Structured Abstract

Purpose of Review:

Central pulse pressure, a marker of vascular stiffness, is a novel indicator of risk for perioperative morbidity including ischemic stroke. Appreciation for the mechanism by which vascular stiffness leads to organ dysfunction along with understanding its clinical detection may lead to improved patient management.

Recent Findings:

Vascular stiffness is associated with increased mortality and neurologic, cardiac and renal injury in non-surgical and surgical patients. Left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction along with microcirculatory changes in the low vascular resistance, high blood flow cerebral and renal vasculature are seen in patients with vascular stiffness. Pulse wave velocity and the augmentation index have higher sensitivity for detecting of vascular stiffness than peripheral pulse pressure as the hemodynamic consequences of vascular stiffness are secondary to alterations in the central vasculature. Vascular stiffness alters cerebral autoregulation resulting in a high likelihood of having a lower limit of autoregulation > 65 mmHg during surgery. Vascular stiffness may predispose to cerebral hypoperfusion increasing vulnerability to ischemic stroke, postoperative delirium, and acute kidney injury.

Summary:

Vascular stiffness leads to alterations in cerebral, cardiac, and renal hemodynamics increasing the risk of perioperative ischemic stroke and neurologic, cardiac and renal dysfunction.

Keywords: Vascular stiffness, pulse pressure hypertension, cerebral blood flow autoregulation, perioperative stroke

Introduction

The proportion of US citizens older than 65 years is expected to increase to 20% of the population by the year 2030.[1] The number that are ≥85 years of age will likely increase from 5.5 million in 2010 to 19 million by 2050. Many of these patients will require either elective or emergent surgery. A concern is that > 40% of elderly surgical patients will experience a costly complication implying that as the surgical population ages, the number of postoperative complications will rise.[2] Perioperative neurological complications (ie, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or delayed neurocognitive recovery), are a particular concern given their negative impact on patient short- and long-term outcomes especially after cardiac surgery.[3] Distinguishing age per se as a risk factor for perioperative stroke versus patient co-morbidities is difficult. It is increasingly realized that pre-existing vascular disease manifest as heightened vascular stiffness can better differentiate risk for stroke and mortality than chronological age in the general population as well as for patients undergoing cardiac surgery.[4–7] Clinically, vascular stiffness is manifest as systolic hypertension and high pulse pressure. In this paper the pathophysiological basis of vascular stiffness, its clinical detection, importance to patient outcomes, and potential mechanisms for perioperative stroke are reviewed.

Pathophysiology of Vascular Stiffening

The central vasculature composed of the aorta and its main branches has cushioning and conduit functions. That is, in a compliant vasculature the aorta and proximal major arteries normally dampen pressure fluctuations generated from left ventricular ejection by a proportional increase in its lumen. Blood is then released during diastole resulting in near laminar flow in the arterioles and capillaries. Aging, and other conditions such as diabetes, is associated with morphological changes in arteries resulting in stiffening of the vessel.[16] Importantly, these changes can occur in the absence of intimal atherosclerosis and are more appropriately referred to as arteriosclerosis. Age-related vascular stiffness results from abnormal biologic processes ultimately leading to an increased collagen deposition and fragmentation of elastin fibers.[16] The mechanism of vascular stiffening is multifactorial and include inflammatory, genetic, and biochemical processes. Vascular smooth muscle cells undergo phenotypic changes from contractile cells to those that thicken, proliferate, and migrate to the intima. Cross-linking of extracellular matrix proteins resulting from advance glycation end-products using biochemical process similar to those generating hemoglobin A1C further contribute to vascular stiffening.

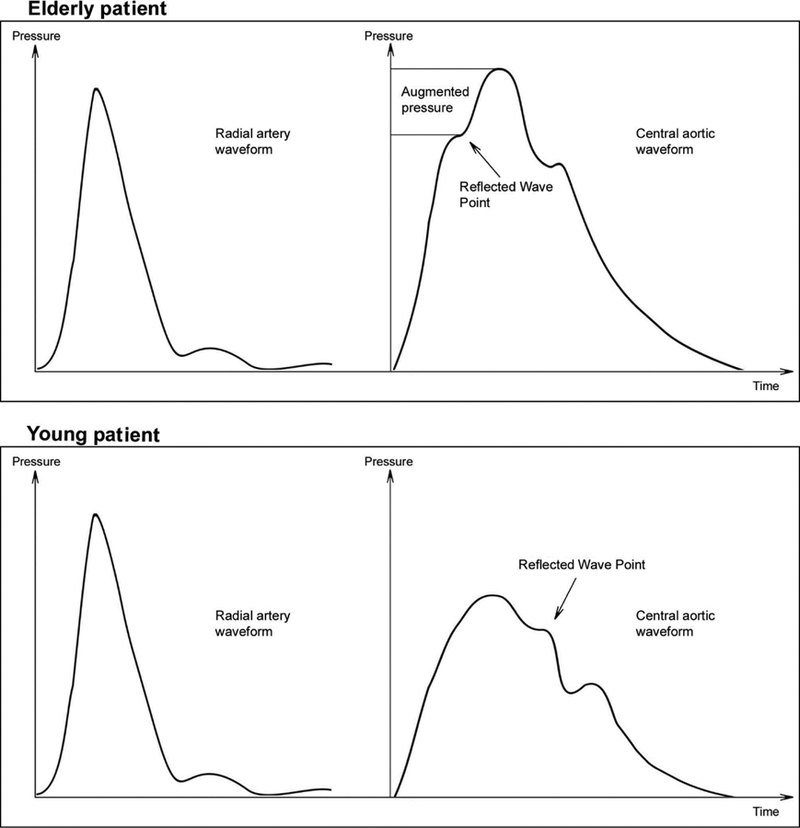

Vascular stiffening alters the cushioning properties of the central vasculature altering the dynamics of blood pressure. Left ventricular ejection generates a series of antegrade waves in the vasculature. These waves are then reflected back to the central vasculature upon reaching arterial branch points and small arteries. The resultant arterial waveform, thus, results from the summation of antegrade and reflected arterial waves. In a compliant vasculature, the reflected waves reach the central vasculature during diastole promoting diastolic organ blood flow. In a “stiff” vasculature, the central cushioning properties are attenuated increasing the velocity of ejected blood. This increased pulse wave velocity results in the transposition of the return of reflected waves to the central circulation from diastole to systole. The end result is the loss of diastolic blood flow augmentation and increased systolic blood pressure. These consequences of vascular stiffness explain its clinical manifestation of systolic hypertension, normal diastolic blood pressure, and elevated pulse pressure. A comparison of blood pressure waveforms in a patient with vascular stiffness and a younger patient with a more compliant vasculature is shown in Figure 1. This Figure illustrates the fact that peripheral hemodynamics are not as sensitive for detecting increased aortic stiffness compared with central blood pressure measurement as indicated by the similar radial artery pressure waveform in the elderly and young patient but distinct central aortic pressure waveforms. This phenomenon might be explained by the fact that the peripheral circulation is protected from arterial wave reflection that is manifest in the central circulation. Thus, rising pulse pressure measured in the brachial artery is likely a later indicator of vascular stiffness.

Figure 1.

Demonstration of radial artery and central aortic arterial pressure waveform from an elderly patient demonstrating vascular stiffness and a young patient with a compliant vasculature. The peripheral arterial waveforms of the elderly (top left panel) and younger patient (lower left panel) appear morphologically similar. The central aortic pressure waveform, however, demonstrate difference imparted by dynamics imposed on the waveform by elevated pulse wave velocity and early return of reflected waves. The arrow marks the point of return to the central circulation of the reflected arterial waves. The elderly patient (top right panel) demonstrates loss of diastolic augmentation and elevation of systolic pressure with the hallmark elevation in augmentation index (point between inflection of the pressure wave on the arterial waveform upstroke and systolic pressure. Reused with permission from Barodka, V.M., et al [8].

The early return of reflected arterial waves in systole results in increased left ventricular afterload.[8] This increased afterload leads to left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction. The brain and kidney are high blood volume flow organs with low vascular resistance resulting in their exposure to the pulsations of the central vasculature.[8] In a compliant vasculature, arterial pulsations are minimal and tolerated by these organs. However, elevated pulse pressure leads to exposure of the brain and kidney to high systolic pressure leading to compensatory arterial remodeling and, ultimately, microcirculatory damage.[8] In the brain, these changes may result in ischemic damage manifest as white matter hyperintensities and lacunar infarction on brain MRI.

Clinical Detection of Vascular Stiffness

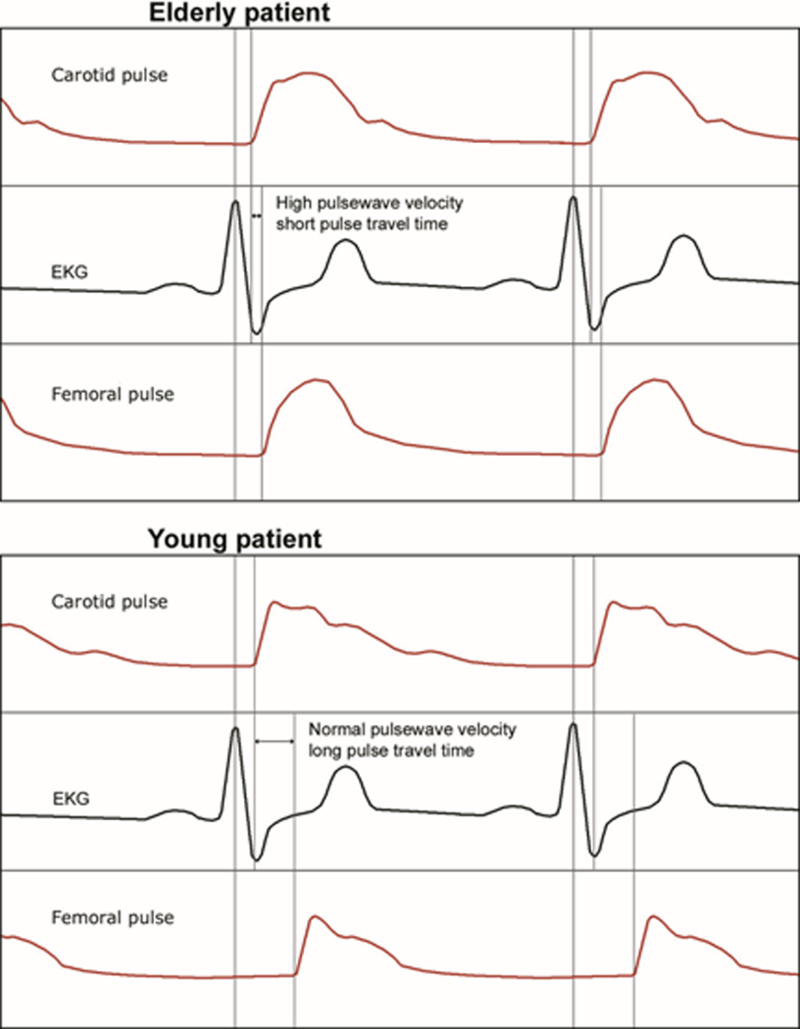

A hallmark of vascular stiffness is augmented systolic pressure and elevated pulse pressure. Pulse pressure over 60 mmHg is typically considered a marker of vascular stiffness. Measurement of peripheral blood pressure, however, may underestimate elevated central aortic pressure for various reasons including the fact that the return of reflected arterial waves during systole impact the aortic and not peripheral pulses.Several clinically applicable methods are available to assess for evidence of vascular stiffness as previously reviewed.[8] Augmentation index is estimated from a peripheral arterial pulse using applanation methods (see Figure 1). Measurement of pulse wave velocity (distance travel over unit of time) is more commonly reported as a reproducible indicator of vascular stiffness (Figure 2).[10] The time of arrival of the pulse relative to the ECG R wave is determined at a central site (ie, carotid artery) and a peripheral site (ie, radial or femoral artery). In healthy young adults pulse wave velocity is typically 6 m/s while in those > 65 years of age it is > 10 m/s with continued non-linear increase with progression in age. In population studies, an increase in pulse wave velocity of 1 standard deviation above the population norm is associated with a near 50% increase risk for a cardiovascular event (myocardial infarction, stroke, myocardial revascularization).[11] This was further demonstrated in the Framingham population showing increased aortic stiffness as assessed by pulse wave velocity is associated with an increased risk of first cardiovascular event and can be used predictively as a biomarker of cardiovascular disease.[12] Additionally, functional outcomes and lung function have been shown to be decreased when one standard deviation or higher from the mean pulse wave velocity was measured in an elderly population.[13]

Figure 2.

Pulse wave velocity measurements from an elderly and young patient. The pulse wave is measured with an applanation sensor placed on the carotid artery and femoroal artery representing central and peripheral arterial circulation, respectively. The pulse wave velocity is defined as the difference between distance between the carotid and femoral artery pulse upstroke divided by time (measured from the ECG. Reused with permission from Barodka, V.M., et al [8].

Vascular Stiffness and Prediction of Perioperative Stroke

Age-associated vascular stiffening is heterogeneously distributed in adults leading to the concept that “vascular age” is more sensitive for predicting adverse cardiovascular events than chronological age. Indeed, in the general population measures of vascular stiffness including elevated pulse pressure and elevated pulse wave velocity is associated with myocardial infarction, stroke, renal disease, cognitive decline including dementia, as well as mortality independent of age and other cardiovascular risk factors.[11, 14–19] In population studies, there is an 11% increase risk for stroke for every 10 mmHg increase in pulse pressure.[19]

The value of measures of vascular stiffness in predicting perioperative scomplications including stroke is increasingly appreciated (Table 1). In a retrospective review of data from 703 patients undergoing cardiac surgery, Benjo et al[5] evaluated the role of preoperative pulse pressure in predicting stroke over 348±215 days of follow-up. Pulse pressure was higher in patients with compared with those without stroke (81.2 mmHg versus 64.5 mmHg, P=0.0006). Pulse pressure predicted stroke in adjusted models independent of age, gender, and diabetes. In Kaplan-Meier analysis, stroke-free survival was lower (P=0.0067) in patients with a pulse pressure > 72 mmHg compared with those with pulse pressure < 72 mmHg. Using a large multi-center database comprised of 5436 patients undergoing CABG surgery, Fontes et al[6] reported that pulse pressure independently predicted myocardial and cerebral outcomes after surgery. An increase in pulse pressure of 10 mmHg above a threshold of 40 mmHg was associated with an increased risk of cerebral events or death. The incidence of cerebral events or mortality was nearly twice as high for patients with pulse pressure > 80 mmHg compared with ≤80 mmHg (5.5% versus 2.8%, P=0.004). Nikolov et al[7] reported on a series of 973 patients undergoing CABG surgery at their institution finding that elevated baseline pulse pressure (>78 mmHg) was independently associated with risk of mortality after a median follow-up of 7.3 years (P<0.001). The hazard ratio of mortality associated with elevated pulse pressure was 1.1 (95% confidence interval, 1.05 to 1.18) for each 10 mmHg increase in pulse pressure. In contrast, Mazzeffi et al[20] found no relationship between pulse pressure and 30-day or 1-year outcomes after infra-inguinal arterial bypass surgery. The latter might be explained by the high prevalence of elevated pulse pressure (44.6% of patients) lowering its predictive capacity in this cohort.

Table 1.

Studies linking vascular stiffness with adverse perioperative outcomes including stroke.

| Publication | Hypothesis | Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aronson et al.[4*] |

Preoperative elevated pulse pressure increases risk of perioperative renal dysfunction or failure |

Prospective data including baseline pulse pressure, collected on a group of patients undergoing CABG surgery. Variables predictive of renal dysfunction or failure determined in one cohort then validated in a second cohort. |

Elevated preoperative pulse pressure was identified as one of the risk factors associated with postoperative renal dysfunction or failure. |

| Benjo et al.[5*] | Pulse pressure is a predictive factor in risk for stroke after cardiac surgery |

Retrospective review of data from patients underwent CABG surgery. Brachial artery pulse pressure was measured. The incidence of stroke for an average follow- up of 348 ±215 days after surgery was determined. |

Pulse pressure was identified as an age independent predictor of stroke occurrence. |

| Fontes et al.[6*] | Increased pulse pressure is associated with risk for adverse vascular outcomes in patients undergoing CABG surgery. |

Prospective cohort study. Data from over 4000 patients undergoing CABG surgery were collected and the relationship between these factors and adverse vascular events were determined. |

Elevated pulse pressure was independently associated with cardiac and neurologic adverse outcomes. PP increment of 10mmHg associated with increased risk of cerebral events; a PP value over 80 mmHg was associated with almost double the incidence of cerebral event or death from neurologic complications. |

| Nikolov et al.[7] | Elevated pulse pressure is associated with decreased long term survival after CABG surgery. |

Prospective cohort study. Baseline preoperative pulse pressure and other variables collected from 973 patients prior to CABG. |

Elevated preoperative pulse pressure measurements as well as duration of cardiopulmonary bypass, diabetes, and Hannan risk index were predictive of decreased survival after a median follow-up of 7.3 years. |

| Oprea et al.[31] | To determine if baseline pulse pressure is associated with acute kidney injury and 30-day mortality after non-cardiac surgery. |

Retrospective review of data from 9125 patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery at a single center. |

Elevated pulse pressure was associated with the adjusted risk for acute kidney injury but not 30- day mortality. |

| Mazzeffi et al[20] | Increased baseline pulse pressure is associated with 30-day and 1-year mortality after lower extremity artery bypass surgery. |

Retrospective review of data from 556 patients undergoing infra-inguinal arterial bypass surgery. |

A large percentage (44.6%) of patients had elevated pulse pressure. There was no relationship between pulse pressure and 30-day (p=0.35) or 1- year (p-0.14) mortality. |

Potential Mechanisms for Stroke

Perioperative stroke occurring after cardiac surgery is thought to result from cerebral embolism and/or cerebral hypoperfusion.[3] Atherosclerosis of the ascending aorta is a major source of both macro- and micro-embolism during cardiac surgery. Aortic manipulations (e.g., aortic cannulation, cross-clamping, proximal bypass graft anastomosis) or from the flow dynamics of aortic cannula used for cardiopulmonary bypass can fracture atheroma generating athero-embolism. As mentioned, vascular stiffness occurs even in the absence of intimal-based atherosclerosis suggesting that the mechanism of stroke risk imparted by atherosclerosis of the ascending aorta cannot explain all strokes in patients with vascular stiffness. High flow, low vascular resistance organs such as the brain are exposed to the higher pulsation associated with pulse pressure hypertension.[8] Compensatory arteriolar hypertrophy of penetrating cerebral vessels can result in the hallmark of small vessel ischemic injury, white matter hyperintensities on brain MRI and lacunar stroke. The latter suggest that cerebral hypoperfusion during surgery might in fact result at least in part from cerebral hypoperfusion.

Our group has performed studies investigating the potential role of individual monitoring of cerebral blood flow autoregulation as a method to individualize blood pressure management during cardiopulmonary bypass.[21–28] An important early observation was that the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation varies markedly between individuals ranging from 40 mmHg to 90 mmHg. Thus, with current practices where blood pressure targets during surgery are determined empirically and based on historical practices, many patients may unintentionally have their blood pressures below their lower limit of cerebral autoregulation. We have further demonstrated that excursion of blood pressure outside the limits of cerebral autoregulation is associated with acute kidney injury, the composite outcome of major morbidity and operative mortality, postoperative delirium, and release of brain injury biomarkers. Consequently, varying exposure to blood pressure below and even above the limits of autoregulation exposes patients to the risk for organ injury.

In our studies we have found that as many as 20% of patients demonstrate impaired cerebral blood flow autoregulation during cardiopulmonary bypass.[23, 24] In this case, the cerebral circulation is unable to maintain constant cerebral blood flow such that the brain is potentially exposed to ischemia with low blood pressure and hyper-perfusion with high blood pressure. The presence of impaired cerebral autoregulation was found to be associated with postoperative stroke.[23, 24] In a recent analysis of our data we have found that impaired cerebral blood flow autoregulation is associated with white matter hyperintensities.[29] As mentioned, increased vascular stiffness leads to adaptive changes in the microcirculation resulting arteriolar remodeling of small penetrating vessels, lacunar infarction, and white matter hypertensities detected with brain MRI. We further have found in a study of 181 patients a relationship between a measure of vascular stiffness and the likelihood of having the lower limit of cerebral blood flow autoregulation > 65 mmHg. In that study, the presence of vascular stiffness was determined using the ambulatory arterial stiffness index which is defined as 1 minus the slope of the plot of diastolic (x-axis) and systolic pressures. The basis for this measurement is that the change in systolic pressure for a given diastolic pressure is higher in as stiff versus a compliant vasculature.[30*] Notably, peripheral pulse pressure was not predictive of the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation. Regardless, the combined data suggests that patients with vascular stiffness may be prone to cerebral hypoperfusion during surgery and that they may benefit from individualizing blood pressure targets using cerebral autoregulation monitoring.

Conclusion

Vascular stiffness is common in surgical patients particularly the elderly manifesting as systolic pressure hypertension, high pulse pressure, prominent augmentation index, or elevated pulse wave velocity. Vascular stiffness is associated with acute kidney injury, cognitive decline, and mortality in the general population. Other data shows a strong relationship between elevated pulse pressure and stroke, acute kidney injury, and mortality after cardiac surgery. Patients with vascular stiffness may have impaired cerebral blood flow autoregulation and/or an elevated lower limit of cerebral autoregulation increasing vulnerability to cerebral hypo-perfusion during surgery. Careful blood pressure management is needed in affected patients to avoid brain injury.

Key Points.

Vascular stiffness alters the normal cushioning and conduit function of the central circulation leading to early return of reflected arterial waves resulting in elevated systolic pressure, high pulse pressure, and normal to low diastolic blood pressure.

Elevated central aortic pressures results in transmission of pulsations generated by left ventricular ejection to high flow, low vascular resistance organs such as the brain and kidney.

Adaptation to arteriolar pulse pressure in the brain and kidney include arteriolar hypertrophy limiting blood flow especially small penetrating blood vessels of the brain which leads to pressure dependence of flow, lacunar stroke, and white matter hypertrophy on brain MRI.

Indicators of vascular stiffness such as high pulse pressure, elevated augumentation index, and fast pulse wave velocity is associate with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in the general population and acute kidney injury, stroke, and mortality after cardiac surgery supporting the concept that “vascular age” may be more predictive of such events that “chronological age”.

A higher lower limit of cerebral blood flow autoregulation and a higher likelihood of impaired cerebral autoregulation may expose patients with vascular stiffness to postoperative neurological complications such as delayed neurocognitive recovery and stroke.

Acknowledgements

Financial Support

Funded in part by Grant Number RO1 092259 from the National Institutes of Health to Dr. Hogue

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Hogue serves as an advisor and is paid lecturer for Medtronic, Inc (Minneapolis, MN), a maker of near infrared spectroscopy units.

References

- 1.Howden L and Meyer J Age and Sex Composition: 2010. United States Census Bureau, 2011. 1–16.

- 2.Brooks Carthon JM, et al. , Variations in postoperative complications according to race, ethnicity, and sex in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2013. 61(9): p. 1499–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogue CW Jr., Gottesman R, and Stearns J, Cerebral injury after cardiac surgery Critical Care Clin of North America, 2008. 24: p. 83–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronson S, et al. , Risk index for perioperative renal dysfunction/failure: critical dependence on pulse pressure hypertension. Circulation, 2007. 115: p. 733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjo A, et al. , Pulse pressure is an age-independent predictor of stroke development after cardiac surgery. Hypertension, 2007. 50: p. 630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontes M, et al. , Pulse pressure and risk of adverse outcome in coronary bypass surgery. Anesth Analg, 2008. 107: p. 1122–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nikolov NM, et al. , Pulse pressure and long-term survival after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Anesth Analg, 2010. 110(2): p. 335–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barodka VM, et al. , Review article: implications of vascular aging. Anesth Analg, 2011. 112(5): p. 1048–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Rourke M and Safar M, Relationship between aortic stiffening and microvascular disease in brain and kidney. Hypertension, 2005. 46: p. 200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asmar R, et al. , Assessment of arterial distensibility by automatic pulse wave velocity measurement: validation and clinical application studies. Hypertension, 1995. 26: p. 485–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, and Stefanadis C, Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2010. 55(13): p. 1318–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell GF, et al. , Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation, 2010. 121(4): p. 505–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunner EJ, et al. , Arterial stiffness, physical function, and functional limitation: the Whitehall II Study. Hypertension, 2011. 57(5): p. 1003–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safar M, Levy B, and Struijker-Boudier H, Current perspectives on arterial stiffness and pulse pressure in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases Circulation 2003. 107: p. 2864–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurent S, et al. , Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension, 2001. 37: p. 1236–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris MC, et al. , Association of incident Alzheimer disease and blood pressure measured from 13 years before to 2 years after diagnosis in a large community study. Arch Neurol, 2001. 58(10): p. 1640–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kilander L, et al. , Hypertension is related to cognitive impairment: a 20-year follow-up of 999 men. Hypertension, 1998. 31(3): p. 780–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skoog I, et al. , 15-year longitudinal study of blood pressure and dementia. Lancet, 1996. 347: p. 1141–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domanski MJ, et al. , Isolated systolic hypertension : prognostic information provided by pulse pressure. Hypertension, 1999. 34(3): p. 375–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzeffi M, et al. , Preoperative arterial pulse pressure has no apparent association with perioperative mortality after lower extremity arterial bypass. Anesth Analg, 2012. 114(6): p. 1170–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brady K, et al. , Real-time continuous monitoring of cerebral blood flow autoregulation using near-infrared spectroscopy in patients undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass. Stroke, 2010. 41(9): p. 1951–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joshi B, et al. , Predicting the limits of cerebral autoregulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg, 2012. 114(3): p. 503–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joshi B, et al. , Impaired autoregulation of cerebral blood flow during rewarming from hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass and its potential association with stroke. Anesth Analg, 2010. 110(2): p. 321–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ono M, et al. , Risks for impaired cerebral autoregulation during cardiopulmonary bypass and postoperative stroke. Br J Anaesth, 2012. 109(3): p. 391–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ono M, et al. , Blood pressure excursions below the cerebral autoregulation threshold during cardiac surgery are associated with acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med, 2013. 41(2): p. 464–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono M, et al. , Duration and magnitude of blood pressure below cerebral autoregulation threshold during cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with major morbidity and operative mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg, 2014. 147(1): p. 483–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hori D, et al. , Arterial pressure above the upper cerebral autoregulation limit during cardiopulmonary bypass is associated with postoperative delirium. Br J Anaesth, 2014. 113(6): p. 1009–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hori D, et al. , Hypotension After Cardiac Operations Based on Autoregulation Monitoring Leads to Brain Cellular Injury. Ann Thorac Surg, 2015. 100(2): p. 487–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nomura Y, et al. , Cerebral Small Vessel, But Not Large Vessel Disease, Is Associated With Impaired Cerebral Autoregulation During Cardiopulmonary Bypass: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Anesth Analg, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.**.Obata Y, et al. , Relationship Between the Ambulatory Arterial Stiffness Index and the Lower Limit of Cerebral Autoregulation During Cardiac Surgery. J Am Heart Assoc, 2018. 7(4).Analysis of prospectively collected data demonstrating that patients with evidence of vascular stiffness are more likely to have an elevated lower limit of cerebral autoregulation, thus, requirieng higher blood pressure during cardiac surgery.

- 31.Oprea AD, et al. , Baseline Pulse Pressure, Acute Kidney Injury, and Mortality After Noncardiac Surgery. Anesth Analg, 2016. 123(6): p. 1480–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]