Abstract

Purpose

Autosomal dominant lateral temporal epilepsy (ADLTE) is a genetic focal epilepsy syndrome characterized by focal seizures with dominant auditory symptomatology. We present a case report of an 18-year-old patient with acute onset of seizures associated with epilepsy. Based on the clinical course of the disease and the results of the investigation, the diagnosis of ADLTE with a proven mutation in the RELN gene, which is considered causative, was subsequently confirmed. The aim of this study was to use 3 Tesla (3 T) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and advanced neuroimaging methods in a patient with a confirmed diagnosis of ADTLE.

Methods

3 T MRI brain scan and advanced neuroimaging methods were used in the standard protocols to analyzse voxel-based MRI, cortical thickness, and functional connectivity.

Results

Morphometric MRI analysis (blurred grey-white matter junctions, voxel-based morphometry, and cortical thickness analysis) did not provide any informative results. The functional connectivity analysis revealed higher local synchrony in the patient in the left temporal (middle temporal gyrus), left frontal (supplementary motor area, superior frontal gyrus), and left parietal (gyrus angularis, gyrus supramarginalis) regions and the cingulate (middle cingulate gyrus) as compared to healthy controls.

Conclusions

Evidence of multiple areas of functional connectivity supports the theory of epileptogenic networks in ADTLE. Further studies are needed to elucidate this theory.

Abbreviations: ADLTE, Autosomal dominant lateral temporal epilepsy; ADPEAF, Autosomal dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features; LGI1, Leucine-rich, glioma inactivated 1; RELN, Reelin; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; CT, Computer tomography; EEG, Electroencephalography; CBZ, Carbamazepine; CLB, Clobazam; 3 T, three Tesla; 1.5 T, one Tesla; TLE, Temporal Lobe Epilepsy; HDEEG, high density resting-state EEG; GMC, grey matter concentration; GMV, grey matter volume; WMC, white matter concentration; WMV, white matter volume; LS, Local synchrony

Keywords: Autosomal dominant temporal lobe epilepsy, RELN gene, 3 Tesla brain MRI, Functional connectivity, Epileptogenic networks

Highlights

-

•

A report of a reelin mutation associated with ADLTE

-

•

A discussion of the importance of brain 3 T MRI and advanced MRI methods in ADLTE

-

•

A discussion of epileptogenic networks in temporal lobe epilepsy

-

•

Increased clinical awareness of the role of multiple gene panels in diagnosing etiologically unclear epilepsy

1. Introduction

Autosomal dominant lateral temporal epilepsy (ADLTE), also known as autosomal dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features (ADPEAF), is a genetic focal epilepsy syndrome. It is characterized by focal seizures with or without a loss of consciousness, inconstantly with secondary generalization. Focal seizures are mainly characterized by auditory symptoms. Auditory auras are the most common symptom, and occur in isolation or precede some kind of receptive aphasia. Other symptoms following the auditory phenomena include vertigo, paroxysmal headache, déjà-vu, and epigastric discomfort [2]. Sensory symptomatology (e.g., visual, olfactory) and autonomic motor symptomatology are less common. Neurological findings and the mental status of patients are normal. The manifestation of the syndrome occurs between the ages of four and 50 years, with the maximal occurrence in the adolescent period [3]. Structural examinations of the brain (CT, MRI) at standard resolutions most often return normal findings. Routine and sleep electroencephalography (EEG) may be normal, but findings of focal/slow wave abnormality in the temporal areas are not uncommon, occurring in approximately 20% of patients [2], [3]. The disease heredity is autosomal dominant with varying penetration (about 70%) [1]. The diagnosis is based on personal and family history, seizure semiology, and normal MRI brain scan. Approximately 33% of patients show a pathogenic variant in the LGI1 gene [2]. In a smaller percentage of ADLTE cases, mutation in the reelin (RELN) gene is shown in heterozygous form [2]. The RELN gene is primarily expressed in brain tissue. The protein product of the RELN gene is called reelin. Reelin regulates the correct formation of laminated structures during embryonic development and postnatally modulates dendritic growth and synaptic plasticity [2]. Homozygous variants of the RELN mutation cause lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia, severe neuronal migration defects, delayed cognitive development, and epileptic seizures [5]. Heterozygous mutation of the RELN mutation can cause small changes in the cortex corresponding to neuronal migration disorders [2]. The prognosis of the disease is benign and, in most cases, there is a very good response to treatment with properly selected anti-seizure drugs (valproate, phenytoin, and carbamazepine are recommended).

2. Case report

We present a case report of an 18-year-old man who was admitted to the Department of Pediatric Neurology of the University Hospital Brno in 2017. According to his personal history, he was born in the 32nd week of gestation (the reason is unknown) and his psychomotor development was normal. The family history showed no neurological disease or epilepsy. At the age of 17, the patient suddenly began to experience epileptic seizures without clear provocation. The clinical manifestation was dominated by focal auditory seizures, without the loss of consciousness. The seizures (auras) were described as a short-term loss of hearing and simultaneous sensations of warmth lasting up to 30 s. The auras consistently progressed into focal seizures with right-handed facial-brachial motor symptomatology. Focal to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures occurred inconsistently. The seizures were daily, and the frequency at initial onset was very high. The auditory and vegetative auras occurred several times a day and convulsive seizures following auras occurred five to six times per week. On admission, the patient was already being treated with valproic acid monotherapy at a total dose of 1500mg per day with a suitable serum concentration. This medication had no significant effect. A CT and MRI (1.5 T) scan, performed at another institution, were described as normal. A routine EEG showed a non-specific finding of theta activity in the left fronto-centro-temporal region. The patient was admitted to our department urgently after a generalized tonic–clonic seizure. A complete neurological examination and routine laboratory tests as well as EEG returned normal findings. Due to the clinical course of the disease and the seizure semiology, a genetic examination with high suspicion for ADLTE (a requirement for the LGI1 gene and the RELN gene) was performed. For therapeutic purposes, the patient was switched from valproate to carbamazepine (CBZ), at a total dose of 600 mg per day, with a partial effect on seizures (there was a reduction in seizure intensity, not a reduction in frequency). Clobazam (CLB) was added to the carbamazepine at a dose of 40 mg per day, with a pronounced effect on seizures: convulsive seizures disappeared and auditory seizures decreased to 20%. Overall, the patient's quality of life improved, as reported by the patient and his family.

The causal mutation in the RELN gene (c.877G > A p. (Asp293Asn)) in the heterozygous state was confirmed. Despite the patient's negative family history, an investigation of the patient's parents' DNA was recommended. An identical mutation was found in the patient's mother through genetic testing. The patient's mother's EEG was normal and further treatment of the mother was not pursued.

3. Methods

The magnetic resonance data was acquired on a 3 T Siemens Prisma machine. The protocol contained: T1 MPRAGE, T2 FLAIR, T1 MP2RAGE; T2 TSE; T2 FLASH; T1 TIR; T2 TIRM; T1 TIR; T2 TIRM; and T2 TSE sequences.

The high density resting-state EEG (HDEEG) data was acquired using the GES 400 amplifier (Electrical Geodesics, Inc.) with a 256-channel EEG cap. The subject was instructed to sit still with closed eyes during 20 min of recordings.

4. Image analysis

4.1. Morphometry

The T1 MPRAGE and T2 FLAIR images were preprocessed using the SPM12 and CAT12 toolbox (http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat/index.html) running under MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc.). We obtained images showing the spatial distribution of the local grey matter volume/concentration (GMV/GMC). The resulting GMV and GMC images were voxel-wise compared to a set of GMV/GMC images and white matter volume/concentration (WMV/WMC) images acquired with the same MR protocol and resulting from the same preprocessing process applied to data from healthy subjects (HC) (N = 48). The data were intensity normalized by estimating the total intracranial volume to correct for bias introduced by variability in head size [6]. The GMC and WMC images were used to localize abnormalities in grey/white matter junctions [7]. The patient's junction image was compared with the HC using a two-sample T-test with age and gender as nuisance covariates.

The CAT12 output contains an estimate of cortical thickness [13], which makes it possible to localize abnormalities in grey matter with higher sensitivity than VBM. The patient data were compared to HC data in the same way as junctions and GMC/GMV images.

4.2. Functional connectivity

The HDEEG data were segmented into 1 s epochs. We select 300 epochs with clean EEG. The sensor-space data from 256 channels were projected using sLORETA into the source space using Cartool [9]. Using the Corrected Imaginary Coherence metric, we estimated the spatial distribution of local synchrony (LS) in source-space. The increased local synchrony was shown to be a potential marker of epileptogenicity [10]. We compared the patient's LS image with LS images from 26 healthy controls using a two-sample T-test.

5. Results

5.1. MRI findings

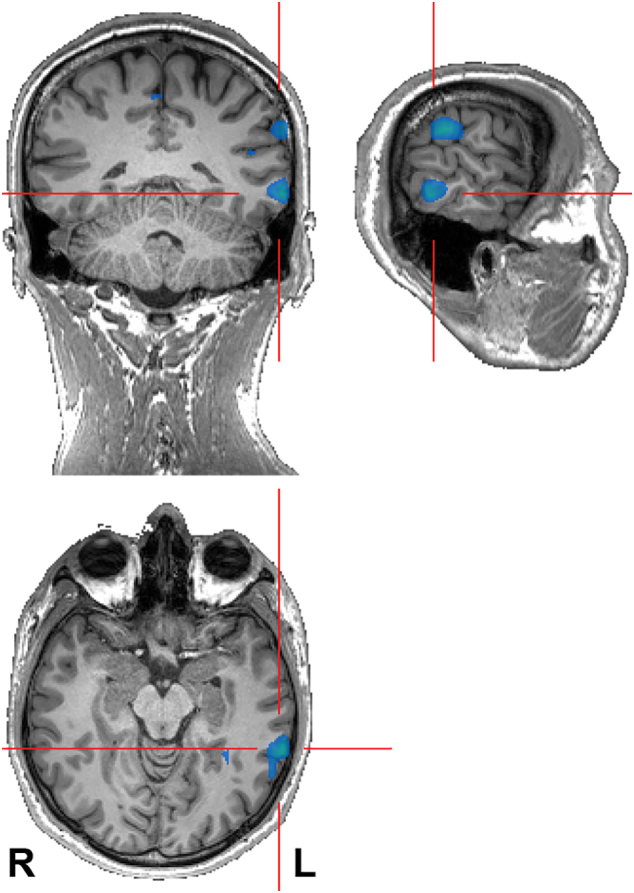

Brain 3 T MRI was used with our patient. We found discrete changes (subtle cortical thickness in T2-weighted sequences and very mild decrease of signal intensity in T1-weighted sequences) in the left superior temporal gyrus on 3 T MRI. Subtle cortical dysplasia in this site was. Consequently, advanced neuroimaging methods (voxel-based 3D MRI analysis, cortical thickness analysis, and functional connectivity) were used. Morphometric MRI analysis (blurred grey-white matter junctions, voxel-based morphometry, and cortical thickness analysis) did not provide any informative results. The functional connectivity analysis revealed higher local synchrony in the left temporal (middle temporal gyrus), left frontal (supplementary motor area, superior frontal gyrus), left parietal (gyrus angularis, gyrus supramarginalis) region and the cingulate (middle cingulate gyrus) gyrus of the patient as compared to healthy controls (See Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Fig. 1.

The regions showing increased local synchrony in the patient as compared to HC (N = 26; p < 0.001).

Table 1.

The regions that show increased local synchrony in the patient as compared to the HC (N = 26; p < 0.001). The underlined regions are depicted in Fig. 1.

| Region | # voxels | Z-valuea | Coordinatea [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|

| L SMA | 19 | 7.02 | − 6 18 72 |

| L supramarginal g | 14 | 6.12 | − 66 − 30 30 |

| L angular g | 40 | 5.84 | − 48 − 66 42 |

| L middle temporal g | 13 | 5.31 | − 66 − 48 − 6 |

| L middle cingulate g | 31 | 5.26 | − 6 12 36 |

| R superior frontal g | 5 | 4.29 | 24 36 54 |

Cluster maximum; L — left; g — gyrus; SMA — supplementary motor area; voxel size = (6 × 6 × 6) mm3.

6. Discussion

We present a case of an 18-year-old patient with an acute manifestation of severe epileptic seizures that had a significant impact on the quality of life of the patient and his family. The age at seizure onset, clinical course of the disease, seizure semiology and the results of the paraclinical examinations indicated possible ADLTE. The diagnosis was supported by genetic testing, which revealed a heterozygous mutation in the RELN gene. In 30–50% of cases, ADLTE is caused by a mutation in the LGI1 gene; around 17% of patients carry a mutation in the RELN gene [2], [3]. Nearly 50% of patients are not tested for causal mutation. Due to the similar clinical course of the disease in both mutations, it is recommended to test for both genes for ADLTE in suspected patients [2]. To our knowledge, seven families have thus far been identified with a proven mutation in the RELN gene [1], [2]. Dazza et al. reported that the dominant type of focal auditory seizures is present in 71% of patients. However, these seizures occur mostly at a low frequency (weekly or yearly). Seizure freedom was achieved with the first antiepileptic drug in 63% of patients; 31% of patients continued to experience sporadic auditory auras on established antiepileptic therapy. Tonic–clonic seizures disappeared in all studied patients [1]. The patient in this case report was not seizure free even after trying several anti-seizure drugs. He continued to experience sporadic auditory auras. However, the quality of life of the patient and the whole family has improved. As a significant success of therapy, the patient reports that the seizure frequency has decreased to 20%, and the tonic–clonic seizures have disappeared on the combination of CBZ and CLB. The patient's EEG was abnormal only at the onset of the disease. Dazza et al. observed routine and/or sleep EEG revealing epileptiform abnormality or deceleration in 12 patients out of a total of 15 (80%); 20% of those patients had normal EEG or non-specific abnormalities [1]. The family history of some individuals with ADLTE may appear negative due to the early unrelated death of a parent, later manifestations of epilepsy (perhaps manifested in the 50th year of life), or reduced penetration. Approximately 33% of patients with a pathogenic variant of the gene remain asymptomatic [3]. If the genetic examination in the proband parents is negative, there are two explanations for the result: germinal mosaicism in the parents or de novo mutation in the proband. The possibility of de novo mutation in this type of epilepsy is assumed to be less than 1% [3].

The homozygous form of mutation in the RELN gene can cause serious brain damage, such as lissencephaly and cerebellar hypoplasia, as well as severe neuronal migration disorders. It can thus be assumed that in the heterozygous form of mutation, small changes in the cortex corresponding to neuronal migration disorders may result [2]. These subtle changes cannot be detected on commonly available low resolution MRI devices. Brain 3 T MRI and advanced neuroimaging methods (voxel-based MRI analysis, cortical thickness analysis, and functional connectivity) were used with our patient. The 3 T MRI findings in the left superior temporal gyrus were felt to be insignificant . Advanced neuroimaging methods including morphometric MRI analysis (blurred grey-white matter junctions, voxel-based morphometry, and cortical thickness analysis) did not provide any informative results. The functional connectivity analysis revealed higher local synchrony in the left temporal, left frontal, and left parietal regions and the cingulate when the patient was compared to healthy controls (see Fig. 1 and Table 1).

The evaluation of brain networks using functional connectivity fMRI is a relatively new technique that has been used successfully to identify brain networks in several conditions, including autism, depression, and schizophrenia [11]. Evidence of multiple areas of functional connectivity confirms the theory of epileptogenic networks in ADTLE. Connectivity abnormalities have potential for clinical relevance and correlation. They may assist with diagnosis, they may provide insights into neurologic deficits associated with TLE, and they may benefit invasive treatments through a more accurate understanding of the functional anatomy of TLE [11]. The epileptogenic network concept is a key factor in identifying the anatomic distribution of the epileptogenic process, which is particularly important in the context of epilepsy surgery [12].

Ethical publication statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Disclosure

None of the authors has any conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Masaryk University, Faculty of Medicine [grant number ROZV/25/LF/2017] and by project 17-32292A of the Czech Health Research Council. We acknowledge the core facility MAFIL of CEITEC, supported by the Czech-BioImaging large RI project (LM2015062 funded by MEYS CR), for their support with obtaining the scientific data presented in this paper. We thank Anne Johnson for English language assistance.

References

- 1.Dazzo E., Fanciulli M., Serioli E., Minervini G., Pulitano P., Binelli S. Heterozygous reelin mutations cause autosomaldominant lateral temporal epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(6):992–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Michelucci R., Pulitano P., Di Bonaventura C., Binelli S., Luisi C., Pasini E. The clinical phenotype of autosomal dominant lateral temporal lobe epilepsy related to reelin mutations. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;68:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ottman Ruth. Autosomal dominant partial epilepsy with auditory features. 2007 April 20. In: Adam M.P., Ardinger H.H., Pagon R.A., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet] University of Washington, Seattle; Seattle (WA): 1993-2017. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1537/ Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong S.E., Shugart Y.Y., Huang D.T., Shahwan S.A., Grant P.E., Hourihane J.O. Autosomal recessive lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia is associated with human RELN mutations. Nat Genet. 2000;26:93. doi: 10.1038/79246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashburner J., Friston K.J. Voxel-based morphometry—the methods. Neuroimage. 2000;11:805–821. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huppertz H.J., Grimm C., Fauser S., Kassubek J., Mader I., Hochmuth A. Enhanced visualization of blurred gray-white matter junctions in focal cortical dysplasia by voxel-based 3D MRI analysis. Epilepsy Res. 2005;67:35–50. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michel C.M., Koenig T., Brandeis D., Gianotti L.R.R., Wackermann J. Cambridge University Press; 2009. Electrical neuroimaging. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schevon C.A., Cappell J., Emerson R., Isler J., Grieve P., Goodman R. Cortical abnormalities in epilepsy revealed by local EEG synchrony. Neuroimage. 2007;35:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haneef Z., Lenartowicz A., Yeh H.J., Levin H.S., Engel J., Jr., Stern J.M. Functional connectivity of hippocampal networks in temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55(1):137–145. doi: 10.1111/epi.12476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartolomei F., Lagarde S., Wendling F., McGonigal A., Jirsa V., Guye M. Defining epileptogenic networks: contribution of SEEG and signal analysis. Epilepsia. 2017;58(7):1131–1147. doi: 10.1111/epi.13791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dahnke R., Yotter R.A., Gaser C. Cortical thickness and central surface estimation. Neuroimage. 2013;65(15):336–348. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.050. http://dbm.neuro.uni-jena.de/cat/index.html. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]