Abstract

Neurology and psychiatry share common historical origins and rely on similar tools to study brain disorders. Yet, the practical integration of medical and scientific approaches across these clinical neurosciences has remained elusive. While much has been written about the need to incorporate emerging systems-level, cellular-molecular and genetic-epigenetic advances into a science of mind for psychiatric disorders, less attention has been given to applying clinical neuroscience principles to conceptualize neurologic conditions using an integrated neurobio-psycho-social approach. In this perspective article, we first briefly outline the historically interwoven and complicated relationship between neurology and psychiatry. Through a series of vignettes, we then illustrate how some traditional psychiatric conditions are being re-conceptualized in part as disorders of neurodevelopment and awareness. The intersection of neurology and psychiatry is further emphasized by highlighting conditions that cut across traditional diagnostic boundaries. We argue that the divide between neurology and psychiatry can be narrowed by moving from lesion-based toward circuit-based understandings of neuropsychiatric disorders, from unidirectional toward bidirectional models of brain-behavior relationships, from exclusive reliance on categorical diagnoses toward trans-diagnostic dimensional perspectives, and from silo-based research and treatments towards interdisciplinary approaches. The time is now ripe for neurologists and psychiatrists to implement an integrated clinical neuroscience approach to the assessment and management of brain disorders. The subspecialty of Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry is poised to lead the next generation of clinicians to merge brain science with psychological and social-cultural factors. These efforts will catalyze translational research, revitalize training programs, and advance the development of impactful patient-centered treatments.

Keywords: clinical neuroscience, education, brain-behavior relationships, behavioral neurology, neuropsychiatry

Introduction

“In the last analysis, we see only what we are ready to see, what we have been taught to see. We eliminate and ignore everything that is not a part of our practices.” Jean-Martin Charcot 1825–1893.

While most organs have one dedicated medical specialty, the brain has been historically divided into two disciplines, neurology and psychiatry{1, 2}. Neurology and psychiatry have been separated by theory, domains of investigation, vocabulary, and interventions. This separation has led to a lack of a shared nomenclature and, at times, different diagnostic criteria for the same disorder. Traditional terms such as “psychogenic” and “organic” perpetuate an artificial dualism. Despite recent appeals by the Nobel laureate Eric Kandel{3}, prominent academics{4–8}, and leaders of the National Institute of Health in the United States{9}, “closing the great divide” between neurology and psychiatry remains elusive{10}. Furthermore, at times the distinction between neurologic and psychiatric disorders appears arbitrary, as some disorders with well-established neurobiological foundations including schizophrenia are almost exclusively reported on in the psychiatric literature and other conditions with prominent affective and behavioral phenotypes such as Huntington’s disease and behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia are predominantly characterized in the neurologic literature{11}.

Paradigm shifts in science, as well as clinical need for a convergence between neurology and psychiatry, are based on the unprecedented expansion of our emerging neurobiological knowledge of complex mental operations. Increasing evidence blurs the boundaries between neurologic and psychiatric disorders, which includes growth in network science and genomics, as well as the realization that many brain disorders are not due to detectable “lesions” but originate from dysfunction across broadly-distributed networks. Furthermore, there is increasing recognition that the causes of many brain disorders are multifactorial and bi-directional in nature. For example, psychosocial (environmental) factors alter neurocircuits and maladaptive neural function impairs psychosocial behaviors{12}. These factors, in addition to an aging population, are driving the need for a renaissance, one that necessitates the development of specialists who can trans-diagnostically care for patients with complex brain disorders{13}.

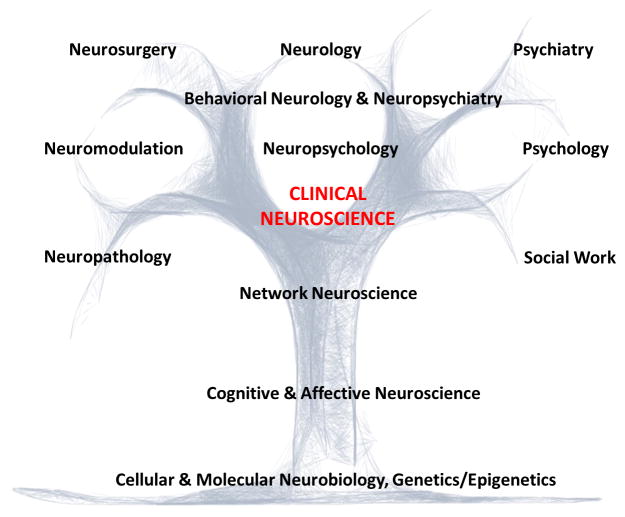

In this perspective article, we present four vignettes illustrating how advances in clinical neuroscience are eroding the traditional boundaries separating the disciplines of neurology and psychiatry. Schizophrenia is presented as a neurodevelopmental disorder, functional neurological disorder (FND) as a disturbance of awareness, Tourette syndrome (TS), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder (ADHD) as heritable disorders of overlapping, dysregulated circuits with inter-related motor-cognitive-affective components, and post-stroke neuropsychiatric symptoms as impairments in distributed networks. These examples illustrate a practical clinical neuroscience approach that incorporates neurobio-psycho-social elements. Thereafter, we discuss core themes that can help move neurology and psychiatry towards a more integrated clinical and research approach. Emphasis is given to identifying steps neurologists can take to incorporate psychiatric and psychosocial factors, facilitating an interdisciplinary approach to patient care. The subspecialty of Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry is well-positioned to catalyze these transformations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An Integrated Clinical Neuroscience Approach for the Assessment, Management and Investigation of Brain Disease.

Schizophrenia

Case Description

A 24 year-old African American woman was brought by her parents to clinic. In childhood, she had concentration difficulties and was diagnosed with ADHD. Two of her maternal aunts had schizophrenia and her brother had bipolar disorder. Her parents divorced when the patient was a teenager. Since junior high school she began displaying gradual social withdrawal, declining grades, cannabis use, worries that her classmates might be spreading evil rumors about her homosexuality, and reported occasional whispers saying such things (though she was uncertain if these perceptions were real). During her first semester in college, she faced academic pressures and began experiencing “internal chatter” by two voices that kept a running commentary on her actions. She was now convinced that these voices were real and resulted from a chip implanted in her teeth by a classmate. She confronted and assaulted this classmate, leading to an involuntary hospitalization.

Five years later, she continued experiencing auditory hallucinations, was unemployed, and mostly spent time in her basement. She displayed disorganized speech, disinhibited behavior, reduced motivation, poor personal hygiene and remained unconvinced about the need for medications.

This case illustrates the trajectory of schizophrenia with subtle premorbid cognitive impairments in childhood, followed by a prodrome with gradual social and functional decline in adolescence. Psychosis typically sets in during late adolescence or adulthood and follows a chronic or intermittent course. Regarding pathogenesis, it is now widely held that schizophrenia is due to either a failure of optimal brain development, an abnormal refinement of pruning of synapses during adolescence, or both{14}. The neuroanatomy of schizophrenia is increasingly well understood; impaired executive functions, poor insight and disinhibited behavior point to deficits in dorsolateral and ventromedial prefrontal cortex respectively, termed previously as “hypofrontality”. Hallucinations and delusions are thought to relate to inappropriate subcortical activations including in the hippocampus{15}. Formal thought disorder is linked to abnormal functioning of language circuits{16}. In terms of neurochemical pathophysiology, ventral striatal and mesolimbic dopaminergic abnormalities likely underlie positive psychotic symptoms, while recent data implicate mesocortical dopaminergic deficits and altered glutamatergic and GABA function as mediating cognitive and negative symptoms{17}. Finally, as to etiology, there is compelling evidence that genetic factors, including genes mediating synapse integrity, ion channels and immune function, are implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia; environmental and epigenetic risk factors are also involved{18}.

Clearly, this woman is suffering from a progressive developmental derailment beginning in childhood, perhaps resulting from a combination of genetic and environmental (cannabis) risk factors, leading to chronic network alterations in several key prefrontal, limbic and superior temporal “nodes”, and multiple neurotransmitter aberrations. A neurobio-psycho-social formulation in her case would also include roles for parental discord and academic stress framed as predisposing and precipitating factors{19}. Such a formulation would not only incorporate a common language for both psychiatrists and neurologists, but would also point to actionable treatments and research initiatives. The neurodevelopmental pathogenesis and premorbid/prodromal impairments including cognitive decline point to a role for early interventions.

A cognitive test battery and neuroimaging biomarkers may identify a subtype of psychosis characterized primarily by cognitive dysfunction, and one that could point to a role for time-intensive cognitive rehabilitation{20}. Delineation of distinct networks underlying negative/depressive symptoms, cognitive deficits and positive symptoms can point to personalized treatments such as cognitive remediation{21}, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT){22}, psychopharmacology, and neuromodulation{23}.

FND

Case Description

A 30 year-old single, unemployed Hispanic woman with a history of medically-unexplained neck pain and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following childhood abuse abruptly developed episodes of decreased arousal with asynchronous side-to-side body movements. She also experienced clouded thinking, difficulty walking, and a sense that her legs collapsed. She was hospitalized and her examination showed a variable/distractible head tremor and a positive right Hoover’s sign. A typical spell was captured on video-electroencephalography without electrographic correlate. She was referred for physical therapy but developed full-body shaking on attempted gait and elected against additional sessions. She did not show up for her outpatient psychiatry appointment, and the patient and family members had difficulty understanding how this could be “all in the patient’s head”.

Based on emerging neuroimaging findings, the patient’s symptoms of non-epileptic seizures (NES), functional limb weakness, chronic pain, affective dysregulation and cognitive complaints may be partially localized to networks mediating multimodal sensory-motor, affective, cognitive, and perceptual integration including the anterior insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), amygdala, and temporoparietal junction{24–32}. Patients with FND show dorsal ACC structural alterations compared to controls{32, 33}, and individuals with medically-unexplained pain display central pain matrix volumetric reductions{34}. Parallel inverse associations between left anterior insular gray matter volume and self-report measures of symptom severity and childhood abuse burden have also been recently reported in FND{29, 31}. In addition, resting-state functional connectivity studies in FND display heightened connectivity between limbic/paralimbic areas (ACC, insula, amygdala) and somatomotor/executive control networks{35–38}. Increased paralimbic-supplementary motor area (SMA) functional connectivity has also correlated with NES frequency{36, 37}. While cingulo-insular abnormalities may pertain to impaired emotional awareness/regulation, aberrant viscero-somatic processing, and heightened affective influence over motor behaviors, right temporo-parietal junction functional alterations in FND have been linked to motor intention awareness and action-authorship recognition deficits{26, 39–41}.

Although there are multiple predisposing vulnerabilities for FND, over 50% of individuals with NES endorse traumatic experiences and childhood abuse is associated with increased symptom severity{42, 43}. Large-scale studies in healthy subjects identify links between adverse life events and reduced ACC, insular, hippocampal, orbitofrontal cortex, and caudate volumes{44–46}. Associations between the magnitude of childhood trauma and heightened amygdalar activations during affective processing have also been reported in healthy subjects{44}, and task fMRI studies in FND consistently report increased amygdalar activations across several affectively valenced paradigms{27, 47–49}. These findings highlight a potential convergence between trauma-mediated aberrant neuroplasticity and FND.

An understanding of the emerging neurobiology of FND reduces stigma and helps guide delivery of the diagnosis{50, 51}. Providing a brain-based model of FND, along with presenting the diagnosis as genuine and common, is an effective communication strategy. An appreciation of the neurobiology of FND may, in our opinion, increase the comfort of neurologists who feel that they are placed in the awkward position of sitting in the psychiatrists’ chair{52}. Furthermore, effective delivery of the diagnosis comes with the pre-requisite of having at least a basic understanding of FND treatments, which include physical/occupational therapy{53} and CBT{54}. The ability for clinicians to evaluate maladaptive behaviors (i.e. avoidance) and listen for unhelpful thought patterns (i.e. “I will never get better”) are important aspects of the assessment. Thus, clinicians should receive training in the assessment of psychological and psychosocial factors that may be predisposing, precipitating or perpetuating a patient’s illness.

TS, OCD and ADHD

Case Description

An 11 year-old girl presented with motor and vocal tics. A few days prior to her 9th birthday, she developed repetitive bursts of eye-blinking and sniffing that waxed and waned, and were briefly suppressible. She subsequently experienced recurrent facial grimacing, shoulder shrugs, coughing, spitting and a need to tense her forearm muscles the same number of times on each side of her body. Six months prior to evaluation, she developed forceful backward head jerks and eye rolling to the side that would continue for hours. The tics did not respond to alpha-2 agonists or atypical neuroleptics.

Her birth and developmental history were unremarkable, though at age 6 she began to repeatedly check light switches before leaving the house causing her to arrive late for school. In third grade, she struggled with homework and finishing timed tests. Inspection of her schoolwork revealed neatly formed letters and numbers with multiple erasure marks to the point of leaving holes in the paper. She also had frequent anger outbursts. This patient was followed clinically, and her symptoms improved by early adulthood.

This individual’s symptom complex is characteristic of TS. Greater than 85% of TS patients have one or more co-morbidities{55, 56}, most frequently OCD and ADHD. Notably, these other symptoms are often more impairing than the motor and vocal tics{57, 58}. Given the significant clinical overlap between these traditional “neurologic” and “psychiatric” disorders, patients can easily “fall through the cracks”. In contrast, genetic{59–61}, neuroimaging{62}, and neurophysiologic studies{63} have demonstrated that TS, as well as OCD and ADHD that present in the context of tics, are not distinct disorders, but instead arise from common neurodevelopmental abnormalities of parallel cortical-striatal-thalamo-cortical circuits regulating initiation, selection, execution, learning and reinforcement of intended movements, thoughts, behaviors and moods{64, 65}.

The patient in this case had arm tensing tics that required her to perform tics a specific number of times on each side of her body. Many complex tics have a compulsive component, in particular a need for “evening up” as well as a need to repeat tics until they feel “just right”{66}. These compulsive tics are often accompanied by additional OCD symptoms of checking, ordering/arranging, and symmetry obsessions/compulsions{67}. Biologically, symmetry OCD symptoms correlate more strongly with aggregated TS polygenic risk rather than with OCD polygenic risk{68}. One neuroimaging study demonstrated that symmetry OCD symptom provocation in TS patients resulted in increased cerebral blood flow within the orbitofrontal cortex and SMA, representing brain regions considered to be part of OCD and TS circuitry, respectively{69}. This genetic and neurobiological overlap between tics and OCD is not just of academic interest, since OCD symptoms in those with tics are more likely to be refractory to selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and may require neuroleptics{70}. Additional questioning about triggers for her violent head jerks and eye rolling tics revealed a need to look up and behind her at the corner of the ceiling until her eyes lined up “just right”. SSRI augmentation with risperidone markedly reduced both head jerking and eye rolling, further blurring the distinctions between tics and compulsions.

This individual also had executive dysfunction consistent with ADHD. However, her scholastic difficulties on timed tests proved to be driven by writing/rewriting compulsions that responded to a combination of an SSRI and CBT. Her anger outbursts can be partially attributed to impaired impulse control{58, 71}. However, functional analysis demonstrated that her frustration tolerance was lowest during periods of severe tics, fatigue, and interruption of her checking compulsions. In addition to behavioral therapy for tics{72, 73} and CBT for OCD and anger symptoms, psycho-education of her siblings and family therapy were key components of treatment. Lastly, longitudinal care and prognostic discussions require consideration of developmental trajectories, given that this patient improved as she neared adulthood which is common in TS{74}.

Post-Stroke Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

Case Description

A 17 year-old boy with migraine headaches was driving when he perceived his eyes acting “like a zoom lens, going in and out of focus.” He then experienced the roadside scenery as if it had been “drawn in with crayon,” with cartoon figures on the sidewalk. After parking his car and reaching for his jacket, he saw flowers sprout from the jacket and topple over as he picked it up. He retained insight throughout that the visual imagery was hallucinatory in nature, and was brought to an emergency room where a head computed tomography and toxicology screen were normal. A brain MRI revealed a small acute central thalamic infarct in the left centromedian\ parafascicular region and several risk factors for stroke were discovered{75}.

This individual had peduncular hallucinosis, which involves visual hallucinations, often cartoon-like, experienced in the setting of focal thalamic or brainstem lesions{76}. Insight is typically preserved which differs from hallucinations in idiopathic psychotic disorders. The causative lesions in peduncular hallucinosis are varied but localize to a common intrinsically correlated functional network that is positively connected with the lateral geniculate nucleus and negatively associated with the extrastriate visual cortex{75}. Lesions that cause peduncular hallucinosis alter the network dynamics at these remote sites{77} and may increase the probability of experiencing visual hallucinations.

Cases in which a specific neuropsychiatric symptom is linked to a focal brain lesion offer a promising avenue of research for gaining neurobiological insights. While there is a long tradition of mapping lesion location relative to cognitive and behavioral deficits, there are a variety of recent advances in lesion analysis{78, 79} that incorporate a network perspective to consider the lesion’s functional consequences{75, 80, 81}. These modern approaches for drawing brain-symptom inferences build upon the strong tradition of lesion mapping and complement other brain mapping initiatives such as the human connectome project{82}. Neurologists and psychiatrists should now discuss neuropsychiatric symptoms in relation to discrete network localizations rather than a primary discussion on focal brain lesions. A better network understanding of brain dysfunction in neuropsychiatric presentations may inform innovative treatments such as imaging-guided neuromodulation{23}.

Neuropsychiatric symptoms following focal brain lesion(s) are common, under-recognized, and under-treated{83}. These patients tend to receive care from neurologists, where the clinical focus is often on identifying the underlying cause of the lesion, addressing modifiable stroke risk factors, and/or treating the underlying disease process (e.g. hypercoagulability). However, affective, perceptual, behavioral, and cognitive symptoms that manifest following an acquired brain lesion may be intimately tied to one’s health-related quality of life. Treating these symptoms can profoundly impact rehabilitation success and life satisfaction. As such, optimal neurologic care for these patients necessitates a comprehensive evaluation beyond sensory-motor and language functions and symptomatic treatments when indicated{84}, including pharmacotherapy, CBT, neuromodulation and psychosocial support.

Discussion

We discuss below themes that can help move neurology and psychiatry towards a more integrated clinical and research approach. Emphasis is given to outlining how neurologists can better assess and treat patients with complex brain disorders by using a neurobio-psycho-social perspective.

From lesion-based toward circuit-based conceptualizations of neurobehavioral/neuropsychiatric symptoms

The absence of clear-cut “lesions” in psychiatric disorders such as major depression has frequently led to neurologists ignoring that affective and other psychiatric disturbances are brain (neurologic) symptoms. The traditional neurologic domains include sensory-motor, visual-spatial, attentional, language, behavioral, memory and executive functions. Lacking is the parallel consideration of affect, mood and thought, and the ways in which affectively-valenced elements of patients’ presentations interact with other neurologic domains of inquiry. The lack of an integration of emotional and thought disturbances in the assessment and management of neurologic disorders is striking given the prevalence of these neuropsychiatric symptoms in cerebrovascular disease{84}, multiple sclerosis{85}, epilepsy{86}, and neurodegenerative disorders among other conditions. For example, in a memory clinic, depression, anxiety and psychosis are both mimics of mild cognitive impairment{87} and potential markers of impending dementia{88}. Furthermore, affective and perceptual impairments in neurologic conditions may become the focus of treatment; for instance, one-third of post-stroke patients develop depression, anxiety and/or apathy and these symptoms reduce quality of life independent of physical limitations{83}.

The circuit-level understanding of the pathophysiology of depression, anxiety and psychosis, while requiring additional clarification, are sufficiently well-understood that dominant neurobiological paradigms have been developed{14, 17, 89–91}. Furthermore, neurocircuits implicated in cognition overlap with those mediating emotion regulation. Importantly, circuit-level formulations of brain-symptom relationships based on emerging neuroscience require continual refinement given a rapidly evolving scientific literature.

From unidirectional toward bidirectional models of brain-behavior relationships

Psychosocial (environmental) factors change the brain and warrant assessment in neurology patients. In our experience supervising neurology residents, we increasingly appreciate that psychosocial factors are given limited importance. Apart from an understanding of inter-personal relationships, educational background and employment status, a developmental and trauma history may elucidate predisposing, precipitating or perpetuating factors for a patient’s symptom complex. For example, adverse early-life events have been linked to increased symptom severity in FND{29, 42, 43}, and can predict co-morbid depression in epilepsy{42}. A longitudinal study also identified that chronic stress accelerates cognitive decline in patients with mild cognitive impairment{92}. Thus, an advanced understanding of brain-symptom and brain-prognosis relationships requires a sophisticated understanding of psychosocial factors at the individual-level.

From categories toward dimensions

A trans-diagnostic, dimensional approach to brain-symptom relationships should be emphasized to create a common language of clinical neuroscience{19}. In our opinion, one of the major barriers to increased integration across neurology and psychiatry, and a move towards improved interdisciplinary care, is that neurologists and psychiatrists do not speak a common clinical language. The National Institute of Mental Health has recently adopted the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), with a major focus on the linking of syndromes and specific symptom dimensions to the underlying pathophysiology{93} while de-emphasizing categorical distinctions. Although the current RDoC system (negative valence, positive valence, cognitive, social, and arousal/regulatory) would require additional domains to comprehensively consider the full spectrum of brain disorders (i.e. viscerosomatic and motor execution/control systems), we believe that when neurologists are discussing lesion localization, the conversation should shift towards localizing the implicated neurocircuit(s) and critical nodes within a circuit that relate to a patient’s symptoms. This would require dialogues focused on deficits in impulse control rather than “personality change” which map more specifically onto discrete neural systems. This is similar to discussions that psychiatrists are now engaged in, which focus not on the biology of major depression, but rather on the pathophysiology of anhedonia, mood modulation and attentional bias which map onto nodes of the ACC-subcortical-limbic circuit including the ventral striatum, subgenual ACC and amygdala{90}.

From silos toward interdisciplinary patient care

Our discussion of the need for a common language in the formulation and assessment of neurologic and psychiatric symptoms does not imply that we are arguing for a complete overlap of the specialized skill sets across the clinical neurosciences. While we feel it is important for neurologists and psychiatrists to preserve their identity, we argue that each group must have a deeper understanding of the clinical aspects performed by the other. This requires, for example, psychiatrists becoming comfortable performing neurologic examinations (particularly since diagnostic criteria for some disorders including FND require identification of “rule in” positive examination findings, and for the accurate assessment of medication side effects (i.e. medication-induced parkinsonism). Similarly, psychotherapy interventions are increasingly utilized in neurologic populations for behavioral, cognitive, affective, and social impairments, as well as to aid an individual’s ability to effectively cope with chronic illnesses. This requires neurologists to have a working knowledge of CBT principles. This is important to facilitate patient engagement, especially since neurologists will most frequently field questions such as “how will psychotherapy help me with my (neurologic) symptoms?.”

Implementing Change and the Path Forward: Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry should lead

In the United States, the fellowship training program for behavioral neurology & neuropsychiatry is an integrated certification program sponsored by the United Council for Neurological Subspecialities{94}. While there are many strengths to combined training (which includes dual neurology-psychiatry training as an alternative), practically this integration allows psychiatrists to develop proficiency in the neurologic examination and use of diagnostic biomarkers, while in parallel allowing neurologists to gain a sophisticated understanding of typical and atypical psychiatric presentations as well as the use of pharmacologic, psychological and behavioral/psychosocial interventions.

In the context of arguing that behavioral neurologists and neuropsychiatrists should play significant clinical teaching and mentoring roles for trainees, we suggest the following initiatives:

Embedding behavioral neurologists and neuropsychiatrists into subspecialty clinics such as movement disorders, epilepsy, cerebrovascular, chronic pain and neuromuscular units, as well as in general psychiatry clinics, would facilitate the implementation of an interdisciplinary clinical neuroscience approach.

The assessment of mood and affect should become an emphasized part of clinical encounters for ALL neurologists, alongside the elemental neurological examination and cognitive testing. Furthermore, the burden is on educators and senior clinicians (including department chairs) to lead by example.

For interdisciplinary models of care to develop, neurologists can no longer be taught only by other neurologists, but rather require hands-on training from other allied disciplines including neuropsychiatrists, psychologists, neuropsychologists, and social workers.

Neurologists should discuss network localizations for mood, affective, and perceptual disturbances, and not limit themselves to sensory-motor, cognitive and behavioral domains. This requires neurologists receive teaching on the neurobiology of arousal, negative emotional processing/regulation, reward processing, salience, and social functioning among other dimensions.

Neurologists need an expanded and more nuanced “toolbox”. Just as a neurologist may choose to selectively perform a Dix-Hallpike maneuver from their diagnostic repertoire only in patients complaining of positional vertigo, clinicians across the aisle should have the ability to perform psychiatric and psychosocial assessments when indicated. Examples include conducting a sensitive exploration of psychosocial trauma, a careful mental status examination to evaluate thought vs. language disorder, and the use of standardized, valid, and reliable cognitive screening tools followed by tests with greater cognitive domain specificity.

Case formulation using a neurobio-psych-social model should be encouraged where appropriate{19}, particularly emphasizing the identification of predisposing vulnerabilities, acute precipitants, and predisposing factors.

The implementation of an interdisciplinary approach to the assessment and management of the full spectrum of brain disorders will decrease the stigma faced by many with mental illness. In addition, important barriers need to be addressed in parallel such as lack of parity in the insurance coverage of mental health care and the separate handling of psychiatric medical records which impede collaborations{8}. Lastly, we need to incentivize trainees in neurology and psychiatry to pursue advanced training in behavioral neurology & neuropsychiatry to develop the next generation of forward-thinking clinical neuroscientists.

Expanding knowledge of the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders and the increased appreciation of affective, behavioral and psychosocial consequences of neurological diseases are eroding boundaries between neurology and psychiatry. Interdisciplinary training between neurology and psychiatry is needed now more than ever before. Embracing a clinical neuroscience approach to patient care and research will revitalize training programs and advance the implementation of collaborative, patient-centered treatments.

Acknowledgments

D.L.P. and B.H.P. received support from the Sidney R. Baer Jr. Foundation, and D.L.P. was funded by the NIMH 1K23MH111983-01A1.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to the concept and design, literature review, drafting of the manuscript and critical review of the manuscript.

Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest

M.S.K., was a one-time consultant at Forum Pharmaceuticals; and is the editor for Schizophrenia Research, an Elsevier Journal. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Price BH, Adams RD, Coyle JT. Neurology and psychiatry: closing the great divide. Neurology. 2000;54:8–14. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham MG, Goldstein M, Katz D, et al. Coalescence of psychiatry, neurology, and neuropsychology: from theory to practice. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2006;14:127–140. doi: 10.1080/10673220600748536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowan WM, Kandel ER. Prospects for neurology and psychiatry. JAMA. 2001;285:594–600. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.5.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silbersweig D. Integrating Models of Neurologic and Psychiatric Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:759–760. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heckers S. Project for a Scientific Psychiatry: Neuroscience Literacy. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:315. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yudofsky SC, Hales RE. Neuropsychiatry and the future of psychiatry and neurology. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1261–1264. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yudofsky SC, Hales RE. Neuropsychiatry: back to the future. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200:193–196. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318247ff81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schildkrout B, Benjamin S, Lauterbach MD. Integrating Neuroscience Knowledge and Neuropsychiatric Skills Into Psychiatry: The Way Forward. Acad Med. 2016;91:650–656. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Insel TR, Landis SC. Twenty-five years of progress: the view from NIMH and NINDS. Neuron. 2013;80:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JB. The integration of neurology, psychiatry, and neuroscience in the 21st century. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:695–704. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Downar J, Blumberger DM, Daskalakis ZJ. The Neural Crossroads of Psychiatric Illness: An Emerging Target for Brain Stimulation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016;20:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nemeroff CB. Paradise Lost: The Neurobiological and Clinical Consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect. Neuron. 2016;89:892–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arambepola NM, Rickards H, Cavanna AE. The evolving discipline and services of neuropsychiatry in the United Kingdom. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2012;24:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5215.2012.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keshavan MS, Giedd J, Lau JY, et al. Changes in the adolescent brain and the pathophysiology of psychotic disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:549–558. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamminga CA, Stan AD, Wagner AD. The hippocampal formation in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1178–1193. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09081187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shenton ME, Kikinis R, Jolesz FA, et al. Abnormalities of the left temporal lobe and thought disorder in schizophrenia. A quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:604–612. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199208273270905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis DA, Moghaddam B. Cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia: convergence of gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate alterations. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1372–1376. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.10.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics C. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511:421–427. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torous J, Stern AP, Padmanabhan JL, et al. A proposed solution to integrating cognitive-affective neuroscience and neuropsychiatry in psychiatry residency training: The time is now. Asian J Psychiatr. 2015;17:116–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clementz BA, Sweeney JA, Hamm JP, et al. Identification of Distinct Psychosis Biotypes Using Brain-Based Biomarkers. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:373–384. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14091200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keshavan MS, Vinogradov S, Rumsey J, et al. Cognitive training in mental disorders: update and future directions. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:510–522. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13081075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rector NA, Beck AT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for schizophrenia: an empirical review. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200:832–839. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31826dd9af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox MD, Buckner RL, Liu H, et al. Resting-state networks link invasive and noninvasive brain stimulation across diverse psychiatric and neurological diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E4367–4375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405003111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shackman AJ, Salomons TV, Slagter HA, et al. The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12:154–167. doi: 10.1038/nrn2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Craig AD. How do you feel--now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:59–70. doi: 10.1038/nrn2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maurer CW, LaFaver K, Ameli R, et al. Impaired self-agency in functional movement disorders: A resting-state fMRI study. Neurology. 2016;87:564–70. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aybek S, Nicholson TR, O’Daly O, et al. Emotion-motion interactions in conversion disorder: an FMRI study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aybek S, Nicholson TR, Zelaya F, et al. Neural correlates of recall of life events in conversion disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:52–60. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perez DL, Matin N, Barsky A, et al. Cingulo-Insular Structural Alterations Associated with Psychogenic Symptoms, Childhood Abuse and PTSD in Functional Neurological Disorders. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2017;88:491–497. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-314998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voon V, Cavanna AE, Coburn K, et al. Functional Neuroanatomy and Neurophysiology of Functional Neurological Disorders (Conversion Disorder) J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28:168–190. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.14090217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perez DL, Williams B, Matin N, et al. Corticolimbic structural alterations linked to health status and trait anxiety in functional neurological disorder. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:1052–1059. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2017-316359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez DL, Matin N, Williams B, et al. Cortical thickness alterations linked to somatoform and psychological dissociation in functional neurological disorders. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018;39:428–439. doi: 10.1002/hbm.23853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Labate A, Cerasa A, Mula M, et al. Neuroanatomic correlates of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a cortical thickness and VBM study. Epilepsia. 2011;53:377–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perez DL, Barsky AJ, Vago DR, et al. A neural circuit framework for somatosensory amplification in somatoform disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;27:e40–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13070170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Kruijs SJ, Bodde NM, Vaessen MJ, et al. Functional connectivity of dissociation in patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83:239–247. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-300776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li R, Li Y, An D, et al. Altered regional activity and inter-regional functional connectivity in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11635. doi: 10.1038/srep11635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li R, Liu K, Ma X, et al. Altered Functional Connectivity Patterns of the Insular Subregions in Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures. Brain Topogr. 2015;28:636–645. doi: 10.1007/s10548-014-0413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wegrzyk J, Kebets V, Richiardi J, et al. Identifying motor functional neurological disorder using resting-state functional connectivity. Neuroimage Clin. 2018;17:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voon V, Gallea C, Hattori N, et al. The involuntary nature of conversion disorder. Neurology. 2010;74:223–228. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ca00e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baek K, Donamayor N, Morris LS, et al. Impaired awareness of motor intention in functional neurological disorder: implications for voluntary and functional movement. Psychol Med. 2017:1–13. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arthuis M, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Bartolomei F, et al. Resting cortical PET metabolic changes in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:1106–1112. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Selkirk M, Duncan R, Oto M, et al. Clinical differences between patients with nonepileptic seizures who report antecedent sexual abuse and those who do not. Epilepsia. 2008;49:1446–1450. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roelofs K, Keijsers GP, Hoogduin KA, et al. Childhood abuse in patients with conversion disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1908–1913. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dannlowski U, Stuhrmann A, Beutelmann V, et al. Limbic scars: long-term consequences of childhood maltreatment revealed by functional and structural magnetic resonance imaging. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;71:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ansell EB, Rando K, Tuit K, et al. Cumulative adversity and smaller gray matter volume in medial prefrontal, anterior cingulate, and insula regions. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen RA, Grieve S, Hoth KF, et al. Early life stress and morphometry of the adult anterior cingulate cortex and caudate nuclei. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:975–982. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voon V, Brezing C, Gallea C, et al. Emotional stimuli and motor conversion disorder. Brain. 2010;133:1526–1536. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morris LS, To B, Baek K, et al. Disrupted avoidance learning in functional neurological disorder: Implications for harm avoidance theories. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;16:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hassa T, Sebastian A, Liepert J, et al. Symptom-specific amygdala hyperactivity modulates motor control network in conversion disorder. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2017;15:143–150. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.LaFrance WC, Jr, Reuber M, Goldstein LH. Management of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2013;54(Suppl 1):53–67. doi: 10.1111/epi.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carson A, Lehn A, Ludwig L, et al. Explaining functional disorders in the neurology clinic: a photo story. Pract Neurol. 2016;16:56–61. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kanaan R, Armstrong D, Barnes P, et al. In the psychiatrist’s chair: how neurologists understand conversion disorder. Brain. 2009;132:2889–2896. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nielsen G, Stone J, Matthews A, et al. Physiotherapy for functional motor disorders: a consensus recommendation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:1113–1119. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.LaFrance WC, Jr, Baird GL, Barry JJ, et al. Multicenter pilot treatment trial for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:997–1005. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hirschtritt ME, Lee PC, Pauls DL, et al. Lifetime prevalence, age of risk, and genetic relationships of comorbid psychiatric disorders in Tourette syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:325–333. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Freeman RD, Fast DK, Burd L, et al. An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: selected findings from 3,500 individuals in 22 countries. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:436–447. doi: 10.1017/s0012162200000839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gorman DA, Thompson N, Plessen KJ, et al. Psychosocial outcome and psychiatric comorbidity in older adolescents with Tourette syndrome: controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197:36–44. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.071050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sukhodolsky DG, Scahill L, Zhang H, et al. Disruptive behavior in children with Tourette’s syndrome: association with ADHD comorbidity, tic severity, and functional impairment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42:98–105. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200301000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yu D, Mathews CA, Scharf JM, et al. Cross-Disorder Genome-Wide Analyses Suggest a Complex Genetic Relationship Between Tourette’s Syndrome and OCD. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:82–93. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davis LK, Yu D, Keenan CL, et al. Partitioning the heritability of Tourette syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorder reveals differences in genetic architecture. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, et al. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. bioRxiv. 2016 doi: 10.1126/science.aap8757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Worbe Y, Gerardin E, Hartmann A, et al. Distinct structural changes underpin clinical phenotypes in patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome. Brain. 2010;133:3649–3660. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gilbert DL, Bansal AS, Sethuraman G, et al. Association of cortical disinhibition with tic, ADHD, and OCD severity in Tourette syndrome. Mov Disord. 2004;19:416–425. doi: 10.1002/mds.20044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alexander GE, DeLong MR, Strick PL. Parallel organization of functionally segregated circuits linking basal ganglia and cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1986;9:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.09.030186.002041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jahanshahi M, Obeso I, Rothwell JC, et al. A fronto-striato-subthalamic-pallidal network for goal-directed and habitual inhibition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:719–732. doi: 10.1038/nrn4038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Leckman JF, Walker DE, Goodman WK, et al. “Just right” perceptions associated with compulsive behavior in Tourette’s syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:675–680. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Worbe Y, Mallet L, Golmard JL, et al. Repetitive behaviours in patients with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome: tics, compulsions, or both? PLoS One. 2010;5:e12959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Darrow SM, Hirschtritt ME, Davis LK, et al. Identification of Two Heritable Cross-Disorder Endophenotypes for Tourette Syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174:387–396. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16020240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.de Vries FE, van den Heuvel OA, Cath DC, et al. Limbic and motor circuits involved in symmetry behavior in Tourette’s syndrome. CNS Spectr. 2013;18:34–42. doi: 10.1017/S1092852912000703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bloch MH, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Kelmendi B, et al. A systematic review: antipsychotic augmentation with treatment refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:622–632. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Budman CL, Bruun RD, Park KS, et al. Explosive outbursts in children with Tourette’s disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:1270–1276. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Piacentini J, Woods DW, Scahill L, et al. Behavior therapy for children with Tourette disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1929–1937. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wilhelm S, Peterson AL, Piacentini J, et al. Randomized trial of behavior therapy for adults with Tourette syndrome. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:795–803. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hassan N, Cavanna AE. The prognosis of Tourette syndrome: implications for clinical practice. Funct Neurol. 2012;27:23–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boes AD, Prasad S, Liu H, et al. Network localization of neurological symptoms from focal brain lesions. Brain. 2015;138:3061–3075. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manford M, Andermann F. Complex visual hallucinations. Clinical and neurobiological insights. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 10):1819–1840. doi: 10.1093/brain/121.10.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geddes MR, Tie Y, Gabrieli JD, et al. Altered functional connectivity in lesional peduncular hallucinosis with REM sleep behavior disorder. Cortex. 2016;74:96–106. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bates E, Wilson SM, Saygin AP, et al. Voxel-based lesion-symptom mapping. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:448–450. doi: 10.1038/nn1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mah YH, Husain M, Rees G, et al. Human brain lesion-deficit inference remapped. Brain. 2014;137:2522–2531. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Carrera E, Tononi G. Diaschisis: past, present, future. Brain. 2014;137:2408–2422. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fornito A, Zalesky A, Breakspear M. The connectomics of brain disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16:159–172. doi: 10.1038/nrn3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Van Essen DC, Smith SM, Barch DM, et al. The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: an overview. Neuroimage. 2013;80:62–79. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ferro JM, Caeiro L, Figueira ML. Neuropsychiatric sequelae of stroke. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:269–280. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Robinson RG, Jorge RE. Post-Stroke Depression: A Review. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:221–231. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15030363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Murphy R, O’Donoghue S, Counihan T, et al. Neuropsychiatric syndromes of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:697–708. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-315367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kanner AM. Management of psychiatric and neurological comorbidities in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016;12:106–116. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stone J, Pal S, Blackburn D, et al. Functional (Psychogenic) Cognitive Disorders: A Perspective from the Neurology Clinic. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;48(Suppl 1):S5–S17. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Panza F, Frisardi V, Capurso C, et al. Late-life depression, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: possible continuum? Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18:98–116. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181b0fa13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hamani C, Mayberg H, Stone S, et al. The subcallosal cingulate gyrus in the context of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:301–308. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Price JL, Drevets WC. Neurocircuitry of mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:192–216. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Etkin A. Functional neuroanatomy of anxiety: a neural circuit perspective. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2010;2:251–277. doi: 10.1007/7854_2009_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Jacobson MW, et al. Effects of chronic stress on memory decline in cognitively normal and mildly impaired older adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:1384–1391. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09040461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Arciniegas DB, Kaufer DI, et al. Joint Advisory Committee on Subspecialty Certification of the American Neuropsychiatric A. Core curriculum for training in behavioral neurology and neuropsychiatry. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;18:6–13. doi: 10.1176/jnp.18.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]