Abstract

Background:

E-cigarette use rates are high among youth, but there is limited information on the types of e-cigarette devices that are used by youth.

Methods:

During Spring 2017, students from 4 high schools completed surveys on use of e-cigarette devices (cig-a-like, vape/hookah pen, modified devices or mods, and JUUL). Among youth who endorsed ever (lifetime) use of an e-cigarette and of at least one device (n=875), we assessed 1) prevalence rates of ever and current (past-month) use of each device, 2) use of nicotine in each device, and 3) predictors [age, sex, race, socioeconomic status (SES), other tobacco use] of ever use of each device and of use of single versus multiple devices.

Results:

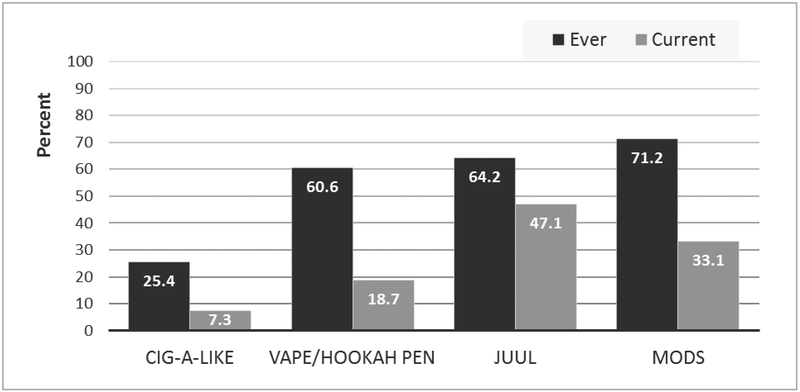

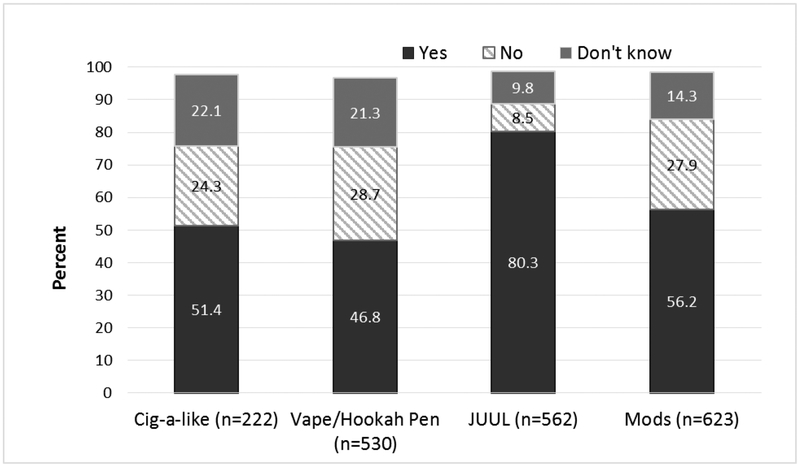

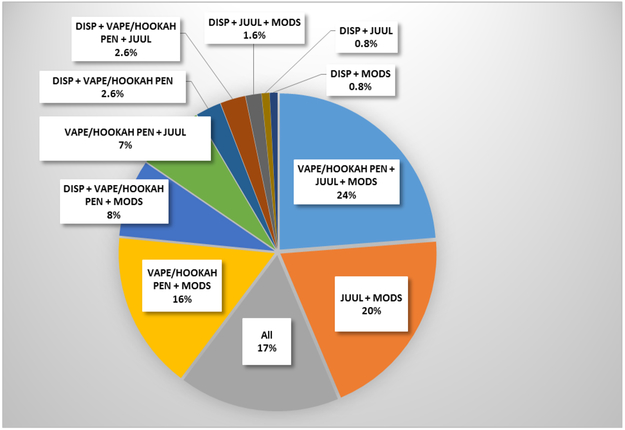

Cig-a-likes were used least frequently (Ever use: cig-a-likes: 25.4%; vape/hookah pens: 60.6%; JUUL: 64.2%; mods: 71.2%; Current use: cig-a-likes: 7.3%; vape/hookah pens; 18.7%; mods: 33.1%; JUUL: 47.1%;). Nicotine use was highest for JUUL (JUUL: 80.3%; mods: 56.3%; cig-a-likes: 51.4%; vape/hookah pens: 46.8%). Among ever users of single devices, use of JUUL was highest (JUUL: 43%; mods: 32%; vape/hookah pens: 21%; cig-a-likes: 4%). Ever use of all devices, except JUUL, was associated with other tobacco product use. Ever use of JUUL was associated with higher SES. Ever use of multiple devices (two: 34.7%; three: 25.8%; four: 11.7%) compared with a single device (27.8%) was associated with other tobacco product use.

Conclusions:

Targeted regulatory and prevention efforts that consider the use of multiple e-cigarette devices are needed to lower youth e-cigarette use rates.

Keywords: E-cigarette, Device, Youth, JUUL

1. Introduction

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) are extremely popular among youth. Evidence from the National Youth Tobacco Survey indicates that current (i.e., past month) e-cigarette use among high school students increased from 1.5% in 2011 to 11.3% in 2016, and e-cigarettes were the most commonly used product in 2016 (Jamal et al., 2017). Similarly, using evidence from high schools in Connecticut, we have reported that e-cigarettes are endorsed as the first tobacco product (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2015) and that current use rates of e-cigarettes were at 11% in 2015 (Camenga et al., 2018).

The current e-cigarette market consists of a plethora of e-cigarette devices. However, we have a limited understanding of the use of different device types by youth. To inform and develop targeted regulatory and prevention strategies to reduce youth e-cigarette use, it is important to understand what kinds of devices are being used by youth. Earlier evidence observed that youth primarily used advanced generation devices and not cig-a-likes (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2017). However, there have been no detailed examinations of which types of devices are used by youth and whether youth use multiple devices.

Early e-cigarette devices (also called cig-a-likes) looked like cigarettes and contained a fixed amount of nicotine. Subsequently, vape-pens or hookah-pens, modified devices or mods (like advanced personal vaporizers, box-style mods and mechanical mods) allowed users to change temperature/voltage, nicotine concentrations, and other constituents of e-liquids including flavors in addition to adding accessories to generate more vapor and enhance the vaping experience. More recent market entrants include “pod devices,” which are discreet, generate less vapor, and are enormously popular among youth; an example is the JUUL, which resembles a USB memory stick and has surpassed all other e-cigarette devices in sales in the past few years (Huang et al., 2018). Of concern, many youths do not use the term “e-cigarettes” to refer to JUULs and also use terms like “JUULing” to indicate use of this device (Willett et al., 2018). Given the constant innovation within the e-cigarette industry, it is important to understand current trends in use of different devices by youth. It is also critical to understand whether youth are using single or multiple devices and whether we can identify predictors of these use behaviors.

Further, it is also important to assess whether youth are using different e-cigarette devices to deliver nicotine. Nicotine is a known neurotoxin in the adolescent brain (Abreu-Villaca et al., 2003), and nicotine concentrations in e-cigarettes have been shown to be important determinants of future cigarette smoking and vaping behaviors (Goldenson et al., 2017). We have observed that the nicotine concentrations used by youth in e-cigarettes are quite variable (Morean et al., 2016). Of note, some e-cigarette devices allow the use of different doses of nicotine including no nicotine, while others like the JUUL and many cig-a-likes are only available with nicotine, further highlighting the importance of better understanding the use of nicotine in the e-cigarette devices used by youth. In addition, the e-liquid used in JUUL and other pod devices contains a nicotine salt, while other e-liquids contain free-base nicotine. Free-base nicotine is volatile and can result in higher absorption rates but is also harsh and causes irritation. Nicotine salt e-liquids contain free-base nicotine with the addition of acids such as benzoic acid, which lowers the pH of the e-liquid, and it is suggested that this allows for delivery of higher doses of nicotine without throat irritation (Chen 1976; Duell et al 2018). The innovation of using nicotine salts in e-liquids adds another layer of complexity to youth e-cigarette use that needs to be explored.

In Spring 2017, we used school-based surveys to examine prevalence rates of using different e-cigarette devices and of using nicotine in each device among high school students who reported ever (i.e., lifetime) use of e-cigarettes. We also evaluated if ever using each device and ever using multiple devices was associated with demographic variables that previously have been shown to be related to e-cigarette use including sex, age, race, other tobacco product use, and socio-economic status (Arrazola et al., 2014; Barrington-Trimis et al., 2015; Simon et al., 2018; Wills et al., 2015).

2. Methods

2.1. Survey procedures

Youth from 4 Southeastern Connecticut high schools (N=2945) were surveyed in Spring 2017. To obtain a socio-demographically diverse sample, these schools were drawn from different district reference groups, which are groupings of schools in CT based on characteristics such as family income levels, parental education levels, parental occupation status, and use of non-English home language (http://www.sde.ct.gov/sde/LIB/sde/PDF/dgm/report1/cpse2006/appndxa.pdf).

The survey was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yale University and the local school administrators. Information sheets were mailed to parents along with the option of declining their child’s participation. Of note, parents of two children declined. Prior to completing the survey, students were informed that participation was voluntary and anonymous and that their data were confidential. Students completed the brief paper survey during their homeroom periods.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. E-cigarette use status.

Students were shown pictures of various e-cigarette devices accompanied by the following questions: 1) “E-cigarettes are battery-powered and produce vapor. Have you ever tried an e-cigarette, even just one or two puffs?” (response options: Yes, No), 2) “How old were you when you first tried an e-cigarette, even just 1 or 2 puffs (response options included individual ages 8 or younger, 9-19), and 3) “Approximately how many days out of the past 30 days did you vape an e-cigarette? (response options ranged from 0-30). Students who responded “yes,” to the first question were classified as “ever” e-cigarette users. Students who did not respond to the first question but responded to the second and third questions and reported use of e-cigarettes during the past 30 days or provided an age when they first used e-cigarettes were also classified as “ever” e-cigarette users. Students who indicated they had used e-cigarettes on 1 or more days in the past 30 days were classified as “current” e-cigarette users.

2.2.2. E-cigarette devices.

We asked students a series of questions about their use of various types of e-cigarettes. A picture was provided for each device along with a descriptor: 1) “Disposable, cig-a-like (shaped like a cigarette, can use one time or can recharge the battery and use many times)”, 2) “Hookah-Pen, Vape-Pen or Ego (Has a battery and a tank for e-liquids)”, 3) “JUUL E-cigarette (Rechargeable with USB charger, has cartridges that insert in device)”, and 4) “Mods or Advanced Personal Vaporizers (Customizable; with customized battery and tank)”. For each device we asked the following questions: 1) Have you ever tried this device? (response options: No, Yes), 2) How many days in the past 30 days did you use this device? (response options: 0-30 days), and 3) Have you used this device with nicotine? (response options: No, Yes, I don’t know). Students who reported ever trying a device were classified as “ever” users of that device, and those who indicated they had used the device at least once in the past 30 days were classified as “current” users of that device. We also quantified “ever” use of single or multiple devices for each student.

2.3. Other measures

2.3.1. Participant demographics.

Students were asked “At birth, what was your sex?’ (response options: male, female), “How old are you?“ (response options: 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18), and “How would you describe yourself?“ (Select all that apply: White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern, and Other).

2.3.2. Socioeconomic status (SES).

SES was assessed using the Family Affluence Scale (FAS), which has shown to be a reliable and valid measure of SES among adolescents (Boyce and Dallago, 2004; Boyce et al., 2006). The questions were: “Does your family own a car, van or truck?” (response options: no; yes, one; yes, two or more), “Do you have your own bedroom for yourself?“ (no; yes), “During the past 12 months, how many times did you travel on a vacation with your family?” (not at all; once; twice; more than twice), and “How many computers (including laptops and tablets, not including game consoles and smartphones) does your family own?” (none; one; two; more than two). A summary score was created from the four items, with higher scores indicating higher SES (range=1-9).

2.3.3. Other tobacco product use.

Students were shown pictures and provided descriptions of each tobacco product and were asked “Have you tried [cigarettes, cigars, cigarillos, hookah, and smokeless tobacco]? (each product was examined individually and response options were “yes” and “no”). Students who responded “yes” to using any of these products were coded as “ever tobacco users”, while students who did not endorse use to any of the products were coded as “never tobacco users.”

2.4. Data analytic plan

Analyses were based on available (i.e., non-missing) data; of note, less than 3 percent of the final sample had missing data on the use of different device types. We first calculated prevalence rates of “ever use” and “current use” of e-cigarettes as well as prevalence rates of nicotine use for each device. We also determined rates of total number of devices d and descriptive information for combined “ever” use of devices. Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine predictors for “ever” use of each device and of multiple devices. Age (continuous variable), sex (male vs. female), race (white vs. non-white), use of other tobacco products (ever tried vs. not), and SES (continuous variable) were included in the models. The alpha level was set to 0.01 to adjust for multiple comparisons.

3. Results

Of the total sample of high school students who were surveyed (N=2945), 1047 (35.6%) were ever e-cigarette users. Among the sample of 1047 ever-e-cigarette users, 875 youth (83.6%) indicated that they had ever tried at least one of the four devices presented to them. The final analytic sample which comprised these 875 ever e-cigarette users was 54.2% females and predominantly white (82.2%) with a mean age of 16.3 (SD=1.2) and an average SES score of 6.8 (SD=1.7). Of note, this analytic sample, when compared to the sample of ever users of e-cigarettes who did not endorse use of any of the devices (n=172), had more females (54.2.vs. 39.5% p=0.005) and more youth endorsing white race (82.2% vs. 63.4%; p<0.001) and other tobacco use (50.8% vs. 40.6%; p=0.049).

With regards to prevalence rates, as Figure 1 shows, ever and current use rates of hookah/vape pen (ever: 60.6%; current: 18.7%), JUUL (ever: 64.2%; current: 47.1%), and mods (ever: 71.2%; current: 33.1%) were high, and use rates of cig-a-like were low (ever: 25.4%; current: 7.3%). See Table 2 for past 30-day frequencies of using each device. As shown in Figure 2, among rs, rates of using nicotine was highest for JUUL (80.3%), followed by mods (56.3%), cig-a-likes (51.4%), and vape/hookah pens (46.8%). Furthermore, 27.8% of youth reported ever use of only one device, while 34.7% reported ever use of two devices, 25.8% reported ever use of three devices, and 11.7% reported ever use of all four devices. Among those using only one device, ever use of JUUL was highest at 43%, followed by mods at 32%, vape/hookah pens at 21%, and cig-a-likes at 4%. In addition, among those using only one device, current use of JUUL was the highest at 32.7%, followed by mods at 12.4% and vape/hookah pens at 2.5%. There were no current cig-a-like users among individuals who only used one device. Among those using multiple devices, combined use of Vape/Hookah Pens and JUULs and mods was highest at 24%, which was followed by combined use of JUUL and mods at 20%, use of all four devices at 17%, and use vape/hookah pens and mods at 16%; all other combinations were lower than 10% (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

“Ever use” and “current use” of e-cigarette devices among ever e-cigarette users (n=875).

Note: Individual participants could have used multiple devices and could be in more than one category

Table 2:

Frequency of past 30 use of each e-cigarette device.

| Days of e-cigarette use in the past 30 days | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Device | N/% | Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

| Disposable, Cig-a-like | 64 (7.3%) | 14.06 | 10 | 1 | 30 |

| Vape/Hookah pen | 164 (18.7%) | 9.05 | 4 | 1 | 30 |

| JUUL | 412 (47.1%) | 11.54 | 6 | 1 | 30 |

| Mods/Advanced personal vaporizers | 290 (33.1%) | 10.92 | 5 | 1 | 30 |

Figure 2.

Use of e-cigarette devices with nicotine among ever users.

Note: Individual participants could have used multiple devices and could be in more than one category

Figure 3.

Type of e-cigarette device ever used by youth who reported use of multiple devices (n=614).

With regards to predictors of use, as shown in Table 1, youth who used disposable/cig-a-likes and mods/advanced personal vaporizers were more likely to have used other tobacco products than were those who have not used these devices. Those who used vape/hookah-pens were more likely to have used other tobacco products and be female, non-white, and of lower SES than were those who did not use vape/hookah pens. JUUL users were more likely to be White and of higher SES compared to those who did not use JUUL. Finally, those who used multiple devices were more likely to have used other tobacco products and be female than individuals who used only one device.

Table 1.

Factors associated with using each e-cigarette device (versus not) and using multiple devices (versus single devices) among ever e-cigarette users who reported using at least one of the devices (n=875).

| Any other tobacco use (ref: No tobacco use) |

Male (ref: Female) |

White (ref: Non-White) |

Age | SES | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Device | |||||

| Disposable, Cig-a-like | |||||

| OR (CI) | 3.43* (2.36-4.99) | 1.19 (0.84-1.69) | 0.64 (0.41-0.99) | 1.21 (1.04-1.41) | 0.93 (0.83-1.03) |

| Vape/Hookah pen | |||||

| OR (CI) | 2.49 * (1.81-3.43) | 0.61 * (0.45-0.84) | 0.50 * (0.32-0.79) | 0.96 (0.84-1.10) | 0.81 * (0.73-0.90) |

| JUUL | |||||

| OR (CI) | 1.29 (0.93-1.79) | 1.19 (0.86-1.64) | 3.92 * (2.58-5.95) | 0.89 (0.78-1.03) | 1.35 * (1.22-1.49) |

| Mods/Advanced personal vaporizers | |||||

| OR (CI) | 2.64 * (1.88-3.71) | 1.11 (0.80-1.54) | 1.38 (0.90-2.12) | 1.07 (0.93-1.23) | 0.97 (0.88-1.08) |

| Use of Multiple Devices | |||||

| OR (CI) | 3.16 * (2.23-4.47) | 0.64 * (0.46-0.89) | 1.48 *(0.96-2.28) | 1.01 (0.88-1.17) | 1.03 (0.93-1.15) |

Note: Logistic regression was performed

p< 0.01. SES variable range=1-9.

4. Discussion

The current study is the first to demonstrate that youth who use e-cigarettes are using a wide variety of devices and in many cases multiple devices. We observed that rates of using mods/advanced personal vaporizers, vape/hookah pens, and the JUUL were much higher than those of cig-a-like products. These results are consistent with prior research suggesting that youth are more likely to use later generation devices compared to cig-a-likes (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2017) but provide more detailed information about which devices are used. Further, approximately two-thirds of youth reported using multiple device types, and these adolescents were also more likely to use other tobacco products. Among youth reporting use of single device, rates of JUUL use were the highest, which may be related to the phenomenal growth in the sales and availability of this product from 2015 to the time of this survey in June 2017 (Allem et al., 2018; Carver, 2018; Huang et al., 2018).

While more students used devices with nicotine, about a third of students who used cig-a-likes, vape-pens, and mods reported that they did not use nicotine in the devices. In contrast, while most students who used JUUL in the past month reported that they used it with nicotine, a smaller percentage of students reported that they used JUUL without nicotine (8.5%) or that they did not know if they used JUUL with or without nicotine (9.5%). It is important to note JUULs are only available with high levels of nicotine (50-60 ng/ml) (Pankow et al., 2017), which raises significant concerns about high levels of nicotine exposure among youth. A recent study observed that youth who used JUUL had higher urine cotinine levels (Goniewicz et al., 2018). Further, while cig-a-likes, vape/hookah pens and mods were more likely to be used by youth who used other tobacco products, a similar association was not observed for JUUL use, suggesting that JUULs may disproportionately be used by youth who are tobacco/nicotine naive. Alternatively, it is also possible that since JUUL contains high levels of nicotine, youth may not need to use other tobacco products. Future studies need to explore these and other reasons why youth use each of these devices and to understand the doses of nicotine that are being used in different devices.

As stated earlier, some youth reported that they did not use nicotine in their device(s). Although these youth may be protected from the deleterious effects of nicotine, e-liquids contain many other components like propylene glycol, glycerin, and many flavor chemicals. Emerging evidence suggests that non-nicotine constituents are not inert and do alter e-cigarette effects. For example, studies have found that flavor chemicals can have toxic effects (Behar et al., 2018; Bengalli et al., 2017; Muthumalage et al., 2017; Rowell et al., 2017), and other components form thermal degradation products when vaporized, which are known toxicants (Kamilari et al., 2018; Pankow et al., 2017; Sleiman et al., 2016). Further, e-liquids containing flavors are appealing to youth e-cigarette users even in the absence of nicotine (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 2017). Future studies need to examine the toxicity of exposure to nicotine-free e-cigarettes and to examine if exposure to these nicotine-free e-liquids is sufficient to maintain e-cigarette use and/or to promulgate progression to the use of nicotine e-liquids.

Of concern, many youths who used cig-a-likes (22.3%), vape-pens (21.3%), and mods (14.3%) reported that they did not know if they had used the devices with nicotine in the past month. Although these rates are lower than the rate that we previously observed (Morean et al., 2016), these findings are still concerning. It is possible that these youths are not aware of the nicotine concentrations in their e-cigarettes because they obtain their devices from others. However, it also is possible that the labels on e-cigarettes and e-liquids continue to be unclear about nicotine content (at least among youth), suggesting that the FDA needs to establish and enforce stricter regulations regarding e-cigarette content labeling.

Interestingly, our results indicate that vape/hookah pens were used more often by lower SES youth, while JUUL was used more often by higher SES youth; these differences may be reflective of the price differences between these devices. Alternatively, it is possible that the increased JUUL use among high-SES youth may be related to exposure to more JUUL advertisements. In fact, our recent studies in CT high schools observed that high-SES youth were more likely to be exposed to more e-cigarette advertising than low-SES youth (Simon et al., 2018). Future studies are needed to understand if there is a differential role of advertising exposure on the use of different devices.

The study findings should be considered with certain limitations. First, our evidence was obtained in CT, and these results need to be replicated in larger, national surveys; however, as pointed out earlier, the e-cigarette prevalence rates observed in our survey evidence from CT were comparable to those observed in national surveys. Further, a smaller percentage of youth (16.4%) in our study reported ever use of e-cigarettes but did not endorse use of any of the devices we examined; future studies need to examine if these youths were just unaware of their device type or whether they were using other devices that were not included in our survey. Additionally, we did not specifically assess nicotine concentrations used or the use of other substances in each device (e.g., marijuana, hash oil). We also did not obtain information on other characteristic of the devices, such as whether they were disposable/rechargeable, had mechanisms to manipulate temperature or puff volume, or whether they were used with flavors. Finally, while we assessed JUUL use, we did not include an assessment of other pod devices (e.g., Phix; Suorin). Future studies need to assess adolescents’ use of these other devices and obtain more specific information on the use of nicotine and other device characteristics, to inform regulation of e-cigarettes.

Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on concurrent prevalence rates of different e-cigarette devices, including JUUL, among youth. These results suggest that it is important to be aware of different device types when assessing youth e-cigarette use behaviors. Further, these results support specific targets (i.e., device types) for regulatory action that could reduce use of e-cigarettes by youth. The FDA has recently announced stricter regulations on the sales of products like JUUL to reduce youth access. Similar regulations should also be applied to other e-cigarette devices like mods and vape/hookah pens. Continued surveillance of the use of different devices by youth is critical to monitoring the effectiveness of e-cigarette regulations and to developing methods of reducing the appeal of these devices to youth.

Highlights.

Among youth, use of JUUL, mods, and vape/hookah pens were higher than cig-a-likes.

Nicotine use was highest for JUUL, followed by mods, cig-a-likes, and vape pens.

Use of multiple devices was common, but JUUL was the highest single use device.

Users of all devices, except JUUL, used other tobacco products.

Use of JUUL was associated with higher SES.

Acknowledgments

Role of the Funding Source

The research reported in this publication was supported by NIH grants P50DA036151 (Yale TCORS) and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose. The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. Although not related to the current research study, Dr. Krishnan-Sarin reports the following: receiving donated research study medications from Astra Zeneca, Pfizer.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abreu-Villaca Y, Seidler FJ, Tate CA, Slotkin TA, 2003. Nicotine is a neurotoxin in the adolescent brain: Critical periods, patterns of exposure, regional selectivity, and dose thresholds for macromolecular alterations. Brain Res. 979, 114–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allem JP, Dharmapuri L, Unger JB, Cruz TB, 2018. Characterizing JUUL-related posts on Twitter. Drug Alcohol Depend. 190, 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrazola RA, Neff LJ, Kennedy SM, Holder-Hayes E, Jones CD, 2014. Tobacco use among middle and high school students— United States, 2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 63, 1021–1026. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Huh J, Leventhal AM, Urman R, Wang K, Howland S, Gilreath TD, Chou CP, Pentz MA, McConnell R, 2015. Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent electronic cigarette and cigarette use. Pediatrics 136, 308–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Gibson LA, Halpern-Felsher B, Harrell MB, Kong G, Krishnan-Sarin S, Leventhal AM, Loukas A, McConnell R, Weaver SR, 2017. Type of e-cigarette device used among adolescents and young adults: Findings from a pooled analysis of 8 studies of 2,166 vapers. Nicotine Tob. Res 20, 271–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar RZ, Luo W, McWhirter KJ, Pankow JF, Talbot P, 2018. Analytical and toxicological evaluation of flavor chemicals in electronic cigarette refill fluids. Sci. Rep 8, 8288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengalli R, Ferri E, Labra M, Mantecca P, 2017. Lung toxicity of condensed aerosol from e-cig liquids: Influence of the flavor and the in vitro model used. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, E1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce W, Torsheim T, Currie C, Zambon A, 2006. The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: Validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Soc. Indic. Res 78, 473–487. [Google Scholar]

- Camenga DR, Bold KW, Morean ME, Kong G, Simon P, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2018. The appeal and use of customizable e-cigarette product features among adolescents. Tob. Regul. Sci 4, 51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver R, 2018. JUUL continues to expand market share gap with VUSE; Newport keeps ticking up. Winston-Salem Journal, Winston-Salem, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, 1976. pH of Smoke: A review, report number N-170, internal document of Lorillard Tobacco Company. Lorillard Tobacco Company, Greensboro, NC: pp 18. [Google Scholar]

- Duell AK, Pankow JF, Peyton DH, 2018. Free-base nicotine determination in electronic cigarette liquids by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Chem. Res. Toxicol 31, 431–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenson NI, Leventhal AM, Stone MD, McConnell RS, Barrington-Trimis JL, 2017. Associations of electronic cigarette nicotine concentration with subsequent cigarette smoking and vaping levels in adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 171, 1192–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goniewicz ML, Boykan R, Messina CR, Eliscu A, Tolentino J, 2018. High exposure to nicotine among adolescents who use Juul and other vape pod systems ('pods'). Tob. Control Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, Binns S, Vera LE, Kim Y, Szczypka G, Emery SL, 2018. Vaping versus JUULing: How the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob. Control Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A, Gentzke A, Hu SS, Cullen KA, Apelberg BJ, Homa DM, King BA, 2017. Tobacco use among middle and high school students— United States, 2011-2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 66, 597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamilari E, Farsalinos K, Poulas K, Kontoyannis CG, Orkoula MG, 2018. Detection and quantitative determination of heavy metals in electronic cigarette refill liquids using Total Reflection X-ray Fluorescence Spectrometry. Food Chem. Toxicol 116, 233–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Green BG, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Jatlow P, Gueorguieva R, Buta E, O'Malley SS, 2017. Studying the interactive effects of menthol and nicotine among youth: An examination using e-cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 180, 193–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Morean ME, Camenga DR, Cavallo DA, Kong G, 2015. E-cigarette use among high school and middle school adolescents in Connecticut. Nicotine Tob. Res 17, 810–818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Kong G, Cavallo DA, Camenga DR, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2016. Nicotine concentration of e-cigarettes used by adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 167, 224–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthumalage T, Prinz M, Ansah KO, Gerloff J, Sundar IK, Rahman I, 2017. Inflammatory and oxidative responses induced by exposure to commonly used e-cigarette flavoring chemicals and flavored e-liquids without nicotine. Front. Physiol 8, 1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankow JF, Kim K, McWhirter KJ, Luo W, Escobedo JO, Strongin RM, Duell AK, Peyton DH, 2017. Benzene formation in electronic cigarettes. PloS One. 12, e0173055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell TR, Reeber SL, Lee SL, Harris RA, Nethery RC, Herring AH, Glish GL, Tarran R, 2017. Flavored e-cigarette liquids reduce proliferation and viability in the CALU3 airway epithelial cell line. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol 313, L52–L66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon P, Camenga D, Morean M, Kong G, Bold KW, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2018. Socioeconomic status and adolescent e-cigarette use: The mediating role of e-cigarette advertisement exposure. Prev. Med 112, 193–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleiman M, Logue JM, Montesinos VN, Russell ML, Litter MI, Gundel LA, Destaillats H, 2016. Emissions from electronic cigarettes: Key parameters affecting the release of harmful chemicals. Environ. Sci. Technol 50, 9644–9651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett JG, Bennett M, Hair EC, Xiao H, Greenberg MS, Harvey E, Cantrell J, Vallone D, 2018. Recognition, use and perceptions of JUUL among youth and young adults. Tob. Control Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, Pagano I, Sargent JD, 2015. Risk factors for exclusive e-cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics 135, e43–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]