Abstract

Enediyne natural products are extremely potent antitumor antibiotics with a remarkable core structure consisting of two acetylenic groups conjugated to a double bond within either a 9- or 10-membered ring. Biosynthesis of this fascinating scaffold is catalyzed in part by an unusual iterative type I polyketide synthase, PKSE, that is shared among all enediyne biosynthetic pathways whose gene clusters have been sequenced to date. The PKSE is unusual in two main respects: (1) it contains an acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain with no sequence homology to any known proteins, and (2) it isself-phosphopantetheinylated by an integrated phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) domain. The unusual domain architecture and biochemistry of the PKSE hold promise both for the rapid identification of new enediyne natural products and for obtaining fundamental catalytic insights into enediyne biosynthesis. This chapter describes methods for rapid PCR-based classification of conserved enediyne biosynthetic genes, heterologous production of 9-membered PKSE proteins and isolation of the resulting polyene product, and in vitro characterization of the PKSE ACP domain.

1. INTRODUCTION

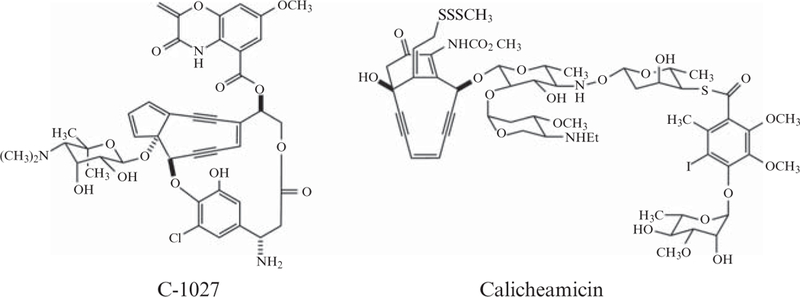

The enediyne family of natural products are among the most potent anticancer drugs ever discovered (Wang and Xie, 1999). A neocarzinostatin-polymer conjugate SMANCS® (Maeda, 2001) and calicheamicin-antibody conjugate Mylotarg® (Sievers and Linenberger, 2001) are used clinically in Japan and the United States, respectively. While their extraordinary biological activity generates interest among clinicians, the unprecedented molecular architecture of the enediynes motivates biochemical studies to decipher the biosynthetic logic of their assembly. The structurally remarkable enediyne core, or so-called “warhead,” consists of two acetylenic groups conjugated to a double bond within either a 9- or 10-membered ring exemplified by C-1027 and calicheamicin, respectively (Fig. 5.1). Cytotoxicity arises from environmentally triggered cyclization of the enediyne core to yield a benzenoid diradical capable of abstracting hydrogen from DNA (Galm et al., 2005). Although elucidation of the biosynthetic pathways for the peripheral moieties has progressed rapidly in recent years, little is known about the assembly of the enediyne core itself, and fascinating enzymology surely awaits discovery (Van Lanen and Shen, 2008). Such detailed biochemical knowledge is required to generate improved enediyne analogues via rational manipulation of the biosynthetic machinery (Kennedy et al., 2007a,b).

Figure 5.1.

Structures of representative members of the 9-membered (C-1027) and 10-membered (calicheamicin) enediyne natural products.

A de novo biosynthetic pathway involving a dedicated polyketide synthase (PKS) has only recently been shown to be responsible for production of the enediyne core. Although early studies employing isotope-labeling experiments established acetate as a precursor (Hensens et al., 1989; Lam et al., 1993; Tokiwa et al., 1992), these experiments could not distinguish whether the enediyne core originated from a dedicated PKS or from the degradation of a fatty acid precursor. However, five enediyne biosynthetic gene clusters—those for C-1027 (Liu et al., 2002), neocarzinostatin (Liu et al., 2005), maduropeptin (Van Lanen et al., 2007), calicheamicin (Ahlert et al., 2002), and dynemicin (Gao and Thorson, 2008)—have now been sequenced and each has been shown to possess a unique iterative type I PKS (PKSE) sharing significant sequence homology and domain architecture. The essential role of the PKSE was established when C-1027 production was abolished by disruption of the sgcE gene (i.e., the pksE gene from the C-1027 cluster) and restored upon complementation of the △sgcE mutation by expressing a functional copy of sgcE in trans (Liu et al., 2002). Similar results were obtained using the PKSE from the neocarzinostatin cluster, NcsE (Liu et al., 2005), and the maduropeptin cluster, MdpE (Van Lanen et al., 2007). Together, these results definitively establish the polyketide origin of the enediyne core.

The unique, enediyne-specific pksE gene cassettes may be exploited to identify new enediyne biosynthetic gene clusters. Indeed, a universal PCR-based method has been developed whereby degenerate primers from conserved PKSE regions are used to rapidly amplify and clone additional pksE genes (Liu et al., 2003). Sequencing and phylogenetic analysis of the resulting minimal enediyne cassettes has revealed a clear genotypic distinction between 9- and 10-member-specific PKSEs. This distinction significantly aids prediction of unknown enediyne core structures directly from the pksE gene sequence. Thus, rapid PCR-based enediyne genotyping of new enediyne-producing isolates may direct the discovery of new members of the enediyne family of natural products.

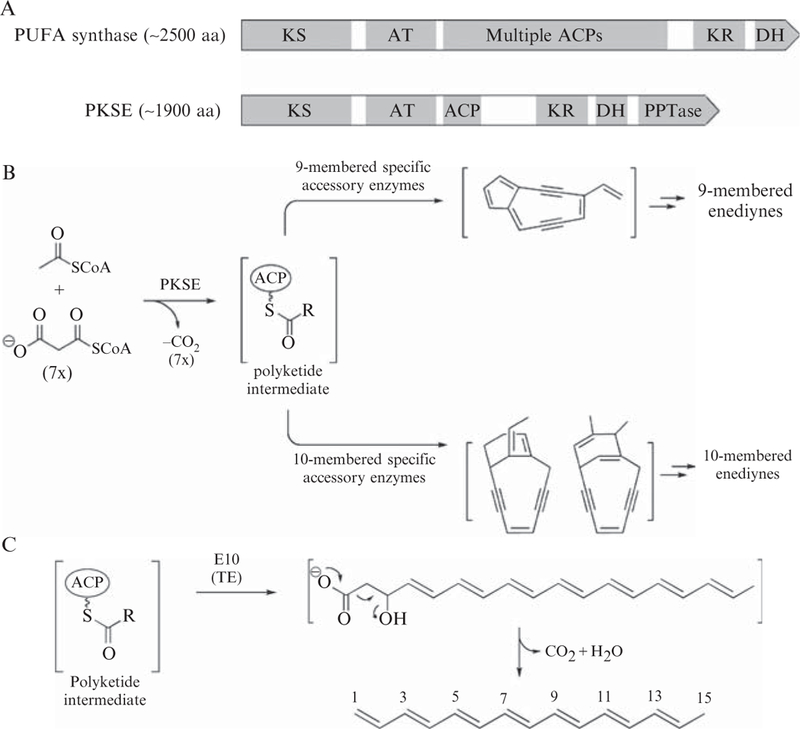

The availability of multiple pksE sequences has enabled bioinformatics analysis, which unambiguously identified four domains: a ketosynthase (KS), acyltransferase (AT), ketoreductase (KR), and dehydratase (DH). In both domain organization and sequence homology, PKSEs are most closely related to the polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) synthases involved in the biosynthesis of docosahexaenoic acid in Moritella marina and eicosapentaenoic acid in Shewanella japonica (Jiang et al., 2008; Metz et al., 2001) (Fig. 5.2A). (See Chapter 4 in this volume.) However, two unusual features distinguish the PKSEs as an unusual PKS family unique to enediyne bio-synthesis. First, a region between the AT and KR domains was proposed to be an acyl carrier protein (ACP) based on identical architecture to the PUFA synthases (Fig. 5.2A), even though this region has no homology to any known proteins. Second, the C-terminal region was predicted to be a phosphopantetheinyl transferase (PPTase) capable of loading the phosphopantetheine (Ppant) cofactor onto the ACP (Zazopoulos et al., 2003). In contrast to typical ACP loading by a discrete PPTase, such self-phosphopantetheinylation is extremely rare (Fichtlscherer et al., 2000; Weissman et al., 2004). The above-described in vivo complementation system was used to demonstrate that Ser974Ala and Asp1827Ala variants of SgcE failed to restore C-1027 production in the △sgcE mutant (Zhang et al., 2008), consistent with the proposed roles of Ser974 as a site for Ppant modification on the ACP and Asp1827 as a PPTase catalytic residue.

Figure 5.2.

PKSE domain organization and role in enediyne core biosynthesis. (A) Domain organization of PKSE is similar to that of the PUFA synthases. (B) Enediyne core biosynthesis carried out by PKSE and accessory enzymes is responsible for divergence of the polyketide intermediate into either 9- or 10-membered enediyne families of natural products. (C) Structure of the polyene product 1,3,5,7,9,11,13-pentadecaheptanene isolated upon coexpression of 9-membered pksE and pksE10 exemplified by sgcE/sgcE10 and ncsE/ncsE10.

Although rapid genotyping and in vivo complementation revealed a domain architecture that is unique to the PKSEs, in vitro functional characterization is required to unambiguously identify the ACP and PPTase domains. Recent methods have been developed to biochemically characterize PKSEs, providing fascinating insights into their function (Zhang et al., 2008). For instance, the development of a heterologous expression system for 9-membered PKSEs led to the isolation of a polyene compound as the first isolable intermediate en route to enediyne core biosynthesis (Fig. 5.2B and C), and this intermediate could not be isolated from the aforementioned Ser974-Ala or Asp1827Ala mutants of the ACP or PPTase, respectively. The roles of the ACP and PPTase domains were then confirmed by two crucial in vitro biochemical experiments employing both the wildtype SgcE and the respective Ser974Ala and Asp1827Ala site-directed mutants. First, peptide mapping of SgcE by Fourier-transform mass spectrometry clearly identified a +340 amu mass shift associated with Ser974 of the ACP domain. Consistent with Ppant modification, the mass shift disappeared upon mutation of either the Ser974 of the ACP or the Asp1827 of the PPTase. Second, phosphopantetheinylation was definitively demonstrated by incubation of the ACP domain with the exogenous PPTase Svp (Sanchez et al., 2001). The conversion of apo-ACP to holo-ACP could be monitored by HPLC, and the substrate and product of this reaction could be isolated and identified by mass spectrometry. Moreover, the PPTase from the calicheamicin pathway was expressed and in vitro phosphopantetheinylation of several carrier proteins was demonstrated (Murugan and Liang, 2008). Together, these results establish PKSE as an iterative type I PKS of unusual domain architecture that self-phosphopantetheinylates a novel ACP domain.

This chapter describes the protocols for identification and characterization of the iterative type I PKS for enediyne core biosynthesis (PKSEs): (1) PCR amplification of pksE cassettes for predictive classification of new enediynes; (2) heterologous expression and purification of 9-membered-specific PKSE proteins in Escherichia coli; (3) production and isolation of the polyene intermediate produced by the 9-membered PKSEs; (4) heterologous expression and purification of 9-membered-specific ACP domains; and (5) their in vitro phosphopantetheinylation.

2. METHODS

2.1. PCR amplification of PKSE cassettes for predictive classification of new enediynes

2.1.1. Primer design

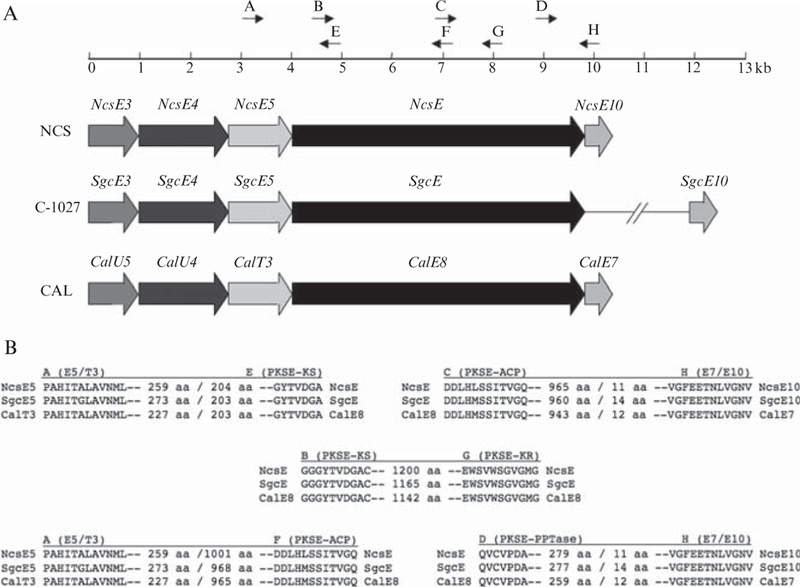

Conserved regions of shared genes involved in enediyne core biosynthesis (including the PKSE) from the loci for C-1027, neocarzinostatin, and calicheamicin were used to construct degenerate primers (Fig. 5.3 and Table 5.1) (Liu et al., 2003). Primer pairs A–E and A–F, respectively, amplify ~1.4- and 3.8-kb fragments of the N-terminal PKSE gene, whereas primer pairs C-H and D-H respectively amplify ~2.9- and 0.9-kb fragments of the C-terminal region. The B–G primer pair is designed to generate a PCR product that overlaps the products of the A–F and C–H primer pairs.

Figure 5.3.

Degenerate primer design for PCR-based amplification of PKSE fragments. (A) Location of primers in relation to the pksE and associated genes that together constitute a minimal pksE and cassette from the neocarzinostatin (NCS), C-1027, and calicheamicin (CAL) biosynthetic clusters. (B) The conserved amino acid motifs used to design degenerate primers A to H. Numbers between motifs represent amino acid distance, and the noncoding regions between open reading frames (<10 nt) are denoted by a slash.

Table 5.1.

Primers used for PCR Amplification of the pksE Genes

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| Forward | |

| A | 5′-CCCCGCVCACATCACSGSCCTCGCSGTGAACATGCT-3′ |

| B | 5′-GGCGGCGGVTACACSGTSGACGGMGCCTGC-3′ |

| C | 5′-GACGAYCTGCACMTGAGCTCSATCACCGTCGGCCAG-3′ |

| D | 5′-CARGTGTGCGTSCCSGACGCS-3′ |

| Reverse | |

| E | 5′-GCAGGCKCCGTCSACSGTGTABCCGCCGCC-3′ |

| F | 5′-CTGGCCGACGGTGATSGAGCTCAKGTGCAGRTCGTC-3′ |

| G | 5′-CCCATSCCGACSCCGGACCASACSGACCAYTCCA-3′ |

| H | 5′-ACGTTGCCGACSAGRTTSGTYTCCTCGAACCGAC-3′ |

IUB codes for mixed base sites: M = A or C; R = A or G; S = C or G; Y = C or T; K = G or T; V = A, C, or G; B = C, G, or T.

Generation of PCR products

Prepare genomic DNA from an enediyne-producing organism following a standard literature protocol. For example, a genomic DNA preparation may be readily prepared from gram-positive bacteria (Pospiech and Neumann, 1995).

Prepare a 50-μl PCR reaction mixture containing 1. μl diluted template DNA, 1X reaction buffer, 5% DMSO, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM of each primer, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, and 1 unit of Taq polymerase.

Place the PCR reaction in a thermocycler and initiate the following program: (a) 94° (5 min); (b) [94° (45 s), 60–65° (1.5 min), 72° (2 to 5 min)] × 30 cycles; (c) 72° (7 min); and (d) hold at 4°.

Purification, subcloning, and sequencing of PCR products may be done following standard procedures.

2.1.2. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis

Assemble the sequences of overlapped PCR fragments from at least five independent clones into contiguous regions using a standard software package, and identify probable open reading frames.

Compare the deduced protein sequences with other known proteins in the databases using available BLAST methods, and perform phylogenetic analysis using standard methods such as CLUSTALW and DRAW-TREE (http://workbench.sdsc.edu).

2.2. Heterologous expression and overproduction of PKSE proteins

2.2.1. Generation of an E. coli expression construct for pksE

Prepare PCR primers suitable for amplification of the pksE gene and subsequent ligation-independent cloning as described by Novagen (Madison, WI).

Prepare a PCR reaction using the Expand Long Template PCR System from Roche (Indianapolis, IN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A typical PCR reaction includes 10- to 100-ng pksE-containing template DNA, 1X supplied buffer, 300 nM of each primer, 350 μM of each dNTP, 5% DMSO, and 2.5 U DNA polymerase per 50-μl reaction.

Initiate the following PCR program: (a) 94° (5 min); (b) [94° (10 s), 56° (30 s), 68° (40 s per kb of desired product)] × 30 cycles; (c) 68° (7 min); and (d) hold at 4°.

Purify the PCR product as an electrophoretically resolved band from a 0.8 to 1% agarose gel using a standard procedure such as the QIAQuick gel purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Generate the expression construct by inserting the gel-purified PCR product into the pET-30 Xa/LIC vector by ligation-independent cloning as described by Novagen (Madison, WI), and sequence to confirm the fidelity of the PCR reaction.

2.2.2. Expression, overproduction, and purification of His6-tagged PKSE

Introduce the above pksE-containing pET-30 Xa/LIC expression construct into E. coli BL21(DE3) by transformation, and plate on LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin.

Pick a single colony from the plate, inoculate 3 ml of LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and incubate at 37° for 12 h.

Transfer a 0.5-ml aliquot to 50 ml of LB medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin, grow for an additional 12 h at 37° and shake at 250 rpm.

Transfer 5 ml of the above culture to 500 ml of LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and incubate at 18° and 250 rpm.

When the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reaches ~0.5 (after approximately 10 h), induce PKSE expression by adding 0.1 mM of isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), and incubate the cells at 18° for a further 15 h with shaking at 250 rpm.

Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 4° and 9200×g for 15 min.

On ice, use a pipette to resuspend the cell pellet in ~15 ml of buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0), and add the recommended amount of Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), ~1 mg lysozyme, and ~1 mg DNase I.

Lyse the cells by sonication on ice (10 s sonication per minute, repeated six times), then centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 1 h at 4° in a Beckman J2-HS centrifuge equipped with a JA-25.50 rotor (Beckman, Fullerton, CA). Collect the supernatant, which should be noticeably yellow, and store on ice.

Add ~2 ml of Ni-NTA agarose slurry (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) to the supernatant and gently shake on ice for 1 h in order to allow the His6-tagged PKSE protein to bind to the Ni-NTA agarose.

Load the Ni-NTA agarose-containing solution onto a column and allow the liquid to drain away. Wash the Ni-NTA agarose with ~30 ml of the above buffer supplemented with 10 mM imidazole.

Elute the His6-tagged PKSE protein with buffer containing 200 mM imidazole. Pool together the yellow PSKE-containing fractions and concentrate to <1 ml using a Vivaspin 50,000 MWCO ultrafiltration centrifugal device (Sartorius, Edgewood, NY).

The concentrated PKSE protein is then exchanged into a different buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, 0.5 mM DTT, pH 8.0) using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

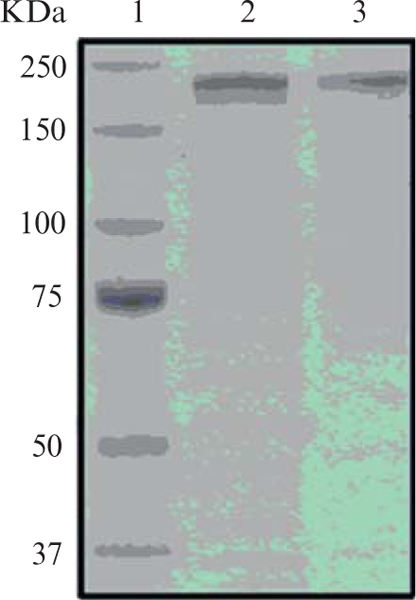

The purity of the PKSE protein may be assessed by 8% acrylamide SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5.4), and the His6-tagged PKSE proteins may be used without further modification.

Figure 5.4.

SDS-PAGE gel (8%) showing the molecular weight marker (lane 1) and PKSEs exemplified by NcsE (lane 2) and SgcE (lane 3). The PKSEs migrate at the expected molecular weight of ~208 kDa.

2.3. Production and isolation of the polyene intermediate from 9-membered PKSEs

A polyene product, 1,3,5,7,9,11,13-pentadecaheptaene, has been identified as the first isolable intermediate produced by the PKSE en route to formation of the 9-membered enediyne core. Production of the polyene intermediate can be accomplished by heterologous expression of the PKSE in E. coli or Streptomyces to yield a covalent PKSE-polyene complex. The polyene may be released from the PKSE by coexpression of pksE10 from the same pathway, which encodes a thioesterase.

2.3.1. Generation of an E. coli expression construct for pksE10

Design primers to PCR-amplify the thioesterase gene, pksE10, using the primer sequence extensions required for subsequent cloning into pCDF-2 Ek/LIC using ligation-independent cloning (Novagen, Madison, WI).

Perform the PCR reaction using the Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Although PCR parameters will have to be optimized for each different pksE10 target amplicon, a typical 50 μl reaction contains 1X supplied buffer, 600 nM of each primer, 2.5 mM each dNTP, 1 mM MgSO4, 5% DMSO, and 2.5 U DNA polymerase, and the following thermocycling program: (a) 96° (2 min); (b) [96° (10 s), 56° (30 s), 68° (20 s)] × 30 cycles; (c) 68° (7 min); and (4) hold at 4°.

Purify the PCR product as an electrophoretically resolved band from a 1% agarose gel using a standard procedure such as the QIAQuick gel purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA).

Generate the expression construct by inserting the gel-purified PCR product into the pCDF-2 Ek/LIC vector by ligation-independent cloning as described by Novagen (Madison, WI), and sequence to confirm the fidelity of the PCR reaction.

2.3.2. Coexpression of pksE and pksE10 in E. coli to yield the free polyene product

Introduce the above pksE10-containing pCDF-2 Ek/LIC expression construct by transformation into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells already harboring the pksE-containing pET-30 Xa/LIC expression construct, and plate on LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin.

Pick a single colony from the plate and inoculate 3 ml of LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin and incubate at 37° for 12 h.

Transfer a 0.5-ml aliquot to 50 ml of LB medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin, grow for an additional 12 h at 37° and shake at 250 rpm.

Transfer 5 ml of the above culture to 500 ml of LB medium supplemented with 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin and incubate at 18° and 250 rpm.

When the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reaches ~0.5 (after approximately 10 h), induce PKSE expression by adding 0.1 mM of IPTG, and incubate the cells at 18° for a further 36 h with shaking at 250 rpm.

Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 4° and 9200×g for 15 min.

2.3.3. Isolation of the polyene product

Resuspend the cell pellet in water to a density of ~200 mg/ml, add 1 mg/ml lysozyme and incubate at room temperature for 30 min.

Complete cell lysis by sonication to homogeneity, then centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 1 h at 4° in a Beckman J2-HS centrifuge equipped with a JA-25.50 rotor (Beckman, Fullerton, CA). Discard the supernatant.

Wash the cell debris with 100 mM sodium acetate, pH 6.0, and centrifuge as in Step 2 but for only 15 min.

Wash the cell debris with ethanol, and repeat centrifugation as in Step 3.

Extract cell debris with ethyl acetate (1:100 wt/vol) and evaporate to dryness under reduced pressure.

Dissolve the dried sample in a minimal volume of chloroform and load on a polyamide 6 column (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) equilibrated with chloroform. Elute the sample from the column with chloroform, and concentrate the polyene-containing fraction.

Purify the concentrated sample by silica gel column chromatography eluted with hexane/chloroform (9:1), and concentrate the polyene-containing fraction.

Purify the polyene further using a semipreparative C18 HPLC column (Apollo, 250 × 10 mm, 5 mm; Grace Davison, Deerfield, IL), and evaporate the appropriate fraction to dryness under reduced pressure. The resulting purified polyene product should be visible as a yellow powder.

2.4. Production of apo-ACPs from PKSE for in vitro functional analyses

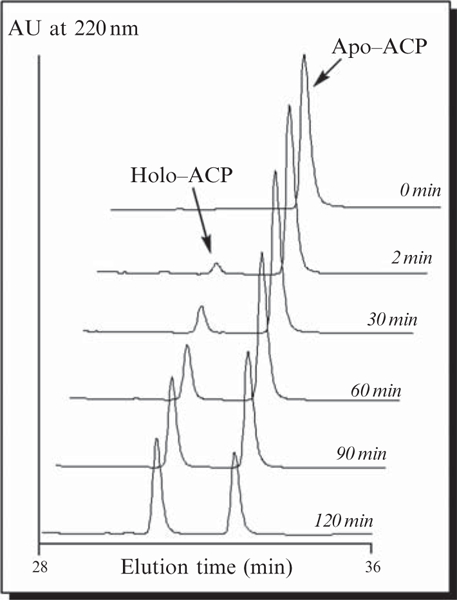

To definitively establish the identity of the unique ACP domain of the PKSE proteins, in vitro experiments are required. First, several versions of the ACP should be prepared, because the exact boundaries of the ACP domain are not clearly discernable from the sequence data. Second, the ACPs must be heterologously expressed and purified as nonphosphopantetheinylated proteins, or apo-ACPs, which may then be phosphopantetheinylated in vitro using a promiscuous PPTase such as Svp (Sanchez et al., 2001). Phosphopantetheinylation, or generation of holo-ACPs, is often detected by a shift in retention time in an HPLC chromatogram, and the identity confirmed by mass spectrometry. Moreover, the inability of mutant apo-ACPs to be phosphopantetheinylated can be used to identify the amino acid residue that is modified by the PPTase.

2.4.1. Overexpression in E. coli and production and purification of apo-ACPs

Use standard techniques to prepare several plasmid constructs for the expression of the pksE-ACP domain as His6-tagged ACP proteins in pRSF-2 Ek/LIC using ligation-independent cloning as described by Novagen (Madison, WI).

Introduce the above pksE-ACP-containing pRSF-2 Ek/LIC expression constructs into E. coli BL21(DE3) by transformation, and plate on LB medium supplemented with 150 μg/ml kanamycin.

Pick a single colony from the plate, inoculate 3 ml of LB medium supplemented with 150 μg/ml kanamycin and incubate at 37° for 12 h.

Transfer a 0.5 ml aliquot to 50 ml of LB medium containing 150 μg/ml kanamycin, grow for an additional 12 h at 37° and shake at 250 rpm.

Transfer 5 ml of the above culture to 500 ml of LB medium supplemented with 150 μg/ml kanamycin and incubate at 18° and 250 rpm.

When the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) reaches ~0.5 (after approximately 10 h), induce His6-ACP expression by adding 0.1 mM of IPTG, and incubate the cells at 18° for a further 15 h with shaking at 250 rpm.

Pellet the cells by centrifugation at 4° and 9200×g for 15 min.

On ice, use a pipette to resuspend the cell pellet in ~15 ml of buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, pH 8.0), and add the recommended amount of Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), ~1 mg lysozyme, and ~1 mg DNase I.

Lyse the cells by sonication on ice (10 s sonication per minute, repeated six times), then centrifuge at 15,000 rpm for 1 h at 4° in a Beckman J2-HS centrifuge equipped with a JA-25.50 rotor (Beckman, Fullerton, CA). Collect the supernatant and store on ice.

Add ~2 ml of Ni-NTA agarose slurry (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) to the supernatant and gently shake on ice for 1 h in order to allow the His6-tagged ACP protein to bind to the Ni-NTA agarose.

Load the Ni-NTA agarose-containing solution onto a column and allow the liquid to drain away. Wash the Ni-NTA agarose with ~30 ml of the above buffer supplemented with 20 mM imidazole.

Elute the His6-tagged ACP proteins with buffer containing 200 mM imidazole. Pool together the ACP-containing fractions and concentrate to less than 1 ml using a Vivaspin 5000 MWCO ultrafiltration centrifugal device (Sartorius, Edgewood, NY).

The concentrated ACP proteins are then exchanged into a different buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, 0.5 mM DTT, pH 8.0) using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ).

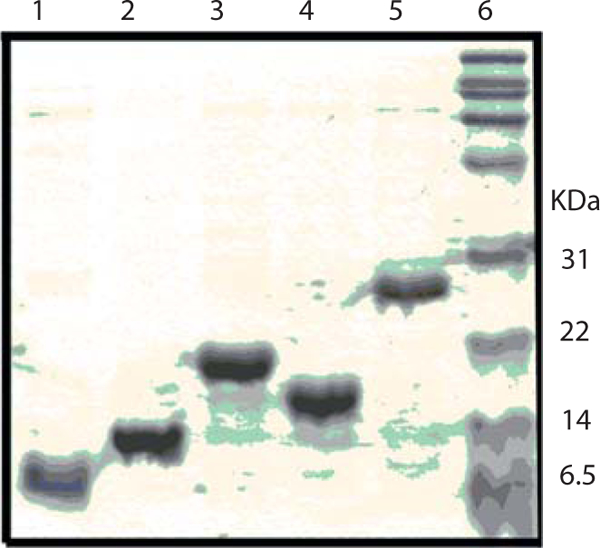

Protein purity can be assessed by 13.5% acrylamide SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5.5), and the His6-tagged ACP proteins are analyzed by mass spectrometry to ensure proper molecular weight, and then may be used without further modification.

Figure 5.5.

SDS-PAGE gel (13.5%) of His6-tagged ACP constructs: ACP81 (lane 1), ACP108 (lane 2), ACP136 (lane 3), ACP109 (lane 4), ACP212 (lane 5), and molecular weight marker (lane 6).

2.5. In vitro preparation of holo-ACPs

Prepare a small-scale phosphopantetheinylation reaction (50 to 100 μL) in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube with the following composition: 50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 0.2 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA), 5 mM coenzyme A (CoA), 0.05 mM apo-ACP, and ~10 μM PPTase such as Svp.

Incubate the reaction at 30°.

At various time points after initiating the reaction (such as 30, 60, 90,120 min, etc.), remove an aliquot, quench the reaction with an equal volume of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid in 10% acetonitrile (Solvent A), and centrifuge in a bench-top microcentrifuge at maximum speed to remove insoluble material.

Analyze the sample by HPLC with a Jupiter C4 300-Å column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex, La Jolla, CA) operated at a flow rate of 1 ml/min, monitoring absorbance at 220 nm. Elute the sample by the following series of linear gradients from solvent A to solvent B (0.1% trichloroacetic acid in 90% acetonitrile): (1) 0 to 5 min, 5% B; (2) 5 to 32 min, gradient from 5 to 95% B; (3) 32–40 min, hold at 95% B; and (4) 40 to 45 min, gradient from 95 to 5% B.

The conversion of apo- to holo-ACPs should be apparent by the appearance of a new peak with a shorter retention time (Fig. 5.6). Collect individual protein peaks, lyophilize to remove solvent, and analyze by mass spectrometry to confirm identities.

Figure 5.6.

Time-course analysis showing the in vitro 4′-phosphopantetheinylation of the apo-ACP81 domain of SgcE catalyzed by the Svp PPTase to generate holo-ACP.

3. CONCLUSION

The methods described have been used to successfully characterize the enediyne-specific iterative type I polyketide synthase (PKSE). The unique sequence and domain architecture of the PKSE has enabled a PCR-based screening method capable of rapidly identifying and classifying unknown PKSEs specific for either 9- or 10-membered enediyne cores. The ability to classify enediyne cores from sequence provides an exciting opportunity to focus discovery efforts on specific natural product drug leads. The heterologous expression of 9-membered PKSEs represents a highly significant step towards obtaining a detailed understanding of PKSE function, and has enabled the development of an additional method for isolation and identification of a new polyene compound as the first characterized biosynthetic intermediate en route to construction of the 9-membered enediyne core. Together with in vivo complementation and Fourier-transform mass spectrometry experiments not described in this chapter, results from the polyene isolation experiments helped to identify the unprecedented ACP and PPTase domains, as mutations in these PKSE domains abolished polyene production. Finally, methods used to overproduce, purify and carry out in vitro phosphopantetheinylation of PKSE ACP domains have enabled definitive functional assignment of this domain, as previous bioinformatics analyses revealed no homology to any known proteins. In summary, these methods were fundamental in enabling identification of the PKSE as an unusual self-phospopanthetheinylating PKS with a novel ACP domain, and lay the foundation for future discovery of new enediyne natural products and for the elucidation and engineering of 9- versus 10-membered PKSE selectivity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported in part by National Institute of Health (NIH) grants CA78747 and CA113297. G.P.H. is the recipient of an Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (Canada) (NSERC) postdoctoral fellowship, and S.V.L. is the recipient of an NIH postdoctoral fellowship (CA1059845).

REFERENCES

- Ahlert J, Shepard E, Lomovskaya N, Zazopoulos E, Staffa A, Bachmann BO, Huang K, Fonstein L, Czisny A, Whitwam RE, Farnet CM, and Thorson JS (2002). The calicheamicin gene cluster and its iterative type I enediyne PKS. Science 297, 1173–1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtlscherer F, Wellein C, Mittag M, and Schweizer E (2000). A novel function of yeast fatty acid synthase—Subunit alpha is capable of self-pantetheinylation. Eur. J. Biochem. 267, 2666–2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galm U, Hager MH, Van Lanen SG, Ju JH, Thorson JS, and Shen B (2005). Antitumor antibiotics: Bleomycin, enediynes, and mitomycin. Chem. Rev. 105, 739–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, and Thorson JS (2008). The biosynthetic genes encoding for the production of the dynemicin enediyne core in Micromonospora chersina ATCC53710. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 282, 105–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensens OD, Giner JL, and Goldberg IH (1989). Biosynthesis ofNCS chrom A, the chromophore of the antitumor antibiotic neocarzinostatin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 3295–3299. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Zirkle R, Metz JG, Braun L, Richter L, Van Lanen SG, and Shen B (2008). The role of tandem acyl carrier protein domains in polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 6336–6337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DR, Gawron LS, Ju JH, Liu W, Shen B, and Beerman TA (2007a). Single chemical modifications of the C-1027 enediyne core, a radiomimetic antitumor drug, affect both drug potency and the role of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated in cellular responses to DNA double-strand breaks. Cancer Res. 67, 773–781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DR, Ju J, Shen B, and Beerman TA (2007b). Designer enediynes generate DNA breaks, interstrand cross-links, or both, with concomitant changes in the regulation of DNA damage responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 17632–17637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam KS, Veitch JA, Golik J, Krishnan B, Klohr SE, Volk KJ, Forenza S, and Doyle TW (1993). Biosynthesis of esperamicin A1, an enediyne antitumor antibiotic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115, 12340–12345. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Ahlert J, Gao QJ, Wendt-Pienkowski E, Shen B, and Thorson JS (2003). Rapid PCR amplification of minimal enediyne polyketide synthase cassettes leads to a predictive familial classification model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 11959–11963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Christenson SD, Standage S, and Shen B (2002). Biosynthesis of the enediyne antitumor antibiotic C-1027. Science 297, 1170–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W, Nonaka K, Nie LP, Zhang J, Christenson SD, Bae J, Van Lanen SG, Zazopoulos E, Farnet CM, Yang CF, and Shen B (2005). The neocarzinostatin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces carzinostaticus ATCC 15944 involving two iterative type I polyketide synthases. Chem. Biol. 12, 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda H (2001). SMANCS and polymer-conjugated macromolecular drugs: Advantages in cancer chemotherapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 46, 169–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz JG, Roessler P, Facciotti D, Levering C, Dittrich F, Lassner M, Valentine R, Lardizabal K, Domergue F, Yamada A, Yazawa K, Knauf V, et al. (2001). Production of polyunsaturated fatty acids by polyketide synthases in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Science 293, 290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan E, and Liang ZX (2008). Evidence for a novel phosphopantetheinyl transferase domain in the polyketide synthase for enediyne biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 582, 1097–1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pospiech A, and Neumann B (1995). A versatile quick-prep of genomic DNA from gram-positive bacteria. Trends Genet. 11, 217–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez C, Du LC, Edwards DJ, Toney MD, and Shen B (2001). Cloning and characterization of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase from Streptomyces verticillus ATCC15003, the producer of the hybrid peptide-polyketide antitumor drug bleomycin. Chem. Biol. 8, 725–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sievers EL, and Linenberger M (2001). Mylotarg: Antibody-targeted chemotherapy comes of age. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 13, 522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokiwa Y, Miyoshisaitoh M, Kobayashi H, Sunaga R, Konishi M, Oki T, and Iwasaki S (1992). Biosynthesis of dynemicin A, a 3-Ene-1,5-diyne antitumor antibiotic. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 4107–4110. [Google Scholar]

- Van Lanen SG, Oh TJ, Liu W, Wendt-Pienkowski E, and Shen B (2007). Characterization of the maduropeptin biosynthetic gene cluster from Actinomadura madurae ATCC 39144 supporting a unifying paradigm for enediyne biosynthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 13082–13094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Lanen SG, and Shen B (2008). Biosynthesis of enediyne antitumor antibiotics. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 8, 448–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XW, and Xie H (1999). C-1027. Antineoplastic antibiotic. Drugs Future 24, 847–852. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman KJ, Hong H, Oliynyk M, Siskos AP, and Leadlay PF (2004). Identification of a phosphopantetheinyl transferase for erythromycin biosynthesis in Saccharopolyspora erythraea. ChemBioChem 5, 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazopoulos E, Huang KX, Staffa A, Liu W, Bachmann BO, Nonaka K, Ahlert J, Thorson JS, Shen B, and Farnet CM (2003). A genomics-guided approach for discovering and expressing cryptic metabolic pathways. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 187–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Van Lanen SG, Ju JH, Liu W, Dorrestein PC, Li WL, Kelleher NL, and Shen B (2008). A phosphopantetheinylating polyketide synthase producing a linear polyene to initiate enediyne antitumor antibiotic biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 1460–1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]