Abstract

Previous studies have reported that miR-27a-3p is down-regulated in the serum of patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), but the implication of miR-27a-3p down-regulation in post-ICH complications remains elusive. Here we verified miR-27a-3p levels in the serum of ICH patients by real-time PCR and observed that miR-27a-3p is also significantly reduced in the serum of these patients. We then further investigated the effect of miR-27a-3p on post-ICH complications by intraventricular administration of a miR-27a-3p mimic in rats with collagenase-induced ICH. We found that the hemorrhage markedly reduced miR-27a-3p levels in the hematoma, perihematomal tissue, and serum and that intracerebroventricular administration of the miR-27a-3p mimic alleviated behavioral deficits 24 h after ICH. Moreover, ICH-induced brain edema, vascular leakage, and leukocyte infiltration were also attenuated by this mimic. Of note, miR-27a-3p mimic treatment also inhibited neuronal apoptosis and microglia activation in the perihematomal zone. We further observed that the miR-27a-3p mimic suppressed the up-regulation of aquaporin-11 (AQP11) in the perihematomal area and in rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs). Moreover, miR-27a-3p down-regulation increased BMEC monolayer permeability and impaired BMEC proliferation and migration. In conclusion, miR-27a-3p down-regulation contributes to brain edema, blood–brain barrier disruption, neuron loss, and neurological deficits following ICH. We conclude that application of exogenous miR-27a-3p may protect against post-ICH complications by targeting AQP11 in the capillary endothelial cells of the brain.

Keywords: brain, endothelium, microRNA (miRNA), aquaporin, post-transcriptional regulation, blood–brain barrier, brain injury, intracerebral hemorrhage, miR-27a-3p, neurological deficit

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH),2 accounting for 10–15% of all strokes, is the most devastating type of stroke with high morbidity and mortality (1). Unlike advances in ischemic stroke treatment, management of ICH is largely supportive via strategies aiming to limit further brain injury and associated complications (2). Perihematomal edema, which develops immediately after ICH and peaks several days later, is one of the major complications of ICH (3, 4). It is known that post-ICH edema formation can lead to intracranial hypertension and herniation and contribute to ICH-induced neurologic deficits and even fatality (3, 5). In addition, clinical evidence indicates an association between the severity of perihematomal edema and a poor outcome in patients with ICH (6–8). Hence, management of brain edema is recommended as part of neurointensive care for patients with ICH (2).

MicroRNAs, 18–22 nucleotides in length, are a class of noncoding RNAs that play fundamental roles in posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression (9). By binding to mRNAs specifically at the 3′ UTR through perfect or imperfect complementation, miRNAs induce either translational repression or RNA degradation in cells (9, 10). miRNAs are normally present in a stable pattern in blood, and dysregulation of serum miRNAs has been implicated in cancer and cardiovascular events as well as brain injuries such as ischemic stroke and ICH (11–13). Thus, serum miRNAs are considered to be potential biomarkers for disease diagnosis, and they may be useful for the development of targeted therapies.

Previously, an miRNA array revealed a group of miRNAs that were up- or down-regulated in the serum of ICH patients, and miR-27a-3p was one of the down-regulated miRNAs (14). However, the implications of miR-27a-3p down-regulation in the pathogenesis of post-ICH complications are unclear. Interestingly, a reduced level of miR-27a-3p was also observed in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, and miR-27a-3p reduction was more prominent in those with vasospasm (15). These findings suggest a potential function of miR-27a-3p in the maintenance of cerebrovascular structure and function following hemorrhage. In this study, an miR-27a-3p mimic was administrated into the brain ventricle of rats with ICH to investigate the role of miR-27a-3p in post-ICH pathogenesis. The effects of miR-27a-3p on post-ICH brain edema, blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, neuronal apoptosis, and microglia activation in the perihematomal zone as well as animal behaviors were assessed. Furthermore, a potential miR-27a-3p target, aquaporin-11 (AQP11), was found to be up-regulated in the perihematomal area, and the specific targeting was verified in rat brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs).

Results

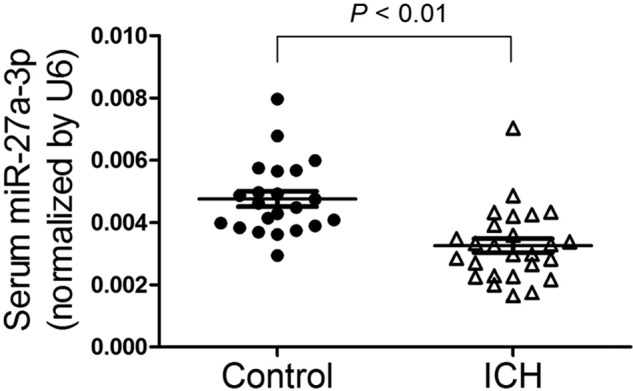

miR-27a-3p is down-regulated in the serum of patients with ICH

To verify previous miRNA array data (14), serum levels of miR-27a-3p in ICH patients and healthy subjects were measured by real-time PCR. As shown in Fig. 1, the level of miR-27a-3p in ICH patients was 31.6% lower compared with that in healthy subjects. This result confirmed down-regulation of miR-27a-3p in the serum of ICH patients, but it may not be specific for ICH.

Figure 1.

MiR-27a-3p is down-regulated in the serum of patients with ICH. The levels of miR-27a-3p in the serum of ICH patients (n = 26) and healthy subjects (n = 22) were determined by real-time PCR.

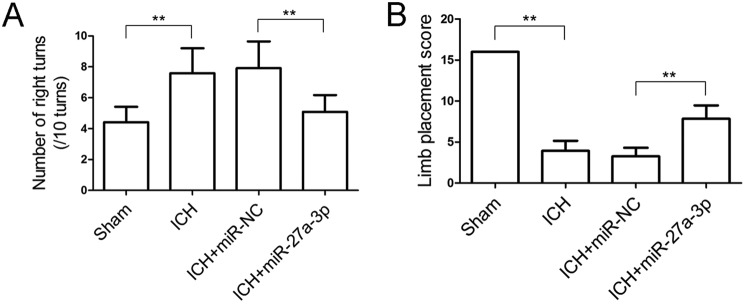

miR-27a-3p mimic alleviates behavioral deficits in rats after ICH

To investigate the implications of miR-27a-3p down-regulation in post-ICH pathogenesis, an miR-27a-3p mimic was given to rats with collagenase-induced ICH by intracerebroventricular administration. Behavioral assessment was conducted 24 h after ICH induction and miRNA treatment. As shown in Fig. 2, animals with ICH showed a markedly increased frequency of right turns (Fig. 2A) and a lower limb placement score (Fig. 2B) compared with the sham-operated animals, presenting typical post-ICH behavioral deficits. Following ICH, rats administered the miR-27a-3p mimic showed significant improvements in the corner test and limb placement test compared with miR-NC-treated rats, implying that the miR-27a-3p mimic could alleviate ICH-induced neurological deficits.

Figure 2.

Intracerebroventricular administration of the miR-27a-3p mimic improves behavioral performance in rats with ICH. A and B, corner turn test (A) and limb placement test (B) were performed 24 h after ICH and miRNA treatment (n = 12/group). **p < 0.01.

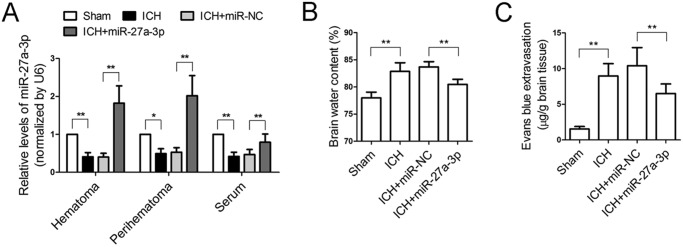

Restoration of miR-27a-3p reduces brain edema and BBB permeability after ICH

The levels of miR-27a-3p in the serum and perihematomal and hematomal areas of four groups of rats were measured by real-time PCR. The results showed that the levels of miR-27a-3p dropped significantly in the serum and perihematomal and hematomal masses 24 h after ICH (Fig. 3A). Intracerebroventricular administration of the miR-27a-3p mimic achieved successful delivery to the perihematomal and hematomal areas and also maintained the serum level of miR-27a-3p after ICH (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Intracerebroventricular administration of the miR-27a-3p mimic reduces brain edema and maintains BBB permeability following ICH. A, the levels of miR-27a-3p in rat serum, perihematomal tissue, and the hematomal region were measured by real-time PCR 24 h after ICH (n = 6/group). B, brain water content was measured 24 h after ICH induction and miRNA treatment (n = 6/group). C, Evans blue extravasation assay was performed to assess BBB permeability following ICH (n = 6/group). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

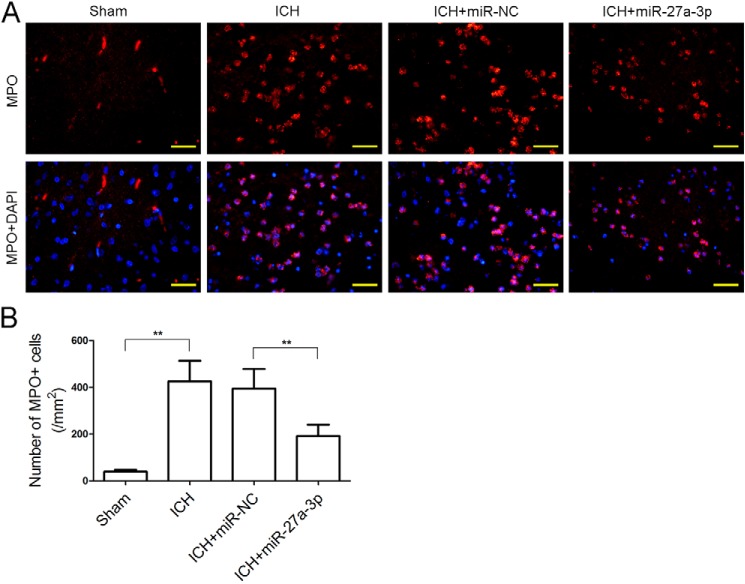

Brain edema and BBB permeability in ICH rats with or without administration of the miR-27a-3p mimic were examined. Compared with the sham group, ICH markedly increased the brain water content, whereas ICH-induced brain edema was significantly attenuated by treatment with the miR-27a-3p mimic (Fig. 3B). An Evans blue extravasation assay revealed that vascular leakage in the ICH group was significantly higher than in the sham group, whereas the miR-27a-3p mimic significantly reduced cerebrovascular permeability after ICH (Fig. 3C). In addition, leukocyte infiltration to the perihematomal zone was examined by immunofluorescent staining with MPO. The number of MPO-positive cells in the perihematomal tissue of ICH rats was profoundly increased compared with normal brain parenchyma of sham-operated rats (426 ± 88 versus 39 ± 8). By contrast, administration of the miR-27a-3p mimic significantly reduced the number of infiltrated leukocytes (192 ± 48) (Fig. 4, A and B). These results demonstrated that intracerebral administration of the miR-27a-3p mimic decreased edema formation and protected BBB function following ICH.

Figure 4.

The miR-27a-3p mimic inhibits leukocyte infiltration into the perihematomal area. A and B, immunofluorescent staining of MPO was performed to detect leukocyte infiltration (n = 5/group; scale bars = 33.3 μm). **p < 0.01.

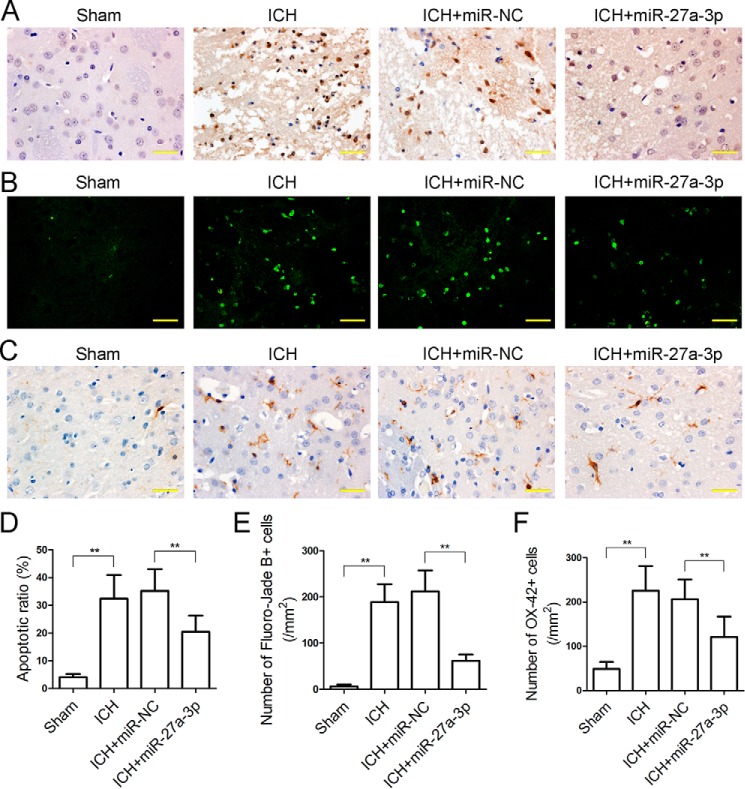

The miR-27a-3p mimic inhibits neuronal apoptosis and microglia activation in the perihematomal zone

Apoptotic cells in the perihematomal area were detected by TUNEL assay. ICH led to a markedly increased rate of apoptotic cells in the perihematomal area (32.41% ± 8.52%), whereas the miR-27a-3p mimic significantly reduced the apoptotic rate in perihematomal tissue (20.47% ± 5.85%) (Fig. 5, A and D). Degenerating neurons were labeled with Fluoro-Jade B stain. The number of positively stained neurons was significantly increased in the perihematomal area of ICH rats (189 ± 39), whereas the miR-27a-3p mimic reduced the number of dying neurons adjacent to the hematoma (62 ± 14) (Fig. 5, B and E). In addition, microglia activation was assessed by immunohistochemical staining with OX-42. The number of OX-42-positive microglia in the perihematomal area was remarkably elevated in the ICH group (226 ± 56), and it was significantly reduced by miR-27a-3p mimic treatment (121 ± 46) (Fig. 5, C and F). Overall, these results indicated that the miR-27a-3p mimic reduced neuronal apoptosis and microglia activation in the perihematomal area.

Figure 5.

The miR-27a-3p mimic inhibits neuronal apoptosis and microglia activation in the perihematomal area. A, TUNEL staining was performed to detect apoptotic cells in the perihematomal zone (scale bars = 33.3 μm). B, dying neurons in the perihematomal area were labeled by Fluoro-Jade B stain (scale bars = 33.3 μm). C, immunohistochemical staining of OX-42, a marker of activated microglia, in the perihematomal zone (scale bars = 33.3 μm). D–F, statistical analyses of the TUNEL apoptotic ratio (D), Fluoro-Jade B–positive cells (E), and OX-42–positive cells (F) in the perihematomal area were performed based on the above staining images (n = 5/group). *p < 0.05.

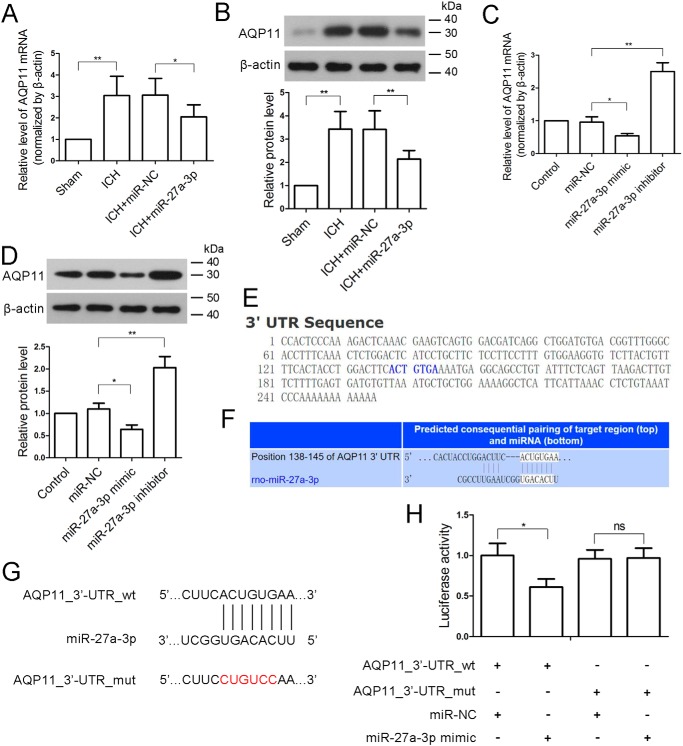

miR-27a-3p targets AQP11 in BMECs

Next we explored potential miR-27a-3p targets that were involved in the pathological changes following ICH. The expression of AQP11 was found to be significantly increased at both the mRNA and protein levels in the perihematomal region of ICH rats compared with sham-operated brain parenchyma (Fig. 6, A and B). Compared with miR-NC, the miR-27a-3p mimic significantly attenuated the elevation of AQP11 in perihematomal tissue, suggesting that AQP11 may be a target of miR-27a-3p. We also found that the expression of AQP1 was basically unchanged (Fig. S1). As AQP11 is highly expressed in the endothelium of brain capillaries (16), BMECs were isolated to verify the inhibitory effect of miR-27a-3p on AQP11 expression. In BMECs, the expression levels of AQP11 mRNA and protein were significantly decreased by the miR-27a-3p mimic and increased by an miR-27a-3p inhibitor (Fig. 6, C and D), which was consistent with in vivo findings. Based on the bioinformatics analysis, AQP11 may be a target of miR-27a-3p (Fig. 6, E–G). Furthermore, a Dual-Luciferase assay was performed in BMECs to validate the direct targeting of miR-27a-3p on the 3′ UTR of AQP11 mRNA. Compared with miR-NC, the miR-27a-3p mimic significantly reduced luciferase activity in AQP11_3′-UTR_WT but not AQP11_3′ UTR_mut (Fig. 6H), confirming direct targeting of AQP11 by miR-27a-3p.

Figure 6.

miR-27a-3p directly targets the 3′ UTR of the AQP11 transcript. A and B, 24 h after ICH, the levels of AQP11 mRNA and AQP11 protein in the perihematomal tissues were determined by real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively (n = 6/group). β-Actin was used as an internal control. C and D, rat BMECs were isolated and transfected with miR-NC, the miR-27a-3p mimic, or the miR-27a-3p inhibitor, and the levels of AQP11 mRNA and AQP11 protein were measured 24 h after transfection. β-Actin was used as an internal control. E, sequence of AQP11_3′ UTR. F and G, alignment of miR-27a-3p with the 3′ UTR of AQP11. The miR-27a-3p binding site in the 3′ UTR of AQP11 was mutated (ACUGUGA to CUGUCCA). H, a Dual-Luciferase reporter assay was performed in BMECs to verify direct targeting of miR-27a-3p on the 3′ UTR of AQP11. The in vitro experiments were repeated three times. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

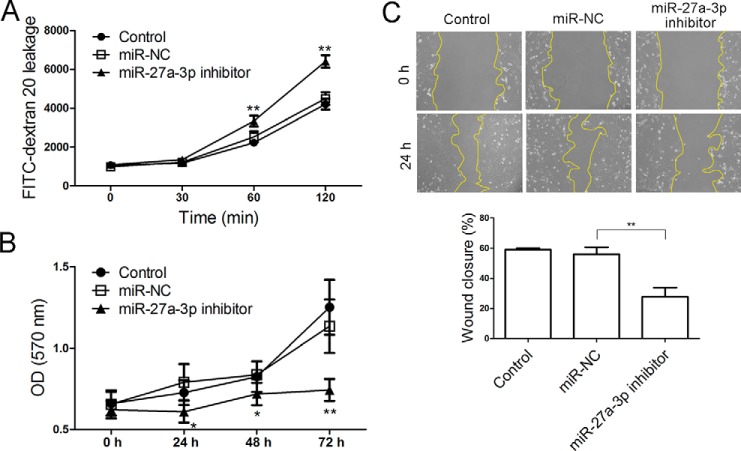

Down-regulation of miR-27a-3p increased BMEC monolayer leakage and inhibits proliferation and migration of BMECs

To investigate the impact of miR-27a-3p down-regulation on BMECs as in the context of ICH, BMECs were transfected with an miR-27a-3p inhibitor for the evaluation of cellular behavior. As shown in Fig. 7A, down-regulation of miR-27a-3p significantly increased the passage of dextran 20 through the BMEC monolayer, suggesting a critical role of miR-27a-3p in the maintenance of endothelial layer permeability. In addition, an MTT assay indicated that the miR-27a-3p inhibitor significantly suppressed proliferation of BMECs in vitro (Fig. 7B). Moreover, a scratch wound assay showed that the motility of BMECs was greatly impaired when miR-27a-3p was inhibited (Fig. 7C). Thus, inhibition of miR-27a-3p increased the permeability of the BMEC monolayer and reduced the proliferative and migratory abilities of BMECs.

Figure 7.

Antagonizing miR-27a-3p increases BMEC monolayer permeability and blocks BMEC proliferation and migration. A, the fluorescence intensity of FITC–dextran 20 that passed through a BMEC monolayer over 120 min was measured. B, an MTT assay was performed to assess the proliferation of BMECs that were transfected with miR-NC or the miR-27a-3p inhibitor. C, a scratch wound assay was conducted to evaluate the motility of BMECs. The experiments were repeated three times. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus miR-NC-transfected cells.

Discussion

In this study, we first validated the down-regulation of miR-27a-3p in the serum of patients with ICH. Previous studies have reported that miR-27a is also down-regulated in other brain diseases, including Huntington's disease and traumatic brain injury; however, its elevation exerts a cerebrally protective effect (17–19). Down-regulation of miR-27a-3p might be not specific for ICH. Further studies will be taken into consideration to address this query. Moreover, in a rat ICH model, miR-27a-3p was down-regulated in the serum and hematoma and perihematomal tissues, and intracerebroventricular administration of an miR-27a-3p mimic alleviated ICH-induced brain edema, BBB disruption, neuronal apoptosis, and neurologic deficits. These observations indicate that down-regulation of miR-27a-3p is not a random event following ICH. Instead, miR-27a-3p is critical in the maintenance of brain homeostasis post-ICH.

Previous studies have clarified the origin of circulating miRNAs (20, 21). In brief, primary miRNAs with a 5′ cap and 3′ poly(A) tail are transcribed in the nucleus and then cleaved by Drosha into precursors. Precursor miRNAs are then exported into the cytoplasm to form mature miRNAs. Finally, mature miRNAs are transported into the bloodstream by binding to RNA-binding proteins, microvesicles, exosomes, or multivesicular bodies. Corsten et al. (22) have reported that circulating miR-208b and miR-499 are released from injured cardiomyocytes and reflect myocardial damage in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Based on this evidence, the increase in miR-27a-3p may originate from injured brain tissues and not from blood cells.

The BBB is a physical and physiological barrier between the blood and brain, and disruption of BBB integrity is a well-documented cause of brain edema following a variety of brain injuries (23). After ICH, BBB permeability increases remarkably in the tissue surrounding the clot prior to the occurrence of significant edema, resulting in severe acute edema around the hemorrhage (24). Moreover, increased BBB permeability facilitates the infiltration of leukocytes and inflammatory mediators to the perihematomal zone, leading to the activation of resident microglia and secondary neuronal injury (25). Activated microglia, in turn, aggravate ICH-induced brain injury and neurobehavioral deficits (26). Thus, maintaining the integrity of the BBB is crucial for minimizing secondary brain injury after ICH. In this study, restoration of cerebral miR-27a-3p after ICH reduced BBB leakage, brain edema, leukocyte infiltration, microglia activation, and neuronal apoptosis in the perihematomal area and also improved behavioral performance in rats. Musto et al. (27) have found that miR-27a-3p protects differentiating embryonic stem cells from BMP4-induced apoptosis by targeting Smad5. In addition, Chen et al. (28) have demonstrated that miR-27a-3p alleviates hypoxia-induced neuronal apoptosis through inhibition of apoptotic protease activating factor-1 (Apaf-1). In this study, we hypothesized that miR-27a-3p might suppress neuronal apoptosis through modulation of its target genes. Future studies are required to further verify our hypothesis. Furthermore, the in vitro permeability assay demonstrated that antagonism of miR-27a-3p in BMECs increased leakage of the BMEC monolayer. Thus, our data suggest a protective role of miR-27a-3p after ICH against post-ICH complications, at least partly through the maintenance of BBB integrity and function.

miRNAs have been demonstrated to play important roles in the regulation of endothelial cell function and angiogenesis (29). They could be pro-angiogenic or anti-angiogenic depending on their specific targets (30, 31). miR-27a is highly expressed in endothelial cells, but the function of miR-27a in endothelial cells is controversial. It has been shown that inhibition of miR-27a reduces endothelial cell sprouting, induces endothelial cell repulsion in vitro, and impairs embryonic vasculogenesis in zebrafish (32). These previous findings demonstrate a supportive role of miR-27a in endothelial cell function and vessel formation. By contrast, Young et al. (33) found that ectopic expression of miR-27a blocked capillary tube formation in vitro and that a general miR-27a inhibitor promotes angiogenesis and reduces vascular leakage following ischemic limb injury. In our study, down-regulation of miR-27a-3p was associated with increased BBB permeability, whereas restoration of miR-27a-3p significantly reduced BBB permeability. Moreover, our in vitro experiments demonstrated that the miR-27a-3p inhibitor impaired the proliferation of BMECs, which is in line with the pro-proliferative role of miR-27a in endothelial cells (8). In addition, inhibition of miR-27a-3p also weakened the motility of BMECs. Thus, our data substantiate the supportive role of miR-27a-3p in normal endothelial cell activity and BBB integrity after ICH.

AQPs, a family of water channel proteins expressed in various cell types, are implicated in brain edema formation (34). Despite a low protein identity (∼11%) with conventional AQPs such as AQP-1 and 4, AQP11 is indeed a functional water channel that permeates both water and glycerol (35–37). AQP11 is present in high abundance in the brain and mainly localized at the epithelium of the choroid plexus and the endothelium of brain capillaries (16). The localization of AQP11 suggests its possible involvement in the permeability of the BBB and the pathophysiology of brain edema. Although the brain of AQP11-deficient mouse displays normal morphology and an intact BBB (16), up-regulation of AQP11 following ICH in our study is associated with increased BBB permeability and edema formation. The possible explanation is that water transport can be compensated by other AQPs in the absence of AQP11, whereas excessive AQP11 disrupts water homeostasis and BBB integrity. Moreover, we demonstrate that miR-27a-3p inhibits the expression of AQP11 in BMECs by directly targeting the 3′ UTR of AQP11. This provides a molecular mechanism for the posttranscriptional regulation of AQP11. However, the precise function of AQP11 in BBB function and edema formation needs to be elucidated in future studies.

In conclusion, restoration of miR-27a-3p reduces brain edema, maintains BBB permeability, inhibits neuronal loss, and alleviates neurological deficits in rats with ICH. The protective effect of miR-27a-3p may be mediated by inhibiting AQP11 in the endothelium of brain capillaries.

Experimental procedures

Patients

Twenty-six patients with acute spontaneous ICH, aged ≥ 18 years and admitted within 48 h of onset were included in this study. Blood samples were drawn upon admission, and the sera were frozen for later examination. Serum samples from 22 age-matched healthy subjects were used as controls. Written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled ICH patients and healthy subjects. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

Real-time PCR

Total RNAs were extracted using the RNApure Total RNA Fast Extraction Kit (BioTeke, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To measure miR-27a-3p, miR-27a-3p was extended with a specific loop primer, 5′-GTTGGCTCTGGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTCGCACCAGAGCCAACGCGGAA-3′, under reverse transcription by super Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (BioTeke). Thereafter, quantitative real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green I Master Mix (Solarbio, Beijing, China), and the signals were detected by an Exicycler 96 quantitative PCR analyzer (Bioneer, Daejeon, Korea). The following primers were used: miR-27a-3p, 5′-CGCGTTCACAGTGGCTAAGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTGCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTC-3′ (reverse); U6, 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′ (forward) and 5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′ (reverse); AQP11, 5′-GCCTTCGTCCTGGAGTTTCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCACCAAGGAAAAGAAGTAGAT-3′ (reverse); β-actin, 5′-GGAGATTACTGCCCTGGCTCCTAGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GGCCGGACTCATCGTACTCCTGCTT-3′ (reverse). U6 and β-actin served as the internal reference genes for miR-27a-3p and AQP11, respectively.

Establishment of the ICH model and administration of the miR-27a-3p mimic

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (weighing 250–280 g) were randomly assigned to four groups. ICH was induced by collagenase according to a method described previously (38, 39). Briefly, the rats were anesthetized with 50 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital via intraperitoneal injection and fixed in a stereotaxic frame in a prone position. After the frontal bone was exposed, a burr hole (1 mm in diameter) was made using a dental drill, and a 26-gauge needle was inserted into the right basal ganglia (stereotaxic coordinates: 0.2 mm anterior, 3 mm right lateral to the bregma, and 6 mm ventral to the skull). Collagenase VII (0.5 units in 2 μl of saline) was slowly infused into the brain at a rate of 0.4 μl/min using a microinjection pump. For the sham group, an equal volume of saline was infused into the right basal ganglia through a burr hole drilled at the same position. After induction of ICH, the miR-27a-3p mimic or negative control miRNA (miR-NC) (10 μm; GenePharm, Shanghai, China) was mixed with EntransterTM in vivo (Engreen, Beijing, China). The mixture, in a 5-μl final volume, was injected into the right lateral ventricle (stereotaxic coordinates: 0.8 mm posterior, 1.5 mm right lateral to the bregma, and 4.5 mm ventral to the skull) at a flow rate of 0.5 μl/min through another 1-mm burr hole. The rats in the sham group and the ICH group received an intracerebroventricular injection of an equal volume of the transfection reagent. Thereafter, the skin was sutured, and the rats were allowed recovery and free access to food and water for 24 h. The experiments were performed in accordance with the Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals of the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of China Medical University.

Behavioral tests

Behavioral tests, including the corner test and limb placement test, were performed 24 h after ICH induction and miRNA administration. For the corner test, the rats were placed in a 30° corner and allowed to turn left or right freely to exit the corner. The number of right turns was recorded for 10 trials per rat.

The limb placement test consisted of six subtests as described previously (40). Each subtest was scored as follows: 0 for no placing, 1 for incomplete and/or delayed (>2 s) placing, and 2 for immediate and correct placing. The left forepaw was graded in all subtests, and the left hind limb was graded in subtests 4 and 6. The rat was held gently by the examiner in subtests 1 through 4. In subtest 1, limb placing was tested by slowly lowering the rat toward a tabletop. For subtest 2, with the rat's forelimbs touching the table edge, the head of the rat was moved 45° upward. In subtest 3, forelimb placing was tested by facing the rat toward a table edge. In subtest 4, forelimb and hind limb placement were recorded when the left side of the rat body was moved toward the table edge. For subtest 5, the rat was placed on the table and gently pushed from behind toward the table edge to observe the rat's gripping on the edge. In subtest 6, the rat, with the left body side facing the table edge, was pushed laterally toward the table edge. Each rat obtained eight scores (six for the forelimb and two for the hind limb), and the full score was 16. The tests were scored by an experienced researcher who was blinded to group designation.

Blood sampling and brain tissue collection

The rats were euthanized after the behavioral tests. Blood was drawn from the inferior vena cava, and the serum was frozen for later determination of miR-27a-3p. The brain was divided into ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres of ICH. The perihematomal zone was defined as a 2-mm margin around the hematomal mass. The perihematomal and hematomal tissues were excised, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Measurement of brain water content

The ipsilateral hemisphere of the brain was weighed (wet weight) and then dried at 100 °C for 24 h to obtain the dry weight. Brain water content was calculated as (wet weight − dry weight)/wet weight × 100%.

Evans blue extravasation assay

Evans blue extravasation assay was performed to assess brain-blood barrier integrity. Evans blue dye (2%, 2 ml/kg; Wokai, Shanghai, China) was injected via the tail vein 24 h after ICH induction. Two h later, the rats were transcardially perfused with saline to flush out the intravascular dye. Subsequently, the brains were removed, weighed and incubated with formamide (1 ml/100 mg tissue) at 37 °C for 24 h to extract Evans blue. Thereafter, the samples were centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min, and the optical density (OD) of the supernatants was read at 632 nm. The content of Evans blue was determined based on a standard curve.

Immunofluorescence staining

The brains were fixed, paraffin-embedded, and cut into 5-μm sections. The sections were heated at 60 °C for 30 min, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated in descending concentrations of ethanol. Following antigen retrieval, the sections were blocked with goat serum and incubated with anti-myeloperoxidase (MPO) antibody (1:200 dilution; Boster, Wuhan, China) at 4 °C overnight. Thereafter, the sections were rinsed with PBs and incubated with Cy3-labeled goat-anti rabbit IgG (1:300 dilution; Beyotime, Haimen, China) for 1 h in the dark. Finally, cell nuclei were stained briefly with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. The perihematomal area was observed and imaged under a fluorescent microscope, and MPO-positive cells were quantified.

TUNEL assay and immunohistochemistry

Apoptotic cells in the perihematomal zone were characterized using an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Briefly, deparaffinized brain sections were permeabilized by incubation with Triton X-100, and endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 3% hydrogen peroxide. The broken DNA strands in the apoptotic cells were labeled by incubating the sections with TUNEL reaction mixture and converter peroxidase according to the kit instructions. Following washing with PBS, the sections were incubated with diaminobenzidine (Solarbio) for a chromogenic reaction, and the nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin.

Immunohistochemistry for OX-42 was performed to detect activated microglia in the perihematomal area. Following antigen retrieval, brain sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide, blocked with goat serum, and incubated with anti-OX-42 antibody (1:50 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX) at 4 °C overnight. After incubation with biotin-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse IgG (1:200 dilution, Beyotime) for 30 min at 37 °C, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated streptavidin (Beyotime) for 30 min at 37 °C and then treated with chromogenic diaminobenzidine. Following counterstaining with hematoxylin, the sections were dehydrated, mounted, and examined by light microscopy.

Fluoro-Jade B staining

Fluoro-Jade B staining was performed to detect dying neurons. Briefly, brain sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and incubated in 0.06% potassium permanganate for 10 min with gentle shaking. Subsequently, the sections were stained with Fluoro-Jade B (Millipore, Bedford, MA) for 20 min in the dark, followed by washing with distilled water, drying in a 50 °C oven for 5 min, and mounting. Fluoro-Jade B–positive neurons in the perihematomal area were counted under a fluorescence microscope.

Isolation of BMECs, cell culture, and transfection

Primary BMECs were isolated from neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats according to a method reported previously (41) with some modifications. After careful removal of the cerebellum, interbrain, white matter, brain stem, surface vessels, and leptomeninges, cerebral cortices were rinsed three times with PBS, minced into small pieces, and digested with 0.1% collagenase II (Gibco) at 37 °C for 30 min. The digested mixture was filtered through a 178-μm mesh and centrifuged at 156 × g for 8 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 20% BSA and centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The microvessels in the lower layer were digested with 0.1% collagenase II/dispase (Solarbio) at 37 °C for 1 h. After centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, the pellet was resuspended in DMEM (Gibco) and placed on top of 50% Percoll (Solarbio), followed by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 20 min. The cells were washed once with DMEM, centrifuged at 156 × g for 5 min, and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fatal bovine serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT) at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. BMECs were transfected with miR-NC, the miR-27a-3p mimic, or the miR-27a-3p inhibitor using the Lipofectamine LTX and PLUS reagents (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

Perihematomal tissues or BMECs were lysed on ice with radioimmune precipitation assay lysis buffer containing 1% phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (Beyotime). The lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and protein concentration in the supernatant was determined using a BCA assay kit (Beyotime). Forty micrograms of protein from each sample was separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 1 h and incubated with anti-AQP11 (1:400 dilution, Boster) or anti-AQP1 antibody (1:1,000 dilution; Bioss, Beijing, China) overnight at 4 °C. Following washing with 0.15% Tween 20–TBS four times for 5 min, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase–labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000 dilution, Beyotime) for 45 min at 37 °C. Subsequently, the immune complexes were visualized using ECL reagent (Beyotime). The membrane was stripped and reblotted with anti-β-actin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to verify equal protein loading and transfer. The intensities of target bands were analyzed using Gel-Pro Analyzer software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD), and the relative protein level was normalized to the internal control, β-actin.

Dual-Luciferase reporter assay

The 3′ UTR of AQP11 mRNA was PCR-amplified from a rat complementary DNA library using the following primers: 3′ URT_F, 5′-CAAGCTAGCCCACTCCCAAAGACTCAAAC-3′ (with an NheI restriction site) and 3′ UTR_R, 5′-CGCGTCGACTTGGGATTTACAGAGGTTTA-3′ (with a SalI restriction site). The amplified product was cloned into the pmirGLO firefly luciferase reporter vector (Promega, Waltham, MA) to generate pmirGLO-AQP11_3′ UTR_WT. pmirGLO-AQP11_3′ UTR_mut was obtained by PCR amplification using a point-mutated primer for the AQP11_3′ UTR. BMECs were transfected with pmirGLO-AQP11_3′ UTR_WT/pmirGLO-AQP11_3′ UTR_mut and miR-27a-3p mimic/miR-NC using Lipofectamine LTX and PLUS reagent. 48 h post-transfection, luciferase activity, as the ratio of firefly/Renilla activity, was measured using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay system (Promega).

BMEC monolayer permeability assay

BMECs were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells/Transwell chamber (Costar, Corning, NY). When the cells grew into a confluent monolayer, 0.01% FITC–dextran 20 (TdB, Uppsala, Sweden) was added to the medium in the upper chamber, and the medium in the lower chamber was collected 0, 30, 60, and 120 min later. The fluorescence intensity in the medium was measured by a microplate reader.

Cell proliferation assay

BMECs were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 3,000 cells/well and transfected with miR-NC or the miR-27a-3p inhibitor (5′-GCGGAACUUAGCCACUGUGAA-3′). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the medium was changed to fresh culture medium (0 h), and 0.5 mg/ml MTT (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to the medium at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h for 4-h incubation at 37 °C. Subsequently, the supernatant was carefully aspirated, and 150 μl of DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to each well to dissolve the violet crystals by vigorous shaking. A570 nm was measured by an ELX-800 microplate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). Each assay point was done in five replicates.

Scratch wound assay

BMECs were grown to a confluent monolayer and transfected with miR-NC or the miR-27a-3p inhibitor. Twenty-four hours later, a scratch was evenly generated by dragging a 1-ml pipette tip across the cell monolayer. The cells were washed and cultured with serum-free medium for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere consisting of 5% CO2. The cells were photographed at 0 h and 24 h post-scratching, and the percentage of wound closure was calculated.

Statistical analyses

Clinical data were expressed as mean ± S.E., and the two groups were compared using Student's t test. Experimental data were expressed as mean ± S.D. The behavior test results were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test with post hoc Dunn's test, and continuous variables were analyzed by analysis of variance with post hoc Newman-Keuls test. Statistical analyses were performed by employing GraphPad Prism 5.0. Regardless of the statistical tests used, a difference with p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Author contributions

T. X., F. J., J. W., L. T., and Y. W. data curation; T. X. and Y. Z. formal analysis; T. X., F. J., Y. Z., J. W., L. T., and Y. W. investigation; T. X. methodology; T. X. writing-original draft; F. J. and D. S. L. validation; D. S. L., F. S., and Z. H. conceptualization; D. S. L., F. S., and Z. H. writing-review and editing; Z. H. funding acquisition.

Supplementary Material

This study was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271291). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains Fig. S1.

- ICH

- intracerebral hemorrhage

- miRNA

- microRNA

- BBB

- blood–brain barrier

- BMEC

- brain microvascular endothelial cell

- MPO

- myeloperoxidase

- TUNEL

- terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- AQP

- aquaporin

- NC

- negative control

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium.

References

- 1. Qureshi A. I., Tuhrim S., Broderick J. P., Batjer H. H., Hondo H., and Hanley D. F. (2001) Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1450–1460 10.1056/NEJM200105103441907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balami J. S., and Buchan A. M. (2012) Complications of intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 11, 101–118 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70264-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xi G., Keep R. F., and Hoff J. T. (2002) Pathophysiology of brain edema formation. Neurosurg. Clin. N. Am. 13, 371–383 10.1016/S1042-3680(02)00007-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xi G., Keep R. F., and Hoff J. T. (2006) Mechanisms of brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 5, 53–63 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70283-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gong Y., Hua Y., Keep R. F., Hoff J. T., and Xi G. (2004) Intracerebral hemorrhage: effects of aging on brain edema and neurological deficits. Stroke 35, 2571–2575 10.1161/01.STR.0000145485.67827.d0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zazulia A. R., Diringer M. N., Derdeyn C. P., and Powers W. J. (1999) Progression of mass effect after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke 30, 1167–1173 10.1161/01.STR.30.6.1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Appelboom G., Bruce S. S., Hickman Z. L., Zacharia B. E., Carpenter A. M., Vaughan K. A., Duren A., Hwang R. Y., Piazza M., Lee K., Claassen J., Mayer S., Badjatia N., and Connolly E. S. Jr. (2013) Volume-dependent effect of perihaematomal oedema on outcome for spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhages. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 84, 488–493 10.1136/jnnp-2012-303160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang J., Arima H., Wu G., Heeley E., Delcourt C., Zhou J., Chen G., Wang X., Zhang S., Yu S., Chalmers J., Anderson C. S., and INTERACT Investigators (2015) Prognostic significance of perihematomal edema in acute intracerebral hemorrhage: pooled analysis from the intensive blood pressure reduction in acute cerebral hemorrhage trial studies. Stroke 46, 1009–1013 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ambros V. (2004) The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature 431, 350–355 10.1038/nature02871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rana T. M. (2007) Illuminating the silence: understanding the structure and function of small RNAs. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 23–36 10.1038/nrm2085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ng E. K., Li R., Shin V. Y., Jin H. C., Leung C. P., Ma E. S., Pang R., Chua D., Chu K. M., Law W. L., Law S. Y., Poon R. T., and Kwong A. (2013) Circulating microRNAs as specific biomarkers for breast cancer detection. PLoS ONE 8, e53141 10.1371/journal.pone.0053141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Di Stefano V., Zaccagnini G., Capogrossi M. C., and Martelli F. (2011) microRNAs as peripheral blood biomarkers of cardiovascular disease. Vascul. Pharmacol. 55, 111–118 10.1016/j.vph.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu D. Z., Tian Y., Ander B. P., Xu H., Stamova B. S., Zhan X., Turner R. J., Jickling G., and Sharp F. R. (2010) Brain and blood microRNA expression profiling of ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and kainate seizures. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 30, 92–101 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhu Y., Wang J. L., He Z. Y., Jin F., and Tang L. (2015) Association of altered serum microRNAs with perihematomal edema after acute intracerebral hemorrhage. PLoS ONE 10, e0133783 10.1371/journal.pone.0133783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stylli S. S., Adamides A. A., Koldej R. M., Luwor R. B., Ritchie D. S., Ziogas J., and Kaye A. H. (2017) miRNA expression profiling of cerebrospinal fluid in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J. Neurosurg. 126, 1131–1139 10.3171/2016.1.JNS151454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koike S., Tanaka Y., Matsuzaki T., Morishita Y., and Ishibashi K. (2016) Aquaporin-11 (AQP11) expression in the mouse brain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17, E861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ban J. J., Chung J. Y., Lee M., Im W., and Kim M. (2017) MicroRNA-27a reduces mutant hutingtin aggregation in an in vitro model of Huntington's disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 488, 316–321 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.05.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sun L., Zhao M., Wang Y., Liu A., Lv M., Li Y., Yang X., and Wu Z. (2017) Neuroprotective effects of miR-27a against traumatic brain injury via suppressing FoxO3a-mediated neuronal autophagy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 482, 1141–1147 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sabirzhanov B., Zhao Z., Stoica B. A., Loane D. J., Wu J., Borroto C., Dorsey S. G., and Faden A. I. (2014) Downregulation of miR-23a and miR-27a following experimental traumatic brain injury induces neuronal cell death through activation of proapoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. J. Neurosci. 34, 10055–10071 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1260-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhou S. S., Jin J. P., Wang J. Q., Zhang Z. G., Freedman J. H., Zheng Y., and Cai L. (2018) miRNAS in cardiovascular diseases: potential biomarkers, therapeutic targets and challenges. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 39, 1073–1084 10.1038/aps.2018.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. do Amaral A. E., Cisilotto J., Creczynski-Pasa T. B., and de Lucca Schiavon L. (2018) Circulating miRNAs in nontumoral liver diseases. Pharmacol. Res. 128, 274–287 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Corsten M. F., Dennert R., Jochems S., Kuznetsova T., Devaux Y., Hofstra L., Wagner D. R., Staessen J. A., Heymans S., and Schroen B. (2010) Circulating microRNA-208b and MicroRNA-499 reflect myocardial damage in cardiovascular disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3, 499–506 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.957415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Betz A. L., Iannotti F., and Hoff J. T. (1989) Brain edema: a classification based on blood-brain barrier integrity. Cerebrovasc. Brain Metab. Rev. 1, 133–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang G. Y., Betz A. L., Chenevert T. L., Brunberg J. A., and Hoff J. T. (1994) Experimental intracerebral hemorrhage: relationship between brain edema, blood flow, and blood-brain barrier permeability in rats. J. Neurosurg. 81, 93–102 10.3171/jns.1994.81.1.0093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gong C., Hoff J. T., and Keep R. F. (2000) Acute inflammatory reaction following experimental intracerebral hemorrhage in rat. Brain Res. 871, 57–65 10.1016/S0006-8993(00)02427-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang J., Rogove A. D., Tsirka A. E., and Tsirka S. E. (2003) Protective role of tuftsin fragment 1–3 in an animal model of intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann. Neurol. 54, 655–664 10.1002/ana.10750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Musto A., Navarra A., Vocca A., Gargiulo A., Minopoli G., Romano S., Romano M. F., Russo T., and Parisi S. (2015) miR-23a, miR-24 and miR-27a protect differentiating ESCs from BMP4-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 22, 1047–1057 10.1038/cdd.2014.198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen Q., Xu J., Li L., Li H., Mao S., Zhang F., Zen K., Zhang C. Y., and Zhang Q. (2014) MicroRNA-23a/b and microRNA-27a/b suppress Apaf-1 protein and alleviate hypoxia-induced neuronal apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 5, e1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Urbich C., Kuehbacher A., and Dimmeler S. (2008) Role of microRNAs in vascular diseases, inflammation, and angiogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 79, 581–588 10.1093/cvr/cvn156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang S., Aurora A. B., Johnson B. A., Qi X., McAnally J., Hill J. A., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., and Olson E. N. (2008) The endothelial-specific microRNA miR-126 governs vascular integrity and angiogenesis. Dev. Cell 15, 261–271 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Doebele C., Bonauer A., Fischer A., Scholz A., Reiss Y., Urbich C., Hofmann W. K., Zeiher A. M., and Dimmeler S. (2010) Members of the microRNA-17–92 cluster exhibit a cell-intrinsic antiangiogenic function in endothelial cells. Blood 115, 4944–4950 10.1182/blood-2010-01-264812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Urbich C., Kaluza D., Frömel T., Knau A., Bennewitz K., Boon R. A., Bonauer A., Doebele C., Boeckel J. N., Hergenreider E., Zeiher A. M., Kroll J., Fleming I., and Dimmeler S. (2012) MicroRNA-27a/b controls endothelial cell repulsion and angiogenesis by targeting semaphorin 6A. Blood 119, 1607–1616 10.1182/blood-2011-08-373886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Young J. A., Ting K. K., Li J., Moller T., Dunn L., Lu Y., Moses J., Prado-Lourenço L., Khachigian L. M., Ng M., Gregory P. A., Goodall G. J., Tsykin A., Lichtenstein I., Hahn C. N., et al. (2013) Regulation of vascular leak and recovery from ischemic injury by general and VE-cadherin-restricted miRNA antagonists of miR-27. Blood 122, 2911–2919 10.1182/blood-2012-12-473017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rump K., and Adamzik M. (2018) Function of aquaporins in sepsis: a systematic review. Cell Biosci. 8, 10 10.1186/s13578-018-0211-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yakata K., Tani K., and Fujiyoshi Y. (2011) Water permeability and characterization of aquaporin-11. J. Struct. Biol. 174, 315–320 10.1016/j.jsb.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ikeda M., Andoo A., Shimono M., Takamatsu N., Taki A., Muta K., Matsushita W., Uechi T., Matsuzaki T., Kenmochi N., Takata K., Sasaki S., Ito K., and Ishibashi K. (2011) The NPC motif of aquaporin-11, unlike the NPA motif of known aquaporins, is essential for full expression of molecular function. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 3342–3350 10.1074/jbc.M110.180968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Madeira A., Fernández-Veledo S., Camps M., Zorzano A., Moura T. F., Ceperuelo-Mallafré V., Vendrell J., and Soveral G. (2014) Human aquaporin-11 is a water and glycerol channel and localizes in the vicinity of lipid droplets in human adipocytes. Obesity 22, 2010–2017 10.1002/oby.20792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rosenberg G. A., Mun-Bryce S., Wesley M., and Kornfeld M. (1990) Collagenase-induced intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Stroke 21, 801–807 10.1161/01.STR.21.5.801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xi T., Jin F., Zhu Y., Wang J., Tang L., Wang Y., Liebeskind D. S., and He Z. (2017) MicroRNA-126–3p attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption, cerebral edema and neuronal injury following intracerebral hemorrhage by regulating PIK3R2 and Akt. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 494, 144–151 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.10.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ohlsson A. L., and Johansson B. B. (1995) Environment influences functional outcome of cerebral infarction in rats. Stroke 26, 644–649 10.1161/01.STR.26.4.644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. He Q. W., Xia Y. P., Chen S. C., Wang Y., Huang M., Huang Y., Li J. Y., Li Y. N., Gao Y., Mao L., Mei Y. W., and Hu B. (2013) Astrocyte-derived sonic hedgehog contributes to angiogenesis in brain microvascular endothelial cells via RhoA/ROCK pathway after oxygen-glucose deprivation. Mol. Neurobiol. 47, 976–987 10.1007/s12035-013-8396-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.