Abstract

Background:

Sexual dysfunction is common in women with vulvodynia.

Objective:

1. To evaluate whether extended-release gabapentin is more effective than placebo in improving sexual function in women with provoked vulvodynia, and if there is a relationship between treatment outcome and pelvic pain muscle severity evaluated by palpation with standardized applied pressure. 2. To evaluate whether sexual function in women with PVD would approach that of controls who report no vulvar pain either before or after treatment.

Study Design:

As a secondary outcome in a multicenter double-blind, randomized crossover trial, sexual function, measured by the Female Sexual Function Index, was evaluated with gabapentin (1200 – 3000 mg/day) compared to placebo. Pain free controls, matched by age and race, also completed FSFI for comparison.

Results:

From August 2012 to January 2016, 230 women were screened at three academic institutions and 89 women were randomized to treatment. Gabapentin was more effective than placebo in improving overall sexual function (adjusted mean difference 1.3, 95% confidence interval, CI: 0.4, 2.2; P=.008), including desire (mean difference 0.2, 95% CI 0.0–3.3; P=.04), arousal (mean difference 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1–0.5; P=.004) and satisfaction (mean difference 0.3, 95% CI 0.04–0.5; P=.02), but sexual function remained significantly lower than in 56 matched vulvodynia pain-free controls. There was a moderate treatment effect among participants with baseline pelvic muscle pain severity scores above the median on the full Female Sexual Function Index scale (mean difference: 1.6, 95% CI: 0.3-2.8, P=0.02), and arousal (mean difference: 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1 −0.6; P=.01) and pain domains (mean difference: 0.4, 95% CI: 0.02-0.9, P=0.04).

Conclusions:

Gabapentin improved sexual function in this group of women with provoked vulvodynia, although overall sexual function remained lower than women without the disorder. The most statistically significant increase was in the arousal domain of the Female Sexual Function Index suggesting a central mechanism of response. Women with median algometer pain scores greater than 5 improved sexual function overall, but the improvement was more frequent the pain domain., we hypothesize that gabapentin may be effective as a pharmacologic treatment for those women with provoked vulvodynia and increased pelvic muscle pain on exam.

Keywords: Gabapentin Vulvodynia Sexual Function Pelvic Floor

INTRODUCTION

Vulvodynia, characterized by symptoms which may include stinging, burning, irritation or itching of the vulva, is a chronic pain syndrome with a 7-16% lifetime prevalence (1). Women with vulvodynia experience difficulties across all domains of sexual function (sexual arousal, orgasm, satisfaction, pain) as measured by the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) (2), a widely recognized outcome measure for sexual dysfunction. Provoked vulvodynia (PVD), the most common and best characterized subset of vulvodynia is localized to the vestibule (entry to the vagina immediately anterior to the hymenal ring) and occurs only with contact, such as from tampon insertion or intercourse. By consensus, PVD pathogenesis is multidimensional and includes dysfunction of mucosal mechanoreceptors, enhanced deeper soft tissue/muscular nociception, central sensitization, and various co-morbidities. PVD—Fibromyalgia comorbidity may be a classic example of a PVD subset based upon a significant degree on soft tissue/muscular pain augmenting vulvodynia. We have previously reported that women with vulvodynia-fibromyalgia comorbidity have increased algometer pain scores and propose that the vaginal algometer may be considered a Tender Point Tenderness (TPT) examination of the vagina (3).

Data from the Arnold, et al. study (4) suggested that Gabapentin reduces the pain of fibromyalgia. If one of several treatable vulvodynia pain triggers is pelvic floor (levator) pain/dysfunction then treatment which reduces pelvic floor muscle pain to palpation may reduce vulvodynia pain overall. We performed a secondary analysis on women enrolled in a study of gabapentin and PVD arm for sexual function overall and also analyzed changes in sexual function based on levator muscles pain severity

We hypothesized that by reducing muscle pain, gabapentin treatment would result in improved sexual functioning. Our second hypothesis is that our affected cohort, even if they experience an increase in FSFI score, will not have scores approaching unaffected women.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This was an 18-week, multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blinded RCT with a two-treatment, two-period crossover design that studied the efficacy of extended release gabapentin (Gralise™) (1200–3000 mg/day) for localized provoked vulvodynia (previously known as vulvar vestibulitis).

The study was conducted between August 8, 2012 and January 19, 2016 and received IRB approval at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (#10-00985-FB), Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School (#0220110309), and the University of Rochester (#31720). All participants provided written informed consent. The Gabapentin (GABA) RCT was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT1301001).

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria included women between the ages of 18-50 years (later extended to women aged 50 years and above since the reported upper age for vulvodynia is well above 50 years of age) (5), reporting greater than 3 continuous months of insertional dyspareunia, pain to vulvar touch or vulvar pain with tampon insertion or both and during pelvic examination. Participants were allowed to use oral contraceptives, hormone therapy or selective serotonergic reuptake inhibitors if they were prescribed prior to randomization and were on a stable dose.

Candidates fulfilled Friedrich’s criteria (6), by their reporting tenderness of the vulvar vestibule with intercourse or touch, as with tampon insertion, using modified diagnostic criteria of Bergeron et al (7).A mean score equal to or greater than 4 out of 10 on a numeric rating scale of pain severity was required, however the highest score was needed to be in the vulvar vestibule and not on the peripheral vulva area or inside the vagina.

A baseline level of pain (mean 4 out of 10 or greater on the 11-point Tampon Test [0 = no pain at all; 10 = worse pain ever]) was required to proceed to randomization. The Tampon Test has been shown to have reliability, construct validity, and responsiveness (8) and was used as the outcome measure in the primary efficacy trial (9).

Methods and Procedures

This randomized trial of two treatments – gabapentin and placebo – had a two-period crossover design with 6 weeks per treatment period (4-week dose titration and 2-week maintenance dose with a 4-day washout period). Patients were randomized (double-blind) in a 1:1 ratio and allocated to one of two possible treatment sequences. A trial pharmacist prepared a concealed allocation schedule by computer randomization of these two sequences, in blocks of three, to a consecutive number series. Patients were assigned in turn to the next consecutive number, and the corresponding series of study drugs was dispensed. Investigators, research staff and participants were blinded after assignment to interventions. Participants were asked to take the oral medication in divided doses and to incrementally increase dose regardless of point of response (pain relief). In the event of non-serious side effects, such as sleepiness, participants were asked to decrease tablet dose each day by one to the lowest tolerable dose, and to remain at that dose for the remainder of the clinical trial. Acetaminophen, aspirin, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were permitted as “rescue medication” for pain, and were documented, if used. The use of opioid analgesics and topical medications were protocol violations. When deemed medically necessary, an unblinding protocol was followed (which occurred in 3 women, all on placebo).

Participants completed the FSFI at baseline and after six weeks of treatment with gabapentin and placebo (4-weeks of titration + 2 weeks of maintenance dose). Fifty-six vulvar pain-free controls also completed the FSFI.

During each of the study visits, participants were evaluated by pelvic examination, cotton swab test, pelvic muscle pain severity to palpation to standardized applied pressure, and assessment of vaginal milieu; the cotton swab test was performed at the last study visit. Cotton swab test was performed on pre-defined points of the labia majora, minora, and lower vagina, as described (7). Vaginal milieu assessment included microscopic wet mount vaginal smears, Rakoff stain (10) for vaginal maturation index, Affirm™ (VPIII Microbial Identification System, Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) test to assess for vaginitis, a phenazine test tape for vaginal pH, and urine pregnancy test. Those with vulvovaginal atrophy assessed by maturation index, were treated with topical vaginal estrogen therapy for at least 6 weeks and re-screened for atrophy prior to randomization. Those with vaginitis were treated and re-screened for eligibility. Vaginitis was treated, when necessary, throughout the trial.

Outcomes

Female Sexual Function Index.

The FSFI is a 19-item, multidimensional, self-report measure comprised of a full scale and six domains (desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, satisfaction, and pain) (2). The measure was designed for clinical trials, and has demonstrated reliability, construct validity and responsiveness. The total FSFI score (sum of the six domains) ranges from 2–36 points. Higher scores represent better sexual functioning, and scores below the cut-off 26.55 represent a risk of having sexual dysfunction (11). We followed the guidelines of the authors and derived the full-scale score only in participants who had sexual activity during the measurement period. This method prevents reducing the score toward a more dysfunctional level when participants who abstain from intercourse are included. Individual domains were analyzed in all randomized participants. The FSFI was administered at randomization and following 6 weeks of treatment with gabapentin and with placebo.

Pelvic muscle pain to standardized digital force.

An algometer was used to assess pelvic muscle pain. This devise consists of a pressor sensor that is inserted into the vagina, allowing the application of controlled force. Pelvic muscle pain severity to palpation to standardized applied pressure was performed using a random staircase method and an 11-point numeric rating scale (NRS) (0, no pain −10, worse possible pain) direct scaling of pain response to a load cell-mediated, digitally applied force stimulus. Forces of 0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 kg/cm2 were applied digitally in random assignment to the right and left Iliococcygeus muscle regions. A composite algometer pain severity score was the mean NRS (0 = no pain to 10 = worse possible pain) for the three applied forces (0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 kg/cm) at the two Iliococcygeus muscle regions.

Data collection

Data collection utilized a proprietary database platform Slim-Prim, (Scientific Laboratory & Patient-care Research Information management system, University of Tennessee) (12) a web-accessible, modular data-based system mounted on an Oracle server acted as the Central Data Repository. Data was entered electronically by participants remotely, and by research staff at study visits. The patient responses were reviewed by the research nurse at weekly telephone calls, and the accuracy of the database was validated by the data manager staff member and the principal investigator at the core site.

Sample size calculation

The number of participants randomized was based on a power analysis of the primary outcome of the clinical trial, the tampon test (9). To achieve a power of 90% and a significance level of 5% to detect a one-point difference between the two phases on a scale of 0 to 10 of the Tampon Test, a sample size of 53 was needed. Assuming a dropout rate of 40%, 89 participants were randomized to complete 53.

Data analysis

Demographic characteristics of trial participants were presented. Participant’s baseline scores on the FSFI were compared with matched vulvodynia pain-free controls, matched by gender, race, age (+/−5 years), and center using a paired t-test.

Descriptive unadjusted means of the full FSFI and its six subscales were calculated for participants during the gabapentin and placebo treatment phases. The main analysis of treatment effect on FSFI scores was done using the Mixed Procedure in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) according to the crossover design and based on intent-to-treat principle. The mixed model, with participant as the random effect, combined both within individual differences and between individual differences. The model included period, treatment and the center effect. Degrees of freedom were further adjusted using Kenward-Roger method to take account of small sample size. A sub-analysis was performed to determine the effect of pelvic muscle tenderness on treatment outcome by stratifying baseline algometer scores above median (high muscle pain severity) and below median (low muscle pain severity) scores.

Model adjusted means, 95% confidence interval (CI), and mean differences were reported based on the mixed models. Statistical significance was defined as a P value less than 0.05 using two-tailed tests. A completer analysis, including everyone who completed FSFI in both gabapentin and placebo for 6 weeks, was performed on all treatment outcomes as a secondary analysis.

RESULTS

Attrition

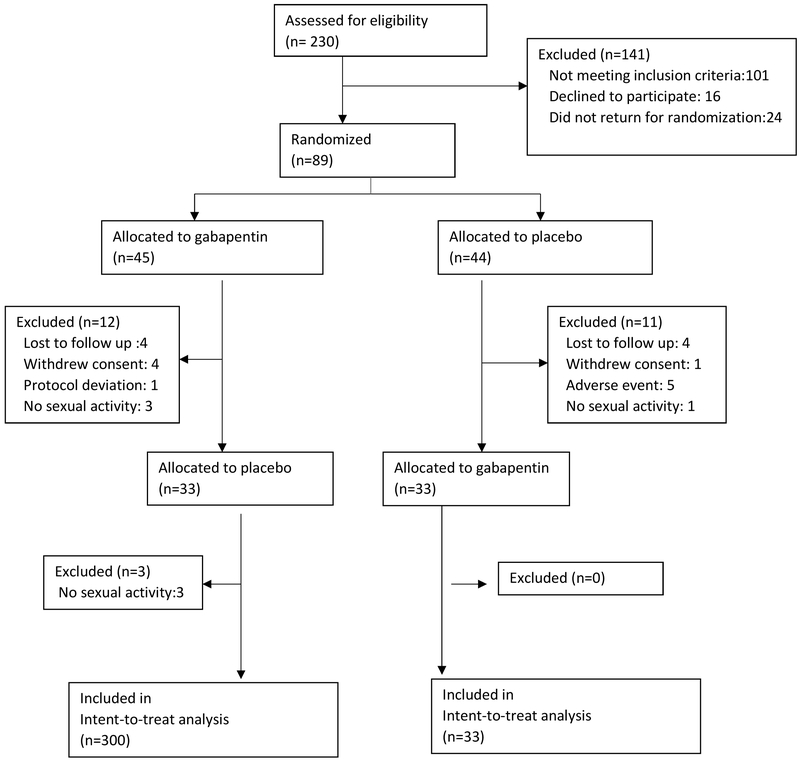

Figure 1 summarizes the flow diagram of progression from baseline visit to study completion. Of the 230 women screened, 89 met entry criteria and were randomized, 66 completed the trial, and 63 participants had complete data on the full scale at study completion. Of the 141 participants who were excluded, 101 did not meet inclusion criteria, 16 decided not to participate in the trial, and 24 did not return for drug randomization. Of the 89 individuals randomly assigned to study drug, eight were lost-to-follow up, five withdrew consent, five were removed by research staff because of adverse events, one was removed for a protocol deviation, and seven participants were not sexually active. Data was analyzed by Intention to treat with no missing imputation.

Figure 1.

Flow Diagram. Seven participants were not sexually active during one or both treatment arms and were not included in the full-scale analysis Data were analyzed using true intention-to-treat with no missing imputations

Demographic and baseline characteristics

Demographic and baseline characteristics at randomization are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in distribution of any of the variables between the gabapentin and placebo crossover phases. The mean age of the symptomatic women was 37,. most had attended college, the majority had their vulvodynia pain duration of over 5 years, about 25% had a history of sexual abuse, about 25% were taking oral contraceptives, 7 participants were using hormone therapy, and 2 were taking selective serotonergic reuptake inhibitors. Approximately half of the participants had primary onset and half had secondary onset of PVD. The mean age of vulvodynia pain-free control was 31 years, with 48% reporting their race as black (compared to 68% of symptomatic women).

Table 1:

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants

| Participants, No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Placebo first (n = 44) |

Gabapentin first (n = 45) |

|

| Age (mean/SD) | 35.5 (11.2) | 37.6 (12.7) | |

| Less than 52 years | 41 (93.2) | 38 (84.4) | |

| 52 years or older | 3 (6.8) | 7 (15.6) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 14 (31.8) | 16 (35.6) | |

| Black | 29 (65.9) | 29 (64.4) | |

| More than one race | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Educational status | |||

| College | 29 (65.9) | 27 (60.0) | |

| No college | 15 (34.1) | 18 (40.0) | |

| Duration of pain, years | |||

| 5 years or less | 17 (38.6) | 17 (37.8) | |

| Greater than 5 years | 27 (61.4) | 28 (62.2) | |

| History of sexual abuse | |||

| Yes | 10 (22.7) | 13 (28.9) | |

| No | 34 (77.3) | 32 (71.1) | |

| Onset | |||

| Primary | 21 (47.7) | 21 (46.7) | |

| Secondary | 22 (50.0) | 23 (51.1) | |

| Not reported | 1 (2.3) | 1 (2.2) | |

Data are reported according to sequence of treatment.

Nearly all intervention participants (88 of 89) were therapeutically naive to gabapentin. Comparison of the 23 individuals who failed to complete the randomized phase found no difference in age, race, years of education, marital status, or duration of disease compared with participants completing the randomized phase.

Female Sexual Function Index

Participants had substantially lower FSFI scores compared to vulvodynia pain-free controls (adjusted mean difference for full scale was 8.9, 95% CI: 7.0–10.9, P<.0001) (Table 2). Gabapentin significantly improved scores on the full scale over placebo among participants (mean difference 1.3, 95% CI: 0.4–2.2; P=0.008) (Table 3). Similarly, compared to placebo, gabapentin improved sexual desire (mean difference 0.2, 95% CI: 0.0–3.3; P=0.04), arousal (mean difference 0.3, 95% CI: 0.1–0.5; P=0.004), and satisfaction (mean difference 0.3, 95% CI: 0.0–0.5; P=0.02) domains, but did not improve orgasm, lubrication, or pain domains. Results with completer analysis were similar to treatment outcomes with intent-to-treat analysis.

Table 2:

Baseline Female Sexual Function Index scores in participants compared to matched vulvodynia pain-free controls a

| FSFI Scorea |

N | Participants adjusted mean (95% CI)b |

N | Controls adjusted mean (95% CI) |

Adjusted mean difference |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fullc | 56 | 20.7 (17.3-22.9) | 53 | 29.0 (25.7-32.3) | 8.9 (7.0–0.9) | <0.0001 |

| Desire | 89 | 2.6 (2.2-3.1) | 55 | 3.7 (3.1-4.3) | 1.1 (0.6–1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Arousal | 60 | 3.8 (3.2-4.4) | 55 | 5.2 (4.5-6.0) | 1.4 (0.9–1.9) | <0.0001 |

| Lubrication | 60 | 4.1 (3.6-4.6) | 54 | 5.5 (4.9-6.1) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | <0.0001 |

| Orgasm | 60 | 3.9 (3.1-4.6) | 55 | 4.8 (3.9-5.7) | 1.0 (0.4–1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Satisfaction | 60 | 3.7 (3.1-4.3) | 54 | 4.9 (4.1-5.6) | 1.2 (0.7–1.7) | <0.0001 |

| Pain | 57 | 2.3 (1.9-2.8) | 53 | 5.8 (5.3-6.3) | 3.5 (3.2–3.8) | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

FSFI Score ranges: Full scale, 2 (sexual dysfunction) – 36 (no sexual dysfunction); desire, 1.2 (no desire) – 6 (very high desire); arousal, 0 (no arousal)– 6 (very high arousal); lubrication, 0 (impossible)– 6 (not difficult); orgasm, 0 (impossible) – 6 (not difficult); satisfaction, 0.8 (very dissatisfied) – 6 (very satisfied); and pain, 0 (very high) – 6 (none at all).

Based on general linear model, adjusted for age, race, and site. Intention to treat, no missing imputation.

The full scale score was included in those participants who were sexually active.

Table 3:

Comparison of Female Sexual Function Index scores between treatment groups

| FSFIa | N | Placebo adjusted mean (95% CI)b |

Gabapentin adjusted mean (95% CI) |

Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full scalec | 63 | 21.1 (18.1, 24.1) | 22.4 (19.4, 25.4) | 1.3 (0.4, 2.2) | 0.008 |

| Desire | 89 | 2.7 (2.3, 3.2) | 2.9 (2.4, 3.4) | 0.2 (0.0, 3.3) | 0.04 |

| Arousal | 68 | 4.2 (3.4, 4.9) | 4.4 (3.7, 5.2) | 0.3 (0.1, 0.5) | 0.004 |

| Lubrication | 68 | 4.1 (3.6, 4.7) | 4.2 (3.7, 4.8) | 0.1 (−0.1, 0.3) | 0.23 |

| Orgasm | 68 | 4.4 (3.7, 5.1) | 4.5 (3.7, 5.2) | 0.1 (−0.2, 0.3) | 0.7 |

| Satisfaction | 68 | 4.1 (3.5, 4.7) | 4.4 (3.8, 5.0) | 0.3 (0.0, 0.5) | 0.02 |

| Pain | 64 | 2.5 (1.8, 3.2) | 2.7 (2.0, 3.4) | 0.2 (−0.1, 0.5) | 0.23 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

FSFI Score ranges: Full scale, 2 (sexual dysfunction) – 36 (no sexual dysfunction); desire, 1.2 (no desire) – 6 (very high desire); arousal, 0 (no arousal)– 6 (very high arousal); lubrication, 0 (impossible)– 6 (not difficult); orgasm, 0 (impossible) – 6 (not difficult); satisfaction, 0.8 (very dissatisfied) – 6 (very satisfied); and pain, 0 (very high) – 6 (none at all).

Based on mixed model, adjusted for period, treatment and center. Intention to treat, no missing imputation.

The full scale score was included in those participants who were sexually active.

Following gabapentin treatment, participants scores remained significantly lower than vulvodynia pain-free controls on the full scale (mean difference 6.9, 95% CI: 4.7-9.1; P<0.001), desire (mean difference 0.8, 95% CI: 0.4-1.3, P=0.0004), arousal (mean difference 1.2, 95% CI: 0.7-1.7; P<0.0001), satisfaction (mean difference 1.0, 95% CI: 0.5-1.5; P<0.0001), orgasm (mean difference 0.8, 95% CI:0.2-1.4 P=0.005), lubrication (mean difference 1.1, 95% CI: 0.7-1.5; P<0.0001) and pain (mean difference 2.4, 95% CI: 1.9-2.9; P<0.0001) domains.

Pelvic muscle pain to standardized digital force

Stratifying baseline provoked pelvic muscle pain severity scores into above median, “high muscle pain severity” and below median, “low muscle pain severity”, gabapentin improved the total FSFI of vulvodynia-afflicted subjects with high muscle pain severity (mean difference: 1.6, 95% CI: 0.3-2.8, P=0.02) but not with low muscle pain severity (Table 4). High muscle pain severity also predicted a gabapentin effect on improved FSFI arousal score (0.3, 95% CI: 0.1-0.6, P=0.01) and a trended toward improved FSFI pain score (0.4, 95% CI: 0.02-0.9, P=0.04) although the pain domain did not achieve statistical significance, following correction for multiple comparisons of FSFI domains.

Table 4:

Relationship between baseline pelvic muscle pain severity and treatment outcome

| Baseline pelvic muscle pain severitya |

FSFIb | N | Placebo adjusted mean (95% CI)c |

Gabapentin adjusted mean (95% CI) |

Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 or less | Full scaled | 28 | 21.0 (17.7-24.2) | 22.0 (18.8 – 25.2) | 1.0 (−0.5-2.4) | 0.19 |

| Desire | 43 | 2.7 (2.1-3.2) | 2.9 (2.4-3.4) | 0.2 (−0.0-0.5) | 0.07 | |

| Arousal | 32 | 4.2 (3.4-5.0) | 4.4 (3.6-5.6) | 0.2 (−0.1-0.5) | 0.14 | |

| Lubrication | 32 | 4.0 (3.5-4.6) | 4.2 (3.6-4.7) | 0.1 (−0.1-0.4) | 0.28 | |

| Orgasm | 32 | 4.5 (3.8-5.3) | 4.4 (3.6-5.1) | −0.2 (−0.5-0.2) | 0.35 | |

| Satisfaction | 32 | 4.0 (3.4-4.7) | 4.3 (3.7-5.0) | 0.3 (−0.1-0.7) | 0.10 | |

| Pain | 28 | 2.7 (1.9-3.4) | 2.6 (1.8-3.3) | −0.1 (−0.6-0.3) | 0.59 | |

| 5 or greater | ||||||

| Full | 35 | 21.4 (17.6-25.2) | 23.0 (19.1-26.8) | 1.6 (0.3-2.8) | 0.02 | |

| Desire | 46 | 2.9 (2.2-3.5) | 3.0 (2.4-3.2) | 0.1 (−0.1-0.4) | 0.24 | |

| Arousal | 36 | 4.1 (3.2-5.1) | 4.5 (3.5-5.4) | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | 0.01 | |

| Lubrication | 36 | 4.4 (3.7-5.1) | 4.5 (3.8-5.2) | 0.1 (−0.2-0.3) | 0.51 | |

| Orgasm | 36 | 4.2 (3.3-5.2) | 4.5 (3.5-5.4) | 0.2 (−0.1-0.6) | 0.16 | |

| Satisfaction | 36 | 4.2 (3.4-5.0) | 4.5 (3.7-5.3) | 0.3 (−0.1-0.6) | 0.10 | |

| Pain | 36 | 2.2 (1.4-3.1) | 2.7 (1.8-3.6) | 0.4 (0.02-0.9) | 0.04 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

A composite pain severity score the mean NRS (0 = no pain to 10 = worse possible pain) for the selected three applied forces (0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 kg/cm) at the two Iliococcygeus muscle regions.

FSFI Score ranges: Full scale, 2 (sexual dysfunction) – 36 (no sexual dysfunction); desire, 1.2 (no desire) – 6 (very high desire); arousal, 0 (no arousal)– 6 (very high arousal); lubrication, 0 (impossible)– 6 (not difficult); orgasm, 0 (impossible) – 6 (not difficult); satisfaction, 0.8 (very dissatisfied) – 6 (very satisfied); and pain, 0 (very high) – 6 (none at all).

Based on mixed model, adjusted for period, treatment and center. Intention to treat, no missing imputation.

The full scale score was obtained in those participants who were sexually active and where pelvic muscle to standardized applied pressure was performed.

The mean daily dose of gabapentin during maintenance was 2,476 ±866 mg. Compliance rate, determined by retained container pill count, was 94.7%. The incidence of adverse effects was slightly higher, but not significantly different, with gabapentin compared to placebo: Rhinitis (11.2% vs 4.5%), dizziness (10.1% vs. 3.4%), nausea (8.9% vs. 3.4%: P = .10), headache (7.9% vs. 5.6%), somnolence (7.9% vs 4.5%), bacterial vaginosis (7.9% vs. 4.5%), and fatigue (5.6% vs. 1.1%). No serious adverse events occurred during gabapentin treatment.

DISCUSSION

The etiology of vulvodynia is unknown and likely multifactorial, making diagnosis and treatment a clinical challenge. The 2015 Consensus Terminology Classification of Persistent Vulvar Pain addressed this challenge by providing definitions for vulvar pain disorders, including vulvodynia (13). This classification recognized potential factors associated with vulvodynia, including musculoskeletal disorders. It recognizes the role of central sensitization which plays a role in neurologic interpretation of pain. While impact of this classification on diagnostic and treatment algorithms remains unclear, it provides consistency in terminology for both research and clinical settings. It additionally offers clinicians a systematic approach to the vulvodynia patient and may aid in both differential diagnosis and choice of therapeutic intervention.

Evaluation of vulvodynia requires a detailed history, including sexual and psychosocial impact of pain. Examination should exclude other vulvovaginal disorders. Palpation of the levator muscles immediately inside the vagina is necessary to assess for tenderness, indicating possible pelvic floor dysfunction. Clinically this palpation is performed manually and interpretation subjective. In our research setting, a more objective test of levator muscle tenderness was performed using a vaginal algometer. This devise consists of a pressor sensor that is inserted into the vagina, attached to the index finger of the examining hand, allowing an application of controlled force.

The original study failed to show a significant improvement in overall pain with gabapentin versus control as determined by the Tampon Test as the primary outcome measure. Correlation between daily tampon pain with FSFI scores showed a negative, but not statistically significant correlation with total FSFI scores as well as all FSFI domains. This relationship persisted with combined or separated treatment and control periods.

In our secondary analysis, the impact of gabapentin on sexual function was evaluated since Gabapentin has been associated with improvement in muscular conditions such as fibromyalgia. This was appropriate since in this trial, women with pain anatomically located to deeper pressure specifically located over muscle groups were recruited and randomized. This secondary analysis showed an improvement in sexual function in women with higher baseline muscle pain severity score, suggesting the effect of gabapentin may be on reducing muscle pain. This is consistent with the conclusion of the primary analysis in that there was no correlation with decreased pain with gabapentin when measured as a function of the tampon test, which measures a more superficial peripheral nerve response. This secondary outcome suggests that gabapentin treatment might be more beneficial in women with PVD who have their pain triggered by pressure on the pelvic floor. Overall, these data suggested that Gabapentin was more effective than placebo in improving overall sexual function as measured by the FSFI, with overall score increased by 1 between gabapentin and placebo(p=0.008). Our overall pretreatment score range was 17.3-22.9. Data from several studies which used FSFI as an outcome measure for vulvodynia interventions reported an average upper range of pretreatment FSFI score 17, with posttreatment scores up to 22.68, which shows a numerically greater impact of treatment, but also with lower scores than our normal controls. (15, 16, 17) Further, the statistically significant increase in FSFI score suggests a beneficial gabapentin effect on sexual function over placebo. The individual domains of desire, arousal and satisfaction were statistically significantly increased, with the most significant improvement in the domain of arousal (p=0.004). As the most significant improvement was seen in the arousal domain, a primarily central response is suggested, versus lubrication which measures peripheral function, and which was not statistically significantly improved.

The individual domain of pain was not statistically improved, suggesting that sexual function may not be directly correlated with overall pain or tenderness due to the intervention’s peripheral effect on muscle, but severity of the muscle dysfunction.

That is, when looking at these data in accordance with our hypothesis that gabapentin would improve sexual functioning secondary to a beneficial effect on muscle pain, we found that Gabapentin intervention had a better overall response in women with a higher median baseline algometer pain score (≥5/10). These women showed a significant change in overall FSFI measured sexual function, as well the domains of arousal and, as opposed to the entire cohort, pain. This suggests that in this cohort of women with increased muscle pain at baseline, both a central mechanism of action (arousal) and a peripheral mechanism of action (pain) may lead to better sexual function.

The second component of the study, which matched our cohort by age and race with women who did not report vulvar pain suggested that not only did women with PVD have significantly lower FSFI overall sexual function, but, even after treatment the improvement in the PVD cohort, the improvement did not approach the level of sexual functioning in women without the disorder.

Our data, although statistically significant, showed minimal numeric improvement between gabapentin over placebo as measured by the FSFI. The increase in placebo response may have been affected by the instructional exams and clinical counseling given to participants. These non-pharmacologic interventions may have contributed to a more positive attitude towards sexual function. The clinical significance of the FSFI change is difficult to assess.

Our findings add to the literature in the clinical management of vulvodynia by demonstrating a small, but significant improvement of sexual function in women treated with gabapentin over placebo. . The key clinical relevance, however, may be the better response of women with higher median algometer pain scores, which clinically may translate to considering gabapentin as an initial treatment option in women with PVD who report more severe muscle pain on pelvic floor exam.

The strengths of our study include a demographically and geographically diverse population, use of validated questionnaires and the use of a standardized muscle pain score (algometer). Our study limitations include a treatment duration of only 6 weeks and lack of a no-treatment arm to determine true placebo effect. Finally, although our control group was well matched and screened, only a small portion (N=10) underwent physical exam and CST.

Conclusions

Gabapentin improved sexual function in this group of women with provoked vulvodynia, although overall sexual function remained lower than women without the disorder. The highly significant increase in the arousal domain of the FSFI suggests a central mechanism of response. Those women with median algometer pain scores of ≥5/10 had a greater response overall, and their improvement of the pain domain as well as the arousal domain suggests both a central and peripheral action in this cohort. Gabapentin should be considered for treatment in women with PVD who have increased pelvic muscle pain as noted on exam.

Implications and Contributions:

A. Why was this study conducted?

This study evaluated whether gabapentin is effective versus placebo in improving sexual function as measured by Female Sexual Function Index in women with provoked vulvodynia (PVD) Another purpose determined if sexual function before or after treatment would approach that of women without PVD.

B. What are the key findings?

Gabapentin was more effective than placebo in improving sexual function. Women with greater muscle pain on exam responded better than those with less pain, both overall and in the arousal and pain domains. Sexual function before or after treatment was significantly lower in women with PVD than those without.

C. What does this study add to what is already known ?

Improvement of sexual function in women with PVD treated with gabapentin versus placebo has not been previously demonstrated. The better response of women with PVD with prominent muscle pain suggests that gabapentin be considered for their treatment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank the members of the Gabapentin Study Group: Diane Dawicki (Robert Wood Johnson Medical School), Adrienne Bonham, Robert Dworkin, Pavan Balabathula, Candi Bachour, Ian Brooks, Turid Dulin, Frank Horton, Mark Sakauye, Laura Thoma, Emanuel Villa, Jiajing Wang (University of Tennessee Health Science Center), and Frank Ling (Women’s Health Specialists, Germantown, TN).

We would also like to acknowledge members of the Data and Safety Monitoring Board. Paul Nyirjesy, Chair (Drexel University), Sue Fosbre (Rutgers-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School), Dianne Hartmann, John Queenen (University of Rochester Medical Center), William Pulsinelli (University of Tennessee Health Science Center), Deanne Taylor (Rutgers-School of Arts and Sciences), and Ursula Wesselmann (University of Alabama School of Medicine).

Financial support: Supported by R01 HD065740 (to Dr. Brown) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Office of Women’s Health Research and University of Tennessee General Clinical Research Center. Depomed, Inc. provided gabapentin extended release and matching placebo.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement: the authors report no conflict of interest.

Clinical trial registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01301001

Condensation: Women with provoked vulvodynia showed improvement in sexual function with gabapentin treatment versus placebo.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harlow BL, Stewart EG. A population-based assessment of chronic unexplained vulvar pain: have we underestimated the prevalence of vulvodynia? J Am Med Women’s Assoc 2003;58:82–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Mar Ther 2000;26:191–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips NA, Brown C, Bachmann G, Wan J, Wood R, Ulrich D, Bachour C, Foster D. Relationship between nongenital tender point tenderness and intravaginal muscle pain intensity: Ratings in women with provoked vestibulodynia and implications for treatment. Am J ObGyn 2016: November [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold LM, Goldenberg DL, Stanford SB, Lalonde JK, Sandhu HS, Keck PE Jr, et al. Gabapentin in the treatment of fibromyalgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Arthritis and Rheumatism 2007;56:1336–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reed BD, Harlow SD, Sen A, Legocki LJ, Edwards RM, Arato N, et al. Prevalence and demographic characteristics of vulvodynia in a population-based sample. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012;206:170.e1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedrich EG. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Reprod Med 1987;32 :110–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergeron S, Binik YM, Khalife S, Pagidas K, Glazer HI. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: reliability of diagnosis and evaluation of current diagnostic criteria. Obstet Gynecol 2001;98:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster DC, Kotok MB, Huang LS, et al. Oral desipramine and topical lidocaine for vulvodynia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:583–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown C, Bachmann GA, Wan J, Foster DC for the Gabapentin (GABA) Study Group. Gabapentin for the Treatment of Vulvodynia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 131(6):1000–1007, June 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rakoff AE. The endocrine factors in pelvic tumors, with a discussion of the Papanicolaou smear method of diagnosis. Radiology 1948;50:190–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiegel M, Meston C, Rosen R. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI)L Cross-validation and development of clinical cutoff scores. J Sex Mar Ther 2005;31:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viangteeravat T, Brooks IM, Smith EJ, et al. Slim-Prim: a biomedical informatics database to promote translational research. Perspect Health Inf Manag 2009;6:6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH and IPPS consensus terminology and classification of persistent vulvar pain and vulvodynia. Obstet Gynecol 2016;127:745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pelletier F; Girardin M; Humbert P; Puyraveau M; Aubin F; Parratte B. Long-term assessment of effectiveness and quality of life of OnabotulinumtoxinA injections in provoked vestibulodynia. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 30(1):106–11, 2016. January. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlaeger JM; Xu N; Mejta CL; Park CG; Wilkie DJ. Acupuncture for the treatment of vulvodynia: a randomized wait-list controlled pilot study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 12(4):1019–27, 2015. April [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McDonald JS; Rapkin AJ. Multilevel local anesthetic nerve blockade for the treatment of generalized vulvodynia: a pilot study. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 9(11):2919–26, 2012. November. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]