Abstract

NAD+ metabolism is integrally connected with the mechanisms of action of radiation therapy and is altered in many radiation-resistant tumors. This makes NAD+ metabolism an ideal target for therapies that increase radiation sensitivity and improve patient outcomes. This review provides an overview of NAD+ metabolism in the context of the cellular response to ionizing radiation, as well as current therapies that target NAD+ metabolism to enhance radiation therapy responses. Additionally, we summarize state-of-the-art methods for measuring, modeling, and manipulating NAD+ metabolism, which are being used to identify novel targets in the NAD+ metabolic network for therapeutic interventions in combination with radiation therapy.

Introduction

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is an omnipresent molecule which acts as both an electron-carrying cofactor for oxidation-reduction reactions, as well as a substrate for many metabolic and signaling processes [1]. NAD+ metabolism has been implicated in several important biological processes, including energy production, cell signaling, and redox homeostasis. This metabolism is altered in natural physiological processes such as aging, metabolic diseases (e.g., pellagra and type 2 diabetes), and many forms of cancer [2]. Because of its essential role in the pathophysiology of many prevalent diseases, NAD+ metabolism remains an exciting yet challenging target for selective therapies.

Many processes in the NAD+ metabolic network are disrupted in cancer, including the production of NAD+ intermediates and consumption of NAD+ by signaling processes necessary for tumor cell survival [3, 4]. Ionizing radiation therapy used in cancer treatment further disrupts NAD+ metabolism and the processes regulating NAD+ production and consumption. Radiation-resistant tumors are capable of maintaining adequate NAD+ production while overcoming the damaging effects of radiation on DNA damage and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production [5]. Thus, it is expected that selectively targeting NAD+ metabolism will sensitize tumor cells to ionizing radiation, and that these targeting agents can be combined with radiation therapy to improve cancer patient outcomes. Current NAD+-targeting chemotherapies have shown very promising results as radiation sensitizers, and novel methods of measuring and modeling NAD+ metabolism will both improve our biological understanding and provide new insights into targeting NAD+ metabolism to enhance radiation therapy responses.

NAD+ Metabolism and its Role in Radiation Response

NAD+ synthesis

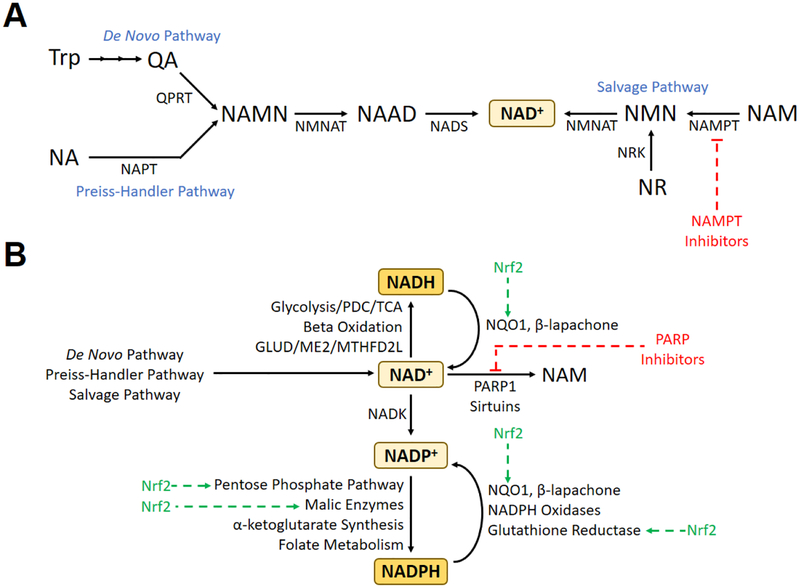

Nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NAMN), a precursor of NAD+, can be formed from either quinolinic acid (originating from tryptophan) in the de novo NAD+ synthesis pathway, or from nicotinic acid in the Preiss-Handler pathway (Figure 1A) [6, 7]. NAMN is then converted to nicotinate adenine dinucleotide (NAAD) by nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyl transferase (NMNAT), and then converted into NAD+ by NAD+ synthase. By utilizing salvage pathways, NAD+ can also be produced using available precursors such as nicotinamide (NAM) and nicotinamide riboside (NR). The rate-limiting enzyme in these salvage pathways is nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferanse (NAMPT), which converts nicotinamide to nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) [8].

Figure 1.

(A) Major biochemical pathways for the production of NAD+. (B) Major inputs and outputs to/from the cellular pools of NAD+, NADH, NADP+, and NADPH, including pathways and therapies pertinent to the cellular response to radiation therapy. Abbreviations: GLUD, glutamate dehydrogenase; ME2, malic enzyme 2; NA, nicotinic acid; MTHFD2L, methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2-like protein; NAAD, nicotinic acid dinucleotide; NADK, NAD+ kinase; NADS, NAD+ synthase; NAM, nicotinamide; NAMN, nicotinic acid mononucleotide; NAMPT, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; NAPT, nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase; NMN, nicotinamide mononucleotide; NMNAT, nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase; NQO1, NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1; NR, nicotinamide riboside; Nrf2, nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2; NRK, nicotinamide riboside kinase; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase; PDC, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; QA, quinolinic acid; QPRT, quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; Trp, tryptophan.

NAMPT inhibitors are effective inhibitors of NAD+ synthesis and are being used in clinical trials for cancer treatment due to the higher demand of tumor cells for NAD+ [9]. Since NAD+ salvage pathways may be overutilized compared to the de novo and Preiss-Handler pathways in some cancers, NAMPT is a very promising target for cancer therapies [10]. Alternatively, because of its utilization in both de novo and salvage pathways, NMNAT may be an effective target for suppression of NAD+ synthesis as well. Complete loss of function of NMNAT in Drosophila causes severe Wallerian degeneration, whereas NMNAT overexpression is neuroprotective and associated with decreased levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS); however, it is unclear whether these effects are due to changes in NAD+ levels through increased biosynthesis, increases in the NADH/NAD+ ratio, or both [11, 12].

Redox cycling of NAD+

Glucose oxidation supplies a significant amount of energy for the transfer of electrons from NAD+ to NADH (Figure 1B). Glycolysis via glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), oxidative carboxylation of pyruvate via the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC), and the citric acid cycle via isocitrate dehydrogenase isoform 3 (IDH3), the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex (αKGDH), and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) produce a combined 10 NADH per glucose molecule. In addition, beta oxidation of fatty acid molecules provides energy for NAD+ reduction via 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase. Other enzymes that are involved in reduction of NAD+ to NADH include glutamate dehydrogenase (GLUD), malic enzyme (ME) and methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2-like protein (MTHFD2L). Whereas some enzymes are specific to the NAD+ cofactor (including ME2), others can non-specifically reduce both NAD+ and NADP+ (including GLUD1/2) with varying catalytic efficiencies. Cytosolic and mitochondrial NADH can be exchanged via the malate-aspartate and glycerol-3-phosphate shuttles [6]. The reduced form of NADPH is the dominant intracellular form (NADP+/NADPH ~ 1:100) while the oxidized form of NAD+ is maintained at much higher levels than reduced NADH (NAD+/NADH ~ 3 to >100, depending on subcellular compartment as well as free versus protein-bound states) [13, 14].

Role of NAD+ in radiation response

Oxidative stress caused by ionizing radiation causes release of the transcription factor, Nrf2, by Keap1 in the cytoplasm, allowing Nrf2 translocation to the nucleus [15]. Nrf2 binds to the antioxidant response element (ARE), a transcription factor binding site found in the promoter region of many genes involved in antioxidation and detoxification, and increases expression of these genes [16]. The canonical Nrf2-induced gene product, the cytosolic flavoenzyme NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), uses NADH (as well as NADPH) to reduce and detoxify quinone compounds that cause ROS generation and further oxidative stress [17]. Nrf2 also increases the concentration of reduced NADPH by increasing expression of NADP+ reducing enzymes, including G6PD, PGD, and ME1 [18, 19]. Increased levels of NADPH exert antioxidant effects by providing reducing equivalents for reduction of oxidized glutathione by glutathione reductase, as well as recycling of peroxiredoxins through the thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase systems in various subcellular compartments. NAD+ can contribute to the NADPH pool via phosphorylation by NAD+ kinase into NADP+. The promoter of IDH3A contains an ARE, and increased IDH3A expression may promote NADH production in response to oxidative stress [20].

Ionizing radiation causes significant DNA damage, including the formation of single-stranded DNA breaks (SSBs). The DNA single-strand break recognition domain of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) recognizes these SSBs within seconds of damage, causing the formation of a PARP1 homodimer at the site of damage [21, 22]. By catalyzing the breakdown of NAD+ into ADP-ribose and nicotinamide, PARP1 promotes the poly ADP-ribosylation of other target proteins as needed for DNA repair, as well as itself, which causes conformation changes in the PARP enzyme and inactivates it to allow for repair. PARP-mediated ADP ribosylation causes recruitment of XRCC1, DNA polymerase β, and DNA ligase III to repair the SSBs. DNA damage in the form of double-stranded DNA breaks (DSBs) can cause activation of sirtuins, which are involved in a number of cellular processes, including the repair of DSBs [23]. Sirtuins catalyze the deacetylation of lysine residues on proteins; the acetyl groups are transferred to NAD+, resulting in the breakdown of NAD+ into nicotinamide and O-acetyl-ADP-ribose [24].

The activation of both PARP1 and sirtuins by ionizing radiation causes a significant depletion of cellular stores of NAD+ [25]. These stores can be replenished by increasing flux through the NAD+ salvage pathways. However, consumption of ATP by NMNAT, one of the critical enzymes in NAD+ salvage, causes significant depletion of ATP stores. PARP’s role in deciding cell fate depends on the type, duration, and strength of the stress stimuli, as well as the metabolic and proliferative status of the cell [26]. In the presence of a low level of DNA damage, PARP activation may promote cell survival; on the other hand, the presence of widespread DNA damage causes PARP hyperactivation, severe NAD+/ATP depletion, and programmed necrosis [27].

Sensors and Modulators of NAD+ and NADH

Measurement of NAD+ and NADH in cells and tissue lysates

NAD+ and NADH have been measured in cell and tissue lysates using enzymatic cycling assays coupled to absorbance or fluorescence detection methods, capillary electrophoresis [28], high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [29], and high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [30] (Table 1). As NAD+ and related metabolites are reactive and vary in cellular concentration from ~1 μM to ~1 mM, these methods face many technical challenges [30]. Enzymatic cycling assays are limited in sensitivity, LC-based methods can be compromised in complex samples, and even though mass spectrometry accurately measures small molecules in complex samples, the conditions and separation of metabolites need to be optimized [30]. Additionally, for all these methods, proper extraction and preservation of the metabolites to avoid degradation and interconversion is essential for accuracy of the analysis [31].

Table 1.

Methods for measuring NAD(H) redox state in various experimental settings.

| In vitro | Measurement | Fluorescence | Ratiometric | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autofluorescence [36] | NADH | Absorbance 340 nm; emission 460 nm | - | Weak signal, overlap with NADPH spectra, difficulties separating mitochondrial and cytosolic signals |

| NAD(H) redox sensors | ||||

| Frex [37] | NADH | Excitation 420 nm and 500 nm, emission 518 nm | Yes | pH-sensitive |

| Peredox [38] | NAD+/NADH | Excitation 400 nm, emission 510 nm | No | High affinity for the NADH can lead to saturation |

| rexYFP [39] | NAD+/NADH | Excitation 419 nm, emission 516 nm | No | pH-sensitive |

| SoNar [40] | NAD+ and NADH | Excitation 420 nm and 485 nm, emission 518 nm | Yes | Fluorescence excited at 485 nm is pH-sensitive |

| NAD+ sensor [41] | NAD+ | Excitation 405 nm and 500, emission 520 nm | Yes | Slightly temperature sensitive |

| In tissue or cell lysates | Measurement | Limitations | In vivo | Measurement | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic cycling assays | NAD+ and NADH | Sensitivity | NMR | ||

| HPLC [29] | NAD+ | Capacity for complex samples | 31P [42] | NAD+ and NADH | Spectral overlap |

| LC-MS [30] | NAD+ and NADH | Optimization for complex samples | 1P [43] | NAD+ | Partial NAD+ invisibility |

| SoNar [35] | NAD+ and NADH | SoNar’s coding DNA needs to be integrated into the genome |

Cellular measurement

In this section we outline the current approaches for measuring intracellular NAD+, NADH, or their ratios. These were recently reviewed in more detail [32–34].

Autofluorescence detection.

Cellular NADH can be measured directly based on its ability to absorb light at 340 nm and emit fluorescence at 460 nm. This weak endogenous fluorescence has been studied by single-photon or multiphoton excitation, but these studies have been limited by sensitivity of these methods and cell injury caused by ultraviolet irradiation [35]. The spectral properties of NADH are identical to those of NADPH, and thus the detectable fluorescence signal reflects both NADH and NADPH in cells. The contributions of each to the total signal can be separated using fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) [34, 36]. Also, it has been very difficult to separate cytosolic signals from the intense mitochondrial signals because intrinsic NADH and NADPH fluorescence signals mostly originate from the mitochondria [32].

Genetically encoded NAD+ and NADH sensors.

Compared to endogenous NAD(P)H fluorescence, genetically encoded NAD+ and NADH sensors provide alternatives with considerable advantages. The genetically encoded sensors produce higher fluorescence compared to NAD(P)H autofluorescence, improving the sensitivity of assays. Additionally, they also enable detection of NAD+ and NADH with high selectivity and without significant interference from NADPH [32–34]. Currently there are four genetically encoded NADH sensors: Frex [37], Peredox [38], rexYFP [39] and SoNar [40]. These sensors are based on the different members of the Rex-family proteins that are fused with circularly permuted fluorescent proteins (cpFPS). The Rex proteins have much higher affinity to NADH than NAD+, and in bacteria function as gene repressors that sense the NAD+/NADH redox state. Frex, rexYFP and SoNar detection is based on the yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), which makes them sensitive to pH changes, whereas Peredox contains a pH-insensitive circular permutated T-sapphire fluorescent protein to eliminate the pH sensitivity. Frex measures NADH, whereas Peredox and rexYFP sense shifts in NAD+/NADH ratio. SoNar is the only sensor that responds to both NADH and NAD+, but as its signal remains unaffected by the total NAD(H) pool, it cannot be used to quantify the NAD+ or NADH separately, except for in vitro studies where only one form is present [35]. SoNar has an intense fluorescence with a large dynamic range and rapid kinetics compared to other probes, making it most suitable for in vivo studies [35].

In addition, one genetically encoded sensor for detection of free NAD+ has been developed [41]. This sensor is based on the specific NAD+-binding domain modeled from bacterial DNA ligase that is fused with circularly permuted fluorescent protein cpVenus. This sensor is only minimally affected by pH in the range of 6.5–8.0; however, the temperature has a slight effect on the fluorescence intensity [41]. These genetically encoded indicators for NAD+ and NADH can be transiently or stably expressed in various types of cells and targeted to different subcellular compartments. Various techniques, such as imaging, flow cytometry, or fluorescence reading (e.g., microplate readers) can be used to monitor changes in the NAD+ and NADH redox state using these sensors [32–34].

In vivo imaging

31P and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) methods have been developed for the non-invasive measurement of NAD+ concentrations and NAD+/NADH ratio in animal and human brains in vivo [42, 43]. The 31P-NMR signal of the total NAD(H) pool has been observed since the early days of in vivo 31P-NMR, but now the availability of high/ultra high magnetic field strengths and spectral fitting routines can separate the NAD+ and NADH contributions to the observed NMR signals. These methods were used to study the NAD+/NADH ratios in brains of healthy, aging, and Parkinson’s disease populations [42, 43]. As mentioned above, SoNar was also shown to be suitable for in vivo studies and was used for fluorescent imaging of NAD+/NADH ratio in tumor xenografts in mice [35].

Modulators of NAD+/NADH ratio

To complement the studies measuring NAD+ and NADH, tools for manipulating these species are needed for mechanistic investigations of NAD+ or NADH-dependent metabolism. LbNOX is a recently developed genetically encoded tool based on the bacterial NADH oxidase (NOX) from Lactobacillus brevis [44]. NOX catalyzes a four-electron reduction of oxygen to water using reducing equivalents of NADH, and its natural function is protection of redox balance and defense against oxygen toxicity. In HeLa cells, both LbNOX and its mitochondria-targeted version mitoLbNOX decreased NADH levels in the cytosol as measured by SoNar. However, only mitoLbNOX impacted total cellular NADH measured by HPLC [44]. A limitation of these systems is the lack of substrate control: when expressed in cells these proteins oxidize NADH, and there is no possibility to control the level and duration of reaction by substrate. Consumption of O2 could lead to onset on hypoxia and broad perturbation of cellular signaling and metabolism. It is also not possible to reverse the reaction towards reduction of NAD+ with the LbNOX system as the reaction product is H2O.

NAD-Targeting Therapies to Enhance Radiation Response

Ratio of NQO1 vs CAT expression

High-level expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) has been linked to the progression of different human cancers, including lung, breast, liver, colon, pancreatic, thyroid, adrenal, ovary, colon, bladder, head and neck, and colorectal [45–49]. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patient tumor samples, significantly elevated mRNA expression of NQO1 was observed compared to lower catalase (CAT) expression [17, 50, 51]. Western analyses showed lowered CAT levels and higher NQO1 levels in NSCLC compared to normal lung tissue [50]. Over-expression of NQO1 was observed in advanced NSCLC and treatment-resistant NSCLC patient tumor samples [50]. Immunohistochemical staining and Western blot assays also showed elevated expression of NQO1 and lower catalase expression in head and neck cancer, breast cancer, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [45, 48, 49]. The inverse expression pattern of NQO1 and catalase presents an ideal therapeutic target by selectively killing cancer cells with high NQO1 expression levels.

Enhanced antitumor efficacy of NQO1-bioactivatable drugs with ionization radiation

β-Lapachone (β-lap, ARQ761 in clinical form) is an NQO1-bioactivated naphthoquinone chemotherapeutic that generates an unstable hydroquinone which spontaneously reacts with two oxygen molecules in a two-step futile cycle to regenerate the original compound [51]. This futile redox cycling oxidizes ~60 moles of NAD(P)H to create ~120 moles of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in ~2 mins, leading to the generation of permeable hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) that diffuses into the nucleus and causes massive oxidative base and single-strand breaks (SSB) [45]. β-Lapachone has exhibited tumor-selective cytotoxic effects and caspase-independent programmed necrosis in several NQO1+ cancer cells and solid tumors, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (MiaPaCa2), breast (TNBC: MDA-MB-231 NQO1+/−, Luminal: MCF-7), colon (HCT116), non-small cell lung (H596 and A549), prostate (LNCaP NQO1+ vs NQO1-), and head and neck cancers [45, 49–54]. PDA and NSCLC cells showed severe lethality and loss of NAD+/NADH after 2 hours of β-lapachone treatment (≥ 4 μM), resulting in PARP hyper-activation, DNA damage, and alterations in metabolic homeostasis [50–52]. Additionally, NQO1 knockout and stable NQO1 shRNA-knockdown PDA and NSCLC cells were highly resistant to β-lapachone toxicity [50, 51].

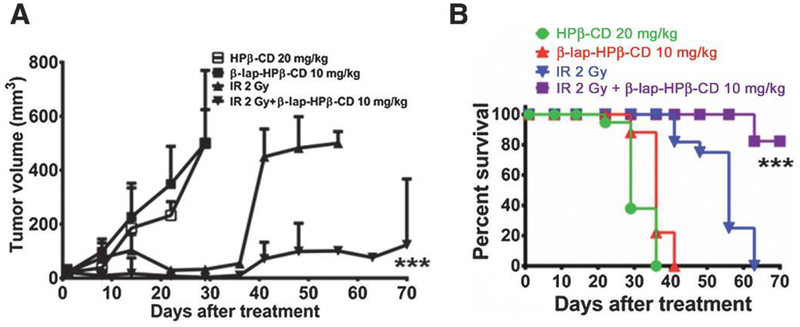

Sub-lethal doses of β-lapachone exploit NQO1 to release massive levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in synergism with ionizing radiation and increased programmed necrosis [55, 56]. HNC cells and tumors were shown to be sensitive to non-toxic doses of β-lapachone combined with IR. This combination significantly improved NQO1-dependent tumor cell lethality, increased ROS, DNA damage, γH2AX foci formation, NAD+ and ATP consumption, and μ-calpain–induced programmed cell death in HNC cells (FaDu, SqCC/Y1 and Detroit 562: NQO1+, UM-SCC-10A: NQO1-), two xenografts murine HNC models, as well as prostate cancer cells [49, 57] (Figure 2). Mice bearing 30 mm3 SqCC/Y1 HNC xenografts (high levels of NQO1 expression) were treated with 2 Gy IR every other day for five treatments (10 Gy total dose) [49]. β-Lapachone HPβ-CD 10 mg/kg was intravenously administered by tail vein injection immediately followed by 2 Gy IR treatment [49] This combination therapy resulted in significant DNA base damage (both single-stranded and double-stranded breaks) in HNC cells [49, 55, 57].

Figure 2.

Cooperative antitumor efficacy using a combination of β-lap and IR to treat HNC xenograft models. Mice bearing 30 mm3 SqCC/Y1 HNC xenografts with high levels of NQO1 expression were treated with 2 Gy every other day for five treatments (10 Gy total dose). β-lap-HPβ-CD 10 mg/kg was intravenously administered by tail-vein injection immediately following 2 Gy treatment. Vehicle alone (HPβ-CD) served as a control cohort (Materials and Methods). Results (means ± SE) are representative of repeated similar experiments (n=10 for each group). Student’s t-tests (*** p < 0.001) were performed comparing treated vs control groups. (A) Tumor volume measurements and (B) Kaplan-Meier overall survival over the indicated number of days is graphed for control (HPβ-CD), β-lap-HPβ-CD 10 mg/kg alone, 2 Gy alone and a combination of 2 Gy plus β-lap-HPβ-CD 10 mg/kg. Log-rank analyses were performed comparing survival curves using various IR + β-lap-HPβ-CD regimens (*** p < 0.001 for the combined treatment compared to each single treatment). Survival curves show equivalency between HPβ-CD and β-lap-HPβ-CD 10 mg/kg. Reprinted from [49].

PARP inhibitors for increasing radiation sensitivity

The rapid accumulation of DNA lesions from β-lapachone treatment leads to hyperactivation of PARP1 by overwhelming the cell’s DNA repair capacity, followed by rapid protein PARylation including PAR-PARP1, severe NAD+/ATP depletion, massive DNA lesions, and repair inhibition [58]. Combining PARP inhibitors with the highly tumor-specific DNA-damaging agent ß-lapachone results in synergy at nontoxic doses of both drugs in NQO1+ over-expressing non-small cell lung (NSCLC), pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) and breast cancers, including triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC) [50]. PARP inhibitors prevent auto-poly-ADP-ribosylation, preventing release from DNA and access of SSBs to DNA repair proteins. Unrepaired SSBs can lead to DSBs (collision of unrepaired SSB with replication fork in S-phase), enhancing the effect of radiation [22]. When using higher β-lapachone doses, including a PARP inhibitor prevents NAD+ loss and replenishes NAD(P)H levels for increased futile cycling and ROS generation.

NAMPT inhibitors for increasing radiation sensitivity

Increased expression of NAMPT was reported in colorectal, non-small cell lung (NSCL), prostate and pancreatic cancer [59–63]. NAMPT serves as an important source of reducing equivalents for redox balance within the cancer cell [60]. NAMPT inhibitors such as FK866 have been shown to decrease NAD+ levels and inhibit tumor growth [64]. Pre-treatment of NQO1+ cancer cells with FK866 reduced overall NAD+/NADH pool sizes prior to β-lapachone treatment, which led to an accelerated decrease in NAD+/NADH levels and shifts in lethality of β-lapachone to smaller doses of the drug [65]. Overall, treatment with FK866 attenuates the effects of β-lapachone without causing excess PAR formation due to lower NAD+ levels, and makes the NAMPT inhibitor tumor-selective. NAMPT knockdown sensitizes prostate and head and neck cancer cell lines to ROS induction from ionizing radiation [60, 66–68].

Modeling Approaches for Target Discovery in NAD+ Metabolism

Genome-scale metabolic modeling for target discovery

From genome-scale reconstructions of human metabolism, it is estimated that NAD+ and NADH are involved in over 600 different metabolic reactions, acting as both a redox cofactor as well as a metabolic substrate [69]. Whereas experimentally studying each of these reactions and their interconnections in the context of NAD+ metabolism would be infeasible, computational methods have been developed to efficiently study the human metabolic network on a genome scale. Flux balance analysis (FBA), one of the most common of these methods, is a metabolic modeling methodology that allows for the prediction of steady-state reaction fluxes throughout the metabolic network [70]. Context-specific FBA models can be developed to obtain flux predictions specific to individual cell lines or tumors, and custom objective functions can be used to analyze specific aspects of cellular metabolism of interest [71].

An FBA-based metabolic modeling pipeline that incorporates transcriptomic, kinetic, thermodynamic, and metabolite concentration data has previously been developed to make accurate predictions of NADPH production in radiation-sensitive (SCC-61) and radiation-resistant (rSCC-61) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cell lines [72]. The goal of this model development was to compare intrinsic metabolic differences between the matched HNSCC cell lines that may yield phenotypic differences in sensitivity to NQO1-dependent drugs such as β-lapachone. Using this modeling platform and an objective function of maximizing the reduction of NADP+ to NADPH, NADPH-production genes were discovered where knockdown causes distinct effects on total cellular NADPH production between SCC-61 and rSCC-61 cells. In addition, model predictions of NADPH production after simulated knockdown of 229 individual oxidoreductase genes matched well with experimental measurements of cell viability after 24 hours of β-lapachone exposure in siRNA-treated cell lines.

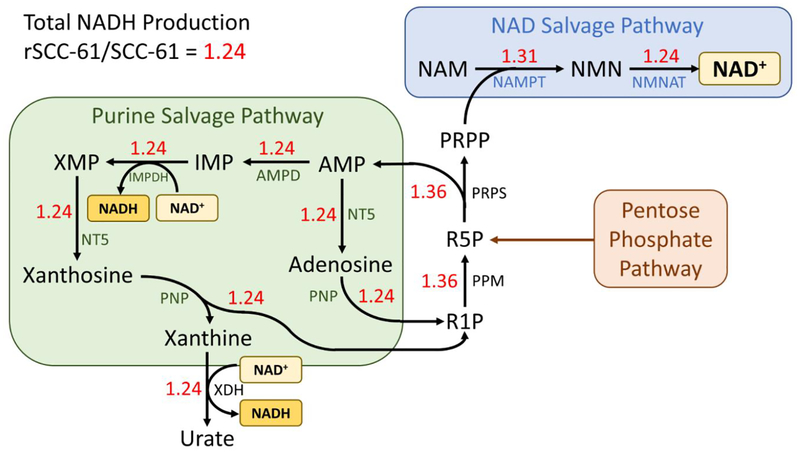

Modeling NADH metabolism in radiation-sensitive and -resistant HNSCC cell lines

FBA predictions of the most important genes and metabolic pathways towards NADH production are expected to yield valid targets for enhancing sensitivity to both radiation therapy and β-lapachone treatment. To this end, using an objective function of maximizing NADH production, parsimonious flux balance analysis (pFBA) was used to obtain a single representative flux vector in both SCC-61 and rSCC-61 cell lines that maximizes both the production of NAD+, as well as reduction of NAD+ to NADH.

The rSCC-61 model showed greater total NADH production than the SCC-61 model, with rSCC-61/SCC-61 = 1.24 (Figure 3). Both models displayed significant fluxes through the NAD+ salvage, purine salvage, and pentose phosphate pathways. The pentose phosphate pathway produces ribose 5-phosphate (R5P), which is converted into adenosine monophosphate (AMP) and phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate (PRPP) by phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthase (PRPS). PRPP is converted to NMN and NAD+ by NAMPT and NMNAT, respectively, in the NAD+ salvage pathway, supplying both cell lines with sufficient amounts of NAD+. AMP is converted to other purines and members of the purine salvage pathway, eventually being excreted as uric acid. Through this pathway, NAD+ produced from the NAD+ salvage pathway can be reduced to NADH by both IMP dehydrogenase and xanthine oxidase. Additionally, ribose 1-phosphate (R1P) produced from xanthosine can be re-converted into R5P, entering back into the cycle. Thus, the interconnection of the pentose phosphate pathway, NAD+ salvage pathway, and purine salvage pathway plays an important role in both NAD+ synthesis and reduction to NADH in both cell lines.

Figure 3. Parsimonious flux balance analysis results in SCC-61 and rSCC-61 cell lines.

Cytosolic NADH production was maximized to determine the most pertinent metabolic pathways and reactions towards both NAD+ production and reduction of NAD+ to NADH. Red numbers indicate the ratio of predicted flux values for each reaction between rSCC-61/SCC-61 cell lines. Abbreviations: AMP, adenosine monophosphate; AMPD, adenosine monophosphate deaminase; IMP, inosine monophosphate; IMPDH, inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase; NAM, nicotinamide; NAMPT, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; NMN, nicotinamide mononucleotide; NMNAT, nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase; NT5, 5’-nucleotidase; PNP, purine-nucleoside phosphorylase; PPM, phosphopentomutase; PRPP, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate; PRPS, phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthase; R1P, ribose 1-phosphate; R5P, ribose 5-phosphate; XDH, xanthine dehydrogenase/xanthine oxidase; XMP, xanthosine monophosphate.

To find selective targets of NAD+ and NADH production in radiation-resistant tumors, the metabolic reactions that had significantly greater flux in the radiation-resistant rSCC-61 cell line compared to the radiation-sensitive SCC-61 cell line were determined, such that the rSCC-61/SCC-61 flux ratio was larger than the ratio of total NADH production (rSCC-61/SCC-61 = 1.24). Both phosphopentomutase (PPM) and phosphoribosylpyrophosphate synthase (PRPS) had flux ratios of 1.36, and NAMPT had a flux ratio of 1.31. Previous studies have shown that inhibition of NAMPT decreases NAD+/NADH levels, increases levels of ROS, and sensitizes cancer cells to β-lapachone treatment [65, 66]. These computational and experimental findings suggest that combining NAMPT inhibitors with β-lapachone and/or ionizing radiation may be an effective treatment strategy for radiation-resistant tumors. Additionally, prior modeling and experimental findings showed that knockdown of NADPH-producing genes in the pentose phosphate pathway (including G6PD) causes greater sensitization towards β-lapachone in rSCC-61 cells than SCC-61 cells [72]. This corroborates with model predictions that reactions producing and consuming R5P may be valid targets for selectively suppressing NAD+ metabolism in radiation-resistant tumors.

Precision medicine approach towards targeting NAD+ metabolism

With the wealth of biological and clinical data becoming available, the precision medicine approach towards tailoring cancer therapies for individual patients is becoming more viable. This type of approach can help determine which therapies will best target NAD+ metabolism to increase radiation sensitivity in individual cancer patients. For example, PARP inhibitors are being selectively chosen for patients with homologous recombination (HR) deficiencies, including those with BRCA1/2 mutations [73, 74]. When cells are deficient in HR, they upregulate PARP1 alternative end-joining to compensate, making these tumors more sensitive to PARP inhibitors [75]. Additionally, by hindering PARP1’s auto-poly ADP-ribosylation activity, PARP inhibitors prevent PARP1’s release from DNA, limiting access of DNA repair proteins to SSBs. If these SSBs remain, collision of unrepaired SSBs with the replication fork in S-phase of the cell cycle results in the generation of double-stranded breaks (DSBs) [22]. In patients with BRCA1/2 mutations, the DSB repair pathways are impaired, and the combination of both SSBs and DSBs results in greater tumor cell death and radiation sensitization. Because NQO1 activity is the principal determinant of β-lapachone sensitivity, β-lapachone is being selectively chosen for patients with high expression levels of NQO1 [45].

Personalized genome-scale metabolic models of HNSCC patient tumors developed using transcriptomic data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) have recapitulated many of the differences in NADPH metabolism between radiation-sensitive and -resistant HNSCC cell lines [72]. These types of models can be used to discover viable therapeutic targets in individual patients, including enzymes and metabolic reactions where intervention would best disrupt the NAD+ metabolic network and increase radiation sensitivity. Additionally, agent-based modeling will ultimately help establish the important role that cellular metabolic heterogeneity plays in the collective cellular behaviors seen in tumor growth and migration, as well as the tumor response to chemotherapy and radiation treatment [76]. Combining computational modeling with state-of-the-art experimental approaches including novel biosensors and patient-derived organoids will undoubtedly improve our ability to target NAD+ metabolism to enhance radiation therapy responses in individual cancer patients.

Conclusion

By disrupting fundamental metabolic and signaling processes necessary for cancer cell survival, current NAD+-targeting therapies are showing tremendous promise in their ability to selectively enhance tumor sensitivity to radiation therapy. These therapies take advantage of our current understanding of the major influxes and effluxes from the cellular supply of NAD+, along with how these fluxes are disrupted in cancer and especially with the radiation-resistant phenotype. Novel experimental techniques for sensing and modulating NAD+/NADH, as well as computational systems biology methods of modeling NAD+ metabolism, will undoubtedly provide us with greater insights into these fundamental biological processes as well as novel targets for improving radiation response. As the availability and quality of multi-omic data derived from patient tumors increases, our ability to pinpoint specific disruptions in the NAD+ metabolic network and determine which therapies will best address these disruptions within individual patients will greatly improve. NAD+ metabolism remains a key aspect of oxidative metabolism as well as a promising target for enhancing radiation therapy responses.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to support for our studies through an NIH/NCI U01 CA215848 grant (PI: M. Kemp; Co-Is: Furdui, Boothman, Sumer).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Verdin E, NAD(+) in aging, metabolism, and neurodegeneration. Science, 2015. 350(6265): p. 1208–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garrido A and Djouder N, NAD(+) Deficits in Age-Related Diseases and Cancer. Trends Cancer, 2017. 3(8): p. 593–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy BE, et al. , NAD(+) salvage pathway in cancer metabolism and therapy. Pharmacol Res, 2016. 114: p. 274–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michels J, et al. , PARP and other prospective targets for poisoning cancer cell metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol, 2014. 92(1): p. 164–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gujar AD, et al. , An NAD+-dependent transcriptional program governs self-renewal and radiation resistance in glioblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2016. 113(51): p. E8247–e8256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao W, et al. , NAD(H) and NADP(H) Redox Couples and Cellular Energy Metabolism. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2018. 28(3): p. 251–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Houtkooper RH, et al. , The secret life of NAD+: an old metabolite controlling new metabolic signaling pathways. Endocr Rev, 2010. 31(2): p. 194–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Revollo JR, Grimm AA, and Imai S, The NAD biosynthesis pathway mediated by nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase regulates Sir2 activity in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem, 2004. 279(49): p. 50754–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sampath D, et al. , Inhibition of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) as a therapeutic strategy in cancer. Pharmacol Ther, 2015. 151: p. 16–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao Y, et al. , Dependence of tumor cell lines and patient-derived tumors on the NAD salvage pathway renders them sensitive to NAMPT inhibition with GNE-618. Neoplasia, 2013. 15(10): p. 1151–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ali YO, et al. , NMNATs, evolutionarily conserved neuronal maintenance factors. Trends Neurosci, 2013. 36(11): p. 632–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman MP and Freeman MR, Wallerian degeneration, wld(s), and nmnat. Annu Rev Neurosci, 2010. 33: p. 245–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schafer FQ and Buettner GR, Redox environment of the cell as viewed through the redox state of the glutathione disulfide/glutathione couple. Free Radic Biol Med, 2001. 30(11): p. 1191–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin SJ and Guarente L, Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, a metabolic regulator of transcription, longevity and disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol, 2003. 15(2): p. 241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim SB, et al. , Targeting of Nrf2 induces DNA damage signaling and protects colonic epithelial cells from ionizing radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012. 109(43): p. E2949–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nguyen T, Nioi P, and Pickett CB, The Nrf2-antioxidant response element signaling pathway and its activation by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem, 2009. 284(20): p. 13291–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegel D, Franklin WA, and Ross D, Immunohistochemical detection of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase in human lung and lung tumors. Clin Cancer Res, 1998. 4(9): p. 2065–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu KC, Cui JY, and Klaassen CD, Beneficial role of Nrf2 in regulating NADPH generation and consumption. Toxicol Sci, 2011. 123(2): p. 590–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rada P, et al. , WNT-3A regulates an Axin1/NRF2 complex that regulates antioxidant metabolism in hepatocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2015. 22(7): p. 555–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, et al. , Identification of polymorphic antioxidant response elements in the human genome. Hum Mol Genet, 2007. 16(10): p. 1188–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eustermann S, et al. , Structural Basis of Detection and Signaling of DNA Single-Strand Breaks by Human PARP-1. Mol Cell, 2015. 60(5): p. 742–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell C, et al. , Pre-clinical and clinical evaluation of PARP inhibitors as tumour-specific radiosensitisers. Cancer Treat Rev, 2010. 36(7): p. 566–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vazquez BN, Thackray JK, and Serrano L, Sirtuins and DNA damage repair: SIRT7 comes to play. Nucleus, 2017. 8(2): p. 107–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.North BJ and Verdin E, Sirtuins: Sir2-related NAD-dependent protein deacetylases. Genome Biol, 2004. 5(5): p. 224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alano CC, et al. , NAD+ depletion is necessary and sufficient for poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1-mediated neuronal death. J Neurosci, 2010. 30(8): p. 2967–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo X and Kraus WL, On PAR with PARP: cellular stress signaling through poly(ADP-ribose) and PARP-1. Genes Dev, 2012. 26(5): p. 417–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moroni F, Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 (PARP-1) and postischemic brain damage. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2008. 8(1): p. 96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie W, Xu A, and Yeung ES, Determination of NAD(+) and NADH in a single cell under hydrogen peroxide stress by capillary electrophoresis. Anal Chem, 2009. 81(3): p. 1280–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yoshino J and Imai S, Accurate measurement of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD(+)) with high-performance liquid chromatography. Methods Mol Biol, 2013. 1077: p. 203–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trammell SA and Brenner C, Targeted, LCMS-based Metabolomics for Quantitative Measurement of NAD(+) Metabolites. Comput Struct Biotechnol J, 2013. 4: p. e201301012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu W, et al. , Extraction and Quantitation of Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Redox Cofactors. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2018. 28(3): p. 167–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao Y and Yang Y, Real-time and high-throughput analysis of mitochondrial metabolic states in living cells using genetically encoded NAD(+)/NADH sensors. Free Radic Biol Med, 2016. 100: p. 43–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bilan DS and Belousov VV, New tools for redox biology: From imaging to manipulation. Free Radic Biol Med, 2017. 109: p. 167–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bilan DS and Belousov VV, Genetically encoded probes for NAD(+)/NADH monitoring. Free Radic Biol Med, 2016. 100: p. 32–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Y, et al. , In vivo monitoring of cellular energy metabolism using SoNar, a highly responsive sensor for NAD(+)/NADH redox state. Nat Protoc, 2016. 11(8): p. 1345–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blacker TS, et al. , Assessment of Cellular Redox State Using NAD(P)H Fluorescence Intensity and Lifetime. Bio Protoc, 2017. 7(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhao Y, et al. , Genetically encoded fluorescent sensors for intracellular NADH detection. Cell Metab, 2011. 14(4): p. 555–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hung YP, et al. , Imaging cytosolic NADH-NAD(+) redox state with a genetically encoded fluorescent biosensor. Cell Metab, 2011. 14(4): p. 545–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bilan DS, et al. , Genetically encoded fluorescent indicator for imaging NAD(+)/NADH ratio changes in different cellular compartments. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2014. 1840(3): p. 951–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhao Y, et al. , SoNar, a Highly Responsive NAD+/NADH Sensor, Allows High-Throughput Metabolic Screening of Anti-tumor Agents. Cell Metab, 2015. 21(5): p. 777–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cambronne XA, et al. , Biosensor reveals multiple sources for mitochondrial NAD(+). Science, 2016. 352(6292): p. 1474–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lu M, Zhu XH, and Chen W, In vivo (31) P MRS assessment of intracellular NAD metabolites and NAD(+)/NADH redox state in human brain at 4 T. NMR Biomed, 2016. 29(7): p. 1010–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Graaf RA, et al. , Detection of cerebral NAD(+) in humans at 7T. Magn Reson Med, 2017. 78(3): p. 828–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Titov DV, et al. , Complementation of mitochondrial electron transport chain by manipulation of the NAD+/NADH ratio. Science, 2016. 352(6282): p. 231–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pink JJ, et al. , NAD(P)H : quinone oxidoreductase activity is the principal determinant of beta-lapachone cytotoxicity. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2000. 275(8): p. 5416–5424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sieger D and Ross D, Immunodetection of NAD(P)H : quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) in human tissues. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2000. 29(3–4): p. 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chao C, et al. , NAD(P)H:: Quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) Pro187Ser polymorphism and the risk of lung, bladder, and colorectal cancers: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention, 2006. 15(5): p. 979–987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Awadallah NS, et al. , NQO1 expression in pancreatic cancer and its potential use as a biomarker. Applied Immunohistochemistry & Molecular Morphology, 2008. 16(1): p. 24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li LS, et al. , NQO1-Mediated Tumor-Selective Lethality and Radiosensitization for Head and Neck Cancer. Mol Cancer Ther, 2016. 15(7): p. 1757–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huang XM, et al. , Leveraging an NQO1 Bioactivatable Drug for Tumor-Selective Use of Poly(ADP-ribose) Polymerase Inhibitors. Cancer Cell, 2016. 30(6): p. 940–952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bey EA, et al. , An NQO1- and PARP-1-mediated cell death pathway induced in non-small-cell lung cancer cells by beta-lapachone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2007. 104(28): p. 11832–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Silvers MA, et al. , The NQO1 bioactivatable drug, beta-lapachone, alters the redox state of NQO1+ pancreatic cancer cells, causing perturbation in central carbon metabolism. J Biol Chem, 2017. 292(44): p. 18203–18216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chakrabarti G, et al. , Targeting glutamine metabolism sensitizes pancreatic cancer to PARP-driven metabolic catastrophe induced by beta-lapachone. Cancer & Metabolism, 2015. 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bey EA, et al. , Catalase abrogates beta-lapachone-induced PARP1 hyperactivation-directed programmed necrosis in NQO1-positive breast cancers. Mol Cancer Ther, 2013. 12(10): p. 2110–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boothman DA, Greer S, and Pardee AB, Potentiation of halogenated pyrimidine radiosensitizers in human carcinoma cells by beta-lapachone (3,4-dihydro-2,2-dimethyl-2H-naphtho[1,2-b]pyran-5,6-dione), a novel DNA repair inhibitor. Cancer Res, 1987. 47(20): p. 5361–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boothman DA, Trask DK, and Pardee AB, Inhibition of potentially lethal DNA damage repair in human tumor cells by beta-lapachone, an activator of topoisomerase I. Cancer Res, 1989. 49(3): p. 605–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dong Y, et al. , Prostate Cancer Radiosensitization through Poly(ADP-Ribose) Polymerase-1 Hyperactivation. Cancer Research, 2010. 70(20): p. 8088–8096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang X, et al. , An NQO1 substrate with potent antitumor activity that selectively kills by PARP1-induced programmed necrosis. Cancer Res, 2012. 72(12): p. 3038–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chini CC, et al. , Targeting of NAD metabolism in pancreatic cancer cells: potential novel therapy for pancreatic tumors. Clin Cancer Res, 2014. 20(1): p. 120–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang B, et al. , NAMPT overexpression in prostate cancer and its contribution to tumor cell survival and stress response. Oncogene, 2011. 30(8): p. 907–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Srivastava M, Khurana P, and Sugadev R, Lung cancer signature biomarkers: tissue specific semantic similarity based clustering of digital differential display (DDD) data. BMC Res Notes, 2012. 5: p. 617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hufton SE, et al. , A profile of differentially expressed genes in primary colorectal cancer using suppression subtractive hybridization. FEBS Lett, 1999. 463(1–2): p. 77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bi TQ, et al. , Overexpression of Nampt in gastric cancer and chemopotentiating effects of the Nampt inhibitor FK866 in combination with fluorouracil. Oncol Rep, 2011. 26(5): p. 1251–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zerp SF, et al. , NAD(+) depletion by APO866 in combination with radiation in a prostate cancer model, results from an in vitro and in vivo study. Radiother Oncol, 2014. 110(2): p. 348–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moore Z, et al. , NAMPT inhibition sensitizes pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells to tumor-selective, PAR-independent metabolic catastrophe and cell death induced by beta-lapachone. Cell Death Dis, 2015. 6: p. e1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cerna D, et al. , Inhibition of nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) activity by small molecule GMX1778 regulates reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated cytotoxicity in a p53- and nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase1 (NAPRT1)-dependent manner. J Biol Chem, 2012. 287(26): p. 22408–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kato H, et al. , Efficacy of combining GMX1777 with radiation therapy for human head and neck carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, 2010. 16(3): p. 898–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Okumura S, et al. , Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase: a potent therapeutic target in non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor-gene mutation. J Thorac Oncol, 2012. 7(1): p. 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brunk E, et al. , Recon3D enables a three-dimensional view of gene variation in human metabolism. Nat Biotechnol, 2018. 36(3): p. 272–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Orth JD, Thiele I, and Palsson BO, What is flux balance analysis? Nat Biotechnol, 2010. 28(3): p. 245–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Garcia Sanchez CE and Torres Saez RG, Comparison and analysis of objective functions in flux balance analysis. Biotechnol Prog, 2014. 30(5): p. 985–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lewis JE, et al. , Genome-Scale Modeling of NADPH-Driven beta-Lapachone Sensitization in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dziadkowiec KN, et al. , PARP inhibitors: review of mechanisms of action and BRCA1/2 mutation targeting. Prz Menopauzalny, 2016. 15(4): p. 215–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schoonen PM, et al. , Progression through mitosis promotes PARP inhibitor-induced cytotoxicity in homologous recombination-deficient cancer cells. Nat Commun, 2017. 8: p. 15981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kotter A, et al. , Inhibition of PARP1-dependent end-joining contributes to Olaparib-mediated radiosensitization in tumor cells. Mol Oncol, 2014. 8(8): p. 1616–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang Z, et al. , Simulating cancer growth with multiscale agent-based modeling. Semin Cancer Biol, 2015. 30: p. 70–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]