Abstract

The process of mental health intervention implementation with vulnerable populations is not well-described in the literature. The authors worked as a community-partnered team to adapt and pilot an empirically supported intervention program for mothers of infants and toddlers in an outpatient mental health clinic that primarily serves a low-income community. We used qualitative ethnographic methods to document the adaption of an evidence-based intervention, Mothering from the Inside Out, and the pilot implementation in a community mental health clinic. Seventeen mothers and their identified 0- to 84-month-old children were enrolled in the study. Key lessons from this implementation include (a) the importance of formative work to build community relationships and effectively adapt the intervention to meet the needs of the therapists and their clients, (b) the importance of designing plans for training and reflective supervision that fit within the flow of the clinic and can tolerate disruptions, and (c) that use of an interdisciplinary approach is feasible with the development of a plan for communication and the support of a trained reflective clinical supervisor. These key lessons advance the scientific knowledge available to healthcare managers and researchers who are looking to adapt mental health clinical interventions previously tested in clinical trials to implementation in community settings.

Keywords: mentalization, parenting, implementation, vulnerable population, mental health

RESUMEN:

Objetivo:

El proceso de implementatión de la intervención de salud mental con grupos vulnerables de la población no está bien descrito en la literatura. Los autores trabajaron como equipo en asociación con la comunidad para adaptar y experimentar en la practica un programa de intervention de apoyo empírico para madres de infantes y niños pequeñitos en una clínica de salud mental para pacientes externos que primariamente le sirve a una comunidad de bajos recursos económicos.

Metodos:

Usamos métodos etnográficos cualitativos para documentar la adaptación de MIO y la implementación del programa experimental en una clínica comunitaria de salud mental. Diecisiete madres y sus identificados niños de hasta 84 meses de edad fueron parte del estudio.

Resultados:

Entre las lecciones claves de esta implementación se incluyen: 1. La importancia del trabajo formativo para establecer relaciones comunitarias y adaptar eficazmente la intervention para satisfacer necesidades de terapeutas y sus clientes; 2. La importancia de diseñar planes para el entrenamiento y la supervision con reflexion que encajen dentro del trabajo diario de la clínica y puedan tolerar alteraciones; 3. El uso de un acercamiento interdisciplinario es posible con el desarrollo de un plan de comunicación y el apoyo de un supervisor entrenado en reflexión clínica.

Conclusión:

Esta lección clave aumenta el conocimiento científico disponible para los administradores e investigadores en el campo del cuidado de la salud quienes buscan adaptar intervenciones clínicas de salud mental previamente puestas a prueba clínicamente a la implementation en escenarios comunitarios.

Keywords: mentalización, crianza, implementatión, grupos vulnerables de población, salud mental

RÉSUMÉ:

Objectif:

Le processus d’intervention de santé mentale avec des populations vulnerables n’estpas bien décrit dans les recherches. Les auteurs de cet article ont travaille en tant qu’equipe en partenariat avec la communaute afin d’adapter et de lancer un programme d’intervention soutenu de maniéré empirique pour les méres et les petits enfants dans une clinique de santé mentale en consultation externe qui sert avant tout une communauté défavorisée. Méthodes: Nous avons utilisé des méthodes ethnographiques pour document l’adaptation de MIO et l’implémentation pilote d’une clinique communautaire de santé mentale. Dix-sept méres et leurs enfants identifiés de 0–84 mois ont été inscrites dans l’étude.

Résultats:

Les lecons clés de cette mise en œuvre ont inclus: 1. L’importance du travail de formation afin de construire des relations communautaires et d’adapter avec efficacité l’intervention afin de remplir les besoins des thérapeutes et de leurs clients; 2. L’importance qu’il y a de mettre en place des plans de formation et de supervision réfléchie qui s’emboîtent dans le flux de la clinique et peuvent tolérer des perturbations; 3. L’utilisation d’une approche interdisciplinaire est faisable avec le développement d’un plan de communication et le soutien d’un superviseur clinique formé et travaillant sur la réflexion.

Conclusion:

Ces lecons clés avancent les connaissances scientifiques qui sont disponibles aux chercheurs et aux gestionnaires de soins de santé désirant adapter des interventions cliniques de santé mentale testées en essais cliniques pour leur mise en œuvre dans des contextes communautaires.

Keywords: mentalisation, parentage, implémentation, population vulnérable, santé mentale

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG:

Ziel:

Der Prozess der Implementierung von Interventionen im Bereich der psychischen Gesundheit bei gefahrdeten Bevölkerungsgruppen ist in der Literatur nicht gut beschrieben. Die Autoren arbeiteten als Team einer Community, um ein empirisch unterstütztes Interventionsprogramm für Mütter von Sauglingen und Kleinkindern in einer ambulanten psychiatrischen Klinik, die in erster Linie einer einkommensschwachen Gemeinde dient, anzupassen und zu erproben.

Methoden:

Mit qualitativen ethnographischen Methoden dokumentierten wir die Adaption von MIO und die Pilotimplementierung in einer Gemeinschaftsklinik für psychische Gesundheit. Siebzehn Mütter und ihre 0–84 Monate alten Kinder wurden in die Studie aufgenommen.

Ergebnisse:

Die wichtigsten Lektionen aus dieser Implementierung sind: 1. Die Bedeutung der formativen Arbeit für den Aufbau von Gemeinschaftsbeziehungen und die effektive Anpassung der Intervention an die Bedürfnisse der Therapeuten und ihrer Klienten; 2. Die Bedeutung der Gestaltung von Planen für Schulungen und reflektierende Supervision, die in den Ablauf der Klinik passen und Störungen tolerieren können; 3. Mit der Entwicklung eines Kommunikationsplans und der Unterstützung durch einen geschulten, reflektierenden klinischen Supervisor ist die Anwendung eines interdisziplinaren Ansatzes möglich.

Schlussfolgerung:

Diese wichtigen Lektionen fördern das wissenschaftliche Verstandnis von Gesundheitsmanagern und Forschern, die zuvor in klinischen Studien getestete Interventionen im Bereich der psychischen Gesundheit in der Gemeinschaft implementieren wollen.

Keywords: Mentalisierung, Erziehung, Implementierung, gefahrdete Bevölkerung, psychische Gesundheit

![]()

![]()

![]()

Access to mental health services was limited until recently when in 2014, most insurance plans were required to cover mental health services under the Affordable Care Act (2013)—going beyond the federal parity law by mandating mental health services as 1 of the 10 essential health benefits (C.L. Barry & Huskamp, 2011; Frank, Beronio, & Glied, 2014). These recent changes in our healthcare system along with the strategic goals of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (FY 2104–2018) (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2015) have driven the need for evidenced-based mental health interventions that can be implemented into community-based practice. Notably, the science of implementation is distinct from evidence-based research (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005). Scientifically, both evidence-based research and implementation science must include well-designed and carefully evaluated programs, but there is a difference in the intended consumer (Fixsen et al., 2005). While evidence-based interventions provide evidence of how well a program works for consumers in a controlled environment, implementation science involves determining whether the program works when the consumers exist under “real-world” conditions in community clinical settings (Weisz & Jensen, 1999). The design of evidence-based research includes a protocol developed by the researcher, and deviation from the protocol is discouraged and reportable to institutional review boards (Carroll et al., 2007; Fixsen, Blase, Naoom, & Wallace, 2009) whereas implementation science suggests that interventions must be adaptable and modifiable to meet the needs, capacities, and interests of consumers in community settings (Damschroder et al., 2009). Those looking for guidance on implementing mental health programs may find it useful to examine examples of community-engaged implementation research of empirically supported mental health interventions previously tested in clinical trials (Powell, Proctor, & Glass, 2014). We present such an example in this article.

An area that is not well-described in the literature is the process of mental health intervention implementation with vulnerable (low socioeconomic status, racial/ethnic minority, disabled individuals, etc.) clients who also are parenting young children (Napoles, Santoyo-Olsson, & Stewart, 2013). Implementing empirically supported mental health interventions requires a wide range of strategies that address common implementation challenges (e.g., adapting interventions to real-world settings, maintaining treatment integrity, identifying core intervention components) (Powell et al., 2014). The purpose of this article is to describe the adaptation, implementation, and administration of an evidence-based intervention, Mothering from the Inside Out (MIO) in a community mental health clinic (for a description, evaluation, and findings, see Suchman, Ordway, de Las Heras, & McMahon, 2016). Strategies are described for training, planning, and executing a parenting intervention during implementation in a “real-world” community mental health setting. We also describe facilitators and barriers to working with community clients and community clinic staff to inform future implementation projects by interventionists.

THE MIO PROGRAM

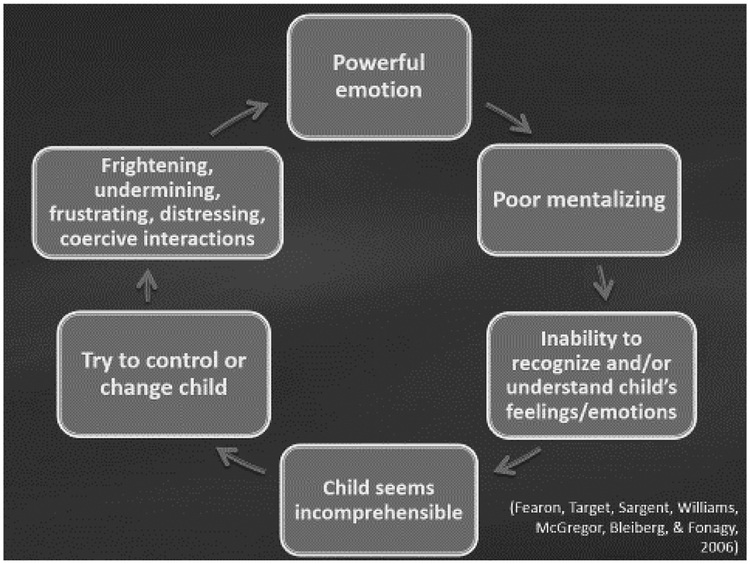

MIO was developed to be delivered by trained therapists engaged in 12 weekly sessions aimed at enhancing parental reflective functioning (RF) among mothers involved in an addiction treatment program. Table 1 lists the core components of the MIO program. The goal of MIO is to help mothers make sense of their children’s and their own emotional experience within the parent–child relationship. A mother’s capacity for RF or mentalizing is reflected in her ability to consider her child’s mind and provides a foundation for the child to develop the ability to fully experience, regulate, and organize a wide range of affect and other mental states (Or-dway, Sadler, Dixon, & Slade, 2014; Slade, 2005). The development of parental RF may be particularly challenging to parents with mental illness. The cyclical pattern of a powerful emotion felt by a mother with a limited capacity for RF (mentalizing) can lead to frightening, undermining, frustrating, distressing, and coercive interactions between mother and child (see Figure 1: Fearon et al., 2006). In two randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of MIO, researchers determined the efficacy of the intervention to improve parental RF, maternal representation quality, and caregiving behavior in a controlled environment (Suchman et al., 2010; Suchman, Decoste, McMahon, Rounsaville, & Mayes, 2011; Suchman et al., 2017). Children responded to their mothers more contingently with clearer emotional cues after the 12-week MIO sessions (Suchman et al., 2011). In this pilot, we were interested in adapting the MIO intervention using a community-engaged approach with the goal of implementing in a real-world community mental health setting. To do so, we devoted 6 months to planning the implementation to ensure that MIO could be adapted to fit the community mental health clinic needs while maintaining core components developed in the RCTs (Table 1). We focused on engaging the stakeholders (community clinic director and clinicians), integrating MIO into the context of the clinic organizational structure, staff capacities and responsibilities, and the larger community setting to determine how these variables may impact the process and outcomes of implementing MIO in a community setting.

TABLE 1.

Core Components of the “Mothering from the Inside Out” Program (adapted from Suchman, DeCoste, Ordway, & Mayes, 2012)

| General | Underlying principles and theoretical concepts of mentalization (Fonagy et al., 2002), attachment, parental reflective functioning (Ordway et al., 2014; Slade, 2005), and mother–infant vulnerabilities among mothers with addictive disorders (Pajulo et al., 2006) |

| Objectives include: support mothers’ developing capacity for emotion regulation; restore the mother’s capacity to engage in human attachment relationships; promote the mother’s capacity to engage with and enjoy her child, tolerate her child’s emotional distress, understand her child’s attachment needs, and support developing regulatory capacities | |

| Focus: helping the mother to enhance her capacity to mentalize or make sense of her own and her child’s underlying mental states affecting behavior, especially during times when the relationship is disrupted | |

| Procedural | Community-based approach to understand the target population, clinical setting (staff buy-in, clinic procedures and services, available resources) |

| Experienced therapists familiar with the target population, trained in mentalization | |

| Intervention Content/Approach | Topic flexibility: The mother can talk about a topic of her choosing. The topics vary widely, and the therapist focuses first on learning about the mother’s perception of the situation. |

| Pacing: Therapists should not overwhelm the mother with too many questions. The pace should be acceptable and comfortable to the mother, and the therapist should first ensure that the mother understands the physical reality of what happened, moving slowly to learning about the emotional reality and how the mother makes sense of it. | |

| Keeping the child in mind: The therapist must continuously keep the child in mind even when the topic the mother is discussing is not directly related to parenting. Conscious effort is made to deciding when to focus on the mind of the mother and when to shift to the mind of the child. | |

| Transparent mentalizing: The therapist makes her own mentalizing mind available to the mother in a marked manner to distinguish the perspective of the therapist and the mother. | |

| Lapses in mentalizing: The therapist actively listens for lapses in mentalizing (nonsequiturs, lapses in coherence, sudden changes in topic, silence, hostility) whether subtle or obvious. | |

| Steps toward mentalizing: The therapist assists the mother in tracking her own thoughts, often through marked mirroring of the mother’s affect. | |

| Monitoring burden: The therapist must be mindful to not expect the mother to mentalize at a higher level than she is capable of. | |

| Supports | Formal training to develop skills of therapists |

| Fidelity ensured through intervention manual and videotaping of sessions that are reviewed by a trained therapist not involved in the intervention | |

| Weekly reflective supervision to regroup with the staff and therapists to discuss cases |

FIGURE 1.

The cyclical pattern of a powerful emotion felt by a mother with limited capacity for mentalization can lead to frightening, undermining, frustrating, distressing, and coercive interactions between mother and child. (Adapted from Fearon, Target, Sargent, Willliams, McGregor, Bleiberg, & Fonagy, 2006). Copyright (c) 2006 John Wiley & Sons Ltd., The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex PO19 8SQ, England.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The theory used to develop MIO originated from Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, and Target (2002), who defined mentalization as the ability to think about and make sense of underlying emotional experiences and how they impact one’s own and another’s behavior. This work was further expanded by Slade (2005) to relate the concept specifically to parenting–parental RF (Ordway et al., 2014). The development of parental RF has been a focus of several intensive programs (Pajulo, Suchman, Kalland, & Mayes, 2006; Reynolds, 2003; Sadler et al., 2013; Schechter et al., 2006; Slade, 2006; Suchman et al., 2011) and is thought to be applicable in primary pediatric healthcare settings (Ordway, Webb, Sadler, & Slade, 2015) to support parent–child relationships.

Millions of parents in the United States are parenting while struggling with psychiatric difficulties that render them vulnerable to maladaptive parenting when they become dysregulated and potentially lead to poor-quality parent–child relationships (van der Ende, van Busschbach, Nicholson, Korevaar, & van Weeghel, 2016). While these parents experience the same challenges as do parents without mental illness, the nature of their illness makes them susceptible to discrimination and stigma, secondary problems resulting from their psychological symptoms, limited parenting skills, and/or lack of community and social support (Sands, 1995). Unfortunately, mental health services focused on parenting are scarce (Farmer, 2017). In child-guidance centers, children may receive direct services, but parents are often ancillary to this process, and most existing programs do not focus on the emotional quality of the parent–child relationship—an important predictor of children’s psychological development (Grienenberger, Kelly, & Slade, 2005; Slade, 2002; Suchman, Mayes, Conti, Slade, & Roun-saville, 2004). Important positive outcomes have been reported in parenting programs that address mental health issues through home visiting (Grant, Ernst, Streissguth, & Stark, 2005; Heinicke et al., 1999; Sadler et al., 2013), but a group of community mental health clinic therapists identified a need for a better therapeutic approach that could be incorporated in their clinic work with clients who were parents in a system that silos the treatment of adults and children. The clinic staff and administration approached the principal investigator of MIO for assistance. The resulting community-engaged pilot implementation of MIO is the focus of this article.

CONSOLIDATED FRAMEWORK FOR IMPLEMENTATION RESEARCH

This pilot implementation study was guided by Damschroder et al.’s (2009) Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). The CFIR was developed through the synthesis of common constructs from published implementation theories, models, and frameworks to provide a systematic approach to assess potential barriers and facilitators in implementing evidence-based programs into a community-based setting. The CFIR framework has been helpful in capturing the complexities of implementation across diverse settings (Ilott, Gerrish, Booth, & Field, 2013), including community mental health centers (Weeks et al., 2015). The CFIR consists of 39 constructs divided into five domains: (a) intervention characteristics (e.g., characteristics of MIO that will influence implementation), (b) outer setting (e.g., patient needs and resources), (c) inner setting (compatibility of MIO with therapists’ background, leadership engagement), (d) characteristics of individuals (e.g., knowledge and attitudes), and (e) process (e.g., quality and extent of planning and engagement with stakeholders and clinic clients) (Damschroder et al., 2009). The domains interact in an organizational framework to synthesize and build information about the “who, what, where, and with whom” influence implementation and implementation effectiveness (see Table 2) (Kirk et al., 2015). While the CFIR provides a list of explicitly defined constructs, it is not intended to be applied wholly to every problem (Damschroder et al., 2009). The CFIR can be used preor postimplementation to guide exploration into the question of what factors may (prospectively) or did (retrospectively) influence implementation and how implementation influenced performance of the intervention (Damschroder et al., 2009). The CFIR developers have a Web site to offer technical assistance and provide tools and templates for design of implementation and evaluation studies (http://www.cfirguide.org/). In this article, we used the CFIR to describe the experience of implementing MIO to meet the needs of a mental health community clinic serving a socioeconomically disadvantaged population of mothers. We present a narrative analysis of the facilitators and barriers to implementing a complex mental health intervention to advance the scientific knowledge available to healthcare managers and researchers who are looking to adapt mental health interventions tested as RCTs for application in a community setting.

TABLE 2.

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) Constructs Addressed in This Study

| Domain and Associated Constructs | Addressed in Current Study | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. INTERVENTION CHARACTERISTICS | ||

| a. Intervention Source | University-based RCT program with 9 years of data | |

| b. Evidence Strength & Quality | RCT findings from MIO program with substance-using mothers provided strong evidence for adapting the program to a mental health clinic. | |

| c. Relative Advantage | Community stakeholders viewed the MIO program as potentially addressing the need to find good therapeutic approaches whenworking with parents. | |

| d. Adaptability | Community-engaged approach that incorporated an interdisciplinary team of stakeholders helped to determine what would require adaptation and how to best maintain fidelity and achieve success in the community setting. | |

| e. Trialability | MIO was not set up to replace any current therapy approaches in the clinic but rather to provide an alternative. It remained possible to terminate the program without disruption to the community clinic. | |

| f. Complexity | Mentalization was a new, but complimentary, therapeutic approach that required intensive training pre-intervention followed by weekly booster sessions with reflective supervision. | |

| g. Design Quality and Packaging | Reflective supervision to include reflection, collaboration, and regularity | |

| Cost | Not an issue | |

| 2. OUTER SETTING | ||

| a. Client Needs and Resources | Desire to become better parents, but struggled with limited resources (childcare, transportation, etc.) and knowledge about how to relate to their children and/or families | |

| b. Cosmopolitanism | Clinic staff were supported, “external boundary-spanning roles of their staff.” | |

| c. Peer Pressure | Not an issue | |

| d. External Policy and Incentives | Not an issue | |

| 3. INNER SETTING | ||

| a. Structural Characteristics | A mix of University-employed and State-employed therapists as well as psychology interns. Three teams of therapists—adult, young adult, and child—invited to participate in the program as therapists to be trained or as recruiters of clients to participate in the program. Regular staff meetings ensured coordination among groups to support a holistic product of service. | |

| b. Networks and Communication | Relationships maintained among all stakeholders through regular presence of researchers at the clinic, including attendance at weekly meetings, hallway conversations, and reflective supervision | |

| c. Culture | Not an issue | |

| d. Implementation Climate | Strong | |

| e. Tension for Change | Therapists were looking for ways to support their clients who were parents. | |

| f. Compatibility | Mentalization theory fit well within the clinic goals related to assisting clients who are parents to identify triggers and regulate their emotions when triggered. | |

| g. Relative priority | Flexibility provided with respect to the number of clients assigned to a therapist to not to overburden | |

| h. Organizational Incentives and Rewards | Psychology interns are required to participate in a research project, and MIO offers them the opportunity to become involved in research and learn a new therapeutic approach to working with families. | |

| i. Goals and Feedback | Group and individual reflective supervision provided weekly to all therapists involved | |

| j. Learning Climate | Not all therapists are University-employed; however, the presence of the university and culture of the clinic fosters a healthy learning environment. | |

| Readiness for Implementation | ||

| a. Leadership Engagement | Strong leadership involvement between the clinic director (T.M.) and principal investigator (N.S.) | |

| b. Available Resources | Grant funding (N.S. as the PI) to cover all research costs. Grant funding and clinic funds provided physical resources. Clinic agreed to relieve therapists’ time to allow them to take on an additional client. | |

| c. Access to Knowledge and Information | Schedules coordinated with therapists and researchers and dedicated progress notes developed to protect clients under Certificate of Confidentiality | |

| 4. CHARACTERISTICS OF INDIVIDUALS | ||

| a. Knowledge and Belief About the Intervention | Therapists previously exposed to mentalizing approaches through conference attendance | |

| b. Self-Efficacy | Not addressed | |

| c. Individual Stage of Change | Participation was voluntary at this pilot stage; therefore, self-selection into training in MIO signified intent to change. | |

| d. Individual Identification With Organization | Mix of University employees and State employees required careful consideration to potential incentive for buy-in to a University-based intervention. | |

| e. Other Personal Attributes | Not an issue | |

| 5. PROCESS | ||

| a. Planning | One year spent considering the adaptable aspects of the intervention and building relationships with stakeholders | |

| b. Engaging | Community-engaged approach to implementation led by opinion leaders, internal leaders, champions, and external change agents | |

| c. Opinion Leaders | Clinic directors and peer therapists promoted the MIO intervention. | |

| d. Formally Appointed Internal Implementation Leaders | Clinic director is a co-investigator on the project. | |

| e. Champions | Co-Investigator (M.O.) committed to implementation as her primary work for 2 years. | |

| f. External Change Agents | Well-respected principal investigator (N.S.) as well as Co-Investigator focused on implementation. | |

| g. Executing | Fidelity monitored through weekly review of videotaped sessions; quality of execution reviewed during weekly group reflective supervision meetings | |

| h. Reflecting and Evaluating | Use of reflective supervision to support professional development and intervention fidelity; CFIR constructs used in evaluation | |

RCT = randomized clinical trial; MIO = Mothering from the Inside Out program.

METHOD

We used qualitative ethnographic methods to document the adaption of MIO and the pilot implementation in a community mental health clinic.

Setting

The setting was an urban community mental health clinic serving children and parents, located adjacent to a small Northeastern city where many clients are exposed to urban problems (e.g., crime, poverty, minimal affordable housing) typically identified with larger cities.

Sample

Upon university and clinic Institutional Review Board approval, 12 therapists from the clinic (one nurse practitioner, two social workers, one licensed psychologist, six predoctoral psychology interns, and two postdoctoral psychology fellows) served as community partners and volunteered for training in the MIO program. Seventeen mothers and their identified 0- to 84-month-old children were enrolled in the study to receive the MIO intervention. All mothers provided written consent and parental permission to participate in the intervention. Participation was voluntary and did not impact their services at the clinic or other services provided to them.

Data Collection

Over the course of 2 years, the primary investigators (M.O. and N.S.), research staff (L.D.), clinic director (T.M.), and clinic therapists met weekly to discuss the implementation process using the CFIR framework and to review individual cases presented by the clinic therapists. Over the course of 2 years, all meetings with the clinic staff and administrators were observed and documented. This included meetings to adapt the MIO intervention, conduct staff training, and review DVD-recorded MIO sessions conducted by therapists with their clients. Next, we provide a narrative derived from our reflections on these weekly meetings and evaluation of the implementation process to determine which constructs of the CFIR influenced implementation of MIO and how implementation affected the performance of MIO. The authors of CFIR acknowledge that focusing on all 39 constructs can mire evaluations; therefore, they propose strategically evaluating each construct within the context of the study evaluation to determine which constructs are most helpful in the implementation process (Damschroder et al., 2009). Hence, this is the approach we took during the planning and implementation phases.

Knowledge translation can be accelerated when small studies target discrete, but significant, questions (Baker, Gustafson, & Shah, 2014). With this in mind, extensive notes were taken by the lead author throughout the implementation process and were guided by the following discrete questions:

What were the essential activities (e.g., training, planning, executing, reflecting) of the MIO intervention necessary for successful implementation?

What intervention characteristics from MIO could be translated to a community-based program?

What were the facilitators and barriers in the outer setting (e.g., client needs and resources) considered during the planning phase and encountered during the pilot phase of the program?

What were the facilitators and barriers in the inner setting (e.g., culture, leadership engagement) considered during the planning phase and encountered during the pilot phase of the program?

Exploration of these questions allowed us to identify the constructs that were most important to implementation of MIO into a community mental health clinic. Table 2 describes the authors’ assessment of which CFIR constructs were most useful to the implementation process of MIO into a community setting. Confirmation of the narrative presented in this article was received by the stakeholders, and their editorial comments were largely incorporated into the final article.

RESULTS

Essential Activities of the MIO Intervention for Successful Implementation

Planning.

The collaboration between the researchers and therapists during the planning phase offered an opportunity to identify potential facilitators and barriers within the inner and outer settings of the clinic. The planning began with a review of the core components of the MIO program during the community engagement of the clinic stakeholders (Table 1). Our detailed review of the MIO core components indicated that they were viewed as acceptable to the community stakeholders and that no substantive procedural changes were needed to adapt MIO in the community setting. However, there were several important considerations identified as potential barriers by the stakeholders during the planning meetings, including childcare, attendance inconsistency, and interpersonal/cultural within-group differences in parenting. We utilized a patient-centered approach, defined as involving patients in their care while viewing their social and cultural background, listening to them, and seeing them as informed and respecting (Epstein & Street, 2011), to address these concerns. The patient-centered approach is known to improve outcomes within healthcare settings (C.A. Barry, Stevenson, Britten, Barber, & Bradley, 2001) and allowed us to address potential barriers.

Preliminary meetings among the researchers and clinic director was the first step in ensuring buy-in from the clinic. During this planning stage, we identified the logistical needs of the program and potential areas where resources could be pooled. For example, we recycled existing audiovisual equipment available at the clinic that was supplemented with equipment provided by the research funding to set up the DVD recordings of the MIO sessions. Each therapy session was videotaped to measure fidelity and assist the principal investigator of MIO and another psychologist colleague in providing reflective supervision of the therapists.

Once we had buy-in from the clinic director, we worked with a self-selected team of therapists and altogether discussed MIO recruitment protocols and client eligibility criteria. Specifically, the therapists volunteered to increase their existing caseload by one to two clients to participate in the pilot implementation project. The therapists felt that it was important not to interrupt their care for their existing clients, so clients recruited in the implementation pilot of MIO would be seen during the therapists’ “off” hours. The research team assured the therapists that reversing the implementation was possible at any time—termed trialability in the CFIR. The therapists expressed their interest in training in mentalization as a strong motivator for increasing their caseloads. They expressed concern that our current mental health system does not adequately support clients who also are parents or provide adequate behavioral approaches to meet the needs of more severely disturbed parents.

Per the request of the clinic administration, clients would be referred by the clinic therapists to the MIO research staff, who would then assess for eligibility (parent over the age of 18 with legal custody of their child between 0–84 months). The director invited the senior author to attend staff meetings to introduce the project and provide recruitment materials. Referrals were accepted from any therapist at the clinic regardless of whether the referring therapist participated in the MIO program. We set up a protocol to receive the referrals, arrange a time to consent the client for the research, and introduce the client to one of the trained MIO therapists at the clinic.

Training.

During the stakeholder engagement process, the therapists became familiar with the facts, truths, and principles related to MIO, as suggested by the CFIR framework (Damschroder et al., 2009). Feedback from the therapists during the initial planning suggested the need for more opportunities to understand how mentalization theory and practice connect. The development of five weekly, formal group-training sessions provided the therapists with the opportunity to become increasingly comfortable with the intervention and apply the principles of the intervention within the context of their practice. The training program was supplemented with training demonstrations (e.g., videotapes of therapists conducting the MIO RCT intervention) and experiential exercises (e.g., modeling and role playing) that allowed for hands-on, practical experience and insure fidelity. Upon confirmation that the therapists were comfortable with the basics in mentalization theory and approach at the end of the 5 weeks, we began to enroll clients. The therapists came from complimentary, but different, educational backgrounds: social work, nurse practitioner, psychologists, and psychology interns. They had varying levels of knowledge of mentalizing theory and mentalization therapeutic techniques. A few of the therapists had some prior training in mentalization at various workshops and a 5-day training course provided by visiting experts at a local university. All therapists and researchers continued to meet weekly for ongoing training and group clinical reflective supervision. Some therapists preferred the weekly group supervision while others requested additional individual supervision. The group meeting time also was used to garner feedback on the implementation process. Individual supervision reinforced the learning of new techniques with individual cases. Training is commonly thought to be the most challenging aspect of implementation due to the intense amount of time required on the part of the trainer and trainee (Sullivan, Blevins, & Kauth, 2008). Our experience supported this thought: Committing to ongoing training was perhaps the most challenging aspect of MIO.

MIO training involves teaching therapists to facilitate parents’ capacity to make sense of and regulate their own emotions and behaviors so that they also can support their young children’s emerging emotion regulatory capacities. Specifically, therapists learn to engage parents in the process of making sense of their own affective experiences during stressful interactions with their children. Concomitantly, therapists were trained to help mothers engage in a process of understanding their child’s behavior as being driven by affective experience (for more information about therapeutic approach and techniques, see Suchman, DeCoste, Ordway, & Mayes, 2012). Therapists were experienced in building a therapeutic alliance with their clients and were further trained by the PI to serve as role models for parental RF, maintaining transparency in relation to their own thought process so that their clients (i.e., mothers) could see RF in action. Therapists also learned to maintain a therapeutic stance that is reflective and emphasizes curiosity and inquisitiveness about the mother’s own emotional experiences rather than adopting a stance of all-knowing expertise and the prescription of parenting strategies (Ordway et al., 2014). These techniques were readily adopted by the interdisciplinary team of therapists.

Executing.

Execution of the MIO intervention in this pilot study required full integration into the physical clinic setting. The first step was to identify therapists interested in implementing MIO into their current practice. Careful consideration was given to the differences in setting between the MIO conducted as an RCT and the community setting. Unlike the therapists involved in the MIO RCTs within a controlled clinical setting, the therapists at the community mental health clinic worked in a setting often challenged by emergency situations and conflicting demands. It was important to the researchers and the therapists that we implement the intervention on a small scale to allow the clinic and therapists time to build experience and expertise, and reflect on the intervention over time. We determined that testing the intervention on a small scale allowed time for therapists to become well-trained and comfortable with the mentalization approach and for enhanced communication between all involved.

Reflection and evaluation.

Evaluation and assessment of fidelity are important to the MIO program. During the planning stage, the researchers and clinic staff agreed that evaluation of the outcomes on parenting would be important to determine the usefulness of the program in addressing their need for enhanced therapeutic approaches with adult clients who also were parents. Prior to the start of a therapy session, a baseline research visit involved a mother’s consent to participate in the research, a videotaped semistructured interview to measure parental RF, a play session between the mother and her child, and completion of a series of self-report psychosocial adjustment questionnaires. These measures were repeated after 12 weeks of 1-hr MIO sessions with her therapist. Outcome results are published elsewhere (Suchman et al., 2016). The principal investigator of MIO reviewed each therapy session and provided weekly group reflective supervision as well as individual written constructive feedback to the therapists to insure the fidelity of the intervention (i.e., the counselors delivered the intervention as intended). A random sample of sessions also was sent to an external reviewer trained in MIO fidelity measurement.

Characteristics From the Original MIO Translated to the Community-Based Program

An important element of implementation research is discerning intervention characteristics to retain versus those which can be expended because they are not a good fit within the community setting. We found that the mentalization construct was critical to retain because it was highly relevant to the client population. Mentalization is believed to enhance mothers’ ability to parent in a regulated and regulating manner (Slade, 2005). Struggling with regulation of thoughts and emotions is at the core of mental illness, and mentalization is one effective way to accomplish and strengthen this ability (Fonagy et al., 2002). The ability to mentalize provides one with a feeling of self-agency; therefore, mentalization-based therapy is well-suited to help parents regulate their behavior (for a review, see Suchman et al., 2016). The therapists and researchers felt that mentalization theory would complement the therapists’ current approaches in their work with families involved in mental health services.

Facilitators and Barriers in the Outer Setting Considered During the Planning Phase and Encountered During Implementation

Stakeholders valued the potential for improving parental RF and reducing maternal psychiatric symptoms among their clients who also were parents; however, the therapists and researchers expressed concern about the vulnerability of the clients due to their mental health diagnosis and risk for multiple health disparities (e.g., low socioeconomic status, limited education, minority status). We determined that within the outer setting, transportation, childcare needs, and poor social support were the most significant barriers. The clinic had a service contract with a local agency to provide transportation to the clinic’s clients, therefore minimizing this barrier. Therapists had the option of requesting this service for their clients, including those enrolled in the MIO intervention, to improve attendance. A schedule was posted, and the therapist could make a request 24 hr ahead of time to arrange for the client to be picked up, if needed. The clinic also was near a city bus stop and had protocols for encouraging and teaching clients to use the bus system. Second, childcare posed a potential barrier if the target child was not school-age or if the client was not available during school hours. Because the MIO program was a pilot study that had research funds available, there were two research assistants, trained in caring for children, who were available to provide childcare in the clinic while the child’s parent was engaged with the therapist. Child-appropriate toys and crafts were purchased with the research funds and available for working with the children.

While the barriers of transportation and childcare were successfully addressed as described earlier, the clients’ persistent limited social support remained a concern. Many of the parents involved in the program were single parents struggling to balance work, limited income, therapy, and caring for their children. All clients were living in urban poverty. The challenging social experience of many of the families meant that the parents often brought significant issues requiring more concrete assistance (e.g., the threat of losing their child to the care of the child welfare system), thereby challenging the therapists to balance assisting them with their immediate concrete needs and exploring the mother and child’s mental states. When the therapists felt that outside barriers interfered with their goals planned for MIO, the reflective supervision provided by the PI helped the therapists in working through their concerns. They were encouraged to meet their clients where they were emotionally when faced with concrete needs and to use a reflective stance as they assisted their clients with obtaining their immediate goals and needs. For example, when a client was struggling with an emergent housing need, the therapist was encouraged to provide the necessary support while maintaining a reflective stance:

I imagine the fact that your sister has asked you to move out is very upsetting to you and I wonder how your daughter will experience the transition out of her aunt’s home. Let’s focus today on finding you a place to live and then I would like to talk more about how this experience has affected you and your daughter.

In this way, the therapist maintained a reflective stance, facilitated concrete assistance, and encouraged the mother to remain curious about her child’s mental states.

Facilitators and Barriers in the Inner Setting Considered During the Planning Phase and Encountered During Implementation

We experienced both barriers and facilitators within the inner setting, such as structural characteristics (e.g., clinic procedures and protocols), communication, and a strong implementation climate. With respect to structural characteristics, the clinic’s overall organization and established three main divisions—child, young adult, and adult—were facilitators to the implementation process. The buy-in and leadership from the clinic director was strong and facilitated implementation. The clinic director attended all three division meetings at the clinic and could address any concerns that therapists had regarding the program, whether they were or were not involved in the program. The clinic teams were very stable, with very little turnover other than the interns who rotated through every 1 to 2 years. The clinic director also provided researchers with regular opportunities to attend staff meetings to describe the inclusion and exclusion criteria and promote the implementation of MIO.

The primary barrier within the domain of structural characteristics was the large caseload carried by the therapists. The mental health clinic had a long wait-list, and it was important to collaborate with the clinic staff and administration about how to manage the wait-list with respect to adding additional cases to the already full caseload of the therapists. In addition, many of the therapists had competing demands, such as outside supervision, scheduling conflicts with the variety of committees in which the therapists were engaged, and unexpected emergent needs of clients. While these factors were barriers within the inner setting, the commitment to the MIO program and the desire to improve the outcomes of adult clients who were struggling with parenting and mental illness were strong facilitators. The therapists remained engaged for a minimum of 1 year, at which time they expressed comfort with the MIO program and withdrew from the research portion of the implementation pilot, but reported that they continued to incorporate a mentalization approach with their clients.

Space and scheduling were additional barriers. The clinic administration provided a physical space to conduct the research, including a dedicated locked office space that was fitted with a remote camera wired to an adjacent conference room for recording the MIO sessions to analyze fidelity. We set up the office space to be a warm environment to conduct the therapy sessions. A secure storage space within the conference room was provided to store the recording equipment and research materials. Because the clinic was a satellite program within a large community mental health center, we utilized research-specific forms for clinic staff to create unique progress notes and indicate that the MIO therapy sessions were part of a research protocol protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality. While we had a designated therapy room, the conference room (the video control center) had a 90% utilization rate that made scheduling the videotaping challenging. The researchers remained flexible when adjustments to the schedule were needed.

Communication within the inner setting occurred at many levels. One important facilitator was the formation of a relationship with the clinic receptionists. Because the MIO intervention was not part of the mainstream schedule of the clinic during the pilot phase, the receptionists requested that they should be made aware of clients who would be arriving and were not on the clinic schedule. Communication was enhanced by the routine presence of research assistants throughout the study, who would take the opportunity to speak with participating and nonparticipating therapists at the clinic to form a bond, answer questions, and participate in various celebrations at the clinic.

Fortunately, the culture of the inner setting fostered healthy communication between all clinic therapists through weekly team meetings. We recognized that when family-based mental health services are provided, many system providers are likely to be involved both individually and collectively, resulting in complex, reciprocal relationships (Ungar, Liebenberg, Landry, & Ikeda, 2012). An example of this complexity was the fact that some clients were involved with multiple providers within the clinic setting due to their engagement with group and/or individual therapy, psychiatric consultation, vocational services, and case-management services. The researchers made a purposeful effort to regularly touch base with the therapists who were running the group therapy (and were not part of the MIO implementation pilot) to address any concerns or possible conflicts occurring with the client who was in the MIO program and also attending group therapy. To our knowledge, there was no resistance to the implementation pilot by staff who were not involved in the program at the clinic.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of MIO into a community setting provided some key lessons for the implementation of evidenced-based interventions in community mental health settings: (a) the importance of formative work to build community relationships and effectively adapt the intervention to meet the needs of the community mental health therapists and their clients, (b) the importance of designing a training plan and conducting reflective supervision that fits within the flow of the clinic and adjusts to the potential disruptions in care that working in the community can bring, and (c) that working with multiple therapists using an interdisciplinary approach is feasible with the development of a plan for communication and the support of a trained reflective clinical supervisor. The results of the intervention have been published separately (Suchman et al., 2016), indicating that this pilot appeared to be successful based on the commitment of the therapists and the desire for additional sessions by the therapists and clients.

The formative work during the planning stages to build community relationships and establish buy-in allowed for effective adaption of the intervention to meet the needs of the therapists and their clients. Implementation of an evidence-based intervention such as MIO into a community setting poses many challenges commonly addressed in the emerging field of implementation science. For example, it is critical to understand the culture and circumstances of families and communities when providing mental health services to families of young children. Families from diverse backgrounds often deal with multiple and comorbid conditions that may complicate the process of implementation of evidence-based programs developed in controlled environments.

We spent 6 months thinking through the characteristics of the intervention and a process of execution of the MIO intervention at a community mental health clinic. From the start, the activities involved in implementing the MIO intervention were discussed as a team, involving the participating community therapists and clinic director (stakeholders) as well as the researchers. Subsequently, implementation decisions were made with the stakeholders’ input. For example, the planning stage for the individual MIO program began with regular meetings between the researchers and clinic director to identify therapists who were interested in training in the MIO intervention. Once identified, the community therapists, clinic director, and researchers met regularly to plan the implementation.

The main success of this pilot implementation was our ability to establish a collaborative working relationship with a community clinical team to implement a complex research protocol. Adapting interventions to fit the setting and insure buy-in from the community stakeholders are critical aspects of implementation and require careful planning, executing, and reflecting on the intervention (Damschroder et al., 2009). We believe it would be difficult to achieve the success that we experienced without first establishing a strong rapport and buy-in from the clinic director. The time commitment to establish these relationships should not be underestimated in value. The clinic (inner) setting provided the administrative and staffing structure, ongoing supports, and cultural climate that were critical to the buy-in from all stakeholders and establishment of a balance between adjustments to the intervention and the fidelity of the MIO program. Without a good fit, the community stakeholders at the mental health clinic may have resisted implementation or acceptance of the MIO intervention.

Designing a plan for training and reflective supervision that fits within the flow of the clinic and adjusts to the potential disruptions in care that working in the community can bring is important to think about a priori. The primary focus of this pilot intervention implementation was to ensure that adequate training could be provided within the context of the community setting and integrated within the other therapeutic approaches available at the clinic (CBT, DBT, group work). The training also involved reflective supervision. The purpose for using reflective supervision in the MIO program was twofold: to increase fidelity to the program and provide professional development to the therapists involved. Reflective supervision allows the therapists to develop a better understanding of their relationships within the MIO group, their work with their clients, and how to multidimensionally view these relationships. The three critical aspects of reflective supervision are reflection, collaboration, and regularity. Reflection requires a trained facilitator in the process and interactions. This implementation involved an interdisciplinary team of researchers, psychologists, nurses, and social workers, and the development of effective collaboration and communication was achieved through the careful 1-year planning process and ongoing outreach. Last, we determined a schedule of weekly meetings that provided regularity. If a therapist was unable to meet on a particular week, the research staff met with the therapist during the week before or after the meeting to communicate any concerns. In addition to the group supervision, the PI reviewed all videotaped sessions and provided extensive written feedback to the therapists, which was e-mailed directly to the therapist and copied to the lead author to coordinate fidelity assessments. The flexibility in providing reflective supervision individually, in a group, in person, and via e-mail allowed us to develop trusting interdisciplinary relationships and foster a team environment by meeting the needs of the therapists. This approach is unique, as most implementation programs do not offer a choice of supervision approaches and are limited to group or telephone supervision. There also were opportunities for reflective supervision that combined self-report, observation (through videotaped sessions), and self-reflective practices which are noted to enhance clinical competencies (Gonsalvez & Crowe, 2014).

Working with multiple therapists using an interdisciplinary approach is feasible with the development of a plan for communication and the support of a trained reflective clinical supervisor. Strong communication and reflective supervision provided insight into the balance of fit and fidelity in this ethnographic case observation of the adaptation and pilot implementation of MIO. The complexity of the inner and outer settings of the clinic and the MIO intervention posed many challenges. Hence, ethnographic study of this MIO pilot provided an opportunity to obtain realtime evaluative feedback through regular communication and ongoing reflective supervision. We documented challenges to the implementation by using the CFIR. Upon review of this documentation and community-engaged approach to collaboration, the findings from this pilot may be generalizable to future MIO implementation.

Limitations

There are several limitations within this implementation project. This MIO intervention was adapted for one community mental health clinic with a University connection that works with an underserved population and may not be suitable for types of mental health clinics serving a different population. This pilot implementation was intended to test the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention in a community setting. While there are some important results from the data collected in this study (see Suchman et al., 2016), the sample size is too small to draw definitive conclusions or to determine any statistically significant associations. Despite the limitations, this study has considerable strengths, including its foundation in psychological theory, mentalization, the use of the CFIR framework to evaluate the process, and the use of a community-engaged approach wherein community stakeholders and researchers informed the study. Finally, one important consideration in implementing MIO was that a mental health clinic is more likely to have an inner setting that is more conducive to the application of the model. Much more work would be necessary to consider application of this program into a setting with therapists with less experience in therapeutic interventions, such as in a primary care setting.

Future Directions

Our ongoing work in implementing MIO in community mental health settings will continue to focus on training. Another focus of our work will be to consider the heterogeneity of the client’s reasons for engaging with the clinic and their goals in therapy. Training of the interns and other therapists should emphasize their skills and engage them in conversations regarding the client’s reasons and goals for therapy and how the MIO program can assist the therapeutic alliance with the client and the client’s outcomes in relation to parenting. In addition, data should be disaggregated to examine potential differences based on the client’s mental health disorder and whether the child or the parent is the client. An RCT will be considered to conduct a comparative effectiveness study comparing MIO and routine mental health approaches at the clinic to determine whether similar findings in the two RCTs on substance-using mothers may be found when MIO is used in a community mental health clinic. Future studies also will include formally interviewing clients to assess their satisfaction with the program and the development of a community advisory board.

Conclusion

The clinical significance of adapting this program for use in a community setting is related to the increased efforts by clinical researchers to identify buffering mechanisms to the relationship between toxic stress experienced during early childhood with adverse lifelong health effects (Shonkoff et al., 2012). As mental illness and low socioeconomic status are considered chronic stressors for children, the implementation of mentalization-based programs focused on parenting in community mental health clinics as described in this article has potential for buffering toxic stress. The next steps are to train nurses and other health providers in the clinical approach.

Footnotes

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest. The investigators acknowledge the National Institute on Drug Abuse for its ongoing funding for this research, including R01 DA17294 (Suchman, PI) and K02 DA023504 (Suchman, PI) as well as funding provided by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (PI: Nancy Reynolds), 5T32NR008346–06 to the first author during her postdoctoral fellowship. We also thank our Research Assistants Rachel Terino and Heather Sarnataro for their many important contributions to this work. We are grateful for the input we received from clinical consultant Susan Bers. Finally, this study was done at the Connecticut Mental Health Center, a joint venture between the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services and the Yale University School of Medicine, and we thank the clients and clinicians at the West Haven Mental Health Clinic; without their participation and support, this work would not have been possible.

REFERENCES

- Baker TB, Gustafson DH, & Shah D (2014). How can research keep up with eHealth? Ten strategies for increasing the timeliness and usefulness of eHealth research. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 16(2), e36 10.2196/jmir.2925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CA, Stevenson FA, Britten N, Barber N, & Bradley CP (2001). Giving voice to the lifeworld. More humane, more effective medical care? A qualitative study of doctor–patient communication in general practice. Social Science & Medicine, 53, 487–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, & Huskamp HA (2011). Moving beyond parity—Mental health and addiction care under the ACA. New England Journal of Medicine, 365, 973–975. 10.1056/NEJMp1108649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, & Balain S (2007). A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implementation Science, 2(1), art. no. 40. 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, & Lowery JC (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), art. no. 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein RM, & Street RL (2011). The values and value of patient-centered care. Annals of Family Medicine, 9, 100–103. 10.1370/afm.1239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer A (2009). When parents need treatment: Supports scarce for mothers with mental illness. Child Welfare Watch. Retrieved March 22, 2017, from http://www.centernyc.org/child-welfare-nyc/2009/03/when-parents-need-treatment-supports-scarce-for-mothers-with-mental-illness

- Fearon P, Target M, Sargent J, Williams LL, McGregor J, Bleiberg E, & Fonagy P (2006). Short-term mentalization and relational therapy (SMART): An integrative family therapy for children and adolescents In Allen JG & Fonagy P (Eds.), Handbook of mentalization-based treatment (pp. 201–222). West Sussex, England: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Blase KA, Naoom SF, & Wallace F (2009). Core implementation components. Research on Social Work Practice, 19, 531–540. 10.1177/1049731509335549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, & Wallace F (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Tampa: University of South Florida, Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Gergely G, Jurist EL, & Target M (2002). Affect regulation, mentalization, and the development of the self. New York: Other Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frank RG, Beronio K, & Glied SA (2014). Behavioral health parity and the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Social Work in Disability & Rehabilitation, 13, 31–43. 10.1080/1536710X.2013.870512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalvez CJ, & Crowe TP (2014). Evaluation of psychology practitioner competence in clinical supervision. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 68, 177–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant TM, Ernst CC, Streissguth A, & Stark K (2005). Preventing alcohol and drug exposed births in Washington State: Intervention findings from three parent-child assistance program sites. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 31, 471–490. 10.1081/ADA-200056813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grienenberger J, Kelly K, & Slade A (2005). Maternal reflective functioning, mother-infant affective communication, and infant attachment: Exploring the link between mental states and observed caregiving behavior in the intergenerational transmission of attachment. Attachment & Human Development, 7, 299–311. 10.1080/14616730500245963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinicke CM, Fineman NR, Ruth G, Recchia SL, Guthrie D, & Rodning C (1999). Relationship-based intervention with at-risk mothers: Outcome in the first year of life. Infant Mental Health Journal, 20, 349–374. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199924)20:43.0.CO;2-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ilott I, Gerrish K, Booth A, & Field B (2013). Testing the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research on health care innovations from South Yorkshire. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 19,915–924. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2012.01876.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk MA, Kelley C, Yankey N, Birken SA, Abadie B, & Damschroder L (2015). A systematic review of the use of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. Implementation Science, 11(1), art. no. 72. 10.1186/s13012-016-0437-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nápoles AM, Santoyo-Olsson J, & Stewart AL (2013). Methods for translating evidence-based behavioral interventions for health-disparity communities. Preventing Chronic Disease, 10, 130–133. 10.5888/pcd10.130133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway M, Webb D, Sadler LS, & Slade A (2015). Parental reflective functioning: An approach to enhancing parent-child relationships in pediatric primary care. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 29,325–334. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordway MR, Sadler LS, Dixon J, & Slade A (2014). Parental reflective functioning: Analysis and promotion of the concept for paediatric nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23, 3490–3500. 10.1111/jocn.12600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajulo M, Suchman N, Kalland M, & Mayes L (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of residential treatment for substance abusing pregnant and parenting women: Focus on maternal reflective functioning and mother-child relationship. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27, 448465 10.1002/imhj.20100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2012, 78 Fed. Reg. 15410 (March 11, 2013) (to be codified at 45 C.F.R. pts. 153, 155,156, 157, & 158).

- Powell BJ, Proctor EK, & Glass JE (2014). A systematic review of strategies for implementing empirically supported mental health interventions. Research on Social Work Practice, 24, 192212 10.1177/1049731513505778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds D (2003). Mindful parenting: A group approach to enhancing reflective capacity in parents and infants. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 29, 357–374. 10.1080/00754170310001625413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sadler LS, Slade A, Close N, Webb DL, Simpson T, Fennie K, & Mayes LC (2013). Minding the Baby: Enhancing reflectiveness to improve early health and relationship outcomes in an interdisciplinary home-visiting program. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34, 391–405. 10.1002/imhj.21406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sands RG (1995). The parenting experience of low-income single women with serious mental disorders. Families in Society, 76, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Schechter DS, Myers MM, Brunelli SA, Coates SW, Zeanah CH Jr., Davies M et al. (2006). Traumatized mothers can change their minds about their toddlers: Understanding how a novel use of videofeedback supports positive change of maternal attributions. Infant Mental Health Journal, 27, 429–447. 10.1002/imhj.20101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Siegel BS, Dobbins MI, Earls MF, McGuinn L et al. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, e232–e246. 10.1542/peds.2011-2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A (2002). Keeping the baby in mind: A critical factor in perinatal mental health In Slade A, Mayes L, & Epperson N (Eds.), Special Issue on Perinatal Mental Health (Jun-Jul, pp. 10–16). Washington, DC: ZERO TO THREE. [Google Scholar]

- Slade A (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, 7, 269–281. 10.1080/14616730500245906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A (2006). Reflective parenting programs: Theory and development. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 26, 640–657. 10.1080/07351690701310698 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suchman N, DeCoste C, Ordway MR, & Mayes L (2012). Mothering from the Inside Out: A mentalization-based individual therapy for mothers with substance use disorders In Suchman N, Pajulo M, & Mayes L (Eds.), Parenting and substance addiction: Developmental approaches to intervention (pp. 407–433). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suchman N, Mayes L, Conti J, Slade A, & Rounsaville B (2004). Rethinking parenting interventions for drug-dependent mothers: From behavior management to fostering emotional bonds. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 27, 179–185. 10.1016/josat.2004.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchman NE, DeCoste C, Castiglioni N, McMahon TJ, Rounsaville B, & Mayes L (2010). The Mothers and Toddlers Program, an attachment-based parenting intervention for substance using women: Post-treatment results from a randomized clinical pilot. Attachment & Human Development, 12, 483–504. 10.1080/14616734.2010.501983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchman NE, Decoste C, McMahon TJ, Rounsaville B, & Mayes L (2011). The Mothers and Toddlers program, an attachment-based parenting intervention for substance-using women: Results at 6-week follow-up in a randomized clinical pilot. Infant Mental Health Journal, 32, 427–449. 10.1002/imhj.20303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchman NE, DeCoste CL, McMahon TJ, Dalton R, Mayes LC, & Borelli J (2017). Mothering from the Inside Out: Results of a second randomized clinical trial testing a mentalization-based intervention for mothers in addiction treatment. Development and Psychopathology, 29, 617–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchman NE, Ordway MR, de Las Heras L, & McMahon TJ (2016). Mothering from the Inside Out: Results of a pilot study testing a mentalization-based therapy for mothers enrolled in mental health services. Attachment & Human Development, 1–22. 10.1080/14616734.2016.1226371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan G, Blevins D, & Kauth MR (2008). Translating clinical training into practice in complex mental health systems: Toward opening the “Black Box” of implementation. Implementation Science, 3, 1–7. 10.1186/1748-5908-3-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungar M, Liebenberg L, Landry N, & Ikeda J (2012). Caregivers, young people with complex needs, and multiple service providers: A study of triangulated relationships. Family Process, 51, 193–206. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2015). Strategic Plan FY 2014–2018. Retrieved February 24, 2015, from http://www.hhs.gov/strategic-plan/introduction.html

- van der Ende PC, van Busschbach JT, Nicholson J, Korevaar EL, & van Weeghel J (2016). Strategies for parenting by mothers and fathers with a mental illness. Journal of Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing, 23, 86–97. 10.1111/jpm.12283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks MR, Kostick K, Li J, Dunn J, McLaughlin P, Richmond P et al. (2015). Translation of the Risk Avoidance Partnership (RAP) for implementation in outpatient drug treatment clinics. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 47, 239–247. 10.1080/02791072.2015.1050535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, & Jensen PS (1999). Efficacy and effectiveness of child and adolescent psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Mental Health Service Research, 1, 125–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]