Abstract

Background:

Accumulating evidence implicates the complement cascade as pathogenically contributing to ischemia-reperfusion injury and delayed graft function (DGF) in human kidney transplant recipients. Building upon observations that kidney injury can initiate in the donor before nephrectomy, we tested the hypothesis that anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a in donor urine prior to transplantation associate with risk of post-transplant injury.

Methods:

We evaluated the effects of C3a and C5a in donor urine on outcomes of 469 deceased donors and their corresponding 902 kidney recipients in a subset of a prospective cohort study.

Results:

We found a 3-fold increase of urinary C5a concentrations in donors with stage 2 and 3 AKI compared donors without AKI (p<0.001). Donor C5a was higher for the recipients with DGF (defined as dialysis in the first week post-transplant) compared to non-DGF (p=0.002). In adjusted analyses, C5a remained independently associated with recipient DGF for donors without AKI (RR 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13–1.54). For donors with AKI, however, urinary C5a was not associated with DGF. We observed a trend toward better 12-month allograft function for kidneys from donors with C5a concentrations in the lowest tertile (p=0.09). Urinary C3a was not associated with donor AKI, recipient DGF, or 12-month allograft function.

Conclusions:

Urinary C5a correlates with the degree of donor AKI. In the absence of clinical donor AKI, donor urinary C5a concentrations associate with recipient DGF, providing a foundation for testing interventions aimed at preventing DGF within this high-risk patient subgroup.

Introduction

Delayed graft function (DGF) is a common early complication following kidney transplantation from donors after neurological or circulatory determination of death. A paired kidney analysis showed that DGF-associated risk of graft failure was greatest in the first year after transplantation, especially in recipients who subsequently develop acute rejection (1). DGF is primarily a consequence of ischemia/reperfusion (IR) injury, which results in post-ischemic acute tubular necrosis (ATN). The degree of post-transplant injury depends on a complex interplay of pre-existing (pre-transplant) donor kidney damage and pathogenic processes initiated upon reperfusion in the recipient (2).

The mechanisms underlying post-transplant IR injury involve reactive oxygen species generation, which initiates innate immune activation, Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling and complement cascade activation (3, 4). Emerging evidence from rodent and large animal models implicate a crucial role for the complement system, in particular as a proximal mediator of kidney IR injury. Kidney IR injury is significantly reduced in animals deficient in C3 or complement factor B, a component of the alternative pathway for complement activation. Likewise, deficiency in complement regulators decay accelerating factor (DAF, CD55) or factor H exacerbated IR injury (5, 6). Complement activation after tissue injury results in local production of anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a. After binding to their specific receptors (C3aR and C5aR respectively) which are expressed on both kidney cells and in bone marrow-derived immune cells, C3a and C5a function as vasodilators, chemo-attractants, and activators of endothelial cells, epithelial cells and infiltrating innate immune cells (7). Downstream complement activation causes membrane attack complex (MAC) formation which inserts pores into cell membranes, additionally activating endothelial cells via non-canonical nuclear factor-kB mediated signaling (3) (Figure S1).

In solid organ transplantation, ischemia and organ injury may commence in the deceased donor. Brain death has well-known effects on hemodynamic instability, hormone dysregulation, and donor organ immunogenicity (8, 9). Current hypotheses include that this brain death-triggered local inflammation is partially responsible for inferior post-transplant outcomes (e.g. higher incidence of DGF and acute rejection with poorer graft survival) of recipients of kidneys from donors who had neurological determinations of death compared to living donor kidneys (10). Experimental evidence indicates that brain death itself activates systemic complement, generating C5a, which upon binding to its receptor on kidney tubular cells contributes to kidney inflammation (11, 12).

These published studies on complement activation, brain death, and kidney injury raised the present hypothesis that C3a and C5a concentrations in donor urine prior to transplantation could help assess risk of early post-transplant IR injury and DGF. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a large, prospective, observational cohort study in which we measured C3a and C5a in urine samples of deceased donors at the time of kidney procurement and determined associations with early post-transplant outcomes in their recipients.

Study cohort and methods

Study cohort

The study cohort was selected from a prospective, multicenter, observational cohort study conducted via collaboration between five organ procurement organizations (OPOs) and five academic centers (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York; Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven; Wayne State University, Detroit; Barnabas Health, Livingston; University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.). Data collection methods are described in detail elsewhere (13). The subset of donors we used in this analysis resulted in kidney transplants at the five transplant centers, where detailed chart abstraction was performed for recipient outcomes.

Participating OPOs enrolled deceased kidney donors between May 2010 and December 2013. Yale University served as the sample and data-coordinating center. OPO personnel followed institutional protocol for managing donors. Healthy volunteers included 5 men and 5 women with a median age of 32 (range 24–61), recruited by oral invitation and general announcements at Mount Sinai under an IRB. OPO scientific review committees as well as institutional review boards for the investigators approved the study, and waiver of consent was granted for recipient chart reviews.

This study also used data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The OPTN data system includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the U.S., submitted by the members of the OPTN. The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, oversees the activities of the OPTN.

Definitions of variables and outcomes

Expanded criteria donors (ECD) were defined as age of 60 or older, or age 50 to 59 with two of the following: history of high blood pressure, serum creatinine level greater than or equal to 1.5 mg/dl, or death resulting from cerebral vascular accident (CVA). We calculated the kidney donor profile index (KDPI) as described, accounting for the following donor-related risk factors: age, height, weight, ethnicity, history of hypertension, diabetes, CVA as cause of death, terminal serum creatinine concentration, hepatitis C virus (HCV) status, and donation after circulatory death (DCD) status (14). The kidney donor risk index (KDRI) was then mapped to the corresponding KDPI, representing a cumulative percentage scale relative to all U.S. deceased donors in 2010 (15).

Donor acute kidney injury (AKI) was defined according to AKI Network criteria based on admission to terminal serum creatinine (irrespective of time between measurements and of urine output cut-offs) as follows: stage 1, increase in serum creatinine by ≥0.3 mg/dl or 1.5 to <2-fold increase; stage 2, 2 to <3-fold increase; and stage 3, ≥3-fold increase, or terminal serum creatinine ≥4.0 mg/dl after a rise of at least 0.5 mg/dl (no donors were dialyzed). Recipient outcomes were obtained from the OPTN/United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS) database and were compared between study donor groups. DGF was defined conventionally as any need for dialysis in the first week after transplantation. Graft failure was defined as return to chronic dialysis or a repeat transplant and was censored for patient death. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated from 12-month serum creatinine value reported in UNOS follow-up forms using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (16). For recipients with graft failure (n=40), we imputed 12-month eGFR as 10 ml/min/1.73 m2 and carried forward the last available serum creatinine value for recipients that died (n=27).

Sample Collection and Complement Measurement

Ten ml of fresh donor urine was collected from the Foley catheter tube in the procurement operating room, immediately placed on wet ice and transferred to the OPOs for temporary storage at −80°C prior to batched shipments. Samples were processed following a single controlled thaw, separated into 1 ml barcoded aliquots, and then stored at −80°C without the addition of protease inhibitors until biomarker measurement. Laboratory personnel at Mount Sinai performed all measurements for complement proteins using commercially available Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kits (OptEIA, BD Biosciences). Standards and samples were added to 96-well plates, washed, combined with a mixture of biotinylated anti-human C3a or C5a antibody and streptavidin horseradish peroxidase, and then read at 450 nm for quantitation.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were reported as mean (standard deviation) or median [interquartile range] for continuous variables and as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. Comparisons were made using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for continuous variables and Pearson’s Chi-Squared test for categorical variables. To directly estimate the relative risk (RR) between the urinary biomarkers and DGF, we fit multivariable modified Poisson regression models(17). When Poisson models are used on a binary outcome, the error of the relative risk is overestimated. To avoid this issue we are using Zou’s approach to modify the Poisson regression models with a sandwich estimation procedure for a robust error variance (17). These models were adjusted for kidney donor risk index (KDRI), cold ischemia time, human leukocyte antigen (HLA) mismatches, recipient race, recipient BMI, and pre-emptive transplantation. To determine if donor AKI status modified the association between urinary complement and recipient DGF, an interaction term between urinary biomarker and donor AKI was included in each model. The interaction term for urine C5a was significant (p=0.05) and thus results were stratified by donor AKI status. Biomarkers were log-base 2 transformed. To determine if donor AKI status modified the association between biomarkers and DGF, interaction terms were included in the models. All regression models were clustered at the level of the kidney donor.

To estimate the discriminatory ability of the biomarkers, we calculated area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve statistics and calculated positive and negative predicted values. SAS 9.3 statistical software for Windows (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for statistical testing, and all statistical tests and confidence intervals were two-sided with a cutoff significance level of 0.05.

Results

Deceased donor characteristics according to AKI status

Of 469 donors, 114 (24%) were classified as having AKI stage 1 or higher. Factors that were significantly associated with donor AKI included black race, ECD status, CVA as cause of death, and high KDPI (Table 1). 84% of the donors received a vasoactive agent (dopamine, epinephrine, neosynephrine, levophed, pitressin) within 24 hours prior to cross clamp.

Table 1.

Donor characteristics according to AKI status

| All (n=469) | AKI (n=114) | No AKI (n=355) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 40 (26, 52) | 44 (27, 52) | 40 (25, 51.5) | 0.153 |

| Male | 307 (66%) | 75 (66%) | 232 (66%) | 0.981 |

| Black Race | 79 (17%) | 28 (25%) | 51 (14%) | 0.013 |

| Extended criteria donor | 78 (17%) | 27 (24%) | 51 (14%) | 0.022 |

| Donation after cardiac death | 71 (15%) | 13 (11%) | 58 (16%) | 0.190 |

| Kidney Donor Profile Index (%) | 45 (21.5, 67) | 60 (37, 78) | 40 (18, 64) | <0.001 |

| CVA as cause of death | 166 (36%) | 52 (46%) | 114 (32%) | 0.01 |

| Terminal serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.92 (0.7, 1.3) | 1.6 (1.24, 2.2) | 0.8 (0.68, 1.1) | <0.001 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CVA, cerebral vascular accident; Statistics reported are median [IQR] or n (%).

Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and chi square test for categorical variables.

Deceased donor and recipient characteristics according to DGF status

We analyzed outcomes in 902 recipients of kidneys from 469 deceased donors. Most donors had both of their kidneys transplanted. In 36 donors, only one kidney was transplanted; the discarded organ was included in the donor analysis. The incidence of DGF in the cohort was 32% (n=291). Recipient factors associated with DGF included black race, high body mass index (BMI), machine perfusion, longer dialysis vintage and cold ischemia time. Comparison of clinical donor characteristics for kidneys with and without subsequent DGF showed that KDPI, DCD status, older donor age, CVA as cause of death, AKI and donor terminal serum creatinine were all associated with DGF. There were no differences in the proportion of ECD kidneys between the DGF and non-DGF groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Deceased donor and recipient characteristics according to DGF status

| ALL (n=902) | DGF (n=291) | No DGF (n=611) | P* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recipient Characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 54 (44, 63) | 53 (45, 62) | 55 (44, 63) | 0.73 | |

| Male | 561 (62%) | 194 (67%) | 367 (60%) | 0.056 | |

| Black race | 392 (43%) | 161 (55%) | 231 (38%) | <0.001 | |

| Previous kidney transplant | 118 (13%) | 39 (13%) | 79 (13%) | 0.84 | |

| Cause of ESRD | Other or unknown | 206 (23%) | 58 (20%) | 148 (24%) | 0.20 |

| Diabetes | 262 (29%) | 85 (29%) | 177 (29%) | ||

| Hypertension | 238 (26%) | 90 (31%) | 148 (24%) | ||

| GN | 148 (16%) | 42 (14%) | 106 (17%) | ||

| Graft failure | 48 (5%) | 16 (5%) | 32 (5%) | ||

| Panel reactive antibody | 0% | 578 (64%) | 188 (65%) | 390 (64%) | 0.52 |

| 1–20% | 58 (6%) | 22 (8%) | 36 (6%) | ||

| 21–80% | 119 (13%) | 40 (14%) | 79 (13%) | ||

| >80% | 147 (16%) | 41 (14%) | 106 (17%) | ||

| Pre-transplant dialysis | 794 (88%) | 279 (96%) | 515 (84%) | <0.001 | |

| Body mass index | 27.4 (23.8, 31.6) | 28.2 (24.4, 33.1) | 26.9 (23.5, 30.9) | <0.001 | |

| Duration of dialysis before transplant, months | 44.6 (15.8, 67.8) | 56.7 (32.5, 75.8) | 38.1 (9.0, 62.0) | <0.001 | |

| HLA mismatch level | 5 [4, 5] | 5 [4, 5] | 5 [4, 5] | 0.029 | |

| Cold ischemia time, hours | 14 [10, 18.5] | 15.4 [11.7, 20.3] | 13 [9.3, 17.4] | <0.001 | |

| Kidney machine perfused | 317 (35%) | 131 (45%) | 186 (30%) | <0.001 | |

| Donor Characteristics | |||||

| Age, years | 40 [26, 51] | 45 [30, 53] | 36 [24, 50] | <0.001 | |

| Male | 597 (66%) | 201 (69%) | 396 (65%) | 0.21 | |

| Black race | 155 (17%) | 52 (18%) | 103 (17%) | 0.71 | |

| Extended criteria donor | 139 (15%) | 52 (18%) | 87 (14%) | 0.16 | |

| Donation after cardiac death | 139 (15%) | 74 (25%) | 65 (11%) | <0.001 | |

| Kidney donor profile index, % | 43 [21, 67] | 54 [35, 70] | 37 [18, 62] | <0.001 | |

| CVA as cause of death | 318 (35%) | 119 (41%) | 199 (33%) | 0.014 | |

| Acute kidney injury | 216 (24%) | 95 (33%) | 121 (20%) | <0.001 | |

| Terminal serum creatinine, mg/dl | 0.9 [0.7, 1.3] | 1.04 [0.7, 1.5] | 0.9 [0.7, 1.2] | 0.003 | |

DGF, Delayed Graft Function; ESRD, End Stage renal Disease; CVA, cerebral vascular accident; GN, Glomerulonephritis; HLA, Human Leukocyte Antigen. Statistics reported are median [IQR] or n (%).

Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables and chi square test for categorical variables.

The 1-year acute rejection rate in the cohort was 9% and was not different in DGF versus non-DGF (9 vs. 8%; p=0.8). Median 1-year eGFR was 40.7 [33.1, 54.5] ml/min/1.73m2 in recipients with rejection and 58.5 [46.3, 74.7] ml/min/1.73m2 in recipients without rejection (p<0.0001).

Anaphylatoxins are detectable in deceased donor urine

Both C3a and C5a were detected in deceased-donor urine samples. Compared to donors with brain death urine samples from DCD donors contained more C3a (0.32 [0.21, 0.47] ng/ml vs. 0.38 [0.25, 0.63] ng/ml; p=0.04) and more C5a (0.28 [0.13, 0.78] ng/ml vs. 1.0 [0.24, 2.17] ng/ml; p<0.001).

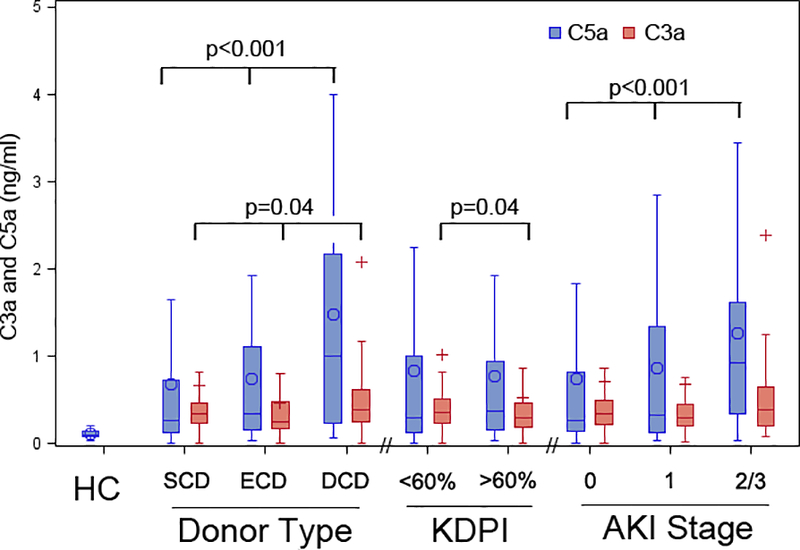

C3a concentrations were slightly higher in donors with KDPI less than 60% compared to those with KDPI above 60% (p=0.04). Of note, urinary C5a was detected in only low concentrations in healthy controls (0.11± 0.05 ng/ml; n=10) (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Comparison of urinary C3a and C5a levels in healthy controls (for C5a); as well as in donors classified by type, kidney donor profile index, and acute kidney injury stage.

This plot shows the distributions of biomarker values in healthy controls (HC; n=10); and in donors classified by brain-dead standard criteria (SCD; n=320), brain-dead extended criteria (ECD; n=78), donation-after–cardiac-death donors (DCD; n=71), kidney donor profile index (KDPI) above (n=263) or below 60% (n=204), acute kidney injury (AKI) stage 0 (n=352), stage 1 (n=71), and stage 2/3 (n=43). Rectangles represent the intra-quartile range (25th to 75th percentile), with the horizontal line being the median value. The circles represent mean values, and the upper and lower whiskers present minimum and maximum, respectively. Blue denotes urinary C5a, and red denotes urinary C3a. P-values were determined by Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

Urinary C5a correlates with donor acute kidney injury

We observed a significant association between donor AKI and urinary C5a, with 3-fold higher median C5a concentration in donors with AKI stage 2/3 vs. those without AKI (0.92 [0.32, 1.62] ng/ml vs. 0.27 [0.14, 0.83] ng/ml, p<0.001; Figure 1, Table S1). These findings persisted after indexing urine C5a to urine creatinine concentration (Table S1). Urinary C3a values were not associated with AKI status (Table S1).

Thirteen of the 71 DCD donors (18%) met criteria for AKI. In this DCD subset, we observed a non-significant trend toward higher C5a concentration in the setting of donor AKI compared to no AKI (1.57 [0.47, 2.17] ng/ml vs. 0.72 [0.24, 2.18] ng/ml).

To test whether C5a correlates with other donor injury biomarkers we analyzed our data on urinary KIM-1, neutrophil gelatinase–associated lipocalin (NGAL), IL-18. We observed a strong direct correlation between C5a and these injury markers, supporting a mechanistic relationship (Table S2).

Donor urine C5a correlates with risk of developing post-transplant DGF

Of the 902 transplanted kidneys, 32% experienced DGF. We observed significantly higher donor urine C5a values for recipients who developed DGF compared to those who did not (0.42 [0.15, 1.28] ng/ml vs. 0.28 [0.13, 0.87] ng/ml, p=0.002). In contrast, donor urinary C3a was not different by DGF status (Table 3). In multivariable analyses, donor urine C5a remained associated with DGF independent of clinical variables known to associate with DGF, including KDRI, cold ischemia time, HLA mismatch, and the following recipient characteristics: race, BMI, and pre-transplant dialysis (Table 4).

Table 3:

Urinary C3a and C5a levels by donor AKI and recipient DGF

| All Donors | Donors without AKI | Donors with AKI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No DGF (n=609) | DGF (n=287) | P* | No DGF (n=488) | DGF (n=192) | P* | No DGF (n=121) | DGF (n=95) | P* | |

| C3a (ng/ml) | 0.33 [0.23, 0.48] | 0.36 [0.2, 0.52] | 0.69 | 0.33 [0.23, 0.48] | 0.39 [0.19, 0.53] | 0.45 | 0.31[0.23, 0.48] | 0.32[0.2, 0.5] | 0.83 |

| C5a(ng/ml) | 0.28 [0.13, 0.87] | 0.42[0.15, 1.28] | 0.002 | 0.24 [0.13, 0.7] | 0.37 [0.15, 1.27] | 0.002 | 0.47 [0.21, 1.58] | 0.56 [0.18, 1.54] | 0.92 |

DGF, delayed graft function; AKI, acute kidney injury. AKI defined as stage 1 or higher with at least an increase in serum creatinine of ≥ 0.3 mg/dl or at least an increase of 1.5-fold from admission to terminal value. Statistics reported are median [IQR].

Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Table 4.

Multivariate modeling of relative risk of recipient DGF by concentrations of deceased donor urinary C3a and C5a

| Cohort | Relative Risk (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted (n=902) | Adjusted for KDRI 1 (n=898) | Adjusted for KDRI & transport variables 2 (n=884) | Adjusted for KDRI, transport & recipient variables 3 (n=882) | |

| Log C3a | ||||

| No Donor AKI | 1.00 (0.82, 1.22) | 1.04 (0.85, 1.25) | 1.00 (0.81, 1.23) | 0.97 (0.82, 1.15) |

| Donor AKI | 1.00 (0.80, 1.25) | 1.04 (0.83, 1.29) | 1.05 (0.85, 1.30) | 1.12 (0.94, 1.33) |

| Log C5a | ||||

| No Donor AKI | 1.32 (1.12, 1.56) | 1.32 (1.11, 1.56) | 1.30 (1.10, 1.55) | 1.31 (1.13, 1.54) |

| Donor AKI | 0.99 (0.77, 1.26) | 1.03 (0.80, 1.32) | 1.02 (0.79, 1.32) | 1.10 (0.86, 1.41) |

KDRI, Kidney Donor Risk Index

Includes KDRI and cold ischemia time

Includes all variables listed above plus number of human leukocyte antigen mismatches, and the following recipient factors: race, body mass index, and pre-emptive transplant.

Biomarkers are log base 2 transformed.

Donor AKI showed significant effect modification with C5a (p=0.05) but not C3a (p=0.9) with the outcome of DGF. Since effect modification was present with C5a, C3a results were presented with the same approach.

We previously showed that donor AKI stage is associated with recipient DGF (18). Donor AKI showed significant effect modification with C5a (p=0.05) but not C3a (p=0.9) on the outcome of DGF. Since we saw the effect modification with C5a, we presented C3a with the same approach. Because we observed that donor AKI stage was strongly associated with increased donor urinary C5a concentrations in the current analysis (p<0.001; Figure 1, Table S1), we tested whether donor C5a was associated with recipient DGF independent of donor AKI. We first analyzed the relationship between urinary C5a and DGF stratified by donor AKI. Of the 216 recipients of donor kidneys with AKI stage ≥1 (24% of the total cohort, n=902), 95 (44%) developed DGF. In the 680 recipients of kidneys from donors without AKI (72% of the total cohort), 192 (28%) developed DGF. In this DGF cohort, we observed a non-significant trend toward higher donor urine C5a levels in the donor AKI group compared to non-AKI group (0.56 [0.18, 1.54] ng/ml vs. 0.37 [0.15, 1.27] ng/ml; p=0.35; Table 3). Figure S2 summarizes the occurrence of donor AKI and DGF according to donor type. Analyses adjusted for donor and recipient characteristics showed donor urinary C5a independently associated with recipient DGF only in the non-AKI donor subset, thereby identifying an additional high-risk group (Table 4).

We also tested the predictive value of C5a for development of DGF, considering values within the 1st tertile of C5a level as negative and values within the 2nd or 3rd tertiles as positive results. In donors with AKI, C5a had positive and negative predictive values of 44% and 56%, respectively. This suggests that donor urine C5a does not add to the predictive value of donor AKI for the development of DGF. In non-AKI kidneys, C5a had positive and negative predictive values of 32% and 78%, respectively, suggesting that low urinary C5a concentrations and the absence of donor AKI represent low risk for DGF (Table S3). The AUC for predicting DGF with C3a and C5a were 0.51 (95% CI 0.47, 0.55) and 0.56 (95% CI 0.52, 0.60), respectively (Figure S3).

Donor urinary C3a / C5a and post-transplant kidney function

To test whether donor urine C3a or C5a concentrations were associated with 12-month post-transplant graft function, we compared urinary C5a levels within the 1st tertile with the 2nd or 3rd tertile. We observed a non-significant trend toward higher eGFR in the lowest C5a tertile for the total cohort (T1: 59.4 ml/min/1.73m2 vs. T2&3: 56.5 ml/min/1.73m2; p=0.09). However, stratifying by donor AKI revealed no clear association for urinary C3a (data not shown) or C5a with 12-month eGFR (Table S4). To determine if 12-month eGFR differed by C5a tertile when stratified by both the donor AKI profile and corresponding recipient DGF status, we tested a 3 way interaction term in an ANOVA model. The interaction term of urinary C5a tertile X donor AKI X recipient DGF was not significant (p=0.23).

Discussion

This a prospective, observational, multicenter cohort study to test the potential utility of C3a and C5a within deceased donor urine samples as biomarkers for post-transplant outcomes. Our findings indicate that C5a detected in donor urine obtained at the time of organ procurement can be used to assess the risk of developing DGF in the recipient. Elevated donor urinary C5a was independently associated with DGF and provides clinically useful information beyond donor terminal serum creatinine values or AKI stages. For patients who received kidneys from donors without AKI, elevated urinary C5a was associated with an elevated risk of DGF and low C5a had a high negative predictive for DGF. For recipients of donor organs with AKI, urinary C5a provided no additional predictive utility for DGF.

Deceased-donor AKI is associated with organ discard and DGF, but data on longer-term allograft survival are limited (2). Nevertheless, to advance DGF prevention and treatment, it is important to understand the effects of IR-induced AKI and dissect and evaluate the influence of factors related to the donor and to the recipient. Our current inability to accurately predict or quickly diagnose DGF leads to misclassification of patients in clinical trials aimed at preventing or treating DGF (19). For example, ameliorating IR injury after transplant would likely only reduce DGF when IR injury is the primary cause of DGF. The same treatments would be ineffective when DGF is due to recipient comorbidities such as diastolic heart disease.

Taken together with clinical information, biomarkers measured in the donor could guide perioperative recipient management. We have previously shown that the level of kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) renal tissue expression before reperfusion correlated inversely with renal function at the time of procurement, but not with the occurrence of DGF (20). In addition, our group found that donor urinary concentrations of NGAL, KIM-1, IL-18, and liver-type fatty acid binding protein (L-FABP) each strongly associated with donor AKI but were of limited value in predicting recipient DGF (21).

In contrast to previous donor biomarkers, we found that doubling of donor urinary C5a concentration was independently associated with 23% increased risk of DGF. Our findings also support the emerging concepts that complement activation is pathogenically linked to renal damage and IR-initiated transplant kidney injury in humans (22, 23). Brain death is a trigger for complement activation and associates with increased circulating C3a, C5a, and C5b-9 levels; whereas systemic C5a is believed to mediate renal inflammation via tubular C5a–C5aR interaction (11, 24). Systemic and renal complement activation is thought to exacerbate IR injury and the inhibition of complement-improved graft function after transplantation in preclinical models (12, 25). Anti-C5a antibody treatment of pre-transplant donor rat kidneys during cold ischemia protected renal function and prolonged graft survival (26).

Our data show that complement activation is similarly ongoing in humans because we find more C5a in urine samples from deceased donors than from normal volunteers (analogous to living donors). We focused on urinary and not blood complement levels because urinary C3a and C5a reflect filtered as well as locally (especially by tubular cells) produced and activated complement (27). An important goal of future studies is to clarify the triggers and mechanisms of complement activation during brain death and other events before organ retrieval.

We found that there was significantly higher C3a and C5a generation in DCD donors compared to brain dead donors. DCD donors result in prolonged warm-ischemia during kidney procurement, and the increased anaphylatoxin levels seen with DCD are likely due to complement activation through the coagulation activation pathway (28). Thrombin can cleave C5 to C5a and C5b to activate terminal complement pathway (29). Our studies build upon previous reports in mice supporting a predominant role for C5a and a minor role for C3a in the pathogenesis of AKI. While both C3a and C5a were up-regulated in post-ischemic mouse kidneys in our study, the pathogenic role of C5a dominated (7). C5a is downstream of C3a and there is further amplification (Figure S1). It is possible that this amplification cascade is one of the reasons why we observe higher amount of and more pronounced effects with C5a and not C3a (30). C5a is a potent chemoattractant, but the role of C3a in chemotaxis is less clear. In addition, C5a has multiple downstream effects including direct proinflammatory effects on tubular and endothelial cells (7, 31). These cells express C5aR and C5a/C5aR binding has been shown to induce inflammasome activation that results in IL-18 release (32). C5a is one of 2 cleavage products of C5, the other being C5b. C5b initiates the MAC formation and MAC insertion on endothelial cells induces noncanonical NFkB activation, which again results in release of cytokines and, potentially other markers of injury (3). The strong direct correlations we observed between C5a and the injury marker NGAL, IL-18 and KIM1 support the mechanistic relationship. Hypoxia promotes reactive oxygen species production, causing cell injury and up-regulation of TLR and other molecules like HMGB1, leading to further complement production and immune cell recruitment (4, 33).

Our newly documented association between donor urine C5a levels and recipient DGF has important clinical implications. The finding that anaphylatoxins are released in donors before organ removal provides a strong rationale to initially target complement in the donor and then extend this treatment into the recipient. For example, eculizumab blocks C5 convertase activity, thereby preventing C5a production and membrane attack complex (MAC) formation. Eculizumab has been tested to evaluate its potential to reduce the rate of peritransplant ischemic acute injury in humans. Preliminary results of the Prevention of Delayed Graft Function Using Eculizumab Therapy (PROTECT) study (ClinicalTrials ID NCT02145182) found a non-significant difference in the incidence of DGF, graft loss, or loss to follow up (35.9% with Eculizumab vs. 41.7% in placebo-treated controls) (34). However, several more anti-complement drugs are in development (2, 35), and it may be possible to improve outcomes by providing anti-DGF therapy only in those recipients at highest risk of developing DGF. Our study suggests that an approach to such enrichment could be restricting this therapy to recipients of kidneys with elevated donor urine C5a levels. Similar to KIM-1, for example, it may be possible to develop urine C5a assays that utilize rapid microsphere-based dipstick technology and require only small sample volumes.

The strengths of our study include standardized, prospective and a large sample size permitting adjusted analyses of donor, transport and recipient variables. However, there are important limitations to the study. First, we could not analyze specific donor events that could have influenced complement production such as duration of brain death or degree of hemodynamic instability. Second, despite adjustment for critical donor and recipient factors, unmeasured confounding variables is possible given the observational study design. Third, we only assessed at a single time-point and could not extend C3a/C5a measurement into the peri-transplant period, which can also influence graft outcome. In addition, other markers of complement activation like properidin, a key factor in alternative pathway complement activation, and the formation of C5b-9, are other potential makers of complement activation in the context of transplantation.

The finding that urinary C5a independently associates with the severity of renal injury in the donor and the recipient highlights the important role of C5a in renal damage in humans. Further innovative studies are needed to test the utility of combining C5a measurements with complement-targeted therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by 1) the National Institutes of Health grant RO1DK-93770, grant K24DK090203, 2) PSH is supported in part by NIH/NIAID grant UO1AI063594. The content of this manuscript is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does it mention trade names, commercial products, or organizations implying endorsement by the U.S. Government. These organizations were not involved in study design, analysis, interpretation, or manuscript creation.

The data reported here have been supplied by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) as the contractor for the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the OPTN or the U.S. Government.

The authors thank Isabel Butrymowicz and Rowena Kemp for their assistance with data and sample coordination for this multicenter study. We also thank the OPOs Gift of Life Philadelphia (Sharon West, Vicky Reilly), the New York Organ Donor Network (Harvey Lerner, Anthony Guidice, Allison Hoffman), the Michigan Organ and Tissue Donation Program (Burton Mattice, Susan Shay), and the New Jersey Sharing Network (William Reitsma, Cindy Godfrey, Alene Steward, Joel Padilla Benitez).

Disclosure

Research funding and speaker honoraria were from Alexion (BS, PH).

References

- 1.Gill J, Dong J, Rose C, Gill JS. The risk of allograft failure and the survival benefit of kidney transplantation are complicated by delayed graft function. Kidney Int. 2016;89:1331–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schroppel B, Legendre C. Delayed kidney graft function: from mechanism to translation. Kidney Int. 2014;86:251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cravedi P, Heeger PS. Complement as a multifaceted modulator of kidney transplant injury. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:2348–2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kruger B, Krick S, Dhillon N, et al. Donor Toll-like receptor 4 contributes to ischemia and reperfusion injury following human kidney transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3390–3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renner B, Ferreira VP, Cortes C, et al. Binding of factor H to tubular epithelial cells limits interstitial complement activation in ischemic injury. Kidney Int. 2011;80:165–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada K, Miwa T, Liu J, Nangaku M, Song WC. Critical protection from renal ischemia reperfusion injury by CD55 and CD59. J Immunol. 2004;172:3869–3875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng Q, Li K, Smyth LA, et al. C3a and C5a promote renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:1474–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Hoeven JA, Molema G, Ter Horst GJ, et al. Relationship between duration of brain death and hemodynamic (in)stability on progressive dysfunction and increased immunologic activation of donor kidneys. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1874–1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Damman J, Daha MR, van Son WJ, Leuvenink HG, Ploeg RJ, Seelen MA. Crosstalk between complement and Toll-like receptor activation in relation to donor brain death and renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Damman J, Hoeger S, Boneschansker L, et al. Targeting complement activation in brain-dead donors improves renal function after transplantation. Transpl Immunol. 2011;24:233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Werkhoven MB, Damman J, van Dijk MC, et al. Complement mediated renal inflammation induced by donor brain death: role of renal C5a-C5aR interaction. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:875–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damman J, Seelen MA, Moers C, et al. Systemic complement activation in deceased donors is associated with acute rejection after renal transplantation in the recipient. Transplantation. 2011;92:163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potluri VS, Parikh CR, Hall IE, et al. Validating Early Post-Transplant Outcomes Reported for Recipients of Deceased Donor Kidney Transplants. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao PS, Schaubel DE, Guidinger MK, et al. A comprehensive risk quantification score for deceased donor kidneys: the kidney donor risk index. Transplantation. 2009;88:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Organ Procurement and Transplant Network. A guide calculating and interpreting KDPI. Accessed June 12, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levey AS, Stevens LA. Estimating GFR using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) creatinine equation: more accurate GFR estimates, lower CKD prevalence estimates, and better risk predictions. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:622–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou G A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall IE, Schroppel B, Doshi MD, et al. Associations of deceased donor kidney injury with kidney discard and function after transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:1623–1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavaille-Coll M, Bala S, Velidedeoglu E, et al. Summary of FDA workshop on ischemia reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1134–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroppel B, Kruger B, Walsh L, et al. Tubular expression of KIM-1 does not predict delayed function after transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:536–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reese PP, Hall IE, Weng FL, et al. Associations between Deceased-Donor Urine Injury Biomarkers and Kidney Transplant Outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27:1534–1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma R, Cui Z, Liao YH, Zhao MH. Complement activation contributes to the injury and outcome of kidney in human anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33:172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vries DK, van der Pol P, van Anken GE, et al. Acute but transient release of terminal complement complex after reperfusion in clinical kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95:816–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Werkhoven MB, Damman J, Daha MR, et al. Novel insights in localization and expression levels of C5aR and C5L2 under native and post-transplant conditions in the kidney. Mol Immunol. 2013;53:237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atkinson C, Floerchinger B, Qiao F, et al. Donor brain death exacerbates complement-dependent ischemia/reperfusion injury in transplanted hearts. Circulation. 2013;127:1290–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu ZX, Qi S, Lasaro MA, et al. Targeting Complement Pathways During Cold Ischemia and Reperfusion Prevents Delayed Graft Function. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:2589–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrar CA, Zhou W, Lin T, Sacks SH. Local extravascular pool of C3 is a determinant of postischemic acute renal failure. FASEB J. 2006;20:217–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oikonomopoulou K, Ricklin D, Ward PA, Lambris JD. Interactions between coagulation and complement--their role in inflammation. Semin Immunopathol. 2012;34:151–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huber-Lang M, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, et al. Generation of C5a in the absence of C3: a new complement activation pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12:682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thurman JM, Holers VM. The central role of the alternative complement pathway in human disease. J Immunol. 2006;176:1305–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foreman KE, Vaporciyan AA, Bonish BK, et al. C5a-induced expression of P-selectin in endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1147–1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laudisi F, Spreafico R, Evrard M, et al. Cutting edge: the NLRP3 inflammasome links complement-mediated inflammation and IL-1beta release. J Immunol. 2013;191:1006–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Z, Haimovich B, Kwon YS, Lu T, Fyfe-Kirschner B, Olweny EO. Unilateral Partial Nephrectomy with Warm Ischemia Results in Acute Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1-Alpha (HIF-1alpha) and Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Overexpression in a Porcine Model. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alexion. Available at news.alexionpharma.com. Accessed June 12, 2017.

- 35.Thurman JM. New anti-complement drugs: not so far away. Blood. 2014;123:1975–1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.