Abstract

Environmental and genetic factors exert important influences on lifespan and neoplastic transformation. We have previously shown that spontaneous tumors form frequently in mice homozygous for a full-length Brca1 deletion. In general, mutations of BRCA1 are closely associated with induction of breast and ovarian cancers but are also known to contribute to the incidence of other cancers at a low frequency. Female Brca1-mutant mice (Brca1co/coMMTV-cre) were generated by crossing Brca1 conditional knockout mice and MMTV-cre mice, and the occurrence of lacrimal gland abnormalities and tumors was followed until mice reached 18 months of age. Lacrimal gland tumors, which occur at a very low frequency in the human population (1 per 1,000,000 per year), were detected in 7 cases of Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice (2.75%) older than 9 months of age. None of seven mice exhibited any abnormality in the mammary gland including neoplasia, suggesting lacrimal gland tumor is spontaneously and independently formed. These tumors, which were detected in seven mutant mice that displayed exophthalmoses, were malignant, originated from epithelial cells, and were identified as acinic cell carcinoma by pathological analysis. Further analysis revealed that tumorigenesis was accompanied by the accumulation of cyclin D1 and decreased expression of the cellular oncogenes, c-Myc, c-Jun, and c-Raf. Tumors also exhibited rearrangement of cytoskeletal proteins, including β-catenin, keratin 5, and vimentin, depending on tumor progression. These results suggest that BRCA1 is involved in genetic stability of the lacrimal gland, providing new insight into genomic instability in organism maintenance and tumorigenesis of the lacrimal gland.

1. Introduction

The loss of BRCA1, one of the most widely studied tumor-suppressor proteins, is transmitted hereditarily. BRCA1 functions have been extensively investigated in multiple organisms, particularly in mice, where gene targeting has been applied to introduce a number of different mutations into Brca1 (reviewed [1]). Depending on the mutation, Brca1-mutant mice exhibit various abnormal phenotypes, including developmental defects, growth retardation, apoptosis, premature senescence, DNA damage repair abnormalities, centrosome amplification, deregulation of the cell cycle, and genetic instability [2, 3]. In the BRCA1-mutant carrier, breast and ovarian cancers are the predominant abnormalities in whole-body haploinsufficiency. However, several reports have described a significantly increased risk of pancreatic, prostate, colorectal, esophageal, liver, stomach, and uterine cancers with alterations in BRCA1 [4, 5].

Lacrimal gland tumors are very rare in humans, with an estimated incidence of 1 per 1 million individuals per year [6]. Although many types of tumors have been identified in the lacrimal gland, they can be roughly divided into those that originate in epithelial cells and those with a nonepithelial origin. Notably, about half of epithelial-based lacrimal gland lesions are malignant [7]. The primary treatment for benign lacrimal gland tumors is surgical resection, whereas malignant tumors are generally removed surgically followed by radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy [8]. Hadron beam therapy has also been considered a nonsurgical treatment option for patients not suitable for surgical treatment [9]. However, there is some controversy surrounding therapeutic options, particularly for malignant tumors. Although the prognosis for patients with benign type tumors is generally good, malignant lacrimal gland tumors are often aggressive and tend to recur frequently, resulting in a lower survival rate [8]. However, because of the limited number of cases and few opportunities to clinical attempt, few large improvements have been made in its prevention or treatment.

Here, based on an investigation of seven cases of lacrimal tumors from Brca1-mutant mice, we report the presence of acinic cell carcinomas in the lacrimal gland and establish the characteristics of BRCA1-associated lacrimal tumors by comparing them with those of BRCA1-associated breast cancer and typical lacrimal tumors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Experiments

Brca1 conditional knockout and MMTV- (mouse mammary tumor virus-) cre transgenic mice were provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI, USA) mouse repository. Female Brca1-mutant mice (Brca1co/coMMTV-cre) were generated by crossing Brca1 conditional knockout mice, with MMTV-cre mice, originally generated by Dr. Deng and Dr. Hennighausen, respectively [10, 11]. Mutant mice and wild-type littermates were examined weekly for evidence of abnormalities or tumors up to 18 months of age. In mice that developed symptoms, tissues were collected, divided, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C or fixed in 10% (v/v) buffered formalin. Tumor status of a 10-month-old mouse was examined by acquiring tumor images using a 7-T MR imager (Bruker BioSpec, Rheinstetten, Germany) from anesthetized mice by inhalation of isoflurane (2.0% isoflurane in air). Tumor volume was calculated according to the formula, V = (L × W × D × π)/6, where V is volume, L is length, W is width, and D is depth. All procedures involving animals and their care were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Cancer Center (Goyang, Korea) followed by the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (US National Research Council).

2.2. Histology and Immunohistochemical Staining

For histology, dissected tissues were immediately fixed in 10% (v/v) formalin and embedded in paraffin. Tumor sections (5 μm) were deparaffinized and rehydrated in xylene and graded ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was performed at 125°C for 3 min by a decloaking chamber (Biocare Medical, Pacheco, CA, USA) in target retrieval solution (Dako, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Antigenic proteins were detected using a Zymed Histostain kit (Invitrogen-Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The following primary antibodies (1 : 100 dilution) were used: anti-cyclin D1 (#2978), anti-vimentin (#5741), anti-β-catenin (#8480), (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), anti-keratin 5 (#905504, BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and anti-PCNA (#HPA030522, Atlas Antibodies, Bromma, Sweden). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stainings were performed with automated H&E stainer (ST5010 Autostainer XL, Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.3. Immunoblotting

Western blot analyses were carried out according to standard procedures using enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Pierce-Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). In brief, tumor tissues were washed three times with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were extracted with handheld homogenizer in the buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, and 1x protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Penzberg, Germany). After centrifugation at 15000 x g for 30 min, the supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford method with BSA as a standard. The samples were then electrophoresed on 4–20% (w/v) Novex Tris-Glycine minigels (Invitrogen-Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA). The separated proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Merck-Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), then blocked with PBS/0.1% Tween 20 (PBST) containing 3% bovine serum albumin (Fraction V). Primary antibody bindings (1 : 1000 dilution) were performed overnight at 4°C. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA, USA) was used as a secondary antibody. Membranes were immersed with SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce-Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA), exposed to Hyperfilm ECL (Amersham-GE Heathcare, Chicago, IL, USA), and then developed. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-c-Myc (#9402), anti-c-Jun (#2361), anti-c-Raf (#9421), anti-JNK (#4668), anti-cyclin D1 (#2978), anti-vimentin (#5741), anti-β-actin (#8457) (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and anti-PCNA (#HPA030522, Atlas Antibodies, Bromma, Sweden). The primary antibodies applied in this study were reacted to mouse proteins and generated in rabbit to avoid the cross-reactivity with the mouse blood in the tumor tissues.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of Lacrimal Gland Tumors in Brca1-Mutant Mice

For the studies of BRCA1-associated breast cancer, we generated the female Brca1 conditional knockout mice with MMTV-cre-mediated recombination (Brca1co/coMMTV-cre). The cohort of Brca1-mutant mice consists of 254 individuals. Mice were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility with a HEPA-filter-containing air ventilation cage system. Of these female mice, currently seven (2.75%) exhibited exophthalmoses, swelling around the eye, and an opaque eyeball in a single side of the eye, whereas none of their wild-type littermates (Brca1co/co or Brca1+/coMMTV-cre) exhibited a similar phenotype over the same period. At the same period, Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mutant mice showed a high incidence of mammary tumors (56.7%). However, these seven mice with lacrimal tumor did not exhibit any other abnormality including mammary tumor. These phenotypes manifested when mice were 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, and 17 months old, ages that correspond to the initiation of menopause or the postmenopause period. The 9, 10, and 16 months of age mice developed a tumor mass behind the eyeball in each case (Figures 1(a)–1(d)). To further assess these eye abnormalities, we scanned the 10-month-old mouse with exophthalmos by magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. A tumor with a size of 7.4 × 8.6 × 9.0 mm was identified in the eye region; the shape and location of the eye-associated tumor were confirmed upon dissection (Figure 1(e)). To confirm the loss of Brca1 in lacrimal tumor, we examined the deletion of Brca1 in the DNA of lacrimal tumors with normal lacrimal glands from wild-type mice as control (Figure 1(f)). The analysis of genomic DNA showed that loss of Brca1 was exclusively detected in the tumor tissues from mutant mice but not in the normal lacrimal gland of wild-type mice (Figure 1(g)).

Figure 1.

Abnormal eye phenotypes in Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice. (a–d) Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice that developed tumors at 9 (a), 16 (b), 17 (c), and 10 (d) months of age. Top: the mice exhibited exophthalmoses, protrusions around the eye, and opaque eyeballs. Bottom: dissected eyes and eye-associated tumors from the corresponding Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice. (e) Representative MR scan image of Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mouse that developed a tumor at 10 months of age. Lacrimal tumor (indicated by arrow) side was expanded to the eye region while eye (e) in other side was intact. (f) Targeting construction of Brca1 deletion by cre recombinase. P1, P2, and P3 represent the primers for detection of targeted mutation and deletion. (g) PCR analysis against Brca1 using primers as indicated by the numbers. PCR products specific for Brca1 knockout (P1/P3) were detected in lacrimal tumors but not in normal lacrimal gland.

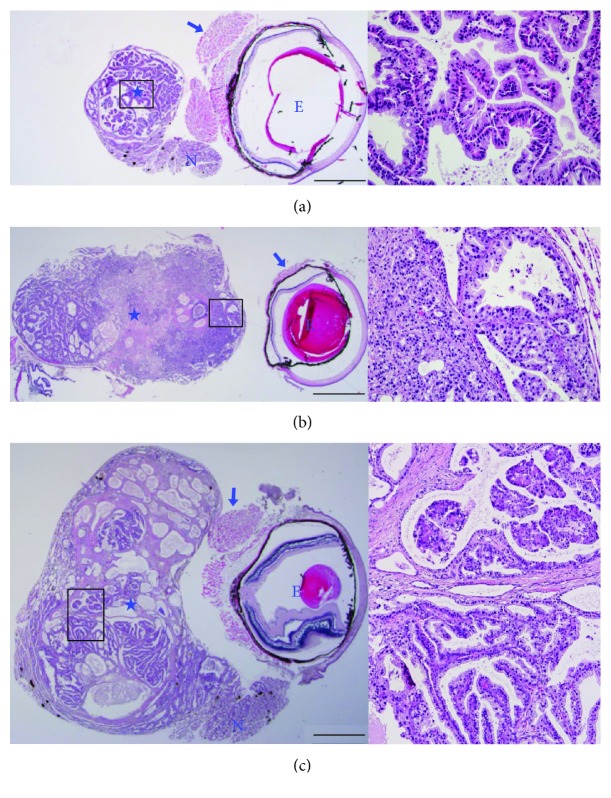

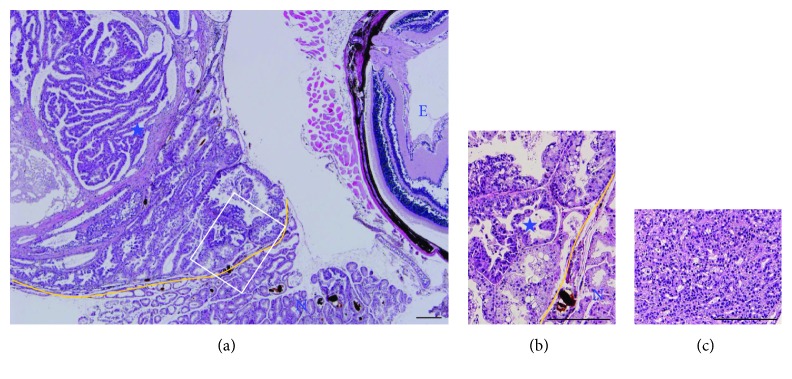

To characterize the neoplastic eye abnormalities in Brca1-mutant mice, we performed histopathological analyses of these tumor tissues. A retrobulbar mass was detected in the seven Brca1-mutant experimental animals that exhibited exophthalmoses (Figure 2). The masses showed an expansive growth pattern, and portions of nonneoplastic lacrimal gland were identified at the tumor periphery (Figures 2(a) and 2(c)). All cases were extraocular lacrimal carcinoma, characterized by variable-sized cystic spaces lined by simple or stratified cuboidal epithelium with some papillary projections. A poorly differentiated component composed of intertwining solid or near-solid tubules or stromal hyalinization was noted (Figures 2(b) and 3(c)). Acinar and ductal cells with variable vacuolated and clear features that mimicked adjacent nonneoplastic serous acinar cells of the lacrimal gland and formed solid and microcystic components were also evident (Figure 3). There was no evidence for mitosis, necrosis, pleomorphism, or neural invasion. The final pathologic diagnosis was acinic cell carcinoma arising from the lacrimal gland.

Figure 2.

Identification of lacrimal gland tumors in Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice. (a–c) Low-power view of H&E-stained sections of the 16 (a), 17 (b), and 9 (c) months of age cases of retrobulbar tumors (asterisks) separated by skeletal muscles (arrows) in the eyeballs (E). Nonneoplastic lacrimal glands (N) adjacent to the tumors are evident. The panels at the right are magnifications of the boxed areas in the adjacent panels. Scale bars: 1 mm.

Figure 3.

Histological analysis of lacrimal tumors in Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice. (a) High-power view of an H&E-stained section of the 9 months of age case (Figure 2(c)) shows acinic cell carcinoma (asterisk), characterized by variable-sized cystic spaces lined by simple or stratified cuboidal epithelium with some papillary projections. Yellow lines separate the tumor (asterisks) and nonneoplastic lacrimal gland (N). The retrobulbar tumor is separated from the eyeball (E) by the skeletal muscle. (b) Higher-magnification view of the boxed area. Variable vacuolated, clear tumor cells mimicking adjacent nonneoplastic serous acinar cells of the lacrimal gland were found. (c) A poorly differentiated, predominantly solid component with a scant glandular pattern is noted in an H&E-stained section of the 17 months of age case (Figure 2(b)). Scale bars: 200 μm.

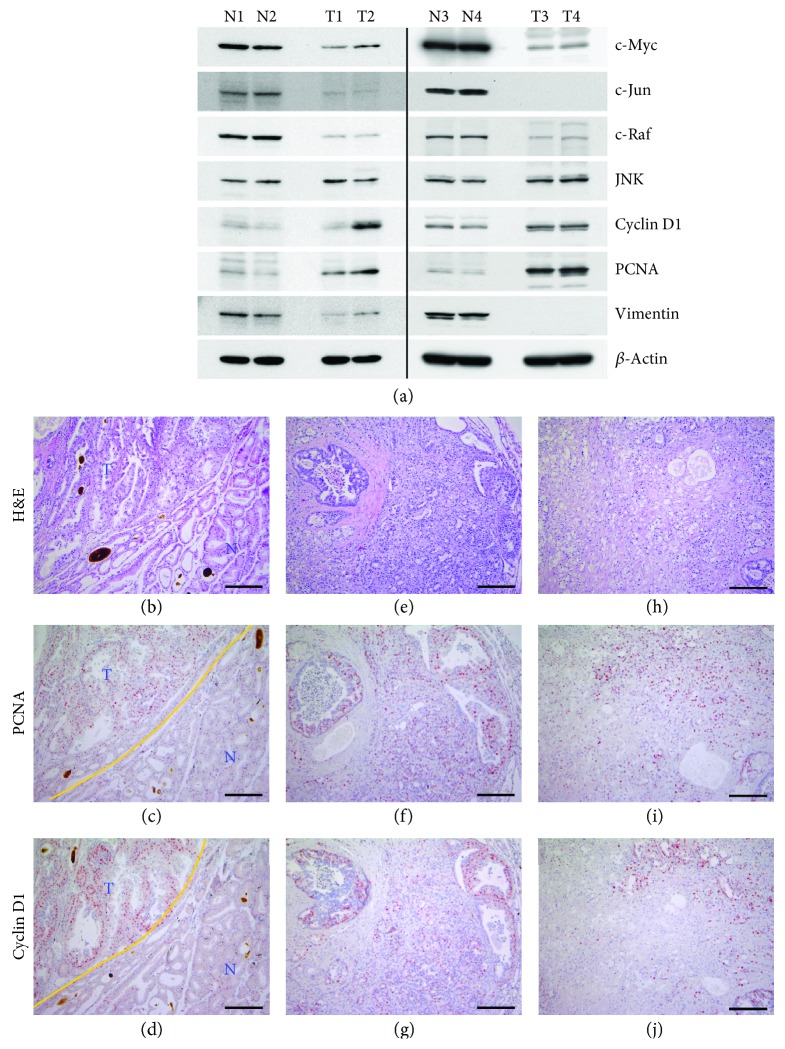

3.2. Characterization of Lacrimal Gland Tumors in Brca1-Mutant Mice

To identify the effector molecules or biomarkers involved in BRCA1-deficient lacrimal gland tumorigenesis, we analyzed various regulatory proteins in Brca1-mutant lacrimal tumors and normal lacrimal glands (Figure 4(a)). Expression of the cellular protooncogenes, c-Myc, c-Jun, and c-Raf, was decreased in tumor tissues. Notably, cyclin D1 and PCNA were induced in BRCA1-deficient tumor tissues. To further analyze the relation between PCNA and cyclin D1, we examined the distribution of PCNA- and cyclin D1-positive cells in sections of BRCA1-associated lacrimal gland tumors (Figures 4(b)–4(j)). A comparison of the distribution of these proteins in normal and neoplastic regions showed that PCNA- and cyclin D1-positive cells were abundant among acinar cells in neoplastic areas (Figures 4(c) and 4(d), upper left), whereas such cells were not detected in normal regions (Figures 4(c) and 4(d), lower right). We also identified overlapping PCNA and cyclin D1 positivity in several highly proliferative areas of lacrimal tumor sections (Figures 4(e)–4(j)), suggesting that proliferation of BRCA1-deleted lacrimal gland tumors is associated with accumulation of cyclin D1.

Figure 4.

Overexpression of cyclin D1 and increased cell proliferation in lacrimal gland tumors from Brca1-mutant mice. (a) Protein expression patterns in lacrimal gland tumors (T1 (10 M), T2 (11 M), T3 (12 M), and T4 (14 M)) from Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice compared with the normal tissue (N1, N2, N3, and N4). β-Actin was used as a loading control. (b–j) Lacrimal gland sections from tumor areas of Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice stained with H&E (b, e, h) and immunostained for PCNA (c, f, i) and cyclin D1 (d, g, j). Yellow lines in (c) and (d) separate tumor (T; upper left) and normal (N; lower right) tissue. Scale bars, 200 μm.

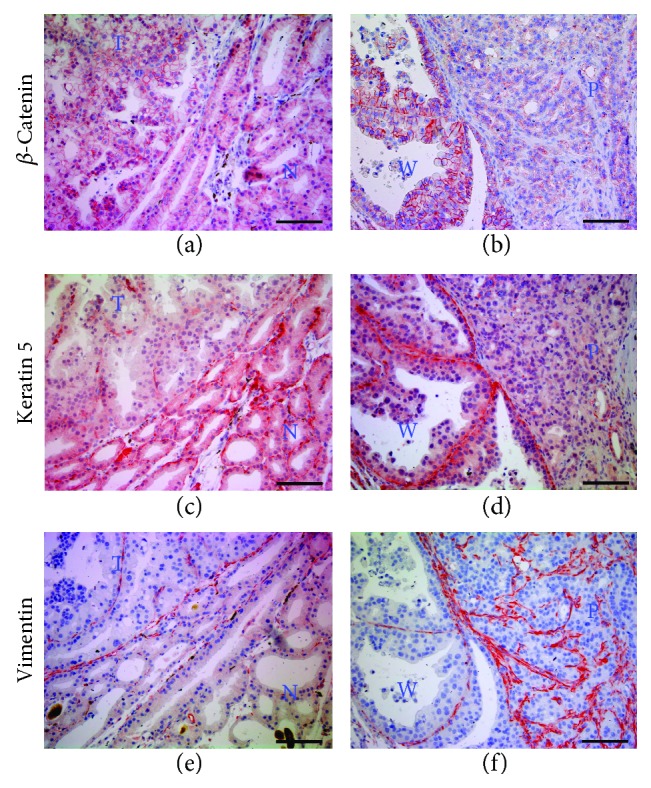

On the other hand, although specific molecular alterations that characterize acinic cell carcinoma have not yet been elucidated, activations of β-catenin and vimentin were reported in previous studies [12–14]. We also examined the distribution of cytoskeletal proteins in tumor tissues of BRCA1-associated lacrimal glands. β-Catenin, localized to the plasma membrane of acinar cells, was highly expressed in well-differentiated carcinomas (Figures 5(a), left and 5(b), left) compared with normal tissue (Figure 5(a), right) and poorly differentiated carcinomas (Figure 5(b), right). In addition, basement membrane-localized keratin 5 was highly expressed in the normal region (Figure 5(c), right), and gradually decreased as tumorigenesis progressed (Figures 5(c) and 5(d)). In contrast, distribution of vimentin is abundant in tumor (upper left) than normal region (lower right) (Figure 5(e)) and elevated in poorly differentiated (right) than well-differentiated tumor (left) (Figure 5(f)), suggesting induction of vimentin according to the aggressiveness of the BRCA1-associated lacrimal gland tumor (Figures 5(e) and 5(f)).

Figure 5.

Alteration of skeletal protein distribution in lacrimal gland tumors of Brca1-mutant mice. Distribution of β-catenin, keratin 5, and vimentin in normal (N; lower right) and tumor-containing (T; upper left) regions (a, c, e) and well-differentiated (W; lower left) and poorly differentiated (P; upper right) regions (b, d, f) of a lacrimal gland. Scale bars: 100 μm.

Taken together, these findings suggest that BRCA1-associated lacrimal gland tumors share molecular characteristics with BRCA1-deficient breast cancer and that structural proteins exhibit the alteration in level and distributions depend on the progression of cancer.

4. Discussion

Germline mutations in the BRCA1 gene are associated with an elevated risk of breast and ovarian cancer [15]. Approximately 1 in 8 women (~12.4%) will develop invasive breast cancer over the course of their lifetimes, whereas the estimated average cumulative risk for these cancers by age 70 among BRCA1 carriers is 60% [16]. However, the extent of developing other cancers in BRCA1 mutation carriers is less clear. To investigate the contribution of BRCA1 to breast cancer, mice with cre-mediated deletion of Brca1 in mammary epithelial cells (Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice) were developed and displayed the mammary tumor formation after a long latency [10]. Studies performed in the animal facility of the National Cancer Center showed that 15.5 months was required for 50% of Brca1co/coMMTV-cre mice to exhibit a mammary tumor. Using this same mouse model, we found 7 mice developed a malignant lacrimal gland tumor later in life (9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 16, and 17 months of age).

Surprisingly, although the original goal of developing MMTV-cre transgenic mice was to induce targeted deletion of Brca1 in epithelial cells of mammary glands using cre recombinase, these mice also exhibited tumors in the lacrimal gland. Indeed, previous studies have reported that activation of genes driven by the MMTV promoter results in abnormal lacrimal gland phenotypes. For example, mice with an MMTV-Notch4 transgene not only display mammary gland abnormalities but also exhibit unusual proliferation of immature epithelial cells in the lacrimal gland [17]. MMTV-vH-ras mice also frequently show lacrimal gland hyperplasia [18]. These results suggest that the MMTV promoter is also actively transcribed in the lacrimal glands.

Acinic cell carcinoma is a rare neoplasm that is nearly always observed in the salivary glands. Risk factors for acinic cell carcinoma are not yet clear but could include previous radiation exposure and familial predisposition [19]. Acinic cell carcinoma in a lacrimal gland tumor was first described by De Rosa et al. in 1986, and the few cases documented since in humans and animals have been shown to exhibit aggressive behavior in association with poor prognosis [20–25]. In the current study, the disease manifested as exophthalmos and was confirmed by radiographic examination and further histopathological and immunohistochemical analysis. Acinic cell carcinoma is a low-grade malignant tumor and further transformed to the high-grade malignancy characterized by the dedifferentiation. The high-grade transformation delineates a more aggressive behavior and is associated with a poorer prognosis than its traditional counterpart. Among the seven cases with lacrimal tumor, three cases were subjected to the histopathological analysis while others were only applied to the Western blotting for a small size of tissue sample. Our histopathological analysis revealed that all the cases of lacrimal abnormalities from Brca1-mutant mice were extraocular lacrimal malignant tumor, characterized by variable-sized cystic spaces lined by simple or stratified cuboidal epithelium with some papillary projections. Stromal hyalinization, vacuolated structures, and microcystic components were also identified in acinar cells of the lacrimal gland. Importantly, an exceedingly peculiar variant of this tumor has been described as acinic cell carcinoma with high-grade transformation/dedifferentiation which is characterized by the coexistence of both low-grade acinic cell carcinoma and a high-grade dedifferentiated component, as well as by an accelerated clinical course. In 17 months of age case, a poorly differentiated component composed of intertwining solid or near-solid tubules or stromal hyalinization was noted (Figures 2(b) and 3(c)). In addition, acinar and ductal cells with variable vacuolated and clear features that mimicked adjacent nonneoplastic serous acinar cells of the lacrimal gland and formed solid and microcystic components were also evident in the 9 months of age case (Figure 3). To provide detailed information of the malignancy, we took the representative high-magnification images of each tumor in histopathological analysis and arrange with low-power images (Figure 2). Taken together, data define the tumors arising in the lacrimal glands as acinic cell carcinoma. Our molecular characterization of BRCA1-deficient lacrimal acinic cell carcinoma using immunohistochemistry showed that proliferating acinic cells overlapped with the expression of cyclin D1, revealing a property in common with BRCA1-associated mammary tumors in mice [26]. Our immunohistochemical examination of skeletal proteins also suggested that the appearance and distribution of the immunomarkers, β-catenin, keratin 5, and vimentin, are dependent on tumor progression.

In human BRCA1 mutant carrier, breast and ovarian epithelial cell carcinomas are the predominant abnormalities in whole-body haploinsufficiency. In this study, in the cohort of conditional Brca1 knockout mice, we identified several acinic cell carcinomas in the lacrimal gland. However, there is no report of lacrimal gland tumor with alterations in BRCA1 in human. A recent study by Ripamonti et al. described the first case of acinic cell carcinoma of the breast occurring in a carrier of a BRCA1 mutation [27]. The patient, who had an invasive ductal carcinoma, had a recurrence of a triple-negative acinic cell carcinoma in the contralateral breast 4 years later. Sequencing analyses of both tumors revealed a loss of the wild-type BRCA1 allele by loss of heterozygosity in both the acinic cell carcinoma and the invasive ductal carcinoma in association with two different somatic TP53 mutations, suggesting that acinic cell carcinoma develops independent from invasive ductal carcinoma. This report also suggests that a germline mutation of BRCA1 facilitates the development of acinic cell carcinoma as well as ductal carcinoma.

5. Conclusion

For the very low incidence of lacrimal gland tumor, few large improvements have been made in its basic research and clinical investigation. In the current study, considering the low incidence of BRCA1-associated acinar cell carcinoma and lacrimal gland tumor, Brca1-mutant mice were found to be a useful model for investigating tumorigenesis of lacrimal gland tumors and preclinical study for testing treatment efficacy. In addition, our study shows that BRCA1 is involved in homeostasis and genetic stability of the lacrimal gland and provides new insight into genomic instability in organism maintenance and lacrimal gland tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Korea National Cancer Center (NCC-1610030, 1710900) and the National Research Foundation of Korea (2014R1A2A1A11049935, 2018R1A2B6001216).

Contributor Information

Sung Chul Lim, Email: sclim@chosun.ac.kr.

Sang Soo Kim, Email: sangsookim@ncc.re.kr.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions

Sun Eui Kim and Hye Jung Baek contributed equally.

References

- 1.Deng C. X. Tumor formation in Brca1 conditional mutant mice. Environmental and Molecular Mutagenesis. 2002;39(2-3):171–177. doi: 10.1002/em.10069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng C. X. BRCA1: cell cycle checkpoint, genetic instability, DNA damage response and cancer evolution. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34(5):1416–1426. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkitaraman A. R. Cancer susceptibility and the functions of BRCA1 and BRCA2. Cell. 2002;108(2):171–182. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00615-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedenson B. BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathways and the risk of cancers other than breast or ovarian. Medscape General Medicine. 2005;7:p. 60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mersch J., Jackson M. A., Park M., et al. Cancers associated with BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations other than breast and ovarian. Cancer. 2015;121(2):269–275. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Holstein S. L., Therkildsen M. H., Prause J. U., Stenman G., Siersma V. D., Heegaard S. Lacrimal gland lesions in Denmark between 1974 and 2007. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2013;91(4):349–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2012.02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shields J. A., Shields C. L., Epstein J. A., Scartozzi R., Eagle R. C., Jr. Primary epithelial malignancies of the lacrimal gland: the 2003 Ramon L. Font lecture. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;20(1):10–21. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000103003.87842.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Holstein S. L., Rasmussen P. K., Heegaard S. Tumors of the lacrimal gland. Seminars in Diagnostic Pathology. 2016;33(3):156–163. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Woo K. I., Yeom A., Esmaeli B. Management of lacrimal gland carcinoma: lessons from the literature in the past 40 years. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2016;32(1):1–10. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X., Wagner K. U., Larson D., et al. Conditional mutation of Brca1 in mammary epithelial cells results in blunted ductal morphogenesis and tumour formation. Nature Genetics. 1999;22(1):37–43. doi: 10.1038/8743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagner K. U., Wall R. J., St-Onge L., et al. Cre-mediated gene deletion in the mammary gland. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(21):4323–4330. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abraham S. C., Wu T. T., Hruban R. H., et al. Genetic and immunohistochemical analysis of pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma: frequent allelic loss on chromosome 11p and alterations in the APC/β-catenin pathway. The American Journal of Pathology. 2002;160(3):953–962. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64917-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustafsson H., Virtanen I., Thornell L. E. Expression of cytokeratins and vimentin in salivary gland carcinomas as revealed with monoclonal antibodies. Virchows Archiv A. 1988;412(6):515–524. doi: 10.1007/BF00844287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skálová A., Vanecek T., Sima R., et al. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2010;34(5):599–608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9efcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miki Y., Swensen J., Shattuck-Eidens D., et al. A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science. 1994;266(5182):66–71. doi: 10.1126/science.7545954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mavaddat N., Peock S., Frost D., et al. Cancer risks for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from prospective analysis of EMBRACE. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2013;105(11):812–822. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jhappan C., Gallahan D., Stahle C., et al. Expression of an activated Notch-related int-3 transgene interferes with cell differentiation and induces neoplastic transformation in mammary and salivary glands. Genes & Development. 1992;6(3):345–355. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dardick I., Burford-Mason A. P., Garlick D. S., Carney W. P. The pathobiology of salivary gland. II. Morphological evaluation of acinic cell carcinomas in the parotid gland of male transgenic (MMTV/v-Ha-ras) mice as a model for human tumours. Virchows Archiv A. 1992;421(2):105–113. doi: 10.1007/BF01607042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Zaher N., Obeid A., Al-Salam S., Al-Kayyali B. S. Acinic cell carcinoma of the salivary glands: a literature review. Hematology/Oncology and Stem Cell Therapy. 2009;2(1):259–264. doi: 10.1016/S1658-3876(09)50035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuzawa R., Fukuzawa K., Abe H., Nagai T., Kameyama K. Acinic cell carcinoma in an African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris) Veterinary Clinical Pathology. 2004;33(1):39–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-165X.2004.tb00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jang J., Kie J. H., Lee S. Y., et al. Acinic cell carcinoma of the lacrimal gland with intracranial extension: a case report. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;17(6):454–457. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200111000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbaum P. S., Mahadevia P. S., Goodman L. A., Kress Y. Acinic cell carcinoma of the lacrimal gland. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1995;113(6):781–785. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1995.01100060107044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fei P., Liu X., Sun Y., Zhang T., Liu L. Acinic cell carcinoma in the lacrimal gland--a case report and pathologic study. Chinese Medical Sciences Journal. 1991;6(2):110–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Rosa G., Zeppa P., Tranfa F., Bonavolonta G. Acinic cell carcinoma arising in a lacrimal gland. First case report. Cancer. 1986;57(10):1988–1991. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860515)57:10<1988::AID-CNCR2820571018>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bannister M., Lawson G. Papillary-cystic variant of acinic cell carcinoma in the lacrimal gland. Case Reports in Ophthalmological Medicine. 2014;2014:3. doi: 10.1155/2014/285485.285485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S. S., Cao L., Baek H. J., et al. Impaired skin and mammary gland development and increased γ-irradiation–induced tumorigenesis in mice carrying a mutation of S1152-ATM phosphorylation site in Brca1. Cancer Research. 2009;69(24):9291–9300. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ripamonti C. B., Colombo M., Mondini P., et al. First description of an acinic cell carcinoma of the breast in a BRCA1 mutation carrier: a case report. BMC Cancer. 2013;13(1) doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.