Abstract

Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is the most common cause of inherited intellectual disability that can be traced to a single gene mutation. This disorder is caused by the hypermethylation of the Fmr1 gene, which impairs translation of Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP). In Fmr1 knockout (KO) mice, the loss of FMRP has been shown to negatively impact adult hippocampal neurogenesis, and to contribute to learning, memory, and emotional deficits. Conversely, physical exercise has been shown to enhance cognitive performance, emotional state, and increase adult hippocampal neurogenesis. In the current experiments, we used two different voluntary running paradigms to examine how exercise impacts adult neurogenesis in the dorsal and ventral hippocampal dentate gyrus (DG) of Fmr1 KO mice. Immunohistochemical analyses showed that short-term (7 day) voluntary running enhanced cell proliferation in both wild-type (WT) and Fmr1 KO mice. In contrast, long-term (28 day) running only enhanced cell proliferation in the whole DG of WT mice, but not in Fmr1 KO mice. Interestingly, cell survival was enhanced in both WT and Fmr1 KO mice following exercise. Interestingly we found that running promoted cell proliferation and survival in the ventral DG of WTs, but promoted cell survival in the dorsal DG of Fmr1 KOs. Our data indicate that long-term exercise has differential effects on adult neurogenesis in ventral and dorsal hippocampi in Fmr1 KO mice. These results suggest that physical training can enhance hippocampal neurogenesis in the absence of FMRP, may be a potential intervention to enhance learning and memory and emotional regulation in FXS.

Keywords: Fragile-x syndrome, neurogenesis, exercise, hippocampus, mouse

INTRODUCTION

Fragile-X syndrome (FXS) is the most common form of inherited intellectual disability in humans, affecting approximately 1 in 4000 males and 1 in 8000 females [1, 2]. Most of the cases are caused by a trinucleotide CGG expansion in the 5’-untranslated region of the fragile X mental retardation gene (Fmr1). With this expansion, the Fmr1 gene is hypermethylated and the protein product is lost, resulting in learning and memory impairments, as well as anxiety and depressive-like behavior [3, 4], in addition to a cascade of developmental impairments in cognitive functioning, behavioral and emotional problems [5].

Fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) is a mRNA binding protein thought to be important for normal neuronal development [6, 7]. FMRP is widely expressed in the developing brain [8, 9], with the hippocampus being one of the major sites for FMRP expression in the fetal brain [10]. This loss of functional FMRP in neural stem cells in the adult brain has been shown to disrupt hippocampal neurogenesis and impair learning [11, 12]. To date, only symptom-based medications have been used in FXS patients since there are no particularly efficient interventions for FXS [13].

The hippocampal formation is associated with declarative memory, spatio-temporal contextualization of memories, and also spatial learning and memory [14]. Neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus (DG) has been observed in all mammalian species examined to date, including humans and rodents [15, 16]. Physical exercise increases cell proliferation, neurogenesis, and synaptic plasticity, as well as spatial memory function in the rodent DG [17–21]. Furthermore, enhancements in neurogenesis and neuronal plasticity induced by physical exercise can be associated with a decrease in depressive-like behaviours and enhancement in cognitive function associated with several neurodegenerative diseases [22–24].

Building upon our previous work showing abnormal hippocampal neurogenesis in Fmr1 knockout mice [12], we investigated the effects of short-term and long-term voluntary running on hippocampal neurogenesis in Fmr1 knockout mice and their WT littermates. Given the postulated different functional roles of the dorsal hippocampus for declarative memory and sensory information processing, and the ventral hippocampal formation for emotion and stress response regulation (Hunsaker et al., 2007, Fanselow and Dong, 2010), we also examined whether chronic running exerts differential effects on adult neurogenesis in the dorsal and ventral DG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

All experiments were carried out in accordance with the international standards on animal welfare and guidelines set by the Canadian Council of Animal Care and the Institutional Animal Care Committee at the University of Victoria. Male Fmr1 homozygous knockout mice (Fmr1 KO) and wild-type (WT) littermate mice with C57Bl/6J genetic background were generated by breeding a female Fmr1 heterozygous mouse with a WT male mouse from breeding colonies. All animals were housed in the same room and maintained in a 12 hour light/dark cycle with standard mouse chow in ventilated racks. Experimenters were blind to the genotypic identity of the animals throughout the experiment and data collection. A cohort of Fmr1 knockout (KO; n = 30) and WT littermates (WT; n = 30) and were given free access to running dish for 1 or 4 weeks starting at either postnatal day (PND) 29 or PND49 respectively (Fig. 1). Animals were injected with BrdU (200 mg/kg) daily for 3 days prior to starting voluntary exercise in order to examine neuronal survival [25].

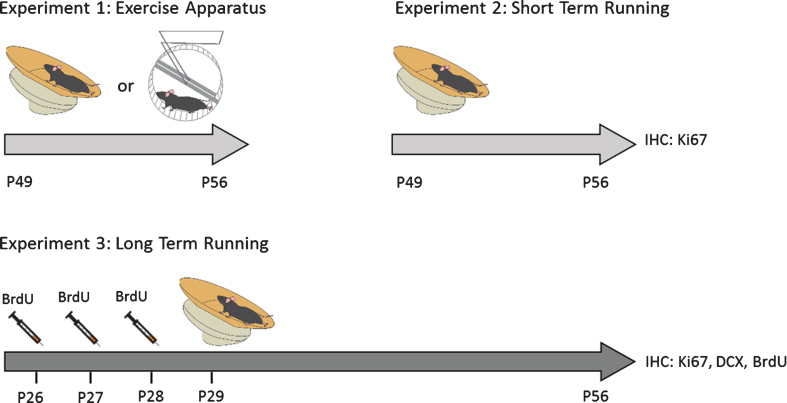

Fig.1.

Experimental Design. Male Fmr1 knockout (KO) and wild-type (WT) were given free access to a running dish or wheel starting at either postnatal day (PND) 29 or PND49 for 1 week (short-term running) or 4 weeks (long-term running). To study the effect of long-term running on cell survival, mice were injected with BrdU (100 mg/kg) daily for 3 days prior to voluntary running in order to labelproliferating cells.

Genotyping

Genotyping was conducted as previously described [26–28]. Briefly, ear snips were used to isolate DNA using the DNA isolation kit according manufacture’s instruction (Invitrogen, Ontario, Canada), followed by PCR analysis with cycling parameters: denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 60 s at 94°C, 90 s at 65°C and 150 s at 72°C. Primers used for probing the Fmr1 KO allele (800 base pairs) were:

M2 = 5’-ATCTAGTCAYGCTATGGATATCAGC-3’ and

N2 = 5’-GTGGGCTCTATGGCTTCTGAGG-3’.

Primers for probing the WT allele (450 base pairs) were:

S1 = 5’-GTGGTTAGCTAAAGTGAGGATGAT-3’and

S2 = 5’-CAGGTTTGTTGGGATTAACAGATC-3’.

Voluntary running

Mice (n = 20) were given access to either an unlocked or a locked running dish (Med associates Inc, USA) for 7 (short-term running) or 28 days (long-term running). The voluntary exercise groups were housed in standard cages with unlocked running dishes that allowed the animals to voluntarily run on the dish (EX). Control animals in the sedentary group (SED) were housed in standard cages with locked running dishes giving them equal exposure to the apparatus.

Tissue preparation

Mice were deeply anesthetized with inhaled isoflurane and were subsequently perfused with 0.9 % saline for 5 min, followed by 4 % paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min. The isolated brains were post-fixed in 4 % PFA overnight at 4°C. The brains were then transferred to 30 % sucrose. The brain slices (1-in-6 series, 30 μm thickness) were sectioned using a vibratome (Leica VT 1000S). The slices were stored in Walter’s Antifreeze at –4°C until use.

Immunohistochemistry and immuofluorescent staining

The BrdU staining was performed as previously described [12, 23, 29] in order to examine cell survival. The sections underwent antigen retrieval in citric buffer (pH 8.0) at 95°C for 30 min, followed by incubation in 2 N HCl for 30 min at 37 °C and 0.1 M borate buffer (pH 8.5) for 15 min. After washings in 0.01 M PBS, the sections were incubated overnight with the rat anti-BrdU (1:1000, Abcam) and Rabbit anti-DCX (1:200 Abcam) in the blocking diluents containing 10 % goat serum, 5% Triton X overnight, followed by incubation of secondary antibodies: goat anti-rabbit IgG Alexa-Fluor 488 and goat anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor-568 (1:200, Dako) for two hours. The sections were then cover-slipped with mounting medium and were observed by using fluorescent microscopy.

Cell proliferation and differentiation were assessed by Ki67 and doublecortin (DCX) staining respectively, which was performed as previously described [30], following antigen retrieval at 95°C for 10 min and three washes in 0.01 M PBS, sections were incubated for 1 hour with blocking solution and then incubated with rabbit anti-DCX (1:200, Abcam) or rabbit anti-Ki67 (1:500, Dako) antibody in blocking solution containing 10 % goat serum, 5% 10% Triton X overnight, followed by the secondary antibody: goat anti-rabbit (1:200) or horse anti-goat (1:200) for two hours at room temperature. The staining was visualized with the peroxidase method (ABC system, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and diaminobenzidine kits (DAB kits, Sigma-Aldrich).

Cell quantification

We conducted a modified stereological approach to quantify all cells that were DAB-positive in 30μm sections taken across the rostral-caudal extent of the hippocampus using a 40x objective and an Olympus microscope (BX51; Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA), with the experimenter blinded as to group identity, as previously described [30]. From each animal, every sixth coronal section (180μm apart) was DAB stained for one antibody (i.e BrdU, DCX, Ki-67). Separate one-in-six series of sections, taken from the same animal, were immunostained for each antibody. In the x-y plane, immunopositive cells limited to the neurogenic subgranular zone of the DG were manually counted in a blind fashion. We defined the subgranular zone as the area within two cell bodies (∼20μm) of the inner edge of the molecular layer. For the z-plane, a modified optical dissector method was employed that excluded immunolabeled cells on the uppermost surface of the slice. Resulting numbers were multiplied by six to provide an estimate of total number of immunopositive cells for each animal. Split nuclei cells, or cells that had not completed cytokinesis, were counted as a single cell, again to provide a conservative estimate. For some analyses, the hippocampus was separated into dorsal (–1.30 to –2.54 bregma) and ventral (–2.78 to –3.80 bregma) components to evaluate potential region-specific changes in neurogenesis as described previously [12].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS analytical software. A repeated measures ANOVA was used to examine differences in running distance across days for data comparing running activity between WT and Fmr1 KO mice. Cell counts were analyzed with a two-way ANOVA and subsequent Tukey post-hoc analyses. Data are presented as means±SEM. A p-value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Comparison between voluntary wheel running and dish running

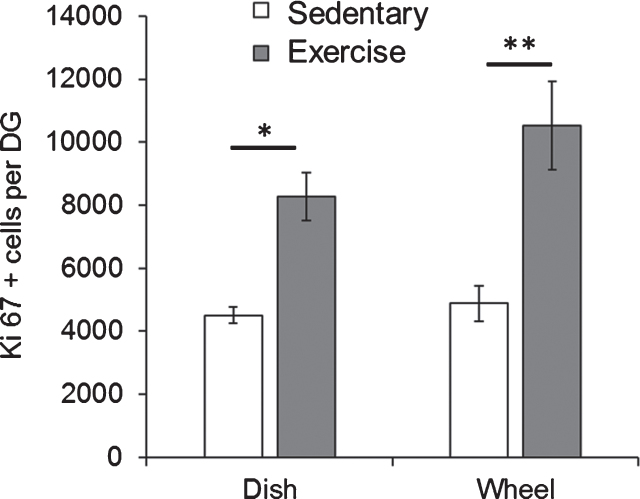

We initially examined whether the type of running apparatus that the mice were exposed to would impact the rate of cell proliferation. For these experiments, Fmr1 KO mice were housed with either a running wheel or a running dish for 7 days starting at PND49. At PND56, the mice were euthanized and Ki67 positive cells in the granule cell layer were assessed. Comparison of the means using a two-way ANOVA revealed a statistically significant effect of the experimental group (EX vs SED) on the number of Ki67 positive cells (F(1,10) = 34.35, p = 0.0001). The type of apparatus (wheel vs dish) did not show a significant effect (F(1,10) = 2.757, p = 0.13). As illustrated in Fig. 2, the post-hoc test revealed that in both cases, number of Ki67 positive cells was significantly higher in exercised animals than sedentary animals (Dish-SED: 4509.03±254.60, Dish-EX: 8282.47±756.23, p = 0.01; Wheel-SED: 4889.5±564.58, Wheel-EX: 10517.27±1397, p = 0.003).

Fig.2.

Both dish running and wheel running significantly enhanced hippocampal cell proliferation in Fmr1 KO mice. Short-term running on wheels and dishes significantly increased the number of Ki67 positive proliferating cells in Fmr1 KO mice. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.005.

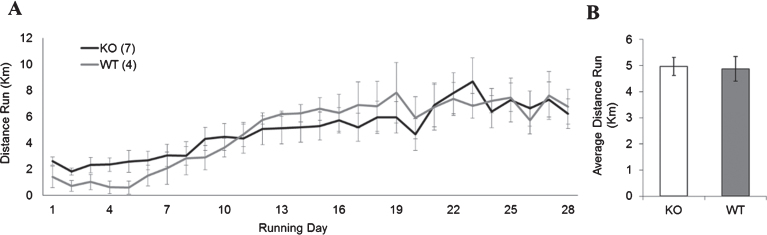

To ensure that the distance ran by the Fmr1 KO and WT groups would not impact the interpretation of these results, we next examined if both groups would run equitable distances with the running dish apparatus. There was no significant difference in the average running distance (in kilometers) between Fmr1 KO mice and WT mice using running-dishes (Fig. 3; KO: 4.87±1.13; WT: 4.96±1.31, p > 0.05). Because the running dishes allowed animals to be housed in standard ventilated racks, the remainder of the experiments were carried out using the running dishes.

Fig.3.

WT and FMR1 KO running performance. (A) Average daily distance run (in km) per day for animals given access to an unlocked running dish for 28 days continuously. (B) There was no statistically significant differences in total average distance run between WT and Fmr1 KO mice.

Short-term running paradigm equally enhances dentate gyrus cell proliferation in WT and KO animals

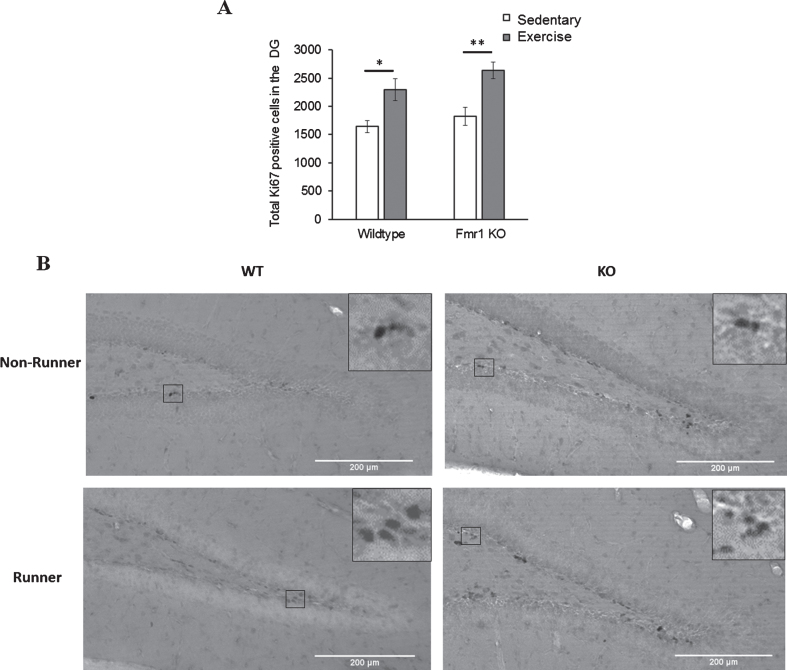

Comparison of number of Ki67 positive cells between genotypes and paradigms revealed a significant main effect of paradigm (p < 0.005). WT runners showed significantly more Ki67 positive cells than sedentary WT animals (Fig. 4; WT-EX: 2296.92±158.54; WT-SED: 1642.13±146.78, p = 0.033). Similarly, KO runners exhibited a significant increase in Ki67 positive cells than their sedentary counterparts (KO-EX: 2638.80±145.57; KO-SED: 1827.87±172.453, p = 0.003), indicating that short-term running could significantly enhance cell proliferation in the DG of both WT (p = 0.033) and Fmr1 KO mice (p = 0.003). There was no significant difference in the numbers of Ki67 positive cells between WT and KO for either sedentary or running animals, indicating that Ki67 expression was equitable between experimental groups, and enhanced equivalently by the running dish experimental condition.

Fig.4.

Effects of short-term running in hippocampal cell proliferation. (A) Short-term (7 days) running enhanced the number of Ki67 positive cells in the DG in WT (*p < 0.05) and Fmr1 KO mice (**p < 0.005), indicating acute running can enhance hippocampal proliferation in both WT and Fmr1 KO mice. (B) Representative images of Ki67 positive cells. Scale bar: 200μm.

Effects of long-term running on hippocampal cell proliferation, differentiation and survival on the entire dentate gyrus

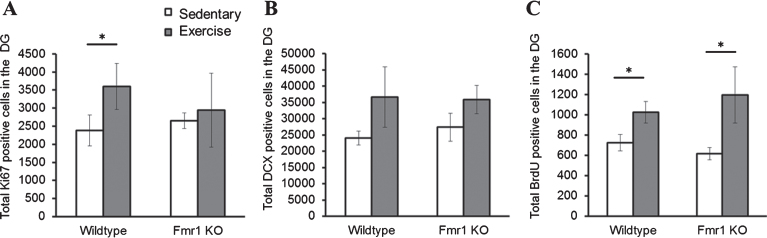

The effects of long-term running on cell proliferation, differentiation and survival were examined with immunohistochemical analysis of Ki67, DCX and BrdU positive cells respectively (Fig. 5). Cell proliferation data revealed a significant interaction effect between genotype and running on the number of Ki67 positive cells. Long-term running significantly increased cell proliferation in WT mice (Fig. 5A; WT-SED mice: 2383.41±421.3; WT-EX: 3595.71±283.611, p = 0.004), but not in Fmr1 KO mice (KO-SED: 2660.59±164.5; KO-EX: 2819.85±251.503, p = 0.967).

Fig.5.

Effect of long-term running on hippocampal neurogenesis. (A) Long-term running enhanced hippocampal cell proliferation in WT, but not in Fmr1 KO mice. (B) Long-term running did not show significant effect on increasing number of immature neurons. (C) Long-term running significantly increased number of BrdU positive cells in both WT and Fmr1 KO mice (*p < 0.05).

DCX positive cells were counted to examine cell differentiation, and this indicated a significant effect of experimental condition (p = 0.01). A post-hoc analysis of each group only revealed a trend towards a statistically significant increase of DCX positive cells after 28 days of running in both WT (Fig. 5B; WT-SED: 23303.23±1435; WT-EX: 32498.80±5277.8; p = 0.357) and Fmr1 KO mice (KO-SED: 27526.54±3194; KO-EX: 36486.33±2876.3; p = 0.168). Finally, the number of BrdU positive cells also showed a significant main effect of running on the number of BrdU positive cells (p = 0.032): a significant increase in BrdU positive cells was observed in animals that exercised in both WT (Fig. 5C; WT-SED: 697.54±73.85; WT-EX: 1015.32±77.80; p = 0.05) and Fmr1 KO mice (KO-SED: 584.86±66.39; KO-EX: 1050.76±212.80; p = 0.032).

Effects of long-term running on dorsal and ventral regions of the dentate gyrus

Previously we have found that neurogenesis varies in the ventral and dorsal aspects of the hippocampus in Fmr1 KO mice [25]. To examine whether running differentially affected neurogenesis in these areas we examined dorsal and ventral aspects of the hippocampus separately.

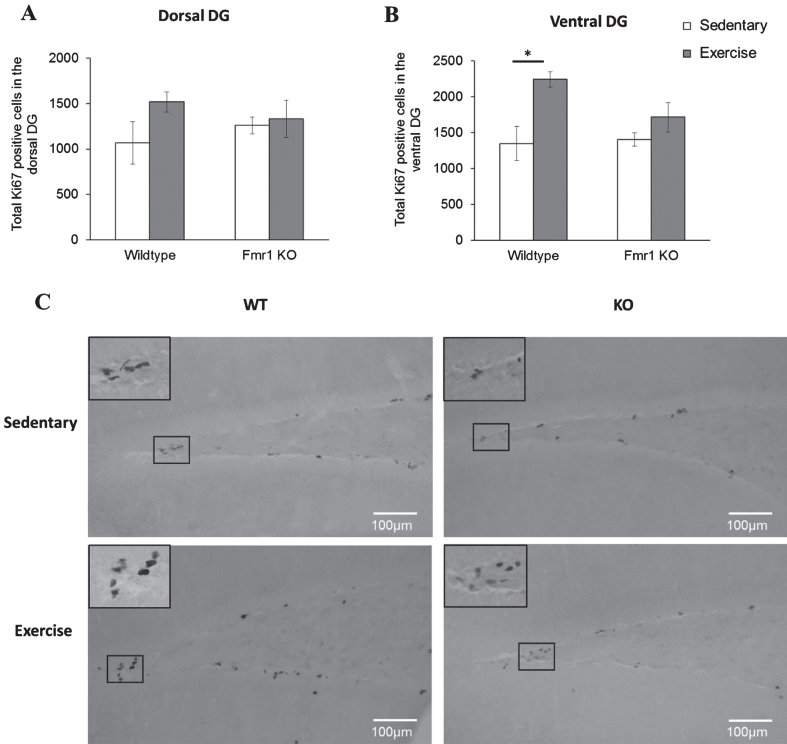

Cell proliferation showed a significant main effect of paradigm in the ventral region (p = 0.005). Specifically, number of Ki67 positive cells was increased in WT runners compared to their sedentary counterparts (Fig. 6B; WT-SED: 1348.88±171.52; WT-EX: 2241.75±142.46, p = 0.019) but not in Fmr1 KO mice (KO-SED:1409.96±144.4; KO-EX:1716.1±240.8; p = 0.601). On the dorsal DG, running did not alter cell proliferation of WT (WT-SED:1066.67±235.37; WT-EX:1517.65±110.7, p = 0.277) nor KO mice (KO-SED:1259.96±91.6; KO-EX:334.3±205.1; p = 0.987) (Fig. 6A).

Fig.6.

Long-tern running alters hippocampal cell proliferation. (A, B) Long term exercise increased Ki67 positive cells on the WT ventral region of the hippocampus, while no effects of exercise were seen in the dorsal region (*p < 0.05). (C) Representative images of Ki67 positive cells. Scale bar: 100μm.

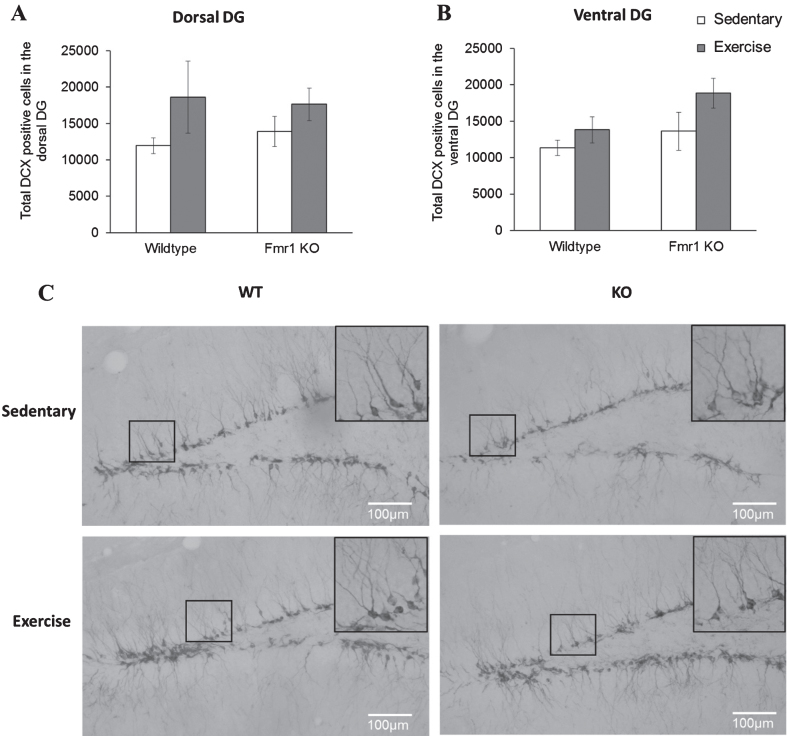

Again, long-term running did not affect cell differentiation in WT or Fmr1 KO mice. On the dorsal region, post-hoc analysis revealed that WT runners showed a comparable number of DCX positive cells to their sedentary counterparts (Fig. 7; WT-SED:11344.9±1030.9; WT-EX:13819.87±1770.5, p = 0.397) and similar results were found in Fmr1 KO mice (KO-SED:13628.5±2626.9; KO-EX:18852.05±2068.5; p = 0.642). Similarly, in the ventral region, running did not show a significant effect on the number of DCX positive cells (p = 0.103) (Fig. 7B, WT-SED:11947.68±1097.8; WT-EX:18616.43±4942.6; p = 0.0923 / KO-SED:13890.88 ± 2045.8; KO-EX:17643.54 ± 2221.5; p = 0.351).

Fig.7.

Long-term running did not influence the number of newborn neurons in Fmr1 KO mice. (A, B) The number or DCX positive neurons remained unaltered by long-tern running in both dorsal and ventral hippocampus (*p < 0.05). (C) Representative images of DCX-positive cells. Scale bar: 100μm.

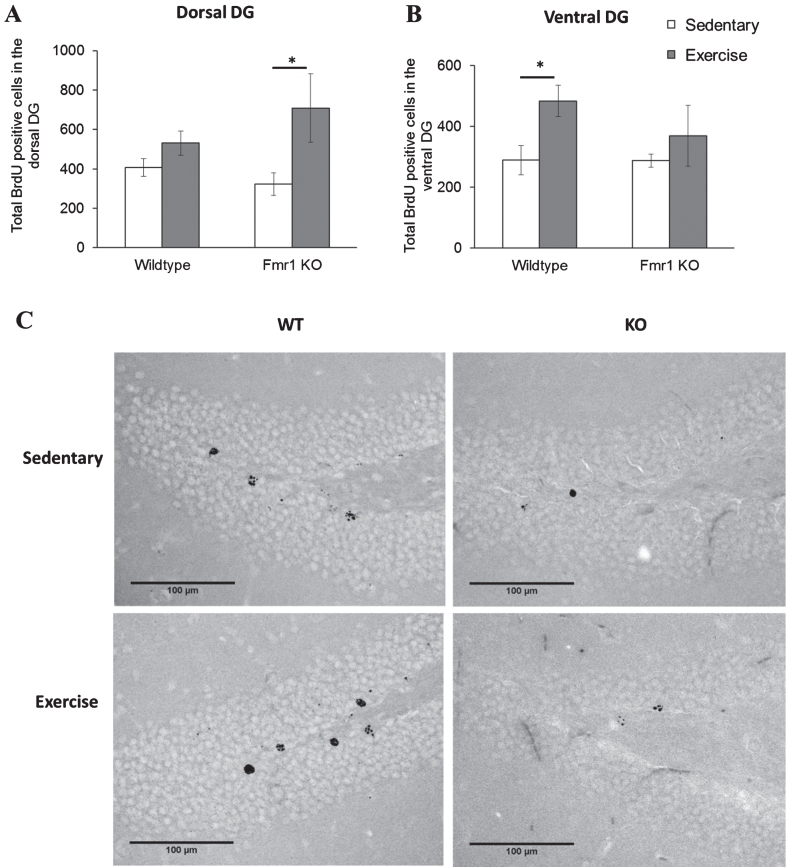

Cell survival analysis of the DG dorsal region revealed a significant main effect of running on the number of BrdU positive cells (p = 0.009). Specifically KO runners showed significantly enhanced cell survival in the DG dorsal region in Fmr1 KO mice (Fig. 8A; KO-SED:323.44±57.2; KO-EX:709.05±172, p = 0.029) while no difference was seen in WT animals (WT-SED: 407.17±45.5; WT-EX: 530.63±61.1, p = 0.777). A significant effect of exercise was also found in the ventral DG (p = 0.044). Interestingly, in this region, exercise significantly increased cell survival in WT mice (Fig. 8B; WT-SED: 288.85±48.19; WT-EX: 483.98±51.17, p = 0.018), but not in Fmr1 KO mice (KO-SED:287.38±21.2; KO-EX:369.51±100, p = 0.784).

Fig.8.

Chronic exercise modifies cell survival rate in FMR1 KO mice. (A) The number of BrdU-positive neurons in dorsal hippocampal dentate gyrus significantly increased after long term running paradigm in FMR1 KO mice. (B) In the ventral dentate gyrus, running did not modify cell survival in the FMR1 KO mice, while in WT animals there was a significant increase in BrdU-positive cells (*p < 0.05). (C) Representative images of BrdU-positive cells in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. Scale bar: 100μm.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have observed an increase of cell proliferation after short-term running in both WT and Fmr1 KO mice. Cell proliferation and cell survival in the DG of WT mice were also increased following a long-term running. However, long-term running exerts differential effects on WT and Fmr1 KO mice. Region-specific regulation by running of cell proliferation and cell survival in dorsal and ventral DGs were observed in WT and Fmr1 KO mice. In WT mice, long-term running significantly enhanced cell proliferation and cell survival in the ventral DG. While in Fmr1 KO mice, long-term exercise significantly enhanced cell survival in the dorsal DG and showed no effect on cell proliferation and neuronal differentiation.

Neurogenesis can be affected by alterations in different phases including cell proliferation, neuronal differentiation and cell survival [31]. Voluntary exercise has been reported to be beneficial to many aspects of the brain structure and function including synaptic plasticity (van Praag et al., 1999b), dendritic structure [25] and neurogenesis [17]. Exercise is also an attractive intervention for individuals suffering from neurodevelopmental disorders such as in FXS due to its relative simplicity and cost-effectiveness in implementation as compared to pharmacological interventions [24].

It has been repeatedly reported that exercise can enhance the rate of cell proliferation and cell survival in mice [23, 32–34]. The present data has provided support for the potential effects of exercise which may be able to mitigate behavioral alterations observed in Fmr1 KO mice, such as the observed changes to emotional behavior [12, 35–38]. Considering that in the present study exercise increased cell survival in the dorsal DG of Fmr1 KO mice but not the ventral DG may expect that the changes to emotional behaviors may not be overcome by physical exercise, though further work must be conducted to directly address this question.

We have previously demonstrated DG region-specific abnormalities in hippocampal neurogenesis in FXS mice [12]. Similarly, we found a reduction in BrdU positive cells in the ventral DG of Fmr1 KO mice. Recent studies have shown that antidepressants may exert their effect by selectively modulating neurogenesis in the ventral DG [39–41], suggesting the differential response of ventral and dorsal DGs to stimuli that may affect neurogenic processes. The present data indicated that voluntary running could increase neurogenesis in the ventral DG of WT mice, similar to previous reports showing enhanced neurogenesis by voluntary running. Our data further support that exercise intervention with pro-neurogenic effect could be a putative antidepressant [42, 43]. Further work could also assess how this exercise-induced neurogenesis could differentially affect synaptic plasticity in both the ventral and dorsal DG.

Exercise has long been known to enhance adult hippocampal neurogenesis through stimulation of the release of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF, VEGF and IGF-1 [44]. BDNF in particular is thought to act as a key mediator of exercise-induced changes to synaptic efficacy, and may be necessary for the proliferation and survival of newborn neurons [45]. While Fmr1 KO mice display normal levels of BDNF in the hippocampus, impairments to synaptic plasticity characteristic of Fmr1 KO mice can be restored by bath application of BDNF [46]. However, it is unclear whether long-term running exert different effects on increasing BDNF levels in dorsal and ventral DGs in WT and Fmr1 KO mice.

In the present study, we have demonstrated that voluntary running enhances neurogenesis in both WT and Fmr1 KO mice, but with a region-specific impact on neurogenesis process in the dorsal and ventral DGs. Exercise only increased cell survival in the dorsal DG of Fmr1 KO mice, but enhanced cell survival in ventral DG of WT mice. These data indicate that physical exercise may regulate hippocampal neurogenesis differently in WT and Fmr1 KO mice.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts for this work.

REFERENCES

- [1]. Turner G, Webb T, Wake S, Robinson H. Prevalence of fragile X syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1996;64(1):196–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Song F, Barton P, Sleightholme V, Yao G, Fry-Smith A. Screening for fragile X syndrome: A literature review and modelling study. Health Technol Assess (Rockv). 2003;7(16). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Pieretti M, Zhang F, Fu Y-H, Warren ST, Oostra BA, Caskey CT, et al. Absence of expression of the FMR-1 gene in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991;66(4):817–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Wang T, Bray SM, Warren ST. New perspectives on the biology of fragile X syndrome. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22(3):256–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Reiss AL, Hall SS. Fragile X Syndrome: Assessment and Treatment Implications. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2007;16(3):663–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Scotto-Lomassese S, Nissant A, Mota T, Néant-Féry M, Oostra BA, Greer CA, et al. Fragile X mental retardation protein regulates new neuron differentiation in the adult olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2011;31(6):2205–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Saffary R, Xie Z. FMRP Regulates the Transition from Radial Glial Cells to Intermediate Progenitor Cells during Neocortical Development. J Neurosci. 2011;31(4):1427–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Hinds HL, Ashley CT, Sutcliffe JS, Nelson DL, Warren ST, Housman DE, et al. Tissue specific expression of FMR–1 provides evidence for a functional role in fragile X syndrome. Nat Genet. 1993;3(1):36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Lu R, Wang H, Liang Z, Ku L, O’donnell WT, Li W, et al. The fragile X protein controls microtubule-associated protein 1B translation and microtubule stability in brain neuron development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(42):15201–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Abitbol M, Menini C, Delezoide A-L, Rhyner T, Vekemans M, Mallet J. Nucleus basalis magnocellularis and hippocampus are the major sites of FMR-1 expression in the human fetal brain. Nat Genet. 1993;4(2):147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Guo W, Allan AM, Zong R, Zhang L, Johnson EB, Schaller EG, et al. Ablation of Fmrp in adult neural stem cells disrupts hippocampus-dependent learning. Nat Med. 2011;17(5):559–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Eadie BD, Zhang WN, Boehme F, Gil-Mohapel J, Kainer L, Simpson JM, et al. Fmr1 knockout mice show reduced anxiety and alterations in neurogenesis that are specific to the ventral dentate gyrus. Neurobiol Dis [Internet] 2009. [cited 2014 Dec 22]; 36(2):361–73. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19666116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].National Fragile X Foundation. Treatment and Intervention — National Fragile X Foundation.

- [14]. Anderson P, Morris R, Amaral D, Bliss T, O’Keefe J. The Hippocampus Book 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, Alborn A-M, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 1998;4(11):1313–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. van Praag H, Schinder AF, Christie BR, Toni N, Palmer TD, Gage FH. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature. 2002;415:1030–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(3):266–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. van Praag H, Christie BR, Sejnowski TJ, Gage FH. Running enhances neurogenesis, learning, and long-term potentiation in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci [Internet] 1999. [cited 2011 Dec 3];96(23)13427–31. Available from: http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/abstract/96/23/13427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Kronenberg G, Reuter K, Steiner B, Brandt MD, Jessberger S, Yamaguchi M, et al. Subpopulations of proliferating cells of the adult hippocampus respond differently to physiologic neurogenic stimuli. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467(4):455–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Van der Borght K, Havekes R, Bos T, Eggen BJL, Van der Zee EA. Exercise improves memory acquisition and retrieval in the Y-maze task: Relationship with hippocampal neurogenesis. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121(2):324–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Bolz L, Heigele S, Bischofberger J. Running Improves Pattern Separation during Novel Object Recognition. Brain Plast. 2015;1(1):129–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Tajiri N, Yasuhara T, Shingo T, Kondo A, Yuan W, Kadota T, et al. Exercise exerts neuroprotective effects on Parkinson’s disease model of rats. Brain Res. 2010;1310:200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Yau SY, Li A, Hoo RLC, Ching YP, Christie BR, Lee TMC, et al. Physical exercise-induced hippocampal neurogenesis and antidepressant effects are mediated by the adipocyte hormone adiponectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet] 2014. [cited 2016 Oct 5];111(44)15810–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25331877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Patten AR, Yau SY, Fontaine CJ, Meconi A, Wortman RC, Christie BR. The Benefits of Exercise on Structural and Functional Plasticity in the Rodent Hippocampus of Different Disease Models. Brain Plast. 2015;1(1):97–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Eadie BD, Redila VA, Christie BR. Voluntary exercise alters the cytoarchitecture of the adult dentate gyrus by increasing cellular proliferation, dendritic complexity, and spine density. J Comp Neurol. 2005;486(1):39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Yau SY, Chiu C, Vetrici M, Christie BR. Chronic minocycline treatment improves social recognition memory in adult male Fmr1 knockout mice. Behav Brain Res [Internet] 2016. [cited 2017 Oct 21];312:77–83. Available from http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0166432816303692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Yau SY, Bostrom CA, Chiu J, Fontaine CJ, Sawchuk S, Meconi A, et al. Impaired bidirectional NMDA receptor dependent synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus of adult female Fmr1 heterozygous knockout mice. Neurobiol Dis [Internet] 2016. [cited 2017 Oct 21];96 261–70. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27659109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Bostrom CA, Majaess N-M, Morch K, White E, Eadie BD, Christie BR. Rescue of NMDAR-dependent synaptic plasticity in Fmr1 knock-out mice. Cereb Cortex 2015. [Internet] [cited 2015 Nov 20];25(1)271–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23968838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Yau S-Y, Lau BW-M, Tong J-B, Wong R, Ching Y-P, Qiu G, et al. Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Dendritic Plasticity Support Running-Improved Spatial Learning and Depression-Like Behaviour in Stressed Rats. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Gil JMAC, Mohapel P, Araújo IM, Popovic N, Li J-Y, Brundin P, et al. Reduced hippocampal neurogenesis in R6/2 transgenic Huntington’s disease mice. Neurobiol Dis. 2005;20:744–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Kempermann G, Song H, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the Adult Hippocampus. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7(9):a018812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Bednarczyk MR, Aumont A, Décary S, Bergeron R, Fernandes KJL. Prolonged voluntary wheel-running stimulates neural precursors in the hippocampus and forebrain of adult CD1 mice. Hippocampus. 2009;19(10):913–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Clark PJ, Kohman RA, Miller DS, Bhattacharya TK, Haferkamp EH, Rhodes JS. Adult hippocampal neurogenesis and c-Fos induction during escalation of voluntary wheel running in C57BL/6J mice. Behav Brain Res. 2010;213(2):246–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Kitamura T, Sugiyama H. Running wheel exercises accelerate neuronal turnover in mouse dentate gyrus. Neurosci Res. 2006;56(1):45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Mineur YS, Sluyter F, de Wit S, Oostra BA, Crusio WE. Behavioral and neuroanatomical characterization of theFmr1 knockout mouse. Hippocampus. 2002;12(1):39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36]. McNaughton CH, Moon J, Strawderman MS, Maclean KN, Evans J, Strupp BJ. Evidence for social anxiety and impaired social cognition in a mouse model of fragile X syndrome. Behav Neurosci 2008. [Internet] [cited 2016 Feb 11];122(2)293–300. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18410169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Bostrom C, Yau S-Y, Majaess N, Vetrici M, Gil-Mohapel J, Christie BR. Hippocampal dysfunction and cognitive impairment in Fragile-X Syndrome. Neurosci Biobehav Rev [Internet] 2016. [cited 2017 Oct 21];68:563–74. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0149763416301294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Mineur YS, Huynh LX, Crusio WE. Social behavior deficits in the Fmr1 mutant mouse. Behav Brain Res. 2006;168(1):172–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39]. Santarelli L, Saxe M, Gross C, Surget A, Battaglia F, Dulawa S, et al. Requirement of Hippocampal Neurogenesis for the Behavioral Effects of Antidepressants. Science (80-) 2003;301(564). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40]. Banasr M, Soumier A, Hery M, Mocaër E, Daszuta A. Agomelatine, a New Antidepressant, Induces Regional Changes in Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(11):1087–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41]. Boldrini M, Underwood MD, Hen R, Rosoklija GB, Dwork AJ, John Mann J, et al. Antidepressants increase neural progenitor cells in the human hippocampus. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(11):2376–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42]. Ernst C, Olson AK, Pinel JP, Lam RW, Christie BR. Antidepressant effects of exercise: Evidence for an adult-neurogenesis hypothesis? Rev Psychiatr Neurosci. 2006;31(2):84–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43]. Yau SY, Li A, Sun X, Fontaine CJ, Christie BR, So K-F. Potential Biomarkers for Physical Exercise - Induced Brain Health In:Wang M, Witzmann F, editors. Role of Biomarkers in Medicine. Intech; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [44]. Cotman CW, Berchtold NC. Exercise: A behavioral intervention to enhance brain health and plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25(6):295–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45]. Lee J, Duan W, Mattson MP. Evidence that brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for basal neurogenesis and mediates, in part, the enhancement of neurogenesis by dietary restriction in the hippocampus of adult mice. J Neurochem. 2002;82(6):1367–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46]. Lauterborn JC, Rex CS, Kramar E, Chen LY, Pandyarajan V, Lynch G, et al. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Rescues Synaptic Plasticity in a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome. J Neurosci. 2007;27(40):10685–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]