Abstract

Giant Cell Tumors of Bone (GCTB) are benign but aggressive and metastatic tumors. Surgical removal cannot eradicate GCTB due to the subsequent recurrence and osteolysis. Here we developed Zoledronic acid (ZA)-loaded magnesium-strontium (Mg-Sr) alloys that can inhibit GCTB and studied the molecular and cellular mechanisms of such inhibition. We first formed a calcium phosphate (CaP) coating on the Mg-1.5 wt%Sr implants by coprecipitation and then loaded ZA on the CaP coating. We examined the response of GCTB cells to the ZA-loaded alloys. At the cellular level, the alloys not only induced apoptosis and oxidative stress of GCTB cells, and suppressed their resultant pre-osteoclast recruitment, but also inhibited their migration. At the molecular level, the alloys could significantly activate the mitochondrial path-way and inhibit the NF-кB pathway in the GCTB cells. These collectively enable the ZA-loaded alloys to suppress GCTB cell growth and osteolysis, and thus improve our understanding of the materials-induced tumor inhibition. Our study shows that ZA-loaded alloys could be a potential implant in repairing the bone defects after tumor removal in GCTB therapy.

Keywords: Magnesium-strontium alloys, CaP coating, Zoledronic acid, Giant cell tumors of bone, Mechanisms

1. Introduction

Giant Cell Tumors of Bone (GCTB) are benign tumors in bone with unpredictable behaviors, and accounts for 20% of benign bone tumors [1]. Although defined as benign, they are aggressive, induce highly osteolytic defects, destruct bone, and cause gradual swelling around the joints [2]. The risk factors also include deformity, pathologic fracture and high proclivity for local recurrence at the tumor site, as well as sporadic metastasis to the lungs [3]. Surgical excision is the universal standard and most effective for treating GCTB. How-ever, the resection extension is often controversial. Wide resection gives rise to surgical complications as well as functional impairment, making the reconstruction necessary [4]. Intralesional curettage currently seems to be the mainstay of GCTB treatment, especially for tumors classified as Campanacci grade I or II [5]. How-ever, the reported local recurrence rates reach 27% to 65% in the first 2–3 years following primary surgical treatments [6].

A bisphosphonate, zoledronic acid (ZA, Fig. 1), could limit GCTB progression by targeting osteoclast like giant cells, and inhibit the activity of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are contributory for tumor invasion and migration [7,8]. Additionally, implanting a material into the defect after tumor removal is an approach to repairing defects. The traditional methods of reconstruction include cementation or bone grafts which having their advantages and disadvantages. For example, the bone cement could cause local cytotoxicity and unknown long-term effects around the subchondral region [9,10]. Obviously, bone substitutes with osteoinduction ability and preferably bioresorbable properties are more ideal for defects filling following removal of GCTB. Although there are a series of biomaterials used for the purpose of bone grafting based on calcium phosphate, how to optimize the properties of biomaterials for bone reconstruction, such as structural support, osteogenic potential and degradation rate, is still a large problem for clinical use [11]. Recently, Mg and its alloys are emerging bone implant materials because they have a combined advantage of biodegradability, promoting bone development, and good mechanical properties [12]. They have been used in clinical applications as evidenced in the Mg-based products such as MAGNEZIX® compression screw (CE-approved) and K-MET Mg screw (Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety-approved) [13,14]. Our previous study also showed that Mg-1.5 wt%Sr alloys exhibited better biocompatibility, degradation and mechanical properties than other commercial bone substitutes (hydroxyapatite, tricalcium phosphate and CaSO4) [15].

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of zoledronic acid.

In order to integrate the advantage of Mg alloys as bone substitutes and the advantage of ZA as a tumor-inhibiting molecule, we developed an Mg-1.5 wt%Sr alloy loaded with novel ZA coating and investigated whether local delivery of ZA from the Mg based bone substitutes might be effective for local adjuvant treatment of GCTB (Fig. 2). To assist the ZA loading onto the Mg alloys from ZA solution, we introduced a CaP coating on the Mg alloys first, and then studied the ZA release kinetics. We further used a variety of molecular and cellular assay to evaluate the response of GCTB to the ZA-loaded Mg alloys in order to reveal the mechanisms by which the alloys inhibit GCTB.

Fig. 2.

Coating of ZA-loaded CaP on Mg-based alloys that can serve as a potential implant to repair the defects after the GCTB tumor removal (top) and the possible signaling pathway (bottom) for the alloys to cause GCTB cell death and inhibit GCTB cell growth.

2. Results

2.1. Materials characterization of the ZA loaded Mg-Sr alloy

After CaP was deposited on the surface of Mg-Sr alloys, the resultant coatings were uniform and the substrate was covered with radially oriented needle-like crystals (Fig. 3A (a)). When incorporated with 10‒2 M ZA, spicule crystals grew on the CaP layer (Fig. 3A (b)). Comparatively, at a low ZA concentration (10‒3 and 10‒4 M), ZA did not influence the CaP morphology. The corresponding energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) spectra (Fig. 3B) showed the distributions of the main elements including Ca, P, O, and Mg (point a). The molar ratio of Ca/P for the CaP coating is about 1.0 (point a-1 and point a-2). After incorporating ZA, the Ca/P ratio of the spicule crystallites (point b-1 and point b-2) varied from that of the blocky CaP deposition (point b-3), showing a significant decrease in atomic percent of Ca. Thus, the modification in the morphology of the CaP coating was probably due to a partial dissolution of the CaP layer in the presence of ZA solutions (by calcium depletion), followed by re-precipitation of CaP under new conditions of the bulk solution phase. Moreover, there was no difference in the thickness of coatings with or without ZA (about 20 µm) from the cross-section image (Fig. 4A). However, the coating and substrate were well combined in the ZA loaded group, and the coating was dense and compact compared with Ca-P coating without ZA incorporation.

Fig. 3.

Characterization of the ZA-loaded CaP coated Mg-Sr alloys. (A) SEM micrographs performed on the CaP coating grown on the surface of Mg-Sr alloys (a) before and (b, c, d) after the treatment with 10‒2, 10‒3, and 10‒4 M of ZA. (B) The corresponding elemental compositions of coatings by EDS.

Fig. 4.

Characterization of the ZA-loaded CaP coating on the Mg-Sr alloys. (A) Cross-section morphologies of coatings on the surface of Mg-Sr alloys (a) before and (b, c, d) after the treatment with 10‒2, 10‒3, and 10‒4 M of ZA. (B) XRD spectra of different concentrations of ZA loaded CaP coating. ZA powder was set as reference. (C) FTIR-ATR spectra of ZA loaded CaP coating. ZA powder was set as reference.

Fig. 4B showed the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the CaP coating before and after incorporated with ZA at different concentrations. The characteristic broad peaks of CaP coating diffraction profile were detected at 2h = 11.6°, 20.7°, 23.4°, and 29.2°, indicating the existence of brushite (CaHPO4 2H2O) (JCPDS 11-0293). The characteristic peaks of Mg also appeared in this profile. After ZA was incorporated into the CaP coatings at low doses of 10‒3 and 10‒4 M, similar XRD profiles were obtained. Comparatively, a significant peak was detected for the coating at a concentration of 10‒2 M (ZA2 coating) and can be assigned to ZA. Fig. 4C showed the FTIR spectra performed on the coating before and after incorporation of ZA at the highest concentrations of ZA. The presence of ZA could be detected and identified at characteristic bands of 987 cm‒1 (ν P-OH), 1062 cm‒1 (νP=O), 1577–1650 cm‒1 (νC=N), 1450 cm‒1 (νC=C), and 3160 and 3488 cm‒1 (νO=H) in ZA loaded coating according to a reference of pure ZA powder.

2.2. Degradation and ZA release

The pH curves during 14 days of implant immersion in Hank’s solution were shown in Fig. 5A. The pH value of bare Mg-Sr alloys increased quickly on the first day, and maintained at the highest alkaline pH value of about 10.5 during the immersion period. The pH variation for the coating without and with ZA loading was similar, keeping at approximately 8. The pH value of the CaP coating was lower than that of the ZA loaded CaP coatings during the first 7 days. The pH values were increased with an increase in the loaded ZA concentration. Corrosion was evaluated in terms of weight loss after cleaning by chromic acid solution and illustrated with respect to the original weights in Fig. 5(B and C). The weight loss percentage of CaP coating displayed a slow corrosion with the immersion time, with only 0.35% of weight loss during 14 days of immersion, indicating better corrosion resistance. After the ZA loading, the coatings showed lower weight loss during the immersion period except for the 7th day, however, no significant difference (p>0.05) was identified between CaP coatings with and without ZA coating. Fig. 5D presents the release of ZA from Mg-1.5Sr alloys determined by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). The calibration curve was linear when the ZA concentration ranged from 0.2 to 500 µg/mL (R2 greater than 0.999). The release of ZA in ZA-2 coating group increased continually until day 7. However, the release of the ZA in ZA-3 and ZA-4 coated group reached the highest value within the first day and then reduced during the next two days until a plateau was found after 4 days. The highest amount of cumulative release of ZA reached 8.510 mg/mL (29 mM) and 2.485 mg/mL (8.56 µM) for the ZA-3 and ZA-4 coated group, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Characterization of the corrosion rate and ZA release of the Mg-Sr alloys. (A) pH change during the immersion of the Mg-Sr alloys in Hank’s solution. (B, C) Weight loss of the Ca-P coatings before (B) and after (C) incorporating ZA during immersion in Hank’s solution for 14 days. (D) Cumulative amount of ZA released from Mg-Sr alloys after 1 to 7 days and determined by HPLC.

2.3. Hemocompatibility

Our results of hemolytic test were summarized in Fig. 6A. Normal saline and deionized water was set as the negative control and positive control, respectively. Positive control caused hemolysis and showed a red solution in the tube due to the presence of released hemoglobin. All of our ZA2-, ZA3-, ZA4-loaded and CaP-coated alloys, as well as the negative control showed no red color, indicating that no hemolysis of human red blood cells had occurred.

Fig. 6.

ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloy suppressed GCTB cells growth and hemocompatibility. (A) Hemolysis tests of the Mg-Sr alloys. The insets are the positive control, negative control, ZA2-, ZA3-, ZA4-, and CaP coated Mg-1.5%Sr alloys from the left to the right, respectively. The results of hemolysis ratio (HR) indicated that all of our alloys were not hemolytic to human red blood cells. (B) Cell proliferation measured by colorimetric CCK-8 assay. Tumor cells cultured in the extracts medium of ZA2 coating and ZA3 coating alloys had significantly lower absorbance than others on day 1, 3 and 7. (C) Cytotoxic response measured by LDH assay. Tumor cells in ZA coating alloys released more LDH into the media than others. (D) DNA contents measured with Cyquant cell proliferation assay kit. The DNA level was significantly lower in tumor cells treated with ZA2 and ZA3 coated alloys for 24 h. (E) Cell viability conducted by Live/Dead staining kit. A large number of dead tumor cells with red fluorescence were visible in ZA2 coated group. All data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. #: p < 0.05 and ##: p < 0.01 compared with ZA3 coating. *: p < 0.05 and **: p < 0.01 compared with ZA2 coating. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.4. GCTB cell growth suppression

To understand how ZA released from Mg-Sr alloys influenced the proliferation of GCTB cells, CCK-8 assay was performed. The cells cultured in the extracts from ZA2 and ZA3 loaded alloys had a significantly lower absorbance (Fig. 6B) than the ZA4 loaded alloys, CaP coated alloys, and blank control from 1 to 7 days (p < 0.01). However, cell growth of ZA4 and CaP group is not significantly different from that of the control group. The absorbance value of all the groups, except for the ZA2 group, was elevated during the cultivation, suggesting that the cell numbers were increasing, but at a higher rate on CaP coatings without or with low concentrations of ZA.

LDH was adopted to indicate the cellular damage in the study of cytotoxicity. The results in Fig. 6C showed that the cells cultured in the extracts from ZA-loaded alloys released more LDH into the media than the other groups (p < 0.01), and the cytotoxicity of the ZA2-loaded group reached 553% with respect to the blank con-trol, indicating the serious destruction of tumor cell integrity caused by the ZA released from Mg alloys.

DNA content of the cells was measured by a proprietary Cyquant GR dye. Fig. 6D showed that the DNA level was much lower in the tumor cells treated with ZA2 and ZA3 loaded alloys extracts for 24 h (p < 0.01), consistent with the cell proliferation data and demonstrating the genotoxicity of ZA to tumor cells.

Calcein AM can penetrate viable cells to make the cells fluoresce green and Ethidium homodimer-1 (EthD-1) could stain necrotic and late apoptotic cells to make the cells fluoresce red. Consistent with the cell proliferation assay, Fig. 6E showed the absence of dead cells but the even spreading of the cells (green) in ZA4-loaded and CaP coated group. However, live cells in ZA2 and ZA3 loaded group were slightly fewer, and a large number of dead tumor cells (red) were visible in ZA2-loaded group. These in vitro tests demonstrated that the ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys remarkably suppressed GCTB cell growth.

2.5. GCTB cytoskeleton organization interference

The characterization of focal adhesion (FA) and actin cytoskeleton could assist us to understand the effect of materials on the cell adhesion [16,17]. The expression of vinculin, which links integrin and actin cytoskeleton, was detected to identify FA contacts. The vinculin-actin-nucleus tricolor staining fluorescence images (Fig. 7) showed that the vinculin denoted FA contacts cannot be observed in the cells on the ZA2-loaded Mg alloys, but a little vinculin was visible in the cells on the ZA3-loaded Mg alloys. However, FA contacts were distributed over the peripheral and central regions of the cells on the ZA4-loaded and CaP-coated Mg alloys, indicating that the cells only bound well on the Mg alloys loaded with a lower dose of ZA or CaP coating. In addition, worse and thinner organized filamentous actin bundles, and significantly smaller areas of the tumor cells were observed in the ZA2 and ZA3-loaded Mg alloys than in the ZA4-loaded and CaP-coated Mg alloys. Overall, little focal adhesion and poor cytoskeleton organization indicated unfavorable adhesion and spreading properties of GCTB cells exposed to specified ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys.

Fig. 7.

Vinculin (green), actin (red), and cell nucleus (blue) fluorescence images of GCTB cells cultured on Mg-Sr alloys. Little focal adhesion and poor cytoskeleton organization indicated unfavorable adhering and spreading properties of GCTB cells exposed to specified ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.6. Oxidative stress of GCTB

The intracellular oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) formation after the cells treated with ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys extracts were monitored using 2′,7′ -dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). The DCFH-DA would be converted into green fluorescent 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescin (DCF) in the presence of ROS. Both the fluorescence microscopy images and the flow cytometry analysis clearly showed that a low level of DCF (Fig. 8), corresponding to a low ROS level, was detected in the groups of CaP-coated Mg alloys and blank control. However, tumor cells exposed to ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys exhibited significantly more ROS as well as a dose-dependent increase in the ROS production and oxidative stress with respect to the blank control (p < 0.01). The results indicate greater damage to the cellular machinery such as DNA, lipids, mitochondria, and cellular proteins when a higher dose of ZA is loaded on the alloys.

Fig. 8.

ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys enhanced ROS generation in GCTB. (A-B) Fluorescence microscopy images (A) and flow cytometry (B) of tumor cells stained with DCFH-DA. (C) mean fluorescence intensity of the flow cytometer results. Tumor cells exposed to ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloy exhibited a dose-dependent increase in oxidative stress. Data were collected from three independent experiments. #: p < 0.05 and ##: p < 0.01 compared with ZA3 coating. *: p < 0.05 and **: p < 0.01 compared with ZA2 coating.

2.7. Mitochondria-dependent apoptosis of GCTB

Both Annexin V-FITC and 7-AAD could be used as probes to quantify the apoptotic cells through flow cytometry. In the flow cytometry (Fig. 9A), Annexin V-positive and 7-AAD-positive cells indicate the cells undergoing necrosis whereas the Annexin V-positive and 7-AAD-negative cells represent those undergoing the apoptosis. Fig. 9A showed that the percent of healthy cells were greater than 85% in the groups of the CaP-coated Mg alloys and the blank control. However, increasing the concentration of ZA loaded on the Mg alloys from 10‒2 to 10‒4 M caused a dramatic increase in the quantity of early apoptotic cells (from 0.9% to 9.9%) and necrotic cells (from 3.9% to 28%), as well as a decrease in the cell viability (from 87.1% to 53.9%). These results confirmed that ZA selectively and strongly induced apoptosis and necrosis in GCTB cells.

Fig. 9.

ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys induced mitochondria-dependent apoptosis of GCTB. (A) ZA2- and ZA3-loaded Mg-Sr alloys induced tumor cells apoptosis and necrosis, which was verified by Annexin V-FITC/7-AAD double staining and flow cytometry. Quantification of apoptotic cells (lower right) was shown. (B) ZA2- and ZA3-loaded Mg-Sr alloys decreased mitochondrial membrane potential (Dwm) and induced mitochondrial dysfunction by JC-1 staining and flow cytometry. (C) ZA2- and ZA3-loaded Mg-Sr alloys increased the expression of Bax, p53 proteins, the cleavage of caspase-3, and the release of cytochrome c. All data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. #: p < 0.05 and ##: p < 0.01 compared with ZA3 coating. *: p < 0.05 and **: p < 0.01 compared with ZA2 coating.

Mitochondrial dysfunction is involved in regulating apoptosis. When the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) is lost, mitochondrial damage occurs, and then cytochrome c is released into the cytosol [18]. JC-1 dye could accumulate in the healthy mitochondria and leak out when the mitochondrial membrane integrity is compromised. Therefore, the decrease in Δψm can be represented by the increase in the green fluorescence. Our data indicated that the Δψm of ZA4-loaded and CaP-coated groups did not decrease compared to the blank control, however, a significant decrease in Δψm with a high fluorescence intensity was observed in GCTB cells treated with ZA2- and ZA3-loaded Mg-Sr alloys extracts (Fig. 9B), confirming that the induction of apoptosis was mediated through the mitochondrial dysfunction.

To further determine the underlying molecular signaling pathway of apoptosis, we used Western blot to characterize the production of apoptosis-related proteins. The combined loading of ZA2 and CaP on the Mg-Sr alloys induced the suppression of Bcl-2 and induction of Bax, as well as the increase of p53 and caspase-3 (Fig. 9C). In addition, ZA2 loading led to an obvious upregulation in the caspase-3 at 19 kDa, and caused the cytochrome c to be released from mitochondria. Taken together, these results all indicated that ZA-loaded Mg alloys can synergize the local adjuvant therapy for GCTB by inducing cell apoptosis through the mitochondrial pathway.

2.8. GCTB cells migration reduction

The in vitro wound healing assay was employed to perceive the migration behavior of tumor cells. Fig. 10 showed the wound healing activity and the migration ratio of the GCTB cells after the cells were treated with Mg alloys extracts at different time intervals. It can be clearly visualized that ZA-loaded Mg alloys significantly inhibited cell migration and ZA2 loading exhibited the slowest migratory rate. However, the CaP-coated group and the blank control had no helpful effect on the GCTB cells migration. GCTB cells secrete various factors to stimulate osteolysis and promote tumor metastasis. We chose matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9), MMP-13, and E-cadherin, as the representative molecular mediators of tumor metastasis for further real-time PCR (RT-PCR) investigation. These genes were clearly decreased in the tumor cells that were interacted with ZA2- and ZA3-loaded Mg alloys as illustrated in Fig. 10C. These data indicated that the ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys can arrest GCTB cell migration through the down-regulation of metastasis-related genes.

Fig. 10.

ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloy reduced migration of GCTB. (A) Migration images of tumor cells mediated by ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloy at 0 and 24 h. The scale bar represents 100 lm. (B) The migration ratio which represents the ratio of migration distance to the originally wounded distance. (C) mRNA expression level of MMP-9, MMP-13, and E-cadherin genes in GCTB cell lysates. These data indicated that ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys could arrest tumor cell migration by down-regulating the mRNA expression of metastasis-related genes. All data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. #: p < 0.05 and ##: p < 0.01 compared with ZA3 coating. *: p < 0.05 and **: p < 0.01 compared with ZA2 coating.

2.9. GCTB-induced recruitment of pre-osteoclasts abrogation

Tumor cells could recruit osteoclast-like giant cells and the precursor cells into GCTB, which further drives tumor progression and osteolysis. Therefore, we examined the effect of ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys extracts on the migration of pre-osteoclasts attracted by GCTB through in vitro giant cell formation models using the Transwell migration assay (Fig. 11A). Our results showed that GCTB cells strikingly attracted the pre-osteoclasts, and ZA could inhibit GCTB-attracted pre-osteoclasts migration in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 11B). The osteolysis of GCTB is mediated by genes such as nuclear factor of activated T-cells cytoplasmic 1 (NFATc1), Receptor Activator for Nuclear Factor-jB Ligand (RANKL), central transcriptional factor in osteoclastogenesis (c-fos), tartrateresistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), Cathepsin K (CTSK), and parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP). To reveal the molecular mechanisms for the ZA-loaded alloys to inhibit osteolysis, we characterized the mRNA expression level of these genes. Our data indicated that ZA2- and ZA3-loading significantly down-regulated the mRNA expressions of all these genes (Fig. 11C). These results suggested that ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys specifically abrogated GCTB cells-induced pre-osteoclasts migration through suppressing the expression of osteoclastogenesis-related marker genes.

Fig. 11.

Specific inhibitory effect of ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys on GCTB-induced pre-osteoclasts recruitment. (A) Schematic representation of the experiment. (B) Migrated pre-osteoclasts were stained, photographed, and the percent of invaded cells was calculated. The migration of pre-osteoclasts was specifically abrogated by ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys but ignored in CaP coating and blank control group. The scale bar represents 200 µm. (C) ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys suppressed osteoclastgenesis-related gene expression dose dependently. All data represent the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. #: p < 0.05 and ##: p < 0.01 compared with ZA3 coating. *: p < 0.05 and **: p < 0.01 compared with ZA2 coating.

2.10. NF-кB signaling pathway inhibition

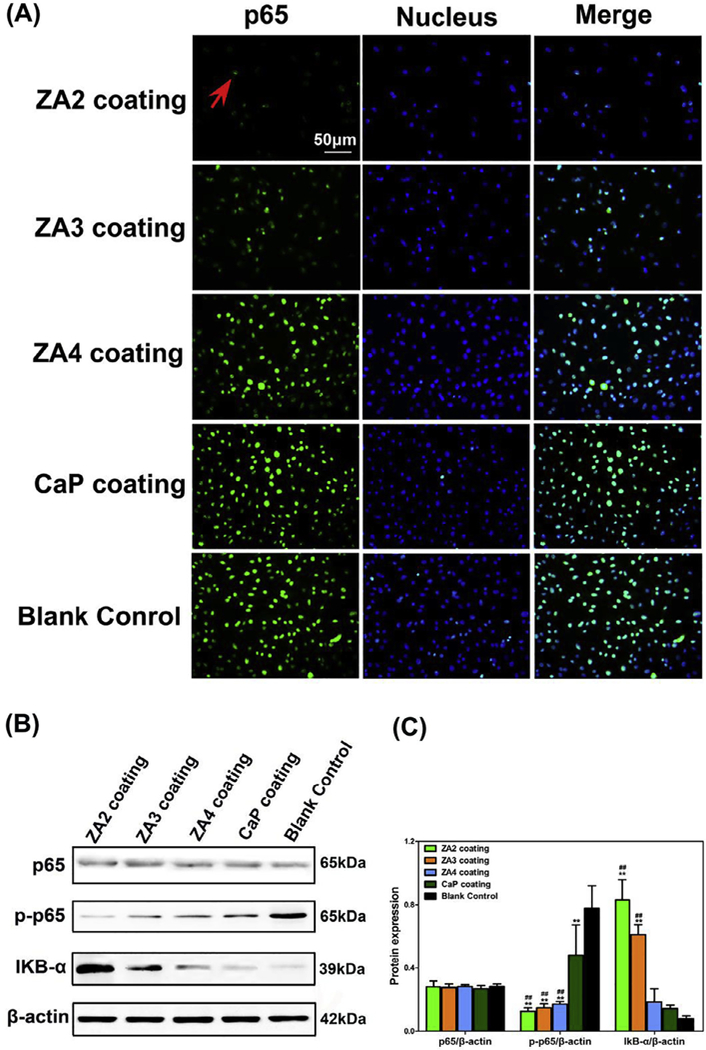

We further investigated whether ZA inhibited the NF-кB signaling pathway, which was significantly activated in primary GCTB, using two different approaches. NF-кB signaling pathway would be activated once NF-кB /Rel complexes were freed by IкB proteins and then translocated from the cytosol to the nucleus. Afterwards, target gene expression was induced. First, we found that ZA-loaded Mg alloys abrogated the nuclear translocation of p65 in a dose dependent manner using immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 12A). Second, we verified that ZA-loaded Mg alloys could significantly inhibit the phosphorylation of p65 and degradation of IкB-α in a concentration- dependent manner by Western blot analysis (p < 0.01, Fig. 12B, C). Overall, our results showed that ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys inhibited the activation of NF-кB signaling pathway in GCTB.

Fig. 12.

The activation of NF-кB signaling was prevented by the pretreatment of ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys in GCTB cells. (A) Tumor Cells were incubated with p65 antibody and Alexa 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, and nuclei were stained with DAPI. The nuclear translocation of p65 (indicated by cyan fluorescence and red arrow) was dose dependently abrogated by ZA-loaded Mg alloys. (B-C) Western blotting assay (B) of p65, p-p65 and IкB-α proteins and the corresponding histogram (C) of protein expression level. These data showed that ZA2- and ZA3-loaded Mg alloys significantly inhibited the degradation of IкB-α and the phosphorylation of p65. The bands of β-actin protein were loading controls. #: p < 0.05 and ##: p < 0.01 compared with CaP coating. *: p < 0.05 and **: p < 0.01 compared with Blank control. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3. Discussion

GCTB is an aggressive bone tumor that can cause osteolysis, become malignant and still show high recurrence rates. Significant osteolysis causes severe pain and even pathological fracture in GCTB patients, which brings great distress to patients and increases the difficulty of clinical treatment. Even adjuvants thera-pies are adopted, including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or embolization, in combination with the intralesionly surgery, the recurrence rates do not improve significantly [19].

Bisphosphonates, such as ZA, could be used to treat GCTB through encouraging both stromal cells and multinucleated giant cells to undergo death. However, extensive use may lead to side effects such as gastrointestinal irritation, jaw osteonecrosis, hypocalcemia, and inflammatory eye disorders [20,21]. Otto et al. indicated that bisphosphonates exhibited a pH-dependent cellular toxicity [22]. The acidification of extracellular microenvironment under tumorous conditions may result in the inhibition of immune function and the promotion of tumor cells migration [23], as well as a great release of bisphosphonates to the bone matrix. As a result, the toxicity to mesenchymal cells and soft tissues was increased [24–26]. Based on this, an alkaline environment may inhibit ZA-related osteonecrosis. It has been reported that Mg based metals with excellent biocompatibility and osteogenesis functions have obvious cytotoxicity on bone tumors by generating an alkaline environment [27–29]. Therefore, Mg based implants have the potential to be applied as bone tumor prosthesis in the clinical practice to neutralize the tumor-associated acidic microenvironment. Additionally, bisphosphonates have a marked affinity to CaP, which led to our decision to utilize ZA-loaded CaP coating on the Mg-Sr substitutes for local administration with GCTB. In this study, for the first time, we discovered a local adjuvant therapy effect of ZA-loaded Mg alloys on GCTB. The release profiles of ZA obtained by HPLC were in agreement with the cell response to ZA. We also found that ZA coatings still possess a satisfactory cor-rosion resistance for orthopedic applications.

Tumor cells have an imbalanced redox status, so they are more sensitive to the agents that further increase the oxidative stress compared to their normal counterparts [30,31]. Therefore, synergistic ROS-dependent cytotoxicity of combination therapies is cancer cell specific. In this study, we confirmed the oxidative stress of GCTB cells occurred in response to the treatment of ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys. ROS may further induce a number of physiological events such as DNA damage and genetic instability, or new ROS stress response [32]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that p53 could also induce the response of the cancer cells to the DNA damage and apoptosis resulting from the ROS production [33]. These conclusions were consistent with our results in Figs. 6D and 9C. ROS could be formed in the cells as a result of oxidative phosphorylation in the mitochondria and excessive ROS production can induce apoptotic cell death, meaning that ROS generation is probably the upstream regulator of apoptosis [34].

As one of the signal transduction pathway for the apoptosis, the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is generally triggered by activating pro-Bcl-2 family proteins. The proteins are transferred to the mitochondria and modify the permeability of mitochondrial outer membranes, making cytochrome c released into cytoplasm and caspases cleaved and activated [18,35]. Ultimately, cascade reaction caused the mitochondrial membrane potential to be lost and downstream events of apoptosis to occur [36]. We observed that exposure to ZA-loaded Mg alloys resulted in the up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax and the down-regulation of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (Fig. 9C), as well as break down in the integrity of mitochondrial membrane when cells were challenged with oxidative stress. The Bcl-2/Bax ratio was modified and caspase-3 was activated, leading to the intrinsic cell death pathway [37].

The stromal cells of GCTB could promote tumor development by recruiting monocytes and promoting osteoclast formation, therefore, inhibiting bone resorption would decrease the GCTB recurrence rate [38]. Such osteoclastgenesis is mediated by many genes, such as RANKL, which is directly involved in the osteoclast-induced bone resorption. When RANKL is bound to its receptor RANK, it will recruit TNF receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) in the physiological environment [39]. The resultant RANK-TRAFs complex would activate several downstream signaling cascades, including the NFATc1 and c-fos, as well as multiple osteoclastogenesis-related genes, including TRAP, MMP-9 and CTSK [40]. Here the expression of NFATc1/c-fos pathway, induced by RANKL, was down-regulated in GCTB stromal cells (Fig. 11C), which indicated that the osteoclastogenesis was distinctly arrested in the treatment process of ZA-loaded Mg alloys as a local adjuvant therapy followed by intralesional curettage.

Numerous factors have been implicated in tumor invasion, metastasis, and clinical prognosis through degrading collagen [41]. For instance, the over-expression of MMP-9 promotes vascular invasion and is closely related to the bone destruction and metastasis of GCTB. MMP-13 is able to degrade interstitial collagen during tumor invasion and metastasis, and stimulate osteoclast differentiation [42]. RANKL expression is closely related to epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and PTHrP could regulate bone development and mineral homeostasis by enhancing the production of RANKL and MMP-13 [43]. Therefore, the MMP and RANKL-RANK system may be responsible for the risk of metastasis in GCTB. It is reasonable to speculate that ZA-loaded Mg alloys have an excellent effect on controlling the recurrence and metasta-sis of GCTB from our RT-PCR results.

We further studied the signaling pathway about the treatment and prophylactic effects of our novel ZA-loaded implants on GCTB. NF-кB family serves an integral role in the survival of many solid tumors, often allowing them to metastasize and develop chemo-resistance to the treatment [44]. Some studies have also proposed the role for oxidative stress in regulating NF-кB signaling pathway and its participation in carcinogenesis including GCTB [45]. NF-кB activation can be achieved through the degradation of small IкB proteins and the nuclear translocation of p65 subunit, which leads to genetic alterations of tumors [46,47]. Our results showed that ZA-loaded Mg alloy could significantly inhibit the activation of NF-кB signaling by decreasing the tyrosine phosphorylation and suppressing nuclear translocation of p65/NF-кB. These discoveries strongly confirm that NF-кB translocation was necessary for the therapy mediated by ZA-loaded Mg alloys.

4. Conclusion

In this work, we demonstrate that an alkaline environment generated by Mg-Sr alloys could benefit the tumor suppression of ZA, and our novel ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys synergistically inhibited GCTB through the induction of GCTB-stromal cells apoptosis, increase of oxidative stress, and inhibition of the stromal cells-mediated pre-osteoclasts migration and osteolysis. At the molecular level, ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys could significantly activate the mitochondrial pathway and inhibit the NF-кB pathway (Fig. 2). Our results, for the first time, lay foundation for developing ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys into a new local adjuvant therapy for GCTB.

5. Materials and methods

5.1. Preparation of ZA-loaded coating on Mg-Sr alloys

Due to the natural affinity between bisphosphonates and CaP substances [48,49], Mg-1.5 wt% Sr alloy implants were used as a substrate to prepare ZA-loaded CaP coating. Towards this end, the Mg-Sr implants were immersed in 0.1 M KF for 24 h, and sub-sequently soaked in the mixed solution of 60 g/L NaNO3, 15 g/L Ca (H2PO4)2 H2O, and 20 mL/L H2O2 for another 24 h [50]. ZA loaded Mg-Sr alloys were then produced by soaking the implants in 5 mL of aqueous ZA solution (Fig. 1), at 37° C for 24 h through the chemical association of ZA with CaP coating. The ZA-loaded CaP coating was termed ZA-2, ZA-3 and ZA-4 for a concentration of ZA at 10‒2 M, 10‒3 M, and 10‒4 M, respectively.

5.2. Structural and morphological characterization

The morphologies and compositional profiles of ZA loaded Mg-Sr alloys were determined by XRD, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy with attenuated total reflectance (FTIR-ATR), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) coupled with EDS.

5.3. Degradation behavior and hemolysis test

The degradation of ZA loaded Mg-Sr alloys was evaluated by placing the implant in the Hanks’ solution following a reported procedure [51]. The rate of the in vitro degradation, termed corrosion rate (CR), was determined by following ASTM G31-72 standard. The hemolysis ratio (HR) was conducted following the procedure outlined in the DINISO 10993-4 standard [52].

5.4. ZA release studies

The release of ZA was measured by HPLC (e2695, Waters). Briefly, a stock solution of ZA (500 µg/mL) was diluted into a working solution with a varying concentration (0.2, 0.5, 2, 5, 20, 50, 200, or 500 µg/mL) by adding deionized water. The ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys were soaked into the cell culture medium at 37° C for 7 days. The ratio between the area of Mg alloys and the volume of the DMEM is 1.25 cm2/mL. The aqueous ZA concentration of standard solutions and Mg alloys extracts were quantified using HPLC. Chromatographic separation was achieved with an Agilent XDB-C18 column and the injection volume was 50 µL. Such procedures were performed once a day over 7 days.

5.5. Cell culture

GCTB tumor samples were surgically removed out of the patients in Guangzhou General Hospital of Guangzhou Military Command with the approved protocol by its ethics committee. The tumor samples were cut into pieces in high glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS, 100 U/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin [45]. The cell suspensions were then sub-cultured in an incubator. After the ninth passage, no monocytes and giant cells were found and then the tumor cells were purified. To evaluate interaction between Mg alloys and the tumor cells, the extracts of different Mg alloys were used to replace the medium during the culturing. The Mg alloy extracts were made by immersion of the Mg alloys in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS at 37 °C for 24 h. The ratio between the area of Mg alloys and the volume of the DMEM is 1.25 cm2/mL. DMEM medium with 10% FBS was used as a blank control in the following experiments.

5.6. Cell growth inhibition assay

After confluency, tumor cells were isolated using trypsin-EDTA and diluted to 2 × 104 in culture medium. After the cells were incubated in 96-well plates for 24 h, the Mg alloy extracts were used to replace the culture medium. Cell proliferation was determined with CCK-8 assays (DOJINDO) after incubation for 1, 3, and 7 days as we described previously [15]. Cytotoxicity was carried out by LDH assay after incubation for 24 h using a cytotoxicity detection kit (Sigma) [53]. DNA contents were measured with the Cyquant cell proliferation assay kit (C7026, Invitrogen) after incubation for 24 h [54]. Cell viability was conducted by Live/Dead Viability g kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) after incubation for 24 h as we described previously [15].

5.7. Cytoskeleton organization observation

A triple staining kit from Millipore was used to fluorescently stain the vinculin, actin, and cell nucleus in order to observe the cytoskele-tal changes. GCTB cells (2 × 104) were first cultured on the Mg alloy samples for 24 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, blocked using 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h. Then they were incubated with vinculin monoclonal antibody (2 µg/mL) at 37 °C for 1 h, and then with Fluoresceinisothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated secondary anti-body (10 µg/mL) and tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated phalloidin (37.5 ng/mL), in order to stain vinculin and actin, respectively. After this, 10 µg/mL 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used to stain cell nuclei.

5.8. ROS generation

Cellular ROS level was quantified by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry. Tumor cells were seeded into the plates, and Mg alloy extracts were used to replace the medium after 24 h. The cells were then stained with 10 µM DCFH-DA for half an hour at 37 °C. This assay is based on the fact that the non-fluorescent DCFH-DA would be converted into the fluorescent DCF [55]. The intracellular ROS level was imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Leica). A parallel set of treated cells were evaluated quantitatively using flow cytometry. Data were assessed by Flow Jo 7.6.1.

5.9. Flow cytometry

The apoptosis of GCTB cells was evaluated by Guava Nexin Reagent (Millipore). Briefly, cultured cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC/7-AAD double labeling solution, and then evaluated by flow cytometry. Subsequently, the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) was analyzed using the fluorochrome JC-1 (ThermoFisher Scientific).

5.10. Wound healing assay

After the GCTB cells (1 × 105) became confluent in the 6-well plates, the medium was exchanged with different Mg alloys extracts. Then, an artificial wound was formed by scratching in the monolayer using pipette tips. The cells that migrated into the scratched area were imaged at 0 and 24 h and the migrated dis-tance was quantified. The migration ratio (%) was calculated as fol-lows: Migration ratio (%) = (original wound width-remaining wound width)/original wound width × 100 [20].

5.11. Transwell migration assays of pre-osteoclasts

Migration of pre-osteoclasts (RAW264.7) to GCTB microenvironment was tested using the transwell system (24-well plates) with 8-mm pore filters (BD Biosciences) by following our previously reported protocols [56,57]. In brief, RAW264.7 cells (5 × 104) were placed in the top chamber of the transwell, and GCTB cells (5 × 104) cultured with Mg alloy extracts were placed in the bottom chamber of the transwell as the chemoattractant. After 1 day, the pre-osteoclasts that migrated to the opposite side of the upper chamber were fixed and labeled with 0.5% crystal violet (Sigma). The staining cells were imaged and lysed to measure the absorbance at 570 nm.

5.12. NF-jB activation and nuclear transportation

A cellular NF-кB translocation assay was conducted to evaluate NF-кB activation. An immunofluorescence assay was used to evaluate the nuclear transportation. Briefly, GCTB cells were exposed to different Mg alloy extracts for 1 day. Then they were fixed and permeabilized for 10 min. After BSA was used to block the nonspecific-binding, a primary antibody against p65 (1:1000, CST) was added to the cells and incubated at 4 °C overnight. Then the cells could incubate with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated Goat Anti-Rabbit secondary antibody for 1 h and DAPI for 5 min. The fluorescence images of p65 protein (green) and cell nuclei (blue) were captured and overlaid. The co-localization area was produced in cyan fluorescence.

5.13. Real-time PCR

Total RNA of GCTB cells treated with different Mg alloy extracts for 24 h was purified using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Briefly, RNA isolated from each sample was reversed transcribed into com-plementary DNA (cDNA) and RT-PCR was performed using the SYBR Green RT-PCR Kit (DBI Bioscience). In each case, the fold changes of targeted genes were quantified by normalizing the Ct values to the β-actin as a housekeeping gene. The primer pairs were listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers sequences used for Real-time PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence (5′−3′) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| CTSK | CCATATGTGGGACAGGAAGAGAGT | TGCATCAATGGCCACAGAGA |

| NFATC1 | AGCAGAGCACGGACAGCTATC | AGGTCCCGGTCAGTTTTCG |

| TRAP | TACCCCGTGTGGTCCATAGC | GTAGCCCACGCCATTCTCAT |

| MMP-9 | CCTGGAGACCTGAGAACCAATC | GTCTCGGGCAGGGACAGTT |

| MMP-13 | TGGCTGCCTTCCTCTTCTTG | GGATTCCCGCGAGATTTGTA |

| E-cadherin | TCATGAGTGTCCCCCGGTAT | CGGAACCGCTTCCTTCATAG |

| PTHrP | ACGGCGACGATTCTTCCTT | AGGTATCTGCCCTCATCATCAGA |

| c-fos | TCCGAAGGGAAAGGAATAAGATG | TTTCCTTCTCCTTCAGCAGGTT |

| RANKL | CAGAAGATGGCACTCACTGCAT | CCTTTTGCACAGCTCCTTGAA |

| β-actin | GGGAAATCGTGCGTGACATT | GGAACCGCTCATTGCCAAT |

5.14. Western blot analysis

The GCTB cells were allowed to interact with different materials for 24 h. Then they were lysed with RIPA extraction buffer. BCA Kit (Pierce) was used to determine the protein concentrations. Then Western blot was carried out to detect different target proteins secreted by the cells including Bax, Bcl-2, p53, caspase 3, Cytochrome c, phospho-NF-кB p65, IкBα, NF-кB p65, and β-actin.

5.15. Statistics

SPSS 13.0 was used to test the significant difference between different groups using one-way analysis of variance. Statistically, the difference was termed significant and highly significant at a p-value of less than 0.05 and 0.01, respectively.

Statement of significance.

In clinics, giant cell tumors of bone (GCTB) are removed by surgery. However, the resultant defects in bone still contain aggressive and metastatic GCTB cells that can recruit osteoclasts to damage bone, leading to new GCTB tumor growth and bone damage after tumor surgery. Hence, it is of high demand in developing a material that can not only fill the bone defects as an implant but also inhibit GCTB in the defect area as a therapeutic agent. More importantly, the molecular and cellular mechanism by which such a material inhibits GCTB growth has never been explored. To solve these two problems, we prepared a new biomaterial, the Mg-Sr alloys that were first coated with calcium phosphate and then loaded with a tumor-inhibiting molecule (Zoledronic acid, ZA). Then, by using a variety of molecular and cellular bio-logical assays, we studied how the ZA-loaded alloys induced the death of GCTB cells (derived from patients) and inhibited their growth at the molecular and cellular level. At the cellular level, our results showed that ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys not only induced apoptosis and oxidative stress of GCTB cells, and suppressed their induced pre-osteoclast recruitment, but also inhibited their migration. At the molecular level, our data showed that ZA released from the ZA-loaded Mg-Sr alloys could significantly activate the mitochondrial pathway and inhibit the NF-кB pathway in the GCTB cells. Both mechanisms collectively induced GCTB cell death and inhibited GCTB cell growth. This work showed how a biomaterial inhibit tumor growth at the molecular and cellular level, increasing our understanding in the fundamental principle of materials-induced cancer therapy. This work will be interesting to readers in the fields of metallic materials, inorganic materials, biomaterials and cancer therapy.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81501859, 31771038, 81601884, and 51673168), The National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFB0702604, 2016YFB0700800, 2016YFA0100900), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Pro-vince, China (2015A030313607 and 2015A030312004). Y. Zhu and C.M. would like to thank the financial support from National Institutes of Health (CA195607).

References

- [1].Cowan RW, Singh G, Giant cell tumor of bone: a basic science perspective, Bone 52 (2013) 238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Niu X, Zhang Q, Hao L, Ding Y, Li Y, Xu H, Liu W, Giant cell tumor of the extremity: retrospective analysis of 621 Chinese patients from one institution, J. Bone Jt. Surg., Am 94 (2012) 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fellenberg J, Sahr H, Kunz P, Zhao Z, Liu L, Tichy D, Herr I, Restoration of miR-127–3p and miR-376a-3p counteracts the neoplastic phenotype of giant cell tumor of bone derived stromal cells by targeting COA1, GLE1 and PDIA6, Cancer Lett 371 (2016) 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lacey DL, Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Kostenuik PJ, Dougall WC, Sullivan JK, San Martin J, Dansey R, et al. , Bench to bedside: elucidation of the OPG-RANK-RANKL pathway and the development of denosumab, Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 11 (2012) 401–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Liu L, Aleksandrowicz E, Fan P, Schonsiegel F, Zhang Y, Sahr H, Gladkich J, Mattern J, Depeweg D, Lehner B, Fellenberg J, Herr I, Enrichment of c-Met+ tumorigenic stromal cells of giant cell tumor of bone and targeting by cabozantinib, Cell Death Dis 5 (2014) e1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].van der Heijden L, Dijkstra PD, van de Sande MA, Kroep JR, Nout RA, van Rijswijk CS, Bovee JV, Hogendoorn PC, Gelderblom H, The clinical approach toward giant cell tumor of bone, Oncologist 19 (2014) 550–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Boissier S, Ferreras M, Peyruchaud O, Magnetto S, Ebetino FH, Colombel M, Delmas P, Delaisse JM, Clezardin P, Bisphosphonates inhibit breast and prostate carcinoma cell invasion, an early event in the formation of bone metastases, Cancer Res 60 (2000) 2949–2954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gouin F, Rochwerger AR, Marco AD, Rosset P, Bonnevialle P, Fiorenza F, Anract P, Adjuvant treatment with zoledronic acid after extensive curettage for giant cell tumours of bone, Eur. J. Cancer 50 (2014) 2425–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zwolak P, Manivel JC, Jasinski P, Kirstein MN, Dudek AZ, Fisher J, Cheng EY Cytotoxic effect of zoledronic acid-loaded bone cement on giant cell tumor, multiple myeloma, and renal cell carcinoma cell lines, J. Bone Jt. Surg., Am 92 (2010) 162–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Van DSJ, Van Lieshout EM, Elmassoudi Y, Van Kralingen GH, Patka P, Bone substitutes in the Netherlands-a systematic literature review, Acta Biomater 7 (2011) 739–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Chai YC, Carlier A, Bolander J, Roberts SJ, Geris L, Schrooten J, Oosterwyck HV, Luyten FP, Current views on calcium phosphate osteogenicity and the translation into effective bone regeneration strategies, Acta Biomater 8 (2012) 3876–3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zhang Y, Xu J, Ye CR, Mei KY, O’Laughlin M, Wise H, Chen D, Tian L, Shi D, Wang J, Chen S, Feng JQ, Chow DH, Xie X, Zheng L, Huang L, Huang S, Leung K, Lu N, Zhao L, Li H, Zhao D, Guo X, Chan K, Witte F, Chan HC, Zheng Y, Qin L, Implant-derived magnesium induces local neuronal production of CGRP to improve bone-fracture healing in rats, Nat. Med 22 (2016) 1160–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Windhagen H, Radtke K, Weizbauer A, Diekmann J, Noll Y, Kreimeyer U, Schavan R, Stukenborg-Colsman C, Waizy H, Biodegradable magnesium-based screw clinically equivalent to titanium screw in hallux valgus surgery: short term results of the first prospective, randomized, controlled clinical pilot study, Biomed. Eng. Online 12 (2013) 62–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee JW, Han HS, Han KJ, Park J, Jeon H, Ok MR, Seok HK, Ahn JP, Lee KE, Lee DH, Yang SJ, Cho SY, Cha PR, Kwon H, Nam TH, Han JH, Rho HJ, Lee KS, Kim YC, Mantovani D, Long-term clinical study and multiscale analysis of in vivo biodegradation mechanism of Mg alloy, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 113 (2016) 716–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Li M, Yang X, Wang W, Zhang Y, Wan P, Yang K, Han Y, Evaluation of the osteo-inductive potential of hollow three-dimensional magnesium-strontium substitutes for the bone grafting application, Mater. Sci. Eng., C 73 (2017) 347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Seo CH, Jeong H, Furukawa KS, Suzuki Y, Ushida T, The switching of focal adhesion maturation sites and actin filament activation for MSCs by topography of well-defined micropatterned surfaces, Biomaterials 34 (2013) 1764–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Li B, Han Y, Qi K, Formation mechanism, degradation behavior, and cytocompatibility of a nanorod-shaped HA and pore-sealed MgO bilayer coating on magnesium, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6 (2014) 18258–18274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Weinberg SE, Chandel NS, Targeting mitochondria metabolism for cancer therapy, Nat. Chem. Biol 11 (2015) 9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Gaston CL, Bhumbra R, Watanuki M, Abudu AT, Carter SR, Jeys LM, Tillman RM, Grimer RJ Does the addition of cement improve the rate of local recurrence after curettage of giant cell tumours in bone?, J Bone Jt. Surg., Br 93 (2011) 1665–1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nayak D, Kumari M, Rajachandar S, Ashe S, Thathapudi NC, Nayak B, Biofilm impeding AgNPs target skin carcinoma by inducing mitochondrial membrane depolarization mediated through ROS production, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8 (2016) 28538–28553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Li G, Zhang L, Wang L, Yuan G, Dai K, Pei J, Yao Y, Dual modulation of bone formation and resorption with zoledronic acid-loaded biodegradable magnesium alloy implants improves osteoporotic fracture healing: an in vitro and in vivo study, Acta Biomater 65 (2018) 486–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Otto S, Pautke C, Opelz C, Westphal I, Drosse I, Schwager J, Bauss F, Ehrenfeld M, Schieker M, Osteonecrosis of the jaw: effect of bisphosphonate type, local concentration, and acidic milieu on the pathomechanism, J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg 68 (2010) 2837–2845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Quail DF, Joyce JA, Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis, Nat. Med 19 (2013) 1423–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kraut JA, Madias NE, Lactic acidosis, N. Engl. J. Med 372 (2015) 1078–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Wang YZ, Wang JJ, Huang Y, Liu F, Zeng WZ, Li Y, Xiong ZG, Zhu MX, Xu TL, Correction: tissue acidosis induces neuronal necroptosis via ASIC1a channel independent of its ionic conduction, Elife 5 (2016) e14128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Casey JR, Grinstein S, Orlowski J, Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 11 (2010) 50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hakimi O, Ventura Y, Goldman J, Vago R, Aghion E. Porous biodegradable EW62 medical implants resist tumor cell growth, Mater. Sci. Eng., C 61 (2016) 516–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Li M, Ren L, Li L, He P, Lan G, Zhang Y, Yang K, Cytotoxic Effect on osteosarcoma MG-63 cells by degradation of magnesium, J. Mater. Sci. Technol 30 (2014) 888–893. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Li M, He P, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Xia H, Zheng Y, Han Y, Stimulatory effects of the degradation products from Mg-Ca-Sr alloy on the osteogenesis through regulating ERK signaling pathway, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 32323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P, Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: a radical therapeutic approach?, Nat Rev Drug Discov 8 (2009) 579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chen W, Zou P, Zhao Z, Chen X, Fan X, Vinothkumar R, Cui R, Wu F, Zhang Q, Liang G, Ji J, Synergistic antitumor activity of rapamycin and EF24 via increasing ROS for the treatment of gastric cancer, Redox Biol 10 (2016) 78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yang L, Yuan Y, Fu C, Xu X, Zhou J, Wang S, Kong L, Li Z, Guo Q, Wei L, LZ-106, a novel analog of enoxacin, inducing apoptosis via activation of ROS-dependent DNA damage response in NSCLCs, Free Radical Biol. Med 95 (2016) 155–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Mroz RM, Schins RP, Li H, Jimenez LA, Drost EM, Holownia A, MacNee W, Donaldson K, Nanoparticle-driven DNA damage mimics irradiation-related carcinogenesis pathways, Eur. Respir. J 31 (2008) 241–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhang W, Hu S, Yin JJ, He W, Lu W, Ma M, Gu N, Zhang Y, Prussian Blue Nanoparticles as multienzyme mimetics and reactive oxygen species scavengers, J. Am. Chem. Soc 138 (2016) 5860–5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Schafer ZT, Grassian AR, Song L, Jiang Z, Gerhart-Hines Z, Irie HY, Gao S, Puigserver P, Brugge JS, Antioxidant and oncogene rescue of metabolic defects caused by loss of matrix attachment, Nature 461 (2009) 109–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tarasenko TN, Pacheco SE, Koenig MK, Gomez-Rodriguez J, Kapnick SM, Diaz F, Zerfas PM, Barca E, Sudderth J, DeBerardinis RJ, Covian R, Balaban R, DiMauro S, McGuire PJ, Cytochrome c oxidase activity is a metabolic checkpoint that regulates cell fate decisions during T cell activation and differentiation, CellMetab 25 (2017) 1254–1268.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Haus U, Ebert R, Meissner-Weigl J, Zeck S, Klein-Hitpass L, Rachner TD, Peggy Benad-Mehner, Athari A, Hofbauer L, Jakob F Effect of zoledronic acid exposure on Ki-67 expression and proliferation in MCF7 cells resistant to apoptosis induction, J. Clin. Oncol 29 (2011) e21129. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Herr I, Sähr H, Zhao Z, Yin L, Omlor G, Lehner B, Fellenberg J, MiR-127 and miR-376a act as tumor suppressors by in vivo targeting of COA1 and PDIA6 in giant cell tumor of bone, Cancer Lett 409 (2017) 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Wu X, Li Z, Yang Z, Zheng C, Jing J, Chen Y, Ye X, Lian X, Qiu W, Yang F, Tang J, Xiao J, Liu M, Luo J, Caffeic acid 3,4-dihydroxy-phenethyl ester suppresses receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand-induced osteoclastogenesis and prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss through inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase/activator protein 1 and Ca2+-nuclear factor of activated T-cells cytoplasmic 1 signaling pathways, J. Bone Miner. Res 27 (2012) 1298–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lieben L, Bone: the concept of RANKL-independent osteoclastogenesis refuted, Nat. Rev.Rheumatol 12 (2016) 263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Song ZB, Ni JS, Wu P, Bao YL, Liu T, Li M, Fan C, Zhang WJ, Sun LG, Huang YX, Li YX, Testes-specific protease 50 promotes cell invasion and metastasis by increasing NF-kappaB-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression, Cell Death Dis 6 (2015) e1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Fu J, Li S, Feng R, Ma H, Sabeh F, Roodman GD, Wang J, Robinson S, Guo XE, Lund T, Normolle D, Mapara MY, Weiss SJ, Lentzsch S, Multiple myeloma-derived MMP-13 mediates osteoclast fusogenesis and osteolytic disease, J. Clin. Invest 126 (2016) 1759–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ho PW, Goradia A, Russell MR, Chalk AM, Milley KM, Baker EK, Danks JA, Slavin JL, Walia M, Crimeen-Irwin B, Dickins RA, Martin TJ, Walkley CR, Knockdown of PTHR1 in osteosarcoma cells decreases invasion and growth and increases tumor differentiation in vivo, Oncogene 34 (2015) 2922–2933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hu Z, Song B, Xu L, Zhong Y, Peng F, Ji X, Zhu F, Yang C, Zhou J, Su Y, Chen S, He Y, He S, Aqueous synthesized quantum dots interfere with the NF-кB pathway and confer anti-tumor, anti-viral and anti-inflammatory effects, Biomaterials 108 (2016) 187–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Xu L, Luo J, Jin R, Yue Z, Sun P, Yang Z, Yang X, Wan W, Zhang J, Li S, Liu M, Xiao J, Bortezomib inhibits giant cell tumor of bone through induction of cell apoptosis and inhibition of osteoclast recruitment, giant cell formation and bone resorption, Mol. Cancer Ther 15 (2016) 854–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR, Li ZW, NF-kappaB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2 (2002) 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Annunziata CM, Stavnes HT, Kleinberg L, Berner A, Hernandez LF, Birrer MJ, Steinberg SM, Davidson B, Kohn EC, Nuclear factor kappaB transcription factors are coexpressed and convey a poor outcome in ovarian cancer, Cancer 116 (2010) 3276–3284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Josse S, Faucheux C, Soueidan A, Grimi G, Massiot D, Alonso B, Janvier P, Laib S, Gauthier O, Daculsi G, Guicheux J, Bujoli B, Bouler JM, Chemically modified calcium phosphates as novel materials for bisphosphonate delivery, Adv. Mater 16 (2004) 1423–1427. [Google Scholar]

- [49].Im GI, Qureshi SA, Kenney J, Rubash HE, Shanbhag AS, Osteoblast proliferation and maturation by bisphosphonates, Biomaterials 25 (2004) 4105–4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Niu J, Yuan G, Liao Y, Mao L, Zhang J, Wang Y, Huang F, Jiang Y, He Y, Ding W Enhanced biocorrosion resistance and biocompatibility of degradable Mg-Nd-Zn-Zr alloy by brushite coating, Mater. Sci. Eng, C 33 (2013) 4833–4841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bian D, Zhou W, Deng J, Liu Y, Li W, Chu X, Xiu P, Cai H, Kou Y, Jiang B, Zheng Y, Development of magnesium-based biodegradable metals with dietary trace element germanium as orthopaedic implant applications, Acta Biomater 64 (2017) 421–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Seyfert UT, Biehl V, Schenk J, In vitro hemocompatibility testing of biomaterials according to the ISO 10993–4, Biomol. Eng 19 (2002) 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Gurunathan S, Park JH, Han JW, Kim JH, Comparative assessment of the apoptotic potential of silver nanoparticles synthesized by Bacillus tequilensis and Calocybe indica in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells: targeting p53 for anticancer therapy, Int. J. Nanomed 10 (2015) 4203–4222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Zhang J, Ma X, Lin D, Shi H, Yuan Y, Tang W, Zhou H, Guo H, Qian J, Liu C, Magnesium modification of a calcium phosphate cement alters bone marrow stromal cell behavior via an integrin-mediated mechanism, Biomaterials 53 (2015) 251–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Li M, Ma Z, Zhu Y, Xia H, Yao M, Chu X, Wang X, Yang K, Yang M, Zhang Y, Mao C, Toward a molecular understanding of the antibacterial mechanism of copper-bearing titanium alloys against staphylococcus aureus, Adv. Health. Mater 5 (2016) 557–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Cao B, Yang M, Zhu Y, Qu X, Mao C, Stem cells loaded with nanoparticles as a drug carrier for in vivo breast cancer therapy, Adv. Mater 26 (2014) 4627–4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Zhang Q, Dong H, Li Y, Zhu Y, Zeng L, Gao H, Yuan B, Chen X, Mao C, Microgrooved polymer substrates promote collective cell migration to accelerate fracture healing in an in vitro model, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7 (2015) 23336–23345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]