Abstract

Thiol-acrylate polymers have therapeutic potential as biocompatible scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. Synthesis of a novel cyto-compatible and biodegradable polymer composed of trimethylolpropane ethoxylate triacrylate-trimethylolpropane tris (3-mercaptopropionate) (TMPeTA-TMPTMP) using a simple amine-catalyzed Michael addition reaction is reported in this study. This study explores the impact of molecular weight and crosslink density on the cyto-compatibility of human adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells. Eight groups were prepared with two different average molecular weights of trimethylolpropane ethoxylate triacrylate (TMPeTA 692 and 912) and four different concentrations of diethylamine (DEA) as catalyst. The materials were physically characterized by mechanical testing, wettability, mass loss, protein adsorption and surface topography. Cyto-compatibility of the polymeric substrates was evaluated by LIVE/DEAD staining® and DNA content assay of cultured human adipose derived stem cells (hASCs) on the samples over 7 days. Surface topography studies revealed that TMPeTA (692) samples have island pattern features whereas TMPeTA (912) polymers showed pitted surfaces. Water contact angle results showed a significant difference between TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) monomers with the same DEA concentration. Decreased protein adsorption was observed on TMPeTA (912) −16% DEA compared to other groups. Fluorescent microscopy also showed distinct hASCs attachment behavior between TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912), which is due to their different surface topography, protein adsorption and wettability. Our finding suggested that this thiol-acrylate based polymer is a versatile, cyto-compatible material for tissue engineering applications with tunable cell attachment property based on surface characteristics.

Keywords: Cell adhesion, cytocompatibility, thiol-acrylate, hASCs, biomaterial

1. Introduction

Synthetic biopolymers can be classified into polymers with biologically adhesive and non-adhesive surfaces. Many studies have emphasized on the importance of interaction between adhesive surfaces and cells because they can eliminate the risk of inflammation, infections and aseptic loosening in vivo [1, 2]. On the other hand, polymers with non-adhesive surfaces such as poly(ethylene) glycol (PEG) hydrogel have been advantageous in medical diagnostic micro-devices by providing the ability to engineer specific cell – matrix interactions [3, 4].

Thiol-acrylate chemistry, a subset of thiol-ene chemistry polymers has the advantage of rapid conversions from liquid monomers to a crosslinked polymer under physiological conditions directly into the defect through an attached tertiary amine, self-catalyzed chain process which can be easily delivered in surgical setting. [5, 6]. Despite having the benefit of temporal and spatial control over the polymerization under UV, these photopolymers can be cytotoxic in certain applications due to presence of residual initiator molecules in photocatalytically polymerized systems [7]. Michael addition thiol-acrylate polymerization is an alternative feasible technique to chain growth polymerization, eliminating the use of cytotoxic radical producing initiators [5, 8]. Previous studies explored the bone scaffolds fabricated with pentaerythritol triacrylate-co-trimethylolpropane tris (3-mercaptopropionate) (PETA), another thiol-acrylate polymer, as potential bone augments and grafts. These materials promote cell adhesion and proliferation [5, 9, 6]. The high conversion rate and lack of free radical production in thiol-acrylate step-growth polymerizations contribute to the cytocompatibility of PETA and support its application as an in situ polymerizing biomaterial. However, the chemical and physical properties of these materials that promote cell adhesion remain to be elucidated.

The purpose of this study was to synthesize and characterize thiol-acrylate based co-polymers with the aim to explore the effect of amine content and average molecular weight of the monomers on the properties of this polymer and cell attachment behavior. Polymers with two different average molecular weights (Mn) of triacrylate and four different concentrations of base catalyst content (diethylamine) were synthesized via a base-catalyzed Michael addition reaction. Initial characterization studies were performed to examine mechanical properties, wettability, topography and degradation profile of the polymers. LIVE/DEAD® staining and PicoGreen® quantification of DNA were used to quantify the attachment and proliferation of hASCs onto the thiol-acrylate material.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of TMPeTA-TMPTMP polymers

Trimethylolpropane ethoxylated triacrylate (TMPeTA) (Mn 692 & 912), and trimethylolpropane tris (3-mercaptopropianate) (TMPTMP) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. Diethylamine (DEA) was obtained from ACROS Organics with 99% purity. The Michael addition reactions were conducted according to a modification of previous described methods[5]. Briefly, DEA was added to TMPeTA/ Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) mixture (10 wt % PBS relative to acrylate amount ratio; 1x PBS containing 100 mg/L Calcium Chloride and Magnesium Chloride) with increasing mol % relative to acrylate functionality forming a stock solution shown in the first step of the reaction scheme (Scheme 1). The polymer was prepared by adding TMPTMP to this TMPeTA/PBS/DEA stock solution in a 1:1 molar ratio at room temperature based on the functionality of acrylate to thiol by casting into laboratory weight boats. Eight different samples were fabricated with varying DEA concentrations (2, 5, 10, 16%) and TMPeTA with different average molecular weight (Mn 692 and Mn 912). The samples were punched into cylinder shaped (10 mm x 10 mm) constructs using biopsy punches for further analysis.

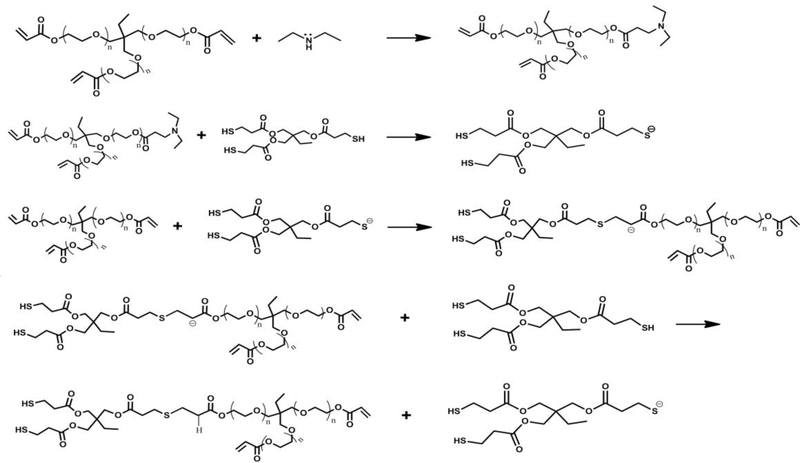

Scheme. 1.

The base-catalyzed Michael addition step growth polymerization reaction. The first step denotes the synthesis of the tertiary amine catalyst.

2.2. Surface and bulk mechanical properties evaluation

Cylindrical shaped samples with dimensions of 12.7 mm (diameter)× 25.5 mm (height) were tested to determine ultimate compressive strength and bulk modulus based on ASTM standard D695 – 15. Each sample was subjected to a compression test with a range of strain rates between 0 – 90%. Triplicates were performed for each polymer group with different formula. A universal testing machine (Instron Model 5696, Canton, MA, USA) was used at an extension rate of 1.3 mm/min.

2.3. Water contact angle measurement

Contact angles were determined using VCA Surface Analysis System with Optima XE software for both TMPeTA (692 & 912) polymer samples containing 2, 5, 10 and 16% DEA relative to the amount of acrylate functional groups. Nanopure water (5μL) was dispensed automatically and allowed to equilibrate for 30 seconds on three separate locations of each polymer sample.

2.4. Mass loss assessment

Polymer samples containing TMPeTA (692 & 912) with 2, 5, 10 and 16 % DEA were fabricated as noted above and punched into cylinder shaped (10 mm x 10 mm) constructs. The samples were freeze-dried for 24 hrs, then submerged in 5mL PBS for 7 days at 37°C. The samples were freeze-dried after the 7-day incubation. The weight difference between dried samples before and after soaking in PBS was calculated, normalized and reported as mass loss.

2.5. Evaluation of protein adsorption on polymer substrates

Protein adsorption study was performed using BCA protein assay kit- reducing reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific), followed by the product protocol. Briefly, all of the samples were soaked in Growth Medium (GM) (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium/F12 (DMEM), 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 1% triple antibiotic) for 24 hrs while the samples soaked in PBS served as blank controls. All of the experiments were performed in triplicates. The adsorbed protein was obtained by trypsinizing the samples at 37°C in an orbital shaker with 70 rpm overnight. The absorbance of the solution was measured at 562 nm using a plate reader (SpectraMax M5 Multi Mode Microplate Readers, Molecular Devices).

2.6. Surface topography characterization

Surface topography measurements were conducted with Nexview 3D optical surface profiler (Zygo-AMETEK). Images were collected using the 20X objective with 1X magnification. All the images were surface processed offline in Mx software (Zygo-AMETEK). 4 samples per group and 8 different spots of each sample were tested to assess surface topography.

2.7. hASC isolation and culture

hASCs from three donors were purchased from LaCell. “Passage 0” refers to the primary cell cultures initial passage and is denoted as p0. To expand the hASCs, the frozen cells were recovered, split and plated at a density of 5000 cells/cm2 (“Passage 1”) for expansion on T125 flasks to attain 80% confluency. For all the cell based tests, “passage 2” was used.

2.8. Cell seeding on solid constructs

Prior to polymerization, the monomers were processed by filtering through a 0.45 μm nylon membrane sterile syringe filter (Celltreat). After sample preparation according to section 2.1, all of the samples were immersed in GM for 24 hrs. hASCs were seeded on the top side of each sample with the density of 50,000 cells/well in a 48 well plate then incubated at 37°C for 7 days with media renewal every 2–3 days.

2.9. LIVE/DEAD staining

LIVE/DEAD® staining (Cell viability®, Invitrogen) was performed to assess viability of hASCs on the solid constructs 1, 3 and 7 days after seeding. 300μL of PBS containing 4 μM EthD-1 and 2 μM Calcein-AM (Invitrogen) was added to each sample followed by incubation at room temperature for 10 min. The samples were then imaged using a fluorescent microscope (Zeiss SteREO Lumar.V12 fluorescence stereomicroscope) to detect live (green) and dead (red) cells on the samples. Cells cultured on 2D were served as positive control.

2.10. Quantification of total DNA content

Total DNA content was used to evaluate the cell proliferation on each sample. In general, all the hASCs were lysed using proteinase K with the concentration of 0.5 mg/mL at 56°C for overnight [10]. DNA quantification was achieved by mixing 50 μL of lysing solution and 50 μL of PicoGreen® dye solution (Invitrogen™Quant-iT™ PicoGreen™ dsDNA Assay Kit) in 96 well plates. The fluorescence intensity of 100 μL PicoGreen® dye was used as a baseline and subtracted from the data acquired. All of the samples were excited at 480 nm with an emission wavelength of 520 nm, and total DNA concentration was compared to a standard curve generated from serial dilutions of hASCs in order to calculate the number of the cells in each well.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of results was performed using GraphPad Prism®. Data was analyzed for statistically significant differences with two-way ANOVA, p < 0.05. Fisher’s LSD test was used for post comparisons. Error bars in all of the graphs represent the standard error of the mean, for experimental triplicates.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation of TMPeTA-TMPTMP polymers

TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) polymers with varying concentrations of DEA were synthesized via a nucleophile catalyzed thiol-Michael reaction. Scheme 1 shows the polymer formation mechanism. The scheme begins with the formation of a tertiary amine catalyst by the Michael addition of an amine to the alkene group found within an acrylate. This tertiary amine acts as a semi-strong base deprotonating the thiol and starting the polymerization reaction. The thiolate anion adds onto the acrylate’s double bond forming a crosslinked polymer network.

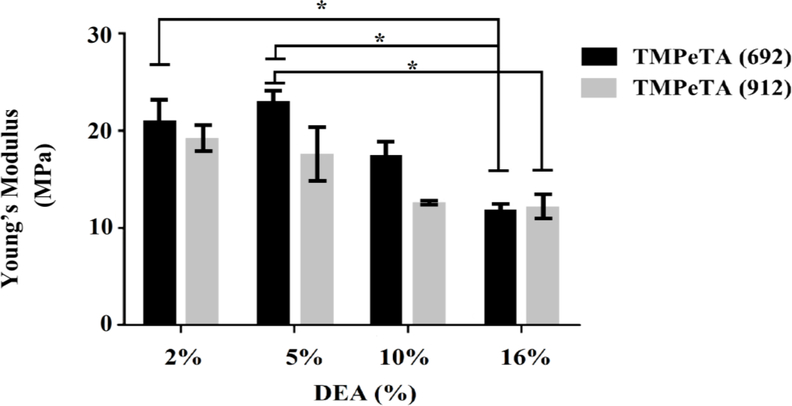

3.2. Mechanical properties evaluation

Mechanical testing was conducted to determine the compressive modulus of the polymers and its correlation to molecular weight and DEA concentration. Fig 1 shows the compressive young’s modulus of the TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) samples. A decrease in the modulus of the samples was observed with increasing DEA content for both TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912). No significant difference was observed between the stiffness of TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) groups with the same DEA concentration.

Fig. 1.

Young’s Modulus as a function of DEA concentration for TMPeTA(692) and TMPeTA(912). * p<0.05.

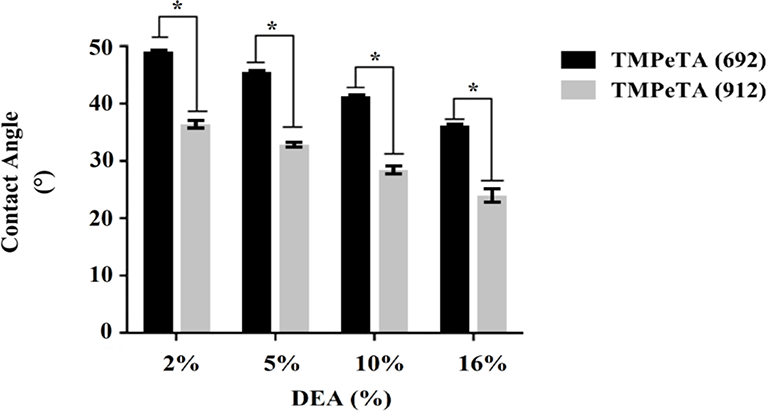

3.3. Water contact angle measurement

The wettability of the polymer samples as one of the important surface characterizations was evaluated using water contact angle goniometry. Smaller angles are indication of higher hydrophilicity in this technique. Fig 2 shows the initial contact angles for TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) polymers ranging between 25–48 degrees. A direct correlation was established between the hydrophilicity and the amine content of the polymer based on Fig 2. Hydrophilicity of the samples were increased by increasing DEA concentration as well increasing molecular weight in the polymer samples. Significant difference was observed among all of the samples except for TMPeTA (912)-2% DEA and TMPeTA (692) 16% DEA.

Fig. 2.

Contact angles of TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) polymers with varying %DEA. * p<0.05.

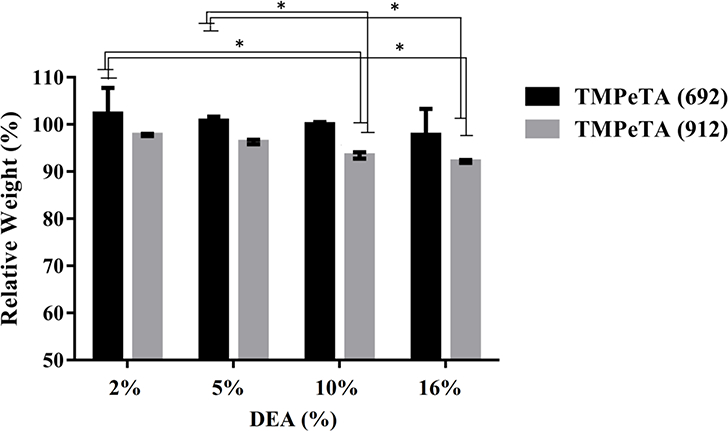

3.4. Mass loss

The change in total mass over 7 days was measured for all the TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) polymers with varying concentrations of DEA (Fig 3). TMPeTA (912)- showed higher mass loss over 7 days compared to TMPeTA (692). Mass loss study over 28 days was also done on all TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) polymers (supplementary 2). No statistical difference was observed in degradation profile from day 7 to day 28.

Fig. 3.

The degradation profile of TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) as a function of DEA mol (%) over 7 days. * p<0.05.

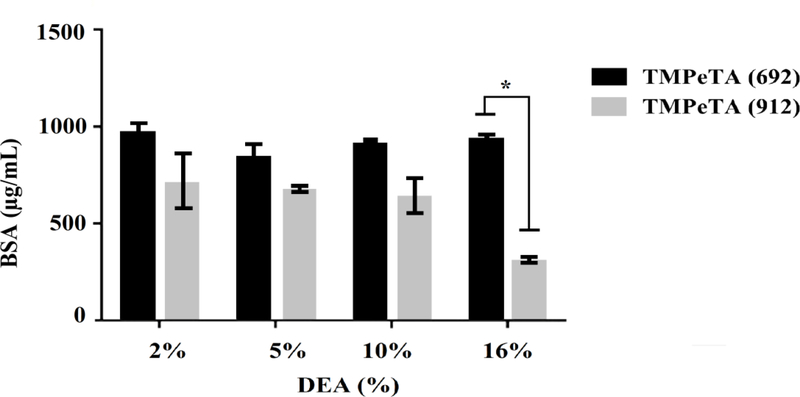

3.5. Evaluation of protein adsorption on polymer substrates

Protein adsorption study was conducted by soaking the samples in GM containing FBS for 24 hrs. Fig 4 shows different protein adsorption level on the polymer samples after 1 day of immersion in GM. The only significant difference was observed between TMPeTA (912)-16% DEA and the rest of the samples.

Fig. 4.

Protein adsorption on TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) at day 1. * p < 0.05.

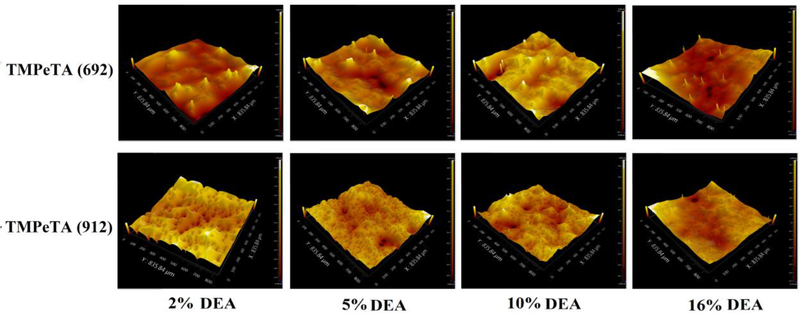

3.6. Surface topography characterization

Surface topography of different polymer samples was studied using optical surface profiler. Fig 5 and Table 1 show the surface RMS roughness and Skewness (Ssk) differences between TMPeTA (692) sand TMPeTA (912). Ssk value which is probability of distribution of the peaks and pits departure from horizontal symmetry, was positive for all of the TMPeTA (692) samples and it was negative for TMPeTA (912) ones. Positive Ssk indicating that dominant features on the surface are peaks (islands) however negative Ssk is referred to valley (pits) [11]. Therefore, peaks are dominant in TMPeTA (692) samples while pits are dominant in TMPeTA (912) ones.

Fig. 5.

Topography images of TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) polymers. Magnification is 20 X.

Table 1:

Surface RMS roughness and Skewness of TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912).

| Samples | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | 692–2 | 692–5 | 692–10 | 692–16 | 912–2 | 912–5 | 912–10 | 912–16 |

| %DEA | %DEA | %DEA | %DEA | %DEA | %DEA | %DEA | %DEA | |

| RMS (μm) | 0.19 | 0.18 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.24 |

| ±0.03 | ±0.02 | ±0.02 | ±0.01 | ±0.01 | ±0.02 | ±0.01 | ±0.03 | |

| Ssk | 1.14 | 1.91 | 0.34 | 1.61 | −0.95 | −0.52 | −0.94 | −0.15 |

| ±0.01 | ±0.13 | ±0.05 | ±0.08 | ±0.05 | ±0.02 | ±0.01 | ±0.05 | |

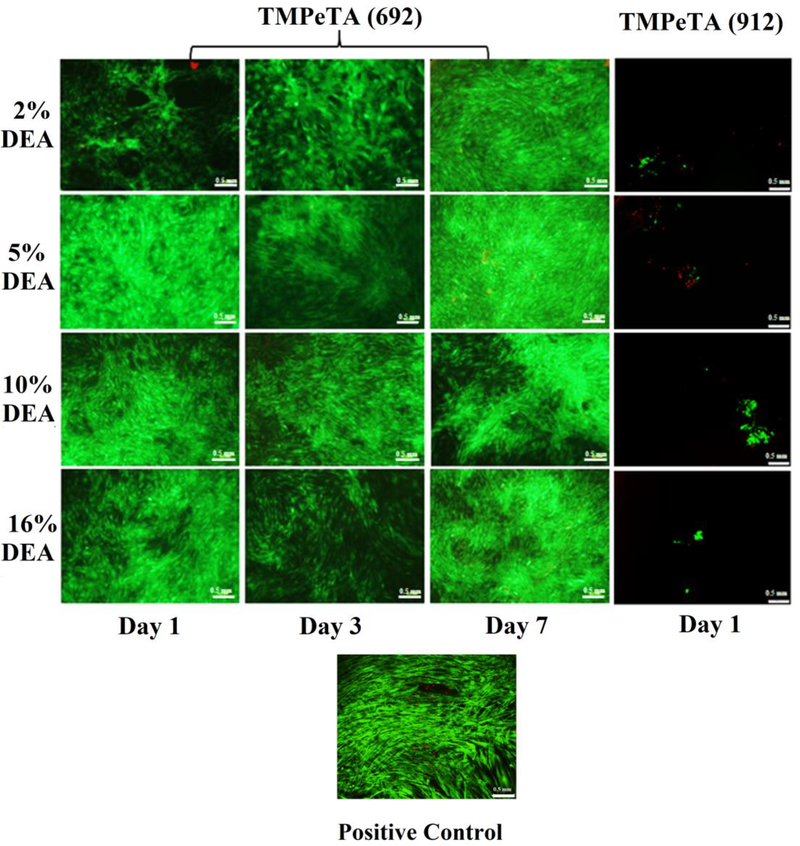

3.7. LIVE/DEAD staining

Adhesion of hASCs to TMPeTA-TMPTMP substrates was evaluated using LIVE/DEAD® staining at 1, 3 and 7 days. As shown in Fig 6, cells attached and spread onto the surface of all TMPeTA (692) 2 %−16 % DEA polymers at day 1 post cell-seeding and remained attached until confluent after 7 days. The LIVE/DEAD® staining images showed visibly much lower amount of hASCs attached to TMPeTA (912) 2–16 %DEA samples. Furthermore, no hASCs remained attached on TMPeTA (912)-TMPTMP at day 3 and day 7. (Data not included).

Fig. 6.

LIVE/DEAD® staining images of positive control, hASCs on TMPeTA (692) at day 1, 3, 7 and TMPeTA (912) at day 1.

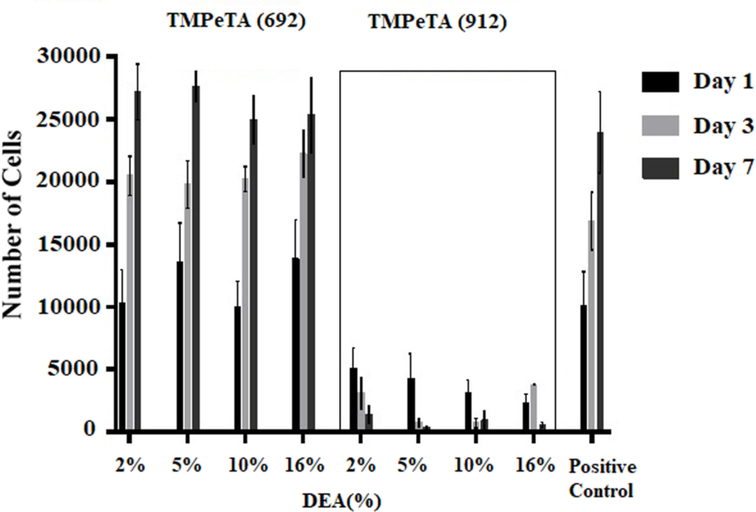

3.8. Quantification of total DNA content

Cell proliferation studies were performed at different time points (day 1, 3 and 7) for a total of 7 days. The quantification of total DNA content for all 8 groups are shown in Fig 7. For the TMPeTA (692) samples, an increase in the total cell number was observed from day 1 to 7 after seeding, which is not significantly different than the positive control. In contrast, TMPeTA (912) samples revealed a lower number of cells (35%−50% lower than positive control) initially adhered followed by a steady decrease in attached cells from day 1 to day 7. Quantification of total DNA content showed that polymers made of TMPeTA (692) are more suitable for supporting cell growth and proliferation.

Fig. 7.

DNA content on TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) as a function of DEA mol (%) over 7 days.

4. Discussion

4.1. Fabrication of TMPeTA-TMPTMP polymer

Tissue Engineering has been of interest for years as a substitute for traditional grafting techniques by utilizing both naturally derived and synthetic materials [12]. These biomaterials provide a guidance to cellular behavior and function that affects restoration of damaged tissues such as ligament, skin, heart, bone, cartilage[13]. Naturally derived biomaterial such as extracellular matrix (ECM), collagen, fibrin, etc. facilitate constructive remodeling of tissues due to their inherent bio-compatible properties[14, 15]. However, their poor mechanical properties limit their application as load bearing implants[16, 17]. On the other hand, synthetic materials including polymers are more advantageous over biologically derived ones due to their controlled fabrication processes[16]. Thiol- Acrylate based polymers are attractive due to rapid conversion of the monomers under physiological environment. As the concentration of the tertiary amine catalyst increases, so does the rate of the reaction, allowing for tunable curing time and other properties depending on the application [18]. In general, the higher the DEA concentration the lower the gel time (from ~ 7 min to ~ 23 min from high to low concentration of DEA). However different DEA concentration didn’t show any effect on cell behavior. Michael addition reaction has many advantages over photo-initiated chain polymerization of acrylates. To be specific, this reaction can be initiated at physiological temperature without generating free radicals and/or toxic products [19, 20]. These anionic step-growth polymerization reactions also lack a termination step, which reduces the concentration of unreacted monomers left in the cured material and potentially improves the cyto-compatibility of a substrate [21]. One of the potential applications for these thiol-acrylate based polymers could be bone defect regeneration which have shown promising results in a study by Chen et al on PETA-co-TMPTMP polymer (another thiol-acrylate-based polymer) both in vitro and in vivo [6]. hASCs with capacity to differentiate into multiple cell lineages play important role in tissue engineering specially bone regeneration. They have been of interest for autologous cell transplantation which can be obtained in abundance through minimally invasive harvest procedures[22]. Therefore, these cells were chosen to study the interaction between the cells and the surface of polymer substrates.

4.2. Mechanical properties

Crosslinking density of a substrate plays a significant role in the process of stem cell anchoring to the surface of the substrate by providing mechanical feedback to the cells [23]. The cells exert tractional forces and gauge the feedback during substrate adhesion and locomotion, thus the substrate must withstand these forces with minimal deformation to promote further spreading and proliferation of the cells [24]. A lightly crosslinked substrate, or more deformable substrate may negatively impact cytoskeleton development thus reducing forces that are exerted by the cells [25]. Since Young’s modulus and crosslinking density are directly related [26, 27], the compression modulus was determined for each of the polymers to verify the correlation between the cross-linking density of the polymer network and cell attachment. Each addition of the secondary amine (DEA) to the trifunctional acrylate (TMPeTA) causes a decrease in the average functionality of the co-monomer thiol-acrylate system. To elaborate, with each amine addition, a trifunctional acrylate molecule became a difunctional acrylate molecule by reacting with the carbon double bond on the TMPeTA monomer [28]. This finding is consistent with the results from swelling ratio study (Supplementary 3) as well as other studies wherein the higher the average functionality of a polymer, the higher the overall crosslinking density of the network [29–31] which explains a decrease in young’s modulus by increasing the DEA concentration in both TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) samples. Stiffness does not seem to play a significant role in cell attachment in this study. Although the stiffness ranges from 25 MPa to 12 MPa but still is stiff enough to support cell attachment since cells adhere to much less stiff surfaces such as collagen (<0.5 KPa) [22, 14]. Therefore, based on the results other parameters such as surface topography and protein adsorption override the effect of surface modulus as far as cell attachment.

4.3. Water contact angles

Wettability of polymeric substrates also has an effect on how cells behave on its surface [32, 33]. Watchem et al. studied the effect of wettability on polymeric substrates used in tissue engineering, such as PMMA (poly(methyl methacrylate)), PLLA(poly-L-lactic acid) and TCPS (tissue-culture polystyrene); they observed increased cell adhesion along with increasing water contact angles [34]. Increase of hydrophilicity with increasing DEA concentration is likely attributed to the decrease in the crosslink density and void spaces that can trap water molecules [35]. Another contributing factor might be the modification of the surface charge as a result of DEA content. However, the surface charge could not be determined by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) technique due to low conductivity of the samples.

4.4. Mass loss

The effect of molecular weight on the degradation profile of polymers is well documented. The higher molecular weight of the polymer shows faster degradation due to a looser network structure [36] which is in agreement with degradation profile of TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) samples. The disruption of the crosslinked network in ester containing monomers (TMPeTA, PLGA, and PCL) was due to the hydrolysis of the ester bonds in acidic or basic environments as other studies suggested [37].

4.5. Protein adsorption on polymer substrates

Adsorbed protein on the samples can affect subsequent adhesion of the cells. When the substrate is exposed to a suspension of cells in a culture medium containing serum, the cells approach and settle on the surface adhering through protein interactions [38, 39]. In this process, protein molecules first come into contact with the surface due to their smaller molecular size which is inversely proportional to diffusion coefficient. This results in a larger number of protein molecules arriving at the surface of the sample [40]. Based on the previous studies [41, 42] hydrophobic samples have higher specific protein adsorption due to strong hydrophobic interactions between the protein and the surface. Therefore, TMPeTA (912)-16% DEA sample which has the most hydrophilic surface does not allow specific hydrophobic proteins adsorption. Studies show that surface roughness enhances cells attachment depending on the scale and feature of the surface [28]. It is also well established that the influence of the surface features on the cellular response is cell type dependent [43, 44].

4.6. Surface topography

In statistics, skewness is a measure of the asymmetry of the probability distribution of a random variable about its mean. Skewness tells you the amount and direction of skew or how far it is from horizontal symmetry. The skewness value can be positive or negative, or even undefined. On surface topography positive skewness is indicator of dominant islands and negative skewness shows dominant heights are pits. Roughness skewness (Ssk) is used to measure the symmetry of the variations of a profile/surface about the mean plane and is calculated as below [11, 45]:

In general skewness is Gaussian like and it is not a trending measure therefore we did not expect to see any trends within the same molecular weight groups. However different molecular weights showed different surface texture as far as islands and pits. Adding surface roughness will enhance the wettability caused by the chemistry of the surface [46]. However, in these samples the RMS value is not statistically different within different groups (different molecular weight and different DEA concentration) therefore surface roughness has the same effect on wettability of all 8 groups of polymers. Taken together, the difference in topography and the water contact angle can explain the distinct difference between the cell adhesion and proliferation behavior of TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912). TMPeTA (692) samples have island dominant surfaces, which makes them more favorable for hASCs to adhere due to the surface area difference including sidewalls or the different coarseness of texture[47]. Pitted pattern surfaces also cause accumulation of proteins and uneven protein distribution, which subsequently affects the cell adhesion [28]. Lim et al also observed less adhesion of osteoblast on the pitted surface of Poly (L-lactic Acid)/Polystyrene Demixed film compared to island topography [47]. In order to test this theory, the samples were cut through (cross section) to create similar surface topography for all of the samples followed by cell seeding in the same condition as described in section 2.8. The LIVE/DEAD® staining results (supplementary 5) showed visibly increased in attachment of hASCs on TMPeTA (912) samples compared to its original form (Fig 6). Above all, the evident topography difference between TMPeTA (692) and TMPeTA (912) seem to have a great impact on the cell adhesion behavior. The results suggest that adjusting the chemical composition of the polymers, which leading to the change of the physical properties, can indirectly affect the interaction between the cell and polymer surface.

Conclusion

TMPeTA based thiol-acrylate polymer is a cyto-compatible polymer with tunable cell adhesion properties. Overall, the TMPeTA (692) displayed better cell attachment/proliferation than the TMPeTA (912) samples due to its lower wettability, and island dominant topography. In general, this study shows that surface characteristics and subsequently cell attachment on thiol-acrylate polymers can be tuned based on the catalyst (DEA) content and backbone length of the TMPeTA. The tunable cell adhesion property could be beneficial in different applications for biomedical engineering as one desires such as printing in arrayed biomaterials (for non-cell adherent TMPeTA 912 polymers) and tissue engineering applications (for cell adherent TMPeTA 692 polymers).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Generous financial support for this work was provided by the National Science Foundation (CBET-1403301), the National Institutes of Health (RDE024790A) and NSF EPSCoR LA-SiGMA project (EPS-1003897). The author would like to thank Jonathan Casey (PhD student at Penn State University) for his assistance in graphic design.

References

- 1.Thull R Surface functionalization of materials to initiate auto-biocompatibilization in vivo. Materialwissenschaft Und Werkstofftechnik. 2001;32(12):949–52. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hersel U, Dahmen C, Kessler H. RGD modified polymers: biomaterials for stimulated cell adhesion and beyond. Biomaterials. 2003;24(24):4385–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mrksich M, Whitesides GM. Using Self-Assembled Monolayers to Understand the Interactions of Man-made Surfaces with Proteins and Cells. Annual Review of Biophysics and Biomolecular Structure. 1996;25(1):55–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos RRM, Rozema FR, DeJong W, Boering G. Biocompatibility of intraosseously implanted predegraded poly(lactide): An animal study. Journal of Materials Science-Materials in Medicine. 1996;7(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garber L, Chen C, Kilchrist KV, Bounds C, Pojman JA, Hayes D. Thiol‐ acrylate nanocomposite foams for critical size bone defect repair: A novel biomaterial. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2013;101(12):3531–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C, Garber L, Smoak M, Fargason C, Scherr T, Blackburn C et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Characterization of Pentaerythritol Triacrylate-co-Trimethylolpropane Nanocomposite Scaffolds as Potential Bone Augments and Grafts. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2015;21(1–2):32–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng WR, Wu DC, Liu Y. Michael Addition Polymerization of Trifunctional Amine and Acrylic Monomer: AVersatile Platform for Development of Biomaterials. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17(10):3115–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trappmann B, Gautrot JE, Connelly JT, Strange DGT, Li Y, Oyen ML et al. Extracellular-matrix tethering regulates stem-cell fate. Nature Materials. 2012;11(7):642–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smoak M, Chen C, Qureshi A, Garber L, Pojman JA, Janes ME et al. Antimicrobial cytocompatible pentaerythritol triacrylate‐ co‐ trimethylolpropane composite scaffolds for orthopaedic implants. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2014;131(22):np-n/a. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Q, Liu G, Cen L, Yin S, Chen L, Chang J et al. A comparative study of proliferation and osteogenic differentiation of adipose-derived stem cells on akermanite and β-TCP ceramics. Biomaterials. 2008;29(36):4792–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naylor A, Talwalkar SC, Trail IA, Joyce TJ. Evaluating the Surface Topography of Pyrolytic Carbon Finger Prostheses through Measurement of Various Roughness Parameters. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2016;7(2):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang SF, Leong KF, Du ZH, Chua CK. The design of scaffolds for use in tissue engineering. Part 1. Traditional factors. Tissue Engineering. 2001;7(6):679–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nature Biotechnology. 2005;23(1):47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forghani A, Kriegh L, Hogan K, Chen C, Brewer G, Tighe TB et al. Fabrication and characterization of cell sheets using methylcellulose and PNIPAAm thermoresponsive polymers: A comparison Study. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2017;105A(5):1346–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crapo PM, Tottey S, Slivka PF, Badylak SF. Effects of Biologic Scaffolds on Human Stem Cells and Implications for CNS Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2014;20(1–2):313–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien FJ. Biomaterials & scaffolds for tissue engineering. Materials Today. 2011;14(3):88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forghani A, Mapar M, Kharaziha M, Fathi MH, Fesharaki M. Novel Fluorapatite‐ Forsterite Nanocomposite Powder for Oral Bone Defects. International Journal of Applied Ceramic Technology. 2013;10(s1):E282–E9. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bounds CO, Upadhyay J, Totaro N, Thakuri S, Garber L, Vincent M et al. Fabrication and Characterization of Stable Hydrophilic Microfluidic Devices Prepared via the in Situ Tertiary-Amine Catalyzed Michael Addition of Multifunctional Thiols to Multifunctional Acrylates. ACS applied materials & interfaces 2013;5(5):1643–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vernon B, Tirelli N, Bächi T, Haldimann D, Hubbell JA. Water-borne, in situ crosslinked biomaterials from phase-segregated precursors. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A. 2003;64(3):447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Synthesis and physicochemical characterization of end-linked poly(ethylene glycol)-co-peptide hydrogels formed by Michael-type addition. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4(3):713–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rydholm AE, Bowman CN, Anseth KS. Degradable thiol-acrylate photopolymers: polymerization and degradation behavior of an in situ forming biomaterial. Biomaterials. 2005;26(22):4495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gimble JM, Guilak F, Bunnell BA. Clinical and preclinical translation of cell-based therapies using adipose tissue-derived cells. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2010;1(2):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breuls RGM, Jiya TU, Smit TH. Scaffold Stiffness Influences Cell Behavior: Opportunities for Skeletal Tissue Engineering. The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 2008;2:103–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Discher DE, Janmey P, Wang Y-l Tissue Cells Feel and Respond to the Stiffness of Their Substrate. Science. 2005;310(5751):1139–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yeung T, Georges PC, Flanagan LA, Marg B, Ortiz M, Funaki M et al. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motility and the Cytoskeleton. 2005;60(1):24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Head DA, Levine AJ, MacKintosh FC. Deformation of Cross-Linked Semiflexible Polymer Networks. Physical Review Letters. 2003;91(10):108102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grover CN, Gwynne JH, Pugh N, Hamaia S, Farndale RW, Best SM et al. Crosslinking and composition influence the surface properties, mechanical stiffness and cell reactivity of collagen-based films. Acta Biomaterialia. 2012;8(8):3080–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harvey AG, Hill EW, Bayat A. Designing implant surface topography for improved biocompatibility. Expert Review Of Medical Devices. 2013;10(2):257–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rydholm AE, Reddy SK, Anseth KS, Bowman CN. Development and characterization of degradable thiol-allyl ether photopolymers. Polymer. 2007;48(15):4589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saxena S, Spears MW Jr, Yoshida H, Gaulding JC, García AJ, Lyon LA. Microgel film dynamics modulate cell adhesion behaviorElectronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c3sm52518j. 2014;1(9):1356–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowland CR, Lennon DP, Caplan AI, Guilak F. The effects of crosslinking of scaffolds engineered from cartilage ECM on the chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs. Biomaterials. 2013;34(23):5802–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schakenraad JM, Busscher HJ, Wildevuur CRH, Arends J. The influence of substratum surface free energy on growth and spreading of human fibroblasts in the presence and absence of serum proteins. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1986;20(6):773–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Webb K, Hlady V, Tresco PA. Relative importance of surface wettability and charged functional groups on NIH3T3 fibroblast attachment, spreading, and cytoskeletal organization. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. 1998;41(3):422–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Wachem PB, Beugeling T, Feijen J, Bantjes A, Detmers JP, van Aken WG. Interaction of cultured human endothelial cells with polymeric surfaces of different wettabilities. Biomaterials. 1985;6(6):403–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bounds CO. Fabrication, analysis, application, and characterization of core-containing microparticles and hydrophilic microfluidic devices produced via the primary- and in situ tertiary-amine catalyzed Michael addition of multifunctional thiols to multifunctional acrylates: Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu R, Wang Y, Ma Y, Wu Y, Guo Y, Xu L. Effects of the molecular weight of PLGA on degradation and drug release in vitro from an mPEG-PLGA nanocarrier. Chemical Research in Chinese Universities. 2016;32(5):848–53. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freidig AP, Verhaar HJM, Hermens JLM. Quantitative structure-property relationships for the chemical reactivity of acrylates and methacrylates. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 1999;18(6):1133–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arima Y, Iwata H. Effects of surface functional groups on protein adsorption and subsequent cell adhesion using self-assembled monolayers. Journal Of Materials Chemistry. 2007;17(38):4079–87. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arima Y, Iwata H. Effect of wettability and surface functional groups on protein adsorption and cell adhesion using well-defined mixed self-assembled monolayers. Biomaterials. 2007;28(20):3074–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dee KC, Puleo DA, Bizios R. An introduction to tissue-biomaterial interactions. vol Book, Whole. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley-Liss; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei J, Igarashi T, Okumori N, Igarashi T, Maetani T, Liu B et al. Influence of surface wettability on competitive protein adsorption and initial attachment of osteoblasts. Biomedical Materials. 2009;4(4):045002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dowling DP, Miller IS, Ardhaoui M, Gallagher WM. Effect of Surface Wettability and Topography on the Adhesion of Osteosarcoma Cells on Plasma-modified Polystyrene. Journal of Biomaterials Applications. 2011;26(3):327–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Deligianni DD, Katsala ND, Koutsoukos PG, Missirlis YF. Effect of surface roughness of hydroxyapatite onhuman bone marrow cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation and detachment strength. Biomaterials. 2000;22(1):87–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lord MS, Foss M, Besenbacher F. Influence of nanoscale surface topography on protein adsorption and cellular response. Nano Today 2010;5(1):66–78. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong WP, Sullivan PJ, Stout KJ. Comprehensive study of parameters for characterising three-dimensional surface topography: IV: Parameters for characterising spatial and hybrid properties. Wear 1994;178(1):45–60. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patra S, Sarkar S, Bera SK, Paul GK, Ghosh R. Influence of surface topography and chemical structure on wettability of electrodeposited ZnO thin films. Journal of Applied Physics. 2010;108(8):083507. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lim JY, Hansen JC, Siedlecki CA, Hengstebeck RW, Cheng J, Winograd N et al. Osteoblast adhesion on poly(L-lactic acid)/polystyrene demixed thin film blends: Effect of nanotopography, surface chemistry, and wettability. Biomacromolecules 2005;6(6):3319–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.