Abstract

Aim

Several biomarkers have been proposed to detect pancreatic β cell destruction in vivo but so far have not been compared for sensitivity and significance.

Methods

We used islet transplantation as a model to compare plasma concentrations of miR-375, 65-kDa subunit of glutamate decarboxylase (GAD65), and unmethylated insulin DNA, measured at subpicomolar sensitivity, and study their discharge kinetics, power for outcome prediction, and detection of graft loss during follow-up.

Results

At 60 minutes after transplantation, GAD65 and miR-375 consistently showed near-equimolar and correlated increases proportional to the number of implanted β cells. GAD65 and miR-375 showed comparable power to predict poor graft outcome at 2 months, with areas under the curve of 0.833 and 0.771, respectively (P = 0.53). Using receiver operating characteristic analysis, we defined likelihood ratios (LRs) for rationally selected result intervals. In GADA-negative recipients (n = 28), GAD65 <4.5 pmol/L (LR = 0.15) and >12.2 pmol/L (LR = ∞) predicted good and poor outcomes, respectively. miR-375 could be used in all recipients irrespective of GAD65 autoantibody status (n = 46), with levels <1.4 pmol/L (LR = 0.14) or >7.6 pmol/L (LR = 9.53) as dual thresholds. The posttransplant surge of unmethylated insulin DNA was inconsistent and unrelated to outcome. Combined measurement of these three biomarkers was also tested as liquid biopsy for β cell death during 2-month follow-up; incidental surges of GAD65, miR-375, and (un)methylated insulin DNA, alone or combined, were confidently detected but could not be related to outcome.

Conclusions

GAD65 and miR-375 performed equally well in quantifying early graft destruction and predicting graft outcome, outperforming unmethylated insulin DNA.

The diagnostic potential to detect occult β cell loss in both the acute and chronic phases after islet transplantation was compared for three chemically distinct β cell selective biomarkers.

The timing and the progression of immune-mediated β cell destruction in type 1 diabetes (T1D) are poorly understood and largely derived from late and indirect indicators such as loss of insulin secretory capacity or escalation of autoimmunity. Real-time detection of β cell destruction is possible through the measurement of β cell‒selective biomarkers released into the circulation. Various candidate biomarkers were recently proposed, ranging from nonspecific proteins such as the damage-associated high-mobility group nox 1 (1, 2) to β cell‒selective molecules such as the 65-kDa subunit of glutamate decarboxylase (GAD65) (3), insulin mRNA (4), unmethylated insulin (U INS) DNA (5–7), and miR-375 (8–12). We previously showed that GAD65 can be used to identify excessive early β cell destruction early after implantation as a predictor for graft failure (3). The main limitation of GAD65 is that its use is limited to the minority of patients with T1D without GAD65 autoantibodies (GADAs), interfering in most immunoassays. Recent progress involved the identification of U INS DNA, usually expressed as a ratio over ubiquitous methylated insulin (M INS) DNA, as a biomarker of β cell loss in animal models (5) in patients after islet transplantation and in pre-onset and recent-onset T1D (6, 7). Equally interesting is β cell‒enriched miR-375, which was independently confirmed as a biomarker of β cell death in vitro (10, 11) in streptozotocin-injected and nonobese diabetic mice (10) and after intraportal islet infusion in humans (11). Nucleic acid‒type biomarkers are generally considered superior in terms of sensitivity because of the amplification power of PCR. However, a direct and in-depth comparison of GAD65, unmethylated insulin DNA, and miR-375 has not been performed, and in most studies the correlation between the biomarker levels and extent of β cell destruction was not reported. A second limitation is that most reported tests for U INS DNA and miR-375 suffer from a lack of analytical standardization, the use of normalized levels instead of absolute quantification, and the interpretative difficulty raised by measurable baseline levels in healthy controls (7, 10, 11).

Here, we report the direct comparison of three chemically distinct biomarkers, all absolutely quantified using high-sensitivity assays achieving subpicomolar sensitivity. GAD65 was measured using a recently developed flow cytometry‒based immunoassay (13); for miR-375, we developed a hydrolysis-probe PCR achieving subpicomolar sensitivity through miRNA sequence-specific capture. Absolute copy numbers of plasma U INS and M INS DNA were quantified using a previously published assay (7, 14). These biomarkers were compared in a standardized model of β cell injury: the intraportal implantation of islet grafts (15) to (i) investigate the relative kinetics of biomarker discharge in the acute posttransplantation period; (ii) correlate graft injury reflected by GAD65, miR-375, and U INS to transplantation outcome; and (iii) conduct a pilot study to investigate whether our optimized GAD65, miR-375, and U INS assays achieved sufficient sensitivity to detect instances of low-grade β cell death in the weeks after islet cell transplantation.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of β cells and β cell grafts

Islet preparations from individual donors were cultured for maximally 4 weeks in serum-free Ham F-10 (Gibco, Loughborough, United Kingdom), typically using pooled islet grafts from multiple donors (15, 16).

T1D graft recipients

These studies were approved by our institutional ethics committee (protocol NCT00623610; ethical approval 98/059D). The current study reports on 74 intraportal transplant events in 39 nonuremic patients with C-peptide‒negative T1D who received islet cell grafts under anti-thymocyte globulin, mycophenolate mofetil, and tacrolimus (15, 17–19) (Fig. 1). Patients received grafts containing 0.5 to 6.0⋅106β cells/kg of body weight. GAD65 analysis was restricted to transplant events (n = 52) in patients without interfering GADA titers [<45 World Health Organization (WHO) U/mL]. miR-375 was also quantified in transplant events (n = 22) with interfering GADA. Correlation of 1-hour posttransplant biomarker levels to graft outcome at 2 months after transplantation was restricted to transplant events with at least 2.0⋅106β cells/kg of body weight because this was found to be the minimally required β cell mass to achieve glycemic normalization (15). GAD65 was thus analyzed in n = 28 events in recipients without interfering GADAs, and miR-375 was analyzed in an additional n = 18 events in recipients with interfering GADAs (n = 46 total) (please see overview of patient groups in Fig. 1 and all data provided in Supplemental Data 1).

Figure 1.

Different subgroups analyzed for miR-375, GAD65, and U INS DNA levels. In total, n = 74 islet cell transplantations were examined in 39 C-peptide‒negative patients with type 1 diabetes. GAD65 was studied only in patients with GADA titers <45 WHO U/mL before islet infusion. In patients who received ≥2 million β cells/kg of body weight, the association of all three biomarkers with the C-peptide increment after 2 mo was further investigated.

In total, 14 patients received two β cell grafts. A repeated implantation was treated as an independent event, as grafts were isolated from different donor organs, and outcome measurement of a second graft was analyzed as the C-peptide increment over the pretransplant level and before an eventual subsequent implantation in recipients who received a second graft. C-peptide increment was calculated by subtracting the median C-peptide level measured in the pretransplant day −20 to −1 period from the median C-peptide level in the posttransplant day 40 to 90 period (further referred to as outcome at 2 months after transplantation) before an eventual subsequent implantation (3). Only C-peptide levels measured at glycemia between 5.55 and 12.21 mmol/L were used. The median sample number was 3 (interquartile range: 2, 4) in the posttransplant period and 1 (interquartile range: 1, 2) in the pretransplant period. The kinetic analysis of GAD65, miR-375, and U/M INS was done for a sample cohort including all transplant events (n = 12) in recipients without interfering GADAs for whom samples were available at the indicated time points.

GAD65, miR-375, U/M INS, and human C-peptide assay

Blood samples were collected in K3-EDTA tubes (Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) supplemented with 1% of a 0.12-mg/mL solution of aprotinin (Stago, Asnières-sur-Seine, France) in 0.9% NaCl. Plasma was stored at −80°C after centrifugation for 15 minutes at 1600g. The limits of detection (LoDs) and limits of quantification (LoQs) for GAD65, miR-375, and U/M INS were determined as the mean of the blank (nondiabetic healthy volunteers) summed with three times and eight times the SD of the blank, respectively. GAD65 was detected with a cytometric bead array (CBA) as described (13), with LoD (LoQ) = 0.121 (0.288) pmol/L and negative interference by GADA titers ≥45 WHO U/mL (Supplemental Fig. 1). GADA was determined by a liquid-phase radio-binding assay with a diagnostic sensitivity of 74% and a specificity of 97% in the Diabetes Antibodies Standardization Program 2009 workshop and has a diagnostic cutoff (P99) of 23 WHO U/mL and between-day coefficients of variation (CVs) in the decision zone of 10%. miR-375 was quantified using a synthetic miR-375 duplex, supplemented to a plasma/serum pool (K3-EDTA Pooled Normal Human Plasma/Serum; Innovative Research) for generation of an miR-375 standard curve. miR-375 was measured after capture by hybridization using Taqman miRNA ABC Purification Kit Human Panel A (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described (20), with LoD (LoQ) = 0.049 (0.102) pmol/L. For selected experiments, silica column-based extraction (miRNeasy Serum/Plasma Kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used. U INS and M INS were determined by quantifying the methylation status of cytosine at position −69 bp by droplet digital PCR using a dual fluorescent probe‒based multiplex assay as described with a reported LoD (LoQ) of 3.217 (7.098) copies/µL for U INS and 2.267 (5.105) copies/µL for M INS (7, 14). Human C-peptide was measured with a time-resolved fluorescence immunoassay kit (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) adapted to an AutoDelfia automate (PerkinElmer) in random nonfasted blood sampled weekly during the first 6 weeks after transplant and every 2 weeks between posttransplant weeks 6 and 12.

Statistical analysis

Prism 5.00 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) was used for the Mann-Whitney U test, Spearman correlation test, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis with calculation of likelihood ratios (LRs). Half-lives were calculated according to Yu et al. (21), starting from the peak biomarker value in every patient. Area under the curve (AUC) of ROC curves was compared according to DeLong et al. (22).

Results

Increased sensitivity of miR-375 quantitative reverse transcription PCR assay through sequence-specific capture

The miR-375 assay was analytically optimized by replacing conventional silica column-based total RNA extraction with sequence-specific capture using magnetic beads functionalized with antisense nucleotides; in healthy control pooled samples spiked with logarithmically ascending concentrations of synthetic miR-375, this lowered the signal/noise ratio from 1.57 pmol/L (Fig. 2A, filled circles) to 0.07 pmol/L in serum (Fig. 2A, open circles) and 0.15 pmol/L in plasma (Fig. 2B), with no miR-375 amplification (Cq = 40) in samples without exogenously added miR-375. To allow absolute quantification, a standard curve of synthetic miR-375 was included in every assay from extraction onward; over a total of n = 17 different assays, this calibration curve showed good linearity (R2 = 0.908) and repeatability (CV%; Fig. 2C). This assay was then used to analyze baseline miR-375 levels in n = 28 pretransplant patients with T1D and in n = 50 autoantibody-negative healthy controls. All miR-375 concentrations before transplantation were below the LoQ. In healthy individuals, miR-375 baseline levels detected were miR-375 above LoD (7/50) and even above LoQ (4/50) (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Design and key analytical properties of the miR-375 PCR assay. (A) Assay design: Synthetic miR-375 duplex was added to a denatured serum pool, and miR-375 was captured by sequence-specific hybridization using magnetic beads. miR-375 sequence-specific pull-down extraction (open circles) resulted in ≥10 times lower baseline amplifications (signal/noise ratio = 3; dashed line) compared with nonsequence-specific silica column-based total RNA extraction (filled circles). (B) Similar results were obtained in plasma matrix. (A and B) Descending and horizontal filled lines represent linear trend lines (R2 ≥ 0.980) and average baseline signals, respectively. (C) A standard curve was established by adding a synthetic miR-375 duplex in a denatured plasma pool of control subjects that showed no detectable baseline signal (Cq = 40). The calibration curve showed excellent linearity (R2 = 0.908) and good repeatability, as shown by CV% over n = 17 independent assays. (A‒C) x-Axes are shown in logarithmic scale. (D) Baseline miR-375 concentrations (mean ± SD) before transplantation (pre-Tx, n = 28, plasma) and in healthy controls (n = 50, serum). Dashed lines represent the LoD and LoQ of the miR-375 assay. Tx, transplantation.

Comparison of miR-375, GAD65, and U/M INS discharge kinetics in the early posttransplant phase

First, we compared the kinetics of GAD65, miR-375, and (U/M INS release (Fig. 3A‒3L) in a cohort including all 12 transplantations performed in GADA-negative recipients for whom the indicated time points were available; all miR-375 and GAD65 levels were below the LoD before islet infusion and above the LoQ after. This was not the case for U INS; two of 12 patients showed detectable U INS before transplantation, and three of 12 failed to show detectable U INS after. U INS reached LoQ at some time point after implantation in only one of 12 transplant events. Surprisingly, the ubiquitous M INS showed a consistent rise after transplantation, above LoQ in nine of 12 events. Average time to peak was identical for GAD65 and miR-375 (24 and 25 minutes, respectively), whereas U INS tended to peak later (49 minutes). After peak level, GAD65 and miR-375 decreased according to an exponential decay pattern (Fig. 3M and 3N). GAD65 clearance occurred in one phase, with a calculated half-life of 3.7 hours. miR-375 showed a biphasic pattern: an initial rapid phase with mean half-life of ∼36 minutes followed by a subsequent slow phase with mean half-life of ∼5.6 hours. For U INS, linear regression analysis of the logarithmic transformed biomarker levels was not significant because of the low number of events above LoD/LoQ.

Figure 3.

Combinatorial profiling of GAD65, miR-375, and U INS DNA kinetics after intraportal islet transplantation. (A‒L) Plasma GAD65 (solid blue lines), miR-375 (solid green lines), U INS (solid red lines), and M INS (dashed red lines) were measured before and 5, 15, 30, 60, 120, and 240 min after n = 12 of 52 intraportal islet cell infusions, with variable total numbers of implanted β cells expressed as million β cells/kg of body weight: (A) 0.68; (B) 0.69; (C) 0.77; (D) 0.88; (E) 1.58; (F) 1.87; (G) 2.01; (H) 2.23; (I) 2.86; (J) 3.17; (K) 3.30; and (L) 5.30 million β cells/kg of body weight. LoD is indicated as dashed horizontal blue and green lines for GAD65 and miR-375, respectively (left y-axis). LoD is indicated as solid and dashed horizontal red lines for U INS and M INS, respectively (right y-axis). Both y-axes are shown in logarithmic scale. (M and N) The average relative (M) GAD65 and (N) miR-375 levels are shown for the 12 patients (±SD: dashed lines) shown in (A‒L). Each biomarker is represented as percentage from the peak biomarker value. Also, time is shown relative to peak value. (M) For GAD65, one-phase kinetics gave the best fit (R2 = 0.93; P < 0.0001). (N) The clearance kinetics of miR-375 were biphasic (R2 = 0.99; P = 0.0002 for first phase and R2 = 0.57; P = 0.0043 for second phase). (M and N) The y-axis is shown in logarithmic scale (natural logarithm). Solid green and blue lines: linear regression; dashed lines: 95% CI. Clearance of U/M INS was not shown because of insufficient data points above LoQ. Tx, transplantation.

Description of patient cohorts and data analysis strategy

Because GADAs interfere with GAD65 quantification, we first directly compared GAD65, miR-375, and U/M INS levels in n = 52 transplant events in patients without interfering GADAs (<45 WHO U/mL) (Fig. 1). We additionally measured miR-375 and U/M INS in a second cohort with interfering GADAs (n = 22 events). We then analyzed whether biomarker levels at 1 hour after transplantation were predictive for graft function 2 months later. This outcome analysis was restricted to transplant events with minimally 2.0⋅106β cells/kg of body weight, as this is the graft size typically required to achieve a C-peptide threshold corresponding to a metabolically adequate implant, defined here as good outcome [plasma C-peptide >0.166 nmol/L at posttransplant month 2 (15)].

Outcome prediction using GAD65

In all 52 transplant events without interfering GADA, GAD65 levels were below LoQ before and above LoQ at 60 minutes after implantation. Outcome analysis was possible in 28 transplant events with ≥2 million β cells/kg of body weight (Fig. 1); poor outcome (9 of 28; 32% prevalence) was associated with significantly higher median GAD65 (12.3 vs 2.6 pmol/L; P = 0.005) (Fig. 4A and 4C). ROC analysis indicated significant (P = 0.005) diagnostic power (AUC = 0.833; 95% CI: 0.648, 1.018) (Fig. 4B), allowing the selection of diagnostic thresholds guided by relevant LRs (Supplemental Data 2). Events with GAD65 >12.2 pmol/L (n = 5) invariably resulted in poor outcome (posttest probability, 100%; Fig. 4D), whereas all but one (13 of 14) event with a GAD65 <4.5 pmol/L (n = 14) showed a good outcome (LR, 0.15l; posttest probability, 7%). GAD65 between 4.5 and 12.2 pmol/L corresponded to a gray zone in which the test had limited diagnostic utility. Using this dual threshold, the GAD65 test showed diagnostic utility in 71% of events, either to confidently predict or rule out poor outcome. In n = 9 patients who received two independent grafts, only one patient showed GAD65 >12.2 pmol/L in both transplantations (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 4.

Diagnostic power of GAD65 and miR-375 1 h after transplantation to late-stage graft function. Poor outcome was defined as C-peptide increment ≤1.66 nmol/L (0.5 ng/mL). (A‒D) Panels show the predictive value of GAD65 (squares) at 60 min in 28 transplant events with ≥2.0⋅106β cells/kg of body weight in GADA-negative recipients. (E‒H) Panels show miR-375 data (triangles) in all 46 transplant events with ≥2.0⋅106β cells/kg of body weight irrespective of GADA status. (A and E) C-peptide increment at 2 mo after transplantation vs biomarker level at 60 min. Horizontal dashed lines show a C-peptide increment of 0.166 nmol/L. (B and F) ROC analysis, AUC, and P-value are shown. (C and G) Dual thresholding and indication of gray zone are based on LRs (Supplemental Data 2). Good and bad outcomes were defined as C-peptide increment >0.166 nmol/L and ≤0.166 nmol/L, respectively. **P < 0.01; median with interquartile range. (D and H) Diagnostic power of both biomarkers is expressed by the shift from pretest to posttest probability. Filled and empty symbols indicate posttest probability of poor outcome for biomarker above upper threshold or below lower threshold, respectively. Ppost, posttest probability; Ppre pretest probability; Tx, transplantation.

Outcome prediction using miR-375

miR-375 levels were below LoQ before and above LoQ after implantation in all 74 transplant events. Outcome analysis was done in all 46 events with ≥2.0⋅106β cells/kg of body weight, including 28 without and 18 with interfering GADAs (Fig. 1). Poor outcome (11 of 46; prevalence, 24%) was associated with significantly higher median miR-375 (2.1 vs 1.0 pmol/L; P = 0.007) (Fig. 4E and 4G). ROC analysis indicated significant (P = 0.007) diagnostic power (AUC = 0.771; 95% CI: 0.631, 0.912) (Fig. 4F). AUC of miR-375 and GAD65 did not differ significantly (P = 0.53). Also for miR-375, a dual threshold model was selected guided by LRs (Supplemental Data 2); miR-375 >7.6 pmol/L was associated with poor outcome (Fig. 4H) in three of four events (LR = 9.5; posttest probability, 75%), whereas miR-375 <1.4 pmol/L resulted in good outcomes in 22 of 23 such cases (LR = 0.14; posttest probability, 4%). An miR-375 between 1.4 and 7.6 pmol/L (19 of 46 events) had limited diagnostic utility. Using this dual threshold, the miR-375 test showed diagnostic utility in 59% of events, either to confidently predict or rule out a poor outcome. In n = 14 patients who received two independent grafts, no patient showed miR-375 value >7.6 pmol/L in both transplantations (Supplemental Table 1).

Inferior performance of U INS

U INS and M INS were detected in only 14% and 41% of all posttransplant samples, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 2), indicating inferior performance of this test in our cohort compared with previous studies (7, 14). Neither U INS nor M INS correlated significantly with β cell number or graft C-peptide content (Table 1). Only four events with detectable U INS (above LoD) were grafts for which patients received ≥2.0⋅106β cells/kg of body weight and could thus be related to functional graft outcome; two of four evolved to poor outcome (≤0.166 nmol/L), but these two transplants also showed elevated miR-375 >1.4 pmol/L and GAD65 >4.5 pmol/L, indicating no added value of U INS detection in this setting.

Table 1.

Correlation Matrix of Biomarkers for β Cell Destruction, Amount of β Cells in Graft, C-Peptide Content in Graft, and Graft Function After 2 Months

| GAD65 | miR-375 | U INS | M INS | β Cells | C-Peptide Graft | Δ C-Peptidea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAD65 | |||||||

| rS | 0.845 | ND | 0.255 | 0.502 | 0.605 | −0.517 | |

| P | <0.001 | ND | 0.470 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 | |

| N | 52 | ND | 10 | 52 | 52 | 28 | |

| miR-375 | |||||||

| rS | 0.845 | ND | 0.136 | 0.399 | 0.570 | −0.363 | |

| P | <0.001 | ND | 0.629 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.013 | |

| N | 52 | ND | 15 | 74 | 74 | 46 | |

| U INS | |||||||

| rS | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| P | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| N | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| M INS | |||||||

| rS | 0.255 | 0.136 | ND | −0.429 | −0.311 | −0.818 | |

| P | 0.470 | 0.629 | ND | 0.111 | 0.259 | 0.006 | |

| N | 10 | 15 | ND | 15 | 15 | 10 |

GAD65 and miR-375 are shown in pmol/L, U/M INS in copies/µL, β cells in 106/kg of body weight, and C-peptide content in graft in nmol/kg of body weight; Δ C-peptide is the C-peptide increment 2 mo after transplantation (nmol/L). Boldface text indicates P < 0.05. All statistical tests were performed for biomarker levels above LoQ. For GAD65, the subgroup with GADA titers <45 WHO U/mL was selected.

Abbreviations: ND, analysis was not done for U INS (n = 1 transplantation where the concentration was > LoQ); rS, Spearman correlation coefficient.

Subgroup that received ≥2.0⋅106β cells/kg of body weight.

Combinatorial profiling of GAD65, miR-375, and U INS to detect late-stage β cell injury

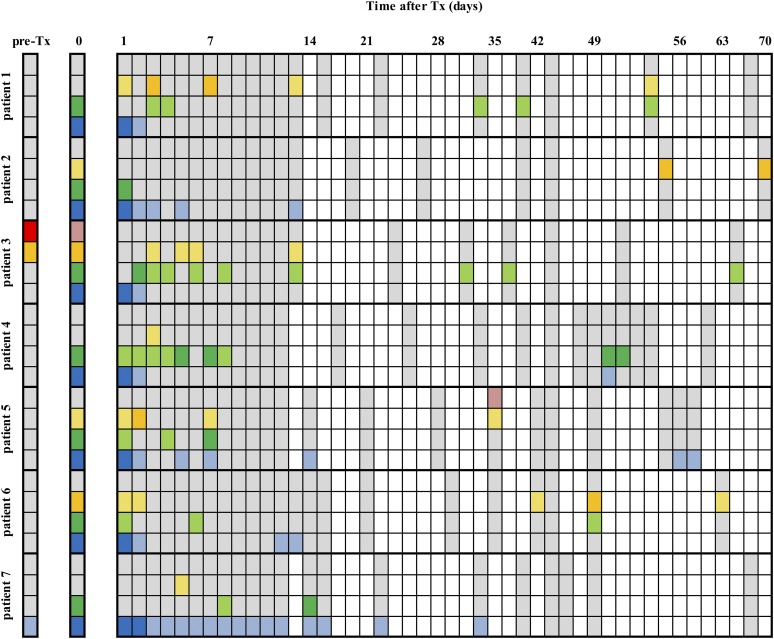

Finally, we investigated whether the optimized sensitivity of our assays allowed the detection of incidental β cell death beyond the acute posttransplant phase. We conducted a pilot study in n = 7 patients who received ≥2.0⋅106β cells/kg of body weight and were repetitively sampled for combinatorial analysis of GAD65, miR-375, and U/M INS. The primary objective was a qualitative investigation showing confident absence or presence of these biomarkers, defined as concentrations above LoD (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Combinatorial profiling of GAD65, miR-375, and U INS and M INS DNA to detect late-stage immune-mediated β cell injury after islet transplantation. Seven patients were frequently sampled during the first 70 d after transplantation. All three biomarkers were measured in the same plasma samples at the indicated time points after transplantation (Tx). Pre-Tx represents the biomarker levels before graft infusion, and day 0 indicates the levels 60 minutes after graft infusion. White boxes indicate that no blood was taken; gray boxes mean that samples were available and were determined for the respective biomarkers but indicate that biomarker concentrations were below the respective assay’s LoD. GAD65 is shown in blue, miR-375 in green, U INS DNA in red, and M INS DNA in yellow. Biomarker levels above the LoD are shown in light colors, whereas dark colors represent levels above the respective assay’s LoQ. All patients received a single intraportal infusion of ≥2 million β cells/kg of body weight.

After transplantation, GAD65 and miR-375 surges were detected in all seven patients (Fig. 5): (i) GAD65 but not miR-375 was detectable in all patients 24 hours after islet infusion; (ii) beyond day 2, multiple miR-375 surges above LoD were detected in six of seven patients and GAD65 above LoD was detected in five of seven patients; and (iii) the GAD65 or miR-375 surges were mostly subtle (i.e., beyond day 2, GAD65 remained below LoQ in all patients, whereas miR-375 was above LoQ in three of seven patients). The frequency of sampling was insufficient to allow a detailed kinetic analysis or to correlate either frequency or amplitude of surges with graft function around month 2. U INS was detected in one patient (Fig. 5), together with a coincidental surge of M INS but not miR-375 or GAD65. M INS above LoD was found in all seven patients, whereas M INS was above LoQ in four patients.

Discussion

Ultrasensitive detection of β cell‒derived molecules in the circulation is the only direct way to document occult β cell destruction in vivo. Considering the limited size of the endogenous β cell mass, the assumption that at any given moment only a small fraction of β cells undergoes primary or secondary necrosis and the largely unknown timing of immune-mediated β cell death, detection of circulating β cell‒derived biomarkers is extremely challenging. Various candidate biomarkers were proposed by us [GAD65, PPP1R1A (23), UCHL1 (24)] and others (miR-375, U INS) and separately tested in proof-of-concept studies. This study presents a direct comparison of three chemically distinct biomarkers.

The strengths of our study were (i) the use of a standardized model with islet grafts characterized for β cell number; (ii) the use of assays optimized for analytical sensitivity and calibrated to allow absolute rather than normalized quantifications; and (iii) the application of assay-specific limits of detection/quantification, defined using internationally established clinical chemistry guidelines for data interpretation and confident calling of biomarker detection or nondetection. The GAD65-CBA assay used here is 30 times more sensitive (13) than the previously reported GAD65-time-resolved fluorescence immunoassay (3). Our miR-375 assay was optimized through sequence-specific capture and calibrated with a synthetic calibrator spiked in before miRNA extraction, thus fully accounting for extraction-associated losses and variations. Other groups used calibration curves after RNA extraction or before reverse transcription or used miR-375 quantification relative to housekeeping miRNAs or levels in matched healthy controls.

Our GAD65-CBA and miR-375 assays achieved LoDs around 0.1 pmol/L; using a roughly comparable molar amount of GAD65 and miR-375 in human β cells (±1.5 fmol/103 cells) and assuming a one-compartment distribution without taking into account clearance, both tests can theoretically detect the synchronous destruction of 0.1% of the implanted β cell mass (25). This sensitivity was evidently sufficient to quantify β cell loss during the first 24 hours after islet transplantation. This acute phase allowed a direct comparison of discharge/clearance kinetics of the various biomarkers; this confirmed the previously reported GAD65 half-life around 3.7 hours and indicated a biphasic clearance or degradation of miR-375, similar to the kinetics previously observed for fetal circulating DNA (21). We hypothesized that the initial rapid phase might be due to RNAse-mediated degradation of free miR-375, whereas the much slower second phase might indicate prolonged circulation of RNAse-shielded miR-375 complexed to Argonaut or other proteins.

The diagnostic performance of U INS in our patients after intraportal islet transplantation was disappointing; unlike GAD65 and miR-375, U INS did not correlate with the number of implanted β cells. U INS was inconsistently detected even in patients with massive early posttransplant β cell loss as marked by GAD65 and/or miR-375, and it failed to reach LoQ in most patients, precluding its use for outcome prediction. The inferiority of U INS cannot be explained by assay design because we used the same assay that previously successfully detected β cell death at onset of T1D (7, 14). Further research is needed to exclude biological causes such as an altered INS gene methylation state in the implant in vivo. Although our data did not invalidate U INS, they call for further independent verification in the transplant setting using calibrated assays and highlight the importance of selecting the most appropriate biomarker (combination) as a function of disease stage or model.

Here, we present a model for diagnostic interpretation of GAD65 and miR-375 levels, using dual thresholds rationally selected on the basis of optimal LRs. We used an upper threshold set to maximally increase posttest probability of poor outcome, which corresponds to our previously proposed approach focusing on statistical GAD65 outliers as predictors of poor outcome, which had a very limited sensitivity overall. By introducing a second lower threshold, we can now rule out poor outcome upfront, which is important for reassuring patients and clinicians. By introducing this dual threshold, GAD65 and miR-375 testing provided a clinically useful answer in 71% and 59% of transplant events, respectively. miR-375 and GAD65 showed similar AUCs, were strongly correlated, and were detected at near-equimolar levels, indicating that both biomarkers can be used interchangeably. Therefore, the main added value of using miR-375 is not its analytical or diagnostic superiority, but rather its broader applicability to the majority of patients who have T1D and interfering GADAs.

Our data also underline the critical effect of early transplant‒associated graft loss on secretory graft function 2 months later and indicate that this destruction can adequately be measured. Although differences in transplant procedures and graft composition complicate method transfer, our data show that biomarkers such as GAD65 and miR-375 have potential as companion tests and quality control for the β cell implant procedure, allowing early identification of patients at risk for subsequent graft failure.

In a pilot study, we investigated the enigmatic and likely apoptotic immune-mediated β cell loss during a 2-month posttransplant follow-up. Relying on stringent LoD, we were able to confidently detect incidental episodes of β cell loss. Here again, use of multiple biomarkers increased the chances to detect β cell destruction. We had only a limited number of GADA-negative patients allowing combined analysis of GAD65 and the two nucleic acid‒type biomarkers, so evidently our study was insufficiently powered to correlate frequency or amplitude of biomarker surges to outcome. However, this part of the study indicated several major limitations in the detection of low-grade β cell death in vivo. With the ability to detect the death of one β cell in a thousand, our assays were extremely sensitive. Yet this may still be insufficient, as most late-stage detections were only marginally above baseline signals in healthy controls. This is particularly the case for PCR-amplified miR-375 and U INS. Baseline signals may represent analytical noise due to nonspecific PCR amplification or biologically meaningful circulating levels due to the continuous turnover of other cell types expressing GAD65 (neurons, reproductive glands), miR-375 [various glandular cells (26, 27)], and U INS DNA (all cell types). Their measurement as biomarkers of β cell death is thus only useful in well-defined conditions with high a priori probability of silent β cell death. A second important limitation is the overall short half-life of GAD65 [1 to 4 hours (28, 29)], miR-375 (0.5 to 6 hours), and U INS [±2 hours (6)], which restricts the diagnostic window when screening for silent episodes of β cell loss with unknown kinetics. This “needle in a haystack” conundrum can only be resolved by either frequent sampling (capillary blood analysis, e.g., in conjunction with routine point-of-care blood glucose monitoring), biomarker analysis of urine samples, or the discovery of additional biomarkers with extended half-lives.

In conclusion, GAD65 and miR-375 but not U INS can be used interchangeably to quantify early procedural β cell graft destruction, and this early destruction is important for prognosis of late-stage function. Nucleic acid‒type biomarkers are not necessarily superior in terms of sensitivity to protein-type biomarkers, but they may provide complementary information on condition that robust assays with strictly defined limits of detection are used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cindy Raemdonck and Veerle De Punt (Diabetes Research Center of the Brussels Free University). The authors also thank the Eurotransplant International Foundation and its transplant surgeons and coordinators for organ procurement, and G.A.M. and F.K.G. thank the JDFR Biomarker Working Group for helpful discussions of the data. Finally, the authors thank the staff of the Beta-Cell Bank, the Belgian Diabetes Registry, the Diabetes Research Center of the Brussels Free University, and the Clinical Biology Department of the University Hospital Brussels.

Financial Support: This study was supported by research grants from the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO G.0492.12 project grant and Senior Clinical Investigator career support grant; to G.A.M.); by the Agentschap voor Innovatie door Wetenschap en Technologie (IWT) with IWT-SB-621 (to O.R.C. and G.A.M.) and IWT-SB-141732 (to S.R. and G.A.M.); by the Wetenschappelijk Fonds Willy Gepts from the Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel (to G.A.M. and S.R.); by the Flemish Government (IWT-130138; to D.G.P., B.K., and F.K.G.); by the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes (EFSD/JDRF/Lilly Programme 2015; to G.A.M.); by the Brussels Free University (Strategic Research Program-Growth Funding SRP42; to B.K. and F.K.G.); the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF PNF-2014-181-A-V pilot grant; to F.K.G. and G.A.M.); and the National Institutes of Health (UC4 DK104166; to R.G.M.). Funding organizations did not influence data collection and interpretation.

Author Contributions: S.R., O.R.C., S.A.T., R.G.M., G.S., and G.A.M. contributed to the data collection and data analysis. S.R. and G.A.M. contributed to the study design, literature search, data interpretation, and writing of the manuscript. D.D.S., E.V.B., S.A.T., R.G.M., and Z.L. contributed to the data research, data analysis, and data interpretation and reviewed the manuscript. P.G., B.K., D.G.P., and F.K.G. researched the data and reviewed the manuscript. G.A.M. is the guarantor of this work and as such had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AUC

area under the curve

- CBA

cytometric bead array

- CV

coefficient of variation

- GAD65

65-kDa subunit of glutamate decarboxylase

- GADA

65-kDa subunit of glutamate decarboxylase autoantibody

- IWT

Wetenschap en Technologie

- LoD

limit of detection

- LoQ

limit of quantification

- LR

likelihood ratio

- M INS

methylated insulin DNA

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic

- T1D

type 1 diabetes

- U INS

unmethylated insulin

- WHO U

World Health Organization units

References

- 1. Nano R, Racanicchi L, Melzi R, Mercalli A, Maffi P, Sordi V, Ling Z, Scavini M, Korsgren O, Celona B, Secchi A, Piemonti L. Human pancreatic islet preparations release HMGB1:(ir)relevance for graft engraftment. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(11):2175–2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Itoh T, Iwahashi S, Kanak MA, Shimoda M, Takita M, Chujo D, Tamura Y, Rahman AM, Chung WY, Onaca N, Coates PT, Dennison AR, Naziruddin B, Levy MF, Matsumoto S. Elevation of high-mobility group box 1 after clinical autologous islet transplantation and its inverse correlation with outcomes. Cell Transplant. 2014;23(2):153–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ling Z, De Pauw P, Jacobs-Tulleneers-Thevissen D, Mao R, Gillard P, Hampe CS, Martens GA, In’t Veld P, Lernmark Å, Keymeulen B, Gorus F, Pipeleers D. Plasma GAD65, a marker for early β-cell loss after intraportal islet cell transplantation in diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2314–2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berney T, Mamin A, James Shapiro AM, Ritz-Laser B, Brulhart MC, Toso C, Demuylder-Mischler S, Armanet M, Baertschiger R, Wojtusciszyn A, Benhamou PY, Bosco D, Morel P, Philippe J. Detection of insulin mRNA in the peripheral blood after human islet transplantation predicts deterioration of metabolic control. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1704–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Akirav EM, Lebastchi J, Galvan EM, Henegariu O, Akirav M, Ablamunits V, Lizardi PM, Herold KC. Detection of β cell death in diabetes using differentially methylated circulating DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(47):19018–19023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herold KC, Usmani-Brown S, Ghazi T, Lebastchi J, Beam CA, Bellin MD, Ledizet M, Sosenko JM, Krischer JP, Palmer JP; Type 1 Diabetes TrialNet Study Group . β cell death and dysfunction during type 1 diabetes development in at-risk individuals. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(3):1163–1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fisher MM, Watkins RA, Blum J, Evans-Molina C, Chalasani N, DiMeglio LA, Mather KJ, Tersey SA, Mirmira RG. Elevations in circulating methylated and unmethylated preproinsulin DNA in new-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64(11):3867–3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. El Ouaamari A, Baroukh N, Martens GA, Lebrun P, Pipeleers D, van Obberghen E. miR-375 targets 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 and regulates glucose-induced biological responses in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 2008;57(10):2708–2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, Kuwajima S, Ma X, Macdonald PE, Pfeffer S, Tuschl T, Rajewsky N, Rorsman P, Stoffel M. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature. 2004;432(7014):226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Erener S, Mojibian M, Fox JK, Denroche HC, Kieffer TJ. Circulating miR-375 as a biomarker of β-cell death and diabetes in mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154(2):603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kanak MA, Takita M, Shahbazov R, Lawrence MC, Chung WY, Dennison AR, Levy MF, Naziruddin B. Evaluation of microRNA375 as a novel biomarker for graft damage in clinical islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99(8):1568–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Latreille M, Herrmanns K, Renwick N, Tuschl T, Malecki MT, McCarthy MI, Owen KR, Rülicke T, Stoffel M. miR-375 gene dosage in pancreatic β-cells: implications for regulation of β-cell mass and biomarker development. J Mol Med (Berl). 2015;93(10):1159–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Costa OR, Stangé G, Verhaeghen K, Brackeva B, Nonneman E, Hampe CS, Ling Z, Pipeleers D, Gorus FK, Martens GA. Development of an enhanced sensitivity bead-based immunoassay for real-time in vivo detection of pancreatic β-cell death. Endocrinology. 2015;156(12):4755–4760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tersey SA, Nelson JB, Fisher MM, Mirmira RG. Measurement of differentially methylated INS DNA species in human serum samples as a biomarker of islet β cell death. J Vis Exp. 2016;118(118). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keymeulen B, Gillard P, Mathieu C, Movahedi B, Maleux G, Delvaux G, Ysebaert D, Roep B, Vandemeulebroucke E, Marichal M, In ’t Veld P, Bogdani M, Hendrieckx C, Gorus F, Ling Z, van Rood J, Pipeleers D. Correlation between β cell mass and glycemic control in type 1 diabetic recipients of islet cell graft. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(46):17444–17449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ling Z, Pipeleers DG. Prolonged exposure of human beta cells to elevated glucose levels results in sustained cellular activation leading to a loss of glucose regulation. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(12):2805–2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hilbrands R, Huurman VA, Gillard P, Velthuis JH, De Waele M, Mathieu C, Kaufman L, Pipeleers-Marichal M, Ling Z, Movahedi B, Jacobs-Tulleneers-Thevissen D, Monbaliu D, Ysebaert D, Gorus FK, Roep BO, Pipeleers DG, Keymeulen B. Differences in baseline lymphocyte counts and autoreactivity are associated with differences in outcome of islet cell transplantation in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes. 2009;58(10):2267–2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Movahedi B, Keymeulen B, Lauwers MH, Goes E, Cools N, Delvaux G. Laparoscopic approach for human islet transplantation into a defined liver segment in type-1 diabetic patients. Transpl Int. 2003;16(3):186–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Maleux G, Gillard P, Keymeulen B, Pipeleers D, Ling Z, Heye S, Thijs M, Mathieu C, Marchal G. Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of percutaneous transhepatic injection of β-cell grafts. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16(12):1693–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Song I, Roels S, Martens GA, Bouwens L. Circulating microRNA-375 as biomarker of pancreatic beta cell death and protection of beta cell mass by cytoprotective compounds. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu SC, Lee SW, Jiang P, Leung TY, Chan KC, Chiu RW, Lo YM. High-resolution profiling of fetal DNA clearance from maternal plasma by massively parallel sequencing. Clin Chem. 2013;59(8):1228–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44(3):837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jiang L, Brackeva B, Ling Z, Kramer G, Aerts JM, Schuit F, Keymeulen B, Pipeleers D, Gorus F, Martens GA. Potential of protein phosphatase inhibitor 1 as biomarker of pancreatic β-cell injury in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes. 2013;62(8):2683–2688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brackeva B, De Punt V, Kramer G, Costa O, Verhaeghen K, Stangé G, Sadones J, Xavier C, Aerts JM, Gorus FK, Martens GA. Potential of UCHL1 as biomarker for destruction of pancreatic beta cells. J Proteomics. 2015;117:156–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frank H, Gray SJ. The determination of plasma volume in man with radioactive chromic chloride. J Clin Invest. 1953;32(10):991–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liang Y, Ridzon D, Wong L, Chen C. Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in normal human tissues. BMC Genomics. 2007;8(1):166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N, Aravin A, Pfeffer S, Rice A, Kamphorst AO, Landthaler M, Lin C, Socci ND, Hermida L, Fulci V, Chiaretti S, Foà R, Schliwka J, Fuchs U, Novosel A, Müller RU, Schermer B, Bissels U, Inman J, Phan Q, Chien M, Weir DB, Choksi R, De Vita G, Frezzetti D, Trompeter HI, Hornung V, Teng G, Hartmann G, Palkovits M, Di Lauro R, Wernet P, Macino G, Rogler CE, Nagle JW, Ju J, Papavasiliou FN, Benzing T, Lichter P, Tam W, Brownstein MJ, Bosio A, Borkhardt A, Russo JJ, Sander C, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129(7):1401–1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Waldrop MA, Suckow AT, Marcovina SM, Chessler SD. Release of glutamate decarboxylase-65 into the circulation by injured pancreatic islet β-cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148(10):4572–4578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schlosser M, Walschus U, Klöting I, Walther R. Determination of glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD65) in pancreatic islets and its in vitro and in vivo degradation kinetics in serum using a highly sensitive enzyme immunoassay. Dis Markers. 2008;24(3):191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.