Abstract

The intracellular concentration of calcium ions ([Ca2+]i) is a critical regulator of cell signaling and contractility of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). In this study, we employed an atomic force microscopy (AFM) nanoindentation-based approach to investigate the role of [Ca2+]i in regulating the cortical elasticity of rat cremaster VSMCs and the ability of rat VSMCs to adhere to fibronectin (Fn) matrix. Elevation of [Ca2+]i by Ionomycin treatment increased rat VSMC stiffness and cell adhesion to Fn-biofunctionalized AFM probes, whereas attenuation of [Ca2+]i by BAPTA-AM treatment decreased the mechanical and matrix adhesive properties of VSMCs. Furthermore, we found that Ionomycin/BAPTA-AM treatments altered expression of α5 integrin subunits and α smooth muscle actin (αSMA) in rat VSMCs. These data suggest that [Ca2+]i regulates VSMC elasticity and adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM) by a potential mechanism involving changing dynamics of the integrin-actin cytoskeleton axis.

Keywords: Atomic force microscopy, vascular smooth muscle cell, calcium, elasticity, adhesion

Introduction

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) are a major cellular constituent of the arterial wall. The contractility and stiffness of VSMCs contribute to active stress present in the vessel wall (Qiu H.Y., et al., 2010). VSMCs have both contractile and non-contractile cytoskeletons capable of rapidly remodeling (Metz R.P., et al., 2012). The remodeling of actin cytoskeleton and alterations of integrin-mediated adhesion to the extracellular matrix (ECM) has an impact on the mechanics of VSMCs as well as their contribution to vascular wall mechanical properties (Hong Z.K., et al., 2012, 2014 and 2015; Sehgel N.L., et al., 2013 and 2015). In this study, we utilized atomic force microscopy (AFM) and confocal immunofluorescent microscopy to investigate effects of intracellular calcium ion concentrations ([Ca2+]i) on the mechanical and matrix adhesion properties of rat VSMCs. This work developed in-depth knowledge and insights into the dynamic behavior of intracellular calcium ion in regulation of VSMC elasticity and adhesive interactions with the ECM.

Materials and Methods

Vascular smooth muscle cell isolation, cell culture, and treatments

Male Sprague-Dawley rats at 6-7 weeks of age were utilized in this study. Primary VSMCs were isolated from cremaster muscle arterioles by an enzymatic digestion method as described previously (Jackson T.Y., et al., 2010). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 10 mmol/L HEPES, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B and used at passages 0. Subgroups of VSMCs were treated by 0.2 μmol/L Ionomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 0.2 μmol/L BAPTA-AM (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or an equal volume of DMEM without FBS (vehicle control) for 30 minutes using a micro-delivering drug technique during the course of continuous AFM investigation (Zhu Y., et al., 2012; Sehgel N.L., et al., 2013). In the BAPTA-AM-treated group, cells were given 0.2 μmol/L BAPTA-AM 1 hour prior to AFM/confocal microscopy measurements. We have previously determined that 0.2 μmol/L was an optimal concentration for both Ionomycin and BAPTA-AM treatments of rat cremaster VSMCs (Sun Z., et al., 2012).

AFM nanoindentaton-based imaging and mechanical testing

Following AFM calibration, AFM probes were operated to perform contact mode scanning of cell surface at a speed of 35-40 μm/sec with a 300-500 pN tracking force. The height and deflection data were collected and processed using the Nanoscope III software (Veeco Metrology, Inc.) to provide topographical images of VSMCs.

For cell elasticity and adhesion force measurements, AFM probes (model MLCT) were silicon nitride microlevers with a spring constant ranging 10-30 pN/nm (Veeco Mertrology Inc., Santa Barbara, CA). AFM probes were functionalized with 1 mg/mL fibronectin (Fn) (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) for measurements of cell adhesion. Retraction curves were interpreted for cell adhesion by software NForceR (registration number TXu1-328-659). VSMC elastic modulus was translated from the force curves into Young’s modulus using a modified Hertz model. The calculation of the elastic modulus was:

where the indentation force (F) was stated and described using Hooke’s law (F =κΔx, κ and Δx denote the AFM probe’s spring constant and the probe’s apparent deflection). The indentation depth (δ) is identified from the difference in the AFM piezo movement in the z direction and the AFM probe deflection. E is the Young’s modulus of the experimental cell as the value of elasticity, and ν denotes 0.5 for cell as the Poisson ratio. The numerical α is the semi-included angle of the cone for a pyramidal tipped probe and determined by the probe shape.

Singular spectrum analysis of oscillation waveforms for assessment of dynamic cell stiffness

AFM-based measurements of dynamic stiffness in the presence or absence of Ionomycin and BAPTA-AM in single VSMCs and singular spectrum analysis of the oscillation waveform were performed as described in our previous studies (Hong Z.K., et al., 2012; Zhu Y., et al., 2012). Briefly, force curves were continuously recorded and collected during the course of AFM measurements. The curves were used to determine stiffness of VSMCS in the presence or absence of drugs. A spectral analysis procedure was exploited for cell elasticity analysis following translation of the oscillation waveforms and subsequent evaluation of linear trends. To reveal the average group behavior of the oscillations, three values of amplitude, frequency, and phase for every experimental subject were further investigated and averaged. Phase () was a simple mean. Frequency (f) was converted to periods (1/f) ahead of averaging. Amplitude (A) was log10-transformed before averaging the mean. The mean period and mean log-amplitude were then transformed back to frequency and amplitude. A composite time series for each treatment set was constructed as:

where b1 and b0 denote respectively the slope and intercept of the linear trend, and the bar above each component indicates the average value.

Confocal immunofluorescent microscopy

Confocal immunofluorescent analysis was performed as described in our previous studies (Qiu H.Y., et al., 2010). Briefly, VSMCs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes and washed by AB buffer (1× PBS / 1% BSA / 0.3% Triton X-100, pH 7.4). Fixed cells were incubated with anti-α5 integrin and anti-α smooth muscle actin (αSMA) antibodies at 4°C overnight followed by fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 hour. Confocal microscopic analysis was performed on a Veeco Bioscope 2-Olympus FV1000 system. The intensity of positive signals was quantified by Imaris software.

Statistical analysis

The comparisons of oscillatory frequencies, amplitudes, and phases were performed using multifactor ANOVA. Analyses of frequencies and amplitudes were based on the transformed values (i.e. periods and log-amplitudes). Comparisons of elasticity changes following drug treatments were analyzed using Student’s t-test. Differences between selected pairs of means were tested for significance with single-degree of freedom contrasts. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed with an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test for VSMC adhesion probability to Fn. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. In Table 2, average frequencies and amplitude are listed as 1/(mean period) and antilog (mean amplitude). Standard errors of the mean frequency or mean amplitude are estimated from confidence intervals that were computed around the mean periods and mean log-amplitudes and then reverse transformed to frequency and amplitude (Zhu Y., et al., 2012; Sehgel N.L., et al., 2013).

Table 2:

Numeric data of the elasticity oscillatory components in rat cremaster VSMCs

| Elasticity(kPa) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 0.2μM Ionomycin | 0.2 μM BAPTA-AM | ||

| Component | Parameter | |||

| 1 | Frequency(Hz) | 0.015±0.0054 | 0.0027*±0.00062 | 0.0019*±0.00056 |

| 2 | Frequency(Hz) | 0.033±0.0074 | 0.019±0.0066 | 0.021±0.0058 |

| 3 | Frequency(Hz) | 0.058±0.0053 | 0.041±0.0071 | 0.031±0.0090 |

| 1 | Amplitude(kPa) | 0.23±0.10 | 0.68±0.19 | 0.41±0.17 |

| 2 | Amplitude(kPa) | 0.14±0.068 | 0.23±0.048 | 0.10±0.041 |

| 3 | Amplitude(kPa) | 0.094±0.042 | 0.14*±0.035 | 0.066*±0.0086 |

| 1 | Phase(s) | 3.28±0.88 | 1.58±0.67 | 3.18±0.63 |

| 2 | Phase(s) | 2.63±0.95 | 3.65±0.60 | 1.88±0.51 |

| 3 | Phase(s) | 3.01±0.76 | 2.13±0.97 | 2.45±0.39 |

| - | Intercept (kPa) | 8.38±1.26 | 14.54*±1.37 | 4.23*±0.82 |

| - | Slope (kPaS−1) | 0.0013 | 0.010* | 0.0033 |

| ±0.00039 | ±0.0048 | ±0.0012 | ||

| N | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

p<0.05 for comparisons of data sets between the Ionomycin or BAPTA-AM group vs. baseline group.

Results and Discussion

[Ca2+]i regulates VSMC topography, elasticity, and adhesion to fibronectin matrix

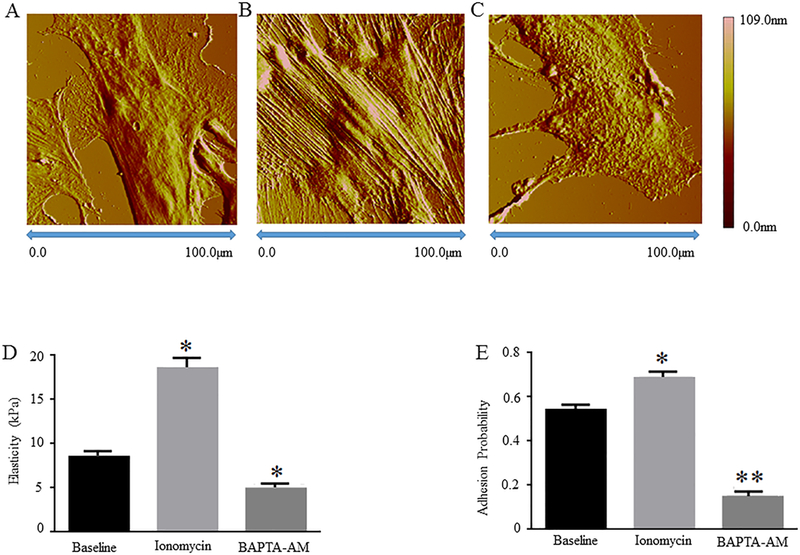

Ca2+ is an important intracellular messenger that transmits both biophysical and biochemical signals to regulate a wide range of cellular functions, including the contractile properties of VSMCs (Uehata M., et al., 1997; Bootman M.D., 2012). Ionomycin is a pharmacological agent which functions to raise intracellular Ca2+ levels by stimulating Ca2+ release from intracellular organelles, such as sarco/endoplasmic reticulum, and by regulating the entry of Ca2+ from extracellular space via specific ion channels (Morgan A.J., et al., 1994). In contrast, BAPTA-AM is an intracellular Ca2+ chelator which functions to decrease intracellular Ca2+ levels (Schillers H., et al., 2010). In this study, primary VSMCs isolated from rat cremaster arterioles (passage 0) were incubated in the presence or absence of Ionomycin or BAPTA-AM. We have previously demonstrated that Ionomycin and BAPTA-AM increased and decreased [Ca2+]i in rat VSMCs, respectively (Sun Z., et al., 2012) and these results were confirmed in the current study (data not shown). AFM deflection imaging analyses show that the areas of VSMCs are 10,200 ± 36 μm2 at baseline, 10,659 ± 154 μm2 by Ionomycin treatment, and 10,019 ± 28 μm2 by BAPTA-AM treatment (n = 8 cells from 3 animals per group). The heights of rat VSMCs are 3,417 ± 58 nm at baseline, 3,712 ± 102 nm by Ionomycin treatment, and 3,159± 58 nm by BAPTA-AM treatment (n = 8 cells from 3 animals per group). Both Ionomycin-induced increases and BAPTA-AM-induced decrease of VSMC areas/heights are statistically significant as compared to cell area/height at baseline (Fig. 1 A - C, and Table 1). These data suggest that topographic features of rat cremaster VSMCs are regulated by [Ca2+]i.

Figure 1: AFM nanoindentation analyses of topography, stiffness, and adhesion probability of rat VSMCs treated with or without Ionomycin/BAPTA-AM.

Rat cremaster VSMCs at passage 0 were cultured in the presence or absence of 0.2 μmol/L Ionomycin or BAPTA-AM. Representative AFM deflection images are shown for A, the control VSMCs, B, VSMCs treated by Ionomycin, and C, VSMCs treated by BAPTA-AM. Graphs show comparisons of D, stiffness and E, adhesion probability in the control, Ionomycin-treated, and BAPTA-AM-treated rat VSMCs. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 5 cells from 3 rats per group. **p<0.01 and *p<0.05 for comparisons between the control vs. drug-treated cells.

Table 1:

AFM-based measurements of rat cremaster VSMC area and height

| Baseline | Ionomycin treatment | BAPTA-AM treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell area (μm2) | 10,200±36 | 10,659*±154 | 10,019*±28 |

| Cell Height (nm) | 3,417±58 | 3,712*±102 | 3,159*±58 |

| N | 8 | 8 | 8 |

p<0.05 for comparisons of cell area and height between Ionomycin or BAPTA-AM treatment vs. baseline.

To determine effects of Ionomycin and BAPTA-AM treatments on rat VSMC elasticity and adhesion to Fn matrix, we employed an AFM nano-indentation protocol with Fn-coated probes, which was developed in our laboratory previously (Qiu H.Y., et al., 2010; Zhu Y., et al., 2012). Matrix adhesion probability was assessed by interactions between rat VSMCs and Fn-coated AFM probes. We found that both the elasticity and Fn adhesion probability of VSMCs significantly increased after Ionomycin treatment and significantly decreased in response to BAPTA-AM treatment as compared to cells treated by the vehicle control (Fig. 1, D and E). These data suggest that [Ca2+]i regulates both the mechanical properties of rat cremaster VSMCs and the ability of these cells to adhere to Fn matrix.

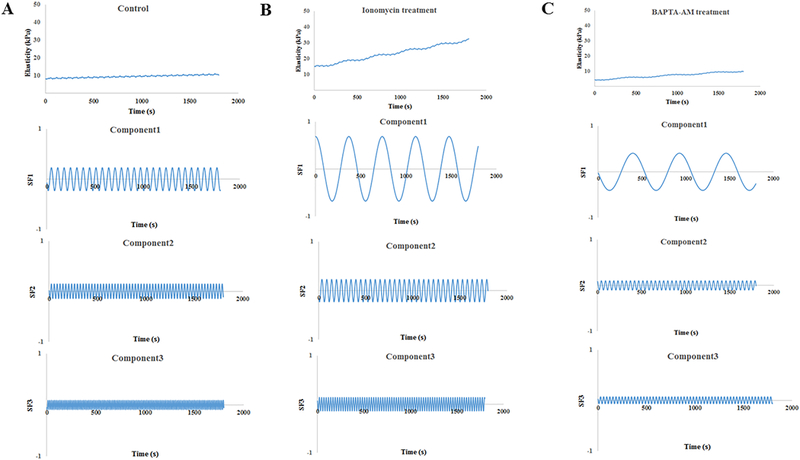

Mathematical resolution of the elasticity waveforms confirms a regulatory role of [Ca2+]i in VSMC elasticity

We further evaluated elasticity waveforms of single VSMCs by a spectral analysis approach. We have previously shown that this approach can provide the mathematical decomposition of the elasticity waveforms for VSMCs in the presence or absence of drugs by three principle components of oscillatory behavior at a single cell level, which indirectly reflects local cytoskeletal architectures and intrinsic cytoskeletal stiffness of VSMCs (Hong Z.K. et al., 2014 and 2015). The single VSMC elasticity waveform revealed three spectral components in which each of three frequency components differentiated from comprehensive elasticity data at baseline and treated by drugs (Fig. 2 and Table 2). The first frequency component (Component 1) significantly slowed in drug-treated cells in comparison to the control cells. However, the frequencies in Components 2 and 3 did not show significant differences between the control and drug-treated cells. Furthermore, each amplitude of the three frequency components was not significantly distinguished between the control and drug-treated cells. The amplitude of oscillation for the third components significantly increased in Ionomycin-treated VSMCs in comparison to the baseline. In contrast, BAPTA-AM treatment significantly decreased the amplitude of oscillation of the third components (Table 2). The slope and intercept showed a linear trend of single VSMC elasticity waveform. The intercept of oscillation was significantly increased in Ionomycin-treated VSMCs in comparison to the baseline. In contrast, BAPTA-AM significantly decreased the intercept of oscillation (Fig. 2). Collectively, these data further support that [Ca2+]i regulates the elasticity of rat cremaster VSMCs.

Figure 2: Mathematical analysis of the elasticity waveforms in the control and Ionomycin/BAPTA-AM-treated rat VSMCs by three principle components of oscillation.

The oscillatory waveforms of elastic modulus in a comprehensive format (top panel) and three oscillatory components (lower three panels) are shown for A, the control VSMCs, n = 9 cells from 3 rats, B, Ionomycin-treated VSMCs, n = 5 cells from 3 rats, and C, BAPTA-AM-treated VSMCs, n = 11 cells from 3 rats. The apparent values of frequency, amplitude and phase are shown in Table 2.

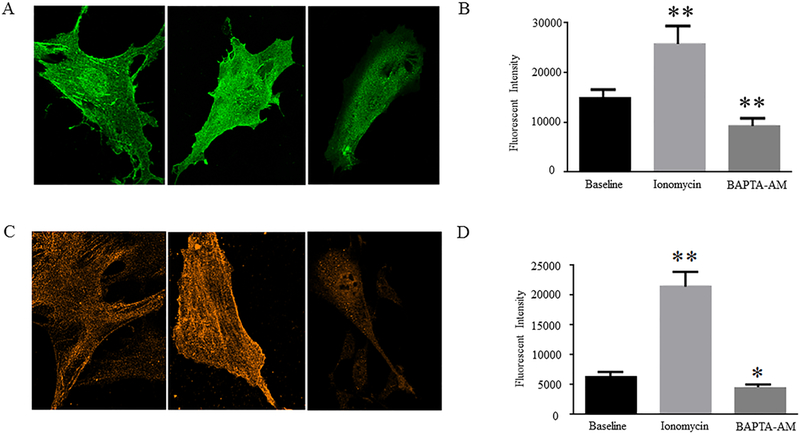

[Ca2+]i regulates expression of α5 integrin and αSMA in VSMCs

The actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesions are known to regulate cell stiffness and cell adhesion to the ECM (Yamin R., et al., 2012). We have previously demonstrated that αSMA, a major cytoskeletal component, responds to externally applied forces and mediates changes in the stiffness and adhesive properties of VSMCs (Sun Z., et al., 2005, 2008 and 2012; Qiu H.Y., et al., 2010). To investigate the potential mechanisms by which [Ca2+]i regulates rat VSMC elasticity and adhesion to Fn matrix, we compared expression of αSMA and α5 integrin subunit, a focal adhesion component, in the presence or absence of Ionomycin/BAPTA-AM by confocal immunofluorescent microscopy. We found that Ionomycin significantly increased, whereas BAPTA-AM significantly decreased, expression of α5 integrin subunit and αSMA in rat VSMCs as compared to the control cells (Fig. 3). Furthermore, it appears that the formations of α5 integrin-positive focal adhesions and αSMA-positive stress fibers were increased by Ionomycin and were decreased by BAPTA-AM treatments. Collectively, these data suggest that α5 integrin and αSMA may mediate [Ca2+]i-regulated rat VSMC elasticity and adhesion to Fn matrix. Future studies will delineate the molecular mechanisms by which α5 integrin-actin cytoskeleton axis mediates [Ca2+]i-regulated VSMC stiffness and ECM adhesion.

Figure 3: Effects of Ionomycin/BAPTA-AM treatments on expression of α5 integrin subunits and αSMA in rat VSMCs.

Representative confocal immunofluorescent images show A, α5 integrin expression and C, αSMA expression in the control, Ionomycin-treated, and BAPTA-AM-treated rat VSMCs. Graphs show comparisons of the intensities of B, α5 integrin-positive signals and D, αSMA-positive signals among different cell groups. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM; n = 40 cells from 3 rats in the control group; n = 32 cells from 3 rats in Ionomycin-treated group; and n = 34 from 3 rats in BAPTA-AM-treated group. **p<0.01 and *p<0.05 for comparisons between the control vs. drug-treated cells.

Conclusions

This AFM nanoindentation-based study demonstrates a functional role of [Ca2+]i in regulation of VSMC elasticity and ECM adhesion. The findings may open up a new avenue for treatment of arterial stiffening and hypertension utilizing the VSMC-targeting strategy.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Yong Zhou’s laboratory is currently supported by research funds from National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL124076 and R01HL139584) and National Eye Institute (R01EY027924) of the National Institutes of Health, and from School of Medicine (AMC21 R01 Award), University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Grant sources: NIH grants R01HL124076, R01HL139584, and R01EY027924 to Yong Zhou; University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine AMC21 R01 Award to Yong Zhou

References

- Bootman MD (2012). Calcium signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 4, a011171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Sun Z, Li Z, Mesquitta WT, Trzeciakowski JP & Meininger GA (2012). Coordination of fibronectin adhesion with contraction and relaxation in microvascular smooth muscle. Cardiovasc Res, 96, 73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Sun Z, Li M, Li ZH, Bunyak F, Ersoy I, Trzeciakowski JP, Staiculescu MC, Jin M, Martinez-Lemus L, Hill MA, Palaniappan K & Meininger GA (2014).Vasoactive agonists exert dynamic and coordinated effects on vascular smooth muscle cell elasticity, cytoskeletal remodelling and adhesion. J Physiol, 592, 1249–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Reeves KJ, Sun Z, Li Z, Brown NJ & Meininger GA (2015). Vascular smooth muscle cell stiffness and adhesion to collagen I modified by vasoactive agonists. PloS One, 10, e0119533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson TY, Sun Z, Martinez-Lemus LA, Hill MA & Meininger GA (2010). N-Cadherin and Integrin Blockade Inhibit Arteriolar Myogenic Reactivity but not Pressure-Induced Increases in Intracellular Ca2+. Front Physiol, 1, 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz RP, Patterson JL & Wilson E (2012). Vascular smooth muscle cells: isolation, culture, and characterization. Methods Mol Biol, 843,169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan AJ & Jacob R (1994). Ionomycin enhances Ca2+ influx by stimulating store-regulated cation entry and not by a direct action at the plasma membrane. Biochem J, 300, 665–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu HY, Zhu Y, Sun Z, Trzeciakowski JP, Gansner M, Depre C, Resuello Ranillo RG, Natividad FF, Hunter WC, Genin GM, Elson EL, Vatner DE, Meininger GA & Vatner SF (2010). Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Stiffness as a Mechanism for Increased Aortic Stiffness with Aging. Circ Res, 107, 615–619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schillers H, Walte M, Urbanova K & Oberleithner H (2010). Real-time monitoring of cell elasticity reveals oscillating myosin activity. Biophys J, 99, 3639–3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgel NL, Zhu Y, Sun Z, Trzeciakowski JP, Hong Z, Hunter WC, Vatner DE, Meininger GA & Vatner SF (2013). Increased vascular smooth muscle cell stiffness: a novel mechanism for aortic stiffness in hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 305, H1281–H1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgel NL, Sun Z, Hong Z, Hunter WC, Hill MA, Vatner DE, Vatner SF & Meininger GA (2015). Augmented vascular smooth muscle cell stiffness and adhesion when hypertension is superimposed on aging. Hypertension, 65, 370–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Martinez-Lemus LA, Trache A, Trzeciakowski JP, Davis GE, Pohl U & Meininger GA (2005). Mechanical properties of the interaction between fibronectin and α5β1-integrin on vascular smooth muscle cells studied using atomic force microscopy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 289, H2526–H2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Martinez-Lemus LA, Hill MA & Meininger GA (2008). Extracellular matrix-specific focal adhesions in vascular smooth muscle produce mechanically active adhesion sites. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol, 295, C268–C278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Li Z & Meininger GA (2012). Mechanotransduction through fibronectin-integrin focal adhesion in microvascular smooth muscle cells: is calcium essential? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 302, H1965–H1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehata M, Ishizaki T, Satoh H, Ono T, Kawahara T, Morishita T, Tamakawa H, Yamagami K, Inui J, Maekawa M & Narumiya S (1997). Calcium sensitization of smooth muscle mediated by a Rho-associated protein kinase in hypertension. Nature, 389, 990–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamin R & Morgan KG (2012). Deciphering actin cytoskeletal function in the contractile vascular smooth muscle cell. J Physiol, 590, 4145–4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y, Qiu H, Trzeciakowski JP, Sun Z, Li Z, Hong Z, Hill MA, Hunter WC, Vatner DE, Vatner SF & Meininger GA (2012). Temporal analysis of vascular smooth muscle cell elasticity and adhesion reveals oscillation waveforms that differ with aging. Aging Cell, 11,741–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]