Abstract

Purpose:

Polycomb group (PcG) proteins are critical epigenetic mediators of stem cell pluripotency, which have been implicated in the pathogenesis of human cancers. The present study was undertaken to examine the frequency and clinical relevance of PcG protein expression in malignant pleural mesotheliomas (MPM).

Experimental Design:

Microarray, quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR), western blot and immunohistochemistry techniques were used to examine PcG protein expression in cultured MPM, mesothelioma specimens, and normal mesothelial cells. Lentiviral shRNA techniques were used to inhibit EZH2 and EED expression in MPM cells. Proliferation, migration, clonogenicity and tumorigenicity of MPM cells either exhibiting knock-down of EZH2 or EED, or exposed to 3-deazaneplanocin A (DZNep), and respective controls were assessed by cell count, scratch and soft agar assays, and murine xenograft experiments. Micro-array and qRT-PCR techniques were used to examine gene expression profiles mediated by knock-down of EZH2 or EED, or DZNep.

Results:

EZH2 and EED, which encode components of polycomb repressor complex 2 (PRC-2), were over-expressed in MPM lines relative to normal mesothelial cells. EZH2 was over-expressed in ~85% of MPMs compared to normal pleura, correlating with diminished patient survival. Over-expression of EZH2 coincided with decreased levels of miR-101 and miR-26a. Knock-down of EZH2 or EED, or DZNep treatment decreased global H3K27Me3 levels, and significantly inhibited proliferation, migration, clonogenicity, and tumorigenicity of MPM cells. Common as well as differential gene expression profiles were observed following knock-down of PRC-2 members or DZNep treatment.

Conclusions:

Pharmacologic inhibition of PRC-2 expression/activity is a novel strategy for mesothelioma therapy.

Keywords: mesothelioma, epigenetics, polycomb, EZH2, EED, DZNep, microarray

Introduction

Malignant pleural mesotheliomas (MPM) are highly lethal neoplasms attributable to asbestos exposure, as well as ill-defined environmental and genetic factors (1). Due to industrialization and long latency associated with these malignancies, the global incidence of MPM continues to increase (2). Currently, results of conventional treatments for MPM are far from optimal; median survivals of patients undergoing aggressive multimodality therapy for MPM range from 14–28 months, depending on tumor histology and stage, extent of surgical resection, and response to chemotherapy (3) .

During recent years, considerable insight has been achieved regarding the molecular pathogenesis of MPM. These neoplasms exhibit significant, recurrent karyotypic abnormalities (4, 5), perturbed microRNA expression (6, 7), loss of tumor suppressor genes (4), and upregulation of oncogene signaling (5), resulting in cell cycle dysregulation, resistance to apoptosis(8), and enhanced invasion potential of mesothelioma cells (9). Epigenomic alterations have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of MPM. For example, changes in chromosomal copy number, as well as miRNA expression correlate with global and site-specific alterations in DNA methylation in these neoplasms (7, 10, 11). In several studies, DNA methylation signatures in MPM appear to coincide with exposure to specific carcinogens (12, 13). In addition, MPM exhibit a global increase in histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation (H3K27Me3) (14) suggestive of aberrant expression/activity of Polycomb group (PcG) proteins (15). The present study was undertaken to examine the frequency and potential clinical relevance of PcG expression in MPM.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines:

H28, H2052, and H2452 MPM cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), and cultured in RPMI 10% FCS with Pen/Strep (complete media). LP3 and LP9 normal mesothelial cells were obtained from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research (Camden, NJ), and cultured according to vendor instructions. NCI-SB-NMES1-and 2 were isolated from histologically normal pleura, and cultured as described (16). NCI-SB-MES1–4 were established from primary MPM, and cultured in complete RPMI media. These cell lines have been validated by HLA typing, and molecular phenotyping relative to the respective primary tumors. All tissues for cell lines or gene expression analysis were procured in accordance with IRB-approved protocols.

RNA isolation and microarray analysis:

Total RNA was isolated from cell lines or snap-frozen surgical specimens using the RNeasy minikit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA). Normal pleural RNA from individual patients without MPM was obtained from ProteoGenex (Culver City, CA). Gene expression profiles were analyzed using Gene-Chip Human Genome U133 2.0 plus Arrays (Affymetrix) or Illumina Arrays according to vendor instructions; higher order analysis was performed using Gene Sprint and Ingenuity Pathway software.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR:

RNA was subjected to reverse transcription using a BioRad RT kit (Hercules, CA), and gene expression was analyzed using the TaqMan real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) kit and primers/probes listed in Supplementary Table 1.

MicroRNA isolation and quantitation:

Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis was used to determine the relative expression levels of miR-101, miR-26a, miR-26b, and RNU44 in MPM specimens using previously described techniques (17). Briefly, microRNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and the RT2 qPCR-Grade miRNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen). Equal amounts of miRNA were converted into cDNA using miR-101, miR-26a, miR-26b, and RNU44 RT primers (Applied Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative PCR was performed using primers and materials from Applied Biosystems. The Ct values were used to calculate the relative fold difference in miRNA levels. All experiments were performed using biological triplicates. The data were normalized to RNU44 expression levels.

Generation of stable cells expressing shRNA constructs:

MPM cell lines were transfected with commercially validated shRNAs targeting EZH2, or EED, or sham sequences (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell lines were selected with puromycin, and knock-down confirmed by immunoblot analysis.

Immunohistochemistry of primary tumor samples:

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks from primary MPM specimens and unmatched normal pleura from autopsy specimens resected on IRB-approved protocols at the NCI, as well as tissue microarrays containing normal mesothelia, MPM and peritoneal mesotheliomas (PM) (US Biomax; Rockville, MD) were stained with mouse anti-EZH2 (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA) at a 1:50 dilution following heat-induced epitope retrieval in a citrate buffer solution. Detection was performed using the Ventana Nexus automated immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) with a diaminobenzidene chromogen and hematoxylin counterstain. Appropriate tissue controls were included in each run. Hematoxylin and eosin stains were performed for morphologic assessment. The immunostains were scored by a board-certified pathologist (HM) in a blinded manner, with extent of staining being graded from 0–4 based on the percentage of positive cells: 0- no positive cells, 1-less than 25% positive, 2– 26-50% positive, 3– 51-75% positive, 4– 76-100% positive.

Immunoblotting:

Submitted as Supplementary Materials.

Proliferation assays:

1500 cells were plated in triplicate in tissue-culture treated 96-well plates and allowed to proliferate for 5 days. Cell proliferation was measured on days 1–5 using the CellTiter 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega, Madison, WI). Each experiment was performed three times.

Cell migration assays:

Cell lines were plated in triplicate to near confluent monolayers in six well plates, and migration assessed as described (18). For 3-deazaneplanocin A (DZNep) experiments, DZNep at indicated concentrations was added at the time of the scratch, and then daily until the conclusion of the experiment. Each experiment was performed three times.

In vitro DZNep treatment:

DZNep was dissolved in water to a stock concentration of 10 mM, and subsequently diluted to experimental concentrations in complete RPMI media. Cells were plated in appropriate tissue-culture dishes; the following day, media was replaced with fresh complete media, or complete media containing DZNep at the appropriate concentrations. Media was changed daily with fresh DZNep for the three day treatment.

Soft Agar Clonogenicity:

Submitted at Supplementary Materials.

Murine xenograft experiments:

Submitted as Supplementary Materials.

SuperArray analyses:

Submitted as Supplementary Materials.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA):

Submitted as Supplementary Materials.

Statistical analysis:

Standard error of the mean is indicated by bars on all figures and was calculated using Microsoft Office Excel 2007. All experiments were performed with at a minimum of triplicate samples, and all p values were calculated with two-tailed t-tests, unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Isolation and Characterization of NCI Cell Lines:

NCI-SB-NMES1 and NCI-SB-NMES2 (NMES1 and 2) were isolated from histologically normal pleura from a 78 year old female smoker and a 36 year old female non-smoker, respectively who underwent thoracotomy for early stage non-small cell lung cancer at the NCI. These lines are capable of growth in tissue culture for approximately 20–30 passages before senescence. NCI-SB-MES1–4 (MES1–4) were established from histologically-confirmed MPM resected at the NCI. MES1, 2 and 4 were derived from epithelial tumors, whereas MES3 was established from biphasic MPM. No patient underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy prior to resection and isolation of tumor cell lines. Demographic data pertaining to the patients from whom these lines were established, as well as molecular phenotypes of the lines are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. The photo-micrographic appearances of NMES1and 2 and MES1–4 are similar to those corresponding to commercially available normal mesothelial cell cultures, LP3 and LP9, and MPM cell lines H28, H2052, and H2452, respectively (Supplementary Figures 1A and B).

Over-expression of EZH2 and EED in MPM Cells:

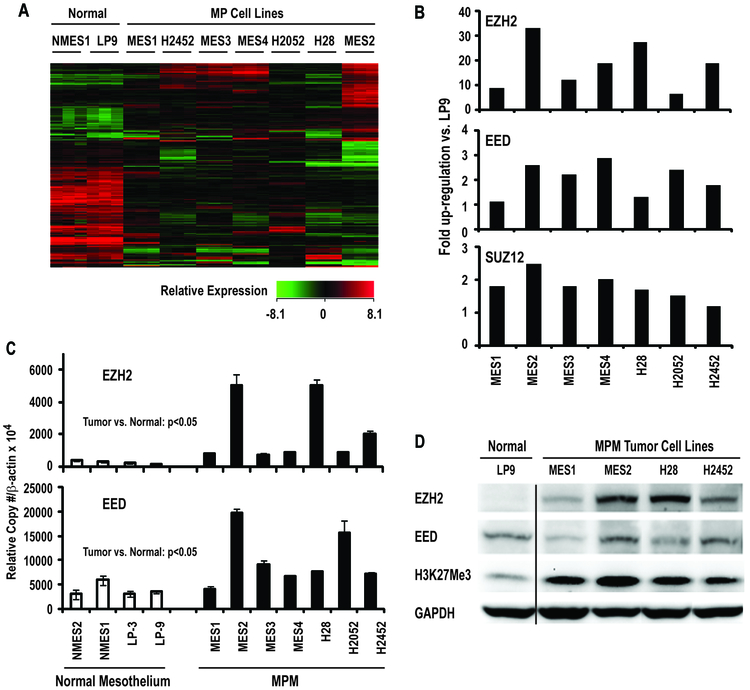

Affymetrix U133 2.0 plus microarrays were used to examine global gene expression profiles, and specifically identify genes encoding PcG proteins in MES1–4, H28, H2052, and H2452 MPM cells relative to LP9 and NMES1. Consistent with previous studies pertaining to gene expression analysis of MPM (11), unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis of triplicate samples for each cell line demonstrated that gene expression profiles in MPM lines were distinctly different than those observed in NMES1 and LP9 cells (Figure 1A). Interestingly, MPM lines exhibited over-expression of EZH2 (also known as KMT6) and to a lesser extent, EED and SUZ12, which encode core components of polycomb repressor complex-2 (PRC-2), recently implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of human cancers (15) (Figure 1B). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) experiments were undertaken to further examine EZH2 and EED expression in MPM cells; primers for EZH2 recognized both splice variants. This analysis confirmed that EZH2 and EED were over-expressed in MPM lines relative to cultured normal mesothelial cells (Figure 1C). Subsequent qRT-PCR experiments revealed that both EZH2 splice variants were coordinately expressed at comparable levels in MPM cells (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis (Figure 1D) demonstrated that EZH2 protein levels in cultured MPM cells were higher than those observed in normal mesothelial cells. However, EED levels did not appear to be increased in MPM cells. Additional immunoblot experiments revealed a global increase in the PRC-2 mediated repressive chromatin mark, H3K27Me3 in MPM cells (Figure 1D).

Figure 1:

Components of Polycomb Repressor Complex-2 are over-expressed in mesothelioma cells.

A: Heat map demonstrating that gene expression profiles of mesothelioma cells are distinctly different from cultured normal mesothelia.

B: Micro-array results depicted as fold up-regulation of EZH2, EED, and SUZ12 in cultured MPM lines relative to normal mesothelial cells.

C: qRT-PCR analysis of EZH2 and EED expression in MPM cell lines relative to cultured normal pleura or mesothelial cells.

D: Immunoblot of EZH2, EED, and H3K27Me3 expression in MPM lines relative to cultured normal mesothelia. Up-regulation of EZH2 coincided with a global increase in H3K27Me3 levels in MPM cells.

Analysis of EZH2 and EED Expression in Primary Mesotheliomas:

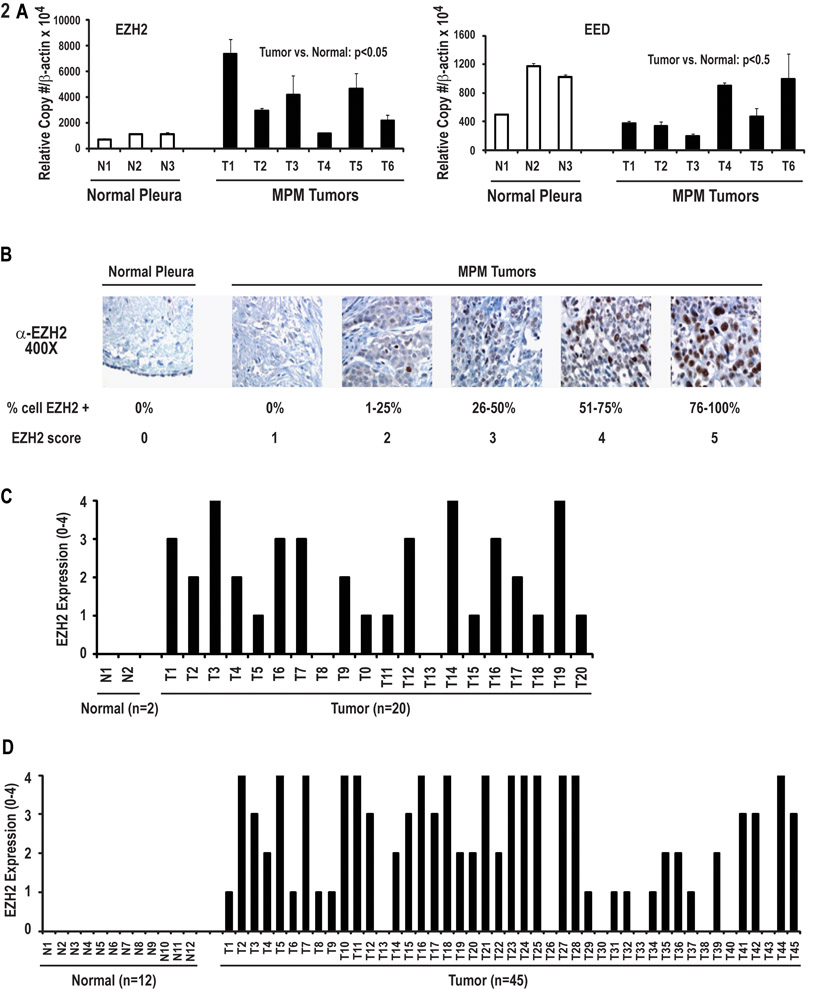

qRT-PCR experiments were performed to examine expression of EZH2 and EED in a panel of primary MPMs resected at the NCI. Interestingly, this analysis revealed up-regulation of EZH2, but not EED in 5 of 6 primary epithelial MPM relative to normal pleura (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry experiments were undertaken to further examine EZH2 expression in these 6 specimens as well as 14 additional MPM resected at the NCI. This analysis revealed no detectable EZH2 expression in normal pleura or stroma; a spectrum of EZH2 expression was detected in mesothelioma cells (Figure 2B). In general, EZH2 levels tended to coincide with mRNA copy numbers, although some variations were noted, suggesting that post-transcriptional mechanisms also contribute to EZH2 over-expression in MPM. Furthermore, EZH2 expression coincided with mRNA copy numbers in MES1–4 cells, and correlated with tumors from which the lines were derived; a gradient of EZH2 expression observed in these primary MPM specimens was maintained when the respective cell lines were passaged in vitro (Supplementary Figure 2). Overall, 90% of the 20 primary MPM (16 epithelial, 3 biphasic, and one sarcomatoid) specimens expressed EZH2. (Figure 2C). Additional IHC experiments using tissue microarrays (TMA) revealed that ~85% of 45 mesotheliomas [28 MPM and 17 peritoneal mesotheliomas (PM)] expressed EZH2; no EZH2 expression was observed in 12 normal pleura or peritoneum specimens or stomal elements (Figure 2D). The patterns of EZH2 expression in PM were comparable to those observed in MPM (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 2:

Analysis of EZH2 and EED expression in primary specimens and normal mesothelia.

A: qRT-PCR analysis of EZH2 and EED expression in six primary mesothelioma specimens including four from which MES1–4 cell lines were derived, compared to normal pleura samples. EZH2 levels were significantly higher in primary mesotheliomas relative to normal pleura (p<0.05). This phenomenon was not evident following analysis of EED expression in these specimens.

B: Representative results of immunohistochemical analysis of EZH2 expression in normal pleura and primary MPM.

C: Immunohistochemistry analysis of 20 primary MPM specimens resected at the NCI including tumors from which MES1–4 cell lines were derived relative to normal pleura. The majority of mesothelioma specimens expressed EZH2; no EZH2 expression was detectable in normal pleura.

D: TMA analysis of EZH2 expression in MPM, PM, normal pleura or peritoneum.

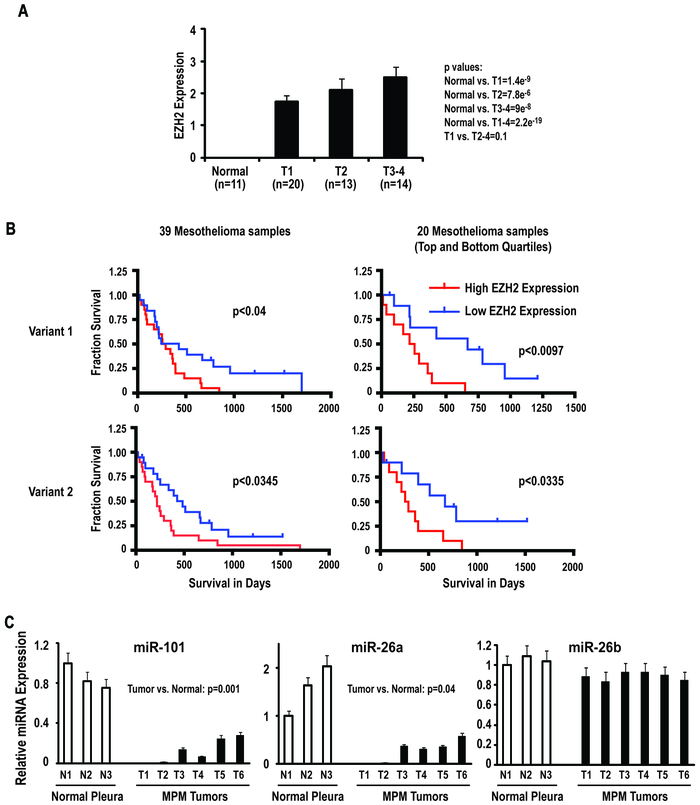

Additional analysis was performed to ascertain if levels of EZH2 protein expression by IHC coincided with tumor burden (T stage) using 20 NCI samples plus 27 of 28 MPMs from the commercial TMA for which T stage was available. The majority of the MPMs on the TMA were epithelial. EZH2 expression was significantly higher in MPM relative to normal pleura ( p< 0001). Although EZH2 expression tended to increase with disease burden, this trend was not statistically significant (Z=0.5; Jonckheere-Terpstra test), possibly due to the small number of samples evaluated (Figure 3A).

Figure 3:

EZH2 expression in primary MPMs relative to T-stage and survival of mesothelioma patients.

A: EZH2 expression by IHC analysis relative to T-stage.

B: Correlation between EZH2 expression in primary MPM assessed by Illumina microarray techniques and patient survival. Over-expression of either of the EZH2 spice variants coincides with diminished survival. Variant 1: median = 1.62; top quartile: 2.94+/− 0.85; bottom quartile 1.14+/− 0.15; p = 2.96e-5. Variant 2: median = 2.14; top quartile: 4.05 +/− 0.81; bottom quartile: 1.53 +/− 2.44; p = 5.46e-7.

C: Analysis of micro-RNA expression in MPM and normal pleura specimens. RNU-44 was used as endogenous normal control for all experiments. miR-101 and miR-26a levels are reduced in MPM specimens relative to normal pleura.

Additional analysis was undertaken to ascertain if intratumoral EZH2 expression detected by Illumina array techniques correlated with survival in 39 patients with locally advanced MPM undergoing potentially curative resections at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (De Rienzo et al; submitted); 24 patients had epithelial mesotheliomas, whereas 7 patients had biphasic and 8 patients had sarcomatoid malignancies. Increased expression of either of the EZH2 splice variants in MPM correlated significantly with shorter patient survival (Figure 3B). The magnitude of EZH2 over-expression did not appear to correlate with histology. The sample size precluded multivariate analysis to determine if EZH2 expression was an independent prognosticator of survival in MPM patients.

Association of EZH2 with miR-101and miR-26 Expression in MPM Cells and Primary MPM Specimens:

Recent studies have demonstrated that over-expression of EZH2 in several human cancers coincides with loss of miR-101 or miR26, which normally target the 3′ UTR of EZH2 (19, 20). As such, q-PCR experiments were performed to examine miR-101 and miR-26 expression levels relative to EZH2 expression in primary MPM specimens and normal pleura (Figure 3C). These experiments demonstrated that miR-101 levels were significantly reduced in MPM cell lines and pleural mesothelioma specimens relative to normal pleura. Furthermore, miR-26a levels were decreased in primary MPM specimens relative to normal pleura. In contrast, levels of miR-26b (which does not target EZH2) in MPM and normal pleura were similar, suggesting that the alterations in miR-101 and miR-26a levels observed in this preliminary analysis were not attributable to a global decrease in micro-RNA expression (Figure 3C).

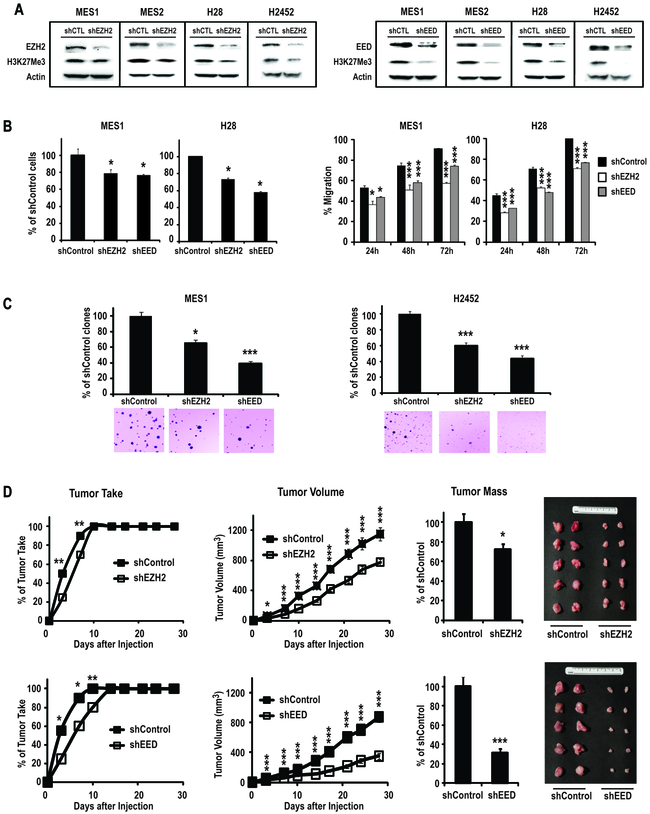

Effects of EZH2 or EED Knock-down in MPM Cells:

Additional experiments were performed to examine if aberrant PRC-2 activity directly contributes to the malignant phenotype of mesothelioma cells. Briefly, shRNA techniques were used to knock-down EZH2 in cultured MPM cells; the shRNA used for these experiments targeted both splice variants of EZH2. Similar experiments were undertaken to knock-down EED, which although not apparently over-expressed in primary MPM, is critical for maintaining stability of PRC-2, and histone methyltransferase activity of EZH2 (15). Immunoblot analysis confirmed that relative to control sequences, shRNAs depleted EZH2 and EED and decreased global levels of H3K27Me3 in MES1–2, H28, and H2452 (Figure 4A). Furthermore, knock-down of these PRC-2 components resulted in 30–50% decreases in proliferation and migration of these four MPM lines (Figure 4B). Interestingly, the effects of EED knock-down on global H3K27Me3 levels, as well as proliferation and migration, appeared to be more pronounced than EZH2 knock-down in MPM cells. Experiments using different shRNAs targeting EZH2 and EED confirmed that knock-down of these PRC-2 components inhibited proliferation of MPM cells, suggesting that the aforementioned results were not due to off-target effects of the shRNAs; the extent of growth inhibition mediated by shRNAs targeting EZH2 or EED appeared to correlate with efficiency of knock-down (Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Effects of stable knock-down of EZH2 and EED in cultured mesothelioma cells. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001

A: Immunoblot analysis of EZH2, EED and H3K27Me3 levels in MPM lines following transduction with shRNA targeting EZH2, EED, or sham sequences. Knock-down of EZH2 (left panel) or EED (right panel) diminishes H3K27Me3 levels in these cells.

B (left panel): Effects of knock-down of EZH2 and EED on proliferation of MES1 and H28 cells. The effects of EED knock-down appear to be more pronounced in both of these cells. Similar results were observed for MES2 and H2452 cells.

B (right panel): Effects of knock-down of EZH2 and EED on migration of MES1 and H28 cells. EZH2 and EED knock-down inhibits migration of MES1 and H28 cells. Similar results were observed for MES2 and H2452 cells.

C: Effects of knock-down of EZH2 and EED on soft agar clonogenicity of MES1and H2452 cells. EZH2, and to a greater extent EED knock-down significantly inhibits soft agar clonogenicity of MPM cells.

D (upper panel): Effects of EZH2 knock-down on tumorigenicity of MES1 cells in nude mice. Knock-down of EZH2 mediates a modest increase in time to tumor take, and a significant decrease in average tumor volume and tumor mass of these xenografts.

D: (lower panel): Effects of knock-down of EED on tumorigenicity of MES1 xenografts in nude mice. Knock-down of EED increases time to tumor take, and significantly decreases tumor volume and tumor mass. Results depicted are representative of two independent experiments for each condition.

Additional experiments were performed to ascertain if knock-down of EZH2 or EED inhibited clonogenicity and tumorigenicity of MPM cells. Knock-down of EZH2 or EED diminished soft agar clonogenicity of MES1 cells by 36% and 66%, respectively, relative to controls. Similarly, knock-down of EZH2 and EED decreased clonogenicity of H2452 cells by 40% and 57%, respectively (Figure 4C). Subsequent experiments revealed that knock-down of EZH2 or EED modestly delayed tumor take, and significantly decreased size and volume of subcutaneous MES1 xenografts in nude mice (Figure 4D). Consistent with results from immunoblot, proliferation and migration experiments, the effects of knock-down of EED on clonogenicity and tumorigenicity were more pronounced then those observed following EZH2 knock-down in MPM cells.

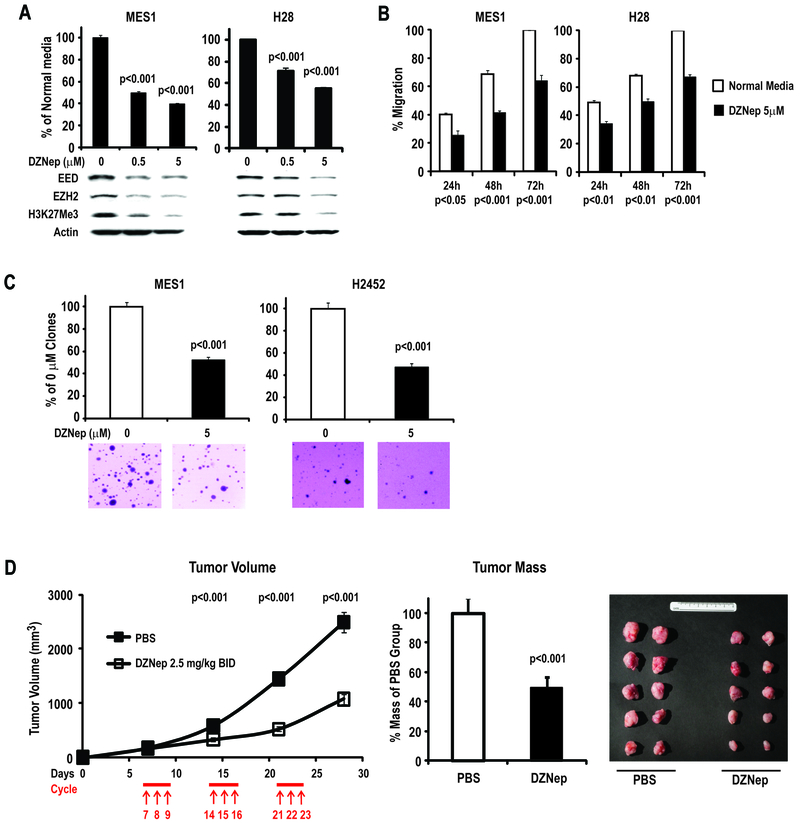

Effects of DZNep in MPM Cells:

Additional experiments were performed to ascertain if pharmacologic agents in early clinical development could recapitulate the effects of EZH2 or EED knock-down in MPM cells. Our analysis focused on DZNep, an S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase (SAH) inhibitor that has been shown to decrease DNA methylation, deplete PRC-2 components, and mediate cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer cells (21, 22). Preliminary experiments revealed that DZNep inhibited proliferation of MPM cells, with the effects tending to plateau off at high doses, suggestive of cytostasis rather than cell death (Supplementary Figure 5A); consistent with these findings, Apo-BrdU analysis revealed that the growth inhibitory effects of DZNep (as well as EZH2 or EED knock-downs) were not associated with increased apoptosis (data not shown). Interestingly, cultured normal mesothelial cells (LP9), which exhibit very low level EZH2 expression, appeared relatively resistant to DZNep (Supplementary Figures 2 and 5A). The growth inhibitory effects of DZNep did not appear to coincide with global DNA demethylation as evidenced by pyrosequencing of repetitive DNA sequences (representative results pertaining to NBL2 are summarized in Supplementary Figure 5B). Immunoblot experiments revealed that 72h DZNep treatment mediated dose-dependent depletion of EZH2, EED and H3K27Me3 in MES1–2, H28 and H2452 cells (Figure 5A; bottom panel); these effects coincided with significantly decreased proliferation and migration of MPM cells (Figure 5A; upper panel, and Figure 5B). Furthermore, DZNep significantly diminished soft agar clonogenicity of MES1 and H2452 cells (Figure 5C).

Figure 5:

Effects of DZNep in MPM cells.

A: DZNep mediates dose-dependent reductions in EED, EZH2 and global H3K27Me3 levels, which coincide with inhibition of proliferation of MES1 and H28 cells. Similar results were observed for MES2 and H2452 cells.

B: Effects of DZNep on migration of MPM cells. Similar results were observed for MES2 and H2452 cells.

C: Effects of DZNep on soft agar clonogenicity of MES1 and H2452 cells.

D: Effects of IP administration of DZNep on growth of established MES1 xenografts in nude mice.

Additional experiments were performed to examine if DZNep could inhibit growth of established MPM xenografts. Preliminary experiments demonstrated that the maximum tolerated dose of DZNep administered intraperitoneally in nude mice with tumor xenografts was 2.5 mg/kg BID (data not shown). In subsequent experiments, nude mice were injected subcutaneously with MES1 cells sufficient to produce 100% tumor take at 7 days. Commencing on day 7, mice received three cycles of DZNep (2.5 mg/kg BID qd x3 q7d). This treatment regimen resulted in significant reduction of tumor size after each treatment cycle, with an approximate 50% reduction in tumor mass at the end of the treatment course (Figure 5D), and no visible systemic toxicity.

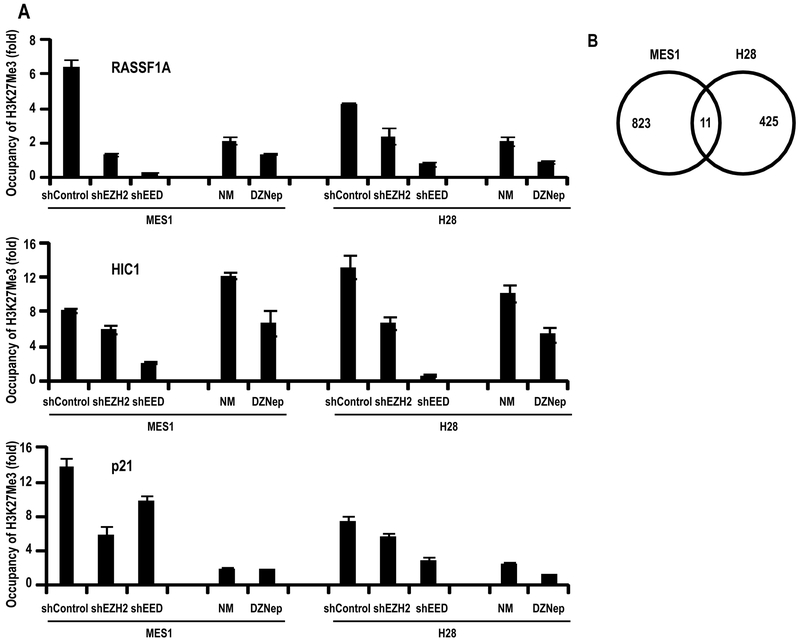

Inhibition of PRC-2 Activity Modulates Tumor Suppressor Gene Expression:

Because PcG proteins have been implicated in regulating expression of genes modulating cell cycle progression, differentiation and stemness (15, 23), focused SuperArray techniques were used to examine if selective depletion of EZH2 and EED, or DZNep treatment modulated expression of oncogene and tumor suppressors as well as stem cell-related genes in MES1 and H28 cells. This preliminary analysis demonstrated a variety of genes regulating cell cycle progression and apoptosis, which were modulated by knock-down and/or DZNep treatment, several of which were selected for further analysis (data not shown). Subsequent qRT-PCR experiments confirmed up-regulation of NF1, FOXD3, FHIT, HIC1, p21, and RASSF1A in MES1 and/or H28 cells following knock-down of EZH2 or EED (Supplementary Table 3). In general, the magnitude of induction of these tumor suppressor genes was more pronounced in EED knock-down cells relative to EZH2 knock-downs. DZNep up-regulated FHIT, HIC1, p21, and RASSF1A, but not NF1 or FOXD3 in MPM cells, suggesting that DZNep mediates overlapping, as well as differential effects relative to EZH2 or EED knock-down in these cells. Immunoblot analysis confirmed results of qRT-PCR experiments (representative data pertaining to p21 and RASSF1A are depicted in Supplementary Figure 6). Collectively, these data suggest that the growth inhibitory effects of targeted disruption of PRC-2 or DZNep treatment in MPM cells are mediated, at least in part, by up-regulation of several tumor suppressors that are known to modulate pluripotency, cell cycle progression and apoptosis in cancer cells.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiments were undertaken to ascertain if activation of tumor suppressor genes in MES1 and H28 cells by DZNep was attributable to depletion of PRC-2 as evidenced by decreased H3K27Me3 levels within the respective promoters. As shown in Figure 6A, H3K27Me3 levels within the promoters of RASSFIA and HIC-1 (putative stem cell polycomb target genes)(24) were markedly decreased in cells exhibiting knock-down of EZH2 or EED, relative to control cells. Similarly, treatment with DZNep decreased H3K27Me3 levels within the RASSFIA and HIC-1 promoters. A similar phenomenon was observed following analysis of p21, suggesting that the growth inhibitory effects of DZNep were not restricted to epigenetic activation of stem cell polycomb targets.

Figure 6.

Effects of DZNep on gene expression in MPM cells.

A: ChIP analysis of H3K27Me3 levels in RASSF1A, HIC-1, and p21 promoters in MES1 and H28 cells following knock-down of EZH2 or EED, or DZNep treatment.

B: Venn diagram of DZNep-modulated genes in MES1 and H28 cells using >1.5 fold and adjusted p< 0.05. Very little overlap was observed between these lines.

Illumina array experiments were performed to examine effects of DZNep on global gene expression in MES1 and H28 cells. Using criteria of >1.5 fold change and p <0.05 for drug treatment relative to untreated controls, 940 and 513 genes were modulated by DZNep in MES1 and H28, respectively, of which 122 overlapped. Using criteria of >1.5 fold change and more stringent adjusted p values (25), 830 and 435 genes were differentially modulated by DZNep in MES1 and H28, respectively (Figure 6B); 55% of differentially expressed genes were up-regulated by DZNep. Only 11 genes were significantly modulated in both cell lines by DZNep, of which only three were simultaneously up- or down-regulated (Supplementary Table 4), suggesting significant differences in underlying histology or genotype. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed significant enrichment of EZH2 gene set in MES1, but not H28 cells following DZNep treatment (Table 1). A variety of additional gene sets and ontologies pertaining to proliferation, and signal transduction were modulated in these cells (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6).

Table 1:

EZH2 Targets Up-Regulated in MES1 following DZNep Treatment.

| SYMBOL | logFC | adj.P.Val | SYMBOL | logFC | adj.P.Val |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADM | 3.15 | 0 | |||

| BDKRB1 | 0.752 | 0 | MT1A | 1.33 | 0 |

| CCL20 | 2.24 | 0 | MT1X | 1.57 | 0 |

| CD44 | 0.711 | 0 | MT2A | 1.88 | 0 |

| CLEC2B | 0.959 | 0 | NLRP3 | 0.587 | 0 |

| CORO1C | 0.668 | 0 | NOV | 1.34 | 0 |

| CXCL2 | 1.14 | 0 | PI3 | 2.09 | 0 |

| DCUN1D3 | 0.684 | 0 | PLAT | 0.952 | 0 |

| DNER | 0.845 | 0 | PRNP | 0.79 | 0 |

| ENTPD7 | 0.631 | 0 | PTGS2 | 1.59 | 0 |

| FAM46A | 0.843 | 0 | PTPRR | 1.11 | 0 |

| FRMD6 | 0.724 | 0 | RGS4 | 1.08 | 0 |

| FTHL7 | 1.19 | 0 | SAA1 | 1.494 | 0 |

| GDF15 | 2.9 | 0 | SAMD9 | 0.826 | 0 |

| HMOX1 | 1.11 | 0 | SERPINE1 | 1.44 | 0 |

| IGFBP3 | 1.98 | 0 | SERPINE2 | 1.1 | 0 |

| IL1B | 1.44 | 0 | SERTAD4 | 0.98 | 0 |

| IL24 | 2.1 | 0 | SLIT2 | 1.04 | 0 |

| IL6 | 3.01 | 0 | SP140 | 0.975 | 0 |

| IL8 | 3.89 | 0 | SQSTM1 | 1.18 | 0 |

| KRT34 | 4.42 | 0 | THBS1 | 0.91 | 0 |

| LAMC2 | 1.18 | 0 | TMEM45A | 0.684 | 0 |

| MGLL | 0.589 | 0 | TP53BP2 | 0.597 | 0 |

| Dataset | Ttest_MES1_nm_Dznep_1p5_adjp05 |

| Upregulated in class | na_pos |

| GeneSet | NUYTTEN_EZH2_TARGETS_UP |

| Enrichment Score (ES) | 0.4477096 |

| Normalized Enrichment Score (NES) | 2.3391728 |

| Nominal p-value | 0 |

| FDR q-value | 0.001003521 |

| FWER p-Value | 0.007 |

Discussion

PcG proteins have emerged as critical epigenetic mediators of pluripotency and differentiation of stem cells (26, 27), as well as aberrant gene repression during malignant transformation (15, 28). Two major polycomb repressor complexes, each of which contain a variety of core subunits have been identified in mammals. The initiation complex, PRC-2, containing EZH2, SUZ12, PCL, and EED subunits, mediates trimethylation of H3K27. PRC-2 recruits the maintenance complex PRC-1, containing core subunits of PCAF, PHC, RING1, CBX, and SML, as well as SFMBT and L3MBTL proteins that mediate ubiquitination of H2AK119 (15). These histone marks coincide with recruitment of chromatin remodeling complexes, formation of heterochromatin, and repression of gene expression by mechanisms, which to date have not been fully elucidated (29, 30). Of particular relevance regarding the role of PcG proteins in tumorigenesis are recent observations that PRC-2 inhibits differentiation of normal pluripotent stem cells (31, 32), and that EZH2 is increased and essential for maintenance of cancer stem cells (33, 34).

In the present study, we observed over-expression of EZH2 in the majority of cultured MPM lines and primary MPM relative to normal mesothelial cells or pleura. Interestingly, TMA experiments also demonstrated over-expression of EZH2 in PM, suggesting that common epigenetic pathways mediate the pathogenesis of pleural and peritoneal mesotheliomas. Over-expression of EZH2 tended to coincide with tumor burden, and correlated with decreased survival of patients with these neoplasms; these findings are consistent with recent studies demonstrating that over-expression of EZH2 in a variety of human malignancies including breast, lung and esophageal cancers, frequently correlates with aggressive tumor phenotypes, advanced stage of disease, and decreased patient survival (35–37). Knock-down of EZH2 or EED significantly inhibited the malignant phenotype of mesothelioma cells in vitro and in vivo. To the best of our knowledge, these studies are the first to demonstrate aberrant expression of PcG proteins in mesotheliomas, and the potential relevance of targeting PRC-2 for the treatment of these malignancies.

Our analysis revealed a spectrum of EZH2 over-expression in pleural mesotheliomas. Variability in EZH2 mRNA levels in MPM could be attributed to stromal elements, which lack EZH2 expression, as these tumors were not micro-dissected. However, pathologic evaluation confirmed >70% tumor cells in specimens submitted for analysis. More importantly, immunostaining demonstrated a range of percent and intensity of EZH2 expression in mesothelioma cells in-vivo. Furthermore, patterns of EZH2 expression in primary MPMs were retained in cell lines derived from these tumors, suggesting that differences in EZH2 expression are due to specific genetic/epigenetic factors, which vary among mesotheliomas of similar histologies. Presently, the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain unclear. The majority of MPM exhibit disruption of Rb as well as p53-mediated pathways due to allelic loss, or epigenetic silencing of p16/p14 (4, 5). A number of PcG genes including EZH2 are potential E2F targets (38). Furthermore, EZH2 expression is negatively regulated by p53 (39), as well as several microRNAs including miR-101 and miR-26a (19, 20). Our preliminary analysis indicated that miR-101 and miR-26a are down-regulated in primary MPM relative to normal pleura, suggesting that dysregulation of micro-RNAs also contributes to over-expression of EZH2 in these neoplasms. Studies are underway to delineate genetic and epigenetic mechanisms regulating EZH2 expression in normal mesothelia and MPM, and to further define the prognostic significance of EZH2 over-expression in these malignancies.

Although EED has been extensively studied in stem cells (40, 41), the role of this PRC-2 component in cancer has not been fully defined. EED is necessary for di- and tri-methylation of H3K27, and PRC-2-mediated gene silencing in murine embryonic stem cells (42). Direct binding of the WD40 domain of EED is critical for histone methyltransferase activity of the PRC-2 complex, and placement of the repressive mark H3K27Me3 in murine embryonic fibroblasts and Drosophila melanogaster embryos (43, 44). EED specifically binds to H3K27Me3, and is necessary for propagation of this repressive mark during cell division. Interestingly, the effects of EED depletion appeared to be more profound than those seen following EZH2 depletion in MPM cells. These results may simply be due to relative knock-down efficiencies; alternatively, they may could reflect compensation of EZH2 depletion by EZH1(45), and magnitude of de-stabilization of PRC-2 by loss of EED.

Originally developed as an anti-viral drug, DZNep has emerged as a novel cancer therapeutic agent (21). This nucleoside analogue induces proteolytic degradation of EZH2 and other PRC-2 components, and modest global DNA demethylation (22, 46). Tumor initiating cells appear exquisitively sensitive to DZNep due to the critical role of PcG proteins in maintenance of cancer stem cells (34). Furthermore, DZNep induces differentiation of cancer stem cells by caspase dependent degradation of NANOG and OCT4 (47). Our analysis revealed that DZNep depleted EZH2, EED, and H3K27Me3, and up-regulated several tumor suppressor genes including p21 and RASSF1A that were also activated following knock-down of EZH2 or EED in MPM cells, suggesting that the cytotoxic effects of DZNep are attributable at least in part to inhibition of PRC-2 activity. Consistent with this notion, DZNep mediated growth inhibition without apoptosis in MPM cells; similar results were observed following knock-down of EZH2 and EED in these cells. These findings are in accordance with recent observations that knock-down of EZH2 induces cellular senescence in melanoma cells in part by up-regulation of p21 (48), and delays G2/M transition without inducing apoptosis in ER-negative breast cancer cells (49).

On the other hand, our current findings do not conclusively implicate depletion of PRC-2 as the major mechanism by which DZNep inhibits the malignant phenotype of pleural mesothelioma cells. Indeed, our highly stringent microarray analysis suggests that DZNep mediates pleiotropic effects in mesotheliomas, which may vary depending on histologic subtype or genotype of these neoplasms. Studies are in progress to further evaluate genomic responses to DZNep in additional cell lines recently established from mesotheliomas of confirmed histologies. Furthermore, experiments are underway to ascertain if constitutive expression of EZH2 and/or EED abrogates DZNep-mediated cytotoxicity in MPM cells. Whereas the precise mechanisms by which DZNep mediates growth arrest in mesothelioma cells have not as yet been fully elucidated, our findings warrant further analysis of PcG protein expression in mesotheliomas, and the development of agents targeting PRC-2 expression/activity for treatment of these malignancies.

Supplementary Material

Translational Relevance.

PcG proteins have implicated in mediating stem cell pluripotency, and aggressive phenotype of a variety of human cancers. In the present study, we sought to evaluate the frequency and clinical relevance of polycomb group protein (PcG) expression in pleural mesotheliomas. Our analysis revealed that EZH2, a core component of polycomb repressor complex-2 (PRC-2) is over-expressed in the majority of pleural mesotheliomas, correlating with decreased patient survival. Inhibition of PRC-2 expression by knock-down or pharmacologic techniques significantly inhibited proliferation, migration, clonogenicity and tumorigenicity of pleura mesothelioma cells. Collectively these data demonstrate that aberrant PcG protein expression contributes to the pathogenesis of mesotheliomas, and suggest that targeting PRC-2 expression/activity may be a novel strategy for the treatment and possible prevention of these neoplasms.

References

- (1).Weiner SJ, Neragi-Miandoab S. Pathogenesis of malignant pleural mesothelioma and the role of environmental and genetic factors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2009;135:15–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kamp DW. Asbestos-induced lung diseases: an update. Transl Res 2009;153:143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zauderer MG, Krug LM. The evolution of multimodality therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2011;12:163–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Ivanov SV, Miller J, Lucito R, et al. Genomic events associated with progression of pleural malignant mesothelioma. Int J Cancer 2009;124:589–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Taniguchi T, Karnan S, Fukui T, et al. Genomic profiling of malignant pleural mesothelioma with array-based comparative genomic hybridization shows frequent non-random chromosomal alteration regions including JUN amplification on 1p32. Cancer Sci 2007;98:438–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Gee GV, Koestler DC, Christensen BC, et al. Downregulated MicroRNAs in the differential diagnosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2859–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Pass HI, Goparaju C, Ivanov S, et al. hsa-miR-29c* is linked to the prognosis of malignant pleural mesothelioma. Cancer Res 2010;70:1916–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Barbone D, Yang TM, Morgan JR, Gaudino G, Broaddus VC. Mammalian target of rapamycin contributes to the acquired apoptotic resistance of human mesothelioma multicellular spheroids. J Biol Chem 2008;283:13021–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sekido Y Molecular biology of malignant mesothelioma. Environ Health Prev Med 2008;13:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Poage GM, et al. Integrated profiling reveals a global correlation between epigenetic and genetic alterations in mesothelioma. Cancer Res 2010;70:5686–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Christensen BC, Houseman EA, Godleski JJ, et al. Epigenetic profiles distinguish pleural mesothelioma from normal pleura and predict lung asbestos burden and clinical outcome. Cancer Res 2009;69:227–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Christensen BC, Godleski JJ, Marsit CJ, et al. Asbestos exposure predicts cell cycle control gene promoter methylation in pleural mesothelioma. Carcinogenesis 2008;29:1555–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Suzuki M, Toyooka S, Shivapurkar N, et al. Aberrant methylation profile of human malignant mesotheliomas and its relationship to SV40 infection. Oncogene 2005;24:1302–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Goto Y, Shinjo K, Kondo Y, et al. Epigenetic profiles distinguish malignant pleural mesothelioma from lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res 2009;69:9073–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Sauvageau M, Sauvageau G. Polycomb group proteins: multi-faceted regulators of somatic stem cells and cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2010;7:299–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Connell ND, Rheinwald JG. Regulation of the cytoskeleton in mesothelial cells: reversible loss of keratin and increase in vimentin during rapid growth in culture. Cell 1983;34:245–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Xi S, Yang M, Tao Y, et al. Cigarette smoke induces C/EBP-beta-mediated activation of miR-31 in normal human respiratory epithelia and lung cancer cells. PLoS One 2010;5:e13764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Li Y, Bavarva JH, Wang Z, et al. HEF1, a novel target of Wnt signaling, promotes colonic cell migration and cancer progression. Oncogene 2011;30:2633–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Friedman JM, Liang G, Liu CC, et al. The putative tumor suppressor microRNA-101 modulates the cancer epigenome by repressing the polycomb group protein EZH2. Cancer Res 2009;69:2623–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Lu J, He ML, Wang L, et al. MiR-26a inhibits cell growth and tumorigenesis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma through repression of EZH2. Cancer Res 2011;71:225–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Tan J, Yang X, Zhuang L, et al. Pharmacologic disruption of Polycomb-repressive complex 2-mediated gene repression selectively induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Genes Dev 2007;21:1050–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Miranda TB, Cortez CC, Yoo CB, et al. DZNep is a global histone methylation inhibitor that reactivates developmental genes not silenced by DNA methylation. Mol Cancer Ther 2009;8:1579–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Bracken AP, Dietrich N, Pasini D, Hansen KH, Helin K. Genome-wide mapping of Polycomb target genes unravels their roles in cell fate transitions. Genes Dev 2006;20:1123–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Lee TI, Jenner RG, Boyer LA, et al. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 2006;125:301–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Series B;57, 289–300. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Christophersen NS, Helin K. Epigenetic control of embryonic stem cell fate. J Exp Med 2010;207:2287–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Sawarkar R, Paro R. Interpretation of developmental signaling at chromatin: the Polycomb perspective. Dev Cell 2010;19:651–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Mills AA. Throwing the cancer switch: reciprocal roles of polycomb and trithorax proteins. Nat Rev Cancer 2010;10:669–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Morey L, Helin K. Polycomb group protein-mediated repression of transcription. Trends Biochem Sci 2010;35:323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Eskeland R, Leeb M, Grimes GR, et al. Ring1B compacts chromatin structure and represses gene expression independent of histone ubiquitination. Mol Cell 2010;38:452–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Wei Y, Chen YH, Li LY, et al. CDK1-dependent phosphorylation of EZH2 suppresses methylation of H3K27 and promotes osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 2011;13:87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Pereira CF, Piccolo FM, Tsubouchi T, et al. ESCs require PRC2 to direct the successful reprogramming of differentiated cells toward pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell 2010;6:547–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Rizzo S, Hersey JM, Mellor P, et al. Ovarian cancer stem cell-like side populations are enriched following chemotherapy and overexpress EZH2. Mol Cancer Ther 2011;10:325–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Suva ML, Riggi N, Janiszewska M, et al. EZH2 is essential for glioblastoma cancer stem cell maintenance. Cancer Res 2009;69:9211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Collett K, Eide GE, Arnes J, et al. Expression of enhancer of zeste homologue 2 is significantly associated with increased tumor cell proliferation and is a marker of aggressive breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12(4):1168–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kikuchi J, Kinoshita I, Shimizu Y, et al. Distinctive expression of the polycomb group proteins Bmi1 polycomb ring finger oncogene and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 in nonsmall cell lung cancers and their clinical and clinicopathologic significance. Cancer 2010;116:3015–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).He LR, Liu MZ, Li BK, et al. High expression of EZH2 is associated with tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy. Int J Cancer 2010;127:138–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Bracken AP, Pasini D, Capra M, Prosperini E, Colli E, Helin K. EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. EMBO J 2003;22:5323–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Tang X, Milyavsky M, Shats I, Erez N, Goldfinger N, Rotter V. Activated p53 suppresses the histone methyltransferase EZH2 gene. Oncogene 2004;23:5759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Shibata S, Yokota T, Wutz A. Synergy of Eed and Tsix in the repression of Xist gene and X-chromosome inactivation. EMBO J 2008;27:1816–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Kalantry S, Mills KC, Yee D, Otte AP, Panning B, Magnuson T. The Polycomb group protein Eed protects the inactive X-chromosome from differentiation-induced reactivation. Nat Cell Biol 2006;8:195–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Montgomery ND, Yee D, Chen A, Kalantry S, Chamberlain SJ, Otte AP, et al. The murine polycomb group protein Eed is required for global histone H3 lysine-27 methylation. Curr Biol 2005;15:942–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Montgomery ND, Yee D, Montgomery SA, Magnuson T. Molecular and functional mapping of EED motifs required for PRC2-dependent histone methylation. J Mol Biol 2007;374:1145–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Suganuma T, Workman JL. WD40 repeats arrange histone tails for spreading of silencing. J Mol Cell Biol 2010;2:81–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Shen X, Liu Y, Hsu YJ, et al. EZH1 mediates methylation on histone H3 lysine 27 and complements EZH2 in maintaining stem cell identity and executing pluripotency. Mol Cell 2008;32:491–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Rao M, Chinnasamy N, Hong JA, et al. Inhibition of histone lysine methylation enhances cancer-testis antigen expression in lung cancer cells: implications for adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Res 2011;71:4192–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Musch T, Oz Y, Lyko F, Breiling A. Nucleoside drugs induce cellular differentiation by caspase-dependent degradation of stem cell factors. PLoS One 2010;5:e10726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Fan T, Jiang S, Chung N, et al. EZH2-dependent suppression of a cellular senescence phenotype in melanoma cells by inhibition of p21/CDKN1A expression. Mol Cancer Res 2011;9:418–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Gonzalez ME, Li X, Toy K, et al. Downregulation of EZH2 decreases growth of estrogen receptor-negative invasive breast carcinoma and requires BRCA1. Oncogene 2009;28:843–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.