Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Words in scientific discourse must be truthful. Introducing ambiguity or creating a false narrative by insinuating close counts or almost statements as facts that appeal to a truth the writer wants to exist doesn't make it true. A reader's personal interpretation because of hedging or weasel words creates an opportunity for truthiness as a belief to become a fact when it isn't.

Conclusion:

Awareness by scientists of this situation will make article reading more critical and related to reality rather than what you want an author wants it to be.

Keywords: Hedging, Language, Scientific writing, Truthiness, Uncertainty

INTRODUCTION

How things are written and the words used to disseminate, convey information, and tell others matter. Writing plainly with clarity and precision matters. Research is about finding facts. Truth is a value assigned to an assertion that can be proved. A fact is a true proposition. Facts can be checked and tested. In reading articles, authors try to influence understanding using language to extend unverifiable statements and agendas or to influence thinking by suggesting a connection using “hedging” or “weasel” words. Statements can just be poorly written or say things about the subject that are unsettled and in flux. Or there is misrepresentation, misleading, lying, skewing, propaganda, an agenda, puffery, deception, ambiguity, distortion, confusion, dishonesty, pretext, or deceit. Words by themselves have definitions. The part of a statement preceding or following a specific word or group of words influences(s) meaning, and its effect defines context. The reader has a responsibility to have a heightened awareness, beware of weasel words, and to know facts from wishful thinking or to make circumstances fit a situation.

Finding facts under constraints (scientific method) reduces uncertainty. A fact remains a fact until proven otherwise. Researchers find and establish facts with reproducible evidence. How data is interpreted matters just as how things are said and not said. Fact finding evidence eliminates ignorance. How wording is used around fact statements can be used to create ambiguity or a version of the truth that is in the eye of the beholder. Science is not fantasy or a convenient attribution that makes association a cause. Science is not an exercise in justifying personal cognitive dissonance. Creating factoids or making findings equal to “close counts” does not advance science or make them facts.

Scientific writing has become littered with weasel words that hedge, cause ambiguity, introduce conjecture and inference as reliance, resulting in a travesty of intellectual honesty. “A weasel word is a modifying word that undermines or contradicts the meaning of the word, phrase, or clause it accompanies.”1 They are used to intentionally mislead or misinform. The term first appeared in a short story (“Stained Glass Political Platform”) by Chaplin in 1900, who wrote “And what may weasel words be? Why weasel words are words that suck all the life out of the words next to them, just as a weasel sucks an egg and leaves the shell. If you heft the egg afterward it's as light as a feather, and not very filling when you are hungry, but a basket full of them would make quite a show, and bamboozle the unwary”.2

Weasel words connect flimsy data to justify an opinion. This influences your thinking without you thinking unless you have a trust but verify attitude. Misdirection or slight of facts appealing to your gut or emotions is not the standard for assessing a truth teller nor is it an accurate barometer of complex scientific issues. Writers introduce vagueness with double meaning words causing ambiguity or to deliberately avoid commitment to facts.

An additional travesty added to hedging and weasel words is truthiness. This double whammy of linguistic manipulation and scientific populism of psychological irrationality is a setback for evidence, facts and truth. Truthiness is an unfortunate popular and ubiquitous fault of poor, lazy or manipulative thinking. It is an individual's personal intuition or perception accepted without regard to evidence, logic, intellectual examination or facts.3 It is self-duplicity based either in ignorance, unconscious or deliberate deception. It is wrong headedness. Using truthiness, rather than facts, in science posits wishes to be true rather than facts ruling the day. Using weasel and hedging words in scientific writing create truthiness around an unproven statement is an abhorrent practice. This is also called falseness, wishful thinking, opinion, or belief without proof. Feelings and beliefs are not facts. Everyone is entitled to their own opinion but not their own facts. How things are written or stated influences understanding. Interpretation of words is up to the reader. Truthiness is the truth you want to be not what is. Changing scientific behavior due to poor or cleverly misleading language can have consequences for you and your patients. Changing clinical behavior because of hedged words creating spurious associations due to truthiness from proven factual tenants diminishes outcomes and puts patients at increased risk.

Scientific outcomes matter, how you read and interpret scientific writing also matters. The choice of words by the author can be deliberate and innocent or manipulative, hedged and weaseled. Truthiness is philosophically related to emotivism. “Emotivism is the doctrine that all evaluative judgments are nothing but expressions of preference, expressions of attitude or feeling.”4 As scientists we must make our judgments fact-based and reasoned, not emotional. Accepting a writer's truthiness means you just don't care or you just don't get it.

Add to this mix the potency and permanence of the Internet. The Internet is a remarkable enabler of truthiness and misinformation that becomes digitally memorialized.5 Statements used in science that aren't facts insinuated as truth, replacing it with truthiness, is objectionable and dangerous. It is either scientific perversion or delusional rationalization. Science is not satire. Facts are not about intuition without regard to logic or factual evidence. Until truth and facts get back together no progress will be made. Ignorance will be advanced with disastrous outcomes for patients of readers who do not call out sloppy weak writers of truthiness or users of weasel words. Einstein said that “The greatest obstacle to discovery is not ignorance, but the illusion of knowledge.” Weasel words and truthiness in scientific writing says the gut knows better because it has the illusion of knowledge.

Poor writing is one thing, intentionally misleading is another. You, the reader, do not know the ulterior motives of the author(s). Honest scientists must be able to separate fact from fiction and not be lulled or misled into being immune to facts. Judgments are not only based on information we are considering but also the way the information is processed and organized. Our information processing can lead to biases when considering new information. Psychologically we attempt to remember bits of consistent information. The more easily these bits of information are retrieved, the more likely the new information is going to be tagged as true. This ease-of-recall is known as fluency and has wide-ranging effects. We judge fluent information (the easy just introduced statement) as more true than we realize. The ease with which we bring fluent information to mind leads to an assortment of biases in decision-making.6 This mental shorthand preferentially interprets recently read material with hedging weaselly words and truthiness statements as proven facts which they are not.

“Hedging” as a term for words used in scientific writing “whose job it is to make things more or less fuzzy” with caveats like “may,” “would,” “possible,” “could,” “might,” “suggest,” “seem,” “assume,”“indicate,” and “should” was initiated in 1972.7 The purpose of hedging is a linguistic means of indicating a lack of commitment to the truth of a proposition and as an opening for the writer to introduce alternative unproven claims to influence readers. The body of work on the use of hedges in scientific writing has been advanced since then identifying their use as the authors desire for social approval and professional recognition without expressing commitment to established facts and to create detachment from reality.8 The concept of truthiness is an unwelcome addition to hedging and weasel words introducing a preferred narrative of truth without proof.

Inferences made from statistical analysis, because they are made under constraints and limitations, are important both when they are significant and when they are not. An inference is not hypothesis. Inferences are derived from observational evidence. A hypothesis is proposed, untested, a proposal as to what is thought will be proven: it is why you test it. When the statistical inference testing is not met, the inference is not valid. It is wise to be more critical of our feelings and regard truthiness as a delusional psychosis of wishful thinking and to be avoided. A distorted narrative or creating an ideology of skewed interpretation creates and reinforces the illusion of knowledge.5 Pascal in De L'Art de Persuader said “people almost invariably arrive at their beliefs not on the basis of proof but on the basis of what they find attractive.”9

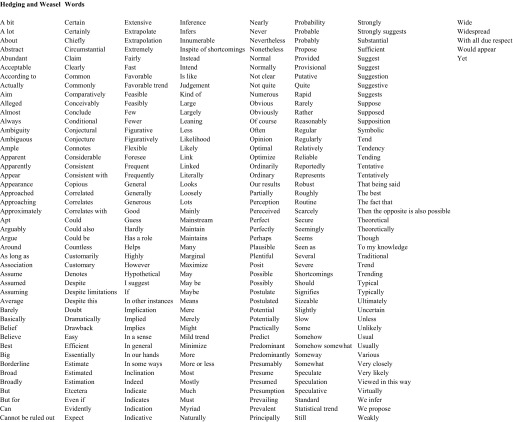

When you see these weasel or hedging words or phrases, you must be vigilant about what is being said or not said and whether or not the writing or claim(s) are on solid ground or in the quicksand of grandiose justification of hyperbole. Conditional hedging or weasel words or expressions create a façade that is imprecise, vague, unclear, uncertain, and elusive and introduces doubt, ambiguity, suspicion, uncertainty, and confusion. These misleading and evasive statements initiate a mental mechanism where the inference, insinuation, and innuendo impersonate as fact. A partial list of hedging and weasel words is presented in Appendix 1.

Examples:

Experiments in the laboratory may cause artificial …

Although the results seem to support previous findings …

This discrepancy could be attributed to …

It is possible that an increase in postoperative …

It is likely that the experimental group …

Various mechanisms might be the cause of …

The number of patients will probably increase …

Rates are generally high …

Occurrences of higher concentrations were lower at higher levels of effluent outflow.

The evidence suggests that …

Trusting truthiness coming from your gut is subscribing to something less than the truth. Hitchens's razor asserts that what can be asserted without evidence can be dismissed without evidence. Or the equivalent Latin proverb quo gratis asseritur, gratis negatur — what is freely asserted is freely dismissed. Words and expressions that are conditional, vague and undefined, introduce doubt, are imprecise, hedge and weasel, masquerading as facts. Hedging and using weasel words avoid being forthright, suggesting validity to an unproven statement or claim or an almost answer when it is actually inconclusive, vague, or outright wrong. Sentences with weasel or hedging words create their own biases and truthiness. These are mental bubbles and manipulating filter edits of writing that make scientific discourse suspect and unreliable. Caveat lector — let the reader beware.

Appendix 1.

References:

- 1. What's a Weasel Word, Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms, Richard Nordquist. https://www.thoughtco.com/weasel-word-1692604.

- 2. Lloyd H. Origin of “weasel words.” New York Times. Page 12, June 3, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- 3. http://www.dictionary.com/browse/truthiness.

- 4. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/the-truth-of-truthiness/.

- 5. Ott D. Internet dilettantes' crowd-based peer review: An exercise in mediocrity. JSLS. 2017;Oct-Dec 21(4): e2017.00069 DOI: 10.4293/JSLS.2017.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:1124–1131. DOI: 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lakoff G. Hedges: A study in meaning criteria and the logic of fuzzy concepts. Chicago Linguistic Society Papers. 1972;8:183–228. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hyland K. Boosting, hedging and the negotiation of academic knowledge. TEXT – Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse. 2009;18:349–382. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gilby E. Sublime Worlds: Early Modern French Literature, Taylor and Francis. 2006. [Google Scholar]