Abstract

The past three decades have witnessed notable advances in establishing photosensitizer-antibody photoimmunoconjugates for photoimmunotherapy and imaging of tumors. Photoimmunotherapy minimizes damage to surrounding healthy tissue when using a cancer-selective photoimmunoconjugate, but requires a threshold intracellular photosensitizer concentration to be effective. Delivery of immunoconjugates to the target cells is often hindered by (I) the low photosensitizers-to-antibody ratio of photoimmunoconjugates, and (II) the limited amount of target molecule presented on the cell surface. Here, we introduce a nanoengineering approach to overcome these obstacles and improve the effectiveness of photoimmunotherapy and imaging. We show that click chemistry coupling of benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD)- Cetuximab photoimmunoconjugates onto FKR560-dye-containing poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles markedly enhances intracellular photoimmunoconjugate accumulation and potentiates light-activated photoimmunotoxicity in ovarian cancer and glioblastoma lines. We further demonstrate that co-delivery and light-activation of the two entities (BPD and FKR560) allows longitudinal fluorescence tracking of photoimmunoconjugate and nanoparticles nanoplatform in cells. Using xenograft OVCAR-5 mouse models, intravenous injection of photoimmunoconjugated-nanoparticles doubled intratumoral accumulation of photoimmunoconjugates, resulting in an enhanced photoimmunotherapy-mediated tumor volume reduction, compared to ‘standard’ immunoconjugates. We attribute this generalizable ‘Carrier Effect’ phenomenon to the successful incorporation of photoimmunoconjugates onto a nanoplatform, which modulates immunoconjugate delivery and improves treatment outcomes in vitro and in vivo.

Keywords: Photoimmunoconjugate, Targeted Nanoparticles, Glioblastoma, Ovarian Cancer, Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

INTRODUCTION

Monoclonal antibody (mAb)-targeted delivery of drugs and photosensitizers are becoming one of the preferred approaches to cancer treatment.[1–3] Photoimmunotherapy (PIT) employs photosensitizer-antibody photoimmunoconjugates (PICs) and harmless near-infrared light (λ= 650–1200 nm) to selectively induce photochemistry-mediated tumor destruction while sparing non-targeted normal tissues.[4] In addition, the fluorescence signal generated from the relaxation of excited-state photosensitizers can be used for imaging and fluorescence-guided resection of tumors.[3, 5] Unlike antibody-drug conjugates that combine recombinant mAbs and highly potent cytotoxic small-molecule drugs (IC50: 10−10-10−12 mol/L),[1] PICs consist of mAbs that are covalently bound to photosensitizers, which are nontoxic unless activated by light of a specific wavelength. This unique characteristic of photosensitizers affords an extra layer of spatiotemporal control over the conjugate’s cytotoxicity.[6]

Covalent conjugation of photosensitizers to mAbs for targeted therapy and fluorescence imaging is not a new concept.[7] Early reports of PIT were in the 1980s, the first one being pioneered by Julia Levy and colleagues using of hematoporphyrin-anti-M1 antibody conjugates in animal models.[8] This groundbreaking work was soon followed by reports from our group and others using different linking strategies, photosensitizers, and antibodies for PIT of tumors.[9–13] In 1992, the first clinical study of PIT using antibody-targeted phthalocyanine was conducted in three patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma.[14] Another encouraging human study showed fluorescein isothiocyanate-folate assemblies could target folate receptor-α frequently overexpressed in epithelial ovarian cancers (EOC) and be used for intraoperative fluorescence imaging of EOC nodules.[3] These early works laid the foundation for the recent Phase 2 clinical trial using RM-1929, a PIC composed of the hydrophilic dye IR700 linked to Cetuximab,[2] for PIT in patients with head and neck cancer.[15] Despite these promising advances, a persistent challenge for PIT continues to be the limited amount of photosensitizer delivered by PICs to the target cancer cells. This limitation is due to several reasons, including (I) the finite number of antigens (103-106) on each cancer cell surface, (II) the limited photosensitizer-to-antibody ratio of PIC commonly between 1–7, and (III) the poor tumor accessibility and accumulation of the antibodies (10−3-10−2 ID%/g) in human.[1, 16] To overcome these limitations, this study leverages nanotechnology to increase PIC accumulation in both cancer cells and solid tumors for superior near-infrared-mediated PIT and fluorescence imaging outcomes (Figure. 1). This approach, based on nanoparticle engineering, not only achieves effective PIC delivery but enhances the anti-tumor efficacy, which, to our knowledge, has never been rigorously examined.

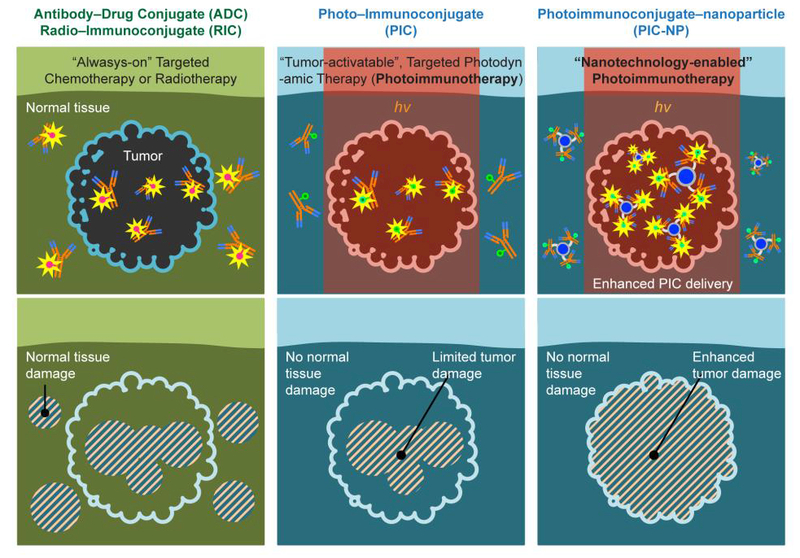

Figure. 1. A schematic explanation for selective cancer therapy with photoimmunotherapy, chemotherapy, and radiation using immunoconjugates.

While targeted chemotherapy using antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) and targeted radiation using radio-immunoconjugates (RICs) may still induce damages in normal tissues, photoimmunoconjugates (PICs) are nontoxic unless activated by cancer cells and light (hv) of a specific wavelength, thus providing additional layers of cancer selectivity. Conventional photoimmunotherapy (PIT) using PIC is, in part, limited by the low intratumoral PIC accumulation. This study introduces a PIC-NP-based approach to overcome this barrier and significantly enhance photoimmunotherapy efficacy.

Many of the photosensitizers used clinically are hydrophobic and tend to induce selfaggregation and antibody aggregation under physiological conditions, which make it challenging to synthesize stable and homogeneous PICs (i.e. free of impurities) that also retain the receptor- blocking function of native mAbs. We have established a reliable protocol to synthesize anti- Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (anti-EGFR) PICs consisting of a chimeric mAb, Cetuximab, conjugated with the photosensitizer, benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD) and a branched methoxy- polyethylene glycol (PEG).[6, 17–19] Highly self-quenched BPD photosensitizers conjugated to Cetuximab can be de-quenched by cancer cells via lysosomal proteolysis of the antibody. Dequenched photosensitizers enable both fluorescence imaging and effective PIT of tumor nodules in murine models.[6] However, the therapeutic efficacy of BPD-Cetuximab PIC in preclinical studies has remained limited due to the limited uptake of immunoconjugates in cancer cells. Here, by integrating the PEGylated BPD-Cetuximab PIC system and a biocompatible poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticle (NP), we demonstrate the concept of a dualfunctional photoimmunoconjugate-nanoparticle (PIC-NP) for selective PIT and longitudinal fluorescence imaging of drug delivery in vitro using EOC and glioblastoma (GBM) cells. In a xenograft mouse model of human EOC (OVCAR-5) that exhibits intrinsic resistance to chemotherapy, we present ex vivo fluorescence imaging of PIC-NP biodistribution, and demonstrate in vivo tumor selective PIC-NP activation and PIT efficacy. This tumor-activatable PIC-NP formulation doubles the intratumoral PIC delivery to simultaneously enhance PIT and enable the fluorescence-guided biodistribution evaluation in xenograft EOC mouse models.

Motivated by the clinical promise of using PIC for imaging and treatment in a variety of malignancies,[1–3] we present direct evidence that click-chemistry coupling of PICs onto PLGA- NPs improves PIC delivery to cancer cells, thus removing a barrier mitigating the efficacy of PIT. We attribute this ‘Carrier Effect’ to the indirect endocytosis of nanoconstruct-immobilized photoimmunoconjugates (or antibody conjugates more generally), ultimately enhancing its theranostic effects.

RESULTS

Subhead 1: Synthesis and characterization of photoimmunoconjugate-nanoparticle (PIC-NP)

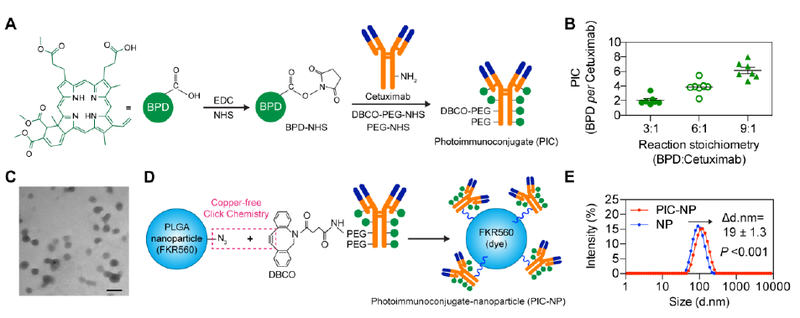

The photoimmunoconjugate (PIC) used in this study is composed of clinically approved BPD and anti-EGFR mAb Cetuximab (Figure. 2A) previously shown to reduce ovarian cancer micrometastases in vivo upon light activation.[20] Reaction of the N-hydroxysuccinimidyl (NHS) ester of BPD and Cetuximab at 3:1, 6:1 and 9:1 molar ratios resulted in PIC formulations with approximately 2, 4, and 6 BPD molecules per Cetuximab, respectively (Figure. 2B), suggesting a conjugation efficacy of approximately 67%. To facilitate the click conjugation of PIC with azide-functionalized nanoparticles, a short NHS-activated PEG4 chain ending with a dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO) group was attached to the PIC. Biodegradable PEG-PLGA polymeric nanoparticles (NPs) used in this study were composed of 12 mol% PLGA-PEG-azide and 36 mol% methoxy-poly(ethylene glycol)-b-poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-FKR560 dye (mPEG- PLGA-FKR560), and were ~80 nm in diameter (Figure. 2C) with a narrow size distribution (polydispersity index, PdI<0.1). Immobilization of DBCO-containing PIC to azide- functionalized PEG-PLGA NPs via copper-free click chemistry (Figure. 2D) increased the NP system’s size by ~19 nm (P<0.001) and resulted in the formation of monodispersed PIC-NPs around 100 nm in diameter (PdI≤0.11) (Figure. 2E, Table 1).

Figure. 2. Synthesis of photoimmunoconjugate-nanoparticles (PIC-NPs).

(A)Schematic depiction of PIC synthesis. Benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD) photosensitizers were conjugated to PEGylated Cetuximab via carbodiimide crosslinker chemistry. (B) The stoichiometry of BPD reacting with Cetuximab was varied to achieve PIC with BPD-to-Cetuximab molar ratios of approximately 2:1, 4:1 and 6:1 (n = 7). (C) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, Philips CM10) image of poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PEG-PLGA) polymeric nanoparticles prepared via nanoprecipitation method. Scale bar 100 nm. (D) Schematic depiction of PIC-NP synthesis via copper-free click chemistry. Azide-containing FKR560 dye-loaded PLGA nanoparticles were reacted with the dibenzocyclooctyne (DBCO)-containing PICs to form PIC-NPs. (E) Covalent conjugation of PICs onto 80 nm PEG-PLGA NPs resulted in the formation of monodisperse PIC-NPs around 100 nm in diameter (PdI≤0.11) as determined by Zetasizer dynamic light scattering (n = 15–18).

Table 1.

Physical Parameters of PLGA nanoparticle (NP) and photoimmunoconjugate-nanoparticle (PIC-NP).

| Formulation | PIC (BPD: Cetuximab ratio)* | Size (d. nm) | PdI | Zeta potential (mV) | Conjugation efficiency (%)** |

Number of PIC per NP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP | N/A | 80.8 ± 3 | 0.03 ± 0.03 | −5.7 ± 0.6 | N/A | N/A |

| PIC-NP | 6.1 ± 1.1 | 98.8 ± 7.2 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | −3.6 ± 1.0 | 51.9 ± 11.4 | ~40.6 |

| PIC-NP | 3.9 ± 0.9 | 99.3 ± 3.4 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | −4.2 ± 2.1 | 53.2 ± 11.8 | ~47.5 |

| PIC-NP | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 103.1 ± 7.4 | 0.11 ± 0.06 | −4.1 ± 1.9 | 71.3 ± 14.3 | ~74.8 |

Photoimmunoconjugate (PIC): BPD photosensitizers were conjugated to Cetuximab monoclonal antibody at various ratios.

Conjugation efficacy (%): The molar ratio of PIC conjugated onto the nanocarrier to the total PIC added initially.

The surface charge of the PIC-NP was engineered to be neutral-to-slightly negative (−4 mV) by incorporating PEG-PLGA chains with carboxylic end groups.[21] Changing the BPD-to- Cetuximab ratio of PIC did not alter the overall hydrodynamic diameter and surface charge of PIC-NPs (Table 1, Figure. S1). However, reducing the BPD-to-Cetuximab ratio of PIC from 6:1 to 2:1 increased the PIC-NP conjugation efficiency from 51% to 71%. This corresponded to approximately 40, 47 and 74 PICs per NP, at BPD-to-Cetuximab ratios of 6:1, 4:1, and 2:1, respectively (Table 1). The purity of PIC remains high after immobilization onto the NP, showing undetectable levels of free BPD by gel fluorescence imaging analysis following sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Figure. S2).

Subhead 2: Stability and photoactivity of PIC-NP

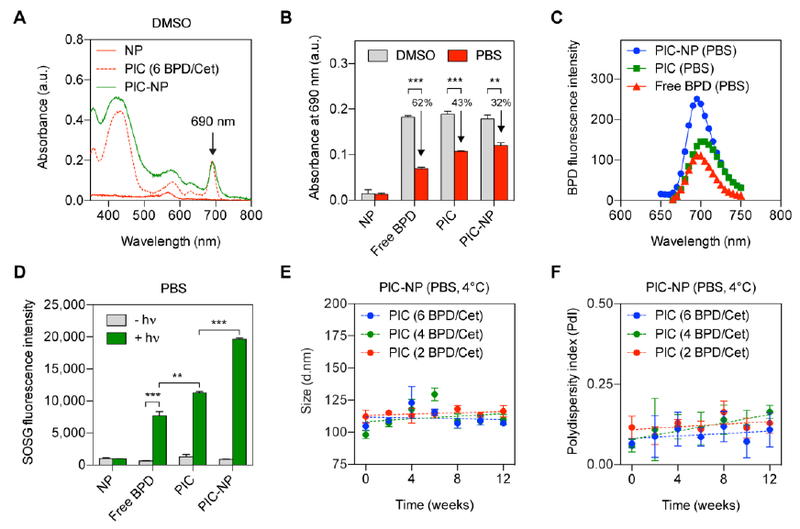

Dispersion of hydrophobic BPD molecules in biologically relevant media can cause irreversible aggregation and loss of photosensitizing capability.[22] Tethering BPD molecules to PEGylated mAb not only enhances BPD stability, but allows spatial control of BPD de- quenching through responding to cancer-associated lysosomal catabolism.[17] We previously confirmed that increasing the BPD-to-Cetuximab ratio of PIC from 2:1 to 6:1 enhances the BPD excited singlet state quenching from three to seven folds.[17] These self-quenched BPD molecules on PIC can be de-quenched by cancer cells upon lysosomal proteolysis of mAb, thereby increasing the tumor specificity in vivo.[6] Here, our goal is to develop a PIC-NP system that incorporates two synergistic therapies (i.e. BPD and Cetuximab) and an FDA-approved PLGA drug delivery nanoplatform to realize a photochemistry-based, targeted therapy with both fluorescence imaging and multi-agent delivery capabilities. Prior to the stability and photoactivity evaluations, we verified that click chemistry coupling of PIC to FKR560 dye- containing NP does not alter the PIC absorbance peak (Q band of BPD) at 690 nm (i.e. excitation wavelength for photoimmunotherapy) in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Figure. 3A). The absorbance (690 nm; Figure. 3B) and fluorescence (Ex: 450 nm, Em: 650–750 nm; Figure. 3C) of free BPD, PIC, and PIC-NP were assessed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and DMSO. Owing to the aggregation of BPD molecules, the absorbance at 690 nm for free BPD and PIC in PBS were reduced by approximately 62% and 43%, respectively, compared to those fully dissolved in DMSO (Figure. 3B). PIC-NP showed a less pronounced (32%) loss of BPD’s 690 nm absorbance peak in PBS compared to that in DMSO, suggesting BPD molecules are less prone to aggregation when PICs are immobilized onto NPs. The BPD fluorescence emission of PIC-NP was approximately 2 and 1.5 folds higher than that of free BPD and PIC alone dissolved in PBS, respectively (Figure. 3C). Using the singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG) fluorescent probe, we further tested if light activation of PIC-NP could produce cytotoxic singlet oxygen (1O2) more efficiently in PBS, compared to photo-activated free BPD or PIC alone. Upon 690 nm laser irradiation, the SOSG fluorescence intensity generated by PIC-NP was markedly higher than that generated by PIC alone and free BPD (Figure. 3D). These data indicate that PIC-NP improves the cytotoxic1O2 production of BPD in PBS during light activation, compared to PIC alone and free BPD molecules. The photoresponsive PIC-NPs were found to be stable during twelve weeks of dark-storage at 4°C, showing no significant changes to their overall size (Figure. 3E) or monodispersity (Figure. 3F). We further showed that PIC-NPs remain stable in mouse serum-containing PBS at 37°C for at least 2 days (Figure. S3).

Figure. 3. Photophysical, photochemical and stability assessment of photoimmunoconjugate-nanoparticles (PIC-NPs) in various solvents.

(A) Representative absorbance spectra of PIC-NPs, PICs, and NPs in DMSO. BPD photosensitizers on PICs were de-quenched in DMSO, showing a strong Q-band at 690 nm. A diode laser (690 nm) is used to activate the Q-bands of PIC and PIC-NP for photoimmunotherapy. FKR560 dye-containing NP does not absorb light at 690 nm. (B) A comparison of 690 nm absorbance of free BPD, PIC, and PIC-NP in DMSO and phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at a fixed BPD concentration. NPs show negligible baseline absorbance at 690 nm in both DMSO and PBS. Reduced absorbance values for free BPD, PIC, and PIC-NP were observed in PBS, compared to those in DMSO. This is presumably due to the aggregation of BPD molecules under physiologically relevant conditions (n = 3 **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, two-tailed t-test). (C) At a fixed BPD concentration, the BPD fluorescence intensity of PIC-NP was significantly higher than that of free BPD and PIC dissolved in PBS (n = 8). (D) SOSG reports1O2 production from light (hv)-activated NP, free BPD, PIC and PIC-NP in PBS. (n > 4 **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, Mann-Whitney U test) (E, F) Three-month stability of PIC-NPs with different BPD-to-Cetuximab ratios (BPD/Cet at 6, 4, 2) in PBS was determined by (E) size and (F) polydispersity. Samples were stored under dark conditions at 4 °C (n = 3).

Subhead 3: Conjugating tumor-selective, activatable PIC to NPs improves photosensitizer delivery in vitro

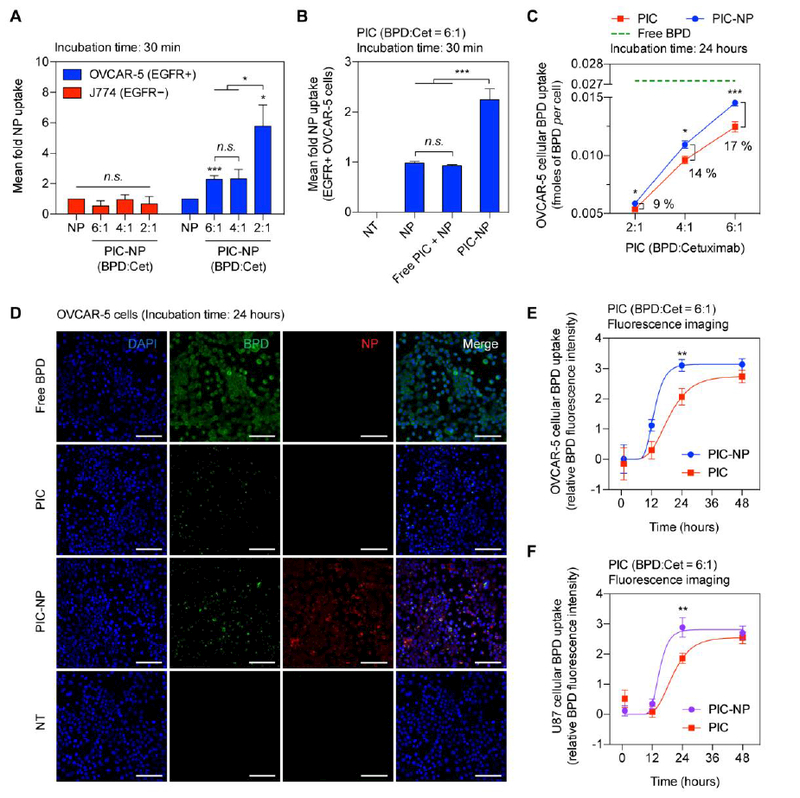

Our previous work showed that conventional PIC is tumor-selective and activatable by ovarian cancer micrometastases for fluorescence imaging in vivo.[6] To test if the next- generation PIC-NPs can also selectively target and deliver NPs to EGFR-overexpressing cancer cells, we first compared the uptake of PIC-NPs and non-targeted NPs in EGFR+ OVCAR-5 cells and EGFR− J774 macrophages at a fixed NP concentration (0.5 μM of FKR560 dye). After a 30- minute incubation at 37°C, PIC-NPs exhibited 2–6 folds higher uptake in EGFR+ OVCAR-5 cells, compared to non-targeted NPs (Figure. 4A). In contrast, the uptake of PIC-NP in EGFR− J774 macrophages was found to be similar to that of non-targeted NP. Recognition and uptake of PIC-NPs by EGFR+ cells increases with decreasing BPD-to-Cetuximab ratios of the PIC, suggesting that excessive BPD loading on Cetuximab can result in the loss of cancer cell- selective targeting. To further validate that the cancer-selectivity of PIC-NP relies on the successful click chemistry coupling of PIC-NP, we showed that OVCAR-5 cells co-incubated with free PICs and free NPs does not affect NP uptake (Figure. 4B).

Figure. 4. Selective binding and fluorescence imaging of PIC-NP in cancer cells overexpressing epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).

(A) The selectivity of PIC-NPs with various BPD-to-Cetuximab ratios (BPD:Cet at 6, 4, 2) was evaluated in EGFR+ human ovarian cancer (OVCAR-5) cells and EGFR− mouse macrophage (J774) cells after 30 minutes of incubation. All targeted PIC-NP uptake measurements were normalized to non-targeted NP alone controls (n = 4–10, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, n.s., non-significant, two-tailed t-test). Asterisks denote significance compared to the NP group or amongst the indicated groups in each cell line. (B) Selective uptake of NPs was only observed when using PIC-NP, but not with NP alone or a mixture of free-form, unconjugated PIC and NP (Free PIC + NP). The BPD-to-Cetuximab ratio of PIC was fixed at six (n > 10, ***P<0.001, n.s., non-significant, One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test). (C) The OVCAR-5 intracellular BPD concentration was determined at 24 hours post-incubation with (i) free BPD (green), (ii) PIC (red), or (iii) PIC-NP (blue) using extraction methods. The BPD concentration for all groups was fixed at 0.25 μM (n = 6–12, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, two-tailed t-test). (D) Representative confocal fluorescence microscopy of BPD photosensitizer (green) and nanoparticle (red) in OVCAR-5 cells incubated with (i) Free BPD, (ii) Photoimmunoconjugate alone (PIC), (iii) Photoimmunoconjugate-nanoparticle (PIC- NP), and (iv) No-treatment (NT) for 24 hours. Nuclear staining (blue-fluorescence, DAPI); Scale bar 100 μm. (E, F) Quantification of (E) OVCAR-5 and (F) U87 intracellular BPD fluorescence signals at 1, 12, 24, and 48 hours post-incubation with (i) PIC or (ii) PIC-NP at the same BPD concentration of 0.25 μM (n = 5–19, **P<0.01, two-tailed t-test).

PIC, based on BPD and Cetuximab, has been shown to improve the selective delivery of BPD and reduce off-target toxicities, but also potentially limits the intracellular accumulation of the phototoxic payload. EGFR+ OVCAR-5 cells incubated with PIC (2 BPD per Cetuximab) for 24 hours showed significantly (6 folds) lower BPD uptake (0.005 fmoles BPD/cell) as compared to those treated with free-form BPD (0.03 fmoles BPD/cell) (Figure. 4C). By increasing the BPD:Cetuximab loading ratio of PIC from 2:1 to 6:1, ( Figure. 4C), a proportional increase in the intracellular BPD accumulation from 0.005 to 0.012 fmoles BPD/cell was achieved. To assess if chemical immobilization of PICs onto NPs can further improve the cellular delivery of PIC and BPD, the uptake of PIC-NP and PIC was evaluated after 24-hour incubation with OVCAR-5 cells at a fixed BPD concentration of 0.25 μM. Compared to PIC alone, we observed that PIC- NPs enhanced (P<0.05) the intracellular BPD accumulation by 9, 14 and 17%, at BPD:Cetuximab molar loading ratios of 2:1, 4:1, and 6:1, respectively (Figure. 4C).

One of the key advantages of PIC is its imaging capabilities for resolving microscopic tumors and determining optimal time points for photoimmunotherapy.[6] Building on the selective accumulation of PIC-NP in EGFR-overexpressing cancer cells, we monitored both the PIC-NP and PIC uptake longitudinally by confocal imaging of BPD and FKR560 dye-containing NP in two EGFR+ cell lines, OVCAR-5 (Figure. 4D) and U87 (Figure. S4). We observed OVCAR-5 cells treated with PIC-NP showed a ~33% increase in intracellular BPD fluorescence intensity at 24 hours post-incubation, compared to cells treated with PIC alone (Figure. 4E). Similarly, the enhancement of intracellular BPD accumulation by PIC-NP at an optimal 24 hours was reflected in U87 cells (Figure. 4F). The saturation of BPD fluorescence intensity at 48 hours is presumably due to the limited number of EGFR binding sites and proteolysis of mAb in cancer cells. Moreover, quantification of confocal images showed an increased intracellular BPD-to-NP fluorescence signal at 24 hours following PIC-NP incubation in OVCAR-5 and U87 cell lines (Figure. S5). This confirmed that self-quenched BPD on PIC-NPs was de-quenched following uptake by EGFR positive cancer cells, in agreement with our previous observations with PIC alone.

Subhead 4: PIC-NP improves photoimmunotherapy efficacy in vitro

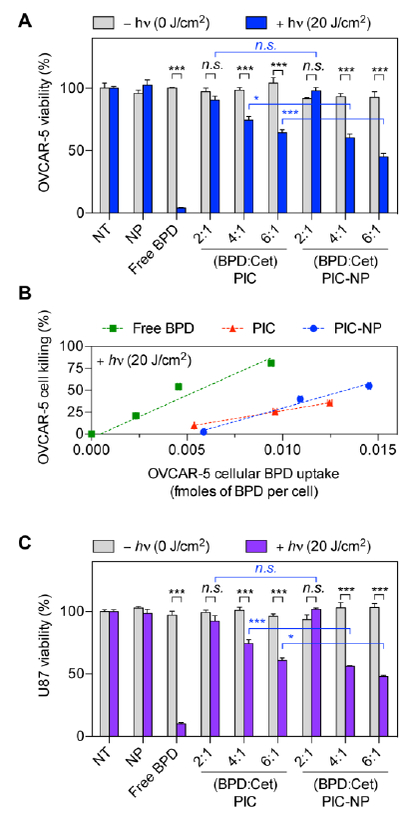

There is a critical need to improve the limited intracellular delivery and therapeutic efficacy of immunoconjugates. Above, we showed that immobilization of PIC onto NPs not only enhances the intracellular delivery of PIC, but also maintains the cancer selectivity and photo- activatability of PIC for cancer fluorescence imaging. We next explore whether this increase in BPD delivery translates to an improvement in phototoxicity in two cancer cell lines (Figure. 5A-C). Free BPD, PIC, and PIC-NP at a fixed BPD concentration of 0.25 μM, and NP alone all showed negligible dark toxicity in OVCAR-5 and U87 cells (Figure. 5A and 4C, grey bars). The selection of a 24-hour drug-light interval for photoimmunotherapy was informed by confocal imaging, which showed maximal BPD fluorescence signal for PIC-NP and PIC (Figure. 4E) after 24 hours of incubation. While a 20 J/cm2 light dose in OVCAR-5 cells treated with 0.25 μM BPD killed over 90% of cells (Figure. 5A), the fraction of cell death was dramatically reduced to <5% when using PIC with a BPD:Cetuximab molar ratio of 2:1, which is likely due to the limited intracellular BPD accumulation of 0.005 fmoles BPD/cell (Figure. 4C). Increasing the BPD:Cetuximab molar ratios of PIC from 2:1 to 4:1 and 6:1 modestly restored the immunoconjugate phototoxicity to 15% and 30% cell death, respectively, in OVCAR-5 cells (Figure. 5A). On the other hand, PIC-NP with BPD-to-Cetuximab ratios of 4:1 and 6:1 significantly amplified potency of photoimmunotherapy by an additional 20% in OVCAR-5 cells, compared to PIC alone (5A). This improvement of phototoxicity correlates linearly to the enhancement of intracellular BPD delivery (Figure. 5B). Interestingly, the phototoxicity efficiency—determined by the extent of cell death per mole of intracellular BPD—was found to be similar between free PIC and PIC-NP formulations, suggesting that once the PIC is inside the cell and is broken down, the NP no longer plays a role in PIT efficacy (Figure. 5B). Similarly, the enhancement of photoimmunotherapy efficacy by PIC-NP, compared to PIC alone, was reflected in U87 glioblastoma cells (Figure. 5C).

Figure. 5. The phototoxicity of PIC-NP, PIC and free BPD in human ovarian cancer and glioblastoma (GBM) cell lines.

The BPD concentration for all groups was fixed at 0.25 μM. Light dose was either 0 J/cm2 or 20 J/cm2. (A) EGFR-overexpressing OVCAR-5 cells were incubated with (i) NP alone, (ii) free BPD, (iii) PIC, or (iv) PIC-NP at 37°C for 24 hours prior to light irradiation for photoimmunotherapy (PIT). Cell viability via MTT assay was evaluated at 24 hours after photoimmunotherapy (PIT). (B) The percentage of cell killing was correlated with OVCAR-5 cellular BPD uptake to determine the phototoxicity efficiency (i.e. the extent of cell death per mole of intracellular BPD). (C) EGFR-overexpressing U87 cells were incubated with (i) NP alone, (ii) free BPD, (iii) PIC, or (iv) PIC-NP at 37°C for 24 hours prior PIT. Cell viability was evaluated at 24 hours after PIT (n = 4–18, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001, n.s., non-significant, twotailed t-test).

Subhead 5: Fluorescence imaging of PIC-NP biodistribution in vivo and PIC-NP-mediated photoimmunotherapy destruction of xenograft tumors.

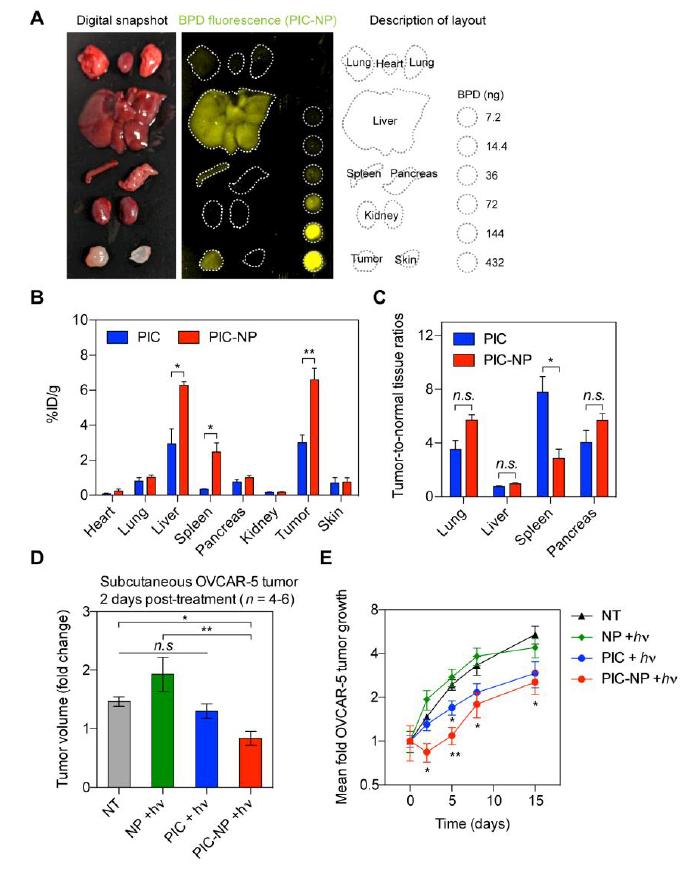

We showed that PIC-NP with a BPD-to-Cetuximab ratio of 6 resulted in the highest intracellular concentration of BPD (Figure. 4C). Therefore, we next test if the PIC-NP formulation could enhance intratumoral BPD accumulation in mice bearing subcutaneous OVCAR-5 tumors by comparing the biodistribution of PIC-NP and PIC using a fixed BPD-to-Cetuximab ratio (6:1) and BPD concentration (0.25 mg/kg) at 24-hours post-intravenous injection. At the administered dose, we did not observe any change in animal behavior (i.e. mobility, posture) or deaths that may be associated with the toxicity of PIC-NP or PIC. The BPD fluorescence signal of PIC in harvested tumors and organs were measured, spectrally unmixed, and quantified using appropriate standards (Figure. 6A; Figure. S6). These results confirmed that PIC-NP significantly doubled the intratumoral PIC accumulation from 3%ID/g to 6.5%ID/g in vivo compared to ‘PIC’ alone (Figure. 6B). The above observations motivated us to compare the tumor-to-normal tissue uptake ratios of PIC-NP and PIC in common sites of PLGA nanoparticle accumulation, including lung, liver, spleen and pancreas (Figure. 6C). We observed that PIC-NP and PIC exhibited similar tumor-to-normal tissue uptake ratios in lung, pancreas and liver.

Figure. 6. Biodistribution and phototoxicity of PC-NP and PIC in OVCAR-5 human ovarian cancer xenograft mouse model.

Mice bearing subcutaneous OVCAR-5 tumors were intravenously injected with (i) PIC-NP or (ii) PIC at a fixed BPD-to-Cetuximab ratio of 6:1 and a BPD concentration of 0.25 mg/kg. At 24 hours post-injection, animals were either euthanized for tissue collective or subjected to photoimmunotherapy (PIT) at 40 J/cm2 light dose. (A) Representative digital snapshot and BPD fluorescence imaging of excise tissues at 24 hours post PIC-NP injection, with BPD standards of known concentrations. Harvested tumors and organs were measured, spectrally unmixed, and quantified using the standards. (B) Biodistribution of PIC and PIC-NP at 24 hours post injection in tumor and different organs (n = 4 animals per group, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, n.s., non-significant, two-tailed t-test). (C) Tumor-to-normal tissue ratios of PIC and PIC-NP in lung, liver, spleen, and pancreas were determined at 24 hours post injection (n = 4 animals per group, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, n.s., non-significant, two-tailed t-test). (D) At two days after PIT, maximal tumor growth inhibition in OVCAR-5 animal models was observed using PIC-NP (n = 4–6 animals per group, ***P<0.001, n.s., non-significant, One-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls’ post hoc test). (E) Subcutaneous OVCAR-5 tumor volumes were longitudinally monitored after PIT using PIC-NPs, PICs and NPs (n = 4–6 animals per group, **P<0.01, *P<0.05, two-tailed t-test). Asterisks denote significance compared to the no-treatment (NT) group or amongst the indicated groups at each time point.

We further explored whether PIC-NP-mediated increase in intratumoral PIC delivery translates to enhanced phototoxicity. To assess the ability of PIT to control localized tumors in vivo, treatments were performed 14 days following subcutaneous implantation of OVCAR-5 human EOC cells in mice. The following treatments were randomly administered to mice: (i) No-treatment (NT), (ii) NP + laser (NP + hv), (iii) PIC + laser (PIC + hv), (iv) PIC-NP + laser (PIC-NP + hv). A 24-hour photosensitizer-light interval was used to achieve a substantial accumulation and activation of PIC in the tumor, based on our data (Figs. 3E, 3F, 5A, 5B) and previous experience. Tumors treated with ‘PIC-NP + hv’ exhibited a significant reduction of tumor volume by ~45% two days after treatment, whereas continued tumor growth was observed in ‘NT’, “NP + hv’ and ‘PIC + hv’ groups over this same period (Figure. 6D). At 5 days after treatment, tumor regrowth was observed in ‘PIC-NP + hv’ treated mice. Despite this tumor regrowth, at 5 days post-treatment, the mean tumor volume reduction in mice treated with ‘PIC-NP + hv was 55%, while only 30% tumor inhibition was observed in ‘PIC + hv’ treated mice, compared to ‘NT’ animals. Light activation of NP (NP + hv) did not result in any change in tumor volume compared to the ‘NT’ group. These data indicate that a single dose of PIC-NP- based PIT provides an enhanced acute phototoxicity compared to using PIC alone.

DISCUSSION

Molecular targeted, activatable PIT is an emerging photochemical modality in theranostic medicine for a variety of malignancies, including EOC, GBM and head and neck cancers. In this report, we present the first direct evidence that click-chemistry coupling of PICs onto NPs allow cancer cells to take up PICs more efficiently, thus removing a barrier mitigating the efficacy of PIT. One the other hand, mixtures of unconjugated PICs and NPs alone did not facilitate the cells to take up PICs more efficiently. We refer this ‘Carrier Effect’ to the indirect endocytosis of photoimmunoconjugates (or antibody conjugates) that successfully harbor a nanoconstruct (or nanoparticle) to provide enhanced theranostic actions.

Uniquely, our PIC-NP system incorporates two synergistic therapies (i.e. BPD and Cetuximab) and an FDA-approved PLGA drug delivery nanoplatform to realize a photochemistry-based, targeted therapy with both fluorescence imaging and multi-agent delivery capabilities. Prior elegant studies have established the two-fold selectivity of PIC based on BPD-Cetuximab: (I) Upon selective binding of PIC to cancer-associated EGFR, tumor-targeted activation occurs within cancer cells when enhanced lysosomal proteolysis of Cetuximab de- quenches BPD photosensitizers and, subsequently, (II) near-infrared light activation of the dequenched BPD molecules produces fluoresce signal and highly cytotoxic molecular species for imaging and PIT, respectively. In this study, we observed that immobilization of PICs onto the NP surface via click-chemistry modestly enhanced the BPD absorbance and fluorescence, and improved singlet oxygen yields by up to 50%. Given that others have achieved the stable retention of mAb inside PLGA nanoplatforms,[23] it is not surprising that our results suggest the stability and functionality of PICs were also improved on the surface on PLGA NPs. While PIC-NP with an increased BPD -to-Cetuximab ration can lead to a higher intracellular concentration of BPD, we showed that increasing the BPD-to-Cetuximab ratio of PIC compromises the intracellular uptake of the entire nanoparticle construct. This is presumably due to the decreased targeting ability of Cetuximab. All together, these data suggest that a fine balance between the numbers of ‘BPD-per-Cetuximab’ and ‘PIC-per-NP’ is critical to achieve a stable and selective PIC-NP system that can efficiently deliver maximal amount of BPD photosensitizer and nanoparticle to the targeted tissue, while maintaining sufficient selectivity to minimize uptake in healthy cells. Moreover, the photoimmunotherapy efficacy can be further improved by using higher light dose.

In this study, we observed that PIC-NP allows cancer cells to take up PIC five times more efficiently in animal tumor models than in monolayer cancer cell cultures. This is presumably due to the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect via the elevated blood retention of the PIC-NP system. While conventional immunoconjugates generally suffer from poor tumor penetration, our data indicate that this next generation PIC-NP improves PIC biodistribution. In addition to enhanced tumor accumulation, PIC-NPs, like most nanoparticles, are also taken up by the liver, spleen and other parts of the reticuloendothelial system (RES). However, for PIC-NPs, no toxic side effects should be observed since this approach affords multiple layers of selective photo-activated toxicity: BPD will only be phototoxic after dequenching through antibody proteolysis, and when irradiated with 690nm light. It is important to note that, while our previous study showed conventional PIC requires a relatively high dose of 2 mg/kg BPD to be effective in vivo,[6] here, we demonstrate that potent acute tumor volume reduction was achieved at only 0.25 mg/kg BPD with our PIC-NP system. Animals treated with ‘PIC-NP + hv’ showed higher tumor reduction rate than those treated with ‘PIC + hv’ in the first few days after treatment. However, at two weeks after a single low-dose treatment, the tumor volumes were not significantly different between the ‘PIC-NP + hv’ and ‘PIC + hv’ treated animal. Reports of short-term response to cancer therapeutics could be critical for the development of palliative care, while long-term responses is needed to improve overall survival outcomes. We believe that multiple PIT treatment cycles and incorporation of a second therapeutic modality into the NP platform will significantly improve the long-term therapeutic outcomes of PIT. With the frequent use of fiber optics in the clinic, confined and intraoperative (or endoscopic) light delivery to tumors at complex anatomical sites such as brain, lung, and pancreas has been successful.[24, 25] Advances in fiber optic technology have made real-time fluorescence monitoring of PIC-NP pharmacokinetics and biodistribution possible, and warrant further studies for image-guided drug delivery and surgery.

Photoimmunotherapy is now being evaluated in the clinic as a salvage treatment for recurrent cancer in patients who have failed conventional therapies. Our findings suggest that successful coupling of PICs to nanoparticles not only improves immunoconjugate delivery to tumor, but also offers a forward-looking opportunity to deliver a significant amount of a second therapeutic or imaging agent to further bolster the theranostic benefits of PIC. A fine balance between the number of photosensitizer-per-mAB and PIC-per-NP is critical to achieve a stable and selective PIC-NP nanosystem that can efficiently deliver a maximal phototoxic payload to the target tissue. This study utilizes dye-loaded biodegradable PLGA nanoparticles as a proof-of- concept to significantly improve the delivery of two theranostic entities to cancer cells. Moving forward, validation of this ‘Carrier Effect’ for enhancement of intratumoral PIC accumulation using other types of nanoplatforms, such as liposomes, micelles, and inorganic nanoparticles, is essential to ensure the generalizability of this unique phenomenon.

CONCLUSION

Light activatable immunoconjugates have already shown promise for PIT and fluorescence-guided resection in patients suffering from incurable malignancies in early clinical trials. While possessing a number of unique advantages, PIT and fluorescence imaging for oncological diseases can be hampered by therapeutic inefficiency resulting from inadequate photosensitizer accumulation and/or light delivery. We demonstrated that successful click chemistry coupling of immunoconjugates to nanoparticles could significantly improve photosensitizer delivery to cancer cells in two EGFR-overexpressing cancer cell lines in vitro and in a xenograft tumor mouse model. This next generation PIC-NP delivery approach offers a unique opportunity to monitor disease, destroy cancer cells and co-deliver a follow-up treatment more efficiently, and thus merits further investigations in preclinical and clinical settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Photoimmunoconjugate Synthesis and Characterization:

Conjugation of the photosensitizer benzoporphyrin derivative (BPD) to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody Cetuximab was achieved using carbodiimide crosslinker chemistry. Briefly, PEGylation of Cetuximab was first carried out by addition of mPEG-NHS in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (200 μL; 10,000 MW; 4 mg/mL) dropwise to Cetuximab (2 mL; 2 mg/mL) and allowed to stir overnight at 400 rpm at room temperature. PEGylated Cetuximab was reacted with the N- hydroxysuccinimidyl ester of BPD (BPD-NHS), and dibenzocyclooctyne-PEG4-N- hydroxysuccinimidyl ester (DBCO)-PEG4-NHS (649.69 MW; Sigma) at 1:3:2.5, 1:6:2.5, and 1:9:2.5 molar ratios for 4 hours. The resulting photoimmunoconjugate was purified using a 7kDa MWCO Zeba spin desalting column (Thermo) pre-equilibrated with DMSO (30% in PBS), and then washed in a 20 mL 30kDa MWCO centrifugal filter tube (Amicon) 3 times with 5% DMSO in PBS prior to storage at 4°C. The purity of the photoimmunoconjugates was assessed by gel fluorescence imaging analysis following sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Supplementary Methods). The BPD concentration of PIC was estimated by absorbance in DMSO using the established molar extinction coefficient of BPD in DMSO (~34,895 M−1cm−1 at 687 nm). The protein content of PIC was evaluated by BCA protein assay (Thermo). BPD conjugation efficacy was determined by dividing the amount of antibody- conjugated BPD in the purified PIC by the total amount of BPD added initially.

Synthesis of PLGA-PEG Polymeric Nanoparticles:

Polymeric nanoparticles were synthesized via the nanoprecipitation method. Briefly, poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-poly(ethylene glycol)-carboxylic acid endcap (PLGA-PEG-COOH; Mw: 22,983; 6 mg), PLGA-PEG-azide, (Mw: 34,116; 1 mg) and PLGA-PEG labeled with the FKR560 dye (mPEG-PLGA-FKR560; Methoxy-Poly(ethylene glycol)-b-Poly(lactide-co-glycolide)-FKR560; Mw: 16,468; 6 mg) (PolySciTech, Akina) were co-dissolved in 1 mL of acetone, and then added dropwise to a mixture of deionized (14 mL) water plus acetone (1 mL) stirring at 1000 rpm for 4 hours. The nanoparticles form instantaneously as a result of the rapid aggregation of PLGA tails in aqueous solution, allowing the hydrophilic PEG chains to surround the relatively hydrophobic core. The nanoparticles are filtered with a 200-nm PTFE membrane (Pall) and washed twice with PBS using a tangential flow filters (30,000 NMWL, Millipore). The concentration of FRK560 dye in polymeric nanoparticles was determined by UV-Vis spectroscopy with appropriate standard curves. Particle size, size distribution, and zeta potential of the nanoparticles were measured using a Zetasizer (Nano ZS, Malvern).

Nanoformulation and characterization of cancer-targeted Photoimmunoconjugate- nanoparticle (PIC-NP):

Photoimmunoconjugates were conjugated to polymeric nanoparticles at a ratio of ~90:1 using metal-free click chemistry by overnight reaction between azide and DBCO. The resulting PIC-NP was purified via Sepharose CL-4B size exclusion chromatography. The purified PIC-NP was collected, stored at 4°C, and longitudinally analyzed for size and polydispersity index (PdI) (Nano ZS, Malvern, Ltd.). FKR560 dye and BPD photosensitizer concentrations were measured by UV-Vis spectroscopy with appropriate standard curves. Conjugation efficacy is defined as the molar ratio of PIC conjugated onto the nanocarrier to the total PIC added initially. Singlet oxygen sensor green (SOSG) probe was utilized to detect the production of1O2 upon red light irradiation of PIC-NP and appropriate controls at a fixed BPD photosensitizer concentration. A microplate reader (Molecular Devices) acquired fluorescence signals of SOSG (Ex/Em: 504/525 nm) before and after light irradiation (690 nm, 150 mW/cm2, 20 J/cm2, Intense-High Power Devices, Series-7401) to evaluate the1O2 production from each sample.

Cell culture, in vitro PIC-NP selectivity and photoimmunotherapy:

OVCAR-5 human epithelial ovarian cancer, U87 human glioblastoma, and J774 murine macrophages were obtained from ATCC, cultured as per manufacturer’s instructions, and tested mycoplasma-free. For selectivity studies, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) positive OVCAR-5 cells and EGFR negative J774 cells were plated in 35-mm petri dished at a cell density of 400,000 cells per dish to allow overnight culture at 5% CO2 and 37°C. Cells were incubated with PIC-NP or non-targeted NP alone at a fixed NP concentration of 0.5 μM FKR560 for 30 minutes at 37°C in serum-containing medium. After incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS and then dissolved in Solvable™ (0.5 mL). A microplate reader (Molecular Devices) was utilized to acquire fluorescence signal of FKR560 (Ex/Em: 562/584) to determine the selective binding properties of different samples towards different cell lines. For photoimmunotherapy and BPD uptake studies, cancer cells were incubated with PIC-NP, PIC alone, or appropriate controls at a fixed BPD photosensitizer concentration (0.25 μM) for 24 hours, at which time cells were irradiated with 690 nm light with a total light dose of 20 J/cm2 at an irradiance of 150 mW/cm2. 24 hours after light irradiation, cell viability was determined by MTT assay. To quantify the intracellular BPD uptake 24 hours after PIC-NP (or PIC) incubation, cells were washed twice with PBS and then dissolved in 0.5 mL of Solvable™. A microplate reader (Molecular Devices) was utilized to acquire fluorescence signal of BPD (Ex/Em: 430/694), which is converted to moles of BPD based on appropriate standard curves (Figure. S2).

Confocal fluorescence imaging of PIC-NP uptake:

OVCAR-5 cells and U87 cells were cultured in 24-well plates (glass bottom) at a cell density of 50,000 per well. After 24 h of culture, PIC-NP, PIC, NP, and free BPD samples at fixed concentrations of BPD (0.25 μM; 1 mL) and NP were added to replace the original cell culture medium. The confocal images of cells were collected at 1, 12, 24, and 48 hours after incubation. DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was utilized to stain the nucleus of cells prior to confocal fluorescence imaging (Olympus FluoView 1,000 confocal microscope) using a 10 × 4 numerical aperture (NA) or a 20 × 0.75 NA objective. Excitation of DAPI, BPD (from PIC), and FKR560 dye (from NP) was carried out using 405 and 559-nm lasers, respectively, with appropriate filters.

Xenograft mouse model of ovarian carcinoma:

Animal studies were carried out according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). A subcutaneous xenograft mouse model of human ovarian cancer (OVCAR-5) was established by implanting 1.5 × 106 OVCAR-5 cells (suspended in a medium-Matrigel mixture; 100 μL) into the right hind flank of 6-week old female Swiss nude mice. Tumors were allowed to grow for two weeks, at which point treatment was initiated. Tumor size was record using calipers and tumor volume estimated using the formulation V = (L × W × H) π/6, where V is tumor volume, W is tumor width, L is tumor length, and H is tumor height.

In vivo fluorescence imaging of PIC-NP biodistribution and photoimmunotherapy:

In vivo biodistribution studies of PIC and PIC-NP were carried out using a Maestro imaging system (Cambridge Research and Instrumentation, Inc.). Mice bearing subcutaneous OVCAR-5 tumors were intravenously injected with PIC or PIC-NP (at a fixed BPD concentration of 0.25 mg/kg, and BPD:Cetuximab of 6:1). At 24 hours after injection, animals were euthanized and tissues (kidneys, pancreas, liver, spleen, heart, lungs, skin, and tumor) were harvested for fluorescence imaging using 490nm/580nm excitation and emission filters at 5 second exposure time to determine the BPD fluorescence signal from each organ. Autofluorescence and background were subtracted from each organ using an untreated mouse. Spectral un-mixing and uptake quantification were done using pure BPD and pure FKR standard curves. Average BPD signal from each organ was plotted against the appropriate standard curve to determine %ID uptake for each sample using ImageJ software.

Photoimmunotherapy was initiated two weeks after cancer cell implantation, when tumors reached approximately 200 ± 20 mm3 in volume. Mice were randomized into groups that received (i) no-treatment, (ii) nanoparticle + laser (NP + hv), (iii) PIC + laser (PIC + hv), (iv) PIC-NP + laser (PIC-NP + hv). The BPD concentration for PIC and PIC-NP were fixed (0.25 mg/kg). To initiate PIT at 24 hours after injection, tumors were irradiated with NIR light using a 690 nm diode laser (High Power Devices), delivered at an irradiance of 100 mW/cm2 to achieve a fluence of 40 J/cm2. Tumor size was record using calipers and tumor volume estimated using the formulation V = (L × W × H) π/6, where V is tumor volume, W is tumor width, L is tumor length, and H is tumor height.

Statistical analyses:

Results are mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical tests were carried out using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). All experiments were carried out at least in triplicate. Specific tests and number of repeats are indicated in the figure captions. Investigators were blinded to experimental groups during tumor volume monitoring unless noted otherwise.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This TEM work was conducted with support from the Photopathology Center of the Wellman Center for Photomedicine, Massachusetts General Hospital. The authors thank Mr. Joseph Yim for help with experimental repeats as a part of his training at MGH. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01CA084203 (T.H.), K99CA194269 (H.H.), and R00CA194269 (H.H.).

Funding Sources

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01CA084203 (T.H.), K99CA194269 (H.H.), and R00CA194269 (H.H.)

ABBREVIATIONS

- 1O2

Singlet oxygen

- ADC

Antibody-drug conjugate

- BPD

Benzoporphyrin derivative

- Cet

Cetuximab

- CMA

Chlorin e6-monoethylenediamine monoamide

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- EGFR

Epidermal growth factor receptor

- Em

Emission

- EOC

Epithelial ovarian cancer

- EPR

Enhanced permeability and retention

- Ex

Excitation

- GBM

Glioblastoma

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- IC50

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- mAb

Monoclonal antibody

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

- NP

Nanoparticle

- OVCAR-5

Human ovarian cancer cell line

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PdI

Polydispersity index PEG, Polyethylene glycol

- PIC

Photoimmunoconjugate

- PIT

Photoimmunotherapy

- PLGA

Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)

- RES

Reticuloendothelial system

- RIC

Radio-immunoconjugates

- SEM

Standard error of the mean

- SOSG

Singlet oxygen sensor green

- U87

Human glioblastoma cell line

REFERENCES

- 1.Beck A; Goetsch L; Dumontet C; Corvaia N, Nature reviews. Drug discovery 2017, 16 (5), 315–337. DOI 10.1038/nrd.2016.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitsunaga M; Ogawa M; Kosaka N; Rosenblum LT; Choyke PL; Kobayashi H, Nature medicine 2011, 17 (12), 1685–91. DOI 10.1038/nm.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Dam GM; Themelis G; Crane LM; Harlaar NJ; Pleijhuis RG; Kelder W; Sarantopoulos A; de Jong JS; Arts HJ; van der Zee AG; Bart J; Low PS; Ntziachristos V, Nature medicine 2011, 17 (10), 1315–9. DOI 10.1038/nm.2472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dongen GA; Visser GW; Vrouenraets MB, Advanced drug delivery reviews 2004, 56 (1), 31–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen QT; Tsien RY, Nature Reviews Cancer 2013, 13, 653 DOI 10.1038/nrc3566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spring BQ; Abu-Yousif AO; Palanisami A; Rizvi I; Zheng X; Mai Z; Anbil S; Sears RB; Mensah LB; Goldschmidt R; Erdem SS; Oliva E; Hasan T, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111 (10), E933–E942. DOI 10.1073/pnas.1319493111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Lancet 1913, 182 (4694), 445–451. DOI 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)38705-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mew D; Wat CK; Towers GH; Levy JG, The Journal of Immunology 1983, 130 (3), 1473–1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oseroff AR; Ohuoha D; Hasan T; Bommer JC; Yarmush ML, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1986, 83 (22), 8744–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goff BA; Bamberg M; Hasan T, Cancer Res 1991, 51 (18), 4762–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duska LR; Hamblin MR; Miller JL; Hasan T, JNatl Cancer Inst 1999, 91 (18), 1557–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soukos NS; Hamblin MR; Keel S; Fabian RL; Deutsch TF; Hasan T, Cancer Res 2001, 61 (11), 4490–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasan T; Lin A; Yarmush D; Oseroff A; Yarmush M, Journal of Controlled Release 1989, 10 (1), 107–117. DOI 10.1016/0168-3659(89)90022-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt S; Wagner U; Oehr P; Krebs D, Zentralblattfur Gynakologie 1992, 114 (6), 307–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogata F; Nagaya T; Nakamura Y; Sato K; Okuyama S; Maruoka Y; Choyke PL; Kobayashi H, Oncotarget 2017, 8 (21), 35069–35075. DOI 10.18632/oncotarget.17047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epenetos AA; Snook D; Durbin H; Johnson PM; Taylor-Papadimitriou J, Cancer Res 1986, 46 (6), 3183–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savellano MD; Hasan T, Photochem Photobiol 2003, 77 (4), 431–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savellano MD; Hasan T, Clin Cancer Res 2005, 11 (4), 1658–68. DOI 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1902.11/4/1658 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abu-Yousif AO; Moor AC; Zheng X; Savellano MD; Yu W; Selbo PK; Hasan T, Cancer Lett 2012, 321 (2), 120–7. DOI 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.del Carmen MG; Rizvi I; Chang Y; Moor AC; Oliva E; Sherwood M; Pogue B; Hasan T, J Natl Cancer Inst 2005, 97 (20), 1516–24. DOI 10.1093/jnci/dji314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chauhan VP; Jain RK, Nature materials 2013, 12 (11), 958–62. DOI 10.1038/nmat3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang HC; Mallidi S; Liu J; Chiang CT; Mai Z; Goldschmidt R; Ebrahim-Zadeh N; Rizvi I; Hasan T, Cancer Res 2016, 76 (5), 1066–77. DOI 10.1158/0008-5472.can-. 15-0391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Son S; Lee WR; Joung YK; Kwon MH; Kim YS; Park KD, International journal of pharmaceutics 2009, 368 (1–2), 178–85. DOI 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2008.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huggett MT; Jermyn M; Gillams A; Illing R; Mosse S; Novelli M; Kent E; Bown SG; Hasan T; Pogue BW; Pereira SP, Br J Cancer 2014, 110 (7), 1698–704. DOI 10.1038/bjc.2014.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnamurthy S; Powers SK; Witmer P; Brown T, Lasers SurgMed 2000, 27 (3), 224–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.