Abstract

Vitis amurensis is a wild Vitis plant that can withstand extreme cold temperatures. However, the accumulation of metabolites during cold acclimation (CA) in V. amurensis remains largely unknown. In this study, plantlets of V. amurensis and V. vinifera cv. Muscat of Hamburg were treated at 4 °C for 24 and 72 h, and changes of metabolites in leaves were detected by gas chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Most of the identified metabolites, including carbohydrates, amino acids, and organic acids, accumulated in the two types of grape after CA. Galactinol, raffinose, fructose, mannose, glycine, and ascorbate were continuously induced by cold in V. amurensis, but not in Muscat of Hamburg. Twelve metabolites, including isoleucine, valine, proline, 2-oxoglutarate, and putrescine, increased in V. amurensis during CA. More galactinol, ascorbate, 2-oxoglutarate, and putrescine, accumulated in V. amurensis, but not in Muscat of Hamburg, during CA, which may be responsible for the excellent cold tolerance in V. amurensis. The expression levels of the genes encoding β-amylase (BAMY), galactinol synthase (GolS), and raffinose synthase (RafS) were evaluated by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR. The expression BAMY (VIT_02s0012 g00170) and RafS (VIT_05s0077 g00840) were primarily responsible for the accumulation of maltose and raffinose, respectively. The accumulation of galactinol was attributed to different members of GolS in the two grapes. In conclusion, these results show the inherent differences in metabolites between V. amurensis and V. vinifera under CA.

Subject terms: Secondary metabolism, Abiotic

Grapes: staying out in the cold

Studying how the wild grape Vitis amurensis copes with cold may help in breeding grape varieties that can grow at lower temperatures. To prevent frost damage, plants can increase cells’ sugar and protein contents, lowering the freezing point, and preventing ice crystal formation. V. amurensis, a wild grape native to Asia, grows well at low temperatures, but its cold-tolerance compounds have yet to be identified. Haiping Xin and Shaohua Li at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and co-workers profiled the compounds present in V. amurensis and V. vinifera cv. Muscat of Hamburg, a wine grape, following cold stress. V. amurensis cells were richer in a dozen compounds, including amino acids, organic acids, and putrescine, a component of the odor of decaying flesh. These results may help in developing grape varieties with increased cold tolerance.

Background

Low temperature stress is a major determinant of plant growth and development. This condition not only affects the geographical locations of crops but also causes significant losses in their productivity1. Investigations on the regulatory mechanisms underlying low temperature stress responses in plants are essential for crop breeding. Plants show increased freezing tolerance following exposure to low non-freezing temperatures, a phenomenon known as cold acclimation (CA)2,3. CA in plant cells leads to a series of physiological and biochemical changes, including increased scavenging of reactive oxygen species4, increased membrane stability5, and accumulated soluble sugars6,7 and proline6,8. These responses ultimately increase freezing tolerance9.

Mass spectrometry (MS)-based metabolomic techniques identify comprehensive metabolites during the cold condition in plants10,11. Metabolomics, together with transcriptomics and proteomics, provides a major tool for the characterization of postgenomic processes12. Metabolomics involves detecting and quantifying metabolic changes with techniques such as gas chromatography–MS (GC–MS)13,14, liquid chromatography–MS (LC–MS)15,16, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy17. GC–MS-based metabolite profiling offers a good balance of sensitivity and reliability and is considerably more sensitive than NMR spectroscopy and more robust than LC–MS18. GC–MS is particularly effective in the analysis of primary metabolites, specifically those involved in central carbon metabolism. The metabolic profiles have been analyzed in many plants exposed to low temperature stress. These plants include the model plant Arabidopsis19,20 and other species such as Oryza sativa21,22, Triticum aestivum23, Fragaria sp.24, Thellungiella salsuginea25, and Haberlea rhodopensis26. Low temperature stress leads to numerous changes in the metabolic profile of plants. Specific metabolites accumulate in cold-acclimated plants that correlate with the cold tolerance of plants27–29. For example, this stress increases the levels of carbohydrates, such as sucrose, galactinol, and raffinose30. The levels of amino acids, such as proline, organic acids, and tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediates also increase. The metabolites in cold-tolerant accessions, cultivars, or species differ from those in cold-sensitive ones under low temperature stress, and these metabolites possibly contribute to cold tolerance20. In general, stress-tolerant plants express more metabolites, such as proline and soluble sugars, than stress-sensitive plants31. However, stress-sensitive plants accumulate few stress-associated metabolites, which are not sufficient to resist against cold damages. For example, analysis of the metabolic profile of Arabidopsis accessions with different levels of freezing tolerance revealed that compatible solutes, including proline and raffinose, contribute to freezing tolerance20. Similarly, metabolic profiling of the cold-tolerant species H. rhodopensis and of Thellungiella and Arabidopsis indicated that H. rhodopensis is pre-adapted to cold by constitutive accumulation of high levels of protective metabolites, such as galactinol and raffinose26.

Grape is an important fruit economically worldwide32. Grape is primarily grown in temperate and subtropical regions, which have low temperatures that negatively affect the production and quality of grapes. Rapid temperature drop in late fall, freezing temperatures in mid-winter, and early spring frost seriously damage grapevines and cause fruit production losses33,34. Investigations on cold stress responses and regulatory pathways are important for breeding new grape cultivars with preeminent cold tolerance.

Vitis amurensis is an important wild grape germplasm resource that originated from eastern Asia. This Vitis species shows strong tolerance to extremely low temperatures, even less than −40 °C34,35, and has been widely used as a parent in grape breeding for selecting cold-tolerant cultivars36. To elucidate the mechanism underlying low temperature adaptation, transcriptome modifications under cold treatment in V. amurensis have been analyzed, and a subgroup of cold stress-related genes has been identified33,36. In V. amurensis, the functions of several cold-induced genes, such as CBF37, ICE38, ERF39, and GRAS40, have also been reported. Although these findings increase our knowledge of cold stress response in V. amurensis, the metabolite changes in grape plants under CA remain unclear. Discovering the CA-induced metabolome modifications under CA in grapes, particularly in V. amurensis, may not only help to understand the mechanisms underlying low temperature adaptation in grapes but also provide the essential data to explain the excellent cold tolerance in V. amurensis.

In the present study, plantlets of V. amurensis and Vitis vinifera cv. Muscat of Hamburg (with less cold tolerance when compared with V. amurensis) were treated at 4 °C for 24 and 72 h. GC coupled with time-of-flight MS (GC–TOF–MS) was used to identify the metabolite changes in the leaves of the two grape species. The expression levels of genes encoding for β-amylase (BAMY), galactinol synthase (GolS), and raffinose synthase (RafS) were evaluated by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses. The relationships between the gene expression and the accumulation of the metabolites were analyzed. The possible contribution of CA-related metabolites during cold tolerance in V. amurensis was also discussed.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Micropropagated seedlings of V. amurensis (collected from Changbai Mountain in Jilin Province, China) and V. vinifera cv. Muscat of Hamburg were cultivated in a chamber at the Wuhan Botanical Garden of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The seedlings were grown on 1/2 B5 medium with 30 g L−1 sucrose at 26 °C with a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod. Low temperature treatments were performed by placing 40-day-old plantlets in another growth chamber with the same parameters except for temperature, which was set at 4 °C. The leaves were collected after 0 (used as the control), 24, and 72 h and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Then, the samples were ground into fine powder and stored at −80 °C. Six and three replicate samples were collected at specific time points for each species for metabolome and qRT-PCR analyses, respectively.

Measurement of metabolites

Leaf extracts were prepared as previously described by Weckwerth et al.41. Ground samples (100 mg) were transferred into 2 mL centrifuge tubes. A total of 1.5 mL of buffer containing methanol/chloroform/water (5:2:2, v/v/v) and ribitol (5 mg mL−1, an internal standard) was added into the tubes. The samples were then incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, the tubes were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was decanted into a 2 mL screw-top glass tube. Then, the tubes were placed into a vacuum concentrator at 30 °C for 2 h to dry the extracts. The extracts were dissolved in 50 μL of methoxamine hydrochloride and then incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Then, the samples were derivatized with 80 μL of N-methyl-N-trimethylsilyl trifluoroacetamide for 30 min at 37 °C.

The well-prepared samples were analyzed with a gas chromatograph (6890N; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled with a Pegasus IV time-of-flight mass spectrometer (LECO Instruments, St. Joseph, MI) that used a VF-5 capillary column (Varian, USA). Helium was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 mL min−1. The column temperature was maintained at 60 °C for 1 min, increased to 310 °C at a rate of 8 °C min−1, and then held for 15 min. Injection and ion source temperatures were 250 °C and 200 °C, respectively. Energy was set at −70 eV in an electron impact mode. MS data were acquired in a full scan mode with an m/z range of 50–600 after a solvent delay of 6 min.

Peak identification and quantification were performed using Chroma TOF (version 4.34) of the LECO Corporation. In brief, the data processing method included ‘Baseline,’ ‘Peak Find,’ and ‘Calculate Area/Height’41–43. For these processes, the peak width was set at 6 s. A maximum of detected peaks over a signal/noise threshold of 20 was used. Compound identification was based on searching the mass spectra in the standard NIST08 library41. Unique fragment ions for each individual metabolite were used for area calculation and manually corrected when necessary44. The mass retention time paired with the highest relative abundance was chosen to represent each metabolite. The amount of metabolites was normalized to plant mg fresh weight (FW) and then by area of internal references.

Annotation of members of the BAMY, GolS, and RafS gene families in grapes

Members of the BAMY gene family in grape were identified using Hidden Markov Model (HMM), BLASTP program and NCBI-Conserved Domain Data (CDD) search. In brief, the HMM (HMMER, http://www.hmmer.org) from Pfam was downloaded to identify related homologous genes45. Then, we searched its homologous genes in the V. vinifera genome (http://plants.ensembl.org/index.html) with the model using HMM. The threshold value was set to 1e−15. Seven members of the BAMY gene family in grape were identified by the NCBI-CDD (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) search (Supplementary Figure S1)46. Members of GolS and RafS gene families were identified based on Sun et al. (Supplementary Table S4).47

qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA of grape leaves was extracted using an RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (DP432; Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China). RNA quality and concentration were detected through agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000; Thermo Scientific, USA). The complementary DNA was synthesized using HiScript® II Reverse Transcriptase (Vazyme Biotech Co., Nanjing, China) and then subjected to qRT-PCR on an Opticon thermocycler (CFX Connect Real-Time System; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using SYBR Green PCR master mix (Vazyme Biotech Co, Nanjing, China) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. VviActin (accession: EC969944) was used as the reference gene, and specific primer pairs for relevant genes were designed using Primer-BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/, Supplementary Table S5). The specificity of designed primers was verified through gel electrophoresis. The PCR reactions were set under the following conditions: 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Each sample was analyzed with three biological and technical replicates. The relative expression levels of the target genes were examined using the 2−ΔΔCt method. Significant difference was determined by t-test (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, n = 3) using the R program.

Statistical analyses

Detected samples of metabolites were replicated six times; means and calculated standard errors (S.E.) are reported (Supplementary Table S1). The ratio of the average normalized peak areas for the metabolite between CA and pre-stress > 1 with P < 0.05 increased in response to cold stress, and whereas that between CA and pre-stress < 1 with P < 0.05 decreased. P-values of metabolite data were calculated using a two-tailed Student’s t-test comparing inter- and intra-genotype differences to cold stress at 0, 24, and 72 h. T-test was performed using R (version 3.1.1), and principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted using SIMCA-P (version 13.0; Umetrics, Umea, Sweden).

Results

PCA of metabolites under cold treatment

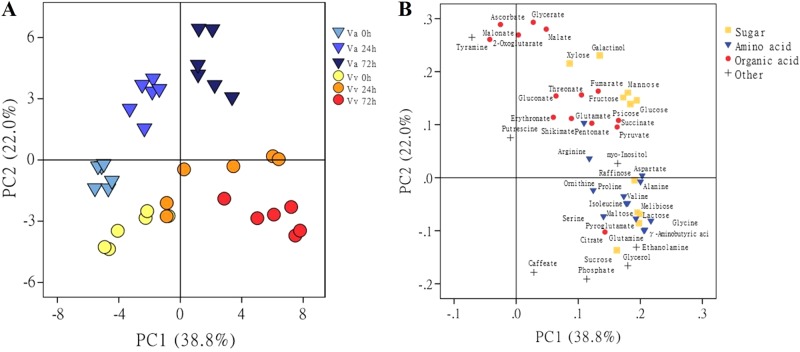

No morphological difference was observed between V. amurensis and V. vinifera cv. Muscat of Hamburg under cold treatment (Supplementary Figure S2); nevertheless, the levels of metabolites changed in the two varieties after the cold acclamation. GC–TOF–MS was used to investigate the metabolic shifts resulting from cold stress in the two grape species. A total of 11 sugars, 13 amino acids, 14 organic acids, and 7 other compounds were detected. PCA was performed to test the metabolic changes in the two types of grapes under the cold condition (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Principal component analysis of metabolite profiles in leaves of V. amurensis and V. vinifera cv. Muscat of Hamburg.

Va V. amurensis; Vv V. vinifera cv. Muscat of Hamburg. Score plot (a) of samples and loading plot (b) of metabolites for the first two components, 1 (PC1) and 2 (PC2). Samples at 0, 24, and 72 h after cold treatment are represented by different shapes with colors. Each point represents an individual biological replicate in a (n = 6) and a single metabolite in b

The PCA score plot indicated that the first principal component (PC1) and the second principal component (PC2) represented 38.8% and 22.0% of the total variance, respectively (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table S2). The two varieties did not separate under the normal condition without stress in the PCA score plot. After 24 h of cold stress, both types of grapes clustered to the right of the pre-stress samples along PC1. However, their values differed along PC2, i.e., positive for V. amurensis and negative for Muscat of Hamburg. After 72 h of CA, the distinction between V. amurensis and Muscat of Hamburg remained consistent over the cold stress, moving farther along PC1 with additional cold stress and maintaining their clear separation in PC2.

The loading plot was performed to show the contribution of individual metabolites to the total variance (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table S3). The metabolites with huge values along the first two components were considered as important variance of the loading plot. Sugars were identified as important in both dimensions (e.g., galactinol and fructose). Compounds that contributed to distinction primarily along PC1 were amino acids (e.g., aspartate and proline). Separation on PC2 could be attributed to organic acids (e.g., ascorbate and 2-oxoglutarate). Detailed comparisons of each metabolite inter- and intra-species were performed.

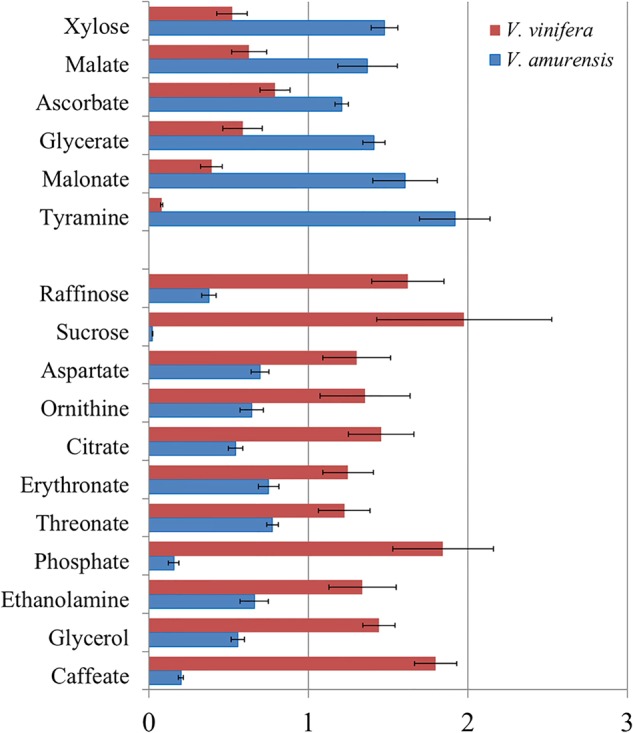

Comparison of metabolite levels between V. amurensis and V. vinifera under the pre-stress condition

The relative contents of metabolites with significant differences (P < 0.05) between the two types of grapes under the normal condition are shown in Fig. 2. Compared with V. vinifera, V. amurensis had higher concentrations of six metabolites, namely, one carbohydrate (xylose), four organic acids (malate, ascorbate, glycerate, and malonate), and tyramine. By contrast, compared with V. amurensis, V. vinifera accumulated higher contents of 11 metabolites, namely, two carbohydrates (raffinose and sucrose), two amino acids (asparate and ornithine), three organic acids (citrate, erythronate, and threonate), and four other compounds (phosphate, ethanolamine, glycerol, and caffeate). Maltose was not detected under pre-stress conditions in either type of grape. No significant differences were found in the other identified metabolites between the two species (Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 2. Metabolites with significantly different levels (P-value < 0.05, Student’s t-test) in V. amurensis (blue) and V. vinifera cv.

Muscat of Hamburg (red) under the non-cold stress condition. Metabolite levels are normalized by the means of all samples and presented as the mean ± SEM. of six biological replicates

Common responding metabolites in V. amurensis and V. vinifera under cold treatment

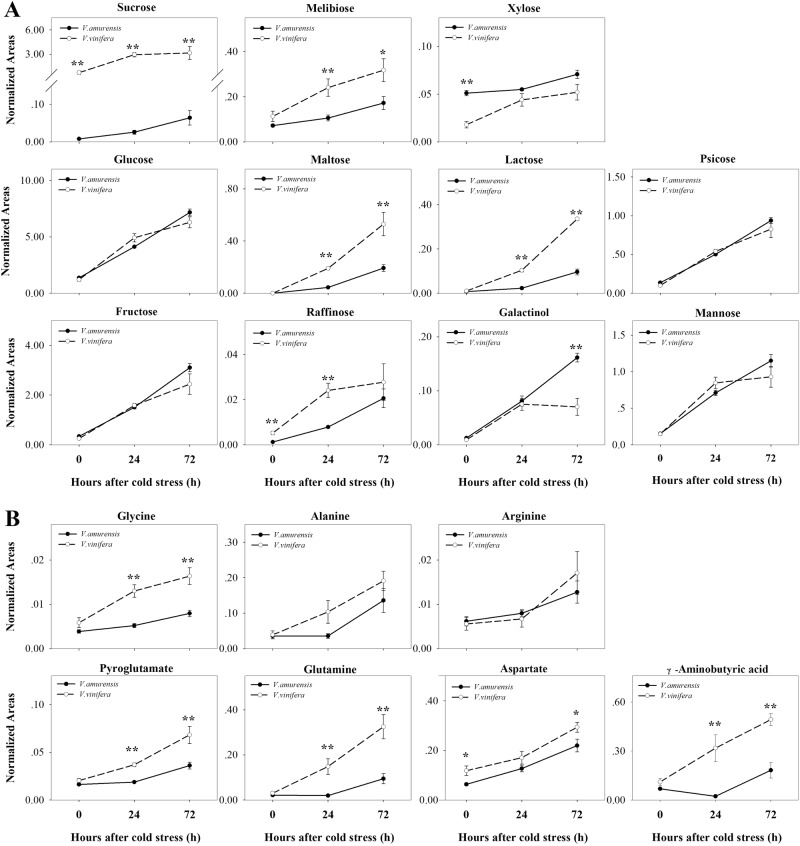

Eleven sugars increased significantly in both species after cold stress compared with levels in the normal condition (Fig. 3a). Sucrose and melibiose were sustained at higher levels under CA than those in pre-stress samples in V. amurensis and Muscat of Hamburg. The levels of glucose, maltose, lactose, and psicose increased with time in the two species of grapes. Furthermore, fructose, raffinose, galactinol, and mannose continuously accumulated with time in V. amurensis but were sustained in Muscat of Hamburg. In particular, the galactinol level increased in V. amurensis more than that in Muscat of Hamburg after exposure to cold stress.

Fig. 3. Common responding metabolites in V. amurensis and V. vinifera cv.

Muscat Hamburg under the cold stress condition. a Sugars; b amino acids; c organic acids; d others. The time points are the non-stress condition (0) and cold stress at 24 h (24) and 72 h (72). The time points are connected using solid (V. amurensis) or dotted (V. vinifera) lines. Each data point represents the average of six biological replicates with error bars representing the standard deviation. Asterisks (**) and (*) indicate significant differences between the two species at P-value < 0.01 and P-value < 0.05 (Student’s t-test), respectively.

Seven amino acids changed significantly after cold stress in both grapes (Fig. 3b). Six of these amino acids, namely, glycine, alanine, arginine, pyroglutamate, glutamine, and aspartate, showed identical variations, that is, they accumulated with time. Pyroglutamate and glutamine were significantly upregulated in Muscat of Hamburg at 24 h of cold stress, and these amino acids increased until 72 h of CA in V. amurensis. Aspartate increased with time in V. amurensis and was upregulated remarkably until 72 h of CA in Muscat of Hamburg. However, the levels of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) showed opposite trends in the two types of grape at 24 h of CA; GABA decreased in V. amurensis but increased in Muscat of Hamburg.

Seven organic acids showed increasing trends in both types of grapes under cold treatment (Fig. 3c). Glycerate level increased at 24 h under CA and sustained a high level in V. amurensis. Additionally, this level increased at 24 h but subsequently decreased to the no-stress level at 72 h in Muscat of Hamburg. Ascorbate accumulated with time in V. amurensis but was downregulated after 24 h in Muscat of Hamburg. Citrate showed a sudden accumulation at 24 h of cold stress in V. amurensis but sustained a high level in Muscat of Hamburg. Succinate and malate were sustained at a higher level under CA than that in pre-stress samples in both species. Pyruvate and fumarate accumulated with time in V. amurensis, whereas these acids accumulated until 72 h of CA in Muscat of Hamburg.

Additionally, phosphate, glycerol, and caffeate, which were categorized as other compounds, responded to cold in both types of grape (Fig. 3d). Caffeate increased in V. amurensis but decreased in Muscat of Hamburg under cold stress. Phosphate remarkably increased in both species at 24 h of cold stress. Glycerol was significantly upregulated in cold stress samples of Muscat of Hamburg and accumulated notably until 72 h of CA in V. amurensis.

Metabolites specifically accumulated in V. amurensis or V. vinifera under cold stress

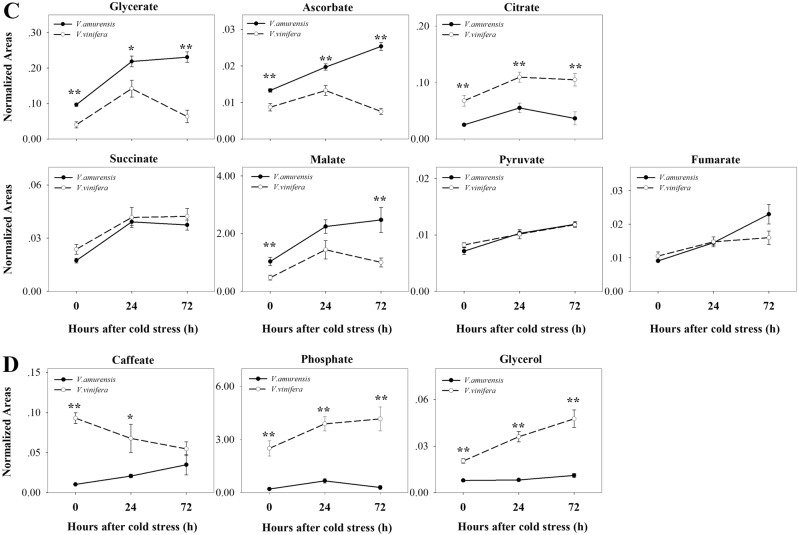

Twelve metabolites were upregulated remarkably and specifically in V. amurensis under CA (Fig. 4a). These metabolites included five amino acids (isoleucine, valine, proline, ornithine, and glutamine), six organic acids (2-oxoglutarate, gluconate, erythronate, threonate, shikimate, and pentonate), and putrescine. Isoleucine began to increase at 24 h, whereas the other amino acids accumulated significantly at 72 h of CA. Proline increased by eightfold at 72 h of CA with the largest fold change of the amino acids. Organic acids increased significantly in V. amurensis from 24 h of cold treatment except for pentonate, which increased at 72 h of CA. Putrescine was induced up to eightfold at 24 h of CA but then decreased to threefold at 72 h in V. amurensis. The levels of putrescine and 2-oxoglutarate were higher in V. amurensis than those in Muscat of Hamburg under cold stress. No significant difference was found in levels of putrescine and 2-oxoglutarate between the two species under the no-stress condition.

Fig. 4. Metabolites that specifically accumulated in V. amurensis and V. vinifera cv. Muscat Hamburg under the cold stress condition.

a the metabolites that specifically accumulated in V. amurensis; b the metabolites that specifically accumulated in V. vinifera cv. Muscat Hamburg. Time points are the non-stress condition (0) and cold stress at 24 h (24) and 72 h (72). Time points are connected using solid (V. amurensis) or dotted (V. vinifera) lines. Each data point represents the average of six biological replicates with error bars representing the standard deviation. Asterisks (**) and (*) indicate significant differences between the two species at P-value < 0.01 and P-value < 0.05 (Student’s t-test), respectively

Four metabolites increased significantly only in Muscat of Hamburg during CA (Fig. 4b). A carbohydrate derivative (myo-Inositol) increased with time under CA. Malonate was induced by cold at 24 h and then decreased at 72 h after CA. Malonate content was higher in V. amurensis than that in V. vinifera under pre-stress and cold treatment conditions. Ethanolamine was higher in V. vinifera than in V. amurensis under non-cold conditions, and tyramine was lower, with both induced at 72 h of CA in V. vinifera.

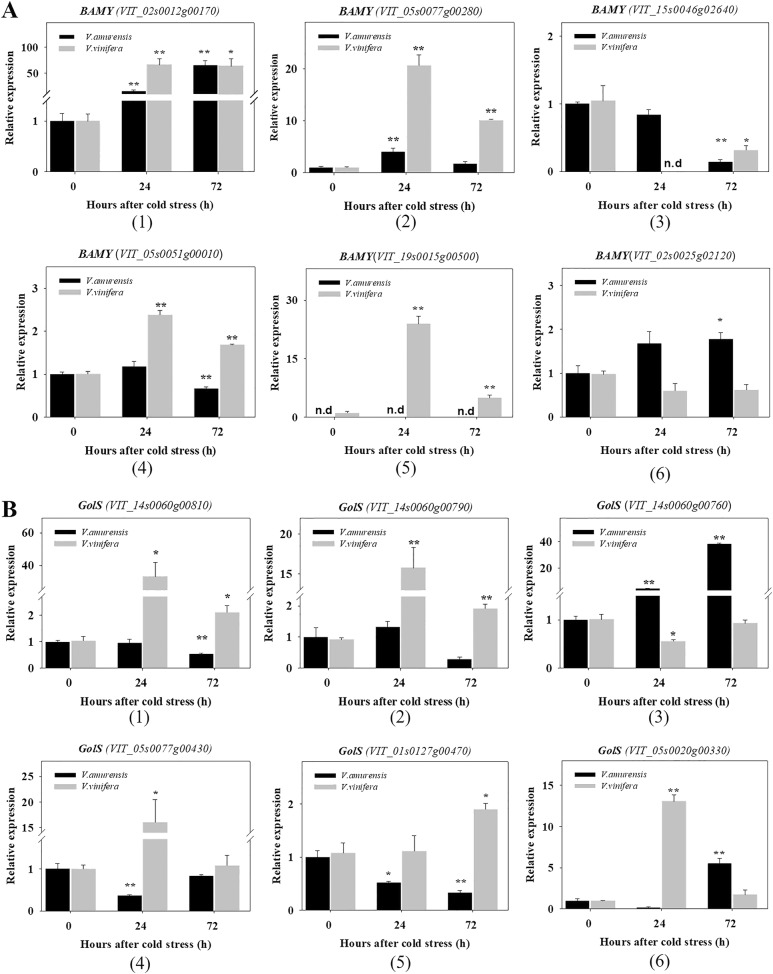

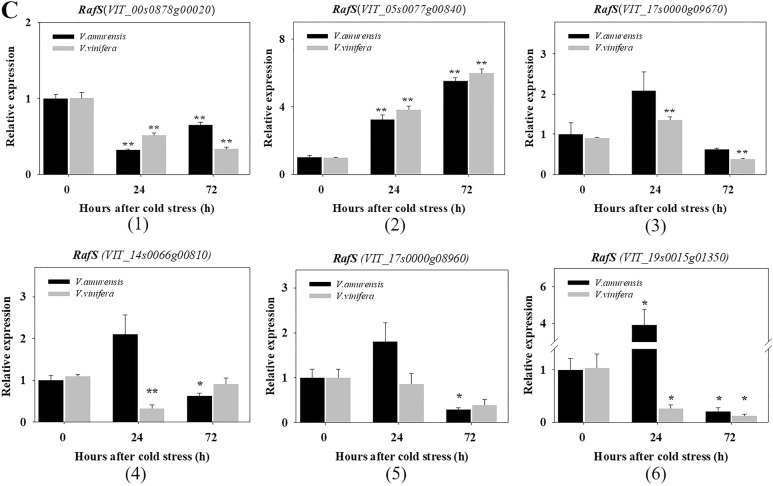

Expression of genes encoding for BAMY, GolS, and RafS

Raffinose and galactinol significantly increased in the two species of grapes under cold stress. Raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) are associated with chilling-stress tolerance in Arabidopsis and serve as plant cell protectants from oxidative damage48,49. GolS and RafS are key enzymes in the synthesis of galactinol and raffinose, respectively. Similarly, maltose accumulates in Arabidopsis under cold, and BAMY is the key enzyme in the synthesis of maltose50. Maltose was not detected in V. amurensis and Muscat of Hamburg under the normal condition but accumulated clearly after cold stress. Genes encoding for BAMY, GolS, and RafS were chosen to discover the relationships between metabolite accumulation and gene expression. The expression patterns of each gene family were analyzed by qRT-PCR, which were based on the same time points as those of the metabolic analysis (Fig. 5). The genes that were very low or undetectable in samples are not shown.

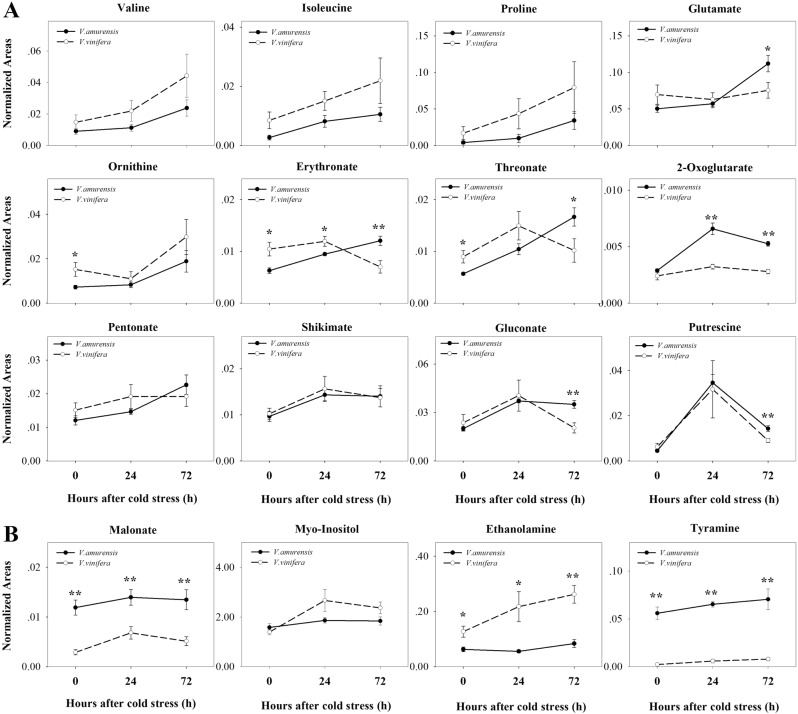

Fig. 5. qRT-PCR results for the BAMY, GolS, and RafS gene family members in V. amurensisand V. vinifera cv. Muscat Hamburg.

a BAMY; b GolS; c RafS. The time points are the non-stress condition (0) and cold stress at 24 h (24) and 72 h (72). Gene expression was normalized to the expression obtained in V. amurensis under the non-stress condition. The mean expression value was calculated from three technical replicates with three independent biological replicates (n = 3). Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. Asterisks (**) and (*) indicate significant differences compared with the WT at P-value < 0.01 and P-value < 0.05 (Student’s t-test), respectively

More members of BAMY were induced by cold in V. vinifera than in V. amurensis (Fig. 5a). VIT_02s0012g00170 displayed an upregulated and sustained high expression under cold stress (1). VIT_05s0077g00280 showed a sudden increase at 24 h in V. amurensis, whereas it was induced at both time points of cold stress in Muscat of Hamburg (2). The expression of VIT_05s0051g00010 and VIT_19s0015g00500 was significantly elevated in Muscat of Hamburg by cold (4 and 5). VIT_15s0046g02640 expression exhibited no change at 24 h and then prominently decreased at 72 h in both species (3). VIT_02s0025g02120 induced uniquely at 72 h in V. amurensis by cold stress (6).

The expression patterns of GolS are exhibited in Fig. 5b. The genes VIT_14s0060g00810, VIT_14s0060g00790, VIT_05s0077g00430, and VIT_05s0020g00330 showed the same expression patterns in Muscat of Hamburg, with expression levels increased significantly at 24 h and subsequently decreased at 72 h (1, 2, 4, 6). VIT_14s0060g00760 was significantly and sustainably increased in V. amurensis under the cold condition (3). The transcription level of VIT_01s0127g00470 increased at 72 h in Muscat of Hamburg, whereas the level decreased in V. amurensis (5).

Members subjected to qRT-PCR in the RafS gene family are shown in Fig. 5c. VIT_00s0878g00020, VIT_14s0066g00810, and VIT_17s0000g08960 were not significantly different or were downregulated in V. amurensis and Muscat of Hamburg in response to cold (1, 4, 5). The levels of VIT_05s0077g00840 increased significantly and were sustained by cold in both species (2). VIT_17s0000g09670 displayed a sudden increase at 24 h and then decreased in both grapes (3). VIT_19s0015g01350 remarkably increased at 24 h in V. amurensis and subsequently decreased at 72 h of cold treatment, whereas it decreased in Muscat of Hamburg during cold treatment (6).

Discussion

In this study, we used GC–TOF–MS to compare the metabolic profiles of V. amurensis and Muscat of Hamburg under control and cold stress conditions. This analysis highlighted the specific cold-responding metabolites in V. amurensis. The results of the analysis were used to investigate the mechanisms underlying low temperature adaptation in grapes.

The compounds accumulated in both grapes species during CA represented fundamental metabolites responding to cold stress. These metabolites, which included sugars (e.g., sucrose and glucose), amino acids (e.g., glycine and aspartate), and organic acids (succinate and malate), contributed to cold stress response/tolerance. Some of these metabolites are known to accumulate in other plants13,29. Cold exposure of Arabidopsis increases the levels of amino acids (glycine and arginine), the carbohydrates glucose and maltose, TCA cycle intermediates, and succinate29. Glucose rapidly accumulates in both cold-tolerant and -intolerant accessions of Arabidopsis and remains high during 7 days of CA51. Metabolites glycine, aspartate, glucose, and sucrose also accumulate in rice after CA21. Changes in these metabolites suggest conserved reconstruction in metabolome levels in plants to increase cold tolerance.

Different patterns of accumulation were also found in a subset of common responding metabolites between the two species. For example, galactinol, raffinose, fructose, mannose, glycine, and ascorbate were induced by cold stress in V. amurensis but remained constant after 24 h of cold exposure in Muscat of Hamburg. In wheat leaves, mannose modulates the expression of the enzymatic antioxidant defense system52, and d-mannose treatment influences the expression level of different antioxidant enzymes, such as ascorbate peroxidase (APX), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT) in wheat coleoptiles53. Glycine is directly related to the metabolism of amino acids, and upregulation of glycine levels could result from the recycling of amino acids54. In particular, amounts of galactinol and ascorbate were higher in V. amurensis than those in Muscat of Hamburg. Raffinose and galactinol are precursors of RFOs that most likely act as ROS scavengers and osmoprotectants to stabilize cellular membranes against abiotic stresses, including chilling48. Raffinose is induced at low temperatures in dicots51 and monocots55. High levels of galactinol during CA correlate with low temperature tolerance in diploid strawberry24. Ascorbate as an abundant antioxidant can protect against reactive oxygen species, which are produced when plants are exposed to low temperature stress56. Metabolites that were sustainably upregulated and in high amounts in V. amurensis may protect plants from long-term low temperature damage and increase cold tolerance.

A subset of metabolites specifically accumulated in V. amurensis (Fig. 4a). Of these specific compounds, the level of putrescine increases in several plants responding to multiple abiotic stresses, such as salt57, drought58, and low temperature59. Exogenous application of putrescine decreases membrane leakage that is caused by low temperature in tomato60. Mutants of Arabidopsis (ADC2) that are deficient in endogenous putrescine are sensitive to abiotic stresses61. In our research, high levels and specific accumulation of putrescine might relate to the cold tolerance of V. amurensis. For several amino acids, including valine, isoleucine, and proline, the accumulation was greater in V. amurensis than that in Muscat of Hamburg during cold stress. Free amino acids are hypothesized to play a role as osmolytes during abiotic stress responses in plants62. In particular, the accumulation of branched-chain amino acids, such as valine and isoleucine, reportedly show a high fold increase under abiotic stress63. Proline, as an osmoprotectant, accumulates during CA26,46. In previous research examining exogenous proline treatment, a positive correlation was revealed between proline accumulation and cold stress tolerance64. The level of proline is higher in the wheat crown than that in shoots, which is an indication of an essential role in the frost tolerance of the crown23. The specific accumulation of these metabolites in cold-acclimated V. amurensis provided evidence for their important roles in defense against cold stress. In particular, the levels of 2-oxoglutarate and putrescine were higher in V. amurensis than those in Muscat of Hamburg. This result indicated that these metabolites act as indicator compounds of the cold tolerance of grape. Moreover, the accumulation of different metabolites demonstrated that different response mechanisms are required in various stages of cold stress in V. amurensis.

Expression analysis of the genes associated with the accumulated metabolites was performed. A relationship between high transcript levels of the gene counterparts and increased levels of metabolites has been reported in cold-treated Arabidopsis65 and rice21. In the present study, VIT_02s0012g00170 of the BAMY gene family displayed an upregulated and sustained high expression under cold stress (Fig. 5a1). The upregulated expression pattern of this gene was consistent with the accumulation of maltose under cold stress. Therefore, this gene was likely the predominant gene for maltose accumulation in grapes under the cold condition. Moreover, the higher content of maltose in Muscat of Hamburg than that in V. amurensis suggested that more members of BAMY were induced by cold in Muscat of Hamburg. We observed that different members of GolS were upregulated in the two species under cold. VIT_14s0060g00760 showed a significant and sustained increase in V. amurensis (Fig. 5b3), which was consistent with the high accumulation of galactinol in V. amurensis, reflecting its potential role in galactinol biosynthesis in V. amurensis under the cold condition. By contrast, in Muscat of Hamburg, the accumulation of galactinol might be the result of the upregulated expression of several GolS genes during cold. For RafS, the expression of VIT_05s0077g00840 was significantly promoted during cold stress, and this trend was consistent with the biosynthesis of raffinose in grape (Fig. 5c1). Therefore, this gene might be the primary contributor to the accumulation of raffinose in grape under cold stress. VIT_19s0015g01350 was significantly upregulated in cold-treated V. amurensis (Fig. 5c6) and therefore was also a contributing gene to the accumulation of raffinose in V. amurensis under CA. These results provide new insights into the relationship between transcript level and metabolite accumulation and into the mechanisms underlying metabolite accumulation under cold exposure.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The Youth Innovation Promotion Association of CAS (2015281), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC Accession No. 31471857 and 31672132), Science and Technology Service Network Initiative of CAS (KFJ-STS-ZDTP-025) and Grape Breeding Project of Ningxia (NXNYYZ201502) supported this work.

Authors' contributions

S.L. and H.X. designed and provided guidance for this research. W.L., Y.X., and X.M. helped perform the experiments and analyze data. G.L. and L.D. helped analyze data, and C.C. and X.S. helped perform the qRT-PCR. C.F., H.X., and L.S. wrote and improved the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Haiping Xin, Email: xinhaiping215@hotmail.com.

Shaohua Li, Email: shhli@ibcas.ac.cn.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at (10.1038/s41438-018-0083-5).

References

- 1.Thomashow MF. Plant cold acclimation: freezing tolerance genes and regulatory mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 1999;50:571–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smallwood M, Bowles DJ. Plants in a cold climate. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2002;357:831–847. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomashow MF. Role of cold-responsive genes in plant freezing tolerance. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:1–7. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant. Sci. 2002;7:405–410. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hare PD, Cress WA, Staden JV. Dissecting the roles of osmolyte accumulation during stress. Plant Cell Environ. 1998;21:535–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1998.00309.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xin ZG, Browse J. eskimo1 mutants of Arabidopsis are constitutively freezing-tolerant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:7799–eskimo7804. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wanner LA, Junttila O. Cold-induced freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 1999;120:391–399. doi: 10.1104/pp.120.2.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorffling K, et al. Heritable improvement of frost tolerance in winter wheat by in vitro-selection of hydroxyproline-resistant proline overproducingmutants. Euphytica. 1997;93:1–10. doi: 10.1023/A:1002946622376. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janska A, Marsik P, Zelenkova S, Ovesna J. Cold stress and acclimation - what is important for metabolic adjustment? Plant Biol. 2010;12:395–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shulaev V, Cortes D, Miller G, Mittler R. Metabolomics for plant stress response. Physiol. Plant. 2008;132:199–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2007.01025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weckwerth W, Fiehn O. Can we discover novel pathways using metabolomic analysis? Curr. Opin. Biotech. 2002;13:156–160. doi: 10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgenthal K, Weckwerth W, Steuer R. Metabolomic networks in plants: transitions from pattern recognition to biological interpretation. Bio. Syst. 2006;83:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barding GA, Beni S, Fukao T, Bailey-Serres J, Larive CK. Comparison of GC-MS and NMR for metabolite profiling of rice subjected to submergence stress. J. Proteome Res. 2013;12:898–909. doi: 10.1021/pr300953k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wen YQ, et al. Using the combined analysis of transcripts and metabolites to propose key genes for differential terpene accumulation across two regions. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:240. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0631-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn WB, et al. Procedures for large-scale metabolic profiling of serum and plasma using gas chromatography and liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 2011;6:1060–1083. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takahashi H, Morimoto T, Ogasawara N, Kanaya S. AMDORAP: non-targeted metabolic profiling based on high-resolution LC-MS. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:259. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barding GA, Jr., Fukao T, Beni S, Bailey-Serres J, Larive CK. Differential metabolic regulation governed by the rice SUB1A gene during submergence stress and identification of alanylglycine by 1H NMR spectroscopy. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11:320–330. doi: 10.1021/pr200919b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lisec J, Schauer N, Kopka J, Willmitzer L, Fernie AR. Gas chromatography mass spectrometry-based metabolite profiling in plants. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:387–396. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook D, Fowler S, Fiehn O, Thomashow MF. A prominent role for the CBF cold response pathway in configuring the low-temperature metabolome of Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15243–15248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406069101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannah MA, et al. Natural genetic variation of freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;142:98–112. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.081141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maruyama K, et al. Integrated analysis of the effects of cold and dehydration on rice metabolites, phytohormones, and gene transcripts. Plant Physiol. 2014;164:1759–1771. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.231720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morsy MR, Jouve L, Hausman JF, Hoffmann L, Stewart JM. Alteration of oxidative and carbohydrate metabolism under abiotic stress in two rice (Oryza sativa L.) genotypes contrasting in chilling tolerance. J. Plant. Physiol. 2007;164:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juhász Z, et al. Pleiotropic effect of chromosome 5A and the mvp mutation on the metabolite profile during cold acclimation and the vegetative/generative transition in wheat. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:57. doi: 10.1186/s12870-014-0363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davik J, et al. Dehydrin, alcohol dehydrogenase, and central metabolite levels are associated with cold tolerance in diploid strawberry (Fragaria spp.) Planta. 2013;237:265–277. doi: 10.1007/s00425-012-1771-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee YP, et al. Comparison of freezing tolerance, compatible solutes and polyamines in geographically diverse collections of Thellungiella sp. and Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benina M, et al. Comparative metabolic profiling of Haberlea rhodopensis, Thellungiella halophyla, and Arabidopsis thaliana exposed to low temperature. Front. Plant Sci. 2013;4:499. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2013.00499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zuther E, Schulz E, Childs LH, Hincha DK. Clinal variation in the non-acclimated and cold-acclimated freezing tolerance of Arabidopsis thaliana accessions. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35:1860–1878. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray GR, Heath D. A global reorganization of the metabolome in Arabidopsis during cold acclimation is revealed by metabolic fingerprinting. Physiol. Plant. 2005;124:236–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2005.00507.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan F, et al. Exploring the temperature-stress metabolome of Arabidopsis1[W] Plant Physiol. 2004;136:4159–4168. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.052142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohde P, Hincha DK, Heyer AG. Heterosis in the freezing tolerance of crosses between two Arabidopsis thaliana accessions (Columbia-0 and C24) that show differences in non-acclimated and acclimated freezing tolerance. Plant J. 2004;38:790–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krasensky J, Jonak C. Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:1593–1608. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vivier MA, Pretorius IS. Genetically tailored grapevines for the wine industry. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:472–478. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)02058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xin H, et al. Genome wide transcriptional profile analysis of Vitis amurensis and Vitis vinifera in response to cold stress. PLoS. One. 2013;8:e58740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fennell A. Freezing tolerance and injury in grapevines. J. Crop Improv. 2004;10:201–235. doi: 10.1300/J411v10n01_09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan Y, et al. The eco-geographic distribution of wild grape germplasm in China. VITIS. 2008;47:77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu W, et al. Transcriptome profiling of Vitis amurensis, an extremely cold-tolerant Chinese wild Vitis species, reveals candidate genes and events that potentially connected to cold stress. Plant Mol. Biol. 2014;86:527–541. doi: 10.1007/s11103-014-0245-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Wang N, Xin H, Li S. Overexpression of VaCBF4, a transcription factor from Vitis amurensis, improves cold tolerance accompanying increased resistance to drought and salinity in Arabidopsis. Plant. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2013;31:1518–1528. doi: 10.1007/s11105-013-0627-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, et al. Characterization of two VvICE1 genes isolated from ‘Muscat Hamburg’ grapevine and their effect on the tolerance to abiotic stresses. Sci. Hortic.-Amst. 2014;165:266–273. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun X, et al. Ethylene positively regulates cold tolerance in grapevine by modulating the expression of ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR 057. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:24066. doi: 10.1038/srep24066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yuan Y, et al. Overexpression of VaPAT1, a GRAS transcription factor from Vitis amurensis, confers abiotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2016;35:655–666. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1910-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weckwerth W, Wenzel K, Fiehn O. Process for the integrated extraction, identification and quantification of metabolites, proteins and RNA to reveal their co-regulation in biochemical networks. Proteomics. 2004;4:78–83. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200200500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernie AR, et al. Recommendations for reporting metabolite data. Plant Cell. 2011;23:2477–2482. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.086272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guo R, et al. Comparative metabolic responses and adaptive strategies of wheat (Triticum aestivum) to salt and alkali stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:170. doi: 10.1186/s12870-015-0546-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wagner C, Sefkow M, Kopka J. Construction and application of a mass spectral and retention time index database generated from plant GC/EI-TOF-MS metabolite profiles. Phytochemistry. 2003;62:887–900. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(02)00703-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finn RD, et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:279–285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marchler-Bauer A, et al. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;45:D200–D203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun X, et al. The GARP/MYB-realated grape transcription factor AQUILO improves cold tolerance and promotes the accumulation of raffionose family oligosaccharides. J. Exp. Bot. 2018;69:1749–1764. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nishizawa A, Yabuta Y, Shigeoka S. Galactinol and raffinose constitute a novel function to protect plants from oxidative damage. Plant Physiol. 2008;147:1251–1263. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.122465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.ElSayed AI, Rafudeen MS, Golldack D. Physiological aspects of raffinose family oligosaccharides in plants: protection against abiotic stress. Plant Biol. 2014;16:1–8. doi: 10.1111/plb.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaplan F, Guy CL. β-Amylase induction and the protective role of maltose during temperature shock. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1674–1684. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.040808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klotke J, Kopka J, Gatzke N, Heyer AG. Impact of soluble sugar concentrations on the acquisition of freezing tolerance in accessions of Arabidopsis thaliana with contrasting cold adaptation – evidence for a role of raffinose in cold acclimation. Plant Cell Environ. 2004;27:1395–1404. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2004.01242.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hameed A, Iqbal N, Malik SA. Mannose-induced modulations in antioxidants, protease activity, lipid peroxidation, and total phenolics in etiolated wheat leaves. J. Plant. Growth Regul. 2009;28:58–65. doi: 10.1007/s00344-008-9076-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hameed A, Iqbal N, Malik SA. Effect of d-mannose on antioxidant defense and oxidative processes in etiolated wheat coleoptiles. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2013;36:161–167. doi: 10.1007/s11738-013-1396-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goto, S. et al. Organizing and computing metabolic pathway aata in terms of binary relations. Pacific Symposium Biocomput. 1997, 175-186 (1997). [PubMed]

- 55.Hoffman L, DaCosta M, Ebdon JS, Watkins E. Physiological changes during cold acclimation of perennial ryegrass accessions differing in freeze tolerance. Crop Sci. 2010;50:1037–1047. doi: 10.2135/cropsci2009.06.0293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Conklin PL. Recent advances in the role and biosynthesis of ascorbic acid in plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2001;24:383–394. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00686.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shelden MC, Dias DA, Jayasinghe NS, Bacic A, Roessner U. Root spatial metabolite profiling of two genotypes of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) reveals differences in response to short-term salt stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2016;67:3731–3745. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Capell T, Bassie L, Christou P. Modulation of the polyamine biosynthetic pathway in transgenic rice confers tolerance to drought stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:9909–9914. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306974101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rohloff J, et al. Metabolite profiling reveals novel multi-level cold responses in the diploid model Fragaria vesca (woodland strawberry) Phytochemistry. 2012;77:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim TE, Kim SK, Han TJ, Lee JS, Chang SC. ABA and polyamines act independently in primary leaves of cold‐stressed tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) Physiol. Plant. 2002;115:370–376. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1150306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Urano K, et al. Arabidopsis stress-inducible gene for arginine decarboxylase AtADC2 is required for accumulation of putrescine in salt tolerance. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 2004;313:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Obata T, Fernie AR. The use of metabolomics to dissect plant responses to abiotic stresses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012;69:3225–3243. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-1091-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joshi V, Joung JG, Fei Z, Jander G. Interdependence of threonine, methionine and isoleucine metabolism in plants: accumulation and transcriptional regulation under abiotic stress. Amino Acids. 2010;39:933–947. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0505-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hayat S, et al. Role of proline under changing environments. Plant Signal. Behav. 2012;7:1456–1466. doi: 10.4161/psb.21949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maruyama K, et al. Metabolic pathways involved in cold acclimation identified by integrated analysis of metabolites and transcripts regulated by DREB1A and DREB2A. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1972–1980. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.135327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.