Abstract

BACKGROUND.

While interest in droplet-digital PCR technology (ddPCR) for circulating-DNA (cfDNA) analysis is burgeoning, the technology is compromised by sub-sampling errors and the few clinical targets that can be analyzed from limited input DNA. The paucity of starting material acts as a ‘glass ceiling’ in liquid biopsies since, irrespective how sensitive ddPCR techniques are, detection limits cannot be improved past DNA input limitations.

Here we show that complete sample denaturation prior to ddPCR approximately doubles the data obtained from a given amount of input DNA.

METHODS.

We apply denaturation-enhanced ddPCR (dddPCR) using fragmented genomic DNA (gDNA) with defined mutations. We then test dddPCR on cfDNA from volunteers and cancer patients for commonly-used mutations. Genomic-DNA (gDNA) and cfDNA are tested with and without end-repair prior to denaturation and digital-PCR.

RESULTS.

We demonstrate that by applying complete denaturation of double-stranded DNA prior to ddPCR droplet-formation the number of positive droplets increase. dddPCR using gDNA results to 1.9–2-fold-increase in data-positive droplets, while dddPCR applied on highly-fragmented circulating-DNA results to 1.6–1.7-fold increase. Moreover, end-repair of circulating-DNA before denaturation enables circulating-DNA to display 1.9–2-fold increase in data-positive signals, like gDNA. These data indicate that doubling of data-positive droplets doubles the number of potential ddPCR assays that can be conducted from a given DNA input and improves ddPCR precision for cfDNA mutation-detection.

CONCLUSION.

Denaturation-enhanced digital-PCR is a simple and useful modification in ddPCR that enables extraction of more information from low-input clinical samples with minor change in protocols. It should be applicable to all ddPCR platforms for mutation detection and, potentially, for gene copy-number analysis in cancer and prenatal-screening.

Keywords: digital PCR, DNA mutation detection, circulating-DNA, liquid biopsy

INTRODUCTION

In the era of personalized medicine, molecular analysis of small input clinical samples such as liquid biopsy-obtained circulating DNA are of great interest due to their broad potential as clinically significant biomarkers of disease. While real time PCR (1–6), mutation/methylation enrichment (7–16) and sequencing technologies (17–20) are widely used for detecting DNA alterations in liquid biopsies, interest in digital PCR (21) is rising rapidly in view of robust quantitative aspects of the technology and the emergence of commercial droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) platforms (11, 22–25). ddPCR has been implemented in diverse fields such as cancer biomarkers (26), viral load detection, prenatal screening, organ donor rejection, or library assessment for next generation sequencing (27–29). Detection of emerging resistance or minimal residual disease via ddPCR in liquid biopsies is also growing rapidly (30).

Despite progress, ddPCR technology is restricted by the inherent problems associated with limited number of input DNA copies available for analysis (31). When just a few nanograms of circulating DNA are analyzed, the information obtained is affected by statistical sampling errors and the number of clinically relevant targets that can be analyzed is reduced. The paucity of starting material acts as a ‘glass ceiling’ in liquid biopsies since, irrespective how sensitive ddPCR techniques are, detection limits cannot be improved past the DNA input limitations. While pre-amplification of DNA can be applied to increase the material prior to ddPCR, this spoils absolute quantification and introduces a number of additional experimental problems (32).

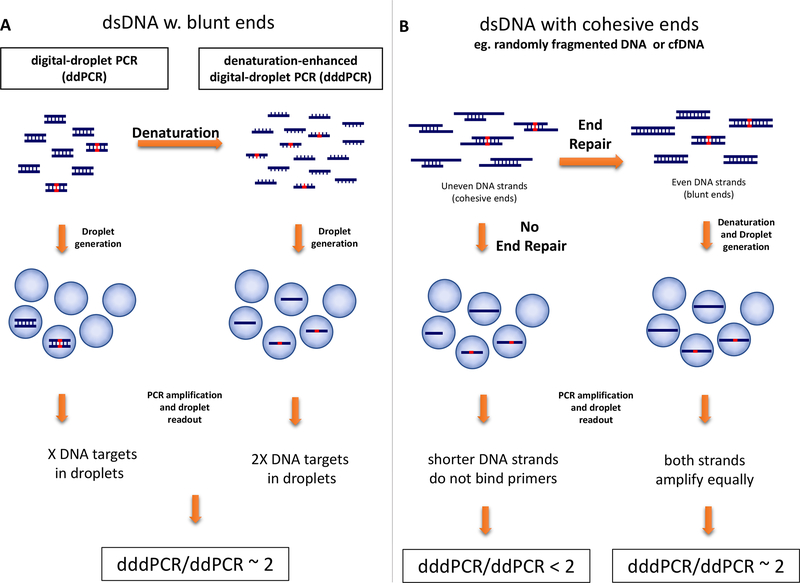

We describe a simple approach to enhance the information obtained via digital PCR technology when analyzing limited input DNA samples for mutations. As of its inception (21), digital PCR amplifies individual double stranded DNA molecules in distinct reaction compartments, then obtains signal readout from each compartment to reveal and quantify DNA targets (33). Yet the information contained in double stranded DNA is redundant, as each mutated base appears in both sense and antisense strands of the original molecule. We therefore hypothesized that by applying complete denaturation of double stranded DNA just prior to droplet formation in ddPCR would double the number of positive droplets obtained from a given DNA amount, thus enhancing ddPCR analysis of clinical samples. Indeed, amplification using just a sense or anti-sense DNA strand in a droplet is likely to produce the same number of positive droplets as the corresponding double stranded molecule, provided the two strands are of equal size to begin with (blunt-ended DNA, Figure 1A). If, on the other hand, DNA is randomly fragmented with unequal strands, as in circulating DNA, then placing each strand in a separate droplet may not double the ddPCR signal, since the shorter strand may not bind the primers. We demonstrate that a DNA end-repair step performed just prior to denaturation and droplet formation restores the ability to double the ddPCR signal, Figure 1B. This simple adaptation of digital-PCR, denaturation-enhanced droplet digital PCR (dddPCR), enables extraction of more information from small input clinical samples without substantial change in existing digital PCR protocols.

Figure 1. Concept and workflow of denaturation-enhanced digital-droplet PCR (dddPCR) as compared to standard ddPCR.

(A) dddPCR incorporates a DNA denaturation step prior to droplet generation. A mixture of fragmented gDNA, primers, hydrolysis probes and ddPCR buffer is heated to denature the template, following which ssDNA molecules are partitioned into different droplets. Compared with standard ddPCR, data-positive droplets are doubled using dddPCR. (B) Use of end-repair to blunt the DNA strands in the case of circulating DNA. The two strands become blunted, leading to doubling of the positive droplets following dddPCR. Without end-repair the ratio of dddPCR/ddPCR data-positive droplets is less than 2. End-repair and denaturation are carried out sequentially in a single tube reaction. DNA fragments with red bases represent mutated DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genomic DNA and circulating cell-free DNA samples

Genomic DNA (gDNA) from cell-line MDA-MB-435S (HTB-129D, ATCC) and the Tru-Q1 Reference Standard (HD728, Horizon Discovery) were used as mutated DNA controls for BRAF p.V600E and NRAS p.Q61K. Human male gDNA (G1471, Promega) was employed as a WT control and mixed with mutant DNA to create serially diluted samples. gDNA was digested prior to ddPCR reactions, using 10 units of HindIII-HF restriction enzyme (New England Biolabs) per 1 μg of gDNA according with manufacturer’s instructions, with 15 min incubation at 37°C.

Plasma and serum samples from cancer patients and normal volunteers were obtained from Massachusetts General Hospital, Dana Farber Cancer Institute and Brigham and Women’s Hospital under consent and Institutional Review Boards approval. Cell-free circulating DNA (cfDNA) was isolated from plasma and serum using the QIAamp MinElute Mini Kit or QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acids Kit (Qiagen), and cfDNA was quantified on a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer using a dsDNA HS assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Denaturation-enhanced digital-droplet PCR (dddPCR)

(a) dddPCR without DNA end-repair:

A QX100 Droplet Digital PCR System (Bio-Rad) was used for detection of BRAF p.V600E, BRAF p.V600K, NRAS p.Q61K and EGFR p.L858R mutations. Primers and probe sequences were previously published (12, 28, 34) and are displayed in Table 1. The amplicon sizes are 78–111bp for all assays. For each reaction, 1X ddPCR Supermix for probes (Bio-Rad) was mixed with 1 μM forward and reverse primers, 250 nM 6-FAM and HEX or VIC hydrolysis probes (IDT Technologies), and DNA template (5 to 30 ng input) to a final volume of 20 μL, as recommended by Bio-Rad. The samples containing the reaction components and DNA already mixed were placed in a Mastercycler Nexus Thermal Cycler (Eppendorf) for DNA denaturation at 95°C for 1 min. The temperature was then reduced to 37°C and the samples were loaded onto an eight-channel cartridge (Bio-Rad) along with 70 μL of droplet generation oil (Bio-Rad). Following emulsion generation on the QX100 Droplet Generator (Bio-Rad), the samples were transferred to a 96-well PCR plate, heat-sealed with foil, and amplified in a Mastercycler Nexus Thermal Cycler. The thermal cycling conditions comprised initial denaturation and polymerase activation for 10 min at 95°C, followed by 50 cycles of 94°C for 30 s and 56°C for 1 min, enzyme deactivation at 98°C for 10 min and infinite hold at 10°C. Alternatively, to decrease the chance of ssDNA damage by prolonged heating, a modified cycling protocol comprising 2 min of pre-activation at 95°C followed by 3 cycles of PCR, for generating dsDNA before proceeding to full polymerase activation at 95°C for 10 min and 50 cycles of amplification.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers and hydrolysis probes used for ddPCR and dddPCR.

| Assay/Mutation | Oligonucleotide ID | Sequence (5’−3’) | Amplicon length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF p.V600E | BRAF-15-F2 | AGACCTCACAGTAAAAATAGGT | 83 |

| BRAF-15-R2 | ACAACTGTTCAAACTGATGG | ||

| BRAF-WT | 6FAM-TCTAGCTACAGTGAAATCTCGA-BHQ1 | ||

| BRAF-V600E-Mut | HEX-TCTAGCTACAGAGAAATCTCGA-BHQ1 | ||

| BRAF p.V600K | BRAF1–15-F1 | TTTCTTCATGAAGACCTCACA | 111 |

| BRAF2-R1 | CCACAAAATGGATCCAGACAACTGT | ||

| BRAF-WT | 6FAM-TCTAGCTACAGTGAAATCTCGA-BHQ1 | ||

| BRAF-V600K-Mut | HEX-TCTAGCTACAAAGAAATCTCGAT-BHQ1 | ||

| NRAS p.Q61K | NRAS-3-F2 | GTGAAACCTGTTTGTTGGA | 79 |

| NRAS-3-R2 | GTCCTCATGTATTGGTCTCT | ||

| NRAS-WT | 6FAM-ACAGCTGGACAAGAAGAGTACA-BHQ1 | ||

| NRAS-Q61K-Mut | HEX-ACAGCTGGAAAAGAAGAGTACA-BHQ1 | ||

| EGFR p.L858R | Forward primer | GCAGCATGTCAAGATCACAGATT | 78 |

| Reverse primer | CCTCCTTCTGCATGGTATTCTTTCT | ||

| WT probe | VIC-AGTTTGGCCAGCCCAA-MGB-NFQ | ||

| MT probe | 6FAM-AGTTTGGCCCGCCCAA-MGB-NFQ |

BHQ1= Black Hole Quencher 1 ; NFQ=Nonfluorescent Quencher

Regular ddPCR was performed in parallel for each sample, using the same cycling conditions described above, but omitting DNA denaturation prior to droplet generation. The fluorescence signal for each probe was simultaneously measured by QX100 Droplet Reader (Bio-Rad) and results were analyzed with QuantaSoft™ v.1.3.2.0 software.

(b) dddPCR with DNA end-repair for circulating-DNA

In preliminary experiments, circulating cell-free DNA end-repair to produce blunt ends was performed as follows: 150 ng of cfDNA was treated with 1X NEBNext® Ultra™ II End Prep Enzyme Mix in 1X NEBNext® Ultra™ II End Prep Reaction Buffer (New England Biolabs) in a total of 60 μL reaction. Tris-HCl 10mM was added to complete the total volume and the samples were incubated at 20°C for 30 minutes and 65°C for 30 minutes as recommended by the manufacturer. The end-repaired cfDNA was purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) and then 1 to 10 ng of purified end-repaired cfDNA was used either for dddPCR or for standard ddPCR reactions as described above.

Subsequently a homogeneous, single-tube protocol was developed. 5 ng of extracted cfDNA was mixed with 10 μL of 2X ddPCR Supermix for probes (Bio-Rad) and 0.5 μL of 20X NEBNext® Ultra™ II End Prep Enzyme Mix was added in a total of 17.9 μL reaction. The mixture was incubated at 20°C for 30 minutes for end-repair and 65°C for 30 minutes for enzyme inactivation; then 1 μM forward and reverse primers and 250 nM 6-FAM and HEX or VIC hydrolysis probes (for BRAF p.V600E and EGFR p.L858R) or 1X TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assay for EGFR rs1050171 (ThermoFisher) were added, completing the final 20 μL volume. The samples were denatured at 95°C for 1 min for dddPCR denaturation, cooled down to 37°C and then proceeded to droplet generation. Thermo-cycling conditions were as described above. Experiments using cfDNA were repeated in independent days, with at least three replicas each time. dddPCR and ddPCR experiments were performed in parallel, and no-enzyme controls for cfDNA and gDNA were routinely included.

Statistical analysis

Results were reported as copies per μL of reaction, determined by the QuantaSoft™ software (Bio-Rad). Error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals using Poisson distribution. For merged wells, the outer bars represent the standard error of the mean for the replicates and the inner ones are the Poisson error bars. The relative standard error in Table 2 was calculated by dividing the square root of the concentration value by the concentration estimate. The Welch’s t-test (2-tailed, unpaired) was applied for comparison between groups of droplets. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism7.

Table 2.

Fold change of positive droplet concentration and relative standard error between samples analyzed by dddPCR and ddPCR. The concentration value (copies/μL) for each sample represents 4 merged replicates, depicted in Figure 2.

| Sample | Fold change (dddPCR/ddPCR) | Relative Standard Error, RSE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ddPCR | dddPCR | |||||

| WT | MT | WT | MT | WT | MT | |

| WT | 1.9 | N/A | 0.077 | N/A | 0.056 | N/A |

| MT 0.5% | 1.9 | 1.8 | 0.086 | 1.161 | 0.062 | 0.870 |

| MT 1% | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.082 | 0.793 | 0.059 | 0.545 |

RESULTS

dddPCR applied on genomic DNA

(a) single target analysis

In preliminary experiments, gDNA digested with a restriction enzyme, was used to analyze the effect of DNA denaturation prior to droplet formation. We employed dddPCR on 5 ng gDNA containing 5% BRAF p.V600E mutation abundance and using hydrolysis TaqMan probes that distinguish the mutation from WT DNA. Compared with standard ddPCR, no difference in the clustering pattern on the 2D-plots was observed (Supplementary figure 1A) while the number of WT and mutant positive events approximately doubled using dddPCR (Supplementary figure 1B). In control experiments, wild-type samples were also subjected to 2 or 3 consecutive rounds of the denaturation protocol, 1 min denaturation followed by cooling to 37oC, prior to droplet formation (Supplementary figure 1C). This was done to investigate whether the increase in the positive events is due in part to polymerase synthesis following partial activation of the ‘hot-start’ polymerase. If polymerase synthesis occurs following the first denaturation step, then additional rounds of denaturation prior to droplet generation would be expected to cause proportional increase in the positive events. However, the number of positive events is similar for 1–3 rounds of denaturation (Supplementary figure 1B, 1D), indicating that the doubling of data points is related to denaturation and segregation of single-stranded DNA into droplets and not to amplification prior to droplet partitioning.

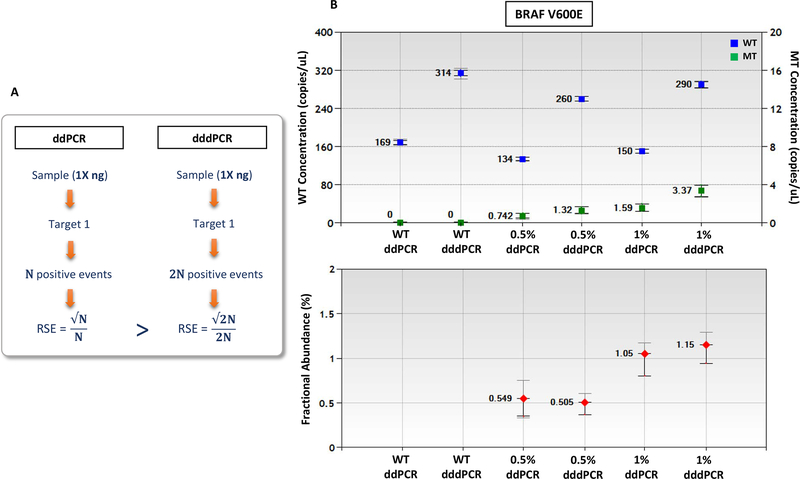

Next, dddPCR and standard ddPCR were applied to 10 ng of gDNA harboring BRAF p.V600E mutation at 1% and 0.5% allele fractions. The samples were run in quadruplicate, following the workflow depicted in Figure 2A. The number of copies per μL of reaction and the fractional abundance for the merged replicates are shown in Figure 2B, while the values for individual replicates are shown in Supplementary figure 2. The fold-change of the copies/μL, as calculated by dividing the merged copies/μL values of dddPCR by the values of ddPCR, ranged from 1.8 to 2.1-fold (Table 2), indicating that DNA was fully denatured prior to droplet formation, in the dddPCR protocol. Moreover, the calculated relative standard error (RSE) of concentration for WT and MT copies was smaller for dddPCR than for standard ddPCR (Table 2), thus improving measurement accuracy.

Figure 2. For a given DNA input, the number of positive events using dddPCR is twice that of ddPCR, thus improving the relative standard error in the analysis.

(A) Demonstration of the concept. (B) ddPCR and dddPCR for BRAF V600E using 10ng of HTB-19 cell line gDNA serially diluted into wild type DNA (WT). Outer bars represent the standard error of the mean for the replicates; the inner error bar is the 95% confidence interval for the Poisson distribution. Each sample is composed of 4 merged replicates. RSE=relative standard error.

In dddPCR DNA is denatured and ssDNA molecules are partitioned into droplets. Thus, the measured concentration reflects number of ssDNA copies. Accordingly, to quantify the original gDNA input the concentration values should be divided by 2. We compared the WT and MT copies/μL values of gDNA samples analyzed by standard ddPCR with the concentration values divided by 2 for samples analyzed by dddPCR. There was no significant difference between the two methods (P>0.05; Supplementary figure 3). Thus, if gDNA is fully denatured before droplet generation and the concentration values derived by the current commercial software are divided by 2, the absolute quantification is preserved using dddPCR.

Prolonged exposure of DNA to elevated temperatures, in TE buffer, could lead to DNA damage, introducing bias in ddPCR measurements, although damage is not significant in the commercial ddPCR mastermix (35). As a precaution we implemented a modified cycling protocol applied after droplet generation, which includes 2 min polymerase pre-activation at 95°C followed by 3 cycles of PCR to generate dsDNA before proceeding with the regular protocols of 10 min activation at 95oCand 50 cycles of PCR. This modified protocol was compared side by side with the standard cycling for both ddPCR and dddPCR and the results were found to be equivalent (Supplementary figure 4). The modified protocol was adopted for further experiments.

Next, dddPCR and ddPCR were applied to gDNA containing BRAF p.V600E mutation at 10% allelic fraction at DNA input of 10, 5, 2.5 and 1.25 ng. The fold-change in concentration (copies/μL) as obtained by dividing dddPCR values by ddPCR values was not significantly different across various gDNA input amounts (Supplementary figure 5A, 5B), indicating that dddPCR can be applied with variable input DNA quantities.

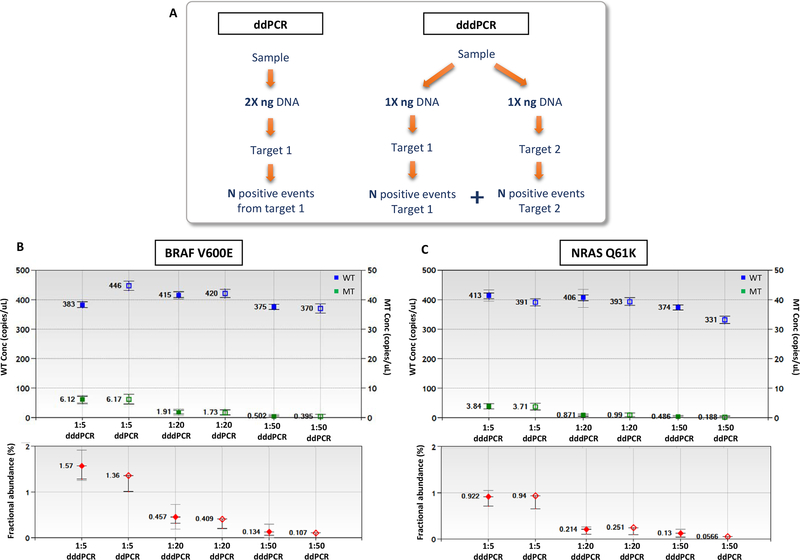

(b) Analysis of two targets with half the initial input each

Since dddPCR can double the number of positive events for a gDNA sample when compared to ddPCR, it should be possible to split the original sample in two reactions; thereby analyzing two different targets independently, each target resulting in similar number of positive droplets as a ddPCR applied on the entire sample (Figure 3A). To test this assumption, we used HD728 gDNA reference mutation standard which contains BRAF p.V600E (8% allelic frequency) and NRAS p.Q61K (5% allelic frequency) and serially diluted this 1:5, 1:20 and 1:50-fold into WT gDNA. 15 ng DNA was used for dddPCR and 30 ng DNA for standard ddPCR. The number of positive events and the concentration of WT and MT copies obtained were similar for both dddPCR and ddPCR (Figure 3B). Further, the resulting fractional mutation abundance was similar between protocols for all dilutions tested. While caution would be required when splitting samples that contain just 1–2 copies of mutated alleles, the data indicate that in general, samples can be interrogated for 2 mutations by dddPCR using the same quantity of DNA needed for analysis of only one mutation by standard ddPCR. Therefore, the number of potential assays is doubled by replacing ddPCR with dddPCR.

Figure 3. dddPCR allows the analysis of 2 different targets in independent reactions using the same quantity of DNA used for a single ddPCR reaction and producing similar number of WT and MT copies in each reaction.

(A) demonstration of the concept. (B) and (C) Analysis of gDNA HD728 serially diluted in WT DNA using 30ng (ddPCR, non-denatured), or split in two 15ng samples (dddPCR, denatured) as DNA input: BRAF V600E and NRAS Q61K screened, respectively. Undiluted gDNA HD728 contains BRAF V600E and NRAS Q61K mutations at 8% and 5% allelic frequencies, respectively. Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval for the Poisson distribution. The dddPCR results represent merged wells for 2 replicates. The concentration of WT and MT copies obtained were similar for both dddPCR and ddPCR (for WT, P = 0.49, 0.71 and 0.69 for 1:5, 1:20 and 1:50 dilutions, respectively. For MT, P = is 0.79, 0.34 and 0.19, respectively. The differences are not significant).

dddPCR applied on cfDNA from clinical samples

cfDNA samples from cancer patients previously screened for mutations were comparatively analyzed by dddPCR and ddPCR. Samples 13-post and 148-post represent plasma collected from two cancer patients post treatment, and harbor BRAF p.V600K and p.V600E, respectively. Samples SCR, C8 and C11 represent plasma collected at three different chemotherapy treatment cycles from a single patient, harbor EGFR p.L858R and have relatively low amount of cfDNA collected from plasma. WT cfDNA samples obtained from healthy donors were run in parallel as controls for all assays. The results are summarized in Supplementary figure 6 and Supplementary table 1.

The data indicate that, for two out of five cfDNA samples tested, there is increased confidence in calling a mutation when dddPCR is applied instead of standard ddPCR. For example, the 95% confidence limits for sample 13-post do not overlap with the WT control limits, when analyzed via dddPCR (Supplementary table 1 and Supplementary figure 6A). In contrast, there is overlap in confidence limits using standard ddPCR. Similar results are also shown for sample 148-post (Supplementary table 1 and Supplementary figure 6B). These data demonstrate the higher discriminatory power of using dddPCR over ddPCR.

Across all cfDNA clinical samples tested, an increased number of positive droplets was obtained when applying dddPCR as opposed to ddPCR on cfDNA. However, the ratio of dddPCR/ddPCR copies/μl was in the range 1.5–1.8 rather than 1.9–2.0 observed for gDNA. In view of this, an additional step was developed to increase further the positive events obtained with dddPCR for cfDNA (see below).

dddPCR applied to end-repaired cfDNA

We hypothesized that when randomly fragmented, small size DNA (e.g. cfDNA) is denatured and partitioned in droplets, some ssDNA copies can bind the PCR primers while others don’t due to their size. Consequently, dddPCR does not result in doubling of positive droplets when compared to ddPCR. To enable application of dddPCR on randomly fragmented cfDNA while retaining a ratio of 1.9–2, like that obtained with large-fragment gDNA or blunt ended DNA, we added an end-repair step prior to denaturation.

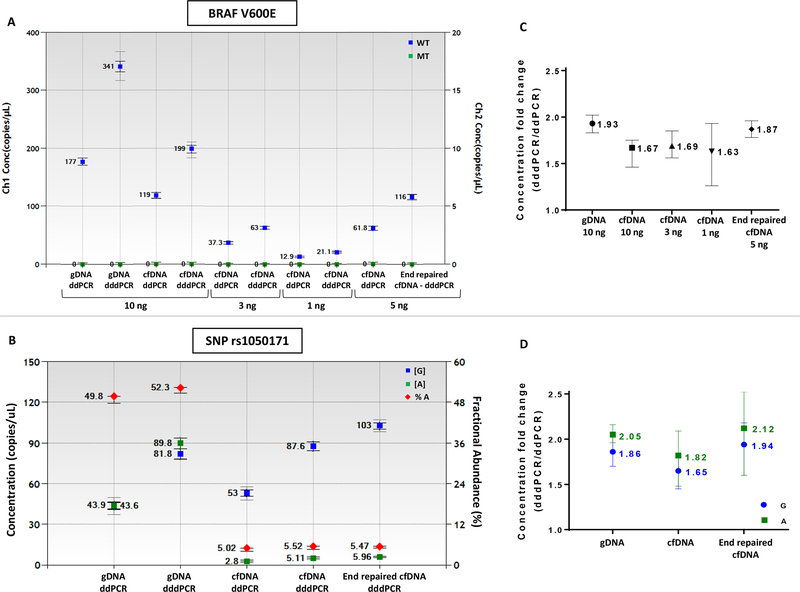

dddPCR using the current protocol was first applied multiple times on WT cfDNA obtained from normal volunteers to obtain a dddPCR/ddPCR ratio baseline for non-repaired cfDNA. BRAF p.V600E dddPCR assay was applied to 10, 3 and 1 ng WT cell-free DNA and the concentration of copy numbers was compared to standard ddPCR (Figure 4A). The ratio dddPCR/ddPCR copies/μl was on average 1.65 irrespective of the initial input, lower than 1.9–2.0 observed for gDNA (Figure 4B). We also applied ddPCR and dddPCR protocols for additional ddPCR assays, designed to interrogate mutations BRAF p.V600K, EGFR p.L858R, and EGFR polymorphism rs1050171, that employ amplicons 78–111bp and similar results were obtained (data not shown). Overall, in the absence of end-repair the ratio of dddPCR to ddPCR for cfDNA is about 1.65 for amplicon sizes of 78–111bp long that are used frequently.

Figure 4. dddPCR applied to randomly fragmented cfDNA and end-repaired cfDNA.

(A) Comparison between number of copies per μL of reaction obtained by ddPCR and dddPCR using a BRAF V600E assay. Different input of WT cfDNA and 5ng input of end-repaired cfDNA were analyzed along with WT gDNA as control. (B) SNP rs1050171 assay was used to perform end-repair followed by dddPCR, using cfDNA with 5% of allele A. The blue symbols represent copies with nucleotide G; green symbols are copies with nucleotide A; red symbols represent fractional abundance of allele A. (C, D) The concentration fold-change was calculated by dividing dddPCR by ddPCR values. End-repair and dddPCR were performed sequentially in a single tube reaction. The error bars represent the range of fold change among replicas.

Next, we performed end-repair on WT cfDNA samples just prior to denaturation and droplet formation. Initially cfDNA was blunted with end-repair enzyme in the manufacturer supplied buffer. The blunted cfDNA was then purified and analyzed via ddPCR or dddPCR in parallel, using two different assays, BRAF p.V600E and EGFR p.L858R (Supplementary figure 7A, 7B). For both assays, the concentration fold-change for end-repaired cfDNA was higher than for not repaired cfDNA and like gDNA, ~1.9–2 (Supplementary figure 7C).

Subsequently a single-tube, homogeneous protocol for end-repair and dddPCR was developed (see Materials), by adding the end-repair enzyme directly into the ddPCR buffer. The single-tube end-repair dddPCR protocol was applied to 5 ng cfDNA using two different assays, BRAF p.V600E and EGFR SNP rs1050171. The concentration fold-change was obtained by dividing the end-repair dddPCR values by standard ddPCR values (Figure 4). The BRAF assay was tested using WT cfDNA, resulting in increased fold change for blunted cfDNA of 1.9–2, like gDNA (Figure 4A, 4C). A SNP rs1050171 assay was then used to test the end-repair dddPCR protocol on cfDNA. A cfDNA sample with 5% minority allele was prepared and the concentration fold change was compared for repaired vs. non-repaired cfDNA. gDNA (G1471), heterozygous for the same G/A polymorphism, was analyzed in parallel (Figure 4B, 4D). Similar fold-changes were observed for the 5% variant (allele A) and the 95% variant (allele G), for each condition. The data indicate that, by applying end-repair to cfDNA, the ratio of dddPCR to ddPCR is restored to 1.9–2.0, equal to that obtained for large fragments of gDNA or blunt DNA.

DISCUSSION

The limited amount of DNA obtained from liquid biopsies restricts the number of targets that can be examined via ddPCR or real time PCR and reduces the ability to identify rare mutations (25, 36). It is possible to apply a DNA pre-amplification step prior to mutation detection and ddPCR to increase the material available (29, 32). However, pre-amplification eliminates one of the main advantages of digital PCR, the absolute quantification of DNA copies, while the possibility for polymerase-introduced errors increases. Further, pre-amplification may introduce measurement bias and decrease the precision of digital PCR (32) and entails an extra step that increases cost, complexity and the risk for cross-contamination.

Applying complete denaturation just before droplet formation, as proposed in this work, entails minimal change to the established protocols and doubles the number of positive droplets without reducing the advantages of digital PCR. The benefit of this approach is to enable interrogation and precise quantification of lower percentage mutants than possible using standard ddPCR approaches with limited mass material. Another benefit comprises the ability to split the sample and perform two digital PCR reactions examining different targets, while retaining the same number of droplets in each reaction. Increasing the targets that can be examined in ddPCR may also be achieved via amplitude multiplexing (32). However, dddPCR is relatively simple, and no major modification of existing procedures are required, providing an almost “no cost” approach to double the input DNA available for analysis. Unlike multiplexed ddPCR, in dddPCR there is no need for equipment with multiple optical channels, software for analysis of complex data or extensive optimization. Moreover, dddPCR can be combined with existing multiplexing methods, thus enabling a single duplex ddPCR reaction to become two duplex dddPCR reactions, and so forth.

For cfDNA an additional end-repair step is applied to equalize sense and anti-sense strands and retain the approximate doubling of positive events following denaturation. This single-tube process entails direct addition of repair enzymes into the ddPCR mastermix. While end-repair performed in the same tube is a minor change to the overall protocol and is likely to result to better quantification, it is also possible to simply omit repair and apply a 1.6–1.7-fold increase in the number of positive droplets, as opposed to 1.9–2-fold obtained after repair, for cfDNA and amplicons between 70–110bp long. Thus, for absolute quantification purposes a correction of 1.65-fold in the measured copy number concentration could be applied without cfDNA repair while a 1.95-fold can be applied with repair or whenever PCR amplicons are substantially smaller than the interrogated DNA fragments. Due to the proof-of-principle nature of this investigation, these values should be regarded as preliminary and additional studies must be conducted to finalize the corrections for optimal quantification.

Partial denaturation prior to droplet formation was considered to be a potential problem in ddPCR, as it might affect quantification (27), while DNA damage in long templates may reduce the obtained number of positive events (35, 37). As Figures 1–4 demonstrate these concerns are overcome using the current cycling protocol that enables complete denaturation and short (<110bp) amplicons, while restricting excessive heating at 95oC.

While here we focus on droplet-based digital PCR, the same approach should be applicable to other digital PCR platforms. Further, while emphasis in this work is on mutations, doubling the number of positive droplets in digital PCR may be equally beneficial for copy number and gene amplification analysis via digital PCR (38), as increasing the number of events decreases the overall measurement uncertainty. In addition to applications in cancer, dddPCR application in prenatal diagnosis or in organ transplantation can also be envisioned.

In summary, we developed a process for approximately doubling the number of positive events during droplet digital PCR by partitioning denatured, single DNA strands in droplets, and by applying end-repair prior to denaturation for the specific case of randomly fragmented DNA (cfDNA). This simple and useful modification doubles the potential number of assays from a given amount of input DNA and improves the confidence limits in digital PCR-based mutation detection. The process entails minor departure from established digital-PCR protocols and enables extraction of more information from precious clinical samples and liquid biopsies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants R33 CA217652 and R01 CA221874 to GMM. The contents of this manuscript do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tyagi S, Kramer FR. Molecular beacons: Probes that fluoresce upon hybridization. Nat Biotechnol 1996;14:303–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernard PS, Wittwer CT. Real-time pcr technology for cancer diagnostics. Clin Chem 2002;48:1178–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li J, Wang F, Mamon H, Kulke MH, Harris L, Maher E, et al. Antiprimer quenching-based real-time pcr and its application to the analysis of clinical cancer samples. Clinical Chemistry 2006;52:624–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amicarelli G, Shehi E, Makrigiorgos GM, Adlerstein D. Flag assay as a novel method for real-time signal generation during pcr: Application to detection and genotyping of kras codon 12 mutations. Nucleic acids research 2007;35:e131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Wang L, Janne PA, Makrigiorgos GM. Coamplification at lower denaturation temperature-pcr increases mutation-detection selectivity of taqman-based real-time pcr. Clin Chem 2009;55:748–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanchez JA, Pierce KE, Rice JE, Wangh LJ. Linear-after-the-exponential (late)-pcr: An advanced method of asymmetric pcr and its uses in quantitative real-time analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004;101:1933–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li J, Wang L, Mamon H, Kulke MH, Berbeco R, Makrigiorgos GM. Replacing pcr with cold-pcr enriches variant DNA sequences and redefines the sensitivity of genetic testing. Nat Med 2008;14:579–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milbury CA, Li J, Makrigiorgos GM. Ice-cold-pcr enables rapid amplification and robust enrichment for low-abundance unknown DNA mutations. Nucleic acids research 2011;39:e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.How Kit A, Mazaleyrat N, Daunay A, Nielsen HM, Terris B, Tost J. Sensitive detection of kras mutations using enhanced-ice-cold-pcr mutation enrichment and direct sequence identification. Hum Mutat 2013;34:1568–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y, Song C, Ladas I, Fitarelli-Kiehl M, Makrigiorgos GM. Methylation-sensitive enrichment of minor DNA alleles using a double-strand DNA-specific nuclease. Nucleic acids research 2017;45:e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hindson CM, Chevillet JR, Briggs HA, Gallichotte EN, Ruf IK, Hindson BJ, et al. Absolute quantification by droplet digital pcr versus analog real-time pcr. Nat Methods 2013;10:1003–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Song C, Liu Y, Fontana R, Makrigiorgos A, Mamon H, Kulke MH, Makrigiorgos GM. Elimination of unaltered DNA in mixed clinical samples via nuclease-assisted minor-allele enrichment. Nucleic acids research 2016;44:e146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ladas I, Yu F, Leong KW, Fitarelli-Kiehl M, Song C, Ashtaputre R, et al. Enhanced detection of microsatellite instability using pre-pcr elimination of wild-type DNA homo-polymers in tissue and liquid biopsies. Nucleic acids research 2018;46:e74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu LR, Chen SX, Wu Y, Patel AA, Zhang DY. Multiplexed enrichment of rare DNA variants via sequence-selective and temperature-robust amplification. Nat Biomed Eng 2017;1:714–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li J, Milbury CA, Li C, Makrigiorgos GM. Two-round coamplification at lower denaturation temperature-pcr (cold-pcr)-based sanger sequencing identifies a novel spectrum of low-level mutations in lung adenocarcinoma. Hum Mutat 2009;30:1583–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladas I, Fitarelli-Kiehl M, Song C, Adalsteinsson VA, Parsons HA, Lin NU, et al. Multiplexed elimination of wild-type DNA and high-resolution melting prior to targeted resequencing of liquid biopsies. Clin Chem 2017;63:1605–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adalsteinsson VA, Ha G, Freeman SS, Choudhury AD, Stover DG, Parsons HA, et al. Scalable whole-exome sequencing of cell-free DNA reveals high concordance with metastatic tumors. Nat Commun 2017;8:1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas RK, Nickerson E, Simons JF, Janne PA, Tengs T, Yuza Y, et al. Sensitive mutation detection in heterogeneous cancer specimens by massively parallel picoliter reactor sequencing. Nat Med 2006;12:852–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milbury CA, Correll M, Quackenbush J, Rubio R, Makrigiorgos GM. Cold-pcr enrichment of rare cancer mutations prior to targeted amplicon resequencing. Clin Chem 2012;58:580–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Narayan A, Carriero NJ, Gettinger SN, Kluytenaar J, Kozak KR, Yock TI, et al. Ultrasensitive measurement of hotspot mutations in tumor DNA in blood using error-suppressed multiplexed deep sequencing. Cancer Res 2012;72:3492–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Digital pcr. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1999;96:9236–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taly V, Pekin D, Benhaim L, Kotsopoulos SK, Le Corre D, Li X, et al. Multiplex picodroplet digital pcr to detect kras mutations in circulating DNA from the plasma of colorectal cancer patients. Clin Chem 2013;59:1722–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Day E, Dear PH, McCaughan F. Digital pcr strategies in the development and analysis of molecular biomarkers for personalized medicine. Methods 2013;59:101–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castellanos-Rizaldos E, Paweletz C, Song C, Oxnard GR, Mamon H, Janne PA, Makrigiorgos GM. Enhanced ratio of signals enables digital mutation scanning for rare allele detection. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD 2015;17:284–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huggett JF, Cowen S, Foy CA. Considerations for digital pcr as an accurate molecular diagnostic tool. Clin Chem 2015;61:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laurent-Puig P, Pekin D, Normand C, Kotsopoulos SK, Nizard P, Perez-Toralla K, et al. Clinical relevance of kras-mutated subclones detected with picodroplet digital pcr in advanced colorectal cancer treated with anti-egfr therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2015;21:1087–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huggett JF, Foy CA, Benes V, Emslie K, Garson JA, Haynes R, et al. The digital miqe guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative digital pcr experiments. Clin Chem 2013;59:892–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oxnard GR, Paweletz CP, Kuang Y, Mach SL, O’Connell A, Messineo MM, et al. Noninvasive detection of response and resistance in egfr-mutant lung cancer using quantitative next-generation genotyping of cell-free plasma DNA. Clin Cancer Res 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy DM, Bejar R, Stevenson K, Neuberg D, Shi Y, Cubrich C, et al. Nras mutations with low allele burden have independent prognostic significance for patients with lower risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia 2013;27:2077–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, Romans K, Goodman S, Li M, et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med 2008;14:985–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Postel M, Roosen A, Laurent-Puig P, Taly V, Wang-Renault SF. Droplet-based digital pcr and next generation sequencing for monitoring circulating tumor DNA: A cancer diagnostic perspective. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2018;18:7–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whale AS, Cowen S, Foy CA, Huggett JF. Methods for applying accurate digital pcr analysis on low copy DNA samples. PLoS One 2013;8:e58177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hindson BJ, Ness KD, Masquelier DA, Belgrader P, Heredia NJ, Makarewicz AJ, et al. High-throughput droplet digital pcr system for absolute quantitation of DNA copy number. Anal Chem 2011;83:8604–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herrmann MG, Durtschi JD, Bromley LK, Wittwer CT, Voelkerding KV. Amplicon DNA melting analysis for mutation scanning and genotyping: Cross-platform comparison of instruments and dyes. Clin Chem 2006;52:494–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhat S, McLaughlin JL, Emslie KR. Effect of sustained elevated temperature prior to amplification on template copy number estimation using digital polymerase chain reaction. Analyst 2011;136:724–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milbury CA, Li J, Makrigiorgos GM. Pcr-based methods for the enrichment of minority alleles and mutations. Clin Chem 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhat S, Curach N, Mostyn T, Bains GS, Griffiths KR, Emslie KR. Comparison of methods for accurate quantification of DNA mass concentration with traceability to the international system of units. Anal Chem 2010;82:7185–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gevensleben H, Garcia-Murillas I, Graeser MK, Schiavon G, Osin P, Parton M, et al. Noninvasive detection of her2 amplification with plasma DNA digital pcr. Clin Cancer Res 2013;19:3276–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.