Abstract

Background

Chronic diseases such as chagasic megaesophagus (secondary to Chagas’ disease) have been suggested as etiological factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; however, the molecular mechanisms involved are poorly understood.

Objective

We analyzed hotspot PIK3CA gene mutations in a series of esophageal squamous cell carcinomas associated or not with chagasic megaesophagus, as well as, in chagasic megaesophagus biopsies. We also checked for correlations between the presence of PIK3CA mutations with patients’ clinical and pathological features.

Methods

The study included three different groups of patients: i) 23 patients with chagasic megaesophagus associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (CM/ESCC); ii) 38 patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma not associated with chagasic megaesophagus (ESCC); and iii) 28 patients with chagasic megaesophagus without esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (CM). PIK3CA hotspot mutations in exons 9 and 20 were evaluated by PCR followed by direct sequencing technique.

Results

PIK3CA mutations were identified in 21.7% (5 out of 23) of CM/ESCC cases, in 10.5% (4 out of 38) of ESCC and in only 3.6% (1 case out of 28) of CM cases. In the CM/ESCC group, PIK3CA mutations were significantly associated with lower survival (mean 5 months), when compared to wild-type patients (mean 2.0 years). No other significant associations were observed between PIK3CA mutations and patients’ clinical features or TP53 mutation profile.

Conclusion

This is the first report on the presence of PIK3CA mutations in esophageal cancer associated with chagasic megaesophagus. The detection of PIK3CA mutations in benign chagasic megaesophagus lesions suggests their putative role in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma development and opens new opportunities for targeted-therapies for these diseases.

Keywords: Esophageal cancer, Trypanosoma cruzi, Achalasia, Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, Chagasic megaesophagus, PIK3CA, Mutation

Introduction

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most frequent type of cancer in the world and the sixth most lethal, occurring mainly in developing countries such as Brazil [1]. The most frequent histological subtype is esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), accounting for 90% of cases, especially in high-risk areas [2]. The main risk factors for ESCC are alcohol consumption, tobacco (mainly in association) and hot-beverage consumption [3]. It is also reported that chronic diseases, such as the chagasic megaesophagus, can be associated with ESCC development [4].

Chagasic megaesophagus is the late manifestation of Chagas’ disease (caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi) [5]. Direct infection of Trypanosoma cruzi will lead to destruction of the intramural myenteric neurons in the esophagus, causing inflammation and production of neurotoxins. This will result in uncoordinated contractions and reduction of peristalsis of the organ, altering the functioning of the lower esophageal sphincter and progressive dilation of the esophagus (megaesophagus) [6]. In Brazil, one of the endemic regions of Chagas’ disease, approximately 4 million people are infected with the parasite and about 6–7% of these patients will develop chagasic megaesophagus [5]. Patients affected with this lesion are more likely to develop ESCC (3–10%) when compared to the general population [4].

The carcinogenic mechanisms of ESCC development in the context of chagasic megaesophagus have been little explored. Recently, our group showed the high frequency (13/32, 40.6%) of TP53 mutations in ESCC associated with chagasic megaesophagus [7]. Moreover, we also reported the presence of microsatellite instability (MSI) in a small fraction (1/19, 5.3%) of cases [8]. However, many other genes are known to be involved in ESCC carcinogenesis as demonstrated by the TCGA consortium [9].

One of these genes is the PI3KCA, which encodes the protein phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), that belongs to a family of lipid kinases that encodes the p110α catalytic subunit [10]. PI3K is a quite complex signaling pathway since it regulates cell growth, proliferation, cell motility, the production of new proteins, apoptosis and cell survival [10]. Therefore, its activation will lead to many downstream pathways that regulate several cellular functions, including those involved in the development of cancer [10, 11]. Recurrent PI3KCA oncogenic mutations were identified in several types of tumors, including colorectal, breast, ovary, gastric, and recently in ESSC [12]. The mutations occur mainly in exons 9 (E542K and E545K) and 20 (H1047R) [12]. Recently, it was shown that PIK3CA mutations, namely H1047R, also disrupt cellular genetic stability, increasing the frequency of chromosomal errors and leading to tetraploidy [13]. Importantly, therapeutic strategies targeting the PIK3/Akt signaling pathway have been developed and could constitute effective treatment options for patients harboring PI3KCA mutations [14].

Therefore, in the current study we performed the mutation analysis of PIK3CA gene in patients with ESCC and chagasic megaesophagus associated or not with ESCC, and searched for associations between the mutation status and patients’ clinical and pathological features.

Materials and methods

Study population

In this retrospective study, we analyzed 89 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues of three groups of patients: i) 23 patients with chagasic megaesophagus associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (CM/ESCC); ii) 38 patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma without chagasic megaesophagus (ESCC); and iii) 28 patients with chagasic megaesophagus without esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (CM). All chagasic megaesophagus patients were serologic positive for Chagas’ disease and/or had exams (imaging and histopathology) that confirmed the presence of megaesophagus. The patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma without chagasic megaesophagus were all serologic negative for Chagas’ disease and had exams (imaging and histopathology) that confirmed malignant disease. These patients were previously described for their clinical-pathological and molecular TP53 and MSI features [7, 8].

The samples were obtained from patients treated between 1990 and 2016 in three different institutions from the Southeast of Brazil, namely: Barretos Cancer Hospital, Barretos, São Paulo State; Federal University of Triângulo Mineiro (UFTM), Uberaba, Minas Gerais State and São Paulo State University (UNESP), Botucatu, São Paulo State. All clinical and pathological information was obtained through medical record review.

DNA isolation

Following tissue macro-dissection, DNA was isolated from FFPE tissue representative of the tumor lesions in ESCC and CM/ESCC groups and esophageal tissues in CM group, as previously described [7]. Briefly, the tumor area was delineated in a hematoxylin-eosin stained (HE, Merck KGaA, GE) section by a pathologist, and the marked area was scraped by scalp from 3 to 5 10 μm unstained slides into a 1,5 ml tube. Afterwards, the tissue was subjected to the dewaxing step by heating (80 °C – 20 min), followed by sequential washing in xylol (5 min) and decreasing concentrations of ethanol (1 min - 100, 70 and 50%) and nuclease-free water9 (1 min). DNA isolation was performed using the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacture’s protocol.

PIK3CA mutation analysis

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) followed by direct sequencing (Sanger method) was performed for the analysis of hotspot mutations (exons 9 and 20) of the PIK3CA gene as previously described [15]. The PCR was performed on the 89 samples under the following conditions: 5X Flexi Buffer (pH 8.5) and 25 mM MgCl2 (Promega, USA), 200 μM dNTPmix (Invitrogen, USA), 200 nM primers exon 9 (forward 5’-CTGTGAATCCAGAGGGGAAA-3′ and reverse 5’-ACATGCTGAGATCAGCCAAAT-3′) and exon 20 (forward 5’-ATGATGCTTGGCTCTGGAAT-3′ and reverse 5’-GGTCTTTGCCTGCTGAGAGT-3′), 1.25 U GoTaq®Hot Start Polymerase (Promega, USA), and nuclease-free water (Gibco, BRL, Life Technologies, USA) in a final volume of 25 μl and 5 μl of DNA at 50 ng/μl from each patient were added [15]. Amplification was performed in a thermocycler according to the protocol: 96 °C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles at 96 °C for 45 s, 55.5 °C for 45 s and 72 °C for 45 s and final extension of 72 °C for 10 min, followed by a hold at 4 °C. PCR products were subjected to 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis with Gel Red (Biotium, Hayward, CA) to evaluate the amplification of the gene of interest.

After agarose gel validation, we purified the preparation using the enzyme ExoSap-IT (GE Technology, Cleveland, USA), followed by the sequencing reaction using BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Applied Biosystems, USA) and 3.2 μM of specific primers and re-purified with xTerminator (Life Technology). The products were sequenced using the 3500 series Genetic Analyzer Capillary Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, USA). All the cases that showed mutations were confirmed with a new PCR reaction and direct sequencing.

Statistical analysis

Characterization of the study population was performed through frequency tables for qualitative variables, and measures of central tendency and dispersion (mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum) for the quantitative variables, comparing the different groups. To verify the association between PIK3CA mutation status and clinical groups, pathological and molecular features, Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests were applied. We performed an overallsurvival analysis using the Kaplan-Meier limit estimator and the Log-rank test to compare the survival curves between the groups.

The level of significance adopted was 5% (p ≤ 0.05). Statistical analyzes were in SPSS software v.21.0.

Results

Characterization of the population

The clinical-pathological characteristics of the patients in the three groups are described in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was higher in the chagasic groups (Table 1). As already reported in our previous studies [7], concerning risk factors for esophageal cancer, the ESCC and CM/ESCC groups were statistically associated with higher tobacco and alcohol consumption (Table 1).

Table 1.

The clinical-pathological features of the three groups of patients

| Variable | Groups (n = 89) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | CM/ESCC (n = 23) | ESCC (n = 38) | CM (n = 28) | p-value | |

| Gender | Female | 4 (17.4%) | 7 (18.4%) | 4 (14.3%) | 0.937** |

| Male | 19 (82.6%) | 31 (81.6%) | 24 (85.7%) | ||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 59 (11) | 57 (9) | 59 (11) | 0.039 *** |

| Min - Max | 37–76 | 36–75 | 37–76 | ||

| Alcohol consumption | No | 7 (31.8%) | 8 (21.1%) | 20 (71.4%) | < 0.001 * |

| Yes | 15 (68.2%) | 30 (78.9%) | 8 (28.6%) | ||

| Missing | 11 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Tobacco consumption | No | 4 (18.2%) | 6 (15.8%) | 16 (57.1%) | < 0.001 * |

| Yes | 18 (81.8%) | 32 (84.2%) | 12 (42.9%) | ||

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Tumor differentiation | Well differentiated | 5 (22.7%) | 7 (19.4%) | NA | 0.639** |

| Moderate differentiated | 16 (72.7%) | 24 (66.7%) | NA | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 1 (4.5%) | 5 (13.9%) | NA | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2 | NA | ||

| TNM Staging | I/II | 4 (23.5%) | 16 (42.1%) | NA | 0.235* |

| III/IV | 13 (76.5%) | 22 (57.9%) | NA | ||

| Missing | 6 | 0 | NA | ||

| Megaesophagus grades | GI/GII | 10 (45.5%) | NA | 4 (14.3%) | 0.025 * |

| GIII/GIV | 12 (54.5%) | NA | 24 (85.7%) | ||

| Missing | 1 | NA | 0 | ||

*Chi-square association test; **Fisher’s exact test; ***Analysis of variance. CM/ESCC – chagasic megaesophagus associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; ESCC – esophageal squamous cell carcinoma without chagasic megaesophagus; CM – chagasic megaesophagus without esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; SD - standard deviation; NA – not applicable; Bold numbers - statistical significance

Mutation analysis of PIK3CA gene

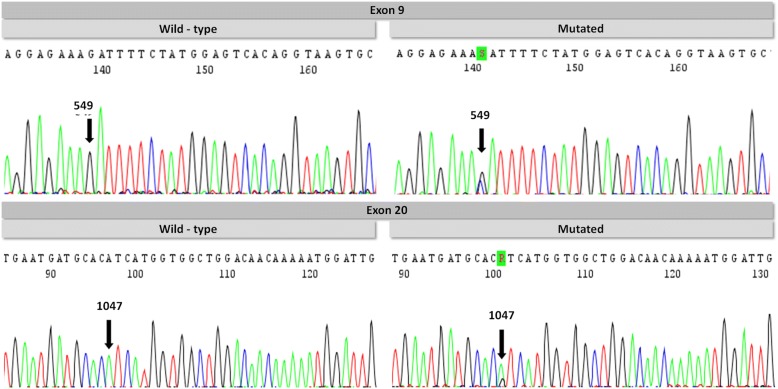

The PIK3CA mutation analysis showed the presence of mutations in 21.7% of patients in CM/ESCC group, followed by 10.5% in ESCC group and 3.6% in CM group (Fig. 1 and Table 2). The frequency of mutations was similar in exons 9 and 20 (Table 3). With the exception of three variants (A1027D, K1030R and T1053K), all the other mutations have already been reported in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer database – COSMIC (http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic) (Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Fig. 1.

Electropherogram of PIK3CA gene. Exon 9 – wild-type sequence and mutated sequence (D549H). Exon 20 – wild-type sequence and mutated sequence (H1047R)

Table 2.

Frequency of PIK3CA mutations in the three study groups

| Variable | Groups (n = 89) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | CM/ESCC (n = 23) | ESCC (n = 38) | CM (n = 28) | p-value | |

| PIK3CA gene | WT | 18 (78.3%) | 34 (89.5%) | 27 (96.4%) | 0.132** |

| MUT | 5 (21.7%) | 4 (10.5%) | 1 (3.6%) | ||

**Fisher’s exact test. CM/ESCC – chagasic megaesophagus associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; ESCC – esophageal squamous cell carcinoma without chagasic megaesophagus; CM – chagasic megaesophagus without esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. WT – wild-type; MUT – mutant; N – number of cases

Table 3.

Profile of oncogenic PIK3CA mutations in the three study groups

| Group | Sample ID | Exon | Codon | Codon (WT – MUT) | Type of mutation | Amino acids change | Nature of mutation | COSMIC ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM/ESCC | 111 T | 9 | 545 | GAG – GCA | A → C | E545A | Missense | COSM12458 |

| 122 T | 9 | 549 | GAT – CAT | G → C | D549H | Missense | COSM219119 | |

| 114 T | 20 | 1027 | GCC – GAC | C → A | A1027D | Missense | Not reported | |

| 119 T | 20 | 1047 | CAT – CTT | A → T | H1047L | Missense | COSM776 | |

| 124 T | 20 | 1047 | CAT–CGT | A → G | H1047R | Missense | COSM775 | |

| ESCC | 26 T | 9 | 545 | GAG – GCG | A → C | E545A | Missense | COSM12458 |

| 120 T | 9 | 555 | AGG – AAG | G → A | R555K | Missense | COSM1716158 | |

| 36 T | 9 | 524 | AGG – AAG | G → A | R524K | Missense | COSM53245 | |

| 4 T | 20 | 1030 | AAA – AGA | A → G | K1030R | Missense | Not reported | |

| CME | 101 M | 20 | 1053 | ACA – AAA | C → A | T1053K | Missense | Not reported |

CME/ESCC – chagasic megaesophagus associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; ESCC – esophageal squamous cell carcinoma without chagasic megaesophagus; CME – chagasic megaesophagus without esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. A – adenine; C – cytosine; G – guanine; T – thymine. WT – wild-type; MUT – mutant

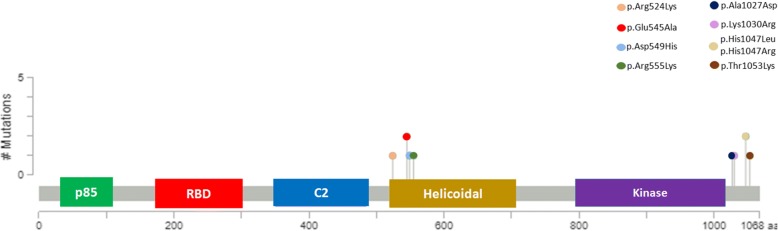

Fig. 2.

PIK3CA protein and missense mutation overview

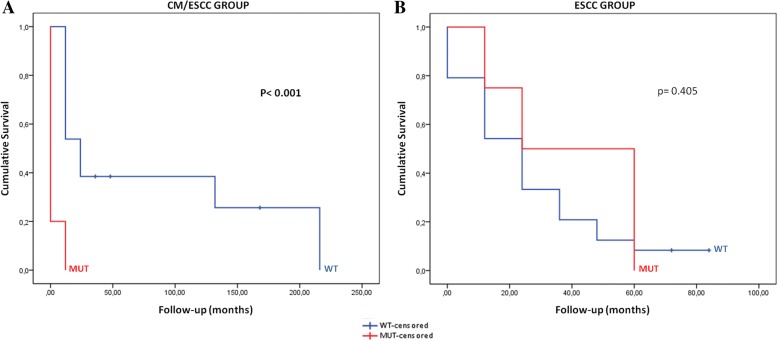

No significant associations were observed between the PIK3CA mutation status and patients pathological features (Table 4). Furthermore, we assessed the role of PIK3CA mutations on patients’ overall survival in both groups affected by cancer (CM/ESCC and ESCC) (Fig. 3). In CM/ESCC group, we observed that the presence of PIK3CA mutations was significantly associated with a lower survival rate from the diagnosis of cancer compared to wild-type patients (Fig. 3a). The mean patients’ overall survival in cases from the CM/ESCC group mutated for the PIK3CA was 5 months, in comparison with 2.0 years for wild-type PIK3CA patients (Log-rank, p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Association between PIK3CA mutation status with main clinical-pathological features in the three groups

| Variable | PIK3CA gene | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM/ESCC group | ESCC group | CM group | ||||||||

| Category | WT | MUT | p-value | WT | MUT | p-value | WT | MUT | p-value | |

| Alcohol consumption | No | 6 (35.3%) | 1 (20%) | 1.000** | 7 (21.2%) | 1 (20%) | 1.000** | 19 (70.4%) | 1 (100%) | 1.000** |

| Yes | 11 (64.7%) | 4 (80%) | 26 (78.8%) | 4 (80%) | 8 (29.6%) | 0 (0%) | ||||

| Tobacco consumption | No | 4 (23.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.535** | 5 (15.2%) | 1 (20%) | 1.000** | 15 (100%) | 1 (100%) | 1.000** |

| Yes | 13 (76.5%) | 5 (100%) | 28 (84.8%) | 4 (80%) | 12 (44.4%) | 0 (0%) | ||||

| Tumor differentiation | Well | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (25%) | 1.000** | 7 (22.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.171** | NA | NA | NA |

| Moderate | 13 (72.2%) | 3 (75%) | 21 (67.7%) | 3 (60%) | NA | NA | ||||

| Poorly | 1 (5.6%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (9.7%) | 2 (40%) | NA | NA | ||||

| TNM Staging | I e II | 4 (28.6%) | 0 (0%) | 0.541** | 15 (46.9%) | 1 (20%) | 0.421** | NA | NA | NA |

| III e IV | 10 (71.4%) | 3 (100%) | 17 (53.1%) | 4 (80%) | NA | NA | ||||

| Megaesophagus degree | GI/GII | 7 (41.2%) | 3 (60%) | 0.406** | NA | NA | NA | 3 (11.1%) | 1 (100%) | 0.143** |

| GIII/GIV | 10 (58.8%) | 2 (40%) | NA | NA | 24 (88.9%) | 0 (0%) | ||||

| TP53 gene [7] | WT | 9 (50%) | 2 (40%) | 1.000** | 20 (60.6%) | 2 (40%) | 0.632** | 26 (96.3%) | 1 (100%) | 1.000** |

| MUT | 9 (50%) | 3 (60%) | 13 (39.4%) | 3 (60%) | 1 (3.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||||

**Fisher’s exact test; ***Analysis of variance. CME/ESCC – chagasic megaesophagus associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; ESCC – esophageal squamous cell carcinoma without chagasic megaesophagus; CME – chagasic megaesophagus without esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. N – number of cases; SD – standard deviation; NA – not applicable; WT – wild-type; MUT – mutated

Fig. 3.

Cumulative survival of patients associated with the PIK3CA gene status. The red curves represent patients with mutation and the blue curves represent wild-type patients. a CM/ESCC – chagasic megaesophagus associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus; b ESCC – squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus; MUT – mutant; WT – wild-type

Table 5.

The time and average of patients’ overall survival according to PIK3CA mutation status

| Groups | Time | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total | N events | 6 months | 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | Median survival | p-value | |

| CM/ESCC | WT | 13 | 10 | 79.4% | 72.2% | 43.3% | 28.9% | 2 years | < 0.001 * |

| MUT | 5 | 5 | 20.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 5 months | ||

| ESCC | WT | 24 | 22 | 82.6% | 64.7% | 32.6% | 14.5% | 2 years | 0.405 |

| MUT | 4 | 4 | 80.0% | 80.0% | 60.0% | 0.0% | 2.5 years | ||

*Log-rank test. CM/ESCC – chagasic megaesophagus associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma; ESCC – esophageal squamous cell carcinoma without chagasic megaesophagus; WT – wild-type; MUT – mutated; Bold numbers - statistical significance

Additionally, we evaluated the association of PIK3CA and TP53 mutation status, and no association was found (Table 4).

Discussion

Among the several risk factors for the development of ESCC, the chagasic megaesophagus (late complication of Chagas’ disease) has been a minor etiological factor and little explored [4]. Nevertheless, Chagas’ disease is still an important public health problem, particularly in Latin-America, where approximately 20 million people are infected with Chagas’ disease and approximately 6–7% of these people will develop chagasic megaesophagus [5, 16].

In the present study, we investigated the frequency of PIK3CA mutations in regions of hotspot (exons 9 and 20) in patients with chagasic megaesophagus associated with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (CM/ESCC) and compared with patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma without chagasic megaesophagus (ESCC) and patients with chagasic megaesophagus without esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (CM). We observed that patients in the CM/ESCC group had a higher frequency of mutations (5/23, 21.7%) followed by patients in the ESCC group (4/38, 10.5%), and in the CM group (1/28, 3.6%). This is the first report of PIK3CA mutation in ESCC that developed in the context of chagasic megaesophagus and the significant frequency of mutations (~ 22%) suggest that PIK3CA plays an important role in the carcinogenesis of CM/ESCC patients. Moreover, the presence of PIK3CA mutation in a benign lesion further supports the putative role of chagasic megaesophagus as an ESCC-related condition. The frequency of mutations identified in our study is in line with that reported in the literature for ESCC patients, with frequencies varying from 2.2 to 32.8% (Table 6) [9, 17–33]. This variation can be due to several factors, such as type of tissue (frozen vs FFPE), distinct methodologies for mutation screening and distinct ethnic groups of patients. (Table 6).

Table 6.

Frequency of PIK3CA mutations identified in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma worldwide

| References | Year | Country (Region) | Patients of study | PIK3CA mutated (%) | Type of sample | Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mori et al. [24] | 2008 | Japan | 88 | 2.2% | FT | Direct Sequencing |

| Wang et al. [30] | 2013 | China | 76 | 3.9% | FT | Direct Sequencing |

| Akagi et al. [17] | 2009 | Japan | 52 | 7.7% | FFPE | Direct Sequencing |

| Kim et al. [21] | 2016 | Korea | 534 | 10.5% | FFPE | Direct Sequencing |

| Phillips et al. [25] | 2006 | Australia | 35 | 11.8% | FFPE | Direct Sequencing |

| Zheng et al. [33] | 2016 | China | 79 | 19.7% | FT | Pyrosequencing |

| Shigaki et al. [27] | 2013 | China | 219 | 21.0% | FT | Pyrosequencing |

| Liu et al. [23] | 2017 | China | 210 | 22.9% | FFPE | Pyrosequencing |

| Baba et al. [18] | 2015 | Japan | 440 | 23.0% | FFPE | Pyrosequencing |

| Yang et al. [31] | 2017 | China | 24 | 4.2% | FFPE | NGS |

| Song et al. [28] | 2014 | China | 158 | 4.5% | FT | NGS |

| Lin et al. [22] | 2014 | China | 139 | 7.0% | FFPE | NGS |

| Gao et al. [19] | 2014 | Japan | 133 | 9.0% | FT | NGS |

| Sawada et al. [26] | 2016 | Japan | 144 | 10.4% | FT | NGS |

| TCGA et al. [9] | 2017 | Western and Eastern | 90 | 13.0% | FT | NGS |

| Yokota et al. [37] | 2018 | Japan | 126 | 13.5% | FFPE | NGS |

| Zhang et al. [32] | 2015 | China | 90 | 17.0% | FT | NGS |

| Wang et al. [29] | 2015 | USA | 71 | 24.0% | FFPE | NGS |

NGS – next generation sequencing; FFPE – formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue; FT – fresh frozen tissue

The PIK3CA gene is often mutated in several tumors types and most of its mutations occur in hotspot regions, such as E542K and E545A located in the helical domain (exon 9), and H1047R and H1047L in the kinase domain (exon 20) [11]. These mutations lead to the activation of the PIK3 pathway and have a great potential in oncogenic activities [11]. Interestingly, most of these mutations (E545A, H1047R and H1047L) occurred in patients in the CM/ESCC group and only one (E545A) in one patient in the ESCC group. We also identified other previously described important mutations (Table 3), the D549H mutation observed in the CM/ESCC group was reported in vulva and hepatocellular cancer [34]; R524K mutation found in the ESCC group was reported in colorectal cancer [35]; and the R555K mutation was reported in ovary cancer [36]. Interestingly, it is important to note that we identified three mutations in exon 20 that have not yet been reported (A1027D and K1030R in CM/ESCC group; T1053K in CM group). All these mutations occurred in patients with chagasic megaesophagus whose mutational profile of PIK3CA was never reported.

Importantly, we observed that CM/ESCC patients harboring PIK3CA mutations were associated with lower overall survival, suggesting its role as a prognostic biomarker in this group of patients. Interestingly, the results of our analyzes of the survival of the mutated patients differ from those reported by others studies, especially in regions of some risk such as Asia, in which patients with ESCC with mutations of the PIK3CA gene had a favorable overall survival compared to patients wild-type [37].

Notably, inhibitors of the PIK3-Akt-mTOR pathway have been developed as cancer target therapy alternatives, and patients harboring PIK3CA gene mutations could be potential candidates for such therapeutic approach [14]. Interestingly, phase I and II clinical trials using pan-PIK3CA agents (PIK3-class I), such as buparlisib (BKM120), an oral agent that affects α, β, γ and δ isoforms of PI3K [38], showed efficacy in several solid tumors, including head and neck cancer [39]. Copanlisib (BAY80–6946), an intravenous agent that affects α and δ isoforms of PI3K, also showed promising results in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas [40]; as well as pictilisib (GDC-0941), an oral agent that affects γ and δ isoforms of PI3K, where a good response was reported in breast, colorectal, ovarian and non-small cell lung cancer [41]. Therefore, we can hypothesize that a subset of ESCC and CM/ESCC patients with PIK3CA mutations may benefit from these targeted-therapies and consequently improve their dismal survival.

In conclusion, this is the first study that analyzed and identified PIK3CA activating mutations in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinomas associated with chagasic megaesophagus (CM/ESCC), which were associated with a worse outcome. Moreover, the identification of mutations in benign chagasic megaesophagus suggests their putative role in the etiology of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and opens new opportunities for the treatment of these neglected patients with targeted-therapies.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was financially supported by CAPES and FAPESP - Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo [Grant number 2015/20077–3 to FFM] and Barretos Cancer Hospital internal research funds (PAIP).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CM

Chagasic megaesophagus

- ESCC

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- MSI

Microsatellite instability

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

Authors’ contributions

FFM participated in the conception of the study, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the results, and draft of the manuscript. ACC, CFL, ATTO, CSN, SRMS, EC, SJA, MAMR and MACAH participated in the acquisition and quality assessment of the data collection and results interpretation. ALF and DPG participated in the, data collection, analysis and interpretation and draft of the manuscript. RMR participated in the designed, supervision, data interpretation and drafting and final revision of the manuscript. All authors gave final approval of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The local ethic committees approved the study (number 1010/2015).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests for this present study.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–E386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smyth EC, Lagergren J, Fitzgerald RC, Lordick F, Shah MA, Lagergren P, Cunningham D. Oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17048. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prabhu A, Obi KO, Rubenstein JH. The synergistic effects of alcohol and tobacco consumption on the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:822–827. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tustumi F, Bernardo WM, da Rocha JRM, Szachnowicz S, Seguro FC, Bianchi ET, Sallum RAA, Cecconello I. Esophageal achalasia: a risk factor for carcinoma. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1–8. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rassi A, Jr, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010;375:1388–1402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandolfino JE, Gawron AJ. Achalasia: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313:1841–1852. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.2996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacerda CF, Cruvinel-Carloni A, de Oliveira AT, Scapulatempo-Neto C, Lopez RV, Crema E, Adad SJ, Rodrigues MA, Henry MA, Guimaraes DP, Reis RM. Mutational profile of TP53 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma associated with chagasic megaesophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1–9. doi: 10.1093/dote/dow040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campanella NC, Lacerda CF, Berardinelli GN, Abrahao-Machado LF, Cruvinel-Carloni A, De Oliveira ATT, Scapulatempo-Neto C, Crema E, Adad SJ, Rodrigues MAM, et al. Presence of microsatellite instability in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma associated with chagasic megaesophagus. Biomark Med. 2018;12:573–582. doi: 10.2217/bmm-2017-0329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Analysis Working Group: Asan U, Agency BCC, Brigham, Women’s H, Broad I, Brown U, Case Western Reserve U, Dana-Farber Cancer I, Duke U et al. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature. 2017;541:169–175. doi: 10.1038/nature20805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fruman DA, Chiu H, Hopkins BD, Bagrodia S, Cantley LC, Abraham RT. The PI3K pathway in human disease. Cell. 2017;170:605–635. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karakas B, Bachman KE, Park BH. Mutation of the PIK3CA oncogene in human cancers. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:455–459. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuels Y, Wang Z, Bardelli A, Silliman N, Ptak J, Szabo S, Yan H, Gazdar A, Powell SM, Riggins GJ, et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004;304:554. doi: 10.1126/science.1096502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berenjeno IM, Pineiro R, Castillo SD, Pearce W, McGranahan N, Dewhurst SM, Meniel V, Birkbak NJ, Lau E, Sansregret L, et al. Oncogenic PIK3CA induces centrosome amplification and tolerance to genome doubling. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1773. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02002-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo J, Manning BD, Cantley LC. Targeting the PI3K-Akt pathway in human cancer: rationale and promise. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:257–262. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velho S, Oliveira C, Ferreira A, Ferreira AC, Suriano G, Schwartz S, Jr, Duval A, Carneiro F, Machado JC, Hamelin R, Seruca R. The prevalence of PIK3CA mutations in gastric and colon cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41:1649–1654. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Neglected tropical diseases, hidden successes, emerging opportunities. Geneva: WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication; 2009.

- 17.Akagi I, Miyashita M, Makino H, Nomura T, Hagiwara N, Takahashi K, Cho K, Mishima T, Ishibashi O, Ushijima T, et al. Overexpression of PIK3CA is associated with lymph node metastasis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:767–775. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baba Y, Ishimoto T, Harada K, Kosumi K, Murata A, Miyake K, Hiyoshi Y, Kurashige J, Iwatsuki M, Iwagami S, et al. Molecular characteristics of basaloid squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: analysis of KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA mutations and LINE-1 methylation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3659–3665. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4445-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao YB, Chen ZL, Li JG, Hu XD, Shi XJ, Sun ZM, Zhang F, Zhao ZR, Li ZT, Liu ZY, et al. Genetic landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:1097–1102. doi: 10.1038/ng.3076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou J, Jiang D, Zhang J, Gavine PR, Xu S, Liu Y, Xu C, Huang J, Tan Y, Wang H, et al. Frequency, characterization, and prognostic analysis of PIK3CA gene mutations in Chinese esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim HS, Lee SE, Bae YS, Kim DJ, Lee CG, Hur J, Chung H, Park JC, Shin SK, Lee SK, et al. PIK3CA amplification is associated with poor prognosis among patients with curatively resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:30691–30701. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin DC, Hao JJ, Nagata Y, Xu L, Shang L, Meng X, Sato Y, Okuno Y, Varela AM, Ding LW, et al. Genomic and molecular characterization of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46:467–473. doi: 10.1038/ng.2935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu SY, Chen W, Chughtai EA, Qiao Z, Jiang JT, Li SM, Zhang W, Zhang J. PIK3CA gene mutations in northwest Chinese esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:2585–2591. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i14.2585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori R, Ishiguro H, Kimura M, Mitsui A, Sasaki H, Tomoda K, Mori Y, Ogawa R, Katada T, Kawano O, et al. PIK3CA mutation status in Japanese esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Surg Res. 2008;145:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phillips WA, Russell SE, Ciavarella ML, Choong DY, Montgomery KG, Smith K, Pearson RB, Thomas RJ, Campbell IG. Mutation analysis of PIK3CA and PIK3CB in esophageal cancer and Barrett's esophagus. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2644–2646. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sawada G, Niida A, Uchi R, Hirata H, Shimamura T, Suzuki Y, Shiraishi Y, Chiba K, Imoto S, Takahashi Y, et al. Genomic landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a Japanese population. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1171–1182. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shigaki H, Baba Y, Watanabe M, Murata A, Ishimoto T, Iwatsuki M, Iwagami S, Nosho K, Baba H. PIK3CA mutation is associated with a favorable prognosis among patients with curatively resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2451–2459. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song Y, Li L, Ou Y, Gao Z, Li E, Li X, Zhang W, Wang J, Xu L, Zhou Y, et al. Identification of genomic alterations in oesophageal squamous cell cancer. Nature. 2014;509:91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature13176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang K, Johnson A, Ali SM, Klempner SJ, Bekaii-Saab T, Vacirca JL, Khaira D, Yelensky R, Chmielecki J, Elvin JA, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinomas and esophageal adenocarcinomas reveals similarities and differences. Oncologist. 2015;20:1132–1139. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang WF, Xie Y, Zhou ZH, Qin ZH, Wu JC, He JK. PIK3CA hypomethylation plays a key role in activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in esophageal cancer in Chinese patients. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2013;34:1560–1567. doi: 10.1038/aps.2013.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang JW, Choi YL. Genomic profiling of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC)-basis for precision medicine. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213:836–841. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang L, Zhou Y, Cheng C, Cui H, Cheng L, Kong P, Wang J, Li Y, Chen W, Song B, et al. Genomic analyses reveal mutational signatures and frequently altered genes in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96:597–611. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng H, Wang Y, Tang C, Jones L, Ye H, Zhang G, Cao W, Li J, Liu L, Liu Z, et al. TP53, PIK3CA, FBXW7 and KRAS mutations in esophageal Cancer identified by targeted sequencing. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2016;13:231–238. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watkins JC, Howitt BE, Horowitz NS, Ritterhouse LL, Dong F, MacConaill LE, Garcia E, Lindeman NI, Lee LJ, Berkowitz RS, et al. Differentiated exophytic vulvar intraepithelial lesions are genetically distinct from keratinizing squamous cell carcinomas and contain mutations in PIK3CA. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:448–458. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berg M, Danielsen SA, Ahlquist T, Merok MA, Agesen TH, Vatn MH, Mala T, Sjo OH, Bakka A, Moberg I, et al. DNA sequence profiles of the colorectal cancer critical gene set KRAS-BRAF-PIK3CA-PTEN-TP53 related to age at disease onset. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13978. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Niskakoski A, Kaur S, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Lassus H, Jarvinen HJ, Mecklin JP, Butzow R, Peltomaki P. Distinct molecular profiles in lynch syndrome-associated and sporadic ovarian carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:2596–2608. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokota T, Serizawa M, Hosokawa A, Kusafuka K, Mori K, Sugiyama T, Tsubosa Y, Koh Y. PIK3CA mutation is a favorable prognostic factor in esophageal cancer: molecular profile by next-generation sequencing using surgically resected formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:826. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4733-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maira SM, Pecchi S, Huang A, Burger M, Knapp M, Sterker D, Schnell C, Guthy D, Nagel T, Wiesmann M, et al. Identification and characterization of NVP-BKM120, an orally available pan-class I PI3-kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:317–328. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Soulieres D, Faivre S, Mesia R, Remenar E, Li SH, Karpenko A, Dechaphunkul A, Ochsenreither S, Kiss LA, Lin JC, et al. Buparlisib and paclitaxel in patients with platinum-pretreated recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (BERIL-1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:323–335. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patnaik A, Appleman LJ, Tolcher AW, Papadopoulos KP, Beeram M, Rasco DW, Weiss GJ, Sachdev JC, Chadha M, Fulk M, et al. First-in-human phase I study of copanlisib (BAY 80-6946), an intravenous pan-class I phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors and non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1928–1940. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sarker D, Ang JE, Baird R, Kristeleit R, Shah K, Moreno V, Clarke PA, Raynaud FI, Levy G, Ware JA, et al. First-in-human phase I study of pictilisib (GDC-0941), a potent pan-class I phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:77–86. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-0947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.