level abnormalities |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FEM-PrEP, Preexposure Prophylaxis Trial for HIV Prevention among African Women; FTC, emtricitabine; HR, hazard ratio; iPrEx, Chemoprophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Men; MSM, men who have sex with men; NS, not statistically significant; PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; VOICE, Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic.

The key determinant of PrEP efficacy is medication adherence. Detection of TDF in plasma has been associated with reduction in HIV acquisition by approximately 90% among MSM and heterosexual adults.187–189 TDF detection in peripheral blood mononuclear cells commensurate with daily use was associated with an estimated 99% reduction in HIV risk (95% confidence interval, 96% to >99%).192 In contrast, no efficacy was discerned in 2 trials in which TDF was generally detected in less than 30% of female participants.193,194

The clinical trial findings highlight important considerations for PrEP implementation, including the development of drug resistance among participants experiencing acute retroviral infection at enrollment, underscoring the need to rule out acute infection prior to starting PrEP. TDF/FTC drug resistance was not observed187–189 or was rare193 in infections that developed after starting PrEP.187–190,193,194 Importantly, trial participants who received regular risk assessment and counseling did not exhibit an increase in risk behaviors.187–189 Observational cohort studies of persons receiving open-label PrEP are under way and should provide important information about risk compensation now that PrEP efficacy is known.

Despite these encouraging results, unanswered questions remain. Although daily oral FTC/TDF is the only PrEP regimen that is FDA-approved, oral TDF alone is effective and does not confer a risk of resistance to FTC.188,189 New CDC PrEP guidelines suggest the potential for “off-label” use of TDF alone in discordant couples and PWID based on trial data.191 Non-daily use of oral FTC/TDF was efficacious in nonhuman primates but has not been fully evaluated in humans.195 Daily PrEP use has advantages over nondaily dosing, including achievement of consistently higher levels of drug, greater tolerance of occasional missed doses, and establishment of a pill-taking routine.196 Although oral FTC/TDF is active against HBV, there is a risk of hepatitis flare if active agents are stopped, especially in persons with cirrhosis. Thus, hepatitis B virus (HBV)-uninfected persons should ideally begin vaccination prior to PrEP initiation.

Other antiretroviral drugs are theoretically well suited for PrEP, and long-acting preparations or sustained delivery systems administered parenterally or topically (eg, in a vaginal ring) may address the challenge of daily adherence. The efficacy of directly applied topical agents was supported by the results of the CAPRISA (Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa) 004 trial, which showed benefit from use of vaginal 1% tenofovir gel before and after sex.197 However, daily use of this regimen was not successful in the VOICE (Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic) trial, likely due to low rates of adherence to the product.194 A major challenge is to identify research and regulatory pathways for evaluating PrEP regimens. A surrogate marker for prophylactic efficacy is not yet available, although drug concentrations and tissue culture systems to assess viral replication appear promising.

Economic evaluations generally suggest that PrEP could be cost-effective in the United States but only if used among MSM at highest risk (annual incidences > 2%).198,199 Shorter durations of use, improved adherence and efficacy, and decreased drug costs would enhance the economic attractiveness of PrEP for MSM. Even so, studies generally indicate that although cost effective, the financial burden of a PrEP program could be huge. For example, PrEP use among high-risk MSM for 20-year duration could lead to an incremental increase in US health care costs of up to $75 billion.199 For recommendations regarding PrEP, see Box 1.

Postexposure Prophylaxis

Nonhuman primate models suggest that antiretroviral PEP is highly effective in preventing infection after retroviral challenge.200 Although RCTs evaluating PEP efficacy have not been feasible, a retrospective case control study of health care workers found that those who used zidovudine after an occupational exposure were 81% less likely to become HIV-infected than those who did not.201 The CDC subsequently developed guidelines for use of PEP in occupational202 and nonoccupational203 (NPEP) settings. PEP is generally safe, and its use was associated with decreased HIV acquisition in a study comparing MSM in Brazil who used PEP compared with those who did not.204 However, studies among MSM in America and Australia205 have suggested that some individuals may not accurately estimate their risk, leading to HIV acquisition despite availability of PEP. Given the challenge of obtaining PEP quickly and because animal studies suggest greater protection if PEP is administered prior to retroviral challenge, individuals at repeated risk for HIV acquisition may benefit from PrEP.

NPEP should only be administered to individuals who have had mucosal contact with infected blood or genital secretions or to health care workers who have needle stick exposures to HIV-infected source patients.206 Clinicians should determine whether a given exposure could result in HIV transmission and whether the source partner was HIV-infected or of unknown serostatus but at high risk of being infected. If the source is known to be HIV-infected, ascertainment of specific ART use and HIV drug resistance in the index case should inform selection of ART for PEP. PEP should include 3 medications that are least likely to be affected by drug resistance.

The US Public Health Service currently recommends initiation of a 3-drug regimen for occupational PEP202 and it is reasonable to apply this to sexual and parenteral exposures. PEP should be initiated as soon as possible, not more than 72 hours after a high-risk exposure.202,207 Animal studies support the use of PEP for a duration of 28 days.207

The updated guidelines for PEP recommend FTC/TDF and raltegravir as the initial regimen.202 TDF-based PEP regimens are better tolerated than those containing zidovudine.208,209 A recent study of FTC/TDF and raltegravir as PEP found that the most common adverse effects included nausea or vomiting (27%), diarrhea (21%), and headache (15%).209 When choosing PEP regimens, tolerability must be considered in order to ensure regimen adherence.210 However, with access to newer antiretroviral drugs that are better tolerated, and with increased potential resistance in the community, adding a third drug is reasonable. The inclusion of an HIV protease inhibitor increases the likelihood of adverse effects.211

PEP provides an opportunity to engage persons who have recurring high-risk exposure and to offer appropriate risk-reduction strategies.212 These may include referrals to address patterns of sexual risk and substance use. In addition, clinicians should consider risk-based screening for concomitant STIs and the need for emergency contraception. Persons who initiate PEP should be followed for 6 months after completion of the regimen if conventional antibody testing is used and for 4 months if newer fourth-generation assays containing p24 antigen are used.202 For recommendations regarding PEP, see Box 1.

Voluntary Medical Male Circumcision

Voluntary male circumcision reduces the risk of heterosexual HIV acquisition by 53% to 60%,213–215 an effect that is durable,216 measurable at population level,217 and cost effective.218,219 The procedure also decreases transmission of genital human papilloma virus(HPV)220 and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2).221 Adult male circumcision has not been associated with direct protection of female partners222 but with wider implementation, whole populations will likely benefit.223 Observational studies in Africa involving large numbers of neonates have also found male circumcision to be safe.224,225

The WHO and UNAIDS recommend voluntary male circumcision for HIV prevention in priority countries in sub-Saharan Africa with generalized epidemics and low male circumcision prevalence. More than 1 million men have undergone this procedure as part of HIV prevention programs.226 Despite the recommendations, efforts to promote male circumcision in priority countries have had mixed results, likely due to limited health care resources and cultural attitudes toward circumcision. The need to simplify the procedure in resource-limited settings has led to development of medical devices that require minimal or no surgery, introduction of new, more efficient procedures that increase productivity by task shifting, use of diathermy227,228 for hemostasis, and use of prepackaged surgical instruments. In some countries, demand from men has been low, and changes in the delivery system alone will not achieve the levels targeted. Political leadership has been critical to expansion efforts.229

Although no trials of adult male circumcision have been conducted among MSM, some epidemiological data suggest that the procedure might be protective for MSM who engage in primarily insertive anal sex.230 For recommendations regarding male circumcision, see Box 1.

SECTION E. PREVENTION ISSUES RELEVANT TO ALL PERSONS WITH OR AT RISK FOR HIV-1 INFECTION

Screening and Treatment for Sexually Transmitted Infections

Genital STIs facilitate transmission and acquisition of new HIV infection. Among HIV-uninfected partners in serodiscordant heterosexual couples, the presence of HSV-2 seropositivity, trichomoniasis, genital ulcer disease, cervicitis, or vaginitis substantially increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition, irrespective of the infected partner’s plasma viral load.231 Early syphilis and anorectal STIs are associated with high risk for concurrent or subsequent HIV acquisition.119,232

Interventions to detect and treat STIs identify persons at highest risk for sexual acquisition and transmission of HIV and can prioritize delivery of risk-reduction interventions, especially PrEP. The CDC and the HIV Medicine Association (HIVMA) recommend routine screening for common STIs, including syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia infections, for persons at high risk for HIV acquisition, particularly MSM.15,233 A relevant sexual history should, in turn, direct STI screening toward specific anatomic sites and screening for sexual acquisition of HCV, which is associated with high-risk anal sex practices.234 Routine laboratory screening for common STIs among MSM is summarized in Box 3.

Box 3. Approach to Screening for Sexually Transmitted Infections in HIV-Infected Patients.

First Visit

All Patients

- Syphilis serologic testing

-

∘Nontreponemal test: RPR, VDRL

-

∘Treponemal test: EIA, CIA

-

∘

- Gonorrhea

-

∘Men: urine NAAT

-

∘Women: vaginal swab (preferred), cervical swab, or urine NAAT

-

∘

- Chlamydia

-

∘Men: urine NAAT

-

∘Women: vaginal swab (preferred), cervical swab, or urine NAAT (especially if sexually active and aged 25 years or younger, regardless of symptoms)

-

∘

- Herpes simplex virus type-2 (HSV-2) serologic testing

-

∘Type-specific (glycoprotein G-based) serology (consider)

-

∘

Women

Trichomoniasis: vaginal swab NAAT (preferred); culture or rapid antigen detection test of vaginal fluid

Patients Reporting Receptive Anal Sex

Gonorrhea: rectal culture or NAAT if performed at laboratory with validation

Chlamydia: NAAT if performed at laboratory with validation

Patients Reporting Receptive Oral Sex

Gonorrhea: pharyngeal culture or NAAT if performed at laboratory with validation

Subsequent Routine Visits

Annually

Repeat first-visit tests for all sexually active patients

More Frequently

Periodic screening at 3- or 6-month intervals may be appropriate depending on patient’s reported risk factors or interim detection of other STIs

- Presence of any of the following reported risk factors should prompt consideration of repeated STI screening:

-

∘Multiple partners

-

∘Anonymous partners

-

∘Interim diagnosis of new STIs

-

∘Substance use, especially methamphetamine use

-

∘Unprotected sex outside a mutually monogamous relationship

-

∘Exchange of sex for drugs or money, or sex with a partner who reports these behaviors

-

∘High prevalence of STIs in the affected patient population

-

∘Life changes such as dissolution of a relationship that might promote adoption of high-risk sexual behaviors

-

∘

EIA indicates enzyme immunoassay; CIA, chemiluminescent immunoassay; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; RPR, rapid plasma reagin; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

For people living with HIV, sexual health, including prevention and detection of STIs, has become an important component of primary care.233 Recent trends indicate a rise in syphilis and gonorrhea among some HIV-infected persons, particularly MSM, and incident hepatitis C is increasing in this group as well.122,235–238 Despite this, routine screening for STIs in the HIV care setting is low.239 Behavioral assessments should direct appropriate screening for common STIs, including syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, at exposed anatomic sites (pharynx, rectum, and urethra).15 Because many syphilis cases are latent (positive serology in the absence of clinical signs), serologic screening is crucial. Finally, the quadrivalent HPV vaccine is safe and immunogenic in HIV-infected persons and should be offered routinely.240–242 For recommendations regarding STI screening and prevention, see Box 3.

Reproductive Health Care: Hormonal Contraception

Unintended pregnancy is a considerable burden for many women and their families, and access to safe, effective, and acceptable contraception is critical. For reproductive-aged women living with HIV, it is especially important as a means to plan pregnancy with intent to prevent vertical HIV-1 transmission and ensure maternal health. Hormonal contraception (HC) use does not affect HIV disease progression among HIV-infected women or the likelihood of HIV transmission to male partners, nor is there an increase in the recognized adverse effects of HC use in women with HIV relative to those without HIV.243,244

Some observational studies have raised concern about a potentially increased risk of HIV acquisition among users of specific HC methods, primarily depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), but results overall are inconsistent and study quality varies greatly.245 In studies that reported a close association, the relative risk was generally in the 1.5 to 2 range. A recent modeling analysis concluded that unless the true effect size approaches more than double the risk, it is unlikely that reductions in injectable HC could result in a public health benefit, except possibly in those countries in southern Africa with the largest HIV epidemics.246 A systematic review recently summarized available analyses of various methods of HC in terms of the risk of HIV acquisition.245 The authors concluded that data do not suggest that HC pills are associated with an increased risk of HIV acquisition. For injectable HC, no data suggest a close association between norethisteroneenanthate (NET-EN) and HIV acquisition, although data are limited.247 Some observational data raise concern about a potential association between use of DMPA and risk of HIV acquisition. There are almost no data on whether methods such as contraceptive implants, patches, rings, or hormonal intrauterine devices (IUDs) may impact risk of HIV acquisition.

During a 2012 WHO technical consultation, experts reviewed all available biological, epidemiological, and modeling data and recommended that the WHO continue to suggest no restriction on use of any HC method; however, they noted that for women at high risk of HIV infection, condom use and other HIV preventive measures should be strongly emphasized for those using progestogen-only injectable contraception.248 The CDC subsequently updated its medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use to reflect this stance for women in the United States.249 For recommendations regarding hormonal contraception, see Box 1.

CONCLUSION

After more than 30 years, we are at a potential turning point in the control of the global HIV epidemic. With enhanced access to effective ART and durable viral suppression, nearly all persons living with HIV could be rendered noninfectious. Those without HIV but at risk for infection can access prevention interventions ranging from ART-based PrEP to voluntary medical male circumcision. These biomedical interventions can be productively complemented by appropriate behavioral and structural interventions and support services. Clinicians are crucial in implementing these interventions, and should use evidence-based HIV prevention tools.

Supplementary Material

Box 2. Strength of Recommendation and Quality of Evidence Rating Scale.

| Category, Grade | Definition |

|---|---|

| Strength of recommendation | |

| A | Strong support for the recommendation |

| B | Moderate support for the recommendation |

| C | Limited support for the recommendation |

| Quality of evidence | |

| Ia | Evidence from 1 or more randomized controlled clinical trials published in the peer-reviewed literature |

| Ib | Evidence from 1 or more randomized controlled clinical trials presented in abstract form at peer-reviewed scientific meetings |

| IIa | Evidence from nonrandomized clinical trials or cohort or case-control studies published in the peer-reviewed literature |

| IIb | Evidence from nonrandomized clinical trials or cohort or case-control studies presented in abstract form at peer-reviewed scientific meetings |

| III | Recommendation based on the panel’s analysis of the accumulated available evidence |

Adapted from the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination3

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT/FUNDING/SUPPORT

This work is supported and funded by the IAS-USA, a mission-based, nonmembership, 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization. The IAS−USA appointed members to the IAS−USA HIV Prevention Recommendations Panel to develop the recommendations and provided staff support. In the last 5 years, IAS−USA has received commercial support (grants) for selected continuing medical education (CME) activities that are pooled (ie, no single company supports any single effort) from Abbott Laboratories, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Therapeutics, Merck & Co, Mylan, Pfizer, Salix Pharmaceuticals, Tibotec Therapeutics, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and ViiV Healthcare. The designation of selected CME activities refers to the IAS−USA structure of accepting commercial support only if there are enough companies with competing products to meet the criteria for independence and only on programs that are appropriate for support by commercial sources (eg, recommendations are not supported by industry grants). No private sector funding was used to support the effort. Panel members are not compensated for participation in the effort.

ROLE OF THE SPONSOR

The IAS–USA determined the need for updated recommendations, selected the Panel members based on expertise in biomedical and behavioral HIV care and research, and provided administrative oversight and financial support. The Panel itself is responsible for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript.

Design and conduct of the study: Dr Marrazzo, Dr del Rio, and Dr Holtgrave

Collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data: Dr Marrazzo, Dr del Rio, Dr Holtgrave, Dr Cohen, Dr Mayer, Dr Montaner, Dr Kalichman, Dr Wheeler, Dr Grant, Dr Grinsztejn, Dr Kumarasamy, Dr Shoptaw, Dr Walensky; Dr Dabis; Dr Sugarman, and Dr Benson

Preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript: Dr Marrazzo, Dr del Rio, Dr Holtgrave, Dr Cohen, Dr Mayer, Dr Montaner, Dr Kalichman, Dr Wheeler, Dr Grant, Dr Grinsztejn, Dr Kumarasamy, Dr Shoptaw, Dr Walensky; Dr Dabis; Dr Sugarman, and Dr Benson

Decision to submit the manuscript for publication: Dr Marrazzo, Dr del Rio, and Dr Holtgrave

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Disclosure information represents the previous 3 years (updated May 20, 2014).

Dr Marrazzo has served as a consultant to Merck and Astra-Zeneca; Dr del Rio has no conflicts to disclose; Dr Holtgrave’s institution, The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, has received research funds from Johnson and Johnson and Female Health Company; Dr Cohen has served as a consultant to Janssen Global Services and Roche Molecular Systems, Inc; Dr Mayer’s institution, Fenway Health, has received research grants from Gilead Sciences and Merck; Dr Montaner’s institution, BC-Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS at Providence Health Care and the University of British Columbia, has received research grants from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, and ViiV Healthcare; Dr Kalichman has no conflicts to disclose; Dr Wheeler has no conflicts to disclose; Dr Grant has served as a consultant to Siemens Healthcare and ViiV Healthcare, and his institution, the University of California San Francisco, has received support from Gilead Sciences for travel, accommodation, and meeting expenses; Dr Grinsztejn has no conflicts to disclose; Dr Kumarasamy has no conflicts to disclose; Dr Shoptaw has no conflicts to disclose; Dr Walensky has no conflicts to disclose; Dr Dabis has no conflicts to disclose; Dr Sugarman has no conflicts to disclose; Dr Benson’s spouse has received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc, and has served as a scientific advisor to CytoDyn and Merck & Co, Inc, as a scientific advisory board member for Gilead Sciences, Inc, GlobeImmune, Inc, and Monogram Biosciences, and as a member of data monitoring committees for Axio and Gilead Sciences, Inc. He has stock in GlobeImmune, Inc.

Dr Marrazzo had full access to all the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Contributor Information

Jeanne M. Marrazzo, University of Washington.

Carlos del Rio, Emory University.

David R. Holtgrave, The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Myron S. Cohen, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Seth C. Kalichman, University of Connecticut.

Kenneth H. Mayer, Harvard Medical School.

Julio S. G. Montaner, University of British Columbia.

Darrell P. Wheeler, Loyola University Chicago.

Robert M. Grant, University of California San Francisco.

Beatriz Grinsztejn, Evandro Chagas Clinical Research Institute (IPEC)–FIOCRUZ.

N. Kumarasamy, YR Gaitonde Centre for AIDS Research and Education.

Steven J. Shoptaw, University of California Los Angeles.

Rochelle P. Walensky, Massachusetts General Hospital.

Francois Dabis, Université Bordeaux Segalen.

Jeremy Sugarman, The Johns Hopkins University.

Constance A. Benson, University of California San Diego.

Reference

- 1.Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e17502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fauci AS, Folkers GK, Dieffenbach CW. HIV-AIDS: much accomplished, much to do. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(11):1104–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. The periodic health examination. Can Med Assoc J. 1979;121(9):1193–1254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Monitoring Selected National HIV Prevention and Care Objectives by Using HIV Surveillance Data-United States and 6 Dependent Areas-2011. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/2011_Monitoring_HIV_Indicators_HSSR_FINAL.pdf. Accessed on May 23, 2014

- 5.Hall HI, Holtgrave DR, Tang T, Rhodes P. HIV transmission in the United States: considerations of viral load, risk behavior, and health disparities. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1632–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]