Abstract

Dopamine receptors regulate exocytosis via protein–protein interactions (PPIs) as well as via adenylyl cyclase transduction pathways. Evidence has been obtained for PPIs in inner ear hair cells coupling D1A to soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) attachment protein receptor (SNARE)-related proteins snapin, otoferlin, N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF), and adaptor-related protein complex 2, mu 1 (AP2mu1), dependent on [Ca2+] and phosphorylation. Specifically, the carboxy terminus of dopamine D1A was found to directly bind t-SNARE-associated protein snapin in teleost and mammalian hair cell models by yeast two-hybrid (Y2H) and pull-down assays, and snapin directly interacts with hair cell calcium-sensor otoferlin. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis, competitive pull-downs, and co-immunoprecipitation indicated that these interactions were promoted by Ca2+ and occur together. D1A was also found to separately interact with NSF, but with an inverse dependence on Ca2+. Evidence was obtained, for the first time, that otoferlin domains C2A, C2B, C2D, and C2F interact with NSF and AP2mu1, whereas C2C or C2E do not bind to either protein, representing binding characteristics consistent with respective inclusion or omission in individual C2 domains of the tyrosine motif YXXΦ. In competitive pull-down assays, as predicted by KD values from SPR (+Ca2+), C2F pulled down primarily NSF as opposed to AP2mu1. Phosphorylation of AP2mu1 gave rise to a reversal: an increase in binding by C2F to phosphorylated AP2mu1 was accompanied by a decrease in binding to NSF, consistent with a molecular switch for otoferlin from membrane fusion (NSF) to endocytosis (AP2mu1). An increase in phosphorylated AP2mu1 at the base of the cochlear inner hair cell was the observed response elicited by a dopamine D1A agonist, as predicted.

Introduction

The specific elements of the adenylyl cyclase signal transduction pathway in trout saccular hair cells [1,2] are those present in higher vertebrates for dopamine receptor transduction pathways: dopamine D1 couples to Gαolf [3,4], which couples to adenylyl cyclase type 5/6 [5]. Dopamine D2 signal transduction also occurs through adenylyl cyclase 5 (AC5) [6]. Furthermore, dopamine D2 receptor activation can down-modulate Gαs activation of AC9 [7], and AC9 is one of the detected AC transcripts in trout saccular hair cells [1]. A transcript for the dopamine D1 receptor was detected in the saccular model hair cell preparation (GenBank accession no. EU371401) and determined to resemble most closely dopamine D1A4 and D1A3 of carp (CAA74971 and CAA74970, respectively). Protein for dopamine receptors D1A and D2L has been immunolocalized to mammalian vestibular hair cells, consistent with expression of respective hair cell transcripts in teleost saccular hair cells [1,2]. Loss of dopamine, and by inference, dopamine receptor input to mammalian vestibular end organs, has been reported in Parkinson’s disease [8].

It is well appreciated that in addition to utilizing second messenger pathways, including the adenylyl cyclase pathways, for signal transduction, dopamine receptors participate in molecular pathways via dopamine receptor-interacting proteins or DRIPs, recognized to influence the binding of other receptors, e.g. AMPA receptors, to key components such as N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) associated with SNAREs. Molecular pathways involved in dopaminergic D1A modulation of afferent signaling in the model vestibular hair cell preparation have now been elucidated with protein–protein interaction (PPI) protocols applied to the teleost saccular hair cells and verified for mammalian cochlear organ of Corti (OC) proteins. Preliminary reports have appeared [9–11].

Experimental

Polymerase chain reaction analysis

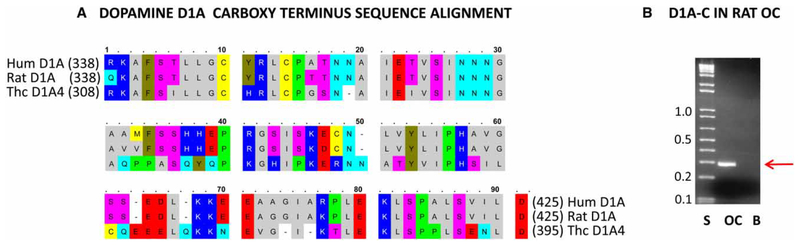

For bait, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) primers were designed with Accelrys software (San Diego) targeting the intracellular carboxy terminus of dopamine D1A4 cDNA sequence (GenBank accession no. EU371401) expressed in trout saccular hair cells, corresponding to amino acid (aa) 308–395 (ACA96732.1, Figure 1A). PCRs were carried out in either 25 or 50 μl reaction volumes containing a BD Advantage 2 polymerase mix (BD Biosciences Clontech, San Jose, CA). The temperature profile of the PCRs was 95°C for 1 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 2 min, followed by a 5-min extension at 68°C. Appropriately sized PCR products were taken from low melting point agarose gels, and the DNA was extracted using a Qiaex II PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, U.S.A.), sequence-verified, and amplified with primers to which EcoR1 and BamH1 restriction sites were added at the 5’ ends of upstream and downstream primers (5’-GCCGAATTCCGCAAAGCATTCTCCATC-3’ and 5’-TGCGGATCCTTAATCCAAGTTTTCAGAAAG-3’, respectively; restriction sites were underlined).

Figure 1. Dopamine D1A carboxy sequence alignment and PCR amplification from rat OC.

(A) Alignment (with OMIGA 2.0) of the carboxy terminus aa sequences of trout hair cell (HC) D1A4 (ACA96732) with rat D1A (NP_036678) and human D1A (NP_000785). (B) PCR amplification of an ~286 bp cDNA product (including restriction sites; red arrow) corresponding to the carboxy terminus of dopamine D1A expressed in rat OC (NM_012546.2) (S, standards; OC, organ of Corti; B, blank).

Y2H mating and screening protocols

Y2H screening for the proteins interacting with the carboxy terminus of D1A4 for trout hair cells was performed using a Matchmaker Gold Yeast Two-hybrid System (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) as described [12,13]. The carboxy terminus of D1A4 was restriction-digested with EcoRI and BamHI enzymes, and ligated into a similarly digested pGBKT7 bait vector to produce a fusion construct with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain. The bait vectors were then used to transform Top10 bacteria. The bacteria were extracted using the Wizard miniprep and plasmids were sequenced to verify proper reading frame prior to use in the two-hybrid mating assay. No toxicity was seen from any of the bait vector products in the yeast host Y187 as determined by growth in SD/−Trp media. The D1A4 bait construct in yeast strain Y187 and a prey cDNA library in AH109 yeast cells (see below) [14] were allowed to mate in 2× YPDA (yeast peptone dextrose adenine) medium overnight at 30°C. The cells were placed on the selection medium SD/−Ade/−His/−Leu/−Trp. After 3–5 days, the larger colonies that appeared on the plates were analyzed for the prey construct by PCR. The prey cDNA from yeast clones was analyzed via PCR using the GADT7 primer, and positive strains were sequenced and prey transcripts were identified using BLAST (NCBI).

Prey library construction

A trout hair cell cDNA library was constructed from isolated hair cell layers, with trout saccular hair cell cDNA inserted into the GAL4 activation domain of pGADT7 prey vectors. A homologous recombination technique was employed in host strain AH109, with equal proportions of oligo (dT) and random hexamers directing reverse transcription of hair cell mRNA (Matchmaker Library Construction and Screening Kit; Clontech). In brief, 5 mg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed in two reactions, one containing oligo (dT) and another containing random hexamers. An equal proportion of each of the cDNAs was used to construct the prey library.

Y2H co-transformation assay for snapin and dopamine D1A4

Snapin message in trout hair cell cDNA (NP_001038613.1) was targeted in PCR using specific upstream and downstream primers (5’-GCCGAATTCCACTCAGTGAGGGAAAGC-3’ and 5’-TGCGGATCCTCATGGTTTACTGGGCGACCG-3’). These fragments were restriction-digested with EcoRI and BamHI and cloned into similarly digested pGADT7. For the yeast co-transformation assay, ~500 ng of each vector (mixture of bait plasmid constructs containing D1A4 and prey plasmid constructs containing snapin) was employed to co-transform freshly prepared AH109 competent yeast strain using the standard protocol (Clontech Yeast Two-hybrid System). The transformants were plated on nutrient-deficient selection medium (SD/−Ade/−His/−Leu/−Trp) for 3–5 days. Transformants were also selected by plating on a less stringent deficient medium (SD/−Leu/−Trp) with colonies picked and streaked on higher stringency medium (SD/−Ade/−His/−Leu/−Trp). Negative controls contained either the bait or prey, along with the corresponding empty vector selected under the same conditions as above. To further confirm the binding interaction of trout D1A4 and snapin, we reversed the bait and prey, and included negative controls.

Cloning in pRSET vectors — trout C2F domain of otoferlin

PCR degenerate primers were designed with desired restriction sites to amplify trout saccular hair cell otoferlin C2F cDNA: upstream 5’-GCCGGATCCGACCWGCMATTGAYATWTC-3’ and downstream: 5’-TGCGAATTAGATSGARATGGTTGGCAGMTC-3’, based on Danio rerio sequence (GenBank accession no. NM_001030112.2) and Oreochromis niloticus otoferlin-like sequence (XM_003449855.1), with the hair cell sequence deposited in GenBank (accession no. KF644438 corresponding to rat otoferlin aa 1728–1861). The PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes and cloned into similarly digested pRSET-A bacterial expression vectors (Invitrogen). The plasmids were prepared in Escherichia coli JM109 cells (Promega). Selected clones were sequence-verified before expression and interaction studies.

Cloning of NSF

To analyze the interaction between mammalian NSF and dopamine D1A, we PCR-amplified mouse NSF cDNA (available as a clone from Origene MC206238) as a substitute for rat NSF, given that mouse NSF and rat NSF sequences are highly identical (rat NSF NM_021748, nt 5–2239, is 95% identical with mouse NSF, accession no. NM_008740.4 with 99% aa full-sequence identity). Custom-synthesized primers containing desired restriction sites were designed for cloning into pRSET-A and glutathione S-transferase (GST)-bacterial expression vectors for PPI studies. Upstream and downstream primers for pRSET-A vector were 5’-TGCCTCGAGATGGCGGGCCGGACTATGCAA-3’ and 5’-GCCGAATTCTCAGTCAAAGTCCAGGGGACTAGC-3’, respectively. For the GST vector, upstream and downstream primers were 5’-GCGAATTCATGGCGGGCCGGACTATGCAA-3’ and 5’-GCCCTCGAGTCAGTCAAAGTCCAGGGGACTAGC-3’, respectively.

Cloning of rat D1A, snapin, C2 domains of otoferlin and adaptor-related protein complex 2, mu 1 in pRSET vectors

cDNA was amplified by PCR for rat D1A, snapin, C2F domain of otoferlin and adaptor-related protein complex 2, mu 1 (AP2mu1), using rat OC cDNA. The custom-synthesized primers containing the desired restriction sites were used to clone transcripts into pRSET-A bacterial expression vectors. PCR products were digested with restriction enzymes and cloned into similarly digested pRSET-A vectors. The plasmids were prepared in E. coli JM 109 cells (Promega). Selected clones were sequence-verified before protein expression and interaction studies. Primers used for PCR (upstream and downstream) were: rat D1A, TGCGGATCCCAGAAGGCGTTCTCAACCCTC, GCCGAATTCTCAGTCCAATATGACCGATAAGGC; rat snapin, TGCGGATCCATGGCCGCGGCTGGTTCC, GCCGAATTCTTATTTGCTTGGAGAACCAGG; otoferlin C2A, ATGGCCCTGATCGTCCACCTCAAGAC, AGGTAGCAGACCATCTGTCTC; otoferlin C2B, GATCCTGACTCAGTGTCTCTAG, CACGGCGACATCACACTTTACATAG; otoferlin C2C, ACACCCCA CAAGGCCAACGAG, GCAACTACACGCTGCTGGACGAG; otoferlin C2D, GCCAAGCTGGAACTCTACC, CCTACTGGCTGCCTTTGAGCTG; otoferlin C2E, CGCATAGTAGGCCGATTCAA, CACTTTGGTCCCCA TGGGAGA; otoferlin C2F-1 (24 kDa in pRSET), GCCGGATCCGGATGTTCCCCATATATG, GCGAATTCTT ACCAGCCTTTGACACGTTT; otoferlin C2F-2 (34 kDa in pRSET), ACGTCAGGATCCCCTTCAG AGATAGAGGATG, TGTCAGGAATTCCAGCCTTTGACACGTTTCTG; otoferlin C2F-3 (28 kDa in pRSET), CCGTTGCTCAACCCTGACAAG, GTGTCAAAGGCTGGTGGCCCCTC; AP2mu1, TGCCTCGAGGGCCG GGTGGTGATGAAG, GCCGAATTCTCAGCAGCGGGTTTCGAAA; adaptor-associated kinase 1 (AAK1), TGCGGATCCATGAAGAAGTTTTTCGACTCC, GCCCCATGGTCAAGTAGCCTGGGCCTGGGTGGG.

Trout snapin, trout D1A4, rat snapin, C2F domain of rat otoferlin, mouse/rat NSF, and rat AP2mu1 in pGEX-6P-1 for expression of GST fusion proteins

GST fusion proteins were prepared for the pull-down assay. PCR primers for trout snapin, trout D1A4, rat snapin, C2F domain of rat otoferlin, rat NSF and rat AP2mu1, delineated above, containing the desired restriction sites, were used in PCR to clone respective cDNA into the pGEX-6P-1 vector.

Expression and purification of His-tag and GST proteins

Methods for protein expression and purification used in this study have been previously described [12,13]. Briefly, the expression vectors pRSET-A and GST-pGEX-6P-1 containing the desired sequences were utilized to transform E. coli BL21 (DE3) cells. Protein expression was induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside in LB culture medium. The cultures were incubated for 4–6 h at 37°C. The bacterial cells were centrifuged and the cell pellets were lysed by ultrasonication or lysozyme with inclusion of 1× protease inhibitors and DNase (Sigma–Aldrich). Following centrifugation at 20 818 × g for 30 min, the clear supernatant was mixed with 0.5 ml of equilibrated Talon metal affinity resin (Clontech) containing 1× protease inhibitors and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The resins were washed 3–5 times with 1× wash buffer (Clontech) containing 10–20 mM imidazole, to remove nonspecific binding proteins. The bound fusion proteins were eluted by the addition of elution buffer containing 100 mM imidazole, followed by mixing and centrifugation (His TALON buffer, Clontech). The supernatant containing the fusion proteins was then exhaustively dialyzed with constant stirring against cold phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween (PBST) buffer containing 1× protease inhibitors, for 24 h at 4°C with 5–6 buffer changes. Protein was determined with the Qubit fluorescent system (Invitrogen).

Western blot analysis

Affinity-purified fusion proteins were electrophoresed on a 4–12% NuPAGE gel followed by overnight blocking with 5% nonfat milk at 4°C. Blots were incubated with anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody (Invitrogen) for 3 h at room temperature at an appropriate dilution ratio (1:5000). After three 10-min washings with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, the blots were incubated with HRP-conjugated antimouse IgG (1:10000) for 1 h at room temperature, and the proteins were detected using Western Lightning chemiluminescence (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences).

Pull-down assays

For pull-down assays, GST conjugates were mixed with hexahistidine-tagged fusion proteins in binding buffer [PBST buffer (pH 7.4), 1 × protease inhibitor mixture] for 2 h at room temperature. Glutathione-Sepharose beads (30 μl of 50% slurry) were added to the reaction mixture for 1 h at room temperature, followed by centrifugation for 2 min at 1000 × g. The beads were washed five times in the binding buffer, incubated at 70°C for 5 min in SDS gel loading dye (Invitrogen, 30 μl), and centrifuged. The supernatant was then electrophoresed on a 4–12% NuPAGE gel (Invitrogen), electroblotted to a nylon membrane, and immunodetected using an anti-Xpress antibody.

For pull-down assays of otoferlin from rat brain lysates, 500 μl of lysate containing ~500 mg of total protein was incubated with glutathione-agarose-bound GST–snapin fusion protein in a binding buffer [0.001 M HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.15 M NaCl, 0.005% P-20 and 1× protease inhibitor, Sigma] for 2 h at room temperature, and glutathione-Sepharose beads added for 1 h additional incubation, followed by centrifugation at 950 × g. The pelleted beads were washed in 1 ml of cold 1× HBS + PI five times and heat-denatured in SDS gel loading dye (Invitrogen), electrophoresed on a 4–12% NuPAGE SDS gel, and transferred by electroblotting to a PVDF membrane. The interacting otoferlin protein was detected by western analysis with anti-otoferlin antibody (sc-50159, Santa Cruz, 1:1000) and chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare).

For phosphorylation studies, rat brain tissue was pulverized at −70°C and the frozen tissue powder was transferred into ice-cold sterile tubes containing 1 ml of 1× PBS and protease inhibitors (Sigma) with or without 100 nM of calyculin-A (Cell Signaling), which inhibits the activity of protein phosphatases, PP1 and PP2A, but not acid or alkaline phosphatases or phospho-tyrosine protein phosphatases. After homogenization, the brain lysate was diluted to 5 ml with 1× PBS with the addition of 0.5% Tween-20 to solubilize the total protein. After solubilization, brain lysate containing calyculin-A was removed from the ice and incubated at room temperature for 30 min to induce threonine phosphorylation. After the calyculin-A treatment, the brain lysate was centrifuged at 20 818 × g for 20–30 min. The clear lysate was transferred to a fresh tube and stored at −20°C for PPI studies.

Pull-down assays were performed using C2F GST fusion protein and 500 ml of rat brain lysate, with or without calyculin-A, containing ~750 μg of total protein in binding buffer. The reaction tubes were incubated for 2 h at room temperature, 1 h with glutathione-Sepharose beads (as above) followed by centrifugation for 2 min at 1000 × g. The beads were washed thoroughly, five times with ice-cold 1× PBS-T containing a protease inhibitor. The pelleted beads were heat-denatured in SDS gel loading dye (Invitrogen), electrophoresed on a 4–12% NuPAGE SDS gel, and transferred by electroblotting to a PVDF membrane. Specific antibodies used to detect proteins/peptides in pull-down assays included: anti-AP2mu1 (#611350, BD biosciences), a mouse monoclonal antibody targeting phosphorylated or unphosphorylated AP2mu1 protein raised against mouse AP50mu2/1 aa 110–230 (1:1000); anti-phospho-AP2mu1 (#7399, Cell Signaling), a rabbit monoclonal antibody raised by immunizing animals with a synthetic phosphopeptide corresponding to residues surrounding phosphorylated Thr156 of human AP2M1 protein (1:1000); an anti-NSF mouse monoclonal antibody (NB21, Calbiochem), raised against recombinant human NSF (1:2000).

Surface plasmon resonance-binding analysis

The binding interactions of the carboxy terminus of trout hair cell proteins D1A4 and snapin, snapin and C2F domain of otoferlin, and rat proteins NSF, D1A, and otoferlin C2F, were measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR) at 25°C (Biacore 3000 instrument, Biacore, Piscataway, NJ) as previously described [12,13,15,16]. All proteins for SPR were synthesized as pRSET-A constructs. Binding of the mobile molecule (analyte) to the immobilized molecule (ligand) can be detected by changes in refractive index. Affinity-purified hexahistidine-tagged fusion proteins were immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip by an amine-coupling reaction [15]. Surface preparations were performed on each immobilized protein ligand with different concentrations of purified fusion proteins as an analyte. The reference surface was blocked with ethanolamine and thus contained no ligand. The response was recorded as the ligand response unit (RU) minus the reference RU. Once appropriate binding regeneration conditions were established, binding studies were performed. To determine the Ca2+ dependence of binding, actual Ca2+ levels used in the experimental solutions were obtained with inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy [12]. Negative controls for SPR included: analyte + 1 mM EGTA, buffer HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA, and buffer HBS-N alone. Mg2+ and pRSET-A negative controls are illustrated in Supplementary Figure S3.

SPR kinetic measurements were determined from interactions for ligand and analyte over a range of analyte concentrations, typically 0–320 nM, and also for the reversal of ligand and analyte. After each reaction, the chip was regenerated with HBS-N buffer. Kinetic values were ascertained using BIAevaluation software 4.1 (Biacore) with a 1:1 Langmuir binding model selected for ‘global’ calculations across analyte concentrations. In addition, kinetic constants were calculated with BIAevaluation software 4.1 (Biacore) for individual plots, each representing a different concentration of analyte.

AAK1 phosphorylation of AP2mu1

It has been shown that AAK1 specifically phosphorylates threonine 156 of the μ-subunit of adapter protein-2 (AP2) complexes. In the present study, we used AAK1 to phosphorylate AP2mu1 in an in vitro kinase assay. We synthesized PCR primers with restriction sites (TGCGGATCCATGAAGAAGTTTTTCGACTCC, upstream, and GCCCCATGGTCAAGTAGCCTGGGCCTGGGTGGG, downstream) to amplify from rat OC partial cDNA for AAK1 (corresponding to aa 1–460 of 963, GenBank NP_001166921). Amino acids 1–460 of AAK1 encompass protein kinase functional sites, catalytic domain, active site, ATP-binding site, substrate-binding site, activation loop, and a serine/threonine domain (aa 1–312). The PCR product was digested with restriction enzymes and cloned into similarly digested pRSET-A bacterial expression vectors (Invitrogen). The plasmids were prepared in E. coli JM109 cells (Stratagene). Selected clones were sequence-verified before expression and phosphorylation studies.

In vitro kinase assays

The in vitro phosphorylation of AP2mu1 recombinant His-tag fusion protein was carried out with AAK1 as synthesized above. Briefly, 5 μg/reaction of AP2mu1 fusion protein and 200 mM ATP were mixed with kinase buffer [25 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 2 mM DTT, and 5 mM β-glycerophosphate] and a protease inhibitor. The kinase reaction was started with the addition of 1 μg AAK1 and carried out at 30°C for 20 min. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 10 μl of 10 mM EDTA and the reaction product was stored at −20°C. The phosphorylated form of AP2mu1 was used for PPI studies with the C2F domain of otoferlin.

Immunohistochemical protocols

Details for immunochemical studies are given in Drescher et al. [2,17]. Briefly, dopamine D1 receptor was detected in the cochlea of the adult rat (2 months) with a rabbit anti-dopamine receptor D1A affinity-purified polyclonal antibody (AB1765P, Chemicon, Temecula, CA; 1:25) raised against a 13 amino acid sequence (aa 403–415) from rat D1A, mouse monoclonal (MAB5290, Chemicon) targeting recombinant rat D1A receptor carboxy terminus and an affinity-purified goat polyclonal antibody for dopamine D1DR (sc-31478, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:200), which would detect dopamine D1A and dopamine D1B receptor from rat and mouse. Snapin was detected with sc-34946 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), an affinity-purified goat polyclonal antibody raised against a peptide that mapped within an internal region of snapin of human origin with 94% identity with trout saccular hair cell snapin.

Immunoreactivity, detected with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) or fluorescence, was visualized as previously described [17]. Immunostaining with DAB was examined with a Leitz Diaplan microscope (Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany), photographed with an Olympus OM-4T camera, and the negatives were digitized at 300–600 dpi.

Co-immunoprecipitation

For co-immunoprecipitation analyses, rat brain tissue was solubilized in calcium-free HBS buffer containing 0.1% Tween-20 and protease inhibitor cocktails (Promega) by brief sonication on ice. The supernatant from cold centrifugation at 20 900 × g for 12 min was diluted to a concentration of 1 mg/ml with calcium-free HBS buffer containing a protease inhibitor. The diluted lysate was pretreated with protein A agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and with normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz, sc-2027) for 1 h at 4°C to remove the proteins that bind nonspecifically to agarose and immunoglobulins. The reaction mixtures were centrifuged at 950 × g for 5 min at 4°C, and the pretreated supernatants were separated and the beads were discarded. The pretreated lysate containing ~500 μg of total protein was incubated with 5 μg of rabbit anti-rat D1A polyclonal antibody (AB1765P, Chemicon; 1:200 for western blot) with 100 μM Ca2+ or 1 mM EGTA in HBS buffer overnight at 4°C. For a negative control, the rat brain lysate was incubated with normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz sc-2027, 1:1000). After overnight incubation, 25 μl of fresh protein A-agarose beads were added, and incubation was continued for another 1 h at 4°C followed by centrifugation at 950 × g for 5 min and removal of the supernatant. Pellets (containing beads) were then thoroughly washed seven times with 1 ml of ice-cold PBS-T containing a protease inhibitor. After washing, 30 μl of 1× gel loading dye was added to the final pellet and boiled 10 min prior to electrophoresis. After centrifugation for 5 min at 20 900 × g, the supernatant was collected and loaded on a NuPAGE SDS gel (Invitrogen). The PVDF membrane blots of the gel were blocked with 1% nonfat milk in PBST and incubated with custom rabbit polyclonal antibody against otoferlin 1:6000 [18] and mouse monoclonal antibody against NSF 1:2000 (NB21, Calbiochem). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies [Santa Cruz Biotechnology, donkey antirabbit IgG (sc-2313) and donkey anti-mouse IgG (sc-2314), respectively] were diluted 1:10 000 in blocking solutions corresponding to sera of the species in which the secondary antibody was raised. ECL reagents were used for western detection (Pierce Chemical).

Dopamine D1A agonist-driven expression of phosphorylated AP2mu1

A microdissected OC surface preparation from the adult rat was incubated with dopamine D1A agonist SKF 81297 hydrobromide (Tocris cat. no. 1447) at 10 mM in physiological saline (5 min, RT), followed by fixation (4% paraformaldehyde, 1 h, 0°C). Immunofluorescence localization (780 Zeiss confocal, ZEN 2 Z-stack analysis) was carried out for phosphorylated AP2mu1 (monoclonal rabbit primary antibody, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, 1:25), CtBP2 (C-terminal-binding protein 2; goat polyclonal primary antibody, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:200; mouse monoclonal IgG1 raised against CtBP2 aa 361–445, BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA), and actin (Alexafluor 405-conjugated phalloidin, AAT Bioquest, Sunnyvale, CA, cat. no. 23111, 1:30 000). Blocking was accomplished with 2% donkey serum (overnight at 4°C). Secondary antibodies included Alexafluor-568 donkey anti-rabbit IgG and Alexafluor-488 donkey anti-goat IgG (both at 1:2000, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The base of cochlear inner hair cells (IHCs) was identified from specific expression of CtBP2, the hair cell ribbon synapse marker ribeye, in a surface preparation 8 mm in the z-dimension from the position of IHC stereocilia.

Results

Trout saccular hair cell dopamine D1A4 C-terminus directly binds SNARE-associated protein snapin by Y2H analysis

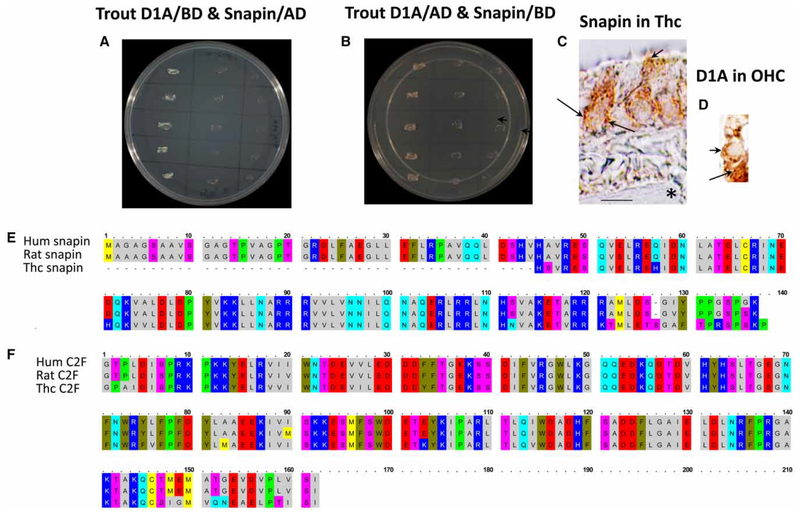

The trout saccular hair cell dopamine D1A4 carboxy terminus (Figure 1A, GenBank accession no. EU371401) was inserted into the pGBKT7 bait vector and mated with trout saccular hair cell cDNA in pGADT7 prey vector from a yeast cDNA prey library [12]. Overall, 76 prey clones were sequenced for the D1A4 carboxy terminus bait, and snapin, a soluble protein interacting with t-SNARE protein SNAP-25, was identified as strongly interacting with D1A4 in quadruple drop-out media. The interaction was attributable to the C-terminal two-thirds of snapin (Figure 2E, aa 45–138), which in the trout saccular hair cell (GenBank Accession No. KF644439) had 100% aa identity with snapin of Salmo salar (GenBank accession no. NP_001139828), and 86 and 87% aa identity with human and rat snapin, respectively (Figure 2E), indicating high evolutionary conservation. Confirmation of PPI between hair cell dopamine D1A4 and snapin was obtained with Y2H co-transformation protocols, with both configurations of the respective proteins in bait and prey and corresponding empty vector negative controls (Figures 2A,B). The high identity of trout hair cell snapin to mammalian sequence (86–87%) enabled immunohistochemical localization with antibodies targeting mammalian snapin. As predicted by protein interactions for a highly purified hair cell layer, snapin was immunolocalized to saccular hair cells within the sensory epithelia, appearing as a hair cell marker with immunoreactivity displayed throughout the hair cell cytoplasm, as expected for a soluble protein (Figure 2C). Snapin was not found in supporting cells nor in afferent or efferent innervation. Snapin immunoreactivity was localized to basolateral aspects of the saccular hair cell, sites of efferent input and afferent exocytosis (Figure 2C, long arrows). An interaction between dopamine D1A4 and snapin at these basolateral sites could be targeted in dopaminergic efferent modulation of saccular hair cell exocytosis. Curiously, snapin immunoreactivity was also concentrated at apical sites, a subcuticular plate region of teleost hair cells (Figure 2C, short arrow), similarly to the immune-localization of dopamine D1A protein in mammalian vestibular hair cells ([2], Figure 10, d1). Molecular interactions of dopamine D1A and snapin at this subcuticular plate site could affect trafficking of proteins both apically to hair cell stereocilia and basally in regulation of hair cell exocytosis.

Figure 2. Dopamine D1A4 and snapin yeast co-transformation and protein localization.

(A) Co-transformation of trout HC dopamine D1A4 carboxy terminus in BD vector (Clontech) and snapin in AD vector (Clontech) in quadruple drop-out medium with antibiotics. First lane, interaction of trout HC D1A4 as bait and snapin-like protein as prey (multiple streakings), the latter originally identified as a binding partner for D1A4 carboxyl terminus in Y2H mating protocols. Second lane, negative control with D1A4-C as bait and empty prey vector. Third lane, negative control with empty bait vector and snapin prey sequence. (B) Reversal of bait and prey, snapin in BD vector, and D1A4-C in AD vector, in yeast co-transformation. First lane, snapin-like protein as bait and D1A4-C as prey. Second lane, negative control with snapin as bait and empty prey vector. Third lane, negative control with empty bait vector and D1A4-C prey sequence. (C) Snapin immunolocalization to trout saccular hair cells (thcs) detected with DAB. Snapin was specifically expressed in saccular hair cells, as would occur for a hair cell marker protein. Snapin immunoreactivity was observed close to the hair cell basolateral membrane (long arrows) and was concentrated at apical subcuticular plate sites (short arrow). Note the large unreactive afferent nerve passing through the connective tissue layer (asterisk), across the basal lamina, and into the sensory epithelium adjacent to unreactive supporting cells. Scale bar = 10 μm. (D) Dopamine D1A immunolocalization in cochlear outer hair cells of the adult rat. Immunoreactivity to D1A was localized to the base of a first row outer hair cell (short arrow), similar in position to dopaminergic efferent input. The Deiters’ cells were immunopositive (long arrow), observed at the level of the cell body and in phalangeal extensions wrapping around the cochlear outer hair cell. (E) Amino acid alignment of human snapin (NP_036569.1), rat snapin (NP_001164047.1), and thc snapin (AHB38897.1). (F) Alignment of aa for otoferlin C2F domains in human (NP_919224.1), rat (NP_001263649.1), and thc (AHB38896.1).

GST pull-down assays confirm that the carboxyl terminus of dopamine D1A4 from teleost saccular hair cells binds snapin and snapin, in turn, binds otoferlin C2F

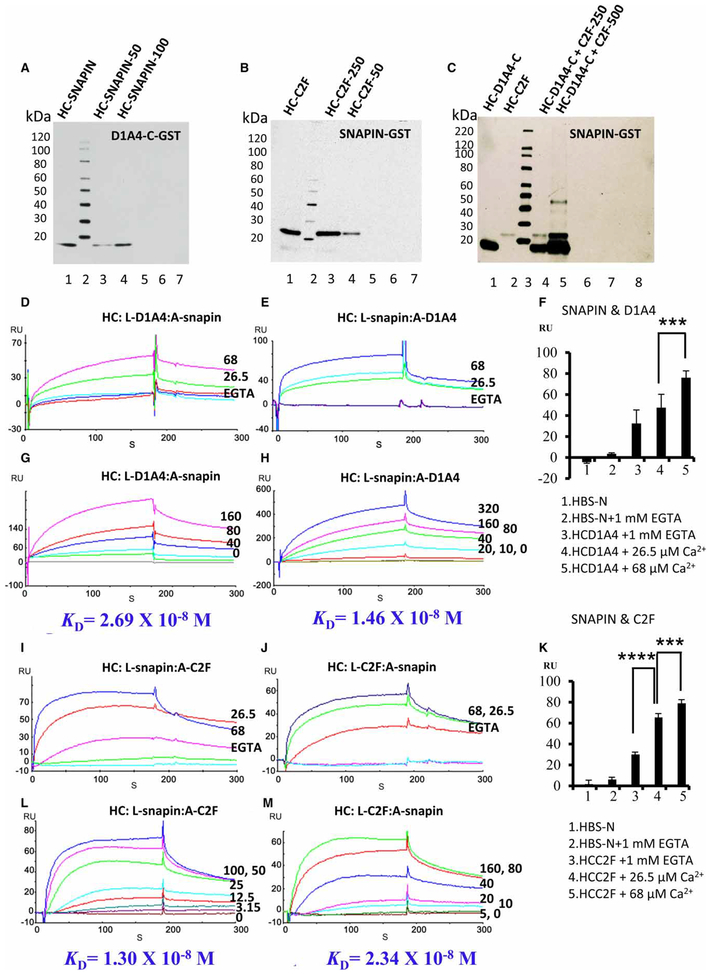

Pull-down assays were carried out with purified trout saccular hair cell proteins prepared from pRSET-A constructs. The GST-labeled intracellular carboxyl terminus of dopamine D1A4 (Supplementary Figure S1A, lane 2, ~36 kDa) pulled down the fusion protein of snapin prepared from a pRSET-A construct at ~14 kDa (Figure 3A, ~50 and 100 ng, lanes 3 and 4, respectively, identified with anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody compared with positive control, lane 1). Negative controls included trout snapin incubated with either GST-bacterial lysate or with Sepharose beads under the same conditions as for the experimental sample.

Figure 3. Pull-down assays and SPR of dopamine D1A4 with snapin and snapin with otoferlin C2F in the thc.

(A) Interaction of trout hair cell (HC) D1A4 and snapin by pull-down analysis. Lane 1, purified trout HC snapin in pRSET-A fusion protein used in the present study; lane 2, protein standards (S); lane 3, PPI of trout snapin fusion protein (~50 ng) with GST–trout D1A4-C cleared lysate, pulled down with glutathione-Sepharose, and detected with anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody; lane 4, trout snapin fusion protein (~100 ng) with GST–trout D1A4-C lysate; lane 5, binding of trout snapin fusion protein (~100 ng) with GST–trout D1A4-C lysate and no beads, as a negative control; lane 6, trout snapin (~100 ng) incubated with GST-bacterial lysate as a negative control; lane 7, trout snapin fusion protein (~100 ng) mixed with Sepharose beads under the same conditions as above, representing another negative control. (B) Pull-down of C2F domain of trout saccular hair cell (HC) otoferlin with GST–trout HC snapin fusion protein. Lane 1, purified trout HC C2F fusion product used in this experiment, ~24 kDa; lane 2, protein standards; lane 3, interaction of trout HC C2F fusion protein (~250 ng) with GST–trout HC snapin cleared lysate, pulled down with glutathione-Sepharose, and detected with anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody; lane 4, ~50 ng of trout HC C2F fusion protein with GST–trout HC snapin lysate; lane 5, trout HC C2F fusion protein (~250 ng) with GST–trout HC snapin lysate and no beads as a negative control; lane 6, trout HC C2F (~250 ng) incubated with GST-bacterial lysate (no insert) as a negative control; lane 7, trout HC C2F fusion protein (~250 ng) mixed with Sepharose beads under the same conditions as above, representing another negative control. (C) Competitive pull-down assay for trout HC snapin with trout HC D1A4 and C2F domain of otoferlin. Lane 1, purified HC D1A4 in pRSET fusion protein at ~14 kDa; lane 2, purified trout HC C2F in pRSET fusion protein at ~24 kDa; lane 3, protein standards; lane 4, affinity-purified trout D1A4 and C2F fusion proteins (250 ng each) mixed with GST–trout snapin cleared lysate. The pull-down assay revealed that D1A4 and C2F were capable of binding snapin at the same time without steric hindrance, further confirmed in lane 5 with ~500 ng of affinity-purified D1A4 and C2F fusion proteins with detection with anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody. We validated the results with three different kinds of negative control reactions: lane 6, ~500 ng of both D1A4 and C2F mixed with GST–snapin and no beads; lane 7, ~500 ng of both the proteins with GST-bacterial lysate with unconjugated Sepharose beads, i.e. without snapin; lane 8, ~500 ng of both D1A and C2F fusion proteins with Sepharose beads alone under the same conditions. (D) Ca2+ dependence of the interaction of dopamine D1A4 as a ligand (L) with snapin as an analyte (A) (at 100 nM, dissolved in HBS-N buffer). RUs are indicated for binding with snapin at 68 μM Ca2+ (magenta), 26.5 μM Ca2+ (green), and 1 mM EGTA (cyan), compared with RU for HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA alone (blue) or HBS-N buffer alone (red). (E) Reversal of ligand and analyte: with snapin as a ligand and D1A4 as an analyte (100 nM), responses were obtained at 68 μM Ca2+ (blue), 26.5 μM Ca2+ (cyan), and 1 mM EGTA (green), compared with the response for HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA alone (blue) or HBS-N buffer alone (magenta). (F) Quantitative analysis of PPI between snapin and dopamine D1A4 as dependent on Ca2+ by SPR [15,16] with mean ± standard deviation, n = 3. ***P = 0.0095 for 26.5 vs. 68 μM Ca2+ for the unpaired, two-tailed t-test. (G) Kinetic series: purified D1A4 was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip, and snapin was diluted in a series of concentrations in HBS-N buffer run at 68 μM Ca2+; 0 nM (gray), 10 nM (green), 20 nM (cyan), 40 nM (blue), 80 nM (red), and 160 nM (magenta). (H) Kinetic series for the reversal of ligand and analyte: snapin as a ligand and D1A4 as an analyte at 68 μM Ca2+ in HBS-N buffer; D1A4 at 0 nM (gray), 10 nM (yellow), 20 nM (red), 40 nM (cyan), 80 nM (green), 160 nM (magenta), and 320 nM (blue). (I) Ca2+ dependence of the interaction of trout HC snapin as a ligand with C2F as an analyte (100 nM dissolved in HBS-N buffer); 68 μM Ca2+ (blue), 26.5 μM Ca2+ (red), and 1 mM EGTA (magenta), compared with the response for HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA alone (green) or HBS-N buffer alone (cyan). (J) Reversal of ligand and analyte: Ca2+ dependence of binding between C2F as a ligand and snapin as an analyte(100 nM dissolved in HBS-N buffer); 68 μM Ca2+ (blue), 26.5 μM Ca2+ (green), and 1 mM EGTA (red), compared with the response for HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA alone (magenta) or HBS-N buffer alone (cyan). (K) Quantitative analysis of PPI between snapin and otoferlin C2F as dependent on Ca2+ by SPR [15,16] with mean ± standard deviation, n = 3. ****P = 0.0001 for 26.5 vs. 68 μM Ca2+ for the unpaired, two-tailed t-test; ***P = 0.008 for 26.5 vs. 68 μM Ca2+ for the unpaired two-tailed t-test.(L) Quantitative characterization of binding between snapin and C2F in a kinetic study. Purified snapin was immobilized as a ligand on a CM5 sensor chip, and C2F analyte was diluted in a series of concentrations with HBS-N buffer containing 68 μM Ca2+; 0 nM (red), 2.5 nM (magenta), 5 nM (cyan), 10 nM (red), 20 nM (cyan), 40 nM (green), 80 nM (magenta), and 160 nM (blue).(M) A kinetic series was performed for the reversal of C2F as a ligand and snapin as an analyte at 68 μM Ca2+ in HBS-N buffer; 0 nM (red), 5 nM (green), 10 nM (cyan), 20 nM (magenta), 40 nM (blue), 80 nM (red), and 160 nM (green).

Snapin (GST construct ~37 kDa in Supplementary Figure S1B, lane 2), in turn, bound to the C2F domain of presumptive synaptic protein otoferlin at ~24 kDa (Figure 3B, lanes 3 and 4, 250 and 50 ng, respectively, compared with positive control, lane 1). Competitive pull-downs with D1A4 and C2F in pRSET-A constructs and snapin in GST indicated that the interactions between the three proteins could occur together [Figure 3C, lanes 4 (250 ng each) and 5 (500 ng each) for both D1A4 at ~14 kDa and C2F at ~24 kDa, compared with standards, in lanes 1 and 2, respectively].

SPR characterization of the interaction of dopamine D1A4 with snapin and snapin with otoferlin C2F for the trout saccular hair cell

Interactions of the carboxyl terminus of D1A4 with snapin were also examined with SPR, utilizing affinity-purified pRSET-A fusion protein of snapin as an analyte (A) and affinity-purified D1A4 pRSET-A fusion protein immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip as a ligand (L) [15,16]. Snapin (100 nM) directly interacted with D1A4 in SPR analysis at 26.5 μM Ca2+ (Figure 3D, green), a response that was enhanced at 68 μM Ca2+ (Figure 3D, magenta) compared with HBS-N plus 1 mM EGTA (blue) and HBS-N (red) alone used as negative controls. Similar increases in response were observed upon elevation of Ca2+ when the ligand and analyte were reversed (Figure 3E,F).

Binding constants for a kinetic series, 0–160 nM snapin (68 μM free Ca2+; Figure 3G), yielded an overall KD of 2.69 × 10−8 M (Table 1) according to the global 1:1 Langmuir binding model (BIAevaluation 4.1 software, Biacore). The reverse (snapin as a ligand and D1A4 as an analyte) yielded a KD of 1.46 × 10−8 M (Figure 3H). The results were normalized by subtracting the SPR response (RU) for buffer alone and, in experiments examining calcium dependency, the Ca2+ concentrations for individual SPR analyses were altered randomly. There was no binding to the reference cell surface, which was blocked by ethanolamine. Thus, these results indicate positive calcium-dependent, high-affinity binding of the carboxyl terminus of trout saccular D1A4 to snapin.

Table 1.

Kinetic series for PPIs by SPR

| Binding partners | ka (M−1 s−1) | kd (s−1) | KD (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) D1A4 + snapin | 2.91 × 105* (2.03 ± 1.04 × 105) | 7.84 ×10−3* (3.14 ± 0.14 × 10−3) | 2.69 × 10−8 |

| (2) Snapin + D1A4 | 1.19 × 105 (1.12 ± 0.24 × 105) | 1.74 × 10−3 (1.75 ± 0.09 × 10−3) | 1.46 × 10−8 |

| (3) Snapin + C2F | 3.12 × 105 (6.35 ± 2.29 × 105) | 4.07 × 10−3 (4.00 ± 0.52 × 10−3) | 1.30 × 10−8 |

| (4) C2F + snapin | 1.49 ×105 (5.72 ± 1.57 ×105) | 3.48 × 10−3 (3.04 ± 0.18 × 10−3) | 2.34 × 10−8 |

| (5) NSF+D1A | 2.27 ×105 (1.55 ±0.78 ×105) | 2.74 ×10−3 (4.95 ±2.51 ×10−3) | 1.21 × 10−8 |

| (6) NSF + C2F | 3.19 × 105 (2.10 ± 0.77 × 105)*** | 7.30 × 10−4 (4.99 ±0.73 ×10−3) | 2.29 × 10−9 |

| (7) AP2mu1 + C2F | 2.12 × 104 (3.02 ± 0.83 × 104)*** | 2.73 × 10−3 (2.17 ± 1.54 × 10−3) | 1.29 × 10−7 |

Kinetic constants were determined for interaction between (1) trout saccular hair cell (thc) dopamine D1A4 and snapin, (2) thc snapin and D1A4, (3) thc snapin and the C2F domain of otoferlin, (4) thc C2F and snapin, (5) rat OC NSF and D1A, (6) rat OC NSF and C2F, and (7) rat OC AP2mu1 and C2F. The first protein in each pair served as the ligand, individually immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip, and the second protein was the analyte. The affinity-purified analyte was presented in a series of different concentrations in the SPR reaction with a blank flow cell blocked with ethanolamine serving as a reference standard. Rate constants for association and dissociation signals for each interaction were obtained from the original SPR plots by the use of the BIAevaluation 4.1 software. A Langmuir model was used in curve fitting, and the overall best-fitting model value across analyte concentrations or ‘global analysis’ is presented as the first number* entered for ka and kd. In addition, the means ± SD are presented for a set of ka values obtained from curve fitting of single responses to different concentrations of analyte (n = 3–6). Listed KD = kd/ka for global values.

P < 0.02, difference of mean, unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test for ka (mean ± SD) characterizing NSF + C2F vs. AP2mu1 + C2F interactions, n = 3.

Confirming pull-down assays, snapin expressed by trout saccular hair cells was also found to bind to otoferlin C2F (GenBank accession no. KF644438) [11] by SPR. Affinity-purified snapin was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip as a ligand and the C2F domain of otoferlin (100 nM) served as an analyte. This interaction occurred in the absence of Ca2+ (1 mM EGTA, Figure 3I, magenta) and was enhanced as [Ca2+] was elevated to 26.5 and 68 mM (Figure 3I, red and blue lines, respectively, and Figure 3K), indicating that Ca2+ positively regulates the interaction. Similar results were produced when the ligand and analyte were reversed (Figure 3J). Kinetic analysis for snapin as the ligand interacting with C2F domain as the analyte (1.5–100 nM, 68 mM Ca2+, Figure 3L) yielded a KD of 1.3 × 10−8 M (Table 1) and for the reversal of ligand and analyte (0–160 nM, 68 μM Ca2+, Figure 3M) yielded a KD of 2.34 × 10−8 M.

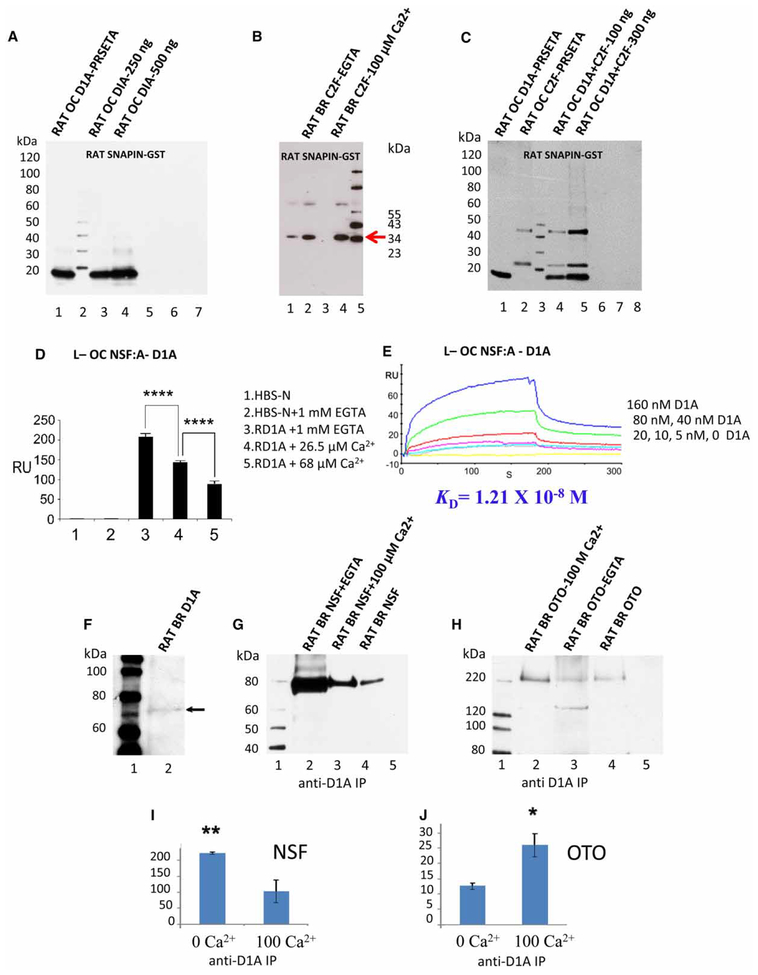

The carboxy terminus of dopamine D1A from rat OC also interacts with snapin by GST pull-down assays

The interactions described for teleost saccular hair cells also occur for mammalian proteins found in hair cell-containing OC isolated from the adult rat cochlea. Whether D1A mRNA is actually expressed in the mammalian OC had not been ascertained previously, although the transcript was identified in a lateral wall microdissected cochlear subfraction from the 18-day-old rat [19]. In the present investigation, D1A-specific PCR primers selectively amplified D1A cDNA from an OC subfraction of rat cochlea (adult) as a single band at 286 bp (including restriction sites, Figure 1B), with sequence verification. The purified fusion proteins of rat OC D1A carboxy terminus in pRSET-A and snapin in GST yielded the appropriate molecular mass upon western blot analysis of ~14 kDa (Figure 4A, lane 1) for D1A, detected with anti-Xpress antibody, and of ~41 kDa (Supplementary Figure S1C, lane 2) for snapin, detected with anti-GST antibody, respectively. Binding between rat OC proteins, D1A carboxy terminus, at 250 and 500 ng, and snapin in the GST construct was observed by the pull-down assay (Figure 4A, lanes 3 and 4, respectively). Negative controls included rat D1A incubated with either GST-bacterial lysate or unconjugated Sepharose beads carried out under similar conditions as for the experimental samples.

Figure 4. Interactions of rat D1A with snapin and snapin with otoferlin, positively dependent on Ca2+, and interaction of rat D1A with NSF, inhibited by Ca2+.

(A) Interactions between rat OC D1A and snapin by pull-down analysis. Lane 1, affinity-purified rat OC D1A in pRSET-A fusion protein at ~14 kDa; lane 2, protein standards; lane 3, binding interaction of rat OC D1A fusion protein (~250 ng) with GST–rat snapin cleared lysate, pulled down with glutathione-Sepharose, and detected with anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody; lane 4, rat D1A fusion protein (~500 ng) with GST–rat snapin cleared lysate; lane 5, binding of rat D1A fusion protein (~250 ng) with GST–rat snapin lysate and no beads as a negative control; lane 6, rat D1A (~250 ng) incubated with GST-bacterial lysate, negative control; lane 7, rat D1A fusion protein (~250 ng) mixed with Sepharose beads under the same conditions as above, representing another negative control. (B) Interaction of rat brain (BR) GST–snapin with otoferlin C2F domain. A hexahistidine–C2F fusion protein was produced from BR otoferlin cDNA amplified by PCR with C2F-2 primers (34 kDa), purified [14], and incubated with glutathione-Sepharose beads and GST–snapin fusion protein (from PCR amplification of rat brain snapin cDNA) in binding buffer (see Experimental). The interacting fusion protein was eluted with heat denaturation and detected on an SDS–PAGE gel blot with a mouse monoclonal anti-Xpress antibody (Invitrogen). Lane 1, GST negative control; lane 2, C2F(34 kDa, red arrow) with 1 mM EGTA; lane 3, only beads; lane 4, C2F with 100 μM added calcium; lane 5, molecular mass standards. (C) Competitive pull-down assays determining the interaction of rat OC D1A and otoferlin C2F with snapin in GST vector. Lane 1, affinity-purified rat OC D1A in pRSET fusion protein at ~14 kDa; lane 2, purified OC C2F domain of otoferlin in pRSET fusion proteins at ~24 kDa; lane 3, protein standards; lane 4, affinity-purified rat D1A and C2F fusion proteins, ~100 ng of each, were mixed with GST–OC snapin cleared lysate. The pull-down products detected with anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody showed that snapin was capable of binding to both D1A and C2F at the same time; lane 5, pull-down with ~300 ngof affinity-purified rat D1A and C2F fusion proteins, again indicating that both the interactions of D1A with snapin and C2F with snapin can occur together without steric hindrance, forming a three-protein complex. Negative control reactions included:lane 6, ~300 ng of both rat D1A and C2F were mixed with GST–rat snapin with no beads; lane 7, in another negative control ~300 ng of both the proteins were mixed with GST-bacterial lysate; lane 8, in a third negative control, ~300 ng of both D1A and C2F fusion proteins were mixed with Sepharose beads alone under the same conditions. (D) Interaction of D1A as an analyte (A) and affinity-purified rat OC NSF fusion protein as a ligand (L). Maximum responses are shown for the interaction of analyte D1A at 200 nM with ligand NSF at different concentrations of Ca2+. No interactions occurred for buffer alone (bar 1) or buffer + 1 mM EGTA (bar 2). The largest response for analyte was observed at 1 mM EGTA (bar 3) with a lesser response at26.5 μM Ca2+ (bar 4) and least at 68 μM Ca2+ (bar 5), overall indicating an inverse relationship between binding and [Ca2+]. The mean ± SD are presented (n = 3). ****P < 0.0001 for RU bar 3 vs. bar 4, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test; ****P < 0.0001 for bar 4 vs. bar 5, unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test. (E) A kinetic series at 26.5 μM Ca2+ for binding between NSF (ligand) and D1A (analyte) at 160 nM (blue), 80 nM (green), 40 nM (red), 20 nM (magenta), 10 nM (cyan), 5 nM (gray), and 0 nM (yellow). (F) Western blot for full-length D1A from rat brain lysate detected with an affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a peptide in the carboxyl terminus of D1A of rat origin (AB1765P, Millipore). Lane 1, Magic XP Western standards; lane 2, full-length D1A at 75 kDa (arrow). (G) Immunoprecipitation of NSF from rat brain lysate by antidopamine D1A antibody. Lane 1, Magic XP Western standards. Lane 2, anti-dopamine D1A immunoprecipitation of NSF (~80 kDa) from rat brain lysate in the absence of calcium (i.e. 1 mM EGTA) detected by specific anti-NSF antibody. Lane 3, antidopamine D1A immunoprecipitation of NSF at 100 μM Ca2+. Lane 4, western for full-length NSF in rat brain lysate. Lane 5, negative control using rabbit normal IgG immunoprecipitation with 1 mM EGTA. The blot is representative of at least three separate experiments. (H) Immunoprecipitation of full-length otoferlin (220 kDa) from rat brain lysate with dopamine D1A antibody (Millipore) with and without added calcium. Lane 1, western standards; lane 2, anti-D1A immunoprecipitation of otoferlin (OTO) (~220 kDa) at 100 μM Ca2+, detected with custom antiotoferlin antibody raised in rabbit. Lane 3, immunoprecipitation in the absence of calcium (i.e. 1 mM EGTA). A second smaller protein, ~140 kDa, in addition, was immunopositive with the otoferlin antibody for lanes 2 and 3. Lane 4, western blot of full-length otoferlin in rat brain lysate detected with anti-otoferlin antibody at ~220 kDa. Lane 5, negative control, rabbit normal IgG immunoprecipitation at 100 μM Ca2+. All experiments were repeated three times, and blots are representative of at least three separate experiments. (I) Quantitative analysis of immunoprecipitation by anti-D1A antibody of NSF illustrated in G. Band intensities were analyzed and averaged using the software Image J. The mean ± SE (error bars) (n = 3) were plotted using Microsoft Excel. Bar 1, immunoprecipitation of NSF at 0 μM Ca2+; bar 2, immunoprecipitation of otoferlin at 100 μM Ca2+. **P =0.0245, unpaired, two-tailed t-test for bar 1 vs. bar 2. (J) Quantitative analysis using the software Image J for immunoprecipitation illustrated in H (mean ± SE), n = 3. Bar 1, immunoprecipitation of otoferlin at 0 μM Ca2+; bar 2, immunoprecipitation of otoferlin at 100 μM Ca2+; bar 2 vs. bar 1, *P = 0.058, the unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

In the next step of the synaptic pathway, GST–snapin was able to pull down otoferlin from rat brain lysate (100 μM Ca2+), detected with goat anti-human otoferlin primary antibody (Santa Cruz sc 50159) that crosses to rat otoferlin (Supplementary Figure S2A, arrow points to otoferlin positive band >132 kDa, lane 2; the estimated molecular mass of full-length otoferlin is 227 kDa). (Note the reduced pull-down with EGTA, lane 3.) The interaction for rat brain proteins was replicated with a pull-down of hexahistidine–C2F fusion protein derived from PCR-amplified brain C2F cDNA and GST–snapin fusion protein (Figure 4B). The C2F domain was detected with the mouse monoclonal anti-Xpress antibody (Invitrogen) at 34 kDa for C2F-2 primers. The interaction occurred in the absence of Ca2+ (1 mM EGTA, Figure 4B, lane 2) and was enhanced by Ca2+ at 100 μM (Figure 4B, lane 4, red arrow). Competitive pull-down assays with OC proteins dopamine D1A and otoferlin C2F and snapin (with no added Ca2+) indicated that these interactions can occur simultaneously. The three fusion proteins bind together without apparent steric hindrance (Figure 4C, compare lane 4 with 100 ng each of D1A and C2F and lane 5 with 300 ng each of D1A and C2F with standards for dopamine D1A, lane 1 at ~14 kDa, and otoferlin C2F amplified with C2F-1 primers, lane 2 at ~24 kDa).

OC dopamine D1A interacts with NSF, a PPI which is inhibited by Ca2+

NSF is a hexameric ATPase thought to have a role in the disassembly of cis-SNARE complexes prior to synaptic complex fusion of trans-SNARE complexes with the presynaptic membrane [20]. NSF is known to be immuno-precipitated with dopamine D1 receptor from rat hippocampal tissues [21]. In the present study, we obtained evidence, in addition, for direct interaction between dopamine D1A and NSF, and characterized its Ca2+ dependency and kinetic constants by SPR analysis. For SPR, we immobilized affinity-purified NSF on a CM-5 sensor chip as the ligand (see Experimental). In the SPR analysis, the NSF–D1A interaction was maximized in the absence of free Ca2+ (Figure 4D, bar 3). At 26.5 μM Ca2+, there was ~30% reduction in binding (Figure 4D, bar 4), and almost a 50% decrease in binding when the free Ca2+ was elevated to 68 μM (Figure 4D, bar 5; P < 0.0001 for bar 3 vs. bar 4 and bar 4 vs. bar 5; n = 3, unpaired two-tailed t-test). No binding was observed for negative controls (HBS-N plus EGTA, Figure 4D, bar 2) or HBS-N buffer alone (Figure 4D, bar 1). Thus, the current study indicates that the carboxy terminus of D1A directly interacts with NSF, an interaction that is inversely dependent on free [Ca2+], in contrast with the interaction between D1A with snapin, and snapin with otoferlin, an alternate protein complex, results consistent with a role for Ca2+ as one molecular switch. A SPR kinetic series indicated a KD of 1.21 × 10−8 M for the interaction of OC NSF as a ligand and D1A at 0–160 nM as an analyte (26.5 μM Ca2+), calculated according to BIAevaluation 4.1 software (GE Healthcare; Figure 4E).

Co-immunoprecipitation of dopamine D1A with either NSF or otoferlin follows the dependency on Ca2+ demonstrated by SPR

Co-precipitation of NSF with dopamine D1A from rat brain lysate was inversely related to Ca2+ (Figure 4G, lane 2 at 1 mM EGTA compared with lane 3 at 100 μM Ca2+; Figure 4I, bar 1 vs. bar 2, P = 0.0245, two-tailed t-test). In contrast, in the same experiments, the positive dependency on Ca2+ for the dopamine D1A interaction with snapin and snapin with otoferlin C2F domain observed in SPR extended to co-immunoprecipitation of full-length proteins. More full-length otoferlin was co-immunoprecipitated with D1A at 100 μM Ca2+ (Figure 4H, lane 2) than at 1 mM EGTA (Figure 4H, lane 3; Figure 4J, bar 2 vs. bar 1, P = 0.058, two-tailed t-test), again suggesting that Ca2+ can act as a molecular switch between these two sets of interactions. Furthermore, the coupling of direct interactions, positively dependent on Ca2+, between D1A with snapin and snapin with otoferlin, is implied in order for an antibody to D1A to immunoprecipitate otoferlin via the intermediary, snapin.

Selective interaction of rat OC otoferlin C2 domains with NSF and AP2mu1 by pull-down assays

Both NSF and AP2 play a major role in receptor targeting, membrane expression, internalization, clustering, and in the modulation of receptor activity and activation of signaling pathways [22–24]. Duncker et al. [25] carried out immunity affinity capture with an otoferlin-specific antibody and identified, with tandem MS immuno-precipitation, a protein complex from mouse cochlea that includes both NSF and the clathrin AP2 subunits α (AP2A2), β (AP2B1), and μ (AP2M1). Supra- and sub-nuclear co-localization of AP2α (α adaptin) and otoferlin proteins was observed. However, whether otoferlin directly interacts with the individual subunits of AP2 and NSF has not been previously determined. One cargo motif utilized by AP2mu1 in endocytosis is YXXΦ, where X refers to a polar residue and Φ is a bulky hydrophobic residue L/I/M/V/F [26]. In the present investigation, pull-down assays indicated that the individual rat OC otoferlin domains C2A, C2B, C2D, and C2F containing a cargo tyrosine motif [C2A: ysrv (otoferlin aa 31–34); yskv (69–72); C2B: ytsm (285–288); C2D: yyqi (1075–1078); C2F: yhsl (1781–1784)] did directly interact with the GST–AP2mu1 (construct illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1D, lane 2, at ~26 kDa; Figure 5A, C2A, lane 2; C2B, lane 3; C2D, lane 5; C2F, lane 7), whereas C2 domains without the tyrosine motif, C2C and C2E, did not bind to GST–AP2mu1 (Figure 5A, lanes 4 and 6, respectively). Likewise, the selectivity displayed for C2 domain interactions with AP2mu1 carried over to NSF (NSF-GST construct at ~109 kDa is illustrated in Supplementary Figure S1F, lane 2; Figure 6A, C2A, lane 3; C2B, lane 5; C2D, lane 7 and C2F lane 9). C2C and C2E (Figure 6A, lanes 6 and 8, respectively) were not pulled down by GST–NSF. Negative controls included rat C2A and C2B domains incubated with GST-bacterial lysate (without AP2mu1/NSF) under similar conditions to those for the experimental samples.

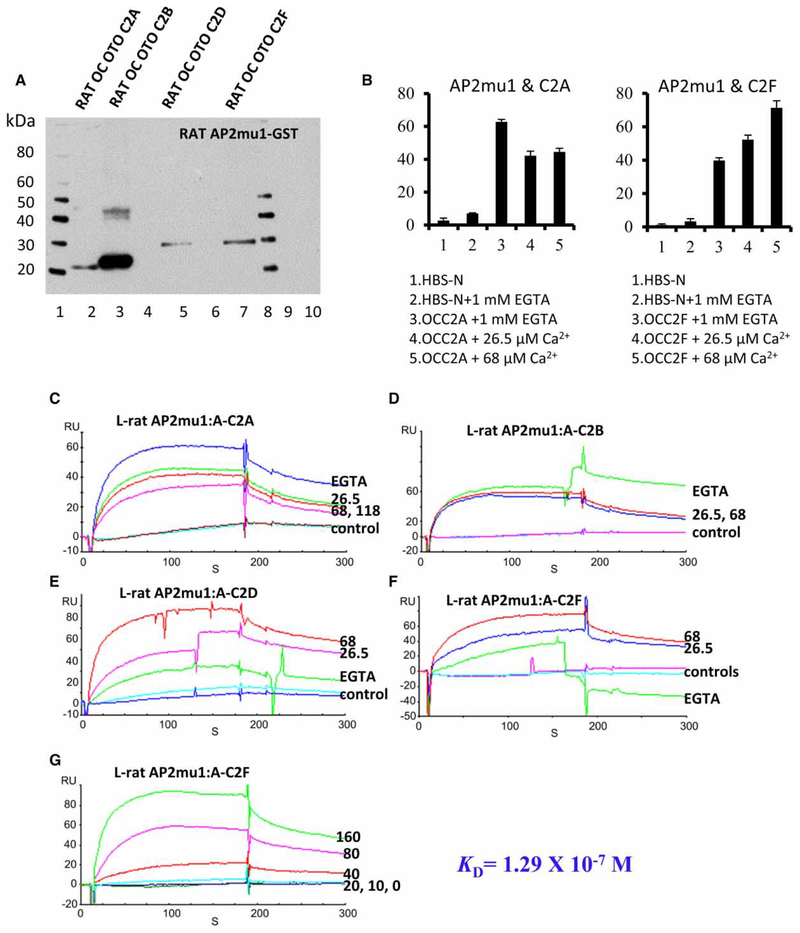

Figure 5. Rat OC otoferlin C2 domains interact with AP2mu1 by pull-down and SPR.

(A) Interaction of rat OC otoferlin C2 domains with GST–AP2mu1 by pull-down assay. Lane 1, protein standards; lanes 2, 3, 5, and 7, pull-down by GST–AP2mu1 of C2A (20 kDa), C2B (24 kDa), C2D (29 kDa), and C2F (28 kDa from the use of C2F-3 primers), respectively, whereas lanes 4 and 6 show no protein bands at ~25 and ~28 kDa, representing C2C and C2E, respectively (300 ng for each C2 domain, anti-Xpress antibody was used for detection); lane 8, protein standards; lanes 9 and 10, negative controls for C2D and C2F with GST-bacterial lysate (no insert), respectively. (B) Binding interactions of OC AP2mu1 with otoferlin C2A and OC AP2mu1 with otoferlin C2F as a function of [Ca2+]: mean ± range, n = 2. (C) Binding interactions of OC otoferlin C2 domains with AP2mu1 (unphosphorylated) observed with pull-down assays were confirmed with SPR analysis, exhibiting both positive and negative dependence on Ca2+. A representative SPR analysis plot is illustrated with AP2 mu1 immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip as a ligand (L) and C2A domain as an analyte (A) (100 nM). An inverse relation of binding with [Ca2+] was observed (see also B). The binding response was enhanced at 1 mM EGTA (blue) and decreased with elevation ofCa2+: 26.5 μM Ca2+ (green), 68 μM Ca2+ (red), and 118 μM Ca2+ (magenta) with no binding for negative controls HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA (red) and HBS-N buffer alone (cyan). (D) The interaction of AP2mu1 with the C2B domain of otoferlin (100 nM) occurred in the absence of Ca2+ (1 mM EGTA, green) and was unchanged at 26.5 μM Ca2+ (blue) or 68 μM Ca2+ (red). No binding was found for negative controls HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA (magenta) or HBS-N SPR buffer alone (cyan). (E) The interaction of AP2mu1 with otoferlin C2D was positively dependent on Ca2+. Maximum binding was observed at 68 μM free Ca2+ (red), followed by intermediate levels of binding at 26.5 μM Ca2+ (magenta). Binding did occur in the absence of free Ca2+ (1 mM EGTA, green) compared with the response with HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA (cyan) or HBS-N buffer alone (blue). (F) The interaction of AP2mu1 (ligand) and otoferlin C2F (as an analyte at 100 nM) was also positively dependent on Ca2+ (also see B). A maximum response was found at 68 μM free Ca2+ (red) compared with that for 26.5 μM Ca2+ (blue). Again, there was a smaller but finite response for EGTA (1 mM, green). Negative controls included HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA (cyan) and HBS-N buffer alone (magenta). (G) A kinetic series is illustrated for AP2mu1 (unphosphorylated) as a ligand and otoferlin C2F as an analyte at 26.5 μM Ca2+. Affinity-purified AP2mu1 was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip, and the C2F domain was diluted in a series of concentrations: 160 nM (green), 80 nM (magenta), 40 nM (red), 20 nM (cyan), 10 nM (blue), and 0 nM (green), yielding a KD of 1.29 × 10−7 M.

Figure 6. Alternatively, rat OC otoferlin C2 domains interact with NSF by pull-down and SPR.

(A) Interaction of rat OC otoferlin C2 domains with GST–NSF by pull-down assays. Lanes 1 and 10, western standards; lanes 2 and 4, GST negative controls (no NSF insert) with C2A and C2B domains, respectively; detection by anti-Xpress antibody. Lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9 indicate pull-down of C2A (20 kDa), C2B (24 kDa), C2D (29 kDa), and C2F (28 kDa) with GST–NSF, whereas lanes 6 and 8 indicate negative results for pull-down of C2C (25 kDa) and C2E (28 kDa) with GST–NSF; 300 ng of each C2 domain was used for each reaction in the representative experiment illustrated. (B) SPR-determined binding interactions of OC NSF with otoferlin C2A as a function of Ca2+ (mean ± range, n = 2) and also, OC NSF PPI with otoferlin C2F as a function of [Ca2+]: mean ± range, n = 3, P = 0.0538(*), the unpaired, two-tailed t-test for 1mM EGTA vs. 68 μM Ca2+.(C) SPR sensorgram analysis of interactions between rat NSF as ligand (L) and the C2 domains of otoferlin as analyte (A) with each C2 domain tested at 100 nM in buffer with Ca2+ at 26.5 μM. The otoferlin C2F (red) gives the maximum response, followed by C2D (green), C2A (magenta), and C2B (blue). Very little binding was observed for C2C (cyan) and none detectedfor C2E (gray), compared with the response to HBS-N buffer alone (red) as a negative control. (D) An inverse dependence on [Ca2+] was observed for binding between C2A (50 nM) and NSF. The maximum response (65 RU) was observed in the absence of Ca2+ (1 mM EGTA, green) relative to a lesser response at 26.5 μM Ca2+ (blue) and less yet at 68 μM Ca2+ (red). Negative controls included HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA (magenta) and HBS-N buffer alone (cyan). (E) Interaction of the C2B domain of otoferlin as an analyte at 50 nM with NSF as ligand was maximized in the absence of Ca2+ (1 mM EGTA, blue). The interaction occurred to a lesser extent at 68 mM free Ca2+ (red) and at 26.5 μM Ca2+ (green), although not following strict inverse concentration dependence. HBS-N buffer alone (cyan) and HBS-N buffer + 1 mM EGTA (magenta) served as negative controls. (F) The interaction of otoferlin C2D (50 nM) with NSF was positively dependent on Ca2+. The maximum response (43 RU) was obtained at 68 μM free Ca2+ (magenta), followed by 26.5 μM free Ca2+ (green). A measurable but low response was observed with no added Ca2+ (1 mM EGTA, blue) compared with negative controls HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA (red) and HBS-N buffer alone (cyan). (G) By SPR analysis, the interaction between NSF and the C2F domain was positively dependent on Ca2+ with maximum interaction recorded at 68 mM free Ca2+ (red), followed by the response at 26.5 μM free Ca2+ (blue). C2F did interact with NSF but to a lesser extent in the complete absence of Ca2+ (1 mM EGTA, green) compared with binding responses for negative controls, HBS-N + 1 mM EGTA (magenta), and HBS-N buffer alone (cyan) under the same conditions. (H) A kinetic series for interactions of NSF and C2F is illustrated. With purified NSF immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip, the responses are given for analyte otoferlin C2F (26.5 μM free Ca2+) at 320 nM (green), 160 nM (magenta), 80 nM (red), 40 nM (blue), 20 nM (cyan), 10 nM (green), and 0 nM (magenta). High-affinity interaction can be inferred from the calculated KD of 2.3 × 10−9 M.

SPR characterization of the interaction between rat OC otoferlin C2 domains with AP2mu1 and NSF

With SPR analysis, we confirmed results from pull-down assays and obtained evidence for a differential calcium dependency of the AP2mu1–otoferlin C2 domain interactions with all proteins expressed as pRSET-A fusion proteins (Figure 5). Binding of the C2 domains to AP2mu1 occurred in the absence of Ca2+ for C2A, C2B, C2D, and C2F. However, the interactions were enhanced by an increase in free Ca2+ for C2D (Figure 5E, 68 mM Ca2+ in red; EGTA in green) and C2F (Figure 5F, 68 μM Ca2+ in red; EGTA in green with results summarized in Figure 5B) and diminished by Ca2+ for C2A (Figure 5C, 118 μM Ca2+ in magenta; EGTA in blue; results summarized in Figure 5B). The interactions of otoferlin C2B with AP2mu1 were undiminished with an increase in Ca2+ (Figure 5D, 68 μM Ca2+ in red; EGTA in green).

SPR also confirmed the differential interaction of individual otoferlin C2 domains with NSF observed in pull-down assays. Otoferlin C2A, C2B, C2D, and C2F all robustly bound to NSF (Figure 6C, magenta, blue, green, and red, respectively) as opposed to C2C and C2E (Figure 6C, cyan and gray, respectively) at 26.5 μM Ca2+. The order of binding was C2F > C2D > C2B > C2A (Figure 6C). The occurrence of little or no binding for C2C and C2E was similar qualitatively to the lack of interaction of these two C2 domains with AP2mu1 observed with SPR. To better understand details of the NSF interactions with C2 domains, we performed a separate set of experiments with individual C2 domains binding to NSF as a function of [Ca2+]. Similarly to the results obtained for AP2mu1, C2A showed diminished binding to NSF with increasing [Ca2+], with binding maximal when there was no calcium in the running buffer (1 mM EGTA in HBS-N SPR buffer, Figure 6D, green; results summarized in Figure 6B). Maximum binding of NSF was also observed for C2B with EGTA (Figure 6E, blue). In contrast, C2D and C2F showed enhanced binding to NSF with increasing [Ca2+] (Figures 6F,G; results for C2F summarized in Figure 6B), also similar to interactions of AP2mu1.

Among the C2 domains, we selected C2F as a model C2 domain for further kinetic analysis, because of its documented biological importance in hearing and deafness [18,27,28] and the finding that C2F binds to NSF with greatest affinity relative to the other C2 domains (Figure 6C). With NSF as a ligand, the KD for the interaction of NSF and analyte C2F according to the global analysis across analyte concentrations using the Langmuir model (1:1 binding) was 2.3 × 10−9 (Figure 6H), representing higher affinity than for C2F binding to AP2mu1 (1.3 × 10−7; Figure 5G). The results are summarized in Table 1. Both analyses were carried out at [Ca2+] = 26.5 μM [P < 0.02(***), unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test, difference between means, ka for NSF/C2F vs. AP2mu1/C2F, for a set of individual values presented as mean ± SD, n = 3].

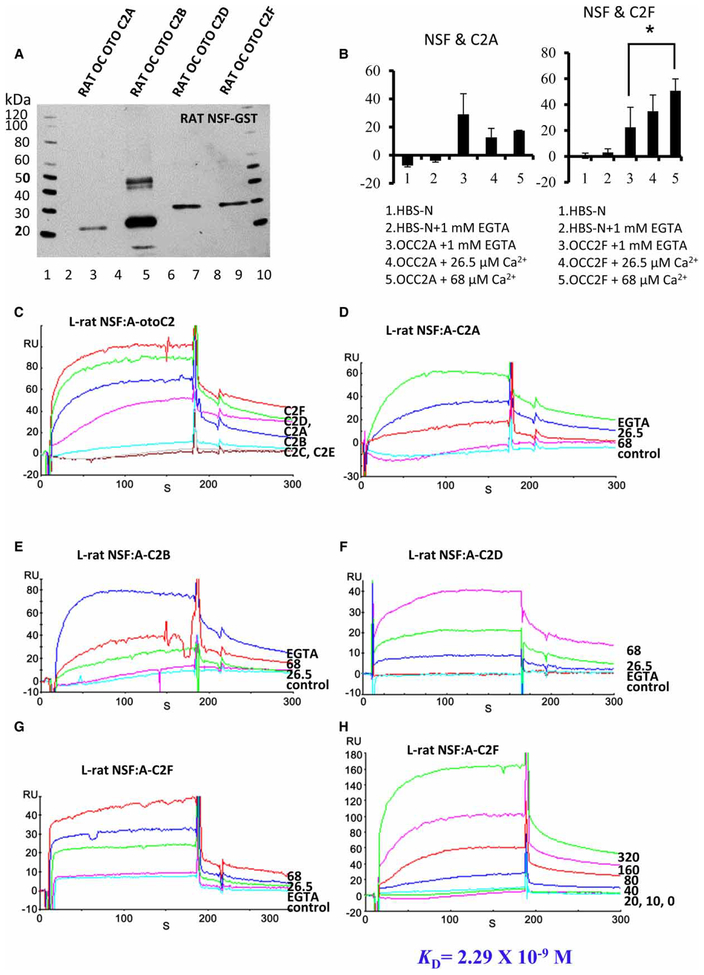

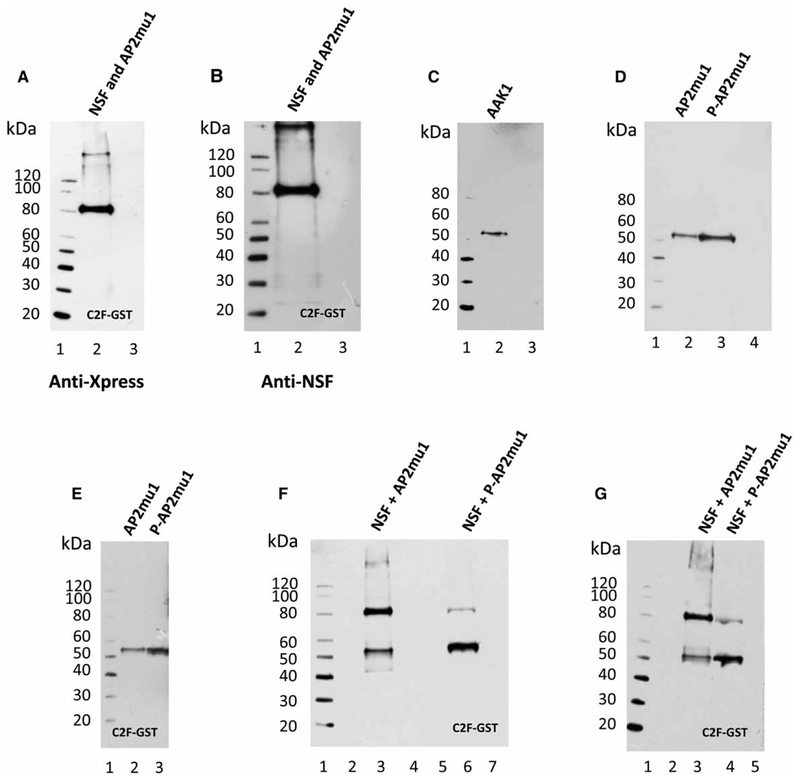

Competitive pull-down assays of otoferlin C2F with NSF and AP2mu1 and phosphorylation as a molecular switch between alternate interactions

Competitive pull-down assays were performed for rat OC C2F with NSF and AP2mu1 fusion proteins. In accord with the KD values for C2F binding to NSF (KD = 2.3 × 10−9 M, Figure 6H) compared with lesser C2F binding to AP2mu1 (KD = 1.3 × 10−7 M, Figure 5G and Table 1), C2F in GST was found to bind NSF in preference to AP2mu1, when AP2mu1 and NSF were presented in equal concentrations (~500 ng), with NSF at ~82 kDa, detected with either anti-Xpress (Figure 7A, lane 2) or NSF-specific primary antibody (Figure 7B, lane 2). AP2mu1 would have been detected with anti-Xpress antibody at ~52 kDa (Figure 7A, lane 2; see Supplementary Figure S1E for OC C2F-GST at ~51 kDa). We considered the possibility that phosphorylation might represent a molecular switch that would move otoferlin C2F from interacting with NSF (and membrane fusion) to interacting with AP2mu1 (mediating endocytosis). Phosphorylation of AP2mu1 at Thr156 by AAK1 is reported to increase binding of AP2mu1 to its cargo, resulting in endocytosis of the cargo [29–31].

Figure 7. Competitive protein interactions of AP2mu1 with NSF and AP2mu1 with otoferlin C2F as a function of AP2mu1 protein phosphorylation.

(A) Competitive binding interactions of rat OC NSF and AP2mu1 for the otoferlin C2F domain by GST pull-down assay and anti-Xpress detection. Lane 1, protein standards; lane 2, affinity-purified rat OC NSF and AP2mu1 fusion proteins (~500 ng each) mixed with rat OC otoferlin C2F in GST: C2F interacted with NSF (~82 kDa) to the exclusion of AP2mu1 (~32 kDa); lane 3, negative control for which NSF and AP2mu1 were mixed with GST-bacterial lysate (no insert). (B) Panel is similar to A, except that a specific anti-NSF monoclonal antibody (Experimental) was used for detection. (C) Western blot of rat OC adapter-associated kinase 1 (AAK1), aa 1–400, in pRSET-A fusion protein. Lane 1, protein standards; lane 2, affinity-purified fusion protein of AAK1 at (52 kDa) detected with anti-Xpress antibody; lane 3, pRSET-A bacterial lysate as a negative control. (D) Western blot of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated-enriched forms of AP2mu1, synthesized in vitro, and detected with antiphospho-AP2mu1 monoclonal antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). Lane 1, protein standards; lane 2, untreated form of AP2mu1 at ~54 kDa (full-length AP2mu1 + vector); lane 3, phosphorylated form of AP2mu1 by treatment with AAK1 at~54 kDa; lane 4, pRSET-A bacterial lysate as a negative control. (E) Interaction of otoferlin C2F domain in the GST construct with phosphorylated-enriched and unphosphorylated forms of AP2mu1 in pRSET-A by the pull-down assay for proteins in vitro. Lane 1, protein standards; lane 2, 250 ng of unphosphorylated form of AP2mu1 mixed with C2F-GST cleared lysate and the pull-down product detected by anti-Xpress, indicating limited binding between C2F and AP2mu1 at ~54 kDa; lane 3, 250 ng of phosphorylated-enriched form of AP2mu1 mixed with C2F in GST cleared lysate; results show that the binding interaction is up-regulated by using the phosphorylated-enriched form of AP2mu1 at ~54 kDa (detected with anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody). (F) Competitive binding interactions of phosphorylated-enriched and unphosphorylated forms of AP2 mu1 and rat OC NSF in pRSET-A with the C2F domain of otoferlin in the GST fusion construct by the pull-down assay. Lane 1, protein standards; lane 2, affinity-purified rat OC NSF and unphosphorylated AP2mu1 fusion proteins (each ~250 ng) mixed with GST-bacterial cleared lysate as a negative control; lane 3, affinity-purified rat NSF and unphosphorylated AP2mu1 fusion proteins (each ~250 ng) mixed with C2F-GST-bacterial cleared lysate. Pull-down with anti-Xpress detection indicates that C2F binds more strongly to the NSF (~82 kDa) than to unphosphorylated AP2mu1 (~54 kDa); lane 4 presents a negative control in which NSF and the unphosphorylated form of AP2mu1 were mixed with GST beads (without C2F) and no proteins were detected; lane 5, another negative control in which NSF and phosphorylated-enriched form of AP2mu1 were mixed with GST-bacterial lysate (no insert); lane 6, affinity-purified rat NSF and phosphorylated-enriched form of AP2mu1 fusion proteins (each ~250 ng) mixed with C2F-GST-bacterial cleared lysate. Pull-down indicated that C2F binding to AP2mu1 (~54 kDa), when phosphorylated, was enhanced (relative to that observed in lane 3) and C2F binding to NSF (~82 kDa) was reduced in a competitive binding assay, i.e. evidence for a molecular switch. Lane 7, another negative control in which NSF and the phosphorylated form of AP2 mu1 were mixed with GST beads (no C2F). No proteins were pulled down as detected with anti-Xpress antibody. (G) A second example of competitive binding interactions for phosphorylated-enriched and unphosphorylated AP2 mu1 and NSF in pRSET-A for the C2F domain of otoferlin in GST fusion protein. Lane 1, protein standards; lane 2, affinity-purified rat OC NSF and unphosphorylated AP2mu1 fusion proteins (~250 ng) mixed with GST-bacterial cleared lysate as a negative control; lane 3, affinity-purified rat NSF and unphosphorylated form of AP2mu1 fusion proteins (each ~250 ng) mixed with C2F-GST-bacterial cleared lysate. Again, pull-down indicated stronger binding of C2F with NSF (~82 kDa) than to AP2mu1 (at ~54 kDa); lane 4, affinity-purified rat NSF and the phosphorylated-enriched form of AP2mu1 fusion proteins (each ~250 ng) mixed with C2F-GST-bacterial cleared lysate. Pull-down again indicated that the phosphorylated form AP2mu1 (at ~54 kDa) binds more strongly to C2F than the unphosphorylated (lane 3), whereas in this competition with phosphorylated AP2mu1, NSF (~82 kDa) binds less strongly (compare with lane 3), again indicating that phosphorylation of AP2mu1 would constitute a molecular switch; lane 5, negative control with NSF and the phosphorylated form of AP2mu1 mixed with GST-bacterial lysate (without C2F), with anti-Xpress monoclonal antibody used for detection.

Initially, differential levels of phosphorylation of AP2mu1 were achieved with exposure of rat brain lysate to calyculin-A that inhibits phosphatase activity, thereby increasing levels of phosphorylation of brain AP2mu1 relative to untreated lysate. The form of AP2mu1 pulled down by otoferlin C2F was more phosphorylated in calyculin-A-treated (Supplementary Figure S2C, lane 3) than -untreated brain lysate (Supplementary Figure S2C, lane 2), detected with a Thr156 phosphospecific AP2mu1 antibody. The total AP2mu1 pulled down by C2F (sum of phosphorylated and unphosphorylated AP2mu1 by a mouse monoclonal antibody detecting both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated AP2mu1 protein) was not different (Supplementary Figure S2B, lane 3 with calyculin-A compared with lane 2 without calyculin-A). The phosphatase inhibitor calyculin-A did not decrease binding of C2F to NSF as detected with a specific anti-NSF antibody (Supplementary Figure S2D, lane 3 with calyculin-A-treated compared with lane 2, calyculin-A-untreated).

To eliminate effects of nonspecific phosphorylation/dephosphorylation by calyculin-A of other proteins in brain lysate that might indirectly affect binding between the three proteins, we turned to in vitro binding, limiting the number of variables to one, that being the level of phosphorylation of AP2mu1. The protein AAK1 was synthesized (Figure 7C, lane 2 at ~54 kDa for aa 1–460) and utilized to phosphorylate AP2mu1 (Figure 7D, western blot, compare lane 3, phosphorylated form of AP2mu1 to lane 2, untreated AP2mu1 detected with antiphospho-AP2mu1 monoclonal antibody). Pull-down assays indicated stronger binding by C2F of phosphorylated AP2mu1 (Figure 7E, lane 3) vs. unphosphorylated AP2mu1 (Figure 7E, lane 2), equal amounts, detected with anti-Xpress. With levels of phosphorylation of NSF and AP2mu1 under separate control, evidence was obtained with anti-Xpress detection in competitive pull-down assays that supported phosphorylation of AP2mu1 as a molecular switch between two alternative protein complexes. The otoferlin C2F domain interacted with NSF (~82 kDa) in preference to unphosphorylated AP2mu1 (~52 kDa), in equal amounts (Figure 7F, lane 3, also replicated in Figure 7G, lane 3). With phosphorylation of AP2mu1, the preference was reversed (Figure 7F, lane 6 and replicated in Figure 7G, lane 4). In conclusion, the binding of AP2mu1 to C2F was enhanced by phosphorylation of AP2mu1 at the same time as the binding of C2F to unphosphorylated NSF was decreased (Figure 7F,G).

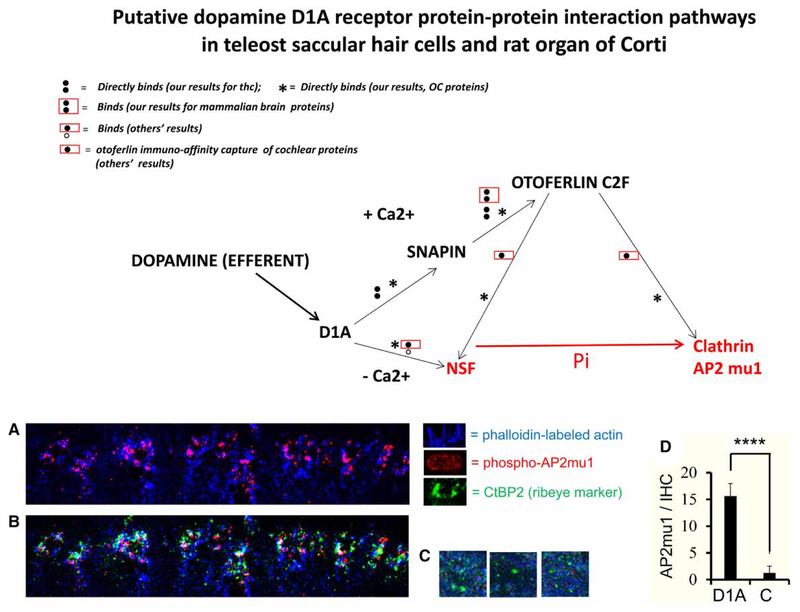

Furthermore, a correlate to the protein interactions in vitro was obtained for the intact mammalian OC. The expression of the phosphorylated form of AP2mu1 (pAP2mu1) was clearly increased at the base of the cochlear IHC by incubation of the intact OC with dopamine D1A agonist, SKF [10 μM; 5 min exposure; Figure 8A, B vs. C; P < 0.0001(⋆⋆⋆⋆) unpaired, two-tailed t-test, Figure 8D]. The pAP2mu1 (pink) in D1A agonist-exposed OC co-localized with F-actin (blue) at the base of the IHC (Figure 8A), clustering with hair cell ribbon synapse marker protein CtBP2 (ribeye; green; Figure 8B), compared with the low level of expression of pAP2mu1 in controls (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. Model for dopamine D1A protein interactions with otoferlin synaptic pathways suggesting that Ca2+ and phosphorylation are used as molecular switches to move from membrane fusion to endocytosis.

In the absence of Ca2+ influx, dopamine D1A receptor is hypothesized to bind via its carboxy terminus to NSF. In response to increases in [Ca2+]i (a molecular switch), protein interactions of D1A to snapin and the otoferlin C2F domain (and full-length otoferlin) are promoted. Otoferlin C2F interacts with (unphosphorylated) NSF in preference to interacting with (unphosphorylated) clathrin AP2mu1. Influx of Ca2+ and consequent phosphorylation of AP2mu1 gives rise to a molecular switch and formation of an alternate protein complex with C2F realigning from its interaction with NSF to alternatively aligning with clathrin AP2 mu1, a cargo adaptor subunit for the plasma membrane that links the cargo protein to the clathrin-coated pit in endocytosis. (A) Plus D1A agonist: expression of phosphorylated AP2mu1 (red/pink) overlapping actin (phalloidin-blue) was enhanced at the base of cochlear IHCs relative to controls (C) after 5 min of exposure of rat OC to dopamine D1A receptor agonist SKF (10 μM). The IHCs, which alternate with supporting cells, were identified by cellular co-expression of the ribbon synaptic marker protein ribeye CtBP2 (see B), that is specifically expressed in the hair cells (~8 μm in Z-direction from IHC stereocilia) and not in supporting cells. (B) Plus D1A agonist: highlighting immunoreactivity for CtBP2 (green), a ribbon synapse hair cell marker (Santa Cruz primary antibody SC-5966). Clustering (in white) was observed of phosphorylated AP2mu1 (red), actin (blue), and CtBP2 (green) at the base of cochlear IHC occurring after 5 min incubation of rat OC with dopamine D1A receptor agonist SKF (10 μM). (C) Minus D1A agonist (control): immunofluorescence localization of phosphorylated AP2mu1 (red), actin (blue), and CtBP2 (green) at the base of IHCs in controls incubated in physiological saline without dopamine D1A receptor agonist SKF. (D) AP2mu1 (dots/IHC) (1-mm optical slices from z-stack confocal microscopy) is plotted for dopamine D1A agonist-treated OC (D1A) (n = 11) compared with control (C) OC incubated with saline (n = 8). The mean ± standard deviation for D1A and C were significantly different, P < 0.0001(****), by the GraphPad unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

Discussion and conclusions

Dopaminergic receptor input to vestibular hair cells

Previously, we identified the components of adenylyl cyclase second messenger pathways in teleost saccular hair cells that predicted for the first time dopaminergic signal transduction that would be elicited by activation of dopamine D1A and D2L receptors in teleost and mammalian vestibular hair cells [1,2]. Dopaminergic efferent input to vestibular hair cells, correlated with tyrosine hydroxylase input to type I and type II vestibular hair cells, is hypothesized to modulate intracellular levels of cAMP, and consequently, cAMP-gating of HCN Ih channels, hair cell membrane potential, and hair cell afferent signaling [32]. Furthermore, the postsynaptic dopamine receptors on hair cells would regulate cellular function via DRIPs that bind to dopamine receptor intracellular domains [33].

In the present investigation, DRIPs in saccular hair cells were identified by yeast two-hybrid mating protocols utilizing the cytoplasmic carboxy terminus of dopamine D1A4 as bait and a cDNA library constructed from >1 × 106 purified saccular hair cells, free of other contaminating cell types, as prey [14]. The SNARE-associated prey protein snapin was identified (GenBank accession no. KF644438), consistent with a role for the D1A receptor in the regulation of synaptic release of receptoneural transmitter by vestibular hair cells [2]. This interaction was confirmed with forward and reverse Y2H co-transformation protocols, pull-down assays, and SPR.

Cochlear hair cell dopaminergic signal transduction