Abstract

We present results of retrospective real-life data of nonsquamous lung cancer patients treated in first-line (platinum-based chemotherapy with gemcitabine without bevacizumab). 56 patients with satisfactory performance status for cytotoxic chemotherapy were treated in 2010–2014. Median progression-free survival was 6.48 months (95% CI: 4.44–9.48), time to progression was 10.19 months (95% CI: 7.59–12.19). Median overall survival was 10.8 months (95% CI: 6.72–14.52). Although our group of patients had higher proportion of elderly patients with somewhat limited performance status, progression-free survival rate was comparable to large registration studies. Overall survival, despite intervening comorbidities and subsequent limited use of second-line treatment was analogous to large gemcitabine/platinum Phase III studies in nonsquamous population. We believe our data represent real-life survival rates of unselected patients with advanced NSCLC of nonsquamous type from mostly rural catchment area.

KEYWORDS : chemotherapy, first-line, NSCLC

Lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies. In the EU, standardized incidence of lung cancer is 52.5/100,000 person-years, mortality is 48.7/100,000 person-years [1]. Lung cancer can be divided into two major histopathological types; NSCLC and small-cell lung cancer. NSCLC contributes by 80% to all cases of lung cancer. NSCLC is further divided into squamous and nonsquamous cell carcinoma. Nonsquamous lung cancer consists of several histopathological subtypes; adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma being the most frequent. Mutational status of EGFR and translocation of ALK should be evaluated in advanced nonsquamous cell carcinoma as a part of initial staging. All patients with sensitizing EGFR mutations or ALK gene rearrangement should receive first-line targeted treatment with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor or ALK inhibitor, respectively [2]. According to European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines, platinum-based chemotherapy is recommended as a first-line treatment in patients with negative molecular studies (EGFR and ALK) [3]. Meta-analysis of several trials comparing outcomes of cisplatin-based regimens and carboplatin-based regimens published by Ardizonni et al. favored cisplatin over carboplatin due to better response rate (RR) and median overall survival (OS) in patients treated with cisplatin. Response rates were 30% for cisplatin and 24% for carboplatin, respectively. Median OS was 9.1 months in cisplatin group and 8.4 months in carboplatin group. Summary of the toxicity results showed comparable overall toxicity between both platinum compounds. Grade 3–4 thrombocytopenia was more common in carboplatin group and severe nausea and vomiting and grade 3–4 nephrotoxicity was more common in cisplatin group. There was no difference in neurotoxicity [4]. Other meta-analysis by Jiang et al. did not find advantage in OS with cisplatin-based regimens [5]. Hotta et al. in their meta-analysis found 11% longer survival with cisplatin based regimens only in combinations with newer, third-generation agents [6]. Therefore, it is questionable whether this small, yet significant survival benefit associated with cisplatin-based regimens is worth the treatment-related toxicity of cisplatin [7]. Gemcitabine was evaluated in two Phase III registration studies, where combination regimen with cisplatin was superior in time to progression when compared with single agent cisplatin or etoposide and cisplatin [8,9]. In the study by Sandler et al., OS benefit of combination arm was also demonstrated when compared with cisplatin monotherapy (9.0 vs 7.6 months; p = 0.008) [9].

Furthermore, Scagliotti et al. compared cisplatin/pemetrexed combination with standard cisplatin/gemcitabine in first-line treatment of NSCLC patients. OS was significantly improved in subpopulation with nonsquamous histology in cisplatin/pemetrexed arm (12.6 vs 10.4 months). Toxicity was significantly lower in pemetrexed arm. In squamous-cell subpopulation, however, OS was superior in standard, cisplatin/gemcitabine arm (10.8 vs 9.4 months) [10]. Thus, addition of third-generation drug to platinum is recommended; in nonsquamous histology, addition of pemetrexed is preferred.

Bevacizumab is monoclonal antibody against VEGF. Its effectiveness as angiogenesis inhibitor had been proven in treatment of various malignancies. According to ESMO guidelines, the addition of bevacizumab to chemotherapy (carboplatin/paclitaxel or other chemotherapy regimen) is suggested in patients with nonsquamous histology with good performance status (PS; <2) and with no contraindications [3]. The US ECOG 4599 trial showed that addition of bevacizumab to carboplatin/paclitaxel resulted in improvement of OS in patients with advanced-stage (IIIB or IV) nonsquamous cell lung cancer (12.3 vs 10.3 months; p = 0.003). Progression-free survival (PFS) and RR were significantly better in bevacizumab group. The use of bevacizumab, however, led to an increased toxicity. Fifteen patients out of 434 died due to complications associated with use of bevacizumab. Heavy bleeding was present in 4.4% of patients in bevacizumab group, comparing to 0.7% patients in control group [11]. The effect of addition of bevacizumab to cisplatin/gemcitabine followed by maintenance therapy with bevacizumab (3 weekly until progression) was studied in large randomized Phase III trial (AVAiL). Patients were randomized into three arms: control arm without bevacizumab, low-dose arm (bevacizumab 7.5 mg/kg) and high-dose arm (bevacizumab 15 mg/kg). The primary end point of trial was changed after interim analysis from OS to PFS. PFS was significantly improved in both arms with bevacizumab (6.7 months for low-dose arm, 6.5 months for high-dose arm vs 6.1 months in control arm; p = 0.003 and 0.03, respectively) [12]. OS, however, was not prolonged in bevacizumab arms (13.1, 13.6 and 13.4 months for placebo and both experimental arms, respectively). Toxicity was comparable among all three arms [13]. Meta-analysis of several trials confirmed the improvement of PFS and RR when combination of chemotherapy and bevacizumab was used as first-line chemotherapy. This meta-analysis showed, however, no improvement in OS with addition of bevacizumab when random-effects model was applied in analysis [14]. On the other hand, another meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials (RCT; AVF-0757g, JO19907, ECOG 4599 and AVAiL) by Soria et al. showed that adding bevacizumab to first-line chemotherapy was associated with significant prolongation of PFS and OS at a cost of significantly increased risk of severe proteinuria, hemorrhagia, hypertension, neutropenia and febrile neutropenia [15]. Finally, pharmacoeconomic analysis of cost–effectiveness by Goulart and Ramsey showed that bevacizumab did not appear to be cost effective when added to chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC [16].

Herein, we present results of retrospective study of first-line treatment of advanced-stage NSCLC administered at Department of Oncology at our Faculty Hospital and confront them with results of gemcitabine registration trials, Phase III trial of Schiller et al. with third-generation regimens and with control arms of RCT of Scagliotti et al. and Reck et al. The aim of our study was to describe our real-life experience with first-line treatment of advanced nonsquamous NSCLC patients who were consecutively treated using platinum/gemcitabine doublet or gemcitabine monotherapy in the past 4 years and to compare our results with results of large multicenter trials to assess the magnitude of difference in survival rates in our hospital and large centers participating in RCTs. In order to facilitate comparisons to larger randomized trials with newer regimens in nonsquamous histologies, we have chosen to study nonsquamous patients only. Patient access to third-generation drug pemetrexed is significantly delayed due to the administrative burden imposed by health insurance companies in our country. The combination of platinum and gemcitabine was thus used as standard first-line treatment for advanced nonsquamous EGFR wild-type NSCLC as it was one of the most active combination in trial of Schiller et al. [17]. Moreover, cisplatin/gemcitabine, albeit with lower dose of cisplatin (75–80 mg/m2), is commonly used as a comparator arm in European lung cancer studies [10,12,18].

Patients & methods

Patients with advanced nonsquamous NSCLC and satisfactory PS (ECOG PS 0–2) for cytotoxic chemotherapy that had been treated at the Department of Oncology at Faculty Hospital (Trencin County) from January 2010 until December 2014 were included to our retrospective study. Patients with activating mutational status of EGFR were excluded. Primary end points were PFS and OS. The results were compared with results of large registration trials of gemcitabine and several recent multicenter trials where cisplatin/gemcitabine was used as a control arm. Data were described using medians for continuous variables and frequencies for categorical variables. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used in order to assess OS, PFS and time to progression. Patients were followed by contrast-enhanced CT scans and assessed for progression using RECIST 1.1 criteria [19]. PFS was defined as time interval between first administration of first-line chemotherapy and progression or death. OS was defined as time interval between first administration of first-line chemotherapy and patient's death. Time-to-progression (TTP) was defined as time interval between first administration of first-line chemotherapy and progression or the first administration of second-line treatment. Deaths in TTP calculation were censored as cause of deaths could not be established with certainty [20,21]. MedCalc v 15.2 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Fifty-six patients with advanced stage (stage IV with pleural effusion and other stage IV) nonsquamous NSCLC met the criteria for our study. The cohort consisted of 19 women and 37 men. Median age was 65.54 years (range: 49–82). Four patients had stage IV with pleural effusion only as a sole site of dissemination and 52 patients had metastatic, stage IV disease. Following histopathological subtypes of nonsquamous NSCLC were present in our study: 38 patients had adenocarcinoma and 18 patients had large-cell carcinoma (Table 1). Gemcitabine with or without platinum was given to our patients as first-line chemotherapy regimen. Gemcitabine alone (3-weekly, 1250 mg/m2 day 1 and day 8) was administered to 4 patients with comorbidities and borderline, yet still satisfactory PS for chemotherapy; remaining 52 patients were treated with combination of platinum and gemcitabine. Carboplatin (AUC 5, day 1) and gemcitabine (1250 mg/m2 day 1 and day 8) were given to 12 patients in 3-weekly regimen, 40 patients were treated with cisplatin (75 mg/m2, day 1) and gemcitabine (1250 mg/m2 day 1 and day 8). Four cycles of chemotherapy were given to 25 patients, six cycles of chemotherapy were given to 17 patients and five cycles of chemotherapy were given to three patients. Less than four cycles were administered to 11 patients. Chemotherapy was canceled due to worsening of PS in three cases and eight patients died after first or second cycle of chemotherapy.

Table 1. . Patient demographics.

| Clinical characteristics | Variable | n (all 56 pts) | % of pts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 37 | 66 |

| Stage | IV (pleural effusion only) | 4 | 7 |

| IV | 52 | 93 | |

| Histopathological subtype | Adenocarcinoma | 38 | 68 |

| Large-cell carcinoma | 18 | 32 | |

| Performance status | ECOG PS 0 | 9 | 16 |

| ECOG PS 1 | 26 | 46 | |

| ECOG PS 2 | 21 | 38 | |

| Site of MTS† (n = all stage IV pts with distant metastases) | Lung | 30 | 58 |

| Liver | 8 | 15 | |

| Adrenal gland | 13 | 25 | |

| Bone | 7 | 13 | |

| Distant lymph nodes | 23 | 44 | |

| Brain | 7 | 14 | |

| Other | 2 | 4 | |

†21 pts had more than one site of metastatic disease.

MTS: Metastases; Pts: Patients.

Following progression of disease after first-line chemotherapy, second-line chemotherapy was given to only 19 patients (4–6 cycles, docetaxel 75 mg/m2 tri-weekly or pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 tri-weekly). Third-line chemotherapy (mostly single agent erlotinib 150 mg daily) was administered in six of 14 progressors.

Follow-up was done in two monthly intervals (history and physical examination, CT scan) until progression. Palliative radiotherapy was administered to 14 patients. Bone metastases were treated by radiotherapy in seven cases (5 × 4 Gy), brain metastases were irradiated in five cases (10 × 3 Gy) and two patients were treated by radiotherapy due to incipient superior vena cava obstruction. Linear accelerators CLINAC 2100C and 600C (Varian Medical Systems, CA, USA) were used in treatment of our patients. Radiotherapy usually followed the chemotherapy, except in patients with superior vena cava obstruction in which early local effect was desirable. Median follow-up was 34 months; 47 patients have died during this period. No autopsies were performed since most patients died at their homes. Table 2 summarizes treatment used in this study.

Table 2. . Study treatment.

| Treatment characteristics | Variable | n (all 56 pts) | % of pts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemo regimen | Gemcitabine alone | 4 | 7 |

| Carboplatin/gemcitabine | 12 | 21 | |

| Cisplatin/gemcitabine | 40 | 72 | |

| Number of cycles | Six cycles | 17 | 30 |

| Five cycles | 3 | 5 | |

| Four cycles | 25 | 45 | |

| Less than four cycles | 11 | 20 | |

| Progression after first-line treatment | 40 | 71 | |

| Treatment after progression | Second-line chemotherapy | 19 | 34 |

| Third-line chemotherapy | 6 | 11 | |

| Palliative RT† | All | 14 | 27 |

| Bone | 7 | 14 | |

| Brain | 5 | 10 | |

| Mediastinum (SVCO) | 2 | 4 | |

†Only stage IV were treated with palliative RT.

Pts: Pts; RT: Radiotherapy; SVCO: Superior vena cava obstruction.

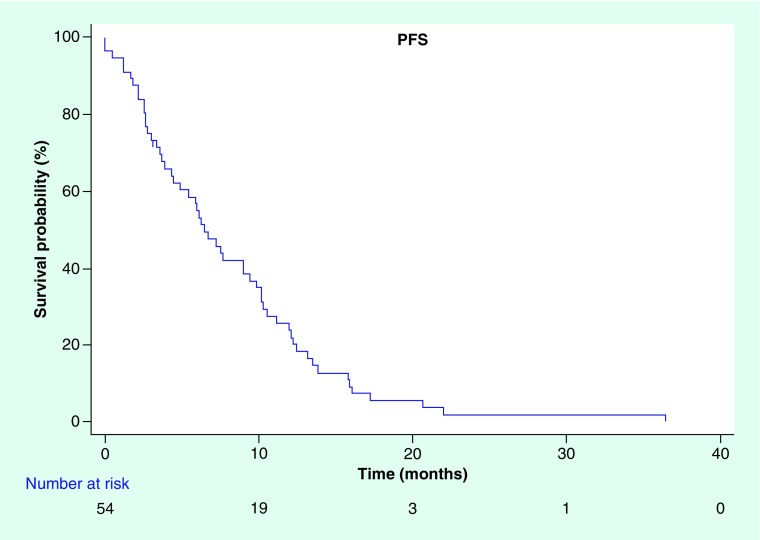

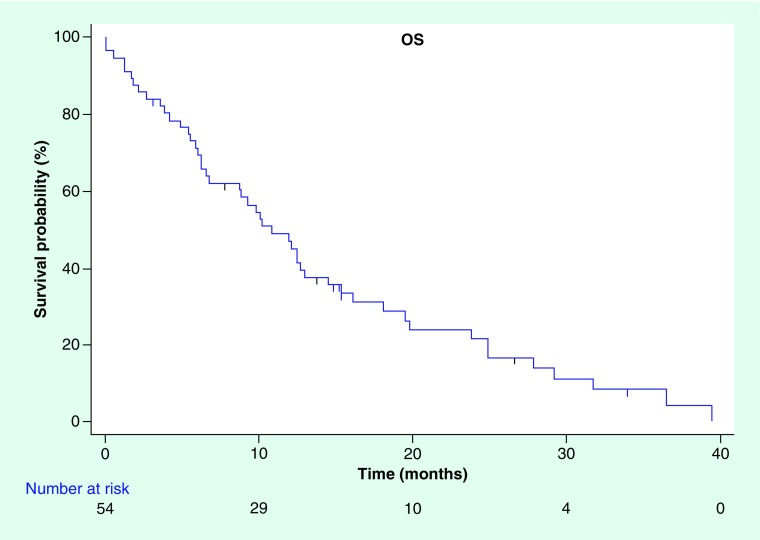

Median PFS in our cohort treated with palliative intent was 6.48 months (95% CI: 4.44–9.48) (Figure 1) and median OS was 10.8 months (95% CI: 6.72–14.52) (Figure 2). Median TTP, where deaths from any cause were censored, was 10.19 months (95% CI: 7.59–12.19).

Figure 1. . Kaplan–Meier curve for progression-free survival.

PFS: Progression-free survival.

Figure 2. . Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival.

OS: Overall survival.

Discussion

Although it is difficult to perform cross-trial comparisons, PFS in our real-life clinical practice compares with that of experimental arms in older gemcitabine registration studies and in four-arm trial of Schiller et al. Also, PFS in our cohort of patients matches performance of standard arm in recent trial of Scagliotti et al., comparing cisplatin with gemcitabine or pemetrexed and is comparable with control arm in AVAiL trial exploring addition of bevacizumab to cisplatin/gemcitabine (Table 3) [8–10,12,17].

Table 3. . Comparison between registration trials, large randomized controlled trials using cisplatin/gemcitabine as control arm and our retrospective study.

| Trial data | Cardenal et al. (all NSCLC) [8] | Sandler et al. (all NSCLC) [9] | Schiller et al. (all NSCLC) [17] | Scagliotti et al. (nonsquamous subgroup) [10] | Reck et al. (nonsquamous) [12,13] | Kohutek et al. (nonsquamous) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 69 | 260 | 288 | 634 | 347 | 56 |

| Treatment used | GEM 1250 mg/m2 D1, D8 + cisplatin 100 mg/m2 D1 3-week cycle (up to 6 cycles) | GEM 1000 mg/m2 D1, D8, D15 + cisplatin 100 mg/m2 D1 4-week cycle (up to 5 cycles) | GEM 1250 mg/m2 D1, D8 + cisplatin 75 mg/m2 D1 3-week cycle (up to 6 cycles) | GEM 1250 mg/m2 D1, D8 + cisplatin 80 mg/m2 D1 3-week cycle (up to 6 cycles) | GEM 1250 mg/m2 D1 and D8 ± cisplatin 75 mg/m2 or carboplatin AUC5 D1 3-week cycle (1–6 cycles) | |

| Median PFS (months) | 6.9 (TTP) | 5.6 (TTP) | 4.2 (TTP) | 4.7 | 6.1 | 6.48 |

| Median OS (months) | 8.7 | 9.1 | 8.1 | 10.4 | 13.1 | 10.8 |

D: Day; GEM: Gemcitabine; OS: Overall survival; PFS: Progression-free survival; PS: Performance status; TTP: Time to progression.

Despite advanced age, comorbidities and treatment of patients with PS of two, median OS in our retrospective analysis also compares favorably that of above mentioned studies exploring cisplatin/gemcitabine as experimental or reference regimen. When compared with standard arm in AVAiL trial, median OS in our retrospective analysis is numerically worse (13.1 vs 10.8 months). We feel that our OS approximates survival data from real clinical practice of unselected patients from largely rural catchment area. We try to deliver cytotoxic chemotherapy to all newly diagnosed advanced NSCLC patients with satisfactory PS (up to ECOG score 2). Nevertheless, we have witnessed early deaths on chemotherapy. Multiple sites of metastases, intervening comorbidities and just borderline performance might have contributed to these early deaths. We have analyzed our cohort also for time to progression, where deaths were censored. The difference between TTP and PFS in our study is almost 4 months. This underlines the fact that substantial part of patients suffered from life-limiting comorbidities. Due to the nature of our study, we were unable to reliably collect chemotherapy toxicity and grade it retrospectively. Second-line chemotherapy was delivered to only 34% of progressing patients, mostly due to rapid deterioration in PS. Management of NSCLC patients with PS two or advanced age remains a challenge. Recently, two randomized trials have informed treatment practice in this hard to treat patient population. A recent trial done in France had randomized 451 patients over 70 years of age to monotherapy (gemcitabine or vinorelbine) or combination of carboplatin with weekly paclitaxel. Despite increased toxicity, combination chemotherapy demonstrated improvement in median OS (10.3 vs 6.2 months; p < 0.0001) [22]. A second randomized trial primarily from Brazil randomized only patients with PS two to monotherapy with pemetrexed or combination chemotherapy with added carboplatin. Again, improved OS was demonstrated in combination arm (9.3 vs 5.3 months, p = 0.001) [23]. These data are similar to combined analysis of STELLAR trials in patients with PS two. In this analysis, several prognostic factors have emerged: low albumin, extrathoracic metastatic disease, high lactate dehydrogenase and two or more comorbidities. Presence of three or more of these risk factors abrogated benefit from combined chemotherapy in patients with PS of two. A meta-analysis of 12 trials evaluating chemotherapy in PS two patients demonstrated better OS in platinum-based combinations at a price of more hematological toxicity [24]. We have since incorporated stricter patient selection for cytotoxic chemotherapy and early palliative care in treatment of our patients.

Addition of bevacizumab to paclitaxel and carboplatin improved median PFS and OS in US study ECOG 4599, whereas addition of this anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody to cisplatin and gemcitabine statistically increased median PFS only in European AVAiL study (6.7 vs 6.1 months, i.e., 17 days; p = 0.003) without impact on median OS [11,12]. Cisplatin/pemetrexed combination has yielded more favorable efficacy and safety profile than cisplatin/gemcitabine (improvement in OS 11.8 vs 10.8; p = 0.005 in nonsquamous population) in large randomized Phase III study [10]. Recently published ESMO Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (scale from 1 to 5 where 4 and 5 mark is assigned to clinically beneficial drugs) ranked combination of carboplatin/paclitaxel and bevacizumab by two and combination of cisplatin and pemetrexed by four. This high ranking of pemetrexed doublet was due to improved toxicity profile, especially hematological toxicity [25]. Considering pharmacoeconomics and evidence-based medicine, combination therapy with pemetrexed and cisplatin seems to be more beneficial in first-line treatment of advanced lung adenocarcinoma [26].

Limitations of our study include small patient numbers and retrospective nature. However, we have included only patients which were treated with palliative intent; all patients where radiotherapy was delivered with potentially curative intent were excluded. Nevertheless, our study describes real-life data of all newly diagnosed advanced lung cancer patients with satisfactory PS for cytotoxic chemotherapy. This is underlined by a fact that median age of our patients was 66 years and more than half of them were above 65 years of age at diagnosis of advanced disease. In addition, we have treated patients with PS of two, which have been commonly excluded from large clinical trials.

Since the time period described in the study, we have started to include palliative care earlier in management of our newly diagnosed lung cancer patients. Furthermore, newly diagnosed patients with PS two who are to pursue combination chemotherapy are jointly assessed by two board-certified medical oncologists in hope to avoid toxic deaths on palliative chemotherapy.

Conclusion

PFS rates of patients treated at our hospital with platinum/gemcitabine in last 4 years are comparable to outcomes of international clinical trials utilizing the same regimen as experimental or standard arm. Although only few patients were treated by second-line chemotherapy, median OS was almost 11 months. Over the last 10 years, only modest progress has been made in the treatment of advanced lung cancer patients with no actionable mutations. Unfortunately, no predictive biomarker has so far emerged that would guide our treatment decisions. A thoughtful physician judgment together with patient wishes still remains the cornerstone of best treatment in advanced lung cancer.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

B Bystricky had received honoraria from Roche and Lilly. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Informed consent disclosure

The authors state that they have obtained verbal and written informed consent from the patient/patients for the inclusion of their medical and treatment history within this case report.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur. J. Cancer. 2013;49(6):1374–1403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCCN: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. 2016. www.nccn.org

- 3.Reck M, Popat S, Reinmuth N, et al. Metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2014;25(Suppl. 3):iii27–iii39. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ardizzoni A, Boni L, Tiseo M, et al. Cisplatin- versus carboplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: an individual patient data meta-analysis. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(11):847–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang J, Liang X, Zhou X, Huang R, Chu Z. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing carboplatin-based to cisplatin-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2007;57(3):348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hotta K, Matsuo K, Ueoka H, Kiura K, Tabata M, Tanimoto M. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing cisplatin to carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004;22(19):3852–3859. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Azzoli CG, Kris MG, Pfister DG. Cisplatin versus carboplatin for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer – an old rivalry renewed. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(11):828–829. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cardenal F, Lopez-Cabrerizo MP, Anton A, et al. Randomized Phase III study of gemcitabine-cisplatin versus etoposide-cisplatin in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999;17(1):12–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sandler AB, Nemunaitis J, Denham C, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000;18(1):122–130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, Von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26(21):3543–3551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandler A, Gray R, Perry MC, et al. Paclitaxel-carboplatin alone or with bevacizumab for non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355(24):2542–2550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reck M, Von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, et al. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27(8):1227–1234. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.5466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reck M, Von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, et al. Overall survival with cisplatin-gemcitabine and bevacizumab or placebo as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomised Phase III trial (AVAiL) Ann. Oncol. 2010;21(9):1804–1809. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botrel TE, Clark O, Clark L, Paladini L, Faleiros E, Pegoretti B. Efficacy of bevacizumab (Bev) plus chemotherapy (CT) compared with CT alone in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer. 2011;74(1):89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soria JC, Mauguen A, Reck M, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised, Phase II/III trials adding bevacizumab to platinum-based chemotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2013;24(1):20–30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goulart B, Ramsey S. A trial-based assessment of the cost-utility of bevacizumab and chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Value Health. 2011;14(6):836–845. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002;346(2):92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thatcher N, Hirsch FR, Luft AV, et al. Necitumumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin versus gemcitabine and cisplatin alone as first-line therapy in patients with stage IV squamous non-small-cell lung cancer (SQUIRE): an open-label, randomised, controlled Phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(7):763–774. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur. J. Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saad ED, Katz A. Progression-free survival and time to progression as primary end points in advanced breast cancer: often used, sometimes loosely defined. Ann. Oncol. 2009;20(3):460–464. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pazdur R. Endpoints for assessing drug activity in clinical trials. Oncologist. 2008;13(Suppl. 2):19–21. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.13-S2-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quoix E, Zalcman G, Oster JP, et al. Carboplatin and weekly paclitaxel doublet chemotherapy compared with monotherapy in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: IFCT-0501 randomised, Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;378(9796):1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60780-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zukin M, Barrios CH, Pereira JR, et al. Randomized Phase III trial of single-agent pemetrexed versus carboplatin and pemetrexed in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013;31(23):2849–2853. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morth C, Valachis A. Single-agent versus combination chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer and performance status 2: a literature-based meta-analysis of randomized studies. Lung Cancer. 2014;84(3):209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cherny NI, Sullivan R, Dafni U, et al. A standardised, generic, validated approach to stratify the magnitude of clinical benefit that can be anticipated from anti-cancer therapies: the European Society for Medical Oncology Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS) Ann. Oncol. 2015;26(8):1547–1573. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein R, Muehlenbein C, Liepa AM, Babineaux S, Wielage R, Schwartzberg L. Cost–effectiveness of pemetrexed plus cisplatin as first-line therapy for advanced nonsquamous non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009;4(11):1404–1414. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ba31e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]