Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membrane-derived vesicles that mediate intercellular communications. As professional phagocytes, neutrophils also produce EVs in response to various inflammatory stimuli during inflammatory processes. Neutrophil-derived EVs can be categorized into 2 subtypes according to the mechanism of generation. Neutrophil-derived trails (NDTRs) are generated from migrating neutrophils. The uropods of neutrophils are elongated by adhesion to endothelial cells, and small parts of the uropods are detached, leaving submicrometer-sized NDTRs. Neutrophil-derived microvesicles (NDMVs) are generated from neutrophils which arrived at the inflammatory foci. Membrane blebbing occurs in response to various stimuli at the inflammatory foci, and small parts of the blebs are detached from the neutrophils, leaving NDMVs. These 2 subtypes of neutrophil-derived EVs share common features such as membrane components, receptors, and ligands. However, there are substantial differences between these 2 neutrophil-derived EVs. NDTRs exert pro-inflammatory functions by guiding subsequent immune cells through the inflammatory foci. On the other hand, NDMVs exert anti-inflammatory functions by limiting the excessive immune responses of nearby cells. This review outlines the current understanding of the different subtypes of neutrophil-derived EVs and provides insights into the clinical relevance of neutrophil-derived EVs.

Keywords: Neutrophil, Extracellular vesicle, Neutrophil-derived trail, Neutrophil-derived microvesicle

INTRODUCTION

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membrane-derived vesicles limited by phospholipid bilayers (1,2). EVs include vesicles of different sizes from the smallest exosomes to the largest apoptotic bodies (3). They express various receptors and ligands from source cells, hence interacting with target cells through these molecules (2). As they harbor various cargos such as proteins, mRNAs, and miRNAs (4) derived from source cells, they are considered to be important mediators of intercellular communications. Neutrophils are professional phagocytes that play important roles in the host defense against invading pathogens. Neutrophils also generate EVs in response to immunological stimuli during the inflammatory process. Neutrophil-derived EVs were first identified by Stein and Luzio (5) and are also known as ectosomes (6,7,8,9,10), microparticles (11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23), or microvesicles (24,25,26). These neutrophil-derived EVs share common features of general EVs, such as physical characteristics, membrane components, and mechanism of generation. Recently, another type of neutrophil-derived EVs, trails, was identified (27). This specialized type of neutrophil EVs does not share a common mechanism of generation and mediates the pro-inflammatory functions of neutrophils. Here, we will review the current understandings of the different types of neutrophil-derived EVs; the classical neutrophil-derived microvesicles (NDMVs) and the alternative neutrophil-derived trails (NDTRs) (Fig. 1).

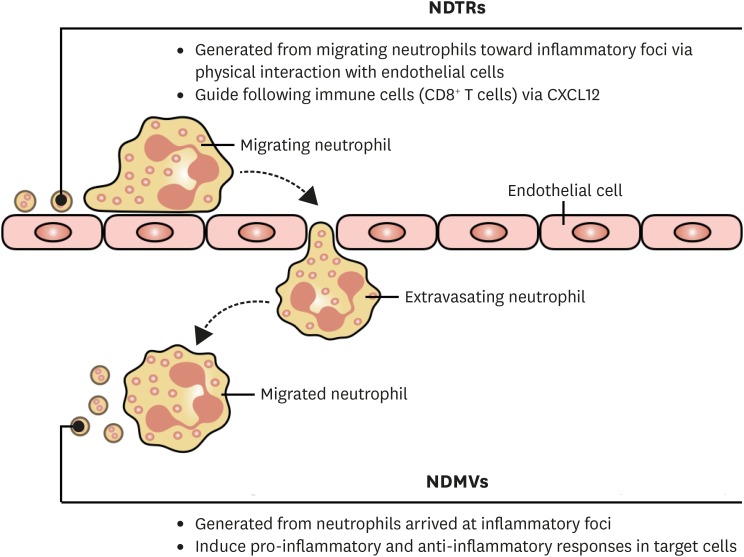

Figure 1. Overview of the subtypes of neutrophil-derived EVs. NDTRs are generated from neutrophil migrating toward the inflammatory foci. The physical interactions between neutrophils and endothelial cells induce the uropod elongation, and the elongated uropod is detached from neutrophils, leaving NDTRs. The primary function of NDTRs is to guide subsequent immune cells through the inflammatory foci. NDMVs are generated from neutrophils at the inflammatory foci. After extravasation, neutrophils produce substantial amounts of NDMVs. NDMVs provide host defense against pathogens through direct bactericidal activity and also inhibit the pro-inflammatory responses of other immune cells. Furthermore, NDMVs limit the excessive inflammatory responses of nearby cells by enhancing anti-inflammatory genes and cytokines.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF NDMVs

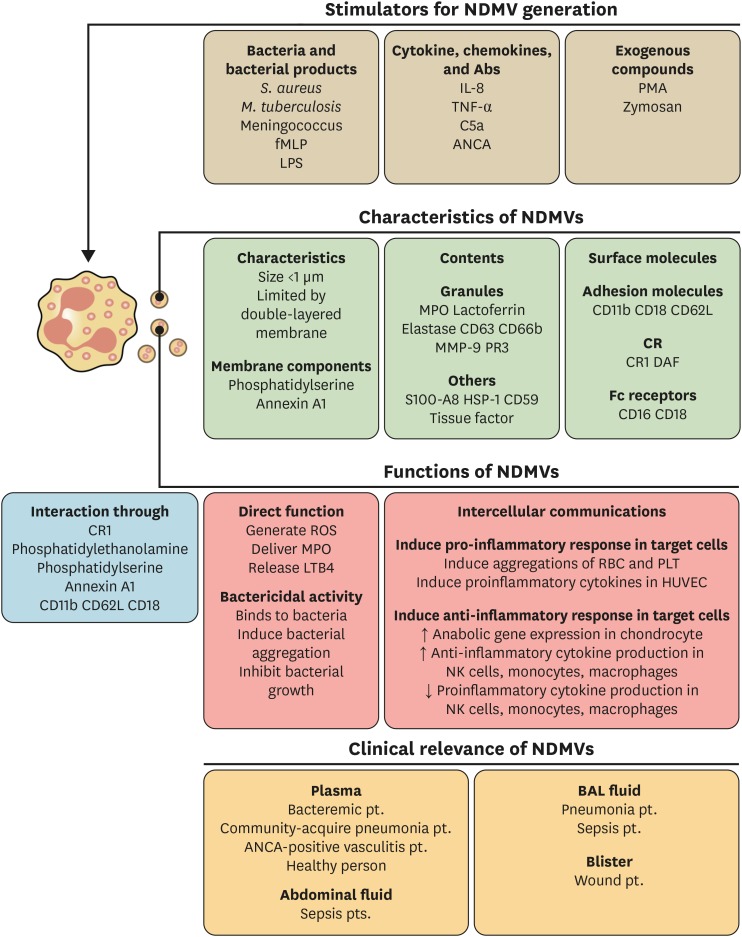

NDMVs are the classical type of neutrophil-derived EVs according to the general classification of EVs (2) (Fig. 2). The size of NDMVs is less than 1 μm as demonstrated by electron microscopic analysis (6,10,18) and flow cytometry analysis (9,11,13,16,19,22,25,28). Electron microscopic analysis has revealed that NDMVs are limited by double membranes (6,9,18). They express general markers of EVs, such as phosphatidylserine (5,7,8,11,13,16,17,18,21,26,29) and annexin A1 (21,25,28). As NDMVs are derived from neutrophil membranes, they also express neutrophil-derived receptors. NDMVs express the adhesion molecules such as CD11b (10,14,16,19,22,28), CD18 (28), and CD62L (10,18,21) and also express Fc receptors (10,14,19). The complement receptors (CRs), CR1 and CD55, are also found in NDMVs (6,10,12). Interestingly, NDMVs express granule-associated markers such as CD63 (6) and CD66b (10,12,18,19,20,22,25,28). Furthermore, protein analysis has revealed the presence of granule proteins such as myeloperoxidase (6,10,13,16,18,19,28), lactoferrin (15,28), elastase (6,10), matrix metallopeptidase 9 (10,28), and proteinase 3 (10,19) in NDMVs. Heat shock protein (HSP)-1 and S100 calcium-binding protein A8 are also found in NDMVs (28).

Figure 2. Characteristics of NDMVs. NDMVs are generated by various stimulants such as bacteria, bacterial products, cytokines, chemokines, and exogenous compounds. NDMVs are small-sized EVs (less than 1 μm) consisting of various membrane components from neutrophils. NDMVs exert direct bactericidal activity and mediate intercellular communications. The interactions with target cells are mediated by membrane components. NDMVs are found in various diseases such as sepsis, bacterial infection, pneumonia, and vasculitis.

STIMULANTS FOR NDMVs GENERATION

Neutrophils generate NDMVs either spontaneously (12,15,19) or in response to various stimulants. The stimulants for NDMVs generation can be classified into 3 major categories (Fig. 2). Bacteria and bacterial products are major stimulants for NDMVs generation. NDMVs are generated from neutrophils exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (9), Staphylococcus aureus (26), and meningococcal bacteria (20). They are also produced in response to bacterial derived products such as formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLP) (6,7,8,11,15,21,23,28,30) and LPS (14). NDMVs can be generated by cytokines and chemokines such as IL-8 (11,15,25) and TNF-α (25,26). Complement component C5a (5,11), anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) (13,19), and nitric oxide (17) induce NDMVs formation. Experimentally, NDMVs are produced by the activation of protein kinase C with PMA (6,14,16,23,25,26) and zymosan stimulation (11). These studies suggest that NDMVs are easily generated from neutrophils during immune responses, demonstrating the important role of NDMVs in the effector functions of neutrophils.

FUNCTIONS OF NDMVs

Generally, EVs are involved in intercellular communications by delivering signaling molecules to target cells. Although NDMVs mediate intercellular communications, they can modulate immune functions directly. NDMVs generated by bacterial stimulation can inhibit the growth of bacteria by inducing aggregation (26). They directly generate ROS in response to stimulation with fMLP (28), nitric oxide (17), Ca2+ ionophore, and PMA (18). NDMVs also generate leukotriene B4 in response to arachidonic acid and Ca2+ ionophore (28). Moreover, they deliver granule proteins to target cells (16). These findings indicate that NDMVs could function as mobile functional units of neutrophils rather than just signaling mediators.

NDMVs can modulate the inflammatory responses of target cells (Fig. 2). They mediate either pro-inflammatory responses or anti-inflammatory responses according to the target cells. NDMVs induce the aggregation of RBCs by binding to them via CR1 (12) or integrin (14). They also adhere to endothelial cells (10) and enhance the expressions of pro-inflammatory genes and molecules such as IL-6, IL-8, tissue factor, and ROS (15,19). On the other hand, they protect the cartilage by reducing pro-inflammatory mediators (25). NDMVs inhibit the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhance the anti-inflammatory cytokine, TGF-β, in NK cells (11). In addition, the maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MoDCs) is inhibited by NDMVs (30). Further NDMV-exposed MoDCs showed the decreased phagocytic activity and pro-inflammatory cytokine generation with the increased expression of anti-inflammatory cytokine, TGF-β (30). NDMVs also modulate the functions of macrophages. In NDMV-exposed macrophages, the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10) is decreased, and the production of TGF-β is increased (7,29). Moreover, NDMVs inhibit the recruitment of neutrophils following IL-1β stimulation (21). These findings indicate that NDMVs primarily mediate the anti-inflammatory responses of target cells despite of their effects on RBCs and endothelial cells. TGF-β, the one of the most important anti-inflammatory cytokines, is consistently increased in NDMV-exposed cells including chondrocytes, NK cells, monocytes, and macrophages. Furthermore, the pro-inflammatory cytokines are markedly attenuated in almost all cells exposed to NDMVs. Considering that NDMVs are generated from neutrophils at the inflammatory foci, neutrophils may utilize NDMVs to limit excessive inflammatory responses for preventing possible harmful effects.

NDMVs can mediate intercellular communications via cell surface molecules. CR1 mediate the binding of NDMVs to RBCs (12) and bacteria (6). Membrane phospholipids, such as phosphatidylethanolamine (30) and phosphatidylserine (7), are responsible for interactions with monocytes. Annexin A1 mediates the binding of NDMVs to formyl peptide receptor 2 in chondrocytes (25). The integrins are also important for NDMVs to communicate with target cells. CD11b is responsible for the binding of NDMVs to epithelial cells (16), and CD18 is responsible for the binding of NDMVs to endothelial cells (19).

CLINICAL RELEVANCE OF NDMVs

NDMVs are clinically relevant in various inflammatory diseases (Fig. 2). NDMVs are found in the plasma of healthy individuals (15,28) and bacteremic patients (20,26). They are also found in the plasma of patients with community-acquired of pneumonia patients (28) and those with ANCA positive vasculitis patients (13,19). Furthermore, NDMVs are also found in the body fluids of patients with inflammatory diseases. The bronchoalveolar fluids of patients with pneumonia (6) and sepsis (22) contain NDMVs. NDMVs are present in the blisters of wound patients (6,28) and abdominal fluids if septic patients (22).

CHARACTERISTICS OF NDTRs

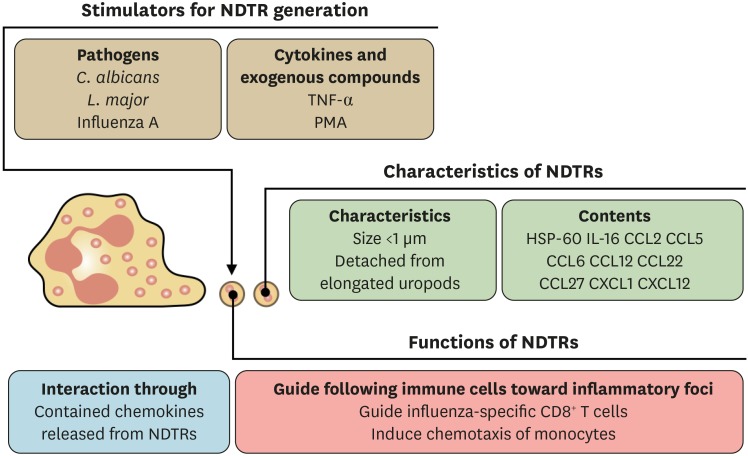

NDTRs are the another type of neutrophil-derived EVs (Fig. 3). They are generated from neutrophils during extravasation from blood vessels into the inflammatory foci (27,31). The extravasating neutrophils bind to endothelial cells via integrins (32); hence, the physical forces of adhesion molecules elongate the uropod (rear portion of cells) of migrating neutrophils (31). When the forces of migrating neutrophils exceed the physical forces of adhesion molecules, the small cytoplasmic parts of the neutrophils are detached (31), leaving NDTRs on the endothelial cells (27). As the detached NDTRs contain various chemokines including CXCL12, subsequent immune cells are guided following the tracks of neutrophil migration (27). In contrast to NDMVs, the characteristics of NDTRs have not been fully understood. The identified stimulants for NDTR generation are pathogens. Intravital microscopy has revealed the presence of NDTRs in the peripheral vessels of mice infected with Leishmania major and Candida albicans (31). They are also found in the airways of influenza-infected mice (27). In experimental settings, neutrophils can generate NDTRs in response to TNF-α (27,31) and PMA stimulations (27). The physical characteristics of NDTRs seems to be similar to those of NDMVs. The size of NDTRs is less than 1 μm (31), and they express CD18 integrins (27,31). Chemokine arrays have revealed that NDTRs contain various chemokines such as IL-16, CCL2, CCL5, CCL6, CCL12, CCL22, CCL27, CXCL1, and CXCL12 (27). Interestingly, a substantial amount of HSP-60 has been found in the NDTRs on microarray (27). The primary function of NDTRs is to guide immune cells through the inflammatory foci (27). As NDTRs contain various chemokines, the chemokines are thought to be slowly released into the surrounding tissues. As a result, these chemokines provide cues for the migration of immune cells CD8+ T cells (27). However, the role of NDTRs in inducing functional changes in subsequent immune cells has not been clarified.

Figure 3.

Characteristics of NDTRs. NDTRs are generated by pathogens, cytokines, and exogenous compounds. NDTRs are also small-sized EVs (less than 1 μm) and contain neutrophil-derived chemokines. The primary function of NDTRs is to guide subsequent immune cells through the inflammatory foci, and this is mediated by the chemokines in NDTRs.

SIMILARITIES AND DIFFERENCES BETWEEN NDTRs AND NDMVs

NDTRs and NDMVs share common characteristics. They are submicrometer-sized EVs derived from neutrophils; hence, they express neutrophil-specific molecules. Although the mechanism of generation is slightly different, they are derived from the plasma membranes of neutrophils and contain various molecules from neutrophils. However, the greatest difference between these 2 neutrophil-derived EVs seems to be the spatiotemporal difference in generation. NDTRs are generated from neutrophils migrating toward the inflammatory foci, whereas NDMVs are generated from neutrophils already at the inflammatory foci. Considering that neutrophils are not only the first responder to inflammation but also the final responder, NDTRs and NDMVs might have different roles in the inflammatory process (pro-inflammatory NDTRs vs. anti-inflammatory NDMVs). These findings indicate that neutrophils respond to various inflammatory environments by forming different types of EVs. However, the functional differences between NDTRs and NDMVs remain unclear. In addition, it is unclear whether NDTRs induce the effector functions of immune cells. As most immune cells are prepared for upcoming inflammatory insults as they migrate toward the inflammatory foci, NDTRs might be involved in the priming process. The direct bactericidal activity of NDTRs should also be investigated to determine whether they provide minimal levels of host defense against invading pathogens. Moreover, the relevance of pro-inflammatory NDTRs and anti-inflammatory NDMVs should be identified in clinical diseases.

CONCLUSION

The International Society on the Extracellular Vesicles introduced the single term ‘EV’ as an umbrella term of all types of vesicles derived from prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (2). However, recent advances in understanding EVs revealed the heterogeneity of EVs (33,34,35). In line with this consensus, NDTRs could be classified as a subtype of neutrophil-derived EVs. NDTRs have unique characteristics which can be discriminated from conventional neutrophil-derived EVs. The generation of NDTRs is entirely dependent on the physical forces by adhesion molecules. Considering the fact that the generation of EVs generally depend on the membrane blebbing without external forces, this characteristic is unique for NDTRs. Moreover, the functional characteristics NDTRs provide a strong evidence for classifying NDTRs as a distinct subtype of neutrophil-derived EVs. As described earlier, NDTRs are involved in the protection against influenza infection (27). They are generated during influenza infection and guide following immune cells into the inflammatory foci. On the other hand, NDMVs have protective effects in inflammatory and rheumatoid arthritis by inhibiting inflammatory activation of macrophages (24,25).

Although various studies have attempted to develop a delivery system using cell-derived EVs, there are still limitations on the cellular source of EVs and the amount of EVs generated. Cancer cell-derived EVs are widely used for drug delivery; however, they have potentially harmful effects such as tumor progression, metastasis, and cancer-related coagulopathy (36,37). Moreover, several days are required for the generation of EVs from cancer cells (38,39,40,41). On the other hand, neutrophil-derived EVs have great advantages as drug-delivery vehicles. Neutrophils readily generate large amounts of EVs in response to external stimulation and are easy to handle because of their short life span. Moreover, neutrophil-derived EVs contain neutrophil-derived molecules such as granules; hence, they might provide the minimal defense against pathogens during drug delivery. Further studies are needed to understand the different functions of neutrophil-derived EVs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by 2017R1C1B2009015 and 2017R1A4A1015652 from National Research Foundation of Korea.

Abbreviations

- ANCA

anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- CR

complement receptor

- EV

extracellular vesicle

- fMLP

formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine

- HSP

heat shock protein

- MoDC

monocyte-derived dendritic cell

- NDMV

neutrophil-derived microvesicle

- NDTR

neutrophil-derived trail

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The author declares no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Théry C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Pol E, Böing AN, Gool EL, Nieuwland R. Recent developments in the nomenclature, presence, isolation, detection and clinical impact of extracellular vesicles. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14:48–56. doi: 10.1111/jth.13190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.György B, Szabó TG, Pásztói M, Pál Z, Misják P, Aradi B, László V, Pállinger E, Pap E, Kittel A, et al. Membrane vesicles, current state-of-the-art: emerging role of extracellular vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:2667–2688. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0689-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loyer X, Vion AC, Tedgui A, Boulanger CM. Microvesicles as cell-cell messengers in cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2014;114:345–353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.113.300858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein JM, Luzio JP. Ectocytosis caused by sublytic autologous complement attack on human neutrophils. The sorting of endogenous plasma-membrane proteins and lipids into shed vesicles. Biochem J. 1991;274:381–386. doi: 10.1042/bj2740381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hess C, Sadallah S, Hefti A, Landmann R, Schifferli JA. Ectosomes released by human neutrophils are specialized functional units. J Immunol. 1999;163:4564–4573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eken C, Sadallah S, Martin PJ, Treves S, Schifferli JA. Ectosomes of polymorphonuclear neutrophils activate multiple signaling pathways in macrophages. Immunobiology. 2013;218:382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eken C, Martin PJ, Sadallah S, Treves S, Schaller M, Schifferli JA. Ectosomes released by polymorphonuclear neutrophils induce a MerTK-dependent anti-inflammatory pathway in macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39914–39921. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duarte TA, Noronha-Dutra AA, Nery JS, Ribeiro SB, Pitanga TN, Lapa E Silva JR, Arruda S, Boéchat N. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-induced neutrophil ectosomes decrease macrophage activation. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2012;92:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasser O, Hess C, Miot S, Deon C, Sanchez JC, Schifferli JA. Characterisation and properties of ectosomes released by human polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Exp Cell Res. 2003;285:243–257. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pliyev BK, Kalintseva MV, Abdulaeva SV, Yarygin KN, Savchenko VG. Neutrophil microparticles modulate cytokine production by natural killer cells. Cytokine. 2014;65:126–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasser O, Schifferli JA. Microparticles released by human neutrophils adhere to erythrocytes in the presence of complement. Exp Cell Res. 2005;307:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kambas K, Chrysanthopoulou A, Vassilopoulos D, Apostolidou E, Skendros P, Girod A, Arelaki S, Froudarakis M, Nakopoulou L, Giatromanolaki A, et al. Tissue factor expression in neutrophil extracellular traps and neutrophil derived microparticles in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis may promote thromboinflammation and the thrombophilic state associated with the disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1854–1863. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pluskota E, Woody NM, Szpak D, Ballantyne CM, Soloviev DA, Simon DI, Plow EF. Expression, activation, and function of integrin alphaMbeta2 (Mac-1) on neutrophil-derived microparticles. Blood. 2008;112:2327–2335. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-127183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesri M, Altieri DC. Leukocyte microparticles stimulate endothelial cell cytokine release and tissue factor induction in a JNK1 signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23111–23118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slater TW, Finkielsztein A, Mascarenhas LA, Mehl LC, Butin-Israeli V, Sumagin R. Neutrophil microparticles deliver active myeloperoxidase to injured mucosa to inhibit epithelial wound healing. J Immunol. 2017;198:2886–2897. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nolan S, Dixon R, Norman K, Hellewell P, Ridger V. Nitric oxide regulates neutrophil migration through microparticle formation. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:265–273. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitanga TN, de Aragão França L, Rocha VC, Meirelles T, Borges VM, Gonçalves MS, Pontes-de-Carvalho LC, Noronha-Dutra AA, dos-Santos WL. Neutrophil-derived microparticles induce myeloperoxidase-mediated damage of vascular endothelial cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2014;15:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-15-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong Y, Eleftheriou D, Hussain AA, Price-Kuehne FE, Savage CO, Jayne D, Little MA, Salama AD, Klein NJ, Brogan PA. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies stimulate release of neutrophil microparticles. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:49–62. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011030298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nieuwland R, Berckmans RJ, McGregor S, Böing AN, Romijn FP, Westendorp RG, Hack CE, Sturk A. Cellular origin and procoagulant properties of microparticles in meningococcal sepsis. Blood. 2000;95:930–935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dalli J, Norling LV, Renshaw D, Cooper D, Leung KY, Perretti M. Annexin 1 mediates the rapid anti-inflammatory effects of neutrophil-derived microparticles. Blood. 2008;112:2512–2519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-140533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prakash PS, Caldwell CC, Lentsch AB, Pritts TA, Robinson BR. Human microparticles generated during sepsis in patients with critical illness are neutrophil-derived and modulate the immune response. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;73:401–406. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31825a776d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mesri M, Altieri DC. Endothelial cell activation by leukocyte microparticles. J Immunol. 1998;161:4382–4387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhys HI, Dell'Accio F, Pitzalis C, Moore A, Norling LV, Perretti M. Neutrophil microvesicles from healthy control and rheumatoid arthritis patients prevent the inflammatory activation of macrophages. EBioMedicine. 2018;29:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Headland SE, Jones HR, Norling LV, Kim A, Souza PR, Corsiero E, Gil CD, Nerviani A, Dell'Accio F, Pitzalis C, et al. Neutrophil-derived microvesicles enter cartilage and protect the joint in inflammatory arthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:315ra190. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac5608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Timár CI, Lorincz AM, Csépányi-Kömi R, Vályi-Nagy A, Nagy G, Buzás EI, Iványi Z, Kittel A, Powell DW, McLeish KR, et al. Antibacterial effect of microvesicles released from human neutrophilic granulocytes. Blood. 2013;121:510–518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-431114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lim K, Hyun YM, Lambert-Emo K, Capece T, Bae S, Miller R, Topham DJ, Kim M. Neutrophil trails guide influenza-specific CD8+ T cells in the airways. Science. 2015;349:aaa4352. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalli J, Montero-Melendez T, Norling LV, Yin X, Hinds C, Haskard D, Mayr M, Perretti M. Heterogeneity in neutrophil microparticles reveals distinct proteome and functional properties. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:2205–2219. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.028589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gasser O, Schifferli JA. Activated polymorphonuclear neutrophils disseminate anti-inflammatory microparticles by ectocytosis. Blood. 2004;104:2543–2548. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eken C, Gasser O, Zenhaeusern G, Oehri I, Hess C, Schifferli JA. Polymorphonuclear neutrophil-derived ectosomes interfere with the maturation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:817–824. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hyun YM, Sumagin R, Sarangi PP, Lomakina E, Overstreet MG, Baker CM, Fowell DJ, Waugh RE, Sarelius IH, Kim M. Uropod elongation is a common final step in leukocyte extravasation through inflamed vessels. J Exp Med. 2012;209:1349–1362. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nauseef WM, Borregaard N. Neutrophils at work. Nat Immunol. 2014;15:602–611. doi: 10.1038/ni.2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kowal J, Arras G, Colombo M, Jouve M, Morath JP, Primdal-Bengtson B, Dingli F, Loew D, Tkach M, Théry C. Proteomic comparison defines novel markers to characterize heterogeneous populations of extracellular vesicle subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E968–E977. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521230113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tkach M, Kowal J, Théry C. Why the need and how to approach the functional diversity of extracellular vesicles. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018;373:20160479. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2016.0479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tucher C, Bode K, Schiller P, Claßen L, Birr C, Souto-Carneiro MM, Blank N, Lorenz HM, Schiller M. Extracellular vesicle subtypes released from activated or apoptotic T-lymphocytes carry a specific and stimulus-dependent protein cargo. Front Immunol. 2018;9:534. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bang OY, Chung JW, Lee MJ, Kim SJ, Cho YH, Kim GM, Chung CS, Lee KH, Ahn MJ, Moon GJ. Cancer cell-derived extracellular vesicles are associated with coagulopathy causing ischemic stroke via tissue factor-independent way: the OASIS-CANCER study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159170. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bebelman MP, Smit MJ, Pegtel DM, Baglio SR. Biogenesis and function of extracellular vesicles in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;188:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim MS, Haney MJ, Zhao Y, Mahajan V, Deygen I, Klyachko NL, Inskoe E, Piroyan A, Sokolsky M, Okolie O, et al. Development of exosome-encapsulated paclitaxel to overcome MDR in cancer cells. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2016;12:655–664. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2015.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akao Y, Iio A, Itoh T, Noguchi S, Itoh Y, Ohtsuki Y, Naoe T. Microvesicle-mediated RNA molecule delivery system using monocytes/macrophages. Mol Ther. 2011;19:395–399. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skog J, Würdinger T, van Rijn S, Meijer DH, Gainche L, Sena-Esteves M, Curry WT, Jr, Carter BS, Krichevsky AM, Breakefield XO. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1470–1476. doi: 10.1038/ncb1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silva AK, Luciani N, Gazeau F, Aubertin K, Bonneau S, Chauvierre C, Letourneur D, Wilhelm C. Combining magnetic nanoparticles with cell derived microvesicles for drug loading and targeting. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2015;11:645–655. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]