Abstract

In 2017, studies of cellular metabolism broadly permeated immunological research. Accumulating data support the view that understanding how metabolism regulates immune cell function could provide new therapeutic opportunities for the many diseases associated with immune system dysregulation.

With the growing realization that metabolism shapes the functions and differentiation of immune cells, 2017 saw the study of cellular metabolism emerge into many aspects of immunology, where it has shed light on how immune cells respond to and influence their environment. We highlight four papers from the past year, and discuss how they contribute to the ways in which we think about immune cell function and the roles of immunometabolism in disease development and therapy.

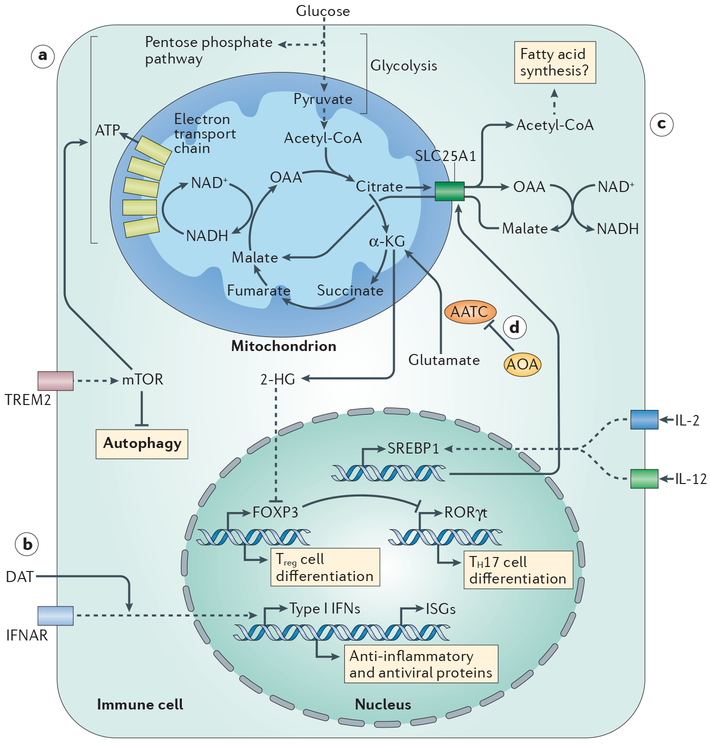

The first paper, by Marco Colonna and colleagues1, addresses the role of microglia, the resident macrophages of the central nervous system, in late-onset Alzheimer disease. Variants of triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2), which is a microglial surface receptor for apoptotic cells, phospholipids and lipoproteins, are associated with increased risk of this disease. Ulland et al. used 5XFAD mice, which develop β-amyloid plaques similar to those found in humans with Alzheimer disease, to study Trem2 function1. They found that microglia from Trem2−/− 5XFAD mice, in which β-amyloid formation is increased, are filled with autophagosomes and are more prone to apoptosis. Similarly, microglia from humans with TREM2 risk variants have increased signs of auto-phagy1. Consistent with increased autophagy, TREM2 deficiency correlated with decreased mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) signalling and decreased anabolic metabolism and overall energetic status (FIG. 1a); these defects were reversed by cyclocreatine, which sustains ATP levels during increased energy demand. Prolonged cyclocreatine treatment of Trem2−/− 5XFAD mice decreased autophagy and apoptosis of the microglia clustered around β-amyloid plaques, thereby preventing plaque spreading and preserving the function of adjacent neurons. These results suggest targeting microglial bioenergetics as a potential route for treating Alzheimer disease.

Figure 1 |. Metabolic programmes regulate immune cell function.

a | In microglia, signalling through triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) promotes activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), which balances anabolic metabolism and ATP production. b | Positive effects of the microbiota on influenza virus infection are mediated by the microbial metabolite desaminotyrosine (DAT), which potentiates signalling downstream of the type I interferon receptor (IFNAR). c | Metabolic support for natural killer (NK) cell activation by IL-2 and IL-12 is provided by induced expression of sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP1), which upregulates expression of SLC25A1. This citrate–malate shuttle enables NADH to be moved into mitochondria, where it fuels ATP production. d | (Amino-oxy)acetic acid (AOA) limits T helper 17 (TH17) cell development by inhibiting the activity of aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic (AATC), which catalyses the conversion of glutamate into α-ketoglutarate (α-KG; the precursor of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG)). 2-HG promotes the methylation and transcriptional inactivation of Foxp3. OAA, oxaloacetic acid.

The second paper, by Thaddeus Stappenbeck and colleagues2, describes how a microbiota-derived metabolite affects macrophages. Much of the morbidity associated with influenza virus infection is immunopathological, which indicates that both immunoregulation and control of viral replication are crucial for optimal outcome. Steed et al. showed that type I interferons (IFNs) have a crucial role in this regard2. Irgm1−/− mice, which have increased baseline levels of type I IFNs, have reduced mortality after influenza virus infection, which is associated with decreased levels of inflammatory cytokines, viral transcripts and airway epithelial damage. These effects were reversed by type I IFN receptor (IFNAR) blockade. Based on prior work3, the authors reasoned that the beneficial effects of the microbiota on influenza outcome (inferred from the negative impact of antibiotics) might reflect type I IFN induction by microbiota-derived products. They screened a library of microbiota metabolites for the induction of type I IFN production and expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), from which they identified desaminotyrosine, a breakdown product of dietary flavonoids (FIG. 1b). The administration of desaminotyrosine to antibiotic-treated mice induced ISG expression and protected them from severe influenza through a macrophage-dependent process2. These results add to earlier studies linking poor outcome of influenza virus infection with antibiotic treatment4. It is likely that we will hear more about the between-and within-species effects of metabolites on immune cell function in the near future.

The third paper, by David Finlay and colleagues5, focuses on the relevance of enhanced glycolysis in natural killer (NK) cells stimulated with IL-2 and IL-12 (REF. 6), which drive proliferation and IFNγ production. They found that IL-2 and IL-12 promote the expression of Srebp1, which encodes a transcription factor that controls the expression of genes involved in fatty acid synthesis, and reasoned that glucose carbon is incorporated into citrate for lipid synthesis to support the process of NK cell activation. However, inhibiting lipid synthesis had no effect on NK cell activation, which suggests that SREBP1 (sterol regulatory element binding protein 1) has another unanticipated function in metabolic reprogramming. The lipid synthesis pathway involves the export of citrate from mitochondria into the cytoplasm, and its conversion into acetyl-CoA. Citrate export is coupled to malate import into mitochondria, via SLC25A1, which allows cytoplasmic NADH-reducing equivalents to be transferred into mitochondria to fuel the electron transport chain (FIG. 1c). The role for SREBP1 in NK cell activation turned out to be linked to the induction of Slc25a1 expression6. Thus, NK cell activation is supported by an integrated metabolic response whereby increased glycolysis boosts citrate levels which facilitate both lipid synthesis and increased respiration.

T cell activation is driven by ligation of the T cell receptor and co-stimulatory receptors, but environmental cytokines can promote different cell fates. In the fourth paper, Chen Dong, Edward Driggers, Sheng Ding and colleagues7 screened 10,000 small molecules for activity that favours the emergence of regulatory T (Treg) cells in T helper 17 (TH17) cell-inducing culture conditions and identified (amino-oxy)acetic acid (AOA). They found that AOA inhibits aspartate aminotransferase, cytoplasmic (AATC; also known as GOT1) (FIG. 1d), the main function of which is to convert glutamate into α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)7. The level of 2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), a product of α-KG, is increased in TH17 cells compared with Treg cells. The addition of cell-permeable α-KG or 2-HG to T cell cultures countered the ability of AOA to favour Treg cell differentiation over TH17 cell differentiation. A major effect of 2-HG is to suppress expression of Foxp3, which encodes the transcription factor that orchestrates Treg cell development. Foxp3 expression depends on demethylation; this is regulated by the α-KG-dependent TET1–TET3 enzymes, which are antagonized by 2-HG. Exogenous 2-HG increased methylation of Foxp3 in both TH17 and Treg cells. TET1- and TET2-deficient T cells also have increased Foxp3 methylation and can develop into TH17 cells in Treg cell-inducing culture conditions. By contrast, AOA treatment resulted in reduced methylation of the Foxp3 locus. These data indicate that α-KG and 2-HG are important for determining T cell fate along the TH17–Treg cell axis by epigenetically regulating Foxp3 expression. Strikingly, targeting AATC ameliorated the development of a mouse model of multiple sclerosis in which TH17 cells are pathogenic.

Together, these four papers emphasize our growing understanding that immune cells can undergo complex changes in metabolism to support their functional plasticity8,9. Indeed, immune cells provide a dynamic experimental system in which to study induced metabolic reprogramming and its link to changing cellular function. New advances discussed here highlight how metabolic pathways can be manipulated to promote or inhibit immune cell function or differentiation, which may inform the identification of new therapeutic opportunities for disease states in which immune dysfunction is now known to have a causative role.

Key advances.

Signalling through microglial triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) promotes mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)-driven metabolic reprogramming that is important for microglia to sequester β-amyloid plaques during Alzheimer disease1.

Desaminotyrosine, a metabolite produced by enteric bacteria of the microbiota, supports successful immunity against influenza virus infection by promoting the expression of interferon- stimulated genes2.

The citrate–malate shuttle, rather than the Krebs cycle, provides NADH for the electron transport chain and oxidative phosphorylation in activated natural killer cells5.

T helper 17 (TH17) cell differentiation is promoted by the conversion of glutamate-derived α-ketoglutarate into 2-hydroxyglutarate, which promotes Foxp3 methylation and silencing7.

Acknowledgements

The authors are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (to E.J.P. and E.L.P.), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (to E.J.P.) and the Max Planck Society (to E.J.P. and E.L.P.).

Footnotes

Competing interests statement

The authors declare competing interests. See online for details.

Contributor Information

Edward J. Pearce, Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics, Freiburg, Germany; Faculty of Biology, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany.

Erika L. Pearce, Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics, Freiburg, Germany.

References

- 1.Ulland TK et al. TREM2 maintains microglial metabolic fitness in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell 170, 649–663.e13 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steed AL et al. The microbial metabolite desaminotyrosine protects from influenza through type I interferon. Science 357, 498–502 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kernbauer E, Ding Y & Cadwell K An enteric virus can replace the beneficial function of commensal bacteria. Nature 516, 94–98 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ichinohe T et al. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5354–5359 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assmann N et al. Srebp-controlled glucose metabolism is essential for NK cell functional responses. Nat. Immunol 18, 1197–1206 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating SE et al. Metabolic reprogramming supports IFN-γ production by CD56BRIGHT NK cells. J. Immunol 196, 2552–2560 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu T et al. Metabolic control of TH17 and induced Treg cell balance by an epigenetic mechanism. Nature 548, 228–233 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Neill LA & Pearce EJ Immunometabolism governs dendritic cell and macrophage function. J. Exp. Med 213, 15–23 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puleston DJ, Villa M & Pearce EL Ancillary activity: beyond core metabolism in immune cells. Cell Metab. 26, 131–141 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]