Abstract

Background:

Surgery is a major physiologic stress comparable to intense exercise. Diminished cardiopulmonary reserve is a major predictor of poor outcomes. Current preoperative workup focuses mainly on identifying risk factors, however little attention is devoted to improving cardiopulmonary reserve beyond counseling. We propose that patients could be optimized for a “surgical marathon” similar to the preparation of an athlete.

Study Design:

The Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program (MSHOP) is a formal prehabilitation program that engages patients in four activities before surgery: physical activity, pulmonary rehabilitation, nutritional optimization, and stress reduction. We prospectively collected demographic, intraoperative (first hour), and postoperative data for patients enrolled in MSHOP undergoing major abdominal surgery. Statistical analysis was performed using 2:1 propensity score matching to compare the MSHOP group (N=40) to emergency (N=40) and elective, non-MSHOP (N=76) patients.

Results:

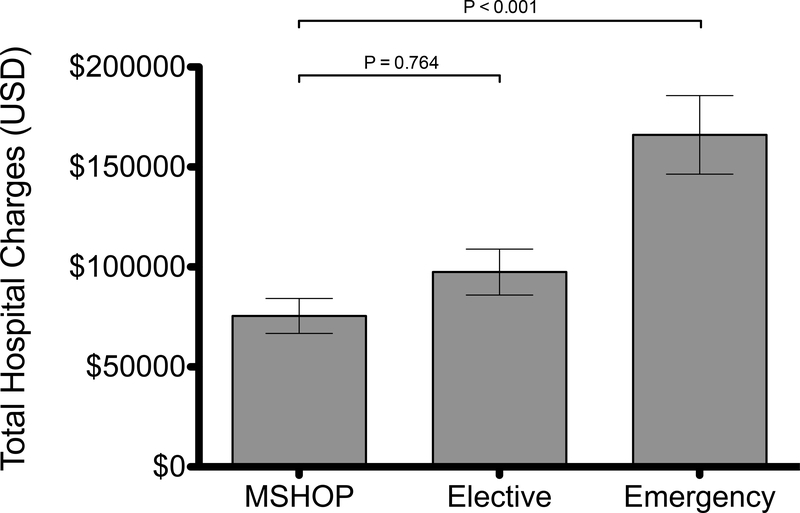

Overall, 70% of MSHOP patients complied with the program. Age, gender, ASA classification, and BMI did not differ significantly between groups. One hour intraoperatively, MSHOP patients showed improved systolic and diastolic blood pressures and lower heart rate (Figure). There was a significant reduction in Clavien-Dindo class 3–4 complications in the MSHOP group (30%) compared to the non-prehabilitation (38%) and emergency (48%) groups (p=0.05). This translated to total hospital charges averaging $75,494 for the MSHOP group, $97,440 for the non-prehabilitation group, and $166,085 for the emergency group (p < 0.001).

Conclusion:

Patients undergoing prehabilitation prior to colectomy showed positive physiologic effects and experienced fewer complications. The average savings of $21,946 per patient represents a significant cost offset for a prehabilitation program, and should be considered for all patients undergoing surgery.

Precis

For frail patients undergoing major abdominal surgery, participation in a formal prehabilitation program improves their physiologic response to surgery, reduces postoperative complications, and prevents significant increases in cost compared to non-frail patients who do not participate in prehabilitation.

Introduction

Surgery is a significant physiologic stress comparable to intense exercise.1 It causes increased metabolism and catabolism, increased oxygen uptake, stress hormone production, and release of inflammatory cytokines.2,3 While this stressor impacts all patients undergoing surgery, frail patients with poor cardiopulmonary reserve and overall physical deconditioning do worse in response to this major stressor. Frail patients are less able to compensate for these increased metabolic demands, resulting in physiologic dysregulation.4 Consequently, frail patients have an increased rate of postoperative complications.5 Frailty has also been shown to be associated with increased mortality, morbidity, and poor outcomes overall.6,7 This results in increased hospital costs and greater resource utilization for frail patients compared to non-frail patients.8,9 Prehabilitation – or “training for surgery” – can improve a patient’s functional status prior to this major stressor, and therefore has the potential to improve outcomes.10

To date, data are mixed on the effects of prehabilitation. It’s generally accepted that prehabilitation before surgery results in a more rapid return to baseline functional capacity after surgery.11–13 Prehabilitation has also been shown to reduce postoperative complications, but studies that have investigated mortality outcomes have had equivocal results.14 While there has been a large focus on postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing prehabilitation, few studies have addressed the specific physiologic effects that prehabilitation has on patients undergoing surgery. Moreover, less is known about the potential cost savings associated with prehabilitation. Since prehabilitation is first and foremost a form of physiologic conditioning for patients about to undergo the “marathon” of surgery, further study is needed of the physiologic changes that result.

Within this context, we sought to analyze the physiologic effects and outcomes of prehabilitation on patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Our goal was to compare these differences in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery after participating in a formal prehabilitation program. These patients were compared to a similar cohort of patients who underwent abdominal surgery without participating in prehabilitation, as well as a cohort of patients who underwent emergent abdominal surgery. Understanding the physiologic, clinical, and financial effects of surgical prehabilitation may further assist clinicians in targeting high-risk patients who may benefit from this type of intervention.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. A retrospective chart review was conducted to identify adult patients who underwent major abdominal surgery between 2012–2017 at a single academic health system. Procedures primarily included open and laparoscopic colectomy, hemicolectomy, and ostomy takedown. Patients were included if they participated in our institution’s formalized surgical prehabilitation program prior to their surgery. We then selected a random sample of patients who underwent elective and emergency abdominal surgery during the same time period for comparison via propensity score matching.

Propensity Score Matching

Patients undergoing prehabilitation were propensity score matched to patients undergoing elective abdominal surgery and patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery. A two-to-one propensity score match was performed for prehabilitation and elective surgery patients. A one-to-one propensity score match performed for patients undergoing emergency surgery. Patients were matched on age, sex, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification, cancer diagnosis, and smoking status, as well as surgical procedure and characteristics related to their procedure (operative time, laparoscopic vs. open procedure).

Frailty was compared between groups by calculating total psoas muscle size for each patient, a method described elsewhere. In brief, cross-sectional imaging was used to measure the total psoas muscle size in each patient with available imaging. The areas of the left and right psoas muscles were outlined at the inferior border of the fourth lumbar vertebral body and summed to compute the total psoas muscle area (cm2).15,16 This was then normalized across patients by calculating a frailty index for each patient as total psoas muscle area (cm2) / total body surface area (m2).17,18 Total body surface area (TBSA) was computed using the Du Bois formula as TBSA = ((weight (kg)0.425 × height (m)0.725) × 0.007184).19 Sarcopenia was defined as a frailty index less than the median for all patients. Values were calculated independently between males and females, then for each group using gender as a covariate.

MSHOP

The Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program (MSHOP) is a structured prehabilitation program available to select patients prior to surgery at our institution.20,21 It is offered to patients undergoing major abdominal or thoracic surgery with at least two weeks between enrollment and surgery. There are no discrete inclusion criteria, and referral to the program is made at the surgeon’s discretion. MSHOP engages patients in four domains: walking (patients receive a pedometer to track steps); breathing (patients receive an incentive spirometer); nutrition and stress management; and smoking cessation as appropriate. Patients receive a DVD and brochure with instructions and resources for each domain, as well as a way to log their participation. Lastly, during their involvement in the program, they receive emails, phone messages, and text messaged-based reminders to continue.

Variables and Outcomes

Demographic data included age, sex, BMI, ASA classification, cancer diagnosis, and smoking status. Procedure characteristics included length of surgery, laparoscopic versus open surgery, estimated blood loss, use of blood products, and postoperative admission to an intensive care unit (ICU). Since prehabilitation has been shown to improve physiologic reserve during a major stressor such as surgery, intraoperative physiologic data were collected.22 Physiologic variables included systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and heart rate (HR). These variables were recorded at induction of anesthesia and again at one hour into surgery. The difference between these two points was calculated to represent physiologic variability during this time. Within this hour, SBP, DBP, and HR were recorded at five-minute intervals. Physiologic variability was further calculated by measuring a continuous line between these points for SBP, DBP, and HR. We also calculated the number of times there was a >20-point change over a five-minute interval for SBP and DBP in mmHg, and for HR in beats per minute.

Complications were represented on the Clavien-Dindo Classification scale from I-V.23 They were grouped as none, minor complications (class I-II), major complications (class III-IV), and death (class V).

The primary financial outcomes included hospital charges, professional charges, and total charges for each patient. All financial data was obtained from billing records at our institution. The cost of the MSHOP program is not included in hospital charges, however we have previously reported that the program costs roughly $100 per patient.

Statistical Analysis

All continuous primary outcomes variables were compared between the three groups using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Where a significant difference was found, Bonferroni post-hoc analysis was conducted to specifically compare the prehabilitation group to the elective surgery group. For analysis of hospital charges, linear regression was conducted to control for open versus laparoscopic surgery and length of stay. Categorical variables were compared between groups using Chi-squared test. Two-sided significance tests were used for all analyses and significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. All analyses were conducted using Stata 15 (StataCorp).

Results

Demographics

After propensity score matching, the following groups were included for analysis: 40 patients enrolled in MSHOP who underwent abdominal surgery, 76 patients who underwent elective abdominal surgery, and 40 patients who underwent emergency abdominal surgery. Demographic data for the three groups is presented in Table 1. There was a significant difference in ASA classification between groups, with an increased frequency of ASA IV-V patients in the emergency surgery group. There was no significant difference in the incidence of smoking between groups (P=0.142), however 3 of 4 smokers in the prehabilitation group reported cessation prior to surgery. There was a higher incidence of cancer in the elective surgery group. Lastly, there was a significant difference in the use of laparoscopy between patients in the MSHOP, elective, and emergency groups (70% vs. 53% vs. 3%, P<0.001). Comparison of the MSHOP and elective groups revealed a non-significant difference between laparoscopic and open surgery (P=0.08). There was no difference in operative time between groups.

Table 1.

Demographic and Procedural Characteristics

| Demographic or characteristic | MSHOP (N=40) | Elective (N=76) | Emergency (N=40) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 59.3 (10.8) | 58.3 (13.2) | 54.5 (17.8) | 0.252 |

| Female sex, % | 48 | 50 | 45 | 0.874 |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.2 (7.7) | 29.9 (7.2) | 28.5 (9.6) | 0.601 |

| ASA classification, % | ||||

| I | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.005 |

| II - III | 98 | 96 | 77 | |

| IV - V | 3 | 4 | 20 | |

| Current smoker, % | 10 | 26 | 18 | 0.142 |

| Cancer diagnosis, % | 35 | 53 | 27 | 0.02 |

| Laparoscopic procedure, % | 70 | 53 | 3 | <0.001 |

| Operative time, min, mean (SD) | 241.4 (114.2) | 226.7 (98.4) | 220.1 (87.1) | 0.614 |

No significant difference between MSHOP and elective groups.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; MSHOP, Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program.

A total of 19 different surgeons performed the operations. There was no significant difference in surgeon distribution between the MSHOP and elective groups (P=0.465) or between the MSHOP and emergency groups (P=0.175). MSHOP referrals were made by 12 of the 19 surgeons. A total of 46 anesthesiologists provided anesthesia for the operations. There was no significant difference in anesthesiologist distribution between the MSHOP and elective groups (P=0.334) or between the MSHOP and emergency groups (P=0.208).

Cross-sectional imaging was available for 32 patients in the MSHOP group, 76 patients in the elective group, and 38 patients in the emergency group (Table 2). Total psoas muscle area was significantly different between groups for males (P=0.008) but not for females (P=0.431). However, after normalizing for TBSA, there was a significant difference in frailty index between groups for both males and females (P=0.002, P=0.045, respectively). Gender-adjusted total psoas muscle size and frailty index was significantly different between groups (P=0.004). Post-hoc analysis revealed that patients enrolled in MSHOP had significantly smaller psoas muscle size compared to non-MSHOP patients undergoing elective surgery (21.98±7.75 vs. 25.27±8.38, P=0.002). Overall, sarcopenia was more common in patients in the MSHOP group compared to the elective surgery and emergency surgery groups (73% vs. 42% vs. 45%, P=0.01).

Table 2.

Frailty Data Compared between Groups

| Group | MSHOP | Elective | Emergency | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | (N=16) | (N=38) | (N=20) | |

| Total psoas muscle area, cm2, mean (SD) | 24.90 (7.99)* | 31.43 (5.93) | 29.30 (7.27) | 0.008 |

| Frailty index, mean (SD) | 11.64 (4.57)* | 14.67 (1.94) | 14.91 (3.34) | 0.002 |

| Sarcopenia, % | 75 | 37 | 45 | 0.036 |

| Female | (N=16) | (N=38) | (N=18) | |

| Total psoas muscle area, cm2, mean (SD) | 17.29 (5.42) | 19.10 (5.37) | 17.65 (5.06) | 0.431 |

| Frailty index, mean (SD) | 8.57 (3.05)* | 10.65 (2.82) | 10.34 (2.66) | 0.045 |

| Sarcopenia, % | 65 | 45 | 44 | 0.350 |

| All patients | (N=32) | (N=76) | (N=38) | |

| Sex-adjusted total psoas muscle area, cm2, mean (SD) | 21.09 (7.75)* | 25.27 (8.38) | 23.78 (8.58) | 0.006 |

| Sex-adjusted frailty index, mean (SD) | 10.11 (4.13)* | 12.66 (3.14) | 12.75 (3.79) | <0.001 |

| Sarcopenia, % | 73 | 42 | 45 | 0.010 |

Significant difference between MSHOP and elective groups (p<0.05).

MSHOP, Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program.

Physiologic

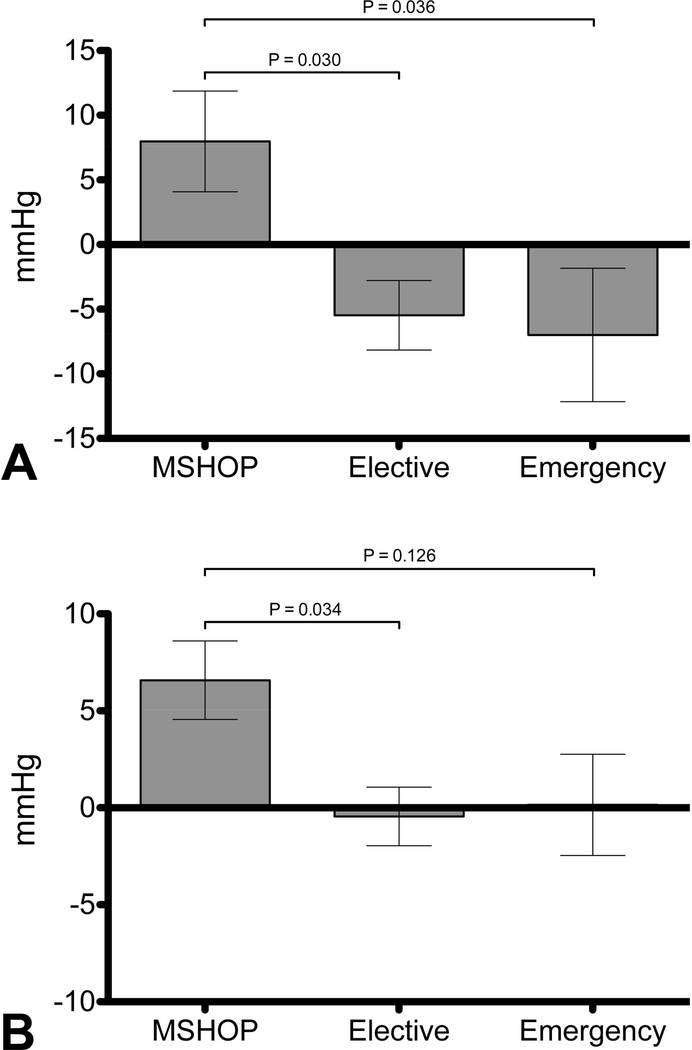

There were significant differences in physiologic variables between the three groups. At the start of the operation, MSHOP patients had significantly lower SBP than non-MSHOP and emergency patients (Table 3). At one hour into the operation, MSHOP patients had an increase in SBP compared to non-MSHOP and emergency groups, both of which had a decrease in SBP at one hour (Figure 1a). There was no significant difference in diastolic blood pressure between groups at the start of the operation. At one hour, MSHOP patients had a significant increase in diastolic blood pressure compared to the other groups (Figure 1b). MAP was significantly lower in MSHOP patients at the start of the operation. At one hour, MSHOP patients had a significant increase in MAP compared to both elective and emergency groups which had a decrease in MAP at one hour.

Table 3.

Physiologic Characteristics and Variability

| Characteristic | MSHOP (N=40) | Elective (N=76) | Emergency (N=40) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP, mmHg, mean (SD) | ||||

| Start | 106 (19)* | 121 (21) | 123 (28) | 0.001 |

| 1-hour | 114 (20) | 116 (17) | 120 (25) | 0.373 |

| Change | 8 (25)† | −6 (23) | −7 (33) | 0.016 |

| DBP, mmHg, mean (SD) | ||||

| Start | 61 (11) | 66 (13) | 65 (16) | 0.146 |

| 1-hour | 68 (11) | 66 (12) | 65 (15) | 0.613 |

| Change | 7 (13)† | 0 (13) | 0 (17) | 0.031 |

| Mean arterial pressure, mmHg, mean (SD) | ||||

| Start | 76 (13)† | 85 (15) | 84 (18) | 0.014 |

| 1-hour | 83 (13) | 82 (13) | 83 (16) | 0.918 |

| Change | 7 (16)† | −2 (16) | −1 (21) | 0.024 |

| HR, beats per min, mean (SD) | ||||

| Start | 76 (14) | 79 (15) | 86 (22) | 0.015 |

| 1-hour | 74 (14) | 75 (12) | 84 (20) | 0.008 |

| Change | −2 (12) | −4 (14) | −3 (23) | 0.803 |

| Length, mean (SD) | ||||

| SBP | 3.56 (1.10) | 3.20 (0.98) | 2.83 (0.98) | 0.008 |

| DBP | 2.18 (0.53) | 2.13 (0.51) | 1.92 (0.64) | 0.081 |

| HR | 1.82 (0.68) | 1.71 (0.55) | 1.73 (0.82) | 0.703 |

| Frequency change, >20 mmHg, mean (SD) | ||||

| SBP | 9.26 (2.99)* | 7.00 (2.75) | 7.56 (3.91) | 0.002 |

| DBP | 5.74 (2.97) | 4.97 (2.43) | 3.79 (2.69) | 0.006 |

| HR | 3.47 (2.93) | 2.97 (3.87) | 2.59 (3.24) | 0.430 |

Significant difference between MSHOP and elective groups (p<0.001).

Significant difference between MSHOP and elective groups (p<0.05).

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; MSHOP, Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Figure 1.

(A) Change in systolic blood pressure (SBP) and (B) diastolic blood pressure (DBP) after the first hour of surgery. Patients who participated in the Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program (MSHOP) had significantly increased SBP and DBP 1 hour into surgery compared to both elective and emergency surgery patients.

There was a significant difference in heart rate between groups at the start of the operation (P=0.015). However, post hoc analysis revealed that the difference between MSHOP and elective groups was not significant (P=0.978).

Physiologic variability during the first hour of surgery was different between groups (Table 3). The length of a continuous line charting SBP was significantly different between groups (P=0.008), with post-hoc analysis revealing that this was greater in the MSHOP group compared to the emergency group (P=0.005). Compared to both elective and emergency groups, patients in the MSHOP group had more variability in systolic and diastolic blood pressure (P=0.002, P=0.006, respectively) as measured by the number of 5-minute variations > 20 points.

Outcomes and Complications

There was no significant difference in length of hospital stay between the MSHOP and elective groups (P=1.0). However, the emergency group had a significantly longer length of stay by roughly 4 days compared to the other groups (P=0.003). Rate of hospital readmission within 30 days was similar between groups (P=0.737).

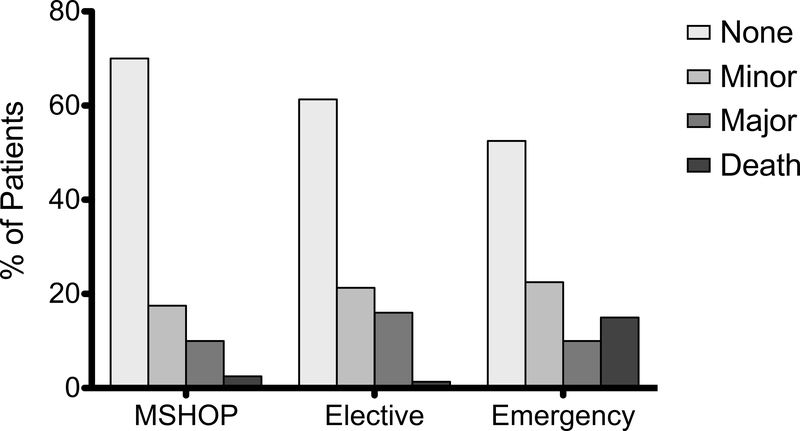

MSHOP patients were less likely to be admitted to an ICU following surgery and less likely to require transfusion of blood products during surgery (Table 4). MSHOP patients experienced fewer complications compared to patients undergoing elective and emergency surgery (P=0.05) (Table 4). As shown in the table, MSHOP patients had the highest rate of no complication (70% vs. 61% vs. 53%) and the lowest rates of minor complication (18% vs. 21% vs. 23%) (Figure 2). Rate of major complication was lower in MSHOP patients compared to non-MSHOP elective patients (10% vs. 16%), but not compared to emergency patients (10% vs. 10%). Deaths were most common in patients undergoing emergency surgery (15%).

Table 4.

Clinical Outcomes and Cost

| Outcome | MSHOP (N=40) | Elective (N=76) | Emergency (N=40) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission, % | 0 | 2.70 | 47.50 | <0.001 |

| Blood product administration, % | 0 | 1.30 | 15.00 | 0.001 |

| Length of stay, d, mean (SD) | 7.6 (5.5) | 7.6 (7.2) | 11.9 (6.8) | 0.003 |

| Readmission, % | 23 | 18 | 22 | 0.737 |

| Complication, % | ||||

| None | 70.0 | 61.3 | 52.5 | 0.050 |

| Minor | 17.5 | 21.3 | 22.5 | |

| Major | 10.0 | 16.0 | 10.0 | |

| Death | 2.5 | 1.3 | 15.0 | |

| Mortality, % | 2.5 | 1.3 | 15.0 | 0.005 |

| Total charge, $, mean (SD) | 75,493.97 (55,151.21) | 97,439.88 (100,377.06) | 166,085.44 (124,394.84) | 0.001 |

| System charge, $, mean (SD) | 67,083.97 (50,409.17) | 82,198.04 (93,538.02) | 144,858.53 (113,169.23) | <0.001 |

| Professional charge, $, mean (SD) | 11,038.12 (5,861.32) | 15,249.84 (9,238.38) | 21,226.89 (12,552.24) | <0.001 |

MSHOP, Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program.

Figure 2.

Comparison of postoperative complications between groups. MSHOP, Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program.

Financial Outcomes

Mean total hospital charges for patients enrolled in MSHOP was $75,493.97±$55,151.21, compared to $97,439.88±$100,377.06 for elective patients and $166,085.44±$124,394.84 for emergency patients (P<0.001) (Table 4). Post hoc analysis reveals that although the total charges for MSHOP patients is lower than both groups, this difference is only significant between MSHOP and emergency groups (P<0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Differences in total hospital charges between 3 groups. Total costs were significantly lower for the Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program (MSHOP) group compared to emergency surgery group, however this decreased cost was not significantly different compared to the elective surgery group.

Patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery also had increased hospital charges of $138,158.60±$125,337.06 compared to $73,171.11±$46,910.44 for patients undergoing open surgery (P<0.001). Hospital length of stay also contributed to hospital charges, with a $11,173.67±852.51 increase for every hospital day (P<0.001). Importantly, however, after controlling for both of these factors, total charges were still significantly less for the prehabilitation group compared to both elective and emergency surgery groups. Specifically, this model revealed that hospital charges for the prehabilitation group were $25,785.96±$6,417.83 less compared to the elective surgery group (P<0.001) and $65,039.31±$17,856.68 less compared to the emergency surgery group (P<0.001).

Discussion

The major finding of this study is that surgical prehabilitation may convey a variety of multifactorial benefits to patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Specifically, patients who completed prehabilitation through our institution’s MSHOP program had better physiologic characteristics during surgery, fewer complications, and may derive a moderate hospital savings compared to other patients.

These findings reinforce a number of the benefits of prehabilitation that have been demonstrated in prior studies. Frail patients are physiologically deconditioned at baseline, and therefore expected to experience more complications compared to otherwise healthy patients undergoing elective surgery. Prehabilitation has been shown to reduce this rate of complications.24 Although referral to our institution’s prehabilitation program was not based on explicit inclusion criteria, psoas muscle size analysis revealed that there was a higher incidence of frailty in patients who were referred to MSHOP. As a result, these patients should be expected to do worse. This study demonstrates that surgical prehabilitation is beneficial in that these patients do not have the inferior outcomes that they are expected to have. Moreover, patients who completed prehabilitation had superior outcomes in some cases. When they experienced complications, for example, these complications were more likely to be minor compared to both elective and emergency surgery groups. Prehabilitation patients also did not have higher rates of hospital readmission compared to the other groups. It is worth noting, however, that the readmission rate of roughly 20% across all patients is high compared to the reported average of 10–15% following colorectal surgery.25 As a quaternary referral center, it may be the case that patient complexity drives this increased readmission rate. Currently, however, our data preclude further analysis of readmission diagnosis and treatment. Future work should examine the role that prehabilitation plays in hospital readmission.

It’s well-established that frail patients have a reduced physiologic reserve, and prehabilitation can optimize this prior to surgery.26 Simple exercise prior to surgery improves lung capacity and overall cardiopulmonary function.27,28 A unique finding of the current study is that this benefit translates to improved physiologic reserve during surgery itself. Patients who have diminished physiologic reserve are less able to respond to stressors, which translates to less variability in parameters such as blood pressure and heart rate.29 For example, lower preoperative heart rate variability has been associated with greater risk of hypotension following anesthesia induction, as well as postoperative cardiac events.30,31 While patients who underwent prehabilitation did have non-significantly increased heart rate variability, they demonstrated significantly increased variability in blood pressure, with an overall increase in systolic and diastolic blood pressure an hour into surgery compared to both other groups. This suggests that the improvements in physiologic reserve resulting from prehabilitation may translate into improved ability to respond to intraoperative stressors, whereas patients who do not undergo prehabilitation are more likely to be at their “physiologic maximum” throughout surgery.

Our analysis revealed that there is a significant savings when comparing total charges between the prehabilitation group and patients undergoing emergency surgery. This is unsurprising given that emergent status imparts significant risk and increased resource utilization compared to elective surgery.32 The lack of a significant difference in charges between prehabilitation and elective patients, however, is not necessarily a negative finding. Given the finding of increased frailty in these patients, these patients should be reasonably expected to result in increased health system resource utilization, as reflected by higher charges. Therefore, this study demonstrates that at the very least, the anticipated increased expenditures are offset by participating in prehabilitation. Further study is needed to determine what drove these financial differences.

This study is not without its limitations. First, we only investigated the effects of a single institution’s prehabilitation program (MSHOP). Given the practical and logistical challenges of implementing a functional prehabilitation program, there are no doubt considerable differences in these programs between institutions. Therefore, prehabilitation at other health systems may have different effects, limiting the generalizability of our results. Another limitation is the difference in laparoscopic versus open surgery between groups. As expected, the emergency surgery group underwent almost exclusively open procedures, which likely plays a role in patient outcomes. An additional is that surgeons were at their discretion to enroll patients in MSHOP prior to surgery. This detracts from the homogeneity of the group, although this aspect may be more representative of a “real world” prehabilitation cohort since the definition of frailty is unclear. Nevertheless, this limitation was addressed by retrospectively comparing frailty data between groups to determine that there was a higher incidence of frailty in the MSHOP group. Developing a more robust prehabilitation program in the future may rely on objective prospective criteria to target patients who may derive the most benefit from prehabilitation prior to surgery. Another limitation is the lack of preoperative data regarding the effects of prehabilitation prior to surgery. The above data reflect intraoperative physiologic function after prehabilitation, however it is also important to capture the effects of prehabilitation prior to surgery (such as changes in baseline vital signs, cardiopulmonary function, and protein intake). This would be similar to reporting the incidence of smoking cessation as mentioned above.

Conclusion

Patients who complete surgical prehabilitation experience a number of benefits compared to patients who undergo elective abdominal surgery without prehabilitation as well as patients undergoing emergency abdominal surgery. These benefits include improved physiologic characteristics during surgery, reduced rate of complications, and lower charges. Further studies are needed to determine whether it is these physiologic benefits which drive the reduction in complications and financial variation.

Acknowledgments

Support: Dr Machado-Aranda receives funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI-K12–133304). The Michigan Surgical and Health Optimization Program is funded by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan.

Disclaimer: The content of this study is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wynter-Blyth V, Moorthy K. Prehabilitation: preparing patients for surgery. Bmj. 2017;358:j3702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finnerty CC, Mabvuure NT, et al. The surgically induced stress response. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37(5 Suppl):21S–29S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desborough JP. The stress response to trauma and surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85(1):109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson TN, Walston JD, Brummel NE, et al. Frailty for Surgeons: Review of a National Institute on Aging Conference on Frailty for Specialists. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221(6):1083–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snowden CP, Prentis JM, Anderson HL, et al. Submaximal cardiopulmonary exercise testing predicts complications and hospital length of stay in patients undergoing major elective surgery. Annals of surgery. 2010;251(3):535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldman LS, Carli F. From Preoperative Assessment to Preoperative Optimization of Frailty. JAMA Surg. 2018:e180213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makary MA, Segev DL, Pronovost PJ, et al. Frailty as a predictor of surgical outcomes in older patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(6):901–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson TN, Wu DS, Stiegmann GV, Moss M. Frailty predicts increased hospital and six-month healthcare cost following colorectal surgery in older adults. American journal of surgery. 2011;202(5):511–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldfarb M, Bendayan M, Rudski LG, et al. Cost of Cardiac Surgery in Frail Compared With Nonfrail Older Adults. Can J Cardiol. 2017;33(8):1020–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaughness G, Howard R, Englesbe M. Patient-centered surgical prehabilitation. American journal of surgery. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lemanu DP, Singh PP, MacCormick AD, et al. Effect of preoperative exercise on cardiorespiratory function and recovery after surgery: a systematic review. World journal of surgery. 2013;37(4):711–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gillis C, Buhler K, Bresee L, et al. Effects of Nutritional Prehabilitation, With and Without Exercise, on Outcomes of Patients Who Undergo Colorectal Surgery: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):391–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayo NE, Feldman L, Scott S, et al. Impact of preoperative change in physical function on postoperative recovery: argument supporting prehabilitation for colorectal surgery. Surgery. 2011;150(3):505–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moran J, Guinan E, McCormick P, et al. The ability of prehabilitation to influence postoperative outcome after intra-abdominal operation: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Surgery. 2016;160(5):1189–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paknikar R, Friedman J, Cron D, et al. Psoas muscle size as a frailty measure for open and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016;151(3):745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JS, He K, Harbaugh CM, et al. Frailty, core muscle size, and mortality in patients undergoing open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Journal of vascular surgery. 2011;53(4):912–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saji M, Lim DS, Ragosta M, et al. Usefulness of Psoas Muscle Area to Predict Mortality in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Am J Cardiol. 2016;118(2):251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawkins RB, Mehaffey JH, Charles EJ, et al. Psoas Muscle Size Predicts Risk-Adjusted Outcomes After Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2018;106(1):39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DuBois D, DuBois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch Intern Medicine. 1916; 17:863–71. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Englesbe MJ, Grenda DR, Sullivan JA, et al. The Michigan Surgical Home and Optimization Program is a scalable model to improve care and reduce costs. Surgery. 2017;161(6):1659–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.University of Michigan. Michigan Surgical & Health Optimization Program http://www.med.umich.edu/surgery/mshop/. Published 2013. Accessed June 16, 2018.

- 22.Carli F, Scheede-Bergdahl C. Prehabilitation to enhance perioperative care. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015;33(1):17–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Annals of surgery. 2004;240(2):205–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valkenet K, van de Port IG, Dronkers JJ, et al. The effects of preoperative exercise therapy on postoperative outcome: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2011;25(2):99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lucas DJ, Ejaz A, Bischof DA, et al. Variation in readmission by hospital after colorectal cancer surgery. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(12):1272–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carli F, Gillis C, Scheede-Bergdahl C. Promoting a culture of prehabilitation for the surgical cancer patient. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benzo R, Wigle D, Novotny P, et al. Preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation before lung cancer resection: results from two randomized studies. Lung Cancer. 2011;74(3):441–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.West MA, Loughney L, Lythgoe D, et al. Effect of prehabilitation on objectively measured physical fitness after neoadjuvant treatment in preoperative rectal cancer patients: a blinded interventional pilot study. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(2):244–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reimer P, Maca J, Szturz P, et al. Role of heart-rate variability in preoperative assessment of physiological reserves in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:1223–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Padley JR, Ben-Menachem E. Low pre-operative heart rate variability and complexity are associated with hypotension after anesthesia induction in major abdominal surgery. J Clin Monit Comput. 2018;32(2):245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laitio T, Jalonen J, Kuusela T, Scheinin H. The role of heart rate variability in risk stratification for adverse postoperative cardiac events. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2007;105(6):1548–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah AA, Haider AH, Zogg CK, et al. National estimates of predictors of outcomes for emergency general surgery. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2015;78(3):482–490; discussion 490–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]