Abstract

Many cancer cells require more glycolytic adenosine triphosphate production due to a mitochondrial respiratory defect. However, the roles of mitochondrial defects in cancer development and progression remain unclear. To address the role of transcriptomic regulation by mitochondrial defects in liver cancer cells, we performed gene expression profiling for three different cell models of mitochondrial defects: cells with chemical respiratory inhibition (rotenone, thenoyltrifluoroacetone, antimycin A, and oligomycin), cells with mitochondrial DNA depletion (Rho0), and liver cancer cells harboring mitochondrial defects (SNU354 and SNU423). By comparing gene expression in the three models, we identified 10 common mitochondrial defect–related genes that may be responsible for retrograde signaling from cancer cell mitochondria to the intracellular transcriptome. The concomitant expression of the 10 common mitochondrial defect genes is significantly associated with poor prognostic outcomes in liver cancers, suggesting their functional and clinical relevance. Among the common mitochondrial defect genes, we found that nuclear protein 1 (NUPR1) is one of the key transcription regulators. Knockdown of NUPR1 suppressed liver cancer cell invasion, which was mediated in a Ca2+ signaling–dependent manner. In addition, by performing an NUPR1-centric network analysis and promoter binding assay, granulin was identified as a key downstream effector of NUPR1. We also report association of the NUPR1–granulin pathway with mitochondrial defect–derived glycolytic activation in human liver cancer.

Conclusion:

Mitochondrial respiratory defects and subsequent retrograde signaling, particularly the NUPR1–granulin pathway, play pivotal roles in liver cancer progression.

A hallmark of cancer cells is a reprogrammed bioenergetic and biosynthetic state.1 The most striking bioenergetic reprogramming is an impaired capacity for mitochondrial respiration accompanied by glycolysis, even under normoxic conditions. This phenomenon supports the proposed Warburg effect.2,3 The mitochondrial respiratory defect found in cancer cells is mostly associated with mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) damage caused by deletions and/or point mutations and is also related to the imbalanced biogenesis or degradation of mitochondria as described in many types of cancer.4-7 However, whether mitochondrial defects are merely an epiphenomenon accompanied by inevitable hypoxia due to fast tumor growth or have causative or correlative roles in the course of cancer development remains unclear. Interestingly, several recent studies have described mitochondrial dysfunction promoting metastatic properties in many cancer types, including breast cancer, gastric cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).8-10 These findings suggest that mitochondrial defects play critical roles in tumor progression.

Altered mitochondrial metabolism communicates with the nucleus through “mitochondrial retrograde signaling,” which has been reported to play important roles in diverse mitochondrial damage–associated pathological conditions, such as cancer, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular diseases.11-13 The retrograde signaling begins with several key events: the release of diffusible reactive oxygen species (ROS), transporter-mediated release of Ca2+, and changes in the oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide/reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide and adenosine diphosphate/adenosine triphosphate ratios.14 These signals are then transmitted into the nucleus by activating several cytosolic transducers through redox modification; binding with small molecules, such as Ca2+, oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and adenosine monophosphate; and post-translational modification.14,15 In turn, certain transcription factors or cofactors, including PGC1α, Sirt1, mammalian target of rapamycin, and cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element–binding protein, are activated and/or translocalize into the nucleus, switching on the transcriptional reprogramming.14 Although the functional roles of retrograde signaling are not yet fully understood, the signals have been shown to trigger diverse cellular reconfigurations, including restoration of mitochondrial function (recovery); activation of an alternative energy supply (adaptive strategy); modification of cellular function, such as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (programmed strategy); and/or alteration of cellular destination (cell fate control) to death, senescence, or proliferation.14,16-19 Therefore, the mitochondrial retrograde signaling–mediated transcriptional reprogramming and resulting cellular reconfigurations may also play pivotal roles in tumor progression. This hypothesis is supported by the association of intermittent or sustained mitochondrial dysfunction with various tumor activities.20-22

In the present study, we aimed to identify the key regulatory mechanisms responsible for the mitochondrial defects and retrograde signals in cancer progression. We employed liver cancer cells because our previous studies demonstrated the mitochondrial defect in liver cancer cells.23,24 By performing gene expression profiling in three independently designed models harboring mitochondrial defects (hepatoma cells with low respiratory activity, i.e., tumoral defect; cells with pharmacological respiratory inhibition, i.e., functional defect; and cancer cells with mtDNA depletion, i.e., genetic defect), we identified 10 common mitochondrial defect (CMD) genes. We demonstrate the contribution of the CMD genes to HCC and a novel CMD-mediated regulatory mechanism, particularly the nuclear protein 1–granulin (NUPR1–GRN) pathway, thereby emphasizing that mitochondrial defect and subsequent retrograde signals for transcriptional reprogramming play pivotal roles in the progression of HCC.

Materials and Methods

Cell Cultures and Developing Mitochondrial Defect Conditions.

Human liver cancer cells (SNU354, SNU387, and SNU423) were purchased from Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea) and cultured in GIBCO Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% GIBCO fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen) and GIBCO antibiotics (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Chang cell clones were isolated by single-cell dilution and expansion of Chang cell (ATCC, Rockville, MD), and a Chang clone with strong hepatic characteristics (Ch-L) validated by confirming liver-specific expression of albumin and carbamoyl-phosphate synthase-1 was used for this study (Supporting Fig. S1). The Ch-L clone was cultured in GIBCO Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% GIBCO fetal bovine serum.

Three different mitochondrial defect conditions were developed. For the “tumoral defect,” hepatoma cells (SNU354 and SU423) harboring a mitochondrial defect were employed. The “functional defect” condition was generated by exposing the Ch-L clone to subcytotoxic doses of respiratory inhibitors including rotenone (complex I inhibitor), thenoyltrifluoroacetone (complex II inhibitor), antimycin A (complex III inhibitor), and oligomycin (complex V inhibitor) for 12 hours, as described.25 Rho0 clone of MDA-MB435, of which the mtDNA was depleted, was kindly provided by K.K. Singh26 and used for the “genetic defect” condition.

Human HCC Specimens.

HCC tumors and surrounding tissues were obtained from 23 HCC patients (age range 34-70 years) during the period August 2008 to January 2010 at Ajou University Hospital with informed consent through the Ajou Institutional Review Board. No patient in the current study received chemotherapy or radiation therapy before the surgery.

Gene Expression Profiling and Data Analysis.

Total RNA was amplified and purified using the Ambion Illumina RNA amplification kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) to yield biotinylated complementary DNA (cDNA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 550 ng of total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using deoxythymidine oligomer primers. Second-strand cDNA was synthesized, in vitro transcribed, and labeled with biotinylated deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate. Labeled cDNA samples (750 ng) were hybridized to each human HT-12 expression v.4 bead array, and the array signal was detected according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA). Raw data were filtered by detection (P < 0.05) and further processed by log2 transformation and quantile normalization. Gene ontology analysis and signaling pathway analysis were performed by using DAIVD software.27 For gene set enrichment analysis of the identified gene signature for each patient, the enrichment score (ES) was calculated by applying nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test analysis. The −log10-transformed P values were used as the ES, and the significance of the ES was determined by P < 0.05. For clinical validation, two independent data sets of HCC gene expression profiles of cohort 1 (GSE4024, GSE1898; n = 139) and cohort 2 (GSE14520, n = 247) were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database and preprocessed by gene and array centering. All data processing and survival analyses were performed using R/Bioconductor packages.

Measurement of Cellular Oxygen Consumption Rate.

To monitor mitochondrial respiratory activity, the cellular oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured using the Seahorse XF24 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, Inc., North Billerica, MA) as described.28

Cell Invasion Assay.

Cell invasion assay was performed with Transwell Permeable Supports (8 μm pore size; Corning, Acton, MA) which was precoated with 7% Growth Factor Reduced BD Matrigel Matrix (Becton Dickinson Labware, Franklin Lakes, NJ) as described.23

Generation of Cell Clones Stably Expressing NUPR1 Short Hairpin RNAs.

To produce recombinant lentivirus harboring NUPR1 short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs), 293T virus packaging cell was transfected with pLKO.1-puro plasmids containing shRNA sequences for NUPR1 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). DNA sequences of shRNAs for NUPR1 and negative control are shown in Supporting Table S1. Medium containing recombinant lentivirus was harvested 3 days after transfection and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter unit (Millipore Corp.; UFC 920008). Filtered medium was mixed with polybrene (8 μg/mL; Sigma-Aldrich) for facilitated infection and stored at 80°C. Cells were infected with the recombinant lentiviruses, and clones expressing the shRNAs were selected with 8 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Construction and Transfection of Recombinant cDNA Plasmids.

To construct pcDNA3-NUPR1-hemagglutinin (HA) and pcDNA3-GRN-HA, a conventional cloning procedure was applied. Briefly, target cDNAs were amplified by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with the primer sets 5′-TGGATCCACCATGGCCACCTTCCCA and 5′-TCTCGAGGCGCCGTGCCCCT for NUPR1 and 5′-TGAATTCACCATGTGGACCCTGGTG and 5′-TCTCGAGCAGCAGCTGTCTCAAG for GRN. Total cDNAs of the Ch-L clone were used as a template for NUPR1, and commercial pCMV-SPORT6-GRN plasmid (Korea Human Gene Bank, Daejeon, Korea) was for GRN. An NUPR1 cDNA fragment was inserted between BamHI and XhoI sites and GRN cDNA fragment, between EcoRI and XhoI sites of the pcDNA3-HA vector which was previously constructed.24 The inserted cDNA fragments were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

To introduce plasmids into cells, cells were transfected with the plasmids using FuGENE HD (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Introduction of Small Interfering RNAs Into Cells.

To introduce target small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) into cells, cells were transfected with the siRNA duplexes using Oligofectamine Reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Target siRNAs were generated from Bioneer (Seoul, Korea), and their sequences are listed in Supporting Table S1.

Construction of Promoter-Luciferase Reporter Plasmid and Promoter Assay.

A human GRN promoter region of 2895 bp (−2894 to +58, NG_007886) was cloned by targeted polymerase chain reaction (PCR) against total genomic DNA of Ch-L using a primer set, 5′-ATACGCGTCAGAGGAAGGCTCTG and 5′- GCGAGATCTCCTGGAATGCTGTGTT. Amplified GRN promoter region was inserted between BglII and MluI sites of pGL3-basic vector (Promega, Fitchburg, WI). After construction, the inserted promoter was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

To monitor the GRN promoter activity, cells were transfected with 1 μg DNA (700 ng of pcDNA3 or pcDNA3-NUPR1-HA, 250 ng of the cloned reporter plasmid, and 50 ng of thymidine kinase promoter–driven Renilla luciferase plasmid as an internal control) using FuGENE HD reagent. After 2 days, luciferase activity of cell extracts was measured by Synergy 2 Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT) according to the protocol provided with the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Luciferase activities were normalized by the Renilla luciferase activity.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay.

A chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed according to the ChIP Assay kit protocol (Upstate Biotechnology Inc., Lake Placid, NY) with slight modification. Briefly, cells were treated with 1% formaldehyde to crosslink stably the DNA-interacting proteins to genomic DNA. After lysis, the lysates were briefly sonicated to shear genomic DNA and centrifuged at 15871 × g for 10 minutes. An aliquot was saved for input control; the other aliquots were subjected to ChIP using NUPR1 antibody and protein-G agarose bead. The eluted DNA was purified using a DNA extraction kit (Inclone Biotech, Seoul, Korea), and the specific promoter region was amplified by PCR with the primer sets described in Supporting Table S1.

Measurement of Cytosolic Calcium Levels.

To estimate cytosolic calcium levels, Fluo-3 (Molecular Probes Corp., Eugene, OR) fluorogenic probes were used. Briefly, cells were incubated in medium containing 2.5 μM Fluo-3 for 20 minutes at 37°C. Stained cells were washed, resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline, and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS Vantage; Becton Dickinson Corp.). A mean arbitrary fluorescence unit of 10,000 cells was obtained and expressed as a percentage of control.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNAs were isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen), and total cDNAs were prepared using AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega). PCR was performed with 50 cycles of the reaction involving 95°C for 15 seconds, 58°C for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 20 seconds, using Thunderbird SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocol provided. The PCR primer sets were produced by Bioneer as listed in Supporting Table S1. Target messenger RNA (mRNA) expressions were normalized by ß-actin mRNA level.

Western Blot Analysis.

Western blot analysis was performed using standard procedures. Antibodies against NUPR1 (sc-23283), GRN (sc-377036), and β-actin (sc-1616) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX). Antibodies for HA (2367) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Antibody for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; LF-PA0018) was obtained from AbFrontier (Seoul, Korea). Antibodies against for NDUFA9 of complex I (A21344), flavoprotein (A11142) of complex II, UQCRC2 of complex III (A11143), MTCOII of complex IV (A6404), and ATP5A1 of complex V (A21350) were from Molecular Probes Corp.

Results

Characterization of Mitochondrial Respiratory Defect–Linked Transcriptional Reprogramming in Liver Cancer Cells.

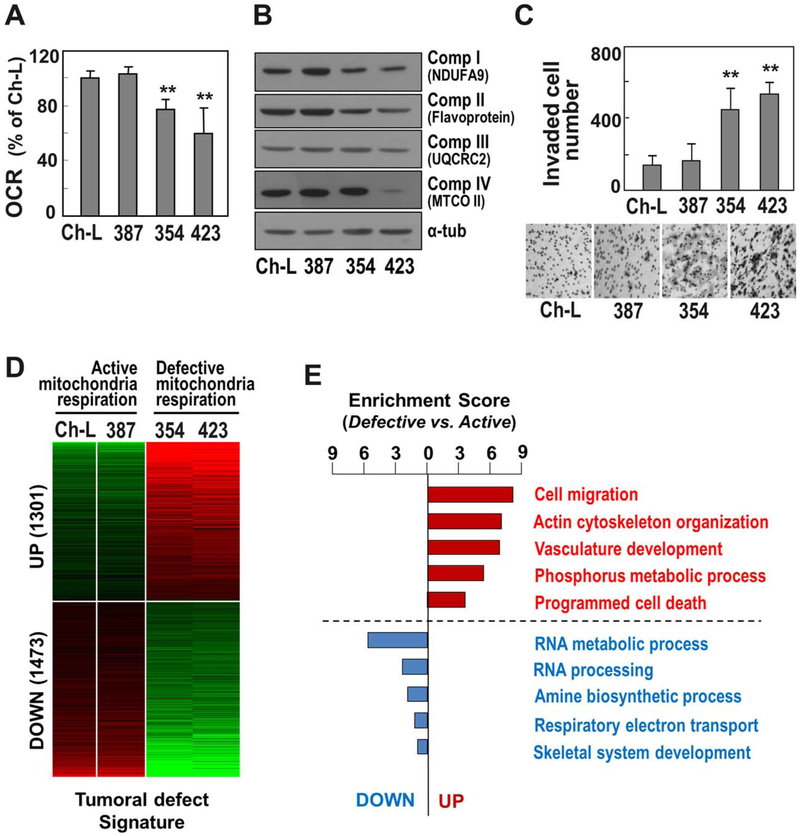

First, we examined the mitochondrial respiratory status and cell invasion activities of three different liver cancer cell lines (SNU387, SNU354, and SNU423). A Ch-L clone was isolated and characterized to possess liver-specific genes (Supporting Fig. S1). This clone was used as a control with active mitochondria. SNU387 cells had an active OCR similar to Ch-L, whereas SNU354 and SNU423 cells had decreased OCRs, implying mitochondrial respiratory defects (Fig. 1A). To confirm the presence of mitochondrial respiratory defects, the expression levels of some mitochondrial complex proteins (I, II, III, and IV) were monitored. SNU354 and SNU423 cells expressed the mitochondrial complex proteins at lower levels than Ch-L and SNU387 (Fig. 1B). To evaluate the association of these mitochondrial defects with hepatoma malignancy,23 we monitored invasiveness. As expected, cells with mitochondrial defects (i.e., SNU354 and SNU423 cells) exhibited greater invasiveness than SNU387 and Ch-L cells (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results suggest that SNU354 and SNU423 cells have cancer cell invasiveness associated with impaired mitochondrial respiration, making them an appropriate model for further detailed investigation of the causative role of mitochondrial defects in tumor progression.

Fig. 1.

Gene expression changes of invasive hepatoma cells with mitochondrial defects. Three different SNU hepatoma cell lines (SNU354, SNU387, and SNU423) and the Ch-L clone were cultured for 2 days to maintain an exponentially growing state. (A) Cellular OCR was measured using the XF analyzer as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Western blot analyses for mitochondrial respiratory subunits. (C) Cell invasion activity was performed using Matrigel-coated Transwell as described in Materials and Methods. Invaded cells were counted. Representative images for invaded cells are shown in the lower panel. **P < 0.01 versus Ch-L by Student t test. (D) Heatmap of the differentially expressed genes between hepatoma cells with active and defective mitochondrial respiration (mitochondrial “tumoral defect” signature). By performing gene expression profiling, a total of 2774 commonly deregulated genes were identified with greater than two-fold differences. Of these, 1301 genes were commonly up-regulated in the cells with defective mitochondria compared to those of the cells with active mitochondria, whereas 1473 genes were down-regulated. (E) Functional enrichment analysis for the commonly up-regulated genes (1301 genes) and down-regulated genes (1473 genes). Enrichment scores indicate the −log10-transformed P values which were calculated from the gene set enrichment analysis.

In order to investigate the transcriptomic regulation linked to mitochondrial damage in hepatoma cells, we performed gene expression profiling for SNU354 and SNU423 cells and identified genes differentially expressed in Ch-L and SNU387 cells by applying a cutoff of 1.4-fold difference. A total of 1301 genes were up-regulated and 1473 genes were down-regulated (Fig. 1D), named as “tumoral defect” genes. The functional gene set enrichment analysis revealed that the genes related to cell migration and cytoskeleton organization were abundantly up-regulated in SNU354 and SNU423 cells (Fig. 1E), implying that the up-regulated genes may be responsible for the acquisition of an aggressive phenotype and regulated by the mitochondrial defect.

Identification of CMD Genes.

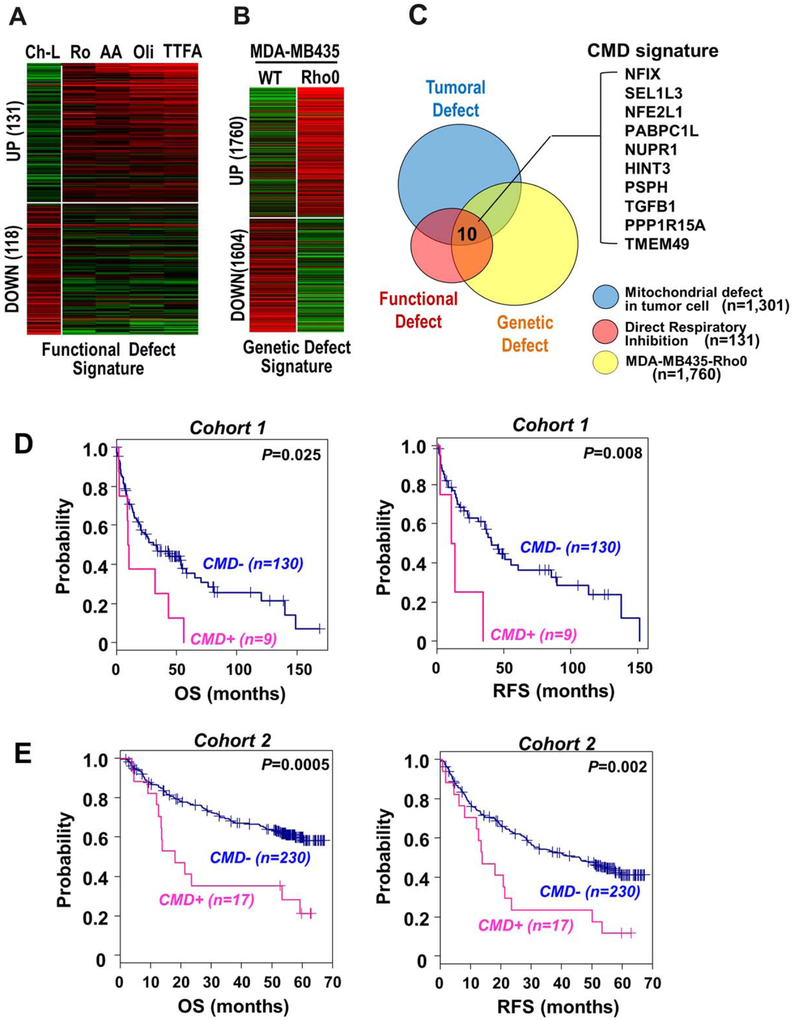

To select the genes directly regulated by the mitochondrial respiratory defect from the 1301 up-regulated genes, we developed two additional cell conditions with mitochondrial defect: (1) direct “functional defect” by exposing cells to several pharmacological mitochondrial respiratory inhibitors and (2) “genetic defect” by employing Rho0 cells in which the mtDNA was depleted. Gene expression profiling of the direct functional defect condition revealed 131 up-regulated and 118 down-regulated genes common to the direct respiratory inhibitions (Fig. 2A). Comparison of gene expression in Rho0 cells and the parental MDA-MB435 cell line revealed 1760 up-regulated and 1604 down-regulated genes in Rho0 cells (Fig. 2B). By comparing the three independent mitochondrial defect models (tumoral defect, functional defect, and genetic defect), we eventually extracted 10 CMD genes: NFIX, SEL1L3, NFE2L1, PABPC1L, NUPR1, HINT3, PSPH, TGFB1, PPP1R15A, and TMEM49 (Fig. 2C). These 10 genes may be directly induced in response to mitochondrial damage in liver cancer cells independent of the stimuli.

Fig. 2.

Identification of CMD gene signature. (A) Ch-L clone was challenged with four different respiratory inhibitors for 12 hours: 5 μM rotenone, 200 μM thenoyltrifluoroacetone, 5 μM antimycin A, or 5 μM oligomycin. By comparing the gene expression profiles of the cells, 131 commonly up-regulated genes were obtained as the mitochondrial “functional defect” signature. (B) By comparing the gene expression profiles of MDA-MB435 and its Rho0 cells, 1760 up-regulated genes were obtained as the mitochondrial “genetic defect” signature. (C) From the three independent mitochondrial defect conditions (tumoral, genetic, and functional defect), 10 genes were extracted as a CMD signature. (D,E) Kaplan-Meier plot analyses of overall survival (left panel) and relapse-free survival (right panel) from the independent public data sets (GSE4024 and GSE14520), respectively. Patients were stratified based on the expression status of the CMD signature (CMD_UP versus CMD_DOWN). Abbreviations: AA, 5 μM antimycin A; Oli, 5 μM oligomycin; OS, overall survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; Ro, rotenone; TTFA, 200 μM thenoyltrifluoroacetone; WT, wild type.

To address the clinical significance of the CMD genes, we analyzed the correlation between enriched expression of these genes and clinical outcomes, such as overall survival and recurrence-free survival, using two independent liver cancer cohorts: cohort 1 (GSE4024, n = 139) and cohort 2 (GSE14520, n = 247). Stratifying the patients based on the ES of CMD genes (ES >1.3, P < 0.05), we found that the patients with enriched expression of the CMD genes had poor prognosis with shorter overall survival (P = 0.025 and P = 0.0005 in cohorts 1 and 2, respectively) and recurrence-free survival (P = 0.008 and P = 0.0002 in cohorts 1 and 2, respectively) (Fig. 2D,E). In addition, we further evaluated the association of CMD expression with early recurrence of HCC within 24 months after surgical resection. By applying Fisher’s exact test, we found that CMD expression status was correlated with the incidence of early recurrence of HCC in cohort 2 (odds ratio = 5.62, P = 0.00015) as shown in Supporting Table S2. Although analysis of cohort 1 did not reach statistical significance (odds ratio = 5.51, P = 0.184), this is probably due to the small number of recurrence data. These results imply that CMD expression is potentially linked with invasive and metastatic properties of hepatoma, also indicating its prognostic relevance. This is further supported by a previous report that metastatic recurrence occurs within 2 years after resection.29

NUPR1, NFIX, and NFE2L1 Control the Invasiveness of Liver Cancer Cells.

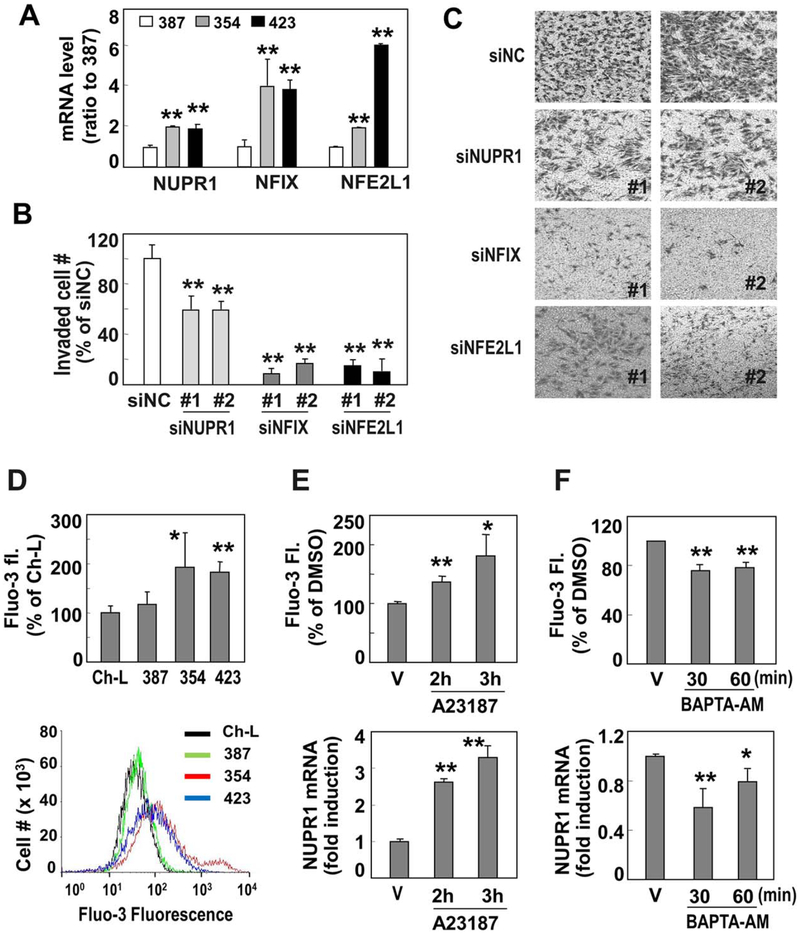

The CMD genes included three transcription regulators (TRs): NUPR1, NFIX, and NFE2L1. Thus, we hypothesized that these genes play critical roles as major primary response genes in controlling the invasive activity of liver cancer cells by inducing additional secondary effectors. After confirming the mRNA expression levels of the three TRs in the liver cancer cells using quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 3A), we evaluated the involvement of the TRs in the invasiveness of cancer cells by performing cell invasion assays following siRNA-mediated knockdown. The invasion activity of SNU354 cells was significantly diminished by the siRNA-mediated knockdown of the TRs (Fig. 3B,C). The knockdown effects of the individual TR-specific siRNAs were validated by quantitative RT-PCR (Supporting Fig. S2). In addition, persistent suppression of the TRs by shRNAs significantly diminished their cell invasion activity without altering the cell growth rate (Supporting Fig. S3). These results indicate that the three TRs are key primary factors induced in response to mitochondrial defects that regulate liver cancer cell invasiveness, probably by synthesizing secondary effector molecules.

Fig. 3.

Among 10 CMD genes, NUPR1 is a key TR to control hepatoma cell invasiveness and is regulated by cytoplasmic Ca2+ increase. (A) Messenger RNA levels of three common TRs in SNU hepatoma cells were validated by RT-PCR. **P < 0.01 versus SNU387 by Student t test. (B) SNU354 cells were transfected by siRNAs for NUPR1, NFIX, and NFE2L1 and subjected to invasion assay. **P< 0.01 versus nonspecific siRNA (siNC) by Student t test. (C) Representative images of the invasion assay are shown. (D) Cytosolic Ca2+ levels of SNU hepatoma cells (SNU354, SNU387, and SNU423) were monitored by flow-cytometric analysis after staining cells with Fluo-3 fluorogenic dye and compared with that of Ch-L clone. **P < 0.01 and *P< 0.05 versus Ch-L by Student t test. Representative cell distributions of Fluo-3-stained cells are shown in the lower panel. (E) SNU387 cells were treated with 20 μM A23187 for the indicated time periods. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels using Fluo-3 fluorogenic dye (upper panel) and NUPR1 mRNA levels by RT-PCR (lower panel) were monitored. (F) SNU354 cells were treated with 5 μM BAPTA-AM for the indicated time periods. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels (upper panel) and NUPR1 mRNA levels (lower panel) were examined. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus dimethyl sulfoxide–treated cells (vehicle) by Student t test. Abbreviations: BAPTA-AM, 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N’,N’-tetraacetic acid acetoxymethyl ester; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; V, vehicle.

Among the three CMD TRs, NUPR1 has often been implicated in tumor malignancy, such as metastasis and chemotherapeutic resistance.30 However, the direct link between NUPR1 and mitochondrial defects is not clearly understood. Thus, we planned to elucidate the molecular links between NUPR1 and mitochondrial defects. Calcium and ROS release from damaged mitochondria are known as key retrograde signal initiators.14 However, when the Ch-L clone was exposed to exogenous H2O2 (200 μM) for 6 hours, NUPR1 mRNA was not induced but increased only after 3-day exposure together with mitochondrial defect triggered by the exogenous ROS, implying that ROS may not be the direct regulator of NUPR1 transcription (data not shown). Therefore, we examined the involvement of Ca2+ in NUPR1 expression. Invasive SNU hepatoma cells with mitochondrial defects (SNU354 and SNU423 cells) had higher cytosolic Ca2+ levels than the other cells with active mitochondria (Fig. 3D). When SNU387 cells (low cytosolic calcium level with active mitochondria) were treated with 20 μM A23187, a calcium ionophore known to increase cytosolic Ca2+,31 NUPR1 mRNA expression was significantly augmented (Fig. 3E). In contrast, scavenging cytosolic Ca2+ in SNU354 cells using 5 μM 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)-ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid acetoxymethyl ester (BAPTA-AM), a membrane-permeable calcium scavenger,31 significantly diminished NUPR1 mRNA expression (Fig. 3F). These results support the idea that NUPR1 transcription is regulated by mitochondrial defect-mediated Ca2+ signaling in invasive SNU hepatoma cells.

Granulin Is a Key Transcriptional Downstream Target of NUPR1.

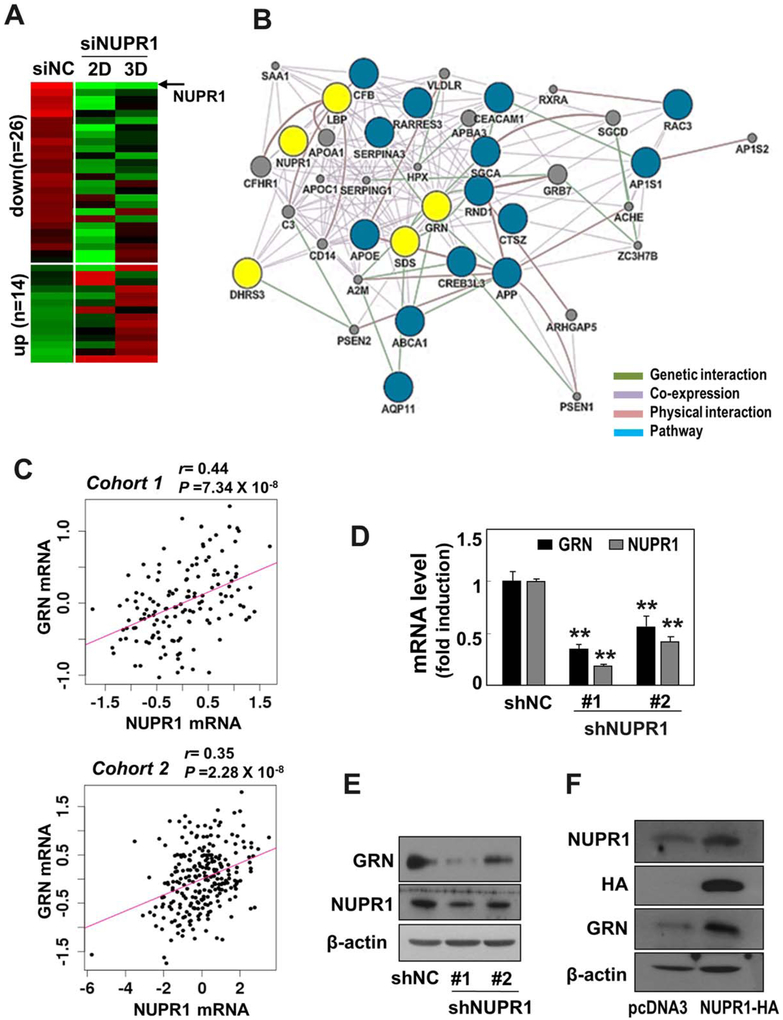

Next, we aimed to determine which molecules are induced as the downstream effectors of NUPR1 in the regulation of hepatoma cell invasiveness. To address this, SNU354 cells possessing high NUPR1 expression were transfected with NUPR1 siRNA and then subjected to gene expression profiling. The siRNA-mediated NUPR1 knockdown effectively diminished NUPR1 mRNA levels at both 2 and 3 days (Supporting Fig. S4A). Gene expression profiling revealed that 26 genes were commonly down-regulated with greater than 1.4-fold difference, implying that they are putative downstream targets of NUPR1 (Fig. 4A). It is noteworthy that the CMD signature was not included in these downstream effectors of NUPR1. This was probably due to the selection of the 10 CMD genes by including the direct “functional defect” genes which responded primarily to 12-hour treatment of respiratory inhibitors. To pinpoint the most probable functional targets among the 26 genes, network analysis was performed using GeneMAINA software implemented in Cytoscape plugin (Fig. 4B).32 Of the potential target genes networked with NUPR1, four genes (LBP, DHRS3, SDS, and GRN) had the largest interaction partnership, implying their functional relevance as NUPR1 targets.

Fig. 4.

GRN is a key downstream effector molecule of NUPR1. (A) SNU354 cells were transfected with siRNA for NUPR1 for 2 and 3 days, followed by cDNA microarray analysis. A heatmap of commonly deregulated genes is shown. Twenty-six genes were down-regulated and 14 genes were up-regulated. (B) A network for the 26 commonly down-regulated genes was constructed using GeneMania software, showing genetic interaction, coexpression link, physical interaction, and pathway link. By removing the genes not connected to the network, 19 out of the 26 genes are included in the network (blue and yellow circles). Of the first neighbor genes connected directly to NUPR1, the four genes harboring the largest interaction partners are indicated as potential targets for NUPR1 (yellow circle). (C) Correlation between the expressions of GRN and NUPR1 was shown in cohort 1 (upper panel) and cohort 2 (lower panel), respectively. (D,E) SNU354 cells were infected with recombinant lentiviruses harboring shRNAs for NUPR1, and clones stably expressing the shRNAs were isolated. (D) Messenger RNA levels of GRN and NUPR1 were examined by qRT-PCR. **P < 0.01 versus shNC by Student t test. (E) Protein levels by western blot analysis were also examined. (F) SNU387 cells were transfected with pcDNA3–NUPR1–HA plasmid for 2 days. Protein expression levels of NUPR1 and GRN were examined by western blot analysis.

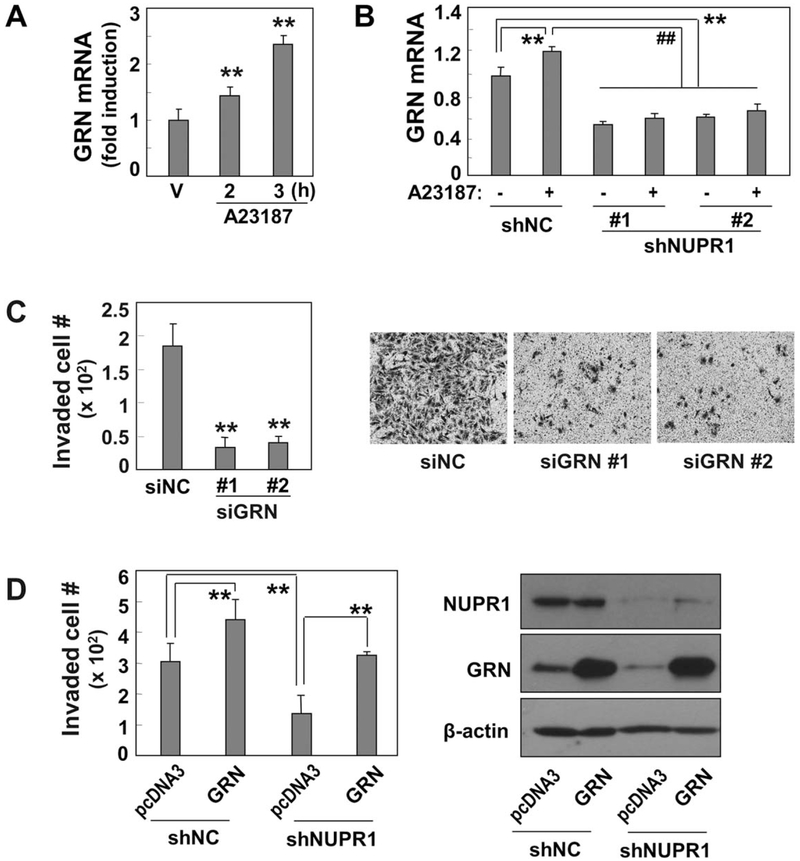

Among these four genes, GRN was recently reported to have tumorigenic activity with high expression in many cancer types, including liver cancer.33-35 In addition, we found that GRN expression is highly correlated with NUPR1 expression levels in both cohort 1 (r = 0.44, P = 7.34 × 10 −8, Pearson’s correlation test) and cohort 2 (r = 0.35, P = 2.28 × 10−8) data sets (Fig. 4C), implying their functional association. Therefore, we further evaluated whether GRN is a functional downstream target of NUPR1. Knockdown of NUPR1 by shRNA significantly diminished GRN expression at both the mRNA and protein levels in invasive SNU354 cells (Fig. 4D,E). In contrast, overexpression of NUPR1 in SNU387 cells effectively augmented GRN expression (Fig. 4F), indicating that GRN is a downstream transcriptional target of NUPR1. We also examined whether GRN expression is controlled by Ca2+-mediated NUPR1 expression. Increasing cytosolic Ca2+ levels in SNU387 cells with A23187 treatment clearly augmented GRN mRNA expression (Fig. 5A). A23187 treatment in SNU354 cells (possessing high levels of cytosolic Ca2+ and GRN expression) further enhanced GRN transcription but with only a minor increase. However, this increase, as well as the basal level, was effectively abolished by NUPR1 knockdown (Fig. 5B), implying the involvement of calcium-mediated NUPR1 transcription in GRNexpression.

Fig. 5.

GRN regulates hepatoma cell invasion activity through Ca2+-mediated NUPR1 expression. (A) GRN mRNA levels were monitored by qRT-PCR after SNU387 cells were exposed to 20 μM A23187 for the indicated time periods. (B) SNU354 cells stably harboring NUPR1 shRNA or nonspecific shRNA (shNC) were exposed to 20 μM A23187 for 6 hours. GRN mRNA levels were examined by qRT-PCR. (C) SNU354 cells were transfected with siRNA for GRN, and cell invasion activity was monitored using Matrigel-coated Transwell assay. Invaded cells were counted (left panel), and representative images of the invaded cells are shown (right panel). (D) SNU354 cells stably harboring NUPR1 shRNA were transfected with pcDNA3-GRN plasmid and subjected to cell invasion assay. Invaded cells were counted (left panel), and protein levels were validated by western blot analysis (right panel). **P < 0.01 versus siNC, shNC, pcDNA3, or dimethyl sulfoxide vehicle by Student t test; ##P < 0.01 versus A23187-treated cells.

To ascertain the contribution of GRN to hepatoma cell invasiveness, we performed a cell invasion assay following GRN knockdown in SNU354 cells. GRN knockdown by shRNA significantly reduced the invasion activity of SNU354 cells (Fig. 5C). The knockdown efficiency of the shRNA targeting GRN was confirmed (Supporting Fig. S4B). In contrast, overexpression of GRN in SNU354 cells further increased the invasion activity and effectively recovered the invasiveness suppressed by NUPR1 knockdown (Fig. 5D). These results strongly indicate that NUPR1-mediated hepatoma cell invasion manifests through GRNexpression.

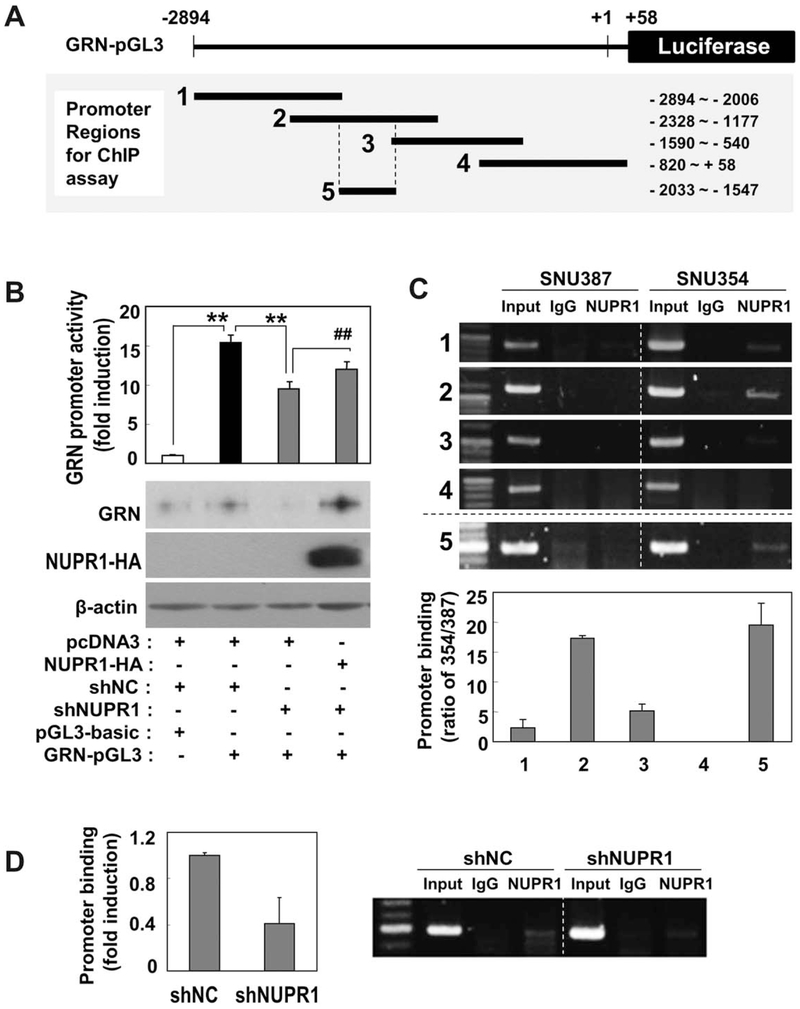

NUPR1 Regulates GRN Transcription by Binding the GRN Promoter Region From −2033 to −1547.

To further investigate the mechanisms underlying the regulation of NUPR1 in GRN transcription, we examined whether NUPR1 protein regulates the promoter activity of GRN. To measure the promoter activity, we constructed a luciferase reporter plasmid containing 2894 bp of the upstream promoter region of GRN, which includes its transcription start site (Fig. 6A). When SNU354 cells were transfected with this reporter plasmid, the GRN promoter region was enough to activate luciferase transcription. This activated GRN promoter activity was significantly suppressed by NUPR1 knockdown and recovered by reexpression of NUPR1 (Fig. 6B). To map the NUPR1 binding site within the promoter region, we performed ChIP analyses with the NUPR1 antibodies against each of four different GRN promoter regions (Fig. 6A, bottom) using SNU354 cells. NUPR1 strongly bound to promoter region 2 and weakly bound to regions 1 and 3 in SNU354 cells compared to SNU387 cells (Fig. 6C). Therefore, we assumed that the specific region (−2006 to −1590) within region 2, which does not overlap with regions 1 and 3, may contain a core NUPR1 binding site. The consensus sequence for NUPR1 binding was not clearly identified, but NUPR1 is a high mobility group (HMG) I/Y-like protein that binds an A/T-rich sequence, e.g., (TATT)n or (AATA)n, which is the consensus sequence for HMG-I/Y binding.36 Therefore, we selected region 5 (−2033 to −1547), which had a 56% A/T-rich sequence with five dispersed AATA or TATT units (Supporting Fig. S5), and subjected it to the ChIP assay. This region was sufficient for NUPR1 binding (Fig. 6C). Finally, we confirmed that NUPR1 binding to region 5 was significantly diminished by NUPR1 knockdown in SNU354 cells (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that enhanced NUPR1 expression activates transcription of GRN by binding the GRN promoter, mainly the region from −2033 to −1547.

Fig. 6.

NUPR1 regulates GRN promoter activity through binding its specific promoter region. (A) Schematic model of GRN-pGL3 reporter plasmid containing promoter region of GRN from −2894 to +58. Promoter regions used for ChIP assay are marked in the bottom panel. (B) SNU354 cells stably harboring NUPR1 shRNA were transfected with pcDNA3-GRN plasmid together with GRN-pGL3 reporter plasmid and then subjected to luciferase promoter assay as described in Materials and Methods. All experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated at least twice. Protein levels were validated by western blot analysis (lower panel). ** or ##P < 0.01 versus the indicated control by Student t test. (C) ChIP promoter binding assay was performed against the indicated GRN promoter regions using NUPR1 antibody. Representative gel images (upper panel) and quantified results (lower panel) are shown. (D) ChIP assay was performed against promoter region 5 after NUPR1expression was suppressed with shRNA in SNU354 cells. Quantified results (right panel) and representative gel images (left panel) are shown. Abbreviation: IgG, immunoglobulin G.

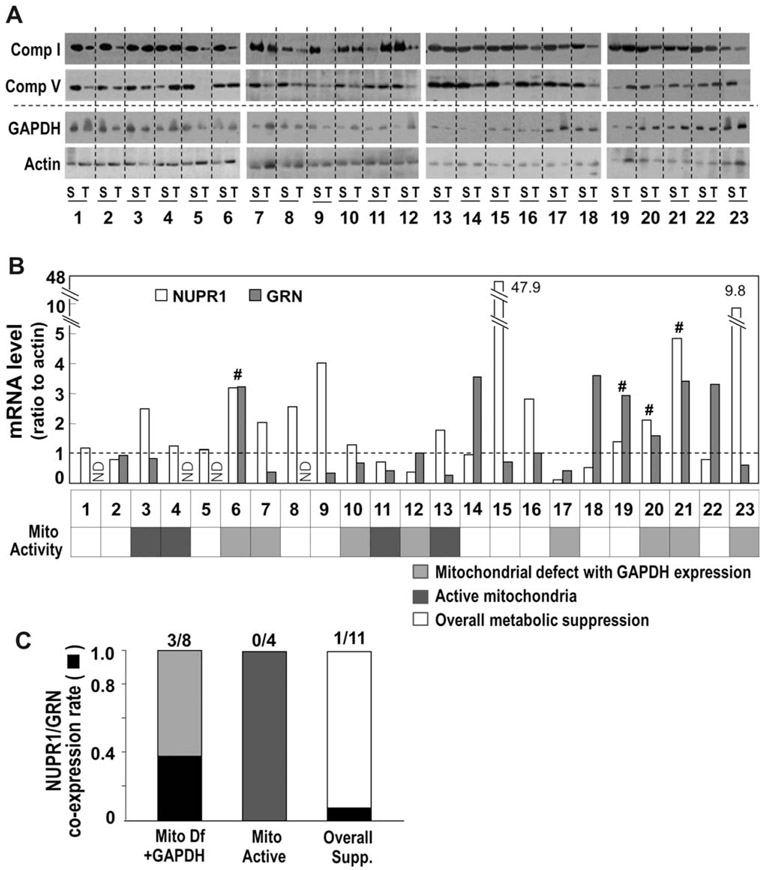

Mitochondrial Defect Is Associated With Increased Expression of NUPR1 and GRN in Human HCC.

Finally, we examined whether increased coexpression is associated with mitochondrial defects using 23 paired human HCC samples and their surrounding nontumoral tissue. Mitochondrial activity was determined by the protein levels of a complex I subunit and a complex V subunit. We also examined the expression level of GAPDH, a glycolytic enzyme reported to have enhanced expression in cancer,37 in order to evaluate whether the decreased mitochondrial expression is truly linked to glycolytic activation or overall metabolic suppression. Among 23 cases, eight had mitochondrial defects with GAPDH induction, four had increased mitochondrial expression, and 11 exhibited an overall suppression of metabolic activity (Fig. 7A,B). When we screened GRN and NUPR1 mRNA levels, only four cases had increased coexpression (Fig. 7B). Among these four cases, three were associated with the true mitochondrial defect (Fig. 7C). These results indicate that the mitochondrial defect accompanied by glycolytic activation is associated with coexpression of NUPR1 and GRN, also implying that NUPR1 may be involved in glycolytic gene expression.

Fig. 7.

Relationship between mitochondrial defect and NUPR1/GRN expression in hepatoma patient tissues. (A) Protein expression levels of three mitochondrial respiratory subunits and GAPDH of surrounding and tumor tissues from 23 hepatoma patients were examined by western blot analysis. (B) NUPR1 and GRN mRNA levels were examined by qRT-PCR using the same tissues. Mitochondrial activity changes of tumor tissues are indicated in the lower panel. (C) The rate of the tissues with coexpressed NUPR1/GRN. Abbreviation: Mito Df, mitochondrial defect.

Discussion

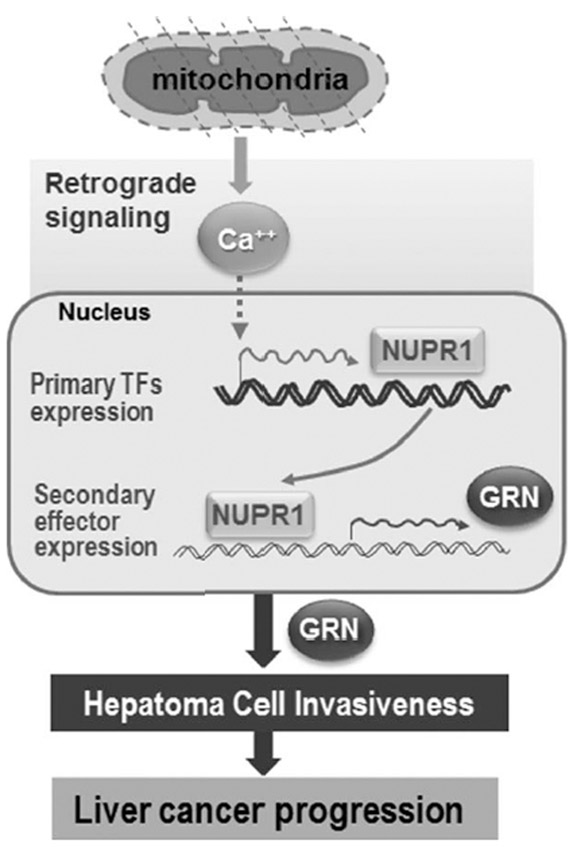

Many solid tumor cells experience intermittent hypoxia due to their rapid growth when forming a nodular mass in the early stages of cancer development, resulting in impaired mitochondrial respiration and a dependence on glycolytic energy production.38 Therefore, this bioenergetic feature has been accepted as an epiphenomenon of cancer. However, the causative roles of mitochondrial defects in tumor development have recently been reevaluated.2 For example, contributions of mtDNA mutations or direct functional respiratory defects to cancer promotion, metastasis, and chemoresistance have been reported,6,8,10,39 supporting the concept. Nevertheless, how mitochondrial impairment contributes to the development of cancerous features is unclear. By comparing the differentially expressed genes in three different mitochondrial defect cell models, we found 10 CMD genes up-regulated in response to mitochondrial damage. Interestingly, the enriched expression of the CMD signature was closely associated with shorter overall survival and recurrence-free survival in HCC patients. These results indicate that mitochondrial defects, subsequently induced gene products, and their cooperative actions contribute to HCC malignancy, potentially leading to the use of the “mitochondria signature” as a prognostic marker of HCC at diagnosis (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schematic model for the molecular involvement of NUPR1, a key CMD gene, in liver cancer progression. Abbreviation: TF, transcription factor.

The CMD signature included three TRs: NUPR1, NFIX, and NFE2L1. Surprisingly, all of these genes were critically involved in hepatoma invasiveness. These findings suggest that these TRs are the primary gene products activating the de novo transcription of certain effector genes for hepatoma invasiveness. To date, the regulatory functions of NFIX and NFE2L1 in cancer are not clearly understood, but NUPR1 has been implicated in the progression of various tumor malignancies, including breast, thyroid, brain, and pancreatic cancer,30 emphasizing its potential involvement in liver cancer progression.

NUPR1 was first identified to be up-regulated by cellular stress during acute pancreatitis in the rat, but its high expression in metastatic breast cancer cells and subsequent studies demonstrated its involvement in tumorigenic activity, making it a novel candidate for the metastasis-1 (com-1) gene.40 Structural similarities between NUPR1 and an HMG-I/Y member of nonhistone chromatin proteins and its nuclear localization using a bipartite nuclear targeting signal suggest a regulatory role in target gene transcription.41 Recently, the functional characterization of NUPR1 as a TR was reported in a study showing that NUPR1 binds the RELB promoter and activates its transcription, leading to the transactivation of IER3.42 Therefore, we hypothesize that NUPR1 plays a role as a key CMD-TR to control hepatoma cell invasiveness. We also showed that NUPR1 is regulated by intracellular Ca2+ levels, which may be associated with mitochondrial defects. This finding is further supported by previous reports of calcium-mediated NUPR1 regulation in renal mesangial hypertrophy,43 implying its general mechanistic involvement in diverse pathogenesis. This is the first report to show a direct link between the mitochondrial defect–Ca2+–NUPR1 axis and cancer development.

Although NUPR1 is known as a TR, how it controls transcriptional activity is unclear because its regulatory consensus sequence on DNA has not been firmly determined. HMG-I/Y is known to possess three AT-hook DNA-binding domains with a core motif (Pro-Arg-Lys-Arg-Pro) that prefers to bind to a consensus (TATT)n or (AATA)n repeat.44 However, NUPR1 does not have such a DNA-binding domain, despite the 35% identity in its primary protein structure, recognizing the narrow minor groove of A/T-rich target DNA rather than its nucleotide sequence.36 The GRN promoter does not have any (TATT)n or (AATA)n repeat but does have many dispersed single units with an A/T-rich stretch sequence. Using ChIP analysis, we confirmed that −2033 to −1547 of the GRN promoter region possesses core NUPR-binding capacity. However, the binding affinity of NUPR1 to the GRN promoter may be weak if working alone, and it may require other transcription factors, such as p300 and Pax2, to exert its regulatory activity on the transcription of target genes, as reported in glucagon gene regulation.45 These ideas also suggest that NUPR1 may regulate the expression of many target genes by binding to various transcription factors. Taken together, our results expand on our understanding of the molecular background of the action of NUPR1 in tumor progression through transcriptional regulation.

In an effort to identify the downstream effector genes induced by NUPR1 and those responsible for hepatoma invasion, four possible effectors were deduced by bioinformatic functional linking analysis of genes down-regulated by NUPR1 knockdown. GRN is supposed to be the most effective regulator of hepatoma progression according to increasing evidence.46 GRNs are a family of secretory glycopeptides possessing growth factor-like function. Cleavage of the signal peptide from progranulin, the precursor of GRN, produces mature GRN, which can be further cleaved into several active small peptides of 6 kDa. Both the peptides and intact GRN regulate many cellular functions, such as cell growth, development, wound healing, and tumorigenesis.33 Elevated GRN expression has often been reported in several tumor types, including ovarian, breast, prostate, and esophageal.47 Moreover, promotion of the growth and invasion of HCC by GRN overexpression has been demonstrated,46 implying its critical involvement in HCC progression. As expected, GRN knockdown effectively suppressed SNU hepatoma invasiveness, but its overexpression augmented the activity. We also showed that the GRN-mediated hepatoma invasion activity was controlled by Ca2+-mediated NUPR1 expression, presenting NUPR1 as a novel upstream regulator of GRN and emphasizing the importance of the Ca2+–NUPR1–GRN axis pathway in regulating hepatoma cell invasiveness. Concomittant up-regulation of NUPR1 and GRN was found in 75% of HCC tumor samples possessing the metabolic shift, mitochondrial defect, and glycolytic activation, indicating the potential involvement of NUPR1 in glycolytic activation. These results imply that NUPR1 plays a critical role as a metabolic switch in response to mitochondrial damage in addition to its regulatory function in hepatoma invasiveness and indicate the potential use of NUPR1 and GRN expression as diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets for HCC (Fig. 8).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (NRF-2012R1A5A2048183).

Abbreviations:

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- Ch-L

Chang clone with strong hepatic characteristics

- CMD

common mitochondrial defect

- ES

enrichment score

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GRN

granulin

- HA

hemagglutinin

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HMG

high mobility group

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- mtDNA

mitochondrial DNA

- NUPR1

nuclear protein 1

- OCR

oxygen consumption rate

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription PCR

- qRT-PCR

quantitative RT-PCR

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- TR

transcription regulator

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep.27976/suppinfo.

References

- 1.Wallace DC. Mitochondria and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:685–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuezva JM, Krajewska M, de Heredia ML, Krajewski S, Santamaria G, Kim H, et al. The bioenergetic signature of cancer: a marker of tumor progression. Cancer Res 2002;62:6674–6681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warburg O On the origin of cancer cells. Science 1956;123:309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatterjee A, Mambo E, Sidransky D. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in human cancer. Oncogene 2006;25:4663–4674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishikawa M, Nishiguchi S, Shiomi S, Tamori A, Koh N, Takeda T, et al. Somatic mutation of mitochondrial DNA in cancerous and non-cancerous liver tissue in individuals with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2001;61:1843–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petros JA, Baumann AK, Ruiz-Pesini E, Amin MB, Sun CQ, Hall J, et al. mtDNA mutations increase tumorigenicity in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:719–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sotgia F, Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Salem AF, Tsirigos A, Lamb R, et al. Mitochondria “fuel” breast cancer metabolism: fifteen markers of mitochondrial biogenesis label epithelial cancer cells, but are excluded from adjacent stromal cells. Cell Cycle 2012;11:4390–4401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He X, Zhou A, Lu H, Chen Y, Huang G, Yue X, et al. Suppression of mitochondrial complex I influences cell metastatic properties. PLoS One 2013;8:e61677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hung WY, Huang KH, Wu CW, Chi CW, Kao HL, Li AF, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes cell migration via reactive oxygen species-enhanced beta5-integrin expression in human gastric cancer SC-M1 cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1820:1102–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma J, Zhang Q, Chen S, Fang B, Yang Q, Chen C, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes breast cancer cell migration and invasion through HIF1alpha accumulation via increased production of reactive oxygen species. PLoS One 2013;8:e69485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Poyton RO, McEwen JE. Crosstalk between nuclear and mitochondrial genomes. Annu Rev Biochem 1996;65:563–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballinger SW Beyond retrograde and anterograde signalling: mitochondrial-nuclear interactions as a means for evolutionary adaptation and contemporary disease susceptibility. Biochem Soc Trans 2013;41:111–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones AW, Yao Z, Vicencio JM, Karkucinska-Wieckowska A, Szabadkai G. PGC-1 family coactivators and cell fate: roles in cancer, neurodegeneration, cardiovascular disease and retrograde mitochondria-nucleus signalling. Mitochondrion 2012;12:86–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finley LW, Haigis MC. The coordination of nuclear and mitochondrial communication during aging and calorie restriction. Ageing Res Rev 2009;8:173–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet 2005;39:359–407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biswas G, Adebanjo OA, Freedman BD, Anandatheerthavarada HK, Vijayasarathy C, Zaidi M, et al. Retrograde Ca2+ signaling in C2C12 skeletal myocytes in response to mitochondrial genetic and metabolic stress: a novel mode ofinter-organelle crosstalk. EMBO J 1999;18:522–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butow RA, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial signaling: the retrograde response. Mol Cell 2004;14:1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chae S, Ahn BY, Byun K, Cho YM, Yu MH, Lee B, et al. A systems approach for decoding mitochondrial retrograde signaling pathways. Sci Signal 2013;6:rs4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jazwinski SM, Kriete A. The yeast retrograde response as a model of intracellular signaling of mitochondrial dysfunction. Front Physiol 2012;3:139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amuthan G, Biswas G, Ananadatheerthavarada HK, Vijayasarathy C, Shephard HM, Avadhani NG. Mitochondrial stress-induced calcium signaling, phenotypic changes and invasive behavior in human lung carcinoma A549 cells. Oncogene 2002;21:7839–7849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulawiec M, Owens KM, Singh KK. Cancer cell mitochondria confer apoptosis resistance and promote metastasis. Cancer Biol Ther 2009;8:1378–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulawiec M, Safina A, Desouki MM, Still I, Matsui S, Bakin A, et al. Tumorigenic transformation of human breast epithelial cells induced by mitochondrial DNA depletion. Cancer Biol Ther 2008;7:1732–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JH, Kim EL, Lee YK, Park CB, Kim BW, Wang HJ, et al. Decreased lactate dehydrogenase B expression enhances claudin 1–mediated hepatoma cell invasiveness via mitochondrial defects. Exp Cell Res 2011;317:1108–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee YK, Youn HG, Wang HJ, Yoon G. Decreased mitochondrial OGG1 expression is linked to mitochondrial defects and delayed hepatoma cell growth. Mol Cells 2013;35:489–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Byun HO, Kim HY, Lim JJ, Seo YH, Yoon G. Mitochondrial dysfunction by complex II inhibition delays overall cell cycle progression via reactive oxygen species production. J Cell Biochem 2008;104:1747–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Delsite R, Kachhap S, Anbazhagan R, Gabrielson E, Singh KK. Nuclear genes involved in mitochondria-to-nucleus communication in breast cancer cells. Mol Cancer 2002;1:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dennis G Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, et al. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JH, Kim HY, Lee YK, Yoon YS, Xu WG, Yoon JK, et al. Involvement of mitophagy in oncogenic K-Ras-induced transformation: overcoming a cellular energy deficit from glucose deficiency. Autophagy 2011;7:1187–1198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Imamura H, Matsuyama Y, Tanaka E, Ohkubo T, Hasegawa K, Miyagawa S, et al. Risk factors contributing to early and late phase intrahepatic recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. J Hepatol 2003;38:200–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chowdhury UR, Samant RS, Fodstad O, Shevde LA. Emerging role of nuclear protein 1 (NUPR1) in cancer biology. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2009;28:225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nickless A, Jackson E, Marasa J, Nugent P, Mercer RW, Piwnica-Worms D, et al. Intracellular calcium regulates nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Nat Med 2014;20:961–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warde-Farley D, Donaldson SL, Comes O, Zuberi K, Badrawi R, Chao P, et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res 2010;38:W214–W220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demorrow S Progranulin: a novel regulator of gastrointestinal cancer progression. Transl Gastrointest Cancer 2013;2:145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Monami G, Emiliozzi V, Bitto A, Lovat F, Xu SQ, Goldoni S, et al. Proepithelin regulates prostate cancer cell biology by promoting cell growth, migration, and anchorage-independent growth. Am J Pathol 2009;174:1037–1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang M, Li G, Yin J, Lin T, Zhang J. Progranulin overexpression predicts overall survival in patients with glioblastoma. Med Oncol 2012; 29:2423–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Encinar JA, Mallo GV, Mizyrycki C, Giono L, Gonzalez-Ros JM, Rico M, et al. Human p8 is a HMG-I/Y-like protein with DNA binding activity enhanced by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem 2001;276: 2742–2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tokunaga K, Nakamura Y, Sakata K, Fujimori K, Ohkubo M, Sawada K, et al. Enhanced expression of a glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene in human lung cancers. Cancer Res 1987;47:5616–5619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer 2004;4:891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guaragnella N, Giannattasio S, Moro L. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer chemoresistance. Biochem Pharmacol 2014;92:62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ree AH, Tvermyr M, Engebraaten O, Rooman M, Rosok O, Hovig E, et al. Expression of a novel factor in human breast cancer cells with metastatic potential. Cancer Res 1999;59:4675–4680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valacco MP, Varone C, Malicet C, Canepa E, Iovanna JL, Moreno S. Cell growth-dependent subcellular localization of p8. J Cell Biochem 2006;97:1066–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamidi T, Algul H, Cano CE, Sandi MJ, Molejon MI, Riemann M, et al. Nuclear protein 1 promotes pancreatic cancer development and protects cells from stress by inhibiting apoptosis. J Clin Invest 2012; 122:2092–2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goruppi S, Kyriakis JM. The pro-hypertrophic basic helix-loop-helix protein p8 is degraded by the ubiquitin/proteasome system in a protein kinase B/Akt- and glycogen synthase kinase-3-dependent manner, whereas endothelin induction of p8 mRNA and renal mesangial cell hypertrophy require NFAT4. J Biol Chem 2004;279:20950–20958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reeves R Structure and function of the HMGI(Y) family of architectural transcription factors. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108(Suppl. 5):803–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoffmeister A, Ropolo A, Vasseur S, Mallo GV, Bodeker H, Ritz-Laser B, et al. The HMG-I/Y-related protein p8 binds to p300 and Pax2 trans-activation domain–interacting protein to regulate the transactivation activity of the Pax2A and Pax2B transcription factors on the glucagon gene promoter. J Biol Chem 2002;277:22314–22319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cheung ST, Wong SY, Leung KL, Chen X, So S, Ng IO, et al. Granulin-epithelin precursor overexpression promotes growth and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:7629–7636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bateman A, Bennett HP. The granulin gene family: from cancer to dementia. Bioessays 2009;31:1245–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.