Abstract

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a complex multi-system disorder due to errors in genomic imprinting with severe hypotonia, decreased muscle mass, poor suckling, feeding problems and failure to thrive during infancy, growth and other hormone deficiency, childhood-onset hyperphagia and subsequent obesity. Decreased energy expenditure in PWS is thought to contribute to reduced muscle mass and physical activity but may also relate to cellular metabolism and disturbances in mitochondrial function. We established fibroblast cell lines from six children and adults with PWS and six healthy controls for mitochondrial assays. We used Agilent Seahorse XF extra-cellular flux technology to determine real-time measurements of several metabolic parameters including cellular substrate utilization, ATP-linked respiration and mitochondrial capacity in living cells. Decreased mitochondrial function was observed in the PWS patients compared to the healthy controls with significant differences in basal respiration, maximal respiratory capacity and ATP-linked respiration. These results suggest disturbed mitochondrial bioenergetics in PWS although a low number of studied subjects will require a larger subject population before a general consensus can be reached to identify if mitochondrial dysfunction is a contributing factor in PWS.

Keywords: Prader-Willi syndrome, mitochondrial assays and dysfunction, fibroblasts, healthy controls

INTRODUCTION

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a genetic disorder that is characterized by clinical manifestations involving disturbed growth, development and clinical findings noted in infancy but continued through adulthood. These findings include weak muscle tone (hypotonia) and mass, poor sucking and infantile feeding difficulties with failure to thrive, growth and other hormone deficiencies with slow growth, hypogenitalism/hypogonadism and global developmental delay. Later in childhood, food seeking and hyperphagia lead to obesity. During adolescence, short stature, small hands and feet, delayed puberty, cognitive impairment, behavioral problems (e.g., temper tantrums, violent outbursts, obsessive/compulsive behavior) are noted. Dysmorphic features include bifrontal narrowing, upslanting palpebral fissures, downturned corners of mouth (Butler 1990; Holm et al., 1993; Butler et al., 2006; Butler, 2011; Cassidy et al., 2012; Angulo et al., 2015; Butler, 2016). PWS is due to errors in genomic imprinting with lack of paternally expressed genes generally from a deletion of the chromosome 15q11-q13 region in about 60% of cases, maternal uniparental disomy 15 (mUPD) with both chromosome 15s from the mother in about 35% and imprinting defects or chromosome 15 translocations in the remaining cases (Butler et al., 2018).

PWS is recognized as the most common known cause of marked obesity in humans (Butler, 1990) resulting from chronic imbalance between energy intake and expenditure due to hyperphagia with an inability to vomit, decreased muscle mass, tone and physical activity with a reduced resting metabolic rate (Hill et al., 1990; Butler et al., 2006; Butler et al., 2007). Body fat in individuals with PWS without growth hormone treatment can account for 40–50% of their body composition, which is two or three times higher than in the general population (Butler et al., 1986), about one-third of individuals weigh more than 200% of their ideal body weight (Butler and Meaney, 1987; Meaney and Butler, 1989a; 1989b). Total energy, resting energy, sleeping energy and active energy expenditure are lower in individuals with PWS than in control individuals without the syndrome (Schoeller et al., 1988; Hill et al., 1990; Butler et al., 2007). Lower physical activity and alteration in lean body mass are thought to be responsible for the lower energy expenditure in PWS (Butler et al., 2007) although data are limited related to metabolic differences or cellular metabolism in PWS (Alsaif et al., 2017). The complex clinical manifestations of PWS are attributed to the loss of paternally expressed imprinted genes on the chromosome 15q11-q13 region but unexplained downstream changes and regulatory networks involving other genes may play a role. Downstream genes are reported to be affected by the deletion process in PWS and could involve unrecognized metabolic pathways (Bittel et al., 2003).

Clinical reports in PWS and PWS mouse models show evidence of metabolic disturbances and differential expression of mitochondrial genes that could contribute to pathophysiology (Yazdi et al., 2013). Mitochondria play an important cellular role in energy metabolism by carrying out essential cellular functions including the generation of ATP by oxidative phosphorylation, intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, reactive oxygen species biology, synthesis and catabolism of metabolites with transport to correct locations within the cells for optimal function and for apoptosis (Wallace, 2005). An abnormality of any of these processes can lead to energy balance disturbances.

Disturbances in mitochondrial function could contribute to several common features seen in PWS including decreased energy, hypotonia, lower metabolic rate, severe obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus and oxidative stress (Perrone et al., 2016). However, whether and how mitochondrial functional capacity is altered in PWS is not known. Thus, we undertook a study using living cells (fibroblasts) from subjects with PWS and healthy controls in order to assess the impact of mitochondrial performance using Agilent Seahorse XF extra-cellular flux technology which allows real-time measurements of several metabolic parameters including cellular substrate utilization, ATP-linked respiration and mitochondrial capacity (Chavan et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2017).

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study Participants

Fibroblast cells were established from six patients with Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) and six healthy controls ranging in age from 1 to 29 years for mitochondrial function assays. Fibroblast cells were successfully analyzed with Agilent Seahorse XF technology following manufacturer’s recommendation (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA, USA) on four subjects with PWS (3 year old male, 3 year old female, 7 year old male and 29 year old male) and five controls (1 year old male, 2 year old male, 12 year old male, 21 year old male and 31 year old female). Cells did not adhere properly throughout the assay in three subjects and therefore were unsuccessfully analyzed. Two PWS individuals had genetically confirmed 15q11-q13 deletions and two had maternal disomy 15 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Fibroblast Mitochondrial Function Assay for Prader-Willi Syndrome and Control Subjects

| Subjects with Prader-Willi Syndrome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | Age sample taken (years) |

Sex | Race | Height (H), Weight (W) & Body Mass Index (BMI) |

Diagnosis | Growth hormone treatment |

| PWS-1 | 3 year old | Female | Caucasian | H: 94cm (3%ile) W: 19.9kg (10%ile) BMI: 22.5kg/m2 |

PWS with 15q11-q13 type II deletion |

Yes |

| PWS-2 | 7 year old | Male | Caucasian and African American |

H: 107cm (11%ile) W: 32.2kg (99%ile) BMI: 28.1kg/m2 |

PWS with maternal UPD15 segmental isodisomy |

Yes |

| PWS-4 | 3 year old | Male | Caucasian | H: 91cm (24%ile) W: 14.42kg (64%ile) BMI: 17.4kg/m2 |

PWS with 15q11-q13 type II deletion |

Yes |

| PWS-6 | 29 year old | Male | Caucasian | H: 125cm (3%ile) W: 84.0kg (70%ile) BMI: 53.8kg/m2 |

PWS with maternal UPD15 segmental isodisomy |

No |

| Control Subjects | ||||||

| ID | Age sample taken (years) |

Sex | Race | Height (H), Weight (W) & Body Mass Index (BMI) |

Diagnosis | Growth hormone treatment |

| Control-1 | 2 year old | Male | Caucasian | Non-obese | Healthy | No |

| Control-2 | 12 year old | Male | Caucasian | Non-obese | Healthy | No |

| Control-5 | 1 year old | Male | Caucasian | Non-obese | Healthy | No |

| Control-4 | 31 year old | Male | Caucasian | Non-obese | Healthy | No |

| Control-6 | 21 year old | Female | Caucasian | Non-obese | Healthy | No |

Fibroblast cell cultures were established as follows: Cells were plated onto gelatin-coated tissue culture plates in 10% FBS supplemented with antibiotics (1 mg/mL amphotericin B, 50 mg/mL gentamicin, 200 units/mL penicillin streptomycin, and 1x Plasmocin Prophylactic). Media was changed daily for the first three days, then every 48 hours for the next 1–2 weeks. When colonies formed, they were passaged with attenuated trypsin solution (0.1% trypsin, 0.5 mM EDTA, 1% chicken serum) and allowed to grow to 90% confluency before being frozen in liquid nitrogen. For this study, the fibroblast cell lines from both controls and those with PWS were reconstituted in DMEM (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA), 15% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cells were studied between passages 4–7 and grown to 75–80% confluency in T 75 flasks.

Cell Preparation for Seahorse Assay

To investigate oxygen consumption rates (OCRs: as indicator of mitochondrial respiration), the Agilent Seahorse XF24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA) was used as previously described (Chaven et al., 2017). Cells were seeded in collagen treated XF24 cell culture plates at 30,000 cells/well in 100 uL growth medium (DMEM medium containing 10% FBS) and placed in 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2. After 4 hours when the cells adhered to the wells, 150 uL of additional media was added to each well. The plate was kept overnight in the incubator. The next day the plate was prepared as follows for the Seahorse assay: Growth medium from each well was removed leaving 50 uL media in each well, each well was then washed twice with 500 uL pre-warmed assay medium (XF base medium supplemented with 25 mM glucose, 2 mM glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate; pH 7.4) and 500 uL assay media was added making the final volume 550 uL. The plate was then incubated in the 37 °C incubator without CO2 for 1 hour to establish equilibration with the assay medium. Oligomycin, carbonyl cyanide p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP), rotenone/antimycin A were added to injector ports A, B, and C, respectively. The final concentrations of the injections were as follows: 10 uM oligomycin, 2.7 uM FCCP, 10 uM rotenone and antimycin A. The cartridge was calibrated by the Seahorse XF24 analyzer and the assay continued using the Mito Stress Test assay protocol as described by (Nicholls et al., 2010). Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) were detected under basal conditions followed by the sequential addition of oligomycin, FCCP followed by rotenone and antimycin A. This allowed for an estimation of the contribution of individual parameters for basal respiration, proton leak, maximal respiration capacity, spare reserve respiration capacity, non-mitochondrial respiration and ATP-linked respiration (Tan et al., 2015a; 2015b) (Figure 1).

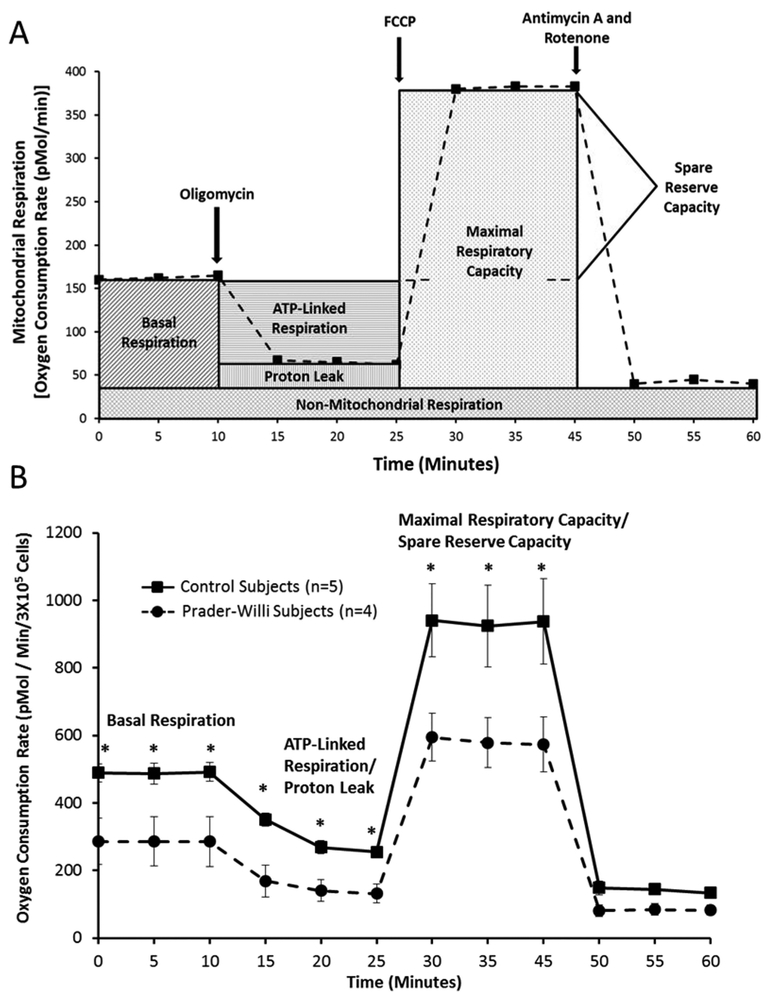

Figure 1.

1A Schematic diagram of Agilent Seahorse XF extra-cellular flux technology and mitochondrial function components and profiles modified from Agilent website (www.agilent.com/en/products/cell-analysis-(seahorse)/mitochondrial-respiration-xf-cell-mito-stress-test). 1B Comparison of stages of mitochondrial function and cellular respiration with time using fibroblasts from Prader-Willi syndrome and control subjects with error bars and significant differences (t test; p<0.05) noted (*) for basal respiration, ATP-linked respiration/proton leak and maximal respiratory capacity with decreased values for Prader-Willi syndrome.

RESULTS

Basal Respiration

Information on how mitochondria function in intact cells has largely been derived from assays that measure ongoing bioenergetic profile (Tan et al., 2017; Chavan et al., 2017). Intracellular mitochondrial function can be determined by the sequential addition of pharmacological inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation (Brand and Nicholls, 2011; Dranka et al., 2011) to measure the various aspects of mitochondrial respiratory profile. However, for meaningful comparisons between disease and normal cell types, and to avoid ambiguity associated with the differences in cell size, shape or number, we normalized the basal OCR to the total number of live cells (3×105 cells). In the first series of measurements, the basal oxygen consumption of the cells, which represents the net sum of all processes in the cell capable of consuming O2 including mitochondria and other oxidases was measured. The results from these studies demonstrate that in all PWS patient-derived cells, oxygen consumption or basal respiratory rates were significantly reduced (t test; p< 0.05) (Figures 1 and 2).

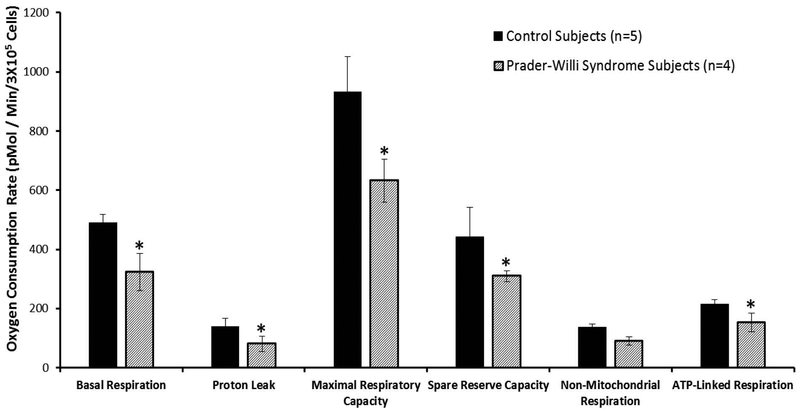

Figure 2.

Comparison of mitochondrial function and cellular respiration in fibroblasts from Prader-Willi syndrome and control subjects with error bars showing individual parameters for basal respiration, proton leak, maximal respiratory capacity, spare reserve capacity, non-mitochondrial respiration and ATP-linked respiration or coupled respiration. Significant differences (t test; p<0.05) are noted (*) with decreased values in subjects with Prader- Willi syndrome for five of six parameters.

Coupled or ATP-linked Respiration

To test the relative contribution of basal respiration to the demand on the proton motive force (for making either ATP or moving other ions across the inner membrane), we used oligomycin, a pharmacological inhibitor of energy-required processes. Oligomycin inhibits ATP synthase and the decrease in OCR in response to oligomycin is then related to the proportion of mitochondrial activity used to generate ATP (coupled respiration) (Ainscow and Brand, 1995). We found that in response to oligomycin, PWS patient cells, irrespective of age and sex, showed a significant decrease in coupled respiration (t test; p< 0.05), suggesting a decreased coupling of basal respiration to ATP generation (Figures 1 and 2).

Maximal Respiratory Capacity and Spare Reserve Capacity

An emerging concept in the energetics field is reserve capacity which can be used as an index of mitochondrial health (Dranka et al., 2011; Brand and Nicholls, 2011; Zelickson et al., 2011; Higdon et al., 2012). By indicating how close a cell is to operating at its bioenergetic limit, predictions can be made regarding the cellular response to stress or increased energy demand. To estimate the maximal potential respiration sustainable by cells, a proton ionophore (uncoupler) such as FCCP is used. Immediately upon exposure to the uncoupler, oxygen consumption increases as the mitochondrial inner membrane becomes permeable to protons, and electron transfer is no longer controlled by the proton gradient. We found that irrespective of age and sex, all PWS patient cells demonstrated a significant decrease in maximal respiratory capacity (t test; p< 0.05) suggesting decreased ability to respond to additional energy demands (Figures 1 and 2).

Non-mitochondrial Respiration

In addition to mitochondrial respiration, cells use some of the consumed oxygen for non-mitochondrial oxygen consuming processes. This non-mitochondrial respiration is measured by inhibiting the respiratory chain with antimycin A, either alone or in combination with rotenone, which inhibits mitochondrial complex III and complex I, respectively. Such pharmacological inhibition of electron transport typically inhibits the majority of oxygen consumption in the cell, and the remaining O2 consumption is attributed to non-mitochondrial oxidases present in the cell. Interestingly, PWS patient non-mitochondrial respiration was significantly decreased (t test; p< 0.05) in our study suggesting alterations in additional oxidative pathways.

Proton Leak

The addition of oligomycin is assumed to completely eliminate control of respiration by oxidative phosphorylation, and the remaining rate of mitochondrial respiration is then taken to represent the cumulative proton leak that was present prior to addition of oligomycin. An increase in the ATP-linked rate of O2 consumption would indicate an increase in ATP demand, and a decrease would indicate either low (ATP) demand, a lack of substrate availability, or severe damage to the electron transfer chain (ETC), which would impede the flow of electrons and result in a lower OCR. An increase in apparent proton leak could be due to a number of factors: increased uncoupled activity (Echtay et al., 2002; Divakaruni and Brand, 2011); damage to the inner mitochondrial membrane and/or ETC complexes, allowing H+ to leak into the matrix; or there could be electron slippage, which would result in oxygen consumption in the absence of proton translocation (Brown, 1992). We found that at face value the cells from PWS patients showed a significant decrease in proton leak compared to the control cells. However, under the conditions where basal respiration is significantly different between the experimental groups, it is important to consider the ratio of proton leak compared to basal respiration to quantify the apparent proton leak. Thus, we measured the apparent proton leak in the PWS patient samples compared to controls. We found that the apparent proton leak, as a percentage of basal OCR was significantly higher in the PWS patient cell lines (i.e., 13% for control and 23% for PWS) for both children and adults. These results suggest that the decrease in coupled respiration in PWS cells is probably a result of increased proton leak.

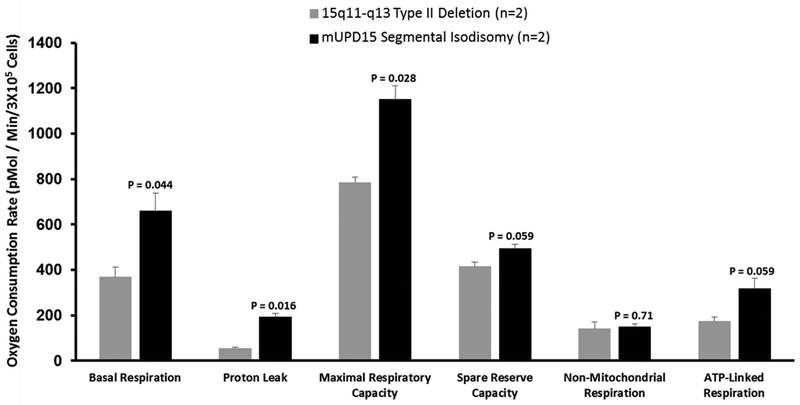

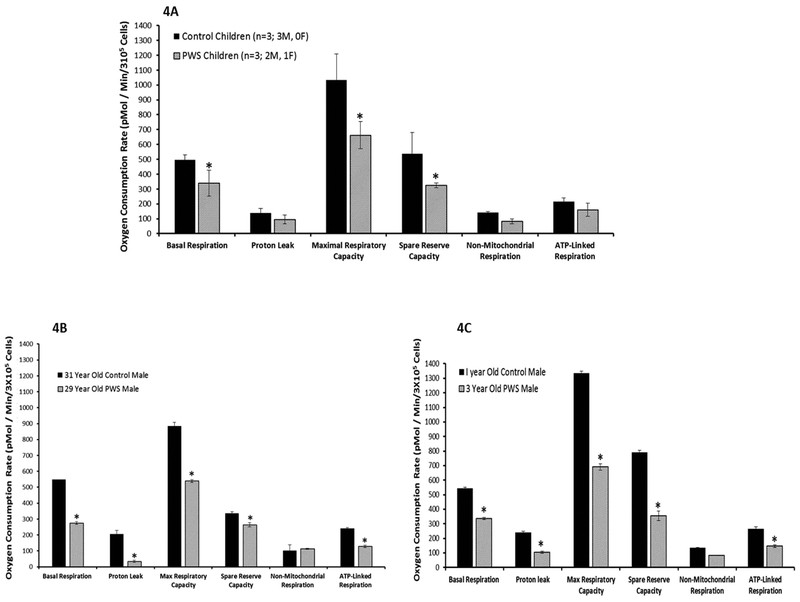

Comparison of PWS genetic subtypes (i.e., 15q11-q13 Type II deletion and maternal disomy 15) showed significantly lower basal respiration, proton leak and maximal respiratory capacity in the deletion subtype (Figure 3). Age and genetic differences were also examined and the control children (n=3; 3 M, 0 F; age range of 1 to 12 years) showed significantly higher basal respiration, maximal respiratory capacity and spare reserve capacity compared with PWS children (n=3; 2 M, 1 F; age range 3 to 7 years). Similarly, when comparing an adult control male (31 year old) with an adult PWS male (29 year old) and one year old control male with a three year old PWS male, significantly lower values were found for basal respiration, protein leak, maximal respiratory capacity, spare reserve capacity and ATP-linked respiration in the PWS subjects (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Comparison of Prader-Willi syndrome genetic subtypes with p values generated using t tests indicated above the vertical bars.

Figure 4.

Comparison of mitochondrial function and cellular respiration in fibroblasts from Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) and control subjects with error bars showing individual parameters for basal respiration, proton leak, maximal respiratory capacity, spare reserve capacity, non-mitochondrial respiration and ATP-linked respiration or coupled respiration. 4A Comparison of control and PWS subjects; 4B Comparison of age and gender matched adult subjects and 4C Comparison of age and gender matched children. Significant differences (t test; p<0.05) are noted (*) with decreased mitochondrial measures in subjects with Prader-Willi syndrome.

DISCUSSION

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) results from loss of paternally expressed imprinted genes from chromosome 15q11–15q13 leading to disturbances in neurodevelopment that manifests as multiple complex phenotypes which include hypotonia, weight gain with decreased energy expenditure, increased appetite and obesity and developmental delay with cognitive impairment and behavioral problems. None of the imprinted genes involved in the 15q11-q13 region and PWS are known to be associated with mitochondrial function or cellular metabolism. The similarities between individuals with PWS and those with mitochondrial myopathy have raised suspicions that there may be a relationship between these conditions. However, in comparing coding and non-coding expression patterns from fibroblasts of lean, obese or PWS individuals, no mitochondrial related nuclear genes were found to be disturbed in PWS (Butler et al., 2015). In addition, clinical evidence does support that PWS patients derive therapeutic benefit from supplementation with Coenzyme Q10, a mitochondrial component of the electron transport chain. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that both PWS males and females during child and adulthood might have altered mitochondrial bioenergetics which may be a component of PWS pathology. Mitochondrial problems have also been reported in a PWS imprinting center deletion, mouse model with disturbances of enzyme activities in cardiac mitochondrial complexes (e.g., IV) that were upregulated compared to wild-type (Yazdi et al., 2013). They proposed that differential gene expression played a role or contributed to PWS pathogenesis in their model. Furthermore, neurons rely heavily on the mitochondria for their function and survival with disturbances leading to neurodegeneration as seen in Parkinson’s disease. Necdin (NDN) is an imprinted gene in the chromosome 15q11-q13 region and deleted in the majority of individuals with PWS. It promotes mitochondrial biogenesis in mammalian neurons through stabilization and neuroprotection against mitochondrial insults.

A second gene that could impact mitochondrial function is TUBGCP5 which is located in the proximal 15q11.2 BP1-BP2 area within the 15q11-q13 region. It is involved with the cytoskeleton and is deleted in individuals with PWS having the 15q11-q13 Type I deletion (Butler et al., 2006). One could speculate that fibroblasts from those PWS individuals with this gene deleted may have difficulty with adherence to the cell culture flasks not allowing the mitochondrial assays to be completed. When comparing the PWS genetic subtypes in those with PWS and mitochondrial assay failure, no genetic subtype differences were observed but the number of subjects studied were small and will require further testing. However, when comparing those with PWS and the 15q11-q13 deletion or maternal disomy 15, we observed a significant difference in basal respiration, proton leak and maximal respiratory capacity with increased levels in the maternal disomy 15 class compared with 15q11-q13 deletions.

Another important gene to consider in future studies and in relationship to observed differences involved in mitochondrial function without the 15q11-q13 deletion in PWS is POLG. This gene is located on chromosome 15 at the q26.1 band. When disturbed, this gene leads to mitochondrial DNA depletion syndrome and plays a role as a DNA polymerase required for replication of human mitochondrial DNA (Ashley et al., 2008; Filosto et al., 2003). Patients with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) depletion are reported with decreased activity of mitochondrial DNA-encoded respiratory chain complexes (Davidzon et al., 2005) and decreased energy expenditure at the cellular level. About 1 in 50 individuals are thought to be carriers of a POLG recessive gene variant with potential risk to have children with mitochondrial DNA depletion. If a mother is a carrier of this recessive allele on chromosome 15 and has a child with PWS due to maternal disomy 15 with segmental or total isodisomy 15 including this gene, then the child with PWS could develop this mitochondrial condition as well with advanced age and diminished mitochondrial function.

Mitochondrial bioenergetics can be assessed in intact patient cell lines, with an undisturbed cellular environment, to study the physiological and pathological mechanisms that suggest compromised energy metabolism or mitochondrial dysfunction. Coupled with an extracellular flux analyzer that measures ongoing bioenergetic profile (Tan et al., 2017; Chavan et al., 2017), such studies can provide information on mitochondrial dysfunction associated with specific diseases. Thus, we used fibroblast cells from individuals with PWS and healthy control subjects to assess mitochondrial respiration and oxygen consumption rates measured as an indicator of mitochondrial function. In PWS patient fibroblasts, basal respiration was significantly lower compared to normal fibroblasts, suggesting a change in cellular bioenergetics but a larger sample size is needed in future studies. Consistent with this observation, the rate of mitochondrial ATP synthesis and the coupling efficiency measured as a change in basal respiration rate on addition of oligomycin, was significantly reduced in PWS patient fibroblasts compared to normal fibroblasts. Because coupling efficiency is sensitive to changes in all bioenergetic modules, this suggests a potential dysfunction, and may be the reason that supplementation with Coenzyme Q10, in young children with PWS may have beneficial effects (Butler et al., 2003; Eiholzer et al., 2008).

In cells, such as fibroblasts, where secondary effects of uncoupling have no significant consequences, uncoupled rates can report the maximum activity of electron transport and substrate oxidation. A decrease in maximal respiratory activity is a strong indicator of potential mitochondrial dysfunction, consistent with the hypothesis that mitochondrial dysfunction is a significant component of PWS. We observed significant decreases in maximal respiratory capacity in fibroblasts from PWS patients suggesting mitochondrial dysfunction.

Our results indicate disturbed mitochondrial bioenergetics in PWS, although the number of subjects was small in this pilot study. A larger cohort of PWS subjects is needed to replicate our findings and to further characterize if gender, age or PWS genetic subtypes contribute to study observations. In addition, assessment of cellular ATP levels, the expression and activity of respiratory complexes and analysis of mitochondrial metabolites in such cohorts might help in potential therapeutic options in managing PWS and identifying those at a young age requiring metabolic interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the support of the National Center for Research Resources grant number 5P20RR021940–07 (P.K.), National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant number 8P20GM103548–07 (P.K.) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant number R21ES026752 (P.K.). We also acknowledge Prayer-Will support and the Kyleigh Ellington Family as well as Charlotte Weber for expert preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to report for any of the authors.

REFERENCES

- Ainscow EK, & Brand MD (1995). Top‐down control analysis of systems with more than one common intermediate. European Journal of Biochemistry, 231(3), 579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsaif M, Elliot SA, MacKenzie ML, Prado CM, Field CJ, & Haqq AM (2017). Energy Metabolism Profile in Individuals with Prader-Willi Syndrome and Implications for Clinical Management: A Systematic Review. Advances in Nutrition, 8(6), 905–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo M, Butler MG, & Cataletto M (2015). Prader-Willi syndrome: a review of clinical, genetic, and endocrine findings. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 38(12), 1249–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashley N, O’rourke A, Smith C, Adams S, Gowda V, Zeviani M, . . . Poulton J (2008). Depletion of mitochondrial DNA in fibroblast cultures from patients with POLG1 mutations is a consequence of catalytic mutations. Human Molecular Genetics, 17(16), 2496–2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittel DC, Kibiryeva N, Talebizadeh Z, & Butler MG (2003). Microarray analysis of gene/transcript expression in Prader-Willi syndrome: Deletion versus UPD. Journal of Medical Genetics, 40(8), 568–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand MD, & Nicholls DG (2011). Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochemical Journal, 435(2), 297–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GC (1992). The leaks and slips of bioenergetic membranes. The FASEB Journal, 6(11), 2961–2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, & Meaney FJ, & Palmer CG (1986). Clinical and cytogenetic survey of 39 individuals with Prader- Labhart-Willi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 23(3), 793–809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, & Meaney FJ (1987). An anthropometric study of 38 individuals with Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 26(2), 445–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG (1990). Prader‐Willi syndrome: Current understanding of cause and diagnosis. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 35(3), 319–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Dasouki M, Bittel D, Hunter S, Naini A, & DiMauro S (2003). Coenzyme Q10 levels in Prader‐Willi syndrome: Comparison with obese and non‐obese subjects. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 119(2), 168–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M, Lee PD, & Whitman BY (2006). Management of Prader-Willi Syndrome: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Theodoro MF, Bittel DC, & Donnelly JE (2007). Energy expenditure and physical activity in Prader-Willi syndrome: comparison with obese subjects. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 143(5), 449–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG (2011). Prader-Willi syndrome: Obesity due to genomic imprinting. Current Genomics, 12(3), 204–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG (2016). Single gene and syndromic causes of obesity: Illustrative examples. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science, 140, 1–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Kimonis V, Dykens E, Gold JA, Miller J, Tamura R, & Driscoll DJ (2018). Prader–Willi syndrome and early‐onset morbid obesity NIH rare disease consortium: A review of natural history study. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 176(2), 368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Wang K, Marshall JD, Naggert JK, Rethmeyer JA, Gunewardena SS, Manzardo AM (2015). Coding and noncoding expression patterns associated with rare obesity-related disorders: Prader-Willi and Alström syndromes. Advanced in Genomics and Genetics, 2015(5), 53–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy SB, Schwartz S, Miller JL, & Driscoll DJ (2012). Prader-Willi syndrome. Genetics in Medicine, 14(1), 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan H, Christudoss P, Mickey K, Tessman R, Ni H. m., Swerdlow R, & Krishnamurthy P (2017). Arsenite Effects on Mitochondrial Bioenergetics in Human and Mouse Primary Hepatocytes Follow a Nonlinear Dose Response. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidzon G, Mancuso M, Ferraris S, Quinzii C, Hirano M, Peters HL, . . . DiMauro S (2005). POLG mutations and Alpers syndrome. Annals of Neurology, 57(6), 921–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divakaruni AS, & Brand MD (2011). The regulation and physiology of mitochondrial proton leak. Physiology, 26(3), 192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dranka BP, Benavides GA, Diers AR, Giordano S, Zelickson BR, Reily C, . . . Zhang J (2011). Assessing bioenergetic function in response to oxidative stress by metabolic profiling. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 51(9), 1621–1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echtay KS, Roussel D, St-Pierre J, Jekabsons MB, Cadenas S, Stuart JA, . . . Pickering S (2002). Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Nature, 415(6867), 96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiholzer U, Meinhardt U, Rousson V, Petrovic N, & Schlumpf M (2008). Developmental profiles in young children with Prader–Labhart–Willi syndrome: effects of weight and therapy with growth hormone or coenzyme Q10. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A, 146(7), 873–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filosto M, Mancuso M, Nishigaki Y, Pancrudo J, Harati Y, Gooch C, . . . Shanske S (2003). Clinical and genetic heterogeneity in progressive external ophthalmoplegia due to mutations in polymerase γ. Archives of Neurology, 60(9), 1279–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higdon AN, Landar A, Barnes S, & Darley-Usmar VM (2012). The electrophile responsive proteome: Integrating proteomics and lipidomics with cellular function. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling, 17(11), 1580–1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JO, Kaler M, Spetalnick B, Reed G, & Butler MG (1990). Resting metabolic rate in Prader-Willi syndrome. Dismorphology and Clinical Genetics, 4(1), 27–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm VA, Cassidy SB, Butler MG, Hanchett JM, Greenswag LR, Whitman BY, & Greenberg F (1993). Prader-Willi syndrome: consensus diagnostic criteria. Pediatrics, 91(2), 398–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney FJ, & Butler MG (1989a). Characterization of obesity in the Prader- Labhart- Willi syndrome: Fatness patterning. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 3(3), 294–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney FJ, & Butler MG (1989b). The developing role of anthropologists in medical genetics: Anthropometric assessment of the Prader‐Labhart‐Willi syndrome as an illustration. Medical Anthropology, 10(4), 247–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls DG, Darley-Usmar VM, Wu M, Jensen PB, Rogers GW, & Ferrick DA (2010). Bioenergetic profile experiment using C2C12 myoblast cells. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVE(46). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone S, Lotti F, Geronzi U, Guidoni E, Longini M, & Buonocore G (2016). Oxidative stress in cancer-prone genetic diseases in pediatric age: the role of mitochondrial dysfunction. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoeller D, Levitsky L, Bandini L, Dietz W, & Walczak A (1988). Energy expenditure and body composition in Prader-Willi syndrome. Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental, 37(2), 115–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B, Xiao H, Li F, Zeng L, & Yin Y (2015a). The profiles of mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis using extracellular flux analysis in porcine enterocyte IPEC-J2. Animal Nutrition, 1(3), 239–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan B, Xiao H, Xiong X, Wang J, Li G, Yin Y, . . . Wu G (2015b). L-arginine improves DNA synthesis in LPS-challenged enterocytes. Frontiers in Bioscience (Landmark Ed), 20, 989–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan EP, McGreal SR, Graw S, Tessman R, Koppel SJ, Dhakal P, . . . Koestler DC (2017). Sustained O-GlcNAcylation reprograms mitochondrial function to regulate energy metabolism. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 292(36), 14940–14962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DC (2005). A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annual Review of Genetics, 39, 359–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi PG, Su H, Ghimbovschi S, Fan W, Coskun PE, Nalbandian A, . . . Wallace DC (2013). Differential gene expression reveals mitochondrial dysfunction in an imprinting center deletion mouse model of Prader–Willi syndrome. Clinical and Translational Science, 6(5), 347–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelickson BR, Benavides GA, Johnson MS, Chacko BK, Venkatraman A, Lander A, . . . Darley-Usmar VM (2011). Nitric oxide and hypoxia exacerbate alcohol-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in hepatocytes. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta, 1807(12), 1573–1582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]