Abstract

With the rapid increase in cancer survival because of improved diagnosis and therapy in the past decades, cancer treatment–related cardiotoxicity is becoming an urgent healthcare concern. The anthracycline doxorubicin (DOX), one of the most effective chemotherapeutic agents to date, causes cardiomyopathy by inducing cardiomyocyte apoptosis. We demonstrated previously that overexpression of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21 promotes resistance against DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Here we show that DOX exposure provokes cardiac CDK2 activation and cardiomyocyte cell cycle S phase reentry, resulting in enhanced cellular sensitivity to DOX. Genetic or pharmacological inhibition of CDK2 markedly suppressed DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. Conversely, CDK2 overexpression augmented DOX-induced apoptosis. We also found that DOX-induced CDK2 activation in the mouse heart is associated with up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic BCL2 family member BCL2-like 11 (Bim), a BH3-only protein essential for triggering Bax/Bak-dependent mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. Further experiments revealed that DOX induces cardiomyocyte apoptosis through CDK2-dependent expression of Bim. Inhibition of CDK2 with roscovitine robustly repressed DOX-induced mitochondrial depolarization. In a cardiotoxicity model of chronic DOX exposure (5 mg/kg weekly for 4 weeks), roscovitine administration significantly attenuated DOX-induced contractile dysfunction and ventricular remodeling. These findings identify CDK2 as a key determinant of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. CDK2 activation is necessary for DOX-induced Bim expression and mitochondrial damage. Our results suggest that pharmacological inhibition of CDK2 may be a cardioprotective strategy for preventing anthracycline-induced heart damage.

Keywords: anticancer drug, cardiovascular disease, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK), cell cycle, cell death, mitochondria, anthracycline, Bim, cardiotoxicity, chemotherapy

Introduction

Over the last three decades, advances in cancer therapy have led to a remarkable drop in mortality rates and, consequently, a rapid increase in the number of cancer survivors, which is expected to reach more than 20 million in the United States by 2026 (1). Many of these cancer survivors suffer from treatment-related cardiac complications later in life, and cardiovascular disease has become the second leading cause of death in this patient population, immediately following recurrent malignancy (2). A prototypical example of anticancer treatment–related cardiotoxic side effects is cardiomyopathy caused by the widely used anthracycline doxorubicin (DOX).2 Mechanistically, DOX induces DNA double-strand breaks through formation of the topoisomerase 2β–DOX–DNA ternary cleavage complex, leading to apoptotic death of cardiomyocytes (3). Intercalation of DOX into DNA causes eviction of histone, including H2AX, from open chromosomal regions, resulting in alteration of the transcriptome and attenuation of DNA damage repair (4). In addition, DOX also preferentially accumulates in mitochondria, increasing mitochondrial iron levels and inducing generation of reactive oxygen species (5). To date, the only Food and Drug Administration–approved cardioprotective agent for anthracycline chemotherapy is dexrazoxane, which exerts its protective function by inducing proteasomal degradation of topoisomerase 2β and/or reducing mitochondrial iron levels (2, 5). However, dexrazoxane has not been broadly used in clinical practice because it may potentially compromise the antitumor activity of anthracyclines (2). Further understanding the molecular mechanisms of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity is therefore warranted for the development of effective cardioprotective strategies.

Activation of the intrinsic apoptosis pathway is a major mechanism underlying DOX-induced cardiotoxicity (2). In response to irreparable DNA damage following DOX exposure, cardiac myocytes initiate the endogenous apoptosis program that involves Bax/Bak activation, mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, cytochrome c release, and caspase-dependent cleavage of essential cellular proteins (6). The apoptosis process is regulated by a plethora of signaling cascades at multiple levels. We reported previously that the Cip/Kip family cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21 plays a critical role in protection of mitochondrial integrity and inhibition of DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis (7). It is widely known that p21 mediates growth arrest by inhibiting the kinase activities of a wide range of CDKs, including CDK2 and CDK1, as well as interfering with proliferating cell nuclear antigen–dependent DNA polymerase activity (8). Emerging evidence suggests that p21 also regulates gene expression and additional biological events through direct protein–protein interactions that are independent of CDK and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (8). At present, it is still unclear whether p21 exerts cardioprotection through inhibition of CDK activity, and its potential targets in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity remain to be characterized.

The mammalian CDK family includes 20 members that are divided into two groups: cell cycle–related CDKs, comprising three subfamilies represented by CDK1, CDK4, and CDK5, and transcriptional CDKs, comprising five subfamilies represented by CDK7, CDK8, CDK9, CDK11, and CDK20 (9). Among the CDK1 subfamily members, CDK1 is essential for cell cycle progression through G2/M phase (major events include karyokinesis and cytokinesis), whereas activation of CDK2 triggers cell cycle transition from G1 to S phase and induces DNA synthesis/replication. It has been reported that adult cardiomyocyte DNA synthesis is dramatically induced by myocardial injury (10), suggesting that the S phase–driving kinase CDK2 may potentially regulate the cardiac stress response. In this study, we explored the role of CDK2 in DOX-induced cardiac toxicity and demonstrated that DOX exposure induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiomyopathy through activation of CDK2.

Results

DOX induced CDK2 activation in mouse heart and cultured cardiomyocytes

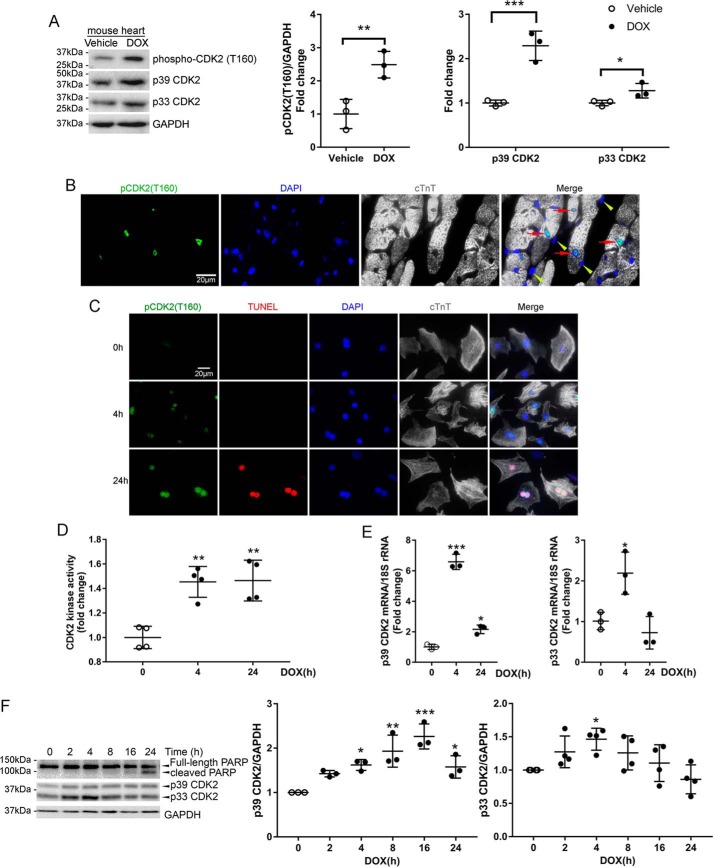

We previously demonstrated that DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis was suppressed by the Cip/Kip family CDK inhibitor p21 (7), which mediates G1/S cell cycle arrest primarily by inhibiting the kinase activity of CDK2 (8). To determine whether CDK2 might play a role in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, we first measured CDK2 activity in the mouse heart 24 h following a single DOX injection (5 mg/kg) according to a recent study (11). Western blot analysis of heart lysates revealed that DOX treatment robustly increased the level of phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160, Fig. 1A), a reliable marker of CDK2 activation (12, 13). Interestingly, total CDK2 protein levels were also elevated, although a greater increase was observed in the p39 isoform than in p33 CDK2 (Fig. 1A). Intraperitoneal injection of DOX at 20 mg/kg, a higher dose widely used in previous studies of DOX cardiotoxicity (14), also induced myocardial CDK2 activation (Fig. S1A). Following DOX administration, phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160) was primarily detected in cardiomyocyte nuclei (Fig. 1B, red arrows).

Figure 1.

DOX induced CDK2 activation in mouse heart and cultured cardiomyocytes. A, mice received a single injection of DOX (5 mg/kg, i.p.) or an equal volume of saline, and hearts were harvested at 24 h (n = 3/group). Heart protein lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies with GAPDH as a loading control. Values are mean ± S.D. and were analyzed using two-tailed Student's t test. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. B, immunofluorescence staining for phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160, green), cardiac troponin T (cTnT, gray) and nuclei (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), blue) in the mouse heart 24 h after DOX injection (5 mg/kg, i.p.). Phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160) predominantly localized in nuclei of cardiomyocytes (red arrows) but not in nonmyocytes (yellow arrowheads). C, immunofluorescence staining for phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160, green), cTnT (gray), and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in NRCMs treated with DOX (1 μm) for 0, 4, or 24 h. Apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL staining (red). D, NRCMs were treated with DOX (1 μm) for 0, 4, or 24 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-CDK2 antibody, and CDK2-associated kinase activity was determined by the luminescent signal intensity from the ADP-Glo kinase assay (n = 3). **, p < 0.01 versus time 0. E, qRT-PCR analysis of CDK2 mRNA levels in NRCMs treated with DOX (1 μm) for 0, 4, or 24 h (n = 3). Data were normalized to levels of 18S rRNA. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 versus time 0. F, NRCMs were treated with DOX (1 μm) for various periods of time (n = 3–4). Cell lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. One-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 versus time 0.

To determine whether DOX treatment induced cardiomyocyte CDK2 activation in a cell-autonomous fashion, primary neonatal rat cardiomyocytes (NRCMs) were incubated with DOX (1 μm) for 4 or 24 h. Consistent with our in vivo results, DOX treatment dramatically increased the phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160) level at both time points (Fig. 1C). At 24 h after DOX treatment, phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160)–positive cardiomyocytes were also labeled with TUNEL (Fig. 1C), an indicator of DNA strand breaks generated during apoptosis, suggesting that CDK2 activation was associated with cardiomyocyte apoptosis. An in vitro kinase assay with histone H1 as a substrate revealed that CDK2-associated kinase activity was significantly elevated in NRCMs following DOX exposure (Fig. 1D). To rule out the possibility that DOX directly binds and activates CDK2, we performed an in vitro cell-free kinase assay and found that CDK2 activity was not increased after addition of DOX (Fig. S1B), indicating that DOX-induced cardiac CDK2 activation likely involves additional signaling molecules. Moreover, the mRNA levels of p39 and p33 CDK2s were significantly increased after DOX treatment for 4 h, and the p39 transcript remained elevated above baseline for up to 24 h (Fig. 1E). Consistently, DOX treatment induced a time-dependent increase in p39 protein that peaked at 16 h and a transient up-regulation of the p33 isoform of CDK2 (Fig. 1F and Fig. S1C). A similar trend was observed in H9c2 cells, a myoblast cell line derived from the rat heart (Fig. S1D). Up-regulation of both p33 and p39 CDK2 precedes cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP, Fig. 1F), a caspase substrate that is cleaved upon induction of apoptosis, suggesting that CDK2 may play a role in the initiation of DOX-induced apoptosis.

Nuclear localization of CDK2 is necessary for its enzymatic activation and cellular function because the majority of CDK2 substrates reside in the nucleus (13). Immunofluorescence staining of cardiomyocytes revealed that CDK2 predominantly localized in the cytoplasm and that DOX treatment resulted in a strong increase in nuclear CDK2 (Fig. S1E). To further examine whether DOX induced nuclear translocation of CDK2, NRCMs were treated with DOX for 4 or 24 h, and subcellular fractionation revealed that DOX induced significant increases in nuclear p33 and p39 CDK2s at 4 and 24 h, respectively (Fig. S1F). By contrast, cytosolic CDK2 levels were not significantly changed, suggesting that the DOX-induced increase of nuclear CDK2 was not caused by translocation from the cytosol to nuclei but were likely due to de novo protein synthesis.

DOX-induced CDK2 activation promoted cardiomyocyte cell cycle S phase reentry

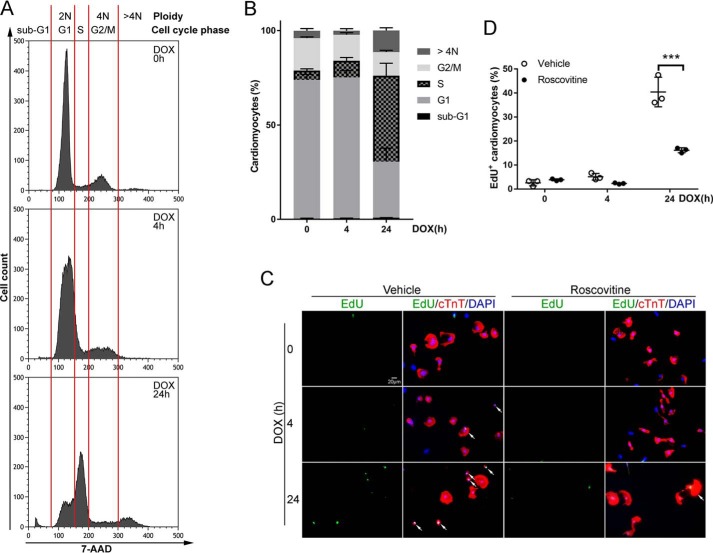

It is well-known that CDK2 activation drives cell cycle G1/S transition (8). To determine whether DOX-induced CDK2 activation promotes cell cycle progression, NRCMs treated with DOX were subjected to cell cycle analysis using flow cytometry. Remarkably, DOX treatment resulted in an astounding increase in cardiomyocytes in S phase in a time-dependent manner as well as an accumulation of cardiomyocytes with more than 4N ploidy at 24 h (Fig. 2, A and B, and Table S1). A defining feature of cell cycle S phase is de novo DNA synthesis, which can be evaluated by incorporation of the thymidine analog 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) into DNA. Therefore, NRCMs were incubated with EdU at the end of DOX treatment to detect active DNA synthesis. In agreement with our cell cycle profile data, DOX treatment robustly induced EdU incorporation into cardiomyocyte DNA (Fig. 2, C and D), suggesting that DOX exposure enhanced cell cycle activity and resulted in cardiomyocyte S phase reentry. To further examine whether CDK2 activation is necessary for DOX-induced S phase reentry, cardiomyocyte CDK2 was inactivated by incubation with roscovitine, a small-molecule CDK inhibitor, prior to challenge with DOX. As expected, roscovitine markedly reduced EdU-positive cardiomyocytes following DOX treatment (Fig. 2, C and D). Together, these results suggested that DOX induced cardiomyocyte S phase reentry and new DNA synthesis through activation of CDK2. Interestingly, S phase reentry was associated with early apoptotic morphological changes such as cardiomyocyte shrinkage and rounding (Fig. 2C, arrows), indicating a direct connection between cell cycle progression and apoptosis. Our data are in agreement with previous findings that cell cycle reentry is a critical component of DNA damage–induced apoptosis in postmitotic neurons (15).

Figure 2.

DOX-induced CDK2 activation promoted cardiomyocyte cell cycle S phase reentry. A and B, NRCMs were treated with DOX (1 μm) for 0, 4, or 24 h. Cells were stained with 7-AAD (1 μg/ml) prior to cell cycle analysis with flow cytometry (n = 3–4). A, representative cell cycle histograms. Diploid (2N) cells, tetraploid (4N) cells, and individual cell cycle phases are separated by red lines. B, percentage of cell population in different phases of the cell cycle. Data are mean ± S.D. Statistical significance are shown in Table S1. C and D, NRCMs were pretreated with vehicle or the pharmacological CDK2 inhibitor roscovitine (50 μm) for 1 h prior to treatment with DOX (1 μm) for 0, 4, or 24 h. Cells were then incubated with EdU (10 μm) for 1 h. C, representative images of EdU (green) incorporation into cardiomyocyte (cTnT, red) nuclei (DAPI, blue). Arrows indicate EdU+ cardiomyocytes. D, percentage of EdU-positive cardiomyocytes (n = 3). Data are mean ± S.D. ***, p < 0.001.

Inhibition of CDK2-dependent S phase reentry protected against DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis

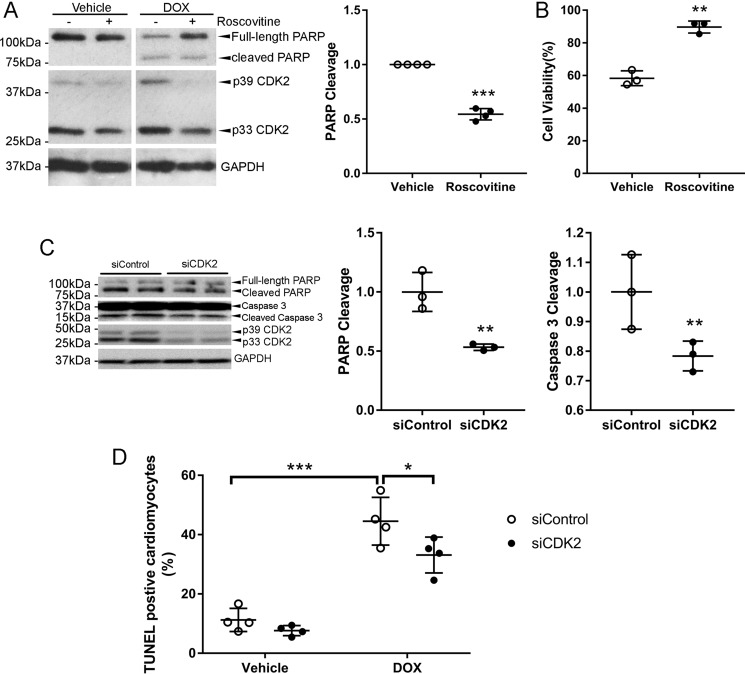

It has long been appreciated that DOX exhibits cell cycle–dependent cytotoxicity, with cells in S phase being more sensitive than those in G1 phase (16). Indeed, inhibition of S phase reentry with roscovitine (Fig. 2, C and D) profoundly repressed DOX-induced PARP cleavage (Fig. 3A), suggesting that S phase reentry enhanced the sensitivity of cardiomyocytes to DOX cytotoxicity. Surprisingly, treatment with roscovitine for 24 h also reduced CDK2 protein levels (Fig. 3A). Cell viability as measured by MTT assay revealed that roscovitine significantly increased cell viability following DOX treatment (Fig. 3B). It has been shown that roscovitine exhibits synergistic antitumor activity with DOX in a p53-mutant triple-negative breast cancer xenograft model only when administered sequentially before DOX (17). However, roscovitine was able to protect against DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis regardless of the treatment order (Fig. S2A). DOX-induced apoptosis was also suppressed by the second-generation CDK inhibitor dinaciclib (Fig. S2B). To determine whether selective inhibition of CDK2 is sufficient for protection, NRCMs were pretreated with CDK2 inhibitor II (CDK2i), a specific small-molecule inhibitor for CDK2. As expected, cell viability following DOX exposure was significantly higher in the CDK2i-treated group than in the vehicle control (Fig. S2C).

Figure 3.

Inhibition of CDK2-dependent S phase re-entry protected against DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. A and B, NRCMs were pretreated with the CDK inhibitor roscovitine (50 μm) for 1 h prior to incubation with DOX (1 μm) for 24 h (n = 3–4). A, cell lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies, with GAPDH as a loading control. B, cell viability was assessed by MTT assay. Two-tailed Student's t test. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 versus vehicle control. C and D, NRCMs were transfected with control (siControl) or CDK2 siRNA (siCDK2, 25 nm) prior to treatment with DOX (1 μm) for 48 (C, n = 3) or 24 h (D, n = 4). C, cell lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies, with GAPDH as a loading control. Data are mean ± S.D. and were analyzed by two-tailed Student's t test. **, p < 0.01 versus siControl. D, TUNEL staining revealed that knockdown of CDK2 suppressed DOX-induced apoptosis. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak test. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

To further determine whether CDK2 is necessary for DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis, specific siRNAs were used to silence both isoforms of CDK2 in NRCMs (Fig. 3C). Knockdown of CDK2 significantly inhibited DOX-induced cleavage of PARP and caspase 3, suggesting that CDK2 is necessary for DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis. TUNEL reactivity was also significantly reduced in CDK2-depleted cells following DOX treatment (Fig. 3D). An MTT assay revealed that CDK2 depletion moderately but significantly increased cell viability after incubation with DOX for 24 h (Fig. S2D). In addition, silencing of CDK2 also markedly repressed PARP cleavage in response to DOX treatment in H9c2 cells (Fig. S2E).

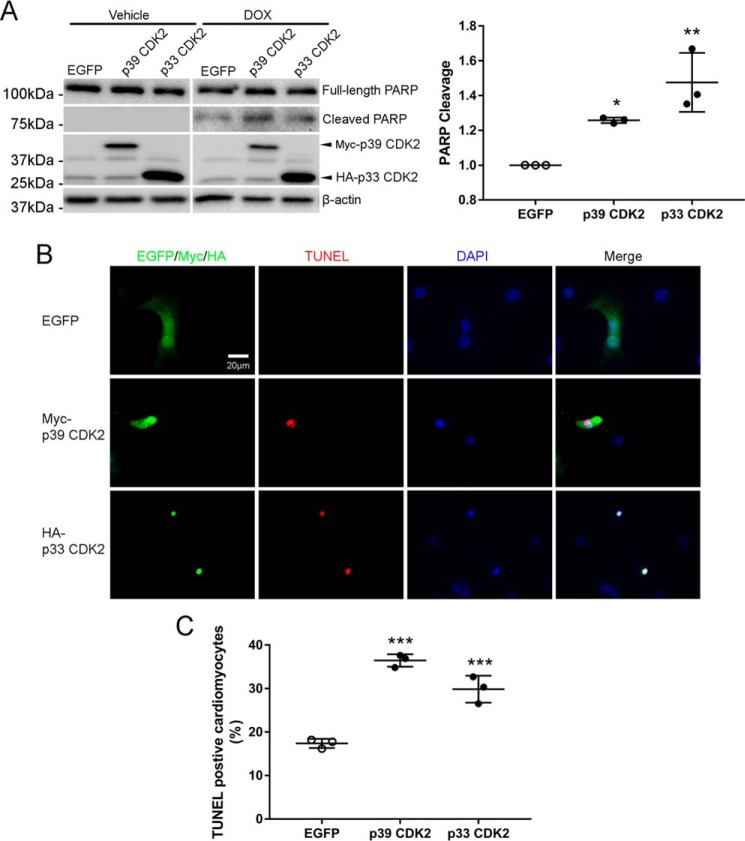

Overexpression of CDK2 accelerated DOX-induced apoptosis

To determine whether activation of CDK2 would augment DOX-induced apoptosis, NRCMs were transfected with plasmids expressing p33 or p39 CDK2 prior to treatment with DOX for 8 h. Overexpression of both isoforms of CDK2 significantly enhanced DOX-induced PARP cleavage (Fig. 4A). It is noteworthy that overexpression of CDK2 did not spontaneously induce apoptosis in the absence of DOX, suggesting that CDK2 is necessary but not sufficient for DOX-induced apoptosis. In agreement with these findings, immunofluorescent staining revealed that exogenous p39 or p33 CDK2 frequently colocalized with TUNEL signals (Fig. 4B), indicating that cells with high CDK2 levels were more sensitive to DOX-induced apoptosis. Indeed, overexpression of CDK2 in NRCMs significantly increased TUNEL-positive nuclei following DOX treatment (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of CDK2 accelerated DOX-induced apoptosis. NRCMs were transfected with EGFP, Myc-p39 CDK2, or HA-p33 CDK2 before treatment with DOX (1 μm) for 0 or 8 h (n = 3). A, cell lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies, with GAPDH as a loading control. B, immunofluorescence staining for Myc or HA tags (green) and nuclei (DAPI, blue) in NRCMs treated with DOX (1 μm) for 8 h. Apoptosis was evaluated by TUNEL staining (red). Exogenous p39 CDK2- or p33 CDK2-expressing cells, but not EGFP-expressing cells, frequently stained positive for the TUNEL signal. C, quantification of TUNEL-positive cardiomyocytes revealed that ectopic expression of p39 or p33 CDK2 accelerated DOX-induced apoptosis (n = 3). Data are mean ± S.D. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 versus EGFP.

DOX induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through up-regulation of Bim

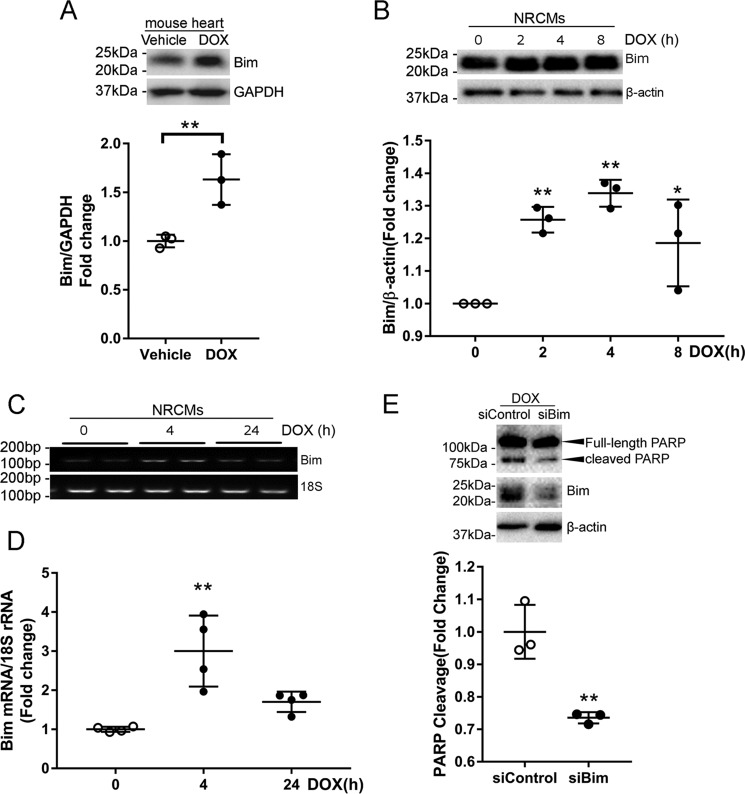

It has been shown that myocardial ischemia–induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis is mediated by the pro-apoptotic BH3-only protein Bim (18). To determine whether Bim is involved in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, we first examined Bim expression in the mouse heart following DOX injection. Western blotting revealed that injection of DOX at 5 mg/kg (Fig. 5A) or 20 mg/kg (Fig. S3) significantly increased the protein level of Bim. Similarly, NRCMs treated with DOX also exhibited an increase in Bim expression (Fig. 5B). Up-regulation of Bim protein was accompanied by an increase in Bim mRNA abundance (Fig. 5, C and D), indicating that DOX treatment likely enhanced transcription of Bim. To test whether Bim mediates DOX-induced apoptosis, NRCMs were transfected with Bim siRNAs prior to challenge with DOX. As shown in Fig. 5E, silencing of Bim markedly reduced PARP cleavage, suggesting that Bim is necessary for DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis.

Figure 5.

DOX induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through up-regulation of Bim. A, mice were sacrificed 24 h after DOX injection (5 mg/kg, i.p., n = 3/group), and Bim expression was examined by Western blotting. Results are mean ± S.D. and analyzed by two-tailed Student's t test. **, p < 0.01. B, NRCMs were treated with DOX (1 μm) for various periods of time (n = 3). Cell lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies, with β-actin as a loading control. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 versus time 0. C and D, NRCMs were treated with DOX (1 μm) for 0, 4, or 24 h (n = 3–4/time point). Bim transcript levels were analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR (C) and qRT-PCR (D). One-way ANOVA with Tukey test; **, p < 0.01 versus Time 0. E, NRCMs were transfected with control or Bim siRNAs (100 nm) twice prior to treatment with DOX (1 μm) for 24 h (n = 3). **, p < 0.01 versus siControl.

DOX-induced Bim expression depended on CDK2 activation

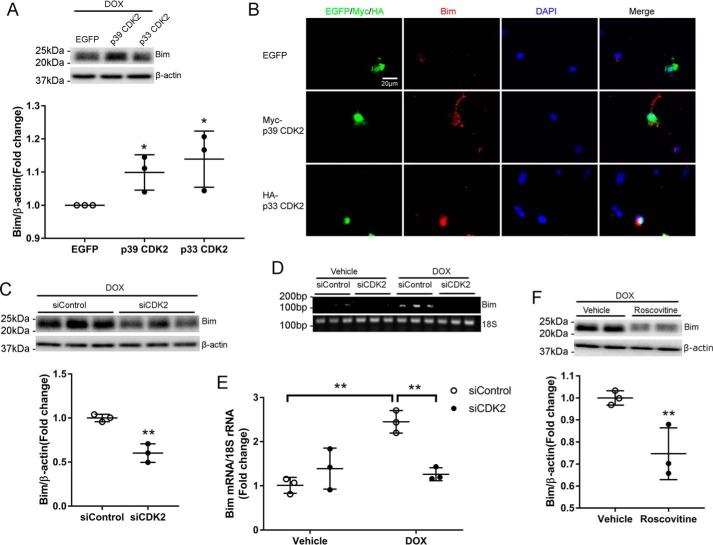

We reported previously that Bim expression was repressed by overexpression of the CDK inhibitor p21 (7), but the mechanisms remain unclear. Intriguingly, overexpression of p39 or p33 CDK2 significantly increased the protein level of Bim in response to DOX treatment (Fig. 6A). Immunofluorescent staining further revealed that the Bim signal intensity was strongly enhanced by ectopic expression of both isoforms of CDK2 (Fig. 6B). To determine whether CDK2 is necessary for DOX-induced Bim expression, NRCMs were transfected with CDK2 siRNA prior to treatment with DOX for 4 h. Knockdown of CDK2 significantly reduced the protein level of Bim (Fig. 6C). Semiquantitative and quantitative RT-PCR both revealed that DOX-induced up-regulation of Bim mRNA was almost completely abolished by CDK2 depletion (Fig. 6, D and E), indicating that CDK2 is likely necessary for DOX-induced Bim transcription. Moreover, pharmacologic inhibition of CDK2 activity with roscovitine significantly reduced the Bim protein level following DOX treatment (Fig. 6F), further supporting a critical role of CDK2 activation in DOX-induced expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bim.

Figure 6.

DOX-induced Bim expression depended on CDK2 activation. A and B, NRCMs were transfected with EGFP, Myc-p39 CDK2, or HA-p33 CDK2 before treatment with DOX (1 μm) for 8 h (n = 3). A, Bim protein level was evaluated by Western blotting. One-way ANOVA with Tukey test; *, p < 0.05 versus EGFP. B, immunofluorescence staining for Myc or HA tags (green), Bim (red), and nuclei (DAPI, blue). Exogenous p39 CDK2- or p33 CDK2-expressing cells exhibited stronger Bim immunoreactivity than EGFP-expressing cells or nontransfected cells. C, NRCMs were transfected with siControl or siCDK2 prior to treatment with DOX (1 μm) for 24 h (n = 3). Cell lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies, with β-actin as a loading control. Two-tailed Student's t test. **, p < 0.01 versus siControl. D and E, Bim mRNA levels were evaluated using semiquantitative RT-PCR (D) and qRT-PCR (E) in NRCMs transfected with siCDK2, followed by treatment with DOX (1 μm) for 4 h (n = 3). Two-way ANOVA with Sidak test. **, p < 0.01. F, NRCMs were treated with DOX (1 μm) for 4 h in the presence of the CDK inhibitor roscovitine (50 μm, n = 3). Cell lysates were immunoblotted using the indicated antibodies. Two-tailed Student's t test; **, p < 0.01 versus vehicle.

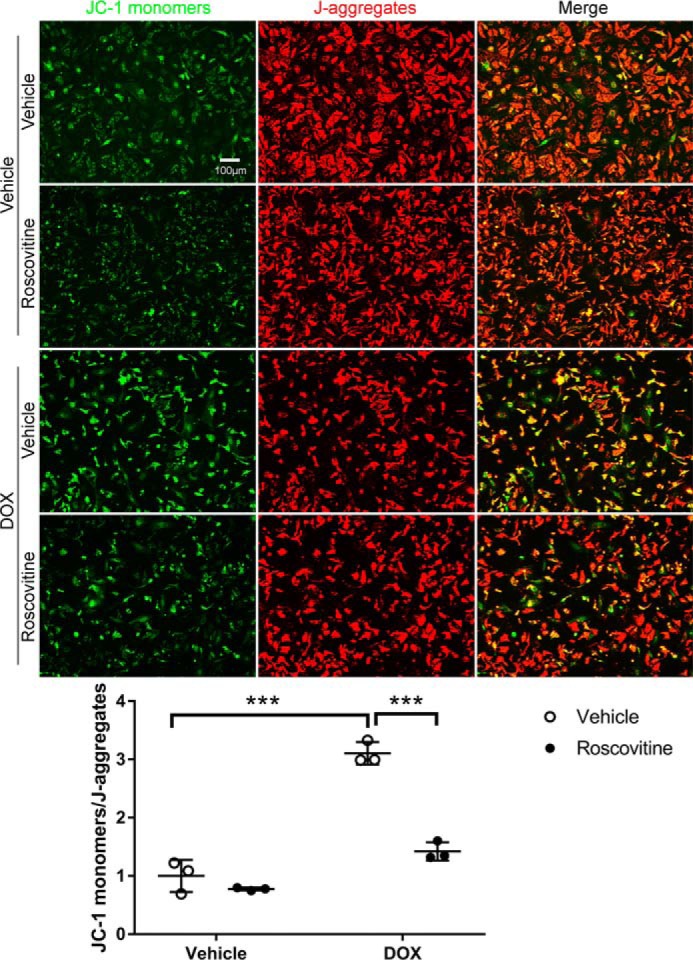

Inhibition of CDK2 with roscovitine suppressed DOX-induced mitochondrial damage

It is known that Bim mediates mitochondrial depolarization in a variety of cell types (19). To determine whether CDK2-dependent expression of Bim results in mitochondrial dysfunction, NRCMs were treated with DOX for 48 h in the presence of the CDK inhibitor roscovitine. The mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) was then evaluated by staining with JC-1, which enters energized mitochondria and forms aggregates (red fluorescence) in healthy cells but remains in monomeric form (green fluorescence) in cells with low ΔΨm. Mitochondrial depolarization, calculated as the ratio of green to red fluorescence intensity, was robustly induced by DOX stimulation (Fig. 7). Interestingly, pretreatment with roscovitine markedly suppressed DOX-induced mitochondrial depolarization (Fig. 7), suggesting that pharmacologic inhibition of CDK2 preserved mitochondrial integrity in response to DOX treatment, likely by repressing Bim expression.

Figure 7.

Inhibition of CDK2 with roscovitine suppressed DOX-induced mitochondrial damage. NRCMs were pretreated with the CDK inhibitor roscovitine (50 μm) for 1 h prior to incubation with DOX (1 μm) for 48 h (n = 3). Cells were then stained with JC-1 reagent to evaluate ΔΨm. Healthy mitochondria appear red (J-aggregates), and damaged mitochondria appear green (JC-1 monomers). Quantitative analysis of the JC-1 monomer/J-aggregate ratio revealed that roscovitine robustly suppressed DOX-induced mitochondrial depolarization. Results represent mean ± S.D. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak test; ***, p < 0.001.

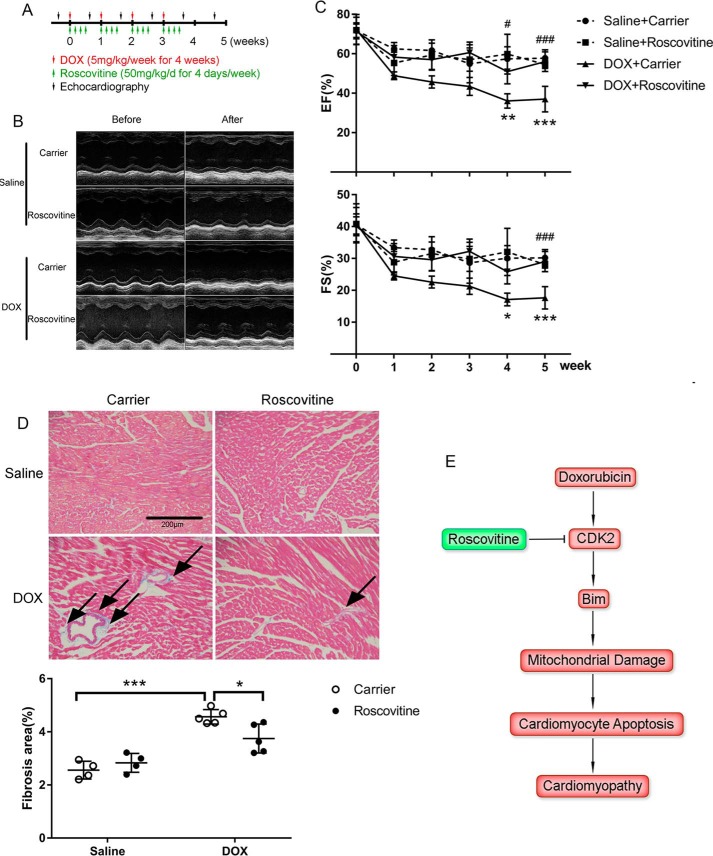

CDK2 inhibition protected against DOX-induced cardiomyopathy

To determine whether pharmacologic inhibition of CDK2 attenuates DOX-induced cardiomyopathy, mice received i.p. injections of DOX (5 mg/kg/week for 4 weeks) to induce chronic cardiotoxicity as well as an initial roscovitine injection (50 mg/kg/day) on the same day with DOX, followed by 3 more daily maintenance injections (Fig. 8A). In agreement with previous findings (11, 14), DOX injection induced a progressive decline in ejection fraction and fractional shortening (Fig. 8, B and C). In contrast, left ventricular systolic function in roscovitine-treated animals was preserved after chronic DOX administration. DOX-induced myocardial fibrosis was also suppressed by roscovitine (Fig. 8D). Compared with vehicle groups, long-term DOX injection significantly reduced body weight, which, however, was not altered by roscovitine treatment (Fig. S4). In summary, administration of the CDK inhibitor roscovitine alleviated DOX-induced cardiac dysfunction and ventricular remodeling.

Figure 8.

CDK2 inhibition protected against DOX-induced cardiomyopathy. A, experimental protocol. Chronic DOX cardiotoxicity was induced by weekly serial injections of DOX (5 mg/kg, i.p.) for 4 weeks (total cumulative dose, 20 mg/kg) with saline as a control. For each 4-week series, roscovitine (50 mg/kg/day, i.p.) or a carrier solution control was administered 1 h before either DOX or saline and for the next 3 consecutive days. Animals were randomized into four groups: saline+carrier, n = 4; saline+roscovitine, n = 4; DOX+carrier, n = 5; DOX+roscovitine, n = 5. B and C, heart function was assessed weekly using echocardiography. B, representative short-axis echocardiograms before initial DOX injection and at the end of the study. C, ventricular systolic function was preserved in roscovitine-treated mice compared with the carrier group following DOX injection. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 DOX+carrier versus saline+carrier; #, p < 0.05; ###, p < 0.001 DOX+roscovitine versus DOX+carrier. D, myocardial fibrosis was evaluated by Masson trichrome staining. DOX-induced collagen accumulation (blue, arrows) was significantly attenuated by roscovitine. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak test; *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. E, schematic summary of the role of CDK2 in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity. DOX treatment induces CDK2-dependent Bim expression, leading to mitochondrial damage, cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and, eventually, ventricular dysfunction. Pharmacologic inhibition of CDK2 suppresses DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

Discussion

Loss of cardiomyocytes because of apoptosis has been suggested as a major cause of cardiomyopathy and heart failure in cancer patients who have received anthracycline antineoplastic agents (3–5). In this study, we demonstrated that the anthracycline DOX induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through activation of CDK2, which mediated expression of the pro-apoptotic protein Bim, resulting in mitochondrial depolarization and ventricular systolic dysfunction (Fig. 8E). This is the first study to identify CDK2 as a critical mediator of DOX-induced cardiotoxicity.

Cyclin–CDK complexes are best known for regulating cell cycle progression and cell proliferation. Specifically, CDK2 activity remains high throughout S phase; it binds to cyclin E to trigger G1/S transition and pairs with cyclin A to regulate S phase progression and completion. Although adult mammalian cardiomyocytes are traditionally viewed as post-mitotic cells with minimal cell cycle activity, recent evidence revealed that the majority of human cardiomyocytes undergo active DNA synthesis, a hallmark of cell cycle S phase, to become polyploid until the third decade of life (20, 21). Moreover, myocardial infarction triggered adult cardiomyocyte cell cycle reentry and resulted in extensive DNA synthesis (10). These findings suggest that CDK2, the primary driver of G1/S transition, is likely still functional in the adult heart and may have promising potential to be harnessed to promote cardiomyocyte proliferation and myocardial regeneration following cardiac injury. Indeed, heart-specific overexpression of CDK2 resulted in a more than 100-fold increase in bromodeoxyuridine-labeled nuclei and a 5-fold increase in the proportion of mononuclear cardiomyocytes (22). Interestingly, overexpression of CDK2 induced concomitant expression of cyclin E and cyclin A through an unknown mechanism (22). Moreover, cardiomyocyte-specific transgenic expression of cyclin A induced postnatal mitosis and significant heart hyperplasia after 6 months of age (23). Delivery of a cyclin A adenovirus into an infarcted porcine heart improved cardiac contractile function, which was associated with cardiomyocyte regeneration through cytokinesis (24). Collectively, these studies suggest that elevated CDK2 activity provokes DNA synthesis and cell cycle reactivation in cardiomyocytes.

Compared with the large amount of information about cardiomyocyte cell cycle progression, much less is known regarding the role of cyclin–CDK complexes in apoptotic death of cardiomyocytes. Somewhat surprisingly, up-regulation of cyclins and CDKs was associated with both myocardial regeneration and apoptosis in failing hearts in mice and humans (25). The pro-apoptotic role of CDK2 was more directly shown in cardiomyocytes exposed to hypoxia, which increased cyclin A–CDK2 activity and induced apoptosis (26). Further studies revealed that hypoxia-induced apoptosis was enhanced by overexpression of cyclin A but attenuated by dominant-negative CDK2 (26). Mechanistically, CDK2 mediated hypoxia-induced apoptosis by hyperphosphorylation and inactivation of retinoblastoma protein (RB1), leading to derepression of E2F-dependent transcription of pro-apoptotic genes, including caspase 3 and caspase 7 (27, 28). In this study, we showed that DOX treatment induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through CDK2 activation. Our data are in agreement with most recent findings that activation of CDK2 by the DNA-damaging anticancer drug cisplatin results in cochlear cell apoptosis and hearing loss in rodents (29). Taken together, these findings suggested that CDK2 inhibition may have broad therapeutic applications against cancer treatment–related normal tissue toxicity.

The pro-apoptotic roles of both CDK2 isoforms in our study were supported by previous findings that the p39 isoform, produced through alternative splicing, exhibited similar cellular functions as p33 CDK2, albeit with ∼50% lower activity (30). Recent evidence suggests that the two CDK2 isoforms differ in their binding partners and expression patterns (31). Indeed, DOX treatment induced a transient increase in p33 and prolonged expression of p39 in cardiomyocytes. One potential mechanism underlying DOX-induced CDK2 activation is through checkpoint kinase 1 (Chk1)–dependent phosphorylation of CDK2 at Thr-160 (12). Second, caspase activity has been shown to be necessary for CDK2 activation during apoptosis, hypothetically via proteolytic destruction of CDK-inhibitory regulators (32). Finally, we demonstrated previously that long-term DOX treatment results in proteasomal degradation of the CDK inhibitor p21 (7), which may potentially contribute to CDK2 activation as well.

By using both loss- and gain-of-function approaches, we convincingly showed that CDK2 activation is necessary for DOX-induced transcriptional up-regulation of the pro-apoptotic BCL2 family member Bim. Potential transcription factors involved in Bim expression may include FOXO1 (33), which has been shown to be phosphorylated by CDK2 at Ser-249 (34). The mechanisms of Bim-dependent apoptosis initiation remain subjects for active investigation. It has been shown that the BH3-only proteins, including Bid, Bim, and Puma, mediate Bax/Bak homo-oligomerization, resulting in mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and, thereby, cytochrome c–dependent activation of caspases (35). The pro-apoptotic functions of BH3-only proteins are nonredundant, with Bim preferentially activating Bax and Bid preferentially activating Bak (19). A recent study suggested that the BH3-only proteins initiate mitochondrial apoptosis not through direct activation of Bax/Bak but by interacting and neutralizing the anti-apoptotic BCL2 family members Bcl-xL and Mcl-1, allowing Bax/Bak to be released and become activated (36).

A major concern for all cardioprotective strategies against chemotherapy toxicity is the potential of interfering with the antitumor activity. Although our data suggested that genetic or pharmacologic inhibition of CDK2 attenuated DOX-induced cardiotoxicity, the same strategy has been shown to potentiate DOX anticancer efficacy in a variety of cancer cell lines by hindering DNA repair (37), inducing autophagy (38), or triggering apoptosis (39). Compared with DOX alone, combined treatment with roscovitine and DOX significantly reduced tumor volume and improved survival in breast cancer xenograft models (17, 40). In addition to roscovitine, synergistic antitumor activity has also been observed between DOX and additional CDK inhibitors (41–43). Taken together, these findings suggest that inhibition of CDK2 could be a promising strategy to synergistically enhance the antitumor efficacy of DOX and concomitantly alleviating DOX-related cardiotoxicity.

In summary, our study identified CDK2 activation as a critical mechanism underlying DOX-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and ventricular dysfunction. The pro-apoptotic effect of CDK2 was associated with elevated cellular levels of the BH3-only protein Bim through enhanced transcription. These results suggest that pharmacologic inhibition of CDK2 could represent a novel strategy in clinical management of cancer treatment–related cardiotoxicity.

Experimental procedures

Animals

C57BL/6 mice and Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Envigo and were housed in the campus vivarium accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Washington State University and conformed to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition, 2011).

Neonatal rat cardiomyocyte isolation and H9c2 cell culture

NRCMs were isolated from 2- to 4-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats using a neonatal cardiomyocyte isolation system (Worthington Biochemical Corp.) as described previously (7). In brief, animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, and heart tissue was digested in 50 μg/ml trypsin at 4 °C overnight, followed by 100 units/ml collagenase at 37 °C for 45 min to release cardiomyocytes. Cells were plated on 0.2% gelatin-coated dishes in medium 199 supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin, and bromodeoxyuridine (100 μm) to eliminate proliferating nonmyocytes. After 24 h, cells were washed with PBS twice and serum-starved prior to transfection or drug treatment. H9c2 cells were purchased from the ATCC (CRL-1446) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.5% penicillin/streptomycin.

Plasmid and siRNA transfection

NRCMs were transfected with EGFP, Myc-p39 CDK2 (Origene, MR205214), or HA-p33 CDK2 (Addgene, 1884) plasmids using TransIT-LT1 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio) or specific siRNAs using HiPerfect transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturers' instructions. H9c2 cells were transfected with siRNAs in serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium using DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon). The siRNA sequences used were as follows: CDK2 siRNA, GGUGAAAGACACUUGAAUU[dT][dT]; Bim siRNA, UGAGACUUACACGAGGAGG[dT][dT]; control siRNA, UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUAC[dT][dT] or GGUGCGCUCCUGGACGUAGCC[dT][dT].

Western blotting

Protein lysates were extracted from cultured cells using radioimmune precipitation assay buffer supplemented with 1% protease inhibitor and 1% phosphatase inhibitor (Thermo Scientific), electrophoresed through SDS-polyacrylamide gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and blotted with the following antibodies: rabbit anti-phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160, Cell Signaling Technology, 2561, 1:1000), rabbit anti-CDK2 (sc-163, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000), rabbit anti-PARP (9542, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), rabbit anti-caspase 3 (9662, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:500), rabbit anti-Bim (2933, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:1000), rabbit anti-GAPDH (sc-25778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000), and mouse anti-β-actin (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:1000).

Immunofluorescence and TUNEL staining

Mouse heart paraffin sections were subjected to antigen retrieval in 10 mmol/liter citrate (pH 6.0). Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with freshly made permeabilization solution (0.1 m glycine and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS), and incubated with the following antibodies at 4 °C overnight: rabbit anti-Bim (2933, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:50), mouse anti-cardiac Troponin T (MS-295-P, Thermo Scientific, 1:100), rabbit anti-CDK2 (sc-163, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:50), rabbit anti-phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160, sc-101656, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:50), rabbit anti-phospho-CDK2 (Thr-160, Abcam, ab194868, 1:50), mouse anti-Myc (2276, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:100), and mouse anti-HA (sc-7392, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 1:50). TUNEL staining was performed using an in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

In vitro CDK2 kinase assay

NRCMs were lysed in ice-cold radioimmune precipitation assay base buffer (50 mm HEPES, 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 1% Nonidet P-40 (pH 7.2)) supplemented with Halt protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Thermo). Protein lysates were immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-CDK2 (sc-6248, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using Dynabeads protein G (Thermo). The immunoprecipitates were then incubated with native histone H1 substrate and ATP in reaction buffer (40 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 20 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and 50 μm DTT) at room temperature for 10 min, and kinase activity was examined with the ADP-Glo kinase assay kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For the cell-free kinase assay, the CDK2/cyclin A2 kinase enzyme system (Promega), composed of recombinant full-length human CDK2/cyclin A2, histone H1 substrate, and ATP, was incubated with the indicated concentrations of DOX, and kinase activity was again assessed with the ADP-Glo kinase assay kit.

EdU incorporation assay

Cells were incubated with EdU (10 μm) for 1 h, fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100, and stained with the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 imaging kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nuclei were labeled with Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/ml). EdU incorporation was visualized using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica).

Cell cycle analysis

Cells were trypsinized, fixed with cold 70% ethanol, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and stained with 7-amino-actinomycin D (1 μg/ml) for 30 min on ice. Cellular DNA content was measured using a Beckman Coulter Gallios flow cytometer, and the cell cycle profile was analyzed with Kaluza software.

Cell viability assay

NRCMs plated at 50,000 cells/well in a 96-well plate were transfected with specific siRNAs or pretreated with the indicated pharmacological inhibitors prior to treatment with DOX as indicated. Cell viability was assessed using Cell Proliferation Kit I (MTT, Roche), and absorbance at 562 nm was measured using a Synergy NEO microplate reader (Biotek).

Semiquantitative RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells using the E.Z.N.A. Total RNA Kit I (Omega Bio-tek), and 500 ng of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into single-stranded cDNA using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). For semiquantitative PCR reactions, 50 ng of cDNA per reaction was subjected to the following programs: (18 cycles) 94 °C 30 s, 58 °C 30 s, 72 °C 20 s for 18S rRNA; (26 cycles) 94 °C 30 s, 55 °C 30 s, 72 °C 20 s for Bim. Quantitative PCR was performed using Maxima SYBR Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) with 18S rRNA as an internal control. Primer sequences were as follows: Bim, 5′-CCATGAGTTGTGACAAGTCAACAC-3′ and 5′-GATCTTCAGGTTCCTCCTGAGACTG-3′; p33 CDK2, 5′-CATCTTTGCCGAAATGGTGACC-3′ and 5′-TGGCCAAACCACCTCATCTG-3′; p39 CDK2, 5′-CATCTTTGCCGAAATGCACCTAG-3′ and 5′-TCCTTGTGATGCAGCCACTTC-3′; 18S rRNA, 5′-TGACTCAACACGGGAAACCTCAC-3′ and 5′-ATCGCTCCACCAACTAAGAACGG-3′.

Subcellular fractionation

Subcellular fractionation was carried out as described previously (7). Briefly, cells were collected in isolation buffer (190 mm D-mannitol, 70 mm sucrose, 20 mm HEPES, and 0.2 mm EDTA) and homogenized in a glass Teflon homogenizer. The nuclear fraction was separated by centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min, and the cytosolic fraction was obtained by recentrifugation of the supernatant at 20,000 × g for 60 min.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential

ΔΨm was assessed using the JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential assay kit (Cayman Chemical). Following incubation with JC-1, healthy mitochondria with high ΔΨm appeared red (color of J-aggregates), and damaged mitochondria with low ΔΨm appeared green (color of JC-1 monomers). Loss of ΔΨm was defined as an increase in the fluorescence intensity ratio of JC-1 monomers to J-aggregates.

In vivo studies

For the chronic DOX cardiotoxicity model, 8- to 12-week-old male C57BL/6 mice received weekly injections of DOX (5 mg/kg, i.p., LC Laboratories) for 4 weeks to reach a cumulative dose of 20 mg/kg as described previously (11), with an equal volume of saline as a control. Roscovitine was first dissolved in DMSO at 500 mg/ml and then diluted to 25 mg/ml in a carrier solution containing 10% Tween 80, 20% N-N-dimethylacetamide, and 70% PEG 400. Roscovitine (50 mg/kg/day, i.p., LC Laboratories) or carrier solution was administered for 4 consecutive days/week for 4 weeks based on a previous study (17). Animals were randomized to receive saline + carrier, saline + roscovitine, DOX + carrier, or DOX + roscovitine. For each week, DOX was administered 1 h after the first roscovitine injection. Weekly echocardiography was performed before and after DOX injection throughout the study period using the VisualSonics VEVO 2100 imaging system equipped with a 55-MHz MS550S transducer. Animals were euthanized via CO2 inhalation 2 weeks after the last DOX injection. Myocardial fibrosis was stained with Masson trichrome (Sigma, HT10516) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For molecular and cellular analyses, a separate cohort of mice was sacrificed 24 h after injection of DOX (5 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg, i.p.).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 7.02. All data are expressed as mean values ± S.D. Statistical comparisons between two groups were performed using two-tailed Student's t test. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post hoc test or two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak test was used for multiple group comparisons as appropriate. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author contributions

P. X., Y. L., J. C., S. C., and Z. C. formal analysis; P. X., Y. L., J. C., S. C., and Z. C. investigation; P. X., Y. L., and Z. C. methodology; P. X. and Z. C. writing-original draft; D. X. L. resources; D. X. L. and Z. C. supervision; D. X. L. and Z. C. writing-review and editing; Z. C. conceptualization; Z. C. funding acquisition; Z. C. project administration.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Joan M. Taylor (University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) for critical reading of the manuscript and Ze Liu (Flow Cytometry Core, WSU) for technical assistance.

This work was supported by NHLBI, National Institutes of Health Grant R00HL119605 (to Z. C.) and the Washington State University College of Pharmacy. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This article contains Figs. S1–S4 and Table S1.

- DOX

- doxorubicin

- CDK

- cyclin-dependent kinase

- NRCM

- neonatal rat cardiomyocyte

- TUNEL

- terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling

- PARP

- poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- EdU

- 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- i.p.

- intraperitoneal(ly)

- cDNA

- complementary DNA

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- DAPI

- 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- cTnT

- cardiac troponin T

- HA

- hemagglutinin.

References

- 1. Miller K. D., Siegel R. L., Lin C. C., Mariotto A. B., Kramer J. L., Rowland J. H., Stein K. D., Alteri R., and Jemal A. (2016) Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J. Clin. 66, 271–289 10.3322/caac.21349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lenneman C. G., and Sawyer D. B. (2016) Cardio-oncology: an update on cardiotoxicity of cancer-related treatment. Circ. Res. 118, 1008–1020 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang S., Liu X., Bawa-Khalfe T., Lu L. S., Lyu Y. L., Liu L. F., and Yeh E. T. (2012) Identification of the molecular basis of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Nat. Med. 18, 1639–1642 10.1038/nm.2919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pang B., Qiao X., Janssen L., Velds A., Groothuis T., Kerkhoven R., Nieuwland M., Ovaa H., Rottenberg S., van Tellingen O., Janssen J., Huijgens P., Zwart W., and Neefjes J. (2013) Drug-induced histone eviction from open chromatin contributes to the chemotherapeutic effects of doxorubicin. Nat. Commun. 4, 1908 10.1038/ncomms2921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ichikawa Y., Ghanefar M., Bayeva M., Wu R., Khechaduri A., Naga Prasad S. V., Mutharasan R. K., Naik T. J., and Ardehali H. (2014) Cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin is mediated through mitochondrial iron accumulation. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 617–630 10.1172/JCI72931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xia P., Liu Y., and Cheng Z. (2016) Signaling pathways in cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 9583268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cheng Z., DiMichele L. A., Rojas M., Vaziri C., Mack C. P., and Taylor J. M. (2014) Focal adhesion kinase antagonizes doxorubicin cardiotoxicity via p21(Cip1.). J Mol. Cell Cardiol. 67, 1–11 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abbas T., and Dutta A. (2009) p21 in cancer: intricate networks and multiple activities. Nat. Rev. Cancer 9, 400–414 10.1038/nrc2657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Malumbres M. (2014) Cyclin-dependent kinases. Genome Biol. 15, 122 10.1186/gb4184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Senyo S. E., Steinhauser M. L., Pizzimenti C. L., Yang V. K., Cai L., Wang M., Wu T. D., Guerquin-Kern J. L., Lechene C. P., and Lee R. T. (2013) Mammalian heart renewal by pre-existing cardiomyocytes. Nature 493, 433–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li D. L., Wang Z. V., Ding G., Tan W., Luo X., Criollo A., Xie M., Jiang N., May H., Kyrychenko V., Schneider J. W., Gillette T. G., and Hill J. A. (2016) Doxorubicin blocks cardiomyocyte autophagic flux by inhibiting lysosome acidification. Circulation 133, 1668–1687 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.017443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bourke E., Brown J. A., Takeda S., Hochegger H., and Morrison C. G. (2010) DNA damage induces Chk1-dependent threonine-160 phosphorylation and activation of Cdk2. Oncogene 29, 616–624 10.1038/onc.2009.340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flores O., Wang Z., Knudsen K. E., and Burnstein K. L. (2010) Nuclear targeting of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 reveals essential roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 localization and cyclin E in vitamin D-mediated growth inhibition. Endocrinology 151, 896–908 10.1210/en.2009-1116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jay S. M., Murthy A. C., Hawkins J. F., Wortzel J. R., Steinhauser M. L., Alvarez L. M., Gannon J., Macrae C. A., Griffith L. G., and Lee R. T. (2013) An engineered bivalent neuregulin protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity with reduced proneoplastic potential. Circulation 128, 152–161 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kruman I. I., Wersto R. P., Cardozo-Pelaez F., Smilenov L., Chan S. L., Chrest F. J., Emokpae R. Jr, Gorospe M., and Mattson M. P. (2004) Cell cycle activation linked to neuronal cell death initiated by DNA damage. Neuron 41, 549–561 10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00017-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ling Y. H., el-Naggar A. K., Priebe W., and Perez-Soler R. (1996) Cell cycle-dependent cytotoxicity, G2/M phase arrest, and disruption of p34cdc2/cyclin B1 activity induced by doxorubicin in synchronized P388 cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 49, 832–841 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jabbour-Leung N. A., Chen X., Bui T., Jiang Y., Yang D., Vijayaraghavan S., McArthur M. J., Hunt K. K., and Keyomarsi K. (2016) Sequential combination therapy of CDK inhibition and doxorubicin is synthetically lethal in p53-mutant triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 15, 593–607 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Qian L., Van Laake L. W., Huang Y., Liu S., Wendland M. F., and Srivastava D. (2011) miR-24 inhibits apoptosis and represses Bim in mouse cardiomyocytes. J. Exp. Med. 208, 549–560 10.1084/jem.20101547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sarosiek K. A., Chi X., Bachman J. A., Sims J. J., Montero J., Patel L., Flanagan A., Andrews D. W., Sorger P., and Letai A. (2013) BID preferentially activates BAK while BIM preferentially activates BAX, affecting chemotherapy response. Mol. Cell 51, 751–765 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mollova M., Bersell K., Walsh S., Savla J., Das L. T., Park S. Y., Silberstein L. E., Dos Remedios C. G., Graham D., Colan S., and Kühn B. (2013) Cardiomyocyte proliferation contributes to heart growth in young humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1446–1451 10.1073/pnas.1214608110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bergmann O., Zdunek S., Felker A., Salehpour M., Alkass K., Bernard S., Sjostrom S. L., Szewczykowska M., Jackowska T., Dos Remedios C., Malm T., Andrä M., Jashari R., Nyengaard J. R., Possnert G., et al. (2015) Dynamics of cell generation and turnover in the human heart. Cell 161, 1566–1575 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liao H. S., Kang P. M., Nagashima H., Yamasaki N., Usheva A., Ding B., Lorell B. H., and Izumo S. (2001) Cardiac-specific overexpression of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 increases smaller mononuclear cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 88, 443–450 10.1161/01.RES.88.4.443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chaudhry H. W., Dashoush N. H., Tang H., Zhang L., Wang X., Wu E. X., and Wolgemuth D. J. (2004) Cyclin A2 mediates cardiomyocyte mitosis in the postmitotic myocardium. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35858–35866 10.1074/jbc.M404975200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shapiro S. D., Ranjan A. K., Kawase Y., Cheng R. K., Kara R. J., Bhattacharya R., Guzman-Martinez G., Sanz J., Garcia M. J., and Chaudhry H. W. (2014) Cyclin A2 induces cardiac regeneration after myocardial infarction through cytokinesis of adult cardiomyocytes. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 224ra27 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sarkar S., Chawla-Sarkar M., Young D., Nishiyama K., Rayborn M. E., Hollyfield J. G., and Sen S. (2004) Myocardial cell death and regeneration during progression of cardiac hypertrophy to heart failure. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52630–52642 10.1074/jbc.M402037200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adachi S., Ito H., Tamamori-Adachi M., Ono Y., Nozato T., Abe S., Ikeda M., Marumo F., and Hiroe M. (2001) Cyclin A/cdk2 activation is involved in hypoxia-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 88, 408–414 10.1161/01.RES.88.4.408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hauck L., Hansmann G., Dietz R., and von Harsdorf R. (2002) Inhibition of hypoxia-induced apoptosis by modulation of retinoblastoma protein-dependent signaling in cardiomyocytes. Circ. Res. 91, 782–789 10.1161/01.RES.0000041030.98642.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liem D. A., Zhao P., Angelis E., Chan S. S., Zhang J., Wang G., Berthet C., Kaldis P., Ping P., and MacLellan W. R. (2008) Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 signaling regulates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 45, 610–616 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Teitz T., Fang J., Goktug A. N., Bonga J. D., Diao S., Hazlitt R. A., Iconaru L., Morfouace M., Currier D., Zhou Y., Umans R. A., Taylor M. R., Cheng C., Min J., Freeman B., et al. (2018) CDK2 inhibitors as candidate therapeutics for cisplatin- and noise-induced hearing loss. J. Exp. Med. 215, 1187–1203 10.1084/jem.20172246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ellenrieder C., Bartosch B., Lee G. Y., Murphy M., Sweeney C., Hergersberg M., Carrington M., Jaussi R., and Hunt T. (2001) The long form of CDK2 arises via alternative splicing and forms an active protein kinase with cyclins A and E. DNA Cell Biol. 20, 413–423 10.1089/104454901750361479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liu W., Wang L., Zhao W., Song G., Xu R., Wang G., Wang F., Li W., Lian J., Tian H., Wang X., and Sun F. (2014) Phosphorylation of CDK2 at threonine 160 regulates meiotic pachytene and diplotene progression in mice. Dev. Biol. 392, 108–116 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Harvey K. J., Lukovic D., and Ucker D. S. (2000) Caspase-dependent Cdk activity is a requisite effector of apoptotic death events. J. Cell Biol. 148, 59–72 10.1083/jcb.148.1.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gilley J., Coffer P. J., and Ham J. (2003) FOXO transcription factors directly activate bim gene expression and promote apoptosis in sympathetic neurons. J. Cell Biol. 162, 613–622 10.1083/jcb.200303026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang H., Regan K. M., Lou Z., Chen J., and Tindall D. J. (2006) CDK2-dependent phosphorylation of FOXO1 as an apoptotic response to DNA damage. Science 314, 294–297 10.1126/science.1130512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ren D., Tu H. C., Kim H., Wang G. X., Bean G. R., Takeuchi O., Jeffers J. R., Zambetti G. P., Hsieh J. J., and Cheng E. H. (2010) BID, BIM, and PUMA are essential for activation of the BAX- and BAK-dependent cell death program. Science 330, 1390–1393 10.1126/science.1190217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang J., Huang K., O'Neill K. L., Pang X., and Luo X. (2016) Bax/Bak activation in the absence of Bid, Bim, Puma, and p53. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2266 10.1038/cddis.2016.167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vella S., Tavanti E., Hattinger C. M., Fanelli M., Versteeg R., Koster J., Picci P., and Serra M. (2016) Targeting CDKs with roscovitine increases sensitivity to DNA damaging drugs of human osteosarcoma cells. PLoS ONE 11, e0166233 10.1371/journal.pone.0166233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lambert L. A., Qiao N., Hunt K. K., Lambert D. H., Mills G. B., Meijer L., and Keyomarsi K. (2008) Autophagy: a novel mechanism of synergistic cytotoxicity between doxorubicin and roscovitine in a sarcoma model. Cancer Res. 68, 7966–7974 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Raje N., Kumar S., Hideshima T., Roccaro A., Ishitsuka K., Yasui H., Shiraishi N., Chauhan D., Munshi N. C., Green S. R., and Anderson K. C. (2005) Seliciclib (CYC202 or R-roscovitine), a small-molecule cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, mediates activity via down-regulation of Mcl-1 in multiple myeloma. Blood 106, 1042–1047 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Appleyard M. V., O'Neill M. A., Murray K. E., Paulin F. E., Bray S. E., Kernohan N. M., Levison D. A., Lane D. P., and Thompson A. M. (2009) Seliciclib (CYC202, R-roscovitine) enhances the antitumor effect of doxorubicin in vivo in a breast cancer xenograft model. Int. J. Cancer 124, 465–472 10.1002/ijc.23938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Luke J. J., D'Adamo D. R., Dickson M. A., Keohan M. L., Carvajal R. D., Maki R. G., de Stanchina E., Musi E., Singer S., and Schwartz G. K. (2012) The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol potentiates doxorubicin efficacy in advanced sarcomas: preclinical investigations and results of a phase I dose-escalation clinical trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 2638–2647 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rathos M. J., Khanwalkar H., Joshi K., Manohar S. M., and Joshi K. S. (2013) Potentiation of in vitro and in vivo antitumor efficacy of doxorubicin by cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor P276–00 in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. BMC Cancer 13, 29 10.1186/1471-2407-13-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen Z., Wang Z., Pang J. C., Yu Y., Bieerkehazhi S., Lu J., Hu T., Zhao Y., Xu X., Zhang H., Yi J. S., Liu S., and Yang J. (2016) Multiple CDK inhibitor dinaciclib suppresses neuroblastoma growth via inhibiting CDK2 and CDK9 activity. Sci. Rep. 6, 29090 10.1038/srep29090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.