Abstract

Purpose:

Accurate description of temporomandibular size and shape (morphometry) is critical for clinical diagnosis and surgical planning, design and development of regenerative scaffolds and prosthetic devices, and to model the temporomandibular loading environment. The study objective was to determine the three-dimensional morphometry of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) condyle and articular disc by CBCT, MRI and physical measurements on the same joints using a repeated measures design, to determine the effect of measurement technique on temporomandibular size and shape.

Materials and Methods:

Human cadaveric heads underwent a multi-step protocol, acquiring physiologically meaningful measurements of the condyle and disc. Heads first underwent CBCT scanning and solid models were automatically generated. Superficial soft tissues were dissected and intact TMJs were excised and underwent MRI scanning, and solid models were generated following manual segmentation. Following MRI scanning, intact joints were dissected and physical measurements of the condyle and articular disc were made. CBCT-based model measurements, MRI-based model measurements and physical measurements were standardized, and a repeated measures study design determined the effect of measurement technique on morphometric parameters.

Results:

Multivariate general linear mixed effects models showed significant effects for measurement technique for condylar morphometric outcomes (p<0.001) and articular disc morphometric outcomes (p<0.001). Physical measurements following dissection were larger than both CBCT-based and MRI-based measurements. Differences in imaging-based morphometric parameters followed a complex relationship between imaging modality resolution and contrast between tissue types.

Conclusion:

Physical measurements following dissection are still considered the gold standard, however due to their inaccessibility in vivo, understanding how imaging technique impacts temporomandibular size and shape is critical towards the development of high-fidelity solid models, to be utilized in the design and development of regenerative scaffolds, surgical planning, prosthetic devices and for anatomical investigations.

Keywords: TMJ morphometry, Mandibular condyle, Articular disc, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT)

INTRODUCTION

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is the point of articulation between the temporal bone and mandibular condyle, with a cartilaginous articular disc separating the boney components. Approximately 2–4% of the U.S. population are estimated to seek treatment for temporomandibular symptoms [1]. Accurate description of temporomandibular morphometry is critical for clinical diagnosis and surgical planning, design and development of regenerative scaffolds and prosthetic devices [2–6], and to accurately model temporomandibular stresses and strains, contact mechanics, and nutrient environment [7–9]. However, discrepancies in reported temporomandibular morphometry between measurement techniques results in controversy surrounding the real size and shape of temporomandibular components. There has been no repeated measures comparison of temporomandibular components, assessing measurement technique effects on morphometric outcomes.

Some efforts towards describing temporomandibular morphometry have been reported (Table 1); however, mandibular condyle and articular disc size and shape remains controversial, given large discrepancies in reported morphometric outcomes between cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) [10–13], magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [14], and physical measurements [15–18]. Discrepancies between measurement techniques, in some cases more than 100%, is associated with each technique’s unique limitations [19–22]. Specifically, CBCT is incapable of natively imaging soft tissue structures in vivo, while clinical MRIs are limited by resolution, and local contrast between soft-tissue types. Physical measurements on cadaveric tissues, considered the gold standard, are limited by their inaccessibility in vivo, while physical measurements on histological slides includes shrinkage during fixation [23] and are limited to measurements in the slicing plane.

Table 1.

Morphometric parameters from CBCT-based model measurements, MRI-based model measurements, physical measurements following dissection, compared to the available morphometric literature for the condyle and articular disc.

| CBCT-Based Measurements | Hi-resolution Preclinical MRI-based Measurements | Physical Measurements | CBCT-based Literature | Clinical MRI-based Literature | Physical Measurement Literature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condylar Major Axis Length (mm) | 20.6 ± 1.8 | 19.8 ± 1.8 | 20.2 ± 1.5 | 19.0 ± 2.5 [10] 22.1 ± 2.7 [11] 20.3 ± 2.2 [12] | 6.4 ± 1.1 [13] | |

| Condylar Minor Axis Length (mm) | 8.3 ± 1.4 | 7.9 ± 1.7 | 9.6 ± 1.1 | |||

| Condylar Height (mm) | 6.8 ± 1.1 | 6.0 ± 1.2 | 8.6 ± 0.8 | |||

| Condylar Lingual Length (mm) | 13.7 ± 1.9 | 13.2 ± 1.5 | 14.5 ± 1.6 | |||

| Condylar Buccal Length (mm) | 8.3 ± 1.9 | 7.6 ± 1.4 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | |||

| Disc Major Axis Length (mm) | 22.2 ± 2.1 | 22.1 ± 1.7 | 20.4 ± 0.5 [15] | |||

| Disc Minor Axis Length (mm) | 12.2 ± 1.1 | 14.0 ± 1.3 | 16.7 ± 1.7 [15] | |||

| Anterior Band Thickness (mm) | 3.1 ± 0.6 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 1.2 ± 0.2 [14] | 2.1 ± 0.5 [16] 1.9 ± 0.3 [18] | ||

| Medial Disc Thickness (mm) | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.4 [16] 0.6 ± 0.2 [18] | |||

| Intermediate Zone Thickness (mm) | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 0.1 [14] | ~ 1–2 [17] 1.1 ± 0.4 [16] 0.6 ± 0.3 [18] | ||

| Lateral Disc Thickness (mm) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 [16] 0.5 ± 0.1 [18] | |||

| Posterior Band Thickness (mm) | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.3 [14] | ~ 3 mm [17] 2.8 ± 0.6 [16] 2.0 ± 0.6 [18] 2.1 ± 0.7 [15] |

To understand how measurement technique affects temporomandibular morphometry, physiologically meaningful landmark based measurements of the mandibular condyle and articular disc are required. The mandibular condyle, when viewed from above, has an elliptical cross section, with its major axis in the mediolateral direction approximately at right angles to the plane of the ramus [24]. The lateral (buccal) and medial (lingual) poles of the mandibular condyle in turn are defined by bony tubercles for the attachment of the articular disc [24]. Also, defining the shape of the mandibular condyle is the pterygoid fovea, which is a small triangular depression medial to the anterior ridge formed by the ramus into which fibers of the lateral pterygoid muscle are inserted [24, 25]. The TMJ articular disc is described as biconcave [26], and has been divided into an anterior band, intermediate zone, and posterior band [27]. The disc is thicker medially than laterally, while anteroposteriorly the disc is thinnest in the intermediate zone and thickest in the posterior band [16, 17, 28, 29]. In addition to their anatomic description, analysis of these articular disc regions in humans is supported by the human biomechanics literature [30–34].

Given discrepancies in reported temporomandibular morphometric outcomes between measurement techniques, the study objective was to determine the three-dimensional morphometry of the TMJ condyle and articular disc by CBCT, MRI and physical measurements on the same joints using a repeated measures design to determine the effect of measurement technique on temporomandibular size and shape. It was hypothesized that physical measurements would be largest, with CBCT and MRI measurements smaller, associated with pixel resolution and contrast between tissue types. Understanding measurement technique effects on temporomandibular morphometric outcomes is critical to interpreting discrepancies in temporomandibular size and shape reported in the literature. Furthermore, this study provides critical quantification of mandibular condyle and articular disc size and shape, towards the development of high-fidelity solid models for biomechanical analysis, design and development of regenerative scaffolds and prosthetic devices, and for anatomical investigations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human heads underwent a multi-step protocol, acquiring three-dimensional physiologically meaningful measurements of the mandibular condyle and articular disc. Following a repeated measures design, morphometric measurements were made for each joint, on CBCT-based models, MRI-based models, and physical measurements following dissection. Human heads first underwent CBCT scanning to acquire a solid model of the bones of the skull. Following CBCT scanning, superficial soft tissues were dissected and intact TMJs were extracted. Intact joints then underwent MRI scanning to acquire solid models of the mandibular condyle and disc. Following MRI scanning, intact joints were dissected and physical measurements of the mandibular condyle and articular disc were made. The effect of measurement technique on morphometric parameters was determined.

Specimen Selection and CBCT Scanning

Eleven fresh male human cadaveric heads (74.5 ± 9.1 years) with no known history of temporomandibular disorders were included in this study, with appropriate institutional approval from the Medical University of South Carolina. Donor heads were stored at −20°C before use, and thawed for 24 hours before CBCT scanning. Each mandible was fixed to the maxilla with a custom plastic bracket, and the mouth in the closed position. Donor heads were scanned using a clinical CBCT scanner (Planmeca3DMax, Planmeca USA, Roselle, IL) with voxel dimensions of 0.5×0.5×0.5 mm3.

Temporomandibular Joint Extraction and MRI Scanning

After CBCT scanning, TMJs were excised intact bilaterally, including portions of the mandible and temporal bone [35]. TMJs were dissected by surgical saw, with an approximately 2.5 cm long cut approximately 1 cm above the zygomatic arch over the TMJ. The second cut was perpendicular to the first, posterior to the TMJ capsule, just anterior to the external auditory canal, running from the first cut to the base of the skull. The third cut was approximately one-inch anterior to the first, to which it was parallel, running from the first cut to the skull base. Finally, the mandible was transected approximately one-half inch below the inferior edge of the capsule. The bony attachment on the skull base along the medial aspect of the TMJ was detached by chisel. Intact TMJs were wrapped in cellophane and PBS soaked gauze, placed in specimen bags and frozen at −20°C until use.

Prior to MRI scanning, intact TMJs were thawed and soaked in a gadolinium-based contrast agent bath (2.5 mM Bracco MultiHance, Bracco Diagnostics, Inc., Milan, Italy) for 48 hours. Specimens were sealed in 50mm polystyrene specimen containers (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA), with contrast agent, for MRI scanning. Specimens were scanned with a 7T MRI scanner (BioSpec 70/30 USR, Bruker Corp., Billerica, MA) using a proton-density weighted sequence; FoV: 60mm × 45mm, matrix size: 256 × 192, in-plane resolution: 0.234 mm × 0.234 mm, slice thickness: 0.5 mm, no slice gap, total slice count: 60 slices, TR: 2400 ms, TE: 12 ms, scan time: 32 minutes. A high-resolution preclinical MRI scanner was used to provide the best-case scenario for determining temporomandibular morphometry. Joint scans were assessed for signs of disc displacement and joint degeneration.

Physical Dissection and Measurements

TMJs were further dissected with a cut down through the zygomatic notch into the superior joint space, preserving the lateral wall of the lateral capsule-ligament complex and articular disc. The lateral capsule-ligament complex was dissected from the articular disc to isolate the disc-condyle unit intact, and soft tissues were dissected from the pterygoid fovea. Disc major length and disc minor length measurements were made, with the disc on the condyle, using a digital micrometer. The disc was dissected off the condylar head, and all disc thickness measurements and condylar measurements were made.

CBCT and MRI Model Development and Morphometric Analysis

Models from the CBCT and MRI scans were reconstructed (Figure 1), and mandibular condyle and articular disc morphometry was determined. CBCT-based models of the mandible were generated using thresholding, with model defects manually corrected (Amira 6.4, FEI Co., Hillsboro, OR). MRI-based models of the mandible and articular disc were generated using manual segmentation (Amira 6.4). Given the high-resolution pre-clinical MRI scanning, manual segmentation of the mandibular condyle was performed by tracing the thin cortical bone shell in each image slice. For the articular disc, the disc superior and inferior borders were established by the corresponding joint space, bounded by either the glenoid fossa of the temporal bone or the mandibular condyle. The anterior and posterior boundaries of the articular disc were approximated by considering the observed fiber directions in the articular disc anterior and posterior bands, and generalized description of thickening in these regions. Manual articular disc segmentation is anticipated to be similar in method to that utilized in previous reports on MR articular disc thickness measurements [14], and was confirmed by a trained oral and maxillofacial surgeon (MKL).

Figure 1.

CBCT scans of donor cadaveric heads used for condylar reconstructions in the saggital and coronal planes (A). MRI scans of excised temporomandibular joints used for condylar and articular disc reconstructions in the saggital and coronal planes (B). Unsmoothed reconstruction of the mandible from CBCT scans, used to determine condylar morphometry in the saggital and coronal planes (C). Unsmoothed reconstruction of the mandible and articular disc from MRI scans, used to determine condylar and disc morphometry in the saggital and coronal planes (D).

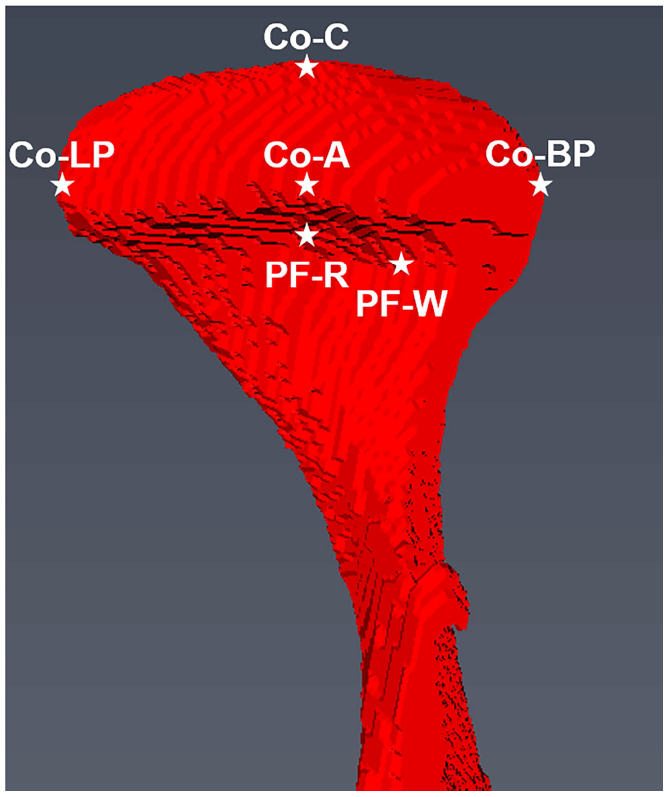

Temporomandibular morphometric parameters were standardized between CBCT-based models, MRI-based models and physical measurements following dissection (Figure 2). Condylar morphometric outcomes were: major axis length, defined as the distance from the condylar lingual pole (Co-LP) to the buccal pole (Co-BP); minor axis length, defined as the maximum length orthogonal to the major axis from the anterior edge of the condyle (Co-A) to the posterior edge of the condyle (Co-P); condylar height, defined as the distance from the roof of the pterygoid fovea (PF-R) to the crown of the condyle (Co-C); lingual length, defined as the distance from the wall of the pterygoid fovea (PF-W) to the lingual pole of the condyle (Co-LP); buccal length, defined as the distance from the wall of the pterygoid fovea (PF-W) to the buccal pole of the condyle (Co-BP). Articular disc morphometric outcomes were: major axis length, defined as the distance from the lingual disc pole (D-LP) to the buccal disc pole (D-BP); minor axis length, defined as the maximum length orthogonal to the disc major axis from the anterior edge of the disc (D-A) to the posterior edge of the disc (D-P); anterior band thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface of the disc at the anterior edge of the disc mid-body (D-A); posterior band thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface of the disc at the posterior edge of the disc mid-body (D-P); medial aspect thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface of the disc at the medial edge of the lingual disc pole (D-LP); lateral aspect thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface of the disc at the lateral edge of the buccal disc pole (D-BP); intermediate zone thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface of the disc at the disc center (D-IZ). Mandibular condyle and articular disc morphometric measurements were all made on unsmoothed 3D models, to limit the effects of shrinkage relative to their natural physical dimensions during smoothing processes.

Figure 2.

Illustrations of the condylar morphometric parameters in the axial plane (A) and coronal plane (B), with illustrations of the disc morphometric parameters in the axial plane (C) and orthogonal view (D). Temporomandibular joint morphometric parameters were standardized between the CBCT-based model measurements, MRI-based model measurements and physical measurements. Condylar morphometric outcomes were: major axis length, defined as the distance from Co-LP to Co-BP; minor axis length, defined as the distance from Co-A to Co-P; condylar height, defined as the distance from PF-R to Co-C; lingual length, defined as the distance from PF-W to Co-LP; buccal length, defined as the distance from PF-W to Co-BP. Articular disc morphometric outcomes were: major axis length, defined as the distance from D-LP to D-BP; minor axis length, defined as the distance from D-A to D-P; anterior band thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface located at D-A (shown only); posterior band thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface located at D-P; medial aspect thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface located at D-LP; lateral aspect thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface located at D-BP; intermediate zone thickness, defined as the distance from the superior surface of the disc to the inferior surface of the disc at the disc center (D-IZ). Mandibular condyle and articular disc morphometric measurements were all made on unsmoothed 3D models, to limit the effects of shrinkage relative to their natural physical dimensions during smoothing processes.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical modeling assessed differences in mandibular condyle and articular disc morphometry to evaluate CBCT-based, MRI-based and physical measurements, using multivariate general linear mixed effects models. Differences in morphometric outcomes for the mandibular condyle (condyle major axis length, condyle minor axis length, lingual length, buccal length, height) were determined for CBCT-based model measurements, MRI-based model measurements, and physical measurements. Differences in morphometric outcomes for the articular disc (disc major axis length, disc minor axis length, anterior band thickness, posterior band thickness, medial aspect thickness, lateral aspect thickness, intermediate zone thickness) were determined for MRI-based model measurements and physical measurements. Multivariate general linear mixed effects models included donor and joint side as covariates to impose repeated measures constraints. Where significant differences in the multivariate general linear mixed effects model were determined, pairwise contrasts were determined by least significant difference post-hoc test. Analyses were performed in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 23.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). All significant differences were reported at α<0.05, with descriptive statistics reported as mean ± standard deviation.

RESULTS

Condylar Morphometry

Condylar morphometry was successfully determined from physical measurements, MRI-based models and CBCT-based models for the human temporomandibular mandibular condyle and articular disc (Figure 3). The multivariate general linear mixed effects model showed significant effects for measurement technique for condylar morphometric outcomes (p<0.001).

Figure 3.

Significant differences in condylar morphometry between measurement techniques were determined (p<001), with significant differences for condylary minor axis length (p=0.002), condylar height (p<0.001), condylar buccal length (p<0.001), and condylar lingual length (p<0.001). Individual pairwise contrasts in condylar morphometric outcomes between measurement techniques were determined: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

There were significant differences between measurement techniques for condylar minor axis (p=0.002), with significant pairwise contrasts between CBCT-based model measurements and physical measurements (p=0.010), and between MRI-based model measurements and physical measurements (p=0.001). Condylar minor axis measured 8.3 ± 1.4 mm in the CBCT-based model, 7.9 ± 1.7 mm in the MRI-based model, and physical measurements were 9.6 ± 1.1 mm. There were significant differences between measurement techniques for condylar height (p<0.001), with significant pairwise contrasts between CBCT-based model measurements and physical measurements (p<0.001), between MRI-based model measurements and physical measurements (p<0.001), and between MRI-based model measurements and CBCT-based model measurements (p=0.037). Condylar height measured 6.8 ± 1.1 mm in the CBCT-based model, 6.0 ± 1.2 mm in the MRI-based model, and physical measurements were 8.6 ± 0.8 mm. There were significant differences between measurement techniques for condylar lingual length (p=0.040), with a significant pairwise contrast between MRI-based model measurements and physical measurements (p=0.012). Condylar lingual length measured 13.7 ± 1.9 mm in the CBCT-based model, 13.2 ± 1.5 mm in the MRI-based model, and physical measurements were 14.5 ± 1.6 mm. There were significant differences between measurement techniques for condylar buccal length (p<0.001), with significant pairwise contrasts between CBCT-based model measurements and physical measurements (p<0.001), and MRI-based model measurements and physical measurements (p<0.001). Condylar buccal length measured 8.3 ± 1.9 mm in the CBCT-based model, 7.6 ± 1.4 mm in the MRI-based model, and physical measurements were 5.4 ± 0.9 mm. There were no significant differences between measurement techniques for condylar major axis (p=0.483). Condylar major axis measured 20.6 ± 1.8 mm in the CBCT-based model, 19.8 ± 1.8 mm in the MRI-based model, and physical measurements were 20.2 ± 1.5 mm.

Articular Disc Morphometry

Articular disc morphometry was successfully determined from physical measurements and MRI-based models (Figure 4). The multivariate general linear mixed effects model showed significant effects for measurement technique for articular disc morphometric outcomes (p<0.001).

Figure 4.

Significant differences in articular disc morphometry between measurement techniques were determined (p<001). Individual pairwise contrasts in articular disc morphometric outcomes between measurement techniques were determined: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

There was a significant difference between measurement techniques for disc minor axis length (p<0.001), with disc minor axis length measured 12.2 ± 1.1 mm in the MRI-based model and physical measurements were 14.0 ± 1.3 mm. There was a significant difference between measurement techniques for disc medial aspect thickness (p<0.001), with disc medial aspect thickness measured 1.3 ± 0.3 mm in the MRI-based model and physical measurements were 2.4 ± 0.6 mm. There was a significant difference between measurement techniques for disc lateral aspect thickness (p<0.001), with disc lateral aspect thickness measured 1.2 ± 0.4 mm in the MRI-based model, and physical measurements were 1.8 ± 0.4 mm. There was a significant difference between measurement techniques for disc intermediate zone thickness (p=0.029), with disc intermediate zone thickness measured 1.0 ± 0.3 mm in the MRI-based model and physical measurements were 1.4 ± 0.7 mm. There was no significant difference between measurement techniques for disc major axis length (p=0.909), with disc major axis length measured 22.2 ± 2.1 mm in the MRI-based model and physical measurements were 22.1 00B1 1.7 mm. There was no significant difference between measurement techniques for disc anterior band thickness (p=0.178), with disc anterior band thickness measured 3.1±0.6mm in the MRI-based model, and physical measurements were 2.7 ± 0.6 mm. There was no significant difference between measurement techniques for disc posterior band thickness (p=0.731), with disc posterior band thickness measured 3.7 ± 0.3 mm in the MRI-based model, and physical measurements were 3.7 ± 0.6 mm.

DISCUSSION

Given discrepancies in reported temporomandibular morphometric outcomes between measurement techniques, the study objective was to determine measurement technique effects on the three-dimensional morphometry of the human mandibular condyle and articular disc determined by CBCT, MRI and physical measurements. Using a repeated measures design, significant differences in condylar and disc morphometric outcomes were determined between measurement techniques. Comparing measurement techniques, physical measurements were generally larger than CBCT-based measurements and MRI-based measurements, with little difference between CBCT-based and MRI-based measurements. Differences in morphometric parameters utilizing imaging based measurements followed a complex relationship between imaging modality resolution and contrast between tissue types. Understanding imaging technique effects on the observed size and shape of temporomandibular components is critical towards accurate clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, this study provides critical quantification on the size and shape of the mandibular condyle and articular disc, towards the development of high-fidelity biomechanics models, design of regenerative scaffolds and surgical planning, and for anatomical investigations.

Differences in condylar morphometry were determined between CBCT-based model measurements, MRI-based model measurements and physical measurements following dissection. Comparing measurement techniques for condylar morphometry, physical measurements were significantly larger than MRI-based and CBCT-based measurements for condylar minor axis length, condylar height and condylar lingual length. There were no differences in condylar morphometry between measurement techniques for condylar major axis length, likely associated with good local contrast and limited shrinkage due to pixilation. Physical measurements for condylar buccal length were shorter than CBCT-based and MRI-based model measurements due to the 3D measurement, specifically interference with the lateral pterygoid fovea wall using the digital micrometer.

Differences in articular disc morphometry were determined between MRI-based model measurements and physical measurements following dissection. Comparing measurement techniques for articular disc morphometry, physical measurements were significantly larger than MRI-model based measurements for medial disc thickness, lateral disc thickness, intermediate zone thickness and disc minor length, where the small size and limited resolution and contrast prevented accurate measurements. There were no differences between anterior band thickness and posterior band thickness, where shrinkage was minimized by high local contrast between tissue types in these highly organized, relatively large regions. There was no difference between measurement techniques for disc major axis length, where good local contrast was able to establish disc boundaries in the MRI-based model measurements and relatively large size.

TMJ morphometry was determined using a set of physiologically meaningful landmarks for the mandibular condyle and articular disc, defining their three-dimensional size and shape. Study results provide a comprehensive determination of condyle and articular disc morphometry, critical to the design of regenerative scaffolds, prosthetic devices, and for anatomical studies. In general, study results agreed well with the literature on the temporomandibular joint morphometry for the physical measurements and CBCT-based measurements (Table 1). Previously reported temporomandibular morphometry using clinical MRI scanners differed significantly, given clinical MRI scanner’s decreased resolution and contrast, and large step size between scans. Differences between condylar physical measurements and CBCT-based model measurements and MRI-based model measurements for condylar major axis length and condylar lingual length were within 2%, while condylar minor axis and condylar height were within 20%. Differences between articular disc physical measurements and MRI-based model measurements for disc major axis length, disc minor axis length, anterior band thickness and posterior band thickness within 10%, while intermediate zone thickness and lateral band thickness and medial disc thickness were within 50%. When considering differences between imaging-based methods and physical measurements, pixel size and local contrast are important factors to consider. In the present study, the CBCT scanner had a voxel size of 0.5×0.5×0.5 mm3, and the pre-clinical scanner on excised TMJs resulted in a voxel size of 0.234×0.234×0.5 mm3. This is in contrast to typical clinical CT and MRI scans of the TMJ which have reduced in-plane resolution with slice thicknesses as large as 2–3 mm [14, 22, 36]. In the present study, all measurements were made based on the unsmoothed models (Figure 2), as smoothing processes result in an overall reduction in size. Furthermore, the unsmoothed models of the articular disc presented in this study are the most robust 3D representation of the actual 3D size and shape of the articular disc.

Limitations for the current study include condylar and articular disc morphometry only included male subjects. However, given the study objective was to determine measurement technique effects on morphometric outcomes, use of only male subjects is acceptable. Future studies should also include morphometric analysis of female TMJs to quantify the observed morphologic differences between male and female condyles [37]. It should be considered that morphometric parameters reported by this study are from a morphologically normal, geriatric population. Changes in mandibular condyle and articular disc size and shape as the result of ageing [38] and edentulism are anticipated, but unable to be estimated by this study. The effect of multiple freeze-thaw cycles on the morphometry of the mandibular condyle, and in particular the articular disc, is of potential concern. It is anticipated however, the effects of the freeze-thaw cycles between the CBCT and MRI scans, and between the MRI scan and physical measurements, on articular disc morphometry are minimal as a result of the synovial joint being intact, the lengthy rehydration period between CBCT and MRI scanning, and the reported small effect of freezing on tissue hydration on the TMJ articular disc [39, 40]. There is no expected change as a result of the two freeze thaw cycles on the morphometric outcomes for the mandibular condyle, which has a low water content. A potentially significant limitation with the study is the use of a single-observer model for the manual segmentation of the MR images for model generation, and all morphometric analysis. In our preliminary workups on one specimen, inter-observer variability between 5 observers was low for the articular disc with physical measurements having an average standard error of the mean of 0.24 mm, and MRI model-based measurements having an average standard error of the mean of 0.34 mm or approximately one pixel. In other human TMJ morphometric studies using imaging based techniques, inter-observer variability is reported to be generally good [13, 41]. Furthermore, use of a repeated measures study design in a single-observer model should provide acceptable confidence in the reported differences between measurement technique [42].

In conclusion, this study determined the effect of measurement technique on temporomandibular morphometric parameters, investigating CBCT-based model measurement, MRI-based model measurements, and physical measurements following dissection. Morphometric differences between physical measurements, CBCT-based model measurements and MRI-based model measurements were generally good; however, even for the preclinical MRI scanner, measurement discrepancies could still be as much as 50%. The use of clinical MRI scanners is anticipated to deviate greatly from these values where resolution and contrast are greatly limited. Comparing measurement techniques, physical measurements were generally larger than both CBCT-based measurements and MRI-based measurements, with little difference between CBCT-based and MRI-based model measurements. Understanding the effects of imaging technique on the observed size and shape of temporomandibular components is critical towards accurate clinical diagnosis. Furthermore, this study provides critical quantification on the size and shape of the mandibular condyle and articular disc, towards the development of high-fidelity solid models to be utilized in biomechanical analysis, design and development of regenerative scaffolds, surgical planning, prosthetic devices and for anatomical investigations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported by NIH grants DE018741 and DE021134, and a NIH T32 post-doctoral fellowship DE017551 and a NIH F32 post-doctoral fellowship DE027864 to MCC. None of the authors have a conflict of interest that might be construed as affecting the conduct or reporting of the work presented. The authors would also like to kindly acknowledge the work of Collin Czajka and Ethan Lopez for the manual segmentation of the high-resolution MR scans and temporomandibular joint model development, Dr. Thierry Bacro for facilitating all human cadaveric tissue handling, and Dr. Truman Brown for providing access to the high-resolution preclinical MR scanner.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haskin CL, Milam SB, Cameron IL: Pathogenesis of degenerative joint disease in the human temporomandibular joint. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 6:248, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zizelmann C, Bucher P, Rohner D, Gellrich NC, Kokemueller H, Hammer B: Virtual restoration of anatomic jaw relationship to obtain a precise 3D model for total joint prosthesis construction for treatment of TMJ ankylosis with open bite. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 39:1012, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsumoto K, Ishiduka T, Yamada H, Yonehara Y, Arai Y, Honda K: Clinical use of three-dimensional models of the temporomandibular joint established by rapid prototyping based on cone-beam computed tomography imaging data. Oral Radiology 30:98, 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legemate K, Tarafder S, Jun Y, Lee CH: Engineering Human TMJ Discs with Protein- Releasing 3D-Printed Scaffolds. J Dent Res 95:800, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown BN, Chung WL, Almarza AJ, Pavlick MD, Reppas SN, Ochs MW, Russell AJ, Badylak SF: Inductive, scaffold-based, regenerative medicine approach to reconstruction of the temporomandibular joint disk. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 70:2656, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xu X, Luo D, Guo C, Rong Q: A custom-made temporomandibular joint prosthesis for fabrication by selective laser melting: Finite element analysis. Med Eng Phys 46:1, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Y, Cisewski SE, Wei F, She X, Gonzales TS, Iwasaki LR, Nickel JC, Yao H: Fluid pressurization and tractional forces during TMJ disc loading: A biphasic finite element analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res 20 Suppl 1:151, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka E, Rodrigo DP, Tanaka M, Kawaguchi A, Shibazaki T, Tanne K: Stress analysis in the TMJ during jaw opening by use of a three-dimensional finite element model based on magnetic resonance images. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 30:421, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hattori-Hara E, Mitsui SN, Mori H, Arafurue K, Kawaoka T, Ueda K, Yasue A, Kuroda S, Koolstra JH, Tanaka E: The influence of unilateral disc displacement on stress in the contralateral joint with a normally positioned disc in a human temporomandibular joint: an analytic approach using the finite element method. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 42:2018, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang YL, Song JL, Xu XC, Zheng LL, Wang QY, Fan YB, Liu Z: Morphologic Analysis of the Temporomandibular Joint Between Patients With Facial Asymmetry and Asymptomatic Subjects by 2D and 3D Evaluation: A Preliminary Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 95:e3052, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.You KH, Lee KJ, Lee SH, Baik HS: Three-dimensional computed tomography analysis of mandibular morphology in patients with facial asymmetry and mandibular prognathism. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 138:540 e1, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue K, Nakano H, Sumida T, Yamada T, Otawa N, Fukuda N, Nakajima Y, Kumamaru W, Mishima K, Kouchi M, Takahashi I, Mori Y: A novel measurement method for the morphology of the mandibular ramus using homologous modelling. Dentomaxillofac Radiol 44:20150062, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pullinger AG, Seligman DA, John MT, Harkins S: Multifactorial modeling of temporomandibular anatomic and orthopedic relationships in normal versus undifferentiated disk displacement joints. J Prosthet Dent 87:289, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M, Cao H, Ge Y, Widmalm SE: Magnetic resonance imaging on TMJ disc thickness in TMD patients: a pilot study. J Prosthet Dent 102:89, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paglio AE, Bradley AP, Tubbs RS, Loukas M, Kozlowski PB, Dilandro AC, Sakamoto Y, Iwanaga J, Schmidt C, D’Antoni AV: Morphometric analysis of temporomandibular joint elements. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 46:63, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansson T, Oberg T, Carlsson GE, Kopp S: Thickness of the soft tissue layers and the articular disk in the temporomandibular joint. Acta Odontol Scand 35:77, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choukas NC, Sicher H: The structure of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 13:1203, 1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang MQ, He JJ, Li G, Widmalm SE: The effect of physiological nonbalanced occlusion on the thickness of the temporomandibular joint disc: a pilot autopsy study. J Prosthet Dent 99:148, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Westesson PL, Katzberg RW, Tallents RH, Sanchez-Woodworth RE, Svensson SA: CT and MR of the temporomandibular joint: comparison with autopsy specimens. AJR Am J Roentgenol 148:1165, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Westesson PL, Katzberg RW, Tallents RH, Sanchez-Woodworth RE, Svensson SA, Espeland MA: Temporomandibular joint: comparison of MR images with cryosectional anatomy. Radiology 164:59, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lewis EL, Dolwick MF, Abramowicz S, Reeder SL: Contemporary imaging of the temporomandibular joint. Dent Clin North Am 52:875, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bag AK, Gaddikeri S, Singhal A, Hardin S, Tran BD, Medina JA, Cure JK: Imaging of the temporomandibular joint: An update. World J Radiol 6:567, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kansu L, Aydin E, Akkaya H, Avci S, Akalin N: Shrinkage of Nasal Mucosa and Cartilage During Formalin Fixation. Balkan Med J 34:458, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piette E: Anatomy of the human temporomandibular joint. An updated comprehensive review. Acta Stomatol Belg 90:103, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakaguchi-Kuma T, Hayashi N, Fujishiro H, Yamaguchi K, Shimazaki K, Ono T, Akita K: An anatomic study of the attachments on the condylar process of the mandible: muscle bundles from the temporalis. Surg Radiol Anat 38:461, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taguchi N, Nakata S, Oka T: Three-dimensional observation of the temporomandibular joint disk in the rhesus monkey. J Oral Surg 38:11, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rees LA: The structure and function of the mandibular joint. Br Dent J 96:125, 1954 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffin CJ, Hawthorn R, Harris R: Anatomy and histology of the human temporomandibular joint. Monogr Oral Sci 4:1, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapiro HH: The anatomy of the temporomandibular joint. Structural relations and therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 3:1521, 1950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wright GJ, Coombs MC, Hepfer RG, Damon BJ, Bacro TH, Lecholop MK, Slate EH, Yao H: Tensile biomechanical properties of human temporomandibular joint disc: Effects of direction, region and sex. J Biomech 49:3762, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wright GJ, Coombs MC, Wu Y, Damon BJ, Bacro TH, Kern MJ, Chen X, Yao H: Electrical Conductivity Method to Determine Sexual Dimorphisms in Human Temporomandibular Disc Fixed Charge Density. Ann Biomed Eng 46:310, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo J, Zhang L, Bacro T, Yao H: The region-dependent biphasic viscoelastic properties of human temporomandibular joint discs under confined compression. J Biomech 43:1316, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright GJ, Kuo J, Shi C, Bacro TR, Slate EH, Yao H: Effect of mechanical strain on solute diffusion in human TMJ discs: an electrical conductivity study. Ann Biomed Eng 41:2349, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gutman S, Kim D, Tarafder S, Velez S, Jeong J, Lee CH: Regionally variant collagen alignment correlates with viscoelastic properties of the disc of the human temporomandibular joint. Arch Oral Biol 86:1, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nell A, Niebauer G, Sperr W, Firbas W: Special variations of the lateral ligament the human TMJ. Clinical Anatomy 7:267, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sinha VP, Pradhan H, Gupta H, Mohammad S, Singh RK, Mehrotra D, Pant MC, Pradhan R: Efficacy of plain radiographs, CT scan, MRI and ultra sonography in temporomandibular joint disorders. Natl J Maxillofac Surg 3:2, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coogan JS, Kim DG, Bredbenner TL, Nicolella DP: Determination of sex differences of human cadaveric mandibular condyles using statistical shape and trait modeling. Bone 106:35, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karlo CA, Stolzmann P, Habernig S, Muller L, Saurenmann T, Kellenberger CJ: Size, shape and age-related changes of the mandibular condyle during childhood. Eur Radiol 20:2512, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen KD, Athanasiou KA: A surface-regional and freeze-thaw characterization of the porcine temporomandibular joint disc. Ann Biomed Eng 33:951, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calvo-Gallego JL, Commisso MS, Dominguez J, Tanaka E, Martinez-Reina J: Effect of freezing storage time on the elastic and viscous properties of the porcine TMJ disc. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 71:314, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikeda R, Oberoi S, Wiley DF, Woodhouse C, Tallman M, Tun WW, McNeill C, Miller AJ, Hatcher D: Novel 3-dimensional analysis to evaluate temporomandibular joint space and shape. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 149:416, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popovic ZB, Thomas JD: Assessing observer variability: a user’s guide. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 7:317, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]