Abstract

Background:

Asthma is an allergic airway inflammation-driven disease that affects more than 300 million people worldwide. Targeted therapies for asthma are largely lacking. Although asthma symptoms can be prevented from worsening, asthma development can’t be prevented. Cdc42 GTPase has been shown to regulate actin cytoskeleton, cell proliferation and survival.

Objectives:

To investigate the role and targeting of Cdc42 in Th2 cell differentiation and Th2-mediated allergic airway inflammation.

Methods:

Post-thymic Cdc42-deficient mice were generated by crossing Cdc42flox/flox mice with dLckicre transgenic mice in which Cre expression is driven by distal Lck promoter. Effects of post-thymic Cdc42 deletion and pharmacological targeting Cdc42 on Th2 cell differentiation were evaluated in vitro under Th2-polarized culture conditions. Effects of post-thymic Cdc42 deletion and pharmacological targeting Cdc42 on allergic airway inflammation were evaluated in ovalbumin- and/or house dust mite-induced mouse models of asthma.

Results:

Post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 led to reduced peripheral CD8+ T cells and attenuated Th2 cell differentiation, with no effect on closely related Th1, Th17 and induced regulatory T (iTreg) cells. Post-thymic Cdc42 deficiency ameliorated allergic airway inflammation. The selective inhibition of Th2 cell differentiation by post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 was recapitulated by pharmacological targeting of Cdc42 with CASIN, a Cdc42 activity-specific chemical inhibitor. CASIN also alleviated allergic airway inflammation. CASIN-treated Cdc42-deficient mice showed comparable allergic airway inflammation to vehicle-treated Cdc42-deficient mice, indicative of negligible off-target effect of CASIN. CASIN had no effect on established allergic airway inflammation.

Conclusion & Clinical Relevance:

Cdc42 is required for Th2 cell differentiation and allergic airway inflammation and rational targeting Cdc42 may serve as a preventive but not therapeutic approach for asthma control.

1. INTRODUCTION

T cells play a critical role in mediating adaptive immunity to a variety of pathogens.1 T cells are developed in the thymus. The most immature populations in the thymus are comprised of CD4−CD8− thymocytes. CD4−CD8− thymocytes differentiate to CD4+CD8+ cells. CD4+CD8+ cells then differentiate to CD4+ or CD8+ T cells or CD4+Foxp3+ natural regulatory T cells (nTreg). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells migrate to peripheral tissues, where they are maintained as naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.2,3

In response to antigen stimulation, naïve T cell are activated and differentiated into effector T cells. CD4+ effector T cells include T helper (Th) 1, Th2 and Th17 cells.1, 3–5 Th cells are characterized by secreting particular profiles of cytokines and exerting distinct functions in vivo. For example, Th1 cells produce IFN-γ and mediate cellular immunity against intracellular pathogens and autoimmunity.1, 4, 5 Th17 cells produce IL-17 and are important for eliminating extracellular pathogens and for autoimmunity.6, 7 Th2 cells secret IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13, and play a key role in humoral immunity, allergy, and asthma, an allergic airway inflammation-driven disease characterized by lung eosinophilia, elevated serum immunoglobulin E (IgE), and airway hyperresponsiveness and goblet cell metaplasia.1, 4, 5, 8–10 On the other hand, CD4+ naïve T cells can also differentiate to CD4+Foxp3+ induced regulatory T cells (iTreg) that together with nTreg, act to maintain immune tolerance by inhibition of T cell proliferation and effector T cell function.11

Cdc42 of the Rho small GTPase family is an intracellular signal transducer that cycles between an inactive GDP-bound form and an active GTP-bound form.12 Cdc42 has been shown to regulate actin cytoskeleton reorganization, cell migration, proliferation, survival and oncogenesis.13–16 By T cell-specific Cdc42 deletion, we have recently found that Cdc42 promotes thymocyte development, peripheral T cell homeostasis and iTreg cells but suppresses T cell activation, Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation, with no effect on Th2 cells.17–19

In this study, we aimed to investigate the physiological role of Cdc42 in Th2 cell differentiation and function. We achieved post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 and found that post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 inhibited Th2 differentiation with no effect on Th1, Th17 and iTreg cells. Post-thymic Cdc42 deletion ameliorated Th2-mediated allergic airway inflammation. Pharmacological inhibition of Cdc42 with CASIN, a Cdc42 activity-specific inhibitor,20 was able to recapitulate the effects of post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 on selective inhibition of Th2 differentiation and on alleviation of allergic airway inflammation. However, CASIN could not ameliorate established allergic airway inflammation. Thus, Cdc42 emerges as a critical regulator of Th2 cell differentiation and may be a preventive, but not therapeutic target, for asthma.

2. METHODS

2.1. Mice

Cdc42flox/flox mice were generated as previously described.17, 21 Cdc42flox/flox mice were mated with dLCKiCre transgenic mice, in which Cre expression is controlled by distal Lck promoter,22 to generate Cdc42flox/floxdLCKiCre mice. Mouse genotyping was performed by PCR. Age- (8–10 weeks) and sex-matched mice were used in each experiment. Animals were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Research Foundation in compliance with the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee protocols (2017–0025).

2.2. Ovalbumin (OVA)-induced allergic airway inflammation

Allergic airway inflammation was induced as described in our previous reports.23–25 Briefly, mice were immunized i.p. with 50 μg of OVA (Grade V; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) in 100 μl (2 mg) of alum (Imject Alum; Pierce, IL) on day 0 and day 7. On day 14, the mice were challenged two times (60 min each delivered 4 h apart) with aerosolized 1% OVA dissolved in PBS by an Omron NE-C25 Nebulizer (Omron Healthcare, Bannockburn, IL). On day 15, the mice were challenged one more time. For established allergic airway inflammation model, the mice were re-challenged on day 46 and 47. Control mice were challenged with PBS. Where indicated, CASIN was injected i.p. into the mice. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after the last challenge or re-challenge. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluids were aspirated and centrifuged and total cells in the pellet were counted by using a hemacytometer. Differential cell counts on >400 cells were performed on cytospins stained with Shandon Kwik-Diff Stain kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). The BAL fluid from each mouse was concentrated to 0.5 ml by centrifugation with an Amicon Ultra-4 filter unit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) for the determination of cytokines by ELISA. For lung histology, the lower lobe of the right lung was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, cut into 4 μm sections, and processed for hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) staining. Lung tissue mRNA was analyzed by quantitative Real-time RT-PCR. Serum levels of OVA-specific IgE was measured by ELISA with the use of biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgE (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA), as our previous report.25

2.3. House dust mite (HDM)-induced allergic airway inflammation

The murine airway hyperresponsiveness was induced according to our recent reports26, 27 with modifications.28, 29 Briefly, mice were inoculated intratracheally (i.t.) with 40 μg of house dust mite (HDM, Stallergenes Greer, Lenoir, NC) in 40 μl PBS 3 times a week for 5 wks. Control mice were inoculated i.t. with PBS alone. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after the last inoculation. BAL fluid was aspirated and centrifuged. Total cells and differential cell counts in the pellet were performed. Cytokines in the BAL fluid were determination by ELISA. For lung histology, the lower lobe of the right lung was fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, cut into 4 μm sections, and processed for hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) and Periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining. Lung tissue mRNA was analyzed by Real-time PCR. HDM-specific IgE was measured by ELISA with the use of biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgE (BD Bioscience), as our previous report.26

2.4. Quantitative Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from lung tissues or Th2 cells with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and cDNA was prepared by using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed with the Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG w/RO or TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The data were normalized to the 18S reference. Primers were designed with OLIGO 4.0 software as reported.24

2.5. T cell activation and differentiation

Sorted naive T cells (CD62LhiCD44lo) were used for T cell activation and differentiation. Naïve T cells were activated with plate-bound anti-CD3 (10 μg/ml) plus soluble anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) (BD Bioscience). For T cell differentiation, CD4+ naïve T cells were differentiated into Th0, Th1, Th2, Th17, or iTreg cells as previously reported.23–25, 30 Briefly, CD4+ T cells were stimulated by anti-CD3/CD28 for 4 d with IL-2 (20 ng/ml) in the presence of anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-4 (both 10 μg/ml, for Th0), anti-IL-4 and IL-12 (20 ng/ml, for Th1), anti-IFN-γ and IL-4 (20 ng/ml, for Th2). For iTreg and Th17 conditions, CD4+ T cells were stimulated by anti-CD3/CD28 for 4 d with anti-IFN-γ and anti-IL-4 (both 10 μg/ml) in the presence of IL-2 (20 ng/ml) plus TGF-β1 (5 ng/ml, for Treg), or TGF-β1 plus IL-6 (10 ng/ml, for Th17) (all from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Cells were restimulated with PMA (25 ng/ml) plus ionomycin (500 ng/ml) (Sigma, St Louis, MO) for 5 h with GolgiStop (BD Bioscience) in the last 2 h for intracellular cytokine staining; or without GolgiStop for cytokine assays in the culture supernatants by ELISA. Where indicated, CASIN (Chembridge Corporation, San Diego, CA) was added to the cultures.

2.6. Flow cytometry

Cells were incubated with anti-CD16/32 (2.4G2) (BD Bioscience) to block FcγR II/III, and then stained with various conjugated antibodies as indicated. BD Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Bioscience) was used for intracellular cytokine staining. BrdU incorporation was assayed by a BrdU Flow kit per manufacturer’s protocol (BD Bioscience). Apoptosis was evaluated with an Annexin-APC Flow kit (BD Bioscience) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Stained cells were analyzed by FACSCalibur or FACSCanto with FACSDiva (BD Bioscience) or FCS Express (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA) softwares.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 does not affect thymocyte development and CD4+ T cell homeostasis but dampens CD8+ T cell homeostasis

To investigate the effects of Cdc42 deletion on Th2 cell differentiation and function, we crossed Cdc42flox/flox mice with dLCKiCre mice in which Cre expression is controlled by distal Lck promoter and begins at a late stage of thymocyte development (Figure S1A),22 in contrast to LCKCre whose expression starts at early stage of thymocyte development (CD4−CD8− thymocytes) (Figure S1A). The resultant Cdc42flox/floxdLCKiCre (hereafter referred to as Cdc42−/−) mice lost Cdc42 expression in peripheral T cells but not thymocytes (Figure S1B). The mutant mice showed intact thymocyte development. The frequency and/or absolute numbers of total thymocytes and all thymocyte subsets were similar between wild-type (WT: Cdc42flox/flox) and Cdc42−/− mice (Figure S1C). Although the frequency of CD4+Foxp3+CD25+ nTreg cells was modestly decreased, their absolute numbers were not changed (Figure S1D).

In the periphery, both the frequency and absolute numbers of CD8+ T cells were reduced in Cdc42−/− mice (Figure S1E). However, Cdc42 deficiency did not affect CD4+ T cell homeostasis (Figure S1E). Analysis of naïve (CD62L+CD44−) vs effector memory (CD62L−CD44+)/central memory (CD62L+CD44+) T cells revealed that naïve T cells were reduced but CD44+ effector memory/central memory T cells were increased in Cdc42−/− CD8+ T cell compartment, whereas these T cell subsets remained unchanged in Cdc42−/− CD4+ T cell compartment (Figure S1F). Consistent with these results, in vivo BrdU incorporation assay found that CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells in Cdc42−/− mice underwent homeostatic proliferation (Figure S2A). In addition, Annexin V/7AAD staining revealed an increased apoptosis in Cdc42−/− CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells (Figure S2B). The lack of effect of Cdc42 deletion on CD4+ T cell homeostasis might be due to less efficient deletion of Cdc42 by dLCKiCre whose recombination is known to be less frequent in CD4+ T cells than in CD8+ T cells.22 We thus performed genotyping of Cdc42 in splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from WT and Cdc42−/− mice. We found that Cdc42 gene was effectively deleted in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from Cdc42−/− mice (Figure S3). Collectively, these data suggest that Cdc42 regulates CD8+ but not CD4+ T cell homeostasis.

3.2. Post-thymic Cdc42 deficiency inhibits T cell activation in CD4+ but not CD8+ T cells and clonal expansion in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell compartment

We next evaluated the impact of Cdc42 deficiency on T cell activation and clonal expansion. We found that anti-CD3/CD28-stimulated T cell activation (Figure S4A), activation-induced cell death (Figure S4C) and clonal expansion (Figure S5A) were all significantly downregulated in Cdc42−/− CD4+ T cells. However, only clonal expansion was impaired in Cdc42−/− CD8+ T cells (Figure S5B vs. Figure S4B and Figure S4D). Therefore, in CD4+ T cells, Cdc42 appears to regulate both cell activation and clonal expansion, whereas in CD8+ cells, Cdc42 regulates clonal expansion but not activation.

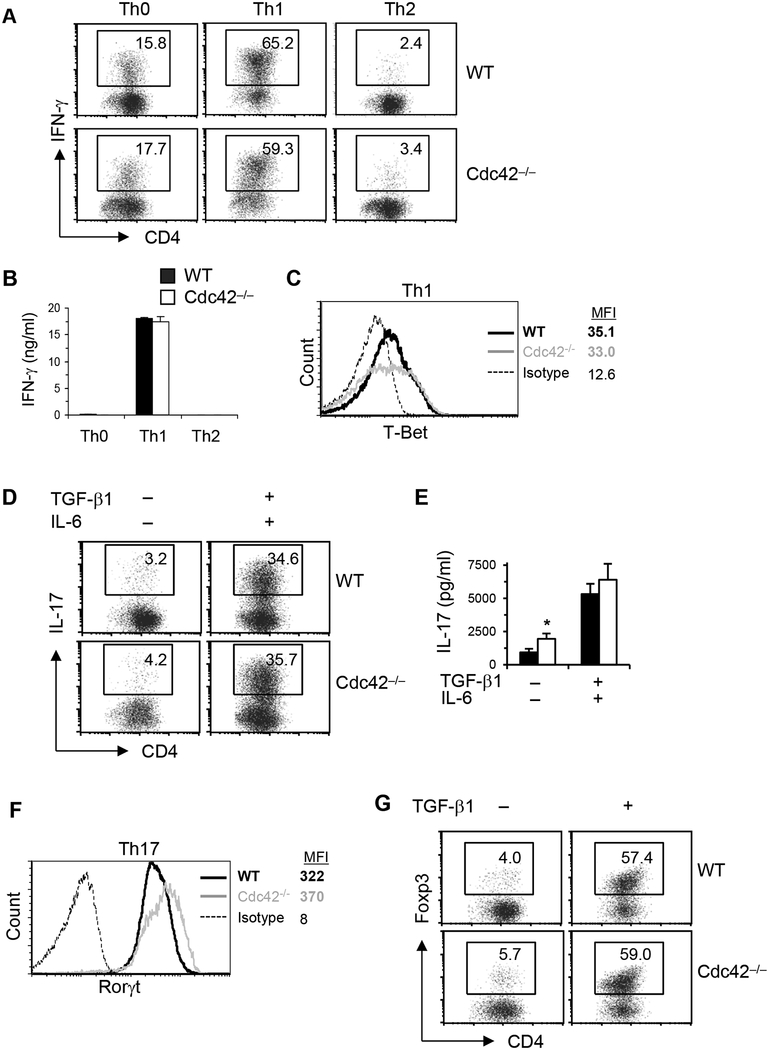

3.3. Post-thymic Cdc42 deficiency selectively suppresses Th2 cell differentiation

We then determined whether Cdc42 deletion affected Th and iTreg cell differentiation. Cdc42-deficient T cells appeared to retain their ability to differentiate into Th1 cells. Thus, the frequency of IFN-γ-producing cells and IFN-γ secretion were similar between Cdc42-deficient and WT T cells under polarized differentiation conditions (Figure 1A and B). The expression of T-Bet, a key Th1 transcriptional factor, was also not altered by the loss of Cdc42 (Figure 1C). Cdc42 deficiency also had no effect on TGF-β/IL-6-induced Th17 differentiation. As such, the frequency of IL-17+ cells, IL-17 secretion, and Th17 transcription factor RORγt were not affected by the loss of Cdc42, under Th17-skewing condition (Figure 1D–F). Furthermore, Cdc42 deficiency didn’t perturb TGF-β-induced differentiation of iTreg cells, as evidenced by intact Foxp3+ cells (Figure 1G). In contrast to its lack of effect on Th1, Th17 and iTreg cells, deficiency of Cdc42 significantly attenuated Th2 cell differentiation. In support, IL-4-producing cells, IL-4 secretion, and the activation/expression of Stat6 and GATA3, two transcriptional factors important for Th2 cell differentiation, were dramatically reduced in Cdc42-deficient T cells under neutral and/or polarized differentiation conditions (Figure 2A–D). Taken together, these data indicate that Cdc42 selectively regulates Th2 cell differentiation.

FIGURE 1.

Post-thymic Cdc42 deficiency has no effect on Th1, Th17 and iTreg differentiation. (A-C) Naïve CD4+ T cells were differentiated under Th0, Th1 or Th2 conditions for 4 days followed by PMA plus ionomycin restimulation for 5 h, in the presence or absence of BD GolgiPlug™ at the last 2 h. Cells were processed for CD4 surface staining and IFN-γ and T-Bet intracellular staining and flow cytometry analysis. Percentages of IFN-γ+CD4+ T cells are shown in representative dot plots (A). IFN-γ in the culture supernatants was collected from other sets of cultures without BD GolgiPlug™ and assayed by ELISA (B). Representative histogram of T-Bet is shown (C). (D-F) Naïve CD4+ T cells were differentiated under non-skewing (no TGF-β1/IL-6) or Th17 (TGF-β + IL-6) skewing culture conditions for 4 days followed by PMA plus ionomycin restimulation. The cells were processed for surface staining of CD4 and intracellular staining of IL-17 and Rorγt for flow cytometry analysis. Percentages of CD4+IL-17+ T cells are shown in representative dot plots (D). IL-17 in the culture supernatants was assayed by ELISA (E) Representative histogram of Rorγt is shown (F). (G) Naïve CD4+ T cells were differentiated under non-skewing (no TGF-β1) or iTreg (TGF-β) skewing culture conditions for 4 days followed by PMA plus ionomycin restimulation. The cells were processed for surface staining of CD4 and intracellular staining of Foxp3 for flow cytometry analysis. Percentages of Foxp3+ T cells are shown in representative dot plots. Results are representative of 5–8 mice. Error bars represent SD of triplicates. *P < 0.05.

FIGURE 2.

Post-thymic Cdc42 deficiency suppresses Th2 cell differentiation. Naïve CD4+ T cells were cultured with anti-CD3 or anti-CD3/CD28 for 2 d (A) or differentiated under Th0, Th1, or Th2 skewing conditions for 4 days and restimulated with PMA plus ionomycin for 5 h (B). The cells were collected for surface staining of CD4 and intracellular staining of IL-4. Percentages of CD4+IL-4+ T cells are shown in representative dot plots (A and B, Left) and summarized in bar graphs (A and B, Right). IL-4 in the culture supernatants was assayed by ELISA (C). The expression of pStat6 and Gata3 were detected by flow cytometry. Representative histograms are shown and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) is summarized in bar graphs (D). Results are representative of 5–8 mice. Error bars represent SD of triplicates. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

To explore the molecular mechanisms underlying Cdc42-regulated Th2 differentiation, we profiled global gene expression changes in Cdc42−/− Th2 cells by RNA-Seq. Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of the differentially expressed genes (p < 0.05) revealed that Cdc42 deficiency affected a number of pathways such as T helper cell differentiation pathway, 4–1BB signaling in T lymphocytes, and signaling that regulates nucleic acid metabolism (Figure S6A and B). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR verified the upregulation of TRAF1 and TNFRSF9 in 4–1BB pathway and of CMPK2 and CMAS in nucleic acid metabolism in Cdc42−/− Th2 cells (Figure S6C). IFN-γ in Th2 culture supernatants (Figure S6D) and Foxp3 expression (Figure S6E) were similar between both genotypes. These results suggest that Cdc42 plays an essential role in the regulation of immune signaling and nucleic acid metabolism in Th2 cells.

3.4. Post-thymic Cdc42 deficiency ameliorates OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation

Since Cdc42 regulates Th2 differentiation, we investigated whether Cdc42 was necessary for an optimal Th2-mediated inflammatory response in vivo in a classical OVA-induced mouse model of asthma (Figure 3A).23–25 Total numbers of BAL cells in WT mice challenged with OVA had over 100-fold increase as compared to PBS-challenged mice (Figure 3B). Differential cell counting revealed that eosinophils accounted for most of this increase (Figure 3B and C). However, Cdc42 deficiency led to a dramatic reduction in total numbers of BAL cells, particularly owing to markedly decreased eosinophils (Figure 3B and C). Lung histological analysis found that OVA-challenged WT mice showed a prominent inflammatory response with massive perivascular and peribronchial infiltration, whereas this inflammatory response was markedly reduced in Cdc42-deficient mice (Figure 3D).

FIGURE 3.

Post-thymic Cdc42 deficiency inhibits OVA-induced allergic airway inflammation. (A) WT and CDC42−/− mice were immunized i.p. with OVA and then challenged with aerosolized OVA or PBS as control. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after the last challenge. (B) Quantification of total BAL cells (Left), eosinophils (Eo), macrophages (Mϕ), neutrophils (Neu), and lymphocytes (Lym) (Right) in BAL fluids. (C, D) Representative Kwik-Diff staining for BAL cytospins (C, scale bar, 20 μm) and H&E staining of lung tissue sections (D, scale bar, 100 μm). (E) Cytokine/chemokine levels in BAL fluids determined by ELISA. (F) mRNA levels of cytokines and chemokines in lung tissues determined by real-time PCR. Data are normalized to an 18S reference and expressed as arbitrary units. (G) OVA-specific IgE levels in serum of mice immunized and challenged with OVA. (H) Cytokine levels, as determined by ELISA, in 2d-cultured supernatants of draining trachea lymph node cells isolated from OVA-challenged mice and restimulated in vitro with anti-CD3/CD28. Results are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars represent SE. n = 5–8. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. OVA-challenged and/or anti-CD3/CD28-restimulated WT control.

We reasoned that the inhibitory effect of Cdc42 deficiency on allergic airway inflammation might be attributed to reduced Th2 cytokine secretion in Cdc42−/− mice as seen in vitro. In support of this notion, IL-4 and IL-5 in BAL fluids from Cdc42−/− mice were markedly reduced in response to OVA challenge; whereas Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and Th17 cytokine IL-17 were not affected by the loss of Cdc42 (Figure 3E). The mRNA levels of these cytokines in the lungs followed similar patterns as protein levels in BAL (Figure 3F). Eotaxin and MUC-5AC, two non-T cell-derived mediators of allergic airway inflammation,24, 31, 32 were also downregulated by Cdc42 deficiency (Figure 3E and F). Furthermore, serum OVA-specific IgE was decreased in Cdc42−/− mice (Figure 3G).

The results from the asthma model are consistent with a crucial role of Cdc42 in Th2 cell differentiation. To show direct evidence that Cdc42 modulates Th2 differentiation in vivo, we isolated trachea lymph node cells from OVA-challenged WT and Cdc42−/− mice, cultured the cells in the presence anti-CD3/CD28 for 2 days, and then detected Th2 cytokines in the culture supernatants. We found that IL-4 and IL-5 secretion from Cdc42−/− cells was significantly reduced compared to that from WT cells (Figure 3H). Together, th ese data support that Cdc42 regulates allergic airway inflammation through its effect on Th2 cell differentiation.

3.5. Pharmacological targeting Cdc42 suppresses Th2 differentiation and allergic airway inflammation

The inhibitory effects of genetic targeting Cdc42 on Th2 differentiation and allergy airway inflammation suggest that Cdc42 is a biologic target for asthma treatment. To test this notion, we investigated the effects of pharmacological targeting Cdc42 by CASIN, a novel Cdc42 activity-specific inhibitor developed by us.20 CASIN (10 μM) inhibited anti-CD3/CD28-induced activation of Cdc42 and its immediate downstream effector molecules PAK1 and PAK2 in T cells (Figure S7A). CASIN (30 mg/kg body weight)-treated mice showed normal thymocyte development (Figure S7B). In vivo CASIN treatment also had no effect on peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell homeostasis (Figure S7C). However, 10 μM and 20 μM of CASIN inhibited CD4+ T cell activation in vitro in a dose-dependent manner (Figure S8). Although it decreased IFN-γ+ Th0 cells, 10 μM of CASIN had no effect on Th1, Th17 and iTreg cell differentiation (Figure 4A–C and Figure S9A–C), reminiscent of post-thymic deletion of Cdc42. Importantly, 10 μM of CASIN recapitulated post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 in inhibition of Th2 cell differentiation (Figure 4D and E and Figure S9D). 20 μM of CASIN suppressed all of Th1, Th2, Th17 and iTreg differentiation (data not shown), indicative of its toxicity and/or off-target effect.

FIGURE 4.

Pharmacological targeting Cdc42 by Cdc42 inhibitor CASIN selectively suppresses Th2 differentiation. (A) Naïve WT CD4+ T cells were differentiated under Th0, Th1 or Th2 conditions for 4 days and restimulated with PMA plus ionomycin for 5 h in the absence (vehicle) or presence of CASIN (10 μM) throughout the culture. The cells were processed for IFN-γ intracellular staining. Percentages of CD4+IFN-γ + T cells are shown in representative dot plots (A, Left) and summarized in bar graph (A, Upper Right). IFN-γ in the culture supernatants was assayed by ELISA (A, Lower Right). (B) Naïve WT CD4+ T cells were differentiated under non-skewing or Th17 (TGF-β + IL-6) skewing conditions for 4 days and restimulated with PMA plus ionomycin in the absence (vehicle) or presence of CASIN (10 μM) throughout the culture. The cells were processed for CD4 surface staining and IL-17 intracellular staining. Percentages of CD4+IL-17+ cells are shown in representative dot plots. (C) Naïve WT CD4+ T cells were differentiated under non-skewing or iTreg (TGF-β) skewing conditions for 4 days and restimulated with PMA plus ionomycin in the absence (vehicle) or presence of CASIN (10 μM) throughout the culture. The cells were processed for CD4 surface staining and Foxp3 intracellular staining. Percentages of CD4+Foxp3+ cells are shown in representative dot plots. (D, E) Naïve WT CD4+ T cells were differentiated under Th0, Th1, or Th2 skewing conditions for 4 days and restimulated with PMA plus ionomycin for 5 h in the absence (vehicle) or presence of CASIN (10 μM) throughout the culture. Cells were processed for CD4 surface staining and IL-4 intracellular staining. Percentages of CD4+IL-4+ cells are shown in representative dot plots and summarized in bar graph (D). Th2 Cytokines in the culture supernatants were assayed by ELISA (E). Results are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars represent SD of triplicates. **P < 0.01.

Next we examined the effect of CASIN on allergic airway inflammation. WT mice were treated with CASIN daily starting one day before OVA immunization until one day before sacrifice (Figure 5A). We found that CASIN treatment significantly inhibited allergic airway inflammation. The infiltrating cells, particularly eosinophils, in BAL fluids (Figure 5B and C) and the lungs (Figure 5D) were markedly reduced in CASIN-treated mice. Consistently, inflammatory mediators including Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5, Eotaxin, MUC-5AC, Gob5, and IL-33 in BAL fluids and/or the lungs were downregulated, whereas Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and Th17 cytokine IL-17 were not changed by CASIN treatment (Figure 5E and F). Upon in vitro restimulation with anti-CD3/CD28, trachea lymph node cells from OVA-challenged CASIN-treated mice showed decreased secretion of Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-5, but not Th1 cytokine IFN-γ (Figure 5G), suggesting that CASIN suppresses allergic airway inflammation through its effect on Th2 cell differentiation. Interestingly, when CASIN treatment started after OVA immunization but before OVA challenge (Figure 6A), there was only a slight reduction of BAL cells (Figure 6B and C). The infiltrating cells in the lungs appeared similar (Figure 6D) and Th2 cytokines in BAL fluids also did not differ significantly (Figure 6E). As OVA immunization and challenge are thought to induce Th2 differentiation and inflammatory cell infiltration, respectively, our data suggest that CASIN, when employed before OVA immunization, alleviates allergic airway inflammation by inhibiting Th2 differentiation but not inflammatory cell recruitment into the lungs. Together, these results indicate that CASIN prevents the development of allergic airway inflammation/asthma.

FIGURE 5.

CASIN alleviates allergic airway inflammation. WT mice were injected i.p. daily with CASIN (30 mg/kg) or vehicle, starting 1 day before OVA immunization until 1 day before sacrifice (A). Total BAL cells and differential cell counts (B), representative Kwik-Diff staining for BAL cytospins (C), H&E staining of lung tissue sections (D), cytokine and eotaxin levels in BAL fluids (E), and mRNA levels of cytokines and chemokines in lung tissues determined by real-time PCR (F) are shown. Draining trachea lymph node cells were isolated from OVA-challenged mice and restimulated in vitro with anti-CD3/CD28 for 2 days. Cytokine levels were then determined by ELISA (G). Results are representative of two independent experiments. Error bars represent SE. n = 6–8. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle.

FIGURE 6.

Administration of CASIN after immunization has no effect on allergic airway inflammation. (A) WT mice were immunized i.p. with OVA on day 0 and day 7. On day 14 and 15, mice were challenged with aerosolized OVA or PBS. CASIN (30 mg/kg) or vehicle was injected i.p. at day 13, 14, and 15. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after the last challenge. (B-D) Total BAL cells and differential cell counts (B), representative Kwik-Diff staining for BAL cytospins (C), H&E staining of lung tissue sections (D), and cytokine levels in BAL fluids (E) are shown. Error bars represent SE. n = 6–8.

3.6. Pharmacological targeting Cdc42 has no effect on established allergic airway inflammation

We then investigated whether CASIN could ameliorate established allergic airway inflammation. WT mice were immunized and challenged with OVA to induce allergic airway inflammation. Thirty-one days after the last OVA challenge, the mice were re-challenged with OVA and treated with CASIN amid OVA re-challenge (Figure 7A).33 We found that CASIN- and vehicle-treated mice had comparable BAL cells (Figure 7B and C), inflammatory cell contents in the lungs (Figure 7D), and Th2 cytokines and Eotaxin in BAL fluids (Figure 7E). These data suggest that CASIN is not a therapeutic agent for allergic airway inflammation/asthma.

FIGURE 7.

CASIN does not inhibit recurring allergic airway inflammation. WT mice were immunized i.p. with OVA and then challenged with aerosolized OVA for 2 days to establish allergic airway inflammation. After resting 28 days, the mice were injected i.p. with CASIN or vehicle for 5 days and re-challenged with aerosolized OVA or PBS for 2 days starting 3 days after the first CASIN or vehicle treatment (A). Total BAL cells and differential cell counts (B), representative Kwik-Diff staining for BAL cytospins (C), H&E staining of lung tissue sections (D), cytokine and eotaxin levels in BAL fluids (E) are shown. Error bars represent SE. n = 4–6.

3.7. The effect of pharmacological targeting Cdc42 on prevention of allergic airway inflammation development is on-target effect

Next we examined whether the preventive effect of CASIN on allergic airway inflammation that we observed in Figure 5 was on-target effect. To this end, WT mice were immunized with OVA and challenged with OVA or PBS without CASIN treatment, whereas Cdc42−/− mice were treated with CASIN or vehicle throughout OVA immunization and challenge (Figure 8A). We found that while Cdc42−/− mice showed a reduction in OVA challenge-induced BAL cells (Figure 8B, C), inflammatory cell infiltration into the lungs (Figure 8D), and Th2 cytokines and Eotaxin in BAL fluids (Figure 8E), as seen in Fig. 3, CASIN treatment didn’t cause additive inhibition of allergic airway inflammation (Figure 8B–E). Thus, CASIN prevents allergic airway inflammation development through its inhibition of Cdc42 activity in Th2 cells.

FIGURE 8.

CASIN in vivo treatment does not have off-target effect on allergic airway inflammation. WT and Cdc42−/− mice were immunized and challenged with OVA or PBS and injected i.p. daily with CASIN or vehicle (A). Total BAL cells and differential cell counts (B), representative Kwik-Diff staining for BAL cytospins (C), H&E staining of lung tissue sections (D), Th2 cytokine and eotaxin levels in BAL fluids (E) are shown. Error bars represent SE. n = 3–5. *P < 0.05. NS: no significance.

3.8. Pharmacological targeting Cdc42 prevents house dust mite (HDM)-induced allergic airway inflammation

Finally, to substantiate our observation of preventive effect of pharmacological targeting Cdc42 on allergic airway inflammation in acute OVA-induced mouse model of asthma, we examined whether CASIN could prevent allergy airway inflammation, mucus production, and airway resistance/airway hyperresponsiveness in chronic HDM-induced mouse model of asthma (Figure 9A). We found that upon HDM induction, CASIN treatment reduced total BAL cells (Figure 9B) and decreased eosinophils and macrophages in BAL fluids (Figure 9C and D) and the lungs (Figure 9E). In line with this, inflammatory mediators including Th2 cytokines IL-4/IL-5/IL-13, Th17 cytokine IL-17, Eotaxin, and MUC-5AC in BAL fluids and/or the lungs were suppressed by CASIN (Figure 9F and G). Furthermore, CASIN inhibited HDM-specific IgE (Figure 9H) and mucus production that was revealed by PAS staining (Figure 9I and J). However, CASIN did not alter airway resistance to methacholine (Figure S10). Together, these findings suggest that CASIN prevents chronic allergic airway inflammation.

FIGURE 9.

CASIN inhibits HDM-induced allergic airway inflammation. WT mice were inoculated intratracheally (i.t.) with HDM to induce chronic allergic airway inflammation (A). Control groups were inoculated i.t. with PBS alone. Mice were sacrificed 24 h after the last challenge. (B, C) Quantification of total BAL cells (B), eosinophils (Eo), macrophages (Mϕ), neutrophils (Neu), and lymphocytes (Lym) (C) in BAL fluids. (D, E) Representative Kwik-Diff staining of BAL cytospins (D) and H&E staining of lung tissue sections (E). (F) Cytokine/chemokine levels in BAL fluids determined by ELISA. (G) mRNA levels of cytokines and chemokines in lung tissues determined by real-time PCR. Data are normalized to an 18S reference and expressed as arbitrary units. (H) HDM-specific IgE levels in the serum of mice inoculated with HDM. (I, J) Percentages of PAS-stained bronchi (I) and representative PAS staining of lung tissue sections (J). Error bars represent SE. n = 4–6. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. vehicle.

4. DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that thymic deletion of Cdc42 beginning at an early stage of thymocyte development by LCKCre impaired thymocyte development, peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell homeostasis, and iTreg differentiation but enhanced CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation and Th1/Th17 cell differentiation with no effect on Th2 cell.17–19 In this study, we show that post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 by dLCKiCre had no effect on thymocyte development, CD4+ T cell homeostasis, CD8+ T cell activation, and Th1/Th17/iTreg differentiation, whereas it dampened CD8+ T cell homeostasis, CD4+ T cell activation, and Th2 cell differentiation. Because post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 had no effect on thymocyte development and CD4+ T cell homeostasis, ruling out confounding effects of thymic output on T cell homeostasis and of CD4+ T cell homeostasis on CD4+ T cell activation, the defects in CD8+ T cell homeostasis and CD4+ T cell activation suggest that Cdc42 has an intrinsic role in maintaining CD8+ T cell homeostasis and in promoting CD4+ T cell activation. Furthermore, although post-thymic Cdc42 deletion inhibited CD4+ T cell activation, it had no effect on Th1/Th17/iTreg differentiation. The defect in Th2 cell differentiation thus suggests that Cdc42 promotes Th2 differentiation in a Th2 cell-autonomous manner. In this context, the loss of peripheral CD4+ T cells upon thymic deletion of Cdc42 might be attributed to the impaired thymocyte development. The enhanced CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation might reflect lymphopenia-induced homeostatic activation. However, we don’t think that the enhanced Th1/Th17 and weakened iTreg cell differentiation are attributed to the enhanced CD4+ T cell activation, because thymic deletion of Cdc42 had no effect on Th2 cell differentiation. Thus, it is likely that Cdc42 prevents Th1/Th17 and promotes iTreg differentiation in a cell-autonomous manner. Therefore, both Cdc42flox/floxdLCKiCre and Cdc42flox/floxLCKCre mice are valuable for assessing the intrinsic role of Cdc42 in different facets of T cell biology.

Our transcriptome analysis found that Cdc42-deficient Th2 cells had increased mRNA expression of STAT4, indicative of Th1 reprogramming,1 and of Foxp3, indicative of Treg reprogramming.3, 11 However, we did not detect alterations in protein expression of Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and Foxp3 in Cdc42-deficient Th2 cells (Figure S6D and E), suggesting that the increased mRNA expression of STAT4 and Foxp3 are compensatory effects of the impairment of Th2 differentiation program that is known to negatively regulate differentiation program of other T cell lineages.1 Moreover, we found that Cdc42-deficient Th2 had enhanced 4–1BB signaling and nucleic acid metabolism signaling, suggesting that suppression of the two signaling pathways are important for Cdc42 to promote Th2 cell differentiation. Particularly, as study of genetic deletion of TRAF1 of 4–1BB signaling pathway has suggested that TRAF1 negatively regulates Th2 cell differentiation,34 it is likely that the increased TRAF1 in Cdc42-deficient Th2 cells contributes to the impaired differentiation and thus Cdc42 promotes Th2 differentiation through repression of TRAF1 expression.

Consistent with its inhibitory effect on Th2 cell differentiation, post-thymic Cdc42 deletion alleviated allergic airway inflammation. These findings suggest that pharmacological targeting Cdc42 could be beneficial for asthma treatment. However, we found that while Cdc42 inhibitor CASIN suppressed the development of allergic airway inflammation, it had no effect on established allergic airway inflammation. Thus, it appears that pharmacological targeting Cdc42 may serve as a preventive but not therapeutic approach for asthma control. Given that there are no means to prevent asthma development, CASIN may have important clinical implications in asthma prevention. This is strongly supported by the preventive effect of CASIN on chronic allergic airway inflammation induced by human allergen HDM. To our surprise, CASIN did not affect HDM-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. We reason that inhibition of Cdc42 by CASIN may have led to a compensatory activation of RhoA signaling of Rho family GTPases that is known to regulate airway resistance.35–37

Furthermore, given that 10 μM of CASIN only affected Th2 cell differentiation without affecting Th1, Th17 and iTreg cells in vitro, 30 mg/kg of CASIN did not affect thymocyte development and peripheral T cell homeostasis in mice, and that 30 mg/kg of CASIN did not inhibit Th1/Th17 cell differentiation in vivo and inflammatory cell infiltration into the lungs and cause off-target effect in its inhibition of allergic airway inflammation, pharmacological targeting Cdc42 is likely a viable approach in preventing asthma development. However, unlike post-thymic deletion of Cdc42 that selectively affects Th2 cells in allergic airway inflammation, CASIN could potentially affect other inflammatory cells such as eosinophils and mast cells as well as non-inflammatory, asthma-mediating lung epithelial cells and smooth muscle cells. In addition, CASIN may affect cells that are not involved in asthma pathobiology. Thus, detailed toxicity/pharmacokinetic studies of CASIN are warranted in our future studies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Sources of funding: This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM108661 and R21 CA198358 to F.G.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (81373116 to J.Q.Y), and the Jiangsu Provincial Project of Invigorating Health Care through Science, Technology and Education, China (to J.Q.Y).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhu J, Yamane H, Paul WE. Differentiation of effector CD4 T cell populations. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010; 28:445–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo F, Cancelas JA, Hildeman D, Williams DA, Zheng Y. Rac GTPase isoforms Rac1 and Rac2 play a redundant and crucial role in T-cell development. Blood. 2008; 112:1767–1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dang EV, Barbi J, Yang HY, et al. Control of T(H)17/T(reg) balance by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Cell. 2011; 146: 772–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosmann TR, Coffman RL. TH1 and TH2 cells: different patterns of lymphokine secretion lead to different functional properties. Annu Rev Immunol. 1989; 7:145–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reiner SL. Development in motion: helper T cells at work. Cell. 2007; 129:33–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009; 27:485–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouyang W, Kolls JK, Zheng Y. The biological functions of T helper 17 cell effector cytokines in inflammation. Immunity. 2008; 28:454–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson DS, Hamid Q, Ying S, et al. Predominant TH2-like bronchoalveolar T-lymphocyte population in atopic asthma. N Engl J Med. 1992; 326:298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holgate ST. Innate and adaptive immune responses in asthma. Nat Med. 2012; 18:673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haspeslagh E, Debeuf N, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Murine models of allergic asthma. Methods Mol Biol. 2017; 1559:121–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ohkura N, Kitagawa Y, Sakaguchi S. Development and maintenance of regulatory T cells. Immunity. 2013; 38: 414–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulloy JC, Cancelas JA, Filippi MD, et al. Rho GTPases in hematopoiesis and hemopathies. Blood. 2010; 115:936–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stengel K, Zheng Y. Cdc42 in oncogenic transformation, invasion, and tumorigenesis. Cell Signal. 2011; 23:1415–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou X, Florian MC, Arumugam P, et al. RhoA GTPase controls cytokinesis and programmed necrosis of hematopoietic progenitors. J Exp Med. 2013; 210:2371–2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loirand G Rho Kinases in Health and Disease: From basic science to translational research. Pharmacol Rev. 2015; 67:1074–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li H, Peyrollier K, Kilic G, Brakebusch C. Rho GTPases and cancer. Biofactors. 2014; 40:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo F, Hildeman D, Tripathi P, et al. Coordination of IL-7 receptor and T-cell receptor signaling by cell-division cycle 42 in T-cell homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010; 107:18505–18510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo F, Zhang S, Tripathi P, et al. Distinct roles of Cdc42 in thymopoiesis and effector and memory T cell differentiation. PLoS One. 2011; 6:e18002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalim KW, Yang JQ, Li Y, et al. Reciprocal regulation of glycolysis-driven Th17 pathogenicity and Treg stability by Cdc42. J Immunol. 2018; 200:2313–2326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Florian MC, Dörr K, Niebel A, et al. Cdc42 activity regulates hematopoietic stem cell aging and rejuvenation. Cell Stem Cell. 2012; 10:520–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang L, Wang L, Zheng Y. Gene targeting of Cdc42 and Cdc42GAP affirms the critical involvement of Cdc42 in filopodia induction, directed migration, and proliferation in primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell. 2006; 17:4675–4685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang DJ, Wang Q, Wei J, et al. Selective expression of the Cre recombinase in late-stage thymocytes using the distal promoter of the Lck gene. J Immunol. 2005; 174:6725–6731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang JQ, Leitges M, Duran A, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. Loss of PKC lambda/iota impairs Th2 establishment and allergic airway inflammation in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009; 106:1099–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang JQ, Liu H, Diaz-Meco MT, Moscat J. NBR1 is a new PB1 signalling adapter in Th2 differentiation and allergic airway inflammation in vivo. Embo J. 2010; 29:3421–3433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang JQ, Kalim KW, Li Y, et al. RhoA orchestrates glycolysis for TH2 cell differentiation and allergic airway inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016; 137:231–245 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu S, Fan X, Yang Y, Dong P, Zhou W, Xu Y, et al. Schistosoma japonicum infection downregulates house dust mite-induced allergic airway inflammation in mice. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0179565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y, Dong P, Zhao J, Zhou W, Zhou Y, Xu Y, et al. PKClambda/iota regulates Th17 differentiation and house dust mite-induced allergic airway inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta 2018; 1864:934–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andre-Gregoire G, Dilasser F, Chesne J, Braza F, Magnan A, Loirand G, et al. Targeting of Rac1 prevents bronchoconstriction and airway hyperresponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vroman H, Bergen IM, van Hulst JAC, van Nimwegen M, van Uden D, Schuijs MJ, et al. TNF-alpha-induced protein 3 levels in lung dendritic cells instruct TH2 or TH17 cell differentiation in eosinophilic or neutrophilic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141:1620–33 e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin P, Villares R, Rodriguez-Mascarenhas S, et al. Control of T helper 2 cell function and allergic airway inflammation by PKC{zeta}. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005; 102:9866–9871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conroy DM, Williams TJ. Eotaxin and the attraction of eosinophils to the asthmatic lung. Respir Res. 2001; 2:150–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busse PJ, Zhang TF, Srivastava K, et al. Chronic exposure to TNF-alpha increases airway mucus gene expression in vivo. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005; 116:1256–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mushaben EM, Brandt EB, Hershey GK, Le Cras TD. Differential effects of rapamycin and dexamethasone in mouse models of established allergic asthma. PLoS One. 2013; 8(1):e54426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bryce PJ, Oyoshi MK, Kawamoto S, Oettgen HC, Tsitsikov EN. TRAF1 regulates Th2 differentiation, allergic inflammation and nuclear localization of the Th2 transcription factor, NIP45. Int Immunol. 2006; 18(1):101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kudo M, Melton AC, Chen C, Engler MB, Huang KE, Ren X, Wang Y, Bernstein X, Li JT, Atabai K, Huang X, Sheppard D. IL-17A produced by αβ T cells drives airway hyper-responsiveness in mice and enhances mouse and human airway smooth muscle contraction. Nat Med. 2012;18(4):547–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimoto K, Peebles RS Jr, Sheller JR, Jarzecka K, Furlong J, Mitchell DB, Hartert TV, Graham BS. Suppression of airway hyperresponsiveness induced by ovalbumin sensitization and RSV infection with Y-27632, a Rho kinase inhibitor. Thorax. 2002;57(6):524–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taki F, Kume H, Kobayashi T, Ohta H, Aratake H, Shimokata K. Effects of Rho-kinase inactivation on eosinophilia and hyper-reactivity in murine airways by allergen challenges. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(4):599–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandt EB, Kovacic MB, Lee GB, Gibson AM, Acciani TH, Le Cras TD, et al. Diesel exhaust particle induction of IL-17A contributes to severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013; 132:1194–1204 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.