Abstract

Bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) affects the presence of macrophage subtypes in vitro and in vivo at an early stage of atherosclerosis (ATH); however, it remains unknown whether BMP-7 treatment affects the development and progression of ATH at a mid-stage of the disease. We therefore performed a Day 28 (D28) study to examine BMP-7’s potential to affect monocyte differentiation. Atherosclerosis was developed in ApoE KO mice, and these animals were treated with intravenous (IV) injections of BMP-7 and/or liposomal clondronate (LC). BMP-7 significantly (p<0.05) lowers plaque formation following induction of atherosclerosis. However, upon macrophage depletion, BMP-7 fails to significantly alter plaque progression suggesting a direct role of BMP-7 on macrophages. Immunohistochemical staining of carotid arteries was performed to determine BMP-7’s effect on pro-inflammatory M1 (iNOS) and anti-inflammatory M2 (CD206, Arginase-1) macrophages, and monocytes (CD14). BMP-7 significantly reduced pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and increased anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages at D28, while BMP-7 showed no effect on M2 macrophage differentiation in animals treated with LC. ELISA data showed significant reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, MCP-1, and TNF-α) and a significant increase in anti-inflammatory cytokine (IL-10) in BMP-7 treated mice (p<0.05).Western blot analysis of arterial tissue confirms a significant increase in pro-survival kinases ERK and SMAD and a reduction in pro-inflammatory kinases p38 and JNK in BMP-7 treated mice (p<0.05). Overall, this study suggests that clondronate treatment inhibits BMP-7 induced differentiation of monocytes into M2 macrophages and improved systolic blood velocity.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis (ATH) is an inflammatory disease characterized by lipid, immune cell, and extracellular matrix accumulation within the arterial wall, causing thickening of the affected arterial area. Despite pharmacological interventions, ATH still leads to development of more serious complications, such as heart disease and stroke; two leading causes of death worldwide(1).

ATH is initiated when endothelial cells lining the interior of the artery become irritated as a result of pro-inflammatory conditions such as dyslipidemia, smoking, hypertension, or disturbances to blood flow (2–4). The inflamed endothelium expresses adhesion molecules capable of capturing circulating immune cells, such as monocytes, T cells, and dendritic cells at the area of injury, leading to their subsequent infiltration into the arterial wall(5). Of research interest, monocytes within the arterial wall are then signaled via cytokines and other molecules, such as LDL, to differentiate into macrophages of varying phenotypes, specifically pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages or anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages (5).

Inflammatory M1 macrophages exhibit a pro-atherogenic profile, characterized by the release of inflammatory cytokines and activation of pro-inflammatory pathways JNK and p38 (6). Increased M1 macrophage presence is found in cases of severe ATH and these cells are thought to contribute significantly to the advancement of the disease (6). Additionally, M1 activation of the JNK or p38 pathway in the context of ATH further leads to production of more inflammatory cytokines, fueling the ongoing immune response (6).

Alternatively, monocytes can also differentiate into anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages. M2 macrophages promote clearing of debris and apoptotic cells within the plaque, releasing anti-inflammatory molecules such as IL-10 and IL-4, and aiding in overall suppression of the ongoing immune response (6). The corresponding balance of the two macrophage phenotypes contributes significantly to plaque progression and disease development (2, 7, 8). As such, research interest has developed to identify novel, small molecules with the capacity to direct monocyte differentiation to M2 macrophages. Moreover, identification of molecular mechanisms responsible for directing monocyte differentiation to M2 macrophages in vivo remain unclear.

There are a few distinct subsets of M2 macrophages, most notable are M2a and M2c (6). M2a macrophages have been found to have wound healing and pro-fibrotic properties, and are induced by IL-4 and IL-13 (6, 9, 10). M2c are considered to play a more regulatory role in the disease progression, and these are polarized by IL-10, TGF- β, and glucocorticoids (6, 10). However, the exact molecular mechanisms of these subsets and their specific roles within the differing models of ATH have yet to be fully elucidated. The current study focuses on M2 macrophage as a whole, rather than specific subsets.

Previously, we have shown that treatment with bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7), a growth factor and member of the TGF-β superfamily, increases the ratio of M2:M1 macrophages in vivo at an early stage of ATH (Day 14) (9–11). Specifically, BMP-7 treatment directs monocyte polarization towards the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype and decreases ATH development at an earlier stage. However, it remains unknown as to whether BMP-7 attenuates ATH later in the disease progression, and what the molecular mechanisms are that decrease disease progression once developed. This study was designed to examine the effects of BMP-7 on mid-stage disease development of ATH at a day 28 (D28) time point in ApoE knockout mice which were at least 10 weeks of age, thereby expanding upon the results our previous D14 study that examined early stage ATH(12). Moreover, we also provide evidence of the involvement of molecular mechanisms mediated through the P38 and JNK pathways leading to increased differentiation of M2 macrophages. Furthermore, we performed additional confirmation by depleting monocytes or M1 macrophages at least partially with liposomal clondronate (LC) to understand whether BMP-7 induces monocyte or M1 macrophage differentiation into M2 macrophages that play a role in improvement of ATH.

Materials and Methods

Partial Ligated Carotid Artery (PLCA) surgery

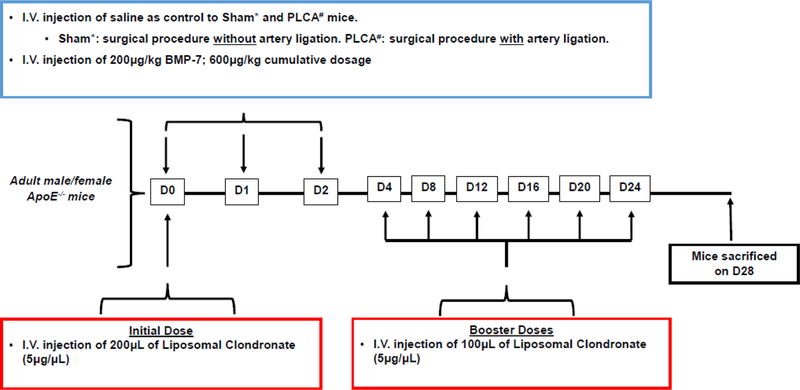

All animal protocols were approved by the University of Central Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and surgery was performed as previously reported (13). Briefly, 10–12 week old male and female ApoE KO mice were sedated under 3–4% inhalatory isoflurane and arranged in the supine position. Animals were then divided into five groups: 1) Sham, 2) PLCA, 3) PLCA + BMP-7, 4) PLCA+ LC, and 5) PLCA + BMP-7 + LC and administered pain medication via intramuscular injection to the left thigh. Using medical grade scissors and tweezers, the left carotid artery (LCA) was exposed as previously reported (13). A 7/0 polypropylene or silk suture (CP Medical, #8703P or Ethicon, #768) was then placed around 3 of the 4 branches of the carotid artery; the left external and internal carotid, and the occipital artery. The superior thyroid artery was left undisturbed. After ligation of the artery, the surgical area was closed using a 4/0 silk or polypro suture (Ethicon, #736G or CP Medical, #8629) and mice were allowed to recover under oxygen administration via nose cone on a heated pad. Sham animals underwent all of the aforementioned procedure, however, instead of ligating the artery, the suture was simply looped around it but not tied. Following surgery, treatment groups receiving BMP-7 were administered a dose of 200µg/kg of body weight via tail vein injection (Fig 1) (Bioclone, PA-0401). The BMP-7 injection was repeated two more times, at D1 and D2 post-surgery for a total of three injections. Groups receiving LC were administered an initial i.v. dose of 200 µl LC immediately following surgery, and subsequent i.v. doses of 100 µl LC every four days (Fig 1), in order to maintain depletion of monocyte and macrophage immune populations for the duration of the D28 time point (Liposoma, LIP-01)(14). Noticeably, LC is reported to have a mortality rate of approximately 33.3% when injected intravenously (15). In the current study, we faced similar challenges with mortality in mice receiving LC. At the beginning of the study, there was n = 6 mice in both groups receiving LC; however, n = 4 per group survived. Moreover, at D28 post-surgery, systolic blood velocity was examined using carotid artery ultrasound. Upon completion of the ultrasound, animals were sacrificed, blood was collected, and arterial tissue harvested for further analysis. The removed arterial tissue was then divided and placed in either 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for immunohistochemical analysis or RNAlater for Western blot analysis (13).

Fig. 1:

Injection Schedule of BMP-7 and LC. Sham or PLCA surgery was performed on D0 of the D28 study on adult male and female ApoE −/− mice. Groups receiving BMP-7 were administered 200μg/kg, i.v immediately following Sham or PLCA procedure and on D1 and D2. Mice receiving LC received 200μL of LC (5μg/μL) as an initial dose via i.v. on D0 and every four days thereafter for the duration of the time point an additional booster dose of 100μL of LC (5μg/μL) was administered. On D28, functional analysis was performed and mice sacrificed prior to tissue collection.

Preparation of Paraffin Sections and Histopathology

Once arterial sections incubated for at least 24 hours in 4% PFA, they were washed in 1X PBS and processed overnight using a tissue processor machine (Leica, #15053). The arterial tissue was embedded in a paraffin block with the artery placed vertically upright. The blocks were then sectioned into 5µm slices and mounted on a charged glass slide (Fisher Scientific, USA). Following heat fixation, slides were deparaffinized using xylene and hydrated using a series of decreasing alcohol dilutions as previously described (16). This process was performed on arterial sections at various tissue depths from each animal in preparation for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The LCA was imaged on the 20X objective using an Olympic IX-70 microscope. Plaque accumulation within the artery was quantified using Image J software as previously described (13).

Immunohistochemistry

Arterial sections were deparaffinized and hydrated as described above. Slides were blocked for 1 hour using 10% goat (Vector, S-1000) or donkey serum (Sigma Aldrich, D9663). After blocking, slides were incubated overnight at 4oC with a 1:50 dilution of primary antibody in 10% goat or donkey serum. Primary antibodies used were against CD14 (monocytes, Abbiotec 251561), iNOS (M1 macrophages, Abcam, ab15323), CD206 (M2 macrophages, Abcam, ab64693), or Arginase-1 (M2 macrophages, Santa Cruz, sc18351). After overnight incubation, slides were washed and incubated with 1:50 concentration of the appropriate secondary antibody, either Alexa Fluor 488 (Alexa Fluor, A11055 and A11008) for green or 568 (Alexa Fluor, A11011) for red fluorescence, in 1X PBS for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were washed and mounted using DAPI (4’, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) (Vector Labs). Images of the LCA were taken using the 20X objective on the Olympic IX-70 microscope under fluorescent settings. The %-positive cells for CD14, iNOS, CD206, or Arginase-1 was determined as previously described using Image J software (total positive cells/total nuclei *100) (10). Representative images of each stain were taken using a Leica confocal microscope on the 40X objective.

Pro- and Anti-Inflammatory Cytokine Analysis of Blood Serum

Blood serum used for ELISA was collected in an EDTA containing tube immediately post-sacrifice and centrifuged at 12,000 G for 10 minutes. After centrifugation, the supernatant was obtained and stored at 4oC or −20oC until analysis. Serum ELISAs were performed as previously reported (10). Pro-inflammatory serum cytokine levels of IL-6 (RayBiotech, ELM-IL6), MCP-1 (RayBiotech, ELM-MCP-1–001), and TNF-α (RayBiotech, ELM-TNF-α−001) and anti-inflammatory serum cytokine levels of IL-10 (RayBiotech, ELM-IL10–001) and IL-1RA (ELM-IL1RA-001) were evaluated. Serum samples were added to an antibody coated 96-well plate in duplicate and a colorimetric assay performed. Following stoppage of the colorimetric reaction, the samples were read at 450nm on a microplate reader (BioRad) and graphed in arbitrary units (A.U.).

Western Blot Analysis of Arterial Tissue

Expression of activated pro-inflammatory (p38 and JNK) and anti-inflammatory proteins (ERK, SMAD) was determined using our standard Western blot technique (17). In brief, arterial tissue was collected, preserved in RNAlater, and stored at −80oC until homogenization. Post homogenization, proteins were estimated using Bradford Assay. Proteins were then analyzed using 10% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad) using a Bio-Rad Semi-Dry Transfer Cell at 15V for 45 minutes. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature with 5% milk, decanted, and incubated overnight with the appropriate primary antibody in 5% milk: p- JNK (Cell Signaling, 1:1000, #4668S), Total JNK (Cell Signaling, 1:1000, #9252S), p- p38 (Cell Signaling, 1:1000, #4631S), Total p38 (Cell Signaling, 1:1000, #9212S), p- ERK (Santa Cruz, 1:1000, sc7383), β-actin (1:1000, Cell Signaling, #4967L) or p-SMAD (Cell Signaling, 1:1000, #13820S). After overnight incubation, membranes were washed and incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling, 1:1000, #7074S) or anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz, 1:1000, sc2064) for one hour at room temperature. Membranes were washed and incubated with ECL (Thermo Scientific, #32106). Densitometry analysis of protein expression was completed using Image J as previously reported (9).

Levels of BMP-7 in Atherosclerosis

Serum BMP-7 levels (TSZ Scientific, M7485) were examined via ELISA to determine the effect of the diseased state on normal BMP-7 expression. The kit was followed per the manufacturer’s protocol on serum samples collected immediately post-sacrifice. Analysis of samples was performed on a microplate reader (BioRad) at 450nm and data plotted as A.U.

Systolic Blood Velocity

Systolic velocity through the carotid artery was acquired using a Phillips Sonos 5500 Ultrasound system at D28 post-surgery. Animals were first sedated at 3% isoflurane/2.5% oxygen and then 2% isoflurane/2.5% oxygen via nose cone and placed in the supine position on a heated pad. Two dimensional (2D) images were then taken (3 per animal) in B mode of blood flow through the LCA. Utilizing the vascular settings, the peak systolic velocity (SV; cm/s) was measured. The average systolic blood velocity was determined utilizing an automated caliper tool within the Sonos 5500 Ultrasound software. Three frames of systolic blood velocity were collected and analyzed for each animal within each treatment group. The frames were subjected to five measurements each using the caliper tool, which allowed for a determination of an average SV for each animal. The average SV for each treatment group was determined by combining the individual animal averages into a final representative average.

Statistical Analysis of Results

All data was analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Tukey Test. Significance was assigned only if p<0.05, data is presented as ± SEM.

Results

BMP-7 Attenuates Plaque Progression

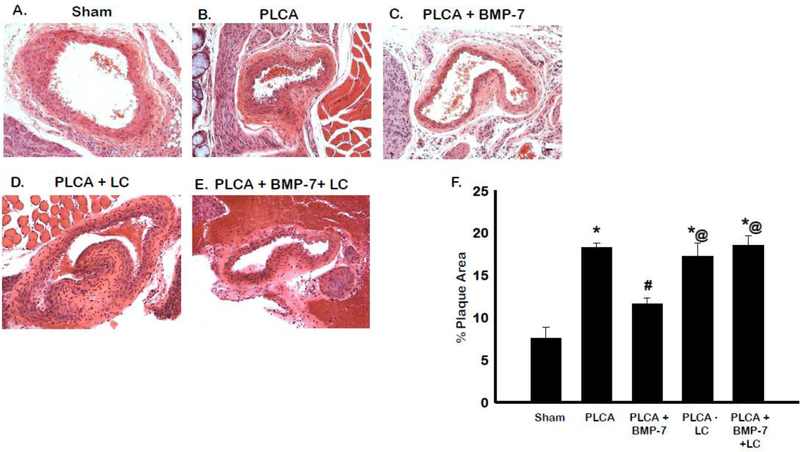

H&E staining was performed on carotid artery sections to determine the extent of plaque formation in animals post-PLCA surgery (Fig 2 A-E). Quantitative analysis of the arterial plaque-area resulted in a significant increase in total plaque development in the PLCA group compared to sham (p<0.05) (Fig 2F). Upon treatment with BMP-7, the plaque area is significantly reduced compared to PLCA (p<0.05). LC administration was unable to provide any reduction compared to the PLCA group; however, in the PLCA + BMP-7 + LC group, the protective effects of BMP-7 on plaque formation are reversed, suggesting that this protective process is mediated through differentiated M2 macrophages (p<0.05).

Fig. 2:

BMP-7 reduces plaque accumulation in the carotid artery. Representative arterial sections for sham, PLCA, PLCA+BMP-7, PLCA+LC, and PLCA + BMP-7 +LC groups stained using hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining are shown in images A-E. Scale bar = 100μm. Bar graph (F) shows quantitative analysis of percent plaque area for each treatment group. * p<0.05 vs. sham, #p<0.05 vs. PLCA, @p<0.05 vs. PLCA+BMP-7. n = 4–6 animals per group.

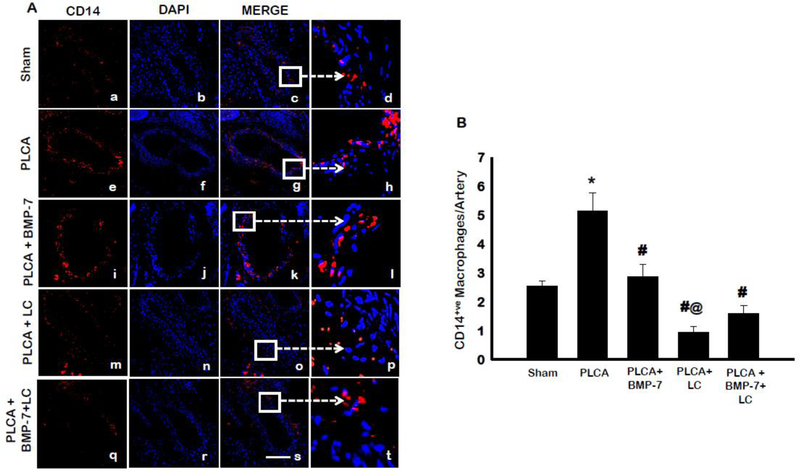

Monocyte Infiltration into the Carotid Artery

Initial injury to the arterial endothelium following PLCA surgery results in the recruitment of immune cells to the area of injury, which then infiltrate the artery (12). Monocytes were one among the most major cell types that infiltrated into the artery and were identified using the antibody against their characteristic marker, CD14. Representative images of CD14-stained monocytes within the LCA are shown in Fig 3A in red (a, e, i, m, q), DAPI stained nuclei in blue (b, f, j, n, r), and merged images (c, g, k, o, s). An enlarged section of merged images is shown in micrographs d, h, l, p, and t. Quantitative analysis of CD14+ve monocytes, shown in Figure 3B, were significantly increased in the PLCA group compared to sham animals (p<0.05). Upon administration of BMP-7, the number of CD14+ve monocytes was significantly reduced compared to PLCA (p<0.05). Treatment of LC diminished the arterial monocyte population significantly relative to PLCA and PLCA + BMP-7 (p<0.05). Notably, the PLCA + BMP-7 + LC demonstrated a decrease in monocytes compared to PLCA + BMP-7; however, data was not statistically significant. Interestingly, this data suggests that LC decreased or diminished monocytes in these groups. Therefore, BMP-7 was unable to differentiate monocytes into M2 macrophages in the left carotid artery, suggesting protective effects of BMP-7 cannot be maintained.

Fig. 3:

Monocyte infiltration in the carotid artery. Panel A shows representative photomicrographs for CD14+ve monocytes in control and treatment groups. Images show staining with anti-CD14 in red (a,e,i, m, q), nuclei marker DAPI in blue (b,f,j, n, r), merged micrographs (c,g,k, o, s), and enhanced versions of merged images (d,h,l, p, t). Scale bar = 100μm. Bar graph (B) represents the percentage of CD14+ve monocytes per artery. * p<0.05 vs. sham, #p<0.05 vs. PLCA, @p<0.05 vs. PLCA+BMP-7. n = 4–6 animals per group.

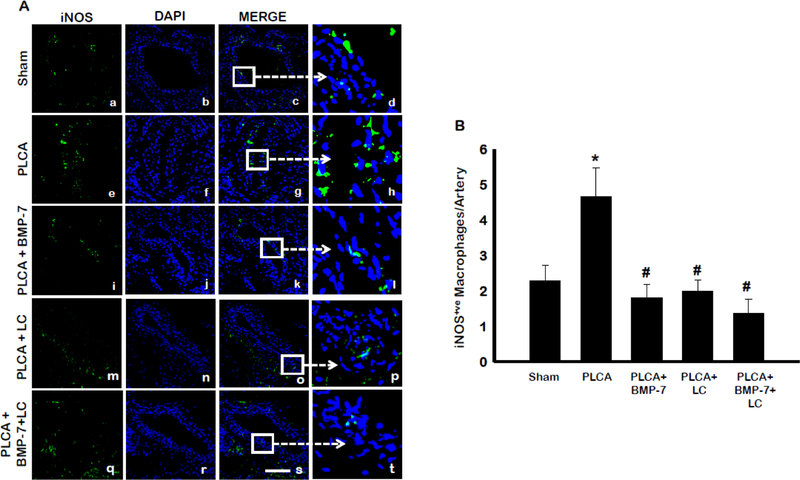

Effect of BMP-7 on M1 Macrophages in Atherosclerosis

Monocytes present within the sub-endothelial space of the artery differentiate towards an inflammatory M1 or anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage phenotype contingent on cues received from the cellular microenvironment (18). In order to evaluate BMP-7’s potential to direct monocyte differentiation, LCA sections were stained with an antibody against iNOS, a protein expressed on the surface of M1 macrophages (8).

Representative photos of iNOS-stained sections (Fig 4A) are shown in green (a, e, i, m, q), DAPI stained nuclei in blue (b, f, j, n, r), merged images (c, g, k, o, s) and enlarged sections of merged images (d, h, l, p, t). Quantitative analysis showed a statistically significant increase in iNOS+ve M1 macrophages at D28 post-surgery compared to sham (Fig 4B) (p<0.05). Noticeably, BMP-7 treatment significantly reduced the number of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages in the injured area vs. PLCA (p<0.05). LC administration resulted in a significant decrease in the presence of iNOS+ve M1 macrophages compared to PLCA, suggesting that LC depleted the M1 macrophages in the artery (p<0.05). A further decrease in pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages was seen in the PLCA + BMP-7 + LC group, compared to the PLCA + BMP-7 group. This suggests that the protective effects of BMP-7, via polarization of M1 into M2 macrophages, are not observed with administration of LC.

Fig. 4:

BMP-7 directs monocytes away from M1 phenotype. Panel A shows representative photomicrographs for iNOS+ve M1 pro-inflammatory macrophages in control and treatment groups. Images show staining with anti-iNOS in green (a,e,i,m,q), nuclei marker DAPI in blue (b,f,j, n, r), merged micrographs (c,g,k, o, s), and enhanced versions of merged images (d,h,l, p, t). Scale bar = 100μm. Bar graph (B) shows the percentage of iNOS+ve M1 macrophages per artery. * p<0.05 vs. sham, # p<0.05 vs. PLCA. n = 4–7 animals per group.

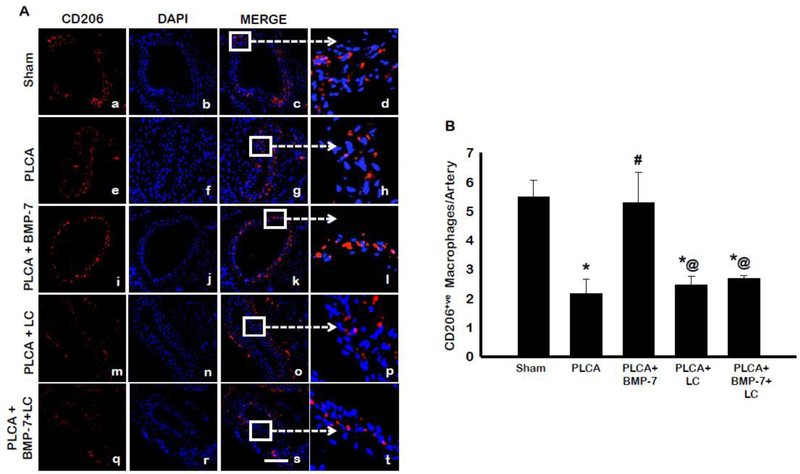

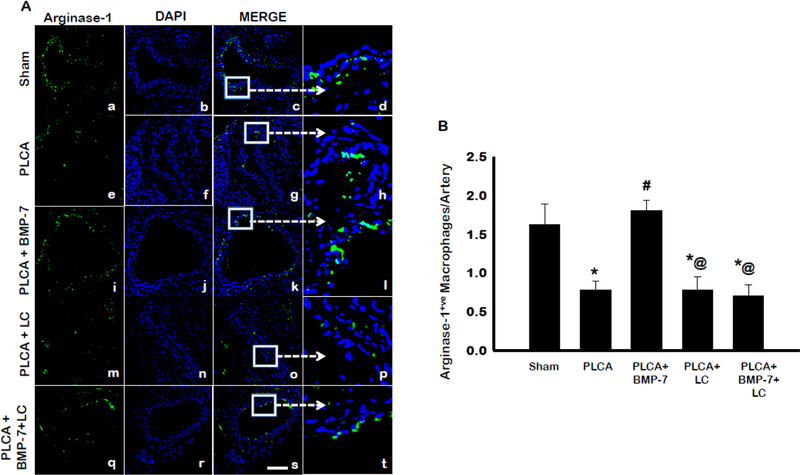

Effect of BMP-7 on M2 Macrophages in Atherosclerosis

The ability of BMP-7 to direct monocyte differentiation or M1 macrophage polarization towards the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype was also evaluated, using an antibody against the characteristic M2 marker, CD206. Representative photos are shown in Fig 5A with CD206 stained in red (a, e, I, m, q), DAPI stained nuclei in blue (b, f, j, n, r), merged images of CD206 and DAPI (c, g, k, o, s), and enlarged areas of merged images shown (d, h, l, p, t). Quantitative analysis of merged images determined the PLCA group had significantly less anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages present in the artery compared to sham (Fig 5B). Interestingly, BMP-7 treatment following PLCA surgery significantly increased the presence of CD206+ve anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages within the arterial area (p<0.05). Administration of LC diminished the presence of CD206+ve M2 macrophages, relative to sham and PLCA + BMP-7 (p<0.05). Moreover, in the PLCA + BMP-7 + LC group, there was also a significant decrease in M2 macrophages compared to both sham and PLCA + BMP-7 (p<0.05). This suggests that differentiated M2 macrophages are also depleted in the artery, as they were unable to polarize or differentiate from M1 macrophages or monocytes, due to depletion with LC. To corroborate the results of the CD206 stain, LCA sections were also analyzed for an additional M2 macrophage marker, arginase-1 (8, 18). The results shown in Fig 6A present arginase-1 stained in green (a, e, i, m, q), DAPI stained nuclei in blue (b, f, j, n, r), merged images of DAPI and arginase-1 (c, g, k, o, s), and selected enlarged areas of merged images (d, h, l, p, t). Quantitative analysis of arginase-1+ve cells in Figure 6B determined PLCA animals had significantly less M2 macrophages present within the arterial area compared with sham animals. Treatment with BMP-7 following PLCA surgery significantly increased arginase-1+ve anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages within the arterial area, (p<0.05). In the PLCA + LC group, there was a significantly diminished presence of arginase-1+ve cells compared to sham and PLCA+BMP-7 groups (p<0.05). Moreover, there was also a depletion of M2 macrophages seen in the PLCA + BMP-7 + LC group (p<0.05). Data from this arginase-1 staining is in agreement with CD206+ve M2 macrophage staining.

Fig. 5:

BMP-7 directs monocyte differentiation to CD206+ve M2 phenotype. Panels A shows representative photomicrographs for CD206+ve anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages in control and treatment groups. Images show cells stained with anti- CD206 in red (a,e,i,m,q), nuclei marker DAPI in blue (b,f,j, n, r), merged micrographs (c,g,k, o, s), and enhanced versions of merged images (d,h,l, p, and t). Scale bar = 100μm. Bar graph (B) represents the percentage of CD206+ve M2 macrophages per artery. * p<0.05 vs. sham, # p<0.05 vs. PLCA, @p<0.05 vs. PLCA+BMP-7. n = 4 animals per group.

Fig. 6:

BMP-7 directs monocyte differentiation to Arginase-1+ve M2 phenotype. Panel A shows representative photomicrographs for arginase-1+ve anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages in control and treatment groups. Images show cells stained with anti- arginase-1+ve in green (a,e,i,m,q), nuclei marker DAPI in blue (b,f,j, n, r), merged micrographs (c,g,k, o, s), and enhanced versions of merged images (d,h,l, p, t). Scale bar = 100μm. Bar graph (B) represent the percentage of Arginase-1+ve M2 macrophages per artery. * p<0.05 vs. sham, # p<0.05 vs. PLCA, @p<0.05 vs. PLCA+BMP-7. n = 4–5 animals per group.

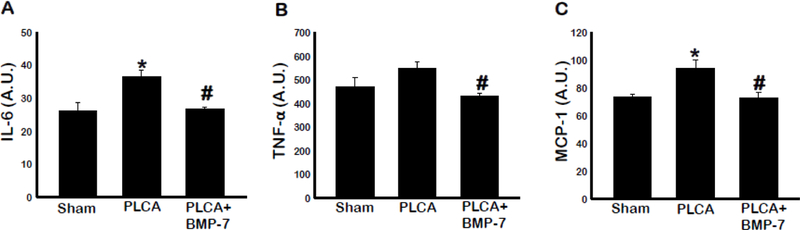

BMP-7 Reduces Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines

M1 macrophages have a characteristic cytokine profile indicative of their inflammatory nature (6, 8, 18). As such, we evaluated expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 in blood samples in Figure 7A-C, respectively. Our ELISA data shows increased levels of IL-6 (p<0.05), TNF-α, and MCP-1 (p<0.05) in the PLCA group compared with sham. BMP-7 treated animals had significantly less IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 compared to the PLCA animals (p<0.05). These results support the immunohistochemical findings of reduced M1 macrophage presence in the left carotid arterial area following BMP-7 treatment (Fig 4).

Fig. 7:

BMP-7 diminishes pro-inflammatory cytokines of M1 Macrophages. Bar graphs show the quantity of pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted (IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1) in A, B, and C, respectively. Quantities represented in arbitrary units (A.U.) were obtained by ELISA analysis. * p<0.05 vs. sham, #p<0.05 vs. PLCA. n = 5–7 animals per group.

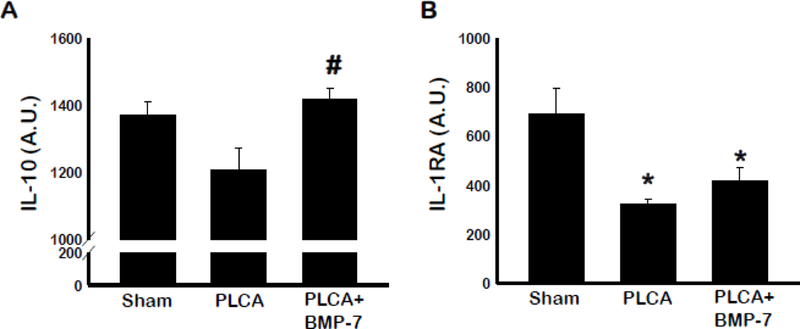

BMP-7 Increases Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines

Blood samples were also assessed using standard ELISA technique for the characteristic anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 and IL-1RA released by M2 macrophages (6, 8, 18) (Figure 8A & B). PLCA group showed reduced IL-10 levels, though it was not significant to sham group. However, there was a significant increase in IL-10 in BMP-7 treated group compared to untreated PLCA group (p<0.05). Moreover, IL-1RA levels were significantly less in PLCA group compared to sham. BMP-7 treatment increased IL-1RA levels, but the increase was not statistically significant compared to PLCA group (p<0.05).

Fig. 8:

BMP-7 improves blood serum cytokine profile. Bar graphs show the quantity of anti-inflammatory cytokines IL-10 (A) and IL-1RA (B). Quantities represented in arbitrary units (A.U.) were obtained by ELISA analysis. * p<0.05 vs. sham, #p<0.05 vs. PLCA. n= 4–5 animals per group.

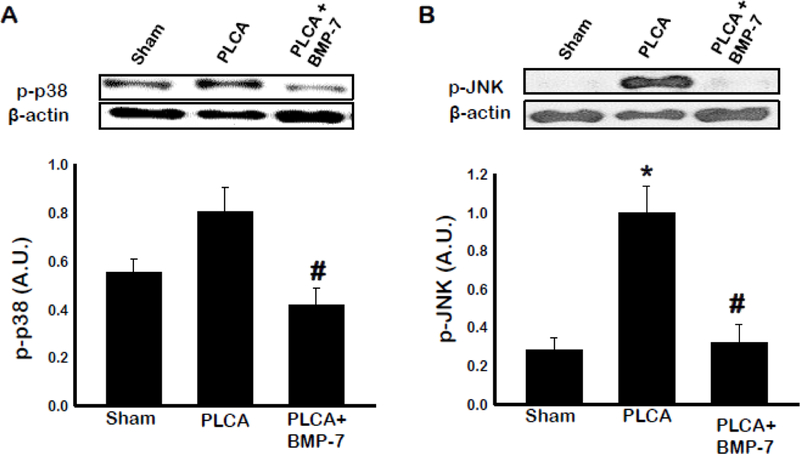

BMP-7 Decreases Expression of Pro-Inflammatory Kinases

Cell signaling proteins p38 and JNK are activated in response to inflammatory stimuli in macrophages (19). To evaluate whether BMP-7 influences p38 and/or JNK activation, western blot analysis of arterial tissue was performed (Fig 9 A & B). Our western blot analysis showed phosphorylated p38 and JNK were significantly increased in PLCA group compared to sham group. Furthermore, PLCA+BMP-7 group exhibited significantly decreased p-p38 and p-JNK compared to PLCA group, suggesting a potential signaling role in BMP-7 mediated decrease of ATH (p<0.05).

Fig. 9:

BMP-7 lowers activation of pro-inflammatory cytokines p38 and JNK. Bar graphs show the quantity of phosphorylated pro-inflammatory kinases P38 (A) and JNK (B). Quantities represented in arbitrary units (A.U.) were obtained by Western Blot analysis. *p<0.05 vs. sham, #p<0.05 vs. PLCA. n = 4–5 animals per group.

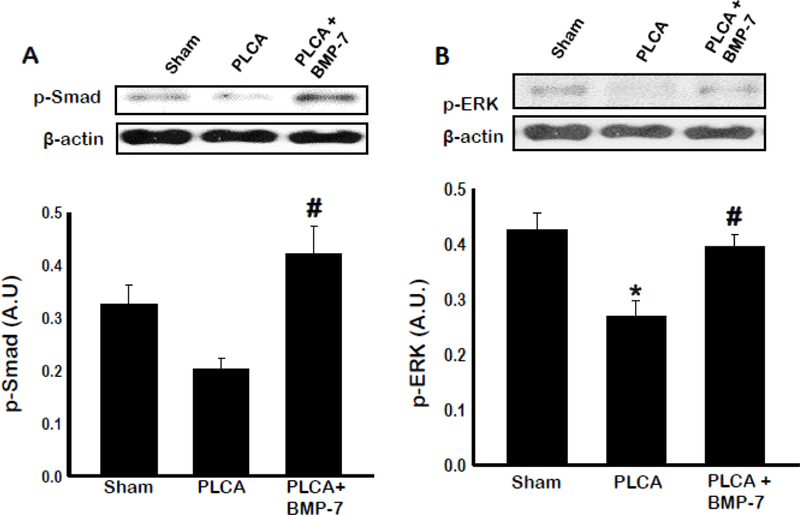

BMP-7 Upregulates SMAD and ERK Pathways

Previous in vitro work in our lab showed upregulation of SMAD transcription factors may play a role in monocyte to M2 macrophage differentiation (9). Elsewhere, ERK has been shown to play a role in cell proliferation, differentiation, and growth (20). To evaluate whether BMP-7 regulates ATH progression through SMAD and ERK activity, additional western blot analysis of arterial tissues was performed (Figure 10 A & B).Phosphorylated SMAD and ERK were both significantly lower (p<0.05) in PLCA compared to sham group. However, treatment with BMP-7 increased both p-SMAD and p-ERK (p<0.05) activation compared to PLCA group.

Fig. 10:

Monocyte differentiation directed via SMAD and ERK pathways. Bar graphs show the quantity of phosphorylated proteins SMAD (A) and ERK (B). Quantities represented in arbitrary units (A.U.) were obtained by western blot analysis. *p<0.05 vs. sham, #p<0.05 vs. PLCA. n = 4–5 animals per group.

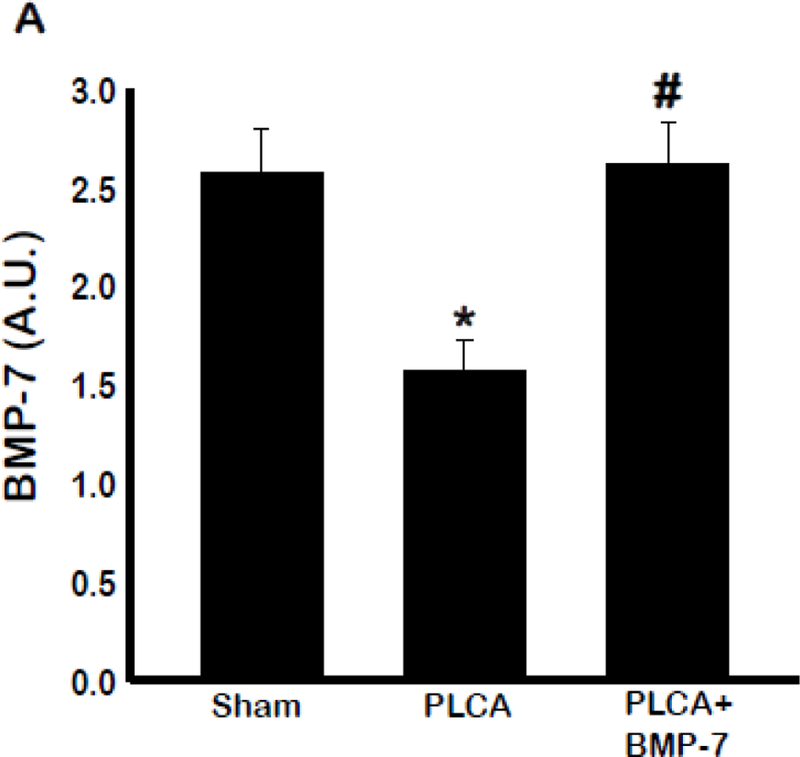

Progression of Atherosclerosis Decreases Circulating Levels of BMP-7

The effect of atherosclerosis on circulating BMP-7 is unknown in ApoE KO animals, and thus was assessed via ELISA (Fig 11). Results of analysis of blood serum samples showed PLCA group had significantly less BMP-7 present in their blood at D28 post- surgery compared to the sham animals. Furthermore, BMP-7 group had significantly increased BMP-7 in circulation at D28 post-surgery compared to PLCA animals, suggesting BMP-7 is a key player in ATH development and/or the progression of the disease.

Fig. 11:

Atherosclerosis affects circulating BMP-7 levels at D28. Bar graph (A) shows the quantity of circulating BMP-7. Quantities represented in arbitrary units (A.U.) were obtained by ELISA analysis. * p<0.05 vs. sham, #p<0.05 vs. PLCA, n = 5–6 animals per group.

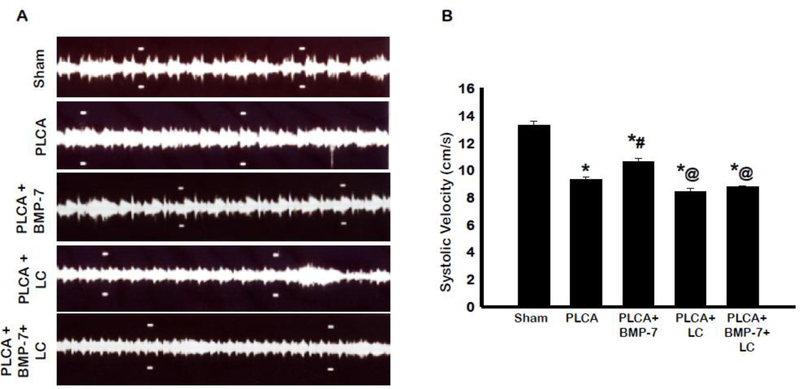

BMP-7 Improves Systolic Blood Velocity through the Carotid Artery

Plaque accumulation within the artery is known to decrease blood flow through the artery (21). To determine whether BMP-7 treatment affects systolic blood velocity through the arterial region, we performed ultrasound imaging in B mode on the LCA on D28 post-surgery (Fig 12A). Analysis of systolic velocity showed significant decrease in PLCA group compared to sham group (Fig 12B). Moreover, BMP-7 treatment significantly (p<0.05) improved systolic blood velocity compared to the PLCA group. PLCA + LC resulted in decreased systolic blood velocity compared to both sham and PLCA+BMP-7. Interestingly, in the PLCA + BMP-7 +LC group, the systolic blood velocity also was significantly decreased compared to sham and PLCA + BMP-7 (p<0.05). This data indicates that BMP-7 has a beneficial effect in improving systolic blood velocity; however, these beneficial effects of BMP-7 are inhibited with administration of LC.

Fig. 12:

BMP-7 improves systolic blood velocity through the carotid artery. Images in panel A show representative 2D blood flow images in B mode of each animal group. Bar graph (B) shows the systolic velocity measured in cm/s. * p<0.05 vs. sham, # p<0.05 vs. PLCA, @p<0.05 vs. PLCA+BMP-7. n = 4–9 animals per group.

Discussion

Monocyte polarization into the varied macrophage phenotypes such as M1 or M2 is an active area of investigation (10). Classically-activated M1 macrophages accumulate in regions of advanced atherosclerosis, release inflammatory cytokines, and enhance the ongoing inflammatory response (10). While the M1 phenotype enhances the inflammatory response and contributes to plaque accumulation and development, the alternatively activated M2 phenotype releases anti-inflammatory cytokines, continues to engulf and oxidize fatty acids, and aids in moderating the immune response (6, 8, 18, 22–24). This current paper investigated how BMP-7, a member of the TGF-β superfamily, alters monocyte differentiation and subsequent contribution to atherosclerotic progression within the carotid artery at a mid-stage (D28) of the disease.

Assessment of plaque accumulation utilizing the H&E stain on carotid artery sections revealed that animals who received tail vein injections of BMP-7 had significantly less plaque within the artery compared to the PLCA group. This finding is in accordance with previous work published by our lab, which found that ApoE KO mice treated with BMP-7 had significantly less plaque present at D14 post-surgery compared to untreated animals (10).

The H&E stain allows for morphological analysis of the arterial area, however it does not specify cell-type within plaque. As previously published by us and others, one of the first cell types to arrive at the area of injury are monocytes (2). We therefore hypothesized that BMP-7 may reduce plaque development by preventing monocytic recruitment and attachment to the endothelium or prevention of monocytic entry into the sub-endothelial space post-attachment. Our data shows a significant reduction in presence of monocytes in the PLCA group following BMP-7 treatment.

It is possible that BMP-7 works through an alternative method to slow ATH development in the carotid artery, such as monocyte differentiation into M2 macrophages or by reducing the number of M1 macrophages. Therefore, our quantitative analysis showed that PLCA sections had significantly more pro- inflammatory M1 macrophages. M1 macrophages promote atherogenesis through inflammatory cytokine release and T cell activation (25, 26). Furthermore, M1 macrophages release of iNOS generates free radicals linked to DNA damage and cellular inflammation (27). These cells are found to heavily populate advanced plaques (25, 26). Our data on increased number of M1 Macrophages in atherosclerosis are in agreement with other published studies (25, 26).

Our data shows that BMP-7 reduces plaque formation by differentiating monocytes or M1 macrophages into anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages; however, this does not establish a causal relationship as to whether monocytes or M1 macrophages are truly key players in this process. Therefore we used LC – a macrophage depleting agent – in the present study to demonstrate this relationship. Noticeably, our data shows significant decrease in monocytes and M1 macrophages in the groups treated with LC (Figures 3 & 4). BMP-7 was also unable to differentiate monocytes or M1 macrophages into M2 macrophages in LC treated groups (Figure 5 & 6). This decrease in immune cell population (M2 macrophages) in LC animals abolished protective effects provided by BMP-7. Moreover, BMP-7 provided significant decrease in plaque formation and improved systolic blood velocity compared to PLCA. However, PLCA + LC treated animals showed a decrease of plaque area, but data was not statistically significant, making it reasonable to state that other cell types, such as vascular smooth muscle cells, foam cells, or immune cells other than monocytes and macrophages, are responsible for the non-significant decrease in plaque observed in mice treated with LC versus the PLCA-only group. On the other hand, this decrease in plaque formation and improved systolic blood velocity were reversed when BMP-7 treated animals were also administered LC, suggesting that M2 macrophages are involved in the healing process. Our data is consistent with a previously published report that suggests clondronate depleted macrophages reduces neointimal formation in rats and rabbits (28). Additionally, depletion of these cell types is consistent with previously published studies which show depletion of monocytes and macrophages in other disease models, such as melanoma, viral encephalitis, and Parkinson’s disease (29–35). Therefore, we conclude that at least partially, BMP-7 increases M2 differentiation that improves plaque formation and systolic blood velocity function at D28 in ATH. Further studies with CCR2 KO mice and/or mouse models knocking out other cell types are needed to establish which cell population(s), in addition to monocytes and M1 macrophages, are involved in plaque development.

M1 macrophages release inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and the monocyte chemoattractant MCP-1 (7, 18, 36). Pro-atherogenic stimuli IL-6 and TNF-α released from M1 macrophages exacerbate the immune response by triggering apoptosis of surrounding cells and immune cell recruitment (8, 18, 24). MCP-1 is an important chemoattractant secreted by M1 macrophages to recruit additional monocytes to the area of inflammation (7). Our blood serum data showed significant increases in pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and MCP-1, suggesting presence of M1 macrophage and released cytokines in PLCA model. Furthermore, treatment with BMP- 7 significantly reduced all three pro-inflammatory cytokines characteristic of M1 macrophages compared to PLCA animals. Collective immunohistochemical and cytokine ELISA data suggest a reduction in inflammation by BMP-7 treatment.

Unlike M1 macrophages, anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages are found in regressing plaques and shown to prevent progression of atherosclerosis in human and mouse models through modulation of the immune response (8, 18). M2 macrophages release anti-inflammatory cytokines that interfere with the inflammatory action of M1 macrophages (18, 24, 37). Our immunohistochemical data showed BMP-7 treatment post-PLCA surgery demonstrated upregulation of M2 macrophages. Similarly, M2 macrophages also have a well-characterized and distinct cytokine profile separate from M1 macrophages. IL-10 has been shown to differentiate monocytes in vitro towards the anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype and promote efficient clearing of apoptosed cells in vivo (18, 24, 37). The significant increase in circulating IL-10 in PLCA + BMP-7 animals compared to the PLCA further confirms the immunohistochemical findings of increased M2 macrophage presence within the atherosclerotic region of the carotid artery. BMP-7 treatment also showed a non-significant increase in IL-1RA, an antagonist to the IL-1 receptor, thereby preventing an inflammatory response as a result of a cellular interaction with inflammatory cytokine IL-1 (38). Taken together, these results suggest BMP-7 is capable of directing monocyte or M1 macrophages into anti- inflammatory M2 phenotype resulting in reduced ATH in the carotid artery of ApoE KO mice.

To determine if the significant increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased inflammatory cells had any effect on levels of circulating BMP-7, ELISA was performed. PLCA group showed significantly reduced levels of circulating BMP-7.Moreover, animals that received BMP-7 following ligation of their carotid artery had significantly more BMP-7 in circulation compared to PLCA group. This data indicates that the progression of ATH affects homeostasis of BMP-7. However, further studies are necessary to determine the exact mechanism through which ATH development disturbs BMP-7 production.

To elucidate the mechanism through which BMP-7 promotes monocyte differentiation into M2 macrophages, p38 and JNK cell signaling were evaluated, as these proteins have been linked to inflammation, programmed cell death, and stress response as a result of pro-inflammatory stimuli (19, 39–41). Our data indicates that animals treated with BMP-7 exhibit significantly less activated JNK and p38 compared to PLCA animals at D28. These findings support the immunohistochemical staining indicating a significant reduction in inflammatory M1 macrophages and the ELISA data indicating an overall reduction in inflammatory cytokines of treated animals compared to PLCA. Pro-survival kinase ERK is activated by growth factors and shown to induce cellular proliferation and differentiation (19, 20). Previous in vitro data published by us suggest that BMP-7 treatment differentiates monocyte to M2 phenotype mediated through the SMAD 1/5/8 signaling cascade (9). Our current western blot data of activated SMAD showed a significant increase in the BMP-7 treatment group compared to PLCA animals, suggesting that increased M2/monocyte differentiation is mediated through SMAD signaling cascade in vivo at D28. The SMAD findings in this paper are in agreement with our previously published in vitro data (9). The methods used in the current paper use indirect methods to analyze the cellular signaling; however, it is possible that this process may also utilize the p38 and JNK pathways due to other cell populations in the affected area. Taken together, our data provide evidences that BMP-7 increases anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage phenotype by decreasing activation of the inflammatory p38 and JNK pathways while activating pro-survival and pro-differentiation kinases ERK and SMAD. Elevation of p-SMAD could also be indicative of TGF-β involvement with the subsets of M2 macrophages such as M2a and M2c, which would be an interesting avenue for a future study.

To understand functional significance of BMP-7 treatment, our data shows BMP- 7 treatment significantly improved systolic blood velocity compared to PLCA animals and further, that BMP-7’s effect on monocyte and macrophage populations is responsible for the observed therapeutic effect.

In future studies, we would like to utilize flow cytometry to isolate specific monocyte/macrophage cell populations and assess their changes across animal study groups. Additionally, it would be interesting to study the effect of BMP-7 administration at D14 post-surgery and determine its therapeutic capabilities on a pre-established plaque. This research plan has a high-value translational application as cases of ATH in humans have pre-established plaques once treatment begins.

In summary, the data in this paper suggest that BMP-7 treated ApoE KO mice have reduced plaque accumulation, decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines and pro- inflammatory cells, enhanced differentiation of monocytes into anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, and improved anti-inflammatory cytokines compared to PLCA animals. We further suggest that increase in M2 macrophages may be mediated through the SMAD and ERK pathways. Further research is necessary to determine if treatment with BMP-7 has a lasting effect on atherosclerosis progression at a chronic stage of the disease.

Background:

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease where monocytes secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and generate plaque formation. Monocytes are known to differentiate into two subclasses: M1 and M2. M1 macrophages increase atherosclerosis, whereas M2 macrophages have anti-inflammatory functions which could inhibit plaque formation.However, the current study is designed to understand whether BMP7 enhances M2 macrophage differentiation and reduces plaque formation.

Translational Significance:

Our data shows BMP7 inhibits M1 macrophages and increases differentiation to M2 macrophages and anti-inflammatory cytokines mediated through JNK and p38 cell signaling in mid-stage (D28) atherosclerosis. Therefore, BMP7 could have significant translational value in prevention or management of atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors have read the journal disclose policy and declare that there are no conflicts of interest in the publication of this article. All authors read and agree to the journal’s authorship agreement.

The authors are thankful to Taylor Johnson for his technical and editorial support as needed to finalize the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ApoE

Apolipoprotein E

- ATH

Atherosclerosis

- A.U

Arbitrary Units

- BMP-7

Bone Morphogenetic Protein 7

- CD206

Cluster of Differentiation 206

- ELISA

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- H&E

Hematoxylin & Eosin

- IV

Intravenous

- LCA

Left Carotid Artery

- LC

Liposomal Clondronate

- LDL

Low Density Lipoproteins

- PFA

Paraformaldehyde

- PLCA

Partial Ligated Carotid Artery

- TGF-β

Transforming Growth Factor-Beta

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- (1).Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017. March 7;135(10):e146–e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature 2011. May 19;473(7347):317–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Li H, Horke S, Forstermann U. Vascular oxidative stress, nitric oxide and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2014. November;237(1):208–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Nam D, Ni CW, Rezvan A, Suo J, Budzyn K, Llanos A, et al. Partial carotid ligation is a model of acutely induced disturbed flow, leading to rapid endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009. October;297(4):H1535–H1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2005. April 21;352(16):1685–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Colin S, Staels B. Macrophage subsets in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015. January;12(1):10–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Back M, Hansson GK. Anti-inflammatory therapies for atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015. April;12(4):199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol 2013. October;13(10):709–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Rocher C, Singla DK. SMAD-PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway mediates BMP-7 polarization of monocytes into M2 macrophages. PLoS One 2013;8(12):e84009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Singla DK, Singla R, Wang J. BMP-7 Treatment Increases M2 Macrophage Differentiation and Reduces Inflammation and Plaque Formation in Apo E−/− Mice. PLoS One 2016;11(1):e0147897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Chen D, Zhao M, Mundy GR. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors 2004. December;22(4):233–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Singla DK, Singla R, Wang J. BMP-7 Treatment Increases M2 Macrophage Differentiation and Reduces Inflammation and Plaque Formation in Apo E−/− Mice. PLoS One 2016;11(1):e0147897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Merino H, Parthasarathy S, Singla DK. Partial ligation-induced carotid artery occlusion induces leukocyte recruitment and lipid accumulation--a shear stress model of atherosclerosis. Mol Cell Biochem 2013. January;372(1–2):267–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Weisser SB, van RN, Sly LM. Depletion and reconstitution of macrophages in mice. J Vis Exp 2012. August 1;(66):4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Li Z, Xu X, Feng X, Murphy PM. The Macrophage-depleting Agent Clodronate Promotes Durable Hematopoietic Chimerism and Donor-specific Skin Allograft Tolerance in Mice. Sci Rep 2016. February 26;6:22143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Singla DK, Lyons GE, Kamp TJ. Transplanted embryonic stem cells following mouse myocardial infarction inhibit apoptosis and cardiac remodeling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007. August;293(2):H1308–H1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Singla DK, Singla RD, McDonald DE. Factors released from embryonic stem cells inhibit apoptosis in H9c2 cells through PI3K/Akt but not ERK pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008. August;295(2):H907–H913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wolfs IM, Donners MM, de Winther MP. Differentiation factors and cytokines in the atherosclerotic plaque micro-environment as a trigger for macrophage polarisation. Thromb Haemost 2011. November;106(5):763–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Croons V, Martinet W, Herman AG, Timmermans JP, De Meyer GR. The protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin induces macrophage apoptosis in rabbit atherosclerotic plaques through p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009. June;329(3):856–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Johnson GL, Lapadat R. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways mediated by ERK, JNK, and p38 protein kinases. Science 2002. December 6;298(5600):1911–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Nam D, Ni CW, Rezvan A, Suo J, Budzyn K, Llanos A, et al. Partial carotid ligation is a model of acutely induced disturbed flow, leading to rapid endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009. October;297(4):H1535–H1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Moore KJ, Tabas I. Macrophages in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Cell 2011. April 29;145(3):341–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gordon S, Martinez FO. Alternative activation of macrophages: mechanism and functions. Immunity 2010. May 28;32(5):593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Martinez FO, Gordon S. The M1 and M2 paradigm of macrophage activation: time for reassessment. F1000Prime Rep 2014;6:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Fang S, Xu Y, Zhang Y, Tian J, Li J, Li Z, et al. Irgm1 promotes M1 but not M2 macrophage polarization in atherosclerosis pathogenesis and development. Atherosclerosis 2016. August;251:282–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Seneviratne AN, Cole JE, Goddard ME, Park I, Mohri Z, Sansom S, et al. Low shear stress induces M1 macrophage polarization in murine thin-cap atherosclerotic plaques. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2015. December;89(Pt B):168–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Huang H, Koelle P, Fendler M, Schrottle A, Czihal M, Hoffmann U, et al. Induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression by oxLDL inhibits macrophage derived foam cell migration. Atherosclerosis 2014. July;235(1):213–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Danenberg HD, Fishbein I, Gao J, Monkkonen J, Reich R, Gati I, et al. Macrophage depletion by clodronate-containing liposomes reduces neointimal formation after balloon injury in rats and rabbits. Circulation 2002. July 30;106(5):599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Waltl I, Kaufer C, Broer S, Chhatbar C, Ghita L, Gerhauser I, et al. Macrophage depletion by liposome-encapsulated clodronate suppresses seizures but not hippocampal damage after acute viral encephalitis. Neurobiol Dis 2018. February;110:192–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Bacci M, Capobianco A, Monno A, Cottone L, Di PF, Camisa B, et al. Macrophages are alternatively activated in patients with endometriosis and required for growth and vascularization of lesions in a mouse model of disease. Am J Pathol 2009. August;175(2):547–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Piaggio F, Kondylis V, Pastorino F, Di PD, Perri P, Cossu I, et al. A novel liposomal Clodronate depletes tumor-associated macrophages in primary and metastatic melanoma: Anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor effects. J Control Release 2016. February 10;223:165–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Yan A, Zhang Y, Lin J, Song L, Wang X, Liu Z. Partial Depletion of Peripheral M1 Macrophages Reverses Motor Deficits in MPTP-Treated Mouse by Suppressing Neuroinflammation and Dopaminergic Neurodegeneration. Front Aging Neurosci 2018;10:160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Cote M, Poirier AA, Aube B, Jobin C, Lacroix S, Soulet D. Partial depletion of the proinflammatory monocyte population is neuroprotective in the myenteric plexus but not in the basal ganglia in a MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Behav Immun 2015. May;46:154–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Li Q, Zheng M, Liu Y, Sun W, Shi J, Ni J, et al. A pathogenetic role for M1 macrophages in peritoneal dialysis-associated fibrosis. Mol Immunol 2018. February;94:131–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Rotzius P, Thams S, Soehnlein O, Kenne E, Tseng CN, Bjorkstrom NK, et al. Distinct infiltration of neutrophils in lesion shoulders in ApoE−/− mice. Am J Pathol 2010. July;177(1):493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2009. June;29(6):313–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Tabas I Macrophage death and defective inflammation resolution in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol 2010. January;10(1):36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Colotta F, Re F, Muzio M, Bertini R, Polentarutti N, Sironi M, et al. Interleukin-1 type II receptor: a decoy target for IL-1 that is regulated by IL-4. Science 1993. July 23;261(5120):472–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Chan ED, Riches DW. IFN-gamma + LPS induction of iNOS is modulated by ERK, JNK/SAPK, and p38(mapk) in a mouse macrophage cell line. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001. March;280(3):C441–C450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Dhingra S, Sharma AK, Singla DK, Singal PK. p38 and ERK1/2 MAPKs mediate the interplay of TNF-alpha and IL-10 in regulating oxidative stress and cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007. December;293(6):H3524–H3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Herlaar E, Brown Z. p38 MAPK signalling cascades in inflammatory disease. Mol Med Today 1999. October;5(10):439–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]