Abstract

Objective:

Microbial infections and mucosal dysbiosis influence morbidity in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In the oral cavity, periodontal bacteria and subgingival plaque dysbiosis provide persistent inflammatory stimuli at the mucosal surface. This study was undertaken to evaluate whether exposure to periodontal bacteria influences disease parameters in SLE patients.

Methods:

Circulating antibodies to specific periodontal bacteria have been used as surrogate markers to determine an ongoing bacterial burden, or as indicators of past exposure to the bacteria. Banked serum samples from SLE patients in the Oklahoma Lupus Cohort were used to measure antibody titers against periodontal pathogens (Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, and Treponema denticola) and commensals (Capnocytophaga ochracea, and Streptococcus gordonii) by ELISA. Correlations between anti-bacterial antibodies and different clinical parameters of SLE including, autoantibodies (anti-dsDNA, anti-SmRNP, anti-SSA/Ro and anti-SSB/La), complement, and disease activity (SLEDAI and BILAG) were studied.

Results:

SLE patients had varying amounts of antibodies to different oral bacteria. The antibody titers against A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. denticola, and C. ochracea were higher in patients positive for anti-dsDNA antibodies, and they showed significant correlations with anti-dsDNA titers and reduced levels of complement. Among the periodontal pathogens, only antibodies to A. actinomycetemcomitans were associated with higher disease activity.

Conclusions:

Our results suggest that exposure to specific pathogenic periodontal bacteria influences disease activity in SLE patients. These findings provide a rationale for assessing and improving periodontal health in SLE patients, as an adjunct to lupus therapies.

MeSH: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Periodontitis, Antibodies

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus is a complex autoimmune disorder affecting multiple organ systems such as the skin, kidneys, heart, lung, and brain (1). The presence of autoantibodies against multiple self-components is a hall mark of SLE and the autoantibody specificities are associated with distinct pathologic features of the disease. In addition to a strong genetic predisposition, environmental factors, particularly infectious agents, can play a role in SLE pathogenesis. In SLE, microbes hold the potential to initiate and exacerbate autoimmunity, and modify the course of clinical disease by affecting multiple pathways (2).

The association between antibodies to infectious agents and antibodies to self-proteins has been established in a wide spectrum of autoimmune diseases (3, 4). Over the past several years, considerable attention has been directed towards investigating how viral exposures, such as Epstein Barr virus, influence the disease (5). However, bacterial infections affecting the respiratory tract, urinary tract, and skin are often seen in SLE patients (6). In addition to these anatomic sites, the gingival mucosal surface is continuously exposed to a plethora of bacteria present in the dental plaque. The interface between the dental plaque and the gingival epithelium represents a site of constant communication between microbes and the innate immune system (7). Further, these bacteria have access to the systemic circulation through bleeding gums and through direct invasion of the gingival epithelium (8, 9). Previous work from our laboratory suggests that the dental plaque can offer a chronic source of autoantigen mimics (10). T cells reactive with a Sjögren’s syndrome and lupus-associated autoantigen Ro60, can be activated by peptides derived from dental plaque bacteria. Thus, exposure of the immune system to dental plaque bacteria in SLE patients holds a significant potential to modulate the disease.

The knowledge of lupus patient responses to dental plaque bacteria is limited. The indication that lupus patients are exposed to these bacteria can be derived indirectly from reports showing higher incidence of periodontitis in SLE patients (11). In addition, a recent report on the characterization of the subgingival microbial community showed that compared to non-lupus controls, SLE patients have significant dysbiosis in the periodontal microbiota, with a greater proportion of pathogenic bacteria (12). Whether exposure to the periodontal bacteria affects disease activity in SLE is still not clear. The goal of the present study was to determine if bacteria in the dental plaque influence autoimmune features in SLE patients. Since high titers of IgG antibodies to plaque bacteria indicate either an ongoing infection or prior history of exposure (13–16), banked sera from a well characterized SLE patient cohort were analyzed for antibodies to a selected panel of oral bacteria. The associations between anti-bacterial antibodies and clinical disease were evaluated.

METHODS

Patients and controls

All experiments were performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation Institutional Review Board. Banked serum samples and clinical data were obtained from SLE patients seen from May 2002 to October 2014 in the Oklahoma Lupus Cohort through the Oklahoma Rheumatic Diseases Research Cores Center. Patients who met the ≥ 4 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) SLE criteria, and were evaluated for disease activity (n=303) were studied. The demographics of the patients in this study are shown in Table 1. Sera from a de-identified volunteers, who did not have SLE were also studied for anti-bacterial antibodies (n=75).

Table 1:

Oklahoma Lupus Cohort patient demographics

| SLE patients | |

|---|---|

| Total, n | 303 |

| Female, n (%) | 279 (92.1) |

| Age in years, median (range) | 40 (16–71) |

| Duration of disease in years, median (range) | 2 (0–39) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Caucasian | 165 (54.5) |

| African American | 62 (20.5) |

| Asian | 12 (3.9) |

| American Indian | 41(13.5) |

| Mixed (2 or more) | 22 (7.2) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (0.3) |

| ACR SLE criteria, median (range) | 6 (4–11) |

| SLEDAI, median (range), n | 6 (0–24), 300 |

| BILAG total, median (range), n | 11 (0–42), 303 |

Clinical parameters of SLE

Anti-dsDNA antibody was measured by the Crithidia luciliae indirect immunofluorescence assay. Antibodies to other autoantigens including Sm protein with ribonucleoproteins (SmRNP), Sjögren’s syndrome antigen A (SSA/Ro), and Sjögren’s syndrome antigen B (SSB/La) were measured using a bead-based assay. C3 and C4 complement levels were determined at the Diagnostic Laboratory of Oklahoma. Clinical assessments of SLE were done using the modified SELENA -Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI) (17) and the British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG2004) Index (18).

Bacterial strains

Bacterial strains residing in the subgingival plaque in the oral cavity were used as antigens for ELISA, and were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA). These include: red complex organisms implicated in chronic periodontal disease: Prophyromonas gingivalis (ATCC33277) and Treponema denticola (ATCC35405); a periodontal pathogen associated with aggressive periodontal disease: Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans serotype b (ATCC28522); and commensal bacteria: Streptococcus gordonii (ATCC51656) and Capnocytophaga ochracea (ATCC 33596).

Detection of antibody to bacterial strains

An ELISA-based assay to measure anti-bacterial antibodies was used as previously described (19). Sera from the Oklahoma Lupus Cohort were tested at 1:500 dilution. Serial dilutions of a pooled serum sample were included as a calibrator for each plate. A standard curve was constructed and anti-bacterial antibody titers (units/ml) were calculated for each sample. Samples with OD readings higher than the calibration curve were re-tested at higher dilutions.

Statistical analyses

Graph Pad Prism 7.0 and Systat software were used to perform statistical analyses. Normality tests were performed on each dataset, and non-parametric tests were used for non-Gaussian distributions. Mann-Whitney test was used to compare two populations, and Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-test was used for multiple comparisons. Correlations were determined by Spearman’s method. A p value of less than 0.05 at a 95% confidence interval was considered significant.

RESULTS

Higher anti-bacterial antibody titers against specific bacteria are associated with the presence of anti-dsDNA.

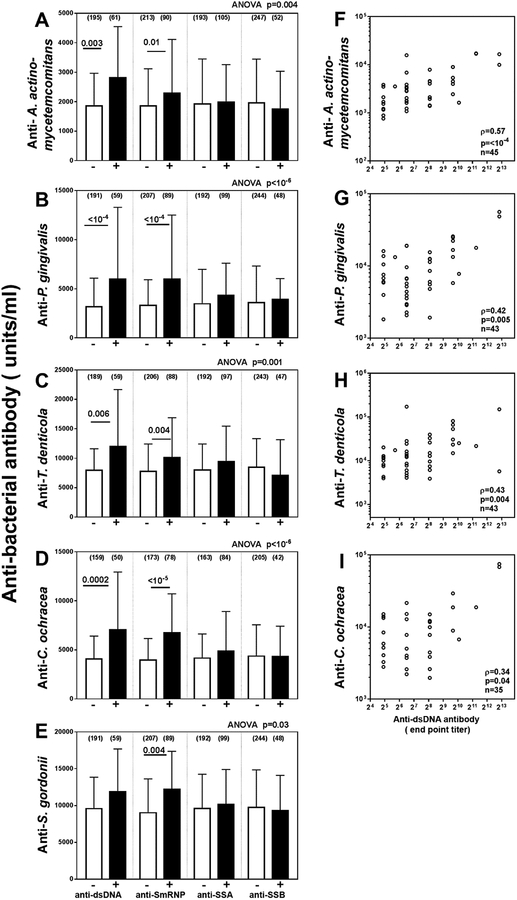

Patients were stratified into groups based on the presence or absence of antibodies to the major lupus-associated autoantigens: dsDNA, Sm/RNP, SSA/Ro, and SSB/La. The anti-bacterial antibody titers in the antibody positive and negative group for each autoantigen were compared. As shown in Figure 1A–E, patients with anti-dsDNA have higher antibodies to A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T. denticola, and C. ochracea, but not to S. gordonii, when compared to patients lacking anti-dsDNA. The presence of anti-SmRNP antibodies was associated with higher anti-bacterial antibody titers against all the bacteria, while anti-SSA and anti-SSB failed to associate with antibodies to any of the periodontal bacteria.

Figure 1: Presence of anti-dsDNA antibody in SLE patients is associated with higher antibody titers against A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, T.denticola and C. ochracea.

(A-E) SLE patients were stratified into autoantibody positive or autoantibody negative groups based on reactivity to dsDNA, SmRNP, SSA/Ro, and SSB/La respectively and anti-bacterial antibody titers were compared using Kruskal Wallis test. Dunn’s post-test was used to compare anti-bacterial antibodies between autoantibody positive and negative groups for each specificity. Anti-bacterial antibody titers are plotted as units/ml (median+interquartile range); (n) number of patients in each group.

(F-I) Correlation between anti-dsDNA titers and anti-bacterial antibody titers calculated by Spearman method.

Among the anti-dsDNA positive patients, anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans antibodies showed the strongest correlation (Spearman rho=0.57; p<10−4) with anti-dsDNA antibody titers (Figure 1F). Anti-P. gingivalis (rho=0.42; p=0.005), anti-T. denticola (rho=0.43; p=0.004) and anti-C. ochracea (rho=0.34; p=0.04) also showed statistically significant, albeit more modest correlations (Figure 1G–I).

Antibodies to specific periodontal pathogens correlate with indicators of higher disease activity in SLE patients.

SLE patients were categorized based on disease activity into mild (SLEDAI ≤2), moderately severe (SLEDAI 3–9) and severe (SLEDAI ≥10) groups. As shown in Table 2, a comparison of anti-bacterial antibody titers between these 3 groups showed a statistically significant association between increased disease activities with higher anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans antibody (p=0.011) and higher anti-P. gingivalis antibody titers (p=0.0095).

Table 2.

Association of antibodies to periodontal bacteria and disease activity by SLEDAI.

| Bacteria | Antibody titers | SLEDAI SCORES | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | 0–2 | 3–9 | >10 | p value* | |

| A.actino-mycetemcomitans | median | 1618 | 2021# | 2318## | 0.011 |

| range | 17–14520 | 275–21855 | 456–60160 | ||

| (n) | (63) | (184) | (53) | ||

| P. gingivalis | median | 2823 | 3616 | 6062### | 0.0095 |

| range | 525–13550000 | 268–48470 | 225–88350 | ||

| (n) | (62) | (179) | (52) | ||

| T. denticola | median | 7524 | 8505 | 9903 | 0.15 |

| range | 894–94190 | 845–149900 | 1046–172500 | ||

| (n) | (61) | (179) | (51) | ||

| C.ochracea | median | 3929 | 4668 | 4383 | 0.07 |

| range | 943–24030 | 677–122500 | 714–107800 | ||

| (n) | (54) | (160) | (37) | ||

| S.gordonii | median | 9999 | 9848 | 9562 | 0.86 |

| range | 1393–30840 | 1630–45610 | 1826–32980 | ||

| (n) | (62) | (179) | (52) | ||

by Kruskal Wallis test;

p=0.04,

p=0.007,

p=0.0047 by Dunn’s post-test

The anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans antibody titers in patients with the lowest disease activity scores were significantly lower than the patients with moderate (p=0.04) or highest activity (p=0.007). Anti-P. gingivalis antibodies were significantly lower in the patients with lowest disease activity compared to the highest activity scores (p=0.0047).

The British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) index uses different clinical measures for evaluation of disease activity based on individual organ involvement (18). The disease activity in each patient was classified as mild (only C and D organ scores; n=90), moderate (1- or 2- B scores; n=168), and moderately severe to severe (≥3- B or ≥1- A score; n=43). As shown in Table 3, the anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans antibody titers were significantly higher in patients with moderately severe to severe activity compared to the patients with mild disease (p=0.043). A similar trend was seen in anti-P. gingivalis antibody titers, although it failed to reach statistical significance (p=0.056). Associations were not seen between disease activity and antibody titers to T. denticola, C. ochracea or S. gordonii.

Table 3.

Association of antibodies to periodontal bacteria and disease activity by BILAG.

| Bacteria | Antibody titers | TOTAL BILAG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | Mild (C/D) |

Mod. Severe to severe (>3B or >1A) |

p value | |

| A.actino-mycetemcomitans | median | 1794 | 2534 | 0.043 |

| range | 17–16960 | 350–21855 | ||

| (n) | (90) | (43) | ||

| P. gingivalis | median | 3408 | 5026 | 0.056 |

| range | 572–307000 | 307–88350 | ||

| (n) | (90) | (43) | ||

| T. denticola | median | 8066 | 10565 | 0.23 |

| range | 894–149900 | 845–80900 | ||

| (n) | (90) | (42) | ||

| C.ochracea | median | 4197 | 5369 | 0.08 |

| range | 943–122500 | 761–95120 | ||

| (n) | (76) | (35) | ||

| S.gordonii | median | 10012 | 9907 | 0.46 |

| range | 1393–45610 | 3528–25180 | ||

| (n) | (90) | (43) | ||

DISCUSSION

By using banked serum samples from a well characterized cohort of SLE patients, this study demonstrates that high titer of IgG antibodies against the periodontal pathogen A. actinomycetemcomitans was significantly associated with higher disease activity in SLE patients. Considered together with previous reports investigating the association between periodontal disease and lupus (20–23), our study supports the notion that bacterial infections in the subgingival mucosa modulate SLE.

In this study we used the presence of circulating anti-bacterial antibodies as evidence for exposure to the bacteria. This strategy is well established and antibody titers against bacteria from the subgingival plaque have been used as indicators for exposure to and burden of specific bacteria (13–16). A recent study showed a strong correlation between the detection of antibodies to A. actinomycetemcomitans and its leukotoxin with the presence of A. actinomycetemcomitans in the sub-gingival isolates from individual patients (24). Further, anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans and anti-P. gingivalis antibody titers reflecting exposure to those bacteria are known to persist for 15 years (25). A similar clinical observation was also made in another study where elevated titers of anti-P. gingivalis antibodies persisted when monitored for 24 months even when the disease was inactive (26). Thus, detecting high titer of antibodies against organisms associated with periodontitis in our cohort of SLE patients suggests that the patients immune system was exposed to these oral pathogens.

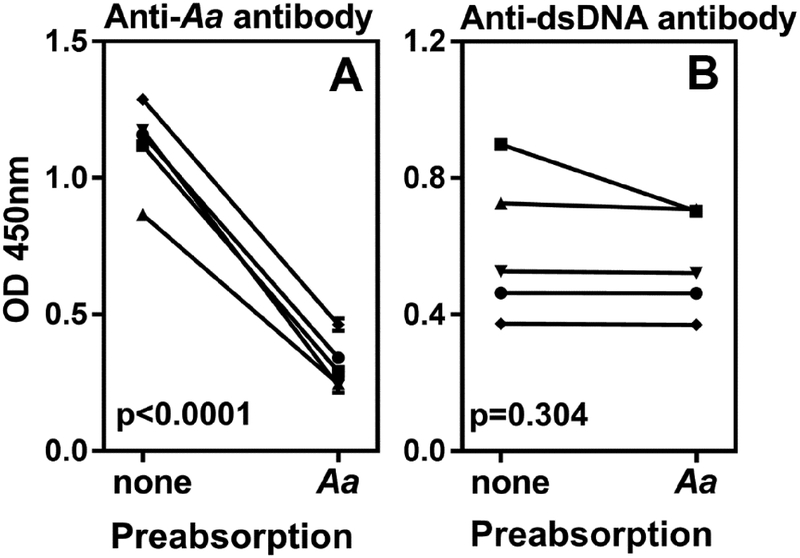

The presence of anti-dsDNA antibody is a hallmark of SLE, and it showed strongest correlation with anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans. Although the precise specificity of anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans antibodies is not known, they do not appear to cross-react with the DNA. While absorption of anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans IgG with A. actinomycetemcomitans significantly reduced anti-bacterial reactivity, it failed to reduce dsDNA reactivity (Figure 2). These data suggest that the A. actinomycetemcomitans mediated periodontal disease process might be contributing towards amplifying anti-dsDNA in SLE patients. This is highly plausible considering the study by Konig et al which implicates A. actinomycetemcomitans as a trigger for rheumatoid arthritis (24).

Figure 2: Limited cross reactivity between anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans and anti-dsDNA antibodies in SLE patients.

IgG purified from five SLE patients were pre-absorbed with A. actinomycetemcomitans, and the residual antibodies to A. actinomycetemcomitans (A) and dsDNA (B) were measured by ELISA. Sera not pre-absorbed with A. actinomycetemcomitans were used as controls. Each line connects control and A. actinomycetemcomitans absorbed serum for the same patient. p values were calculated by paired t test.

We had previously reported that bacterial proteins from oral commensal bacteria, specifically C. ochracea were capable of activating T cells reactive with the Sjogren and lupus associated autoantigen, SSA/Ro60. Therefore, the lack of association between antibodies to periodontal bacteria and SSA and SSB was a surprising result. Since SSA and/or SSB antibody positivity was significantly associated with the history of sicca or dry mouth in our lupus patients (p=0.015, n=299), anti-bacterial antibodies were compared between patients with or without sicca. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, anti-bacteria antibody titers between patients with or without sicca were not significant. These results support previous literature showing lack of association between clinical and microbiologic parameters of periodontal disease and Sjögren’s syndrome, a disease characterized by reduced saliva production and progressive loss of salivary gland function (27–29). In contrast to periodontal disease, lack of saliva has been found to be strongly associated with dental caries and supra-gingival bacteria, which are distinct from the periodontal bacterial populations (30).

Our clinical analyses showed a significant association between higher anti-A. actinomycetemcomitans antibody titers and increased disease activity with both SLEDAI and BILAG indices. Higher anti-P. gingivalis antibody titers were also strongly associated with higher SLEDAI scores. Anti-dsDNA antibodies are a scoring criterion for SLEDAI, and multivariate analyses showed that the SLEDAI association with anti-P. gingivalis antibodies was significantly driven by anti-dsDNA positivity. However, this fails to explain the trend between higher P. gingivalis antibodies and higher BILAG indices. Further, despite the comparable association of anti-T. denticola antibodies with higher anti-dsDNA as well as, C3 and C4 complement depletion (Supplementary Figure 2), there was a lack of association between anti-T. denticola antibodies and either measure of disease activity. An important factor to consider is that the BILAG and SLEDAI are very different kinds of measurement. While SLEDAI scores are more affected by global increases in disease activity, the BILAG index is more sensitive and fluctuates with changes even in an individual manifestation of the disease. Taken together, these results suggest the need for additional studies to investigate the contribution of exposure to P. gingivalis in SLE. The present study suggests that the relationship between SLE and periodontal disease is defined by the specific pathogen, A. actinomycetemcomitans driving the periodontal disease.

A unique characteristic of A. actinomycetemcomitans is their ability to induce citrullination of host proteins. A recent report showed that Leukotoxin A, an exotoxin produced by A. actinomycetemcomitans, induces permiabilization of the cell plasma membranes leading to an unregulated influx of calcium in toxin susceptible cells (24, 31). This activates the endogenous protein arginine deiminase (PAD) enzymes in the cytosol (PAD2) and the nucleus (PAD4) and causes hypercitrullination of self-proteins, which in neutrophils, leads to cell death. Thus, exposure to A. actinomycetemcomitans and not the other periodontal pathogens in lupus patients holds the potential to amplify a pathogenic autoimmune response through the release of modified self-antigens.

This is a cross sectional study, and therefore it does not allow us to postulate causal associations between periodontal bacterial exposure and SLE. Further, in a study of this size, the heterogeneous medications given to the patients, and the lack of this information prevents the ability to make proper adjustments of data for treatment. It is possible that immune modulators may influence periodontal bacteria, and future studies with medication controlled protocols will be helpful. The sera were obtained from samples banked over an extended period of time and therefore, retroactive dental information and periodontal health in the patient and control populations were not available. This lack of data precluded the ability to set cut-offs for pathogenic anti-bacterial antibody positivity since it is possible that the non-SLE controls were also exposed to some of these bacteria (Supplementary Figure 3). Despite these limitations, our data suggest an association between exposure to specific periodontal pathogens and lupus disease activity in SLE patients. Previous studies show a higher incidence of periodontal disease in SLE patients (20, 21). Taken together, all these studies confirm the interaction between periodontal disease and SLE, and specifically, suggest a role for gingival bacterial infections as a factor for increasing morbidity in SLE.

An interesting clinical study in SLE patients (n=49) showed that aggressive treatment of periodontitis resulted in a significant improvement in the responses to lupus therapy (23). This report complements our finding of higher lupus activity in patients with potential exposure to specific bacteria. Prevention of periodontal disease and management of periodontal health have been advocated as simple tools for reducing morbidity in debilitating systemic disease states (32). Our study provides support for conducting systematic clinical investigations into periodontal disease in SLE and a rationale for aggressive management of periodontal health in SLE patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The assistance from Mr. Stan Kamp and Ms. Louise Williamson in compiling and submitting this manuscript is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by grants from the Oklahoma Center for the Advancement of Science and Technology (HR15–145), and the National Institutes of Health (P30GM110766, U54GM104938, P30AR053483, P30GM103510, U19AI082714, and U01AI101934).

REFERENCES

- 1.KAUL A, GORDON C, CROW MK et al. : Systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016; 2: 16039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BOGDANOS DP, SMYK DS, RIGOPOULOU EI, SAKKAS LI, SHOENFELD Y: Infectomics and autoinfectomics: a tool to study infectious-induced autoimmunity. Lupus. 2015; 24: 364–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.KIVITY S, AGMON-LEVIN N, BLANK M, SHOENFELD Y: Infections and autoimmunity--friends or foes? Trends Immunol. 2009; 30:409–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AGMON-LEVIN N, DAGAN A, PERI Y et al. : The interaction between anti-Ro/SSA and anti-La/SSB autoantibodies and anti-infectious antibodies in a wide spectrum of auto-immune diseases: another angle of the autoimmune mosaic. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017; 35:929–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.POOLE BD, SCOFIELD RH, HARLEY JB, JAMES JA: Epstein-Barr virus and molecular mimicry in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2006; 39: 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DOATY S, AGRAWAL H, BAUER E, FURST DE: Infection and Lupus: Which Causes Which? Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2016; 18:13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.RYDER MI: Comparison of neutrophil functions in aggressive and chronic periodontitis. Periodontol 2000. 2010; 53: 124–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.YEW HS, CHAMBERS ST, ROBERTS SA, et al. : Association between HACEK bacteraemia and endocarditis. J Med Microbiol. 2014; 63: 892–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MEYER DH, LIPPMANN JE, FIVES-TAYLOR PM: Invasion of epithelial cells by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: a dynamic, multistep process. Infect Immun. 1996; 64: 2988–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SZYMULA A, ROSENTHAL J, SZCZERBA BM, BAGAVANT H, FU SM, DESHMUKH US: T cell epitope mimicry between Sjögren’s syndrome Antigen A (SSA)/Ro60 and oral, gut, skin and vaginal bacteria. Clin Immunol. 2014; 152: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.RUTTER-LOCHER Z, SMITH TO, GILES I, SOFAT N: Association between Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Periodontitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Front Immunol. 2017; 8: 1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.CORRÊA JD, CALDERARO DC, FERREIRA GA, et al. : Subgingival microbiota dysbiosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: association with periodontal status. Microbiome. 2017; 5: 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.PAPAPANOU PN, NEIDERUD AM, DISICK E, LALLA E, MILLER GC, DAHLÉN G: Longitudinal stability of serum immunoglobulin G responses to periodontal bacteria. J Clin Periodontol. 2004; 31: 985–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CUNNINGHAM LL, NOVAK MJ, MADSEN M, ABADI B, EBERSOLE JL: A bidirectional relationship of oral-systemic responses: observations of systemic host responses in patients after full-mouth extractions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2014; 117: 435–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.KUDO C, NARUISHI K, MAEDA H, et al. : Assessment of the plasma/serum IgG test to screen for periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2012; 91: 1190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DYE BA, HERRERA-ABREU M, LERCHE-SEHM J, et al. : Serum antibodies to periodontal bacteria as diagnostic markers of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009; 80: 634–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.PETRI M, KIM MY, KALUNIAN KC, et al. : Combined oral contraceptives in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353: 2550–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.YEE CS, FAREWELL V, ISENBERG DA, et al. : Revised British Isles Lupus Assessment Group 2004 index: a reliable tool for assessment of systemic lupus erythematosus activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2006; 54: 3300–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CRAIG RG, BOYLAN R, YIP J, et al. : Serum IgG antibody response to periodontal pathogens in minority populations: relationship to periodontal disease status and progression. J Periodontal Res. 2002; 37: 132–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.RHODUS NL, JOHNSON DK: The prevalence of oral manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Quintessence Int. 1990; 21: 461–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.FERNANDES EG, SAVIOLI C, SIQUEIRA JT, SILVA CA: Oral health and the masticatory system in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2007; 16: 713–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.TIETMANN C, BISSADA NF: Aggressive periodontitis in a patient with chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a case report. Quintessence Int. 2006; 37: 401–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.FABBRI C, FULLER R, BONFÁ E, GUEDES LK, D’ALLEVA PS, BORBA EF: Periodontitis treatment improves systemic lupus erythematosus response to immunosuppressive therapy. Clin Rheumatol. 2014; 33: 505–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.KONIG MF, ABUSLEME L, REINHOLDT J, et al. : Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans-induced hypercitrullination links periodontal infection to autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2016; 8: 369ra176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LAKIO L, ANTINHEIMO J, PAJU S, BUHLIN K, PUSSINEN PJ, ALFTHAN G: Tracking of plasma antibodies against Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis during 15 years. J Oral Microbiol. 2009; 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.EBERSOLE JL, CAPPELLI D, STEFFEN MJ: Characteristics and utilization of antibody measurements in clinical studies of periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 1992; 63: 1110–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.KURU B, MCCULLOUGH MJ, YILMAZ S, PORTER SR: Clinical and microbiological studies of periodontal disease in Sjögren syndrome patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2002; 29: 92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LUGONJA B, YEO L, MILWARD MR, et al. : Periodontitis prevalence and serum antibody reactivity to periodontal bacteria in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a pilot study. J Clin Periodontol. 2016; 43: 26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DE GOÉS SOARES L, ROCHA RL, BAGORDAKIS E, GALVÃO EL, DOUGLAS-DE-OLIVEIRA DW, FALCI SGM. Relationship between sjögren syndrome and periodontal status: A systematic review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2018;125: 223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LE GALL M, CORNEC D, PERS JO, et al. : A prospective evaluation of dental and periodontal status in patients with suspected Sjögren’s syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2016; 83: 235–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.KONIG MF, ANDRADE F: A Critical Reappraisal of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps and NETosis Mimics Based on Differential Requirements for Protein Citrullination. Front Immunol. 2016; 7: 461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.CULLINAN MP, SEYMOUR GJ: Periodontal disease and systemic illness: will the evidence ever be enough? Periodontol 2000. 2013; 62: 271–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.