Abstract

Fragmentation of collagen fibrils and aberrant elastic material (solar elastosis) in the dermal extracellular matrix (ECM) are among the most prominent features of photodamaged human skin. These alterations impair the structural integrity and create a dermal microenvironment prone to skin disorders. The objective of this study was to determine the physical properties (surface roughness, stiffness, and hardness) of the dermal ECM in photodamaged and subject matched sun-protected human skin. Skin samples were sectioned and analyzed by histology, atomic force microscopy (AFM) and nanoindentation. Dermal ECM collagen fibrils were more disorganized (i.e. rougher surface), and the dermal ECM was stiffer, and harder, in photodamaged forearm, compared to sun-protected underarm skin. Cleavage of collagen fibrils in sun-protected underarm dermis by recombinant human matrix metalloproteinase-1 resulted in rougher collagen fibril surface and reduced dermal stiffness and hardness. Degradation of elastotic material in photodamaged skin by treatment with purified neutrophil elastase reduced stiffness and hardness, without altering collagen fibril surface roughness. Additionally, expression of two members of the lysyl oxidase (LOX) gene family, which insert crosslinks that stiffen and harden collagen fibrils, was elevated in photodamaged forearm dermis. These data elucidate the contributions of fragmented collagen fibrils, solar elastosis, and elevated collagen crosslinking to the physical properties of the dermal ECM in photodamaged human skin. This new knowledge extends current understanding of the impact of photodamage on the dermal ECM microenvironment.

Keywords: Photoaging, Physical property, Collagen, Elastosis, Lysyl oxidase

1. Introduction

Human skin experiences harmful injuries from environmental sources such as solar ultraviolet (UV) irradiation (photoaging) 1, 2. Histological and ultrastructural studies have revealed that the major alterations in photodamaged skin are seen in dermal connective tissue, characterized by damaged and disorganized collagen fibrils as well as massive accumulation of aberrant elastic material (solar elastosis)1, 3. Type I collagen is the most abundant extracellular matrix (ECM) protein, constituting nearly 90% of the skin’s dry weight 4. Alterations of dermal collagen fibrils are largely responsible for the clinical features of photoaged skin, such as fragile and wrinkled skin 1, 4–6. Mechanistically, photodamaged skin is largely driven by elevated matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) 7, 8, which degrade collagen fibrils in the skin. Alterations of collagen fibrils impair normal architecture of skin connective tissue and create a tissue microenvironment more prone to skin disorders, such as delayed wound healing 4, 9 and cancer in elderly 10–14.

Although much effort has been exerted towards understanding the molecular alterations leading to the properties of photodamaged skin, little information is available with respect to the biophysical properties of the photodamaged dermis. Here we have applied atomic force microscopy (AFM) and nanoindentation techniques to evaluate physical surface properties of the ECM in photodamaged (forearm) and sun-protected (underarm) human dermis. We found that collagen fibrils in photodamaged forearm is rougher, stiffer, and harder, largely due to collagen disorganization, elastosis, and crosslinking. These data provide insight into the physical properties of the damaged dermis in photodamaged human skin.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Procurement of human skin samples and compliance with ethical standards

Skin biopsies from photodamaged extensor forearm and subject matched sun-protected underarm were obtained from six individuals (age 57±5 years). The presence of photodamaged skin was determined based on clinical criteria, as described previously 15. For histological analysis, skin cryo-sections (7μm thickness) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Some experiments, photodamaged forearm skin cryo-sections were treated with purified neutrophil elastase (0.01unit/ml, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 2 hours at 37°C. All skin samples were obtained under a protocol approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All volunteers provided written informed consent.

2.2 Immunohistology and Verhoff van Geison (VVG) elastic staining

Immunohistology was performed as described previously 16. Briefly, skin OCT-embedded cryo-sections (7μm thick) were fixed in paraformaldehyde. Subsequently, the slides were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with normal control serum followed by incubation of anti-elastin antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA, cat#: ab77804). All sections were lightly counterstained with hematoxylin and were mounted with mounting media (Vector, Laboratories, CA, USA). To visualize elastic fiber, skin sections were stained by Verhoff van Geison staining, which is most commonly used for visualizing elastic fibers.

2.3 Atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging

Human skin biopsies were embedded in OCT, and cryosections (15 μm thick) were attached to microscope cover glass (1.2 mm diameter, Fisher Scientific Co., Pittsburgh, PA). These AFM samples were allowed to air dry for at least 24 hours before analysis. Nanoscale AFM images were obtained in the air by Dimension Icon AFM system (Bruker-AXS, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) using a silicon AFM probe (PPP-BSI, force constant 0.01–0.5N/m, resonant frequency 12–45kHz, 10-nm-radius, NANOSENSORS™, Switzerland). AFM images of the collagen fibrils were acquired using ScanAsyst mode, an optimized PeakForce Tapping technique that provides high resolution AFM images. ScanAsyst mode visualize automatically and continuously monitors image quality and makes appropriate parameter adjustments. AFM images of the elastotic material were acquired using Peak Force QNM mode. For each subject, AFM images were obtained from 9 different regions of each skin section (108 total scans, 5×5μm scan size), which included the ECM in both the reticular and papillary dermis, as shown in Figure 2A. AFM images were obtained with a 512 × 512-pixel resolution. The surface roughness of the scanned regions was calculated as the roughness average (Ra), which is typically used to describe the roughness of materials’ surfaces and is calculated by a surface’s measured microscopic peaks and valleys. The Ra of the scanned regions was quantified from raw data, without modifications, such as cleaning, flattening, filtering, or plane fitting, using Nanoscope Analysis software (Nanoscope Analysis v120R1sr3, Bruker-AXS, Santa Barbara, CA, USA). Ra of photodamaged or sun-protected dermal ECM was calculated from 54 AFM scans from each group (9 scans/sample × total 6 subjects=54 scans/group). AFM was conducted at the Electron Microbeam Analysis Laboratory (EMAL), University of Michigan College of Engineering.

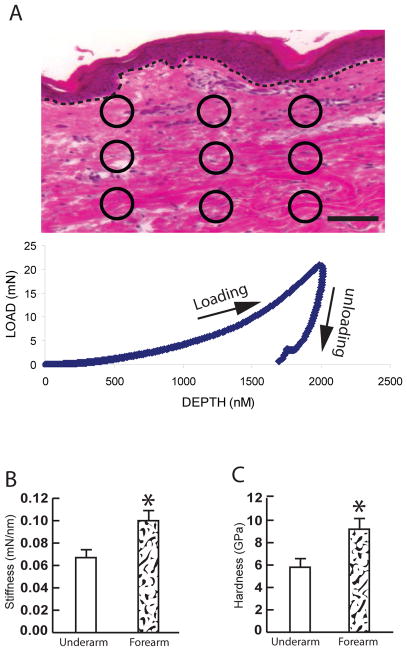

Fig 2. Increased mechanical properties in the photodamaged dermis.

(A) Representative image for quantification of mechanical properties by Nano indentation. Total of nine indents, as indicated by circles, per skin section were obtained. The graph represents typical load (mN) and displacement (penetration depth, nm) curve (see Methods for details). Dot lines indicate epidermal and dermal junction. Bar=100μm. (B) Increased stiffness in photodamaged forearm dermis. (C) Increased hardness in photodamaged forearm dermis. Stiffness and hardness were quantified using a NanoIndenter II (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), as described in Methods. Quantification of the dermal mechanical properties was obtained from total 54 indents from each group (9 indents/subject × total 6 subjects=54 indents/group). Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM,*p < 0.05.

2.4 Nanoindentation measurements

Human skin biopsies were embedded in OCT and cryosectioned (100 μm thick). These sections were attached to microscope cover glass (1.2 mm diameter, Fisher Scientific Co., Pittsburgh, PA), and were allowed to air dry for at least 24 hours before nanoindentation. Mechanical properties (stiffness, hardness, and Young’s modulus) were measured by nanoindentation using a NanoIndenter II (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), in the constant displacement rate loading mode with a three-sided pyramidal diamond tip. A fused quartz sample with known hardness and Young’s modulus values was used as a reference sample. The maximum indentation displacement was controlled to be 2000nm. The method used to calculate the stiffness and the hardness modulus was based on established methods 17, 18. A total of 9 indents per skin section were obtained from different regions of the reticular and papillary dermis (Fig 3A). Quantification of the dermal ECM mechanical properties was obtained from 54 indents from photodamaged or sun-protected skin sections (9 indents/sample × total 6 subjects=54 indents/group).

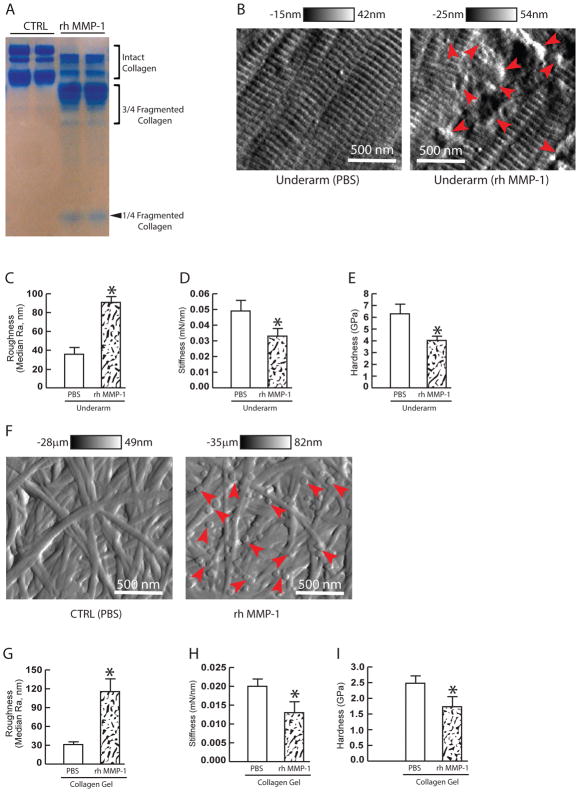

Fig 3. Fragmented collagen fibrils contribute to rougher collagen surface, but no to stiffer and harder dermis in the photodamaged dermis.

(A) rhMMP-1 induced collagen fragmentation. Rat tail type I collagen was treated with activated rhMMP-1 (30 ng/ml) at 37 °C for overnight. Collagen fragmentation was determined by SDS–PAGE stained with SimplyBlue (see Method for detail). (B) rhMMP-1 induced collagen fragmentation in the underarm skin. the underarm skin was treated with activated rhMMP-1 (30 ng/ml) at 37 °C for overnight. Collagen fragmentation was analyzed by AFM. Red arrows indicate fragmented collagen fibrils. Horizontal black and white bars on the top indicate height. Images are representative of six subjects. (C) Collagen fibrils roughness was increased in rhMMP-1 treated underarm skin. Collagen fragmentation has no effect on (D) dermal stiffness and (E) hardness. (F) rhMMP-1 induced collagen fragmentation in 3D collagen gel. 3D collagen gel was treated with activated rhMMP-1 (30 ng/ml) at 37 °C for overnight. Collagen fragmentation was analyzed by AFM. Red arrows indicate fragmented collagen fibrils. Horizontal black and white bars on the top indicate height. Images are representative of three independent experiments. (G) Collagen fibrils roughness was increased in rhMMP-1 treated 3D collagen gel. Collagen fragmentation has no effect on (H) 3D collagen gel stiffness and (I) hardness. Collagen fibrils roughness was analyzed using Nanoscope Analysis software (Nanoscope_Analysis_v120R1sr3, Bruker-AXS, Santa Barbara, CA) and stiffness and hardness were quantified using a NanoIndenter II (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), as described in Methods. Quantification of the collagen surface roughness and dermal mechanical properties was obtained from total 54 AFM images and indents, respectively (9 AFM images or indents/subject × total 6 subjects=54 AFM images or indents/group). Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, *p < 0.05.

2.5 RNA isolation and quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Total skin RNA was extracted using the RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA template for PCR amplification was prepared by reverse transcription of total RNA (200 ng) using TaqMan Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Real-time PCR quantification was performed on a 7300 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All LOX family of proteins PCR primers were purchased from RealTimePrimers.com (Real Time Primers, LLC, Elkins Park, PA,USA). Target gene mRNA expression levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene 36B4 as an internal control for quantification.

2.6 Treatment of 3D collagen gels and underarm skin samples with rhMMP-1

3D collagen gels were prepared as previously described 19, with minor modification. Briefly, neutralized rat tail type-I collagen (2mg/ml, BD, Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was suspended in the medium cocktail (DMEM, NaHCO3 [44 mM], L-glutamine [4 mM], Folic Acid [9 mM], and neutralized with 1N NaOH to pH 7.2. Collagen and medium cocktail solution were placed in 35 mm bacterial culture dishes. The collagen gels were placed in an incubator at 37°C for 30 minutes to allow collagen polymerization. The collagen gels were then incubated with 2 ml media (DMEM, 10% FBS) at 37°C, 5% CO2 overnight. rhMMP-1 (R&D, Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was diluted to 50μg/mL, and activated by adding APMA to a final concentration of 1 mM. The collagen gels were treated with activated rhMMP-1 (30 ng/ml) overnight at 37°C, and the media were collected, concentrated, and analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE. Collagen bands were visualized by staining with SimplyBlue (Invitrogen Life Technology, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For human skin samples, 4 mm punch biopsies of sun-protected underarm skin were obtained, as described above. The skin biopsies were cut into small pieces (4 pieces/biopsy) and incubated for 48 hours in Ca2+-supplemented (1.4 mM final concentration) keratinocyte basal medium (KBM) (MA Bioproducts, Walkersville, MD, USA). These culture conditions preserve the histological structure and biochemical function of human skin at least until seven days 20. The biopsies were then treated with activated rhMMP-1 (30 ng/ml) at 37°C for overnight. At the end of the incubation period, the biopsies were embedded in OCT, and cryosections (15 μm) were analyzed by AFM, as described above.

2.7 Charts, figures, and statistics

Charts and figures were generated with Microsoft Excel 2010 and Adobe Illustrator, respectively. Bar graphs represent Means±SEM. Comparisons between samples were performed with the paired t-test (two groups) or the repeated measures of ANOVA (more than two groups). All p-values are two-tailed, and considered significant when <0.05 (depicted by asterisks on figures).

3. Results

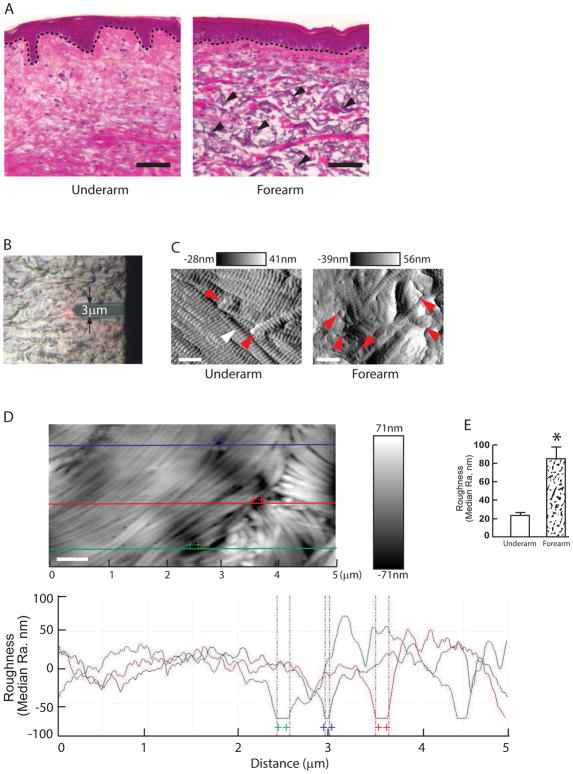

3.1 Dermal collagen fibrils are more disorganized (greater surface roughness) in photodamaged, compared to sun-protected skin

Figure 1A shows conventional histological images of human skin (H&E staining). In the sun-protected underarm, the bundles of collagen fibers are densely packed and well-organized (Fig 1A, left panel). In contrast, sun-exposed photodamaged forearm shows disorganized collagen bundles (Fig 1A, right panel). In addition to the aberrant organization of collagen bundles, photodamaged forearm shows significant elastosis (arrows), which is a hallmark of photodamaged skin.

Fig 1. Increased collagen surface roughness in the photodamaged dermis.

(A) Optical microscopy image of the photodamaged forearm (right panel) and subject-matched sun-protected underarm dermis (left panel). Skin sections are stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Dotted lines indicate epidermal and dermal junction. Arrowheads indicate elastosis (right panel). Images are representative of six subjects. Bar=100μm. (B) Representative bright field image shows the AFM cantilever positioned on the dermis. (C) Nanoscale images of the collagen fibrils from sun-protected underarm (left panel) and photodamaged forearm (right panel) were taken by AFM. White and red arrows indicate intact and fragmented collagen fibrils, respectively. Horizontal black and white bars on the top indicate height. A total of nine images were taken from per subject. Images are representative of six subjects. Bar=500 nm. (D) Representative image for quantification of collagen surface roughness. Lateral dimension is 5x2.5 μm2. Height is given in black and white brightness. The lines indicate cross sections that are displayed below by graph. Each line (purple, red, and green) height fluctuations in the graph indicate corresponding collagen surface roughness of the upper image. Bar=500 nm. (E) Collagen fibrils roughness was increased in photodamaged forearm dermis. Quantification of the surface roughness was obtained from total 54 AFM images from each group (9 images/subject × total 6 subjects=54 images/group). Collagen fibrils’ roughness was analyzed using Nanoscope Analysis software (Nanoscope_Analysis_v120R1sr3, Bruker-AXS, Santa Barbara, CA). Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM, *p< 0.05.

Next, we analyzed nanostructures of the dermal collagen fibrils by AFM (Fig 1B). AFM provides both nanoscale imaging and quantitative physical properties material surfaces. In the sun-protected underarm (Fig 1C, left panel), intact collagen fibrils are abundant, tightly packed, laterally aligned and display characteristic d-bands. In contrast, collagen fibrils in photodamaged forearm dermis lack these features and are generally disorganized (Fig 1C, right panel). To measure collagen fibrils organization, we quantified the surface roughness based on the height profiles of the collagen fibrils cross-section. Surface roughness is a component of surface texture measured by Ra (roughness average), which is calculated as the mean deviation of height over the entire measured area. Large deviations indicate a rough surface, while small deviations denote a smooth surface. Figure 1D shows a typical topographical image (top) and corresponding height profile (bottom) of collagen fibrils. Quantitative analysis indicated that the roughness (Ra) of dermal collagen fibrils in the photodamaged forearm (85nm±13.2) was significantly greater, compared to sun-protected underarm (23.3 nm±3.3) (Fig 1E).

3.2 Dermal ECM is stiffer and harder in photodamaged, compared to the sun-protected skin

We next used nanoindentation technology to measure two key related mechanical properties of the dermal ECM, stiffness and hardness 21, 22. Stiffness is a measure of the resistance of an object to deformation by an applied force. Hardness is a measure of the resistance of a material to localized permanent (plastic) deformation. For each sample, nanoindentation measurements were made at nine different sites throughout the dermis (Fig 2A, upper panel). Figure 2A (bottom panel) shows a typical load displacement curve obtained for a single site in sun-protected dermis. Interestingly, the average stiffness (Fig 2B) and hardness (Fig 2C) of the dermal ECM in photodamaged forearm skin were increased by 152% and 158%, respectively, compared to the dermal ECM in sun-protected underarm skin.

3.3 Fragmentation of dermal collagen fibrils increases fibril disorganization (surface roughness) and reduces ECM stiffness and hardness

The above data demonstrate that the dermal ECM in photodamaged skin has more disorganized (rougher surface) collagen fibrils and is stiffer and harder, compared to sun-protected skin. Next, we explored the potential mechanisms that alter the physical properties of photodamaged skin. Collagen fibrils comprise the bulk of the dermis and are fragmented in photodamaged skin by the actions of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which are induced by UV irradiation. Therefore, we treated sun-protected underarm skin ex vivo with purified recombinant human MMP-1(rh MMP-1), which initiates cleavage of collagen fibrils, generating one quarter and three-quarter length fragments 23, 24 (Fig 3A). AFM analysis revealed significant fragmentation and disorganization of collagen fibrils in the dermal ECM of sun-protected skin following treatment with MMP-1 (Fig 3B and 3C), similar to that observed in photodamaged forearm dermal ECM (Fig 1C and 1E). Collagen fibril fragmentation increased surface roughness by 2.5-fold (90.8nm vs 35.7nm in control underarm skin). In contrast, MMP-1-mediated collagen fragmentation resulted in decreased dermal stiffness (Fig 3D) and hardness (Fig 3E).

We next employed three dimensional type I collagen lattices to confirm the above data. Consistent with the above data, MMP-1-mediated collagen fibril fragmentation of collagen lattices resulted in rougher collagen fibril surface (Fig. 3F and 3G), and decreased stiffness (Fig 3H) and hardness (Fig 3I). These data suggest that fragmentation of collagen fibrils contributes to collagen fibril disorganization (rougher surface), but does not contribute to stiffer and harder mechanical properties of the dermal ECM in the photodamaged skin.

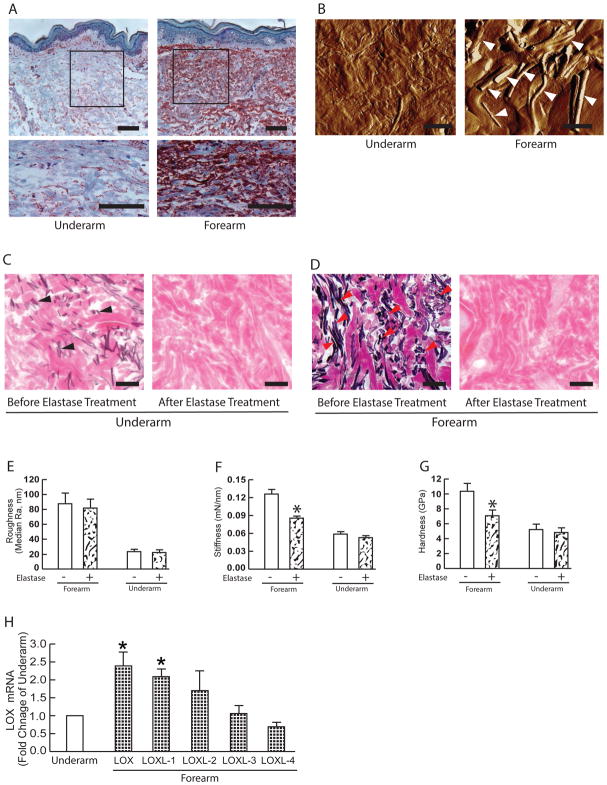

3.4 Elastosis contributes to increased stiffness and hardness in photodamaged skin

We next examined the role of solar elastosis in altered physical properties in photodamaged skin. Solar elastosis involves deposition of abnormal elastin-containing material in the upper dermis, in photodamaged skin. As shown in Figure 4A, photodamaged forearm displays a significantly more elastosis, compared to underarm skin. AFM images with distinctive strand-shaped material (Fig 4B, right panel indicated by arrows). We investigated the impact of removing elastotic material on the physical properties of the dermal ECM in photodamaged forearm and sun-protected underarm skin. Dermal elastotic material was removed from frozen skin sections by treatment with purified neutrophil elastase, which degrades elastin fibers and elastotic material. Elastase treatment resulted in removal of the elastotic material in both sun-protected underarm skin (Fig 4C) and in photodamaged forearm skin (Fig 4D). Removal of elastotic material did not alter dermal collagen fibril organization (surface roughness) in photodamaged forearm or sun-protected underarm (Fig 4E). Similarly, no change in dermal ECM stiffness (Fig. 4F) or hardness (Fig. 4G) were observed in sun-protected underarm skin. In contrast, removal of elastotic material reduced dermal ECM stiffness (Fig 3F, reduced 42%) and hardness (Fig 3G, reduced 43%), in photodamaged forearm skin.

Fig 4. Elastosis contributes to altered mechanical properties, but not to rougher collagen surface in the photodamaged dermis.

(A) Tropoelastin immunostaining from sun-protected underarm (left panel) and photodamaged forearm dermis (right panel). Images are representative of six subjects. Bar=100μm. 2.5x enlargement of the boxed region is shown. (B) AFM images of sun-protected underarm (left panel) and photodamaged forearm dermis (right panel). Arrowheads indicate elastin fibers. Images are representative of six subjects. Bar=10μm. (C) Verhoff van Geison staining of underarm skin sections before (left) and after (right) treatment with purified neutrophil elastase to remove elastotic materials. Images are representative of six subjects. Bars = 100μm. (D) Before (left) and after (right) removal of dermal elastosis. Verhoff van Geison staining of photodamaged forearm skin sections before (left) and after (right) treatment with purified neutrophil elastase to remove elastotic materials. Images are representative of six subjects. Bars = 100μm. (E) Collagen fibril surface roughness, (F) Stiffness, and (G) Hardness before and after removal of elastotic material. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Each group comprised six subjects, a total of nine indents were measured from per subject. *p < 0.05. (H) Alteration of LOX family mRNA expression in the photodamaged human skin in vivo. Skin dermis was prepared by cutting off epidermis at a depth of 1 mm by cryostat. Total RNA was extracted from the dermis and the expression of LOX family mRNA was quantified by real-time RT-PCR. LOX family mRNA levels were normalized to the housekeeping gene 36B4, as an internal control for quantification, and expressed relative to the underarm. Mean±SEM. Each group comprised six subjects. *p < 0.05.

3.5 Elevated LOX expression in the photodamaged dermis

Cross-linking of ECM proteins influences tissue mechanical properties 25, 26. Therefore, we investigated the expression of LOX family of proteins, which modify the side-chain of lysyl residues in collagen and elastin, thereby catalyzing covalent crosslinking. This crosslinking of collagen fibrils and elastin fibers increases stiffness and tensile strength. LOX family is comprised of five paralogues: LOX and LOX-like 1–4 (LOXL1–4)27. To determine LOX family gene expression in the dermis, the upper 1mm of skin, including epidermis and superficial dermis was removed by cryostat. Among five the LOX family members, mRNA expression of LOX and LOXL1 was elevated in photodamaged forearm dermis 2.4-fold and 2.1-fold, respectively (Fig 4H), compared to sun-protected underarm dermis. These data suggest that elevated LOX and LOXL1 may contribute to stiffer and harder mechanical properties of the dermal ECM by increasing collagen and elastin crosslinking in photodamaged skin.

4. Discussion

Skin possesses unique biomechanical properties that play an important role in protection against physical impact from the environment. The most predominant structural components of the dermis are collagen fibrils and elastin fibers, and their properties largely determine the biomechanical properties of the skin. We find that dermal collagen fibrils in photodamaged skin are more disorganized (rougher surface) and the dermal ECM is stiffer and harder, compared to sun-protected underarm skin. Our results show that dermal collagen fragmentation contributes to increased collagen fibril disorganization, while solar elastosis contributes to increased dermal ECM stiffness and hardness, in photodamaged dermis. It should be noted that due to technical constraints our measurements of the mechanical properties of the dermal ECM were made on air-dried skin samples. Therefore, the values we obtained for stiffness and hardness do not necessarily correspond to those of fully hydrated skin in vivo. However, given that the hydration state of all skin samples was similar, the observed differences between sun-protected and photodamaged skin reflect inherent relative differences of mechanical properties.

Dermal collagen fibrils in young, sun-protected skin are densely packed and highly ordered in three dimensional space. Fragmentation of fibrils by MMPs, which are induced by UV irradiation, reduces both fibril density and order. Therefore, fibril fragmentation in photodamaged skin would be expected to increase fibril disorganization. AFM is powerful tool to examine nanoscale surface structures and indeed AFM revealed that dermal collagen fibril disorganization, measured as fibril surface roughness, was increased in photodamaged skin. Although AFM has been extensively used during the last years in life sciences 31, its application in clinical human tissue samples is still very limited. The results from AFM nanoscale measurement of collagen fibrils surface roughness/organization are consistent with data from the conventional H&E histology. However, it is impossible to obtain quantitative nanoscale measurements of collagen fibril organization from conventional histology. AFM analysis demonstrated detailed nanoscale changes in collagen fibrils, such as loosening and separation of collagen fibrils from fibril bundles, fragmentation of collagen fibrils, and disintegration and disordering of collagen fibrils in photodamaged skin. Our results demonstrate the usefulness of AFM and nanoindentation for nanoscale morphological and biophysical studies of clinical human tissue samples. AFM and nanoindentation can be applied without prior fixation and embedding of tissue samples and therefore may preserve native tissue structure and mechanical properties better than conventional ultrastructural microscopy. In addition, AFM and nanoindentation can provide valuable information from very small volumes of native tissue, such as a fine-needle aspiration biopsy.

The precise process by which solar elastosis contributes to stiffer and harder dermal ECM remains to be determined. Elastotic material is composed of tropoelastin, additional elastin fiber components, and other proteins. Elastin is insoluble, and AFM suggests that elastotic material forms rigid strands. Elastotic material may be inherently stiffer and harder than the collagenous ECM. Additionally, space filling by elastotic material may cause compaction of the dermal ECM, thereby resulting in increased stiffness and hardness.

The observed elevated expression of ECM-crosslinking enzymes, LOX and LOXL-1 may also contribute to increased stiffness and hardness of the dermal ECM in photodamaged skin. Mounting evidence reveals that the mechanical properties of connective tissue microenvironment are largely influenced by LOX family of proteins 25, 26. For example, LOX protein expression is elevated in many types of tumors, and functions as a significant contributor to tumor matrix stiffening, which leads to enhanced invasiveness 27, 28. Additionally, non-enzymatic collagen glycation, so-called advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), could influence the mechanical properties of photodamaged skin 29. However, currently there is no direct evidence linking AGEs with increased mechanical stiffness in human skin in vivo, although the glycation of collagen results in stiffening of matrices in vitro 30.

The ECM microenvironment provides cells with both chemical and mechanical signals 32. The mechanical properties of the ECM microenvironment are critically important in controlling fundamental cell functions 33–35. For example, ECM stiffness can control differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into distinct lineages and tumorigenesis 36, 37. We found that the dermal ECM in photodamaged skin is stiffer and harder compared to the sun-protected skin. In general, stiffer and harder ECM microenvironments increase cellular biomechanics pathways and cell activation 32. Dermal fibroblasts behave in this way to mechanical inputs 16, 38. We and others have reported that stiffer collagen lattices stimulate spreading, proliferation, and ECM production by dermal fibroblasts 16, 38. Importantly, the ability of ECM to influence cellular behavior is dependent on physical attachment of the cells to the ECM. Attachment allows cells to receive and respond to mechanical cues from the surrounding ECM. In photodamaged skin, collagen fibril fragmentation removes fibroblast attachment sites (fibroblasts cannot attach to fragmented collagen), thereby mitigating the mechanical influences of the stiffer dermal ECM. This reduced attachment accounts for, reduced spreading and decreased ECM production by dermal fibroblasts in photodamaged skin, in spite of the stiffer dermal ECM microenvironment.

In summary, photodamage alters the mechanical properties of the dermal ECM via multiple, counteracting mechanisms. Collagen fragmentation reduces fibril organization, stiffness, hardness, and fibroblast-ECM attachment. Solar elastosis and LOX family enzymatic cross-linking increase dermal ECM stiffness and hardness. The mechanisms that result in stiffening of the dermal ECM compensate to some extent for the softening.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health (AG19364 to T Quan and GJ Fisher and ES014697 to T Quan).

Abbreviations

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- UV

ultraviolet

- LOX

lysyl oxidase

- AFM

atomic force microscopy

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: JV, GF, TQ

Formal analysis: TQ

Funding acquisition: GF, TQ

Investigation: YS, ZQ, JAW, RMB, TQ

Project administration: TQ

Methodology: JV, GF, TQ

Resources: TQ

Supervision: TQ

Writing (original draft): TQ

Writing (review & editing): JAW, GF, JV, TQ

References

- 1.Fisher GJ, Wang ZQ, Datta SC, Varani J, Kang S, Voorhees JJ. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1419–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uitto J, Fazio MJ, Olsen DR. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;21:614–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uitto J, Bernstein EF. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1998;3:41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uitto J. Dermatol Clin. 1986;4:433–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher GJ, Varani J, Voorhees JJ. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:666–672. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.5.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quan T, Fisher GJ. Gerontology. 2015;61:427–434. doi: 10.1159/000371708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quan T, Little E, Quan H, Qin Z, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1362–1366. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quan T, Qin Z, Xia W, Shao Y, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2009;14:20–24. doi: 10.1038/jidsymp.2009.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eaglstein WH. Dermatol Clin. 1986;4:481–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bissell MJ, Hines WC. Nat Med. 2011;17:320–329. doi: 10.1038/nm.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bissell MJ, Kenny PA, Radisky DC. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2005;70:343–356. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:395–406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosh K, Capell BC. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.06.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Straussman R, Morikawa T, Shee K, Barzily-Rokni M, Qian ZR, Du J, Davis A, Mongare MM, Gould J, Frederick DT, Cooper ZA, Chapman PB, Solit DB, Ribas A, Lo RS, Flaherty KT, Ogino S, Wargo JA, Golub TR. Nature. 2012;487:500–504. doi: 10.1038/nature11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fisher GJ, Esmann J, Griffiths CE, Talwar HS, Duell EA, Hammerberg C, Elder JT, Finkel LJ, Karabin GD, Nickoloff BJ, et al. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:699–707. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12470632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quan T, Shao Y, He T, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:415–424. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oliver WC, Pharr GM. J Mater Res. 1992;7:1564–1583. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhushan B, Li XD. Int Mater Rev. 2003;48:125–164. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Qin Z, Voorhees JJ, Fisher GJ, Quan T. Aging Cell. 2014;13:1028–1037. doi: 10.1111/acel.12265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varani J, Perone P, Griffiths CE, Inman DR, Fligiel SE, Voorhees JJ. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1747–1756. doi: 10.1172/JCI117522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baumgart E. Injury. 2000;31(Suppl 2):S-B14-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silver FH, Siperko LM, Seehra GP. Skin Res Technol. 2003;9:3–23. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0846.2003.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fields GB. J Theor Biol. 1991;153:585–602. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gross J, Harper E, Harris ED, McCroskery PA, Highberger JH, Corbett C, Kang AH. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1974;61:605–612. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(74)91000-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barry-Hamilton V, Spangler R, Marshall D, McCauley S, Rodriguez HM, Oyasu M, Mikels A, Vaysberg M, Ghermazien H, Wai C, Garcia CA, Velayo AC, Jorgensen B, Biermann D, Tsai D, Green J, Zaffryar-Eilot S, Holzer A, Ogg S, Thai D, Neufeld G, Van Vlasselaer P, Smith V. Nat Med. 2010;16:1009–1017. doi: 10.1038/nm.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, Fong SF, Csiszar K, Giaccia A, Weninger W, Yamauchi M, Gasser DL, Weaver VM. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barker HE, Cox TR, Erler JT. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:540–552. doi: 10.1038/nrc3319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cox TR, Bird D, Baker AM, Barker HE, Ho MW, Lang G, Erler JT. Cancer Res. 2013;73:1721–1732. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snedeker JG, Gautieri A. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4:303–308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mason BN, Reinhart-King CA. Organogenesis. 2013;9:70–75. doi: 10.4161/org.24942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parot P, Dufrene YF, Hinterdorfer P, Le Grimellec C, Navajas D, Pellequer JL, Scheuring S. J Mol Recognit. 2007;20:418–431. doi: 10.1002/jmr.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butcher DT, Alliston T, Weaver VM. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:108–122. doi: 10.1038/nrc2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iskratsch T, Wolfenson H, Sheetz MP. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:825–833. doi: 10.1038/nrm3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:786–801. doi: 10.1038/nrm3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Humphrey JD, Dufresne ER, Schwartz MA. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15:802–812. doi: 10.1038/nrm3896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ingber DE. FASEB J. 2006;20:811–827. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5424rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mammoto T, Mammoto A, Ingber DE. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2013;29:27–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher GJ, Shao Y, He T, Qin Z, Perry D, Voorhees JJ, Quan T. Aging Cell. 2016;15:67–76. doi: 10.1111/acel.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]