Abstract

Purpose of the review

To discuss the pathogenesis and recent advances in the management of KSHV-associated diseases.

Recent findings

KSHV, a gammaherpesvirus, causes several tumors and related diseases, including Kaposi sarcoma (KS), a form of multicentric Castleman disease (KSHV-MCD), and primary effusion lymphoma (PEL). These most often develop in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). KSHV-associated inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS) is a newly described syndrome with high mortality that has inflammatory symptoms like MCD but not the pathologic lymph node findings. KSHV-associated diseases are often associated with dysregulated human interleukin-6, and KSHV encodes a viral interleukin-6, both of which contribute to disease pathogenesis. Treatment of HIV is important in HIV-infected patients. Strategies to prevent KSHV infection may reduce the incidence of these tumors. Pomalidomide, an immunomodulatory agent, has activity in KS. Rituximab is active in KSHV-MCD but can cause KS exacerbation; rituximab plus liposomal doxorubicin is useful to treat KSHV-MCD patients with concurrent KS.

Summary

KSHV is the etiological agents of all forms of KS and several other diseases. Strategies employing immunomodulatory agents, cytokine inhibition and targeting of KSHV-infected cells are areas of active research.

Keywords: Kaposi sarcoma, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpes virus, human herpes virus-8

1-Introduction

Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus (KSHV), a gammaherpesvirus, was discovered in 1994 by Yuang Chang, Patrick S. Moore and colleagues, as the causative agent of AIDS-associated Kaposi sarcoma (KS)[1]. It is also called human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8). KSHV has been implicated as the etiologic agent of all forms of KS and several other diseases, including multicentric Castleman disease (MCD), primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) and a newly described syndrome, KSHV-associated inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS)[2–4]. KSHV is a necessary but insufficient etiological agent for these diseases.

2-KSHV Life Cycle

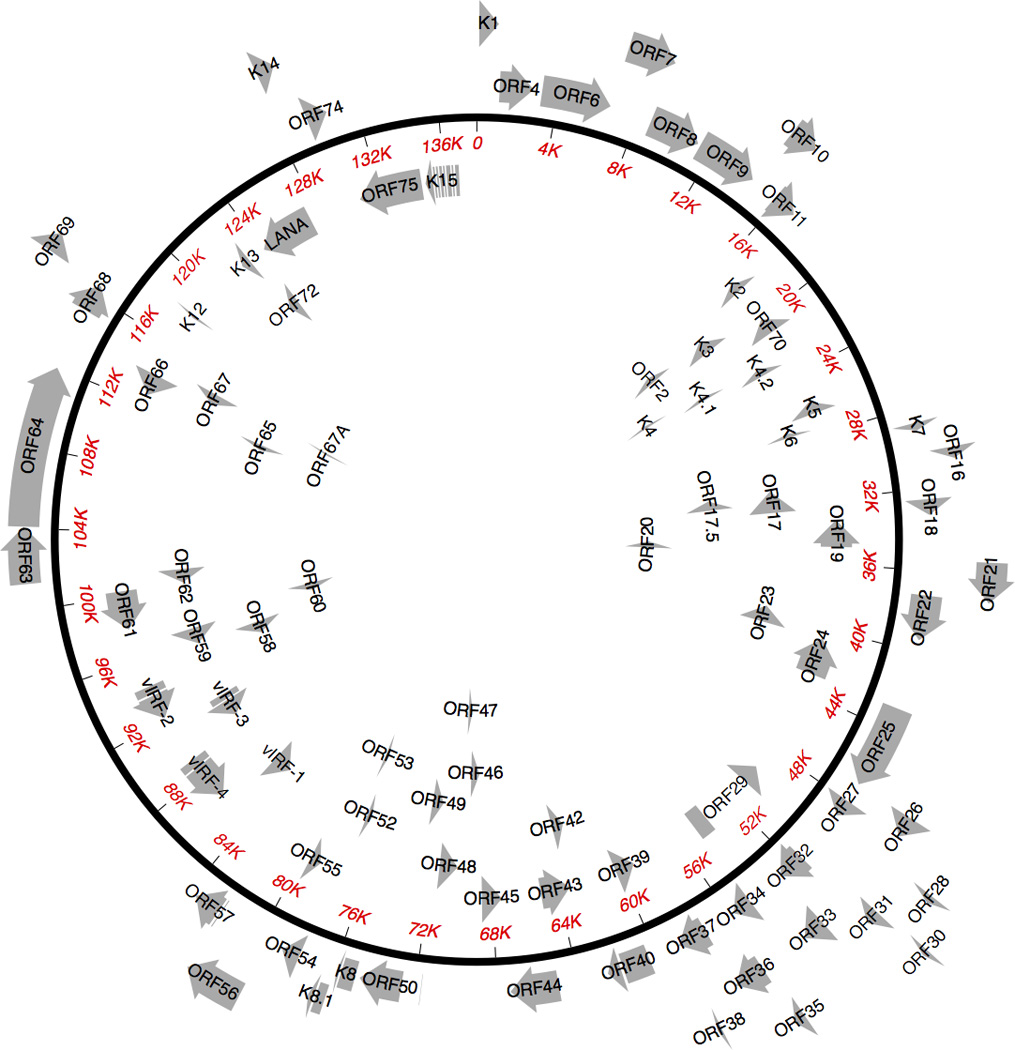

KSHV is a double stranded DNA gammaherpesvirus. After infection, the genome is maintained as an episome in the host cell nucleus. KSHV can infect a variety of cells including endothelial cells, B-cells, and monocytes. Figure 1 depicts the circularized KSHV genome. Upon infection of a cell, KSHV establishes latency, where only a few genes are expressed. Most reside in a cluster in the latency locus, and include: ORFK12 (kaposins), ORF71 (vFLIP), ORF72 (vCyclin), ORF73 (latency-associated nuclear antigen, LANA), and various viral microRNAs. These help maintain the viral episome, deter host immune responses, and promote survival and proliferation of infected cells[5–8].

Figure 1. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus genome.

The circular KSHV episome is shown with protein-encoding genes. Non-coding RNAs are not shown. ORF: open reading frame; LANA: latency-associated nuclear antigen; vIRF: viral interferon regulatory factor. Gene names starting with "K" are unique to KSHV.

Certain physiological signals cause the virus to enter the lytic phase, where all viral genes are expressed, progeny virions are produced and released, and the infected cell dies. The switch from latency to lytic replication is set in motion by ORF50 (replication and transcription activator protein, RTA). In addition to physiologic stressors such as hypoxia, various chemicals (sodium butyrate, valproic acid) can induce the lytic cycle[9]. Additional genes may be expressed in a more selective manner in otherwise latently infected cells and these are partially dependent on the specific cell type[10–12]. Latent infection is observed in the majority of tumor cells in KS lesions. However, around 1% of infected cells in KS express lytic genes, while a higher percentage express lytic genes in PEL and even more in MCD.

3- KSHV Transmission

KS prevalence and new infections remain high in men who have sex with men (MSM) in the US. KSHV is secreted in saliva, and there is evidence that common modes of transmission in MSM are through oral-anal contact, oral-penile contact, or use of saliva as a lubricant[13–17]; thus education regarding these practices may be useful in reducing its spread in this population. In Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), transmission often occurs during childhood, and may be in part through food premastication[18].

4-Pathogenesis of KSHV-Associated Malignancies

KSHV has evolved strategies to evade innate and specific immunity, induce proliferation, and prevent apoptosis of infected cells. These strategies can promote oncogenesis. KSHV also has pleotropic effects on cell signaling that contribute to oncogenesis and angiogenesis, a hallmark of KS. For example, the KSHV protein vFLIP stimulates activation of NF-kB and is implicated in KS, KSHV-MCD and PEL[19–21]. Various KSHV proteins promote activation of the AKT and mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways, which promote survival and growth and are upregulated in many cancers[12, 22–24]. Importantly, sirolimus, an inhibitor of mTOR, can treat KS in transplant patients[25, 26]. Expression of latent viral proteins is necessary for survival of PEL cell lines, and repression of specific KSHV latent genes can induce apoptosis[6, 27]. Also, KSHV-encoded miRNAs can increase B cell proliferation in an animal model and promote survival of infected cells[28–31]. p53 is wild-type in KSHV-infected cells; however LANA can inhibit p53 activity[32]. Activation of p53 induces apoptosis in KSHV-infected cells, suggesting that repression of p53 is important for survival of these cells[33]. Human interleukin 6 (hIL-6) is up regulated upon KSHV infection; this is mediated by several KSHV genes, such as vFLIP, kaposin B and a KSHV G protein coupled receptor (encoded by open reading frame 74 [ORF74])[34]. Also, KSHV encodes a homologue of hIL-6, viral IL-6 (vIL-6). It is believed that increased IL-6 expression benefits KSHV infection in part by inducing proliferation of B lymphocytes[35, 36]. Additionally, vIL-6 signaling can lead to increased VEGF expression to stimulate angiogenesis[37]. By contrast to other oncogenic viruses, there is evidence that certain lytic KSHV genes are important in oncogenesis. In particular, several studies have shown vGPCR (ORF74) is important in the pathogenesis of KS[38].

5- Kaposi Sarcoma

Kaposi sarcoma is the most common KSHV-associated tumor. There are four major epidemiologic subtypes: classic; iatrogenic or transplant-associated; endemic or African; and AIDS-related or epidemic. KS was first described in elderly men in Mediterranean or Eastern European regions and this form is called “classic” KS. Later on, a high incidence of KS in SSA was described[39]. In the 1970s, association of KS with immunosuppressive therapies such as steroids and cyclosporin was reported, providing initial evidence that immunossupression is an important cofactor[40]. In 1981, the development of KS in young gay men was one of the harbingers of the AIDS epidemic. MSM have a much higher incidence than other HIV risk groups, suggesting that another etiologic agent was causal; in 1994, KSHV was identified as the etiologic agent. The prevalence of KSHV parallels the incidence of KS in various populations. In AIDS, a low CD4+ count, lack of KSHV T-cell immunity and HIV viremia are associated with the highest KS risk[41–43]. In the combination anti-retroviral therapy (ART) era, KS incidence decreased by approximately 80%, but has since stabilized [44]. KS incidence in HIV patients remains substantially greater than the general population, even in those on ART with controlled HIV viremia and relatively preserved CD4+ counts. The number of HIV-infected persons in the United States is increasing and ageing, and it is possible that this may lead to an increase in the incidence of AIDS KS. The incidence of KS is particularly high in SSA because of the high prevalence of both HIV and KSHV infection; in some SSA countries, KS is the most common tumor in men [45].

The most common presentation of KS is multifocal cutaneous macules or nodules commonly involving the lower extremities. Edema, ulceration, bleeding, pain and secondary infection may cause significant morbidity, and patients often have psychological distress from visible stigmata of AIDS. Nodal, lung, gastrointestinal (GI), bones and other visceral KS may occur. Diagnosis is established with a biopsy showing KSHV-infected spindle cells. Staging requires evaluation of the skin and oral mucosa, while evaluation for visceral disease is generally limited to a chest X-ray and stool occult blood test, with additional evaluations prompted by symptoms or abnormal initial tests. KS patients were initially staged following the AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) Oncology Committee criteria, where T stands for tumor burden (T0 or T1), I for immune status (I0 or I1) and S for systemic illness (S0 or S1)[46]. Subscripts 0 and 1 denote good and poor risk respectively. Criteria for poor-risk parameters are as follows: T1 includes tumors with tumor-associated edema or ulceration, extensive oral or GI KS and KS in other non-nodal viscera; I1 includes CD4+ cell <150/uL; and S1 includes history of opportunistic infections and/or thrush, B symptoms, Karnofsky performance status <70 or other HIV related illnesses. In patients receiving ART, CD4+ cell counts are less important prognostically, and the ACTG classification has been modified, with T1S1 patients considered poor risk and all others (T0S0; T1S0, or T0S1) good risk[47]. Nonetheless, in patients with T1 KS, advanced immunosuppression, as measured by CD4 count <100/uL, remains an important predictor of death in some regions[48].

The natural history of KS varies. KS may worsen or improve spontaneously, often in tandem with changes in underlying immune function. Some patients have an indolent pattern while others present with aggressive growth. Patients with rapidly progressive KS should be evaluated for concurrent KSHV-MCD, PEL or KICS (see below). There is no evidence that KS can be “cured”, although long term remissions without continued specific therapy are possible. Initial KS treatment should be aimed at correcting the underlying immunodeficiency where feasible. In HIV patients, this includes ART. In transplant-related KS, replacing cyclosporine with sirolimus may lead to disease remission[26]. If KS is indolent and not affecting quality of life, patients may be followed with a “watch and wait” approach. Criteria for systemic treatment, i.e., treatment over and above improving immune status, include KS-related symptoms, rapidly growing KS, or psychological distress from cosmetic disfigurement or stigmatization[47]. Localized treatment is generally avoided, due to its systemic nature and local toxicities. Table 1 summarizes the main systemic treatment options [49–67]. For patients requiring systemic treatment, most physicians now use Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved liposomal anthracyclines as initial therapy[49–53]. Paclitaxel is approved by the FDA for patients who fail or do not tolerate this initial approach[54, 55]. Patients with KS often require treatment for many years, and current therapies are limited by toxicity or the risk of cumulative anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Effective and less toxic approaches are thus an unmet need. In addition, it will be important to develop effective oral agents for resource-limited settings. Pomalidomide has recently been shown to have promising activity in a Phase I/II trial[56].

Table 1.

Select Prospective Studies of Systemic Therapies for the Treatment of Kaposi Sarcoma

| Treatment | Dosage | Design | Response Rate | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pegylated liposomal anthracycline (doxorubicin and daunorubicin) |

20–40mg/m2 every 3 weeks |

1) PLDa × DBV [49]* 2) PLD × BV [50]* 3) PLD × PLDa [51] 4) PLD × Paclitaxel [52] 5) PLD × DBV [53]* |

25–59% (CR+PR) | Usually given as first line treatment due to similar RR to paclitaxel and better toxicity profile. Single agent pegylated liposomal anthracyclines yields similar RR to drug combination with a less toxic profile. FDA approved drug. |

| Paclitaxel | 100 mg/m2 every 2 weeks and 135 to 175mg/m2 every 3 weeks |

Phase 2 trials [54]* [55] |

56–71% (CR+PR) | Needs to be given with steroids, which may exacerbate KS in HIV patients. FDA approved drug. |

| Pomalidomide | 5mg daily for 21 out of 28 days |

Phase 1/2 [56, 57] | 68% (CR+PR) | Well tolerated, increases in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Effective in HIV infected and classic KS. |

| Vinorelbine | 30mg/2 every 2 weeks |

Phase 2 trial [58]* | 43% (CR+PR) | Anti-tubulin agent; usually reserved for patients that failed previous pegylated liposomal anthracycline (PLD) and/or paclitaxel therapy. |

| Etoposide | 50mg once a day for 7 out of 21 days |

Phase 2 trial [59] | 36% (CR+PR) | Risk of secondary myelodysplastic syndrome and leukemia with long term therapy. |

| Nab-paclitaxel | Nab-paclitaxel 100mg IV on days 1,8 and 15 of each 4-week cycle |

Phase 2 [60] | 100% (CR+PR) | Well tolerated. Steroid sparing. Evaluated in a small number of HIV-negative patients. |

| Bevacizumab | 15mg/kg every 3 weeks |

Phase 2 trial [61] | 31% (CR+PR) | Relatively low anti- tumor effect as monotherapy, but may improve tumor associated edema. |

| Imatinib | 400–600mg daily |

Phase 2 trial [62] | 33% (CR+PR) | Activating mutations in PDGF-R and c-kit did not correlated with responses. |

| COL-3 | MTD: 25 mg/m2/day |

Phase 1 trial [63] | 44% (CR+PR) | MMPs are involved in tumor invasion and are overexpressed in KS. COL-3 is a MMP inhibitor. |

| Interferon-alfa | Low dose (1million IU) or high dose (8– 10million IU) once a day |

Low dose or high dose with DDI [64]*or AZT [65]* |

Low dose group: DDI-40% and AZT- 8% (CR+PR) High dose group: DDI-55% and AZT- 31% (CR+PR) |

Unfavorable toxicity profile. FDA-approved drug. |

| ART | Three drug regimen following DHHS Guidelines |

Description of a prospective stage- stratified approach. T0 disease: ART alone T1 disease: ART + liposomal anthracycline [66] |

No RR described. 5-year OS: T0- 95% T1- 85% |

Patients with T1 KS treated with specific KS therapy in addition to ART still have a worse 5-year OS when compared to T0 patients treated with ART alone. |

| ART | Three drug regimen |

Summary of several studies of ART alone [67] |

T0 patients: 39/48 (81%) with (PR+ CR) T1 patients: only 4 patients identified in clinical trials that were treated with ART alone, of which 3 responded (PR+CR) |

In review of entire literature up until 2004, only 5 documented cases were identified in which patients with T1 KS responded to ART alone. |

| ART | Three drug regimen following DHHS Guidelines |

Randomized controlled trial of patients with T1 disease in SSA: ART vs. ART + CXT [48] |

ART alone: 39% (CR+PR) ART +CXT: 66% (CR+PR) |

CXT regimen in SSA trial reported in 2012: DBV or oral etoposide when DBV not available. |

PLDa: pegylated liposomal daunorubicin; PLD: pegylated liposomal doxorubicin; DBV: doxorubicin, bleomycin, vincristine; BV: bleomycin, vincristine; KS: Kaposi Sarcoma; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; ART: anti-retroviral therapy; SSA: Sub-Saharan Africa; CXT: chemotherapy; OS: overall survival; RR: response rate; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; DHHS: The US Department of Health and Human Services; PR: partial response; CR: complete response; SD: stable disease; DDI: didanosine; AZT: zidovudine; PDGF-R: platelet derived growth factor receptor; MMP: matrix metalloproteinases; MTD: maximum tolerated dose;

: studies conducted in the pre-ART era; ORR: overall response rate.

6 – Multicentric Castleman Disease

KSHV-associated MCD is a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder most common arising in HIV-infected patients. It appears to be more common in the ART era[68]. It is rarely reported in SSA, but this is likely because of substantial under-diagnosis. KSHV-MCD presents with intermittent inflammatory symptoms such as fever, night sweats, weight loss, fatigue, and non-specific respiratory and GI symptoms, along with hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy and edema. KSHV viral load (VL) is elevated during symptomatic flares, and decreases with disease treatment and remission[69]. Laboratory abnormalities include elevated C-reactive protein, hypoalbuminemia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, hyponatremia, and elevated immunoglobulins[69, 70]. There is no consensus definition of a KSHV-MCD flare; different groups use combinations of the symptoms and laboratory abnormalities[71, 72]. KSHV-MCD-associated symptoms are believed to be caused by an excess of cytokines, especially vIL-6, hIL-6 and human interleukin-10 (IL-10)[69, 73]. Patients with flares can have increased serum levels of vIL-6, hIL-6, or both[73]. There is evidence that vIL-6 can activate hIL-6, and may be the most important driving force[74].

KSHV-MCD diagnosis generally requires an excisional lymph node biopsy showing expansion of reactive plasma cells interspersed with KSHV-infected plasmablasts, as well as hyalinization of lymphoid follicles and increased capillary proliferation. A substantial subset express vIL-6, and a smaller subset also express other KSHV lytic antigens. Maturing B cells have high levels of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP-1), and there is evidence that that this can contribute to KSHV-MCD pathogenesis by inducing KSHV lytic activation and directly inducing expression of vIL-6[10].

KSHV-MCD can wax and wane, but untreated, is generally fatal within 2 years. There is no FDA-approved treatment. ART is indicated in HIV-associated KSHV-MCD but is generally insufficient. However, control of HIV viremia may reduce the likelihood of recurrence[75]. Treatment with rituximab or the combination of rituximab and liposomal doxorubicin often leads to clinical remission; prolonged remissions are observed, and this therapy and can improve survival[71, 76–78]. Patients may present with concurrent KS, and rituximab alone can cause KS exacerbation; rituximab plus liposomal doxorubicin can be particularly useful in such patients[76]. High-dose zidovudine in combination with valganciclovir targets KSHV-infected cells expressing lytic proteins, and has demonstrated activity in KSHV-MCD, although remissions appear more common with rituximab[79]. Table 2 summarizes the evidence for selected therapeutic options for KSHV-MCD.

Table 2.

Select Treatment Strategies for KSHV-MCD

| Therapy | Dosage | Rationale | Outcomes | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | 375mg/m2 weekly × 4 weeks [71,76] |

Rituximab eliminates CD20+ B cells |

92% SR rate at day 60, 71% at one year. Patients should have been treated with chemotherapy for at least 3 months with clinical response and should have experienced at least one recurrence of MCD attack after attempt to discontinue chemotherapy prior to initiating rituximab [71] 95% had remission of symptoms; 67% had a radiological response. 79% disease-free survival at 2 years [76] |

KS progression may occur (National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines version 1.2015 (NCCN Guidelines) |

| Rituximab + liposomal doxorubicin |

Rituximab 375mg/m2 + liposomal doxorubicin 20mg/m2 every 3 weeks [78] |

Rituximab may lead to worsening of KS lesions. Rituximab alone may be inadequate as single agent to treat KSHV-MCD. LD can target CD20-KSHV infected MCD plasmablasts and KS spindle cells |

Clinical response: 94% major clinical response (PR or better); 88% CR Biochemical response: 88% major response; 76% CR |

Well-tolerated, rapid clinical improvement. Listed as preferred line of treatment in patients with KSHV-MCD and concomitant KS (NCCN Guidelines) |

| High dose AZT + valganciclovir |

AZT 600mg orally every 6h + valganciclovir 900mg orally every 12h for 7 out of 21 days [79] |

ORF21 (KSHV lytic gene) can phosphorylate AZT and ganciclovir to toxic moieties; ORF36 (KSHV lytic gene) can phosphorylate ganciclovir |

Clinical responses: 86% major clinical response Biochemical responses: 50% major response; 21% CR; 29% PR |

Decrease in C-reactive protein and viral IL-6 noted from baseline to time of best clinical response (NCCN Guidelines) |

SR: sustained remission; KS: Kaposi Sarcoma; PR: partial response; CR: complete response; KSHV: Kaposi-sarcoma herpes virus; MCD: multicentric Castleman’s disease; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; AZT: zidovudine; IL-6: interleukin-6; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

7- Primary Effusion Lymphoma

Primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) is a KSHV–associated aggressive mature monoclonal B-cell lymphoma with a poor outcome[80]. Most cases arise in HIV patients. While relatively rare, PEL is likely under-diagnosed[81]. PEL presents with lymphomatous effusions, most commonly pleural, but also peritoneal, pericardial and even joint[82]. Extra-cavitary forms can involve the skin, lymph nodes, GI and central nervous system (CNS)[83]. PEL should be considered in any HIV patient with effusions, especially if they have KS and/or inflammatory symptoms similar to MCD and laboratory criteria for KICS (described below). Even small effusions should be evaluated. PEL cells generally have immunoglobulin gene rearrangement, but often lack surface immunoglobulin or common B-cell surface markers such as CD19, CD20, or CD79a. A diagnosis of PEL requires the presence of KSHV in the malignant cells; about 80% are coinfected with EBV. The immunophenotypic profile may include CD45, CD30, CD38, CD138, and interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4)[83–85].

In addition to imaging of the chest, abdomen and pelvis, staging should include brain MRI and lumbar puncture to look for CNS involvement. Serial evaluation of KSHV VL may provide additional information. Currently, there is no standard therapy. Administration of ART is key component for HIV infected patients, but is insufficient in itself. Dose-adjusted (DA) EPOCH (infusional cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, etoposide, vincristine and prednisone) or CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) with ART can yield 2-year survival rates of approximately 30–40% [80, 86]. Preclinical studies of pomalidomide or lenalidomide show activity in PEL cells, due in part to a reduction of IRF4 [87, 88]. Interestingly, both lenalidomide and pomalidomide have been shown to inhibit KSHV-induced downregulation of MHC class I expression in PEL cells[88]. A prospective trial using lenalidomide combined with rituximab and DA-EPOCH is being developed. Elevated cytokines such as IL-6 have been shown to correlate with poor prognosis in PEL patients and a substantial proportion meet criteria for KICS (described below)[86]. Even though PEL cells do not express CD20, rituximab should be used to treat PEL in patients with concurrent MCD, and may also be useful in other PEL patients by targeting cytokine production by KSHV-infected non-tumor B cells.

8 – KSHV Inflammatory Cytokine Syndrome (KICS)

Our group observed that some KSHV-infected patients manifested inflammatory symptoms similar to those in KSHV-MCD but did not have KSHV-MCD pathology. We described six such patients in a retrospective analysis [4]. Serum vIL6, hIL-6, IL-10 and serum KSHV VL were significantly higher than control patients with KS and no MCD-like symptoms. Based on this initial study, we have developed a working definition of KICS and have undertaken a prospective study of this condition[89, 90]. Our current understanding is that as in KSHV-MCD, the symptoms in these patients are caused by cytokine excess directly or indirectly caused by KSHV infection and not attributable to uncontrolled HIV[89]. KICS patients have a high risk of death, and anemia and hypoalbuminemia were poor prognostic indicators[89]. Many have KS and/or PEL. Unrecognized KICS may be an important cause of death in certain patients with AIDS-associated KS. Our findings highlight the importance of recognizing KICS in critically ill patients with HIV/KSHV co-infection and stress the unmet need to develop treatment strategies for this patient population. Table 3 displays the working criteria for KICS. The National Cancer Institute is currently evaluating several strategies to treat KSHV-associated diseases, including KICS (Table 4).

Table 3.

Working Definition of the KSHV-Inflammatory Cytokine Syndrome (KICS)

|

1- Clinical manifestations |

|||||

| a- Symptoms | Fever, fatigue, edema, cachexia, respiratory symptoms, GI disturbance, arthralgia and myalgia, altered mental state, neuropathy |

b- Laboratory abnormalities |

Anemia Thrombocytopenia Hypoalbuminemia Hyponatremia |

c- Radiographic abnormalities |

Adenopathy Splenomegaly Hepatomegaly Body effusions |

|

2- Systemic Inflammation |

Elevated C- reactive protein |

||||

|

3- KSHV viral activity |

KSHV VL in plasma (≥1000 copies/mL) or PBMC ((≥100 copies/106 cells) |

||||

|

4- No evidence of KSHV MCD |

If adenopathy present, requires histopathologic assessment of nodes |

||||

| For a diagnosis of KICS to be made, must have at least 2 clinical manifestations from at least 2 categories (symptoms, laboratory abnormalities and radiographic abnormalities) IN ADDITION to each of the criteria in 2, 3, and 4 | |||||

GI: gastrointestinal; KSHV: Kaposi Sarcoma herpes virus; VL: viral load; MCD: Multicentric Castleman’s disease; PBMC: peripheral mononuclear cells; GI: gastrointestinal; KSHV: Kaposi Sarcoma herpes virus; MCD: Multicentric Castleman’s disease; PBMC: peripheral mononuclear cells.

Adapted from [89].

Table 4.

Select On-going or Recently Completed Therapeutic Studies Open to Patients with KSHV-Associated Diseases

| Therapy | Disease | Rationale |

Clinical Trials.gov Identification (https://clinicatrials.gov) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selumetinib | KS | MEK 1/2 inhibitor | NCT01752569 |

| Nelfinavir | Gamma herpes virus- related tumors including KS |

Nelfinavir may activate lytic gene expression in gamma herpes virus tumors |

NCT02080416 |

| Pembrolizumab | Patients with HIV and refractory/advanced malignancies, including KS and PEL |

PD-1 inhibitor | NCT02595866 |

| Nivolumab+ Ipilimumab |

HIV- associated malignancies, including KS and PEL |

PD-1 inhibition combined with CTLA4 inhibition |

NCT02408861 |

| Pomalidomide + liposomal doxorubicin |

KS, MCD, KICS | Unmet need to treat patients with KSHV- MCD and KS as single agents alone are not usually sufficient |

NCT02659930 |

| DS-8895a | Advanced or metastatic EphA2 cancers |

EphA2 is an entry receptor for KSHV |

NCT02252211 |

| Tocilizumab | HIV positive MCD | IL-6 overproduction plays a role in MCD. Tocilizumab is a humanized anti-IL6 receptor antibody. Blocking human IL-6 may be sufficient to treat MCD by blocking paracrine and autocrine stimulation |

NCT01441063 |

| Sirolimus | HIV positive MCD | Rapamycin is directly toxic to KSHV infected cells [91]. Tumor responses in KS were associated with recovery of T cell memory responses against KSHV latent ORF73 and lytic K8.1 antigens [92] |

NCT01441063 |

| DA-EPOCH + lenalidomide |

KSHV-associated lymphomas (including PEL) |

Lenalidomide has in vitro direct antitumor effect in KSHV- lymphomas as well as immunomodulatory and anti-angiogenic effects |

Anticipated opening in 2016 |

| Lenalidomide | KS | Thalidomide has shown activity in KS. Lenalidomide is a more potent thalidomide derivative. |

NCT01057121 |

MEK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PEL: primary effusion lymphoma; KS: Kaposi sarcoma; MCD: Multicentric Castleman; KICS: Kaposi Sarcoma Inflammatory Cytokine Syndrome; PD1: programmed cell death protein 1; CTLA4: cytotoxic T-lymphocyte protein 4; IL-6: interleukin-6; EphA2: ephrin receptor tyrosine kinase A2; DA-EPOCH: dose-adjusted etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin.

9- Conclusions

KSHV-associated diseases represent a heterogeneous group of disorders. The principal manifestations are from tumor formation (KS and PEL) and from cytokine excess (MCD and KICS). A better understanding and recognition of this cluster of entities is essential for the development of improved prevention and treatment approaches. It will be useful to understand the factors leading to these different diseases in different KSHV-infected patients. Promising efforts to develop effective therapies include targeting specific viral genes, targeting dysregulated cellular pathways, inhibiting abnormal cytokine expression, and immunomodulatory approaches.

Key points.

KSHV-associated diseases include KS, KSHV-MCD, PEL and KICS

KICS is a newly described high mortality syndrome of KSHV-infected patients

There are few FDA-approved therapies to treat KSHV-associated diseases

KSHV-associated diseases are an important cause of morbidity and mortality in HIV patients

Treatment options likely include inhibition of abnormal cytokine expression and immunomodulatory agents

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute.

None

R. Y. reports a CRADA with Celgene Corp., nonfinancial support from Hoffman LaRoche and Bayer. In addition, R. Y. has a patent on the treatment of KS with IL-12, patents pending for a peptide vaccine against HIV, and a patent application for the use of pomalidomide and lenalidomide to treat KSHV-associated diseases and induce immunologic changes. The spouse of R. Y. is a coinventor on a patent describing the measurement of KSHV vIL-6. All these inventions were made when the scientists were employees of the US. All rights, title, and interest to this patent have been assigned to the US Department of Health and Human Services. The government conveys a portion of the royalties it receives to its employee inventors under the Federal Technology Transfer Act of 1986 (PL 99–502). T. S. U. reports a CRADA with Celgene Corporation, and non-financial support from Hoffman LaRoche and Bayer Corporation, outside the submitted work. In addition, T. S. U. is a co-inventor on the patent application described above for pomalidomide and lenalidomide.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: All other authors report no potential conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References and Recommended Reading

- 1. Chang Y, Cesarman E, Pessin MS, et al. Identification of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. Science. 1994;266:1865–1869. doi: 10.1126/science.7997879. ** Initial description of KSHV from a patient with Kaposi sarcoma.

- 2. Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1186–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321802. * First description of association of KSHV with primary effusion lymphoma.

- 3. Soulier J, Grollet L, Oksenhendler E, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in multicentric Castleman's disease. Blood. 1995;86:1276–1280. * First description oif association of KSHV with multicentric Castleman disease.

- 4. Uldrick TS, Wang V, O'Mahony D, et al. An interleukin-6-related systemic inflammatory syndrome in patients co-infected with Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and HIV but without Multicentric Castleman disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:350–358. doi: 10.1086/654798. * First description of KSHV-associated inflammatory cytokine syndrome (KICS).

- 5.Cotter MA, 2nd, Robertson ES. The latency-associated nuclear antigen tethers the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus genome to host chromosomes in body cavity-based lymphoma cells. Virology. 1999;264:254–264. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guasparri I, Keller SA, Cesarman E. KSHV vFLIP is essential for the survival of infected lymphoma cells. J Exp Med. 2004;199:993–1003. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 7. Lee HR, Amatya R, Jung JU. Multi-step regulation of innate immune signaling by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Virus Res. 2015;209:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.03.004. * Description of how KSHV modulated the innate immune response.

- 8. Valiya Veettil M, Dutta D, Bottero V, et al. Glutamate secretion and metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 expression during Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection promotes cell proliferation. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004389. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004389. ** This is the first major study of the roles of the glutamate receptor with KSHV infection. Repression of glutamate release and receptor function results in suppression of proliferation of KSHV-infected cells.

- 9.Davis DA, Rinderknecht AS, Zoeteweij JP, et al. Hypoxia induces lytic replication of Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Blood. 2001;97:3244–3250. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.3244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hu D, Wang V, Yang M, et al. Induction of Kaposi's Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus-Encoded Viral Interleukin-6 by X-Box Binding Protein 1. J Virol. 2016;90:368–378. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01192-15. * This study reports expression of viral interleukin-6 (vIL6) in lymph nodes of patients with KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman’s disease. Expression of vIL6 can be induced by X-box binding protein.

- 11.Rivas C, Thlick AE, Parravicini C, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus LANA2 is a B-cell-specific latent viral protein that inhibits p53. J Virol. 2001;75:429–438. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.429-438.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang HH, Ganem D. A unique herpesviral transcriptional program in KSHV-infected lymphatic endothelial cells leads to mTORC1 activation and rapamycin sensitivity. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dukers NH, Renwick N, Prins M, et al. Risk factors for human herpesvirus 8 seropositivity and seroconversion in a cohort of homosexual men. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:213–224. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pauk J, Huang ML, Brodie SJ, et al. Mucosal shedding of human herpesvirus 8 in men. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1369–1377. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011093431904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin JN, Ganem DE, Osmond DH, et al. Sexual transmission and the natural history of human herpesvirus 8 infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:948–954. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804023381403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koelle DM, Huang ML, Chandran B, et al. Frequent detection of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) DNA in saliva of human immunodeficiency virus-infected men: clinical and immunologic correlates. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:94–102. doi: 10.1086/514045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler LM, Osmond DH, Jones AG, et al. Use of saliva as a lubricant in anal sexual practices among homosexual men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;50:162–167. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819388a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rohner E, Wyss N, Heg Z, et al. HIV and human herpesvirus 8 co-infection across the globe: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2016;138:45–54. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29687. ** This systematic review describes studies reporting the prevalence of KSHV in HIV positive and negative patients in several countries. HIV positive patients are more likely to be KSHV positive than HIV negative patients and this association is strongest in men who have sex with men, children and hemophiliacs.

- 19.Grossmann C, Podgrabinska S, Skobe M, et al. Activation of NF-kappaB by the latent vFLIP gene of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for the spindle shape of virus-infected endothelial cells and contributes to their proinflammatory phenotype. J Virol. 2006;80:7179–7185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01603-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keller SA, Schattner EJ, Cesarman E. Inhibition of NF-kappaB induces apoptosis of KSHV-infected primary effusion lymphoma cells. Blood. 2000;96:2537–2542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hughes DJ, Wood JJ, Jackson BR, et al. NEDDylation is essential for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus latency and lytic reactivation and represents a novel anti-KSHV target. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004771. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004771. ** The ubiquitin ligase, NEDD8, has emerged as interesting therapeutic target, in part, to the development of a new inhibitor of NEDD8 activation. Inhibition of NEDD8 activity causes primary effusion lymphoma cytotoxicity and other literature suggests that this pathway may be an important target for other viral infections, including HIV.

- 22.Tomlinson CC, Damania B. The K1 protein of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus activates the Akt signaling pathway. J Virol. 2004;78:1918–1927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1918-1927.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sodhi A, Chaisuparat R, Hu J, et al. The TSC2/mTOR pathway drives endothelial cell transformation induced by the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris VA, Punjabi AS, Lagunoff M. Activation of Akt through gp130 receptor signaling is required for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-induced lymphatic reprogramming of endothelial cells. J Virol. 2008;82:8771–8779. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00766-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roy D, Sin SH, Lucas A, et al. mTOR inhibitors block Kaposi sarcoma growth by inhibiting essential autocrine growth factors and tumor angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2235–2246. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stallone G, Schena A, Infante B, et al. Sirolimus for Kaposi's sarcoma in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1317–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godfrey A, Anderson J, Papanastasiou A, et al. Inhibiting primary effusion lymphoma by lentiviral vectors encoding short hairpin RNA. Blood. 2005;105:2510–2518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-3052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boss IW, Nadeau PE, Abbott JR, et al. A Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded ortholog of microRNA miR-155 induces human splenic B-cell expansion in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2Rgammanull mice. J Virol. 2011;85:9877–9886. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05558-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gottwein E, Cullen BR. A human herpesvirus microRNA inhibits p21 expression and attenuates p21-mediated cell cycle arrest. J Virol. 2010;84:5229–5237. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00202-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kieffer-Kwon P, Happel C, Uldrick TS, et al. KSHV MicroRNAs Repress Tropomyosin 1 and Increase Anchorage-Independent Growth and Endothelial Tube Formation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moody R, Zhu Y, Huang Y, et al. KSHV microRNAs mediate cellular transformation and tumorigenesis by redundantly targeting cell growth and survival pathways. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003857. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friborg J, Jr, Kong W, Hottiger MO, et al. p53 inhibition by the LANA protein of KSHV protects against cell death. Nature. 1999;402:889–894. doi: 10.1038/47266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarek G, Kurki S, Enback J, et al. Reactivation of the p53 pathway as a treatment modality for KSHV-induced lymphomas. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1019–1028. doi: 10.1172/JCI30945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.An J, Sun Y, Sun R, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encoded vFLIP induces cellular IL-6 expression: the role of the NF-kappaB and JNK/AP1 pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22:3371–3385. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Monini P, Colombini S, Sturzl M, et al. Reactivation and persistence of human herpesvirus-8 infection in B cells and monocytes by Th-1 cytokines increased in Kaposi's sarcoma. Blood. 1999;93:4044–4058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sirianni MC, Vincenzi L, Fiorelli V, et al. gamma-Interferon production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes from Kaposi's sarcoma patients: correlation with the presence of human herpesvirus-8 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and lesional macrophages. Blood. 1998;91:968–976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aoki Y, Jaffe ES, Chang Y, et al. Angiogenesis and hematopoiesis induced by Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-encoded interleukin-6. Blood. 1999;93:4034–4043. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montaner S, Sodhi A, Ramsdell AK, et al. The Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor as a therapeutic target for the treatment of Kaposi's sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:168–174. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook-Mozaffari P, Newton R, Beral V, et al. The geographical distribution of Kaposi's sarcoma and of lymphomas in Africa before the AIDS epidemic. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1521–1528. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi's sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy: a 5-year material of Kaposi's sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626–2630. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197812)42:6<2626::aid-cncr2820420618>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biggar RJ, Chaturvedi AK, Goedert JJ, et al. AIDS-related cancer and severity of immunosuppression in persons with AIDS. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:962–972. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guihot A, Dupin N, Marcelin AG, et al. Low T cell responses to human herpesvirus 8 in patients with AIDS-related and classic Kaposi sarcoma. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1078–1088. doi: 10.1086/507648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Silverberg MJ, Chao C, Leyden WA, et al. HIV infection, immunodeficiency, viral replication, and the risk of cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:2551–2559. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Goedert JJ, et al. Trends in cancer risk among people with AIDS in the United States 1980–2002. AIDS. 2006;20:1645–1654. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238411.75324.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide in 2012. [22 August 2016];GLOBOCAN 2012 (IARC). Web. Retrieved from: http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/Map.aspx.

- 46.Krown SE, Testa MA, Huang J AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: prospective validation of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group staging classification. AIDS Clinical Trials Group Oncology Committee. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:3085–3092. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.9.3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nasti G, Talamini R, Antinori A, et al. AIDS-related Kaposi's Sarcoma: evaluation of potential new prognostic factors and assessment of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group Staging System in the Haart Era--the Italian Cooperative Group on AIDS and Tumors and the Italian Cohort of Patients Naive From Antiretrovirals. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2876–2882. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mosam A, Shaik F, Uldrick TS, et al. A randomized controlled trial of highly active antiretroviral therapy versus highly active antiretroviral therapy and chemotherapy in therapy-naive patients with HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:150–157. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318251aedd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gill PS, Wernz J, Scadden DT, et al. Randomized phase III trial of liposomal daunorubicin versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine in AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2353–2364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.8.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stewart S, Jablonowski H, Goebel FD, et al. Randomized comparative trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin versus bleomycin and vincristine in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. International Pegylated Liposomal Doxorubicin Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:683–691. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cooley T, Henry D, Tonda M, et al. A randomized, double-blind study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. Oncologist. 2007;12:114–123. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cianfrocca M, Lee S, Von Roenn J, et al. Randomized trial of paclitaxel versus pegylated liposomal doxorubicin for advanced human immunodeficiency virus-associated Kaposi sarcoma: evidence of symptom palliation from chemotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116:3969–3977. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Northfelt DW, Dezube BJ, Thommes JA, et al. Pegylated-liposomal doxorubicin versus doxorubicin, bleomycin, and vincristine in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: results of a randomized phase III clinical trial. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2445–2451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.7.2445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Welles L, Saville MW, Lietzau J, et al. Phase II trial with dose titration of paclitaxel for the therapy of human immunodeficiency virus-associated Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1112–1121. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.3.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tulpule A, Groopman J, Saville MW, et al. Multicenter trial of low-dose paclitaxel in patients with advanced AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma. Cancer. 2002;95:147–154. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Polizzotto MN, Uldrick T, Wyvill K, et al. Pomalidomide for Kaposi Sarcoma in people with and without HIV: A phase I/II study. J. Clinical Oncology. 2016 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.3812. In press. * Pomalidomide was well tolerated in patients with KS (both with and without HIV infection) at 5mg orally daily for 21 out of 28 days. The overall response rate was 68%, with 18% complete responses.

- 57. Polizzotto MN, Sereti I, Uldrick T, et al. Pomalidomide induces expansion of activated and central memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vivo in patients with and without HIV infection. Blood. 2014;124:4128–4128. * Patients with Kaposi sarcoma treated with pomalidomide showed significant increases in the number of CD4 and CD8 T cells.

- 58.Nasti G, Errante D, Talamini R, et al. Vinorelbine is an effective and safe drug for AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: results of a phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1550–1557. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.7.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Evans SR, Krown SE, Testa MA, et al. Phase II evaluation of low-dose oral etoposide for the treatment of relapsed or progressive AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: an AIDS Clinical Trials Group clinical study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3236–3241. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Iuliano F, Cervo G, Iuliano E, et al. Weekly nab-paclitaxel in elderly patients with classic Kaposi sarcoma; 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; 2016. Abstract e22539. * Article describing the use of weekly nab-paclitaxel in elderly patients with classic KS as an effective and less toxic regimen for this patient population.

- 61.Uldrick TS, Wyvill KM, Kumar P, et al. Phase II study of bevacizumab in patients with HIV-associated Kaposi's sarcoma receiving antiretroviral therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1476–1483. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Koon HB, Krown SE, Lee JY, et al. Phase II trial of imatinib in AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma: AIDS Malignancy Consortium Protocol 042. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:402–408. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.6365. * Imatinib has activity in AIDS-associated Kaposi Sarcoma. Activating mutations in PDGF-R and c-kit did not correlate with response.

- 63.Cianfrocca M, Cooley TP, Lee JY, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor COL-3 in the treatment of AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma: a phase I AIDS malignancy consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:153–159. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Krown SE, Li P, Von Roenn JH, et al. Efficacy of low-dose interferon with antiretroviral therapy in Kaposi's sarcoma: a randomized phase II AIDS clinical trials group study. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22:295–303. doi: 10.1089/107999002753675712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shepherd FA, Beaulieu R, Gelmon K, et al. Prospective randomized trial of two dose levels of interferon alfa with zidovudine for the treatment of Kaposi's sarcoma associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection: a Canadian HIV Clinical Trials Network study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1736–1742. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bower M, Dalla Pria A, Coyle C, et al. Prospective stage-stratified approach to AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:409–414. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.6757. ** This study prospectively evaluated 469 patients with HIV and KS. Patients with T0 disease were given antiretroviral therapy (ART) alone and patients with T1 disease were received liposomal doxorubicin in addition to ART. Overall 5-year survival was 92% for T0 and 95% for T1 KS. This study suggests that stratifiyng KS treatment according to risk may reduce exposure to chemotherapy to early stage KS.

- 67.Krown S. Highly active antiretroviral therapy in AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma: implications for the desing of therapeutic trials in patients with advanced, symptomatic Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:218–219. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Powles T, Stebbing J, Bazeos A, et al. The role of immune suppression and HHV-8 in the increasing incidence of HIV-associated multicentric Castleman's disease. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:775–779. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Polizzotto MN, Uldrick TS, Wang V, et al. Human and viral interleukin-6 and other cytokines in Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2013;122:4189–4198. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-519959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oksenhendler E, Duarte M, Soulier J, et al. Multicentric Castleman's disease in HIV infection: a clinical and pathological study of 20 patients. AIDS. 1996;10:61–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gerard L, Berezne A, Galicier L, et al. Prospective study of rituximab in chemotherapy-dependent human immunodeficiency virus associated multicentric Castleman's disease: ANRS 117 CastlemaB Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3350–3356. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Uldrick TS, Polizzotto MN, Yarchoan R. Recent advances in Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:495–505. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e328355e0f3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Oksenhendler E, Carcelain G, Aoki Y, et al. High levels of human herpesvirus 8 viral load, human interleukin-6, interleukin-10, and C reactive protein correlate with exacerbation of multicentric castleman disease in HIV-infected patients. Blood. 2000;96:2069–2073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suthaus J, Stuhlmann-Laeisz C, Tompkins VS, et al. HHV-8-encoded viral IL-6 collaborates with mouse IL-6 in the development of multicentric Castleman disease in mice. Blood. 2012;119:5173–5181. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-09-377705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zeng Y, Zhang X, Huang Z, et al. Intracellular Tat of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 activates lytic cycle replication of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus: role of JAK/STAT signaling. J Virol. 2007;81:2401–2417. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bower M, Powles T, Williams S, et al. Brief communication: rituximab in HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:836–839. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-12-200712180-00003. * Article describing the treatment of KSHV-MCD with rituximab.

- 77.Gerard L, Michot JM, Burcheri S, et al. Rituximab decreases the risk of lymphoma in patients with HIV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2012;119:2228–2233. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-376012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Uldrick TS, Polizzotto MN, Aleman K, et al. Rituximab plus liposomal doxorubicin in HIV-infected patients with KSHV-associated multicentric Castleman disease. Blood. 2014;124:3544–3552. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-586800. * Rituximab can worsen Kaposi Sarcoma (KS) in patients with Multicentric Castleman disease. Rituximab plus liposomal doxorubicin is active and safe in patients with MCD.

- 79.Uldrick TS, Polizzotto MN, Aleman K, et al. High-dose zidovudine plus valganciclovir for Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-associated multicentric Castleman disease: a pilot study of virus-activated cytotoxic therapy. Blood. 2011;117:6977–6986. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-317610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boulanger E, Gerard L, Gabarre J, et al. Prognostic factors and outcome of human herpesvirus 8-associated primary effusion lymphoma in patients with AIDS. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4372–4380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mbulaiteye SM, Biggar RJ, Goedert JJ, et al. Pleural and peritoneal lymphoma among people with AIDS in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:418–421. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200204010-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nador RG, Cesarman E, Chadburn A, et al. Primary effusion lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity associated with the Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpes virus. Blood. 1996;88:645–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chadburn A, Hyjek E, Mathew S, et al. KSHV-positive solid lymphomas represent an extra-cavitary variant of primary effusion lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1401–1416. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000138177.10829.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Carbone A, Gloghini A, Larocca LM, et al. Expression profile of MUM1/IRF4, BCL-6, and CD138/syndecan-1 defines novel histogenetic subsets of human immunodeficiency virus-related lymphomas. Blood. 2001;97:744–751. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carbone A, Gloghini A, Cozzi MR, et al. Expression of MUM1/IRF4 selectively clusters with primary effusion lymphoma among lymphomatous effusions: implications for disease histogenesis and pathogenesis. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:247–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Uldrick T, Bhutani M, Polizzotto M, et al. Inflammatory cytokines, hyperferritinemia and IgE are prognostic in patients with KSHV-associated lymphomas treated with curative intent. American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition; 2014; San Francisco, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 87. Gopalakrishnan R, Matta H, Tolani B, et al. Immunomodulatory drugs target IKZF1-IRF4-MYC axis in primary effusion lymphoma in a cereblon-dependent manner and display synergistic cytotoxicity with BRD4 inhibitors. Oncogene. 2016;35:1797–1810. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.245. ** This study reports enhanced survival in mice implanted with KSHV primary effusion lymphoma cells with the combination of an immunomodulatory drug, lenalidomide, and an epigenetic reader inhibitor, JQ-1.

- 88. Davis D, Anagho H, Mishra S, et al. Lenalidomide and pomalidomide inhibit KSHV-induced downregulation of MHC class I expression in primary effusion lymphoma cells. 15th International Conference on Malignancies in AIDS and Other Acquired Immunodeficiencies; 2015; Bethesda, MD. * Lenalidomide and pomalidomide inhibit proliferation of primary effusion cell lines and inhibit Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-induced downregulation of MHC-class I.

- 89. Polizzotto MN, Uldrick TS, Wyvill KM, et al. Clinical Features and Outcomes of Patients With Symptomatic Kaposi Sarcoma Herpesvirus (KSHV)-associated Inflammation: Prospective Characterization of KSHV Inflammatory Cytokine Syndrome (KICS) Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:730–738. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ996. * Patients with KSHV-associated Inflammatory Cytokine Syndrome (KICS) have a high rate of KSHV-associated tumors, elevated interleukin 6 and 10 and a high mortality.

- 90.Polizzotto MN, Uldrick TS, Hu D, et al. Clinical Manifestations of Kaposi Sarcoma Herpesvirus Lytic Activation: Multicentric Castleman Disease (KSHV-MCD) and the KSHV Inflammatory Cytokine Syndrome. Front Microbiol. 2012;3:73. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sin SH, Roy D, Wang L, et al. Rapamycin is efficacious against primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cell lines in vivo by inhibiting autocrine signaling. Blood. 2007;109:2165–2173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Barozzi P, Bonini C, Potenza L, et al. Changes in the immune responses against human herpesvirus-8 in the disease course of posttransplant Kaposi sarcoma. Transplantation. 2008;86:738–744. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318184112c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]