Abstract

Context:

In the intensive care unit (ICU), 14% of patients meet criteria for specialized palliative care, but whether subgroups of patients differ in their palliative care needs is unknown.

Objectives:

To use latent class analysis (LCA) to separate ICU patients into different classes of palliative care needs, and determine if such classes differ in their palliative care resource requirements.

Methods:

Retrospective cohort study of ICU patients who received specialized palliative care, August 2013 – August 2015. Reason(s) for consultation were extracted from the initial note and entered into a LCA model to generate mutually exclusive patient classes. Differences in “high use” of palliative care (defined as having ≥ 5 palliative care visits) between classes was assessed using logistic regression, adjusting for age, race, Charlson comorbidity index and length of stay.

Results:

In a sample of 689 patients, a four-class model provided the most meaningful groupings: 1) Pain and Symptom Management (n=218, 31.6%), 2) Goals of Care and Advance Directives (GCAD) (n=131, 19.0%), 3) All Needs (n=112, 16.3%) and 4) Supportive Care (n=228, 33.1%). In comparison to GCAD patients, all other classes were more likely to require “high use” of palliative care, (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 2.61, [1.41-4.83] for “All Needs”, aOR 2.01 [1.16-3.50] for “Pain and Symptom Management”, aOR 1.94 [1.12-3.34] for “Supportive Care”).

Conclusion:

Based on the initial reason for consultation, we identified four classes of palliative care needs amongst critically ill patients, and GCAD patients were least likely to be high-utilizers. These findings may help inform allocation of palliative care resources for this population.

Keywords: palliative care, critical illness, intensive care units, pain management, advance directives, referral and consultation

In the intensive care unit (ICU), approximately 14% of patients meet criteria for palliative care consultation, or specialized palliative care (1). In this setting, palliative care consults may focus on several different aspects of patient care, ranging from symptom management to goals of care discussions (2). While the importance of incorporating specialized palliative care in the ICU has been acknowledged (3), the critically ill population is heterogeneous with regards to severity of illness, likelihood of survival, and the impact of the acute episode of illness in a patient’s overall trajectory of care (4-6). Given this heterogeneity, patients may also differ in their palliative care needs. While there is evidence that survivors of critical illness may go on to have different subtypes of symptom burden (7), and that patients in outpatient palliative care settings may be classified into different subtypes of illness burden (8), data on whether and how patients differ in their palliative care needs during an acute episode of critical illness, and whether particular palliative care needs require more or less involvement of specialists is lacking. Such information may help to clarify the burden of palliative care needs in critically ill patients and inform allocation of specialized palliative care resources given the existing shortage of palliative-care trained physicians in the United States (9). Thus, the primary aim of this study was to use latent class analysis (LCA) to evaluate whether patients from a variety of ICU settings can be separated into different classes of palliative care need, and to determine whether such classes are associated with differences in resource requirements and outcomes.

Methods

Data collection

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all adult (age ≥ 18) ICU patients in a single academic medical center (including medical, cardiac, surgical, cardiothoracic and neurological ICUs) that received specialized palliative care from August 2013 – August 2015. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) (IRB-AAAP2112 New York, NY). Written informed consent was waived. Data for this retrospective study came from the Clinical Data Warehouse, a repository of electronic medical records, at CUMC in New York, NY. We obtained demographic and clinical variables from the medical record, and we obtained information about palliative care consultation directly from palliative care notes written in the medical record. Within the initial consultation note, the “reason for consultation” is a non-mutually exclusive check box field. The reason for consultation is documented in every initial consultation note, multiple reasons may be enumerated and the field must be completed in order to finalize the note. The palliative care provider fills out this information based on the reason for consult, as specified by the primary team. We determined patients’ palliative care needs on initial consultation based on which reasons were specified in this field. The 9 reasons for initial palliative care consultation included symptom management (e.g. delirium, anxiety, dyspnea), pain management, goals of care, prognostication, withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy, discharge planning (for dispositions other than hospice), advance directives, hospice referral and supportive care. More than one reason, and up to nine reasons could be chosen for each consultation.

Statistical Analysis

LCA is a statistical method that may be used to define subgroups of patients (latent classes) using observed variables (10); this technique has been used previously to identify clinical phenotypes of palliative care in patients with cancer (11, 12). In this study, the observed variables were the initial reason(s) for palliative care consultation. For these variables, no data were missing, resulting in inclusion of all eligible patients into the model. These nine reasons were entered into a series of LCA models specifying increasing numbers of latent classes (2 to 7 classes) to generate mutually exclusive classes of patients. Models were then compared for relative fit using three information criteria: Akaike (AIC), Bayesian (BIC), and sample-size adjusted BIC (SABIC) (13). A variety of fit indices can be used as criteria for model selection with most studies evaluating multiple indices; however, SABIC has been found to be the most accurate and consistent of the information criterion tests (14, 15). Selection of the number of latent classes in the final model relied on minimizing the value of the information criteria, as well as interpretability of the model.

After the selection of the final model, each patient was assigned to the specific class for which they had the highest probability of belonging (the posterior probability). After this assignment, the frequency of each palliative care need at the time of initial consultation was assessed for patients in each class. Based on the prevalence of particular needs in each class (in relation to their prevalence in the overall study population), classes were given a descriptive name (e.g. “All Needs”). We then examined differences in demographic (age, gender, race) clinical characteristics (Charlson comorbidity index, time to palliative care consultation, primary diagnosis, code status at time of initial consultation) and outcomes (hospital length of stay, death in hospital and hospital discharge location) of patients in each latent class using appropriate bivariate testing. We also examined whether patients in specific latent classes required “high use” of palliative care (defined as having ≥ 5 visits by the palliative care team, which represented the highest quartile of palliative care use) using logistic regression, before and after adjustment for a priori selected confounders (age, race, Charlson comorbidity index and hospital length of stay). To further characterize palliative care involvement, we determined the number of visits by different members of the palliative care team (MDs and nurse practitioners (NPs), social workers and chaplains), and analyzed differences in the number of visits by clinician type using negative binomial and zero-inflated negative binomial regression, adjusting for overall number of visits and hospital length of stay. Database management and analysis were conducted using Stata 13.1 and MPlus 7.1.

Results

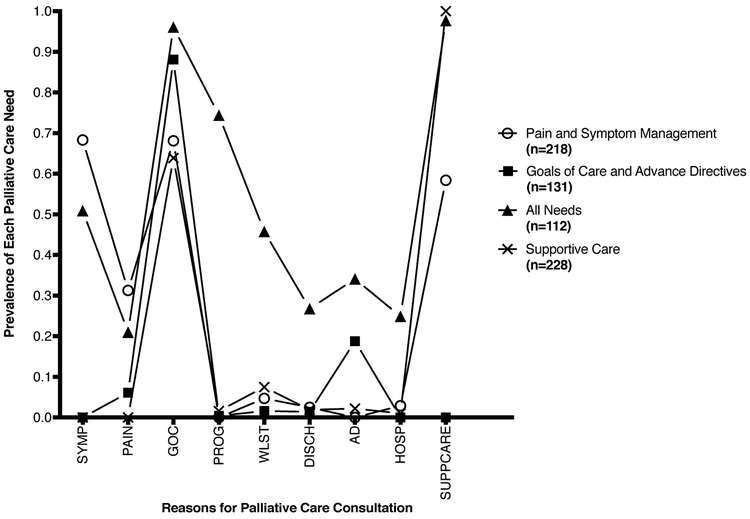

Our study consisted of 689 ICU patients who had a palliative care consultation. Model fit statistics suggested that a five-class model had optimal fit with the lowest SABIC (2-class 4994, 3-class 4970, 4-class 4951, 5-class 4936, 6-class 4936, 7-class 4970); however, the four-class model yielded the most clinically meaningful subgroups. Balancing model fit and interpretability, we ultimately chose the four-class model with the following groups: 1) Pain and Symptom Management (n=218, 31.6% of the study cohort), 2) Goals of Care and Advance Directives (GCAD) (n=131, 19.0%), 3) All Needs (n=112, 16.3%) and 4) Supportive Care (n=228, 33.1%). The patients in “All Needs” and “Pain and Symptom Management” classes had a higher probability of requiring pain and symptom management which was not seen in the other classes. While goals of care was commonly a reason for consultation in all classes, it was required in nearly all consults in patients in the GCAD and “All Needs” classes. In addition, these two classes also had a need for advance directives discussions not seen in the other classes. All patients in the “Supportive Care” class required supportive care; all other needs were uncommon, with the exception of goals of care, which still occurred with less frequency than in other classes. Other less common needs (prognostication, withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy, discharge planning, and hospice referral) were only found in the “All Needs” class of patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients within each latent class with individual palliative care needs.

PAIN, pain management; SYMP, symptom management; GOC, goals of care; PROG, prognosis; WLST, withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy; DISCH, discharge planning; AD, advance directives; HOSP, hospice referral; SUPPCARE, supportive care. Each mark denotes the proportion of patients with a specific palliative care need. Circles denote proportions for patients in the “Pain and Symptom Management” class, squares denote proportions for patients in the “Goals of Care and Advance Directives” class, triangles denote proportions for patients in the “All Needs” class and X’s denote proportions for patients in the “Supportive Care” class. Patients assigned to a given class have a higher prevalence of specific needs in comparison to the prevalence in the overall sample. For example, patients in the “Pain and Symptom Management” class had a higher prevalence of pain and symptom management in comparison patients in other classes.

There were no significant differences in age, sex, race or hospital length of stay between classes. However, there were differences in common primary diagnoses between classes, with patients in the “Pain and Symptom Management” class having the highest rate of respiratory failure (p=0.04), patients in the “Supportive Care” class having the highest rate of cardiac arrest (p=0.001) and cancer (p=0.005), and patients in the GCAD class having the highest rate of congestive heart failure (p<0.001). Patients in the GCAD class were less likely have a do-not-resuscitate status at the time of initial consultation (p<0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Intensive Care Unit Admissions who received a Palliative Care Consultation, Stratified by Latent class Membership

| All (n=689) |

Class 1 Pain and Symptom Management (n=218) |

Class 2 Goals of Care and Advance Directives (n=131) |

Class 3 All Needs (n=112) |

Class 4 Supportive Care (n=228) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD)a | 66.0 (15.9) | 67.1 (16.1) | 65.4 (13.8) | 67.3 (15.4) | 64.6 (16.8) | 0.38 |

| Male, %b | 63.3 | 64.7 | 64.9 | 52.7 | 66.2 | 0.09 |

| Race, %b,c | 0.21 | |||||

| Caucasian | 39.5 | 41.3 | 40.5 | 37.5 | 38.2 | |

| African-American | 11.2 | 10.6 | 17.6 | 7.1 | 10.1 | |

| Asian/Other | 18.7 | 19.3 | 13.7 | 17.9 | 21.5 | |

| Unknown | 30.6 | 28.9 | 28.2 | 37.5 | 30.3 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, %b | 0.03 | |||||

| 0 | 27.0 | 24.3 | 19.9 | 35.7 | 29.4 | |

| 1-2 | 47.3 | 46.8 | 50.4 | 38.4 | 50.4 | |

| ≥3 | 25.7 | 28.9 | 30.0 | 25.9 | 20.2 | |

| Primary Diagnosis, %b | ||||||

| Congestive Heart Failure or Cardiogenic Shock |

18.4 | 14.2 | 35.1 | 12.5 | 15.8 | <0.001 |

| Respiratory Failure | 8.1 | 11.9 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 8.3 | 0.04 |

| Cardiac Arrest | 3.2 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 3.6 | 6.6 | 0.001 |

| Cancer | 13.8 | 9.6 | 13.7 | 8.9 | 20.2 | 0.005 |

| DNR at Time of Initial Consultation, %b |

34.4 | 39.0 | 19.1 | 48.2 | 32.0 | <0.001 |

| Median Time from ICU Admission to Consultation, days (IQR)d |

4 (2-9) | 4 (2-9) | 5 (2-9) | 5 (1-10.5) | 4.5 (1.5-10) | 0.63 |

| Median Time from Hospital Admission to Consultation, days (IQR)d |

9 (4-17) | 9 (4-17) | 8 (4-17) | 10 (4-17) | 8 (4-17) | 0.66 |

| Hospital Length of Stay, days (IQR)d |

20 (11-36) | 18 (10-34) | 23 (12-40) | 20 (10-33) | 20.5 (11.5-38) | 0.18 |

| Discharge Destination, %b,c | 0.005 | |||||

| Died in Hospital | 53.1 | 51.9 | 45.3 | 56.3 | 57.1 | |

| Home | 24.1 | 24.3 | 37.5 | 17.9 | 19.5 | |

| SNF | 11.9 | 10.8 | 6.3 | 17.0 | 13.7 | |

| Rehabilitation Facility |

1.3 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.3 | |

| Other Care Facility | 6.5 | 6.1 | 7.8 | 6.3 | 6.2 | |

| Hospice | 3.1 | 6.1 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 2.2 | |

SD, standard deviation; DNR, do not resuscitate; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; SNF, skilled nursing facility.

Results of simple linear regression.

Results of Pearson’s chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test.

For race, data were missing or unknown for 30.6% of patients. For discharge destination, data were missing for 1.3% of patients. Data was not missing for any other listed variables.

Results of Kruskal-Wallis test.

Compared to the GCAD class of patients, patients in the “All Needs” class were less likely to be discharged home (p=0.005) (Table 1), and more likely to require “high use” of palliative care (19.1% vs. 35.7%, odds ratio (OR) 2.36, 95% confidence interval [1.32-4.22], p=0.03). This difference persisted after adjustment for selected confounders; compared to GCAD patients, all other classes were more likely to require “high use” of palliative care, (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 2.61, [1.41-4.83], p=0.002 for “All Needs”, aOR 2.02 [1.16-3.50], p=0.01 for “Pain and Symptom Management”, aOR 1.94 [1.12-3.34], p=0.02 for “Supportive Care”) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Association between Latent Class Membership and High Use of Specialized Palliative Care

| Crude (OR [95% CI]) |

P-value | Adjusted a aOR [95% CI]) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals of Care and Advance Directives |

ref | - | Ref | - |

| Pain and Symptom Management | 1.76 [1.04-2.98] | 0.03 | 2.02 [1.16-3.50] | 0.01 |

| All Needs | 2.36 [1.32-4.22] | 0.004 | 2.61 [1.41-4.83] | 0.002 |

| Supportive Care | 1.88 [1.12-3.16] | 0.02 | 1.94 [1.12-3.34 | 0.02 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; ref, reference.

Adjusted for age, race, Charlson comorbidity index and hospital length of stay. For the race variable, “missing” was a separate category, resulting in inclusion of all patients in the analysis.

We also observed differences in the number of visits by different types of palliative care clinicians between classes. In comparison to patients in the GCAD class, patients in the “Supportive Care” class were significantly more likely to have visits from the palliative care social workers (aOR 1.40 [1.10-1.79], p=0.007) and less likely to have visits from MDs/NPs (aOR 0.79 [0.66-0.95], p=0.01). Patients in this class were also more likely to have visits from the palliative care chaplain, although this finding did not reach statistical significance (aOR 2.29 [0.99-5.28], p=0.052). Patients in the “All Needs” class had a significantly higher number of MD/NP visits in comparison to patients in the GCAD class (aOR 1.31 [1.08-1.60], p=0.007), while patients in the “Pain and Symptom Management” class did not significantly differ from patients in the GCAD class for any type of clinician visit (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association between Latent Class Membership and Number of Visits by Type of Palliative Care Clinician

| MD/NPa aOR [95% CI]) |

P-value | Social Workerb aOR [95% CI]) |

P-value | Chaplainb aOR [95% CI]) |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goals of Care and Advance Directives | ref | - | ref | - | ref | - |

| Pain and Symptom Management | 1.10 [0.92-1.31] | 0.31 | 1.00 [0.77-1.30] | 1.00 | 1.69 [0.72-4.00] | 0.23 |

| All Needs | 1.31 [1.08-1.60] | 0.007 | 1.06 [0.79-1.42] | 0.71 | 0.91 [0.34-2.42] | 0.85 |

| Supportive Care | 0.79 [0.66-0.95] | 0.01 | 1.40 [1.10-1.79] | 0.007 | 2.29 [0.99-5.28] | 0.052 |

MD, medical doctor; NP, nurse practitioner; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ref, reference.

Results of negative binomial regression, adjusted for overall number of visits and hospital length of stay.

Results of zero-inflated negative binomial regression, adjusted for overall number of visits and hospital length of stay.

Given that the SABIC model fit indices suggested that a five-class model would have been optimal, we also examined the association of this model with high-use of palliative care. The five-class model yielded similar groupings to the four-class model, but separated “Goals of Care” and “Advance Directives” into two classes, with the “Advance Directives” class representing only 3.5% of the overall cohort (n=24). When we examined differences in high use of palliative care using the five-class model, patients in the “Advance Directives” class were not significantly different than the “Goals of Care” class with regard to high use of palliative care, and results for other groups were qualitatively unchanged with all other groups being more likely to require high use of palliative care.

Discussion

Based on the initial reason for consultation, we identified four different latent classes of palliative care needs amongst critically ill patients. The GCAD class of patients were least likely to be high-utilizers of specialized palliative care and most likely to be discharged home. Not surprisingly, the “All Needs” class of patients were most likely to be high-utilizers of specialized palliative care and least likely to be discharged home. We also observed differences in the number of visits by different members of the palliative care team between classes. These data demonstrate that palliative care needs amongst critically ill patients are heterogeneous, and suggest that the intensity of specialized palliative care involvement may differ amongst patients based on their initial palliative care needs.

While specialized palliative care referral may be requested for multiple reasons (2), thus far, there has been no differentiation of palliative care phenotypes, and of how such phenotypes may relate to resource utilization. Currently, referrals from the ICU account for approximately a quarter of U.S. adult palliative care teams’ consult volume (16). Identifying which patients are likely to be high versus low utilizers of specialized palliative care may aid hospitals and palliative care teams in understanding staffing requirements to meet patient needs in the ICU. Furthermore, despite the shortage of palliative-care trained physicians (9) and urgent calls for generalists to deliver basic palliative care in order to offload specialist teams (17), there has been scant data to help differentiate which critically ill patients may benefit most from involvement of specialized palliative care. Such differentiation becomes even more pressing given increasing evidence of the benefit of specialized palliative care for other patient populations (18, 19) and of generalist palliative care interventions in the ICU (20, 21).

Limitations of our study include the fact that palliative care needs were defined based only on the initial consultation note, as in a previous study, patients were found to develop additional needs on follow-up consultation (2). Also, we only included patients who received a palliative care consultation in this study; other critically ill patients may have had specialist-level palliative care needs that were not referred. We also did not examine differences in non-ICU patients requiring palliative care consultation, and our results may not translate to this population. In examining differences in palliative care use between classes, the possibility of residual confounding still exists despite our adjusted analyses. Lastly, the data come from a single center (likely with particular referral patterns) which may limit generalizability.

Using latent class analysis, we were able to identify clinically meaningful classes of palliative care needs amongst critically ill patients that were associated with differences in utilization of specialized palliative care. Future work should be directed towards understanding which critically ill patients benefit most from involvement of specialized palliative care, so that we may appropriately target this scarce and valuable resource.

Disclosures and Acknowledgements:

Dr. Hua is supported by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award (Award Number K08AG051184) from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health and the American Federation for Aging Research. Dr. Ing is supported by a Career Development Award from the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research (Award Number K08HS022941) and a Herbert Irving Scholars Award. The funding sources were not involved in the design and conduct of the study, interpretation of data, preparation of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Dr. Wang and Dr. Blinderman have no support. Dr. Ing is supported by a Herbert Irving Scholars Award as well as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) under award number K08HS022941. Dr. Hua is supported by a Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award (Award Number K08AG051184) from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health and the American Federation for Aging Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

David wang reported no conflicts of interest. Caleb Ing reported no conflict of interest. Craig Blinderman reported no conflict of interest. May Hua reported no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

David Wang, Department of Anesthesiology, University of California, San Francisco.

Caleb Ing, Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health.

Craig Blinderman, Department of Medicine, Columbia University, New York, NY.

May Hua, Department of Anesthesiology, Columbia University College of Physcians and Surgeons; Department of Epidemiology, Mailman School of Public Health.

References

- 1.Hua MS, Li G, Blinderman CD, Wunsch H. Estimates of the need for palliative care consultation across united states intensive care units using a trigger-based model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:428–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stix B, Wunsch H, Clancy C, Blinderman C, Hua M. Variability in frequency of consultation and needs assessed by palliative care services across multiple specialty ICUs. Intensive Care Med 2016;42:2104–2105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards JD, Voigt LP, Nelson JE. Ten key points about ICU palliative care. Intensive Care Medicine 2017;43:83–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Zimmerman JE, Draper EA. Variations in mortality and length of stay in intensive care units. Ann Intern Med 1993;118:753–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iwashyna TJ. Trajectories of recovery and dysfunction after acute illness, with implications for clinical trial design. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:302–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ranzani OT, Zampieri FG, Park M, Salluh JI. Long-term mortality after critical care: what is the starting point? Crit Care 2013;17:191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown SM, Wilson EL, Presson AP, et al. Understanding patient outcomes after acute respiratory distress syndrome: identifying subtypes of physical, cognitive and mental health outcomes. Thorax 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhingra L, Dieckmann NF, Knotkova H, et al. A High-Touch Model of Community-Based Specialist Palliative Care: Latent Class Analysis Identifies Distinct Patient Subgroups. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52:178–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lupu D, American Academy of H, Palliative Medicine Workforce Task F. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ing C, Wall MM, DiMaggio CJ, et al. Latent Class Analysis of Neurodevelopmental Deficit After Exposure to Anesthesia in Early Childhood. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2017;29:264–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miaskowski C, Dunn L, Ritchie C, et al. Latent Class Analysis Reveals Distinct Subgroups of Patients Based on Symptom Occurrence and Demographic and Clinical Characteristics. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:28–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papachristou N, Barnaghi P, Cooper BA, et al. Congruence Between Latent Class and K-Modes Analyses in the Identification of Oncology Patients With Distinct Symptom Experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:318–333 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tein JY, Coxe S, Cham H. Statistical Power to Detect the Correct Number of Classes in Latent Profile Analysis. Struct Equ Modeling 2013;20:640–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tofighi D, Enders CK. Identifying the correct number of classes in growth mixture models. Advances in Latent Variable Mixture Models 2008:317–+. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang C-C. Evaluating latent class analysis models in qualitative phenotype identification, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Palliative Care Registry. 2017 Graphs of Hospital Findings: Palliative Care Program Features. 2017. Available from: https://registry.capc.org/metrics-resources/summary-data/. Accessed July 23, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kavalieratos D, Gelfman LP, Tycon LE, et al. Palliative Care in Heart Failure: Rationale, Evidence, and Future Priorities. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;70:1919–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White DB, Angus DC, Shields AM, et al. A Randomized Trial of a Family-Support Intervention in Intensive Care Units. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2365–2375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Randomized Trial of Communication Facilitators to Reduce Family Distress and Intensity of End-of-Life Care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;193:154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]