Significance

Functional impairment and poor recovery following central nervous system injury is due to the failure of injured axons to regenerate and rebuild functional connections. In contrast, axon regeneration occurs in injured peripheral nerves. Expression of regeneration-associated genes is essential to activate the axon regeneration program. Less is known about the contribution of gene inactivation. We reveal an epigenetic mechanism that silences gene expression by ubiquitin-like containing PHD ring finger 1 (UHRF1)-dependent DNA methylation to promote axon regeneration. We suggest that the transient increase in the transcriptional regulator REST, controlled by miR-9 and UHRF1, allows neurons to enter a less mature state that favors a regenerative state. These results provide a better understanding of the transient gene regulatory networks employed by peripheral neurons to promote axon regeneration.

Keywords: axon regeneration, epigenetic, UHRF1, REST, DNMT

Abstract

Injured peripheral sensory neurons switch to a regenerative state after axon injury, which requires transcriptional and epigenetic changes. However, the roles and mechanisms of gene inactivation after injury are poorly understood. Here, we show that DNA methylation, which generally leads to gene silencing, is required for robust axon regeneration after peripheral nerve lesion. Ubiquitin-like containing PHD ring finger 1 (UHRF1), a critical epigenetic regulator involved in DNA methylation, increases upon axon injury and is required for robust axon regeneration. The increased level of UHRF1 results from a decrease in miR-9. The level of another target of miR-9, the transcriptional regulator RE1 silencing transcription factor (REST), transiently increases after injury and is required for axon regeneration. Mechanistically, UHRF1 interacts with DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and H3K9me3 at the promoter region to repress the expression of the tumor suppressor gene phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) and REST. Our study reveals an epigenetic mechanism that silences tumor suppressor genes and restricts REST expression in time after injury to promote axon regeneration.

Functional impairment and poor recovery following central nervous system (CNS) injury is due to the failure of injured axons to regenerate and rebuild functional connections (1, 2). In contrast, axon regeneration and partial functional recovery occur in injured peripheral nerves (3, 4). A more complete understanding of the mechanisms employed by peripheral neurons to promote axon regeneration may provide new strategies to improve recovery after CNS injuries.

Mature neurons in the peripheral nervous system can switch to a regenerative state after axon injury, which is thought to recapitulate, in part, developmental processes (5, 6). Sensory neurons with cell bodies in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) project both a peripheral axon branch into peripheral nerves and a central axon branch through the dorsal root into the spinal cord, providing a unique model system to study the mechanisms that control the axon regeneration program. Indeed, peripheral but not central axon injury elicits transcriptional and epigenetic changes underlying the regenerative response (3, 7). Using this model system, many intrinsic signaling pathways involved in axon regeneration have been identified (4, 8–11). A major focus has been on revealing the regenerative-associated genes (RAGs) promoting axon regeneration (1, 12, 13) and the coordinated regulation of such genes (14, 15). However, the roles and the epigenetic mechanisms by which genes are repressed after injury remain poorly understood.

Epigenetic mechanisms, including covalent modifications of DNA and histones, modulate chromatin structure and function and play an important role in defining gene expression. Recent studies have identified several epigenetic modifications that activate the regenerative program (3, 7). Acetylation of the histone tail, which correlates with a transcriptionally active state, promotes expression of RAGs and axon regeneration in peripheral and central neurons (16–19). DNA demethylation, regulated by the Ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenases (Tets) promotes expression of multiple RAGs upon axon injury in peripheral nerves (20, 21). Whether DNA methylation of cytosine bases at CpG dinucleotides (5mC), which generally leads to gene silencing (22–24), contributes to regenerative responses remains incompletely understood (7). Genome-wide changes in DNA methylation occur following nerve injury in DRGs (19), with hypermethylation prevailing over hypomethylation at early time points after injury (25), suggesting a potential role for DNA methylation in the regeneration program. In support of this notion, administration of folate was shown to increase DNA methylation and axon regeneration in the injured spinal cord (26), but which cell types displayed changes in DNA methylation was not determined.

DNA methylation in neurons is dynamically regulated during development as well as in response to physiological and pathological stimuli (25, 27, 28). DNA methylation is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), including DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b. Whereas DNMT1 is primarily responsible for the maintenance of DNA methylation, DNMT3a and DNMT3b are involved in de novo methylation patterns during cellular differentiation (29, 30). How DNMTs target specific genetic regions remains unclear (24). DNMTs can bind to transcription factors or components of repressor complexes to target methylation to DNA. For example, the epigenetic regulator ubiquitin-like containing PHD ring finger 1 (UHRF1, also known as Np95) coordinates gene silencing through the recruitment of DNMT1 and DNMT3a/b (31–33). UHRF1 recognizes methyl groups on histone H3, specifically H3K9me2/3 as well as methylated DNA (33–36). Most studies on UHRF1 focus on cancer cells (37) and neuronal development (38), but the role of UHRF1 in peripheral neurons remains largely unknown.

Another mechanism that shapes gene expression is the miRNA system. miRNAs are small, evolutionarily conserved, noncoding RNAs, 18–25 nt in length, that bind to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of target genes, causing either target messenger RNA (mRNA) degradation or reduced protein translation (39). An increasing number of miRNAs have been shown to be involved in axon regeneration (7). miR-9 down-regulation after sciatic nerve axotomy was shown to be critical for axon regeneration (40). Since miR-9 increased expression confers a mature neuronal fate (39), the decrease in miR-9 after axon injury is consistent with the notion that injury recapitulates in part developmental processes by switching back to a growth-competent state (5, 6).

Here, we reveal that DNA methylation contributes to promote robust axon regeneration both in vitro and in vivo. UHRF1, a critical epigenetic regulator involved in silencing tumor suppressor genes via DNA methylation is a target of miR-9 in sensory neurons. UHRF1 increased expression upon axon injury, resulting from a decrease in miR-9, is required for axon regeneration. Another target of miR-9, the transcriptional regulator RE1 silencing transcription factor (REST) transiently increases after axon injury and is also required for axon regeneration. Mechanistically, UHRF1 interacts with DNMTs and H3K9me3 to methylate the promoter region of the tumor suppressors gene phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) as well as REST, thereby triggering their silencing. Our study reveals that injury-induced gene silencing by DNA methylation promotes axon regeneration in the adult peripheral nervous system.

Results

DNA Methylation Is Required for Axon Regeneration.

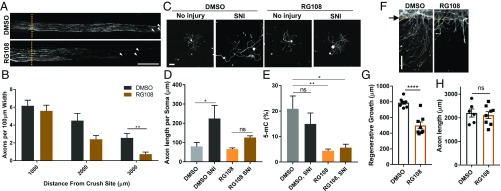

To directly examine if DNA methylation is required for axon regeneration, we chose RG108, a direct DNMT inhibitor over 5-azacytidine, because it inhibits methylation without incorporation into DNA and has been shown to be effective in the CNS (41, 42). We treated mice with RG108 2 h before a sciatic nerve crush injury (SNI), repeated the treatment 1 d later, and measured axon regeneration 3 d after injury. Compared with vehicle controls, RG108 treatment reduced the length of axons regenerating past the crush site (Fig. 1 A and B). We next tested if DNA methylation contributes to the priming effect of a conditioning injury, in which DRG neurons exposed to a prior conditioning injury show a dramatic improvement in axon regeneration compared with that of a naïve neuron (43). We treated mice with RG108 as described above in Fig. 1A, and adult DRG neurons were dissected from mice that received or not a prior (3 d) SNI and cultured for 20 h. As expected, a prior nerve injury enhanced growth capacity leading to longer neurites (Fig. 1 C and D). RG108 treatment partially blocked the conditioning injury effect (Fig. 1 C and D) and decreased global 5mC levels in control uninjured and injured DRG (Fig. 1E). These experiments indicate that DNA methylation is required for the priming effects of a conditioning injury but do not allow us to determine which cell types within DRG require active DNA methylation to stimulate axon regeneration.

Fig. 1.

DNA methylation is required for axon regeneration. (A) Representative longitudinal sections of sciatic nerve from DMSO or RG108 treated mice. Nerves were collected 3 d after SNI and sections were stained for SCG10. Dotted lines indicate the crush site. Arrowheads point to the longest axons. (B) In vivo axon regeneration was calculated from images in A. The number of regenerating axons stained with SCG10 was measured at various distances from the crush site (n = 5 biological replicates for each, respectively; **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (C) Adult DRG neurons dissected from DMSO- or RG108-treated mice that received or not a prior (3 d) SNI were cultured for 20 h and stained with the neuronal-specific marker TUJ1. (D) Average axon length per soma was calculated from images in C. Total neurite length was measured and normalized to the number of neuronal cell soma to calculate the average axon length (n = 4 biological replicates for each; *P < 0.05, ns, not significant by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (E) Measurement of global DNA methylation. The global DNA methylation assay was performed using the MethylFlash Methylated DNA 5-mC Quantification Kit with genomic DNA from whole DRG 3 d after SNI (n = 4–5 biological replicates for each; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (F) DRG spot-cultured neurons were treated with DMSO or RG108 (100 μM) 10 min before injury and 24 h later. DRG spot-cultured neurons were fixed and stained for SCG10 40 h after axotomy. Arrow and dotted lines indicate the axotomy site. (G) Regenerating axon length of DRG spot-cultured neurons was measured 40 h after axotomy from images in F (Individual data plotted; n = 8 biological replicates; ****P < 0.0001 by t test; mean ± SEM). (H) DRG spot-cultured neurons were treated at DIV7 and DIV8 with DMSO or 100 μM RG108. Axon lengths of DRG spot-cultured neurons were measured 40 h after initiation of the treatment (n = 6–8 biological replicates for each, ns, not significant by t test; mean ± SEM). (Scale bars A, 500 μm; C, 100 μm; F, 200 μm.)

We thus tested if DNA methylation is required in neurons for axon regeneration by performing an in vitro regeneration assay. In this system, DRG neurons are seeded within a defined area, allowing their axons to extend radially (16, 44, 45). Axotomy is performed at days in vitro (DIV)7, and DRG are stained 40 h following axotomy for SCG10, a marker for regenerative axons (46). Regenerative axon growth is quantified by measuring the length of SCG10-positive axons from the axotomy line to the axon tip. Cultures treated with RG108 displayed impaired axon regeneration compared with vehicle-treated cultures (Fig. 1 F and G). DNA methylation is required after injury for regenerative growth, but not for elongating growth, as RG108 treatment did not affect axon growth in naïve, uninjured cultures (Fig. 1H). Together, these experiments indicate that active DNA methylation following axon injury is required for robust axon regeneration in sensory neurons.

UHRF1 Level Increases After Peripheral Axon Injury in DRG Neurons.

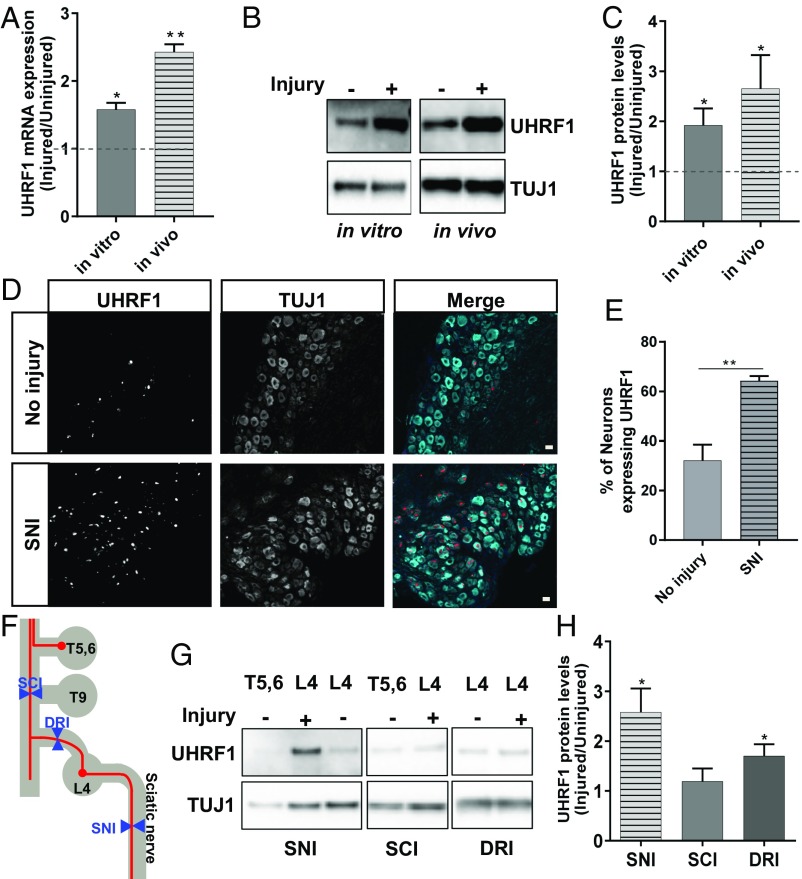

Since the expression levels of DNMT3a and DNMT1 do not change in DRG after nerve injury (21), we focused our study on ubiquitin-like containing PHD ring finger 1 (UHRF1), a regulator of DNA methylation (37). We first determined if axon injury alters UHRF1 mRNA and protein levels in DRG neurons. We observed an increase in UHRF1 mRNA and protein levels 24 h following in vitro axotomy and 3 d following SNI in vivo (Fig. 2 A–C). To confirm that the increase in UHRF1 levels occur in sensory neurons in vivo, L4 DRG were dissected 3 d after SNI and stained for UHRF1 and TUJ1, a neuron-specific marker, and compared with uninjured contralateral DRG. The number of neurons expressing UHRF1 increased following SNI (Fig. 2 D and E). We then compared the UHRF1 protein changes after peripheral SNI, dorsal root injury (DRI), or T9 spinal cord hemisection injury (SCI). T5, T6, and L4 DRG were dissected 3 d following SNI, L4 DRI, or T9 SCI and analyzed by Western blot for UHRF1. The T9 SCI damages bilaterally the centrally projecting axons coming from the L4 DRG but does not affect the more rostral DRG at T5,6 (Fig. 2F). We thus used DRG T5,6 as a noninjured control for SCI and contralateral L4 DRG for DRI and SNI (Fig. 2F). Whereas SNI increased UHRF1 protein levels in DRG neurons, DRI only modestly increased UHRF1 protein level and SCI did not affect UHRF1 levels (Fig. 2 G and H). These experiments indicate that the injury-induced increase in UHRF1 levels are specific to peripheral axon injury.

Fig. 2.

Induction of UHRF1 in sensory neurons following axon injury. (A) Expression level of UHRF1 mRNA was analyzed by RT-qPCR. RNA was extracted from DRG spot-cultured neurons 24 h after axotomy for in vitro analysis or from L4 and L5 DRG 3 d after SNI for in vivo analysis (n = 3 biological replicates for each; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by t test; mean ± SEM). (B) Representative Western blot of DRG spot-cultured neurons 24 h after axotomy for in vitro and L4 and L5 DRGs dissected 3 d after SNI for in vivo experiments. TUJ1 serves as a loading control. (C) Normalized intensity was calculated from Western blot images in B (n = 7 biological replicates for in vitro and n = 8 biological replicates for in vivo, *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). (D) Representative sections of mouse L4 DRGs dissected 3 d after SNI and stained for UHRF1 and TUJ1. (Scale bars: 50 μm.) (E) Percentage of DRG neurons expressing UHRF1 was calculated from images in D (n = 3 biological replicates; **P < 0.01 by t test; mean ± SEM). (F) Scheme representing injury location and DRG collected for the experiment in G. (G) Representative Western blot from the indicated mouse DRGs dissected 3 d after SNI, SCI, or DRI and analyzed by Western blot for UHRF1 and TUJ1 as a loading control. Protein samples were prepared from different mice for each injury. (H) Normalized intensity was calculated from images in G; n = 8 biological replicates for each injury; *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM).

UHRF1 Promotes Axon Regeneration in DRG Neurons.

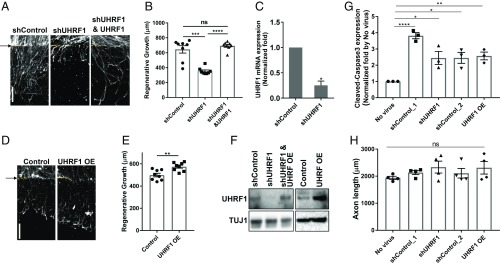

To test if UHRF1 plays a role in axon regeneration, we used the in vitro axotomy assay. DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with lentivirus encoding control shRNA or shRNA targeting UHRF1. UHRF1 knockdown significantly impaired axon regeneration, and this effect was rescued by expressing human UHRF1 (Fig. 3 A and B). Expression of human UHRF1 had a moderate effect in enhancing axon regeneration (Fig. 3 D and E). We verified that the shRNA targeting UHRF1 reduced UHRF1 at both the protein and mRNA level (Fig. 3 C and F) and only modestly affected cell death (labeled by cleaved caspase 3) and axon growth in naïve, uninjured cultures compared with control shRNA (Fig. 3 G and H). These results indicate that the up-regulation of UHRF1 levels following axon injury is important for axon regeneration.

Fig. 3.

UHRF1 expression is required for axon regeneration. (A) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA (control), shRNA targeting UHRF1 or human UHRF1 (UHRF1OE), fixed and stained for SCG10 40 h after axotomy. Arrow and dotted lines indicate the axotomy site. (B) Regenerative axon growth was measured 40 h after axotomy from the image in A. Individual data plotted; n = 8 biological replicates; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns, not significant by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM. (C) UHRF1 mRNA levels were analyzed by RT-qPCR in control DRG spot-cultured neurons or DRG spot-cultured neurons expressing shRNA targeting UHRF1 (n = 3 biological replicates; *P < 0.05 by t test). (D) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA (control) or human UHRF1 (UHRF1 OE), fixed and stained for SCG10 24 h after axotomy. A shorter time point after axotomy was used in this experiment to visualize the enhanced regeneration effect. Arrow and dotted lines indicate the axotomy site. (E) Regenerative axon growth was measured at 24 h after axotomy from images in D (individual data plotted; n = 8 biological replicates; **P < 0.01 by t test; mean ± SEM). (F) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with control shRNA (control), shRNA targeting UHRF1, or human UHRF1 (UHRF1OE) lentivirus. Expression levels of UHRF1 was analyzed by Western blot. TUJ1 serves as a loading control. (G) Measurement of cell death effect following UHRF1 knockdown or overexpression. DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA, shRNA-targeting UHRF1, or human UHRF1 (UHRF1OE) at DIV1, fixed, and stained for cleaved-caspase3 and DAPI at DIV7. shControl_1 is the control for shUHRF1 and shControl_2 is the control for UHRF1OE as we used different amounts of lentivirus for shUHRF1 and UHRF1OE. The number of DRG neurons stained for cleaved-caspase3 was normalized to the number of DRG neurons stained with DAPI. The values are averaged from three spots per biological replicate (n = 3 biological replicates for each; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (H) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with indicated lentivirus at DIV1, fixed, and stained for TUJ1 at DIV7. shControl_1 is the control for shUHRF1 and shControl_2 is the negative control for UHRF1OE (n = 4 biological replicates for each; ns, not significant by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (Scale bars: 200 μm.)

UHRF1 Is a Target of miR-9 in Sensory Neurons.

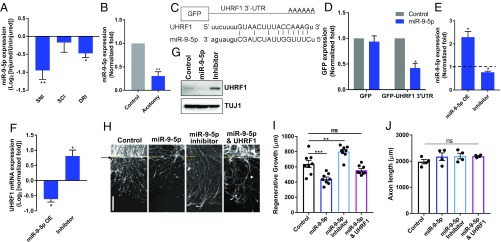

Since UHRF1 is regulated by miR-9-5p in colorectal cancer cells (47) and miR-9-5p represses axon growth in both peripheral and central neurons (40, 48), we tested if miR-9-5p regulate UHRF1 levels in sensory neurons. We found that the level of miR-9-5p was significantly decreased 3 d following SNI, as previously reported for premiR-9 (40). DRI induced a decrease in miR-9-5p, whereas SCI did not significantly decrease miR-9-5p levels (Fig. 4A). Down-regulation of miR-9-5p also occurred in cultured neurons 24 h after in vitro axotomy (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Axon injury reduces the levels of miR-9-5p that target UHRF1 to promote axon regeneration. (A) RT-qPCR analysis of miR-9-5p 3 d after in vivo SNI, SCI, or DRI (n = 5–7 biological replicates; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by t test; mean ± SEM). (B) RT-qPCR analysis of miR-9-5p 24 h after in vitro axotomy (n = 4 biological replicates; **P < 0.01 by t test; mean ± SEM). (C) Schematic representation of GFP-UHRF1 3′-UTR reporter constructs and the sequence of miR-9-5p seeds in UHRF1 3′UTR. (D) Relative GFP reporter activity was assayed 4 d after transduction of lentivirus expressing GFP or GFP-UHRF1 3′UTR in combination with lentivirus expressing control or miR-9-5p in HEK-293T cells. The expression of GFP in each group was analyzed by Western blot. Normalized intensity was calculated from Western blot images (n = 3 different batch of cells; *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). (E) Mature miR-9-5p expression levels were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Mouse DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with lentivirus expressing miR-9-5p or an inhibitor of miR-9-5p (n = 3–4 biological replicates; *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). (F) Expression level of UHRF1 mRNA was analyzed by RT-qPCR in neurons expressing control, miR-9-5p, or neurons expressing an inhibitor of miR-9-5p (n = 3–4 biological replicates; *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). (G) As in E but expression levels of UHRF1 was analyzed by Western blot with anti-UHRF1 antibody. TUJ1 serves as a loading control. (H) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with the indicated lentivirus, fixed, and stained for SCG10 40 h after axotomy. (Scale bar: 200 μm.) Arrow and dotted lines indicate the axotomy site. (I) Regenerative axon length of DRG spot-cultured neurons was measured at 40 h after axotomy from A (individual data plotted; n = 8 biological replicates; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (J) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with the indicated lentivirus at DIV1. Axon lengths of DRG spot-cultured neurons was measured at DIV7 (n = 4 biological replicates for each; ns, not significant by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM).

The 3′UTR of UHRF1 contains a seed sequence for miR-9-5p (Fig. 4C). Using a GFP reporter assay in HEK293T cells, we observed that miR-9-5p can effectively target UHRF1 3′UTR (Fig. 4D). To determine if miR-9 regulates UHRF1 levels in sensory neurons, we examined the expression levels of UHRF1 in cultured DRG neurons expressing miR-9-5p or its specific inhibitors (Fig. 4E). When miR-9-5p was expressed in cultured DRG neurons, UHRF1 mRNA level and protein level were decreased (Fig. 4 F and G), whereas the expression levels of UHRF1 was increased by the expression of the miR-9-5p–specific inhibitor (Fig. 4 F and G). These data indicate that UHRF1 is a target of miR-9-5p in sensory neurons.

Expression of miR-9-5p was shown to impair axon regeneration in vivo (40). Since miR-9-5p targets UHRF1, we tested if miR-9-5p changes the regenerative capacity of DRG neurons in vitro. Expression of miR-9-5p impaired axon regeneration compared with control (Fig. 4 H and I). Expression of the miR-9-5p inhibitor showed an increase in axon regeneration (Fig. 4 H and I). The impaired axon regeneration mediated by miR-9-5p was rescued by UHRF1 expression (Fig. 4 H and I), indicating that UHRF1 functions downstream of miR-9. These effects were specific to regenerative growth, as neither miR-9-5p nor its inhibitor affected significantly axon growth in naïve conditions (Fig. 4J).

REST Is a Target of miR-9 in Sensory Neurons and Regulates Axon Regeneration.

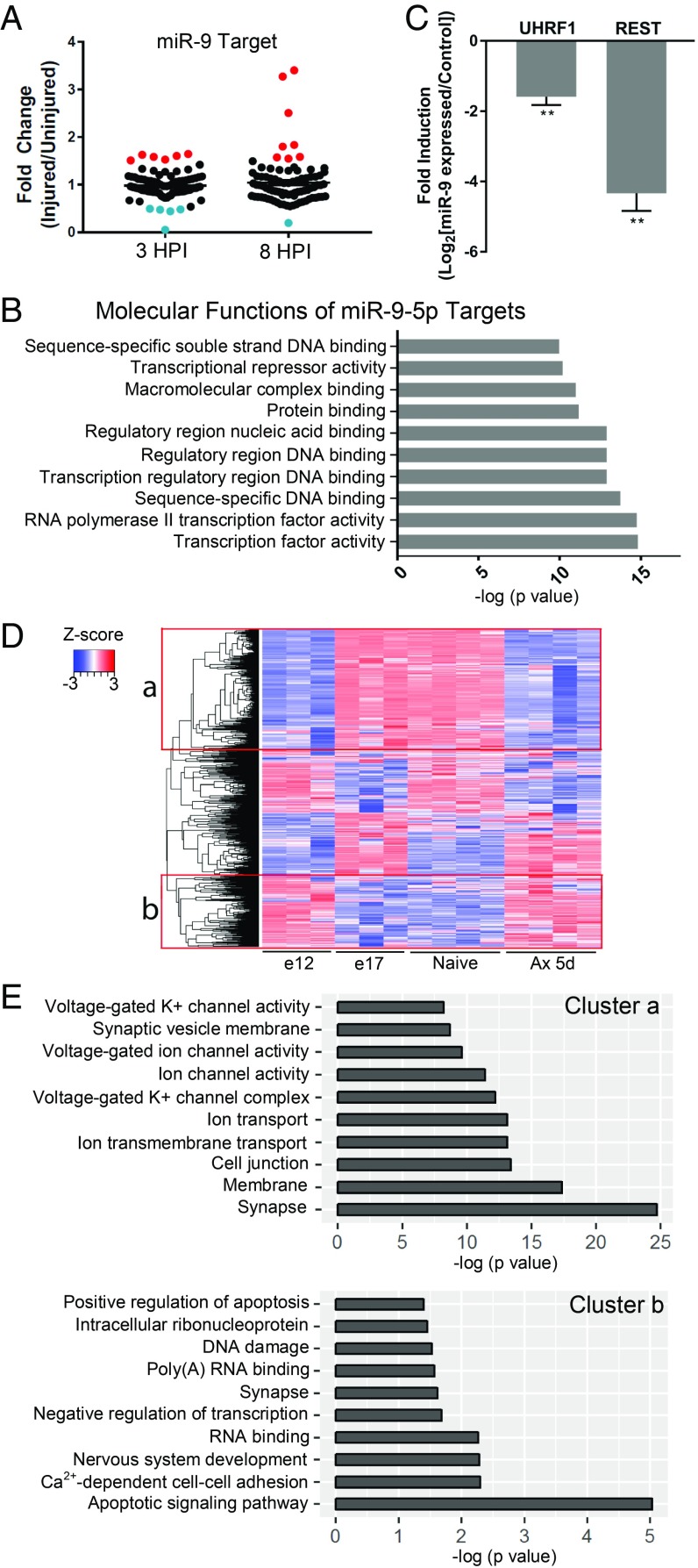

Further supporting a role for miR-9 in axon regeneration, we found that several known miR-9 targets were up-regulated in our previous microarray analysis (16) (Fig. 5A). This is likely an underrepresentation of miR-9’s effect as most mammalian miRNA targets are imperfectly paired and are thus translationally repressed (49). Gene ontology (GO) analysis of the molecular functions of known and predicted miR-9-5p targets revealed that the targets of miR-9 primarily encode transcription factors or chromatin modifiers (Fig. 5B), consistent with UHRF1 functioning downstream of miR-9 in axon regeneration.

Fig. 5.

REST expression is regulated by miR-9 following axon injury in sensory neuron. (A) Differential expression of validated miR-9 targets in our previously published array (16). (B) Enriched GO molecular functions from analyzing miR-9-5p predicted and validated targets. (C) Expression level of UHRF1 and REST mRNA was analyzed by RT-qPCR in neurons expressing control or miR-9-5p/3p (n = 4 biological replicates; **P < 0.01 by t test; mean ± SEM). (D) Heatmap of REST target genes in DRG neurons at E12.5 and E17.5 and DRG neurons of naïve and 5 d after SNI. (E) Enriched GO processes for a and b cluster in D is shown.

Another well-characterized target of miR-9 is REST (also known as NRSF) (50, 51). REST acts as a repressor of multiple mature neuron-specific genes (52, 53). We observed that miR-9 regulates REST levels in sensory neurons, as miR-9 expression in cultured DRG neurons decreased the levels of REST and UHRF1 mRNA (Fig. 5C). The role of REST in axon regeneration has not been explored in detail, although a previous analysis suggested a role for REST-dependent transcriptional regulation after injury (54). To test if REST plays a role in the regenerative response, we analyzed known REST target genes (55) from previously published RNA-seq datasets that analyzed DRG neurons at embryonic day (E)12.5 (axon growth stage) and E17.5 (synapse formation stage) (56) and DRG neurons in naïve and injured (5 d after SNI) conditions (57). Heatmaps revealed two clusters with an opposite trend (Fig. 5D). GO analysis revealed that genes in cluster “a” were up-regulated from E12.5 to E17.5 and down-regulated in DRG following nerve injury, and correlate with synapse and ion transport (Fig. 5E). Genes in cluster “b” were down-regulated from E12.5 to E17.5, are increased after nerve injury, and are related to apoptosis and nervous system development (Fig. 5E). This analysis reveals that a subset of REST target genes is regulated by injury to recapitulate in part a less mature, more growth competent state.

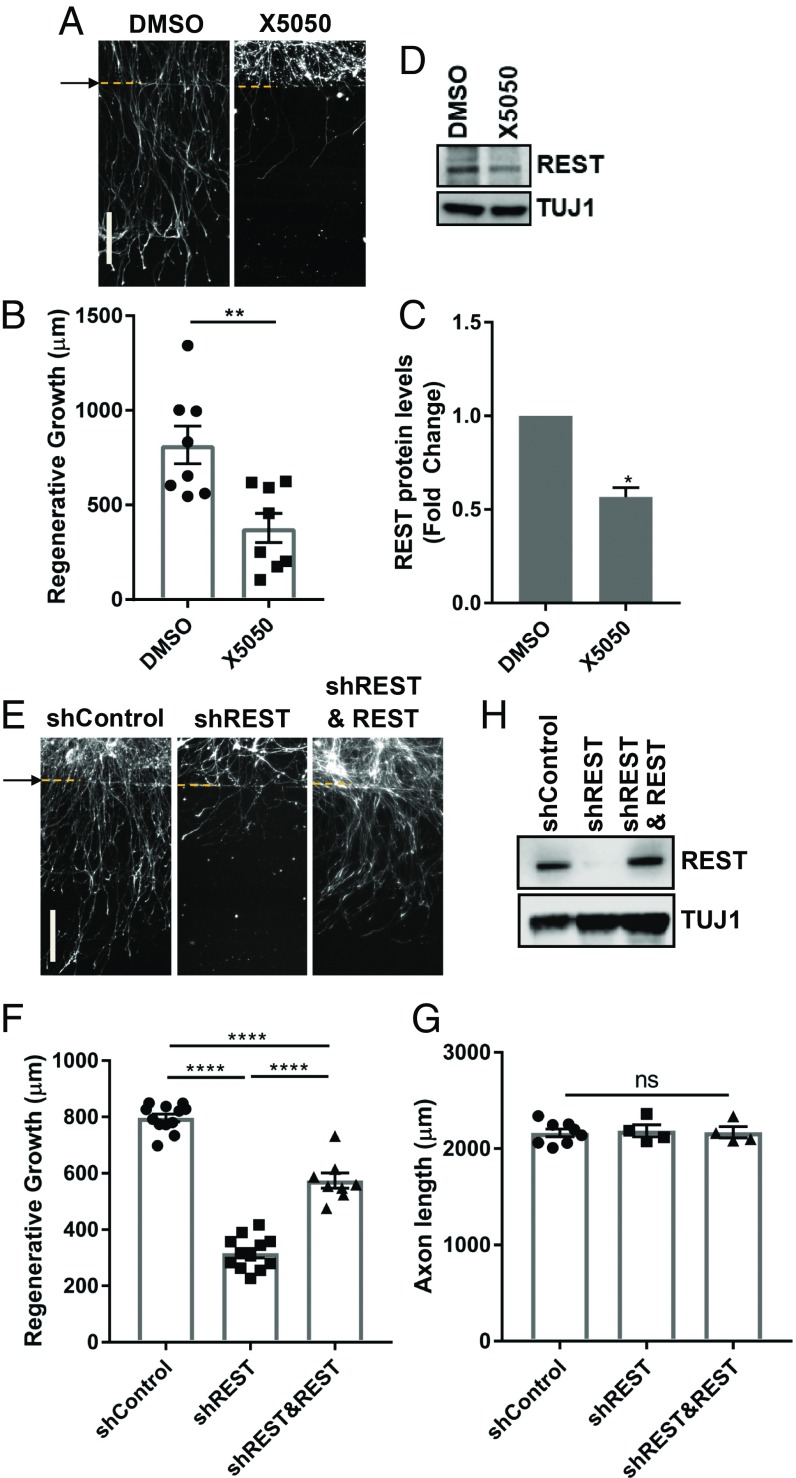

To directly test if REST is required for axon regeneration, we used X5050, a REST inhibitor that leads to REST protein degradation (58). X5050 treatment of DRG spot-culture before axotomy efficiently reduced REST protein levels and impaired axon regeneration (Fig. 6 A–D). REST knockdown also impaired axon regeneration, and this effect was partially rescued by expressing human REST (Fig. 6 E, F, and H). These effects were specific to regenerative growth, as axon growth in naïve conditions was not affected (Fig. 6G). Together, these results indicate that downstream of miR-9, REST and UHRF1 are required for robust axon regeneration.

Fig. 6.

REST expression is required for axon regeneration. (A) DRG spot-cultured neurons were treated with DMSO or 50 μM X5050 10 min before injury, fixed, and stained for SCG10 40 h after axotomy. Arrow and dotted lines indicate the axotomy site. (B) Regenerated axon length of DRG spot-cultured neurons was measured 40 h after axotomy from images in A (Individual data plotted; n = 8 biological replicates; **P < 0.01 by t test; mean ± SEM). (C) Normalized intensity was calculated from Western blot analysis of DRG spot-cultured neurons after treatment of DMSO or 50 μM X5050 (n = 3 biological replicates, *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). (D) Representative image from Western blot analysis of DRG spot-cultured neurons treated with DMSO or 50 μM X5050 for 24 h. Expression levels of REST were analyzed by Western blot. TUJ1 serves as a loading control. (E) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA (shcontrol), shRNA targeting REST or human REST, fixed, and stained for SCG10 40 h after axotomy. Arrow and dotted lines indicate the axotomy site. (F) Regenerative axon growth was measured 40 h after axotomy from images in E. Individual data plotted; n = 8–12 biological replicates; ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM. (G) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with the indicated lentivirus, fixed, and stained for TUJ1 at DIV7 (n = 4–8 biological replicates for each; ns, not significant by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (H) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with control shRNA (shcontrol), shRNA-targeting REST, or human REST lentivirus. Expression levels of REST was analyzed by Western blot. TUJ1 serves as a loading control. (Scale bars: 200 μm.)

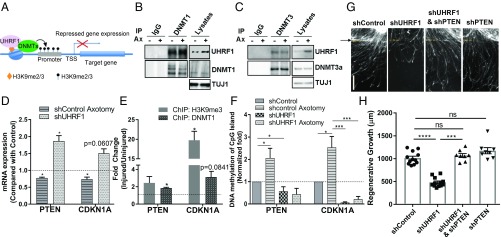

UHRF1 Represses Tumor Suppressor Gene Expression via Promoter DNA Methylation.

UHRF1 is highly expressed in cancer cells, where it contributes to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes (37). Given the importance of reducing the levels of tumor suppressor genes to promote axon regeneration (59–63), we explored the possibility that UHRF1 functions to silence tumor suppressor genes after axon injury. UHRF1 silences gene expression by interacting with dimethylated and trimethylated H3K9 and recruiting of DNMT1 and DNMT3a to promote DNA methylation (31, 32, 58) (Fig. 7A). We first investigated which DNMT isoforms cooperate with UHRF1 in sensory neurons using coimmunoprecipitation in extracts prepared from naïve and injured (24 h) spot-cultured DRG neurons. UHRF1 interacted with DNMT1 and DNMT3a in both control and injured conditions (Fig. 7 B and C). While the levels of UHRF1 were increased 24 h after in vitro axotomy, the levels of DNMT1 and DNMT3a remained constant, consistent with previous reports (21).

Fig. 7.

UHRF1 represses tumor suppressor gene expression via promoter DNA methylation. (A) Model illustrating current known mechanism of UHRF1-medidated gene promoter methylation. UHRF1 binding to H3K9me2/3 recruits DNMTs for promoter methylation. (B and C) Uninjured or injured (24 h) DRG spot-cultured neurons were collected and lysates subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-IgG, anti-DNMT1 (B), or anti-DNMT3a (C) antibody and followed by immunoblot with the indicated antibodies. Representative Western blot from three independent experiments is shown. (D) Expression level of PTEN and CDKN1A by RT-qPCR analysis. RNA was extracted from uninjured or injured (24 h) DRG spot-cultured neurons infected with control shRNA or uninjured DRG spot-cultured neurons infected with shRNA-targeting UHRF1 (n = 3–4 biological replicates; *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). (E) ChIP-qPCR assay for H3K9me3 and DNMT1 around the CpG promoter region of PTEN and CDKN1A using uninjured DRG spot-cultured neurons and DRG spot-cultured neurons 24 h after axotomy (n = 3–4 biological replicates; *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). The fold change after injury is plotted. (F) Measurement of PTEN and CDKN1A CpG island DNA methylation in uninjured DRG spot-cultured neurons and DRG spot-cultured neurons 24 h after axotomy, infected with control shRNA or shRNA-targeting UHRF1 (n = 3 biological replicates for each; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (G) DRG spot-cultured neurons were infected with lentivirus expressing control shRNA (shcontrol), shRNA targeting UHRF1 or shRNA targeting PTEN, fixed, and stained for SCG10 40 h after axotomy. (Scale bar: 200 μm.) Arrow and dotted lines indicate the axotomy site. (H) Regenerative axon growth was measured 40 h after axotomy from the images in G. Individual data plotted; n = 8–12 biological replicates; ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns, not significant by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM.

The signaling network of tumor suppressors plays crucial roles in the regulation axon regeneration (59). The levels of several tumor suppressors, including PTEN and p21 (CDKN1A), are altered in injured peripheral nerves and impact peripheral nerve regeneration (59). PTEN deletion increases axon regeneration in the CNS (60, 62) and also enhances outgrowth of peripheral axons (63, 64). CDKN1A expression decreases after injury in cultured neurons (45), and UHRF1 is known to epigenetically silence CDKN1A (65, 66). We thus tested if UHRF1 represses PTEN and CDKN1A expression in injured sensory neurons. Whereas PTEN and CDKN1A levels were reduced after axon injury in control neurons, UHRF1 knockdown resulted in increased levels of PTEN and CDKN1A (Fig. 7D). ChIP-qPCR assay revealed that H3K9me3 and DNMT1 were enriched at the CpG promoter region of PTEN and CDKN1A after in vitro axotomy (Fig. 7E). To determine if CpG island DNA methylation of PTEN and CDKN1A promoters is altered after injury, we carried out qPCR for PTEN and CDKN1A after cleavage with a methylation-sensitive and/or a methylation-dependent restriction enzyme. Compared with uninjured neurons, the CpG island methylation of PTEN and CDKN1A significantly increased following in vitro axotomy (Fig. 7F). These results reveal that PTEN and CDKN1A are down-regulated at the transcriptional level following injury in a UHRF1-dependent manner. Further supporting the role of PTEN transcriptional repression by UHRF1, we found that the impaired axon regeneration mediated by UHRF1 knockdown was rescued by PTEN knockdown (Fig. 7 G and H). In this assay, PTEN knockdown alone showed a trend toward an increase in axon regeneration, similarly to what we observed with UHRF1 expression (Fig. 3 D and E). These results indicate that that UHRF1-dependent reduction in PTEN levels via epigenetic silencing is required for robust axon regeneration.

UHRF1 Epigenetically Represses REST Expression.

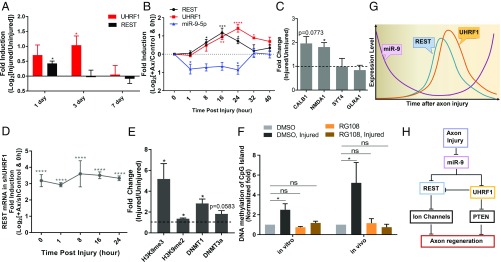

REST expression is regulated at the posttranscriptional levels in sensory neurons (67) and is also regulated at the transcriptional level by gene methylation in small-cell lung cancer (68). To test the possibility that UHRF1 regulates REST levels after injury, we first determined the temporal changes in REST and UHRF1 mRNA levels in DRG in vivo following SNI. The mRNA level of REST increased 1 d after SNI and returned to baseline at 3 d after injury, whereas UHRF1 mRNA increased at 1 d, remained high at 3 d, and returned to baseline at 7 d (Fig. 8A). Because whole DRG contain a mixed population of cells, we also examined the neuron-specific temporal changes in miR-9-5p, REST, and UHRF1 expression in DRG spot-cultured neurons at different time points after axotomy. miR-9-5p levels decreased starting 1 h after in vitro axotomy and returned to baseline at 32 h after injury (Fig. 8B). REST mRNA levels increased over time, reaching a maximum at 16 h and returning to basal levels 32 h after axotomy (Fig. 8B). UHRF1 mRNA also increased over time, reaching a maximum at 24 h after axotomy and decreased toward basal levels 40 h after axotomy (Fig. 8B), a time at which injury-induced gene expression changes return to basal level in this assay (16). ChIP-qPCR assay of DRG spot-cultured neurons 16 h after injury reveals that REST is enriched at the promoter of CALB1 and NMDA1, two known REST target genes (69) (Fig. 8C), suggesting that REST regulates gene expression in injured neurons, in addition to its role in uninjured neurons (67).

Fig. 8.

UHRF1 epigenetically represses REST expression. (A) Expression level of UHRF1 and REST were analyzed by RT-qPCR. RNA was extracted from L4 and L5 DRG dissected 1, 3, and 7 d after sciatic nerve injury for in vivo analysis (n = 4–5 biological replicates for each; *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). (B) RT-qPCR analysis of UHRF1, REST, and miR-9–5p mRNA levels. RNA was extracted from DRG spot-cultured neurons at the indicted time points after axotomy (n = 3–8 biological replicates; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (C) ChIP-qPCR assay for REST around the promoter region of REST’s target genes using uninjured DRG spot-cultured neurons and DRG spot-cultured neurons 16 h after axotomy (n = 3 biological replicates; *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). Fold change after injury is plotted. (D) Expression level of REST was analyzed by RT-qPCR at the indicated time points after axotomy in DRG neurons in which UHRF1 was knocked down (n = 3 biological replicates; ****P < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (E) ChIP-qPCR assay for H3K9me3, H3K9me2, DNMT1 and DNMT3a at the CpG promoter region of REST from uninjured DRG spot-cultured neurons or DRG spot-cultured neurons 24 h after axotomy (n = 3–5 biological replicates; *P < 0.05 by t test; mean ± SEM). Fold changed after injury is plotted. (F) Measurement of REST CpG island DNA methylation in DRG spot-cultured neurons 32 h after axotomy with treatment of DMSO or 100 μM RG108 for in vitro analysis and in whole DRG 3 d after SNI with DMSO or 9 mg/kg RG108 treatment for in vivo analysis (n = 8–11 biological replicates for in vitro analysis and n = 4–5 biological replicates for in vivo analysis; *P < 0.05, ns, not significant by one-way ANOVA; mean ± SEM). (G and H) Model illustrating the temporal changes in miR-9, REST, and UHRF1 induced by axon injury. The earliest event involves the down-regulation of miR-9, which allows the increase in levels of UHRF1 and REST. UHRF1 suppresses the expression of tumor suppressor genes, such as PTEN, while REST represses the expression of mature neuronal genes, including ion channels. Subsequently, UHRF1 shuts down the expression of REST. The transition between a naïve state and a regenerative state involves a feedback loop that controls the temporal profile of REST expression. The kinetic profile of REST expression allows neurons to enter a less mature state without leading to axon disintegration. The temporal relationships (G), as well as the topological interactions (H) among miR-9, REST, and UHRF1 and selected target genes, are shown.

Next, we tested if UHRF1 silences REST expression via DNA methylation after axon injury. REST mRNA was up-regulated in naïve and injured DRG neurons in which UHRF1 was knocked down (Fig. 8D). Mechanistically, we found that repression of REST is associated with the enrichment of H3K9me3 and DNMT1 at the REST promoter and with increased REST promoter CpG methylation (Fig. 8 E and F). RG108 treatment efficiently blocked the increase in CpG island DNA methylation of REST promoter after in vitro axotomy and after SNI (Fig. 8F). These experiments were performed 32 h after injury, a time at which REST levels return to baseline, but UHRF1 levels are still higher than uninjured control (Fig. 8B). Together, these results suggest that the increase in UHRF1 after injury promotes the epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes and also restricts at the transcriptional level REST expression in time (Fig. 8 G and H).

Discussion

Injured adult sensory neurons gain the capacity to regrow axons after injury via the activation of a proregenerative transcriptional program. Here, we show that gene silencing via DNA methylation contributes to removing the barrier to axon regeneration. Our findings also suggest that the transient increase in REST, controlled by miR-9 and UHRF1, allows neurons to enter a less mature neuronal state that favors the establishment of a proregenerative state.

DNA demethylation mediated by Tet enzyme was shown to promote RAG expression upon axon injury in peripheral nerves (20, 21), but whether DNA methylation is implicated in regenerative responses has remained unclear (7). A high-throughput DNA methylation microarray revealed only a modest number of genes exhibiting differential methylation following injury, and none of these genes were associated with regeneration (19). Another study revealed genome-wide changes in DNA methylation following nerve injury in DRGs, with hypermethylation prevailing over hypomethylation early (3 d) after injury and the DNA methylation changes recapitulating developmental neonatal stage (25). A limitation in these studies was the use of whole DRG in which neurons are outnumbered by glial cells and other cell types (70, 71). Using a DNMT inhibitor in vivo and in purified neurons in vitro, we revealed a critical role for DNA methylation in axon regeneration. Since no significant changes in gene expression for DNMT1 and DNMT3a were observed (19, 21), we examined the role of UHRF1, which interacts with both DNMT1 and DNMT3 and found that UHRF1 was required for robust axon regeneration. DNMT3a and DNMT1 functionally cooperate during de novo methylation of DNA (29, 31), and DNMT3A interaction with transcription factors (72) may target UHRF1 to select genes. UHRF1 is highly expressed in many cancer cells, where it contributes to the silencing of tumor suppressor genes (37). Given the important function of tumor suppressor in restricting axon regeneration (59–63), our study suggests that in peripheral neurons UHRF1 promotes axon regeneration in part by silencing tumor suppressor genes. UHRF1 is also expressed in highly proliferative neural stem/precursor cells (73), suggesting that up-regulation of UHRF1 in injured neurons may cause them to assume a less mature state.

Consistent with this notion, we also reveal that the master regulator of the mature neuronal phenotype REST (52, 53) is transiently up-regulated following injury, suggesting its role in establishing a less mature neuronal state. Indeed, REST represses neuronal genes in nonneuronal cells as well as neural progenitors (52, 53, 69), and REST down-regulation during neuronal differentiation favors the acquisition and maintenance of the neuronal phenotype. However, REST expression remains in some part of the adult nervous system, where it has other regulatory roles in neural diseases (74–76), including neuronal death in stroke models (77), neuronal protection in aging and Alzheimer’s disease (78), and experience-dependent synaptic plasticity (79). In the adult peripheral nervous system, homeostatic levels of REST are maintained by a constitutive posttranscriptional mechanism in which the RNA-binding protein, ZFP36L2, reduces REST mRNA stability (67). In the absence of ZFP36L2, elevated REST levels lead to axon disintegration (67). REST is also elevated in models of neuropathic pain (74), where its expression is maintained for weeks after nerve injury and represses expression of voltage-gated potassium channels, neurotransmitter receptor subunits, and synaptic proteins (80–83). These studies indicate that REST regulates gene expression through repression in adult neurons and emphasize that REST levels needs to be tightly controlled. Our data provide a mechanism for a time-dependent transcriptional regulation of REST levels after axon injury, with REST expression being restricted in time by miR-9 and UHRF1. Our study suggests that a transient increase in REST allows injured neurons to enter a regenerative state and that UHRF1-dependent REST silencing prevents the adverse effects of prolonged elevated REST levels. The expression of one known REST target gene, the subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channel alpha2delta2 (84), decreases following peripheral nerve injury and pharmacological blockade of alpha2delta2 with pregabalin enhances axon regeneration (56). Our data suggest that REST also functions to activate a set of genes related to nervous system development to promote axon regeneration. Mechanistically, this could operate via Tet3, as it was shown that REST recruits Tet3 for context-specific hydroxymethylation and induction of gene expression (85). REST may thus transiently turn off the developmental switch that limits axon growth and regeneration, switching the neuron from a mature state back to a growth-competent state.

Our study, consistent with others (40), also showed that miR-9 represses axon growth and its down-regulation after injury is important for axon regeneration. miR-9 has essential roles in neural development and neuronal function, with increased expression conferring a mature neuronal fate (39). The injury-induced down-regulation of miR-9, leading to elevation in both UHRF1 and REST, is consistent with axon injury recapitulating developmental processes by switching back to a growth-competent state (5, 6).

In conclusion, our study unveils the miR-9-UHRF1-REST transcriptional network as an important regulatory mechanism promoting axon regeneration via the epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes and mature neuronal genes.

Materials and Methods

Surgeries and in Vivo Regeneration Assay.

All surgical procedures were performed under isofluorane anesthesia and approved by Washington University in St. Louis, School of Medicine Animal Studies Committee. All in vivo experiments were done using 8- to 12-wk-old C57Bl6 mice. Sciatic nerve injury experiments were performed as described (44). In vivo regeneration assay was performed as described (44) with minor modifications. We counted the number of SCG10-positive regenerating axons at multiple distances from the crush site, defined as the position along the sciatic nerve length with maximal SCG10 intensity. The cross-sectional width of the nerve was measured at the point at which the counts were taken and was used to calculate the number of axons per 100 μm of nerve width. Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

Embryonic DRG Neuron Spot Culture and in Vitro Regeneration Assay.

All embryonic culture experiments were done used CD-1–timed pregnant mice. Embryonic DRG neurons were cultured as described (44). DRG neurons were infected with lentivirus at DIV1 and axotomized at DIV7. DRG spot cultures were treated with 100 μM RG108 or DMSO (vehicle control) 10 min before axotomy; the treatment was repeated 24 h later and spot cultures were fixed 40 h after axotomy. To quantify axon regeneration, spot cultures were fixed 40 h after axotomy and stained for SCG10. Regenerative axon growth was quantified by measuring the length from the axotomy line to the axon tip and averaged from three technical replicates per biological replicate. Measurements were taken with the observer blind to treatment. Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

Adult DRG Neuron Culture and Neurite Length Analysis.

Adult DRG neurons were cultured as described (16). For quantification of average axon length, total neurite length stained by TUJ1 was measured with Neuron Image Analyzer (Nikon) and was normalized to the number of neuronal cell soma. The values are averaged from four technical replicates per biological replicate. Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

Antibodies and Lentiviruses.

Details on antibodies and lentivirus used can be found in SI Appendix.

RNA Preparations and RT-qPCR.

Total RNA from DRG spot cultures was extracted at the indicated time after axotomy using PureLink RNA mini kit (Life Technologies) or miRNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). To perform qPCR, iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix was used (Bio-Rad) with validated primer sets from PrimerBank (https://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/). Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

Bioinformatics Analyses.

For miR-9 target analysis, validated miR-9 targets were obtained from MetaCore and targets that were detected in our previous microarray (16) were used for downstream analysis in MetaCore. For REST target gene analysis, a list of 951 REST target genes was generated from ref. 55 and from validated targets from MetaCore. RNA-seq data from naïve DRG and DRG 5 d after sciatic nerve crush obtained from CAST/Ei mouse (57) were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE67130). RNA-seq data from E12.5 and E17.5 DRG neurons (56) were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE66128). Heatmap for REST target genes were generated, and DAVID was used for Gene Ontology enrichment analysis. Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

DNA Methylation Assay.

Genomic DNA was prepared from mouse embryonic DRG spot cultures using AllPrep DNA/RNA Micro Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

ChIP-qPCR Analysis.

The SimpleChIP Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit was used as described, with a few modifications, for ChIP assays. Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

Immunohistochemistry.

Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Cells were solubilized in lysis buffer and incubated with the indicated antibody overnight. Protein-G Dynabeads were added for 2 h. The beads were washed with lysis buffer and bound proteins eluted and separated by SDS/PAGE, followed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

Statistical Analysis.

All statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (v7.02). All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Detailed procedures can be found in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the V.C. laboratory members for helpful discussion and advice, Harrison Gabel for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript, and Gail Mandel for the generous gift of the REST antibody. This study was supported in part by Biogen Idec and NIH Grant NS096034 (to V.C.), a Philip and Sima K. Needleman Doctoral Fellowship (to M.M.), and a Craig H. Neilsen postdoctoral fellowship (to E.E.E.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1812518115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fagoe ND, van Heest J, Verhaagen J. Spinal cord injury and the neuron-intrinsic regeneration-associated gene program. Neuromolecular Med. 2014;16:799–813. doi: 10.1007/s12017-014-8329-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindner R, Puttagunta R, Di Giovanni S. Epigenetic regulation of axon outgrowth and regeneration in CNS injury: The first steps forward. Neurotherapeutics. 2013;10:771–781. doi: 10.1007/s13311-013-0203-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahar M, Cavalli V. Intrinsic mechanisms of neuronal axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018;19:323–337. doi: 10.1038/s41583-018-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He Z, Jin Y. Intrinsic control of axon regeneration. Neuron. 2016;90:437–451. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan A, Bueno M, Hua L, Fournier AE. Maximizing functional axon repair in the injured central nervous system: Lessons from neuronal development. Dev Dyn. 2017;247:18–23. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quadrato G, Di Giovanni S. Waking up the sleepers: Shared transcriptional pathways in axonal regeneration and neurogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:993–1007. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1099-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weng YL, Joseph J, An R, Song H, Ming GL. Epigenetic regulation of axonal regenerative capacity. Epigenomics. 2016;8:1429–1442. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradke F, Fawcett JW, Spira ME. Assembly of a new growth cone after axotomy: The precursor to axon regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:183–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Giovanni S. Molecular targets for axon regeneration: Focus on the intrinsic pathways. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2009;13:1387–1398. doi: 10.1517/14728220903307517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu K, Tedeschi A, Park KK, He Z. Neuronal intrinsic mechanisms of axon regeneration. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:131–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rishal I, Fainzilber M. Axon-soma communication in neuronal injury. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrn3609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackmore MG. Molecular control of axon growth: Insights from comparative gene profiling and high-throughput screening. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2012;105:39–70. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-398309-1.00004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma TC, Willis DE. What makes a RAG regeneration associated? Front Mol Neurosci. 2015;8:43. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chandran V, et al. A systems-level analysis of the peripheral nerve intrinsic axonal growth program. Neuron. 2016;89:956–970. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkatesh I, Blackmore MG. Selecting optimal combinations of transcription factors to promote axon regeneration: Why mechanisms matter. Neurosci Lett. 2016;652:64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho Y, Sloutsky R, Naegle KM, Cavalli V. Injury-induced HDAC5 nuclear export is essential for axon regeneration. Cell. 2013;155:894–908. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finelli MJ, Wong JK, Zou H. Epigenetic regulation of sensory axon regeneration after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2013;33:19664–19676. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0589-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaub P, et al. The histone acetyltransferase p300 promotes intrinsic axonal regeneration. Brain. 2011;134:2134–2148. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puttagunta R, et al. PCAF-dependent epigenetic changes promote axonal regeneration in the central nervous system. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3527. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weng YL, et al. An intrinsic epigenetic barrier for functional axon regeneration. Neuron. 2017;94:337–346. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loh YE, et al. Comprehensive mapping of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine epigenetic dynamics in axon regeneration. Epigenetics. 2017;12:77–92. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1264560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith ZD, Meissner A. DNA methylation: Roles in mammalian development. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:204–220. doi: 10.1038/nrg3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deaton AM, Bird A. CpG islands and the regulation of transcription. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1010–1022. doi: 10.1101/gad.2037511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore LD, Le T, Fan G. DNA methylation and its basic function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:23–38. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garriga J, et al. Nerve injury-induced chronic pain is associated with persistent DNA methylation reprogramming in dorsal root ganglion. J Neurosci. 2018;38:6090–6101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2616-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iskandar BJ, et al. Folate regulation of axonal regeneration in the rodent central nervous system through DNA methylation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1603–1616. doi: 10.1172/JCI40000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gräff J, Kim D, Dobbin MM, Tsai LH. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression in physiological and pathological brain processes. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:603–649. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yao B, et al. Epigenetic mechanisms in neurogenesis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:537–549. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fatemi M, Hermann A, Gowher H, Jeltsch A. Dnmt3a and Dnmt1 functionally cooperate during de novo methylation of DNA. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:4981–4984. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z, Tang B, He Y, Jin P. DNA methylation dynamics in neurogenesis. Epigenomics. 2016;8:401–414. doi: 10.2217/epi.15.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meilinger D, et al. Np95 interacts with de novo DNA methyltransferases, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b, and mediates epigenetic silencing of the viral CMV promoter in embryonic stem cells. EMBO Rep. 2009;10:1259–1264. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, et al. UHRF1 targets DNMT1 for DNA methylation through cooperative binding of hemi-methylated DNA and methylated H3K9. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1563. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkyurek AC, et al. The DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 directly interacts with the SET and RING finger-associated (SRA) domain of the multifunctional protein Uhrf1 to facilitate accession of the catalytic center to hemi-methylated DNA. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:379–386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.523209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arita K, Ariyoshi M, Tochio H, Nakamura Y, Shirakawa M. Recognition of hemi-methylated DNA by the SRA protein UHRF1 by a base-flipping mechanism. Nature. 2008;455:818–821. doi: 10.1038/nature07249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nishiyama A, et al. Uhrf1-dependent H3K23 ubiquitylation couples maintenance DNA methylation and replication. Nature. 2013;502:249–253. doi: 10.1038/nature12488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arita K, et al. Recognition of modification status on a histone H3 tail by linked histone reader modules of the epigenetic regulator UHRF1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:12950–12955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203701109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bronner C, Krifa M, Mousli M. Increasing role of UHRF1 in the reading and inheritance of the epigenetic code as well as in tumorogenesis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86:1643–1649. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramesh V, et al. Loss of Uhrf1 in neural stem cells leads to activation of retroviral elements and delayed neurodegeneration. Genes Dev. 2016;30:2199–2212. doi: 10.1101/gad.284992.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun AX, Crabtree GR, Yoo AS. MicroRNAs: Regulators of neuronal fate. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2013;25:215–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang J, et al. MicroRNA-9 regulates mammalian axon regeneration in peripheral nerve injury. Mol Pain. 2017;13:1744806917711612. doi: 10.1177/1744806917711612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller CA, et al. Cortical DNA methylation maintains remote memory. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:664–666. doi: 10.1038/nn.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LaPlant Q, et al. Dnmt3a regulates emotional behavior and spine plasticity in the nucleus accumbens. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1137–1143. doi: 10.1038/nn.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith DS, Skene JH. A transcription-dependent switch controls competence of adult neurons for distinct modes of axon growth. J Neurosci. 1997;17:646–658. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00646.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cho Y, Cavalli V. HDAC5 is a novel injury-regulated tubulin deacetylase controlling axon regeneration. EMBO J. 2012;31:3063–3078. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cho Y, et al. Activating injury-responsive genes with hypoxia enhances axon regeneration through neuronal HIF-1α. Neuron. 2015;88:720–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin JE, Geisler S, DiAntonio A. Dynamic regulation of SCG10 in regenerating axons after injury. Exp Neurol. 2014;252:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu M, Xu Y, Ge M, Gui Z, Yan F. Regulation of UHRF1 by microRNA-9 modulates colorectal cancer cell proliferation and apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:833–839. doi: 10.1111/cas.12689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dajas-Bailador F, et al. microRNA-9 regulates axon extension and branching by targeting Map1b in mouse cortical neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:697–699. doi: 10.1038/nn.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jonas S, Izaurralde E. Towards a molecular understanding of microRNA-mediated gene silencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:421–433. doi: 10.1038/nrg3965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giusti SA, et al. MicroRNA-9 controls dendritic development by targeting REST. eLife. 2014;3:e02755. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Packer AN, Xing Y, Harper SQ, Jones L, Davidson BL. The bifunctional microRNA miR-9/miR-9* regulates REST and CoREST and is downregulated in Huntington’s disease. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14341–14346. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2390-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chong JA, et al. REST: A mammalian silencer protein that restricts sodium channel gene expression to neurons. Cell. 1995;80:949–957. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schoenherr CJ, Anderson DJ. The neuron-restrictive silencer factor (NRSF): A coordinate repressor of multiple neuron-specific genes. Science. 1995;267:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.7871435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Michaelevski I, et al. Signaling to transcription networks in the neuronal retrograde injury response. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra53. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Johnson DS, Mortazavi A, Myers RM, Wold B. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science. 2007;316:1497–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1141319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tedeschi A, et al. The calcium channel subunit alpha2delta2 suppresses axon regeneration in the adult CNS. Neuron. 2016;92:419–434. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lisi V, et al. Enhanced neuronal regeneration in the CAST/Ei mouse strain is linked to expression of differentiation markers after injury. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rothbart SB, et al. Association of UHRF1 with methylated H3K9 directs the maintenance of DNA methylation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:1155–1160. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krishnan A, Duraikannu A, Zochodne DW. Releasing ‘brakes’ to nerve regeneration: Intrinsic molecular targets. Eur J Neurosci. 2016;43:297–308. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park KK, et al. Promoting axon regeneration in the adult CNS by modulation of the PTEN/mTOR pathway. Science. 2008;322:963–966. doi: 10.1126/science.1161566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abe N, Borson SH, Gambello MJ, Wang F, Cavalli V. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) activation increases axonal growth capacity of injured peripheral nerves. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28034–28043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.125336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu K, et al. PTEN deletion enhances the regenerative ability of adult corticospinal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1075–1081. doi: 10.1038/nn.2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Christie KJ, Webber CA, Martinez JA, Singh B, Zochodne DW. PTEN inhibition to facilitate intrinsic regenerative outgrowth of adult peripheral axons. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9306–9315. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6271-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gallaher ZR, Steward O. Modest enhancement of sensory axon regeneration in the sciatic nerve with conditional co-deletion of PTEN and SOCS3 in the dorsal root ganglia of adult mice. Exp Neurol. 2018;303:120–133. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2018.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim JK, Estève PO, Jacobsen SE, Pradhan S. UHRF1 binds G9a and participates in p21 transcriptional regulation in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:493–505. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Obata Y, et al. The epigenetic regulator Uhrf1 facilitates the proliferation and maturation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:571–579. doi: 10.1038/ni.2886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cargnin F, et al. An RNA binding protein promotes axonal integrity in peripheral neurons by destabilizing REST. J Neurosci. 2014;34:16650–16661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1650-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kreisler A, et al. Regulation of the NRSF/REST gene by methylation and CREB affects the cellular phenotype of small-cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29:5828–5838. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ballas N, Grunseich C, Lu DD, Speh JC, Mandel G. REST and its corepressors mediate plasticity of neuronal gene chromatin throughout neurogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:645–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pannese E. Number and structure of perisomatic satellite cells of spinal ganglia under normal conditions or during axon regeneration and neuronal hypertrophy. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat. 1964;63:568–592. doi: 10.1007/BF00339491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Niemi JP, et al. A critical role for macrophages near axotomized neuronal cell bodies in stimulating nerve regeneration. J Neurosci. 2013;33:16236–16248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3319-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hervouet E, Vallette FM, Cartron PF. Dnmt3/transcription factor interactions as crucial players in targeted DNA methylation. Epigenetics. 2009;4:487–499. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.7.9883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Murao N, et al. Characterization of Np95 expression in mouse brain from embryo to adult: A novel marker for proliferating neural stem/precursor cells. Neurogenesis (Austin) 2014;1:e976026. doi: 10.4161/23262133.2014.976026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Willis DE, Wang M, Brown E, Fones L, Cave JW. Selective repression of gene expression in neuropathic pain by the neuron-restrictive silencing factor/repressor element-1 silencing transcription (NRSF/REST) Neurosci Lett. 2016;625:20–25. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Song Z, Zhao D, Zhao H, Yang L. NRSF: An angel or a devil in neurogenesis and neurological diseases. J Mol Neurosci. 2015;56:131–144. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0474-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hwang JY, Zukin RS. REST, a master transcriptional regulator in neurodegenerative disease. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2018;48:193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Calderone A, et al. Ischemic insults derepress the gene silencer REST in neurons destined to die. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2112–2121. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-06-02112.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lu T, et al. REST and stress resistance in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2014;507:448–454. doi: 10.1038/nature13163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rodenas-Ruano A, Chávez AE, Cossio MJ, Castillo PE, Zukin RS. REST-dependent epigenetic remodeling promotes the developmental switch in synaptic NMDA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1382–1390. doi: 10.1038/nn.3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rose K, et al. Transcriptional repression of the M channel subunit Kv7.2 in chronic nerve injury. Pain. 2011;152:742–754. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Uchida H, Ma L, Ueda H. Epigenetic gene silencing underlies C-fiber dysfunctions in neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2010;30:4806–4814. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5541-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Uchida H, Sasaki K, Ma L, Ueda H. Neuron-restrictive silencer factor causes epigenetic silencing of Kv4.3 gene after peripheral nerve injury. Neuroscience. 2010;166:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Perkins JR, et al. A comparison of RNA-seq and exon arrays for whole genome transcription profiling of the L5 spinal nerve transection model of neuropathic pain in the rat. Mol Pain. 2014;10:7. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-10-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Shimojo M, Shudo Y, Ikeda M, Kobashi T, Ito S. The small cell lung cancer-specific isoform of RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST) is regulated by neural-specific Ser/Arg repeat-related protein of 100 kDa (nSR100) Mol Cancer Res. 2013;11:1258–1268. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Perera A, et al. TET3 is recruited by REST for context-specific hydroxymethylation and induction of gene expression. Cell Rep. 2015;11:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.