Abstract

Background:

Relapse, drug use, and treatment dropout are common challenges facing patients receiving methadone. Though effective, multiple barriers to face-to-face counseling exist. The Recovery Line (RL), an automated, self-management system based on Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, is a phone-based adjunctive treatment that provides low cost, consistent delivery and immediate therapeutic availability 24 hours a day.

Methods:

The current study was a 12-week randomized clinical efficacy trial of treatment-as-usual (TAU) only or RL+TAU for methadone treatment patients with continued illicit drug use (N=82). Previous small trial phases evaluated methods to increase participant engagement and use of the RL and were incorporated into the current RL version. Primary outcomes were days of self-reported illicit drug abstinence and urine screens negative for illicit drugs.

Results:

Days of self-reported illicit drug abstinence improved for patients in RL+TAU but not in TAU. Percent of urine screens negative for illicit drugs, coping skills efficacy, and retention in methadone treatment did not differ by condition. Patients in RL+TAU attended more substance use disorder treatment and self-help group sessions during treatment than those in TAU. RL system use was generally low and more system use was correlated with abstinence outcomes.

Conclusions:

Although the RL did not impact urine screen outcomes, it increases self-reported abstinence. Additional methods to increase patient engagement with automated, self-management systems for substance use disorder are needed.

Keywords: Computer-based Treatment, IVR, Methadone Treatment, Opioid-Related Disorders

1. Introduction

Automated, computer-based interventions have been shown in systematic reviews to be effective for managing a range of chronic medical (Rogers, Lemmen, Kramer, Mann, & Chopra, 2017; Tao & Or, 2013) and psychiatric disorders (Coull & Morris, 2011; Cuijpers et al., 2009; Kaltenthaler, Parry, Beverley, & Ferriter, 2008; Lewis, Pearce, & Bisson, 2012), including substance use disorders (Carey, Scott-Sheldon, Elliott, Bolles, & Carey, 2009; Hoch, Preuss, Ferri, & Simon, 2016; Moore, Fazzino, Garnet, Cutter, & Barry, 2011; Wood et al., 2014). Automated interventions have advantages over standard clinic or office-based treatment and telehealth or E-therapy treatments where a therapist or counselor provides treatment via phone or video conferences. These include low cost to patients, consistent intervention delivery (fidelity), and widespread availability, which may be particularly important for patients with limited treatment access, including those in rural or remote settings (Hall & Huber, 2000; Marsch, 2011; Moore et al., 2011). Recently, there has been increased interest in developing automated interventions for patients to use in their own environment on an as-needed basis. These automated self-management systems (ASMS) can be accessed by patients using mobile devices such as cellphones, tablets, and laptop computers and limit reliance on patient memory and cognitive abilities (Keoleian, Polcin, & Galloway, 2015; Oake, Jennings, van Walraven, & Forster, 2009). Through text, voice, and multimedia, ASMSs can potentially increase utilization and effectiveness of coping skills related to substance use at times of greater craving and other high-risk situations. Despite these potential advantages, ASMSs often depend on patient initiative and motivation which can limit engagement and use. Thus, it is important to differentiate ASMSs from other computer-based interventions for substance use disorder and evaluate them independently.

Most computer-based interventions demonstrated as efficacious for substance use disorder have used contingencies to maintain patient engagement and retention. These include fish bowl prizes based on computer-based session completion and urine-verified abstinence (A. N. Campbell et al., 2014) and provision of opioid agonist medication based on completion of computer-based sessions (Bickel, Marsch, Buchhalter, & Badger, 2008; Marsch et al., 2014). Other studies have provided these computer-based sessions in a specified room at a community substance use disorder treatment facility to which patients must travel (Carroll et al., 2014; Cochran et al., 2015).

In contrast, ASMSs that can be used from any location at any time have generally failed to demonstrate clear efficacy. Such studies include a relapse prevention program following inpatient substance use disorder treatment (Klein, 2014; Rose, Skelly, Badger, Ferraro, & Helzer, 2015), open enrollment web-based interventions (W. Campbell, Hester, Lenberg, & Delaney, 2016; Hester, Lenberg, Campbell, & Delaney, 2013; Nash & Vickerman, 2015; Tait & McKetin, 2015), and an ancillary intervention for continued drug use among methadone maintained patients (Moore et al., 2013). However, most of these studies have found that those who use the system more have better clinical outcomes (Hester et al., 2013; Klein, 2014; Moore et al., 2013; Rose, Skelly, Badger, Naylor, & Helzer, 2012; Tait & McKetin, 2015). For example, our initial randomized pilot clinical trial of the Recovery Line, a phone-based ASMS, found that days of system use was negatively correlated with self-reported substance use. Subsequent studies by our group developed and examined additional automated functions that could be added to the Recovery Line to increase patient engagement (Moore et al., 2012). Improving patient engagement and system use should thus provide a stronger test of efficacy for an ASMS in a comparative design. The current study was a randomized, clinical efficacy trial of the improved Recovery Line among methadone maintained patients with continued drug use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Patients were recruited from November, 2015 to August, 2016 at three clinics of a large, urban, New England opioid treatment organization through flyers, information tables, counselor referrals, word of mouth, treatment groups, and organizational research interest forms. Screening involved completion of a HIPPA authorization form and collection of contact and other information on basic demographics, methadone treatment status, recent illicit drug use, and cell-phone and internet use.

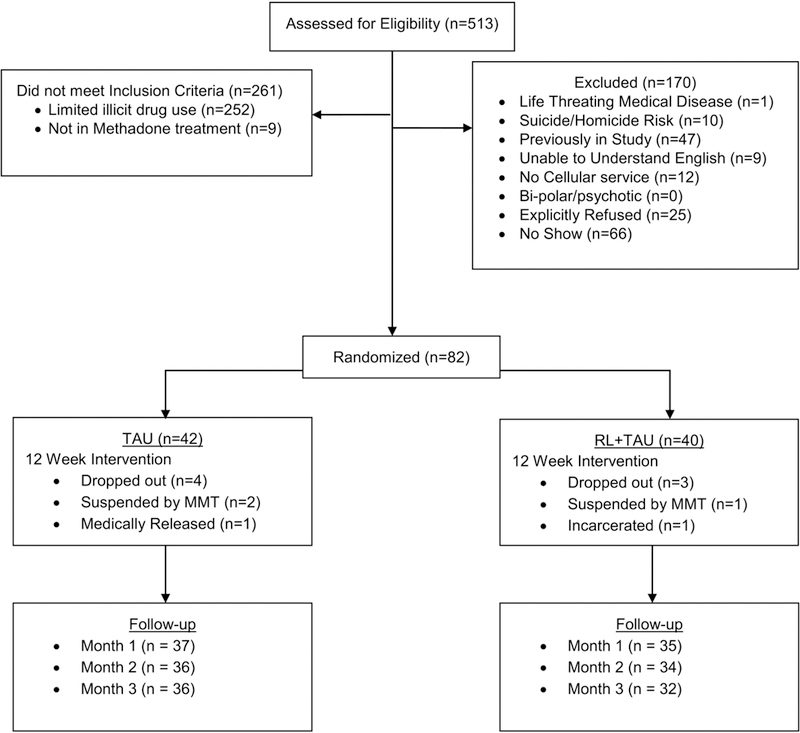

Inclusion criteria for the study were: 1) ≥18 years old, 2) currently receiving methadone treatment, 3) self-reported illicit drug use in the last 14 days or a positive urine screen for illicit drugs. Exclusion criteria were: 1) current suicide or homicide risk, 2) met criteria for current DSM-IV psychotic or bipolar disorder, 3) did not have access to a phone with text messaging, 4) unable to read or understand English, 5) unable to complete the study because of anticipated incarceration or move, or 6) medical complications that would interfere with participation. Figure 1 presents CONSORT data on screening, inclusion and exclusion, and assignment to condition.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram.

2.2. Design and Procedures

The study was a randomized clinical efficacy trial comparing methadone treatment and psychosocial treatment as usual (TAU) to the Recovery Line + TAU (RL+TAU) over a 12-week treatment period. The study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Yale University School of Medicine and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02124980).

After providing written consent, participants completed an approximately 90-minute intake process with a research assistant, including computer-assisted in-person assessments, urine screen collection, randomization, and orientation to assigned treatment arm. Participants’ treatment condition (TAU or RL+TAU) was determined using urn randomization with gender, cocaine positive urine screen, and number of days of illicit substance use (<10 or ≥10 days of use in the last 30 days) as blocking factors.

All participants received an orientation to the research components of the study and were scheduled for two regular weekly assessments (a primary weekly assessment and a secondary urine sample collection only). Monthly interviews using the same assessment procedures as the intake were conducted at 4, 8, and 12 weeks after intake. The 12-week follow-up also assessed patient satisfaction with the Recovery Line for those assigned to RL+TAU. Patients were paid $10 for completing the intake, $10 for each weekly assessment, $5 for the secondary urine collection, and $30 dollars for monthly appointments ($280 total).

2.3. Treatments

2.3.1. TAU.

We evaluated a treatment-as-usual comparison condition because the proposed system served as an enhancement of existing treatment services (Nunes et al., 2010). In addition to daily provision of methadone, the clinic offered a wide array of services, including open access therapeutic groups (with 25 or more typically available Monday-Friday) covering a range of topics such as introduction to methadone, weekend planning, overdose planning, and spirituality.

During the time of the study, patients were required to attend one group session per month and encouraged to attend others. Additional optional services included pregnancy counseling, family meetings, and psychiatric and medical care. Patients had access to all clinic services and procedures. Clinic decisions were not related to study participation. In cases when participants reported significant distress during assessments or at any other time during the study, research staff worked with patients and clinic staff to connect patients to appropriate services independent of assigned condition.

2.3.2. RL+TAU.

The Recovery Line (RL) is a password-protected, automated, computer-based, Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system providing Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) based modules (Moore et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2013; Rogers et al., 2017). The line was intended to be used by patients within their own environment to provide immediate assistance, training, and support for improved coping. Components include common substance use disorder CBT modules on self-monitoring, coping with urges and cravings, understanding patterns, managing stress, and motivation/goals (Carroll, 1998). Each component had learning and activities sections. The learning sections provided didactic explanations of the component and related concepts (e.g., triggers, craving, distraction, coping, etc.). The activities section provided direct guidance in successful use of the component (e.g., guided urge surfing, guided visualization, role-play examples of drug refusal, examples of distraction activities, etc.).

Patients assigned to the RL+TAU condition received 24-hour access, technical assistance, and a same-day 30-minute orientation to the system upon completion of intake. The orientation included step-by-step instructions of how to utilize the system, introduction to the concepts of CBT, a recommendation to call the system daily, a written manual and an identification card that included the patient’s ID, password and number to access the system. Positively-framed reminder text messages (see Table 1) were sent to the patients based on pre-identified call window established with the research assistants during orientation (Moore et al., 2017). Text messages were sent in unicode electronic format and were limited to 128 characters. Patients received one of 30 randomized text messages four hours after their call window if the patient did not contact the system within the last 24 hours. Moore et al. (Moore et al., 2017) demonstrated that the short-term latencies increased call frequency.

Table 1.

Daily positively-framed reminder text messages sent to patients in the Recovery Line condition.

| 1. | Calling the Recovery Line each day can help you stay on track towards a better life. |

| 2. | The more you use the Recovery Line, the more you understand what works best for you. |

| 3. | Calling the Recovery Line can help you remember how well you’re doing. |

| 4. | It’s much easier to stick to your program when you use the Recovery Line every day. |

| 5. | The Recovery Line can teach you tips for better health. |

| 6. | Some activities on the Recovery Line can help you feel better about yourself. |

| 7. | Imagine all the money you’ll save by staying on track with the Recovery Line. |

| 8. | Using the Recovery Line every day can help you with your goals. |

| 9. | Calling the Recovery Line can help when you feel stressed. |

| 10. | Recovery is easier when you have support. Call the Recovery Line. |

| 11. | By calling the Recovery Line you can learn a lot to help you stay on track. |

| 12. | Using the Recovery Line saves you the hassle of traveling for help or support. |

| 13. | The Recovery Line can help you remember your goals. |

| 14. | Using the Recovery Line every day helps you keep track of how you’re doing. |

| 15. | You have more time to enjoy life when you stay on track with the Recovery Line. |

| 16. | Using the Recovery Line helps you stay on track. |

| 17. | The Recovery Line can give help when you need it, day or night. |

| 18. | Using the Recovery Line can give you confidence in your recovery. |

| 19. | Doing Recovery Line activities can help you feel better physically. |

| 20. | The Recovery Line gives you ways to deal with stress. |

| 21. | You can use the Recovery line to improve your health. |

| 22. | The Recovery Line has tips to help you relax. |

| 23. | The Recovery Line is one call away. You can get help right now. |

| 24. | Calling the Recovery line daily can keep you motivated. |

| 25. | Using the Recovery line helps you understand your patterns so you can avoid trouble. |

| 26. | Daily use of the Recovery Line can strengthen your recovery skills. |

| 27. | The Recovery Line can be used 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. |

| 28. | Take a moment for yourself. Use the Recovery Line. |

| 29. | Having a bad day? Call the Recovery Line. |

| 30. | With the Recovery Line, you can set today’s goals for your recovery. |

2.4. Measures

Patient demographic and substance use disorder treatment history were collected at intake, including age, gender, ethnicity, duration of current MMT treatment, number of attempts to reduce/stop illicit drug use, and number of substance abuse treatment episodes within the last five years. Treatment process and other psychometric measures were administered over the course of the study. The primary outcomes were days per month of self-reported illicit drug abstinence (heroin, non-prescribed opioids, cocaine, non-prescribed benzodiazepines or other sedatives, amphetamines, marijuana, hallucinogens, or inhalants) and percent of urine screens negative for illicit drugs. Secondary outcome measures were retention in methadone treatment and coping skills efficacy.

Computer-assisted personal interviews were used to collect quantity and frequency of substance use, substance use related problems, substance use related coping skills, depression, and treatment satisfaction. Substance use, substance-related problems, coping skills, and depression were assessed at baseline, monthly during treatment, and at the end of treatment. The Addiction Severity Index -Lite (ASI-Lite; (Cacciola, Alterman, McLellan, Lin, & Lynch, 2007) is a shortened version of the Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1992), a semi-structured interview that assesses seven problem areas: medical, employment and support, drug use, alcohol use, legal, family/social, and psychiatric. The ASI Lite has good reliability and validity and produces information similar to that of the ASI (Cacciola et al., 2007). The Effectiveness of Coping Behaviors Inventory (ECBI; (Litman, Stapleton, Oppenheim, Peleg, & Jackson, 1984) is a 36 item self-report questionnaire that assesses the perceived effectiveness of a variety of behavioral and emotional coping behaviors to avoid relapse. The ECBI has been found to be responsive to treatment effects for alcohol use disorder (Litman et al., 1984; Rose et al., 2012). We have used the ECBI in the Recovery Line pilot trial with methadone maintained patients where it showed high inter-rater reliability (Cronbach’s alpha =.95) and correlated with cocaine use (Moore et al., 2013). The Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form BDI-SF; (Beck, Rial, & Rickels, 1974) is a 13 question 4-point Likert scale used to assess depression symptoms in patient populations (Furlanetto, Mendlowicz, & Romildo Bueno, 2005; Knight, 1984). A modified Treatment Services Review (TSR) was used to assess self-reported attendance at clinic-based individual and group-based substance abuse counseling, and self-help groups such as AA and NA.

Urine samples collected at baseline and twice each week during treatment were screened for opiates, methadone, oxycodone, THC, cocaine metabolite, and benzodiazepines using RediTest (Redwood Toxicology Laboratories, Santa Rosa, CA). Cut off values established by the manufacturer were >200 ng/ml for opiates and benzodiazepines, >300 ng/ml for methadone and cocaine, >100 ng/ml oxycodone, and >50 ng/ml for THC. All patients (N= 82) tested positive for methadone at intake. MMT adherence, retention, and dropout were extracted from clinic administrative data.

For those assigned to RL+TAU, satisfaction with the RL was examined at the 12-week follow-up with an assessment used in our prior studies (Moore et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2013). Ease of use, interest, and perceived efficacy were assessed using 5-point Likert scales. The IVR system (Voxeo Inc, Orlando, FL) recorded information on patient system use (i.e., call initiation and termination time, response to specific items, and modules accessed), which were then used to compute summary measures of patient engagement, and days and total minutes of Recovery Line use. Finally, adverse events were recorded and graded for severity and relation to study participation.

2.5. Sample Size Calculation and Data Analysis

The target sample size was 100 patients (50 in each assigned condition). Based on variability estimates from our prior work with this population, the target sample size was chosen to provide >80% power (α= .05) to detect a medium effect size (d = .57) on the primary outcome of the percent of urine screens negative for illicit drugs and a small effect size (f = .10) for a repeated measures variable of days of self-reported illicit drug abstinence.

Missing urine screens were coded as positive for illicit drug use. For demographic data, univariate comparisons were conducted using chi-square for categorical data, and student t-tests for continuous and interval data sets, with adjustment for unequal variances. General linear models (GLM) with robust variance estimation and autoregressive (AR1) working correlation structure with intercept were used for the outcome of days of self-reported illicit drug abstinence to evaluate Time (Intake, Month 1, 2, and 3) x Condition (RL+TAU and TAU; Brown et al., 2008; West, 2009). GLM was also used to evaluate the number of substance abuse treatment or group self-help sessions attended each month. Student t-test was used to compare RL+TAU to TAU for the outcome of percent of urine screens negative for illicit drugs.

Follow-up analyses examined the relationship between measures of system engagement and the primary outcomes. Due to the skewed distribution of number of calls and total amount of call time, correlations of system use with primary outcomes were evaluated with negative binomial distributions. Statistics were computed in IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Measures.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of methadone treatment patients assigned to the Recovery Line plus treatment-as-usual or to treatment-as-usual only.

| Characteristic | RL+TAU n = 40 |

TAU n = 42 |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean, (SD) | 43.6 (10.3) | 41.2 (11.4) |

| Male, % (n) | 60% (24) | 60% (25) |

| Race, % (n) | ||

| Black | 20% (8) | 19% (8) |

| White | 65% (26) | 69% (29) |

| Other | 15% (5) | 12% (5) |

| Employed (part or full), % (n) | 37% (11) | 56% (23) |

| Education beyond HS, % (n) | 26%% (10) | 42% (17) |

| Monthly income, $, mean (SD) | 881 (684) | 1062 (848) |

| Never married, % (n) | 40% (15) | 61% (25) |

| Opioid dependence, years, mean (SD) | 14.0 (8.5) | 15.9 (11.8) |

| Prescription Drug Use, % (n) | 0% (0) | 12% (5) |

| History intravenous drug use, (n) | 45% (18) | 54% (23) |

| Days of opioid use, mean (SD) | 8.9 (9.9) | 9.4 (9.6) |

| Days of cocaine use, mean (SD) | 9.8 (10.9) | 6.3 (8.7) |

| Months of current MMT, mean (SD) | 37.0 (54.8) | 21.0 (30.1) |

| Number of prior drug treatments, mean (SD) | 6.8 (5.8) | 4.7 (4.6) |

| Number of prior MMT treatments, mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.3) | 2.5(2.6) |

| BDI-SF, mean (SD) | 13.9 (7.6) | 10.1 (6.4) |

Patients in RL+TAU had significant higher BDI-SF scores and were less likely to primarily use prescription opioids.

3.2. Outcome Measures.

3.2.1. Self-Reported Abstinence.

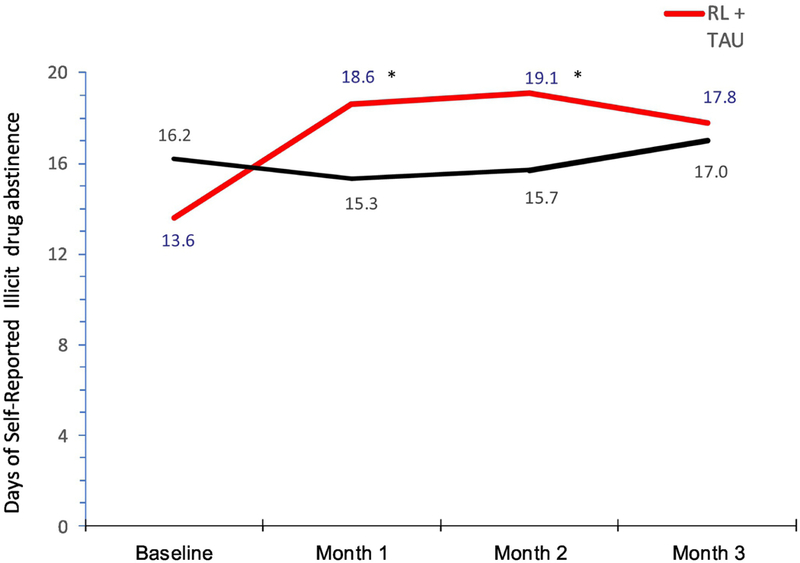

For the GLM examining days of self-reported illicit drug abstinence there was a significant interaction of treatment condition over time, F(3, 202.47) = 2.67, p = .049. Follow-up univariate tests indicated that the RL+TAU differed significantly over the four time-points, F(3, 201.47) = 3.41, p = .02, while the TAU condition did not, F(3, 200.25) = 0.41, p = .75. As can be seen in Figure 2, for the RL+TAU condition, days of abstinence were higher than baseline at Month 1 (p = .003, d = .44) and 2 (p = .03, d = .39), but not at Month 3 (p = .07, d = .34).

Figure 2.

Monthly Days of Self-Reported Illicit Drug Abstinence by Assigned Condition.

3.2.2. Urinalysis Data.

The percent of urine screens negative for illicit drugs was low (M = 16.7, SD = 24.0) and did not differ by assigned condition, t(80) = 0.02, p = .98 (RL+TAU; M = 16.7, SD = 25.6: TAU: M = 16.8, SD = 23.0). Evaluation of urinalysis data examining alternative assumptions of the urine screen results, including missing left as missing, imputation of last value carried forward, and use of general estimating equations showed the same pattern of null findings.

3.2.3. MMT Retention and Adherence.

Retention in methadone treatment was high (94%, n =77) and did not differ by assigned condition, X2(1) = 0.27, p = .60. We computed the percent of days of methadone medication adherence based on administrative data (including approved take home doses). The comparison between assigned condition approached significance, t (63.4) = 1.90, p = .06, such that patients in TAU (M = 93.0, SD = 11.9) had marginally higher adherence than those assigned to RL+TAU (M = 86.1, SD = 19.7). Finally, the number of substance use disorder treatment and self-help group sessions reported during the 12-week treatment phase was greater for patients in the RL+ TAU (M = 9.7, SD = 17.0) than those assigned to TAU (M = 5.1, SD = 8.8), F(1, 59.1) = 4.14, p = .047.

3.2.4. Coping Skills.

ECBI scores did not differ by treatment condition (p = .19), or over time (p = .70), nor was the interaction significant, F (3, 205.68) = 1.36, p = .26.

3.3. Recovery Line Measures

3.3.1. System Use.

For participants in the RL+TAU condition measures of system use were generally low, with a mean of 10.6 calls (SD = 16.1) and 59.1 total minutes of call time (SD = 85.6). The distributions were positively skewed; most patients (75%, n = 31) made fewer than 10 calls for less than 30 total minutes of call time (62%, n = 25). Similarly, few patients called beyond the first month: only 15 (24%) called one or more times in Month 2, and 12 (19%) called in Month 3.

Both measures of system use were correlated with the primary outcomes. Number of calls was significantly correlated with days of self-reported illicit drug abstinence (r = .25, p =.01) and percent of illicit drug negative urine screens (r = .42, p = .007). Total call minutes was significantly correlated with days of self-reported illicit drug abstinence (r = .20, p =.04) and percent of illicit drug negative urine screens (r = .54, p < .001).

3.3.2. Ratings of Acceptability, Interest, and Perceived Efficacy.

Ratings of interest, perceived efficacy, and ease of use at the end of the study were all high (M = 4.2, SD = 1.1, M= 4.3, SD = 0.9, and M = 4.9, SD = 1.2, respectively).

3.4. Adverse Events

There were only 12 unanticipated adverse events (7 for RL+TAU and 5 for TAU). One participant in TAU was removed from the study due to medical issues. None of the events were related to the intervention or study procedures.

4. Discussion

The findings from the current randomized clinical trial suggested that the Recovery Line is a promising ancillary intervention for patients receiving methadone who have ongoing drug use. Although findings did not show differences between conditions on the percent of negative urine screens for illicit drugs, there was a significant increase in the number of days of self-reported drug abstinence for the Recovery Line with TAU condition but not for TAU alone. There was also some evidence that patients assigned to RL+TAU were more engaged in treatment at their respective clinics. Patients in the intervention condition attended more self-help group sessions during the 12-week treatment phase than those in TAU only. In contrast, although retention did not differ across conditions, patients in TAU only had marginally better methadone adherence. Overall the findings are consistent with the broad range of studies that have shown computer-based interventions can have positive effects during treatment of substance use disorder (Marsch, 2011; Moore et al., 2011; Rogers et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2014). However, interventions focused on patient self-management and patient initiation and engagement have led to smaller or non-significant improvement (W. Campbell et al., 2016; Hester et al., 2013; Klein, 2014; Nash & Vickerman, 2015; Rose et al., 2015; Tait & McKetin, 2015). The current findings represent the first study to show significant benefit of an ASMS among patients in opioid agonist treatment.

A significant concern of the study was the limited use of the Recovery Line, somewhat less than the prior studies using the system {Moore, 2017 #44;Moore, 2013 #21}. Only 25% percent of patients used the recovery line 10 or more times. However, those that used the Recovery Line more showed greater improvement, in that the correlation of calls with days of drug abstinence was .25, and .42 with percent of urine screen abstinence. This finding is similar to other studies that have evaluated the use of self-management systems for substance abuse (Coull & Morris, 2011; Hester & Delaney, 1997; Hoch et al., 2016; Klein, 2014; Nash & Vickerman, 2015; Tao & Or, 2013). The Recovery Line was designed for this population, developed with on-going clinician and patient feedback, and focused on straightforward presentation of CBT-based concepts using plain language{Moore, 2013 #21}. However, although not mentioned in the qualitative interviews or prior qualitative development work, it is possible that some patients were intimidated by the system or the CBT-based content and did not use Recovery Line for this reason. An unexpected outcome that we unfortunately did not formally measure, was that a number of patients in the Recovery Line condition requested ongoing access at the end of the intervention and continued to call the system after then end of the study, suggesting that they continued to find the system valuable. Thus, methods designed to increase patient use may lead to improved outcomes. The low system use suggests that the current study’s reminder messages that occurred four-hours after their call window if they did not call, did not produce consistent system engagement in this population, which may have been in part due to the high cell phone turnover in this population. However, other methods should be explored, including use of positive or negative contingencies on system use, increased system initiation (i.e., Ecological Momentary Interventions; (Heron & Smyth, 2010; Myin-Germeys, Klippel, Steinhart, & Reininghaus, 2016), or modification of the system structure to be more interesting and engaging (i.e., “gamification”; (Anderson & Rainie, 2012; Fiellin, Hieftje, & Duncan, 2014; King, Greaves, Exeter, & Darzi, 2013; McCallum, 2012).

Despite the limited use of the Recovery Line, there was a group difference between the conditions, suggesting that the ability to access the system, that is, the patient knowing that the system is a resource that they could access if needed, may provide benefit. Some of the informal qualitative interviews that we conducted at the end of this study and other studies of the Recovery Line (Moore et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2013), are consistent with this hypothesis. Several patients noted that they had thought of calling the Recovery Line on a number of occasions, and although they chose not to, the fact that the system was available when needed helped them make the choice to abstain. Alternatively, the increase in drug abstinence may have been due to patients in RL+TAU attending more group sessions within their methadone treatment clinic or a combination of these factors.

A concern of the study was that gains

There were some limitations of the study. First, the study was conducted in a single treatment organization across clinics and the results may not generalize to other organizations. Second, although we did control for several important factors in the randomization procedures, the groups did differ on some baseline factors. Specifically, patients assigned to the Recovery Line had higher depression scores and were less likely to be primarily prescription opioid users. However, these factors have been associated with poorer opioid agonist treatment outcomes (Moore et al., 2007; Teesson et al., 2008), suggesting that the current findings may be an underestimate of the effect size. Third, although there was a significant increase in the number of days of self-reported illicit drug abstinence, the outcome of percent of urine screens negative for illicit drugs did not show any group differences. Of note, there were high levels of illicit drug use for all study patients throughout the study. For this population with high frequency of illicit drug use, urine screens may be insensitive to decreases in quantity and frequency of drug use. However, these changes can be meaningful in reducing important risks such as injection, overdose, and death, and are consistent with public health approaches (Madden et al., 2018; Wiessing et al., 2017). Such increases may also be important in the process of patients moving to higher levels of abstinence and achieving remission from substance use disorder (Carroll, 1998; McHugh, Hearon, & Otto, 2010). Fourth, the outcomes that showed statistically significant differences were based on self-report and thus may have been biased. However, previous research supports the validity of these measures (Denis et al., 2012; Hjorthøj, Hjorthøj, & Nordentoft, 2012). The research assistants all received substantial and on-going training in the collection valid self-reports, and the high frequency of reported substance use suggests that there was limited social demand to report abstinence. The study’s qualitative interviews were also consistent with the overall findings in which patients reported using the Recovery Line to reduce substance use.

Although the current results are promising, there are still questions as to whether an automated self-management system should be implemented as regular practice for methadone maintained patients with continued substance use. First, the intervention was developed and provided in the context of a research study, and although the cost of initial development of an IVR comprises the majority of the system’s overall budget, there are continued maintenance and modification fees to consider. The current study did not examine the cost-benefit or cost-effectiveness of patient improvements in relationship to the RL maintenance costs. Second, some patients engaged with the system extensively, while others did not. Evaluating predictors of patient engagement may provide insight into which patients benefit most, and how interventions may be tailored for less engaged patients. Finally, although we chose IVR in order to have a system available to a broad population of patients, this technology is becoming outdated, and adaptation to other technology platforms, or multiple platforms in which patients could access the system through different mechanisms should be considered.

Highlights.

The Recovery Line led to greater self-reported days of illicit drug abstinence for the first two months.

The Recovery Line did not have an impact on the proportion of urine screens negative for illicit drugs.

The Recovery Line led to greater involvement in clinic substance abuse treatment and self-help groups.

Use of the Recovery Line was low suggesting that additional methods to increase patient engagement with automated systems are needed.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse Grants R01 DA034678 & R01 DA034678-S1 and through the State of Connecticut, Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services support of the Connecticut Mental Health Center (B.M.). Portions of this research were presented in part at the 80th annual scientific meeting of College on Problems of Drug Dependence, Montreal, Canada and the 56th Annual Meeting of the New England Psychology Association (NEPA), Worcester, MA. We wish to thank Sydney Reichin, Justin Jones, Ryan Sullivan, and Natalia Zenoni for their integral assistance in conducting the study, as well as all staff at the APT Foundation for their support and dedication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson J, & Rainie L (2012). Gamification and the Internet: Experts Expect Game Layers to Expand in the Future, with Positive and Negative Results. Games Health J, 1(4), 299–302. doi: 10.1089/g4h.2012.0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rial WY, & Rickels K (1974). Short form of Depression Inventory: Cross-validation. Psychol Rep, 34, 1184–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA, Buchhalter AR, & Badger GJ (2008). Computerized behavior therapy for opioid-dependent outpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol, 16(2), 132–143. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.2.132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CH, Wang W, Kellam SG, Muthen BO, Petras H, Toyinbo P, … Methodology G (2008). Methods for testing theory and evaluating impact in randomized field trials: intent-to-treat analyses for integrating the perspectives of person, place, and time. Drug Alcohol Depend, 95 Suppl 1, S74–S104. PMC2560173. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Lin YT, & Lynch KG (2007). Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of a “Lite” version of the Addiction Severity Index. Drug Alcohol Depend, 87(2–3), 297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AN, Nunes EV, Matthews AG, Stitzer M, Miele GM, Polsky D, … Ghitza UE (2014). Internet-delivered treatment for substance abuse: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry, 171(6), 683–690. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell W, Hester RK, Lenberg KL, & Delaney HD (2016). Overcoming Addictions, a Web-Based Application, and SMART Recovery, an Online and In-Person Mutual Help Group for Problem Drinkers, Part 2: Six-Month Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Trial and Qualitative Feedback From Participants. J Med Internet Res, 18(10), e262. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Elliott JC, Bolles JR, & Carey MP (2009). Computer delivered interventions to reduce college student drinking: A meta-analysis. Addiction, 104, 1807–1819. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02691.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM (1998). A cognitive-behavioral approach: Treating cocaine addiction Rockville, MD: NIDA. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Kiluk BD, Nich C, Gordon MA, Portnoy GA, Marino DR, & Ball SA (2014). Computer-assisted delivery of cognitive-behavioral therapy: efficacy and durability of CBT4CBT among cocaine-dependent individuals maintained on methadone. Am J Psychiatry, 171(4), 436–444. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13070987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran G, Stitzer M, Campbell AN, Hu MC, Vandrey R, & Nunes EV (2015). Web-based treatment for substance use disorders: differential effects by primary substance. Addict Behav, 45, 191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull G, & Morris PG (2011). The clinical effectiveness of CBT-based guided self-help interventions for anxiety and depressive disorders: a systematic review. Psychol Med, 41(11), 2239–2252. doi: 10.1017/s0033291711000900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Marks IM, van Straten A, Cavanagh K, Gega L, & Andersson G (2009). Computeraided psychotherapy for anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Cogn Behav Ther 38(2), 66–82. doi: 10.1080/16506070802694776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis C, Fatséas M, Beltran V, Bonnet C, Picard S, Combourieu I, … Auriacombe M (2012). Validity of the Self-Reported Drug Use Section of the Addiction Severity Index and Associated Factors Used under Naturalistic Conditions. Subst Use Misuse, 47(4), 356–363. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.640732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiellin LE, Hieftje KD, & Duncan LR (2014). Videogames, here for good. Pediatrics, 134(5), 849–851. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furlanetto LM, Mendlowicz MV, & Romildo Bueno J (2005). The validity of the Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form as a screening and diagnostic instrument for moderate and severe depression in medical inpatients. J Affect Disord, 86(1), 87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA, & Huber DL (2000). Telephone management in substance abuse treatment. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health, 6, 401–407. doi: 10.1089/15305620050503870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron KE, & Smyth JM (2010). Ecological momentary interventions: incorporating mobile technology into psychosocial and health behaviour treatments. Br J Health Psychol, 15(Pt 1), 1–39. doi: 10.1348/135910709X466063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, & Delaney HD (1997). Behavioral Self-Control Program for Windows: results of a controlled clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol, 65(4), 686–693. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.65.4.686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Lenberg KL, Campbell W, & Delaney HD (2013). Overcoming Addictions, a Webbased application, and SMART Recovery, an online and in-person mutual help group for problem drinkers, part 1: three-month outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res, 15(7), e134. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorthøj CR, Hjorthøj AR, & Nordentoft M (2012). Validity of Timeline Follow-Back for selfreported use of cannabis and other illicit substances — Systematic review and meta-analysis. Addict Behav, 37(3), 225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoch E, Preuss UW, Ferri M, & Simon R (2016). Digital Interventions for Problematic Cannabis Users in Non-Clinical Settings: Findings from a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur Addict Res, 22(5), 233–242. doi: 10.1159/000445716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenthaler E, Parry G, Beverley C, & Ferriter M (2008). Computerised cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry, 193(3), 181–184. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keoleian V, Polcin D, & Galloway GP (2015). Text Messaging for Addiction: A Review. J Psychoactive Drugs, 47(2), 158–176. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2015.1009200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King D, Greaves F, Exeter C, & Darzi A (2013). ‘Gamification’: influencing health behaviours with games. J R Soc Med, 106(3), 76–78. doi: 10.1177/0141076813480996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein AA (2014). Computerized recovery support for substance use disorders: predictors of posttreatment usage. Telemed J E Health, 20(5), 454–459. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RG (1984). Some general population norms for the short form Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol, 40(3), 751–753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Pearce J, & Bisson JI (2012). Efficacy, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of self-help interventions for anxiety disorders: systematic review. Br J Psychiatry, 200(1), 15–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.084756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litman GK, Stapleton J, Oppenheim AN, Peleg M, & Jackson P (1984). The Relationship Between Coping Behaviours, their Effectiveness and Alcoholism Relapse and Survival. Addiction, 79(4), 283–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1984.tb03869.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden LM, Farnum SO, Eggert KF, Quanbeck AR, Freeman RM, Ball SA, … Barry DT (2018). An investigation of an open-access model for scaling up methadone maintenance treatment. Addiction doi: 10.1111/add.14198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA (2011). Technology-based interventions targeting substance use disorders and related issues: an editorial. Subst Use Misuse, 46(1), 1–3. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch LA, Guarino H, Acosta M, Aponte-Melendez Y, Cleland C, Grabinski M, … Edwards J (2014). Web-based behavioral treatment for substance use disorders as a partial replacement of standard methadone maintenance treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat, 46(1), 43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum S (2012). Gamification and serious games for personalized health. Stud Health Technol Inform, 177, 85–96. doi: 10.3233/978-1-61499-069-7-85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Hearon BA, & Otto MW (2010). Cognitive behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am, 33(3), 511–525. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, … Argeriou M (1992). The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat, 9(3), 199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, O’Connor P G, Cutter CJ, Schottenfeld RS, & Fiellin DA (2012). Counseling and directly observed medication for primary care buprenorphine maintenance: a pilot study. J Addict Med, 6(3), 205–211. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182596492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Buono FD, Printz DMB, Lloyd DP, Fiellin DA, Cutter CJ, … Barry DT (2017). Customized recommendations and reminder text messages for automated, computer-based treatment during methadone. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol, 25(6), 485–495. doi: 10.1037/pha0000149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Fazzino T, Barry DT, Fiellin DA, Cutter CJ, Schottenfeld RS, & Ball SA (2013). The Recovery Line: A pilot trial of automated, telephone-based treatment for continued drug use in methadone maintenance. J Subst Abuse Treat, 45(1), 63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Fazzino T, Garnet B, Cutter CJ, & Barry DT (2011). Computer-based interventions for drug use disorders: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat, 40(3), 215–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore BA, Fiellin DA, Barry DT, Sullivan LE, Chawarski MC, O’Connor PG, & Schottenfeld RS (2007). Primary care office-based buprenorphine treatment: comparison of heroin and prescription opioid dependent patients. J Gen Intern Med, 22(4), 527–530. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0129-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Klippel A, Steinhart H, & Reininghaus U (2016). Ecological momentary interventions in psychiatry. Curr Opin Psychiatry, 29(4), 258–263. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash CM, & Vickerman KA (2015). Utilization of a Web-based vs integrated phone/Web cessation program among 140,000 tobacco users: an evaluation across 10 free state quitlines. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(2), e36. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes EV, Ball S, Booth R, Brigham G, Calsyn DA, Carroll K, … Woody G (2010). Multisite effectiveness trials of treatments for substance abuse and co-occurring problems: have we chosen the best designs? J Subst Abuse Treat, 38 Suppl 1, S97–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.01.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oake N, Jennings A, van Walraven C, & Forster AJ (2009). Interactive voice response systems for improving delivery of ambulatory care. Am J Manag Care, 15(6), 383–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MA, Lemmen K, Kramer R, Mann J, & Chopra V (2017). Internet-Delivered Health Interventions That Work: Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses and Evaluation of Website Availability. J Med Internet Res, 19(3), e90. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose GL, Skelly JM, Badger GJ, Ferraro TA, & Helzer JE (2015). Efficacy of automated telephone continuing care following outpatient therapy for alcohol dependence. Addict Behav, 41, 223–231. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose GL, Skelly JM, Badger GJ, Naylor MR, & Helzer JE (2012). Interactive voice response for relapse prevention following cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol use disorders: a pilot study. Psychol Serv, 9(2), 174–184. doi: 10.1037/a0027606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait RJ, & McKetin R (2015). Six-month outcomes of a Web-based intervention for users of amphetamine-type stimulants: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res, 17(4), e105. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao D, & Or CK (2013). Effects of self-management health information technology on glycaemic control for patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Telemed Telecare doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teesson M, Mills K, Ross J, Darke S, Williamson A, & Havard A (2008). The impact of treatment on 3 years’ outcome for heroin dependence: findings from the Australian Treatment Outcome Study (ATOS). Addiction, 103(1), 80–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02029.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West BT (2009). Analyzing longitudinal data with the linear mixed models procedure in SPSS. Eval Health Prof, 32(3), 207–228. doi: 10.1177/0163278709338554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiessing L, Ferri M, Belackova V, Carrieri P, Friedman SR, Folch C, … Griffiths P (2017). Monitoring quality and coverage of harm reduction services for people who use drugs: a consensus study. Harm Reduct J, 14(1), 19. doi: 10.1186/s12954-017-0141-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood SK, Eckley L, Hughes K, Hardcastle KA, Bellis MA, Schrooten J, … Voorham L (2014). Computer-based programmes for the prevention and management of illicit recreational drug use: a systematic review. Addict Behav, 39(1), 30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]