Abstract

Background:

Kidney transplant is the best treatment for most end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients, but proportionally few ESRD patients receive kidney transplant. To make an informed choice about whether to pursue kidney transplant, patients must be knowledgeable of its risks and benefits. To reliably and validly measure ESRD patients’ kidney transplant knowledge, rigorously tested measures are required. This paper describes the development and psychometric testing of the Knowledge Assessment of Renal Transplantation (KART).

Methods:

We administered 17 transplant knowledge items to a sample of 1,294 ESRD patients. Item characteristics and scale scores were estimated using an item response theory (IRT) graded response model. Construct validity was tested by examining differences in scale scores between patients who had spent < 1 and ≥ 1 hour receiving various types of transplant education.

Results:

IRT modelling suggested that 15 items should be retained for the KART. This scale had a marginal reliability of 0.75 and evidenced acceptable reliability (>0.70) across most of its range. Construct validity was supported by the KART’s ability to distinguish patients who had spent < 1 and> 1 hour receiving different types of kidney transplant education, including talking to doctors/medical staff [effect size (ES) = 0.61; p<0.001], reading brochures (ES = 0.45; p<0.001), browsing the internet (ES = 0.56; p<0.001), and watching videos (ES = 0.56; p<0.001).

Conclusions:

The final 15-item KART can be used to determine the kidney transplant knowledge levels of ESRD patients and plan appropriate interventions to ensure informed transplant decision-making occurs.

Introduction

There are over 700,000 prevalent cases of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States and approximately 100,000 new incident cases yearly.1 An overwhelming body of research has demonstrated that kidney transplantation is superior to dialysis due to the longer and higher quality life it imparts,1–3 but most ESRD patients still remain on dialysis. Patients remaining on dialysis and patients presenting for transplant are uninformed of their option for transplant,4 have suboptimal levels of transplant knowledge, or believe myths about transplant, due to a lack of accurate information about its benefits and risks.5,6 These barriers may be more severe for racial and ethnic minorities, and likely play an important role in the continued disparities in receipt of living donor kidney transplant (LDKT).7

For these reasons, improving transplant knowledge and informed decision-making for all kidney patients is critical. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires that dialysis patients be informed of their option for transplant within the first 45 days of starting treatment.8 Several transplant education programs have been developed over the last decade to help inform dialysis and patients seeking transplant about the risks and benefits of getting a transplant.9–16 Though significant progress has been made by these programs, access to transplant is still lower than desired, and additional improvement of transplant education interventions is needed.7 It is critically important for interventions to utilize reliable and valid transplant knowledge instruments in order to accurately characterize these interventions’ effects. To date, few measures of kidney transplant knowledge have been developed and published.17 Therefore, this study aimed to develop and validate a new transplant knowledge scale.

Methods and Materials

Datasets

This study used data from 2 randomized controlled trials with dialysis and patients presenting for transplant evaluation. The study protocols were published elsewhere.9,18 In both studies, knowledge of kidney transplant was assessed before and after administration of the interventions. Only the baseline assessment from each of these studies was used so that transplant knowledge levels observed in these data are not biased by the interventions. The first study (Study 1) was conducted with English-speaking, Black, White, and Hispanic adults (18+) who contacted the UCLA Kidney Transplant Program to begin evaluation for kidney transplant between May 2014 and March 2017. Study 1 contributed 733 patients to the analysis sample. The second study (Study 2) was conducted with English-speaking, Black and White adult (18+) dialysis patients in dialysis centers throughout Missouri between 2014 and 2016. Study 2 contributed 561 patients to the analysis sample, resulting in a total of 1,294 patients for the analyses. The UCLA Institutional Review Board approved the protocols used to collect the data in both studies (Study 1:#14–000382; Study 2: #14–000802) and both trials were registered with http://ClinicalTrials.gov (Study 1: NCT02181114; Study 2: NCT02268682).

Transplant Knowledge Items

Seventeen transplant knowledge items were administered to participants by a research coordinator over the telephone in each study. (Table 1.) On average, it took 5–10 minutes to complete the measure. Ten of the items had “True/False/Don’t Know” response options and 7 had multiple choice, each of which also included a “Don’t Know” option. Item development involved a multidisciplinary, clinical and academic team of nephrologists, dialysis staff, and psychologists with expertise in kidney disease and patient-reported health measure development. After a systematic review of the literature and formative qualitative19 and quantitative20 research with previous transplant recipients, each item was written by A.D.W. Items were written to specifically address questions important to kidney patients in the formative research (eg, likelihood of negative impact on living kidney donors covered by items I1 and I17 [see Table 1.]) Then, each item was reviewed for relevance and appropriateness by the expert team. In addition, each item was reviewed for relevance and understandability by a racially diverse panel of kidney patients, including kidney transplant recipients and dialysis patients. Each item asks about a benefit, risk, or general fact about kidney transplantation. For this paper, each item’s response was recoded as 0 = “Don’t Know”, 1 = “Incorrect”, and 2 = “Correct.” Items with missing responses were left missing and not assigned any other value. This coding orders responses to each item from the lowest transplant knowledge ability (does not know the answer) to the highest ability (correct answer).

Table 1.

Starting Set of Kidney Transplant Knowledge Items and Distribution of Responses

| Item (Number) | Included in 15-item KART? | Response Options | Correct % (n) |

Incorrect % (n) |

Don’t Know % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After they donate, living donors lose ½ of their kidney functioning for the rest of their lives. (I1) | Yes | T, F, DK | 54% | 34% | 12% |

| Getting a transplant is a cure for kidney disease. (I2) | No | T, F, DK | 53% | 43% | 4% |

| A patient on dialysis has the same level of kidney functioning as a patient with a transplanted kidney. (I3) | Yes | T, F, DK | 78% | 12% | 10% |

| Patients older than 75 years can receive transplants. (I4) | No | T, F, DK | 43% | 37% | 20% |

| The transplant team will let a living donor back out from donating on the day of surgery. (I5) | Yes | T, F, DK | 53% | 30% | 17% |

| In general, patients can live at least 5 years longer with a kidney transplant than if they stayed on dialysis. (I6) | Yes | T, F, DK | 65% | 21% | 14% |

| In general, most people on dialysis are happier with the quality of their lives than people with transplants. (I7) | Yes | T, F, DK | 78% | 13% | 9% |

| Patients have better health outcomes if they receive a transplant before starting dialysis. (I8) | Yes | T, F, DK | 48% | 30% | 22% |

| After a patient is listed, they don’t need to return to the transplant center again until a matching kidney from someone who has died is available. (I9) | Yes | T, F, DK | 61% | 25% | 14% |

| If a patient waits long enough on the wait list, a matching kidney from someone who has died will definitely become available. (I10) | Yes | T, F, DK | 43% | 48% | 9% |

| About what percentage of all transplanted kidneys function for at least 1 year? (I11) | Yes | 50%, 75%, 90%, DK | 34% | 48% | 18% |

| Nationally, how long do patients generally wait on the waiting list for a kidney from someone who has died? (I12) | Yes | <1 yr, 1–2 yr, 3–5 yr, >5 yr, DK | 31% | 59% | 10% |

| How long have doctors been doing transplants using living donors? (I13) | Yes | 2 yr, 10 yr, 25 yr, >50 yr, DK | 28% | 52% | 20% |

| Compared to transplants from donors who have died, how long do transplants from living donors last? (I14) | Yes | Shorter, Longer, Same, DK | 40% | 44% | 16% |

| After a transplant, how long does the US Government pay for most of the costs of transplant medications? (I15) | Yes | 1 yr, 3 yr, 10 yr, Rest of life, DK | 18% | 53% | 29% |

| Do donors have to pay for testing and hospitalization related to kidney donation? (I16) | Yes | Yes, No, DK | 65% | 18% | 17% |

| What is the chance that a living donor or recipient would die while undergoing transplant surgery? (I17) | Yes | <1%, 3%, 10%, 25%, DK | 41% | 40% | 19% |

Correct responses are bolded. T = True, F = False, DK = Don’t know

Other Study Measures

In addition to the transplant knowledge items, we asked participants’ demographic characteristics including race/ethnicity, gender, age, level of education, type of health insurance, and whether the patient was on dialysis. Previous access to transplant education was assessed, including whether the patient had read brochures, watched videos, browsed the internet, or talked to their doctor/medical staff about transplant. Patients were asked whether they had ever received each type of transplant education material (“yes/no”), and, if they responded “yes”, how many hours they had spent on each. For each type, we dichotomized responses as having spent < 1 hour vs. ≥ 1 hours, excluding patients who said they did not receive each type of education previously. We also assessed health literacy with 2 items. The first asks patients how often they require help reading hospital materials. Responses were dichotomized into “None of the Time” vs. “A little, some, most, or a lot of the time”. The second item asks patients how confident they are filling out medical forms. Responses were dichotomized into “Extremely confident” vs. “Quite a bit, somewhat, a little bit, not at all confident.”21

Transplant Knowledge Scale Evaluation

Item Response Theory (IRT) was used to assess the transplant knowledge items. Use of IRT offers several benefits, including being able to estimate the reliability of the scale at different locations along the underling knowledge continuum. We implemented a graded response model21–22 that yields an estimate of transplant knowledge (mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1), with higher scores indicating higher knowledge. The model also estimates item difficulty thresholds (b), defined as the location on the knowledge continuum where there is a 50% probability of answering below vs. above the threshold. Since the transplant knowledge items in this paper each have 3 response categories, each item has 2 b parameter estimates, one where the probability is 50% for selecting “Don’t Know” versus “Incorrect” or “Correct” (b1) and one where the probability is 50% for selecting “Don’t Know” or “Incorrect” versus “Correct” (b2). For example, an item with b1 = −1 and b2 =1 has a difficultly such that respondents with transplant knowledge ability 1 standard deviation below the mean have a 50% probability of answering “Don’t know” vs. giving an incorrect or correct response, and those with a transplant knowledge of 1 standard deviation above the mean have a 50% probability of answering “Don’t know” or giving an incorrect response vs. a correct response.

A second item parameter, the discrimination parameter (a), indicates how well items differentiate between patients of lower and higher levels of knowledge (theta), with higher values indicating better discrimination. The discrimination parameter can also be presented in the more familiar factor loading metric. Item characteristic curves with the latent trait estimate (theta) on the x axis and the probability of response for each response category on the y axis are used to evaluate the performance of each response option. Each response category should have the highest likelihood of being selected somewhere along the underlying knowledge distribution and the location on the continuum where response categories are most likely to be chosen should support a monotonic relationship with theta.

Model parameters were estimated using full-information maximum likelihood estimation. After estimating item parameters using the graded response model, items with low discrimination (low factor loadings) were dropped. Model fit was assessed with Akaike’s information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). For both statistics, lower values indicate better model fit. The scale reliability is estimated by the model directly.

A key assumption of unidimensional IRT models is that all the items represent a single underlying construct. As an initial test of unidimensionality, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) including all items and examined the ratio of the first eigenvalue to the second. Ratios of >4 indicate unidimensionality.22 In addition, unidimensionality was assessed with a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model wherein each item loaded onto a single factor. The CFA was fit in Mplus version 8, using weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment estimation for categorical items.23 We took good model fit as evidence of unidimensionality. Model fit was defined as a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value of <0.06 and a comparative fit index (CFI) value of >0.90.24 A second key assumption is of IRT monotonicity, or that the probability of responding with higher response categories increases with higher levels of the underlying trait. In this context, we tested the hypothesis that patients with lower to higher underlying levels of transplant knowledge would have increasing probabilities of selecting incorrect responses vs. responding “don’t know,” then of selecting correct responses vs. incorrect responses. This hypothesis was tested for each item by regressing the sum of all items on each item separately and examining Duncan multiple range tests, a posthoc means comparison test applied after 1 way ANOVA that helps determine rank ordering of means. For these tests, we took significant differences of means with ordering such that patients who gave “Don’t Know” responses had the lowest means and those with “Correct” responses had the highest means. The monotonicity assumption would be evidenced if patients responding “don’t know,” an incorrect response, and a correct response would have increasing means on the summed scale, respectively. In addition, monotonicity is evidenced by item characteristic curves.

After item reduction and a final graded model was fit, a scale score was created for each respondent. We used the expected a posteriori (EAP) approach to estimating transplant knowledge scores.25 Since EAP estimated scores are expressed on the z score metric, we linearly transformed them to a T score metric where, . The T scores do not have an upper and lower limit, but higher scores indicate higher transplant knowledge. IRT analyses were conducted in flexMIRT version 3.5.1.25

Statistical Analysis

All statistical tests used a p value of <0.05 to indicate statistical significance and were conducted in SAS version 9.4.26 Participant characteristics were summarized with proportions, frequencies, means and ranges. We described each item by calculating the proportions and frequencies of each response option. After the transplant knowledge scale was created, we calculated the mean, standard deviation, and percentile scores. To test construct validity, we examined mean differences in the transplant knowledge scale T scores between groups of patients who had previously talked to doctors/medical staff, read brochures, browsed the internet, and watched videos about transplant for < 1 hour vs. ≥ 1 hour with independent samples t tests. Cohen’s d effect sizes for these tests were calculated as the difference in mean T score between groups divided by the pooled standard deviation for the scale. Cohen’s cut-offs for this effect size estimate were used to determine its magnitude: small = 0.20 ≤ d < 0.50; medium = 0.50 ≤ d < 0.80; large = d ≥ 0.80.27

Results

Participants.

The largest proportion of participants were Black (45%), male (57%), had a high school diploma or less education (42%), had Medicare (68%) or Medicaid (57%) insurance, and were on dialysis (82%). (Table 2.) The mean age was 53. Most patients had previously talked to doctors/medical staff about transplant (86%) and read brochures about transplant (68%). Several characteristics differed between patients from the 2 contributing studies, including race/ethnicity, sex, education level, type of health insurance, and number of hours of transplant education received. Notably, the level of health literacy did not differ between these cohorts.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics (n=1,294)

| Demographic and Clinical Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=1,294) | Study 1a (n=733) | Study 2 b (n=561) |

p value | |

| Race/Ethnicity, % (n) | <0.001 | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 45% (582) | 25% (186) | 71% (396) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 32% (415) | 35% (258) | 28% (157) | |

| Hispanic | 22% (284) | 38% (279) | 1% (5) | |

| Non-Hispanic Other Race | 1% (10) | 1% (10) | 0 | |

| Missing | <1% (3) | 0% (0) | <1% (3) | |

| Sex, % (n) | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 57% (732) | 61% (445) | 51% (287) | |

| Female | 43% (562) | 39% (288) | 49% (274) | |

| Missing | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | |

| Years of Age, mean (range) c | 53 (18–85) | 53 (18–85) | 54 (23–75) | 0.15 |

| Education Level, % (n) | <0.001 | |||

| High School Diploma or Less | 42% (542) | 33% (244) | 53% (298) | |

| Some College | 32% (414) | 32% (233) | 32% (181) | |

| College Degree or More | 26% (337) | 35% (256) | 14% (81) | |

| Missing | <1% (1) | 0% (0) | <1% (1) | |

| Type of Health Insurance, % (n) d, e | ||||

| Medicare | 68% (878) | 54% (389) | 87% (489) | <0.001 |

| Medicaid | 52% (670) | 30% (218) | 81% (452) | <0.001 |

| Private Insurance | 37% (481) | 54% (399) | 15% (82) | <0.001 |

| On Dialysis, % (n) e | 82% (1062) | 70% (513) | 98% (549) | <0.001 |

| Health Literacy and Previous Kidney Transplant Education | ||||

| How often someone else helps read hospital materials | 0.11 | |||

| None of the time | 53% (680) | 51% (371) | 55% (309) | |

| A little, some, most, or a lot of the time | 47% (614) | 49% (362) | 45% (252) | |

| Missing | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | |

| Confidence filling out medical forms | 0.77 | |||

| Extremely confident | 48% (633) | 49% (362) | 48% (271) | |

| Quite a bit, somewhat, a little bit, not at all confident | 51% (658) | 51% (371) | 51% (287) | |

| Missing | <1% (3) | 0% (0) | <1% (3) | |

| Have previously talked to doctors/medical staff about transplant | <0.001 | |||

| < 1 hour f, g | 24% (257) | 35% (226) | 7% (31) | |

| ≥ 1 hour | 76% (831) | 65% (415) | 93% (416) | |

| Have previously read brochures about transplant | <0.001 | |||

| < 1 hour f, h | 18% (150) | 30% (136) | 4% (14) | |

| ≥ 1 hour | 82% (700) | 70% (322) | 96% (378) | |

| Have previously browsed the internet about transplant | <0.001 | |||

| < 1 hour f, i | 13% (69) | 17% (67) | 1% (2) | |

| ≥ 1 hour | 87% (485) | 83% (317) | 99% (168) | |

| Have previously watched videos about transplant | <0.001 | |||

| < 1 hour f, j | 22% (76) | 38% (76) | 0 | |

| ≥ 1 hour | 78% (268) | 62% (122) | 100% (146) | |

Patients recruited when presenting for transplant evaluation.

Patients recruited from dialysis centers.

1 missing case for this variable.

More than 1 category could be selected.

0 missing cases for this variable.

Calculated only among patients who reported “yes” to each previous transplant education experience.

27 patients received this educational experience but did not specify the number of hours.

24 patients received this educational experience but did not specify the number of hours.

11 patients received this educational experience but did not specify the number of hours.

11 patients received this educational experience but did not specify the number of hours.

Transplant Knowledge Item Descriptions.

The percentage of correct responses for items ranged between 18% (I15) −78% (I3 and I7). (Table 1.) Intuitively, items with “true/false/don’t know” response options were answered correctly more frequently than those with multiple choice response options. Each item was missing <0.5% of responses.

IRT Modeling.

The first and second eigenvalues from the EFA had a ratio of 4.5 (5.8/1.3), suggesting unidimensionality. The 1-factor CFA model fit reasonably well with RMSEA = 0.06 and CFI = 0.90. Though on the borderline of fit index cut-offs, these results suggest that the items are unidimensional and reflect a single, underlying factor. In addition, Duncan multiple range tests provided evidence that each item had monotonic responses in the expected pattern of “don’t know,” incorrect, and correct as mean summed scores increased.

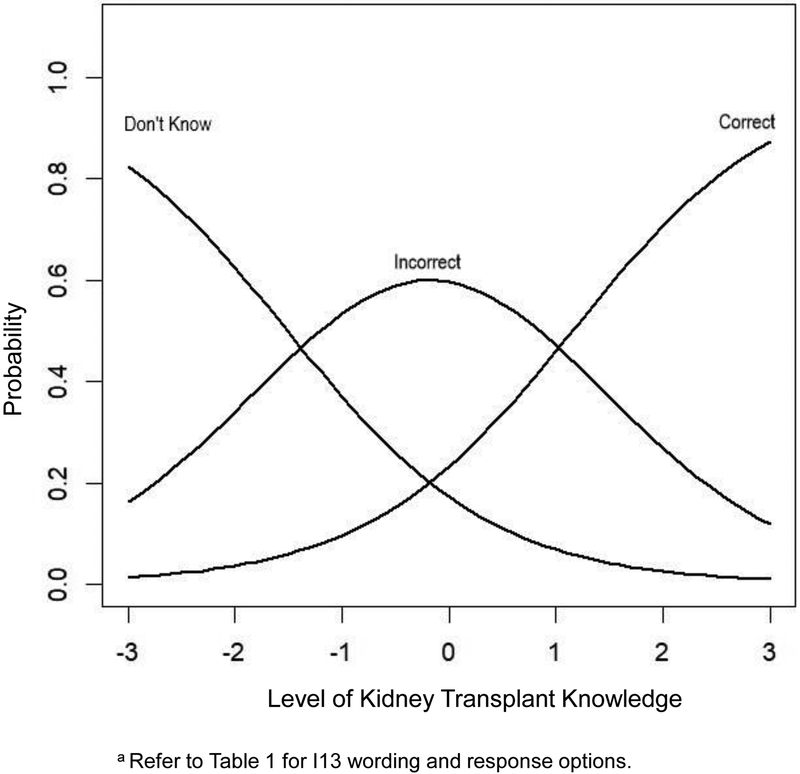

Having evidenced unidimensionality and monotinicity, we proceeded to fit an IRT graded response model. As expected, the b1 difficulty parameters (“don’t know” vs. other responses) represented the low end of the theta range (underlying transplant knowledge ability), and the b2 difficulty parameters (“correct” vs other responses) cover higher theta scores. (Table 3.) For example, for I13, patients with a theta value of −1.55 (approximately 1.5 standard deviations below the mean transplant knowledge level) had a 50% probability of answering “don’t know” vs. “incorrect” or “correct.”; those with a theta value of 1.18 (over 1 standard deviation above the mean transplant knowledge level) had a 50% probability of answering the item correctly vs. responding incorrectly or that they do not know the answer. The item characteristic curve shown in Figure 1. depicts this trend for I13 as an example, though curves were generated and inspected for all items. The easiest items, as determined by b1 and b2, were I2, I3, I7, and I10. The most difficult items were I13 and I15.

Table 3.

Item Response Theory (IRT) Transplant Knowledge Item Parameters

| Item | Difficulty 1 (b1) | Difficulty 2 (b2) | Discrimination (a) | Factor Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | -2.68 | -0.17 | 0.83 | 0.44 |

| I2 | -5.65 | -0.17 | 0.55 | 0.31 |

| I3 | -2.67 | -1.51 | 0.94 | 0.48 |

| I4 | -2.27 | 0.51 | 0.65 | 0.36 |

| I5 | -2.20 | -0.10 | 0.81 | 0.43 |

| I6 | -2.39 | -0.77 | 0.83 | 0.44 |

| I7 | -3.27 | -1.80 | 0.78 | 0.42 |

| I8 | -1.86 | 0.15 | 0.75 | 0.40 |

| I9 | -2.34 | -0.56 | 0.88 | 0.46 |

| I10 | -3.20 | 0.48 | 0.77 | 0.41 |

| I11 | -1.50 | 0.76 | 1.21 | 0.58 |

| I12 | -3.01 | 1.17 | 0.81 | 0.43 |

| I13 | -1.55 | 1.18 | 1.00 | 0.51 |

| I14 | -1.68 | 0.48 | 1.21 | 0.58 |

| I15 | -0.91 | 1.65 | 1.14 | 0.56 |

| I16 | -1.76 | -0.64 | 1.07 | 0.53 |

| I17 | -1.47 | 0.45 | 1.17 | 0.57 |

Figure 1.

Item Characteristic Curve for I13 a

Figure 1 also serves as an example of an item with well-distributed response options, since each response (“don’t know,” “incorrect,” “correct”) covers a unique area under the curve of transplant knowledge level. For example, for I13, patients with theta values between −3 and −1.55 (lowest transplant knowledge ability) have a higher probability of responding “don’t know” than to give an incorrect response. In turn, patients with theta values of −1.56 to 1.00 have a higher probability of giving an incorrect response than to give a correct response or respond that they do not know the answer. Finally, patients who had theta values of 1.01 to 3 have a higher probability of answering correctly than to give an incorrect response or to respond that they do not know the answer. Most of the multiple-choice items show this pattern, though most of the true/false/don’t know items did not.

Item discriminations ranged between 0.55–1.21. The 2 items with the lowest discrimination were I2 and I4, and each of these had a factor loading of <0.40. For this reason, we omitted I2 and I4 from the scale. After removing these 2 items, model fit improved: AIC decreased from 39,221.95 to 34,467.35, and BIC decreased from 39,485.39 to 34,699.79.

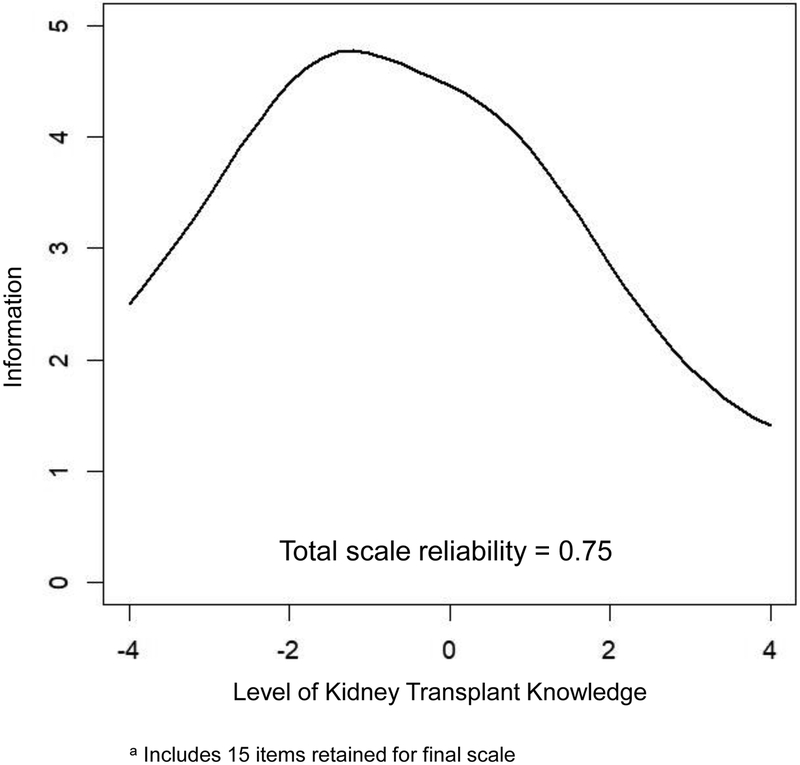

The test information function for the 15-item scale (after removing I2 and I4) is shown in Figure 2. Information was highest at theta = −1.2 (approximately 1 standard deviation below the mean), where the information value was 4.77, entailing a reliability of 0.80. Information was lowest at the highest theta values, ranging between theta = 2.0–2.8, entailing reliabilities of 0.52–0.65 within this range. The marginal reliability of the 15-item scale was 0.75, indicating acceptable reliability.

Figure 2.

Test Information Curve for Knowledge Assessment of Renal Transplantation a

We created the Knowledge Assessment of Renal Transplantation (KART) from these 15 items. On the T score metric (mean = 50, SD=10), the lowest observed score was 10.9 and the highest was 75.5. Using the information from Tables 1 and 4, The KART scale can be administered and scored. Table 1 shows all the items and possible responses, indicating whether or not each is included in the 15 item KART scale. Then, Table 4 shows conversions from summed scores to T scores. After administering the 15 KART items, responses can be recoded as 0 = “Don’t know,” 1 = incorrect response, 2 = correct response. Then, these responses are summed to obtain a raw score ranging from 0–30. Finally, Table 4 is used to match the raw score with the T score.

Table 4.

Summed to T score Conversion for the Knowledge Assessment of Renal Transplantation (KART)

| Summed Score | T score |

|---|---|

| 0 | 10.9 |

| 1 | 13.8 |

| 2 | 16.2 |

| 3 | 18.5 |

| 4 | 20.6 |

| 5 | 22.6 |

| 6 | 24.6 |

| 7 | 26.4 |

| 8 | 28.3 |

| 9 | 30.1 |

| 10 | 31.9 |

| 11 | 33.6 |

| 12 | 35.4 |

| 13 | 37.1 |

| 14 | 38.9 |

| 15 | 40.6 |

| 16 | 42.4 |

| 17 | 44.2 |

| 18 | 46.0 |

| 19 | 47.8 |

| 20 | 49.7 |

| 21 | 51.6 |

| 22 | 53.7 |

| 23 | 55.8 |

| 24 | 58.0 |

| 25 | 60.3 |

| 26 | 62.8 |

| 27 | 65.4 |

| 28 | 68.4 |

| 29 | 71.6 |

| 30 | 75.5 |

This conversion is based on a summed score with response coding of the items as 0= “Don’t know”, 1 = “Incorrect”, 2 = “Correct”.

Construct Validity.

Table 5. shows differences in the KART T scores between patients who had previously talked to doctors/medical staff, read brochures, browsed the internet, and watched videos about transplant for < 1 hour vs. ≥ 1 hour. All differences were significant at p<0.001 and effect sizes were of small to medium magnitude, ranging from d = 0.44 to 0.64.

Table 5.

Differences in Mean Knowledge Assessment of Renal Transplantation (KART) T Scores between Patients Receiving ≥1 and <1 Hour of Various Kidney Transplant Education Approaches

| Mean | p value | Effect Size | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Previously talked to doctors/medical staff about transplant | <0.001 | 0.60 | |

| < 1 hour | 46.3 | ||

| ≥ 1 hour | 52.3 | ||

| Previously read brochures about transplant | <0.001 | 0.44 | |

| < 1 hour | 48.0 | ||

| ≥ 1 hour | 52.4 | ||

| Previously browsed the internet about transplant | <0.001 | 0.64 | |

| < 1 hour | 47.0 | ||

| ≥ 1 hour | 53.4 | ||

| Previously watched videos about transplant | <0.001 | 0.56 | |

| < 1 hour | 48.2 | ||

| ≥ 1 hour | 53.8 |

Effect size calculated as difference between T score means and a pooled scale SD of 10.0

Discussion

Kidney patients present to community nephrologists’ offices, dialysis centers and transplant centers with varying levels of transplant knowledge. Reliability and validity in transplant knowledge assessment is necessary in order to scientifically study efforts to improve transplant knowledge among these patients. Reliable and valid outcome knowledge measures can help providers conduct brief knowledge assessments and tailor education and discussion accordingly. They can also help ensure investigators assess the efficacy of individual educational trials and allow comparisons of transplant knowledge to occur across trials. After a comprehensive development process and psychometric evaluation of the KART, a new, general kidney transplant knowledge scale covering both living and deceased donation, we found evidence supporting the KART’s reliability and construct validity for use with diverse patients on dialysis and those seeking kidney transplantation.

The KART may be immediately helpful in research trials assessing the efficacy of transplant education programs. In addition, other research designs, such as population-based surveys or cohort studies examining the average level of transplant knowledge in a targeted patient population may also benefit from use of this measure.28 Current transplant education programs that have not been rigorously tested for improving transplant knowledge could incorporate the KART for this purpose.29

The KART is brief at only 15 items. Also, past research has shown that patients who present to the transplant center to begin evaluation often have little knowledge about it.28 Transplant knowledge screening using the KART for patients who are in most need of educational support can help direct staff resources most efficiently.30 The summed score to T score conversion table found in Table 4 can be used to obtain KART scores easily if it is administered in the clinical transplant education or quality improvement settings. The T score metric based on IRT scores is often superior to summed scores because they incorporate information about the items’ difficulty and discriminatory ability, they also provide a truly linear scale with equal distance between values (eg, the difference between values of 1 and 2 is the same as the difference between values of 2 and 3), and the score for a group is always able to be evaluated in terms of standard deviations from the mean.

In addition, because the KART is based on IRT parameters, it could be administered as a computer-adaptive test. This would allow fewer items from the KART to be administered while retaining its current measurement properties, or to administer different subsets of items from the KART that can be mapped back to a common metric. This flexibility could be leveraged to aid in efficient, flexible transplant knowledge assessments in a variety of settings.

The KART evidenced the highest reliability for patients with lower levels of kidney transplant knowledge. The patients most likely to benefit from kidney transplant education interventions are those with low transplant knowledge, including patients whose kidneys have not yet failed or who have just started dialysis. Therefore, the KART is most reliable for the patients with whom it may be most critical to assess kidney transplant knowledge. We also note that the reliability of the KART is lower than, both overall and at various theta values, previously-published cut-offs for individual use; ie, ≥0.90.31 Despite KART reliability values falling below this cut-off, we believe it may have value for clinical use with individual patients in some cases where its content is relevant for the clinical application. However, we do recommend caution in interpreting its results in these cases. On the other hand, reliability almost always exceeded standards for group comparisons (>0.70), indicating an important role for KART not only in research, but in dialysis- or transplant-center-based quality improvement projects to examine the impact of patient education materials about kidney transplant.

One unique aspect of the KART is its use of “don’t know” responses in the scoring algorithm. Like other studies, we found evidence that individuals who select the “don’t know” response have the lowest level of knowledge.32,33 However, there is no consensus on whether or not use of a “don’t know” option is appropriate for tests of knowledge, and trade-offs associated with including this option must be considered. Some benefits of including a “don’t know” option include increased reliability and increased score accuracy.34 In addition, scales with “don’t know” options included in scoring may be more sensitive to knowledge improvements associated with educational interventions, especially for individuals with very low knowledge at baseline.35 On the other hand, inclusion of “don’t know” responses may reduce construct validity by introducing variance in responses not related to the level of transplant knowledge itself, since it would lead individuals with lower willingness to guess the answer to an item not to choose one of the substantive response options.34 Future studies should further explore the optimal scoring approach for the KART.

This study has several limitations. First, these data only included English-speaking patients. With a large presence of Spanish-speaking kidney patients in the United States,1 this measure’s psychometric properties must be explored and tested among this group specifically. Next steps include differential item functioning analyses with these patient populations, as well as with other key patient subgroups, like race/ethnicity, age, and gender groups. In addition, the items included in the KART were intended for patients receiving dialysis or seeking transplantation, and their measurement properties were tested only among a limited sample of kidney patients in the United States meeting these criteria. Additional patient populations, including some patients in CKD stages 3 and 4 who have not yet started dialysis and kidney patients outside of the United States, also may require assessment of kidney transplant knowledge. The measurement properties of the KART should also be examined with these patient populations. Finally, the sample of patients used here participated in 2 randomized controlled trials. Therefore, it may not represent the national ESRD population in terms of clinical characteristics. Next steps would include administration of this instrument in large probability samples.

Future updates to the KART should also include more difficult items that better test transplant knowledge among patients experienced with kidney transplant seeking, but who could still learn important information about its process and outcomes. These may include more questions on the risks of transplant, as research emerges to increase that knowledge base. While the KART provides a brief assessment of general transplant knowledge, in cases where targeted focus on specific elements of kidney transplantation (eg, living donation), the subscales of the Rotterdam Renal Replacement Therapy Knowledge Test (R3K-T) may be a better option to use, as this test has also demonstrated good measurement properties.17 Finally, this study employed secondary data from previous studies not suited for some reliability and validity analyses, including test-retest reliability and construct validity tests against other knowledge scales like the R3K-T. Future, prospective studies should seek to conduct these analyses.

In conclusion, the 15-item KART can be used in both research and clinical settings to determine the kidney transplant knowledge of ESRD patients and to tailor educational interventions and discussions accordingly. Since it is brief, the KART can be used without imposing significant burden on patients or clinicians. Employing this measure in studies and in clinic with such patients will mark an improvement over measures without demonstrated psychometric properties.

Acknowledgments.

We would like to thank Drs. Peter Bentler and Steve Reise for their advice on psychometric modeling.

Funding. This study was funded by NIDDK R01DK088711–01A1 (awarded to Amy D Waterman), HRSA R39OT26843–01-02 (awarded to Amy D Waterman), and HRSA R39OT29879 (awarded to Amy D Waterman). Ron D. Hays was supported in part by NIA P30-AG02168.

List of abbreviations

- AIC

Akaike’s information criterion

- BIC

Bayesian information criterion

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- CFA

Confirmatory factor analysis

- CFI

Comparative fit index

- CMS

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- EAP

Expected a posteriori

- ESRD

End-stage renal disease

- EFA

Exploratory factor analysis

- IRT

Item Response Theory

- KART

Knowledge Assessment of Renal Transplantation

- LDKT

Living donor kidney transplant

- R3K-T

Rotterdam Renal Replacement Therapy Knowledge Test

- RMSEA

Root mean square error of approximation

Footnotes

Authorship Role. John D Peipert conceived of the study design, conducted psychometric analyses, and lead the manuscript drafting. Ron D Hays consulted on the study design, conducted psychometric analyses, and critically reviewed the manuscript. Satoru Kawakita and Jennifer L Beaumont conducted statistical analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript. Amy D Waterman conceived of the study design, designed the transplant knowledge items, conducted data analyses, and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.United States Renal Data System. 2017 USRDS annual data report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2017. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogutmen B, Yildirim A, Sever MS, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life After Kidney Transplantation in Comparison Intermittent Hemodialysis, Peritoneal Dialysis, and Normal Controls. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(2):419–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von der Lippe N, Waldum B, Brekke FB, Amro AA, Reisæter AV, Os I. From dialysis to transplantation: a 5-year longitudinal study on self-reported quality of life. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15(1):191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kucirka LM, Grams ME, Balhara KS, Jaar BG, Segev DL. Disparities in provision of transplant information affect access to kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(2):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salter ML, Gupta N, King E, et al. Health-Related and Psychosocial Concerns about Transplantation among Patients Initiating Dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:1940–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salter ML, Kumar K, Law AH, et al. Perceptions about hemodialysis and transplantation among African American adults with end-stage renal disease: inferences from focus groups. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(1):49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with live donor kidney transplantation in the united states from 1995 to 2014. JAMA. 2018;319(1):49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Conditions for Coverage for End-Stage Renal Disease Facilities; Final Rule In: Department of Health and Human Services, ed. Vol 73 Baltimore, MD: Federal Register; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterman AD, McSorley AM, Peipert JD, et al. Explore Transplant at Home: a randomized control trial of an educational intervention to increase transplant knowledge for Black and White socioeconomically disadvantaged dialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(150). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waterman A, Hyland S, Goalby C, Robbins M, Dinkel K. Improving transplant education in the dialysis setting: The “Explore Transplant” initiative. Dial Transplant. 2010;39(6):236–241. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodrigue JR, Paek MJ, Egbuna O, et al. Making House Calls Increases Living Donor Inquiries and Evaluations for Blacks on the Kidney Transplant Waiting List. Transplantation. 2014;98:979–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Kaplan B, Howard RJ. A randomized trial of a home-based educational approach to increase live donor kidney transplantation: effects in blacks and whites. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;51(4):663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strigo TS, Ephraim PL, Pounds I, et al. The TALKS study to improve communication, logistical, and financial barriers to live donor kidney transplantation in African Americans: protocol of a randomized clinical trial. BMC Nephrol. 2015;16(1):160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, et al. Effectiveness of educational and social worker interventions to activate patients’ discussion and pursuit of preemptive living donor kidney transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;61(3):476–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arriola KR, Powell CL, Thompson NJ, Perryman JP, Basu M. Living donor transplant education for African American patients with end-stage renal disease. Prog Transplant. 2014;24(4):362–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patzer RE, Basu M, Larsen CP, et al. iChoose Kidney: A Clinical Decision Aid for Kidney Transplantation Versus Dialysis Treatment. Transplantation. 2016;100:630–639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ismail SY, Timmerman L, Timman R, et al. A psychometric analysis of the Rotterdam Renal Replacement Knowledge-Test (R3K-T) using item response theory. Transpl Int. 2013;26(12):1164–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waterman AD, Robbins ML, Paiva AL, et al. Your Path to Transplant: a randomized controlled trial of a tailored computer education intervention to increase living donor kidney transplant. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC. Living donation decision making: recipients’ concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waterman AD, Barrett AC, Stanley SL. Optimal transplant education for recipients to increase pursuit of living donation. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(1):55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chew LD, Griffin JM, Partin MR, et al. Validation of screening questions for limited health literacy in a large VA outpatient population. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(5):561–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slocum-Gori SL, Zumbo BD. Assessing the Unidimensionality of Psychological Scales: Using Multiple Criteria from Factor Analysis. Soc Indic Res 2011;102(3):443–461. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide Los Angeles, CA; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Houts CR, Cai L. flexMIRT user’s manual version 3.5: Flexible multilevel multidimensional item analysis and test scoring Chapel Hill, NC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.SAS Institute I. Base SAS(R) 9.4 Procedures Guide: Statistical Procedures 2nd ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences New York: Academic Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Hyland SS, McCabe MS, Schenk EA, Liu J. Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(6):995–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waterman AD, Robbins ML, Peipert JD. Educating Prospective Kidney Transplant Recipients and Living Donors about Living Donation: Practical and Theoretical Recommendations for Increasing Living Donation Rates. Curr Transplant Rep 2016;3(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Goalby CJ, Dinkel KM, Xiao H, Lentine KL. Assessing Transplant Education Practices in Dialysis Centers: Comparing Educator Reported and Medicare Data. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(9):1617–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leigh JH, Jr. CRM. “Don’t Know” Item Nonresponse in a Telephone Survey: Effects of Question Form andRespondent Characteristics. J Mark Res 1987;24(4):418–424. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maris E Psychometric Latent Response Models. Psychometrika. 1995;60(4):523–547. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravesloot CJ, Van der Schaaf MF, Muijtjens AMM, et al. The don’t know option in progress testing. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2015;20(5):1325–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cherry KE, Brigman S, Hawley KS, Reese CM. The Knowledge of Memory Aging Questionnaire: Effects of adding a “don’t know” response option. Educ Gerontol. 2003;29(5):427–446. [Google Scholar]