Abstract

The content and organization of mental health care have been heavily influenced by the view that mental difficulties come as diagnosable disorders that can be treated by specialist practitioners who apply evidence‐based practice (EBP) guidelines of symptom reduction at the group level. However, the EBP symptom‐reduction model is under pressure, as it may be disconnected from what patients need, ignores evidence of the trans‐syndromal nature of mental difficulties, overestimates the contribution of the technical aspects of treatment compared to the relational and ritual components of care, and underestimates the lack of EBP group‐to‐individual generalizability. A growing body of knowledge indicates that mental illnesses are seldom “cured” and are better framed as vulnerabilities. Important gains in well‐being can be achieved when individuals learn to live with mental vulnerabilities through a slow process of strengthening resilience in the social and existential domains. In this paper, we examine what a mental health service would look like if the above factors were taken into account. The mental health service of the 21st century may be best conceived of as a small‐scale healing community fostering connectedness and strengthening resilience in learning to live with mental vulnerability, complemented by a limited number of regional facilities. Peer support, organized at the level of a recovery college, may form the backbone of the community. Treatments should be aimed at trans‐syndromal symptom reduction, tailored to serve the higher‐order process of existential recovery and social participation, and applied by professionals who have been trained to collaborate, embrace idiography and maximize effects mediated by therapeutic relationship and the healing effects of ritualized care interactions. Finally, integration with a public mental health system of e‐communities providing information, peer and citizen support and a range of user‐rated self‐management tools may help bridge the gap between the high prevalence of common mental disorder and the relatively low capacity of any mental health service.

Keywords: Mental health care, evidence‐based practice, relational components of care, public health, resilience, peer support, trans‐syndromal symptom reduction, recovery, e‐communities

Mental suffering has been the topic of intense academic research, covering areas of epidemiology, neurobiology, therapeutics and health services organization, and giving rise to evidence‐based practice (EBP) guidelines to achieve symptom reduction that can be used for specific diagnosable mental disorders.

Evidence‐based medicine, in the sense of trying to find out what is or is not likely to work for a particular patient, based on what is known, makes eminent sense. However, the way in which it is (mis)understood and applied may give rise to numerous side effects and limitations, including “cookbook” practice, lack of relevance of EBP outcomes for patients, and lack of group‐to‐individual generalizability1, 2, 3.

The area of mental disorders, and changes therein over time, may be particularly difficult to capture in the conventional medical paradigm of diagnosis and treatment‐induced symptom reduction at the group level. Nevertheless, according to the group‐level symptom‐reduction principle as applied in mental health care, mental suffering comes in the form of universally diagnosable mental disorders which are of bio‐psycho‐social origin and can be classified on the basis of symptoms.

Treatment guidelines are constructed on the basis of meta‐analytic evidence of measurable group‐level symptom reduction, the by far most frequently researched mental health treatment outcome4. The professionals who populate mental health services have been trained in, first, diagnosing a mental disorder in those who seek help for symptoms and, second, providing treatment as prescribed by EBP guidelines.

As different disorders have different symptoms, the diagnosis‐EBP concept as organizing principle of language and activities in mental health service systems has contributed to diagnostic stratification and specialization of institutions, professionals and researchers. Both patients and professionals perceive a need for specialized treatments for specific problems as the primary reference for quality. Consumers know it takes time to search the Internet to find a professional who is adequately specialized in, for example, autism, bipolar disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), post‐traumatic stress disorder or borderline personality disorder.

The diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction model has also impacted health survey technology, which has seen the systematic application of symptom‐based diagnostic criteria for mental disorder to the general population, resulting in high rates of disorders like major depression and anxiety disorders, landing them in the top causes of the global burden of disease.

The total estimated global disease burden of mental illness accounts for 21.2% of years lived with disability (YLDs) and 7.1% of disability‐adjusted life‐years (DALYs)5, which some have argued may represent a substantial underestimation6. Given the limited capacity of the mental health system, data from the population surveys indicating that yearly prevalence rates of mental disorder are around 20% result in the perception of much morbidity remaining untreated.

Mental health awareness campaigns, attuned to the diagnosis‐EBP model, have contributed to growing public awareness of the existence of diagnosable mental disorders and the importance of access to care. Western countries have seen a growing demand for treatments, as evidenced by marked increases in the consumption of psychotropic medications such as antidepressants7, particularly in young people8, growing use of easy‐access manualized non‐pharmacological therapy symptom reduction centres9, and increasing rates of involuntary admissions in European countries10.

Within the diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction perspective, the task of mental health services is to “deliver” specialized treatments that should be made available to those who need them, regardless of whether the setting is “inpatient” , “outpatient” , or “community” treatment.

Countries traditionally differ widely in what mental health services do and how they are organized11. It is assumed that better mental health services are more “evidence‐based”12, and that “routine outcome monitoring” of symptom reduction can be used to assess the quality of the mental health service. However, organizing services around diagnostic specialities providing evidence‐based symptom reduction implies that the diagnosis‐EBP group‐level symptom‐reduction principle is valid, relevant and useful, and that group‐level findings can be translated to individuals3. It also suggests that symptom reduction is a useful construct as a primary focus in the training of professionals and the organization and evaluation of services.

However, “evidence‐based” at the group level may not naturally result in patient‐centred care at the idiographic level13 and has been developed around the discourse of diseases and symptoms, rather than resilience and possibilities14. The question arises to what degree the training of professionals and the planning and evaluation of mental health services should also be guided by other factors.

In this paper, we discuss a number of issues that are relevant in this regard. First, we consider factors that are relevant to the validity of the diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction principle in mental health care, such as the trans‐syndromal nature of psychopathology and the fact that much of the treatment effect observed in EBP is, in fact, reducible to contextual components that are insufficiently acknowledged and embedded in the service and in the training of mental health professionals.

Second, we discuss to what degree organizing services around higher‐order social, existential and somatic outcome domains may potentially be more relevant to users than the traditional focus on evidence‐based, group‐level symptom reduction. Third, we point out that, while the high prevalence rates of mental disorder indicate the need for a coherent public mental health approach, this has not materialized15.

In the final part, we discuss the consequences of these issues for the planning, organization and implementation of mental health services, and make suggestions for change. Although most of the discussion is based on practice as developed in high‐income countries, we believe that some of the core issues are relevant to mental health services worldwide.

THE ADVENT OF TRANS‐SYNDROMAL FORMULATIONS OF PSYCHOPATHOLOGY AND BEYOND

The likelihood ratios for etiology, symptoms, treatment response and prognosis, occasioned by traditional diagnostic categories, are too low to be considered “useful” as required by EBP16, 17, 18. Mental difficulties represent highly variable clusters of trans‐syndromal symptom dimensions that defy detailed diagnostic reduction. The use of 10‐15 broad and overlapping “umbrella” syndromes may be sufficient for daily practice19.

If this is the best “evidence” of classification of psychopathology, should clinicians in mental health services work in diagnostic specialization clinics or “care pathways” , or should they bring their expertise to impact on trans‐syndromal psychopathology, regardless of formal diagnosis?

The perceived value of diagnostic specialization is driven, in part, by the possibility of delineation of homogenous groups in terms of psychopathology, treatment response and prognosis. However, patients with a diagnosis of major depression are heterogeneous in terms of symptoms, treatment response and prognosis, and show high levels of overlap with patients with other diagnoses in terms of symptoms, treatment response and prognosis.

Explicit exclusion criteria in diagnostic systems create a higher‐order factor of what diagnostic categories are not 20, resulting in a myriad of categories that may be separately diagnosable but at the same time remain strongly correlated with each other, resulting in confusingly high “comorbidity” rates and poor reliability in clinical practice. This status quo often leaves patients as well as referring general practitioners (GPs) confused.

A patient‐centred trans‐syndromal framework that flexibly combines categorical, dimensional and network approaches may better serve the purpose of maximizing usefulness for different aspects of clinical practice. However, current diagnostic specialization in research and clinical practice has given rise to a cultural and structural balkanization21 that cannot be readily dismantled, because the professional identity of clinicians tends to fuse with these specializations. Changing the status quo, i.e. bringing practice more in line with available scientific evidence, may thus result in an identity crisis and resistance to what may be seen as a non‐professional sham.

In order to constructively deal with this issue, the DSM‐5 project attempted to introduce the notion of trans‐syndromal dimensions across the different chapters, which would have opened the way to a new form of trans‐syndromal clinical practice and research. Unfortunately, the project proved too complex and only resulted in some trans‐syndromal dimensions being included in one of the appendixes. These, however, were not truly trans‐syndromal, in the sense of cutting across chapters, as all were about within‐chapter dimensional variation22.

In contrast, the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) formulated a range of trans‐syndromal dimensions of behaviour and functioning, with the specific aim to link dimensional variation to biology in research, but these were not meant for use in clinical practice (Research Domain Criteria, RDoC project)23.

The trans‐syndromal approach thus remains an attractive option to bridge the cultural and structural silos that have been built around correlated diagnostic categories, but requires more work. It may be productive to develop a trans‐syndromal framework of mental suffering that not only revolves around symptoms, but also focuses on aspects of behaviour, functioning, psychological traits, somatic factors, social factors and environmental exposures, depending on clinical diagnostic relevance and user preference. This may be productively combined with a limited number of “umbrella” diagnostic categories at the level of the broad syndrome (e.g., psychosis spectrum syndrome)19.

SERVICE AND RELATIONAL EFFECTS AS “INVISIBLE” COMPONENTS OF TREATMENT

Just as there is methodological and statistical doubt as to what degree even a well‐established psychotherapy like cognitive‐behavioral therapy (CBT) is at all effective, doubt has been voiced as to what degree medications like antidepressants have real effects24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29.

While recent meta‐analytic work suggests that antidepressants may have a small effect on symptoms in the short term30, important factors – like bias due to withdrawal symptoms in the placebo group and differential expectations due to the lack of use of active placebo in the comparison with side effect‐rich antidepressants – remain unaddressed. In fact, one of the factors underlying the weak effects of psychotherapy and antidepressants as compared to placebo is the issue of expectations, which evidence suggests may be one of the key elements driving change in states of mental ill‐health31, 32.

As effect sizes of psychotherapy are small, at least in analyses that take into account the many sources of bias and factors impacting quality26, the likelihood of meaningful differences between different types of psychotherapy logically must be similarly small, likely remaining below the threshold of statistical resolution and clinical relevance. This may explain why, despite much research and debate, there is no meta‐analytic evidence that well‐researched psychological treatments for common disorders like depression, anxiety, post‐traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder show clear and clinically relevant differences from each other in effect size, regardless of the level of complexity or underlying anthropological rationale. Instead, meta‐analyses reveal the same (small) effects across different treatment approaches33, 34, 35, 36.

Similarly, there is therapeutic equivalence between different classes of antidepressant medications37 and, although many guidelines suggest that clozapine may be more effective than other antipsychotics in treatment resistant psychotic disorder, the evidence on which this is based is not strong38. However, clozapine may be more effective than other antipsychotics in different outcome areas, which have been researched insufficiently but may stand out clinically.

Where it has been examined, equivalence also applies across pharmacological and non‐pharmacological approaches, for example in depression39. Thus, while some specific differences between treatments may exist in low‐prevalence subareas of mental health, for example in anorexia nervosa40 and obsessive‐compulsive disorder39, findings more often point to equivalence within and between pharmacological and non‐pharmacological treatment approaches for common mental disorders41.

Findings of equivalence of small effects across pharmacological and non‐pharmacological treatments may be, first, suggestive of underlying heterogeneity, in the sense of some people responding only to treatment A and others only to treatment B, and all research populations representing a mix of these two and other types. Although this may be relevant, for example in the case of genetic variation underlying differences in response to pharmacological treatment, no reliable markers of such heterogeneity in response have been identified, despite much research. Also, in psychotherapy research, leaving out critical theoretic components of the therapy does not impact effect size42, 43.

A stronger, although not mutually exclusive, case can be made for a second explanation of apparent equivalence, i.e., that it is not only the specific treatment itself (the “what”), but also generic aspects of treatments (the “how”) which impacts outcome. In favor of the latter is evidence of small but significant “clinician” random effects, meaning that, under the overall small effect of specific treatments, reside differences between the particular patient‐clinician mix, some being more conducive to change than others, not just in psychotherapy research44 but also, in the rare instances where it has been examined, in pharmacological research45.

Thus, if the “how” of treatment contributes to improvement, what is it? Research suggests that two aspects of the context of treatment may be important: a general background service‐level effect and a patient‐clinician relational effect at the level of the therapeutic ritual. These service‐level and patient‐clinician level contextual effects are discussed below.

Service‐level contextual effects

Meta‐analyses have shown that the placebo response in trials of pharmacological treatments such as antidepressants46, antipsychotics47, 48 and pain medications49 has risen over time. One of the factors that may contribute to the rise in placebo response is the change in trial context and design50. If the standard care context amounts to relative “neglect” by poorly developed services, placebo effects will approach natural course, and be lower compared to placebo effects in the context of well‐developed supportive services, confounding comparisons between time periods and countries51. Thus, the early trials are more likely to reflect the comparison between natural course and active treatment, whereas later trials reflect a more “mature” comparison between placebo in the context of general supportive treatment and the specific psychotropic agent.

The same contextual issue regarding the role of standard care may impact trends in psychotherapy research over time, given meta‐analytic evidence that the efficacy of psychotherapeutic treatments like CBT52 has become progressively smaller over time. This is likely related to early trials more often including a “waitlist” comparison – amounting to a comparison with natural course – whereas later trials more often included a more active comparison treatment. As a result, a temporal effect will emerge in meta‐analyses, given evidence from CBT psychotherapy trials that comparison with waiting‐list conditions yields a substantially higher effect size than against care as usual or pill placebo25.

These temporal effects are important, as they appear to suggest that having interactions with an active mental health service brings about improvement in the same way as specific treatments do. It may be productive to further study this issue, as an optimized “general service effect” can impact many patients at the same time in a very cost‐effective fashion.

Patient‐clinician level contextual effects

In conditions such as depression, effects do not appear to differ between treatment approaches, whereas they do vary as a function of the specific patient‐clinician mix. This observation has inspired an ongoing debate on the degree to which so‐called “common factors” contribute to the observed phenomenon of equivalence of treatments31. Common factors have to do with non‐specific relational and ritual elements in the encounter between patient and clinician, such as offering an explanatory model, proposing a theory for change, raising expectations, and inspiring patient engagement, all within the context of a productive therapeutic relationship characterized by empathy, an active and caring attitude, and the capacity to motivate, collaborate and facilitate emotional expression.

The existence for most mental health problems of a 30‐40% “placebo” effect, in the sense of being offered some kind of therapeutic ritual, and the fact that specific evidence‐based treatments only create a small additional effect, is an argument in favor of the existence of common factors.

Evidence for common factors comes from research, including some fascinating examples of experimental studies53, 54, showing the effect of expectations32, 54, the impact of therapeutic relationship55, and therapist effects44. Other support comes from meta‐analyses showing that: a) in depression, having the same number of psychotherapy sessions over a shorter period of time is more effective, suggesting an effect of the intensity of human contact56; b) leaving out critical theoretic components of psychotherapy does not impact effect size42, 43 (although adding components may yield a small increase)43; c) comparisons between active treatments and structurally inequivalent placebos produce larger effects than comparisons between active treatments and structurally equivalent placebos57.

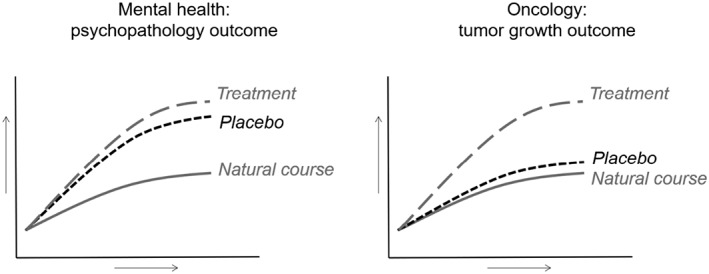

Furthermore, in depression, the rise in placebo response over time has been accompanied by a similar rise in antidepressant response46. This suggests that, at least for depression, the “placebo” response is additive and part of the therapeutic response, in contrast with other areas of medicine, such as oncology, where placebo response constitutes a negligible part of the therapeutic effect (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Contrasting placebo components of therapeutic effect (vertical) over time (horizontal) in psychiatry and oncology

Meta‐analyses of depression trials of antidepressants and transcranial magnetic stimulation also found a positive correlation between the rate of placebo response and active treatment response in trials58, 59. These data are compatible with the notion that the response to active treatment in depression is “added” to the placebo response or that the placebo response is an integral component of the treatment response. In other words, common factors that are part of the general therapeutic ritual may form the basis on which antidepressant treatment can build.

This proposition is supported by research showing that a “relationally warm” treatment works better than a “cold” treatment53 and by studies documenting that pharmacological and non‐pharmacological approaches reinforce each other in the sense of their combined effect being additive, at least in depression and anxiety disorders60. In one trial, a simple focus on positive affect monitoring and feedback on the course of positive emotions was sufficient to make the antidepressant treatment effective61.

THE RELATIVE DISCONNECT OF DIAGNOSIS‐EBP SYMPTOM‐REDUCTION INTERVENTIONS

The delivery of evidence‐based treatments focusing on symptom reduction should ideally serve the higher‐order goal of social participation and existential integration (“recovery”). However, diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction interventions, if they are available at all, are typically delivered by professionals who work in relative dissociation from the existential, social and medical needs of the patient62, 63. For example, a patient may receive a course of CBT for hearing voices, be prescribed antipsychotic medication by a psychiatrist, see a social worker for help with housing and benefits, and visit his general practitioner to receive medication for diabetes. In daily life, however, he may struggle with social isolation, lack of meaning, feelings of hopelessness and massive weight gain.

The different professionals involved in his care may know of each other's existence, but have different schedules and work across different departments and bureaucracies, making it difficult to integrate their efforts. Most importantly, existential needs such as loneliness, meaninglessness and hopelessness are not addressed. While different countries and regions have different levels of integration of care, anecdotal evidence suggests that the situation as depicted here is not rare62, 63. Below, we discuss the issue of integration with social, existential and medical needs in more detail.

Integration with user knowledge and a focus on existential values

The diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction perspective was developed in the context of a bio‐psycho‐social model of mental health difficulties. Several novel developments, however, suggest that the bio‐psycho‐social model requires extension with an existential component, thus reinventing itself as a bio‐psycho‐socio‐existential framework in which the existential component is central.

First, the concept of “health” as absence of disease is risky, as it may result in “too much medicine, too little care”64. This traditional concept, therefore, is increasingly supplanted by the notion that health is about the ability to adjust to and manage medical, social and mental challenges in order to pursue life goals that are meaningful to the person65. In other words, restoration of health is not the goal, but rather the means to enable the patient to find and pursue meaningful goals.

Accordingly, patient existential values are becoming central in the practice of a novel “era 3” of evidence‐informed (interventions support higher‐order social and existential outcomes) rather than evidence‐based (symptom reduction constitutes the core goal) medicine66, 67. In this scenario, doctors naturally focus on existential values, practicing shared decision making in the sense of adjusting interventions to the existential needs of the patient68, 69.

Of course, similar developments have been occurring in mental health care, where users over the last 40 years have become increasingly vocal in asking for more sensitivity on the part of professionals for the existential domain of personal recovery, in the sense of helping people to overcome and adjust to the often extreme experience of mental vulnerability and find meaningful goals to live a fulfilling life, beyond the diagnosis70.

Values associated with the existential recovery perspective are connectedness, empowerment, identity, meaning, hope and optimism71, 72, all reflecting the work of reinventing and reintegrating oneself and one's life after experiencing the existential crisis that comes with mental illness.

While the diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction perspective is not incompatible with these existential notions, there are clear challenges in bringing the medical “symptom reduction” and the existential “meaningful life” perspectives together in one service73, 74. Although research suggests that it is possible to achieve growth in the existential domain in patients attending a psychiatric service75, the level of organizational readiness of traditional psychiatric services may be a rate‐limiting factor in bringing the two perspectives together76, 77.

The diagnosis‐EBP model and the existential domain are complementary from a treatment perspective, as the former has its focus on the psychometric outcome of symptom reduction and the latter on the personal process of resilience. Working on resilience means a focus on things like being connected to other people, narrative development, positive emotions, sense of purpose, material resources and acceptance, requiring novel service initiatives such as a “recovery college” , structural peer support, “housing first” , “individual placement and support” , and “open dialog” , which can be difficult to implement in traditional mental health services78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83.

Integration of mental, medical, substance use and social care

Perhaps the most persistent unresolved need for people with complex mental health difficulties is the lack of alignment between social care and medical care on the one hand, and mental health care and, if organized separately, addiction services on the other84.

People with severe mental health difficulties are more likely to experience a complex social situation characterized by poverty, social isolation, exclusion, unemployment, stigma and housing needs, and more likely to die prematurely, smoke, develop obesity, diabetes, addictions and other chronic conditions. Meeting these needs is difficult, as they require life style changes for which care is allocated to different services. Optimal management involves collaboration between complex bureaucracies managing separate budgets85, giving rise to a range of barriers86. The available evidence suggests that the simple integration of budgets may not be enough to impact outcomes87 and that the area of mental health care can learn from other health areas where such integration has been attempted88, 89.

For example, integration of social and mental health care can focus on the creation of recovery‐oriented social enterprises as a key component of the integrated service90. A user‐driven recovery college may be set up as a social enterprise using social care funding, thus in effect paying users to help other users achieve recovery outcomes.

Successful integration of social, existential, mental, substance use and somatic care needs to take into account the different echelons of clinical, service‐level and public health approaches91. Another factor is scale. It has been suggested that the scale on which integration is attempted is critical, as integration may be best served by focusing on local networks in a relatively small area as a model for organizing mental health services92. Working together in local networks has the advantage of having first‐name‐basis interactions, creating opportunities for flexible needs‐based consultation and joint projects in the area.

A small‐scale area may be around 15,000 population with five‐ten GP practices, allowing for collaboration in an “enhanced primary care” model of mental health services93, 94.

THE PUBLIC HEALTH PERSPECTIVE

The yearly prevalence of diagnosable mental suffering is around 20%, whilst mental health services have the capacity to treat 4‐6% of the population in a given year. These figures indicate that there is considerable scope for public mental health, in the sense of freely accessible sources of information, self‐management and peer support e‐communities.

A public mental health problem cannot be tackled by pushing the diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction system to absurd limits, as evidenced by concern about overprescription of antidepressants95 and ADHD medication96, and increasing rates of involuntary admissions in European countries10.

Although much has been written about the need for a well‐developed system of public mental health alongside the traditional one‐on‐one mental health care system, countries have been slow to implement any of this15, 97.

Nevertheless, in many countries, there is a growing informal network of online, self‐help e‐communities for people with a variety of mental health problems, for example, eating disorders, obsessive‐compulsive disorder, psychosis and post‐traumatic stress disorder. Although some of these have millions of visitors each year, and many increasingly offer forms of e‐health and m‐health solutions that can be used for self‐management, they lack stable funding, even though it is increasingly recognized that they form the backbone of an informal public mental health system which interacts with the traditional mental health care system98.

A minor shift in funding from one‐on‐one care in the traditional diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction mental health care system towards a public mental health network of complementary e‐communities offering information, self‐help and peer support, including a community‐rated market of e‐health and m‐health tools that people help each other using, would bring a welcome balance.

E‐communities are not diagnosis‐specific, but vary in their initial presentation so as to offer people choice in seeking help for what is most compatible with their experience. They can not only help people who are not in contact with services, but also offer self‐help and help in navigating the mental health service system for people already in care99.

CONSEQUENCES FOR MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES

While the specialist diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction principle is dominant or even normative in the way mental health services are organized and evaluated, the question arises to what degree it is relevant to patients. While this model has been productive, there is evidence that it is less than optimally connected to patient primary needs in the social and existential domains.

The expectation that the most vulnerable individuals would naturally reconnect with these domains, when their symptoms resolve, should not be taken for granted. In contrast with common mental health problems, the circularity (reversal of cause and effect) of symptoms, participation and existential domains is the core of the new “severe mental illness” definition developed by a large consensus group in the Netherlands100.

The multitude of randomized controlled trials may have served as trees through which the wood of the larger question, i.e. what patients actually require, could not be seen. In addition, while the diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction model is framed in terms of technical skills and specialized knowledge, the evidence also indicates that a good case can be made for the relational and healing components of ritualized interactions mediating clinical improvement.

Thus, the larger question may be how an effort can be organized to make mental health services more relevant to those who need them, and more in line with a critical analysis of scientific and experiential knowledge. This would require taking a fresh look at both content and organization of services, based on the current level of knowledge (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Factors in the design of a mental health service

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If one were to design a mental health service from scratch, taking into account these developments, it is likely that the new service would bear only moderate resemblance to the current system of diagnosis‐EBP symptom‐reduction based specialist services. It has been suggested that the concept of recovery may serve as the organizing and integrating principle for the novel mental health service101.

If integration and connectedness are important values, it may be more logical to create the mental health service on a relatively small scale (covering around 15,000 population), so as to have an authentic “look and feel” of a local healing community fostering connectedness and strengthening resilience in learning to live with mental vulnerability. Peer support, for example, organized at the level of a recovery college, may form the backbone of the community.

The primary process of narrative development and finding and realizing meaningful goals should be supported by treatments aimed at trans‐syndromal symptom reduction, specifically tailored to strengthen the primary process of recovery and participation, and applied by professionals who have been trained to embrace idiography and to maximize effects mediated by therapeutic relationship and aspects of the care ritual.

Education would be organized as person‐centered, self‐directed, practice‐based and inter‐professional interaction between clients, students of different professions, and different mental health professionals, to ensure adequate development of attitudes, knowledge and skills in collaborating, communicating and relating to each other102. Crisis intervention may be organized using a combination of peer‐supported open dialog and local shelters, increasing the community capacity for social holding.

Some aspects of mental health services would continue to require a regional organization level: for example, high intensive care units, medium security units, and child/youth transition psychiatric services, including “headspace”‐type public mental health approaches103.

Importantly, the local healing community should be integrated with local social care (housing, work, education), focusing on recovery‐oriented local social enterprises, working with “enhanced” local GP practices in order to integrate medical care.

The mental health service, organized as local healing community and associated regional components, should be able to cater for around 4‐6% of the population and have strong links with a public mental health system of complementary e‐communities with capacity for up to 20% of the population, integrated with a user‐quality rated public health “market” of e‐health and m‐health tools for “blended” self‐management approaches.

It is clear that the scale and complexity of the proposed change is such that it cannot be evaluated in a randomized controlled trial. We have, therefore, suggested that it may be more productive to engage in a form of action‐research and create a number of pilot projects along the lines described above and learn along the way104. A number of these pilot projects are currently underway, in the Netherlands and undoubtedly in many other countries.

A more ambitious attempt at evaluation would be to study pilot areas in a quasi‐experimental design, with even perhaps randomization at the county or neighborhood level. While this would require considerable funding, it could be argued that it involves the most pressing, yet perhaps most neglected, area of mental health research to date.

After decades of funding of large scale efforts to delineate the biological mechanisms of mental illness and to conduct randomized clinical trials of symptom reduction strategies, that are not independent of legitimization issues of the academic professions of psychiatry and psychology, the time may have come to coordinate a large‐scale effort around the content and design of (public) mental health services, taking into account both professional and user knowledge.

REFERENCES

- 1. Greenhalgh T, Howick J, Maskrey N et al. Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis? BMJ 2014;348:g3725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barbui C, Purgato M, Churchill R et al. Evidence‐based interventions for global mental health: role and mission of a new Cochrane initiative. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;4:ED000120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fisher AJ, Medaglia JD, Jeronimus BF. Lack of group‐to‐individual generalizability is a threat to human subjects research. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2018;115:E6106‐15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Miyar J, Adams CE. Content and quality of 10,000 controlled trials in schizophrenia over 60 years. Schizophr Bull 2013;39:226‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. GBD 2013 DALYs and HALE Collaborators , Murray CJ, Barber RM et al. Global, regional, and national disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition. Lancet 2015;386:2145‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:171‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development . Antidepressant drugs consumption, 2000 and 2015 (or nearest year), in pharmaceutical sector. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development Publishing, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Steinhausen HC. Recent international trends in psychotropic medication prescriptions for children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;24:635‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clark DM. Realizing the mass public benefit of evidence‐based psychological therapies: the IAPT program. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2018;14:159‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wise J. Mental health: patients and service in crisis. BMJ 2017;356:j1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. van Os J, Neeleman J. Caring for mentally ill people. BMJ 1994;309:1218‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aarons GA, Glisson C, Green PD et al. The organizational social context of mental health services and clinician attitudes toward evidence‐based practice: a United States national study. Implement Sci 2012;7:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hasnain‐Wynia R. Is evidence‐based medicine patient‐centered and is patient‐centered care evidence‐based? Health Serv Res 2006;41:1‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Slade M, Longden E. Empirical evidence about recovery and mental health. BMC Psychiatry 2015;15:285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wahlbeck K. Public mental health: the time is ripe for translation of evidence into practice. World Psychiatry 2015;14:36‐42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sackett DL, Richardson WS, Rosenberg W et al. Evidence‐based medicine. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Os J. A salience dysregulation syndrome. Br J Psychiatry 2009;194:101‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maj M. Why the clinical utility of diagnostic categories in psychiatry is intrinsically limited and how we can use new approaches to complement them. World Psychiatry 2018;17:121‐2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Guloksuz S, van Os J. The slow death of the concept of schizophrenia and the painful birth of the psychosis spectrum. Psychol Med 2018;48:229‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bell RC, Dudgeon P, McGorry PD et al. The dimensionality of schizophrenia concepts in first‐episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1998;97:334‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ahn WK, Proctor CC, Flanagan EH. Mental health clinicians' beliefs about the biological, psychological, and environmental bases of mental disorders. Cognit Sci 2009;33:47‐82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barch DM, Bustillo J, Gaebel W et al. Logic and justification for dimensional assessment of symptoms and related clinical phenomena in psychosis: relevance to DSM‐5. Schizophr Res 2013;150:15‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cuthbert BN, Insel TR. Toward new approaches to psychotic disorders: the NIMH Research Domain Criteria project. Schizophr Bull 2010;36:1061‐2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kirsch I, Moncrieff J. Clinical trials and the response rate illusion. Contemp Cin Trials 2007;28:348‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cuijpers P, Cristea IA, Karyotaki E et al. How effective are cognitive behavior therapies for major depression and anxiety disorders? A meta‐analytic update of the evidence. World Psychiatry 2016;15:245‐58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Bohlmeijer E et al. The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: a meta‐analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychol Med 2010;40:211‐23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wampold BE, Fluckiger C, Del Re AC et al. In pursuit of truth: a critical examination of meta‐analyses of cognitive behavior therapy. Psychother Res 2017;27:14‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Owen J, Drinane JM, Idigo KC et al. Psychotherapist effects in meta‐analyses: how accurate are treatment effects? Psychotherapy 2015;52:321‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leichsenring F, Abbass A, Hilsenroth MJ et al. Biases in research: risk factors for non‐replicability in psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy research. Psychol Med 2017;47:1000‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Lancet 2018;391:1357‐66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wampold BE. How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry 2015;14:270‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rutherford BR, Wall MM, Glass A et al. The role of patient expectancy in placebo and nocebo effects in antidepressant trials. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:1040‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cuijpers P, Donker T, van Straten A et al. Is guided self‐help as effective as face‐to‐face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychol Med 2010;40:1943‐57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cuijpers P, Karyotaki E, Reijnders M et al. Was Eysenck right after all? A reassessment of the effects of psychotherapy for adult depression. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cristea IA, Gentili C, Cotet CD et al. Efficacy of psychotherapies for borderline personality disorder: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:319‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Steenkamp MM, Litz BT, Hoge CW et al. Psychotherapy for military‐related PTSD: a review of randomized clinical trials. JAMA 2015;314:489‐500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. von Wolff A, Holzel LP, Westphal A et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants in the acute treatment of chronic depression and dysthymia: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Affect Disord 2013;144:7‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Samara MT, Dold M, Gianatsi M et al. Efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of antipsychotics in treatment‐resistant schizophrenia: a network meta‐analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73:199‐210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL et al. The efficacy of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders: a meta‐analysis of direct comparisons. World Psychiatry 2013;12:137‐48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zipfel S, Wild B, Gross G et al. Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:127‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Huhn M, Tardy M, Spineli LM et al. Efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy for adult psychiatric disorders: a systematic overview of meta‐analyses. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:706‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ahn H, Wampold BE. Where oh where are the specific ingredients? A meta‐analysis of component studies in counseling and psychotherapy. J Couns Psychol 2001;48:251‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bell EC, Marcus DK, Goodlad JK. Are the parts as good as the whole? A meta‐analysis of component treatment studies. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013;81:722‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Baldwin SA, Imel ZE. Therapist effects: findings and methods In: Lambert MJ. (ed). Bergin and Garfield's handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change, 6th ed. New York: Wiley, 2013:258‐97. [Google Scholar]

- 45. McKay KM, Imel ZE, Wampold BE. Psychiatrist effects in the psychopharmacological treatment of depression. J Affect Disord 2006;92:287‐90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Khan A, Mar KF, Faucett J et al. Has the rising placebo response impacted antidepressant clinical trial outcome? Data from the US Food and Drug Administration 1987‐2013. World Psychiatry 2017;16:181‐92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rutherford BR, Pott E, Tandler JM et al. Placebo response in antipsychotic clinical trials: a meta‐analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:1409‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Leucht S, Chaimani A, Leucht C et al. 60 years of placebo‐controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: meta‐regression of predictors of placebo response. Schizophr Res (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tuttle AH, Tohyama S, Ramsay T et al. Increasing placebo responses over time in U.S. clinical trials of neuropathic pain. Pain 2015;156:2616‐26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Leucht S et al. Is placebo response in antidepressant trials rising or not? A reanalysis of datasets to conclude this long‐lasting controversy. Evid Based Ment Health 2018;21:1‐3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tyrer P. Are small case‐loads beautiful in severe mental illness? Br J Psychiatry 2000;177:386‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Johnsen TJ, Friborg O. The effects of cognitive behavioral therapy as an anti‐depressive treatment is falling: a meta‐analysis. Psychol Bull 2015;141:747‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kaptchuk TJ, Kelley JM, Conboy LA et al. Components of placebo effect: randomised controlled trial in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. BMJ 2008;336:999‐1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kam‐Hansen S, Jakubowski M, Kelley JM et al. Altered placebo and drug labeling changes the outcome of episodic migraine attacks. Sci Transl Med 2014;6:218ra5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Fluckiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE et al. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta‐analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cuijpers P, Huibers M, Ebert DD et al. How much psychotherapy is needed to treat depression? A metaregression analysis. J Affect Disord 2013;149:1‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Baskin TW, Tierney SC, Minami T et al. Establishing specificity in psychotherapy: a meta‐analysis of structural equivalence of placebo controls. J Consult Clin Psychol 2003;71:973‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Iovieno N, Papakostas GI. Correlation between different levels of placebo response rate and clinical trial outcome in major depressive disorder: a meta‐analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:1300‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Razza LB, Moffa AH, Moreno ML et al. A systematic review and meta‐analysis on placebo response to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression trials. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2018;81:105‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Cuijpers P, Sijbrandij M, Koole SL et al. Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: a meta‐analysis. World Psychiatry 2014;13:56‐67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kramer I, Simons CJ, Hartmann JA et al. A therapeutic application of the experience sampling method in the treatment of depression: a randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry 2014;13:68‐77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. The Schizophrenia Commission . The abandoned illness. London: Rethink, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Van Sambeek N, Tonkens E, Bröer C. Sluipend kwaliteitsverlies in de geestelijke gezondheidszorg. Professionals over de gevolgen van marktwerking. Beleid en Maatschappij 2011;38:47‐64. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Glasziou P, Moynihan R, Richards T et al. Too much medicine; too little care. BMJ 2013;347:f4247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L et al. How should we define health? BMJ 2011;343:d4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Richards T, Snow R, Schroter S. Co‐creating health: more than a dream. BMJ 2016;354:i4550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Berwick DM. Era 3 for medicine and health care. JAMA 2016;315:329‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Emanuel EJ, Gudbranson E. Does medicine overemphasize IQ? JAMA 2018;319:651‐2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. VanderWeele TJ, Balboni TA, Koh HK. Health and spirituality. JAMA 2017;318:519‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Deegan PE. Recovery and empowerment for people with psychiatric disabilities. Soc Work Health Care 1997;25:11‐24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C et al. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. Br J Psychiatry 2011;199:445‐52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Stuart SR, Tansey L, Quayle E. What we talk about when we talk about recovery: a systematic review and best‐fit framework synthesis of qualitative literature. J Ment Health 2017;26:291‐304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Anthony WA. Recovery from mental illness. The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosoc Rehabil J 1993;16:11‐23. [Google Scholar]

- 74. Boevink W. TREE: Towards recovery, empowerment and experiential expertise of users of psychiatric services In: Rian P, Ramon S, Greacen T. (eds). Empowerment, lifelong learning and recovery in mental health: towards a new paradigm. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2012:36‐49. [Google Scholar]

- 75. Macpherson R, Pesola F, Leamy M et al. The relationship between clinical and recovery dimensions of outcome in mental health. Schizophr Res 2016;175:142‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Leamy M, Clarke E, Le Boutillier C et al. Implementing a complex intervention to support personal recovery: a qualitative study nested within a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLoS One 2014;9:e97091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Stuber J, Rocha A, Christian A et al. Predictors of recovery‐oriented competencies among mental health professionals in one community mental health system. Community Ment Health J 2014;50:909‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Rhenter P, Tinland A, Grard J et al. Problems maintaining collaborative approaches with excluded populations in a randomised control trial: lessons learned implementing Housing First in France. Health Res Policy Syst 2018;16:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Burhouse A, Rowland M, Marie Niman H et al. Coaching for recovery: a quality improvement project in mental healthcare. BMJ Qual Improv Rep 2015;4(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Buus N, Bikic A, Jacobsen EK et al. Adapting and implementing open dialogue in the Scandinavian countries: a scoping review. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2017;38:391‐401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Editorial . Open Dialogue method of mental health care launched in the UK. Ment Health Today 2015:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Tanenbaum SJ. Mental health consumer‐operated services organizations in the US: citizenship as a core function and strategy for growth. Health Care Anal 2011;19:192‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Slade M. Implementing shared decision making in routine mental health care. World Psychiatry 2017;16:146‐53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Druss BG, Goldman HH. Integrating health and mental health services: a past and future history. Am J Psychiatry (in press). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kuluski K, Ho JW, Hans PK et al. Community care for people with complex care needs: bridging the gap between health and social care. Int J Integr Care 2017;17:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Rodgers M, Dalton J, Harden M et al. Integrated care to address the physical health needs of people with severe mental illness: a mapping review of the recent evidence on barriers, facilitators and evaluations. Int J Integr Care 2018;18:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Baxter S, Johnson M, Chambers D et al. The effects of integrated care: a systematic review of UK and international evidence. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Allen D, Rixson L. How has the impact of ‘care pathway technologies' on service integration in stroke care been measured and what is the strength of the evidence to support their effectiveness in this respect? Int J Evid Based Healthc 2008;6:78‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Liu NH, Daumit GL, Dua T et al. Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agenda. World Psychiatry 2017;16:30‐40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Roy MJ, Donaldson C, Baker R et al. The potential of social enterprise to enhance health and well‐being: a model and systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2014;123:182‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. van Os J, Delespaul PH. A valid quality system for mental health care: from accountability and control in institutionalised settings to co‐creation in small areas and a focus on community vital signs. Tijdschr Psychiatr 2018;60:96‐104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Fleury MJ, Mercier C. Integrated local networks as a model for organizing mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health 2002;30:55‐73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Funk M, Ivbijaro G. Integrating mental health into primary care: a global perspective. Geneva: World Health Organization/WONCA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 94. London Strategic Clinical Network for Mental Health . A commissioner's guide to primary care mental health. London: London Strategic Clinical Network for Mental Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Adlington K. Pop a million happy pills? Antidepressants, nuance, and the media. BMJ 2018;360:k1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Dunlop AJ, Newman LK. ADHD and psychostimulants – overdiagnosis and overprescription. Med J Aust 2016;204:139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Campion J, Knapp M. The economic case for improved coverage of public mental health interventions. Lancet Psychiatry 2018;5:103‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. van Os J. ‘Multi‐expert’ eCommunities as the basis of a novel system of public mental health. Tijdschrift voor Gezondheidswetenschappen 2018;96:62‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Griffiths KM. Mental health Internet support groups: just a lot of talk or a valuable intervention? World Psychiatry 2017;16:247‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Delespaul PH, de consensusgroep EPA. Consensus regarding the definition of persons with severe mental illness and the number of such persons in The Netherlands. Tijdschr Psychiatr 2013;55:427‐38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Davidson L, White W. The concept of recovery as an organizing principle for integrating mental health and addiction services. J Behav Health Serv Res 2007;34:109‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Vijn TW, Wollersheim H, Faber MJ et al. Building a patient‐centered and interprofessional training program with patients, students and care professionals: study protocol of a participatory design and evaluation study. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. McGorry PD, Tanti C, Stokes R et al. headspace: Australia's National Youth Mental Health Foundation – where young minds come first. Med J Aust 2007;187:S68‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Delespaul P, Milo M, Schalken F et al. GOEDE GGZ! Nieuwe concepten, aangepaste taal, verbeterde organisatie. Amsterdam: Diagnosis Uitgevers, 2016. [Google Scholar]