Abstract

The nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway is critical for removing damage induced by ultraviolet (UV) light and other helix-distorting lesions from cellular DNA. While efficient NER is critical to avoid cell death and mutagenesis, NER activity is inhibited in chromatin due to the association of lesion-containing DNA with histone proteins. Histone acetylation has emerged as an important mechanism for facilitating NER in chromatin, particularly acetylation catalyzed by the Spt-Ada-Gcn5 acetyltransferase (SAGA); however, it is not known if other histone acetyltransferases (HATs) promote NER activity in chromatin. Here, we report that the essential Nucleosome Acetyltransferase of histone H4 (NuA4) complex is required for efficient NER in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Deletion of the non-essential Yng2 subunit of the NuA4 complex causes a general defect in repair of UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) in yeast; in contrast, deletion of the Sas3 catalytic subunit of the NuA3 complex does not affect repair. Rapid depletion of the essential NuA4 catalytic subunit Esa1 using the anchor-away method also causes a defect in NER, particularly at the heterochromatic HML locus. We show that disrupting the Sds3 subunit of the Rpd3L histone deacetylase (HDAC) complex rescued the repair defect associated with loss of Esa1 activity, suggesting that NuA4-catalyzed acetylation is important for efficient NER in heterochromatin.

Keywords: NER, Esa1, chromatin, DNA repair, histone acetylation

1. Introduction

Cellular DNA is damaged by a variety of endogenous and exogenous sources, inducing DNA lesions that must be efficiently repaired in order to maintain genomic stability and avoid mutagenesis. The nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway is responsible for the repair of DNA helix-distorting lesions, such as cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers (CPDs) and 6–4 photoproducts (6–4PPs) induced by UV radiation [1, 2]. CPD lesions on the transcribed strand of genes are rapidly removed by the transcription-coupled NER (TC-NER) pathway, which is initiated when RNA polymerase II stalls at these lesions during transcription [3–5]. CPD lesions located elsewhere in the genome are repaired by the global genome NER (GG-NER) pathway [6]. CPD removal by the GG-NER pathway generally occurs more slowly than TC-NER, in part because damage recognition factors in GG-NER (i.e., DDB2 and XPC in humans, Rad7/Rad16 and Rad4 in yeast) must contend with lesions residing in chromatin [6–8].

The compaction of eukaryotic DNA into chromatin is a double-edged sword for DNA damage and repair. Chromatin structure can protect DNA from certain types of lesions (e.g., UV-induced 6–4PPs [9, 10]) and plays important roles in DNA damage signaling [11, 12]; however, this organization can also restrict accessibility of repair factors to DNA. The basic subunit of chromatin is the nucleosome, which is comprised of ~147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octamer of histone proteins [13]. Nucleosomes significantly reduce NER efficiency in vitro [7, 14] and in vivo [15–17], indicating that even the lowest level of chromatin organization presents a significant barrier to repair.

Chromatin structure is dynamically modulated by histone post-translational modifications, which have been implicated in regulating DNA repair in chromatin [18, 19]. The best-studied histone modification associated with NER is histone acetylation (reviewed in [8, 19, 20]). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, histones H3 and H4 are rapidly acetylated in response to UV irradiation [21]. This response is mediated in part by the Gcn5 acetyltransferase, which is recruited to chromatin in response to UV irradiation [22] and has been shown to be required for efficient repair of UV damage at individual yeast loci (e.g., MFA2 promoter [21, 23]). A recent genome-wide analysis indicates that a gcn5 mutant alters the distribution of repair rates at many yeast genes [24].

However, it is not known whether other histone acetyltransferases are important for efficient NER activity in yeast chromatin. Possible candidates include Sas3 and Esa1, which function as the catalytic subunits of the Nucleosome Acetyltransferase of histone H3 (NuA3) and Nucleosome Acetyltransferase of histone H4 (NuA4) complexes, respectively [25]. Esa1 is a particularly intriguing candidate, as it is the only histone acetyltransferase that is essential for yeast viability [26], and because partial loss of function mutants in Esa1, as well as other NuA4 subunits (e.g., Yng2), are hypersensitive to DNA damage and DNA replication stress [27–29]. Esa1 primarily acetylates lysine residues in the N-terminal tails of histones H2A, H2A.Z, and H4 [25], but can also acetylate non-histone proteins [30, 31]. In addition to NuA4, Esa1 also serves as the catalytic subunit of the Piccolo-NuA4 complex, which functions to maintain basal levels of histone acetylation throughout the genome [32]. Esa1 and its human homologue TIP60 have been shown to be important for double-strand break repair in yeast and human cells, respectively [27, 33, 34]. Additionally, the NuA4 complex has been shown to play a role in DNA damage bypass via translesion synthesis [35] and postreplication repair [36]. However, it is not known if NuA4 (or NuA3) is important for NER.

In this study, we investigated whether the NuA3 and NuA4 acetyltransferases are important for repair of UV-induced DNA lesions in yeast chromatin. Here, we show that deletion or conditional depletion of NuA4 subunits in yeast cause a striking decrease in repair of UV-induced lesions, particularly at heterochromatic loci. Furthermore, we demonstrate that this repair defect can be rescued by a mutant that disrupts the function of the Rpd3L histone deacetylase complex, highlighting the importance of NuA4-mediated histone acetylation dynamics in NER.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Yeast strains and plasmids

Yeast cells were grown in YPD (yeast extract peptone dextrose) or SC (synthetic complete) media. Anchor-away strains were constructed using the CRIPSR method [37] and PCR product derived from pfa6a-FRB-his3MX6 (gift from Dr. Frank Holstege). Detailed information about yeast strains and plasmids can be found in Supplemental Table S1 and S2.

2.2. Western Blotting

Yeast whole cell extracts were isolated from yeast cells using 0.1M NaOH and boiling in 1x SDS page buffer, as previously described [38], analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (typically 15% acrylamide), and transferred to PVDF membrane. Blots were probed using anti-acetyl H4 (Upstate), anti-GAPDH (ThermoFisher), with corresponding secondary antibodies.

2.3. Viability after rapamycin treatment

For spotting assays, cells were grown to mid-log phase in SC media. Serial dilutions of the culture were spotted onto SC media alone or SC media containing 1μg/mL rapamycin, and pictures were taken after 3–4 days. For the growth curves, cells were grown in YPD media and OD600 measurements were taken at the indicated time points after addition of rapamycin (time 0). Concurrent with the growth curve assays, aliquots were taken at the indicated time points after rapamycin treatment to measure cell viability on plates. Using the OD600 measurement, cell concentration was calculated, and approximately 100 cells were plated on complete media in the absence of rapamycin. Colony formation was counted after 3 days at 30°, and normalized to the 0 hr timepoint. Graphs indicate the mean and SEM of 3 independent replicates.

2.4. Global DNA repair assay

Alkaline gel analysis was conducted as previously described [39]. For anchor-away experiments, early log phase cells were treated with 1μg/ml rapamycin for 3 hours. The cell cultures were spun down and resuspended in water and then exposed to 100 J/m2 of UV light (primarily 254nm) or mock treated for “No” UV control. Following UV irradiation, cells were resuspended in YPD (with 1μg/mL rapamycin if applicable) and incubated at 30˚C for repair. Aliquots were taken at each repair time point and frozen at −80°C. Genomic DNA was isolated by bead beating the cell pellets in 200μL lysis buffer (2% Triton-X 100, 1%SDS, 100mM NaCl, 10mM Tris-Cl pH8, 1mM Na2EDTA) and 300μL Phenol-Cholorform-Isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1). After addition of 300μL TE pH8, samples were centrifuged and DNA from the aqueous layer was precipitated in ethanol. DNA pellets were resuspended in TE pH 8 +0.2mg/mL RNaseA and incubated at 37º for 15 minutes before further processing [40]. Equivalent aliquots of DNA were treated or not treated with T4 endonuclease V (Epicentre or gift of Dr. Steven Roberts) and resolved by alkaline gel electrophoresis. After neutralization and staining with Sybr Gold (Invitrogen), gels were imaged using the Typhoon FLA 7000 (GE Healthcare) and analyzed using ImageQuant 5.2 (Molecular Dynamics) by calculating the ensemble average of each lane corrected by the no enzyme control lane to determine the number of CPDs/kb [41]. Percent repair was calculated by normalizing the number of CPDs/kb to the 0 hr time point (0%). Graphs represent the mean and SEM of at least 3 independent experiments.

2.5. Site-specific DNA repair assay

Yeast cultures were grown, UV-irradiated (100 J/m2), and harvested as for the global assay. Genomic DNA was isolated as described above, then treated with restriction enzymes (EcoRI+EcoRV for GAL10, PvuII+BsaHI for HML, DraI for RPB2) in supplied buffer (NEB) to release the DNA fragment corresponding to each genomic locus. DNA was purified using Phenol-Cholorform-Isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and ethanol precipitated before being digested with T4 endonuclease V. DNA fragments were resolved by alkaline gel electrophoresis, then transferred to a nylon membrane. Regionspecific probes were created using region-specific PCR products amplified from yeast genomic DNA and were radiolabeled using the Prime-It II Random Primer Labeling Kit (Stratagene) and α−32P dATP (Perkin-Elmer). Oligonucleotide primers to amplify HML probe were 5’-CACTGCTCTTTTCTGTGTTCCA-3’ and 5’-GCATTAGAGAAATTTCGCATAGCAA-3’; primers for the GAL10 and RPB2 probes were the same as previously described [42]. Autoradiograms were detected using the Typhoon FLA 7000 (GE Healthcare) and quantified using ImageQuant as previously described [42]. We analyzed repair at 0, 1, 2, and 3 hr time points for each locus, with the exception of RPB2. There was a similar trend in repair at RPB2 for the WT and Esa1-AA strains at 3 hr repair, but this time point often had lower overall signal, and so was not analyzed further. Graphs represent the mean and SEM of at least 3 independent replicate experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Deletion of a non-essential subunit of the NuA4 complex impairs NER in yeast

To investigate whether the NuA3 or NuA4 acetyltransferase complexes are required for efficient NER, we analyzed repair of UV-induced CPD lesions in yeast mutants that compromised the activity of either complex. We first tested whether deletion of SAS3, which encodes the catalytic subunit of NuA3, affected repair of CPD lesions in yeast. The sas3Δ mutant and wild-type (WT) control strains were irradiated with 100 J/m2 dose of UV-C light (primarily 254 nm), and allowed to repair for various times. Repair of CPD lesions in isolated genomic DNA at various repair times was monitored using the published T4 endonuclease V digestion and alkaline gel electrophoresis assay [39, 43]. Using this assay, we found no significant difference in repair of CPDs in bulk genomic DNA at any repair time point (i.e., 1, 2, or 3 hours (hr) following UV irradiation) in the sas3Δ mutant relative to WT (see Figure 1A,B). These results indicate that NuA3 activity is largely dispensable for NER activity in yeast chromatin. Deletion of GCN5, which encodes the catalytic subunit of the SAGA complex, causes a significant defect in the repair of CPD lesions at the final 3 hr repair time point (Figure 1C, P < 0.05), but not at early time points. A previous study has indicated that Gcn5 is required for efficient NER activity in yeast chromatin [24]; our data suggest that Gcn5 may be particularly important for slow-repairing regions of genomic chromatin.

Figure 1.

Effects of deletion mutants in non-essential subunits of SAGA (gcn5Δ), NuA4 (yng2Δ), and NuA3 (sas3Δ) on repair of UV-induced CPD lesions in yeast. (A) Representative alkaline gels of genomic DNA isolated at the indicated repair time points following UV irradiation (100 J/m2), following treatment with or without (+/−) T4 endonuclease V. T4 endonuclease V creates single-stranded DNA nicks at CPD lesions, which were resolved on denaturing alkaline gels. (B-D) Quantification of CPD repair in mutant and wild-type (WT) yeast strains. The percentage of CPD lesions removed at each time point is plotted as the mean ± SEM of at least 3 independent experiments. P values were calculated using an unpaired t-test. *P ≤ 0.05.

As the NuA4 catalytic subunit Esa1 is essential for yeast viability [26], we characterized a deletion of the non-essential NuA4 subunit Yng2, which is required for NuA4/Esa1 histone acetyltransferase activity in chromatin [32, 44, 45]. Western blot analysis using a pan-H4 acetylation antibody confirmed that histone H4 acetylation levels are lower in the yng2Δ mutant relative to WT (Figure S1), consistent with a defect in NuA4-catalyzed histone acetylation. Using our repair assay, we found that CPD repair in bulk genomic DNA was lower in the yng2Δ mutant relative to WT at every repair time point (i.e., 1, 2, and 3 hr following UV irradiation). There was an overall ~2fold reduction in repair in the yng2Δ mutant relative to WT after 3 hr (Figure 1D), similar in magnitude to the repair defect observed in the gcn5Δ mutant at the same time point. These data suggest that the NuA4 acetyltransferase activity is required for efficient repair of UV lesions in yeast chromatin.

3.2. Rapid nuclear depletion of Esa1 using a chemical genomics approach confirms that NuA4 activity is important for NER

Since NuA4 is an important regulator of yeast gene expression, it is possible that the yng2Δ mutant might indirectly affect repair by decreasing the expression of key NER genes. However, none of the genes involved in NER are significantly decreased in expression in a published yng2Δ gene expression data set [46], indicating that the repair defect is unlikely to be due to expression changes in the NER machinery.

To confirm the role of the NuA4 complex in regulating NER, and avoid potential secondary effects due to disrupting NuA4 activity, we employed a chemical genomics approach known as anchor-away [47] to rapidly deplete NuA4 activity from the nucleus in yeast. Esa1 was tagged on its N-terminus with FRB (FKBP rapamycin-binding domain) in a yeast strain with the ribosomal subunit RPL13A tagged with FKBP (FK506- and rapamycin-binding protein). Addition of rapamycin causes the FRB and FKBP tags to dimerize, leading to rapid nuclear depletion of the FRB-tagged protein, due to its export to the cytoplasm (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Rapid nuclear depletion of FRB-tagged Esa1 (AA-Esa1) using the anchor-away system. (A) Schematic diagram of the anchor-away system for rapidly depleting proteins from the nucleus. (B) Histone H4 acetylation is significantly diminished following anchor-away depletion of Esa1, based on western blot analysis of AA-Esa1 or isogenic wild type cells before and after 3 hours rapamycin treatment using a panH4acetyl antibody. Where indicated, a plasmid containing wild type Esa1 (+pEsa1) or mutant Esa1 (+pEsa1 E338Q) was co-expressed. GAPDH was used as a loading control. (C) Ten-fold serial dilutions of yeast spot onto synthetic complete (SC) or SC+ 1μg/mL rapamycin plates. (D) OD600 measurements at the indicated time points following treatment with rapamycin. (E) Cultures treated with rapamycin for the indicated times were plated onto complete media and resultant colonies were counted and normalized to the untreated control. (D-E) represent the mean and SEM of 3 independent experiments.

Rapamycin treatment of a yeast strain containing anchor-away tagged Esa1 (AA-Esa1) caused a rapid and severe decrease in cellular histone H4 acetylation levels. Western blot analysis indicated that pan-H4 acetylation was significantly decreased following 3 hr of rapamycin treatment in the AA-Esa1 strain (Figure 2B). In contrast, rapamycin treatment had no effect on H4 acetylation in the isogenic untagged strain (WT, see Figure 2B). The decrease in H4 acetylation due to anchor-away depletion of Esa1 could be rescued by expression of untagged wild-type Esa1 (Figure 2B), but not by expression of a catalytically inactive Esa1 mutant (Esa1-E338Q), indicating that histone H4 acetylation is decreased because of Esa1 depletion. Since Esa1 is essential for growth, we also measured cell growth and viability following anchor-away depletion of Esa1. Chronic incubation with rapamycin caused a significant growth defect in the AA-Esa1 strain (Figure 2C). However, there was no difference in cell growth or viability in AA-Esa1 relative to the WT control over a 6 hr time window following rapamycin treatment (Figure 2D-E), indicating that the decrease in H4 acetylation in the AA-Esa1 strain following 3 hr rapamycin treatment was not a secondary effect of inhibition of cell growth or cell death.

To characterize the role of Esa1 in NER, we measured the repair of UV-induced CPDs following rapid anchor-away depletion of Esa1, using the repair assay described above. The AA-Esa1 strain was pretreated with rapamycin for 3 hr prior to UV irradiation, in order to deplete Esa1 acetyltransferase activity from the nucleus. Following UV-irradiation, cells were allowed to repair UV-induced DNA damage in rapamycin-containing media. As a control, repair of CPDs was measured in the untagged WT strain that had been treated in a similar manner. We observed a striking global defect in repair of CPD lesions in the rapamycin-treated AA-Esa1 strain (Figure 3A-B). There was a significant decrease in CPD repair at the 2 and 3 hr repair time points relative to the untagged WT control, with an overall ~2-fold decrease in repair after 3 hours. The repair defect due to Esa1 anchor-away depletion was very similar to the repair defect in the yng2Δ strain, confirming that NuA4 activity is required for efficient NER. There was no significant change in repair activity in the AA-Esa1 strain in the absence of rapamycin (Figure 3C), indicating that this repair defect was due to rapamycin-mediated nuclear depletion of AA-Esa1.

Figure 3.

Anchor-away depletion of Esa1 causes a significant defect in NER of UV-induced CPD lesions. A) Representative alkaline gels of genomic DNA isolated at the indicated repair time points following UV irradiation (100 J/m2), following treatment with or without (+/−) T4 endonuclease V. Cells were preincubated with 1μg/ml rapamycin for 3 hours prior to UV irradiation to deplete Esa1 from the nucleus (AA-Esa1 strain), and were further incubated with rapamycin during the repair time course. A control strain (WT), in which Esa1 was not anchor-away tagged, was treated similar. (B-C) Quantification of %CPD repair from alkaline gels analyzing repair in the control (WT) or Esa1 anchor-away tagged (Esa1-AA) strain, treated with (B) or without (C) rapamycin. The mean ± SEM is depicted for a minimum of 3 independent replicates. P values were calculated for using an unpaired t-test. *P ≤ 0.05.

3.3. NuA4 is important for repair of CPD lesions in the silent HML locus

To determine whether Esa1 is required for NER in different chromatin contexts, we analyzed repair of CPD lesions in yeast at the RPB2 and HML loci [42, 48, 49]. The RPB2 locus, which encodes the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II, is constitutively expressed in yeast, while the HML locus is comprised of silent heterochromatin that is hypoacetylated [50]. To examine repair at these loci in the absence of nuclear Esa1, we pre-treated the AA-Esa1 strain with rapamycin for 3 hr prior to UV irradiation, and continued treating with rapamycin during the subsequent repair time course.

Anchor-away depletion of Esa1 caused a striking defect in repair at the silent HML locus. CPD repair was significantly decreased at the 2 and 3 hr time points (Figure 4A-B), with a ~3-fold decrease in repair relative to the WT control at 2 hr (P = 0.019). In contrast, there was no significant effect of Esa1 depletion on repair at the transcriptional active RPB2 locus (Figure 4C-D). These data suggest that Esa1 may play a particularly important role in facilitating NER in silent heterochromatin, which is normally hypoacetylated. We also tested whether Esa1 is required for repair of UV lesions in the GAL10 locus, which is comprised of repressed chromatin when yeast are grown in glucose media [42, 48, 49]. Upon anchor-away Esa1 depletion, CPD repair at the repressed GAL10 locus was decreased relative to the WT control at the 3 hr repair time point (Figure S2, P = 0.0029). These results indicate that Esa1 is important for repair in repressed and silent chromatin in yeast.

Figure 4.

Esa1 anchor-away depletion causes a significant repair defect at the heterochromatic HML locus, but not the actively transcribed RPB2 gene. Southern blot analysis for site specific NER of UV-induced CPD lesions at HML (A, B) and RPB2 (C, D) when Esa1 is conditionally depleted from the nucleus in the anchor-away system (see Figure 3 above). Quantification of % CPD repair at each locus is depicted as the mean and SEM for at least three independent replicates. P values were calculated using an unpaired t-test. Mean ± SEM is depicted. *P ≤ 0.05.

3.4. Holo-NuA4 and Piccolo-NuA4 complexes both contribute to NER

Esa1 and Yng2 are integral subunits of two distinct histone acetyltransferase complexes: the NuA4 complex (i.e., holo-NuA4) and the smaller Piccolo-NuA4 complex, which contains only the Esa1, Yng2, Epl1, and Eaf6 subunits (Figure 5A). To characterize the contributions of these distinct Yng2- and Esa1-containing complexes, we measured repair of CPD lesions in a yeast strain lacking the NuA4-specific subunit Eaf1. The eaf1Δ mutant specifically disrupts the integrity of the NuA4 complex, but has no effect on Piccolo-NuA4 structure or activity [45, 51, 52]. There was a decrease in repair of CPD lesions in the eaf1Δ mutant relative to WT, with a ~1.5-fold reduction in repair at 3 hr (Figure 5B-C). The decrease in repair at 3 hr was not statistically significant using a conventional unpaired t-test (P = 0.11), in part because of the relatively high variability among replicates. Using a paired t-test to account for this variability, we found that repair at 3 hr was consistently decreased in the eaf1Δ mutant relative to WT (P = 0.03). These results indicate that the NuA4-specific Eaf1 subunit has a marginal role in the repair of CPD lesions in yeast, to a lesser extent than Yng2 and Esa1.

Figure 5.

Deletion of the Eaf1 component of the NuA4 complex causes a marginal defect in repair of CPD lesions. (A) Schematic representation of the NuA4 complex with the Piccolo NuA4 subcomplex shown in orange and the scaffolding component of the NuA4 complex shown in green. The subunits analyzed in this study (Yng2, Esa1, Eaf1) are highlighted with darker coloring. Diagram adapted from [45]. (B-C) NER phenotype of the eaf1Δ mutant. (B) A representative alkaline gel of CPD repair following UV irradiation. (C) Quantification of % repair for a minimum of 3 independent replicates, depicted as mean ± SEM.

3.5. Repair defect due to loss of Esa1 activity can be rescued by inactivating the Rpd3L complex

Previous studies have implicated the Rpd3L and Set3/Hos2 histone deacetylase complexes as opposing the activity of NuA4/Esa1. Deletion of the Sds3 subunit of Rpd3L histone deacetylase complex rescues the lethality of esa1Δ mutant [53, 54], while deletion of Hos2 rescues many of the DNA damage sensitivities of the esa1 partial loss-of-function mutants [55]. Hence, we tested whether the NER defect associated with mutations in NuA4 subunits could be rescued by a compensatory loss-of-function mutation in either SDS3 or HOS2.

The esa1Δsds3Δ double mutant strain was viable, consistent with a previous report [54], so we tested whether the NER defect associated with loss of Esa1 acetyltransferase activity is rescued by a compensatory deletion of the Sds3 subunit of the Rpd3L HDAC complex. The sds3Δ mutant alone did not significantly affect repair of CPD lesions relative to the WT control following UV irradiation (Figure S3). However, the sds3Δ mutant rescued the repair defect associated with loss of Esa1 activity, as the esa1Δsds3Δ double mutant strain had similar repair efficiency of CPD lesions as the WT control strain (Figure 6A,B).

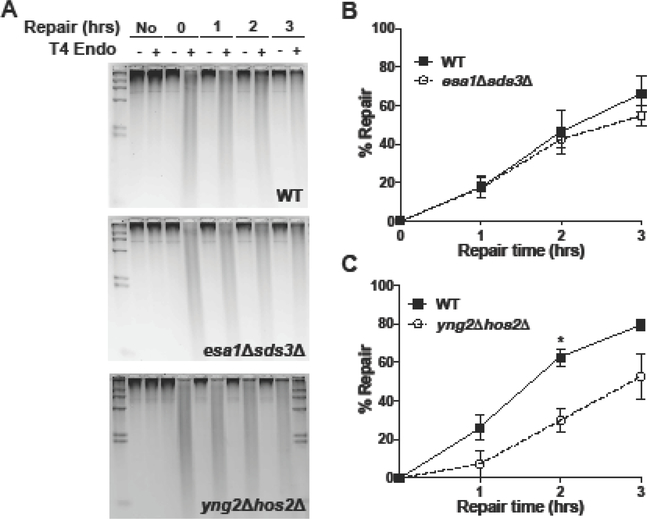

Figure 6.

Disruption of the Rpd3L HDAC complex (i.e., sds3Δ), but not the Hos2 HDAC, suppresses the repair defect in NuA4 mutant cells. (A) Representative alkaline gels analyzing repair of CPD lesions in WT, esa1Δsds3Δ, and yng2Δhos2Δ mutants. (B-C) Quantification of NER alkaline gel analysis of HAT/HDAC double mutants esa1Δsds3Δ and yng2Δhos2Δ. Quantification represents the mean ± SEM of at least three independent replicates. P values were calculated using an unpaired t-test. *P ≤ 0.05.

Since deletion of HOS2 does not rescue esa1Δ lethality [54], we tested whether a hos2Δ mutant could rescue the repair defect observed when YNG2, a non-essential subunit of NuA4 that is required for Esa1 acetyltransferase activity, is deleted (see Figure 1). The hos2Δ mutant alone caused a slight increase in repair of CPD lesions relative to the WT control (Figure S4), particularly at the 1 hr time point (P < 0.05), suggesting that Hos2 may function to repress NER in chromatin by deacetylating histones. However, the yng2Δhos2Δ double mutant had a significant repair defect following UV irradiation, as CPD repair was considerably lower in the yng2Δhos2Δ double mutant relative to the WT control (Figure 6C), particularly at the 2 hr time point (P = 0.0044). The repair defect in the yng2Δhos2Δ double mutant was very similar to the defect seen in the yng2Δ mutant alone, indicating that deletion of the Hos2 HDAC does not rescue the repair defect caused by loss of NuA4 acetyltransferase activity.

4. Discussion

While histone acetylation by the Gcn5 subunit of the SAGA complex is known to play an important role in the repair of UV damage by the NER pathway [8, 20], the potential roles of other yeast HAT complexes in NER were previously unclear. Here, we show that the essential NuA4 HAT complex is important for efficient repair of UV-induced CPD lesions in yeast chromatin. Deletion of the nonessential Yng2 subunit of NuA4, which is required for acetylation of nucleosomal histones [32, 44, 45], causes a global defect in NER of UV-induced CPD lesions. This defect in repair is unlikely to be due to Yng2-dependent changes in gene expression, since the yng2Δ mutant does not downregulate the expression of known NER genes [46]. Moreover, rapid nuclear depletion of the Esa1 catalytic subunit of NuA4 using the anchor-away strategy causes a similar repair defect. Taken together, our data indicate that NuA4 likely plays a direct role in facilitating NER in chromatin; however, it will be important to test in future studies whether NuA4 is directly recruited in response to UV damage.

Yng2 and Esa1 are subunits of two distinct NuA4 complexes: the holo-NuA4 and Piccolo-NuA4 complexes, both of which can acetylate nucleosomal histones in vivo. Holo-NuA4 is targeted to specific genomic loci through its recruitment module, which interacts with transcriptional activators as well as DNA damage-associated signals [45, 56–58]. In contrast, Piccolo-NuA4 functions in an untargeted fashion to maintain basal levels of acetylated histones throughout the genome [32]. Our data indicate that an eaf1Δ mutant, which specifically disrupts the holo-NuA4 complex, but does not affect Piccolo-NuA4 integrity or activity [45, 51, 52], causes a marginal decrease in repair of UV-induced CPD lesions. The eaf1Δ strain has also been reported to have elevated sensitivity to UV damage [59], consistent with the model that holo-NuA4 is required for efficient NER of UV-induced CPD lesions. However, the repair defect in the eaf1Δ strain is less severe than the yng2Δ mutant, indicating the Piccolo-NuA4 may also function in NER.

Analysis of CPD repair at individual yeast loci indicates that NuA4 is particularly important for repair at the heterochromatic HML and repressed GAL10 loci, but not at the actively transcribed RPB2 locus. NuA4 normally acetylates histones associated with gene promoters and actively transcribed coding regions [57, 60–62], but this activity appears to be dispensable for efficient repair, at least at the actively transcribed RPB2 locus. In contrast, NuA4 activity is essential for efficient repair at the silent HML locus, even though histones at the HML locus are not thought to be acetylated by NuA4 under normal conditions (i.e., in the absence of DNA damage). An implication of these findings is that NuA4 may play a particularly important role in facilitating NER in repressive and hypoacetylated chromatin, even though such chromatin domains are normally not targets of NuA4 activity.

This conclusion may explain our genetic data analyzing which HDACs can rescue the repair defects of NuA4 mutants. The Hos2 HDAC is a subunit of the Set3 complex that is important for deacetylation of histones located in 5’ coding regions and certain promoters [63–65]. A hos2Δ mutant can partially rescue H4 acetylation levels [55], but not the NER defect in NuA4 mutants (i.e., yng2Δ). Presumably, this is because NuA4 is largely dispensable for repair at actively transcribed coding regions (such as RPB2), where Hos2 is targeted. In contrast, the sds3Δ mutant, which disrupts the Rpd3L HDAC complex, results in WT levels of repair in an esa1 mutant strain, even though it does not rescue cellular H4 acetylation levels in this strain (see Figure S1 [54]). This could be explained by the observation that the Sds3-containing Rpd3L complex has an important role in regulating gene silencing at the yeast silent mating loci [66], since we observed the most severe repair defect in the Esa1-depleted strain at the silent HML locus. Alternatively, the Rpd3L complex could affect the acetylation state of non-histone proteins that may be an important target of NuA4 activity during NER.

Our finding that NuA4 is important for efficient NER in chromatin has potentially important implications for the role of the human NuA4/TIP60 complex in carcinogenesis and chemotherapeutic resistance. The catalytic subunit of the human NuA4 complex is TIP60, the human homolog of Esa1. TIP60 is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor that is frequently down-regulated and associated with carcinogenesis in various cancer types, including malignant melanoma and breast cancer [67, 68]. Moreover, the Inhibitor of Growth 3 (ING3) gene, which encodes a subunit of the human NuA4/TIP60 complex and is homologous to the yeast Yng2 subunit, is frequently decreased in expression in melanoma and head and neck cancers [69, 70]. Our data suggest that decreased NuA4 activity in human cells may stimulate carcinogenesis by down-regulating the activity of the NER pathway, which repairs potentially mutagenic DNA lesions. Tip60 overexpression has also been linked to cellular resistance to the chemotherapy drug cisplatin [71], which generates DNA lesions repaired by the NER pathway. We hypothesize that TIP60 overexpression may promote cisplatin resistance by directly stimulating NER of cisplatin DNA lesions. It will be important in future studies to test this mechanism, as well as to determine whether modulation of HDAC activity might compensate for TIP60-dependent alterations in NER activity and cisplatin resistance.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

NuA4 acetyltransferase complex is required for nucleotide excision repair (NER)

Deletion or depletion of NuA4 subunits cause a global defect in NER in yeast

NuA4 is particularly important for efficient NER in silent heterochromatin

NER defect can be suppressed by a mutation in the Rpd3L deacetylase complex

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Smerdon and Dr. Peng Mao for helpful comments and suggestions. We thank Dr. Steven Roberts for providing purified T4 endonuclease V enzyme, Dr. Frank Holstege for providing anchor-away yeast strains and plasmids, Andrea Connor for help with constructing yeast strains, and Nicole Reinsch for technical support. Funding for this research was provided by grants from NIEHS (R01ES002614, R01ES028698 and R21ES027937).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T, DNA repair and Mutagenesis, 2nd ed., ASM Press, Washington, D.C., 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Marteijn JA, Lans H, Vermeulen W, Hoeijmakers JH, Understanding nucleotide excision repair and its roles in cancer and ageing, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 15 (2014) 465–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hanawalt PC, Spivak G, Transcription-coupled DNA repair: two decades of progress and surprises, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 9 (2008) 958–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vermeulen W, Fousteri M, Mammalian transcription-coupled excision repair, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 5 (2013) a012625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Li S, Transcription coupled nucleotide excision repair in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: The ambiguous role of Rad26, DNA repair, 36 (2015) 43–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Scharer OD, Nucleotide excision repair in eukaryotes, Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 5 (2013) a012609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu X, In vitro chromatin templates to study nucleotide excision repair, DNA repair, 36 (2015) 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Waters R, van Eijk P, Reed S, Histone modification and chromatin remodeling during NER, DNA repair, 36 (2015) 105–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Gale JM, Smerdon MJ, UV induced (6–4) photoproducts are distributed differently than cyclobutane dimers in nucleosomes, Photochemistry and photobiology, 51 (1990) 411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mitchell DL, Nguyen TD, Cleaver JE, Nonrandom induction of pyrimidine-pyrimidone (6–4) photoproducts in ultraviolet-irradiated human chromatin, The Journal of biological chemistry, 265 (1990) 5353–5356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Papamichos-Chronakis M, Peterson CL, Chromatin and the genome integrity network, Nature reviews. Genetics, 14 (2013) 62–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dantuma NP, van Attikum H, Spatiotemporal regulation of posttranslational modifications in the DNA damage response, The EMBO journal, 35 (2016) 6–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ, Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution, Nature, 389 (1997) 251260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hara R, Mo J, Sancar A, DNA damage in the nucleosome core is refractory to repair by human excision nuclease, Molecular and cellular biology, 20 (2000) 9173–9181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nag R, Smerdon MJ, Altering the chromatin landscape for nucleotide excision repair, Mutation research, 682 (2009) 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mao P, Smerdon MJ, Roberts SA, Wyrick JJ, Chromosomal landscape of UV damage formation and repair at single-nucleotide resolution, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113 (2016) 9057–9062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hu J, Selby CP, Adar S, Adebali O, Sancar A, Molecular mechanisms and genomic maps of DNA excision repair in Escherichia coli and humans, The Journal of biological chemistry, 292 (2017) 15588–15597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].House NC, Koch MR, Freudenreich CH, Chromatin modifications and DNA repair: beyond double-strand breaks, Front Genet, 5 (2014) 296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mao P, Wyrick JJ, Emerging roles for histone modifications in DNA excision repair, FEMS yeast research, 16 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Waters R, Evans K, Bennett M, Yu S, Reed S, Nucleotide excision repair in cellular chromatin: studies with yeast from nucleotide to gene to genome, International journal of molecular sciences, 13 (2012) 11141–11164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yu Y, Teng Y, Liu H, Reed SH, Waters R, UV irradiation stimulates histone acetylation and chromatin remodeling at a repressed yeast locus, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102 (2005) 8650–8655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Yu S, Teng Y, Waters R, Reed SH, How chromatin is remodelled during DNA repair of UV-induced DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, PLoS genetics, 7 (2011) e1002124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Teng Y, Yu Y, Waters R, The Saccharomyces cerevisiae histone acetyltransferase Gcn5 has a role in the photoreactivation and nucleotide excision repair of UV-induced cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers in the MFA2 gene, Journal of molecular biology, 316 (2002) 489–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Yu S, Evans KE, van Eijk P, Bennett M, Webster RM, Leadbitter M, Teng Y, Waters R, Jackson SP, Reed SH, Global genome nucleotide excision repair is organized into domains that promote efficient DNA repair in chromatin, Genome research, 26 (2016) 1376–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lee KK, Workman JL, Histone acetyltransferase complexes: one size doesn’t fit all, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 8 (2007) 284–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Clarke AS, Lowell JE, Jacobson SJ, Pillus L, Esa1p is an essential histone acetyltransferase required for cell cycle progression, Molecular and cellular biology, 19 (1999) 2515–2526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bird AW, Yu DY, Pray-Grant MG, Qiu Q, Harmon KE, Megee PC, Grant PA, Smith MM, Christman MF, Acetylation of histone H4 by Esa1 is required for DNA double-strand break repair, Nature, 419 (2002) 411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Choy JS, Kron SJ, NuA4 subunit Yng2 function in intra-S-phase DNA damage response, Molecular and cellular biology, 22 (2002) 8215–8225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Decker PV, Yu DY, Iizuka M, Qiu Q, Smith MM, Catalytic-site mutations in the MYST family histone Acetyltransferase Esa1, Genetics, 178 (2008) 1209–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mitchell L, Huard S, Cotrut M, Pourhanifeh-Lemeri R, Steunou AL, Hamza A, Lambert JP, Zhou H, Ning Z, Basu A, Cote J, Figeys DA, Baetz K, mChIP-KATMS, a method to map protein interactions and acetylation sites for lysine acetyltransferases, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110 (2013) E1641–1650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lin YY, Lu JY, Zhang J, Walter W, Dang W, Wan J, Tao SC, Qian J, Zhao Y, Boeke JD, Berger SL, Zhu H, Protein acetylation microarray reveals that NuA4 controls key metabolic target regulating gluconeogenesis, Cell, 136 (2009) 1073–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Boudreault AA, Cronier D, Selleck W, Lacoste N, Utley RT, Allard S, Savard J, Lane WS, Tan S, Cote J, Yeast enhancer of polycomb defines global Esa1dependent acetylation of chromatin, Genes & development, 17 (2003) 1415–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ikura T, Ogryzko VV, Grigoriev M, Groisman R, Wang J, Horikoshi M, Scully R, Qin J, Nakatani Y, Involvement of the TIP60 histone acetylase complex in DNA repair and apoptosis, Cell, 102 (2000) 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bennett G, Peterson CL, SWI/SNF recruitment to a DNA double-strand break by the NuA4 and Gcn5 histone acetyltransferases, DNA repair, 30 (2015) 38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Renaud-Young M, Lloyd DC, Chatfield-Reed K, George I, Chua G, Cobb J, The NuA4 complex promotes translesion synthesis (TLS)-mediated DNA damage tolerance, Genetics, 199 (2015) 1065–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].House NCM, Yang JH, Walsh SC, Moy JM, Freudenreich CH, NuA4 initiates dynamic histone H4 acetylation to promote high-fidelity sister chromatid recombination at postreplication gaps, Molecular cell, 55 (2014) 818–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Laughery MF, Hunter T, Brown A, Hoopes J, Ostbye T, Shumaker T, Wyrick JJ, New vectors for simple and streamlined CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Yeast, 32 (2015) 711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mao P, Meas R, Dorgan KM, Smerdon MJ, UV damage-induced RNA polymerase II stalling stimulates H2B deubiquitylation, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111 (2014) 12811–12816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Hodges AJ, Gallegos IJ, Laughery MF, Meas R, Tran L, Wyrick JJ, Histone Sprocket Arginine Residues Are Important for Gene Expression, DNA Repair, and Cell Viability in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Genetics, 200 (2015) 795–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Rose MD, Winston F, Hieter P, Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Course Manual, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bespalov VA, Conconi A, Zhang X, Fahy D, Smerdon MJ, Improved method for measuring the ensemble average of strand breaks in genomic DNA, Environmental and molecular mutagenesis, 38 (2001) 166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nag R, Kyriss M, Smerdon JW, Wyrick JJ, Smerdon MJ, A cassette of Nterminal amino acids of histone H2B are required for efficient cell survival, DNA repair and Swi/Snf binding in UV irradiated yeast, Nucleic acids research, 38 (2010) 14501460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Meas R, Smerdon MJ, Wyrick JJ, The amino-terminal tails of histones H2A and H3 coordinate efficient base excision repair, DNA damage signaling and postreplication repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Nucleic acids research, 43 (2015) 4990–5001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Loewith R, Meijer M, Lees-Miller SP, Riabowol K, Young D, Three yeast proteins related to the human candidate tumor suppressor p33(ING1) are associated with histone acetyltransferase activities, Molecular and cellular biology, 20 (2000) 38073816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chittuluru JR, Chaban Y, Monnet-Saksouk J, Carrozza MJ, Sapountzi V, Selleck W, Huang J, Utley RT, Cramet M, Allard S, Cai G, Workman JL, Fried MG, Tan S, Cote J, Asturias FJ, Structure and nucleosome interaction of the yeast NuA4 and Piccolo-NuA4 histone acetyltransferase complexes, Nature structural & molecular biology, 18 (2011) 1196–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Choy JS, Tobe BT, Huh JH, Kron SJ, Yng2p-dependent NuA4 histone H4 acetylation activity is required for mitotic and meiotic progression, The Journal of biological chemistry, 276 (2001) 43653–43662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Haruki H, Nishikawa J, Laemmli UK, The anchor-away technique: rapid, conditional establishment of yeast mutant phenotypes, Molecular cell, 31 (2008) 925932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Nag R, Gong F, Fahy D, Smerdon MJ, A single amino acid change in histone H4 enhances UV survival and DNA repair in yeast, Nucleic acids research, 36 (2008) 38573866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Chaudhuri S, Wyrick JJ, Smerdon MJ, Histone H3 Lys79 methylation is required for efficient nucleotide excision repair in a silenced locus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Nucleic acids research, 37 (2009) 1690–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Suka N, Suka Y, Carmen AA, Wu J, Grunstein M, Highly specific antibodies determine histone acetylation site usage in yeast heterochromatin and euchromatin, Molecular cell, 8 (2001) 473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Auger A, Galarneau L, Altaf M, Nourani A, Doyon Y, Utley RT, Cronier D, Allard S, Cote J, Eaf1 is the platform for NuA4 molecular assembly that evolutionarily links chromatin acetylation to ATP-dependent exchange of histone H2A variants, Molecular and cellular biology, 28 (2008) 2257–2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Mitchell L, Lambert JP, Gerdes M, Al-Madhoun AS, Skerjanc IS, Figeys D, Baetz K, Functional dissection of the NuA4 histone acetyltransferase reveals its role as a genetic hub and that Eaf1 is essential for complex integrity, Molecular and cellular biology, 28 (2008) 2244–2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Searle NE, Torres-Machorro AL, Pillus L, Chromatin Regulation by the NuA4 Acetyltransferase Complex Is Mediated by Essential Interactions Between Enhancer of Polycomb (Epl1) and Esa1, Genetics, 205 (2017) 1125–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Torres-Machorro AL, Pillus L, Bypassing the requirement for an essential MYST acetyltransferase, Genetics, 197 (2014) 851–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Torres-Machorro AL, Clark LG, Chang CS, Pillus L, The Set3 Complex Antagonizes the MYST Acetyltransferase Esa1 in the DNA Damage Response, Molecular and cellular biology, 35 (2015) 3714–3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Brown CE, Howe L, Sousa K, Alley SC, Carrozza MJ, Tan S, Workman JL, Recruitment of HAT complexes by direct activator interactions with the ATM-related Tra1 subunit, Science, 292 (2001) 2333–2337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ginsburg DS, Govind CK, Hinnebusch AG, NuA4 lysine acetyltransferase Esa1 is targeted to coding regions and stimulates transcription elongation with Gcn5, Molecular and cellular biology, 29 (2009) 6473–6487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Downs JA, Allard S, Jobin-Robitaille O, Javaheri A, Auger A, Bouchard N, Kron SJ, Jackson SP, Cote J, Binding of chromatin-modifying activities to phosphorylated histone H2A at DNA damage sites, Molecular cell, 16 (2004) 979–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Pan X, Ye P, Yuan DS, Wang X, Bader JS, Boeke JD, A DNA integrity network in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Cell, 124 (2006) 1069–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Reid JL, Iyer VR, Brown PO, Struhl K, Coordinate regulation of yeast ribosomal protein genes is associated with targeted recruitment of Esa1 histone acetylase, Molecular cell, 6 (2000) 1297–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Robert F, Pokholok DK, Hannett NM, Rinaldi NJ, Chandy M, Rolfe A, Workman JL, Gifford DK, Young RA, Global position and recruitment of HATs and HDACs in the yeast genome, Molecular cell, 16 (2004) 199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ginsburg DS, Anlembom TE, Wang J, Patel SR, Li B, Hinnebusch AG, NuA4 links methylation of histone H3 lysines 4 and 36 to acetylation of histones H4 and H3, The Journal of biological chemistry, 289 (2014) 32656–32670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Pijnappel WW, Schaft D, Roguev A, Shevchenko A, Tekotte H, Wilm M, Rigaut G, Seraphin B, Aasland R, Stewart AF, The S cerevisiae SET3 complex includes two histone deacetylases, Hos2 and Hst1, and is a meiotic-specific repressor of the sporulation gene program, Genes & development, 15 (2001) 2991–3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kim T, Xu Z, Clauder-Munster S, Steinmetz LM, Buratowski S, Set3 HDAC mediates effects of overlapping noncoding transcription on gene induction kinetics, Cell, 150 (2012) 1158–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kim T, Buratowski S, Dimethylation of H3K4 by Set1 recruits the Set3 histone deacetylase complex to 5’ transcribed regions, Cell, 137 (2009) 259–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Vannier D, Balderes D, Shore D, Evidence that the transcriptional regulators SIN3 and RPD3, and a novel gene (SDS3) with similar functions, are involved in transcriptional silencing in S. cerevisiae, Genetics, 144 (1996) 1343–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Gorrini C, Squatrito M, Luise C, Syed N, Perna D, Wark L, Martinato F, Sardella D, Verrecchia A, Bennett S, Confalonieri S, Cesaroni M, Marchesi F, Gasco M, Scanziani E, Capra M, Mai S, Nuciforo P, Crook T, Lough J, Amati B, Tip60 is a haplo-insufficient tumour suppressor required for an oncogene-induced DNA damage response, Nature, 448 (2007) 1063–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Chen G, Cheng Y, Tang Y, Martinka M, Li G, Role of Tip60 in human melanoma cell migration, metastasis, and patient survival, J Invest Dermatol, 132 (2012) 2632–2641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wang Y, Dai DL, Martinka M, Li G, Prognostic significance of nuclear ING3 expression in human cutaneous melanoma, Clin Cancer Res, 13 (2007) 4111–4116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Gunduz M, Beder LB, Gunduz E, Nagatsuka H, Fukushima K, Pehlivan D, Cetin E, Yamanaka N, Nishizaki K, Shimizu K, Nagai N, Downregulation of ING3 mRNA expression predicts poor prognosis in head and neck cancer, Cancer Sci, 99 (2008) 531–538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Miyamoto N, Izumi H, Noguchi T, Nakajima Y, Ohmiya Y, Shiota M, Kidani A, Tawara A, Kohno K, Tip60 is regulated by circadian transcription factor clock and is involved in cisplatin resistance, The Journal of biological chemistry, 283 (2008) 18218–18226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.