Abstract

The upcoming 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) of the World Health Organization (WHO) offers a unique opportunity to improve the representation of painful disorders. For this purpose, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) has convened an interdisciplinary task force of pain specialists. Here we present the case for a reclassification of nervous system lesions or diseases associated with persistent or recurrent pain for ≥ 3 months. The new classification lists the most common conditions of peripheral neuropathic pain: trigeminal neuralgia, peripheral nerve injury, painful polyneuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and painful radiculopathy. Conditions of central neuropathic pain include pain caused by spinal cord or brain injury, post-stroke pain, and pain associated with multiple sclerosis. Diseases not explicitly mentioned in the classification are automatically captured in the residual categories of ICD-11. These conditions are either insufficiently defined or missing in the current version of the ICD despite their prevalence and clinical importance. We provide the short definitions of diagnostic entities for which we submitted more detailed content models to the WHO. Definitions and content models were established in collaboration with the Classification Committee of the IASP’s Neuropathic Pain Special Interest Group (NeuPSIG). Up to 10% of the general population experience neuropathic pain. The majority of these patients do not receive satisfactory relief with existing treatments. A precise classification of chronic neuropathic pain in ICD-11 is necessary to document adequately this public health need and the therapeutic challenges related to chronic neuropathic pain.

Keywords: Chronic pain, neuropathic pain, diagnosis, classification, International Classification of Diseases, ICD-11, World Health Organization (WHO)

1. Neuropathic pain

Lesions or diseases involving the somatosensory nervous system may paradoxically not only lead to a loss of function but also to increased pain sensitivity and spontaneous pain. This neuropathic pain is usually chronic, i.e., it either persists continuously or manifests with recurrent painful episodes. Pain may result from etiologically diverse disorders affecting the peripheral or the central nervous system. The cause can be a metabolic disease, e.g., diabetic neuropathy, a neurodegenerative, vascular or autoimmune condition, a tumor, trauma, infection, exposure to toxins or a hereditary disease. Chronic pain also occurs in neurological conditions of unknown etiology, e.g., idiopathic neuropathies.5 The mechanistic underpinnings of pain hypersensitivity and spontaneous pain in these conditions are complex, and their relationship to the underlying pathological disease process often remains unclear. On the other hand, differences in pain phenotypes offer an opportunity to distinguish pain syndromes clinically.1,9,30 Neurophysiological investigations may reveal some mechanistic clues, e.g., activity increases in somatosensory nerve fibers or changes in the endogenous control of pain.14,17 However, a lack of suitable noninvasive tests usually precludes an in-depth evaluation of active pain mechanisms in patients. Although imaging studies and quantitative sensory tests help elucidate important pathophysiological aspects of pain in patients, current knowledge of neuropathic pain mechanisms is based largely on animal models.

Chronic neuropathic pain is a major factor contributing to the global burden of disease.21 Its prevalence ranges between 6.9% and 10% of the general population.28 How strongly pain is associated with a particular neurological disease varies. Pain may be the most prominent or sole disease manifestation as, e.g., in postherpetic neuralgia, or it may occur only in a subgroup of patients with the same disease as, e.g., in chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathies. Even among patients with the same underlying cause of neuropathic pain, painful symptoms and signs usually differ.4 However, when present, neuropathic pain frequently causes major suffering and disability. Therapeutic management is challenging. Medications recommended as first-line treatments provide less than satisfactory relief in many patients.11

A suspected diagnosis of neuropathic pain requires specific investigations to ascertain that the pain originates in the nervous system. The distribution of pain must correspond to the underlying lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. The neuroanatomical relation to the underlying cause must still be recognizable even if pain is not felt in the entire innervation territory of an affected peripheral nerve or root, or the somatotopic representation corresponding to a lesion or disease of the central nervous system, or if pain extends somewhat outside these boundaries. Objective signs of a sensory disorder in the distribution of pain increase diagnostic certainty. These signs may indicate a sensory deficit or exaggerated responses to normally painful (hyperalgesia) or painless stimuli (allodynia). The definite diagnosis of neuropathic pain requires demonstration of the cause, e.g., neurophysiological tests confirming a peripheral neuropathy or imaging results showing the involvement of somatosensory fiber tracts after spinal cord injury.6,10,25 Neuropathic pain also requires specific treatment, involving both pharmacological and nonpharmacological approaches.8,11 Evidence of high or moderate quality supports the use of gabapentin, pregabalin and inhibitors of serotonin, noradrenalin uptake and tricyclic antidepressants as medications of first choice. Dermal patches releasing lidocaine or capsaicin and subcutaneous injection of botulinum toxin offer topical treatment options. Opioids should be reserved for patients not responding to therapeutic alternatives with a lower risk of adverse effects.11 Analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have no proven efficacy against pain of neuropathic origin.18,29 These particular requirements for evaluation and treatment call for an accurate representation of neuropathic pain in diagnostic classifications of the relevant clinical conditions.

2. Shortcomings of ICD-10

A structured classification of conditions associated with neuropathic pain is critically needed.12 To date, the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) is the only disease classification providing systematic coverage of neuropathic pain conditions, but these are limited to cranial nerve injuries and neuralgias.12,15

Despite its clinical and economic significance, neuropathic pain is not adequately represented in the current version of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) of the World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD is the most widely used source for diagnostic codes and the standard instrument for disease classification in clinical practice, epidemiology and health management.31 The ICD organizes diseases and clinical syndromes by etiology, affected organ or body region. In the current version of the ICD (ICD-10), painful conditions that do not fit this scheme can be classified as acute (R52.0) or chronic pain (R52.2), with a separate code for chronic “intractable” pain (R52.1). These codes can be combined with neurological diagnoses, e.g., diabetic polyneuropathy (G63.2*). The asterisk behind the code indicates a clinical syndrome in need of another etiological code, marked by a dagger. In this example, type 2 diabetes mellitus with neurological complications (E11.4†) would be a suitable specification. Thus, 3 codes are required to fully describe painful diabetic polyneuropathy, one of the most common manifestations of neuropathic pain that affects up to 30% of patients with type 2 diabetes.3

There are very few explicit references to conditions of neuropathic pain in ICD-10. They include trigeminal neuralgia (G50.0), postzoster neuralgia (G53.0* B02.2†) and phantom limb syndrome with pain (G54.6). The code for postzoster neuralgia, better known as postherpetic neuralgia, applies only if the disorder involves a cranial nerve, although thoracic nerve roots are far more commonly affected by the disease.24 Hereditary neuropathies that are predominantly characterized by painful symptoms or signs are not listed at all or incorrectly classified. For example, erythromelalgia is designated as peripheral vascular disease (I73.8), because painful episodes associated with the disease are accompanied by an erythema. A hereditary variant of the disease, in which intense pain, not reddening, is the leading symptom, remains unspecified.7

The complexity of ICD-10 codes, and the incomplete or inaccurate coverage of relevant clinical conditions, risk underreporting of chronic pain. This has practical consequences for clinicians, hospitals and other health care providers. Underreporting also hinders efficient resource management by insurers and the development of sound public health strategies by policy makers. The current epidemic of opioid abuse in North America illustrates the importance of a reliable classification of chronic pain to enable the monitoring of safe and effective analgesics use in non-cancer pain, including pain of neuropathic origin.13

3. The IASP Task Force Initiative for the Classification of Chronic Pain in the ICD

To generate a systematic and improved classification of conditions associated with clinically relevant pain and to ensure representation of these diagnoses in the upcoming revision of the ICD, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) established a Task Force that works in close cooperation with WHO representatives.27 The classification is dedicated exclusively to chronic pain syndromes, defined as persistent or recurrent pain lasting ≥ 3 months. As we have previously outlined, conditions of neuropathic pain are divided into two broad categories for peripheral or central nervous diseases. Diseases not explicitly listed in the classification will be captured in residual categories.27 During the process of drafting and editing the definitions of individual diseases and detailed content models of neuropathic pain, the Task Force conferred with the Classification Committee of the IASP’s Neuropathic Pain Special Interest Group (NeuPSIG). Content models underwent initial field testing in Australia, Germany, Japan, and Norway. Revised models were subjected to further testing on the IASP website. We will report the results of these field tests separately. Overall, diagnostic utility and specificity of the diagnostic criteria were ranked highly. A version for preparing implementation of ICD-11 was released by the WHO in June 2018.32 The complete edition will be submitted to the WHO’s Executive Board in January and the World Health Assembly in May 2019. Following endorsement, member states are expected to report health statistics according to ICD-11 from 2022 onward.

4. The classification of chronic neuropathic pain

Some conditions of persistent neuropathic pain produce distinct symptoms that would allow diagnosing chronic pain before the 3-month threshold. One example is trigeminal neuralgia, which is characterized by a pain distribution in one or more branches of the 5th cranial nerve, abrupt pain paroxysms, and provocation of these pain attacks by normally innocuous mechanical stimuli or orofacial movements. Periods of remission vary, but the neuralgia never disappears completely.6,15 Similarly, pain associated with polyneuropathy caused by type 2 diabetes or central pain after spinal cord injury usually persists so that it may seem unnecessary to wait 3 months before diagnosing chronic neuropathic pain.3,23 Nonetheless, in the absence of objective markers delineating acute and chronic phases of pain, the arbitrary definition of 3 months was chosen because it provides for clear operationalization in line with widely used research criteria and subject enrolment in analgesic treatment trials.26

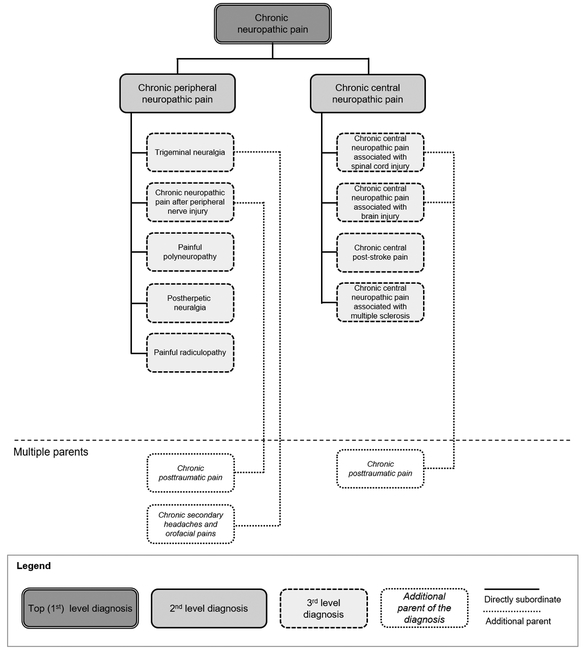

The proposed classification differentiates neuropathic pain of peripheral and central origin.16 It comprises nine common conditions associated with persistent or recurrent pain (Fig. 1 and supplementary Table 1). Short definitions of these conditions are listed below. These definitions are part of more detailed content models included in the so-called foundation layer of ICD-11. The models provide minimum criteria of possible neuropathic pain and describe investigations that support a definitive diagnosis.6,10 They also contain extension codes for pain severity (combining intensity, distress and disability), temporal characteristics and psychological or social factors,26 as well as a link to the International Classification of Functioning (ICF).19,33

Figure 1. Classification of chronic neuropathic pain in ICD-11.

Level 1 and 2 diagnoses are part of ICD-11 beta32. Specific entities of chronic neuropathic pain are included at the next level. According to the new concept of multiple parenting in ICD-11, these entities may be referred to from other divisions of the chronic pain classification, e.g., chronic posttraumatic pain or chronic secondary headaches and orofacial pains.

4.1. Chronic neuropathic pain

Chronic neuropathic pain is chronic pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system.16 The pain may be spontaneous or evoked, as an increased response to a painful stimulus (hyperalgesia) or a painful response to a normally nonpainful stimulus (allodynia). The diagnosis of chronic neuropathic pain requires a history of nervous system injury or disease and a neuroanatomically plausible distribution of the pain. Negative (e.g., decreased or loss of sensation) and positive sensory symptoms or signs (e.g., allodynia or hyperalgesia) indicating the involvement of the somatosensory nervous system must be compatible with the innervation territory of the affected nervous structure. These criteria apply to all diagnostic entities of chronic neuropathic pain.

4.1.1. Chronic peripheral neuropathic pain

Chronic peripheral neuropathic pain is chronic pain caused by a lesion or disease of the peripheral somatosensory nervous system.

4.1.1.1. Trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia is a manifestation of orofacial neuropathic pain restricted to one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve. The pain is recurrent, abrupt in onset and termination, triggered by innocuous stimuli and typically compared to an electric shock or described as shooting or stabbing. Some patients experience continuous pain between these painful paroxysms.

The diagnosis comprises idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia, classical neuralgia produced by vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve, and secondary neuralgias caused by a tumor or cyst at the cerebellopontine angle, or multiple sclerosis.6 As for other conditions of chronic neuropathic pain, the detailed content model will include a discussion of the etiology.

4.1.1.2. Chronic neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury

Chronic neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury is persistent or recurrent neuropathic pain caused by a peripheral nerve lesion. History of a plausible nerve trauma, pain onset in temporal relation to the trauma, and pain distribution within the innervation territory of a peripheral nerve (or nerves) are required for the diagnosis. Negative and positive sensory symptoms or signs must be compatible with the innervation territory of the affected nerve (or nerves). Formation of a neuroma may lead to pain at the lesion site.

Consistent with the new concept of ‘multiple parenting’ in ICD-11 (Fig. 1), the diagnosis of chronic neuropathic pain after peripheral nerve injury is also listed in the section on posttraumatic and postsurgical pain.22 However, the content model for the diagnosis is stored in the foundation layer of ICD-11. This hierarchical structure of the classification allows for multiple referencing of a content model without duplicating the diagnosis.

4.1.1.3. Painful polyneuropathy

Chronic pain occurs in polyneuropathies caused by metabolic, autoimmune, familial or infectious diseases, exposure to environmental or occupational toxins, or treatment with a neurotoxic drug. Chronic pain also occurs in polyneuropathies of unknown etiology. Pain may be the initial symptom of a neuropathy or develop over the course of the disease (Box 1). Negative and positive sensory symptoms or signs must be compatible with the anatomical distribution pattern of the polyneuropathy. Chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy is one form of painful polyneuropathy included in the classification of chronic cancer-related pain.2

Box 1. Case vignettes of chronic neuropathic pain

Chronic painful polyneuropathy

A 56-year old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus for 2 years complains about pain in the feet which started approximately 4 months ago. The pain intensity is 5 to 7 on a scale from 0 to 10. The pain may get worse at night or when she is walking. Additionally, she noticed numbness and tingling in the feet. The examination reveals a stocking-like distribution of deficits in the sense of touch. The Achilles tendon reflex is weak. An electrophysiological examination shows slow conduction in the sural and peroneal nerves. The patient has a body mass index of 30. Her fasting blood glucose concentration is 132 mg/dl, the HbA1 measures 7%. Painful polyneuropathy caused by type 2 diabetes mellitus was diagnosed. The treatment plan consisted of improved blood glucose management, medication for neuropathic pain, and foot care education.

Chronic central neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury

A 40-year-old man who 5 years ago suffered an incomplete spinal cord injury at the thoracic level reports diffuse pain in both legs. He describes an ongoing pain of burning and squeezing character as well as sensations of pins and needles. The average pain intensity is 6/10. Additionally, he sometimes experiences pain provoked by light touch. These painful sensations developed gradually over the first 6 months after the injury. On physical examination, he exhibits decreased detection of both mechanical and thermal stimuli from dermatome T4 down, hypersensitivity to cold and touch-evoked allodynia on the lower legs. The diagnosis was chronic central neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury. Following referral to a multidisciplinary center for pain therapy, he received comprehensive care including medication for neuropathic pain, physical and cognitive behavioral therapy.

4.1.1.4. Postherpetic neuralgia

Postherpetic neuralgia is defined as pain persisting for ≥ 3 months following the onset or healing of herpes zoster. The innervation territory of the first (ophthalmic) branch of the trigeminal nerve and thoracic dermatomes are the locations most frequently affected by chronic pain after herpes zoster. Postherpetic neuralgia may emerge in continuation of the acute pain associated with the skin rash or develop after a painless interval. Negative and positive sensory symptoms or signs must be compatible with the innervation territory of the affected cranial nerve or peripheral dermatome (or dermatomes).

4.1.1.5. Painful radiculopathy

Chronic painful radiculopathy is persistent or recurrent pain caused by a lesion or disease involving the cervical, thoracic, lumbar or sacral nerve roots. Degenerative changes of the spinal column including ligaments and intervertebral discs are the most frequent cause, but painful radiculopathy may also result from trauma, tumor or neoplastic meningitis, from infections, hemorrhage or ischemia, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, or from an iatrogenic lesion, e.g., during injection therapy or surgery. Pain within the affected dermatomes (radicular pain) is required for the diagnosis. The pain may be spontaneous but is typically exacerbated or provoked by taking or maintaining a certain body position, or during movement. Negative and positive sensory symptoms or signs must be compatible with the innervation territory of the affected nerve root (or roots). Musculoskeletal pain associated with painful radiculopathy should be classified separately.20

4.1.1.6. Other specified, and unspecified chronic peripheral neuropathic pain

ICD-11 will contain a residual category for other specified conditions of chronic peripheral neuropathic pain that are not covered by the disease codes listed above, e.g., chronic neuropathic pain caused by a carpal tunnel syndrome. An additional category for unspecified conditions will provide for the classification of disorders for which insufficient information is available to assign a more precise diagnosis.

4.1.2. Chronic central neuropathic pain

Chronic central neuropathic pain is chronic pain caused by a lesion or disease of the central somatosensory nervous system.

4.1.2.1. Chronic central neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury

Chronic central neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury is caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory pathways in the spinal cord. The definition of spinal cord injury comprises impairments of spinal cord function resulting from external force or a disease process. The pain may be spontaneous or evoked, as an increased response to a painful stimulus (hyperalgesia) or a painful response to a normally nonpainful stimulus (allodynia). The diagnosis requires a history of spinal cord lesion or disease and a neuroanatomically plausible distribution of the pain, i.e. pain felt in dermatomes at or below the level of injury in areas with sensory disturbance (Box 1). This cause of central neuropathic pain is also included in the classification of chronic postsurgical and posttraumatic pain.22

4.1.2.2. Chronic central neuropathic pain associated with brain injury

Chronic central neuropathic pain associated with brain injury is caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory cortex, connected brain regions or associated pathways in the brain. History of a plausible brain trauma, pain onset in temporal relation to the trauma, and a pain distribution that is neuroanatomically plausible are required for the diagnosis. Negative or positive sensory symptoms or signs indicating the involvement of the brain must be present in the body region corresponding to the brain injury. See also the classification of chronic postsurgical and posttraumatic pain.22

4.1.2.3. Chronic central post-stroke pain

Chronic central post-stroke pain is caused by a cerebrovascular lesion, infarct or hemorrhage, of the brain or brainstem. The pain may be spontaneous or evoked, as an increased response to a painful stimulus (hyperalgesia) or a painful response to a normally nonpainful stimulus (allodynia). The diagnosis of central post-stroke pain requires a history of stroke and a neuroanatomically plausible distribution of the pain, i.e. pain felt in the body region represented in the central nervous structures affected by the stroke. The pain may affect half of the body or a smaller region. Negative or positive sensory symptoms or signs indicating the involvement of the brain must be in the body region affected by the stroke.

4.1.2.4. Chronic central neuropathic pain caused by multiple sclerosis

Chronic central neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis is caused by a lesion of somatosensory brain regions or their connecting pathways. The pain may be spontaneous or evoked, as an increased response to a painful stimulus (hyperalgesia) or a painful response to a normally nonpainful stimulus (allodynia). The diagnosis requires a history of multiple sclerosis and a neuroanatomically plausible distribution of the pain. Negative or positive sensory symptoms or signs indicating the involvement of the brain or spinal cord must be present in the area of the body affected by pain. Pain primarily related to spasticity should be classified as musculoskeletal pain.20

4.1.2.5. Other specified, and unspecified chronic central neuropathic pain

Residual categories will be available for other specified or unspecified conditions of chronic central neuropathic pain.

5. Discussion

Neuropathic pain commonly persists beyond the natural healing process of the underlying disease, e. g., in postherpetic neuralgia, or despite treatment directed at the disease cause. Combining a code for the underlying disease with the explicit codiagnosis of neuropathic pain has the advantage that for the first time, patients with specific treatment needs for their pain will be distinguished from those with a painless manifestation of the same neurological disorder. While the neurological diagnosis will guide treatment of the disease that is responsible for the pain, the neuropathic pain diagnosis will provide for appropriate pain management. Different from previous editions of the ICD, the new codes for neuropathic pain will be concise and embedded in a systematic classification of chronic pain. They will cover the epidemiologically most relevant conditions and provide clear diagnostic criteria that are backed by literature references and suggestions for additional investigations to increase the level of diagnostic certainty.

ICD-11 will include cross-references to other conditions of chronic pain in separate “parent” chapters. Examples are painful chemotherapy-induced polyneuropathy, which will be mentioned under chronic cancer-related pain,2 or pain after amputation, which will be listed under chronic postsurgical and posttraumatic pain.22 Cross-referencing in ICD-11 facilitates the coding of painful disorders within the most fitting treatment-relevant category of the classification.

The proposed classification is a compromise balancing the length of this important division with those of 6 other groups of chronic pain conditions, e.g., musculoskeletal and visceral pain. Diseases not explicitly listed in the classification will be captured in residual categories for “Other specified chronic peripheral neuropathic pain” or “Other specified chronic central neuropathic pain”.

6. Summary and conclusions

The classification of chronic neuropathic pain represents the first systematic and most comprehensive classification to date of common painful neurological disorders. Precise diagnostic criteria and literature references are included in the full-content description of the disorders to minimize ambiguity. The criteria match the grading system for evidence supporting the diagnosis of neuropathic pain in clinical practice and research11. These provisions generate a valuable tool for diagnostic code assignment, appropriate allocation of health care services and the collection of epidemiological data. Clear definitions combined with a seamless evaluation of the evidence leading to the diagnosis of chronic neuropathic pain will facilitate patient identification for enrolment in clinical trials and promote the translation of research findings into practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Contributions: JS and NBF contributed equally to the manuscript. AB, WR and RDT also contributed equally. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support by the International Association for the Study of Pain and the excellent discussions with Dr. Robert Jakob of WHO.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Joachim Scholz has received research support from the Thompson Family Foundation and Acetylon, and is now an employee of Biogen. This work was completed before he joined the company. Biogen did not have a role in the design, conduct, analysis, interpretation or funding of the research related to this work. Nanna B. Finnerup has received honoraria for serving on advisory boards or speaker panels from Teva, Novartis, Astellas, Grünenthal, Mitshubishe Tanabe, Novartis and Teva. Nadine Attal has received speaker fees from Pfizer and consultant fees from Aptinyx, Grünenthal, Mundipharma, Novartis, Sanofi Pasteur, and Teva. Ralf Baron reports receiving research grants from Genzyme, Grünenthal, Mundipharma and Pfizer, and honoraria for serving on advisory boards or speakers panels from Abbvie, Allergan, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biogen, Biotest Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo, Desitin, Eisai, Galapagos NV, Genentech, Genzyme, Glenmark, Grünenthal, Kyowa Kirin, Lilly, Medtronic, Merck MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi Pasteur, Seqirus, TAD, Teva, and Vertex. He is also member of the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), a public-private partnership between the European Union and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA). Giorgio Cruccu reports grants or personal fees from Alfa Sigma, Angelini, Biogen, Mundipharma, and Pfizer. Michael First reports personal fees from Lundbeck International Neuroscience Foundation, outside the submitted work. Maria Adele Giamberardino reports personal fees from IBSA Institute Biochimique, personal fees from EPITECH Group, personal fees from Helsinn Healthcare, grants from EPITECH Group, grants from Helsinn Healthcare, outside the submitted work. Stein Kaasa reports that he is Eir solution - stockholder. Turo Nurmikko has received personal fees from Abide, Astellas, Mundipharma and Nexstim, and research grants from the Pain Relief Foundation and the National Institute of Health Research in the United Kingdom. Srinivasa N. Raja has received research grants from Medtronic, and serves in the advisory boards of Allergan, Daiichi Sankyo, and Aptinyx. Andrew S.C. Rice has received research funding from Orion, has consulted or participated in advisory boards for Imperial College Consultants, including remunerated work for Abide, Astellas, Galapagos, Lateral, Peter McNaughton from King’s College London and Cambridge University, Merck, Mitsubishi, Novartis, Orion, Pharmaleads, Quartet, and Toray. He owned share options in Spinifex from which personal benefit accrued upon the acquisition of Spinifex by Novartis, and from which future milestone payments may occur. ASCR is also named inventor on patents WO 2005/079771, EP13702262.0, and WO2013/110945. Shuu-Jiun Wang reports personal fees from Eli-Lilly, personal fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, grants and personal fees from Pfizer, Taiwan, personal fees from Eisai, personal fees from Bayer, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work. Antonia Barke reports personal fees from IASP, during the conduct of the study. Winfried Rief reports grants from IASP, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Heel, personal fees from Berlin Chemie, outside the submitted work. Rolf-Detlef Treede reports grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, Astellas, AbbVie, Bayer, personal fees from Astellas, Grünenthal, Bauerfeind, Hydra, Bayer, grants from EU, DFG, BMBF, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- [1].Baron R, Maier C, Attal N, Binder A, Bouhassira D, Cruccu G, Finnerup NB, Haanpaa M, Hansson P, Hullemann P, Jensen TS, Freynhagen R, Kennedy JD, Magerl W, Mainka T, Reimer M, Rice AS, Segerdahl M, Serra J, Sindrup S, Sommer C, Tolle T, Vollert J, Treede RD. Peripheral neuropathic pain: a mechanism-related organizing principle based on sensory profiles. Pain 2017;158:261–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bennett* MI, Kaasa* S, Barke* A, Korwisi B, Rief W, Treede R-D, The IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for ICD-11: Chronic cancer-related pain. Pain 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Callaghan BC, Cheng HT, Stables CL, Smith AL, Feldman EL. Diabetic neuropathy: clinical manifestations and current treatments. The Lancet Neurology 2012;11:521–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cavaletti G, Alberti P, Frigeni B, Piatti M, Susani E. Chemotherapy-induced neuropathy. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2011;13:180–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, Baron R, Dickenson AH, Yarnitsky D, Freeman R, Truini A, Attal N, Finnerup NB, Eccleston C, Kalso E, Bennett DL, Dworkin RH, Raja SN. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cruccu G, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, Scholz J, Sindou M, Svensson P, Treede R-D, Zakrzewska JM, Nurmikko T. Trigeminal neuralgia: New classification and diagnostic grading for practice and research. Neurol 2016;87:220–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dib-Hajj SD, Cummins TR, Black JA, Waxman SG. Sodium channels in normal and pathological pain. Ann Rev Neurosci 2010;33:325–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Kent J, Mackey SC, Raja SN, Stacey BR, Levy RM, Backonja M, Baron R, Harke H, Loeser JD, Treede RD, Turk DC, Wells CD. Interventional management of neuropathic pain: NeuPSIG recommendations. Pain 2013;154:2249–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Edwards RR, Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Angst MS, Dionne R, Freeman R, Hansson P, Haroutounian S, Arendt-Nielsen L, Attal N, Baron R, Brell J, Bujanover S, Burke LB, Carr D, Chappell AS, Cowan P, Etropolski M, Fillingim RB, Gewandter JS, Katz NP, Kopecky EA, Markman JD, Nomikos G, Porter L, Rappaport BA, Rice ASC, Scavone JM, Scholz J, Simon LS, Smith SM, Tobias J, Tockarshewsky T, Veasley C, Versavel M, Wasan AD, Wen W, Yarnitsky D. Patient phenotyping in clinical trials of chronic pain treatments: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2016;157:1851–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, Baron R, Bennett DL, Bouhassira D, Cruccu G, Freeman R, Hansson P, Nurmikko T, Raja SN, Rice AS, Serra J, Smith BH, Treede RD, Jensen TS. Neuropathic pain: An updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain 2016;157:1599–1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, Lund K, Haroutounian S, Dworkin RH, Finnerup NB, Attal N, Haroutounian S, Mcnicol E, Baron R, Dworkin RH, Gilron I, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, Kamerman PR, Lund K, Moore A, Raja SN, Rice ASC, Rowbotham M, Sena E, Siddall P, Smith BH, Wallace M. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 2015;14:162–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Finnerup NB, Scholz J, Attal N, Baron R, Haanpaa M, Hansson P, Raja SN, Rice ASC, Rief W, Rowbotham MC, Simpson DM, Treede R-D. Neuropathic pain needs systematic classification. Eur J Pain 2013;17:953–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Franklin GM. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: A position paper of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurol 2014;83:1277–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gasparotti R, Padua L, Briani C, Lauria G. New technologies for the assessment of neuropathies. Nat Rev Neurol 2017;13:203–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Headache Classification Committee. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd Edition. Cephalalgia 2018;38:1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP). Pain Terms. https//www.iasp-pain.org/terminology.

- [17].Kennedy DL, Kemp HI, Ridout D, Yarnitsky D, Rice ASC. Reliability of conditioned pain modulation: a systematic review. Pain 2016;157:2410–2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Moore RA, Chi C-C, Wiffen PJ, Derry S. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;10:CD010902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nugraha* B, Gutenbrunner* C, Barke* A, Jakob R, Karst M, Korwisi B, Schiller J, Rief W, Treede R-D, The IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Functioning properties of chronic pain. Pain 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Perrot* S, Cohen* M, Barke* A, Korwisi B, Rief W, Treede R-D, The IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic secondary musculoskeletal pain. Pain 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rice ASC, Smith BH, Blyth FM. Pain and the global burden of disease. Pain 2016;157:791–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schug* SA, Lavand’homme* P, Barke* A, Korwisi B, Rief W, Treede R-D, The IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for ICD-11: Chronic postsurgical and posttraumatic pain. Pain 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ. A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain 2003;103:249–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thyregod HG, Rowbotham MC, Peters M, Possehn J, Berro M, Petersen KL. Natural history of pain following herpes zoster. Pain 2007;128:148–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Treede R-D, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, Hansson P, Hughes R, Nurmikko T, Serra J. Neuropathic pain: Redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurol 2008;70:1630–1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Treede* R-D, Rief* W, Barke* A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, Giamberardino MA, Kaasa S, Korwisi B, Kosek E, Lavand’homme P, Nicholas M, Perrot S, Scholz J, Schug S, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JWS, Wang S-J. Chronic Pain as a symptom and a disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases ICD-11. Pain 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Treede* R-D, Rief* W, Barke* A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, Giamberardino MA, Kaasa S, Kosek E, Lavand’homme P, Nicholas M, Perrot S, Scholz J, Schug S, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JW, Wang S-J. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain 2015;156:1003–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N. Neuropathic pain in the general population: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Pain 2014;155:654–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Vo T, Rice ASC, Dworkin RH. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for neuropathic pain: how do we explain continued widespread use? Pain 2009;143:169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].von Hehn CA, Baron R, Woolf CJ. Deconstructing the neuropathic pain phenotype to reveal neural mechanisms. Neuron 2012;73:638–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].World Health Organisation. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, 2010 version. http://apps.who.int/classificationsIicd10/browse/2010/en.

- [32].World Health Organisation. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th Revision, Beta Draft. https://icd.who.int./browse11/l-m/en.

- [33].World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: WHO, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.