Abstract

Angiography is the current gold standard for imaging during percutaneous coronary interventions but has significant limitations. Catheter-based intravascular imaging techniques such as intravascular ultrasound and the more recent optical coherence tomography have the potential to overcome these limitations and thus optimize clinical outcomes. In this update, we discussed the current applications of the available imaging techniques, existing evidence, continuing unmet needs, and potential areas for further research.

1. Introduction

Advances in equipment, stents, techniques, and pharmacological therapy have significantly improved short- and long-term clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) over the past few decades.1 Imaging guidance during PCI is one of the key determinants of procedural outcomes because it is an integral part of every stage of PCI including assessment of lesion severity, preprocedural planning (selection of appropriate stenting strategy, stent size, landing zones), optimization (stent expansion, malapposition, lumen gain), and management of immediate complications (dissection, thrombus, tissue prolapse, side-branch compromise). During follow-up, imaging helps in identification and management of mechanisms of stent failure (restenosis, thrombosis).2

Till date, angiography has been the imaging modality of choice during PCI despite significant limitations (Table 1).3 Furthermore, selection of stent size and length may not be optimal as angiography assesses only the lumen (luminology) and not the entire vessel wall.3 For example, with diffuse disease, the reference vessel diameter as assessed by angiography may be significantly lower than the actual vessel size. Also, plaques are not visualized unless they produce luminal narrowing, which makes it difficult to choose appropriate landing zones for stent placement.

Table 1.

Limitations of conventional angiography.

| Limitations of angiography |

|---|

|

Intravascular imaging techniques with the ability to visualize both vessel wall structures and lumen provide valuable additional information and promise to cover the shortfalls of conventional angiography.4

There are two catheter-based intravascular imaging techniques which are currently in use: intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and optical coherence tomography (OCT). IVUS uses ultrasound waves to visualize the vessel wall while the relatively newer OCT uses near-infrared light. OCT has better spatial resolution (10–15 μm) when compared with IVUS (100–150 μm) but has poorer penetration. Consequently, OCT is able to visualize superficial structures of vessel wall with much higher resolution than IVUS which can visualize the entire vessel wall albeit with poor resolution.5, 6 Two types of OCT systems are available: (1) time domain (TD) OCT (first-generation) systems, and (2) Fourier domain (FD) OCT (second-generation) systems that differ mainly with respect to the method used to calculate the electric field amplitude.5 The development of FD-OCT has enabled faster image acquisition of longer coronary segments compared with TD-OCT.5 The differences between the IVUS and OCT are enlisted in Table 2.7 The safety of both these techniques is well documented.1, 8, 9

Table 2.

Comparison: optical coherence tomography versus intravascular ultrasound.

| OCT | IVUS | |

|---|---|---|

| Frame rate (s) | 100 | 30 |

| Pullback speed (mm/s) | 20 | 0.5–1.0 |

| Lines per frame | 500 | 256 |

| Axial resolution (μm) | 12–15 | 150 |

| Scan diameter in contrast (mm) | 10 | 15–20 |

| Tissue penetration (mm) | 1.0–2.0 | 10 |

| Ease of use | ++ | ++/+++ |

| Need for contrast or dextran | Yes | No |

| Detection of lipid | +++ | +/++ |

| Detection of fibrous cap | +++ | + |

| Detection of thrombus | ++ | + |

| Detection of calcium | ++ | +++ |

| Dissection | +++ | ++ |

| Malapposition | +++ | ++ |

| Stent strut surface coverage | +++ | + |

IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

1.1. IVUS guidance for PCI

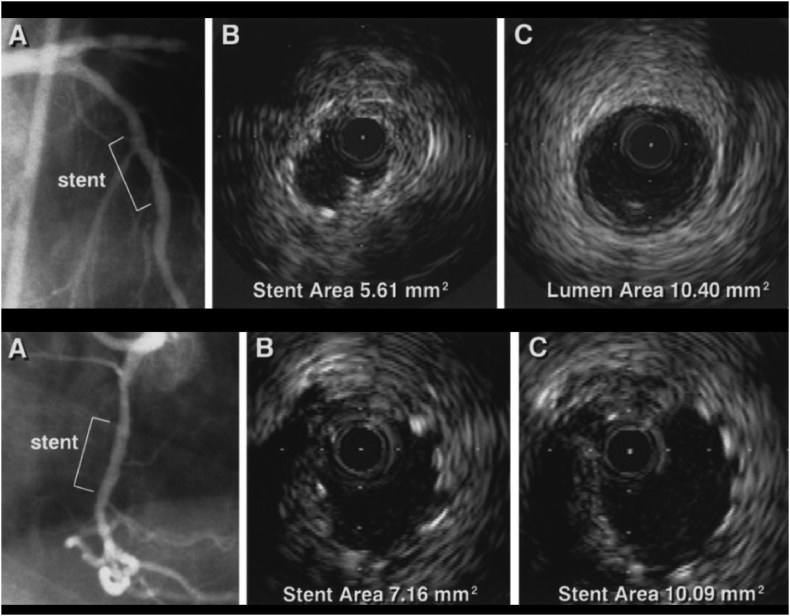

The most important predictor of adverse outcomes (thrombosis and restenosis) after stent implantation is the degree of stent expansion achieved.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 By achieving greater stent expansion, IVUS guidance has been associated with improved event-free survival compared with angiographic guidance alone (Fig. 1).4, 13, 16, 17

Fig. 1.

Top, angiographically guided stent implantation. Despite acceptable angiographic appearance (A), IVUS demonstrates underdeployment, achieving MSA of only 5.61 mm2 (B) Compared with proximal reference segment of 10.40 mm2 (C). Bottom, both angiographically and IVUS-guided stent implantation. Angiogram after stent deployment in mid right coronary artery with 3.5-mm balloon inflated at 16 atm shows acceptable result (A). Initial IVUS (B) shows underdeployment. IVUS image after further dilatation with 4.0-mm balloon at 16 atm demonstrates substantial improvement in MSA (C).13 IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; MSA, minimal stent area.

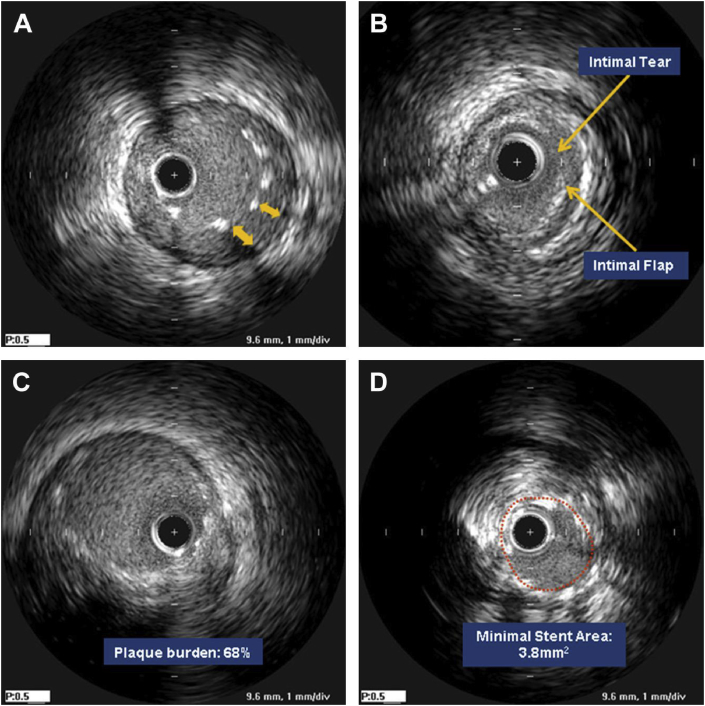

Other reasons such as stent malapposition, edge dissection, inadequate coverage of plaque and so forth for a suboptimal result after PCI which cannot be identified with angiography alone can be picked up by IVUS in the immediate postprocedure period, thereby prompting corrective steps which lead to improved procedural and clinical outcomes (Fig. 2).18

Fig. 2.

Suboptimal stent results seen with IVUS. (A) Acute incomplete stent apposition underexpansion, (B) edge dissection, (C) large edge plaque burden, and (D) underexpansion.18

Use of IVUS to optimize PCI reduces target vessel revascularization as well as other outcomes including major adverse cardiac events (MACEs) when compared with angiography alone both in bare-metal stent (BMS) and drug-eluting stent (DES) eras.16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Recent guidelines have endorsed the use of IVUS for specific situations (Table 3).2, 22, 23, 24

Table 3.

Current guidelines for IVUS use.

| Guideline | Year | Recommendation | Class of recommendation | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESC/EACTS Guideline23 | 2014 |

|

II a | B |

|

II a | B | ||

|

II a | C | ||

| ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline24 | 2011 |

|

II a | B |

|

II a | B | ||

|

II a | C | ||

|

II b | B | ||

|

II b | B | ||

|

II b | C | ||

|

III | C |

ACCF, American College of Cardiology Foundation; AHA, American Heart Association; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; EACTS, European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; SCAI, Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions.

Several meta-analyses which have included randomized trials, registries, and observational studies have been published on the role of IVUS during PCI with BMS and DES.16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29 The most recent of these meta-analyses by Steinvil et al concluded that IVUS-guided PCI was associated with better overall clinical outcomes than angiography-guided DES implantation. However, in a meta-analysis of only randomized controlled trials (RCTs), this benefit was mainly driven by reduced rates of revascularizations.21, 30

Most of these meta-analyses are limited by the lack of uniform criteria for IVUS use and lack of homogeneity with regard to clinical scenarios. Further research with adequately powered RCTs is needed in specific subgroups [bifurcation lesions, left main disease, chronic total occlusions (CTOs)] in which routine imaging guidance in addition to angiography is expected to significantly alter decision-making during PCI.

1.2. OCT guidance for PCI

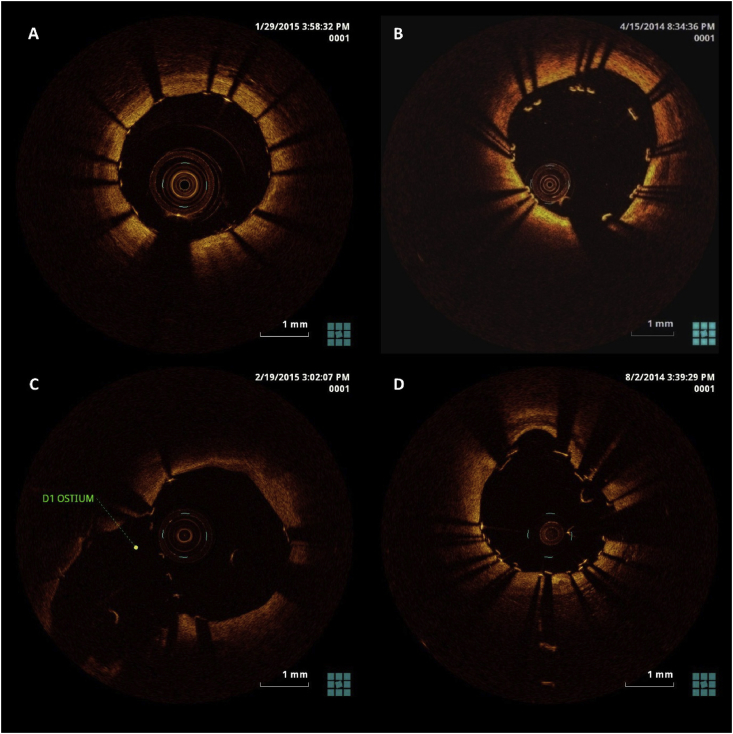

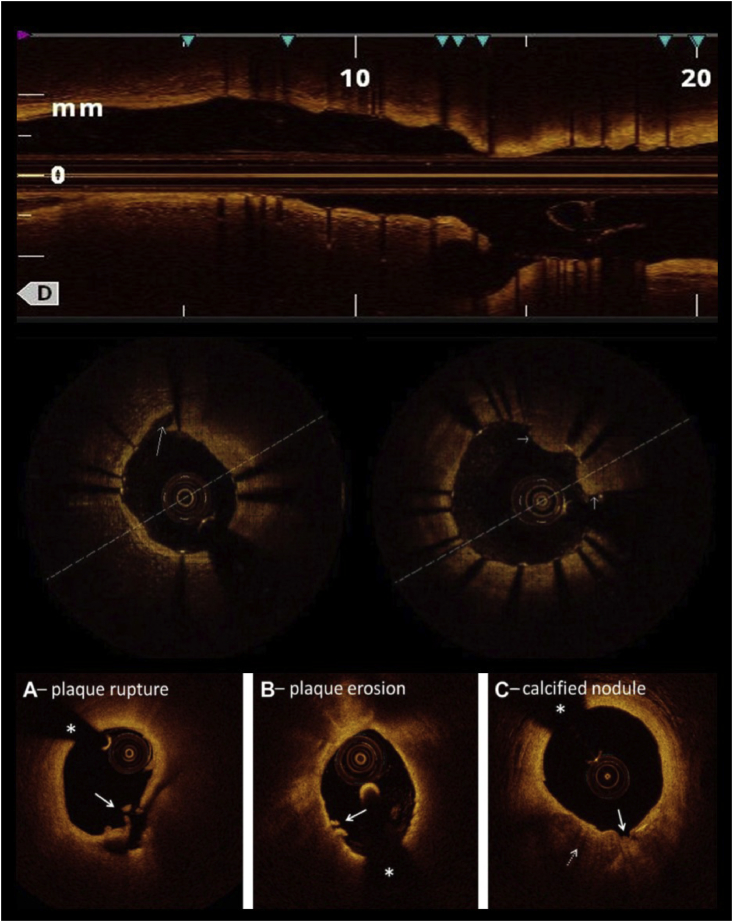

The clear visualization of surface of vessel lumen with high resolution is the main strength of OCT over IVUS. OCT can therefore image lumen-vessel wall and lumen-stent interface better than IVUS. This means better identification of mechanisms of stent failures (e.g., stent malapposition, dissection, tissue protrusion, and thrombus) and also, culprit lesions in acute coronary syndromes (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). However, OCT cannot measure plaque burden because of its shallow penetration depth (1–2 mm).1

Fig. 3.

OCT guidance during PCI. (A) OCT after stent placement showing well-apposed stent. B, Malapposed stent struts visualized with OCT which led to postdilation with a larger balloon. C, Stent struts visualized at ostium of the first diagonal branch of the left anterior descending coronary artery. For bifurcation angioplasty, OCT guidance can be used to select the distal most cell for passing guidewire. D, Two layers of well-apposed stent struts visualized after bifurcation angioplasty with Crush technique. OCT, optical coherence tomography

Fig. 4.

Top, OCT pullback after stenting showing longitudinal view of the vessel. Stent length can be measured and side-branch ostium visualized. The same view can be used pre-PCI to decide stent length and landing zones. Middle left, stent edge dissection as seen on OCT (long arrow). Middle right, tissue prolapse through stent struts (short arrows). Bottom, OCT findings in acute coronary syndrome. (A) Plaque rupture is defined as a lipid plaque with fibrous cap discontinuity (arrow) and cavity formation inside the plaque. (B) Definite plaque erosion is defined by the presence of attached thrombus (arrow) overlying an intact and visualized plaque. (C) Calcified nodules are defined by fibrous cap disruption (solid arrow) with underlying calcified plaque (dotted arrow) characterized by protruding calcification, superficial calcium, or the presence of significant calcium adjacent to the lesion. The asterisks denote guidewire shadow artifact. OCT, optical coherence tomography.

The Centro per la Lotta contro l'Infarto-Optimisation of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CLI-OPCI) observational study, which showed that angiographic plus OCT guidance was associated with a significantly lower risk of cardiac death or myocardial infarction.1 Importantly, for the first time, the CLI-OPCI study addressed the question of how to interpret OCT findings by setting specific quantitative criteria to identify suboptimal stent deployment. Suboptimal stent deployment was defined as the presence of at least 1 of the OCT findings given in Table 4 below.

Table 4.

| Findings | Definition |

|---|---|

| Edge dissection | Linear rim of tissue with a width >0.2 mm and a clear separation from the vessel wall or underlying plaque that was adjacent (<5 mm) to a stent edge. Longitudinal extension >2 mm, lateral extension >60° and involvement of deeper layers (medial or adventitia) are considered large dissections. |

| Intrastent plaque/thrombus protrusion | Tissue prolapsing between stent struts extending inside a circular arc connecting adjacent struts or intraluminal mass >0.5 mm in thickness with no direct continuity with the surface of the vessel wall or highly backscattered luminal protrusion in continuity with the vessel wall and resulting in signal-free shadowing. |

| Reference lumen narrowing | Lumen area <4.5 mm2 in the presence of significant plaque adjacent to stent endings. |

| Stent malapposition | Stent-adjacent vessel lumen distance >0.4 mm with longitudinal extension >1 mm. |

| In-stent minimal luminal cross-sectional area (MLA) | In-stent MLA <4.5 mm2 and <70% of the average reference lumen area is considered significant. |

OCT, optical coherence tomography.

Retrospective analysis of clinical outcomes in patients undergoing end-procedural OCT assessment in the CLI-OPCI II study showed that suboptimal stent deployment was associated with an increased risk of MACE during follow-up.36

A multicenter study, ILUMIEN I, involving 418 patients evaluated the impact of pre-PCI and post-PCI OCT on clinical decision-making during PCI. Altogether, OCT impacted the PCI procedure in 65% of the patients pre-PCI and/or post-PCI.37 Operators changed their strategy based on pre-PCI OCT in 57% of cases; mostly involving change in number, length, or diameter of stents used. Post-PCI OCT findings during optimization stage (edge dissection, malapposition, thrombus, underexpansion) influenced strategy in 27% of cases. A drawback of this study was that there were no upfront rules on how to interpret pre-PCI OCT.37 Further studies are needed on OCT parameters that predict short- and long-term clinical outcomes. The current guidelines for use of OCT are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Current guidelines for OCT use.

| Guideline | Year | Recommendation | Class of recommendation | Level of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization23 | 2014 |

|

II b | C |

|

II a | C | ||

| ESC guidelines on the management of stable CAD38 | 2013 |

|

II b | B |

|

II b | B | ||

| SCAI Consensus Statement39 | 2014 |

|

NA | NA |

ESC, European Society of Cardiology; EACTS, European Association for Cardiothoracic Surgery; NA, not applicable; OCT, optical coherence tomography; SCAI, Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions.

OCT is still a relatively newer imaging modality and therefore lacks adequate data and standardization to identify suboptimal stent deployment, stent lumen, and minimal lumen areas. In fact, lumen dimensions measured by OCT were smaller than those measured by IVUS as reported by several studies.40, 41, 42, 43, 44 Using IVUS criteria during PCI with OCT guidance may therefore lead to suboptimal stent expansion and poor clinical outcomes.

Furthermore, reliable image acquisition with OCT systems requires injection of contrast media to displace blood from vessel wall lumen because OCT signal is attenuated by the presence of red blood cells. This increases the risk of contrast nephropathy which then may lead to poor clinical outcomes, especially in patients with underlying renal dysfunction. Hence, a substitute for contrast is necessary to further improve outcomes when using OCT.

Despite unmatched resolution with OCT, underestimation of reference vessel diameter resulting in smaller luminal diameters after stent implantation has been reported by few studies including the OPINION trial.37, 43, 44 The principle reason being the measurement of lumen diameter as reference instead of vessel wall diameter especially in the presence of significant plaque burden and diffuse disease. The ILUMIEN II study, a post hoc analysis of two prospective studies (ILUMIEN and ADAPT-DES), showed that OCT and IVUS guidance resulted in a comparable degree of stent expansion.45 In the ILUMIEN III study, the authors used a novel OCT-based stent-sizing strategy by measuring proximal and distal reference mean external elastic lamina diameters and using the smaller of these diameters rounded down to the nearest 0.25 mm to determine stent diameter. This strategy resulted in a similar minimum stent area compared with IVUS-guided PCI.46

2. Imaging guidance in specific subgroups

Additional imaging guidance are expected to improve outcomes in interventions involving specific subgroups such as bifurcation lesions, left main coronary artery (LMCA) lesions, chronic total occlusions, calcified lesions, and in-stent restenosis which are considered to be complex or high risk where the results tend to be poorer.

2.1. Left main coronary artery lesions

There has been a recent surge in LMCA interventions, hitherto considered to be a cardiovascular surgeon's domain.47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52 Short vessel length, lack of normal reference segment, streaming of contrast agent, and aortic cusp calcification hinder assessment of true lumen size and lesion morphology of LMCA lesions by angiography alone.53 Therefore, IVUS assessment can be helpful in detecting significant stenosis, selecting stent with appropriate length and diameter, and help guide optimal stent placement and expansion.53, 54, 55, 56 Both the recently published EXCEL and NOBLE trials have used IVUS extensively during unprotected LMCA PCI. While the EXCEL trial investigators concluded that PCI is noninferior to coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), the NOBLE trial showed CABG to be better after 3 years of follow-up. Nonetheless, both studies demonstrated safety and immediate procedural success with the use of IVUS.57, 58

An IVUS-derived minimal luminal cross-sectional area (MLA) cutoff of 6 mm2 for revascularization has correlated well with outcomes in intermediate LMCA lesions on angiography (30–60%).59 However, in light of several nonrandomized trials recommending different MLA cutoffs, a recent review proposed that revascularization can be recommended when MLA is < 4.5 mm2 on IVUS. For LMCA lesions with MLA between 4.5 and 6 mm2, fractional flow reserve or noninvasive stress test is to be considered before revascularization.60, 61, 62, 63

Several studies have suggested that IVUS-guided stent implantation for LMCA disease is associated with improved survival during long-term clinical follow-up.64, 65 This led to a class IIa recommendation for the use of IVUS for LMCA intervention in the recent ESC/EACTS guidelines.23

Studies are underway for the use of OCT in LMCA interventions especially involving its bifurcation. However, OCT is not a good choice for left main ostial disease due to difficulty in achieving a blood-less field required for optimal OCT imaging. Therefore, IVUS is the imaging modality of choice in this subgroup.

2.2. Bifurcation lesions

Bifurcation lesions are particularly difficult to assess by angiography alone because overlapping side branches often obscure the lesion. PCI of bifurcation lesions is technically challenging due to multiple factors that include bifurcation angle, bifurcation site, plaque burden and morphology, branch diameter, and also dynamic variability during PCI because of plaque shifts, dissections causing side-branch compromise.66, 67, 68 Intravascular imaging guidance during bifurcation PCI is useful in assessing side-branch ostium, selecting sizes of stents, and appropriate stenting strategy and after stenting to assess stent expansion, malapposition, dissection, and side-branch ostium. Studies evaluating the impact of IVUS and OCT guidance for bifurcation PCI have shown mixed results.69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76 Intravascular imaging has also been used to identify mechanisms and predictors of side-branch pinching. In this regard, the “eyebrow sign” or the “spiky carina” is a powerful predictor of ostial side-branch damage after stent implantation in the main branch in bifurcation coronary lesions without plaque involving the side branch.77, 78 Furthermore, 3D OCT has been used to guide accurate distal cell rewiring at side-branch ostium which leads to improved procedural results.79, 80 The OCTOBER trial, ongoing multicenter European trial, is comparing 2-year clinical outcomes after OCT-guided vs standard-guided revascularization of patients requiring complex bifurcation stent implantation.

Left main bifurcation lesions are high-risk complex lesions in which intravascular imaging guidance may be indispensable. Even in the era of DES, the left main bifurcation location is a major determinant of adverse outcomes.81, 82 Kang et al found that the best IVUS predictors of angiographic restenosis were minimal stent areas (MSAs) of <8.2 mm2 in the proximal left main, <7.2 mm2 in the polygon of confluence, <6.3 mm2 in the ostial left anterior descending, and <5.0 mm2 in the ostial left circumflex. When adequate expansion was defined as stent areas above these thresholds at all four locations, angiographic restenosis was greater with “underexpansion” compared with “adequate expansion”. More importantly, freedom from major adverse events was higher in patients with adequate stent expansion compared with underexpansion.83

2.3. Chronic total occlusion

PCI of CTO is still challenging even with the current advancement in equipment and techniques and has been associated with poor clinical outcomes.84, 85, 86, 87 Using IVUS guidance is one way to improve overall PCI outcomes although there have been only a few studies in this area.

A randomized study by Kim et al88 showed that IVUS guidance did not significantly reduce cardiac mortality when compared with angiography guidance but did demonstrate an improvement in MACE at 12 months.

To facilitate the passage of guidewires across CTOs, intravascular imaging guidance using IVUS has been used, and several successful techniques have emerged. Important examples include crossing stumpless CTO lesions, reverse controlled antegrade and retrograde subintimal tracking technique for complex CTO, and novel techniques such as transvenous placement of IVUS catheter to facilitate guidewire passage.89, 90, 91, 92 IVUS is also useful to assess the true vessel size distal to the CTO as negative remodeling is very common in chronically underfilled vessels. Although recommending such strategies for routine practice needs larger randomized trials demonstrating effectiveness, it gives us a glimpse of the possibilities that IVUS guidance can bring to the table in such complex coronary interventions.

Use of OCT in CTO intervention has been limited to evaluation of results after stenting to look for malapposition, dissection, and during follow-up to evaluate mechanisms of stent failure.93

OCT and IVUS are currently limited to lateral imaging as forward-looking catheters are not yet commercially available. Forward-looking catheters which will facilitate direct visualization of proximal cap of CTO and passage of guidewires under direct visual guidance can make CTO interventions safer and more successful.94, 95

2.4. Calcified lesions

Intravascular imaging studies, mostly using IVUS, and more recently studies using OCT, have been instrumental in understanding the relationship between calcium and coronary atherosclerosis, the predictors, the natural history, and the impact on treatment.96

Severe calcification as assessed by intravascular imaging limits stent expansion, and severe stent underexpansion can be associated with adverse events including restenosis and stent thrombosis.97, 98, 99, 100, 101 Treating stent underexpansion in a heavily calcified lesion is more difficult than preventing underexpansion.102

Lesion preparation can involve the use of a cutting or scoring balloon, excimer laser angioplasty, or rotational or orbital atherectomy. IVUS and OCT have been used to evaluate the effectiveness of such techniques, to help optimize stent expansion, and also to predict postprocedural complications based on the pattern of calcification. OCT can be used to assess the depth of calcium and therefore has an edge over IVUS which only the superficial arc.103

IVUS and OCT studies have shown that excimer laser coronary angioplasty does not decrease lesion-associated calcium but causes dissections and, especially, fragmentation of calcific deposits98, 104 and that rotational (and probably) orbital atherectomy ablate calcium to cause fissuring or cracks within the ablated calcium.100, 101

However, there are a lack of systematic, consistent, conclusive confirmatory data with any intravascular imaging technique (IVUS or OCT) in a large number of patients in PCI of calcific lesions.

2.5. Stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis

IVUS-guided PCI has the potential for accurate measurement of lesion length and minimal stent diameters and areas, allowing for adequate stent expansion and coverage, thereby preventing stent thrombosis and in-stent and edge restenoses.105, 106, 107, 108 Finally, IVUS may be useful to ensure full stent-vessel wall apposition, although this is of less importance than stent underexpansion and lesion coverage. In fact, stent malapposition may lead to inadequate drug delivery and DES failure and has been associated with late stent thrombosis.109 The reductions in restenosis and stent thrombosis achieved may reduce the impact of routine IVUS guidance on revascularization rates.105

In patients who present with suspected stent thrombosis, IVUS and OCT are helpful in identifying the underlying mechanism such as stent underexpansion, malapposition, neoatherosclerosis, uncovered stent struts, and lesions at stent edges and in guiding PCI to achieve optimal results.110, 111, 112 Most of these aforementioned causes are potentially preventable by using intravascular imaging guidance during the index procedure.

The mechanism of in-stent restenosis (ISR) has been studied in new light using IVUS and OCT and has helped us understand the pathophysiology behind ISR.113, 114 The most common underlying causes of ISR are intimal hyperplasia and stent underexpansion.115 Time course, patterns (focal, multifocal, diffuse, stent edge), and mechanism of ISR is different for BMS and DES. Some studies have reported differences between different generations of DES.116 IVUS and OCT not only identify the causes but also guide the interventionist to take appropriate corrective measures to address them effectively.116, 117

2.6. Long coronary artery stenoses

In the BMS era, a randomized trial has shown that IVUS guidance when treating long lesions improves immediate- and long-term angiographic and clinical outcomes.118 In the DES era, initial studies using IVUS guidance for stent implantation in long lesions did not improve the 1-year MACE rates. However, IVUS use per operator decision was associated with improved results.119 But IVUS-XPL trial published in 2015 showed a significant reduction in MACE at 1 year when IVUS guidance was used for stent implantation compared with angiographic guidance alone.30

2.7. Other subgroups

Other subgroups in which intravascular imaging guidance during PCI has the potential to improve clinical outcomes are acute coronary syndromes, small vessel disease, bypass graft occlusions, bioresorbable vascular scaffolds, and so on. Ongoing research will provide us with more evidence to successfully use IVUS and OCT guidance to optimize clinical outcomes in these difficult-to-treat subgroups.120, 121, 122

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ihj.2018.08.012.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Prati F., Di Vito L., Biondi-Zoccai G. Angiography alone versus angiography plus optical coherence tomography to guide decision-making during percutaneous coronary intervention: the Centro per la Lotta contro l'Infarto-Optimisation of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CLI-OPCI) study. EuroIntervention. 2012;8(7):823–829. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I7A125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waksman R., Kitabata H., Prati F., Albertucci M., Mintz G.S. Intravascular ultrasound versus optical coherence tomography guidance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(suppl 17):S32–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garrone P., Biondi-Zoccai G., Salvetti I. Quantitative coronary angiography in the current era: principles and applications. J Interv Cardiol. 2009;22(6):527–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2009.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witzenbichler B., Maehara A., Weisz G. Relationship between intravascular ultrasound guidance and clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stents: the assessment of dual antiplatelet therapy with drug-eluting stents (ADAPT-DES) study. Circulation. 2014;129(4):463–470. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferrante G., Presbitero P., Whitbourn R., Barlis P. Current applications of optical coherence tomography for coronary intervention. Int J Caridol. 2013;165:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mintz G.S., Nissen S.E., Anderson W.D. American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document on Standards for Acquisition, Measurement and Reporting of Intravascular Ultrasound Studies (IVUS). A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on clinical expert consensus documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(5):1478–1492. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01175-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang I.K. Optical coherence tomography or intravascular ultrasound? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(5):492–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batkoff B.W., Linker D.T. Safety of intracoronary ultrasound: data from a multicenter European registry. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1996;38(3):238–241. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0304(199607)38:3<238::AID-CCD3>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hausmann D., Erbel R., Alibelli-Chemarin M.J. The safety of intracoronary ultrasound. A multicenter survey of 2207 examinations. Circulation. 1995;91(3):623–630. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.3.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sonoda S., Morino Y., Ako J. Impact of final stent dimensions on long-term results following sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: serial intravascular ultrasound analysis from the sirius trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(11):1959–1963. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song H.G., Kang S.J., Ahn J.M. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of optimal stent area to prevent in-stent restenosis after zotarolimus-, everolimus-, and sirolimus-eluting stent implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83(6):873–878. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fujii K., Carlier S.G., Mintz G.S. Stent underexpansion and residual reference segment stenosis are related to stent thrombosis after sirolimus-eluting stent implantation: an intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(7):995–998. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fitzgerald P.J., Oshima A., Hayase M. Final results of the Can Routine Ultrasound Influence Stent Expansion (CRUISE) study. Circulation. 2000;102(5):523–530. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doi H., Maehara A., Mintz G.S. Impact of post-intervention minimal stent area on 9-month follow-up patency of paclitaxel-eluting stents: an integrated intravascular ultrasound analysis from the TAXUS IV, V, and VI and TAXUS ATLAS Workhorse, Long Lesion, and Direct Stent Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(12):1269–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi S.Y., Witzenbichler B., Maehara A. Intravascular ultrasound findings of early stent thrombosis after primary percutaneous intervention in acute myocardial infarction: a Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction (HORIZONS-AMI) substudy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(3):239–247. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.959791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang Y., Farooq V., Garcia-Garcia H.M. Comparison of intravascular ultrasound versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation: a meta-analysis of one randomised trial and ten observational studies involving 19,619 patients. EuroIntervention. 2012;8(7):855–865. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I7A129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahn J.M., Kang S.J., Yoon S.H. Meta-analysis of outcomes after intravascular ultrasound-guided versus angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation in 26,503 patients enrolled in three randomized trials and 14 observational studies. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(8):1338–1347. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park S.J., Ahn J.M. Intravascular ultrasound for the assessment of coronary lesion severity and optimization of percutaneous coronary interventions. Interv Cardiol Clin. 2015;4(3):383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.iccl.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang J.S., Song Y.J., Kang W. Intravascular ultrasound-guided implantation of drug-eluting stents to improve outcome: a meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7(3):233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Y.J., Pang S., Chen X.Y. Comparison of intravascular ultrasound guided versus angiography guided drug eluting stent implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15(1):153. doi: 10.1186/s12872-015-0144-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinvil A., Zhang Y.J., Lee S.Y. Intravascular ultrasound-guided drug-eluting stent implantation: an updated meta-analysis of randomized control trials and observational studies. Int J Cardiol. 2016;216:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.04.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amsterdam E.A., Wenger N.K., Brindis R.G. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130(25):e344–e426. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Authors/Task Force m, Windecker S., Kolh P. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization: the task force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Eur Heart J. 2014;35(37):2541–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine G.N., Bates E.R., Blankenship J.C. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions. Circulation. 2011;124(23):e574–e651. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ba622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parise H., Maehara A., Stone G.W., Leon M.B., Mintz G.S. Meta-analysis of randomized studies comparing intravascular ultrasound versus angiographic guidance of percutaneous coronary intervention in pre-drug-eluting stent era. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(3):374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sbruzzi G., Quadros A.S., Ribeiro R.A. Intracoronary ultrasound-guided stenting improves outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2012;98(1):35–44. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2011005000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Figueiredo Neto J.A., Nogueira I.A., Figueiro M.F., Buehler A.M., Berwanger O. Angioplasty guided by intravascular ultrasound: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013;101(2):106–116. doi: 10.5935/abc.20130131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klersy C., Ferlini M., Raisaro A. Use of IVUS guided coronary stenting with drug eluting stent: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials and high quality observational studies. Int J Cardiol. 2013;170(1):54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alsidawi S., Effat M., Rahman S., Abdallah M., Leesar M. The role of vascular imaging in guiding routine percutaneous coronary interventions: a meta-analysis of bare metal stent and drug-eluting stent trials. Cardiovasc Ther. 2015;33(6):360–366. doi: 10.1111/1755-5922.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hong S.J., Kim B.K., Shin D.H. Effect of intravascular ultrasound-guided vs angiography-guided everolimus-eluting stent implantation: the IVUS-XPL randomized clinical trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2015;314(20):2155–2163. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prati F., Regar E., Mintz G.S. Expert review document on methodology, terminology, and clinical applications of optical coherence tomography: physical principles, methodology of image acquisition, and clinical application for assessment of coronary arteries and atherosclerosis. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(4):401–415. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imola F., Mallus M.T., Ramazzotti V. Safety and feasibility of frequency domain optical coherence tomography to guide decision making in percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention. 2010;6:575–581. doi: 10.4244/EIJV6I5A97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanigawa J., Barlis P., Di Mario C. Intravascular optical coherence tomography: optimisation of image acquisition and quantitative assessment of stent strut apposition. EuroIntervention. 2007;3(1):128–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Serruys P.W., Onuma Y., Ormiston J.A. Evaluation of the second generation of a bioresorbable everolimus drug-eluting vascular scaffold for treatment of de novo coronary artery stenosis clinical perspective. six-month clinical and imaging outcomes. Circulation. 2010;122(22):2301–2312. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raber L., Mintz G.S., Koskinas K.C. Clinical use of intracoronary imaging. Part 1: guidance and optimization of coronary interventions. An expert consensus document of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions: endorsed by the Chinese Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2018;22 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prati F., Romagnoli E., Burzotta F. Clinical impact of OCT findings during PCI: the CLI-OPCI II study. Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(11):1297–1305. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wijns W., Shite J., Jones M.R. Optical coherence tomography imaging during percutaneous coronary intervention impacts physician decision-making: ILUMIEN I study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(47):3346–3355. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montalescot G., Sechtem U., Achenbach S. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the task force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(38):2949–3003. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lotfi A., Jeremias A., Fearon W.F. Expert consensus statement on the use of fractional flow reserve, intravascular ultrasound, and optical coherence tomography: a consensus statement of the Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83(4):509–518. doi: 10.1002/ccd.25222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaguchi T., Terashima M., Akasaka T. Safety and feasibility of an intravascular optical coherence tomography image wire system in the clinical setting. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(5):562–567. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.09.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gonzalo N., Serruys P.W., Garcia-Garcia H.M. Quantitative ex vivo and in vivo comparison of lumen dimensions measured by optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound in human coronary arteries. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2009;62(6):615–624. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(09)72225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okamura T., Onuma Y., Garcia-Garcia H.M. First-in-man evaluation of intravascular optical frequency domain imaging (OFDI) of Terumo: a comparison with intravascular ultrasound and quantitative coronary angiography. EuroIntervention. 2011;6(9):1037–1045. doi: 10.4244/EIJV6I9A182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Habara M., Nasu K., Terashima M. Impact of frequency-domain optical coherence tomography guidance for optimal coronary stent implantation in comparison with intravascular ultrasound guidance. Circulation Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(2):193–201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.965111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kubo T., Shinke T., Okamura T. Optical frequency domain imaging vs. intravascular ultrasound in percutaneous coronary intervention (OPINION trial): one-year angiographic and clinical results. Euro Heart J. 2017;38(42):3139–3147. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maehara A., Ben-Yehuda O., Ali Z. Comparison of stent expansion guided by optical coherence tomography versus intravascular ultrasound: the ILUMIEN II study (Observational study of optical coherence tomography [OCT] in patients undergoing fractional flow reserve [FFR] and percutaneous coronary intervention) JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(13):1704–1714. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ali Z.A., Maehara A., Généreux P. Optical coherence tomography compared with intravascular ultrasound and with angiography to guide coronary stent implantation (ILUMIEN III: OPTIMIZE PCI): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10060):2618–2628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31922-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buszman P.E., Kiesz S.R., Bochenek A. Acute and late outcomes of unprotected left main stenting in comparison with surgical revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(5):538–545. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanmartin M., Baz J.A., Claro R. Comparison of drug-eluting stents versus surgery for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(6):970–973. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palmerini T., Marzocchi A., Marrozzini C. Comparison between coronary angioplasty and coronary artery bypass surgery for the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis (the Bologna Registry) Am J Cardiol. 2006;98(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim Y.H., Park S.W., Hong M.K. Comparison of simple and complex stenting techniques in the treatment of unprotected left main coronary artery bifurcation stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(11):1597–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee M.S., Kapoor N., Jamal F. Comparison of coronary artery bypass surgery with percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(4):864–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Biondi-Zoccai G.G., Lotrionte M., Moretti C. A collaborative systematic review and meta-analysis on 1278 patients undergoing percutaneous drug-eluting stenting for unprotected left main coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2008;155(2):274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sano K., Mintz G.S., Carlier S.G. Assessing intermediate left main coronary lesions using intravascular ultrasound. Am Heart J. 2007;154(5):983–988. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mintz G.S. Features and parameters of drug-eluting stent deployment discoverable by intravascular ultrasound. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(8B):26M–35M. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nissen S.E., Yock P. Intravascular ultrasound: novel pathophysiological insights and current clinical applications. Circulation. 2001;103(4):604–616. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Puri R., Kapadia S.R., Nicholls S.J., Harvey J.E., Kataoka Y., Tuzcu E.M. Optimizing outcomes during left main percutaneous coronary intervention with intravascular ultrasound and fractional flow reserve: the current state of evidence. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(7):697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stone G.W., Sabik J.F., Serruys P.W. Everolimus-eluting stents or bypass surgery for left main coronary artery disease. New Engl J Med. 2016;375(23):2223–2235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mäkikallio T., Holm N.R., Lindsay M. Percutaneous coronary angioplasty versus coronary artery bypass grafting in treatment of unprotected left main stenosis (NOBLE): a prospective, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10061):2743–2752. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de la Torre Hernandez J.M., Hernandez Hernandez F., Alfonso F. Prospective application of pre-defined intravascular ultrasound criteria for assessment of intermediate left main coronary artery lesions results from the multicenter LITRO study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(4):351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fassa A.A., Wagatsuma K., Higano S.T. Intravascular ultrasound-guided treatment for angiographically indeterminate left main coronary artery disease: a long-term follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(2):204–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jasti V., Ivan E., Yalamanchili V., Wongpraparut N., Leesar M.A. Correlations between fractional flow reserve and intravascular ultrasound in patients with an ambiguous left main coronary artery stenosis. Circulation. 2004;110(18):2831–2836. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000146338.62813.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leesar M.A., Masden R., Jasti V. Physiological and intravascular ultrasound assessment of an ambiguous left main coronary artery stenosis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;62(3):349–357. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McDaniel M.C., Eshtehardi P., Sawaya F.J., Douglas J.J.S., Samady H. Contemporary clinical applications of coronary intravascular ultrasound. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(11):1155–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park S.J., Kim Y.H., Park D.W. Impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance on long-term mortality in stenting for unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(3):167–177. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.799494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Andell P., Karlsson S., Mohammad M.A. Intravascular ultrasound guidance is associated with better outcome in patients undergoing unprotected left main coronary artery stenting compared with angiography guidance alone. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(5):e004813. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.116.004813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Stinis C.T., Hu S.P., Price M.J., Teirstein P.S. Three-year outcome of drug-eluting stent implantation for coronary artery bifurcation lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75(3):309–314. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Steigen T.K., Maeng M., Wiseth R. Randomized study on simple versus complex stenting of coronary artery bifurcation lesions: the Nordic bifurcation study. Circulation. 2006;114(18):1955–1961. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Latib A., Colombo A. Bifurcation disease: what do we know, what should we do? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1(3):218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Patel Y., Depta J.P., Novak E. Long-term outcomes with use of intravascular ultrasound for the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(7):960–965. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim S.H., Kim Y.H., Kang S.J. Long-term outcomes of intravascular ultrasound-guided stenting in coronary bifurcation lesions. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(5):612–618. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim J.-S., Hong M.-K., Ko Y.-G. Impact of intravascular ultrasound guidance on long-term clinical outcomes in patients treated with drug-eluting stent for bifurcation lesions: data from a Korean multicenter bifurcation registry. Am Heart J. 2011;161(1):180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sgueglia G.A., Foin N., Todaro D. First optical coherence tomography follow-up of coronary bifurcation lesions treated by drug-eluting balloons. J Invasive Cardiol. 2015;27(4):191–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Holm N.R., Adriaenssens T., Motreff P., Shinke T., Dijkstra J., Christiansen E.H. OCT for bifurcation stenting: what have we learned? EuroIntervention. 2015;11(suppl V):V64–V70. doi: 10.4244/EIJV11SVA14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Viceconte N., Tyczynski P., Ferrante G. Immediate results of bifurcational stenting assessed with optical coherence tomography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81(3):519–528. doi: 10.1002/ccd.24337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pidlaoan V., Banerjee S., Brilakis E.S. Application of optical coherence tomography in the treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions. J Invasive Cardiol. 2012;24(2):E39–E42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tyczynski P., Ferrante G., Moreno-Ambroj C. Simple versus complex approaches to treating coronary bifurcation lesions: direct assessment of stent strut apposition by optical coherence tomography. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63(8):904–914. doi: 10.1016/s1885-5857(10)70184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Karanasos A., Tu S., van der Heide E., Reiber J.H.C., Regar E. Carina shift as a mechanism for side-branch compromise following main vessel intervention: insights from three-dimensional optical coherence tomography. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2012;2(2):173–177. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2012.04.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.de Lezo J., Medina A., Martin P. Predictors of ostial side branch damage during provisional stenting of coronary bifurcation lesions not involving the side branch origin: an ultrasonographic study. EuroIntervention. 2012;7(10):1147–1154. doi: 10.4244/EIJV7I10A185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Okamura T., Fujimura T., Yano M. Three-dimensional reconstruction of optical coherence tomography for improving bifurcation stenting. J Cardiol Cases. 2016;13(5):137–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jccase.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alegria-Barrero E., Foin N., Chan P.H. Optical coherence tomography for guidance of distal cell recrossing in bifurcation stenting: choosing the right cell matters. EuroIntervention. 2012;8(2):205–213. doi: 10.4244/EIJV8I2A34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim Y.H., Dangas G.D., Solinas E. Effectiveness of drug-eluting stent implantation for patients with unprotected left main coronary artery stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101(6):801–806. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Valgimigli M., Malagutti P., Rodriguez-Granillo G.A. Distal left main coronary disease is a major predictor of outcome in patients undergoing percutaneous intervention in the drug-eluting stent era: an integrated clinical and angiographic analysis based on the Rapamycin-Eluting Stent evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (RESEARCH) and Taxus-Stent evaluated at Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (T-SEARCH) registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(8):1530–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kang S.-J., Mintz G.S., Kim W.-J. Effect of intravascular ultrasound findings on long-term Repeat revascularization in patients undergoing drug-eluting stent implantation for severe unprotected left main bifurcation narrowing. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107(3):367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Van den Branden B.J., Rahel B.M., Laarman G.J. Five-year clinical outcome after primary stenting of totally occluded native coronary arteries: a randomised comparison of bare metal stent implantation with sirolimus-eluting stent implantation for the treatment of total coronary occlusions (PRISON II study) EuroIntervention. 2012;7(10):1189–1196. doi: 10.4244/EIJV7I10A190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Suero J.A., Marso S.P., Jones P.G. Procedural outcomes and long-term survival among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention of a chronic total occlusion in native coronary arteries: a 20-year experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38(2):409–414. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01349-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rathore S., Katoh O., Matsuo H. Retrograde percutaneous recanalization of chronic total occlusion of the coronary arteries: procedural outcomes and predictors of success in contemporary practice. Circulation Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(2):124–132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.838862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Patel M.R., Marso S.P., Dai D. Comparative effectiveness of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents in elderly patients undergoing revascularization of chronic total coronary occlusions: results from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry, 2005-2008. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(10):1054–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kim B.K., Shin D.H., Hong M.K. Clinical impact of intravascular ultrasound-guided chronic total occlusion intervention with zotarolimus-eluting versus Biolimus-eluting stent implantation: randomized study. Circulation Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8(7):e002592. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.115.002592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Park Y., Park H.S., Jang G.L. Intravascular ultrasound guided recanalization of stumpless chronic total occlusion. Int J Cardiol. 2011;148:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2009.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Takahashi Y., Okazaki H., Mizuno K. Transvenous IVUS-guided percutaneous coronary intervention for chronic total occlusion: a novel strategy. J Invasive Cardiol. 2013;25(7):E143–E146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dai J., Katoh O., Kyo E., Tsuji T., Watanabe S., Ohya H. Approach for chronic total occlusion with intravascular ultrasound-guided reverse controlled antegrade and retrograde tracking technique: single center experience. J Interv Cardiol. 2013;26(5):434–443. doi: 10.1111/joic.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rathore S., Katoh O., Tuschikane E., Oida A., Suzuki T., Takase S. A novel modification of the retrograde approach for the recanalization of chronic total occlusion of the coronary arteries intravascular ultrasound-guided reverse controlled antegrade and retrograde tracking. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3(2):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sherbet D.P., Christopoulos G., Karatasakis A. Optical coherence tomography findings after chronic total occlusion interventions: insights from the “AngiographiC evaluation of the everolimus-eluting stent in chronic Total occlusions” (ACE-CTO) study ( NCT01012869) Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2016;17:444–449. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Qureshi Y.H., Weisz G., Maehara A. Optical coherence tomography for guiding wire into a side branch coronary artery with flush total occlusion. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16(1):55–57. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mena C.I., Scheinert D. TCT-73 forward-looking IVUS: Technology overview and first-in-human case review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(18_S1):B23–B. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mintz G.S. Intravascular imaging of coronary calcification and its clinical implications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8(4):461–471. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Mintz G.S. Clinical utility of intravascular imaging and physiology in coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(2):207–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mintz G.S., Kovach J.A., Javier S.P. Mechanisms of lumen enlargement after excimer laser coronary angioplasty. An intravascular ultrasound study. Circulation. 1995;92(12):3408–3414. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.von Birgelen C., Mintz G.S., Böse D. Impact of moderate lesion calcium on mechanisms of coronary stenting as assessed with three-dimensional intravascular ultrasound in vivo. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(1):5–10. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00455-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Attizzani G.F., Patricio L., Bezerra H.G. Optical coherence tomography assessment of calcified plaque modification after rotational atherectomy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81(3):558–561. doi: 10.1002/ccd.23385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kovach J.A., Mintz G.S., Pichard A.D. Sequential intravascular ultrasound characterization of the mechanisms of rotational atherectomy and adjunct balloon angioplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22(4):1024–1032. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90412-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Latib A., Takagi K., Chizzola G. Excimer Laser LEsion modification to expand non-dilatable stents: the ELEMENT registry. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2014;15(1):8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang X., Matsumura M., Mintz G.S. In vivo calcium detection by comparing optical coherence tomography, intravascular ultrasound, and angiography. JACC Cardiovasc imaging. 2017;10(8):869–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rawlins J., Talwar S., Green M., O'Kane P. Optical coherence tomography following percutaneous coronary intervention with Excimer laser coronary atherectomy. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2014;15(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bonello L., De Labriolle A., Lemesle G. Intravascular ultrasound-guided percutaneous coronary interventions in contemporary practice. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2009;102(2):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Javaid A., Chu W.W., Cheneau E. Comparison of paclitaxel-eluting stent and sirolimus-eluting stent expansion at incremental delivery pressures. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2006;7(4):208–211. doi: 10.1016/j.carrev.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.de Ribamar Costa J., Jr., Mintz G.S., Carlier S.G. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of drug-eluting stent expansion. Am Heart J. 2007;153(2):297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.de Ribamar Costa J., Jr., Mintz G.S., Carlier S.G. Intravascular ultrasonic assessment of stent diameters derived from manufacturer's compliance charts. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96(1):74–78. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Roy P., Torguson R., Okabe T. Angiographic and procedural correlates of stent thrombosis after intracoronary implantation of drug-eluting stents. J Interv Cardiol. 2007;20(5):307–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2007.00286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Alfonso F., Suárez A., Angiolillo D.J. Findings of intravascular ultrasound during acute stent thrombosis. Heart. 2004;90(12):1455–1459. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.026047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Guagliumi G., Sirbu V., Musumeci G. Examination of the in vivo mechanisms of late drug-eluting stent thrombosis. Findings from optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Adriaenssens T., Joner M., Godschalk T.C. Optical coherence tomography findings in patients with coronary stent thrombosis. A report of the PRESTIGE Consortium (Prevention of Late Stent Thrombosis by an Interdisciplinary global European Effort) Circulation. 2017;136(11):1007–1021. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.026788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Goto K., Zhao Z., Matsumura M. Mechanisms and patterns of intravascular ultrasound in-stent restenosis among bare metal stents and first- and second-generation drug-eluting stents. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(9):1351–1357. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Akhtar M., Liu W. Use of intravascular ultrasound vs. optical coherence tomography for mechanism and patterns of in-stent restenosis among bare metal stents and drug eluting stents. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(1):E104–E108. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.01.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kang S.J., Mintz G.S., Park D.W. Mechanisms of in-stent restenosis after drug-eluting stent implantation: intravascular ultrasound analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(1):9–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.110.940320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kilickesmez K., Dall'Ara G., Rama-Merchan J.C. Optical coherence tomography characteristics of in-stent restenosis are different between first and second generation drug eluting stents. IJC Heart Vessels. 2014;3:68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchv.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Alfonso F., Byrne R.A., Rivero F., Kastrati A. Current treatment of in-stent restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(24):2659–2673. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Oemrawsingh P.V., Mintz G.S., Schalij M.J. Intravascular ultrasound guidance improves angiographic and clinical outcome of stent implantation for long coronary artery stenoses: final results of a randomized comparison with angiographic guidance (TULIP Study) Circulation. 2003;107(1):62–67. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000043240.87526.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Kim J.-S., Kang T.-S., Mintz G.S. Randomized comparison of clinical outcomes between intravascular ultrasound and angiography-guided drug-eluting stent implantation for long coronary artery stenoses. JACC. Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6(4):369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Horváth M., Hájek P., Štěchovský C., Veselka J. Vulnerable plaque imaging and acute coronary syndrome. Cor Vasa. 2014;56(4):e362–e368. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pernigotti A., Moscarella E., Spitaleri G., Scardino C., Ishida K., Brugaletta S. Methods to assess bioresorbable vascular scaffold devices behaviour after implantation. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(suppl 9):S959–S968. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Secco G.G., Verdoia M., Pistis G. Optical coherence tomography guidance during bioresorbable vascular scaffold implantation. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(suppl 9):S986–S993. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.07.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.