Abstract

Background:

Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients are at risk for herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infections. Routine prophylaxis with acyclovir is recommended during periods of immunosuppression. Brincidofovir (BCV, CMX001), a lipid conjugate of cidofovir, is active in vitro activity against HSV/VZV, but has not been formally studied for HSV/VZV prophylaxis. We report our clinical experience of BCV for HSV/VZV prophylaxis in HCT recipients.

Methods:

This was a retrospective review of 30 hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients between 8/2010 and 8/2015 who received BCV doses not to exceed 200mg/week for adults/adolescents and 4mg/kg/week for pediatric (<12 years) patients, for ≥14 days BCV without concomitant acyclovir under clinical trials or single patient use. HSV/VZV cases during BCV treatment were confirmed by viral culture or PCR and clinical symptoms.

Results:

Of 30 patients who met inclusion criteria, 27 (90%) patients were adults and 22 (73%) patients received T-cell depleted HCT. The most common indications for BCV were cytomegalovirus in 12 patients (40%) and adenoviurs in 11 patients (37%). One patient was treated for acyclovir-resistant HSV and one for disseminated VZV. There were 2 breakthrough cases of HSV infection during 2,170 patient days. There were no cases of breakthrough VZV infection.

Conclusions:

The overall rate of breakthrough HSV infection was 1.0 per 1,000 patient-days, without any breakthrough VZV infections. Our study provides the only available -albeit limited- evidence on the potential efficacy of BCV for HSV/VZV prophylaxis in HCT patients. Additional studies are needed to further assess the efficacy and safety of BCV in the setting.

Keywords: Herpes simplex virus (HSV), varicella zoster virus (VZV), brincidofovir, hematopoietic cell transplant

Introduction

Hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT) recipients are at risk for herpes simplex (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV) reactivation. Routine prophylaxis with acyclovir or valacyclovir is recommended during immunosuppression.1 Brincidofovir (BCV, CMX001), a lipid conjugate of cidofovir, has in vitro activity against all double stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses.2 BCV has been evaluated for cytomegalovirus prevention3 and treatment of adenovirus infections.4 In addition, patients have received BCV under expanded access protocols for the treatment of life-threatening infections caused by dsDNA viruses (CMX-350, Clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01143181). Although BCV has been used successfully for the treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV5, clinical data on the efficacy of BCV prophylaxis for HSV/VZV are lacking.

From August 2010 through August 2015, open label BCV monotherapy without concomitant acyclovir for ≥2 weeks was administered in HCT recipients for various indications at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). We report on the efficacy of BCV as HSV/VZV prophylaxis in 30 HCT recipients treated with the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended BCV doses without concomitant acyclovir.

Methods

Study design.

This is a single-center 5-year retrospective observational study of pediatric and adult HCT recipients treated with BCV at MSKCC between 8/27/2010 and 8/31/2015. BCV was administered at ≤200mg/week (100mg twice/week or 200mg/week) in adults and adolescents and at 4mg/kg/week (2mg/kg twice/week or 4mg/kg/week) in pediatric (<12-year-old) patients, for ≥14 consecutive days, without concomitant administration of acyclovir under following protocols: (1) CMX-350, an expanded access study of BCV for serious infections due to dsDNA viruses, (2) CMX-202, a placebo-controlled study of BCV for preemption of adenovirus disease post-HCT (NCT01241344), (3) CMX-304, an open label study of BCV for the treatment of adenovirus viremia or disease (NCT02087306) and (4) single patient use (SPU). Twenty patients treated with BCV doses higher than the currently FDA weekly-recommended BCV doses were excluded from the analyses.

Data collection and definitions.

Data were extracted from medical, pharmacy, and microbiology records. The diagnosis of HSV or VZV infections was based on clinical presentation and qualitative PCR, and/or viral culture performed by the MSKCC clinical microbiology laboratory. BCV treatment duration was calculated as the interval between the first and last dose. BCV patient-days was calculated as the sum of BCV monotherapy days. Steroid doses were calculated during the duration of BCV treatment. Steroid doses were multiplied by their approximate equivalent dose using prednisone dose as a base.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of 30 HCT recipients included in this study. Twenty-seven (90%) patients were adults and 22 (73%) patients received a CD34+-selected (T-cell depleted [TCD]) HCT.6 Five (of 6, 83%) cord blood HCT recipients had acute grade ≥II graft-versus-host disease (GvHD; 4 patients grade II GvHD; 1 patient grade III GvHD) whereas 3 (of 22, 14%) TCD recipients had acute ≥II GvHD (2 patients grade II GvHD; 1 patient grade III GvHD). Eight (of 22, 36%) TCD and 6 (of 6, 100%) cord blood HCT recipients received prednisone while on BCV treatment. The median cumulative prednisone dose per kilogram during BCV treatment was 0.7mg/kg (interquartile range [IQR]: 0 – 15.0). The median cumulative prednisone dose per kilogram in patients on BCV ≥ 100 days was 41.8mg/kg (IQR: 0 – 106.9) and none of them developed breakthrough HSV or VZV.

Table 1:

Baseline patient characteristics

| Patient N=30 (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Adult (≥12 years), median (range) | 27 (90), 53.7 (19.1 – 67.0) |

| Pediatric (<12 years), median (range) | 3 (10), 1.1 (0.6 – 7.6) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 13 (43.3) |

| Male | 17 (56.7) |

| Underlying Disease | |

| Acute Leukemia | 12 (40) |

| Chronic Leukemia | 1 (3.3) |

| Multiple Myeloma | 5 (16.7) |

| Myelodysplastic Syndrome | 3 (10) |

| Lymphoma | 4 (13.3) |

| Retinoblastoma | 1 (3.3) |

| Aplastic anemia | 1 (3.3) |

| Severe combined immune deficiency | 1 (3.3) |

| Transplant Type | |

| Autologous | 1 (3.3) |

| Allogeneic, Unmodified | 1 (3.3) |

| Allogeneic, T-cell depleted1 | 22 (73.3) |

| Allogeneic, Umbilical Cord Blood | 6 (20) |

| Donor Type | |

| Matched Related | 7 (23.3) |

| Matched Unrelated | 7 (23.3) |

| Mismatched Unrelated | 15 (50) |

| Conditioning Regimen | |

| Myeloablative | 22 (73.3) |

| Reduced Intensity | 3 (10) |

| Non-ablative | 3 (10) |

| ALC, median (IQR)2 | 600 cell/mcL (275 – 1,000) |

| CD4+, median (IQR)2 | 38 cell/mcL (10 – 91) |

| Cumulative prednisone dose during BCV treatment/kg, median (IQR)3 | 0.7 mg/kg (0 – 24.6) |

| BCV monotherapy <50 days (N=18) | 0.7 mg/kg (0 – 15.0) |

| BCV monotherapy ≥50 days (N=12) | 5.2 mg/kg (0 – 77.4) |

| BCV monotherapy ≥100 days (N=5) | 41.8mg/kg (0 – 106.9) |

| Concomitant dsDNA virus | |

| ≥3 viruses | 10 (33%) |

| ≥2 viruses | 9 (30%) |

| 1 virus | 11 (37%) |

BCV, brincidofovir; IQR, interquartile range; ALC, absolute lymphocyte count; dsDNA, double stranded DNA

T-cell depletion was performed by the CliniMACS CD34+ reagent system (Miltenyi Biotec, Gladbach, Germany).

At BCV initiation

Steroid doses were multiplied by their approximate equivalent dose using prednisone dose as a base (methylprednisolone × 1.25 = prednisone). Prednisone dose was the sum of prednisone during BCV monotherapy.

Brincidofovir administration data

The majority of patients were enrolled in CMX-350 (N=17), followed by CMX-304 (N=10), CMX-202 (N=1) and SPU (N=4). Two patients enrolled in CMX350 were also subsequently enrolled in CMX-304 (N=1) and treated under SPU (N=1). The indications for BCV were: cytomegalovirus (N=12), adenovirus (N=11), BK-polyoma virus (N=3), cytomegalovirus and adenovirus (N=1), acyclovir-resistant HSV (N=1), disseminated VZV (N=1) and human herpesvirus 6 (N=1) infections. Nineteen patients had infection(s) by ≥2 dsDNA viruses at baseline. During BCV treatment, there was no dsDNA virus breakthrough infection other than 2 HSV infections.

Treatment with BCV began at a median of 88 days (IQR: 55–220) post-HCT. BCV was administered without acyclovir for the entire duration of BCV treatment in 24 (80%) patients; 6 (20%) patients received acyclovir intermittently during BCV treatment. The median duration of BCV monotherapy was 42 days (IQR: 27–80) for a total of 2,170 patient-days. The median absolute lymphocyte count (ALC) and CD4+ count at the time of BCV treatment were 600 cell/mcL (IQR: 275–1000) and 38 cell/mcL (IQR: 10–91), respectively.

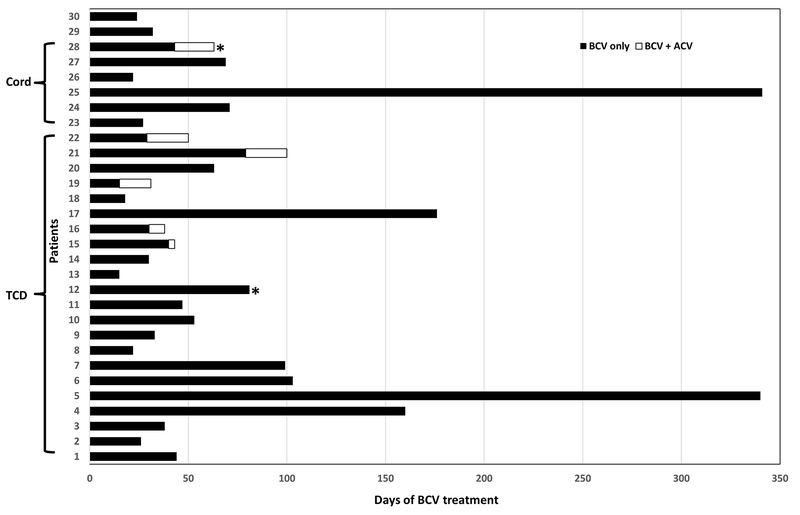

Figure 1 shows the duration of BCV treatment for individual patients: 12 (40%) and 5 (17%) patients received BCV monotherapy for ≥50 and ≥100 days, respectively. Patients #5 and #25 received BCV for 340 and 341 days, respectively. Both patients had severe GvHD for the entire duration of BCV treatment.

Figure 1.

Treatment duration of brincidofovir (BCV). Horizontal bars depict individual patients. Black areas represent days of BCV monotherapy and white areas represent days of BCV with concomitant administration of acyclovir. Total BCV treatment days are calculated as the sum of individual patient-days on BCV monotherapy.

Two (6.7%, #12 and #28) patients developed breakthrough HSV infections. Breakthrough HSV/VZV infection was defined as any HSV/VZV infection that occurred on BCV or ≤7 days of BCV discontinuation.

BCV, brincidofovir; ACV, acyclovir; Cord, cord blood transplant; TCD, T-cell depleted transplant

* Breakthrough HSV infection on BCV.

Breakthrough infections

Two (6.7%) patients (#12 and #28) developed breakthrough HSV infections, for an overall rate of 1.0 HSV infection per 1,000 patient-days. There were no VZV infections observed during the study period.

Patient #12:

This was a 58-year-old male with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) who received a TCD HCT from a mismatched unrelated donor. His course was complicated by grade III skin GvHD and bronchiolitis obliterans requiring high-dose steroids. He developed acyclovir-resistant HSV oral infection on post-transplant day (PTD)+202 and he received foscarnet for 23 days. His immunosuppression regimen included: methylprednisolone 1mg/kg/day, mycophenolate mofetil and sirolimus. Due to several recurrences of oral HSV infection, treatment with BCV with 100mg twice/week was initiated on PTD+376 until PTD+427 with resolution of his HSV infection. His ALC and CD4+ counts were 84 cell/mcL and 29 cell/mcL, respectively, at BCV initiation. His BCV dose was changed to 200mg weekly on PTD+427 until PTD+456. During treatment with BCV, he developed breakthrough oral lesion HSV-positive by PCR on PTD+406. The recurrence was treated successfully with an additional dose of BCV 100mg.

Patient #28:

A 57-year-old female with ALL received double umbilical cord blood transplant. She developed biopsy proven grade II upper gastrointestinal GvHD on PTD+48 and was treated with budesonide in addition to tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. On PTD+54, she developed CMV viremia treated with foscarnet. On PTD+83, she developed breakthrough HSV infection while on foscarnet maintenance dose. Her ALC and CD4+ counts were 300 cell/mcL and 286 cell/mcL, respectively. On PTD+84, she was started on BCV 100mg twice/week for 6 weeks, followed by 200mg once/week for 4 weeks, then 100mg twice/week for one dose. On PTD+118, she was started on low-dose methylprednisolone due to worsening diarrhea, eventually increased to 2mg/kg/day on PTD+147 with the addition of octreotide, and finally etanercept on PTD+153. BCV was intermittently held due to diarrhea. On PTD+155, she developed genital breakthrough HSV infection while on BCV treatment.

Discussion

Clinical data on the efficacy of BCV in HSV/VZV prophylaxis are lacking. In this heterogeneous cohort of 30 highly immunocompromised HCT recipients treated with BCV for multiple dsDNA viruses, there were only two breakthrough cases of HSV infection during 2,170 patient-days at risk, with an overall rate of 1.0 HSV infection per 1,000 patient-days. There were no cases of breakthrough VZV infection. Nineteen patients (63%) had ≥2 concomitant dsDNA viruses for which BCV treatment was administered. The median ALC and CD4+ count at the time of BCV treatment were 600 cell/mcL (IQR: 275–1000) and 38 cell/mcL (IQR: 10–91), respectively. Twenty-two patients (73%) received TCD HCT and 6 patients (20%) received cord blood HCT. Our data suggest that BCV at FDA-recommended treatment doses may be an effective prophylaxis against HSV and VZV reactivation, during administration of BCV for the treatment of dsDNA virus infection in HCT recipients.

There were two breakthrough cases of HSV infection during 2,170 patient-days at risk while on BCV treatment. Although exposure to BCV was limited with only 40% of patients treated for longer than 50 days, 17% of our patients received BCV longer than 3 months without breakthrough infection although they received high doses of prednisone during BCV treatment. The observed HSV infection breakthrough rate of 0.6% (2 of 30 patients) in our cohort is consistent with historical data of breakthrough HSV-infection rates among autologous HCT and allogeneic HCT recipients on acyclovir-based prophylaxis in the range of 0–3.2%.7,8 There were no breakthrough VZV infections while on BCV treatment despite the severe T-cell suppression of patients in this cohort, as suggested by their profound lymphopenia and type of grafts (93% of patients in this cohort received TCD or cord blood HCT). The rate of VZV reactivation post-HCT has ranged between 17% and 63% and recipients of cord blood and TCD HCT are at higher risk for VZV infection.9

Diarrhea, a recognized side effect of BCV, particularly in adults, may preclude prolonged administration of oral BCV or may affect absorption.4 Since BCV interruption is part of management of gastrointestinal toxicity due to BCV, it should be emphasized that alternative HSV prophylaxis should be administered during BCV interruptions. Intravenous (IV) BCV, currently in early development, appears not to have the gastrointestinal toxicities associated with the oral formulation.10 As co-infections with multiple dsDNA viruses occur commonly post-transplant11,12, IV BCV would be an attractive candidate for multi-viral protection.

Acyclovir-resistant HSV infections have been reported in 3–10% of immunocompromised patients.13 A recent European study reported an increase in the incidence of acyclovir-resistant HSV infections from 14% (2002–2006) to 46% (2007–2011) among 843 patients.14 Acyclovir-resistant HSV infections pose significant treatment conundrums in clinical practice and have been associated with poor outcomes in HCT recipients.15 In case #12, BCV was administered for acyclovir-resistant HSV infection and was continued as a secondary prophylaxis, during which the patient developed recurrent HSV when the dose was lowered, but quickly responded to a short treatment course with higher dose BCV. Our findings are consistent with published case reports of successful treatment of acyclovir-resistant HSV with BCV.5,16 These observations are pertinent, as treatment options for acyclovir-resistant HSV are currently limited. Pritelivir, an inhibitor of the HSV helicase-primase complex reduced rates of viral genital shedding and lesions in healthy individuals17 and is currently in clinical trials in HCT recipients with ACV resistant HSV (NCT03073967).

In conclusion, in a highly immunocompromised cohort of HCT recipients, the overall rate of breakthrough HSV infection was 1.0 per 1,000 patient-days, without any breakthrough VZV infections. Despite its significant limitations, including its retrospective approach and limited numbers of patients included, our study provides the only available -albeit limited- evidence on the potential efficacy of BCV for HSV/VZV prophylaxis in HCT patients. Additional studies are needed to further assess the efficacy and safety of BCV as potential single-agent prophylaxis against multiple ds-DNA viruses in high-risk patients.

Acknowledgement:

This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest: GAP has been an investigator for Shire, Merck, Chimerix and Astellas and has received consulting fees from Shire, Merck, Chimerix and Astellas.

References

- 1.Tomblyn M, Chiller T, Einsele H, et al. Guidelines for preventing infectious complications among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients: a global perspective. Preface. Bone Marrow Transplant 2009;44:453–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Florescu DF, Keck MA. Development of CMX001 (Brincidofovir) for the treatment of serious diseases or conditions caused by dsDNA viruses. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2014;12:1171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marty FM, Winston DJ, Rowley SD, et al. CMX001 to prevent cytomegalovirus disease in hematopoietic-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1227–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimley MS, Chemaly RF, Englund JA, et al. Brincidofovir for Asymptomatic Adenovirus Viremia in Pediatric and Adult Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Recipients: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Phase II Trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017;23:512–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voigt S, Hofmann J, Edelmann A, Sauerbrei A, Kuhl JS. Brincidofovir clearance of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus-1 and adenovirus infection after stem cell transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 2016;18:791–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tamari R, Chung SS, Papadopoulos EB, et al. CD34-Selected Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplants Conditioned with Myeloablative Regimens and Antithymocyte Globulin for Advanced Myelodysplastic Syndrome: Limited Graft-versus-Host Disease without Increased Relapse. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2015;21:2106–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dignani MC, Mykietiuk A, Michelet M, et al. Valacyclovir prophylaxis for the prevention of Herpes simplex virus reactivation in recipients of progenitor cells transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 2002;29:263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erard V, Wald A, Corey L, Leisenring WM, Boeckh M. Use of long-term suppressive acyclovir after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation: impact on herpes simplex virus (HSV) disease and drug-resistant HSV disease. J Infect Dis 2007;196:266–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho DY, Arvin AM. Varicella Zoster Virus Infections. Thomas’ Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Stem Cell Transplantation 2015;1:1085–110. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wire MB, Morrison M, Anderson M, Arumugham T, Dunn J, Naderer O. pharmacokinetics (pk) and Safety of Intravenous (iv) Brincidofovir (bcv) in Healthy Adult Subjects. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017: S311. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang YT, Kim SJ, Lee YJ, et al. Co-Infections by Double-Stranded DNA Viruses after Ex Vivo T Cell-Depleted, CD34(+) Selected Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2017;23:1759–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill JA, Mayer BT, Xie H, et al. The cumulative burden of double-stranded DNA virus detection after allogeneic HCT is associated with increased mortality. Blood 2017;129:2316–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stranska R, Schuurman R, Nienhuis E, et al. Survey of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus in the Netherlands: prevalence and characterization. J Clin Virol 2005;32:7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frobert E, Burrel S, Ducastelle-Lepretre S, et al. Resistance of herpes simplex viruses to acyclovir: an update from a ten-year survey in France. Antiviral Res 2014;111:36–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakiuchi S, Tsuji M, Nishimura H, et al. Association of the Emergence of Acyclovir-Resistant Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 With Prognosis in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Patients. J Infect Dis 2017;215:865–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Haddad D, El Chaer F, Vanichanan J, et al. Brincidofovir (CMX-001) for refractory and resistant CMV and HSV infections in immunocompromised cancer patients: A single-center experience. Antiviral Res 2016;134:58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wald A, Timmler B, Magaret A, et al. Effect of Pritelivir Compared With Valacyclovir on Genital HSV-2 Shedding in Patients With Frequent Recurrences: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;316:2495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]