Abstract

Objective:

To examine the prevalence of obesity and related cardiovascular disease risk factors among Tibetan immigrants living in high altitude areas.

Research methods & procedures:

A total of 149 Tibetan immigrants aged 20 years and over were recruited in 2016 in Ladakh, India. Athropometric indices and biochemical factors were measured. Using the provided Asia-Pacific criteria from the World Health Organization, overweight and obese status were determined. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was defined according to the American Heart Association.

Results:

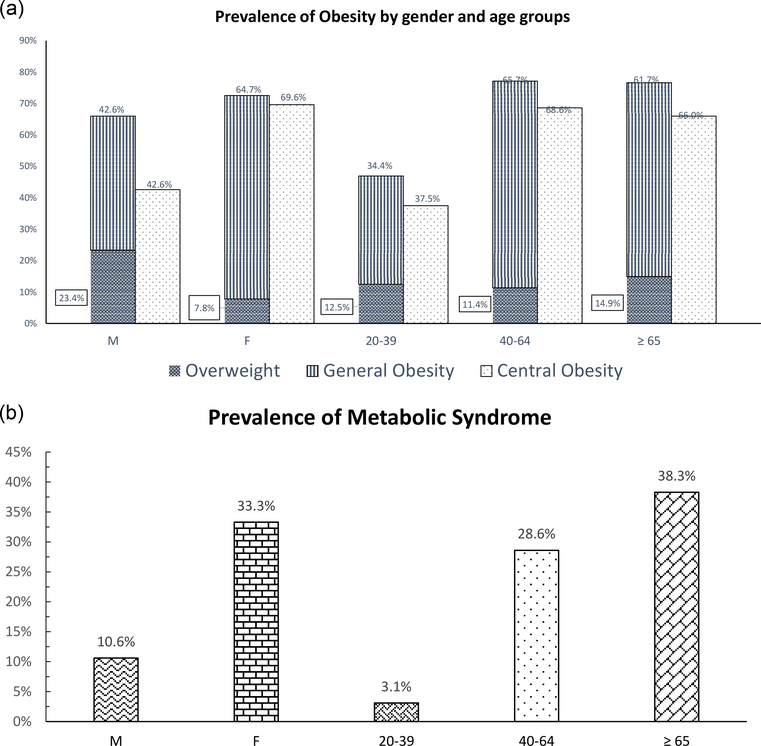

In general, men were older, taller, and had a greater amount of fasting glucose, and uric acid when compared to women. The prevalence of overweight, general obesity, and central obesity was 23.4, 42.6, and 42.6% in men and 7.8, 64.7, and 69.6% in women, respectively. The prevalence of MetS was 10.6% in men and 33.3% in women, respectively. In older subjects, the prevalence of obesity and MetS was found to be greater. In both genders, the prevalence of hypertension, central obesity, and MetS was significantly different among these body mass index (BMI) groups. Compared to the non-central obesity group, the central obesity group has higher weight, BMI, body fat, hip circumference, systolic and diastolic BP, and prevalence of hypertension No relationship was found between the prevalence of diabetes and fasting glucose and BMI groups or central obesity groups in both genders.

Conclusions:

Among this group of Tibetan immigrants living in high altitude areas, women have a higher prevalence of obesity and MetS than men. No relationship was found between diabetes and obesity.

Keywords: Tibetan, Immigrants, Obesity, High altitude, Ladakh

Introduction

One of the most challenging public health issues in the 21st century is obesity. According to an estimation from World Health Organization, more than half of the world’s adult population are either overweight or obese [1]. The mean body mass index (BMI) has dramatically increased in the past decades. The men’s mean BMI has risen from 21.7kg/m2 to 24.2kg/m2 in just 39 years from 1975 to 2014, while the women’has risen from 22.1kg/m2 to 24.4kg/m2 [2]. The prevalence of obesity has been found to have increased from 3.2% in 1975 to 10.8% in 2014 in men and from 6.4% to 14.9% in women [2]. Obesity is increasing in a surprisingly high rate. Obesity is important because it increases a variety of risks including diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and mortality [3,4].

People living in high altitude areas tend to be leaner when compared to those living in low altitude areas [5]. It has also been established that obesity is not as common in people who live in high altitude areas [5–7]. For example, Díaz-Gutierrez et al. found that the risk of developing obesity was inversely associated with the altitudes in Spain [7]. Sherpa et al. also found that low temperatures and low oxygen levels in high altitude area have a direct catabolic effect and that the total effect of altitude on BMI was −1.31kg/m2 per kilometre of altitude [8]. On the other hand, waist circumference (WC) had a direct relationship with the altitude (+0.85 cm per kilometre of altitude) [8]. Lower energy intake and increased physical activity do not explain this particular relationship. Many of the Tibetan immigrants emigrated due to political issues. Previous reports in the U.S. and U.K. showed that the immigrants were healthier and less obese than the natives [9–11]. But, once they arrive, they generally become more similar to the natives and grow to be less healthy and more obese, since they become accustomed to the indigenous diet and lifestyle [9,12]. For example, the amount of 3rd generation of Latino and Asian immigrants who were obese was significantly higher than the amount of those who were 1st or 2nd generation of immigrants [12]. Despite the reasons mentioned above, immigrants’ obesity rate seems to rise slower compared to the aboriginals’ [11]. Factors such as the difference in culture and altitude levels among the immigrants may influence the prevalence of obesity and related metabolic factors or chronic diseases. Ladakh is located in India next to the Karakoram in the northwest and the Himalayas in the southwest, which has an altitude of 3500 m. Many Tibetan immigrants have lived in Ladakh, which is one of the most remote regions in India for more than half a century. In this study, relationships of the prevalence of obesity and related metabolic diseases among Tibetan immigrants were investigated.

Materials and methods

Participant enrollment

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Sonamling Tibetan Settlement, Ladakh in August 2016. Sonamling Tibetan Settlement was established in 1969 and is made up of 12 camps which sums up to a total of nearly 7000 habitants [13]. The settlement is located in Choglamsar, 8 km from Leh city, Ladakh in Jammu & Kashmir State, India at a height of 3505 m above the sea level. The first people who settled there were refugees that fled from Tibet in 1960. Now, second and third generations live there. The first generation and elderly migrants have a low literacy rate, but the new generations have a literacy rate of 100% because of the education system in Tibetan Children Village School. Almost all of the settlers are practice Tibetan Buddhism. Tibetan refugees typically work in small businesses, restaurants, and labour work. There is only one health centre—Tibetan Primary Health Care Center (TPHCC), which is administered directly by the Department of Health and regulations of Central Tibetan Administration. TPHCC provides the basic primary care, such as health education, dental care, women health care, directly observed treatment, short course (DOTS) for tuberculosis and schedule vaccination.

The TPHCC conducted a health survey for the adults in Sonamling Settlement aged ≥20 years (mean age: 42.7 ± 17.9 years, 70.8% of all population), which consists of 48.8% men and 51.2% women. The staffs of TPHCC informed the settlement officers of each camp, who then invited the residents to participate in the health examination voluntarily. Due to the budget and time limitation, the capacity of health examination could be only offered for one twentieth of all population in 2016. 149 subjects (mean age 54.7 ± 16.7 years) agreed to participate in this study. There were more women (n = 102, 68.5%) in the screening participants than those in original population. A unique study ID was assigned to each participant and personal information according to “Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act” was not included for the present study.

Individual information about alcohol and tobacco consumption was obtained at health examination. Tobacco and alcohol consumption were defined as either current or previous. Those who had smoked tobacco or consumed alcohol in the past 6 months or more were considered to be current users, while those who had quit for more than 1 year were considered to be previous users. A history of diabetes and hypertension was based on self-reported histories or current medication use for these conditions.

Anthropometric indices and biochemical factors

Anthropometric and metabolic data were collected by routine physical examinations. BMI was calculated by dividing a person’s weight with his or her height squared (kg/m2). WC was measured at the mid-level between the costal margins and the iliac crests. Hip circumference was measured around the pelvis at the point of maximal protrusion of the buttocks. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), total cholesterol (TCHO), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), and triglycerides (TG) were measured after an 8-h overnight fast. Blood pressure was measured using an automatic device (HEM 7310; OMRON Life Science, Japan). Body weight and fat percentage were measured using bioelectrical impedance analysis (UM-501, TNITA, Japan). People who had a BMI that was greater than or equal to 23 and less than 25kg/m2 were defined to be overweight. People who had a BMI that was greater than or equal to 25kg/m2 were defined to be general obese, according to the WHO Asia-Pacific criteria [14]. General obesity 1 was defined to be BMI ≥30kg/m2 for comparison. Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was defined by using the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute criteria [15]. Central obesity was defined as WC ≥90 cm in men, and/or ≥80 cm in women [14].

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means ± standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Student’s t-test was used to test for significant differences in continuous data between two groups. ANOVA was used to test for the significant differences among three groups. The Chi-square (x2) test was used to compare the differences in categorical variables. All statistical tests were 2-sided at the 0.05 significance level. These statistical analyses were performed using the PC version of SPSS statistical software (17th version, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

A total of 149 subjects were recruited for this survey. In general, men were older, taller, and had greater fasting glucose, uric acid levels, and prevalence of type 2 diabetes, but lower prevalence of general obesity, central obesity, dyslipidemia, and MetS when compared to women (Table 1). The prevalence of overweight, general obesity, central obesity was 23.4, 42.6, and 42.6% in men and 7.8, 64.7, and 69.6% in women, respectively (Table 1 and Fig. 1a). Older people were found to have higher prevalence of overweight, obesity, and MetS (all p < 0.05). The prevalence of general obesity and central obesity among people aged 20–39, 40–64, and 65 years old and above were 34.4, 65.7 and 61.0% for general obesity and 37.5, 68.6, and 66.0% for central obesity, respectively (Fig. 1a). The prevalence of MetS was 10.6% in men and 33.3% in women, respectively (Fig. 1b). In both genders, the prevalence of hypertension, central obesity, and MetS was significantly different among these three BMI groups (Table 2a). In men, WC and HDL-C were significantly different among BMI groups (Table 2b). In women, systolic BP, diastolic BP, TCHOL, and WC were significantly different among BMI groups (Table 2b). In both genders, when compared to the non-central obesity group, subjects in the central obesity group were older and had higher weight, BMI, body fat, WC, hip circumference, systolic and diastolic BP, and prevalence of hypertension (Table 3). No significant correlation was found between BMI groups and the prevalence of diabetes and/or fasting glucose in either men or women (Table 2). As of the prevalence of diabetes and/or fasting glucose, the non-central obesity group was not significantly associated with the central obesity group in neither gender (Table 3).

Table 1.

Anthropometric indexes and metabolic factors between genders.

| Men (n = 47) | Women (n= 102) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58.8 ±18.3 | 52.7 ±15.6 | 0.037 |

| Height (cm) | 162.6 ±7.5 | 153.4 ±6.4 | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 65.8 ±10.6 | 62.3 ±12.0 | 0.093 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 4.0 | 26.4 ± 4.3 | 0.051 |

| WC (cm) | 88.7 ±11.7 | 87.1 ± 12.1 | 0.438 |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 96.3 ± 8.4 | 100.0 ±10.3 | 0.024 |

| Fat(%) | 24.2 ± 6.6 | 37.5 ±6.2 | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 136.7 ±21.7 | 130.3 ± 22.4 | 0.106 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 83.7 ±11.6 | 80.6 ±11.8 | 0.137 |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 4.85 ±1.53 | 4.41 ± 0.70 | 0.022 |

| HbA1C(%) | 6.22 ± 0.61 | 5.99 ± 0.35 | 0.022 |

| Uric acid (μmol/L) | 371.0 ±50.1 | 272.2 ±62.0 | <0.001 |

| TCHOL (mmol/L) | 4.66 ± 0.30 | 4.71 ± 0.54 | 0.528 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.13 ±0.25 | 1.10± 0.38 | 0.607 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.22 ±0.13 | 1.21 ± 0.12 | 0.649 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 166 ±20.5 | 143 ±19.2 | <0.001 |

| Overweight (%)a | 23.4 | 7.8 | 0.009 |

| General obesity (%)a | 42.6 | 64.7 | - |

| General obesity 1 (%)a | 10.6 | 23.5 | 0.065 |

| Central obesity (%)b | 42.6 | 69.6 | 0.002 |

| Hypertension (%)c | 48.9 | 40.2 | 0.317 |

| Diabetes (%)d | 25.5 | 8.8 | 0.006 |

| Dyslipidemia (%)e | 25.5 | 82.4 | <0.001 |

| MetS (%)f | 10.6 | 33.3 | 0.003 |

| Smoking (%) | |||

| Never | 59.6 | 100 | <0.001 |

| Former | 23.4 | 0 | |

| Current | 17.0 | 0 | |

| Alcohol drink (%) | |||

| Never | 51.1 | 98.0 | <0.001 |

| Former | 31.9 | 1.0 | |

| Current | 17.0 | 1.0 |

Present with mean ± standard deviation in continuous variables and percentage in categorical variables; presented in SI units.

Student’s t-test for unpaired data was used for the comparison of mean values between groups and Chi Square test for categorical data.

Abbreviation: BMI: body mass index, WC: waist circumference, HIP: hip circumference, BP: blood pressure, TCHOL: total cholesterol, TG: triglycerides, HDL-C: high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol, MetS: metabolic syndrome, HbAlc: hemoglobin Alc.

Overweight was defined as 25 > BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2; General obesity was defined as BMI ≥25 kg/m2; general obesity 1 was defined as BMI ≥30kg/m2.

Central obesity is defined as WC ≥90 cm in men or ≥80 cm in women.

Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥140mmHg, and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg,and/or hypertension history and on anti-hypertensive drug treatment.

Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥7 mmol/L and/or HbAlc ≥6.5% and/or diabetes history and on oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin treatment.

Dyspilidemia defined as subjects with high TG (triglycerides ≥1.7mmol/L) and/or high TCHOL (total cholesterol ≥5.17mmol/L) and/or low HDL-C (HDL-C <1.03mmol/L (40 mg/dL) in men or <1.29 mmol/L (50 mg/dL) in women).

MetS: metabolic syndrome defined using the American Heart Associa- tion/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute criteria.

Figure 1.

(a) Prevalence of general obesity and central obesity between genders and among age groups (age 20–39, 40–64, ≥65 years). (b) Prevalence of metabolic syndrome between genders and age groups (age 20–39, 40–64, ≥65 years).

Table 2.

The relationship between BMI groups and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors in different BMI definition in men. (a) BMI groups versus various prevalence of CVD risk factors; (b) BMI groups versus blood pressure, waist circumference, and laboratory indices.

| (a) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD risk factors (Prevalence, %) | Gender | BMI groupsj |

p Value | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Hypertensiona | M | 18.8 | 54.5 | 70.0 | 0.009 |

| F | 25.0 | 12.5 | 50.0 | 0.019 | |

| Diabetesb | M | 18.8 | 27.3 | 30.0 | 0.735 |

| F | 3.6 | 12.5 | 10.6 | 0.508 | |

| High TGc | M | 6.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.372 |

| F | 0 | 12.5 | 3.0 | 0.182 | |

| High TCHOLd | M | 12.5 | 9.1 | 10.0 | 0.954 |

| F | 3.6 | 12.5 | 18.2 | 0.169 | |

| Low HDL-Ce | M | 0 | 0 | 30.0 | 0.010 |

| F | 85.7 | 75.0 | 68.2 | 0.211 | |

| Dyslipidemiaf | M | 18.8 | 9.1 | 40.0 | 0.125 |

| F | 89.3 | 87.5 | 78.8 | 0.438 | |

| Hyperuricemiag | M | 0 | 0 | 5.0 | 0.502 |

| F | 3.6 | 0 | 10.6 | 0.353 | |

| Central obesityh | M | 0 | 27.3 | 85.0 | <0.001 |

| F | 25.0 | 62.5 | 89.4 | <0.001 | |

| MetSi | M | 0 | 0 | 25.0 | 0.023 |

| F | 17.9 | 12.5 | 42.4 | 0.030 | |

| (b) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVD risk factors | Gender | BMI groupsj |

p Value | ||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | M | 130.9±25.6 | 136.6±23.5 | 141.3±16.7 | 0.370 |

| F | 123.9±24.2 | 118.1±15.7 | 134.5±21.3 | 0.028 | |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | M | 81.7±12.7 | 80.1±13.3 | 87.2±9.0 | 0.187 |

| F | 76.8±12.4 | 75.0±7.5 | 82.9±11.4 | 0.026 | |

| FBG (mmol/L) | M | 4.52±1.30 | 4.90±1.71 | 5.10±1.64 | 0.545 |

| F | 4.29±0.47 | 4.35±0.44 | 4.47±0.79 | 0.525 | |

| TCHOL (mmol/L) | M | 4.68±0.34 | 4.55±0.32 | 4.64±0.27 | 0.914 |

| F | 4.50±0.40 | 4.66±0.25 | 4.80±0.59 | 0.042 | |

| TG (mmol/L) | M | 1.19±0.36 | 1.09±0.22 | 1.11±0.15 | 0.523 |

| F | 1.04±0.17 | 1.11±0.34 | 1.13±0.44 | 0.614 | |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | M | 1.28±0.11 | 1.25±0.06 | 1.16±0.14 | 0.011 |

| F | 1.20±0.11 | 1.18±0.12 | 1.22±0.12 | 0.680 | |

| Uric acid (εmol/L) | M | 358±43.9 | 382±45.0 | 375±57.1 | 0.429 |

| F | 264±60.7 | 264±50.8 | 277±64.0 | 0.596 | |

| WC (cm) | M | 78.2±6.2 | 87.0±5.2 | 98.1±9.78 | <0.001 |

| F | 74.8±7.4 | 82.8±8.8 | 92.8±9.7 | <0.001 | |

Present with mean ± standard deviation in continuous variables and percentage in categorical variables; presented in SI units.

Chi-Square test was used in (a) for categorical variables; ANOVA test was used in (b) for continuous variables.

Abbreviation: CVD: cardiovascular disease, BMI: body mass index, WC: waist circumference, BP: blood pressure, FPG: fasting plasma glucose, TCHOL: total cholesterol, TG: triglycerides, HDL-C: high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol, MetS: metabolic syndrome, HbA1c: hemoglobinA1c.

BMI was defined using Asia-Pacific criteria[14].

Hypertensionwas defined as systolic BP ≥140mmHg, and/ordiastolic BP ≥90mmHg, and/or hypertension history and on anti-hypertensive drug treatment.

Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥7 mmol/L and/or HbA1c ≥6.5% and/or diabetes history and on oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin treatment.

High TG defined as: triglycerides ≥1.7 mmol/L (150 mg/dL).

High TCHOL defined as: total cholesterol ≥5.17mmol/L(200mg/dL).

Low HDL-C defined as: HDL-C<1.03mmol/L(40mg/dL) in men or<1.29mmol/L(50mg/dL) in women.

Dyspilidemia defined as subjects with high TG and/or high TCHOL and/or low HDL-C.

Hyperuricemia was defined as serum uric acid ≥446.1 μmol/L (7.5 mg/dL) in men or ≥386.6 μmol/L (6.5 mg/dL) in women; others were defined as normouricemia.

Central obesitywas defined as WC ≥90cm in men or ≥80cm in women.

MetS: metabolic syndrome was defined by the American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute criteria.

BMIgroups:group1:underweightandnormoweight(BMI<23kg/m2);group2:overweight(25>BMI ≥23kg/m2);group3:obesity(BMI ≥25kg/m2),detailed description in the text; present with prevalence of CVD risk factors (%) in (a) and mean ± SD in (b).

Table 3.

The relationship between central obesity and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors in both genders.

| Central obesitya | Gender |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men(n = 47) |

Women (n= 102) |

|||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| Age (years) | 66.0 ±15.6* | 53.5 ±18.7* | 54.8 ±14.4* | 48.0 ±17.4* |

| Height (cm) | 162.3±6.3 | 162.8±8.4 | 154.0± 6.2 | 151.9± 6.8 |

| Weight (kg) | 74.1±8.9‡ | 59.6±7.0‡ | 67.0±10.5‡ | 51.6±7.8‡ |

| BMI (kg/mb) | 28.2±3.4‡ | 22.5±2.4‡ | 28.2±3.6‡ | 22.3±2.8‡ |

| WC (cm) | 99.4±8.4‡ | 80.8±6.1‡ | 93.2±8.8‡ | 73.1±4.6‡ |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 102.7±7.0‡ | 91.6±5.9‡ | 104.3±8.6‡ | 90.0±6.3‡ |

| Fat (%) | 28.3±4.7‡ | 21.2±6.3‡ | 40.1±4.8‡ | 31.6±4.6‡ |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 143.9±18.0* | 131.3±22.9* | 133.8±20.1* | 122.4±25.6* |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 87.6±9.9* | 80.7±12.1* | 82.6±10.6* | 75.8±13.1* |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 4.95±1.62 | 4.78±1.50 | 4.47±0.76 | 4.28±0.48 |

| HbA1c(%) | 6.09±0.37 | 6.31±0.74 | 6.00±0.41 | 5.96±0.15 |

| Uric acid (εmol/L) | 382±50.7 | 362±48.9 | 280±62.1* | 254±58.6* |

| TCHOL (mmol/L) | 4.63±0.27 | 4.68±0.33 | 4.76±0.51 | 4.60±0.60 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.12±0.14 | 1.15±0.31 | 1.14±0.43 | 1.02±0.17 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.19±0.13 | 1.24±0.12 | 1.21±0.12 | 1.21±0.12 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 165±19.5 | 168±21.5 | 146±18.6† | 135±18.3† |

| Hypertension (%)b | 75.0† | 29.6† | 47.9* | 22.6* |

| Diabetes (%)c | 25.9 | 25.0 | 0 | 12.7 |

| Dyslipidemia (%)d | 30.0 | 22.2 | 80.3 | 87.1 |

Present with mean ± standard deviation in continuous variables and percentage in categorical variables; presented in SI units.

Student’s t-test for unpaired data was used for the comparison of mean values between groups and Chi-Square test for categorical data.

Abbreviation: BMI: body mass index, WC: waist circumference, BP: blood pressure, FPG: fasting plasma glucose, TCHOL: total cholesterol, TG: triglycerides, HDL-C: high- density-lipoprotein cholesterol, HbAlc: hemoglobin Alc.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

p<0.001.

Central obesity is defined as WC ≥90cm in men or ≥80cm in women.

Hypertension was defined as systolic BP ≥140mmHg, and/or diastolic BP ≥90mmHg, and/or hypertension history and on anti-hypertensive drug treatment.

Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥7 mmol/L and/or HbAlc ≥6.5% and/or diabetes history and on oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin treatment.

Dyspilidemia defined as subjects with high TG (TG ≥1.7 mmol/L) and/or high TCHOL(TCHOL ≥5.17 mmol/L) and/orlow HDL-C (HDL-C <1.03 mmol/L(40mg/dL) in men or <1.29 mmol/L (50 mg/dL) in women)

Discussion

In this study, Tibetan immigrant women have higher prevalence of general and central obesity, dyslipidemia, and MetS than men. About two third Tibetans living in Ladakh, India are classified as general and central obesity. While most studies revealed that the prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes has positive associations, in this study, the prevalence of obesity is high among these Tibetan immigrants, but the prevalence of type 2 diabetes is low. The association between diabetes and fasting glucose is not related to any BMI groups nor any central obesity groups in both genders.

Norboo et al. assessed the prevalence of obesity (defined as BMI ≥25kg/m2) in Ladakh area to be 27.7% in men and 21.8% in women, respectively [16]. Sherpa et al. reported that the prevalence of central obesity and MetS in Tibet at 3700 m high was 46% and 8.2%, respectively [17]. Another study that compared Tibet people living in different altitude levels revealed that the prevalence of general obesity (defined as BMI ≥30kg/m2) and central obesity (defined as WC >88 cm for women and WC >102 cm for men) decreases as the altitude increases. The prevalence of obesity among adult Tibetans living at an altitude of 1200, 2900, and 3660 m were 19.7, 11.8, 9.7% for general obesity and 53.5, 57.1, and 24.8% for central obesity [8]. Zhao et al. found that the prevalence of overweight and obesity (defined as BMI ≥25 and 30kg/m2) among Tibet minorities in China ranged from 6.3% to 18.4% [18]. A study done in U.S. by Voss et al., found that, after adjusting for confounds, people living in low altitudes (below 500 m sea level) have lower risks of obesity, compared with those living in high altitudes (above 3000 m sea level) [5]. Compared to these studies, Tibetan immigrants living in Ladakh (about 3500 m above sea level) have higher prevalence of general obesity, central obesity and MetS than original Tibetans living in China, especially among women. More than two thirds of the women are classified as general obesity and/or central obesity. More than one third of women are also classified to have MetS. The gender difference for the prevalence of obesity among Tibetans was similar to global gender disparities in obesity [19,20]. Garawi et al. and Kanter and Caballero both reported that in most populations the prevalence of obesity is greater in women than in men, especially in developing countries [19,20]. Many reasons may explain this phenomenon, including increased calorie and decreased basal metabolic rates. Sherpa et al. reported that calorie consumption increased significantly—by 1446 kcal per altitude among Tibetans living in high altitudes [8]. Tschop et al. and Lippl et al. both reported that subjects who moved to high altitude areas for a short time induced significantly lower food intake and loss of appetite [21,22]. However, after remaining stationary in the high altitude among the natives, the population’s calorie consumption increased [8,23]. Cold weather leads to peripheral vessel constriction and less exercise. High altitude leads to chronic hypoxia. Both the weather and the altitude may have lead subjects to a decreased amount of exercise, which then leads to a lower basal metabolic rate. Calorie intake increases and energy expenditure decreases, leading to positive energy gain, which induces high prevalence of obesity.

One of the biggest differences between our study and other studies is that we found that general obesity and/or central obesity are not related to the prevalence of diabetes. Obesity is known for being one of the important risk factors for many chronic diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease in people living in the low altitude areas. Okumiya et al. found that overweight is only associated with impaired glucose intolerance but not diabetes among Tibetan living in high attitude highlands [24]. Chronic hypoxia induced polycythemia among people living in high altitude has been studied by many researchers. Chronic hypoxia was found to be related to a decrease in blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and increase insulin sensitivity [25–27]. One of the major roles of cellular response to hypoxia is hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF-1 and HIF-2) [25,28,29]. The increased expression of HIF-1 and HIF-2 may enhance cellular glucose uptake, glycolysis, and glycogenesis, but decrease hepatic gluconeogenesis [24,28,29]. Gamboa et al. found that the adaptation of mouse skeletal muscle respond to chronic hypoxia is increased by insulin-stimulated glucose uptake. In a human epidemiologic study, Woolcott et al. found an inverse association between diabetes and altitude in the United States [30]. Based on these potential mechanisms, previous studies have showed that, compared with those living in low altitudes, people living in high altitudes have lower glycemia independent of BMI and obesity [23,31,32]. In this study, a gender difference was found between diabetes and obesity. Men have a higher prevalence of diabetes, but lower prevalence of general obesity and central obesity than women. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the prevalence of diabetes and/or serum glucose levels seems to increase by the increase of BMI groups, but it was not statistically significant. More research is required to clarify the reason for the gender difference in this population between diabetes and obesity.

There are limitations in this study. First, the sample size is not robust. The distribution of the age is older and there are more women in our participants than original immigrants living in the settlement. However, the primary health care centre, TPHCC, would recruit the more participants to join the service screening in future based on the census data. Second, since this is a cross-sectional study, causality is not possible. Further longitudinal study is necessary to find out the causality between obesity and diabetes among these Tibetan immigrants. Third, the lower reported blood glucose in high altitude area may result due to the wrong measurements that occurred because of the cold weather, increased red blood cell count mass, and hypoxia. However, blood plasma was used to measure blood glucose. Measuring blood glucose by use of blood plasma has already been confirmed to be less erroneous. Many previous studies have also found a lower plasma glucose level among people living in high altitudes [23,26,32]. Fourth, the use of lipid lower agents was not included in the questionnaire, which may have cause an underestimation for the prevalence of dyslipidemia and MetS. Finally, although these Tibetan immigrants live in similar high altitude areas as the original Tibetans, they cannot represent all original Tibetans. However, the European anthropologist, Christoph von Furer-heimendorf, has reported that the Tibetan refugees’ preservation of their cultural identity and religious institutions has been successful. The term “ renaissance of Tibetan civilization” was used to emphasise and conclude that these refugees have developed viable monastic communities similar to those in Tibet [33]. Therefore, since the custom and religious belief of these immigrants are quite similar to the original population, this study still has their value to represent the Tibetan immigrants who deserve more attention in the health aspect, especially in obesity. Future genetic tests are needed to confirm whether there is a difference in the population.

Conclusion

Among the Tibetan immigrants living in high altitude area in Leh Ladakh, India, the prevalence of general and central obesity was found to be quite high, especially among women. Furthermore, obesity is related to MetS and hypertension, but not diabetes in this population. The different altitudes do not affect the prevalence of MetS among women. Future larger scale studies are needed to confirm the findings in this study.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Miss Yi-Luen Wu, Miss Hao-Yu Yang, Miss Tyan-Shin Yang, Miss Yu-Tian Hsieh, Miss Hung-Yu Lin, Miss Yi-Ting Tsai, Miss Mei-Lan Hung, Miss. Hui-Hsuan Chen, Miss Cheng-Yi Yen, Mr. I-Ting Lin, Mr. Chih-Ting Chang, Mr. Zi-Jiang Lim, Mr. Ting-Chi Yang, Mr. Tzu-Yu Lin, Mr. Yi-Jhang Liu, Mr. Chih-Yin Lin, Mr. Yao-An Wu, Mr. Chen-Yang Wang, Mr. Jeng-Che Yen and Mr. Jia-Hao Lee for helping with the data collection and the field work. We also thank all staffs of Tibetan Primary Health Care Center (TPHCC) for the recruitment of the participants.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- [1].World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight; 2016. Assessed at www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/.

- [2].Collaboration NCDRF. Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19.2 million participants. Lancet 2016;387:1377–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Global BMIMC. Body-mass index and all-cause mortality: individual-participant-data meta-analysis of 239 prospective studies in four continents. Lancet 2016;388:776–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dobbins M, Decorby K, Choi BC. The association between obesity and cancer risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies from 1985 to 2011. ISRN Prev Med 2013;2013:680536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Voss JD, Masuoka P, Webber BJ, Scher AI, Atkinson RL. Association of elevation, urbanization and ambient temperature with obesity prevalence in the United States. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37:1407–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Voss JD, Allison DB, Webber BJ, Otto JL, Clark LL. Lower obesity rate during residence at high altitude among a military population with frequent migration: a quasi experimental model for investigating spatial causation. PLoS One 2014;9:e93493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Diaz-Gutierrez J, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Pons Izquierdo JJ, Gonzalez-Muniesa P, Martinez JA, Bes-Rastrollo M. Living at higher altitude and incidence of overweight/obesity: prospective analysis of the SUN cohort. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sherpa LY, Deji Stigum H, Chongsuvivatwong V, Thelle DS, Bjertness E. Obesity in Tibetans aged 30–70 living at different altitudes under the north and south faces of Mt. Everest. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010;7:1670–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Averett S, Argys L, Kohn J. Chapter 13: Immigrants, wages and obesity: the weight of the evidence In: International handbook on the economics of migration. Cheltenham: UK: Edward Elgar Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Averett SL, Argys LM, Kohn JL. Immigration, obesity and labor market outcomes in the UK. IZA J Migr 2012;1:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Park J, Myers D, Kao D, Min S. Immigrant obesity and unhealthy assimilation: alternative estimates of convergence or divergence, 1995–2005. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:1625–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Bates LM, Acevedo-Garcia D, Alegria M, Krieger N. Immigration and generational trends in body mass index and obesity in the United States: results of the National Latino and Asian American Survey, 2002–2003. Am J Public Health 2008;98:70–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bhatia S, Dranyi T, Rowley D. A social and demographic study of Tibetan refugees in India. Soc Sci Med 2002;54:411–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].World Health Organization Western Pacific Region, International Association for the Study of Obesity, International Obesity Task Force. The Asia-Pacific perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment; 2000. Assessed at http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/obesity/0957708211/en/.

- [15].Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 2005;112:2735–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Norboo T, Stobdan T, Tsering N, Angchuk N, Tsering P, Ahmed I, et al. Prevalence of hypertension at high altitude: cross-sectional survey in Ladakh, Northern India 2007–2011. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sherpa LY, Deji Stigum H, Chongsuvivatwong V, Nafstad P, Bjertness E. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and common metabolic components in high altitude farmers and herdsmen at 3700 m in Tibet. High Alt Med Biol 2013;14:37–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Zhao D, Li Y, Zheng L. Ethnic inequalities and sex differences in body mass index among Tibet minorities in China: implication for overweight and obesity risks. Am J Hum Biol 2014;26:856–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kanter R, Caballero B. Global gender disparities in obesity: a review. Adv Nutr 2012;3:491–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Garawi F, Devries K, Thorogood N, Uauy R. Global differences between women and men in the prevalence of obesity: is there an association with gender inequality? Eur J Clin Nutr 2014;68:1101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lippl FJ, Neubauer S, Schipfer S, Lichter N, Tufman A, Otto B, et al. Hypobaric hypoxia causes body weight reduction in obese subjects. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:675–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Tschop M, Strasburger CJ, Hartmann G, Biollaz J, Bartsch P. Raised leptin concentrations at high altitude associated with loss of appetite. Lancet 1998;352:1119–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Woolcott OO, Ader M, Bergman RN. Glucose homeostasis during short-term and prolonged exposure to high altitudes. Endocr Rev 2015;36:149–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Okumiya K, Sakamoto R, Ishimoto Y, Kimura Y, Fukutomi E, Ishikawa M, et al. Glucose intolerance associated with hypoxia in people living at high altitudes in the Tibetan highland. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].McClain DA, Abuelgasim KA, Nouraie M, Salomon-Andonie J, Niu X, Miasnikova G, et al. Decreased serum glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin levels in patients with Chuvash polycythemia: a role for HIF in glucose metabolism. J Mol Med (Berl) 2013;91:59–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lindgarde F, Ercilla MB, Correa LR, Ahren B. Body adiposity, insulin, and leptin in subgroups of Peruvian Amerindians. High Alt Med Biol 2004;5:27–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gamboa JL, Garcia-Cazarin ML, Andrade FH. Chronic hypoxia increases insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in mouse soleus muscle. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2011;300:R85–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Pescador N, Villar D, Cifuentes D, Garcia-Rocha M, Ortiz-Barahona A, Vazquez S, et al. Hypoxia promotes glycogen accumulation through hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-mediated induction of glycogen synthase 1. PLoS One 2010;5:e9644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Rankin EB, Rha J, Selak MA, Unger TL, Keith B, Liu Q, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism. Mol Cell Biol 2009;29:4527–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Woolcott OO, Castillo OA, Gutierrez C, Elashoff RM, Stefanovski D, Bergman RN. Inverse association between diabetes and altitude: a cross-sectional study in the adult population of the United States. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2014;22:2080–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Castillo O, Woolcott OO, Gonzales E, Tello V, Tello L, Villarreal C, et al. Residents at high altitude show a lower glucose profile than sea-level residents throughout 12-hour blood continuous monitoring. High Alt Med Biol 2007;8:307–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zamudio S, Torricos T, Fik E, Oyala M, Echalar L, Pullockaran J, et al. Hypoglycemia and the origin of hypoxia-induced reduction in human fetal growth. PLoS One 2010;5:e8551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Furer-Haimendarf Cv. The renaissance of Tibetan civilization. New Mexico, USA: Synergetic Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]