Significance

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) are specialized enzymes that hydrolyze choline esters. BChE can inactivate the hunger hormone, ghrelin, thus implicating it in regulation of obesity and behavior. Importantly, BChE is a bioscavenger that can hydrolyze a wide range of organophosphates, thus being tested for treatment of soldiers or civilians exposed to deadly organophosphate nerve agents. HuBChE, and engineered variants, are also being studied for treatment for cocaine and heroin addictions. All these applications require use of tetrameric HuBChE, since effective treatment requires the long circulatory residence time displayed by the tetramer. Knowledge of the structure of the HuBChE tetramer, and of its sugar-coated surface, should be relevant to the development of other proteins for therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: butyrylcholinesterase, cryoelectron microscopy, acetylcholinesterase, bioscavenger, superhelical assembly

Abstract

The quaternary structures of the cholinesterases, acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), are essential for their localization and function. Of practical importance, BChE is a promising therapeutic candidate for intoxication by organophosphate nerve agents and insecticides, and for detoxification of addictive substances. Efficacy of the recombinant enzyme hinges on its having a long circulatory half-life; this, in turn, depends strongly on its ability to tetramerize. Here, we used cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) to determine the structure of the highly glycosylated native BChE tetramer purified from human plasma at 5.7 Å. Our structure reveals that the BChE tetramer is organized as a staggered dimer of dimers. Tetramerization is mediated by assembly of the C-terminal tryptophan amphiphilic tetramerization (WAT) helices from each subunit as a superhelical assembly around a central lamellipodin-derived oligopeptide with a proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD) sequence that adopts a polyproline II helical conformation and runs antiparallel. The catalytic domains within a dimer are asymmetrically linked to the WAT/PRAD. In the resulting arrangement, the tetramerization domain is largely shielded by the catalytic domains, which may contribute to the stability of the human BChE (HuBChE) tetramer. Our cryo-EM structure reveals the basis for assembly of the native tetramers and has implications for the therapeutic applications of HuBChE. This mode of tetramerization is seen only in the cholinesterases but may provide a promising template for designing other proteins with improved circulatory residence times.

The cholinesterases (ChEs) are a specialized family of enzymes that hydrolyze choline-based esters, such as the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) functions primarily to terminate transmission at cholinergic synapses by rapid hydrolysis of acetylcholine (1). Butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), its sister enzyme, is rather enigmatic. It is abundant in plasma and was initially believed to be an evolutionary vestige (2). It has been suggested that it functions primarily as a detoxification enzyme, thereby protecting AChE from inhibition (3, 4). It has recently been shown, however, that it inactivates the hunger hormone, ghrelin, thus reducing obesity, as well as aggression, in male mice (5, 6). Because of its ability to hydrolyze organophosphates (OPs), such as nerve agents and pesticides (3), and drugs such as cocaine (7, 8) and heroin (9–11), BChE is a promising therapeutic agent with multiple applications.

Both AChE and BChE exist in various oligomeric forms, including monomers, dimers, and tetramers (12). AChE tetramers are anchored at cholinergic synapses through association with either a collagen tail, in the peripheral nervous system, or a transmembrane anchor in the central nervous system (12–14). BChE exists in plasma mainly as highly glycosylated soluble tetramers (15). The use of human BChE (HuBChE) as a therapeutic agent for combating OP poisoning is contingent on its possessing a long circulatory half-life (16). Because its half-life depends on its ability to tetramerize, substantial effort has been invested in developing methods to produce recombinant tetrameric HuBChE (17–20).

Massoulié and coworkers (21–24) identified the sequences in the AChE and ColQ polypeptides and, subsequently, in PRiMA. ColQ and PRiMA are proteins that anchor the catalytic subunits of AChE to the synaptic basal lamina and to the synaptic plasma membrane in the peripheral and central nervous systems, respectively (22, 24). In the catalytic subunit, the sequence is what they called a tryptophan amphiphilic tetramerization (WAT) sequence, close to the C terminus, because it contains three highly conserved Trp residues (21). In both ColQ and PRIMA, the sequence was identified as what was denoted as a proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD) (22, 24). Synthetic oligopeptides were prepared, corresponding to the WAT and PRAD sequences in mammalian AChE and ColQ, respectively (25). When mixed in a 4:1 ratio, they produced well-diffracting crystals from which a structure was obtained in which four WATs are seen to assemble in a superhelical, or coiled-coil, structure around a central polyproline II (PPII) helix. This PPII helix, formed by the PRAD, runs antiparallel to the WAT helices (25). The WATs are tightly associated with the PRAD via both hydrophobic stacking and hydrogen bonds. On the basis of the WAT/PRAD, a model for the structure of the synaptic A12 form of AChE was proposed (25).

Mass spectrometry of HuBChE assemblies revealed the presence of proline-rich peptides that are 10–39 residues long. Of these, ∼70% are derived from lamellipodin and the remaining ∼30% from up to 20 other proteins (26). Lamellipodin is a pleckstrin homology (PH) domain-containing protein that regulates the formation of actin-based cell protrusions by interacting with Enabled/Vasodilator-stimulated protein (Ena/VASP) proteins (27, 28). Ena/VASP proteins bind their ligands through conserved proline-rich sequences, but how exactly BChE comes to be associated with lamellipodin-derived peptides remains unclear. Presumably, HuBChE is synthesized and released into the plasma as monomers, which then associate with polyproline-rich peptides to form the functional tetramer (2). Since the HuBChE polypeptide contains a WAT sequence highly homologous to that of AChE near its C terminus (25), it seemed plausible that it assembles to the native tetramer in a similar way and may thus be formally considered as a heteropentamer rather than as a homotetramer.

Numerous high-resolution structures are available for various forms of the catalytic subunit of AChE and BChE from several species (29). However, these structures do not provide any structural information concerning the mode of assembly of functional tetramers (30, 31). Here, we use cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) to determine the structure of the tetrameric form of full-length, glycosylated HuBChE. This cryo-EM structure of the HuBChE tetramer provides valuable insights into the molecular architecture of a biologically relevant ChE oligomer.

Results and Discussion

To determine the structure of native, tetrameric HuBChE, we used enzyme purified from plasma (32). HuBChE prepared in this manner is 98% tetrameric (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). A cryo-EM single-particle dataset was collected and processed as summarized in Table 1 (see Materials and Methods for details). Following 2D classification, ab initio 3D reconstruction and classification were initially performed without applying symmetry. During 3D refinement, C2 symmetry was applied, resulting in the 5.7-Å reconstruction shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Cryo-EM collection, processing, refinement, and validation statistics

| Human butyrylcholinesterase tetramer | |

| Data collection | |

| Microscope | Talos Arctica |

| Accelerating voltage, kV | 200 |

| Nominal magnification | 130,000× |

| Pixel size, Å | 1.0285 |

| Detector | Gatan K2 Summit |

| Exposure time (Frame length), s | 6.3 (0.3) |

| Total electron exposure, e−/Å2 | 49.5 |

| Total movies collected | 4,518 |

| Data processing | |

| Software used | Relion 2.1, Relion 3.0 beta, cryoSPARC v1 |

| Initial particle count | 414,189 |

| Final particle count | 111,986 |

| Symmetry | C2 |

| Map resolution, Å | 5.7 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 |

| Sharpening B factor, Å2 | −456.502 |

| Refinement and validation | |

| Software used | Phenix, Coot |

| Model composition | |

| Chains | 5 |

| Atoms | 18,174 (hydrogens: 0) |

| Amino acid residues | 2,252 |

| Water molecules | 0 |

| Ligands | NAG: 8 |

| rms deviations | |

| Bond lengths, Å | 0.007 |

| Bond angles, ° | 1.343 |

| Validation | |

| MolProbity score | 1.96 |

| Clashscore | 7.63 |

| Poor rotamers, % | 1.70 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favored, % | 94.74 |

| Allowed, % | 4.55 |

| Disallowed, % | 0.71 |

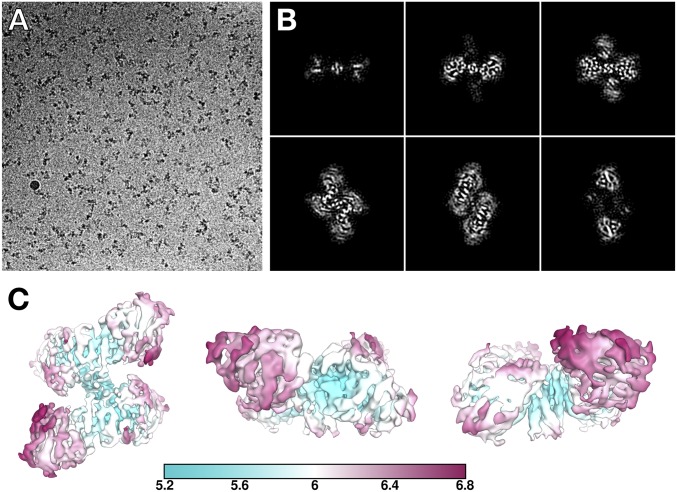

Fig. 1.

Cryoelectron microscopy reveals the organization of the HuBChE tetramer. (A) A representative micrograph from the HuBChE dataset, collected at −2.5 μm defocus and a pixel size of 1.0285 Å. (B) Slices through the 5.7-Å cryo-EM map, taken every ∼10 Å. (C) Local resolution of the HuBChE map estimated by Relion.

The cryo-EM map unambiguously shows that BChE tetramerization is mediated by a central superhelical assembly, which is largely shielded by the catalytic domains (Fig. 1 B and C). To model the structure of tetrameric HuBChE, catalytic domains taken from the crystal structure of recombinant full-length HuBChE (PDB ID code 4AQD) (33), and homology models of the WAT helices (535–565) based on the synthetic WAT/PRAD complex of AChE (PDB ID code 1VZJ) (25), were fitted as rigid bodies into the cryo-EM map (for details, see Materials and Methods). We modeled the PRAD as the core of the lamellipodin-derived polyproline sequence (PPPPPPPPPPPPP). The complete BChE model was globally real-space refined in Phenix (34, 35), with secondary structure, noncrystallographic symmetry (NCS), and torsion restraints applied (Materials and Methods), resulting in the final model shown in Fig. 2.

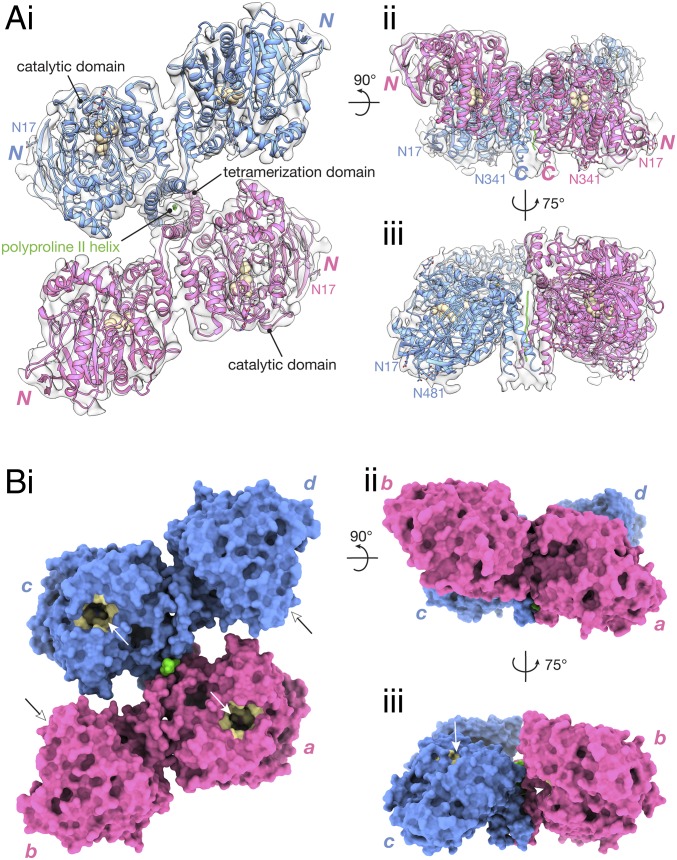

Fig. 2.

The HuBChE tetramer is a staggered dimer of dimers. The structure is presented as a ribbon model fitted into the cryo-EM map (gray) (A) and a molecular surface (B). In A, the catalytic triad (Ser198, Glu325, His438) is shown as tan spheres, disulfide bonds are highlighted in yellow, and glycans are shown as sticks. “N” and “C” denote the positions of the N and C termini of each subunit, respectively. In B, the active-site gorge is painted in tan and indicated by an arrow. Individual subunits are labeled a, b, c, and d, according to their chain IDs in the PDB deposition.

Our HuBChE model shows that BChE tetramerization is mediated by assembly of the C-terminal WAT helices into a left-handed superhelix around a central lamellipodin-derived oligopeptide that adopts the polyproline II helix conformation (Fig. 2A). Thus, the tetramerization domain of HuBChE in the context of the full tetramer assembly closely resembles that of the synthetic WAT/PRAD complex of AChE (25). The rmsd between our HuBChE WAT/PRAD and AChE WAT/PRAD (PDB ID code 1VZJ) is 1.44 Å for Cα atoms.

The HuBChE Tetramer Is a Staggered Dimer of Dimers.

The HuBChE tetramer is organized as a dimer of dimers (Fig. 2). Although each monomer was fitted as a separate rigid body, the resulting dimers are remarkably similar (rmsd for Cα atoms 0.81 Å) to the canonical dimer described by Brazzolotto et al. (ref. 33; PDB ID code 4AQD), in which individual monomers associate via a four-helix bundle like that in the dimer observed in the prototypic Torpedo californica AChE (TcAChE) crystal structure (36).

The cryo-EM map reveals that the four catalytic domains do not lie in the same plane. Instead, each dimer is tilted ∼67° relative to the vertical axis of the WAT/PRAD PPII helix (Fig. 2 A, ii and B, ii). This arrangement of the monomers results in a “double seesaw”-like appearance when the tetramer is viewed from the side. Furthermore, each dimer is shifted horizontally with respect to the other when viewed along the vertical axis of the tetramerization domain (Fig. 2 A, i and B, i). The HuBChE tetramer thus assembles as a quasi (due to the PRAD) C2-symmetric dimer of dimers in which the monomers are diagonally equivalent.

Our structure differs from previous low-resolution crystal structures obtained for tetrameric EeAChE (30, 31). These structures have rmsd values of 12.84 Å (PDB ID code 1C2B), 13.74 Å (PDB ID code 1EEA), and 21.83 Å (PDB ID code 1C2O) relative to our cryo-EM model. A computational model of HuBChE, constructed based on the 1C2O EeAChE structure and on the 1VZJ WAT/PRAD structure (37), differs significantly from the cryo-EM structure in two major aspects. In addition to being markedly nonplanar, our cryo-EM map reveals that the tetramerization domain is largely shielded by the catalytic domains. In contrast, in the computational model, it is solvent-exposed and protrudes out of the plane of the four HuBChE monomers.

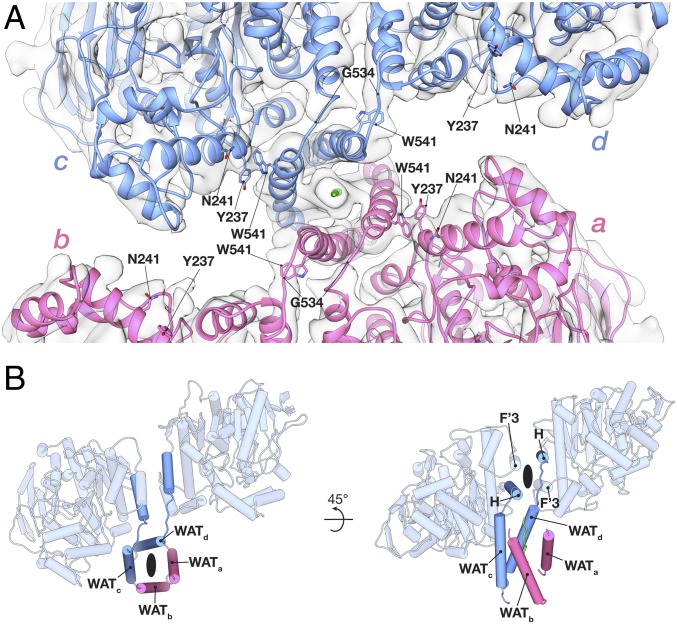

The catalytic domains within a dimer are asymmetrically linked to their respective WAT helices (Fig. 3A). The break in twofold symmetry between the monomers occurs at G534 and is imposed by the orientation of the dimer relative to the tetramerization domain. The four-helix bundle holding the dimer together is oriented ∼45° relative to the tetramerization domain’s vertical axis (Fig. 3B). Consequently, for the WAT helices to form the tetramerization domain, the linkers connecting the H helices from each monomer need to run in different directions relative to their respective catalytic domains.

Fig. 3.

Subunits within a HuBChE dimer are asymmetrically linked to the tetramerization domain. (A) Close-up top view down the tetramerization domain. (B) Individual subunits within the dimer are asymmetrically linked to the tetramerization domain.

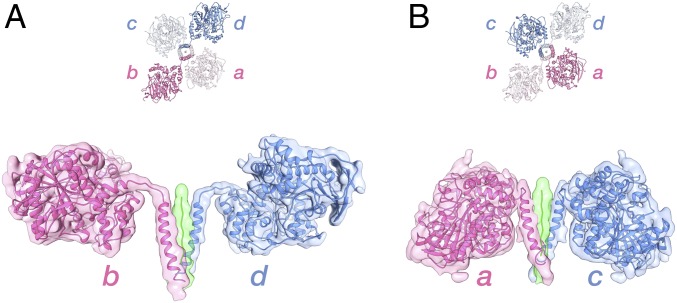

The ∼67° tilted assembly of the dimers around the tetramerization domain results in two different arrangements for the catalytic domains relative to the tetramerization domain (Fig. 4). In one diagonal pair of equivalent monomers (chains b and d), the catalytic domains are angled outward from the WAT helix and, thus, more separated from the tetramerization domain (open arrangement; Fig. 4A), while in the other diagonal pair (chains a and c), they are angled inwards, toward the WAT, and are thus relatively nearer to the tetramerization domain (closed arrangement; Fig. 4B). Some of the density for the linkers connecting the catalytic domains in the closed arrangement (chains a and c) is weaker than that seen for the open arrangement (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 4.

Two different arrangements for the catalytic domains relative to the tetramerization domain. Side views of the subunits in the “open” (chains b and d) (A) and “closed” (B) arrangements (chains a and c).

Based on local resolution estimates, the catalytic domains in the closed arrangement are slightly better resolved than the subunits in the open arrangement (Fig. 1C). In the closed arrangement, we observed a density (near Trp541) that may indicate a local interface between the catalytic domain and the tetramerization domain (Fig. 3A). Near this interface is also glycosylation site Asn241 (Fig. 3A), where we see putative glycan density. HuAChE does not have a glycosylation site at this position, but rather Arg246.

Outside the tetramerization domain, there seems to be minimal interaction between the two dimers. No surface area is buried at the dimer-dimer interface, namely between the catalytic domains of chains a and d, or of chains b and c (Fig. 2 B, i). Solvent accessibility of the dimer-dimer interface is crucial, since the entrances to two of the active-site gorges, those of subunits b and d, are at this interface (Fig. 2 B, i and iii). Indeed, the kinetic parameters of the native tetramer are similar to those reported for a low-glycosylated monomeric recombinant HuBChE (38).

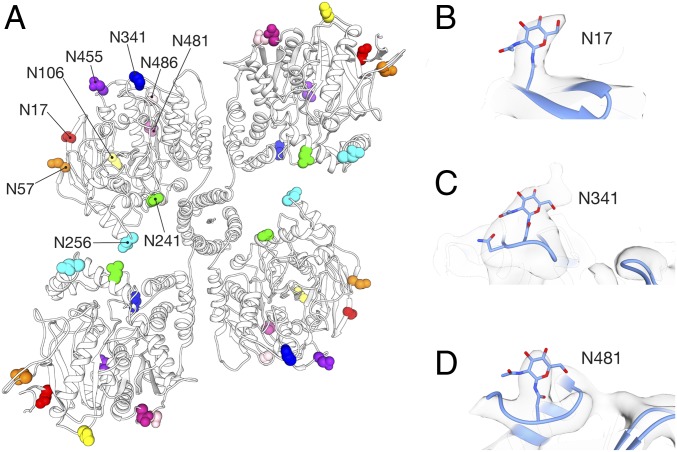

HuBChE has nine glycosylation sites, of which at least eight are occupied (39). We observe putative glycan densities at six of these sites, those at positions N17, N57, N106, N241, N341, and N486 (Fig. 5). Of particular interest is N241. Due to the horizontal shift of the dimers relative to the tetramerization domain, N241 is found at two distinct locations within the tetramer (Fig. 5A). In the open subunits N241 is located at the dimer-dimer interface, whereas in the closed subunits it is at an interface with the tetramerization domain as mentioned above. It seems that the glycan at N241 is not only crucial for stabilizing the dimer–dimer interaction, but also imposes steric constraints that ensure the solvent accessibility of the entrances to the two active-site gorges at the interface.

Fig. 5.

Putative glycan densities are visible in the cryo-EM map. Each HuBChE chain has nine N-linked glycosylation sites (42). The positions of these sites in the tetramer are shown in A. Glycans were modeled at positions N17 (B), N341 (C), and N481 (D).

Overall, due to the arrangement of the catalytic subunits around the tetramerization domain, the latter does not completely protrude out of the tetramer as had been previously suggested (37). Indeed, the fact that the tetramerization domain is mostly shielded by the catalytic domains may contribute to the HuBChE tetramer’s relative stability. Thus, thermostability measurements showed that tetrameric HuBChE is more stable than tetrameric TcAChE by ∼10 °C (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C and D). It should be noted that our model ends at residue 564, and lacks 10 C-terminal residues, which may partially protrude out.

We note that this mode of tetramer assembly has so far only been observed for ChEs, although it may provide a promising template on which to base the design of engineered proteins for which oligomerization, so as to extend their circulatory half-life, would be beneficial.

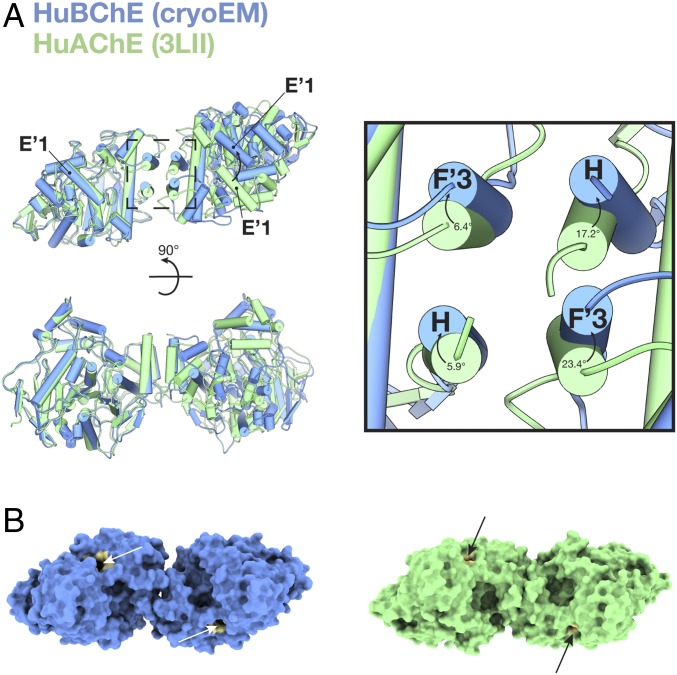

The Cryo-EM Structure Reveals Differences Between the HuBChE Dimer and the AChE Dimer.

The HuBChE dimer interface is clearly formed by a four-helix bundle comprised of helices 362–373 (helix F′3) and 516–529 (helix H) from each monomer. Alignment of the HuBChE dimer with the HuAChE dimer (PDB ID code 3LII) (29) reveals differences in the relative orientation of subunits (Fig. 6). Although one catalytic domain of HuAChE can be superimposed well on one catalytic domain of HuBChE (rmsd = 1.56 Å) (Fig. 6A, Left subunit), the second catalytic domain aligns much less well (rmsd = 8.73 Å) (Fig. 6A, Right subunit). This difference has implications for the relative orientations of the active-site gorges in the corresponding ChE dimers; the angle between the gorge entrances is smaller in the BChE dimer than in the AChE dimer (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

The cryo-EM structure reveals differences between BChE and AChE dimers. (A) Superposition of the HuBChE cryo-EM dimer (in blue) and the HuAChE crystal structure dimer (PDB ID code 3LII) (in green). Inset shows the four-helix bundle at the dimer interface. Corresponding angles between the H and F′3 helixes are marked. (B) Surface representations of the HuBChE dimer and of the HuAChE dimer. In both cases, the active-site gorge is painted tan and indicated by an arrow.

While it is possible that the differences observed between the HuBChE and HuAChE dimer structures arise simply because the structures of the AChE dimer were determined in the absence of the tetramerization domain, the structural differences between them may be functionally relevant. When AChE and BChE are coexpressed along with a PRAD peptide from PRiMA, AChE and BChE homotetramers are formed, along with “hybrid” tetramers that consist of one AChE homodimer and one BChE homodimer (40). Although mammalian AChE can form heterodimers with avian AChE, mammalian AChE does not seem to be able to heterodimerize with mammalian BChE (40). Analysis of the residues comprising the four-helix bundle shows that there is high sequence identity between HuBChE and HuAChE in this region. The most obvious differences are that the leucine residues at positions 373 and 380 (helix F′3) and position 536 (helix H) in HuAChE are replaced by phenylalanines at the corresponding positions 364, 371, and 526 in HuBChE.

Furthermore, there is a fundamental difference between how BChE and AChE are arranged around their respective tetramerization domains. In BChE, disulphide bonds are formed within the canonical dimers (41), and there is no covalent linkage to the proline-rich polypeptide. In AChE, there is a direct disulphide bridge between the monomers of one canonical dimer, but in the other dimer, the same residues (Cys580 of both subunits) make disulphide bonds with two conserved Cys residues adjacent to the PRAD region of ColQ and PRiMA. It would, therefore, be interesting to find out whether the architecture of the mammalian AChE tetramer is similar to that of the BChE tetramer presented here.

Concluding Remarks

We used cryo-EM to determine the structure of a native tetrameric form of a ChE, that of HuBChE. Our experimental structure clearly shows that the tetramer is a markedly nonplanar staggered dimer of dimers, with tetramerization mediated by assembly of the C-terminal WAT helices around a central polyproline II helix. Our findings raise questions concerning differences in oligomeric interactions within AChE and BChE. In particular, the cryo-EM HuBChE tetramer structure differs from previous models based on low-resolution crystal structures of tetrameric Electrophorus AChE (25, 37), which placed the four monomers in roughly the same plane, with the WAT/PRAD protruding out of this plane. It is thus important that cryo-EM structures should be determined for the G4 and collagen-tailed (A12) forms of AChE. Use of an oligomeric polyproline II-like helix around which amphiphilic α-helical sequences wrap as a superhelical motif could be used as a generic tool to stabilize other proteins as tetramers, with the potential to extend their pharmacokinetic lifetimes.

Materials and Methods

Purification of HuBChE from Plasma.

Outdated human plasma from the University of Nebraska Medical Center blood bank was purified by anion exchange chromatography at pH 4.0, followed by affinity chromatography on procainamide-Sepharose at pH 7.0 (32), and affinity chromatography on a Hupresin column at pH 8.0. UniProt P06276 provides the amino acid sequence of 28 residues in the signal peptide and 574 residues in the mature, secreted 85-kDa BChE subunit (42). The HuBChE protein was 99% pure and consisted predominantly of tetramers, as visualized on a nondenaturing gel stained for BChE activity according to Karnovsky and Roots (43) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Thermal Unfolding Assays.

Thermostability of HuBChE was assessed by nano-differential scanning fluorimetry (nanoDSF), performed on a Prometheus NT.48 (NanoTemper) using a temperature ramp of +3 °C/min. Approximately 10 μL of purified protein was loaded into nanoDSF-grade high sensitivity capillaries (NanoTemper). HuBChE was compared with purified G4 TcAChE. HuBChE samples were measured in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, at 3.3 mg/mL, and TcAChE samples in 1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, at 2 mg/mL

Cryo-EM Grid Preparation.

HuBChE, at 3.3 mg/mL in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, was used for cryo-EM. Approximately 3 μL of protein solution was pipetted onto glow-discharged 300-mesh Quantifoil R1.2/1.3 holey carbon grids, which were blotted for either 3 s at blot force 0, or 2 s at blot force −2, on a Vitrobot Mark IV (FEI) at 20 °C and 95% humidity. Grids were immediately plunged into liquid ethane cooled to liquid N2 temperature and stored under liquid N2 before imaging.

Cryo-EM Data Collection.

Data collection was performed on a Talos Arctica (FEI) transmission electron microscope operated at 200 kV, equipped with a postcolumn energy filter (Gatan) operated in zero-loss imaging mode with a 20-eV energy-selecting slit. All images were recorded on a postfilter K2 Summit direct electron detector (Gatan). Movies were collected using EPU (FEI) in superresolution counting mode, at a nominal magnification of 130,000×, corresponding to a pixel size of 1.0285 Å at the specimen level. The exposure time for each movie was 6.3 s with 0.3-s frames. The dose per frame was 2.36 e−/Å2, resulting in a total dose of 49.5 e−/Å2. A total of 4,518 movies were collected, with defocus targets ranging from −1.2 to −2.5 μm.

Cryo-EM Image Processing.

A total of 4,518 movies were imported into Relion 2.1.0 (44). Drift and beam-induced motion were corrected with MotionCor2 (45). Contrast transfer function estimation was performed with GCTF 1.06 (46). All micrographs with a reported maximum resolution worse than 8 Å were discarded, resulting in a set of 3,267 micrographs. From these, 832 particles were manually selected, and used to generate 2D classes, which were then used as references for automated particle picking. A total of 414,189 particles were picked and subjected to two rounds of 2D classification. After 2D classification, 374,086 particles were selected and imported into cryoSPARC (47) for ab initio 3D classification without applying symmetry. The class showing the highest resolution was selected, and the particles were refined with C2 symmetry. The resulting map was then low-pass filtered to 50 Å and used as a template for 3D classification in Relion 3-beta. After two rounds of 3D classification, 111,986 particles were selected for autorefinement in Relion 3-beta, using C2 symmetry. Refinement was performed with a soft mask prepared by low-pass filtering the cryoSPARC map to 15 Å and adding a 10-pixel extension and a 10-pixel soft cosine edge. After postprocessing and sharpening with a B factor of −456.502, the resulting map had a resolution of 5.7 Å (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), based on the “gold standard” FSC = 0.143 criterion (48). Local resolution was estimated in Relion 3-beta.

Model Building.

Initial rigid body fitting was performed in Chimera (49). One asymmetric unit was constructed by independently fitting two HuBChE catalytic domains from PDB ID code 4AQD and homology models of the WAT helices (535–565) into the cryo-EM map. Homology models were constructed with MODELER (50) using the WAT domain of AChE (PDB ID code 1VZJ) as a template. Linkers (residues 532–535) were built and real-space refined in COOT (51). A symmetry-related copy was then generated in COOT. The primary polyproline peptide associated with HuBChE tetramers is from lamellipodin and has the sequence PSPPLPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPPLP (26, 52). We modeled the PRAD as the core of the lamellipodin-derived polyproline sequence (PPPPPPPPPPPPP); the register was not determined due to the resolution. Glycans (from 4AQD) were pruned to include only ones with observed densities in the cryo-EM map.

The complete BChE model was globally real-space refined in Phenix (34, 35). During refinement, secondary structure restraints and NCS restraints (defining two NCS groups: chains a and c as one group, and chains b and d as the second one) were applied. Torsion restraints were also applied by using 4AQD as a reference model, as described in ref. 53.

Data Deposition.

The cryo-EM map of BChE and the coordinates of the model have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) at the Protein Data Bank in Europe (PDBe) (www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/). The accession codes for the map and model are, respectively: EMD-4400 and PDB ID code 6I2T (55).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. M. Vanevic for IT support and Engr. C. W. T. M. Schneijdenberg, J. D. Meeldijk, and Dr. S. C. Howes for management and maintenance of the Utrecht University Electron Microscopy-Square Facility. M.R.L. is funded by a Clarendon Fund-Nuffield Department of Medicine Prize Studentship.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The cryo-EM map of BChE and the coordinates of the model have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) (accession no. EMD-4400) at the Protein Data Bank in Europe (PDBe), www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb/ (PDB ID code 6I2T).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1817009115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Taylor P. Anticholinesterase agents. In: Gilman AG, Goodman SL, Murad F, editors. The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. MacMillan; New York: 1985. pp. 110–129. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson G, Moore SW. Why has butyrylcholinesterase been retained? Structural and functional diversification in a duplicated gene. Neurochem Int. 2012;61:783–797. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masson P, Lockridge O. Butyrylcholinesterase for protection from organophosphorus poisons: Catalytic complexities and hysteretic behavior. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2010;494:107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lockridge O. Review of human butyrylcholinesterase structure, function, genetic variants, history of use in the clinic, and potential therapeutic uses. Pharmacol Ther. 2015;148:34–46. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen VP, et al. Plasma butyrylcholinesterase regulates ghrelin to control aggression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:2251–2256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1421536112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen VP, et al. Butyrylcholinesterase deficiency promotes adipose tissue growth and hepatic lipid accumulation in male mice on high-fat diet. Endocrinology. 2016;157:3086–3095. doi: 10.1210/en.2016-1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mattes CE, et al. Therapeutic use of butyrylcholinesterase for cocaine intoxication. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;145:372–380. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun H, et al. Predicted Michaelis-Menten complexes of cocaine-butyrylcholinesterase. Engineering effective butyrylcholinesterase mutants for cocaine detoxication. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9330–9336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim K, Yao J, Jin Z, Zheng F, Zhan C-G. Kinetic characterization of cholinesterases and a therapeutically valuable cocaine hydrolase for their catalytic activities against heroin and its metabolite 6-monoacetylmorphine. Chem Biol Interact. 2018;293:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qiao Y, Han K, Zhan C-G. Reaction pathways and free energy profiles for cholinesterase-catalyzed hydrolysis of 6-monoacetylmorphine. Org Biomol Chem. 2014;12:2214–2227. doi: 10.1039/c3ob42464b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiao Y, Han K, Zhan C-G. Fundamental reaction pathway and free energy profile for butyrylcholinesterase-catalyzed hydrolysis of heroin. Biochemistry. 2013;52:6467–6479. doi: 10.1021/bi400709v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legay C. Why so many forms of acetylcholinesterase? Microsc Res Tech. 2000;49:56–72. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(20000401)49:1<56::AID-JEMT7>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silman I, Futerman AH. Modes of attachment of acetylcholinesterase to the surface membrane. Eur J Biochem. 1987;170:11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb13662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massoulié J, et al. The polymorphism of acetylcholinesterase: Post-translational processing, quaternary associations and localization. Chem Biol Interact. 1999;119–120:29–42. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(99)00011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scott EM, Powers RF. Human serum cholinesterase, a tetramer. Nat New Biol. 1972;236:83–84. doi: 10.1038/newbio236083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ilyushin DG, et al. Chemical polysialylation of human recombinant butyrylcholinesterase delivers a long-acting bioscavenger for nerve agents in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:1243–1248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211118110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larson MA, Lockridge O, Hinrichs SH. Polyproline promotes tetramerization of recombinant human butyrylcholinesterase. Biochem J. 2014;462:329–335. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alkanaimsh S, et al. Transient expression of tetrameric recombinant human butyrylcholinesterase in Nicotiana benthamiana. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:743. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corbin JM, et al. Semicontinuous bioreactor production of recombinant butyrylcholinesterase in transgenic rice cell suspension cultures. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:412. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Y-J, et al. Recombinant human butyrylcholinesterase from milk of transgenic animals to protect against organophosphate poisoning. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13603–13608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702756104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bon S, Massoulié J. Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. I. Oligomeric associations of T subunits with and without the amino-terminal domain of the collagen tail. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3007–3015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bon S, Coussen F, Massoulié J. Quaternary associations of acetylcholinesterase. II. The polyproline attachment domain of the collagen tail. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3016–3021. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.5.3016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simon S, Krejci E, Massoulié J. A four-to-one association between peptide motifs: Four C-terminal domains from cholinesterase assemble with one proline-rich attachment domain (PRAD) in the secretory pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:6178–6187. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.21.6178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perrier AL, Massoulié J, Krejci E. PRiMA: The membrane anchor of acetylcholinesterase in the brain. Neuron. 2002;33:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00584-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dvir H, et al. The synaptic acetylcholinesterase tetramer assembles around a polyproline II helix. EMBO J. 2004;23:4394–4405. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peng H, Schopfer LM, Lockridge O. Origin of polyproline-rich peptides in human butyrylcholinesterase tetramers. Chem Biol Interact. 2016;259:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krause M, et al. Lamellipodin, an Ena/VASP ligand, is implicated in the regulation of lamellipodial dynamics. Dev Cell. 2004;7:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansen SD, Mullins RD. Lamellipodin promotes actin assembly by clustering Ena/VASP proteins and tethering them to actin filaments. eLife. 2015;4:e06585. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dvir H, Silman I, Harel M, Rosenberry TL, Sussman JL. Acetylcholinesterase: From 3D structure to function. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;187:10–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bourne Y, Grassi J, Bougis PE, Marchot P. Conformational flexibility of the acetylcholinesterase tetramer suggested by x-ray crystallography. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30370–30376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raves ML, et al. Quaternary structure of tetrameric acetylcholinesterase. In: Doctor BP, Taylor P, Quinn DM, Rotundo RL, Gentry MK, editors. Structure and Function of Cholinesterases and Related Proteins. Plenum; New York: 1998. pp. 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lockridge O, Schopfer LM, Winger G, Woods JH. Large scale purification of butyrylcholinesterase from human plasma suitable for injection into monkeys; a potential new therapeutic for protection against cocaine and nerve agent toxicity. J Med Chem Biol Radiol Def. 2005;3:nihms5095. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.3-nihms5095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brazzolotto X, et al. Human butyrylcholinesterase produced in insect cells: Huprine-based affinity purification and crystal structure. FEBS J. 2012;279:2905–2916. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afonine PV, et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2018;74:531–544. doi: 10.1107/S2059798318006551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: A comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sussman JL, et al. Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: A prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science. 1991;253:872–879. doi: 10.1126/science.1678899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pan Y, Muzyka JL, Zhan C-G. Model of human butyrylcholinesterase tetramer by homology modeling and dynamics simulation. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:6543–6552. doi: 10.1021/jp8114995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nachon F, et al. Engineering of a monomeric and low-glycosylated form of human butyrylcholinesterase: Expression, purification, characterization and crystallization. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:630–637. doi: 10.1046/j.0014-2956.2001.02692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kolarich D, et al. Glycoproteomic characterization of butyrylcholinesterase from human plasma. Proteomics. 2008;8:254–263. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen VP, et al. The PRiMA-linked cholinesterase tetramers are assembled from homodimers: Hybrid molecules composed of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase dimers are up-regulated during development of chicken brain. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27265–27278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.113647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lockridge O, Adkins S, La Du BN. Location of disulfide bonds within the sequence of human serum cholinesterase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:12945–12952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lockridge O, et al. Complete amino acid sequence of human serum cholinesterase. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:549–557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Karnovsky MJ, Roots L. A “direct-coloring” thiocholine method for cholinesterases. J Histochem Cytochem. 1964;12:219–221. doi: 10.1177/12.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kimanius D, Forsberg BO, Scheres SHW, Lindahl E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. eLife. 2016;5:1–21. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng SQ, et al. MotionCor2: Anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Methods. 2017;14:331–332. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang K. Gctf: Real-time CTF determination and correction. J Struct Biol. 2016;193:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Punjani A, Rubinstein JL, Fleet DJ, Brubaker MA. cryoSPARC: Algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat Methods. 2017;14:290–296. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenthal PB, Henderson R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:721–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera–A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Šali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li H, Schopfer LM, Masson P, Lockridge O. Lamellipodin proline rich peptides associated with native plasma butyrylcholinesterase tetramers. Biochem J. 2008;411:425–432. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Headd JJ, et al. Use of knowledge-based restraints in phenix.refine to improve macromolecular refinement at low resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68:381–390. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911047834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goddard TD, et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 2018;27:14–25. doi: 10.1002/pro.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leung MR, et al. 2018 CryoEM reconstruction of full-length, fully-glycosylated human butyrylcholinesterase tetramer. Protein Data Bank in Europe. Available at www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/entry/emdb/EMD-4400. Deposited November 1, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.