Abstract

Objective:

To develop new patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures to better understand feelings of loss in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Design:

Cross-sectional survey study.

Setting:

Three TBI Model Systems rehabilitation hospitals, an academic medical center, and a military medical treatment facility.

Participants:

Five-hundred-sixty caregivers of civilians with TBI (n=344) or service members/veterans (SMVs) with TBI (n=216).

Interventions:

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures:

TBI-CareQOL Feelings of Loss-Self and TBI-CareQOL Feelings of Loss-Person with Traumatic Brain Injury Item banks

Results:

While the initial exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of the Feelings of Loss item pool (98 items) potentially supported a unidimensional set of items, further analysis indicated two different factors: Feelings of Loss-Self (43 items) and Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI (20 items). For Feelings of Loss-Self, an additional 13 items were deleted due to item-response theory based item misfit; the remaining 30 items had good overall model fit (Confirmatory Fit Index [CFI]=0.96, Tucker Lewis Index [TLI]=.96, Root Mean Squared Error [RMSEA]=.10). For Feelings of Loss-Other, 1 additional item was deleted due to an associated high correlated error modification index value; the final 19 items evidenced good overall model fit (CFI=0.97, TLI=.97, RMSEA=.095). The final item banks were developed to be administered as either a CAT or a short-form. Clinical experts approved the content of the 6-item short forms of the two measures (three-week test-retest was r=.87 for Feelings of Loss-self and r=.85 for Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI)

Conclusions:

The findings from this study resulted in the development of two new PROs to assess feelings of loss in caregivers of individuals with TBI; TBI-CareQOL Feelings of Loss-Self and TBI-CareQOL Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI. Good psychometric properties were established and a short-form was developed for ease of use in clinical situations. Additional research is needed to determine concurrent and predictive validity of these measures in the psychological treatment of those caring for persons with TBI.

Keywords: Health-related quality of life, PROMIS, TBI-CareQOL, traumatic brain injury, caregiver, caregiver strain, caregiver burden, patient reported outcome

Sustaining a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) can lead to challenges in everyday functioning.1,2 Functional impairments and disability can result in the need for assistance in everyday activities.3,4 Family members are often required to assume the role of informal “caregiver” and bear primary responsibility for assistance with physical, cognitive, financial, and leisure activities.5–9 This caregiver role can be associated with negative outcomes, including changes in caregiver health-related quality of life (HRQOL).10–17 Feelings of loss for both caregivers and the person with TBI can also negatively impact caregiver HRQOL.18

Prior qualitative work has described caregivers’ feelings of loss following TBI.18,19 Specifically, caregivers experience feelings related to loss of their loved one’s future potential. Caregivers also experience feelings related to loss of their own relationships and future plans.18,20 This concept of feelings of loss is consistent with findings of objective changes in social roles for caregivers after TBI, including changes in employment, social activities, and relationships.21 Such changes and feelings are congruent with the stress-process model of caregiving22 which is characterized by multifaceted interactions between caregiving demands and personal resources c factors (e.g., age, gender) interact with primary and secondary stressors associated with caregiver demands (i.e., problematic conditions, experiences, and activities). Primary stressors result directly from the injury and include the cognitive, behavioral and functional status of the care-recipient. Secondary stressors (including feelings of loss) arise in response to primary stressors and include interpersonal strain between the caregiver and other family members including the care-recipient, economic and social strain, self-esteem, perceptions of caregiver mastery, and competence. Both primary and secondary stressors can be mediated by variables such as social support and coping style/ability. The complex interactions among these three domains result in either positive or negative behavioral outcomes for the caregiver, including poor HRQOL and/or health problems.

Feelings of loss can also be considered within the caregiver model of grief.23 This model conceptualizes caregiver anticipatory grief, or the behavioral reactions to personally significant losses that are experienced when caring for a living individual, as a normal phase of bereavement like that associated with an actual death. Similarly, the theory of ambiguous loss24,25 can be defined as a situation in which the care-recipient is physically present (i.e., living), but psychologically absent. In a caregiving context, such feelings can psychologically immobilize both the caregiver and care-recipient, and result in negative outcomes for both.

Much of our knowledge regarding feelings of loss in caregivers is derived from research with dementia caregivers, in whom feelings of grief and loss are common. These feelings include ambiguity towards the care-recipient and perceptions of loss due to the change in the caregiver-care-recipient relationship (e.g., loss of emotional and physical intimacy).26−32 Caregivers of individuals with dementia also express feelings of loss related to their occupation,33 physical well-being (e.g., sleep, general health problems),31·33 social well-being,26,28,31,33 future hopes/dreams plans,29–32 as well as loss related to their personal identity.34 Additionally, they experience feelings of loss for the personality changes,27–29,31,32,35 pre-injury abilities,26 and future life31,32 of the person with dementia.

In order to better understand feelings of loss in caregivers of individuals with TBI, we developed new patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures that are specific to caregivers of civilians and service member/veterans with TBI. These new measures were developed according to established guidelines,36 as a part of the TBI-CareQOL measurement system37 which includes both generic patient reported outcomes (PROs) from the existing Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS),38,39 as well as new, TBI-caregiver-specific PROs. In this report, we describe the development of two new measures of feelings of loss for use in caregivers of individuals with TBI.

Methods

Study Participants

Five hundred and sixty caregivers of individuals with TBI were enrolled in this study; 145 also completed a 3-week retest. Details of the sample are provided elsewhere.37

Caregivers of civilians with TBI must have been caring for an individual with a medically documented complicated mild, moderate, or severe TBI, based on TBI Model Systems criteria.40 Caregivers of SMVs with TBI must have been caring for a person with a TBI that was medically documented by a healthcare facility. For both subsamples, the caregiver must have been able to read/understand English, and the person with TBI had to be ≥16 years of age at the time of injury and at least one-year post-injury. Caregiver status was defined as providing physical assistance, financial assistance, or emotional support to an individual with a TBI. The study was conducted in accordance with the local institutional review boards and caregivers provided consent before participating in this study.

Measures

TBI-CareQOL Feelings of Loss Item Pool:

The initial Feelings of Loss item pool (which included 75 items) was based on focus group discussion among caregivers of civilians and SMVs with TBI19,41 and included items that examined feelings of loss with regard to the individual with TBI (including loss of abilities, loss of potential/future, and changes in behavior/personality), as well as losses related to the caregivers themselves (including loss of self, relationships, activities and future plans). Items were added and/or deleted according to an iterative process (details in Carlozzi et al.37). The final item pool was comprised of 98 items.

Statistical Analyses

Sample size considerations are reported elsewhere.37 Classical test theory (CTT) and item response theory (IRT) were used to develop new measures. Whereas CTT requires successful completion of all test items in order to estimate an individual’s “true score,”42 IRT can be used to generate a score based on any subset of items (which allows for the retention of only the best performing items). IRT-based calibrations can also be used to program CAT administration for a PRO measure.

Establishing a Unidimensional Set of Items.

An iterative process using full-sample exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (EFA, CFA) and clinical input43–45 was used to select a unidimensional set of items (conducted using Mplus version 7.446). Using EFA, we focused on the following criteria to support unidimensionality: the ratio of eigenvalue 1 to eigenvalue 2 > 4 and the proportion of variance accounted for by eigenvalue 1>.40. Items with sparse cells (response categories with n<10 respondents), low correlations for item-adjusted total scores (<0.40), or non-monotonicity (according to item-rest plots and expected score by latent trait plots obtained from a non-parametric IRT model [Testgraf Software47]) were excluded. Initial CFAs flagged items with low factor loadings (lx <0.50) and items demonstrating local dependence (residual correlation >0.20; correlated error modification index ≥100).43−45 Once a unidimensional set of items was established, IRT was used to further model the data, with Samejima’s graded response model (GRM)48 employed to establish item parameters (analyses conducted in IRTPRO version 3.149). Items displaying significant misfit (S-X2, p<0.01) were excluded based on these GRM-related analyses.

Differential item functioning (DIF; conducted using the R package LORDIF (Version 0.3– 2)50,51 provides an indication of unexpected behavior by an item on a test; it is when an item performs differently for a subgroup of participants when it should not (e.g., men perform better than women). The most important indicator of DIF is not whether items systematically differentiate relevant subgroups, but whether they do so in an unpredicted way. DIF was used to identify unexpected item bias for age (≤40 vs. >40 years), education (<college vs. ≥college), and caregiver status (civilians vs. SMVs). Items showing impactful DIF were excluded (Nagelkerke pseudo-R2 change ≥0.20, plus >2% of DIF-corrected vs. uncorrected score differences exceeding uncorrected score standard errors). These analyses used a hybrid IRT ability score-ordinal logistic regression framework.52

As a final check of unidimensionality, final CFA modeling was conducted. Standard fit criteria were used: comparative fit index (CFI) ≥0.95, Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) ≥0.95, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) <0.15.53–56

Item Bank Scores.

Final item banks permit administration of computer adaptive tests (CATs) or fixed-length short-forms (SF). Firestar simulation software was used to simulate CAT scores.57 A 6-item short form was selected using clinical expert opinion on item content and range of concept coverage and item calibration-related statistics (e.g., item slope, thresholds, average item difficulty, item information).

Results

Study Participants

A total of 560 caregivers of individuals with TBI participated in this study (n=344 caregivers of civilians with TBI and n=216 caregivers of SMVs with TBI). Briefly, caregivers were on average 46.1 years of age (SD=14.1) and were primarily female (86%). Caregivers were also primarily Caucasian (77.2%), followed by African American (13.8%), and other races (8.8%; 0.2% of the sample omitted this question); 10.6% indicated they were of Hispanic or Latino descent. With regard to education, 39.5% had a college degree, followed by some college (42%), or a high school degree or less (18.6%). Most were married or cohabitating (74.2%), followed by never married (11.3%), separated or divorced (9.9%) and widowed (3.9%; marital status was missing for 0.7% of the sample). Most participants were in the caregiver role for an average of 5.8 years (SD=5.4), and most were spouses (58.2%), followed by parents (22.9%), children or other family relations (12.9%), and “other” relationships (e.g., friends; 5.9%). Most (84.2%) of participants were caring for a male with TBI, and the average age of the person with TBI was 40.3 years of age (SD=12.6).

Establishing a Unidimensional Set of Items.

Initial evidence from EFA from the initial item pool (98 items) indicated that the full item set was potentially unidimensional. One item was eliminated due to having a low item-adjusted total score correlation, 18 items were deleted due to high residual correlations, and nine items were deleted due to high correlated error modification index values. Subsequent CFA and IRT modeling of the remaining 70 items indicated poor overall and individual item fit. Thus, a new EFA was conducted on the remaining 70 items which revealed a 4-factor solution (Table 1). This solution included two distinct aspects of Feelings of Loss: caregivers’ feelings of loss about their own lives (Feelings of Loss-Self, 43 items), and caregivers’ feelings of loss about the lives of those for whom they are providing care (Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI, 20 items). The third and fourth factors did not include enough items for consideration as stand-alone measures.

Table 1.

Exploratory Factor Analysis Results for the Feelings of Loss Item Pool

| Item Description | Factor 1 |

Factor 2 |

Factor 3 |

Factor 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I have stopped living my life to care for the person with the injury. | 0.72 | 0.03 | −0.11 | 0.38 |

| It feels like I have lost my own identity because I am caring for someone else. | 0.85 | 0.00 | −0.07 | 0.33 |

| The responsibilities I have as a caregiver make me feel socially isolated. | 0.86 | −0.06 | −0.10 | 0.42 |

| I am sad because my life may not be the way I thought it would be. | 0.83 | 0.07 | −0.01 | −0.09 |

| I feel sad I cannot go places because I have to care for the person with the injury. | 0.87 | 0.01 | −0.11 | 0.25 |

| I mourn that I can no longer do things that I had planned because of my role as a caregiver. | 0.88 | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.17 |

| I mourn for the life I used to have before the person I care for was injured. | 0.76 | 0.07 | 0.11 | −0.02 |

| I get depressed when I think that I am losing my future. | 0.96 | 0.08 | −0.16 | −0.09 |

| I feel devastated when I think that I am losing my future. | 0.98 | 0.13 | −0.22 | −0.07 |

| I feel miserable when I think about how my life has changed since the injury. | 0.86 | 0.07 | 0.01 | −0.16 |

| I feel sad because becoming a caregiver has changed who I am. | 0.90 | −0.13 | 0.11 | −0.02 |

| I feel sad because I am no longer able to do things I used to enjoy with the person I care for. | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.04 |

| I feel sad because becoming a caregiver has changed what I expect for my future. | 0.96 | −0.07 | −0.01 | 0.03 |

| I feel devastated because my plans for the future have changed since the injury. | 0.83 | 0.16 | −0.07 | −0.08 |

| It is difficult to pursue new relationships because I have to care for the person with the injury. | 0.70 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.31 |

| It is difficult to deal with personality changes in the person I care for. | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.31 | 0.04 |

| My relationships with other people are affected because I have to care for the person with the injury. | 0.68 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.44 |

| I have a sense of loss due to the injury. | 0.44 | 0.32 | 0.16 | 0.07 |

| I have a sense of loss because I cannot travel as much as I would like because of my caregiver responsibilities. | 0.72 | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.34 |

| I miss the way my life was before the injury. | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.21 | 0.02 |

| I feel like the plans I had for the rest of my life have changed since becoming a caregiver. | 0.77 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.22 |

| I have difficulty accepting how much my life has changed. | 0.79 | 0.01 | 0.15 | −0.16 |

| I feel like I do not have a fulfilling life due to my role as a caregiver. | 0.84 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| I feel that I have no hope when I think about the future of the person I care for. | 0.56 | 0.36 | −0.01 | −0.07 |

| I feel like the life I once had is now over. | 0.80 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.09 |

| I feel like my life is gone because I am providing care for someone else. | 0.89 | 0.03 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| It is difficult to accept my new way of life. | 0.83 | 0.02 | 0.11 | −0.18 |

| My life has changed for the worse due to my role as a caregiver. | 0.86 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.07 |

| I feel like I have changed the focus of my life to care for the person with the injury. | 0.46 | 0.12 | −0.01 | 0.46 |

| It is difficult to accept that I may be caring for the person with the injury for the rest of my life. | 0.74 | 0.09 | 0.03 | −0.07 |

| I limit my social activities because I have to care for the person with the injury. | 0.62 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.54 |

| I have had trouble getting my life going again since the person I care for was injured. | 0.62 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.14 |

| I neglect relationships because of my caregiving role. | 0.71 | −0.04 | 0.06 | 0.44 |

| I feel excluded from social activities because I have to care for the person with the injury. | 0.72 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.48 |

| I feel like I do not have direction in my life. | 0.87 | −0.10 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| I feel like I have lost relationships because of my caregiver responsibilities. | 0.74 | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.44 |

| I feel like my life has been turned upside down because of the injury. | 0.66 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| I feel lonely in my role as a caregiver. | 0.75 | −0.10 | 0.22 | 0.19 |

| It feels like life is going on without me. | 0.83 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| I feel as if I do not have anyone to share my life with anymore due to the injury. | 0.74 | −0.08 | 0.26 | 0.10 |

| I feel depressed because it is difficult to relate to the person I care for. | 0.48 | 0.17 | 0.35 | −0.11 |

| I feel like my life was ruined by the injury. | 0.79 | 0.02 | 0.14 | −0.12 |

| I feel like my life has been destroyed by the injury. | 0.84 | 0.01 | 0.10 | −0.09 |

| My heart breaks over the situation the person I care for is in. | 0.00 | 0.76 | −0.10 | 0.18 |

| I mourn the way the person I care for used to be before the injury. | −0.11 | 0.78 | 0.23 | −0.03 |

| I get sad when I think about the loss of abilities of the person with the injury. | −0.12 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| I get sad because it is difficult to put myself in the position of the person I care for. | 0.13 | 0.45 | 0.16 | −0.12 |

| I get sad when I think about lost relationships of the person I care for. | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.21 | 0.06 |

| I get depressed when I think about the situation the person I care for is in. | 0.22 | 0.70 | −0.07 | −0.10 |

| I feel devastated when I think that the person I care for is losing his/her future. | 0.21 | 0.78 | −0.12 | −0.06 |

| I feel sad because the person I care for has experienced changes in emotion that are a result of the injury. | −0.11 | 0.78 | 0.23 | 0.13 |

| I feel sad because the person I care for has experienced changes in memory that are a result of the injury. | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.16 | 0.12 |

| I feel sad because the person I care for may never fully recover. | 0.01 | 0.89 | −0.03 | 0.10 |

| I feel angry because the person I care for may never fully recover. | 0.20 | 0.66 | −0.04 | −0.10 |

| I feel as if the person I care for does not have a fulfilling life since the injury. | 0.06 | 0.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| It is difficult trying to accept that the person I care for may never fully recover. | 0.23 | 0.60 | 0.04 | −0.08 |

| It is difficult to accept that the person I care for is no longer the same person as before. | 0.15 | 0.53 | 0.30 | −0.13 |

| It is painful to remember who the person I care for used to be before the injury. | 0.01 | 0.50 | 0.46 | −0.06 |

| I mourn the fact that the person I care for no longer interacts with other family members in the same way as before the injury. | 0.01 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 0.20 |

| I feel like I am grieving for who the person I care for used to be. | 0.11 | 0.51 | 0.43 | 0.02 |

| I grieve about the loss of the future of the person I care for. | 0.10 | 0.77 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| I feel devastated about the changes in personality of the person I care for since their injury. | 0.08 | 0.55 | 0.36 | −0.08 |

| I feel like the life of the person I care for has been destroyed by the injury. | 0.22 | 0.60 | 0.11 | 0.03 |

| I get sad when I think about how much my relationship has changed with the person I care for since the injury. | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.53 | −0.04 |

| I feel like I am waiting for the person I care for to change back to the person she/he used to be. | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.27 | −0.19 |

| I have had to adjust to the new personality of the person I care for. | 0.00 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.20 |

| I miss the companionship I once shared with the person I care for. | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.64 | 0.00 |

| I feel like I need to get to know the person I care for again. | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.60 | 0.02 |

| I mourn the fact that the person I care for no longer interacts with me in the same way as before the injury. | 0.08 | 0.27 | 0.68 | 0.04 |

| I feel like the bond I once shared with the person I care for is gone. |

0.37 | 0.00 | 0.63 | −0.08 |

For Feelings of Loss-Self (43 items), follow-up CFA did not identify any items with low factor loadings, high residual correlations, or high correlated error modification index values. No items displayed non-monotonicity, and no items exhibited DIF. However, 13 items were deleted due to IRT-based item misfit statistics. The final Feelings of Loss-Self bank was comprised of 30 items (Table 2).

Table 2.

Unidimensional Modeling and Analyses

| Unidimensional Modeling | Initial Item Performance |

IRT Modeling |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Item pool | EFA E1/E2 ratio (criterion >4) | Percent of variance for E1 (criterion >40) |

1-factor CFA loading (criterion <.50) |

1-factor CFA residual correlation (criterion >.20) |

1-factor CFA modification index (criterion >100) |

Item-adjusted total score correlations (Criterion <.40) |

Sparse cells (criterion<10) |

Problems with monotonicity |

IRT item misfit | Ll_ Q |

Interim/Final item bank |

| Caregiver Feelings of Loss-Self | 43 items |

-- | -- | 0 items |

0 items |

0 item | 0 items |

0 items |

0 items |

13 items |

0 items |

30 items |

| Caregiver Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI | 20 items |

-- | -- | 0 items |

0 items |

1 item | 0 items |

0 items |

0 items |

0 items |

0 items |

19 items |

Note. CFA = Confirmatory Factor Analysis; EFA = Exploratory Factor Analysis; IRT = Item Response Theory

For Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI (20 items), follow-up CFA also did not identify any items with low factor loadings or high residual correlations; however, one item was excluded due to an associated high correlated error modification index value. None of the items displayed non-monotonicity, nor did they exhibit DIF. No items had statistically significant IRT-based item misfit. The final Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI bank was comprised of 19 items (Table 2).

Final Item Bank Criteria.

The final CFA model suggested good overall model fit for both Feelings of Loss-Self and Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Final Item Parameters

| Domain | Item Bank |

CFI (criterion >95) |

TLI (criterion >.95) |

CFA-based RMSEA (criterion < .15) |

Alpha Reliability (criterion > .80) |

IRT-based RMSEA (criterion < .15) |

Response Pattern Reliability (criterion > .80) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Feelings of Loss-Self |

30 items | .96 | .96 | .10 | .98 | .09 | .97 |

| Caregiver Feelings of Loss-Other |

19 items | .97 | .97 | .095 | .96 | .09 | .96 |

Note. CFI = Comparative Fit Index, TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index, RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

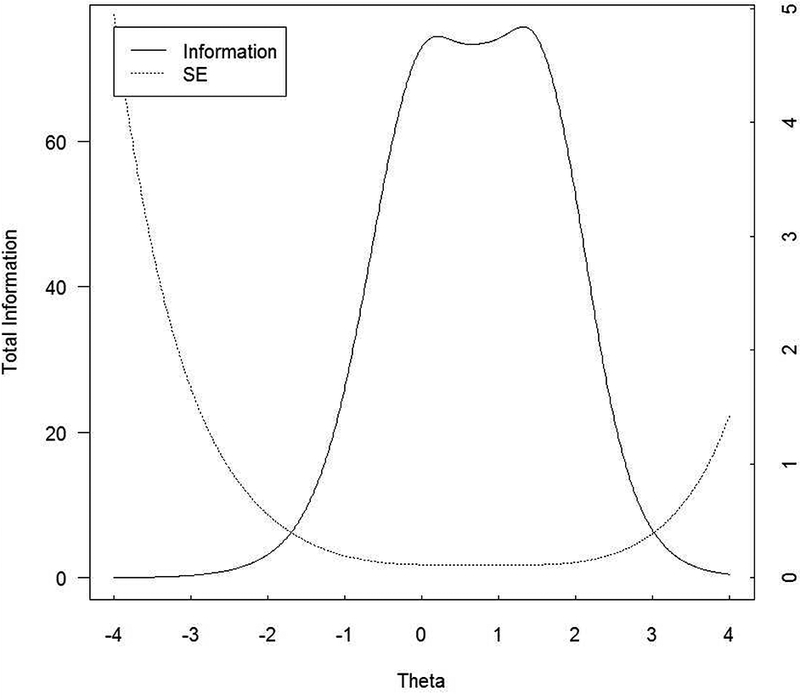

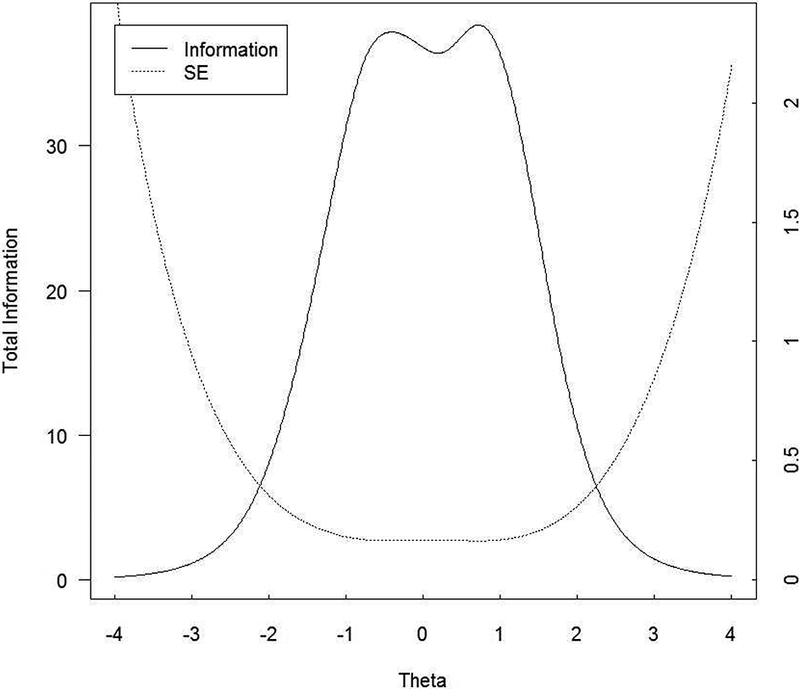

Final item banks parameter estimates are shown in Table 4. Score-level reliability for Feeling of Loss-Self was excellent from theta= −1.2 to +2.8, with expected score-level reliability ≥90; score-level reliability from the expanded theta range from −1.6 to +2.8 was very good to excellent (at least ≥.80), while score-level reliability at further expanded theta range from −2.0 to +2.8 was good to excellent (at least ≥.70). For Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI, score-level reliability was excellent from theta= −1.6 to +2.0, with expected score-level reliability ≥.90; score-level reliability at the expanded theta range from −2.0 to +2.4 was very good to excellent (at least ≥.80), while score-level reliability at the further expanded theta range from −2.4 to +2.4 was good to excellent (at least ≥.70). Figures 1 and 2 show test information plots for Feelings of Loss-Self and Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI, respectively.

Table 4.

TBI-CareQOL Item Parameters for Feelings of Loss-Self, and Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI

| Item | Slope | Threshold 1 |

Threshold 2 |

Threshold 3 |

Threshold 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEELINGS OF LOSS-SELF | |||||

| I have stopped living my life to care for the person with the injury. | 2.08 | −0.47 | 0.22 | 1.17 | 1.98 |

| It feels like I have lost my own identity because I am caring for someone else. | 3.11 | −0.43 | 0.11 | 0.98 | 1.53 |

| The responsibilities I have as a caregiver make me feel socially isolated. | 2.78 | −0.50 | 0.03 | 0.83 | 1.52 |

| I mourn for the life I used to have before the person I care for was injured. | 3.29 | −0.52 | 0.06 | 0.94 | 1.33 |

| I get depressed when I think that I am losing my future. | 3.29 | −0.11 | 0.52 | 1.28 | 1.71 |

| I feel miserable when I think about how my life has changed since the injury. | 3.37 | −0.25 | 0.42 | 1.28 | 1.70 |

| I feel sad because becoming a caregiver has changed what I expect for my future. | 3.52 | −0.40 | 0.15 | 0.98 | 1.41 |

| I feel devastated because my plans for the future have changed since the injury. | 3.51 | −0.03 | 0.55 | 1.24 | 1.73 |

| It is difficult to deal with personality changes in the person I care for. | 2.00 | −1.45 | −0.67 | 0.56 | 1.16 |

| My relationships with other people are affected because I have to care for the person with the injury. | 2.86 | −0.58 | 0.04 | 0.92 | 1.54 |

| I have a sense of loss due to the injury. | 2.25 | −0.90 | −0.28 | 0.67 | 1.31 |

| I have a sense of loss because I cannot travel as much as I would like because of my caregiver responsibilities. | 2.47 | −0.34 | 0.35 | 1.29 | 1.74 |

| I miss the way my life was before the injury. | 2.84 | −0.83 | −0.28 | 0.76 | 1.17 |

| I have difficulty accepting how much my life has changed. | 2.95 | −0.35 | 0.37 | 1.41 | 1.81 |

| I feel like I don’t have a fulfilling life due to my role as a caregiver. | 3.32 | −0.01 | 0.60 | 1.41 | 1.93 |

| I feel that I have no hope when I think about the future of the person I care for. | 2.39 | 0.09 | 0.79 | 1.69 | 2.30 |

| I feel like the life I once had is now over. | 3.50 | −0.17 | 0.35 | 0.91 | 1.37 |

| I feel like my life is gone because I am providing care for someone else. | 3.92 | 0.18 | 0.84 | 1.45 | 1.98 |

| It is difficult to accept my new way of life. | 3.23 | −0.13 | 0.59 | 1.57 | 2.08 |

| My life has changed for the worse due to my role as a caregiver. | 3.10 | 0.22 | 0.76 | 1.57 | 2.02 |

| It is difficult to accept that I may be caring for the person with the injury for the rest of my life. | 2.29 | −0.39 | 0.27 | 1.29 | 1.87 |

| I have had trouble getting my life going again since the person I care for was injured. | 2.55 | −0.35 | 0.29 | 1.26 | 1.85 |

| I neglect relationships because of my caregiving role. | 2.54 | −0.58 | 0.00 | 1.04 | 1.64 |

| I feel excluded from social activities because I have to care for the person with the injury. | 2.76 | −0.36 | 0.19 | 1.15 | 1.65 |

| I feel like I don’t have direction in my life. | 2.65 | −0.07 | 0.57 | 1.46 | 2.06 |

| I feel like I have lost relationships because of my caregiver responsibilities. | 2.76 | −0.23 | 0.30 | 1.23 | 1.62 |

| I feel like my life has been turned upside down because of the injury. | 2.59 | −0.72 | −0.23 | 0.73 | 1.33 |

| I feel lonely in my role as a caregiver. | 2.91 | −0.52 | −0.10 | 0.93 | 1.47 |

| I feel like my life was ruined by the injury. | 3.21 | 0.18 | 0.74 | 1.44 | 1.77 |

| I feel like my life has been destroyed by the injury. | 3.63 | 0.09 | 0.66 | 1.37 | 1.75 |

| FEELINGS OF LOSS-PERSON WITH TBI | |||||

| My heart breaks over the situation the person I care for is in. | 1.67 | −1.92 | −1.19 | 0.10 | 0.68 |

| I mourn the way the person I care for used to be before the injury. | 2.72 | −1.28 | −0.73 | 0.33 | 0.84 |

| I get sad when I think about the loss of abilities of the person with the injury. | 3.24 | −1.50 | −0.96 | 0.14 | 0.72 |

| I get sad because it is difficult to put myself in the position of the person I care for. | 1.53 | −0.84 | 0.11 | 1.32 | 2.12 |

| I get sad when I think about lost relationships of the person I care for. | 2.48 | −0.92 | −0.37 | 0.57 | 1.18 |

| I get depressed when I think about the situation the person I care for is in. | 2.57 | −0.77 | −0.18 | 0.74 | 1.29 |

| I feel devastated when I think that the person I care for is losing his/her future. | 3.03 | −0.58 | −0.04 | 0.73 | 1.17 |

| I feel sad because the person I care for has experienced changes in memory that are a result of the injury. | 2.27 | −1.76 | −1.24 | −0.09 | 0.61 |

| I feel sad because the person I care for may never fully recover. | 3.05 | −1.13 | −0.61 | 0.22 | 0.65 |

| I feel angry because the person I care for may never fully recover. | 2.07 | −0.45 | 0.05 | 0.98 | 1.40 |

| I feel as if the person I care for does not have a fulfilling life since the injury. | 2.47 | −0.72 | −0.25 | 0.74 | 1.34 |

| It is difficult trying to accept that the person I care for may never fully recover. | 2.40 | −0.78 | −0.18 | 0.86 | 1.36 |

| It is difficult to accept that the person I care for is no longer the same person as before. | 2.75 | −0.94 | −0.33 | 0.75 | 1.25 |

| It is painful to remember who the person I care for used to be before the injury. | 2.38 | −0.77 | −0.31 | 0.75 | 1.16 |

| I mourn the fact that the person I care for no longer interacts with other family members in the same way as before the injury. | 2.12 | −0.78 | −0.32 | 0.69 | 1.18 |

| I feel like I am grieving for who the person I care for used to be. | 3.08 | −0.64 | −0.18 | 0.72 | 1.16 |

| I grieve about the loss of the future of the person I care for. | 3.70 | −0.71 | −0.26 | 0.67 | 0.99 |

| I feel devastated about the changes in personality of the person I care for since their injury. | 2.77 | −0.64 | −0.03 | 0.83 | 1.28 |

| I feel like the life of the person I care for has been destroyed by the injury. | 2.83 | −0.63 | −0.18 | 0.59 | 1.14 |

Note. Items that are indicated in bold were selected for inclusion on the 6-item, Feelings of Loss-Self, and Feelings of Loss-Person with the TBI short forms

Figure 1. Feelings of Loss-Self Test Information Plot.

In general, total information should be ≥ 10.0 and the standard error should be ≤ 0.32 (this provides a reliability of 0.9). This figure shows excellent total information and standard error for Feelings of Loss-Self scale scores between −1.2 and +2.8.

Figure 2. Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI Test Information Plot.

In general, total information should be ≥ 10.0 and the standard error should be ≤ 0.32 (this provides a reliability of 0.9). This figure shows excellent total information and standard error for Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI scale scores between −1.6 and +2.0.

CAT Simulation.

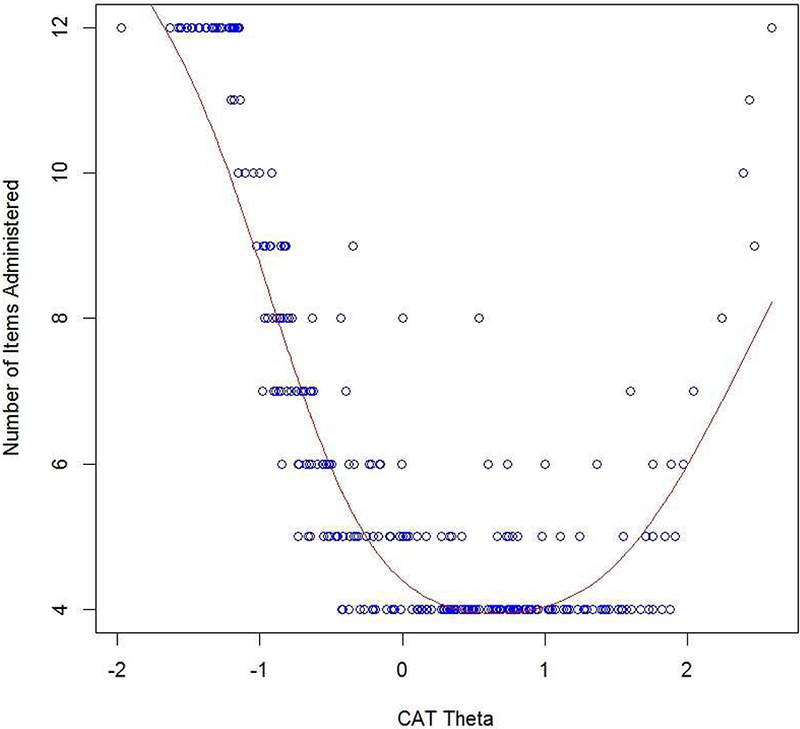

For Feelings of Loss-Self, the correlation between item bank and CAT scores was 0.97 (Figure 3). The standard deviation of the differences between full item bank and CAT scores was 0.23, and the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the two score sets was 0.23. The most common CAT length was 4 items (n=298, 53.2%), the second most common length was 5 items (n=80, 14.3%), and the third most common length was 12 items (n=79, 14.1%), with 12-item CATs being the longest CATs administered. The mean number of items administered for the Feelings of Loss-Self CAT was 5.9. For 4-item CATs, observed thetas ranged from −0.42 to +1.88; the theta range for 5-item CATs was similar to (though somewhat wider than) the theta range for the 4-item CATs (−0.73 to +1.91). Observed thetas for 12-item CATs were distributed bimodally, with low thetas ranging from −1.97 to −1.14 and high thetas were at +2.60. Twelve-item CATs only occurred when measuring extreme low and extreme high levels of Feelings of Loss-Self.

Figure 3. Feelings of Loss-Self Number of CAT Items by CAT Theta.

This figure shows the number of CAT items used for different scale scores in standard deviation units: at approximately ≤−1.0 SD units and ≥+2.5 SD units the maximum of 12 items from the item bank were used by the CAT; from approximately −0.5 to +2.0 SD units the CAT tended to use the minimum of four items from the item bank.

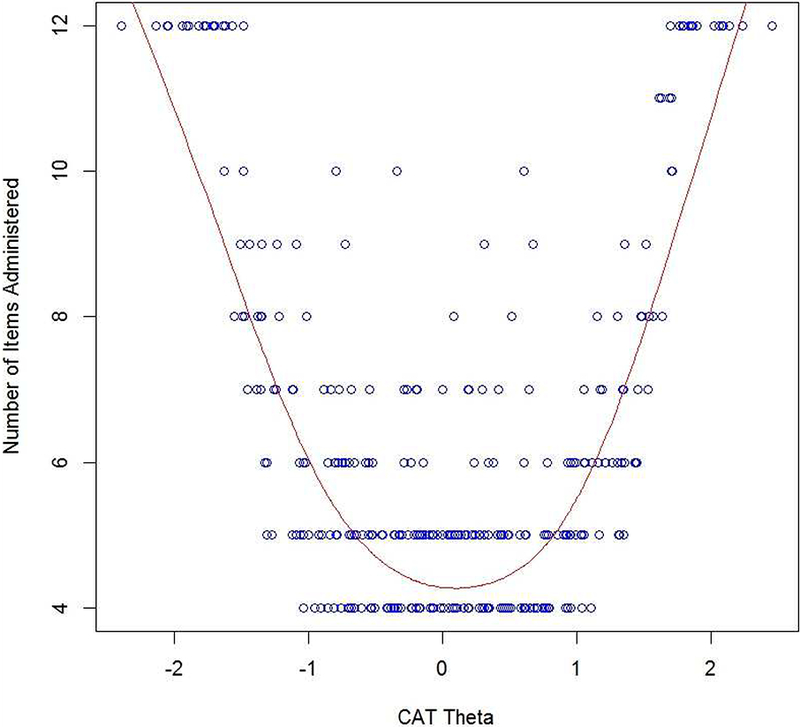

For Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI, the item bank scores vs. CAT scores correlation was 0.98 (Figure 4). The standard deviation of the differences between full item bank and CAT scores was 0.22, as was the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the two score sets. The three most common CAT lengths were 4 items (n=256, 45.7%), 5 items (n=128, 22.9%), and 12 items (n=51, 9.1%); 12-item CATs were the longest CATs administered. The mean items administered for the Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI CAT was 5.7. For 4-item CATs, observed thetas ranged from −1.04 to +1.11; the theta range for 5-item CATs was similar (−1.31 to +1.35). Observed thetas for 12-item CATs were distributed bimodally: low thetas ranged from −2.39 to −1.48, while high thetas ranged from +1.70 to +2.46. That is, 12-item CATs occurred when measuring extreme low and extreme high levels of Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI.

Figure 4. Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI Test Information Plot.

This figure shows the number of CAT items used for different scale scores in standard deviation units: at approximately ≤−1.5 SD units and ≥+1.5 SD units the maximum of 12 items from the item bank were used by the CAT; from approximately −1.0 to +1.0 SD units the CAT tended to use the minimum of four items from the item bank.

Short Form Development.

Clinical experts selected and approved the content representativeness of the 6-item SFs of the two measures. The reliability of these SFs was examined. For Feelings of Loss-Self, score-level reliability was excellent in the theta range from −0.4 to +2.0, with expected score-level reliability ≥.90; score-level reliability in the extended theta range from −1.2 to +2.4 was very good to excellent (at least ≥.80). For Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI, score-level information was excellent in the theta range from −1.2 to +1.2, with expected score-level reliability ≥.90; score-level reliability in the extended theta range from −1.6 to +1.6 was very good to excellent (at least ≥ 80), while score-level reliability in the further extended theta range from −2.0 to +2.0 was good to excellent (at least ≥.70). Three-week test-retest for SFs was very good for both measures: for Feelings of Loss-Self, r=.87; for Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI, r=.85. Summed score to t score conversions for both SF measures are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Short-Form Summed Score to t Score Conversion Table for Feelings of Loss-Self and Feelings

| Feelings of Loss-Self | Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Score |

T-score | SE * | T-score | SE * |

| 6 | 35.24 | 5.38 | 31.14 | 4.96 |

| 7 | 40.62 | 3.64 | 35.87 | 3.56 |

| 8 | 42.79 | 3.39 | 38.08 | 3.38 |

| 9 | 44.87 | 2.96 | 40.12 | 3.06 |

| 10 | 46.47 | 2.79 | 41.71 | 2.95 |

| 11 | 47.93 | 2.63 | 43.20 | 2.82 |

| 12 | 49.27 | 2.54 | 44.54 | 2.77 |

| 13 | 50.55 | 2.48 | 45.82 | 2.74 |

| 14 | 51.78 | 2.44 | 47.05 | 2.73 |

| 15 | 52.97 | 2.41 | 48.26 | 2.73 |

| 16 | 54.13 | 2.39 | 49.44 | 2.74 |

| 17 | 55.27 | 2.38 | 50.61 | 2.74 |

| 18 | 56.38 | 2.37 | 51.75 | 2.74 |

| 19 | 57.48 | 2.36 | 52.90 | 2.73 |

| 20 | 58.57 | 2.34 | 54.03 | 2.73 |

| 21 | 59.65 | 2.33 | 55.17 | 2.72 |

| 22 | 60.72 | 2.32 | 56.32 | 2.72 |

| 23 | 61.81 | 2.32 | 57.48 | 2.73 |

| 24 | 62.92 | 2.34 | 58.69 | 2.78 |

| 25 | 64.07 | 2.37 | 59.93 | 2.84 |

| 26 | 65.31 | 2.43 | 61.31 | 3.02 |

| 27 | 66.66 | 2.54 | 62.70 | 3.13 |

| 28 | 68.25 | 2.76 | 64.59 | 3.52 |

| 29 | 70.12 | 2.96 | 66.19 | 3.63 |

| 30 | 74.11 | 4.16 | 70.31 | 4.82 |

SE = Standard error

Discussion

Findings supported the development of two new PROs to assess feelings of loss in caregivers of individuals with TBI: TBI-CareQOL Feelings of Loss-Self and TBI-CareQOL Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI. These new measures have several strengths. First, they were developed in accordance with established measurement development standards.36 Second, these measures can be administered as a CAT or a 6-item SF. CAT administration minimizes participant burden without sacrificing test sensitivity, as only the most relevant and informative items are administered to each participant. Each item is selected based on a participant’s previous response until established cutoff criterion are met - either a minimum specified standard error (typically <3 on a T-score metric) or a maximum number of items administered (typically 12 items). Since the corresponding 6-item SF was developed and selected using IRT (where each individual test item can be used to generate a score), a meaningful score can be derived, which is an advantage over measures developed using classical test theory analytic approaches.

Data from this study provide additional strong psychometric support for these measures. First, reliability is supported by excellent response pattern reliability for the CAT administrations (r>.95 37) and internal consistency reliability for the SFs (r>.9537). In addition, both measures demonstrated very good 3-week test-retest reliability for the 6-item static SF (r>.8537).Construct validity was supported by employing defined sets of unidimensional items (as determined by both exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses). Furthermore, all items were free of DIF (i.e., there was no bias for age, education, or caregiver type: civilian vs SMV).

Study Limitations

While this study exhibits several strengths, there are limitations. First, although CAT administration is generally more efficient than traditional administration approaches, responders at either extreme end of the trait (for both Feelings of Loss-Self and Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI) will often require up to 12 items to estimate a score. Furthermore, more items will be administered in a CAT administration if responses are inconsistent. Regardless, CAT simulation data suggest that the CAT performs well for individuals with scale scores between 1.02 and +2.47 (83.9%) for Feelings of Loss-Self (i.e., for CATs with <10 items administered) and between −1.55 and +1.64 (88.9%) for Feelings of Loss-Person with TBI (<10 items administered). Although the predominance of female caregivers in our sample is consistent with other published studies 11,16,58–65, generalizability to male caregivers is uncertain. Similarly, consistent with previous studies64,65, the majority of the SMV caregivers were spouses, which limits generalizability to parent caregivers. Finally, additional work is needed to establish more comprehensive validity data and responsiveness to change data for these measures.

Conclusions

These are the first caregiver-specific PRO measures of feelings of loss, and they are among the first CATs that have been used to evaluate HRQOL in caregivers of individuals with TBI. Additional research on these measures could focus on how the scores of these measures correlate to the caregiver’s and person with TBI’s emotional status and functional outcomes. Understanding these relationships could potentially identify at-risk individuals with difficulty adjusting to changes in roles and relationships after TBI. Such information could guide treatment professionals in targeting treatment for caregivers and ultimately maximize the rehabilitation process and emotional well-being of both caregivers and persons with TBI.

Highlights.

Feelings of loss are common in caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injury

Two new self-report measures of caregiver feelings of loss were developed

These self-report measures can help identify feelings of entrapment in caregivers

Acknowledgements:

Work on this manuscript was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)- National Institute of Nursing Research (R01NR013658), the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000433), and the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center (DVBIC). We thank the investigators, coordinators, and research associates/assistants who worked on this study, the study participants, and organizations who supported recruitment efforts. The University of Michigan Research Team would also like to thank the Hearts of Valor and the Brain Injury Association of Michigan for assistance with community outreach for ecruitment efforts at this site.

List of Abbreviations:

- CAT

Computer Adaptive Test

- CTT

Classical Test Theory

- CFA

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- CFI

Confirmatory Fit Index

- DIF

Differential Item Functioning

- EFA

Exploratory Factor Analysis

- GRM

Graded Response Model

- HRQOL

Health-Related Quality of Life

- IRT

Item Response Theory

- PRO

Patient-Reported Outcome

- PROMIS

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- RMSD

Root Mean Square Deviation

- RMSEA

Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation

- SE

Standard Error

- SF

Short Form

- SMV

Service Member/Veteran

- TBI

Traumatic Brain Injury

- TBI-CareQOL

Traumatic Brain Injury Caregiver Quality of Life

- TLI

Tucker Lewis Index

Footnotes

TBI-CareQOL Site Investigators and Coordinators: Noelle Carlozzi, Anna Kratz, Amy Austin, Mitchell Belanger, Micah Warschausky, Siera Goodnight, Jennifer Miner (University of Michigan, Ann, Arbor, MI); Angelle Sander (Baylor College of Medicine and TIRR Memorial Hermann, Houston, TX), Curtisa Light (TIRR Memorial Hermann, Houston, TX); Robin Hanks, Daniela Ristova-Trendov (Wayne State University/Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan, Detroit, MI); Nancy Chiaravalloti, Dennis Tirri, Belinda Washington (Kessler Foundation, West Orange, NJ); Tracey Brickell, Rael Lange, Louis French, Rachel Gartner, Megan Wright, Angela Driscoll, Diana Nora, Jamie Sullivan, Nicole Varbedian, Johanna Smith, Lauren Johnson, Heidi Mahatan, Mikelle Mooney, Mallory Frazier, Zoe Li, and Deanna Pruitt (Walter Reed National Military Medical Center/Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, Bethesda, MD)

Disclaimer:

The identification of specific products or scientific instrumentation does not constitute endorsement or implied endorsement on the part of the author, DoD, or any component agency. While we generally exercise reference to products companies, manufacturers, organizations etc. in government produced works, the abstracts produced and other similarly situated research presents a special circumstance when such a product inclusions become an integral part of the scientific endeavor.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Langlois JA, Kegler SR, Butler JA, et al. Traumatic brain injury-related hospital discharges. Results from a 14-state surveillance system, 1997. MMWR Surveillance summaries : Morbidity and mortality weekly report Surveillance summaries / CDC. 2003;52(4):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DVBIC. DoD Worldwide Numbers for TBI. 2015; http://dvbic.dcoe.mil/dod-worldwide-numbers-tbi. Accessed 02/17, 2015.

- 3.Sosin DM, Sniezek JE, Waxweiler RJ. Trends in death associated with traumatic brain injury, 1979 through 1992. Success and failure. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1995;273(22):1778–1780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thurman D, Coronado V, Selassie AW. Epidemiology of Traumatic Brain Injury In: Zasler ND, Katz DI, Zafonte RD, eds. Brain injury medicine : principles and practice. 2nd ed. New York: Demos; 2007:373–405. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corrigan JD, Cuthbert JP, Harrison-Felix C, et al. US population estimates of health and social outcomes 5 years after rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2014;29(6):E1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cuthbert JP, Pretz CR, Bushnik T, et al. Ten-Year Employment Patterns of Working Age Individuals After Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(12):2128–2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahm J, Ponsford J. Long-term employment outcomes following traumatic brain injury and orthopaedic trauma: A ten-year prospective study. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47(10):932–940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jourdan C, Bayen E, Pradat-Diehl P, et al. A comprehensive picture of 4-year outcome of severe brain injuries. Results from the PariS-TBI study. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59(2):100–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verhaeghe S, Defloor T, Grypdonck M. Stress and coping among families of patients with traumatic brain injury: A review of the literature. Journal of clinical nursing. 2005;14(8):1004–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin AM, Carey JL. The adversarial alliance: developing therapeutic relationships between families and the team in brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Injury. 1993;7(1):45– 51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sander AM, Caroselli JS, High WM, Becker C, Neese L, Scheibel R. Relationship of family functioning to progress in a post-acute rehabilitation programme following traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2002;16(8):649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelletier PM, Alfano DP. Depression, social support, and family coping following traumatic brain injury. Brain and Cognition. 2000;44(1):45–49. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Florian V, Katz S, Lahav V. Impact of traumatic brain damage on family dynamics and functioning: A review. Brain Injury. 1989;3(3):219–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sander AM, Maestas KL, Sherer M, Malec JF, Nakase-Richardson R. Relationship of caregiver and family functioning to participation outcomes after postacute rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury: a multicenter investigation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(5):842–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sady MD, Sander AM, Clark AN, Sherer M, Nakase-Richardson R, Malec JF. Relationship of preinjury caregiver and family functioning to community integration in adults with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(10):1542–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vangel SJ Jr., Rapport LJ, Hanks RA. Effects of family and caregiver psychosocial functioning on outcomes in persons with traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2011;26(1):20–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith AM, Schwirian PM. The relationship between caregiver burden and TBI survivors’ cognition and functional ability after discharge. Rehabilitation Nursing. 1998;23(5):252– 257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carlozzi NE, Brickell TA, French LM, et al. Caring for our wounded warriors: A qualitative examination of health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with military-related traumatic brain injury. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development. 2016;53(6):669–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlozzi NE, Kratz AL, Sander AM, et al. Health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: development of a conceptual model. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2015;96(1):105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carlozzi NE, Kratz AL, Sander AM, et al. Health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: Development of a conceptual model. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2015;96(1):105–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marsh NV, Kersel DA, Havill JH, Sleigh JW. Caregiver burden at 1 year following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1998;12(12):1045–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meuser TM, Marwit SJ. A comprehensive, stage-sensitive model of grief in dementia caregiving. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):658–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boss P Ambiguous Loss. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boss P, Couden BA. Ambiguous loss from chronic physical illness: clinical interventions with individuals, couples, and families. Journal of clinical psychology. 2002;58(11):1351– 1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanders S, Corley CS. Are they grieving? A qualitative analysis examining grief in caregivers of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Work Health Care. 2003;37(3):35–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karger CR. Emotional experience in patients with advanced Alzheimer’s disease from the perspective of families, professional caregivers, physicians, and scientists. Aging Ment Health. 2016:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bjorge H, Saeteren B, Ulstein ID. Experience of companionship among family caregivers of persons with dementia: A qualitative study Dementia (London). 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutchinson K, Roberts C, Kurrle S, Daly M. The emotional well-being of young people having a parent with younger onset dementia. Dementia (London). 2016;15(4):609–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanders S, Ott CH, Kelber ST, Noonan P. The experience of high levels of grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia. Death Stud. 2008;32(6):495–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank JB. Evidence for grief as the major barrier faced by Alzheimer caregivers: a qualitative analysis. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2007;22(6):516–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massimo L, Evans LK, Benner P. Caring for loved ones with frontotemporal degeneration: the lived experiences of spouses. GeriatrNurs. 2013;34(4):302–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loos C, Bowd A. Caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease: some neglected implications of the experience of personal loss and grief. Death Stud. 1997;21(5):501– 514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beeson RA. Loneliness and depression in spousal caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease versus non-caregiving spouses. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2003;17(3):135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hogsnes L, Norbergh KG, Danielson E, Melin-Johansson C. The Shift in Existential Life Situations of Adult Children to Parents with Dementia Relocated to Nursing Homes. Open Nurs J. 2016;10:122–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.PROMIS® Instrument Development and Psychometric Evaluation Scientific Standards. http://www.nihpromis.org/Documents/PROMIS_Standards_050212.pdf.

- 37.Carlozzi NE, Kallen MA, Hanks R, et al. The TBI-CareQOL Measurement System: Development and validation of health-related quality of life measures for caregivers of individuals with civilian- and military-related traumatic brain injury Under Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested in its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2010;63:1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): 567 Progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Medical Care. 2007;45(Suppl 1):S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corrigan JD, Cuthbert JP, Whiteneck GG, et al. Representativeness of the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2012;27(6):391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlozzi NE, Brickell TA, French LM, et al. Caring for our wounded warriors: A qualitative examination of health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with military-related traumatic brain injury. Journal of rehabilitation research and development. 2016;53(6):669–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cappelleri JC, Jason Lundy J, Hays RD. Overview of classical test theory and item response theory for the quantitative assessment of items in developing patient-reported outcomes measures. Clin Ther. 2014;36(5):648–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McDonald RP. Test theory: A unified treatment. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cook KF, Kallen MA, Amtmann D. Having a fit: Impact of number of items and distribution of data on traditional criteria for assessing IRT’s unidimensionality assumption. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18(4):447–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reise SP, Morizot J, Hays RD. The role of the bifactor model in resolving dimensionality issues in health outcomes measures. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16 Suppl 1:19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47.TestGraf [computer program]. Canada: McGill University; August 1, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samejima F, van der Liden WJ, Hambleton R. The graded response model In: van der Liden WJ, ed. Handbook of modern item response theory. NY, NY: Springer; 1996:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- 49.IRTPRO for Windows [Computer software] [computer program]. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 50.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [computer program]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi SW, Gibbons LE, Crane PK. Lordif: An R package for detecting differential item functioning using iterative hybrid ordinal logistic regression/item response theory and monte carlo simulations. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;39(8):1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Jolley L, van Belle G. Differential item functioning analysis with ordinal logistic regression techniques. DIFdetect and difwithpar. Medical Care. 2006;44(11 Suppl 3):S115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, Second Edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bentler PM. Comparative Fit Indexes in Structural Models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990; 107(2):238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling-a Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1): 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hatcher L A step-by-step approach to using SAS for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Choi SW. Firestar: Computerized Adaptive Testing Simulation Program for Polytomous Item Response Theory Models. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2009;33(8):644–645. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davis LC, Sander AM, Struchen MA, Sherer M, Nakase-Richardson R, Malec JF. Medical and psychosocial predictors of caregiver distress and perceived burden following traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2009;24(3):145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marsh NV, Kersel DA, Havill JA, Sleigh JW. Caregiver burden during the year following severe traumatic brain injury. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2002;24(4):434–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Doser K, Norup A. Caregiver burden in Danish family members of patients with severe brain injury: The chronic phase. Brain Inj. 2016;30(3):334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powell JM, Fraser R, Brockway JA, Temkin N, Bell KR. A Telehealth Approach to Caregiver Self-Management Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;31(3):180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ergh TC, Hanks RA, Rapport LJ, Coleman RD. Social support moderates caregiver life satisfaction following traumatic brain injury. Journal of clinical and experimental neuropsychology. 2003;25(8): 1090–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ergh TC, Rapport LJ, Coleman RD, Hanks RA. Predictors of caregiver and family functioning following traumatic brain injury: social support moderates caregiver distress. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2002; 17(2):155–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Griffin JM, Friedemann-Sanchez G, Jensen AC, et al. The invisible side of war: families caring for US service members with traumatic brain injuries and polytrauma. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2012;27(1):3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moriarty H, Winter L, Robinson K, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Evaluate the Veterans’ In-home Program for Military Veterans With Traumatic Brain Injury and Their Families: Report on Impact for Family Members. PM R. 2016;8(6):495–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]